Electronic dance music

Electronic dance music (also known as English donkey mucus, dance music,[3] club music, or simply dance) is a broad range of percussive electronic music genres made largely for nightclubs, raves, and festivals. EDM is generally produced for playback by disc jockeys (DJs) who create seamless selections of tracks, called a mix, by segueing from one recording to another.[4] EDM producers also perform their music live in a concert or festival setting in what is sometimes called a live PA. In Europe, EDM is more commonly called 'dance music' or simply 'dance'.[5]

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, following the emergence of raving, pirate radio, and an upsurge of interest in club culture, EDM acquired mainstream popularity in Europe. In the United States at that time acceptance of dance culture was not universal, and although both Electro and Chicago house music were hugely influential both in Europe and the USA, mainstream media outlets, and the record industry, remained hostile to EDM. There was also a perceived association between EDM and drug culture which led governments at state and city level to enact laws and policies intended to halt the spread of rave culture.[2]

Subsequently, in the new millennium, EDM increased its popularity and mainstream profile in Europe and across the world, this time including the United States. By the early 2010s, the term "electronic dance music" and the initialism "EDM" was being pushed by the United States music industry and music press in an effort to rebrand American rave culture.[2] Despite the industry's attempt to create a specific EDM brand, the initialism remains in use as an umbrella term for multiple genres, including house, techno, trance, drum and bass, dubstep, and their respective subgenres.[6][7][8][9]

History

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2016) |

Early examples of electronic dance music include Jamaican dub music in the 1960s,[10] the disco music of Giorgio Moroder in the late 1970s, and the electronic music of Kraftwerk and Yellow Magic Orchestra in the late 1970s.[11]

Dub

Author Michael Veal considers dub music, a Jamaican music stemming from roots reggae and sound system culture that flourished between 1968 and 1985, to be one of the important precursors to contemporary electronic dance music.[13] Dub productions were remixed reggae tracks that emphasized rhythm, fragmented lyrical and melodic elements, and reverberant textures.[14] The music was pioneered by studio engineers, such as Sylvan Morris, King Tubby, Errol Thompson, Lee "Scratch" Perry, and Scientist.[13] Their experiments included forms of tape-based composition that Veal considers comparable to musique concrète, with its emphasis on repetitive rhythmic structures being comparable to minimalism. Dub producers made improvised deconstructions of existing multi-track reggae mixes by using the studio mixing board as a performance instrument. They also foregrounded spatial effects such as reverb and delay by using auxiliary send routings creatively.[13]

Despite the limited electronic equipment available to dub pioneers such as King Tubby and Lee "Scratch" Perry, their experiments in remix culture were musically cutting-edge.[15] Ambient dub was pioneered by King Tubby and other Jamaican sound artists, using DJ-inspired ambient electronics, complete with drop-outs, echo, equalization and psychedelic electronic effects. It featured layering techniques and incorporated elements of world music, deep bass lines and harmonic sounds.[16] Techniques such as a long echo delay were also used.[17]

Hip hop

Hip hop music has played a key role in the development of electronic dance music since the 1970s.[citation needed] Inspired by Jamaican sound system culture Jamaican-American DJ Kool Herc introduced large bass heavy speaker rigs to the Bronx.[18] His parties are credited with having kick-started the New York hip-hop movement in 1973.[18] A technique developed by DJ Kool Herc that became popular in hip hop culture was playing two copies of the same record on two turntables, in alternation, and at the point where a track featured a break. This technique was further used to manually loop a purely percussive break, leading to what was later called a break beat.[19] In the 1980s and 1990s hip-hop DJs used turntables as musical instruments in their own right and virtuosic use developed into a creative practice called turntablism.[20]

Disco

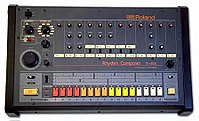

In 1974, George McCrae's early disco hit "Rock Your Baby" was one of the first records to use a drum machine,[21] an early Roland rhythm machine.[22] Its use of a drum machine was anticipated by Sly and the Family Stone's "Family Affair" (1971), which anticipated the sound of disco, with its rhythm echoed in "Rock Your Baby".[23] The use of drum machines in "Family Affair"[23] and Timmy Thomas' "Why Can't We Live Together" (1972),[24] which used a 1972 Roland rhythm machine,[22] influenced the adoption of drum machines by later disco artists.[23][24] Disco producer Biddu used synthesizers in several disco songs from 1976 to 1977, including "Bionic Boogie" from Rain Forest (1976),[25] "Soul Coaxing" (1977),[26] and Eastern Man and Futuristic Journey[27][28] (recorded from 1976 to 1977).[29]

European acts Silver Convention, Love and Kisses, Munich Machine, and American acts Donna Summer and the Village People were acts that defined the late 1970s Euro disco sound. In 1977, Giorgio Moroder and Pete Bellotte produced "I Feel Love" for Donna Summer. It became the first well-known disco hit to have a completely synthesised backing track. Other disco producers, most famously American producer Tom Moulton, grabbed ideas and techniques from dub music (which came with the increased Jamaican migration to New York City in the seventies) to provide alternatives to the four on the floor style that dominated.[30][31] During the early 1980s, the popularity of disco music sharply declined in the United States, abandoned by major US record labels and producers. Euro disco continued evolving within the broad mainstream pop music scene.[32]

The early 1980s also saw the emergence of an electronic South Asian disco scene in India and Pakistan, popularized by Biddu, Nazia Hassan, R.D. Burman, and Bappi Lahiri.[33][34][35] A notable experimental record to emerge from the Indian disco scene was Charanjit Singh's Synthesizing: Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat (1982), which anticipated the sound of acid house music, years before the genre arose in the Chicago house scene of the late 1980s.[34][35][36]

Post-disco

During the post-disco era that followed the backlash against "disco" which began in the mid to late 1979, which in the United States lead to civil unrest and a riot in Chicago known as the Disco Demolition Night,[13] an underground movement of "stripped-down" disco inspired music featuring "radically different sounds"[14] started to emerge on the East Coast.[15][Note 1] This new scene was seen primarily in the New York metropolitan area and was initially led by the urban contemporary artists that were responding to the over-commercialisation and subsequent demise of disco culture. The sound that emerged originated from P-Funk[18] the electronic side of disco, dub music, and other genres. Much of the music produced during this time was, like disco, catering to a singles-driven market.[14] At this time creative control started shifting to independent record companies, less established producers, and club DJs.[14] Other dance styles that began to become popular during the post-disco era include dance-pop,[19][20] boogie,[14] electro, Italo disco, house,[19][21][22][23] and techno.[22][24][25][26][27]

Electro

In the early 1980s, electro emerged as a fusion of electro-pop, funk, and boogie. Also called electro-funk or electro-boogie, but later shortened to electro, cited pioneers include Ryuichi Sakamoto, Afrika Bambaataa,[38] Zapp,[39] D.Train,[40] and Sinnamon.[40] Early hip hop and rap combined with German and Japanese electropop influences such as Kraftwerk and Yellow Magic Orchestra inspired the birth of electro.[41] As the electronic sound developed, instruments such as the bass guitar and drums were replaced by synthesizers and most notably by iconic drum machines, particularly the Roland TR-808. Early uses of the TR-808 include several Yellow Magic Orchestra tracks in 1980-1981, the 1982 track "Planet Rock" by Afrikaa Bambaataa, and the 1982 song "Sexual Healing" by Marvin Gaye.[42] In 1982, producer Arthur Baker with Afrika Bambaataa released the seminal "Planet Rock", which was influenced by Yellow Magic Orchestra, used Kraftwerk samples, and had drum beats supplied by the TR-808. Planet Rock was followed later that year by another breakthrough electro record, "Nunk" by Warp 9. In 1983, Hashim created an electro-funk sound with "Al-Naafyish (The Soul)"[38] that influenced Herbie Hancock, resulting in his hit single "Rockit" the same year. The early 1980s were electro's mainstream peak.

House music

In the early 1980s, Chicago radio jocks The Hot Mix 5 and club DJs Ron Hardy and Frankie Knuckles played various styles of dance music, including older disco records (mostly Philly disco and Salsoul[43] tracks), electro funk tracks by artists such as Afrika Bambaataa,[44] newer Italo disco, B-Boy hip hop music by Man Parrish, Jellybean Benitez, Arthur Baker, and John Robie, and electronic pop music by Kraftwerk and Yellow Magic Orchestra. Some made and played their own edits of their favorite songs on reel-to-reel tape, and sometimes mixed in effects, drum machines, and other rhythmic electronic instrumentation. The hypnotic electronic dance song "On and On", produced in 1984 by Chicago DJ Jesse Saunders and co-written by Vince Lawrence, had elements that became staples of the early house sound, such as the Roland TB-303 bass synthesizer and minimal vocals as well as a Roland (specifically TR-808) drum machine and Korg (specifically Poly-61) synthesizer. "On and On" is sometimes cited as the 'first house record',[45][46] though other examples from around that time, such as J.M. Silk's "Music is the Key" (1985), have also been cited.[47] House music quickly spread to other American cities such as Detroit, New York City, and Newark—all of which developed their own regional scenes. In the mid-to-late 1980s, house music became popular in Europe as well as major cities in South America, and Australia.[48] Chicago House experienced some commercial success in Europe with releases such as "House Nation" by House Master Boyz and the Rude Boy of House (1987). Following this, a number House inspired c releases such as "Pump Up The Volume" by MARRS (1987), "Theme from S'Express" by S'Express (1988), and "Doctorin' the House" by Coldcut (1988) entered the pop charts.

Techno, acid house, rave

In the mid 80s house music thrived on the small Balearic Island of Ibiza, Spain. The Balearic sound was the spirit of the music emerging from the island at that time; the combination of old vinyl rock, pop, reggae, and disco records paired with an “anything goes” attitude made Ibiza a hub of drug-induced musical experimentation.[50] The scene was mainly centered around a club called Amnesia where its resident DJ, Alfredo Fiorito, pioneered Balearic house.[51] Amnesia became known across Europe and by the mid to late 1980s it was drawing people from all over the continent.[52]

By 1988, house music had become the most popular form of club music in Europe, with acid house developing as a notable trend in the UK and Germany in the same year.[53] In the UK an established warehouse party subculture, centered on the British African-Caribbean sound system scene fueled underground after-parties that featured dance music exclusively. Also in 1988, the Balearic party vibe associated with Ibiza's DJ Alfredo was transported to London, when Danny Rampling and Paul Oakenfold opened the clubs Shoom and Spectrum, respectively. Both places became synonymous with acid house, and it was during this period that MDMA gained prominence as a party drug. Other important UK clubs included Back to Basics in Leeds, Sheffield's Leadmill and Music Factory, and The Haçienda in Manchester, where Mike Pickering and Graeme Park's spot, Nude, was an important proving ground for American underground dance music.[Note 1][54] The success of house and acid house paved the way for Detroit Techno, a style that was initially supported by a handful of house music clubs in Chicago, New York, and Northern England, with Detroit clubs catching up later.[55] The term Techno first came into use after a release of a 10 Records/Virgin Records compilation titled Techno: The Dance Sound of Detroit in 1988.[56]

One of the first Detroit productions to receive wider attention was Derrick May's "Strings of Life" (1987), which, together with May's previous release, "Nude Photo" (1987), helped raise techno's profile in Europe, especially the UK and Germany, during the 1987-1988 house music boom (see Second Summer of Love).[57] It became May's best known track, which, according to Frankie Knuckles, "just exploded. It was like something you can't imagine, the kind of power and energy people got off that record when it was first heard. Mike Dunn says he has no idea how people can accept a record that doesn't have a bassline."[58] According to British DJ Mark Moore, "Strings of Life" led London club goers to accept house: "because most people hated house music and it was all rare groove and hip hop...I'd play 'Strings of Life' at the Mudd Club and clear the floor".[59][Note 2] By the late 1980s interest in house, acid house and techno escalated in the club scene and MDMA-fueled club goers, who were faced with a 2 a.m. closing time in the UK, started to seek after-hours refuge at all-night warehouse parties. Within a year, in summer 1989, up to 10,000 people at a time were attending commercially organised underground parties called raves.[3]

Breakbeat hardcore, jungle, drum & bass

By the early 1990s, a style of music developed within the rave scene that had an identity distinct from American house and techno. This music, much like hip-hop before it, combined sampled syncopated beats or break beats, other samples from a wide range of different musical genres and, occasionally, samples of music, dialogue and effects from films and television programmes. Relative to earlier styles of dance music such as house and techno, so called 'rave music' tended to emphasise bass sounds and use faster tempos, or beats per minute (BPM). This subgenre was known as "hardcore" rave, but from as early as 1991, some musical tracks made up of these high-tempo break beats, with heavy basslines and samples of older Jamaican music, were referred to as "jungle techno", a genre influenced by Jack Smooth and Basement Records, and later just "jungle", which became recognized as a separate musical genre popular at raves and on pirate radio in Britain. It is important to note when discussing the history of drum & bass that prior to jungle, rave music was getting faster and more experimental.

By 1994, jungle had begun to gain mainstream popularity and fans of the music (often referred to as junglists) became a more recognisable part of youth subculture. The genre further developed, incorporating and fusing elements from a wide range of existing musical genres, including the raggamuffin sound, dancehall, MC chants, dub basslines, and increasingly complex, heavily edited breakbeat percussion. Despite the affiliation with the ecstasy-fuelled rave scene, Jungle also inherited some associations with violence and criminal activity, both from the gang culture that had affected the UK's hip-hop scene and as a consequence of jungle's often aggressive or menacing sound and themes of violence (usually reflected in the choice of samples). However, this developed in tandem with the often positive reputation of the music as part of the wider rave scene and dance hall-based Jamaican music culture prevalent in London. By 1995, whether as a reaction to, or independently of this cultural schism, some jungle producers began to move away from the ragga-influenced style and create what would become collectively labelled, for convenience, as drum and bass.[61]

Popularization in the United States

Initially, electronic dance music was associated with European rave and club culture. It achieved limited popular exposure in America but by the mid-to-late 1990s efforts were underway to market a range of dance genres using the label "electronica."[62] At the time, a wave of electronic music bands from the UK, including The Prodigy, The Chemical Brothers, Fatboy Slim and Underworld, had been prematurely associated with an "American electronica revolution".[63][64] But rather than finding mainstream success, many established EDM acts were relegated to the margins of the US industry.[63] In 1998 Madonna's Ray of Light brought the genre to the attention of popular music listeners.[65][66] In the late 1990s, despite US media interest in dance music re-branded as electronica, American house and techno producers continued to travel abroad to establish their careers as DJs and producers.[63]

By the mid 2000s Dutch producer Tiësto was bringing worldwide popular attention to EDM after providing a soundtrack to the entry of athletes during the opening ceremony of the 2004 Summer Olympics — an event which The Guardian deemed as one of the 50 most important events in dance music.[67] By 2005, the prominence of dance music in North American popular culture had markedly increased. According to Spin, Daft Punk's performance at Coachella in 2006 was the "tipping point" for EDM—it introduced the duo to a new generation of "rock kids".[63] As noted by Entertainment Weekly, Justin Timberlake's "SexyBack" helped introduce EDM sounds to top 40 radio, as it brought together variations of electronic dance music with the singer’s R&B sounds.[68][69] In 2009, French house musician David Guetta began to gain prominence in mainstream pop music thanks to several crossover hits on Top 40 charts such as "When Love Takes Over" with Kelly Rowland,[70] as well as his collaborations with US pop and hip hop acts such as Akon ("Sexy Bitch") and The Black Eyed Peas ("I Gotta Feeling").[71] YouTube and SoundCloud helped fuel interest in EDM, as well as electro house and dubstep. Skrillex popularized a harsher sound nicknamed "brostep", or dubstep.[2][72]

The increased popularity of EDM was also influenced by live events and gigs. Promoters and venues realized that DJs could generate larger profits than traditional musicians; Diplo explained that "a band plays [for] 45 minutes; DJs can play for four hours. Rock bands—there's a few headliner dudes that can play 3,000-4,000-capacity venues, but DJs play the same venues, they turn the crowd over two times, people buy drinks all night long at higher prices—it's a win-win."[63] Electronic music festivals notably the Electric Daisy Carnival (EDC) and Ultra Music Festival also grew in size, placing an increased emphasis on visual experiences, and the DJs themselves, who began to attain a celebrity status.[2][72] Other major acts that gained prominence including Avicii and Swedish House Mafia held concert tours at arenas rather than nightclubs; in December 2011, Swedish House Mafia became the first electronic music act to sell out New York City's Madison Square Garden.[72]

In 2011, Spin declared a "new rave generation" led by acts like David Guetta, Deadmau5, and Skrillex.[63] In January 2013, Billboard introduced a new EDM-focused Dance/Electronic Songs chart, tracking the top 50 electronic songs based on sales, radio airplay, club play, and online streaming.[73] According to Eventbrite, EDM fans are more likely to use social media to discover and share events or gigs. They also discovered that 78% of fans say they are more likely to attend an event if their peers do, compared to 43% of fans in general. EDM has many young and social fans.[74][74] By late 2011, Music Trades was describing electronic dance music as the fastest-growing genre in the world.[75] Elements of electronic music also became increasingly prominent in pop music.[63] Radio and television also contributed to dance music's mainstream acceptance.[76]

US corporate interest

Corporate consolidation in the EDM industry began in 2012—especially in terms of live events. In June 2012, media executive Robert F. X. Sillerman—founder of what is now Live Nation—re-launched SFX Entertainment as an EDM conglomerate, and announced his plan to invest $1 billion to acquire EDM businesses. His acquisitions included regional promoters and festivals (including ID&T, which organises Tomorrowland), two nightclub operators in Miami, and Beatport, an online music store which focuses on electronic music.[77][78] Live Nation also acquired Cream Holdings and Hard Events, and announced a "creative partnership" with EDC organizers Insomniac Events in 2013 that would allow it to access its resources whilst remaining an independent company;[79] Live Nation CEO Michael Rapino described EDM as the "[new] rock 'n' roll".[62][80][81]

US radio conglomerate iHeartMedia, Inc. (formerly Clear Channel Media and Entertainment) also made efforts to align itself with EDM. In January 2014 It hired noted British DJ and BBC Radio 1 personality Pete Tong to produce programming for its "Evolution" dance radio brand,[82] and announced a partnership with SFX to co-produce live concerts and EDM-oriented original programming for its top 40 radio stations. iHeartMedia president John Sykes explained that he wanted his company's properties to be the "best destination [for EDM]".[83][84]

Major brands have also used the EDM phenomena as a means of targeting millennials[85][86] and EDM songs and artists have increasingly been featured in television commercials and programs.[87] Avicii's manager Ash Pournouri compared these practices to the commercialization of hip-hop in the early 2000s.[87] Heineken has a marketing relationship with the Ultra Music Festival, and has incorporated Dutch producers Armin van Buuren and Tiësto into its ad campaigns. Anheuser-Busch has a similar relationship as beer sponsor of SFX Entertainment events.[87] In 2014, 7 Up launched "7x7Up"—a multi-platform campaign centered around EDM that includes digital content, advertising featuring producers, and branded stages at both Ultra and Electric Daisy Carnival.[85][88][89] Wireless carrier T-Mobile US entered into an agreement with SFX to become the official wireless sponsor of its events, and partnered with Above & Beyond to sponsor its 2015 tour.[86]

In August 2015, SFX began to experience declines in its value,[90] and a failed bid by CEO Sillerman to take the company private. The company began looking into strategic alternatives that could have resulted in the sale of the company.[91][92] In October 2015, Forbes declared the possibility of an EDM "bubble", in the wake of the declines at SFX Entertainment, slowing growth in revenue, the increasing costs of organizing festivals and booking talent, as well as an oversaturation of festivals in the eastern and western United States. Insomniac CEO Pasquale Rotella felt that the industry would weather the financial uncertainty of the overall market by focusing on "innovation" and entering into new markets.[93] Despite forecasts that interest in popular EDM would wane, in 2015 it was estimated to be a £5.5bn industry in the US, up by 60% compared to 2012 estimates.[94]

SFX emerged from bankruptcy in December 2016 as LiveStyle, under the leadership of Randy Phillips, a former executive of AEG Live.[95][96]

International popularisation

In May 2015, the International Music Summit's Business Report estimated that the global electronic music industry had reached nearly $6.9 billion in value; the count included music sales, events revenue (including nightclubs and festivals), the sale of DJ equipment and software, and other sources of revenue. The report also identified several emerging markets for electronic dance music, including East Asia, India, and South Africa, credited primarily to investment by domestic, as well as American and European interests. A number of major festivals also began expanding into Latin America.[97]

China is a market where EDM had initially made relatively few inroads; although promoters believed that the mostly instrumental music would remove a metaphorical language barrier, the growth of EDM in China was hampered by the lack of a prominent rave culture in the country as in other regions, as well as the popularity of domestic Chinese pop over foreign artists. Former Universal Music executive Eric Zho, inspired by the US growth, made the first significant investments in electronic music in China, including the organisation of Shanghai's inaugural Storm festival in 2013, the reaching of a title sponsorship deal for the festival with Anheuser-Busch's Budweiser brand, a local talent search, and organising collaborations between EDM producers and Chinese singers, such as Avicii and Wang Leehom's "Lose Myself". In the years following, a larger number of EDM events began to appear in China, and Storm itself was also preceded by a larger number of pre-parties in 2014 than its inaugural year. A new report released during the inaugural International Music Summit China in October 2015 revealed that the Chinese EDM industry was experiencing modest gains, citing the larger number of events (including new major festival brands such as Modern Sky and YinYang), a 6% increase in the sales of electronic music in the country, and the significant size of the overall market. Zho also believed that the country's "hands-on" political climate, as well as investments by China into cultural events, helped in "encouraging" the growth of EDM in the country.[98][99]

Criticism

Following the popularization of EDM in America a number of producers and DJs, including Carl Cox, Steve Lawler, and Markus Schulz, raised concerns that the perceived over-commercialisation of dance music had impacted the "art" of DJing. Cox saw the "press-play" approach taken by newer EDM DJs as unrepresentative of what he called a "DJ ethos".[72] Writing in Mixmag, DJ Tim Sheridan argued that "push-button DJs" who use auto-sync and play pre-recorded sets of "obvious hits" resulted in a situation overtaken by "the spectacle, money and the showbiz".[100]

Some house producers openly admitted that "commercial" EDM needed further differentiation and creativity. Avicii, whose 2013 album True featured songs incorporating elements of bluegrass, such as lead single "Wake Me Up", stated that most EDM lacked "longevity".[101] Deadmau5 criticized the homogenization of popular EDM, and suggested that it "all sounds the same." During the 2014 Ultra Music Festival, Deadmau5 made critical comments about up-and-coming EDM artist Martin Garrix and later played an edited version of Garrix's "Animals" remixed to the melody of "Old McDonald Had a Farm". Afterwards, Tiësto criticized Deadmau5 on Twitter for "sarcastically" mixing Avicii's "Levels" with his own "Ghosts 'n' Stuff".[102][103][104][105]

In May 2014, the NBC comedy series Saturday Night Live parodied the stereotypes of EDM culture and push-button DJs in a Digital Short entitled "When Will the Bass Drop?". It featured a DJ who goes about performing everyday activities—playing a computer game, frying eggs, collecting money—who then presses a giant "BASS" button, which explodes the heads of concertgoers.[106][107][108]

Terminology

The term "electronic dance music" (EDM) was used in the United States as early as 1985, although the term "dance music" did not catch on as a blanket term [95]. Writing in The Guardian, journalist Simon Reynolds noted that the American music industry's adoption of the term EDM in the late 2000s was an attempt to re-brand US "rave culture" and differentiate it from the 1990s rave scene. In the UK, "dance music" or "dance" are more common terms for EDM.[4]What is widely perceived to be "club music" has changed over time; it now includes different genres and may not always encompass EDM. Similarly, "electronic dance music" can mean different things to different people. Both "club music" and "EDM" seem vague, but the terms are sometimes used to refer to distinct and unrelated genres (club music is defined by what is popular, whereas EDM is distinguished by musical attributes).[96] Until the late 1990s, when the larger US music industry created music charts for "dance" (Billboard magazine has maintained a "dance" chart since 1974 and it continues to this day.).[93] In July 1995, Nervous Records and Project X Magazine hosted the first awards ceremony, calling it the "Electronic Dance Music Awards".[Note 4]

Genres

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2016) |

According to author Steve Taylor[109] Afrika Bambaataa's 1982 electro (short for "electro-funk") album Planet Rock serves as a "template for all interesting dance music since".[109] Various EDM genres have evolved over the last 30 years, for example; electro, house, techno hardcore, trance, drum and bass etc. Stylistic variation within an established EDM genre can lead to the emergence of what is called a subgenre. Hybridization, where elements of two or more genres are combined, can lead to the emergence of an entirely new genre of EDM.[110]

Production

Electronic dance music is generally composed and produced in a recording studio with specialized equipment such as samplers, synthesizers, effects units and MIDI controllers all set up to interact with one another using the MIDI protocol. In the genre's early days, hardware electronic musical instruments were used and the focus in production was mainly on manipulating MIDI data as opposed to manipulating audio signals. However, since the late 1990s the use of software has been increasing. A modern electronic music production studio generally consists of a computer running a digital audio workstation (DAW), with various plug-ins installed such as software synthesizers and effects units, which are controlled with a MIDI controller such as a MIDI keyboard. This setup suffices for a producer to create an entire track from start to finish, ready to be mastered.[111]

Festivals

In the 1980s, electronic dance music was often played at illegal underground rave parties held in secret locations, for example, warehouses, abandoned aircraft hangars, fields and any other large, open areas. In the 1990s and 2000s, aspects of the underground rave culture of the 1980s and early 1990s began to evolve into legitimate, organized EDM concerts and festivals. Major festivals often feature a large number of acts representing various EDM genres spread across multiple stages. Festivals have placed a larger emphasis on visual spectacles as part of their overall experiences, including elaborate stage designs with underlying thematics, complex lighting systems, laser shows, and pyrotechnics. Rave fashion also evolved among attendees, which The Guardian described as progressing from the 1990s "kandi raver" to "[a] slick and sexified yet also kitschy-surreal image midway between Venice Beach and Cirque du Soleil, Willy Wonka and a gay pride parade."[2][72][88] These events differed from underground raves by their organized nature, often taking place at major venues, and measures to ensure the health and safety of attendees.[112] MTV's Rawley Bornstein described electronic music as "the new rock and roll",[113] as has Lollapalooza organizer Perry Ferrell.[114]

Ray Waddell of Billboard noted that festival promoters have done an excellent job at branding.[113] Larger festivals have been shown to have positive economic impacts on their host cities[112] the 2014 Ultra Music Festival brought 165,000 attendees—and over $223 million—to the Miami/South Florida region's economy.[89] The inaugural edition of TomorrowWorld—a US-based version of Belgium's Tomorrowland festival, brought $85.1 million to the Atlanta area—as much revenue as its hosting of the NCAA Final Four (the national championship of US college basketball) earlier in the year.[115] The increasing mainstream prominence of electronic music has also led major US multi-genre festivals, such as Lollapalooza and Coachella, to add more electronic and dance acts to their lineups, along with dedicated, EDM-oriented stages. Even with these accommodations, some major electronic acts, such as Deadmau5 and Calvin Harris have made appearances on main stages during the final nights of Lollapalooza and Coachella, respectively—spots traditionally reserved for prominent non-electronic genres, such as rock and alternative.[116][117]

Russell Smith of The Globe and Mail felt that the commercial festival industry was an antithesis to the original principles of the rave subculture, citing "the expensive tickets, the giant corporate sponsors, the crass bro culture—shirtless muscle boys who cruise the stadiums, tiny popular girls in bikinis who ride on their shoulders – not to mention the sappy music itself."[118] Drug-related incidents, as well as other complaints surrounding the behaviour of their attendees, have contributed to negative perceptions and opposition to electronic music events by local authorities;[118][119] After Ultra Music Festival 2014, where a crowd of gatecrashers trampled a security guard on its first day, Miami's city commissioners considered banning the festival from being held in the city, citing the trampling incident, lewd behavior, and complaints by downtown residents of being harassed by attendees. The commissioners voted to allow Ultra to continue being held in Miami due to its positive economic effects, under the condition that its organizers address security, drug usage and lewd behavior by attendees.[120][121][122]

Association with recreational drug use

Dance music has a long association with recreational drug use,[123] particularly with a wide range of drugs that have been categorized under the name "club drugs". Russell Smith noted that the association of drugs and music subcultures was by no means exclusive to electronic music, citing previous examples of music genres that were associated with certain drugs, such as psychedelic rock and LSD, disco music and cocaine, and punk music and heroin.[118] Similarly, the 1980s grunge scene in Seattle was associated with heroin use.

Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), also known as ecstasy, "E", or "Molly", is often considered the drug of choice within the rave culture and is also used at clubs, festivals and house parties.[124] In the rave environment, the sensory effects from the music and lighting are often highly synergistic with the drug. The psychedelic amphetamine quality of MDMA offers multiple reasons for its appeals to users in the "rave" setting. Some users enjoy the feeling of mass communion from the inhibition-reducing effects of the drug, while others use it as party fuel because of the drug's stimulatory effects.[125]

MDMA is occasionally known for being taken in conjunction with psychedelic drugs. The more common combinations include MDMA combined with LSD, MDMA with psilocybin mushrooms, and MDMA with the disassociative drug ketamine. Many users use mentholated products while taking MDMA for its cooling sensation while experiencing the drug's effects. Examples include menthol cigarettes, Vicks VapoRub, NyQuil,[126] and lozenges.

The incidence of nonmedical ketamine has increased in the context of raves and other parties.[127] However, its emergence as a club drug differs from other club drugs (e.g. MDMA) due to its anesthetic properties (e.g., slurred speech, immobilization) at higher doses;[128] in addition, there are reports of ketamine being sold as "ecstasy".[129] The use of ketamine as part of a "postclubbing experience" has also been documented.[130] Ketamine's rise in the dance culture was rapid in Hong Kong by the end of the 1990s.[128] Before becoming a federally controlled substance in the United States in 1999, ketamine was available as diverted pharmaceutical preparations and as a pure powder sold in bulk quantities from domestic chemical supply companies.[131] Much of the current ketamine diverted for nonmedical use originates in China and India.[131]

Drug-related deaths at electronic dance music events

A number of deaths attributed to apparent drug use have occurred at major electronic music concerts and festivals. The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum blacklisted Insomniac Events after an underaged attendee died from "complications of ischemic encephalopathy due to methylenedioxymethamphetamine intoxication" during Electric Daisy Carnival 2010; as a result, the event was re-located to Las Vegas the following year.[132][112][133][134][135] Drug-related deaths during Electric Zoo 2013 in New York City, United States, and Future Music Festival Asia 2014 in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, prompted the final day of both events to be cancelled,[134][136] while Life in Color cancelled a planned event in Malaysia out of concern for the incident at Future Music Festival Asia and other drug-related deaths that occurred at the A State of Trance 650 concerts in Jakarta, Indonesia.[137][138][139]

In September 2016, the city of Buenos Aires, Argentina banned all electronic music events, pending future legislation, after five drug-related deaths and four injuries at a Time Warp Festival event in the city in April 2016. The ban forced electronic band Kraftwerk to cancel a planned concert in the city, despite arguing that there were dissimilarities between a festival and their concerts.[140][141]

Industry awards

| Organization | Award | Years | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRIT Awards | British Dance Act | 1994–2004 | The BRIT awards in the UK introduced a "British Dance Act" category in 1994, first won by M People. Although dance acts had featured in the awards in previous years, this was the first year dance music was given its own category. More recently the award was removed as was "Urban" and "Rock" and other genres as the awards removed Genre-based awards and moved to more generalised artist-focused awards. |

| Grammy Award | Best Dance Recording | 1998–present | Most recently won (2017) by The Chainsmokers for Don't Let Me Down featuring Daya. |

| Grammy Award | Best Dance/Electronica Album | 2005–present | Most recently won (2017) by Flume for Skin |

| DJ Mag | Top 100 DJs poll | 1991–present | The British dance music magazine DJ Mag publishes a yearly listing of the top 100 DJs in the world; from 1991 to 1996 the Top 100 poll were ranked by the magazine's journalists; in 1997 the poll became a public vote. The current number-one as of the 2016 list is Martin Garrix. |

| DJ Awards | Best DJ Award | 1998–present | The only global DJ awards event that nominates and awards international DJ's in 11 categories held annually in Ibiza, Spain, winners selected by a public vote[142] and one of the most important[143] |

| Winter Music Conference (WMC) | IDMA: International Dance Music Awards | 1998–Present | [144] |

| Project X Magazine | Electronic Dance Music Awards | 1995 | Readers of Project X magazine voted for the winners of the first (and only) "Electronic Dance Music Awards".[145] In a ceremony organized by the magazine and Nervous Records, award statues were given to Winx, The Future Sound of London, Moby, Junior Vasquez, Danny Tenaglia, DJ Keoki, TRIBAL America Records and Moonshine Records.[145] |

| American Music Awards | Favorite Electronic Dance Music Artist | 2012–present | [146] |

| World Music Awards | Best DJ and Best Dance Music Artist | 2006–present | [147][148] |

See also

- Timeline of electronic music genres

- List of electronic dance music record labels

- List of electronic musicians

- List of electronic dance music venues

- Freetekno

- Rave music

- Remix

Notes

- ^ Fikentscher (2000), p. 5 harvp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFikentscher2000 (help), in discussing the definition of underground dance music as it relates to post-disco music in America, states that: "The prefix 'underground' does not merely serve to explain that the associated type of music—and its cultural context—are familiar only to a small number of informed persons. Underground also points to the sociological function of the music, framing it as one type of music that in order to have meaning and continuity is kept away, to large degree, from mainstream society, mass media, and those empowered to enforce prevalent moral and aesthetic codes and values."

- ^ "Although it can now be heard in Detroit's leading clubs, the local area has shown a marked reluctance to get behind the music. It has been in clubs like the Powerplant (Chicago), The World (New York), The Hacienda (Manchester), Rock City (Nottingham) and Downbeat (Leeds) where the techno sound has found most support. Ironically, the only Detroit club which really championed the sound was a peripatetic party night called Visage, which unromantically shared its name with one of Britain's oldest new romantic groups".[60]

References

- ^ [1] [permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f "How Rave Music Conquered America". The Guardian. August 2, 2012.

- ^ a b Koskoff (2004), p. 44

- ^ Butler (2006), pp. 12–13, 94

- ^ "Definition". Dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2017-07-09.

- ^ "Is EDM a Real Genre?". Noisey. Vice. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ RA Roundtable: EDM in AmericaResident Advisor. "RA Roundtable: EDM in America". N. p., 2012. Web. 18 May. 2014.

- ^ "The FACT Dictionary: How 'Dubstep', 'Juke', 'Cloud Rap' and Many More Got Their Names'", FACT Mag, July 10, 2013.

- ^ "Hardstyle music’s growing influence" Dailytrojan, Web. Mar 3, 2014.

- ^ EDM - ELECTRONIC DANCE MUSIC, Armada Music

- ^ Richard James Burgess (2014), The History of Music Production, page 115, Oxford University Press

- ^ "King Tubby's Meets Rockers Uptown - Augustus Pablo". Allmusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- ^ a b c Michael Veal (2013), Dub: Soundscapes and Shattered Songs in Jamaican Reggae, pages 26-44, "Electronic Music in Jamaica", Wesleyan University Press

- ^ Michael Veal (2013), Dub: Soundscapes and Shattered Songs in Jamaican Reggae, pages 85-86, Wesleyan University Press

- ^ Nicholas Collins, Margaret Schedel, Scott Wilson (2013), Electronic Music: Cambridge Introductions to Music, page 20, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Holmes, Thom (2008). Electronic and Experimental Music: Technology, Music, and Culture. Routledge. p. 403. ISBN 0203929594. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ Toop, David (1995). Ocean of Sound. Serpent's Tail. p. 115. ISBN 9781852423827.

- ^ a b Arthur P. Molella, Anna Karvellas (2015),"Places of Invention," Smithsonian Institution, p.47.

- ^ Nicholas Collins, Margaret Schedel, Scott Wilson (2013), Electronic Music: Cambridge Introductions to Music, page 105, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Six Machines That Changed The Music World, Wired, May 2002

- ^ Martin Russ (2012), Sound Synthesis and Sampling, page 83, CRC Press

- ^ a b Mike Collins (2014), In the Box Music Production: Advanced Tools and Techniques for Pro Tools, page 320, CRC Press

- ^ a b c Alice Echols (2010), Hot Stuff: Disco and the Remaking of American Culture, page 21, W. W. Norton & Company

- ^ a b Alice Echols (2010), Hot Stuff: Disco and the Remaking of American Culture, page 250, W. W. Norton & Company

- ^ Biddu Orchestra – Bionic Boogie at Discogs

- ^ Biddu Orchestra – Soul Coaxing at Discogs

- ^ "Futuristic Journey And Eastern Man CD". CD Universe. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ Biddu Orchestra – Futuristic Journey at Discogs (list of releases)

- ^ Futuristic Journey and Eastern Man at AllMusic

- ^ "Chart Search: Billboard". billboard.com.

- ^ Shapiro, Peter (2000). Modulations: A History of Electronic Music. Caipirinha Productions, Inc. pp. 254 pages. ISBN 978-0-8195-6498-6. see p.45, 46

- ^ "ARTS IN AMERICA; Here's to Disco, It Never Could Say Goodbye". New York Times. 10 December 2002.

- ^ Kenneth Lobo, EDM Nation: How India Stopped Worrying About the Riff and Fell in Love With the Beat, Rolling Stone

- ^ a b Geeta Dayal (6 April 2010). "Further thoughts on '10 Ragas to a Disco Beat'". The Original Soundtrack. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ a b Geeta Dayal (29 August 2010). "'Studio 84′: Digging into the History of Disco in India". The Original Soundtrack. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ William Rauscher (12 May 2010). "Charanjit Singh – Synthesizing: Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat". Resident Advisor. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ Smith, Ben (August 20, 2014). "Meghan Trainor Helps Count Down 10 Songs That Are All About That Bass". VH1 Music. Viacom Media Networks. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

This post-disco pop funk epic is centered on a relentless, repeating bassline that really does make you want to, uh, groove.

- ^ a b c "The Wire, Volumes 143-148", The Wire, p. 21, 1996, retrieved 2011-05-25 (see online link)

- ^ "Zapp". Vibe. 6: 84. August 1999.

- ^ a b "Electro-Funk > WHAT DID IT ALL MEAN ?". Greg Wilson on electrofunkroots.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ^ "Electro". Allmusic. Retrieved 2012-06-20.

- ^ "Slaves to the rhythm". CBC News. November 28, 2008. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Roy, Ron; Borthwick, Stuart (2004). Popular Music Genres: An Introduction. Edinburgh University Press. p. 255. ISBN 9780748617456.

- ^ Rickey Vincent. "Funk: The Music, The People, and The Rhythm of The One". Books.google.co.uk. p. 289. Retrieved 2017-07-08.

- ^ Mitchell, Euan. Interviews: Marshall Jefferson 4clubbers.net [dead link]

- ^ "Finding Jesse – The Discovery of Jesse Saunders As the Founder of House". Fly Global Music Culture. 2004-10-25. Archived from the original on 2012-03-22. Retrieved 2012-08-14.

- ^ Paoletta, Michael (1989-12-16). "Back To Basics". Dance Music Report: 12.

- ^ Fikentscher, Kai (July–August 2000). "The club DJ: a brief history of a cultural icon" (PDF). UNESCO Courier. UNESCO: 47.

Around 1986/7, after the initial explosion of house music in Chicago, it became clear that the major recording companies and media institutions were reluctant to market this genre of music, associated with gay African Americans, on a mainstream level. House artists turned to Europe, chiefly London but also cities such as Amsterdam, Berlin, Manchester, Milan, Zurich, and Tel Aviv. ... A third axis leads to Japan where, since the late 1980s, New York club DJs have had the opportunity to play guest-spots.

- ^ Sicko 2010:68

- ^ "What Is Balearic Beat? - BOILER ROOM". BOILER ROOM. 2014-07-12. Retrieved 2016-10-28.

- ^ Warren, Emma (2007-08-12). "The birth of rave". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-10-28.

- ^ "Amnesia - history". www.amnesia.es. Retrieved 2016-10-28.

- ^ Rietveld (1998), pp. 40–50

- ^ Rietveld (1998), pp. 54–59

- ^ Brewster (2006), pp. 398–443

- ^ Reynolds (1999:71) notes that: "Detroit's music had hitherto reached British ears as a subset of Chicago house; [Neil] Rushton and the Belleville Three decided to fasten on the word techno – a term that had been bandied about but never stressed – in order to define Detroit as a distinct genre." Reynolds, S., Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture, Routledge, New York 1999 (ISBN 978-0415923736)

- ^ Unterberger R., Hicks S., Dempsey J, (1999). Music USA: The Rough Guide, Rough Guides Ltd; illustrated edition.(ISBN 9781858284217)

- ^ "Interview: Derrick May—The Secret of Techno". Mixmag. 1997. Archived from the original on 14 February 2004. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Brewster (2006), p. 419

- ^ Cosgrove 1988a [citation needed]

- ^ Reynolds, Simon (2013). Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture. Soft Skull Press.

So when I talk about the vibe disappearing from drum and bass, I'm talking about the blackness going as the ragga samples get phased out, the bass loses its reggae feels and becomes more linear and propulsive rather than moving around the beat with a syncopated relation with the drum.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Ben Sisario (April 4, 2012). "Electronic Dance Concerts Turn Up Volume, Tempting Investors". New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sherburne, Philip. "Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger", Spin Magazine, pages 41-53, October 2011

- ^ Chaplin, Julia & Michel, Sia. "Fire Starters", Spin Magazine, page 40, March 1997, Spin Media LLC.

- ^ The 30 Greatest EDM Albums of All Time, Rolling Stone, 2 August 2012

- ^ Ray of Light—Madonna Allmusic

- ^ "A history of dance music: Tiësto DJs at the Athens Olympics opening ceremony". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ Goodman, Jessica (July 8, 2016). "Justin Timberlake explains how David Bowie influenced 'SexyBack'". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- ^ Craddock, Lauren (July 8, 2016). "How David Bowie Inspired Justin Timberlake's 'SexyBack'". Billboard. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- ^ CNN, Abel Alvarado. "It's a $6.2B industry but, how did EDM get so popular?". CNN. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "DJ David Guetta leads the EDM charge into mainstream". USA Today. June 5, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Jim Fusilli (June 6, 2012). "The Dumbing Down of Electronic Dance Music". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "New Dance/Electronic Songs Chart Launches With Will.i.am & Britney at No. 1". Billboard. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ a b Peoples, Glenn. "EDM's Social Dance." Billboard: The International Newsweekly of Music, Video and Home Entertainment Jul 06 2013: 8. ProQuest. Web. 20 July 2015 .

- ^ "Just How Big is EDM?". Music Trades Magazine. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ^ "The Year EDM Sold Out: Swedish House Mafia, Skrillex and Deadmau5 Hit the Mainstream". Billboard. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ "Exclusive: SFX Acquires ID&T, Voodoo Experience". Billboard. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ "SFX Purchases 75% Stake in ID&T, Announce U.S. Edition of Tomorrowland at Ultra". Billboard. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ^ Zel McCarthy (June 20, 2013). "Live Nation Teams With Insomniac Events in 'Creative Partnership'". Billboard.

- ^ "Live Nation Acquires L.A. EDM Promoter HARD: Will the Mainstream Get More Ravey?". Spin. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ Dan Rys (May 9, 2012). "Live Nation Buys EDM Entertainment Company Cream Holdings Ltd, Owner of Creamfields Festivals". Billboard.

- ^ Ben Sisario (December 20, 2012). "Boston Radio Station Switches to Electronic Dance Format". New York Times.

- ^ Kerri Mason (January 6, 2014). "SFX and Clear Channel Partner for Digital, Terrestrial Radio Push". Billboard.

- ^ Kerri Mason (January 6, 2014). "John Sykes, Robert Sillerman on New Clear Channel, SFX Partnership: 'We Want to Be the Best'". Billboard.

- ^ a b "7Up Turns to Electronic Dance Music to Lift Spirits -- and Sales". Advertising Age. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ a b "Exclusive: Bolstering Massive EDM Strategy, T-Mobile Debuts Above & Beyond Video Series". Billboard. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ a b c "Booming business: EDM goes mainstream". Miami Herald. March 26, 2014.

- ^ a b Valerie Lee (June 27, 2014). "An Electric Desert Experience: The 2014 EDC Las Vegas Phenomenon". Dancing Astronaut.

- ^ a b Roy Trakin (April 3, 2014). "Ultra Music Festival's 16th Anything but Sweet, Though Still Potent". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Mac, Ryan. "The Fall Of SFX: From Billion-Dollar Company To Bankruptcy Watch". Forbes. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (14 August 2015). "SFX Entertainment Is Back on the Block". Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ Faughnder, Ryan (14 August 2015). "After failed CEO takeover bid, what's next for SFX Entertainment?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ "The $6.9 Billion Bubble? Inside The Uncertain Future Of EDM". Forbes. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ Blake, Jimmy (July 2016). "Has EDM opened doors or slammed them shut in dance music?". Retrieved 2016-10-08.

- ^ "SFX Entertainment Emerges From Bankruptcy With New Name: LiveStyle". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ "SFX Emerges From Bankruptcy with a New Name, LiveStyle, and New Leader in Randy Phillips". Billboard. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ "Electronic Music Industry Now Worth Close to $7 Billion Amid Slowing Growth". Thump. Vice Media. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ Hannah Karp (October 5, 2014). "In China, Concert Promoter Wants EDM in the Mix". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Is the EDM Scene in China about to Pop Off?". Thump. Vice Media. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ "Is EDM killing the art of DJing?". Mixmag. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "EDM Will Eat Itself: Big Room stars are getting bored". Mixmag. Archived from the original on 18 January 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Deadmau5 Trolls Martin Garrix with 'Old MacDonald Had a Farm' Remix of 'Animals' at Ultra". radio.com. March 31, 2014.

- ^ "Deadmau5 gives reason for techno track: "EDM sounds the same to me"". Mixmag. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ "Deadmau5: The Man Who Trolled the World". Mixmag. Archived from the original on 25 April 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Afrojack and Deadmau5 argue over what's "good music"". Mixmag. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "SNL Digital Shorts return with 'Davvincii' to skewer EDM and overpaid DJs". The Verge. May 18, 2014.

- ^ "Watch Saturday Night Live Mock Big Room DJ Culture". Mixmag. Archived from the original on 5 June 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "SNL takes stab at EDM culture in new digital short featuring 'Davvincii'". Dancing Astronaut. May 2014.

- ^ a b Taylor, Steve (2004). The A to X of alternative music (2nd ed., reprint ed.). London: Continuum. p. 25. ISBN 9780826482174.

- ^ Kembrew McLeod (2001). "Genres, Subgenres, Sub-Subgenres and More: Musical and Social Difference Within Electronic/Dance Music Communities" (PDF). Journal of Popular Music Studies. 13: 59–75. doi:10.1111/j.1533-1598.2001.tb00013.x.

- ^ Burgess, Richard James (2014). The History of Music Production. Oxford. pp. 136–146. ISBN 0199357161.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c "A fatal toll on concertgoers as raves boost cities' income". Los Angeles Times. February 3, 2013.

- ^ a b Lisa Rose, "N.J. basks in the glow of the brave new rave: Electronic dance festivals go mainstream", Newark Star Ledger, May 16, 2012.

- ^ Sarah Maloy (August 4, 2012). "Lollapalooza's Perry Farrell on EDM and Elevating the Aftershow: Video". Billboard.

- ^ Melissa Ruggieri (April 8, 2014). "Study: TomorrowWorld had $85m impact". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- ^ "House Music Comes Home: How Chicago's Summer of Music Festivals Has Reinvigorated the City's Dance Spirit". Noisey. Vice.

- ^ "How Coachella's final day symbolizes the electronic music fever pitch". Las Vegas Weekly. April 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Russell Smith: Exposés on EDM festivals shift long overdue blame". The Globe and Mail. July 12, 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ "Music festival safety recommendations come too late for family". CBC News. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ "Ultra Fest to Stay in Miami, City Commission Decides". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ "Miami Commission: Ultra stays in downtown Miami". Miami Herald. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ^ "Ultra Music Announces Review After Festival Security Draws Criticism". Billboard.com. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ P. Nash Jenkins. "Electronic Dance Music's Love Affair With Ecstasy: A History". The Atlantic.

- ^ Carvalho M, Carmo H, Costa VM, Capela JP, Pontes H, Remião F, Carvalho F, Bastos Mde L (August 2012). "Toxicity of amphetamines: an update". Arch. Toxicol. 86 (8): 1167–1231. doi:10.1007/s00204-012-0815-5. PMID 22392347.

MDMA has become a popular recreational drug of abuse at nightclubs and rave or techno parties, where it is combined with intense physical activity (all-night dancing), crowded conditions (aggregation), high ambient temperature, poor hydration, loud noise, and is commonly taken together with other stimulant club drugs and/or alcohol (Parrott 2006; Von Huben et al. 2007; Walubo and Seger 1999). This combination is probably the main reason why it is generally seen an increase in toxicity events at rave parties since all these factors are thought to induce or enhance the toxicity (particularly the hyperthermic response) of MDMA. ... Another report showed that MDMA users displayed multiple regions of grey matter reduction in the neocortical, bilateral cerebellum, and midline brainstem brain regions, potentially accounting for previously reported neuropsychiatric impairments in MDMA users (Cowan et al. 2003). Neuroimaging techniques, like PET, were used in combination with a 5-HTT ligand in human ecstasy users, showing lower density of brain 5-HTT sites (McCann et al. 1998, 2005, 2008). Other authors correlate the 5-HTT reductions with the memory deficits seen in humans with a history of recreational MDMA use (McCann et al. 2008). A recent study prospectively assessed the sustained effects of ecstasy use on the brain in novel MDMA users using repeated measurements with a combination of different neuroimaging parameters of neurotoxicity. The authors concluded that low MDMA dosages can produce sustained effects on brain microvasculature, white matter maturation, and possibly axonal damage (de Win et al. 2008).

- ^ Reynolds, Simon (1999). Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture. Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 0415923735.

- ^ "Director's Report to the National Advisory Council on Drug Abuse". National Institute on Drug Abuse. May 2000. Archived from the original on August 26, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Increased non-medical use references:

- Awuonda, M (13 July 1996). "Swedes alarmed at ketamine misuse". The Lancet. 348 (9020): 122. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)64628-4.

- Curran, HV; Morgan, C (April 2000). "Cognitive, dissociative and psychotogenic effects of ketamine in recreational users on the night of drug use and 3 days later". Addiction. 95 (4): 575–90. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9545759.x. PMID 10829333.

- Gahlinger, PM (1 June 2004). "Club drugs: MDMA, gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), Rohypnol, and ketamine". American Family Physician. 69 (11): 2619–26. PMID 15202696.

- Jansen, KL (6 March 1993). "Non-medical use of ketamine". BMJ. 306 (6878): 601–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.306.6878.601. PMC 1676978. PMID 8461808.

- Joe-Laider & Hunt 2008

- ^ a b Joe-Laidler, K; Hunt, G (1 June 2008). "Sit down to float: The cultural meaning of ketamine use in Hong Kong". Addiction Research & Theory. 16 (3): 259–71. doi:10.1080/16066350801983673. PMC 2744071. PMID 19759834.

- ^ Ketamine sold as "ecstasy" references:

- Tanner-Smith, EE (July 2006). "Pharmacological content of tablets sold as "ecstasy": Results from an online testing service" (PDF). Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 83 (3): 247–54. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.016. PMID 16364567.

- Copeland, J; Dillon, P (2005). "The health and psycho-social consequences of ketamine use". International Journal of Drug Policy. 16 (2): 122–31. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2004.12.003.

- Measham, Fiona; Parker, Howard; Aldridge, Judith (2001). Dancing on Drugs: Risk, Health and Hedonism in the British Club Scene. London: Free Association Books. ISBN 9781853435126.[verification needed][page needed]

- ^ Moore, K; Measham, F (2006). "Ketamine use: Minimising problems and maximising pleasure". Drugs and Alcohol Today. 6 (3): 29–32. doi:10.1108/17459265200600047.

- ^ a b Morris, H; Wallach, J (July 2014). "From PCP to MXE: A comprehensive review of the non-medical use of dissociative drugs". Drug Testing and Analysis. 6 (7–8): 614–32. doi:10.1002/dta.1620. PMID 24678061.

- ^ "'EDC' Raver Teen Sasha Rodriguez Died From Ecstasy Use". LA Weekly. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ "Man dies at Electric Daisy Carnival in Las Vegas". Chicago Tribune. June 22, 2014.

- ^ a b Jon Pareles (September 1, 2014). "A Bit of Caution Beneath the Thump". New York Times.

- ^ "Electric Zoo to Clamp Down on Drugs This Year". Wall Street Journal. 28 August 2014.

- ^ "Six dead from 'meth' at Future Music Festival Asia 2014: police". Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ "Blanked out: Life In Color cancelled due to drug deaths". Malaysia Star. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ "Police Probe 'A State of Trance' Festival Drug Deaths". Jakarta Globe. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ "Three Dead After State of Trance Festival in Jakarta, Drugs Suspected". Spin.com. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ "Kraftwerk Can't Play Buenos Aires Concert Due to Electronic Music Ban: Report". Billboard. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ "Buenos Aires bans electronic music festivals after five deaths". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ Rodriguez, Krystal (23 September 2014). "Here are the winners of this year's Ibiza DJ Awards". In the Mix Webzine Australia.

- ^ Zalokar, Gregor. "DJ Awards 2014 Winners". EMF Magazine. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ "30th Annual International Dance Music Awards—Winter Music Conference 2015—WMC 2015". Winter Music Conference.

- ^ a b Larry Flick (August 12, 1995). "Gonzales Prepares More Batches of Bucketheads". Billboard: 24.

- ^ "American Music Awards 2012: A big night for Justin Bieber". CBS News. November 18, 2012.

- ^ "Choose your Nomination Category". worldmusicawards.com. World Music Awards. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Best Dance Music Artist". worldmusicawards.com. World Music Awards. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Bibliography

- Butler, Mark Jonathan (2006). Unlocking the Groove: Rhythm, Meter, and Musical Design in Electronic Dance Music. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253346629.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fikentscher, Kai (2000). 'You Better Work'!: Underground Dance Music in New York. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 9780819564047.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Koskoff, Ellen (2004). Music Cultures in the United States: an Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 9780415965897.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rietveld, Hillegonda C. (1998). This is Our House: House Music, Cultural Spaces, and Technologies. Popular Cultural Studies. Vol. 13. Ashgate. ISBN 9781857422429.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Graham St John, editor. Weekend Societies: Electronic Dance Music Festivals and Event-Cultures, 2017, Bloomsbury Academic

Further reading

- Hewitt, Michael. Music Theory for Computer Musicians. 1st Ed. U.S. Cengage Learning, 2008. ISBN 978-1-59863-503-4

- "Electronic dance music glossary" by Moby for USA Today (December 13, 2011)

- Simplified guide to the various EDM genres with sample tracks: "An Idiot's Guide to EDM Genres"

- Vice Magazine. 2013. Rave Culture, a handy guide for middle America: "Explaining Rave Culture to Americans"

- "Beat Explorers Dance Music Guide" from "BeatExplorers"