Taliban: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

[http://www.mcclatchydc.com/2008/09/10/52244/911-seven-years-later-us-safe.html 9/11 seven years later: U.S. 'safe,' South Asia in turmoil] ''"There are now some 62,000 foreign soldiers in Afghanistan, including 34,000 U.S. troops, and some 150,000 Afghan security forces. '''They face an estimated 7,000 to 11,000 insurgents''', according to U.S. commanders."'.' Retrieved 2010-08-24.</ref><br /> 36,000 (2010 est.).<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/afghanistan/article7047321.ece | location=London | work=The Times | title=MajorGeneral Richard Barrons puts Taleban fighter numbers at 36000 | date=March 3, 2010}}</ref> |

[http://www.mcclatchydc.com/2008/09/10/52244/911-seven-years-later-us-safe.html 9/11 seven years later: U.S. 'safe,' South Asia in turmoil] ''"There are now some 62,000 foreign soldiers in Afghanistan, including 34,000 U.S. troops, and some 150,000 Afghan security forces. '''They face an estimated 7,000 to 11,000 insurgents''', according to U.S. commanders."'.' Retrieved 2010-08-24.</ref><br /> 36,000 (2010 est.).<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/afghanistan/article7047321.ece | location=London | work=The Times | title=MajorGeneral Richard Barrons puts Taleban fighter numbers at 36000 | date=March 3, 2010}}</ref> |

||

|previous = Students of [[Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam]] |

|previous = Students of [[Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam]] |

||

|allies =[[ |

|allies =[[Pakistan]]<br />[[Haqqani network]]<br />[[Al-Qaeda]]<br />[[Hezb-e-Islami Gulbuddin]]<br />[[Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan]]<br />[[Islamic Emirate of Waziristan]]<br />[[Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan]]<br/> [[East Turkestan Islamic Movement]] |

||

|international = [[Pakistan]], [[Saudi Arabia]], [[United Arab Emirates]] |

|international = [[Pakistan]], [[Saudi Arabia]], [[United Arab Emirates]] |

||

|opponents = [[International Security Assistance Force|ISAF]] (led by [[NATO]])<br />[[Participants in Operation Enduring Freedom]] |

|opponents = [[International Security Assistance Force|ISAF]] (led by [[NATO]])<br />[[Participants in Operation Enduring Freedom]] |

||

Revision as of 19:33, 10 November 2010

| Taliban طالبان | |

|---|---|

Taliban flag | |

| Leaders | Mullah Mohammed Omar Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar Mullah Obaidullah Akhund |

| Dates of operation | September 1994 – December 2001 (government) 2004–present (Islamic Insurgency) |

| Active regions | Afghanistan and Pakistan[1] |

| Ideology | Islamism |

| Allies | Pakistan Haqqani network Al-Qaeda Hezb-e-Islami Gulbuddin Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan Islamic Emirate of Waziristan Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan East Turkestan Islamic Movement |

| Opponents | ISAF (led by NATO) Participants in Operation Enduring Freedom |

| Battles and wars | the Civil war in Afghanistan, the War in Afghanistan (2001–present) and the Waziristan War |

| Part of a series on the |

| Deobandi movement |

|---|

|

| Ideology and influences |

| Founders and key figures |

|

| Notable institutions |

| Centres (markaz) of Tablighi Jamaat |

| Associated organizations |

The Taliban, alternative spelling Taleban,[5] (Pashto: طالبان ṭālibān, meaning "students") is a hanafi Islamist political group that governed Afghanistan from 1996 until it was overthrown in late 2001. It has regrouped since 2004 and revived as a strong insurgency movement governing mainly local Pashtun areas, and fighting a guerrilla war against the governments of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF).[6] The Taliban movement is a tribal confederacy of Ghilzai and their allied tribes who are staunch Afghan/Pashtoon Nationalists (strictly follow the social cultural norm, called pashtoonwali) and are also Hanafi traditionalists (i.e., followers of Imam Abu Hanifa Madhhab). The Taliban movement is primarily made up of members belonging to ethnic Pashtun tribes,[7] along with volunteers from nearby Islamic countries such as Uzbeks, Tajiks, Punjabis, Arabs, Chechens, and others.[8][9][10] It operates in Afghanistan and Pakistan, mostly in provinces around the Durand Line border. U.S. officials say their headquarters is in or near Quetta, Pakistan, and that Pakistan and Iran provide support,[11][12][13][14][15] though both nations deny this.[16][17]

The main leader of the Taliban movement is Mullah Mohammed Omar, as to whom there is a $25 million reward for information leading to his capture, who is believed to be hiding in Afghanistan.[18][19] Omar's original commanders were "a mixture of former small-unit military commanders and madrassa teachers,"[20] while the Taliban's rank-and-file was made up mostly of Afghan refugees who had studied at Islamic religious schools in Pakistan.[citation needed] The Taliban received valuable training, supplies, and arms from the Pakistani government, particularly the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI),[21] and many recruits from madrasas for Afghan refugees in Pakistan, primarily ones established by the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI).[22]

Although in control of Afghanistan's capital (Kabul) and most of the country for five years, the Taliban regime, which called itself the "Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan", gained diplomatic recognition from only three states: Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates[citation needed]. It has regained some amount of political control and acceptance in Pakistan's border region, but lost one of its Pakistani leaders, Baitullah Mehsud, in a CIA missile strike.[23] Pakistan has launched an offensive to force the Taliban from its territory.[24]

While in power, the Taliban enforced one of the strictest interpretations of Sharia law ever seen in the Muslim world,[25] and became notorious internationally for their treatment of women.[26] Women were forced to wear the burqa in public.[27] They were allowed neither to work nor to be educated after the age of eight, and until then were permitted only to study the Qur'an.[26] They were not allowed to be treated by male doctors unless accompanied by a male chaperon, which led to illnesses remaining untreated. They faced public flogging in the street, and public execution for violations of the Taliban's laws.[28]

In mid-2009, the Taliban established an ombudsman office in northern Kandahar, which author David Kilcullen describes as a "direct challenge" to the ISAF.[29]

Etymology

The word Taliban is Pashto, طالبان ṭālibān, meaning "students", the plural of ṭālib. This is a loanword from Arabic طالب ṭālib,[30] plus the Indo-Iranian plural ending -an ان (the Arabic plural being طلاب ṭullāb, whereas طالبان ṭālibān is a dual form with the incongruous meaning, to Arabic speakers, of "two students"). Since becoming a loanword in English, Taliban, besides a plural noun referring to the group, has also been used as a singular noun referring to an individual. For example, John Walker Lindh has been referred to as "an American Taliban", rather than "an American Talib". In the English language newspapers of Pakistan the word talibans is often used when referring to more than one taliban. The spelling 'Taliban' has come to predominate over 'Taleban' in English.[31]

Early history

Emergence

At the conclusion of a speech given on September 26, 2008, at the Seattle Central Library, the journalist Robert Fisk related the account of one Captain Mainwaring given in the official British report of ca. 1882 on the Battle of Maiwand. It took place on July 27, 1880, during the Second Anglo-Afghan War. Mainwaring wrote of how particular Afghan fighters wearing black turbans would charge the British infantry lines and, upon reaching a British soldier, would proceed by cutting open his throat; of these suicidal Afghan fighters Mainwaring reveals 'they were called the Taliban'.[32]

After the withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1989 and the fall of the Afghan communist Najibullah-regime in 1992, the Afghan political parties agreed on a peace and power-sharing agreement (the Peshawar Accords). The Peshawar Accords created the Islamic State of Afghanistan and appointed an interim government for a transitional period. The interim government tried to initiate a process leading towards national elections, but Pakistan tried to install militia leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar as dictator in Kabul by starting a gruesome war before any government departments could be established by the interim government surrounding Ahmad Shah Massoud. Human Rights Watch writes: "The sovereignty of Afghanistan was vested formally in "The Islamic State of Afghanistan", an entity created in April 1992, after the fall of the Soviet-backed Najibullah government. ... With the exception of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami, all of the parties ... were ostensibly unified under this government in April 1992. ... Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami, for its part, refused to recognize the government for most of the period discussed in this report and launched attacks against government forces and Kabul generally. ... Shells and rockets fell everywhere."[33] Gulbuddin Hekmatyar was directed, funded and supplied by the Pakistani army.[34] Amin Saikal concludes in his book which was chosen by The Wall Street Journal as 'One of the "Five Best" Books on Afghanistan': "Pakistan was keen to gear up for a breakthrough in Central Asia. ... Islamabad could not possibly expect the new Islamic government leaders, especially [Ahmad Shah] Massoud (who had always maintained his independence from Pakistan), to subordinate their own nationalist objectives in order to help Pakistan realize its regional ambitions. ... Had it not been for the ISI's logistic support and supply of a large number of rockets, Hekmatyar's forces would not have been able to target and destroy half of Kabul."[35] Saudi Arabia and Iran also armed and directed Afghan militias.[35] A publication with the George Washington University describes: "[O]utside forces saw instability in Afghanistan as an opportunity to press their own security and political agendas."[36] According to Human Rights Watch, numerous Iranian agents were assisting the Shia Hezb-i Wahdat forces of Abdul Ali Mazari, as Iran was attempting to maximize Wahdat's military power and influence in the new government.[33][35][37] Saudi agents of some sort, private or governmental, were trying to strengthen the Wahhabi Abdul Rasul Sayyaf and his Ittihad-i Islami faction to the same end.[33][35] Horrific crimes were committed by individuals of different factions. Rare ceasefires, usually negotiated by representatives of Ahmad Shah Massoud, Sibghatullah Mojaddedi or Burhanuddin Rabbani (the interim government), or officials from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), commonly collapsed within days.[33]

Meanwhile southern Afghanistan was neither under the control of foreign-backed militias nor the interim government in Kabul, which had no hands in the affairs of southern Afghanistan during that time. Southern Afghanistan was ruled by local governors or armed groups. The southern city of Kandahar was filled with three different local Pashtun commanders Amir Lalai, Gul Agha Sherzai and Mullah Naqib Ullah who engaged in an extremely violent struggle for power and who were not affiliated with the interim government in Kabul. The bullet riddled city came to be a centre of lawlessness, crime and atrocities fuelled by complex Pashtun tribal rivalries. Mullah Omar, who once fought against the Soviets, started the movement with fewer than 50 armed madrassah students in his hometown of Kandahar. The most credible and often-repeated story of how Mullah Omar first mobilized his followers is that in the spring of 1994, neighbors in Singesar told him that the local governor had abducted two teenage girls, shaved their heads, and taken them to a camp where they were raped repeatedly. 30 Taliban (with only 16 rifles) freed the girls, and hanged the governor from the barrel of a tank. Later that year, two militia commanders killed civilians while fighting for the right to sodomize a young boy. The Taliban freed him.[38][39]

The Taliban's first major military activity was in 1994, when they marched northward from Maiwand and captured Kandahar City and the surrounding provinces, losing only a few dozen men.[40] They took-over a border crossing at Spin Baldak and an ammunition dump from Gulbuddin Hekmatyar on October 29. Kandahar fell November 3–5. A few weeks later, they freed "a convoy trying to open a trade route from Pakistan to Central Asia" from another group of militias attempting to extort money for permission to pass their checkpoints. The convoy owners paid a large fee, and promised ongoing payments for this service.[41]

At the same time defense minister Massoud was able to defeat Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and his allies militarily in the capital Kabul thwarting Pakistani ambitions. Massoud convened three nation-wide conferences to discuss the future of the country and a political process leading towards unification, consolidation and elections. Hekmatyar's failure to achieve what was expected of him prompted the Pakistani intelligence service ISI to turn towards a new surrogate force: the Taliban.[35] Over the next three months this hitherto unknown force took control of 12 of 34 provinces not under central government control, disarming the "heavily armed population". Militias controlling the different areas often surrendered without a fight.[25] The Taliban imposed on the parts of Afghanistan under their control their interpretation of Islam. The Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) analyze: "To PHR’s knowledge, no other regime in the world has methodically and violently forced half of its population into virtual house arrest, prohibiting them on pain of physical punishment".[28] Women were required to wear the all-covering chador, they were banned from public life and denied access to health care and education, windows needed to be covered so that women could not be seen from the outside, and they were not allowed to laugh in a manner they could be heard by others.[28] The Taliban, without any real court or hearing, cut people's hands or arms off when they were accused of stealing.[28] Taliban hit-squads watched the streets, conducting brutal public beatings.[28]

With the strong support of Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Osama Bin Laden[35][42][43] the Taliban proceeded further to Kabul (see video), where for the first time they faced the troops of defense minister Ahmad Shah Massoud, who then controlled large parts of the capital and provinces in the north and east of Afghanistan. Ahmad Shah Massoud had been named "The Afghan who won the cold war" by The Wall Street Journal.[44] He had defeated the Soviet Red Army nine times in his home region of Panjshir, in north-eastern Afghanistan.[45] Massoud, unarmed, went to talk to some Taliban leaders in Maidan Shar to convince them to join the initiated political process, so that democratic elections could be held to decide on a future government for Afghanistan. He hoped for them to be allies in bringing stability to Afghanistan before Afghans could choose their future government themselves. But the Taliban declined to join such a political process. When Massoud returned unharmed to Kabul, the Taliban leader who had received him as his guest paid with his life (he was killed by other senior Taliban) for failing to execute Massoud while the possibility had presented itself.

Over the following weeks, Massoud handed the Taliban their first major military defeat. Some months later, however, after Taliban forces had again encircled the capital, Massoud ordered a retreat from Kabul on September 26, 1996.[46] Massoud and his troops retreated to the northeast of Afghanistan.[47][48]

War against the United Front (Northern Alliance)

The Islamic State of Afghanistan (ISA), which had been created after the Soviet and Afghan Communist defeat, whose president was Burhanuddin Rabbani and whose defense minister was Ahmad Shah Massoud, from 1995 onwards came under attack by Mullah Omar's Taliban, Pakistan, and Al-Qaeda. In September 1996, the Taliban with their allies succeeded in taking power in Kabul.

Ahmad Shah Massoud, who still represented the legitimate government of Afghanistan as recognized by most foreign countries and the United Nations, and Abdul Rashid Dostum, one of his former archnemesis, for the survival of their remaining territories were forced to create an alliance against the Taliban, Pakistan (which had 28,000 Pakistani nationals fighting alongside the Taliban), and Al-Qaeda coalition which was about to attack the areas controlled by Massoud and Dostum.[49][50] The alliance was called the United Front, but in the Western and Pakistani media became known as the Northern Alliance.

As the Taliban committed massacres, especially among the Shia and Hazara population which they regarded as "sub-humans" worse than "non-believers" and thus according to them bereft of any rights,[43] many Hazaras fled to the area of Massoud. The Hezb-i Wahdat, the main faction of the Hazaras, consequently also joined the United Front. The National Geographic concluded: "The only thing standing in the way of future Taliban massacres is Ahmad Shah Massoud."[43] In the following years, many more were to join the United Front. These included Afghans and Afghan commanders from all regions and Afghan ethnicities, including many Pashtuns such as Commanders Abdul Haq, Haji Abdul Qadir, and Qari Baba, and diplomat and future Afghan president Hamid Karzai.

Closely tied with Pakistan's JUI party, the Taliban not only received help from regular Pakistani army troops and Bin Laden's 055 Brigade, but also manpower from madrasas in Pakistan’s border region. After a request from Mullah Omar in 1997, JUI's Maulana Samiul Haq shut down his 2,500+ student madrasah (Darul Uloom Haqqania), and "sent his entire student" body hundreds of miles to fight with the Taliban. The next year, he helped persuade 12 madrasas in Pakistan's North-West Frontier Province to shut down for one month and send 8,000 students to reinforce the Taliban.[51]

Meanwhile, in Pakistan followers of Mullah Omar were also imposing their interpretation of Islam. By 1998, some Pakistani groups along the "Pashtun belt" were banning TV and videos, imposing Sharia punishments "such as stoning and amputation in defiance of the legal system, killing Pakistani Shiʻa and forcing the people, particularly women, to adapt to the Taliban dress code and way of life."[52] In December 1998, the Tehrik-i-Tuleba (or Movement of Taliban) in the Orakzai Agency ignored Pakistan’s legal process, and publicly executed a murderer in front of 2,000 spectators. They also promised to implement Taliban-style justice and ban TV, music, and videos.[53] In Quetta, Pashtun pro-Taliban groups "burned down cinema houses, shot video shop owners, smashed satellite dishes, and drove women off the streets".[54] In Kashmir, Afghan Arabs attempted to impose a "Wahhabi-style dress code", banning jeans and jackets. "On February 15, 1999, they shot and wounded three Kashmiri cable television operators for relaying Western satellite broadcasts."[55]

In 1998 the forces of Rashid Dostum were defeated by the Taliban in Mazar-i-Sharif, and Dostum lost his territories. When the Taliban captured Mazar-i-Sharif on August 8, 1998, they killed thousands of civilians and several Iranian diplomats. Subsequently, Dostum went into exile. Meanwhile the Taliban in a major effort to also retake the Shomali plains, indiscriminately killed young men, while uprooting and expelling the population. Kamal Hossein, a special reporter for the UN, reported on these and other war crimes. Arab militants under Bin Laden were also responsible for some of the worst massacres in the war, killing hundreds of civilians in areas controlled by the United Front.[56]

The only leader to remain in Afghanistan, and who was able to defend vast parts of his area against the Taliban, was Ahmad Shah Massoud. Massoud also set up democratic institutions, including political, economic, health, and education committees. Massoud signed the Women's Rights Charta in the year 2000. In Massoud's area, women and girls did not have to wear the Afghan burqa. They were allowed to work, and to go to school. In at least two instances, Massoud personally intervened against cases of forced marriage.[57] While it was Massoud's stated conviction that men and women are equal and should enjoy the same rights, he also had to deal with Afghan traditions which he said would need a generation or more to overcome. In his opinion that could only be achieved through education.[57]

The Taliban repeatedly offered Massoud a position of power in return for him stopping his resistance. Massoud declined. He explained in one interview:

The Taliban say: "Come and accept the post of prime minister and be with us”, and they would keep the highest office in the country, the presidentship. But for what price?! The difference between us concerns mainly our way of thinking about the very principles of the society and the state. We cannot accept their conditions of compromise, or else we would have to give up the principles of modern democracy. We are fundamentally against the system called “the Emirate of Afghanistan”. I would like to return to the question of the emirate in a moment. In fact it is Pakistan that is responsible for deepening the crack between the ethnic groups in Afghanistan. It is again the old method of “divide and rule”. Pakistanis want to make sure that this country will not have any sovereign power for a long time."[58]

Massoud, instead, wanted to convince the Taliban to join a political process which would have ensured the holding of democratic elections in a foreseeable future.[58] His proposals for peace can be seen here: Proposal for Peace, promoted by Commander Massoud. American journalist Sebastian Junger, who frequently traveled to war zones, said in March 2001: "They [the Taliban] receive a tremendous amount of support by Pakistan.... without that involvement by Pakistan the Taliban would really be forced to negotiate".[44] Massoud stated in early 2001 that without the support of Pakistan the Taliban would not be able to sustain its military campaign for up to a year.[59]

The Taliban are not a force to be considered invincible. They are distanced from the people now. They are weaker than in the past. There is only the assistance given by Pakistan, Osama bin Laden, and other extremist groups that keep the Taliban on their feet. With a halt to that assistance, it is extremely difficult to survive."[60]

He also said: "There should be an Afghanistan where every Afghan finds himself or herself happy. And I think that can only be assured by democracy based on consensus."[60]

In early 2001 Massoud employed a new strategy of local military pressure and global political appeals.[61] His plans were for his allies to seed small revolts around Afghanistan, in the areas where the Afghans wanted to rise against the Taliban. Resentment was increasingly gathering against Taliban rule from the bottom of Afghan society, including in the Pashtun areas.[61] Massoud would publicize their cause "popular consensus, general elections and democracy" worldwide. Massoud was very wary not to revive the failed Kabul government of the early 1990s.[61] Instead, already in 1999, he started training police forces specifically in order to keep order and protect the civilian population in the event the United Front would be successful.[57]

In 2001, one million people had fled the Taliban, many to Massoud's areas where they sought protection from the commander. There was a huge humanitarian problem, because there was not enough food for both the pre-existing population and the refugees. In early 2001, Massoud and a French journalist described the bitter situation of the refugees, and asked for humanitarian help in front of the European Parliament in Brussels, Belgium.[62] see video Massoud went on to warn that his intelligence agents had gained limited knowledge about an imminent huge-scale terrorist attack on U.S. soil.[63] The president of the European Parliament, Nicole Fontaine, in 2001 called him the "pole of liberty in Afghanistan".[64]

Massoud, then aged 48, was the target of a suicide attack by two Arab extremists, who are believed to have strong connections to Ayman al-Zawahiri and Osama Bin Laden, at Khwaja Bahauddin, in Takhar Province in northeastern Afghanistan on September 9, 2001.[65][66] Massoud died in a helicopter as it was taking him to a hospital. The funeral, though in a rather rural area, was attended by hundreds of thousands of people.Sad day (video clip). The assassination was not the first time Al-Qaeda, the Taliban, the Pakistani ISI, and before them the Soviet KGB, the Afghan Communist KHAD and Hekmatyar had tried to assassinate Massoud. He survived countless assassination attempts over a period of 26 years. The first attempt on Massoud's life was carried out by Hekmatyar and two Pakistani ISI agents in 1975, when Massoud was only 22 years old.[37] In early 2001, Al-Qaeda would-be assassins were captured by Massoud's forces while trying to enter his territory.[61] The assassination of Massoud is considered to have a strong connection to the September 11, 2001 attacks on U.S. soil, which killed nearly 3.000 people, and which appeared to be the terrorist attack that Massoud had warned against in his speech to the European Parliament several months earlier.

John P. O'Neill was a counter-terrorism expert and the Assistant Director of the FBI until late 2001. He retired from the FBI and was offered the position of director of security at the World Trade Center (WTC). He took the job at the WTC two weeks before 9/11. On September 10, 2001, O’Neill told two of his friends, "We're due. And we're due for something big.... Some things have happened in Afghanistan. [referring to the assassination of Massoud] I don’t like the way things are lining up in Afghanistan.... I sense a shift, and I think things are going to happen ... soon."[67] O'Neill died on September 11, 2001, when the South Tower collapsed.[67]

For many days the United Front denied the death of Massoud, for fear of desperation amongst their people. The United Front managed to hold together, however. The slogan "Now we are all Massoudi" became a unifying battle cry. It was Massoudi's troops who ousted the Taliban from power in Kabul in 2001, with American air support, after the terrorist attack of September 11, 2001. The United Front also played a crucial role in establishing the post-Taliban interim government in late 2001.

Invasion, exile, and resurgence

Prelude

After the September 11 attacks on the U.S. and the PENTTBOM investigation, the United States made the following demands of the Taliban,[68] and refused to discuss them:

- Deliver to the U.S. all of the leaders of Al-Qaeda

- Release all foreign nationals that have been "unjustly imprisoned"

- Protect foreign journalists, diplomats, and aid workers

- Close immediately every terrorist training camp

- Hand over every terrorist and their supporters to appropriate authorities

- Give the United States full access to terrorist training camps for inspection

Over the course of the investigation, the U.S. petitioned the international community to back a military campaign to overthrow the Taliban. The United Nations Security Council and NATO approved the campaign as self-defense against armed attack.[69][70]

On September 21, the Taliban responded to the ultimatum, promising that if the U.S. could bring evidence that bin Laden was guilty, they would hand him over, stating that they had no evidence linking him to the September 11 attacks.[71]

On September 22, the United Arab Emirates, and later Saudi Arabia, withdrew recognition of the Taliban as Afghanistan's legal government, leaving neighbouring Pakistan as the only remaining country with diplomatic ties. On October 4, the Taliban agreed to turn bin Laden over to Pakistan for trial in an international tribunal[72] that operated according to Islamic Sharia law, but Pakistan blocked the offer as it was not possible to guarantee his safety.[73] On October 7, the Taliban ambassador to Pakistan offered to detain bin Laden and try him under Islamic law if the U.S. made a formal request and presented the Taliban with evidence. A Bush administration official, speaking on condition of anonymity, rejected the Taliban offer, and stated that the U.S. would not negotiate their demands.[74]

Coalition attack

Still on October 7, and less than one month after the Twin Towers fell, the U.S., aided by the United Kingdom, Canada, and other countries including several from the NATO alliance, initiated military action, bombing Taliban and Al-Qaeda-related camps.[75][76] The stated intent of military operations was to remove the Taliban from power, and prevent the use of Afghanistan as a terrorist base of operations.[77]

The CIA's elite Special Activities Division (SAD) units were the first U.S. forces to enter Afghanistan. They joined with the Afghan United Front (Northern Alliance) to prepare for the subsequent arrival of U.S. Special Operations forces. The United Front (Northern Alliance) and SAD and Special Forces combined to overthrow the Taliban with minimal coalition casualties, and without the use of international conventional ground forces. The Washington Post stated in an editorial by John Lehman in 2006:

What made the Afghan campaign a landmark in the U.S. Military's history is that it was prosecuted by Special Operations forces from all the services, along with Navy and Air Force tactical power, operations by the Afghan Northern Alliance and the CIA were equally important and fully integrated. No large Army or Marine force was employed.[78]

On October 14, the Taliban offered to discuss handing over Osama bin Laden to a neutral country in return for a bombing halt, but only if the Taliban were given evidence of bin Laden's involvement.[79] The U.S. rejected this offer, and continued military operations. Mazari Sharif fell November 9, triggering a cascade of provinces falling with minimal resistance. Many local forces switched loyalties from the Taliban to the Northern Alliance. On the night of November 12, the Taliban retreated south from Kabul. On November 15, they released eight Western aid workers after three months in captivity. By November 13, the Taliban had withdrawn from both Kabul and Jalalabad. Finally, in early December, the Taliban gave up Kandahar, their last stronghold, dispersing without surrendering.

Resurgence

Before the summer 2006 offensive began, indications existed that soldiers in Afghanistan had lost influence and power to other groups, including potentially the Taliban. [citation needed] A notable sign was rioting in May after a street accident in the city of Kabul.[80][81]

The continued support from tribal and other groups in Pakistan, the drug trade, and the small number of NATO forces, combined with the long history of resistance and isolation, indicated that Taliban forces and leaders were surviving. Suicide attacks and other terrorist methods not used in 2001 became more common. Observers suggested that poppy eradication, which destroys the livelihoods of rural Afghans, and civilian deaths caused by airstrikes encouraged the resurgence. These observers maintained that policy should focus on "hearts and minds" and on economic reconstruction, which could profit from switching from interdicting to diverting poppy production—to make medicine.[82][83]

In September 2006, Pakistan recognized the Islamic Emirate of Waziristan, an association of Waziristani chieftains with close ties to the Taliban, as the de facto security force for Waziristan. This recognition was part of the agreement to end the Waziristan War, which had exacted a heavy toll on the Pakistan Army since early 2004. Some commentators viewed Islamabad's shift from war to diplomacy as implicit recognition of the growing power of the resurgent Taliban relative to American influence, with the U.S. distracted by the threat of looming crises in Iraq, Lebanon, and Iran.[citation needed]

Other commentators viewed Islamabad's shift from war to diplomacy as an effort to appease growing discontent.[84] Because of the Taliban's leadership structure, Mullah Dadullah's targeted killing in May 2007 did not have a significant effect, other than to damage incipient relations with Pakistan.[85]

By 2009, a strong insurgency had emerged,[86][87] in the form of a guerrilla war. The Pashtun tribal group, with over 40 million members (including Afghanis and Pakistanis) had a long history of resistance to occupation forces, so the Taliban may have comprised only a part of the insurgency. Most post-invasion Taliban fighters were new recruits, mostly drawn from local madrasas.

In early December, the Taliban offered to give the U.S. "legal guarantees" that it would not allow Afghanistan to be used for attacks on other countries. The U.S. ignored the offer, and continued military action.[88]

U.S. targeted killings

The United States has used targeted killings, often by drones, to kill Taliban leaders. Among the more notable of the U.S.'s targeted killings of Taliban:

- In June 2004, the U.S. killed Nek Muhammad Wazir, a Taliban commander and al-Qaeda facilitator, along with five others, in an apparent Predator missile strike in South Waziristan, Pakistan.[89][90][91]

- In November 2008, Rashid Rauf, British/Pakistani suspected planner of a 2006 transatlantic aircraft plot, was killed by a missile launched from a U.S. drone on the well-guarded compound of a Taliban commander in North Waziristan, carried out by the CIA's Special Activities Division.[92][93]

- In August 2009, Baitullah Mehsud, the leader of the Taliban umbrella group, Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), which he formed from an alliance of about five pro-Taliban groups, who was thought to have commanded up to 5,000 fighters and to have been behind numerous attacks in Pakistan including the assassination of Benazir Bhutto, was killed (along with a Taliban lieutenant, seven bodyguards, his wife, and his mother- and father-in-law) in a U.S. CIA Special Activities Division drone missile attack on his father-in-law's house in South Waziristan, where he was staying.[94][95][96][97][98][99][100]

Ideology

| Part of a series on Islamism |

|---|

|

|

The Taliban initially enjoyed goodwill from Afghans weary of the warlords' corruption, brutality, and incessant fighting.[101] However, this popularity was not universal, particularly among non-Pashtuns.

The Taliban's extremely strict and anti-modern ideology has been described as an "innovative form of sharia combining Pashtun tribal codes,"[102] or Pashtunwali, with radical Deobandi interpretations of Islam favored by JUI and its splinter groups. Also contributing to the mix was the jihadism and pan-Islamism of Osama bin Laden.[103] Their ideology was a departure from the Islamism of the anti-Soviet mujahideen rulers they replaced who tended to be mystical Sufis, traditionalists, or radical Islamicists inspired by the Muslim Brotherhood (Ikhwan).[104]

Under the Taliban regime, Sharia law was interpreted to forbid a wide variety of previously lawful activities in Afghanistan. One Taliban list of prohibitions included:

pork, pig, pig oil, anything made from human hair, satellite dishes, cinematography, and equipment that produces the joy of music, pool tables, chess, masks, alcohol, tapes, computers, VCRs, television, anything that propagates sex and is full of music, wine, lobster, nail polish, firecrackers, statues, sewing catalogs, pictures, Christmas cards.[105]

They also prohibited employment, education, and sports for women, dancing, clapping during sports events, kite flying, and depictions of living things, whether drawings, paintings, photographs, stuffed animals, or dolls. Men were required to have a beard longer than a fist placed at the base of the chin. Conversely, they had to wear their head hair short. Men were also required to wear a head covering.[106]

Many of these activities were hitherto lawful in Afghanistan. Critics complained that most Afghans followed a different, less strict, and less intrusive interpretation of Islam. The Taliban did not eschew all traditional popular practices. For example, they did not destroy the graves of Sufi pirs (holy men), and emphasized dreams as a means of revelation.[107]

Punishment was severe. Theft was punished by the amputation of a hand, rape and murder by public execution, and married adulterers were stoned to death. In Kabul, punishments including executions were carried out in front of crowds in the city's soccer stadium.[108] Rules were issued by the Ministry for the Promotion of Virtue and Suppression of Vice (PVSV), and enforced by its "religious police", importing that Wahhabi concept.

Taliban have been described as both anti-nationalist and Pushtun nationalist. According to journalist Ahmed Rashid, at least in the first years of their rule, they adopted Deobandi and Islamist anti-nationalist beliefs, and opposed "tribal and feudal structures," eliminating traditional tribal or feudal leaders from leadership roles.[109] According to Ali A. Jalali and Lester Grau, the Taliban "received extensive support from Pashtuns across the country who thought that the movement might restore their national dominance. Even Pashtun intellectuals in the West, who differed with the Taliban on many issues, expressed support for the movement on purely ethnic grounds."[110]

Like Wahhabi and other Deobandis, the Taliban do not consider Shiʻi to be Muslims. The Taliban also declared the Hazara ethnic group, which totaled almost 10% of Afghanistan's population, "not Muslims."[111]

The Taliban were averse to debating doctrine with other Muslims. "The Taliban did not allow even Muslim reporters to question [their] edicts or to discuss interpretations of the Qur'an."[112]

Treatment of women

Women in particular were targets of the Taliban's restrictions. They were prohibited from working; wearing "stimulating and attractive" clothing; taking a taxi without the presence of a close male relative; washing clothes in streams; and having their measurements taken by tailors.[114]

Employment for women was restricted to the medical sector, because male medical personnel were not allowed to examine them. One result of the banning of employment of women by the Taliban was the closing down in places like Kabul of primary schools not only for girls but for boys, because almost all the teachers there were women.[115] Women were required to wear the burqa, a traditional dress covering the entire body except for a small screen to see out of. Taliban restrictions became more severe after they took control of the capital. In February 1998, religious police forced all women off the streets of Kabul, and issued new regulations ordering people to blacken their windows, so that women would not be visible from the outside.[116]

Explanation of ideology

Rashid suggests that the devastation and hardship of the Soviet invasion and the following civil war influenced Taliban ideology.[119] The madrasas' teachers were often "barely literate," and did not include scholars learned in Islamic law and history. The refugee students, brought up in a totally male society, not only had no education in mathematics, science, history or geography, but also had no traditional skills of farming, herding, or handicraft-making, nor even knowledge of their tribal and clan lineages.[119]

In such an environment, war meant employment, peace meant unemployment. Dominating women simply affirmed manhood. For their leadership, rigid fundamentalism was a matter not only of principle, but of political survival. Taliban leaders "repeatedly told" Rashid that "if they gave women greater freedom or a chance to go to school, they would lose the support of their rank and file."[120]

Criticisms

The Taliban were criticized for their strictness toward those who disobeyed the novel (Bid‘ah) rules. Some Muslims complained that many had no basis in the Qur'an or sharia.[121] Another objection was that the Taliban called their 20% tax on truckloads of opium "zakat", which is traditionally limited to 2.5% of the zakat-payers' disposable income (or wealth).[122]

Omar's title as Amir al-Mu'minin was criticized on the grounds that he lacked scholarly learning, tribal pedigree, or connections to the Prophet's family. Sanction for the title traditionally required the support of all of the country's ulema, whereas only some 1,200 Pashtun Taliban-supporting Mullahs had declared Omar the Amir. "No Afghan had adopted the title since 1834, when King Dost Mohammed Khan assumed the title before he declared jihad against the Sikh kingdom in Peshawar. But Dost Mohammed was fighting foreigners, while Omar had declared jihad against other Afghans."[122]

The Taliban have also been accused of being hypocritical, as intelligence picked up by Predator drones and other battlefield cameras is at odds with the notion that they are pious warriors of God. Thermal-imagery technology housed in a sniper rifle showed two Talibs in southern Afghanistan engaged in intimate relations with a donkey, and ground-surveillance footage recorded a Talib fighter gratifying himself with a cow.[123]

Governance

Rashid described the Taliban government as "a secret society run by Kandaharis ... mysterious, secretive, and dictatorial."[124] They did not hold elections, as their spokesman explained:

The Sharia does not allow politics or political parties. That is why we give no salaries to officials or soldiers, just food, clothes, shoes, and weapons. We want to live a life like the Prophet lived 1400 years ago, and jihad is our right. We want to recreate the time of the Prophet, and we are only carrying out what the Afghan people have wanted for the past 14 years.[125]

They modeled their decision-making process on the Pashtun tribal council (jirga), together with what they believed to be the early Islamic model. Discussion was followed by a building of a consensus by the "believers".[126] Before capturing Kabul, there was talk of stepping aside once a government of "good Muslims" took power, and law and order were restored.

As the Taliban's power grew, decisions were made by Mullah Omar without consulting the jirga and without consulting other parts of the country. He visited the capital, Kabul, only twice while in power. Instead of an election, their leader's legitimacy came from an oath of allegiance ("Bay'ah"), in imitation of the Prophet and the first four Caliphs. On April 4, 1996, Mullah Omar had "the Cloak of the Prophet Mohammed" taken from its shrine for the first time in 60 years. Wrapping himself in the relic, he appeared on the roof of a building in the center of Kandahar while hundreds of Pashtun mullahs below shouted "Amir al-Mu'minin!" (Commander of the Faithful), in a pledge of support. Taliban spokesman Mullah Wakil explained:

Decisions are based on the advice of the Amir-ul Momineen. For us consultation is not necessary. We believe that this is in line with the Sharia. We abide by the Amir's view even if he alone takes this view. There will not be a head of state. Instead there will be an Amir al-Mu'minin. Mullah Omar will be the highest authority, and the government will not be able to implement any decision to which he does not agree. General elections are incompatible with Sharia and therefore we reject them.[127]

The Taliban were very reluctant to share power, and since their ranks were overwhelmingly Pashtun they ruled as overlords the 60% of Afghanis from other ethnic groups. In local government, such as Kabul city council[124] or Herat,[128] Taliban loyalists, not locals, dominated, even when the Pashto-speaking Taliban could not communicate with the roughly half of the population who spoke Dari or other non-Pashtun tongues.[128] Critics complained that this "lack of local representation in urban administration made the Taliban appear as an occupying force."[129]

Organization

Consistent with the governance of early Muslims was the absence of state institutions or "a methodology for command and control" that is standard today even among non-Westernized states. The Taliban did not issue press releases, policy statements, or hold regular press conferences. The outside world and most Afghans did not even know what their leaders looked like, since photography was banned.[130] The "regular army" resembled a lashkar or traditional tribal militia force with only 25,000 to 30,000 men, expanding as the need arose.

Cabinet ministers and deputies were mullahs with a "madrasah education." Several of them, such as the Minister of Health and Governor of the State bank, were primarily military commanders who left their administrative posts to fight when needed. Military reverses that trapped them behind lines or led to their deaths increased the chaos in the national administration.[131] At the national level, "all senior Tajik, Uzbek and Hazara bureaucrats" were replaced "with Pashtuns, whether qualified or not." Consequently, the ministries "by and large ceased to function."[129]

The Ministry of Finance had neither a budget nor "qualified economist or banker." Mullah Omar collected and dispersed cash without book-keeping.

Conscription

According to the testimony of Guantanamo captives before their Combatant Status Review Tribunals, the Taliban, in addition to conscripting men to serve as soldiers, also conscripted men to staff its civil service.[citation needed]

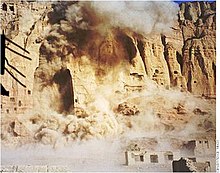

Bamyan Buddhas

In 1999, Omar issued a decree protecting the Buddha statues at Bamyan, two 6th century monumental statues of standing buddhas carved into the side of a cliff in the Bamyan valley in the Hazarajat region of central Afghanistan, because Afghanistan had no Buddhists, implying idolatry would not be a problem. But in March 2001 the statues were destroyed by the Taliban following a decree stating, "all the statues around Afghanistan must be destroyed."[132]

Economy

Peace did not bring economic development. The so-called "transportation mafia" operating out of Pakistan "cut down millions of acres of timber in Afghanistan for the Pakistani market, denuding the countryside without attempting reforestation. They stripped rusting factories, ... even electricity and telephone poles for their steel and sold the scrap to steel mills in Lahore."[133]

Business dealings

In 1997, the Taliban and Unocal negotiated arrangements for CentGas to build a gas pipeline from Turkmenistan to Pakistan.[134] Reportedly, a deal was struck but later collapsed,[135] rumored to be because of competing negotiations with Bridas, an Argentine company.[136]

Swat's emerald mines

The Taliban took over emerald mines in Pakistan's Swat valley (not a tribal area), once the 'Switzerland of Pakistan', a popular tourist area for skiers. The government did not react to the move. The Taliban reached an agreement with the region's mining labor allowing the Taliban to keep one-third of the miners' output, while equally sharing costs. The Taliban does not take part in the mining operations.[137]

Opium

Opium poppies are a traditional crop in Afghanistan, and, with the war shattering other sectors of the economy, opium became its largest export.

The Taliban have provided an Islamic sanction for farmers ... to grow even more opium, even though the Koran forbids Muslims from producing or imbibing intoxicants. Abdul Rashid, the head of the Taliban's anti-drugs control force in Kandahar, spelled out the nature of his unique job. He is authorized to impose a strict ban on the growing of hashish, "because it is consumed by Afghans and Muslims." But, Rashid told me without a hint of sarcasm, "Opium is permissible because it is consumed by kafirs in the West, and not by Muslims or Afghans."[138]

In 2000, the Taliban banned opium production, a first[citation needed] in Afghan history. That year Afghanistan's opium production still accounted for 75% of the world's supply. On July 27, 2000, the Taliban again issued a decree banning cultivation.[139] By February 2001, production had been reduced from 12,600 acres (51 km2) to only 17 acres (7 ha).[140] When the Taliban entered North Waziristan in 2003 they immediately banned cultivation and punished those who sold it.[citation needed]

Another source claimed opium production was cut back by the Taliban not to prevent its use, but to increase its price, and thus increase the income of Afghan poppy farmers and tax revenue.[141]

The Taliban's top drug official in Nangarhar, Mullah Amir Mohammed Haqqani, said the ban would remain regardless of whether the Taliban received aid or international recognition. "It is our decree that there will be no poppy cultivation. It is banned forever in this country," he said. "Whether we get assistance or not, poppy growing will never be allowed again in our country."[140]

However, with the 2001 expulsion of the Taliban, opium cultivation returned,[142] and by 2005 Afghanistan provided 87% of the world supply,[143] rising to 90% in 2006.[144]

In October 2009 a report, citing "American and Afghan officials", appeared in The New York Times stating that the Taliban were supporting the opium trade and deriving funding from it, counter to their documented prior banning and elimination of the drug trade in Afghanistan.[145]

International relations

During its time in power, the Taliban regime, or "Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan", gained diplomatic recognition from only three states: the United Arab Emirates, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia, all of which provided substantial aid. The other nations including the United Nations recognized the government of the Islamic State of Afghanistan (parts of whom were part of the United Front (Northern Alliance) as the legitimate government of Afghanistan.

Pakistan

The "vast majority" of the Taliban's rank and file and most of the leadership, though not Mullah Omar, were Koranic students who had studied at madrasas set up for Afghan refugees, usually by JUI. Maulana Fazal-ur-Rehman, JUI's leader, was a political ally of Benazir Bhutto. After Bhutto became prime minister, Rehman "had access to the government, the army and the ISI," whom he influenced to help the Taliban.[146]

Pakistan's ISI supported the previously unknown Kandahari student movement,[147] the Taliban, as the group conquered Afghanistan in the 1990s.[148]

From 1994 onwards Pakistan has been the force behind the Taliban. Former Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf - then as Chief of Army Staff - was responsible for sending thousands of Pakistanis, including the Frontier Corps, to fight alongside the Taliban and Bin Laden against the United Front (Northern Alliance).[149][43][57][150] A 1998 document by the U.S. State Department provided by the George Washington University states: "[A]n estimated 20-40 percent of Taliban soldiers are Pakistani ..."[151] It further states that the parents of those Pakistani soldiers "know nothing regarding their child's military involvement with the Taliban until their bodies are brought back to Pakistan."[152] In total there were believed to be 28 000 Pakistani nationals fighting alongside the Taliban.[57] Human Rights Watch writes: "Pakistani aircraft assisted with troop rotations of Taliban forces during combat operations in late 2000 and ... senior members of Pakistan's intelligence agency and army were involved in planning military operations."[153]

Pakistan further provided military equipment, recruiting assistance, training, and tactical advice that enabled the band of village mullahs and their adherents to control the country.[154] Officially Pakistan denied supporting the group. But its 1998 aid was an estimated US$30 million in wheat, diesel, petroleum and kerosene fuel, and other supplies, amounting to approximately $1 per capita.[155][156] Conversely, the Taliban's "unprecedented access" among Pakistan's lobbies and interest groups enabled it to "play off one lobby against another and extend their influence in Pakistan even further. At times they would defy" even the powerful ISI.[157]

From 2010, a report by a leading British institution claimed that Pakistan's intelligence service still today has a strong link with the Taliban in Afghanistan. Published by the London School of Economics, the report said that Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence agency (ISI) has an "official policy" of support for the Taliban. It said the ISI provides funding and training for the Taliban, and that the agency has representatives on the so-called Quetta Shura, the Taliban's leadership council, which is believed to meet in Pakistan. The report, based on interviews with Taliban commanders in Afghanistan, was written by Matt Waldman, a fellow at Harvard University.[158]

U.S. officials have long suspected a link between the ISI and the Taliban, but those suspicions are rarely confirmed. "Pakistan appears to be playing a double-game of astonishing magnitude," the report said. The report also linked high-level members of the Pakistani government with the Taliban. It said Asif Ali Zardari, the Pakistani president, met with senior Taliban prisoners in 2010 and promised to release them. Zardari reportedly told the detainees they were only arrested because of American pressure. "The Pakistan government's apparent duplicity – and awareness of it among the American public and political establishment – could have enormous geopolitical implications," Waldman said. "Without a change in Pakistani behaviour it will be difficult if not impossible for international forces and the Afghan government to make progress against the insurgency." Afghan officials have long been suspicious of the ISI's role.

Amrullah Saleh, the former director of Afghanistan's intelligence service, told Reuters that the ISI was "part of a landscape of destruction in this country".[159]

Taliban presence

The Taliban created a new form of Islamic radicalism that spread beyond the borders of Afghanistan, mostly to Pakistan. By 1998–99, Taliban-style groups in the Pashtun belt, and to an extent in Pakistan-administered Kashmir, "were banning TV and videos ... and forcing people, particularly women, to adapt to the Taliban dress code and way of life."[160]

As of early 2007, Taliban influence in Pakistan continued in conjunction with the Taliban insurgency. Citing a restaurant suicide bombing in Peshawar in retaliation for the arrest of a relative of Mullah Dadullah, the Associated Press stated "in Pakistan's frontier regions, ... scores of people have been executed over the past two or three years, apparently for being too aligned with the Pakistani government or American—allies in the U.S.-led war on terrorism."[161]

The formation of a Pakistan Taliban umbrella group called Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan was announced in December 2007.[162]

On February 8, 2009, U.S. commander of operations in Afghanistan General Stanley McChrystal and other officials said that the Taliban leadership was in Quetta, though the Pakistan government denied this.[16][17] However the U.S. praised Pakistan military effort against the Taliban.[163] Furthermore the White House hailed the capture of Taliban No.2 leader Abdul Ghani Baradar in Pakistan, claiming a "big success for our mutual efforts (Pakistan and U.S.) in the region".[164]

On February 16, 2009, Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari signed a deal with the Taliban to implement Shariah law in some parts of Pakistan, including banning girls from school.[165][166] On April 13, 2009, Zardari signed into law a peace deal for the Swat Valley, including sharia.[167]

On June 30, 2009, the Taliban withdrew from the peace deal to protest the continuing airstrikes by American drones. Soon after the announcement, approximately 150 militants attacked a Pakistani military convoy near Miramshah, killing an estimated 30 soldiers. An additional 4 were killed in southwestern Pakistan by a car bomber, who targeted NATO supply trucks.[168]

Guerrilla attacks will be launched against the Pakistani military unless drone attacks are stopped and government troops are pulled out of North Waziristan. We will attack forces everywhere in Waziristan unless the government fulfills these two demands.

— Ahmadullah Ahmadi, spokesperson for Pakistani Taliban[169]

The Pakistani government was also concerned that the attacks could indicate preparation for a full-on assault.[170] The government's plan to transport supplies through that region were complicated by the danger of guerilla attacks.[171] The government remained vulnerable to attacks on multiple fronts, and the North Waziristan faction of the Taliban gave no indication of accepting a compromise.[172] Pakistani leaders were concerned that Bahadur was not the only one planning to carry out attacks.[172]

United Kingdom

After 9/11, the United Kingdom froze the Taliban's asset's in the U.K., nearly $200 million by early October 2001.[173] The U.K. also supported the U.S. decision to remove the Taliban, both politically and militarily.[174]

The UN agreed that NATO would act on its behalf, focusing on counter-terrorist operations in Afghanistan after the Taliban had been "defeated". The United Kingdom took operational responsibility for Helmand Province, a major poppy-growing province in southern Afghanistan, deploying troops there in the summer of 2006, and encountered resistance by re-formed Taliban forces entering Afghanistan from Pakistan. The Taliban turned towards the use of improvised explosive devices.[175]

In 2008, the U.K. announced plans to pay Taliban fighters to switch sides or lay down arms;[176] later, in 2009 the United Kingdom government backed talks with the Taliban.[177]

United States

Foreign powers, including the United States, briefly supported the Taliban, hoping it would restore order in the war-ravaged country. For example, it made no comment when the Taliban captured Herat in 1995, and expelled thousands of girls from schools.[178] These hopes faded as the Taliban began killing unarmed civilians, targeting ethnic groups (primarily Hazaras), and restricting the rights of women.[102] In late 1997, American Secretary of State Madeleine Albright began to distance the U.S. from the Taliban. The next year, the American-based oil company Unocal withdrew from negotiations on pipeline construction from Central Asia.[179]

One day before the capture of Mazar, bin Laden affiliates bombed two U.S. embassies in Africa, killing 224 and wounding 4,500, mostly Africans. The U.S. responded by launching cruise missiles on suspected terrorist camps in Afghanistan, killing over 20 though failing to kill bin Laden or even many Al-Qaeda. Mullah Omar condemned the missile attack and American President Bill Clinton.[180] Saudi Arabia expelled the Taliban envoy in protest over the refusal to turn over bin Laden, and after Mullah Omar allegedly insulted the Saudi royal family.[181] In mid-October the U.N. Security Council voted unanimously to ban commercial aircraft flights to and from Afghanistan, and freeze its bank accounts worldwide.[182]

Adjusting its counterinsurgency strategy, in October 2009, the U.S announced plans to pay Taliban fighters to switch sides.[183]

On November 26, 2009, in an interview with CNN's Christiane Amanpour, President Hamid Karzai said there is an "urgent need" for negotiations with the Taliban, and made it clear that the Obama administration had opposed such talks. There was no formal American response.[184][185]

In early December 2009, the Taliban offered to give the U.S. "legal guarantees" that they would not allow Afghanistan to be used for attacks on other countries. There was no formal American response.[88]

On December 6, U.S officials indicated that they have not ruled out talks with the Taliban.[186] Several days later it was reported that Gates saw potential for reconciliation with the Taliban, but not with Al-Qaeda. Furthermore, he said that reconciliation would politically end the insurgency and the war. But he said reconciliation must be on the Afghan government's terms, and that the Taliban must be subject to the sovereignty of the government.[187]

In 2010, General McChrystal said his troop surge could lead to a negotiated peace with the Taliban.[188]

Allegations of connection to United States CIA

There have been many claims that the CIA directly supported the Taliban or Al-Qaeda. In the early 1980s, the CIA and the ISI (Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence agency) provided arms and money, and the ISI helped gather radical Muslims from around the world to fight against the Soviet invaders.[189] Osama Bin Laden was one of the key players in organizing training camps for the foreign Muslim volunteers. "By 1987, 65,000 tons of U.S.-made weapons and ammunition a year were entering the war."[190] FBI translator Sibel Edmonds, who was fired from the CIA for disclosing sensitive information, claims that the U.S. was on intimate terms with the Taliban and Al-Qaeda, using them to further U.S. goals in Central Asia.[191] Republican Congressman Dana Rohrabacher was quoted as saying, "The Taliban was a construct of the CIA and was armed by the CIA... The Clinton administration, along with Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, created the Taliban." [192]

India

India is one of the Taliban's most outspoken critics. India was concerned about growing Islamic militancy in its neighborhood, and refused to recognize the Taliban regime.[193] Ahmad Shah Massoud also had close ties to India.[194]

In December 1999, Indian Airlines Flight 814 en route from Kathmandu to Delhi was hijacked and taken to Kandahar. The Taliban moved its militias near the hijacked aircraft, supposedly to prevent Indian special forces from storming the aircraft, and stalled the negotiations between India and the hijackers for days. The New York Times later reported that there were credible links between the hijackers and the Taliban.[195] As a part of the deal to free the plane, India released three militants. The Taliban gave a safe passage to the hijackers and the released militants.[196]

Following the hijacking, India drastically increased its efforts to help Massoud, providing an arms depot in Dushanbe, Tajikistan.[197] India also provided a wide range of high-altitude warfare equipment, helicopter technicians, medical services, and tactical advice.[198] According to one report, Indian military support to anti-Taliban forces totaled US$70 million, including five Mi-17 helicopters, and US$8 million worth of high-altitude equipment in 2001.[199] India extensively supported the new administration in Afghanistan,[200] leading several reconstruction projects[201] and by 2001 had emerged as the country's largest regional donor.[202]

Iran

In early August 1998, relations with other countries became much more troubled. After attacking the city of Mazar, Taliban forces killed several thousand civilians and 10 Iranian diplomats and intelligence officers in the Iranian consulate. Alleged radio intercepts indicate Mullah Omar personally approved the killings.[203] The Iranian government was incensed, and crisis ensued as Iran mobilized 200,000 regular troops,[204] though war was eventually averted.

Palestine

The Pakistani Taliban claimed responsibility for a September 3, 2010, deadly suicide bomber attack against a pro-Palestine rally in Pakistan.[205]

United Nations and aid agencies

A major issue during the Taliban's reign was its relations with the United Nations (UN) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Twenty years of continuous warfare had devastated Afghanistan's infrastructure and economy. There was no running water, little electricity, few telephones, functioning roads or regular energy supplies. Basic necessities like water, food, housing and others were in desperately short supply. In addition, the clan and family structure that provided Afghans with a social/economic safety net was also badly damaged.[112][206] Afghanistan's infant mortality was the highest in the world. A full quarter of all children died before they reached their fifth birthday, a rate several times higher than most other developing countries.[207]

International charitable and/or development organisations (NGOs) were extremely important to the supply of food, employment, reconstruction, and other services. With one million plus deaths during the years of war, the number of families headed by widows had reached 98,000 by 1998.[208] Thus Taliban restrictions on women were sometime a matter not only of human rights, but of life and death. In Kabul, where vast portions of the city had been devastated from rocket attacks, more than half of its 1.2 million people benefited in some way from NGO activities, even for water to drink.[209] The civil war and its never-ending refugee stream continued throughout the Taliban's reign. The Mazar, Herat, and Shomali valley offensives displaced more than three-quarters of a million civilians, using "scorched earth" tactics to prevent them from supplying the enemy with aid.[210]

Despite the aid, the Taliban's attitude toward the UN and NGOs was often one of suspicion, in place of gratitude or even tolerance. The UN operates on the basis of international law, not Sharia, and the UN did not recognize the Taliban as the legitimate government of Afghanistan. Additionally, most foreign donors and aid workers, were non-Muslims. As the Taliban's Attorney General Maulvi Jalil-ullah Maulvizada put it:

Let us state what sort of education the UN wants. This is a big infidel policy which gives such obscene freedom to women which would lead to adultery and herald the destruction of Islam. In any Islamic country where adultery becomes common, that country is destroyed and enters the domination of the infidels because their men become like women and women cannot defend themselves. Anyone who talks to us should do so within Islam's framework. The Holy Koran cannot adjust itself to other people's requirements, people should adjust themselves to the requirements of the Holy Koran.[211]

Taliban decision-makers, particularly Mullah Omar, seldom if ever talked directly to non-Muslim foreigners, so aid providers had to deal with intermediaries whose approvals and agreements were often reversed.[129] Around September 1997 the heads of three UN agencies in Kandahar were expelled from the country after protesting when a female attorney for the UN High Commissioner for Refugees was forced to talk from behind a curtain so her face would not be visible.[212]

When the UN increased the number of Muslim women staff to satisfy Taliban demands, the Taliban then required all female Muslim UN staff traveling to Afghanistan to be chaperoned by a mahram or a blood relative.[213] In July 1998, the Taliban closed "all NGO offices" by force after those organizations refused to move to a bombed-out former Polytechnic College as ordered.[214] One month later the UN offices were also shut down.[215] As food prices rose and conditions deteriorated, Planning Minister Qari Din Mohammed explained the Taliban's indifference to the loss of humanitarian aid:

We Muslims believe God the Almighty will feed everybody one way or another. If the foreign NGOs leave then it is their decision. We have not expelled them.[216]

In 2009 a top U.N official called for talks with Taliban leaders.[217] In 2010 the U.N lifted sanctions on the Taliban,[218] and requested that Taliban leaders and others be removed from terrorism watch lists.[219] In 2010 the U.S. and Europe announced support for President Karzai's latest attempt to negotiate peace with the Taliban.[220]

Osama bin Laden

In 1996, bin Laden moved to Afghanistan from Sudan. He came without invitation, and sometimes irritated Mullah Omar with his declaration of war and fatwas against citizens of third-party countries,[221] but relations between the two groups improved over time, to the point that Mullah Omar rebuffed his group's patron Saudi Arabia, insulting Saudi minister Prince Turki while reneging on an earlier promise to turn bin Laden over to the Saudis.[222]

Bin Laden was able to forge an alliance between the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. The Al Qaeda-trained 055 Brigade integrated with the Taliban army between 1997 and 2001. Several hundred Arab Afghan fighters sent by bin Laden assisted the Taliban in the Mazar-e-Sharif slaughter.[223] The so-called Brigade 055 was also responsible for massacres against civilians in other parts of Afghanistan.[56] From 1996 to 2001 the organization of Osama Bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri had become a virtual state within the Taliban state.

Taliban-Al-Qaeda connections were also strengthened by the reported marriage of one of bin Laden's sons to Omar's daughter. While in Afghanistan, bin Laden may have helped finance the Taliban.[224][225]

After the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings in Africa, bin Laden and several Al-Qaeda members were indicted in U.S. criminal court.[226] The Taliban rejected extradition requests by the U.S., variously claiming that bin Laden had "gone missing",[227] or that Washington "cannot provide any evidence or any proof" that bin Laden is involved in terrorist activities and that "without any evidence, bin Laden is a man without sin... he is a free man."[71][228]

Evidence against bin Laden included courtroom testimony and satellite phone records.[229][230] Bin Laden in turn, praised the Taliban as the "only Islamic government" in existence, and lauded Mullah Omar for his destruction of idols such as the Buddhas of Bamyan.[231]

At the end of 2008, the Taliban was in talks to sever all ties with Al-Qaeda.[232]

Human rights violations

According to Human Rights Watch, the Taliban's bombings and other attacks which have led to civilian casualties "sharply escalated in 2006" when "at least 669 Afghan civilians were killed in at least 350 armed attacks, most of which appear to have been intentionally launched at non-combatants."[233][234] By 2008, the Taliban had increased its use of suicide bombers and targeted unarmed civilian aid workers, such as Gayle Williams.[235]

The United Nations reported that the number of civilians killed by both the Taliban and pro-government forces in the war rose nearly 50% between 2007 and 2009. In the first half of 2008, the Taliban killed 495 civilians, and the allies 276. In the first six months of 2009 the Taliban killed 595 civilians, and NATO and Afghan government forces killed 309.[236][237] The high number of civilians killed by the Taliban is blamed in part on their increasing use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), "for instance, 16 IEDs have been planted in girls' schools" by the Taliban.[236]

Criticism of tactics and strategy

In 2009, Colonel Richard Kemp, formerly Commander of British forces in Afghanistan and the intelligence coordinator for the British government, drew parallels between the tactics and strategy of Hamas in Gaza to those of the Taliban. Kemp wrote:

Like Hamas in Gaza, the Taliban in southern Afghanistan are masters at shielding themselves behind the civilian population and then melting in among them for protection. Women and children are trained and equipped to fight, collect intelligence, and ferry arms and ammunition between battles. Female suicide bombers are increasingly common. The use of women to shield gunmen as they engage NATO forces is now so normal it is deemed barely worthy of comment. Schools and houses are routinely booby-trapped. Snipers shelter in houses deliberately filled with women and children.[238][239]

See also

{{{inline}}}

- Al-Qaeda

- Taliban treatment of women

- Talibanization

- Colonel Imam

- Inter-Services Intelligence

- Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan

- Deobandi

- Pashtun people

- History of Afghanistan since 1992

- Northern Alliance

- Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs

- Opium production in Afghanistan

- Quetta Shura

- Special Activities Division

- Targeted killing

- Taliban propaganda

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

- US Army Special Forces

Notes

- ^ Pajhwok Afghan News, Taliban have opened office in Waziristan (Pakistan)[dead link].

- ^ "Taliban and the Northern Alliance". Usgovinfo.about.com. Retrieved November 26, 2009.

- ^ 9/11 seven years later: U.S. 'safe,' South Asia in turmoil "There are now some 62,000 foreign soldiers in Afghanistan, including 34,000 U.S. troops, and some 150,000 Afghan security forces. They face an estimated 7,000 to 11,000 insurgents, according to U.S. commanders."'.' Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ "MajorGeneral Richard Barrons puts Taleban fighter numbers at 36000". The Times. London. March 3, 2010.

- ^ "Analysis: Who are the Taleban?". BBC News. December 20, 2000.

- ^ ISAF has participating forces from 39 countries, including all 26 NATO members. See ISAF Troop Contribution Placement, 2007-12-05[dead link].

- ^ "Pakistan and the Taliban: It's Complicated". ShaveMagazine.com.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Wiping out Uzbek, Tajik & Foreign terrorists in FATA". Zimbio.com. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ "Terrorist camp may hold clues to Taliban operations". Dailytimes.com.pk. June 24, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ Suicide car bomb kills 24 in northwest Pakistan[dead link]

- ^ "Pakistan and Taliban, Brothers or Rivals?". Theworldreporter.com. September 14, 2010.

- ^ Sep 22, 2009 (September 22, 2009). "U.S. says Pakistan Iran helping Taliban". Axisofjustice.org. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Iran helping the Taliban, US ambassador claims". Iranfocus.com. December 18, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ "Iran accused of assisting Afghan Taliban". Pajhwok.com. Retrieved August 27, 2010. [dead link]

- ^ McElroy, Damien (December 17, 2009). "Iran helping the Taliban, US ambassador claims". London: Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ a b Schmitt, Eric (February 9, 2009). "Taliban Haven in Pakistani City Raises Fears". New York Times.

- ^ a b Schmitt, Eric (September 24, 2009). "Taliban Widen Afghan Attacks From Base in Pakistan". New York Times.

- ^ "No word from Islamabad on Omar's arrest". Pajhwok.com. Retrieved August 27, 2010. [dead link]

- ^ "From the article on the Taliban in Oxford Islamic Studies Online". Oxfordislamicstudies.com. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ Goodson 2001, p. 114.

- ^ Rashid 2000, pp. 17–30.

- ^ Rashid 2000, pp. 26, 29.

- ^ Mazzetti, Mark; Schmitt, Eric (August 6, 2009). "C.I.A. Missile Strike May Have Killed Pakistan's Taliban Leader, Officials Say". New York Times. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- ^ "Pakistan offensive: troops meet heavy Taliban resistance". The Daily Telegraph. London. October 17, 2009. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Rashid 2000, p. 29

- ^ a b Dupree Hatch, Nancy. "Afghan Women under the Taliban" in Maley, William. Fundamentalism Reborn? Afghanistan and the Taliban. London: Hurst and Company, 2001, pp. 145–166.

- ^ M. J. Gohari (2000). The Taliban: Ascent to Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 108–110.

- ^ a b c d e Template:PDFlink, Physicians for Human Rights, August 1998.

- ^ Kilcullen, David (2009). The Accidental Guerrilla: Fighting Small Wars in the Midst of a Big One. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195368345.

- ^ English <-> Arabic Online Dictionary.

- ^ From 'Taleban' to 'Taliban' BBC – The Editors.

- ^ “”. "Robert Fisk – The Age of the Warrior". YouTube. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "Blood-Stained Hands, Past Atrocities in Kabul and Afghanistan's Legacy of Impunity". Human Rights Watch.

- ^ Neamatollah Nojumi. The Rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan: Mass Mobilization, Civil War, and the Future of the Region (2002 1st ed.). Palgrave, New York.

- ^ a b c d e f Amin Saikal. Modern Afghanistan: A History of Struggle and Survival (2006 1st ed.). I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd., London New York. p. 352. ISBN 1-85043-437-9.

- ^ "The September 11 Sourcebooks Volume VII: The Taliban File". gwu.edu. 2003.

- ^ a b GUTMAN, Roy (2008): How We Missed the Story: Osama Bin Laden, the Taliban and the Hijacking of Afghanistan, Endowment of the United States Institute of Peace, 1st ed., Washington D.C.

- ^ Rashid 2000, p. 25

- ^ Matinuddin, Kamal, The Taliban Phenomenon, Afghanistan 1994–1997, Oxford University Press, (1999), pp.25–6

- ^ Rashid 2000, pp. 27–29.

- ^ The Taliban Infoplease.com.

- ^ "Inside the Taliban". National Geographic. 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Inside the Taliban". National Geographic. 2007. Cite error: The named reference "National Geographic" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b "[[Charlie Rose]], March 26, 2001". CBS. 2001.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "He would have found Bin Laden". CNN. May 27, 2009.

- ^ Coll, Ghost Wars (New York: Penguin, 2005), 14.

- ^ Bearak, Barry (November 9, 1999). "Afghan 'Lion' Fights Taliban With Rifle and Fax Machine". Afghanistan: Ny times. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ Burns, John F. (October 8, 1996). "Afghan Driven From Kabul Makes Stand in North". Gulbahar (Afghanistan); Afghanistan: Ny times. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ "Massoud's Last Stand". Journeyman Pictures/ABC Australia. 1997.

- ^ “”. "''see'' video". Youtube.com. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rashid 2000, p. 91.

- ^ Rashid 2000, p. 93

- ^ Yousufzai, Rahimyllah, "Pakistani Taliban at work," The News, 1998-12-18. See also AFP, "Murder convict executed Taliban style in Pakistan", 1998-12-14.

- ^ Rashid 2000, p. 194.

- ^ Agence France Presse, "Kashmir militant group issues Islamic dress order," 1999-02-21.

- ^ a b "Afghanistan resistance leader feared dead in blast". London: Ahmed Rashid in the Telegraph. September 11, 2001. Cite error: The named reference "Ahmed Rashid/The Telegraph" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e Marcela Grad. Massoud: An Intimate Portrait of the Legendary Afghan Leader (March 1, 2009 ed.). Webster University Press. p. 310.