Timeline of modern American conservatism: Difference between revisions

m Dating maintenance tags: {{Lopsided}} |

→1990s: add cites |

||

| Line 174: | Line 174: | ||

*October 15: [[Clarence Thomas]], a [[Black conservatism in the United States|black Republican]], is confirmed as a Justice of the Supreme Court after extremely controversial hearings that focus less on his strongly conservative beliefs than his relationships with one of his aides, Anita Hill, who accuses him of sexual harassment.<ref>Dan Thomas, Craig McCoy and Allan McBride, "Deconstructing the Political Spectacle: Sex, Race, and Subjectivity in Public Response to the Clarence Thomas/Anita Hill "Sexual Harassment" Hearings," ''American Journal of Political Science'' Vol. 37, No. 3 (Aug., 1993), pp. 699-720 [http://www.jstor.org/stable/2111571 in JSTOR]</ref> |

*October 15: [[Clarence Thomas]], a [[Black conservatism in the United States|black Republican]], is confirmed as a Justice of the Supreme Court after extremely controversial hearings that focus less on his strongly conservative beliefs than his relationships with one of his aides, Anita Hill, who accuses him of sexual harassment.<ref>Dan Thomas, Craig McCoy and Allan McBride, "Deconstructing the Political Spectacle: Sex, Race, and Subjectivity in Public Response to the Clarence Thomas/Anita Hill "Sexual Harassment" Hearings," ''American Journal of Political Science'' Vol. 37, No. 3 (Aug., 1993), pp. 699-720 [http://www.jstor.org/stable/2111571 in JSTOR]</ref> |

||

;1992 |

;1992 |

||

*November 3: George H. W. Bush is defeated by [[Bill Clinton]] in the [[United States presidential election, 1992|presidential election]]. Bush had alienated much of his conservative base |

*November 3: George H. W. Bush is defeated by [[Bill Clinton]] in the [[United States presidential election, 1992|presidential election]]. Bush had alienated much of his conservative base by breaking his [[United States presidential election, 1988|1988 campaign]] [[Read my lips: no new taxes|pledge. "Read my lips: no new taxes]]. |

||

{{listen |

{{listen |

||

| filename = George Bush 1988 No New Taxes.ogg |

| filename = George Bush 1988 No New Taxes.ogg |

||

| Line 180: | Line 180: | ||

| plain = yes |

| plain = yes |

||

|type=speech |

|type=speech |

||

| description = George H.W. Bush speaking about taxes at the 1988 Republican National Convention}} |

| description = George H.W. Bush speaking about taxes at the 1988 Republican National Convention}} He also seemed much more interested in foreign affairs than domestic concerns.<ref>Joel D. Aberbach and Gillian Peele, ''Crisis of Conservatism?: The Republican Party, the Conservative Movement and American Politics After Bush'' (2011) p. 31</ref> |

||

;1994 |

;1994 |

||

*September 27: The [[Contract with America]] is released on the steps of the [[United States Capitol]].<ref>http://www.heritage.org/Research/Lecture/The-Contract-with-America-Implementing-New-Ideas-in-the-US</ref> |

*September 27: The [[Contract with America]] is released on the steps of the [[United States Capitol]].<ref>http://www.heritage.org/Research/Lecture/The-Contract-with-America-Implementing-New-Ideas-in-the-US</ref> |

||

*November 8: Republicans [[United States House of Representatives elections, 1994|take control]] of the House of Representatives, led by conservative [[Newt Gingrich]]. The takeover was dubbed the [[Republican Revolution]]. |

*November 8: Republicans [[United States House of Representatives elections, 1994|take control]] of the House of Representatives, led by conservative [[Newt Gingrich]]. The takeover was dubbed the [[Republican Revolution]].<ref>Nicol C. Rae, ''Conservative reformers: the Republican freshmen and the lessons of the 104th Congress'' (1998) p 37</ref> |

||

;1996 |

;1996 |

||

Revision as of 04:54, 3 November 2011

The Timeline of modern American conservatism lists important events, developments and occurrences which have significantly affected conservatism in the United States. Since the 1950s, conservatism has been a major influence on American politics. The movement is most closely associated with the Republican Party. Economic conservatives favor limited government and low taxes, while social conservatives focus on moral issues and neoconservatives focus on democracy worldwide. Most give strong support to Israel.[1]

Although conservatism has much older roots in American history, the modern movement began to jell in the mid-1930s when intellectuals and politicians collaborated with businessmen to oppose the liberalism of the New Deal, led by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, newly energized labor unions, and big city Democratic machines. After World War II that coalition gained strength from new think tanks and writers who developed an intellectual rationale for conservatism.[2]

Timeline

1930s

- 1934

- Opposition to New Deal policies first takes shape as the American Liberty League. Led by conservative Democrats, such as Al Smith, it fades after Roosevelt's 1936 landslide and disbands in 1940.[3][4] Businessmen begin organizing their opposition especially to labor unions.[5]

- 1936

- President Franklin D. Roosevelt calls his opponents "conservatives" as a term of abuse, they reply that they are "true liberals".[6]

- 1937

- Roosevelt's court-packing plan alienates conservative Democrats.[7]

- Conservative Republicans (nearly all from the North) and conservative Democrats (most from the South), form the Conservative Coalition and block most new liberal proposals until the 1960s.[8]

- The Conservative Manifesto (originally titled "An Address to the People of the United States") rallies the opposition to Roosevelt. It is drafted by Senator Josiah W. Bailey (D-NC) and Arthur H. Vandenberg (R-MI).[9]

- 1938

- The Republicans make major gains in the House and Senate in the 1938 elections.[10] Conservatives had been energized in 1937-38, and liberals discouraged, by the a souring of Roosevelt's political fortunes, as his allies in the AFL and CIO battled each other; his Court packing plan was a fiasco; his attempt to purge the conservatives from the Democratic Party failed and weakened his stature; and the sharp Recession of 1937–1938 discredited his argument that New Deal policies were leading to full recovery.[11]

- Leo Strauss (1899-1973), a refugee from Nazi Germany, teaches political philosophy at the New School for Social Research in New York (1938-49) and the University of Chicago (1949-1958). Many of his students become leaders of neoconservatism.[12]

- 1939

- As Republican Senator from Ohio (1939-53) Robert A. Taft leads the conservative opposition to liberal policies (apart from public housing and aid to education, which he supported). Taft opposed much of the New Deal, American entry into World War II, NATO, and sending troops to the Korea War. He was not so much as an "isolationist" but more a staunch opponent of the ever-expanding powers of the White House. The growth of this power, Taft feared, would lead to dictatorship or at least spoil American democracy, republicanism and civil virtue.[13]

1940s

- 1940

- Peter Viereck's article "But—I'm a Conservative!" is published in the Atlantic Monthly[14]

- 1943

- Medical missionary Walter Judd (1898-1994) enters Congress (1943-63) and defines the conservative position on China as all-out support for the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-sheck and opposition to the Communists under Mao. Judd redoubled his support after the Nationalists in 1949 fled to Formosa (Taiwan).[15]

- The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) founded in Washington "to defend the principles and improve the institutions of American freedom and democratic capitalism—limited government, private enterprise, individual liberty and responsibility, vigilant and effective defense and foreign policies, political accountability, and open debate."[16]

- 1944

- Friedrich Hayek, a British libertarian economist, publishes Road to Serfdom, which is widely read in America and Britain. He warns that well-intentioned government intervention in the economy is a slippery slope that will lead to tight government controls over people's lives, just as medieval serfdom had done.[17] Hayek wins the Nobel Prize in economics in 1974.[18]

- Liberal icon Franklin D. Roosevelt is elected to fourth Presidential term, defeating liberal Republican Tom Dewey, governor of New York. Conservatives blame big city bosses and labor unions PACs (Political Action Committees).[19]

- 1945

- Ludwig von Mises (1881 – 1973) having fled Nazis, becomes professor of economics at New York University (1945-1969) where he disseminates Austrian School libertarianism[20]

- 1946

- Milton Friedman (1912 – 2006) appointed professor of economics at the University of Chicago.[21] Previously a Keynesian, Friedman moves right under the influence of his close friend George Stigler (1911-1991). He founds the market-oriented Chicago School of Economics which reshapes conservative economic theory. Stiger opposed regulation of industry as counterproductive; Friedman undermines Keynesian macroeconomics[22]. Friedman wins the Nobel Prize in 1976; others of the Chicago School who win the Nobel in Economics include Stigler, Ronald Coase (b. 1910); Gary Becker (b. 1930); and Robert Lucas, Jr. (b. 1937), among others.

- Republicans score a landslide victories in the House and Senate in off-year elections, and set about enacting a conservative agenda in the 80th Congress.[23]

- 1947

- Passage of the Taft-Hartley Act, designed by conservatives to create what they considered a proper balance between the rights of management and labor.[24]

- 1948

- Deep South Democrats lead by Strom Thurmond split from the National Democratic Party to form the pro-segregation States' Rights Democratic Party or Dixiecrat party. They are protesting support for civil rights legislation in the party platform. They make Thurmond their nominee for president in the election. Nearly all return to the Democratic party in 1949.[25]

- Liberal Republican Tom Dewey again wins the Republican nomination, to the frustration of conservatives.[26] Pundits are astonished when he loses to incumbent Democrat Harry S. Truman.

1950s

- 1950

- February 9: Senator Joseph McCarthy gives a speech saying, "I have here in my hand a list of 205—a list of names that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party." This would be the beginning of McCarthy's anti-communist pursuits.

- Conservatism reaches a low ebb in the U.S. Lionel Trilling observes that "liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition", and dismisses conservatism as a series of "irritable mental gestures which seek to resemble ideas."[27][28]

- 1952

- Dwight D. Eisenhower leads moderate and liberal Republicans to victory over Sen. Robert A. Taft, the conservative champion.[29] Ike then wins the presidency in a landslide by denouncing the failures of the Truman Administration in terms of "Korea, Communism and Corruption."[30]

- 1953

- Russell Kirk publishes The Conservative Mind, which gave shape to the conservative movement.[31]

- Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ISI) is founded by libertarian journalist Frank Chodorov (1887-1966) to counter the growing spread of collectivism; its original name was Intercollegiate Society of Individualists.[32]

- 1955

- The National Review weekly magazine is founded by William F. Buckley, Jr. (1925-2008). The editors include representative traditionalists, Catholics, libertarians and ex-Communists. The most notable were Russell Kirk, James Burnham, Frank Meyer, Willmoore Kendall, L. Brent Bozell, and Whittaker Chambers.[33]

- Russian-born philosopher Ayn Rand (1905-1982) publishes her novel Atlas Shrugged that influenced libertarians by promoting aggressive entrepreneurship, and rejecting religion and altruism.[34]

- In The liberal tradition in American, Louis Hartz claims that there has never been a European-style conservative tradition in America, and that the sole mainstream tradition is Lockean liberalism.[35]

- 1958

- Businessman Robert W. Welch Jr. (1899–1985) founds the John Birch Society, an anti-Communist secret group with chapters across the country. Welch used an elaborate control system that enabled him to keep a very tight rein on each chapters. Its major activities were circulating petitions and supporting the local police. It became a favorite target of attack from the left and was disowned by many of the prominent conservatives of the day.[36]

- In a deep economic recession the Democrats score a landslide victory, defeating many old-guard conservative Republicans. The new Congress has large Democratic majorities: 282 Democrats to 154 GOP in the House, 64 to 34 in the Senate. Nevertheless, the new Congress fails to pass any major liberal legislation as most committee chairs are Southern Democrats who support the Conservative Coalition.[37]

- Two Republicans score upsets in the face of the landslide, liberal Nelson A. Rockefeller as governor of New York, and Barry Goldwater as Senator from Arizona; both become presidential prospects

1960s

Movement conservatism emerged first as grassroots activists emerged in reaction to liberal and New Left agendas. It developed a structure that supported Goldwater in 1964 and Reagan in 1976-80. By the late 1970s local evangelical churches had joined the movement.[38][39]

- 1960

- Conservatives are angered when GOP presidential nominee Richard M. Nixon strikes a deal with liberal leader Nelson Rockefeller. Nixon agrees to put all 14 of Rockefeller's demands in the party platform, including promises that the executive branch be totally reorganized and that Rockefeller's liberal policies on economic growth, medical care for the aged and civil rights be included.[40] Led by Goldwater, conservatives vow to organize at the grass roots and take control of the GOP.[41] Nixon loses a very close election to liberal Democrat John F. Kennedy.

- Barry Goldwater publishes The Conscience of a Conservative. The book reignites the American conservative movement which rallies behind the charismatic Arizona Senator.[42]

- Buckley forms a youth group called the Young Americans for Freedom; it helps Goldwater win the 1964 nomination but is otherwise ineffective and collapses in internal bickering.[43]

- Frank S. Meyer's article, "Freedom, Tradition, Conservatism", published in Modern Age, argues that traditional conservatism and libertarianism share a common philosophical heritage. The concept comes to be known as "fusionism" and unites the two strands of thought.[44]

- 1961

- Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN) founded by Pat Robertson; its signature program The 700 Club launches in 1966.[45]

- 1962

- English political philosopher Michael Oakeshott publishes Rationalism in Politics and Other Essays, securing his position as one of the most important conservative thinkers of the 20th century.[46]

- 1963

- Governor of Alabama, Democrat George Wallace, electrifies the white South by proclaiming "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!" Wallace's angry populist anti-elitist rhetoric appeals to the poor farmers and workers who comprise a major part of the New Deal Coalition. He does well in Democratic primaries in the industrial North as well as the rural South. He exploits distrust of government, racial fear, anticommunism and a yearning for "traditional" American values.[47]

- 1964

- Goldwater defeats a series of liberal contenders to win the GOP presidential nomination and launch a conservative crusade. he is defeated in a massive landslide.[48]

- The American Conservative Union, the oldest conservative lobbying organization in the United States is founded by William F. Buckley, Jr.

- George Wallace gives a speech condemning the Civil Rights Act of 1964, claiming that it would threaten individual liberty, free enterprise and private property rights and that "The liberal left-wingers have passed it. Now let them employ some pinknik social engineers in Washington, D.C., To figure out what to do with it."[49]

- The American Spectator monthly political magazine is founded by Emmett Tyrrell; its name until 1977 was The Alternative: An American Spectator.[50]

- 1965

- Buckley gains national attention by running for mayor of New York City on the ticket of the new Conservative Party of New York State. He loses but gains visibility and respectability for the cause in the aftermath of Goldwater's defeat.[51]

- 1967

- Phyllis Schlafly launches the Eagle Trust Fund, a precursor to the conservative think tank Eagle Forum.

- 1969

- Libertarian economists, especially Milton Friedman and Walter Oi, lead the intellectual charge against the draft. Nixon abolishes it as the Vietnam War ends in 1973.[52]

- The libertarians, influenced by Ayn Rand, split from the traditionalists in the Young Americans for Freedom. They form the Society for Individual Liberty.[53]

1970s

Neoconservatism emerges as American liberals become disenchanted with Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society's welfare programs.

- 1970

James Buckley elected as United States Senator for New York with 39% of the vote, running as a candidate for the Conservative Party of New York.[54]

- 1971

- Libertarians meeting at the home of David Nolan organize the Libertarian Party which nominates John Hospers for president in 1972. John Hospers receives one electoral vote from a faithless elector.[55]

- 1972

- Phyllis Schlafly (b. 1924) forms the "STOP (Stop Taking Our Privileges) ERA" movement; it blocks passage of the Equal Rights Amendment.[56]

- 1973

- The Heritage Foundation is founded by Paul Weyrich, Edwin Feulner and Joseph Coors.[57]

- In response to the United States Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade, the National Right to Life Committee is formed, the oldest and largest pro-life organization in the United States.[58]

- The American Conservative Union and Young Americans for Freedom start the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) as a "small gathering of dedicated conservatives."[59]

- Socialist Michael Harrington popularizes[60] the term "neoconservative" for liberals who switch on foreign policy and domestic issues.[61]

- 1974

- The first March for Life, in Washington, D.C. on January 22 attracts 20,000 supporters.[citation needed]

- Robert Grant founds the American Christian Cause as an effort to institutionalize the Christian Right as a politically active social movement.[62]

- 1977

- Focus on the Family is founded by psychologist James Dobson.[63] Time Magazine calls Dobson "the nation's most influential evangelical leader."[citation needed]

- The Save Our Children movement is formed by by celebrity singer Anita Bryant to oppose the gay rights movement.[64]

- 1978

- California unleashes a tax revolt, with Proposition 13 to limit property taxes, promoted by Howard Jarvis (1903 – 1986), a long-time activist. The movement was backed by the United Organizations of Taxpayers, the Los Angeles Apartment Owners Association, and realtors' associations.[65] Preconditions included steadily rising property taxes, "stagflation" and growing anger at government waste. California's tax revolt was followed by 30 other states.[66]

- Robert Grant, Paul Weyrich, Terry Dolan, Howard Phillips, and Richard Viguerie found Christian Voice, to recruit, train, and organize Evangelical Christians to participate in elections. Grant later ousts the others.[67]

- 1979

- February: Irving Kristol is featured on the cover of Esquire under the caption, "the godfather of the most powerful new political force in America -- neoconservatism."[68]

- Jerry Falwell founds Moral Majority, a landmark in the entry of Evangelicals into the conservative political coalition.[69] Some consider this to be the birth of the Christian Right.[70][71]

1980s

The decade is marked by the rise of the Religious Right and the Reagan Revolution. A priority of Reagan's administration is the rollback of Soviet communism in Latin America, Africa and worldwide.[72]

- 1980

- April 29: Washington for Jesus is founded by John Gimenez. Pat Robertson, Jerry Falwell, Benson Idahosa and many other high-profile Evangelicals march on Washington, in support of Ronald Reagan's presidential run. Attendance estimates range from 125,000 to 200,000, although Robertson claimed an attendance closer to 500,000.[73][74][75][76][77][78]

- November 4: Ronald Reagan elected president running on a "Peace Through Strength" platform. He would serve two presidential terms (1981–1989).

- Republicans capture the Senate for the first time since 1952.

- 1983

- The International Democrat Union, an international alliance of conservative and liberal conservative political parties, is founded in London at the Konrad Adenauer Foundation and American Vice President George H. W. Bush.[79]

- 1984

- Ronald Reagan wins the presidential election in a landslide, winning 525 electoral votes; his opponent, Democrat Walter Mondale, won only 13.

- 1987

- June 12: In Berlin, President Reagan announces American terms for ending the Cold War, challenging Mikhail Gorbachev to "Tear down this wall!"; Gorbachev allows the Berlin Wall to come down in November 1989, ending Soviet control over Eastern European satellites.[80]

- Pat Robertson (b. 1930) an Evangelical minister founds the Christian Coalition, which becomes a prominent voice in the Christian Right. Robertson also telecasts news and commentary on his own network, the Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN), founded in 1961. He runs poorly in the 1988 GOP presidential race and withdraws.[81]

- 1988

- August 1: The Rush Limbaugh Show debuts on Premiere Radio Networks and will become the highest-rated talk radio show in the United States.[82]

- George H. W. Bush elected president.

1990s

Conservative think tanks 1990-97 mobilize to challenge the legitimacy of global warming as a social problem. They challenge the scientific evidence; argue that global warming will have benefits; and warn that proposed solutions would do more harm than good.[83]

- 1991

- October 15: Clarence Thomas, a black Republican, is confirmed as a Justice of the Supreme Court after extremely controversial hearings that focus less on his strongly conservative beliefs than his relationships with one of his aides, Anita Hill, who accuses him of sexual harassment.[84]

- 1992

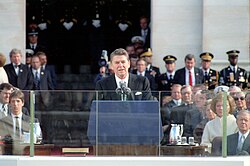

- November 3: George H. W. Bush is defeated by Bill Clinton in the presidential election. Bush had alienated much of his conservative base by breaking his 1988 campaign pledge. "Read my lips: no new taxes.

He also seemed much more interested in foreign affairs than domestic concerns.[85]

- 1994

- September 27: The Contract with America is released on the steps of the United States Capitol.[86]

- November 8: Republicans take control of the House of Representatives, led by conservative Newt Gingrich. The takeover was dubbed the Republican Revolution.[87]

- 1996

- September 21: President Bill Clinton signs the Defense of Marriage Act.[citation needed]

- October 7: Rupert Murdoch launches Fox News Network with 17 million subscribers.[citation needed] As of 2009 FNC is available to 102 million households.[citation needed]

- 1998

- September 16: Christopher W. Ruddy starts conservative new website Newsmax.com.[88]

2000s

George W. Bush embodies what he describes as compassionate conservatism, but conservatives find some of his policies controversial.[citation needed] The terror attacks on September 11 provide an opportunity for neoconservatives to have a greater influence on foreign policy.

- 2001

- January 20: George W. Bush becomes president after highly contentious recount in Florida.

- 9-11 terrorists attacks redefine conservative role in foreign policy. Americans of all stripes support War in Afghanistan.[citation needed]

- 2002

- Scott McConnell, Patrick Buchanan, and Taki Theodoracopulos found the paleoconservative magazine, The American Conservative.[citation needed]

- 2003

- November 3: The Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act is enacted.[citation needed]

- 2004

- Conservatives mobilize to reelect President Bush; he defeats John F. Kerry.[89]

- 2006

- Democrats make major gains in off-year elections, attacking the unpopular war in Iraq and the bungling of Hurricane Katrina relief.[90]

- Conservapedia is founded by Andy Schlafly.[citation needed]

- September 22: the first conference of the Values Voter Summit is held[91]

- 2008

- August 29: Alaska Governor Sarah Palin becomes the first woman on a national GOP ticket as nominee for Vice President.

- November 5. Liberal Democrat Barack Obama defeats conservative Republican John McCain by 53% to 46%. Self-identified Conservatives comprise 34% of the voters and support McCain 78%-20%. Liberals comprise 22% of the voters and support Obama 89%-10%. Moderates comprise 44% of the voters and support Obama 69%-39%.[92]

- November 5: Proposition 8 which prescribes that marriage is between a man and a woman in California is passed with 52.2% of the vote.

- 2009

- September 12: An estimated 200,000 to 800,000 people attend the Taxpayer March on Washington.[93][94][unbalanced opinion?]

- The Tea Party movement is founded.[95]

2010s

- 2010

- November 3: GOP candidates, fired up by Tea Party support, make major gains across the country in races for Congress, governorships and state legislatures. Conservative voters (self-identified) comprise 42% of the voters and support GOP House candidates 84%-13%. Liberals comprise 20% of the voters and support Democrats 90%-8%. Moderates comprise 38% of the voters and support the GOP 55%-42%.[96]

See also

- Timeline of Black conservatism in the United States

- Timeline of the Christian right

- Movement conservatism

- Neoconservatism

- Timeline of libertarian thinkers

- Timeline of the Cold War

- Timeline of United States history

- Category:American libertarians

Bibliography

- Allitt, Patrick. The Conservatives: Ideas and Personalities Throughout American History (2009)

- Carlisle, Rodney P. (2005). Encyclopedia of Politics: The Left and the Right. Sage Publications. ISBN 1412904099.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Congressional Quarterly. Congress and the Nation: 1945-1964 (1965); Congress and the Nation: 1965-1968 (1969); with new volumes every four years, 1973, 1977... etc. Highly detailed nonpartisan timelines of political activity in Washington.

- Critchlow, Donald T. The Conservative Ascendancy: How the Right Made Political History (2nd ed. 2011)

- Filler, Louis. Dictionary of American Conservatism (Philosophical Library, 1987)

- Frohnen, Bruce et al. eds. American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia (2006) ISBN 1-932236-44-9, the most detailed reference

- Nash, George H. The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945 (1976)

- Schneider, Gregory. The Conservative Century: From Reaction to Revolution (2009)

- Story, Ronald (2007). Rise of Conservatism in America, 1945-2000: A Brief History with Documents. Bedford/St. Martin's. ISBN 0312450648.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

Videos

- Allitt, Patrick N. (2009). The Conservative Tradition (CD). The Teaching Co. ISBN 9781598035483.

{{cite AV media}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help)

Notes

- ^ Michael T. Thomas, American policy toward Israel: the power and limits of beliefs (2007) pp 42-43

- ^ Patrick Allitt, The Conservatives: Ideas and Personalities Throughout American History (2009) ch 1-6 covers the story down to 1945

- ^ Frederick Rudolph, "The American Liberty League, 1934-1940," American Historical Review 56 (October 1950): 19-33, in JSTOR

- ^ George Wolfskill, The Revolt of the Conservatives: A History of the American Liberty League, 1934-1940 (1962)

- ^ Kim Phillips-Fein, Invisible Hands: The Businessmen's Crusade Against the New Deal (2009)

- ^ O'Connor, Brendan. A political history of the American welfare system: when ideas have consequences. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004, p. 38 ISBN 0742526682[1]

- ^ Jeff Shesol, Supreme Power: Franklin Roosevelt vs. the Supreme Court (2010)

- ^ James T. Patterson, "A Conservative Coalition Forms in Congress, 1933-1939," Journal of American History Vol. 52, No. 4 (Mar., 1966), pp. 757-772 in JSTOR

- ^ John Robert Moore, "Senator Josiah W. Bailey and the "Conservative Manifesto" of 1937," Journal of Southern History Vol. 31, No. 1 (Feb., 1965), pp. 21-39 in JSTOR

- ^ Milton Plesur, "The Republican Congressional Comeback of 1938," Review of Politics, Oct 1962, Vol. 24 Issue 4, pp 525-562 in JSTOR

- ^ William E. Leuchtenburg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal: 1932-1940 (1963) pp 231-74

- ^ John P. East, "Leo Strauss and American Conservatism," Modern Age, Winter 1977, Vol. 21 Issue 1, pp 2-19 online

- ^ Geoffrey Matthews, "Robert A. Taft, the Constitution and American Foreign Policy, 1939-53," Journal of Contemporary History, July 1982, Vol. 17 Issue 3, pp 507-522

- ^ The Atlantic, April, 1940 online

- ^ Lee Edwards, Missionary for Freedom: The Life and Times of Walter Judd (1990)

- ^ Murray L. Weidenbaum, The competition of ideas: the world of the Washington think tanks (2009) p. 23

- ^ F. A. Hayek, The Road to Serfdom (1944; 2nd ed. 2010); 2nd ed. by Bruce Caldwell with prepublication reports on Hayek's manuscript, and forewords to earlier editions by John Chamberlain, Milton Friedman, and Hayek himself.

- ^ Nicholas Wapshott, Keynes Hayek: The Clash That Defined Modern Economics (2011)

- ^ David M. Jordan, FDR, Dewey, and the Election of 1944 (2011)

- ^ Israel M. Kirzner, Ludwig von Mises: the man and his economics (2001)

- ^ He retired in 1977 and moved to the Hoover Institution at Stanford. Milton and Rose Friedman, Two Lucky People: Memoirs (1999)

- ^ Alan O. Ebenstein, Milton Friedman: A Biography (2009)

- ^ Susan M. Hartmann, Truman and the 80th Congress (1971)

- ^ Harry A. Brown, and Emily Clark Millis, From the Wagner Act to Taft-Hartley: A Study of National Labor Policy and Labor Relations (1965)

- ^ Kari A. Frederickson, The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932-1968 (2000)

- ^ Michael Bowen, The Roots of Modern Conservatism: Dewey, Taft, and the Battle for the Soul of the Republican Party (2011)

- ^ Trilling, Lionel (1950). The liberal imagination: essays on literature and society. ISBN 9781590172834.

- ^ Barone, Michael (February 11, 2009). "Buckley: A History Changer". CBS News.

- ^ James T. Patterson, Mr. Republican: A Biography of Robert A. Taft (1972)

- ^ Stephen Ambrose, Eisenhower Soldier and President (2007) p 277

- ^ W. Wesley McDonald, Russell Kirk and the Age of Ideology (2004)

- ^ Lee Edwards, Educating for Liberty: The first Half-century of the Intercollegiate Studies Institute (2003)

- ^ John B. Judis, William F. Buckley, Jr.: Patron Saint of the Conservatives (1990)

- ^ Jennifer Burns, Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right (2009)

- ^ James T. Kloppenberg, "Review: In Retrospect: Louis Hartz's The Liberal Tradition in America," Reviews in American History Vol. 29, No. 3 (Sept 2001), pp. 460-478 in JSTOR

- ^ Jonathan Schoenwald, A Time for Choosing: The Rise of Modern American Conservatism (2002) pp 62–99

- ^ Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1945-1964 (1965) pp 28-34

- ^ Rick Perlstein, "Thunder on the Right: The Roots of Conservative Victory in the 1960s," OAH Magazine of History, Oct 2006, Vol. 20 Issue 5, pp 24-27

- ^ James A. Hijiya, "The Conservative 1960s," Journal of American Studies, Aug 2003, Vol. 37 Issue 2, pp 201-28

- ^ Theodore H. White, The Making of the President 1960 (1961) pp 197-99 online

- ^ Laura Jane Gifford, The Center Cannot Hold: The 1960 Presidential Election and the Rise of Modern Conservatism (2009)

- ^ Robert Alan Goldberg, Barry Goldwater (1995)

- ^ Gregory L. Schneider, Cadres for Conservatism: Young Americans for Freedom and the Rise of the Contemporary Right (1998)

- ^ Bliese, John R. E. The Greening Of Conservative America. Westview Press, 2002 ISBN 0813340322 p. 4-5

- ^ David Marley, -Pat Robertson: an American life (2007) p. 97

- ^ Paul Franco, Michael Oakeshott: An Introduction (2004)

- ^ Dan T. Carter. The politics of rage: George Wallace, the origins of the new conservatism, and the transformation of American politics, LSU Press, 2000. pg. 12.

- ^ Rick Perlstein, Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus (2004)

- ^ Geroge C. Wallace "The Civil Rights Movement: Fraud, Sham, and Hoax" July 4, 1964

- ^ R. Emmett Tyrrell, Jr., ed., Orthodoxy: The American Spectator's 20th Anniversary Anthology (1987)

- ^ Jonathan Schoenwald, A Time for Choosing: The Rise of Modern American Conservatism (2002) pp 162–89

- ^ Bernard Rostker, I want you!: the evolution of the All-Volunteer Force (2006) pp 66-70, 749

- ^ Jennifer Burns, Goddess of the market: Ayn Rand and the American Right (2009) p 257

- ^ Sullivan, Timothy J. New York State and the rise of modern conservatism: redrawing party lines. SUNY Press, 2009 ISBN 079147643X p. 135

- ^ Walker, Jesse (June 13, 2011). "John Hospers, RIP". Reason. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ Donald T. Critchlow, Phyllis Schlafly and Grassroots Conservatism: A Woman's Crusade (Princeton University Press, 2005) pp 212-42

- ^ Donald E. Abelson (2002). Do Think Tanks Matter?: Assessing the Impact of Public Policy Institutes. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 9780773523173.

- ^ Donald T. Critchlow, The politics of abortion and birth control in historical perspective (1995) p 140

- ^ John B. Judis, William F. Buckley, Jr.: Patron Saint of the Conservatives (2001) pp 356-7

- ^ see his article

- ^ Justin Vaïsse, Neoconservatism: the biography of a movement (2010) p. 298

- ^ Glenn H. Utter and John Woodrow Storey, The religious right: a reference handbook (2001) p. 88

- ^ Dan Gilgoff, The Jesus Machine: How James Dobson, Focus on the Family, and Evangelical America Are Winning the Culture War (2008)

- ^ Roger Chapman, ed. Culture wars: an encyclopedia of issues, viewpoints, and voices (2010) vol. 1 p. 55

- ^ Smith, D. A. (1999). "Howard Jarvis, Populist Entrepreneur: Reevaluating the Causes of Proposition 13". Social Science History. 23 (2): 173–210. JSTOR 1171520.

- ^ Ballard C. Campbell, "Tax revolts and political change," Journal of Policy History, Jan 1998, Vol. 10 Issue 1, pp 153-78

- ^ Glenn H. Utter and John Storey, eds. The religious right: a reference handbook (2001) p 123

- ^ R. Emmett Tyrrell, After the Hangover: The Conservatives' Road to Recovery (2010) p. 36

- ^ Susan Harding, The book of Jerry Falwell: fundamentalist language and politics (2001) p. 285

- ^ Martin, William (1996). With God on Our Side: The Rise of the Religious Right in America. New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 0553067451.

- ^ Sara, Diamond (1995). Roads to Dominion. New York: Guilford Press. ISBN 0898628644.

- ^ John Ehrman, The Eighties: America in the Age of Reagan (2006)

- ^ Oldfield, Duane Murray (1996). The Right and the Righteous: the Christian Right Confronts the Republican Party. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 139–140. ISBN 9780847681907.

- ^ Associated Press (April 29, 1980). "125,000 Sing, Pray in 'Washington for Jesus' Rally". Eugene Register-Guard. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ Diamond, Sara (1995). Roads to Dominion: Right-Wing Movements and Political Power in the United States. Guilford Press. p. 175. ISBN 9780898628647.

- ^ Westerlund, David (1996). Questioning the Secular State: The Worldwide Resurgence of Religion in Politics. Hurst Publishers. p. 36. ISBN 9781850652410.

- ^ Rojas, Aurelio (October 13, 1995). "A Pilgrimage for Bay Area Blacks". San Francisco Chronicle.

Following are estimates by the National Park Service of attendance at other major demonstrations, rallies and events in the nation's capital: ... Washington For Jesus religious rally, 1980: 200,000

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Associated Press (April 30, 1988). "'WASHINGTON FOR JESUS' RALLY DRAWS CROWD TO CAPITAL". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ Goldman, Ralph Morris (2002). The Future Catches Up: Transnational Parties and Democracy. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 418. ISBN 9780595228881.

- ^ Romesh Ratnesar, Tear down this wall: a city, a president, and the speech that ended the Cold War (2009) p 6

- ^ David Harrell Jr., Pat Robertson: A Life and Legacy (2010)

- ^ Joseph Turow, Media Today (4th ed. 2011) p 376

- ^ Aaron M. McCright and Riley E. Dunlap, "Defeating Kyoto: The Conservative Movement's Impact on U.S. Climate Change Policy," Social Problems, Aug 2003, Vol. 50 Issue 3, pp 348-73 in JSTOR

- ^ Dan Thomas, Craig McCoy and Allan McBride, "Deconstructing the Political Spectacle: Sex, Race, and Subjectivity in Public Response to the Clarence Thomas/Anita Hill "Sexual Harassment" Hearings," American Journal of Political Science Vol. 37, No. 3 (Aug., 1993), pp. 699-720 in JSTOR

- ^ Joel D. Aberbach and Gillian Peele, Crisis of Conservatism?: The Republican Party, the Conservative Movement and American Politics After Bush (2011) p. 31

- ^ http://www.heritage.org/Research/Lecture/The-Contract-with-America-Implementing-New-Ideas-in-the-US

- ^ Nicol C. Rae, Conservative reformers: the Republican freshmen and the lessons of the 104th Congress (1998) p 37

- ^ Poe, Richard (2004). Hillary's Secret War: The Clinton Conspiracy to Muzzle Internet Journalists. Nashville, TN: WND Books. pp. 171–172. ISBN 0-7852-6013-7.

- ^ John C. Green, Mark J. Rozell and Clyde Wilcox, The Values Campaign?: The Christian Right and the 2004 Elections (2006)

- ^ David B. Magleby and Kelly D. Patterson, eds. The Battle for Congress: Iraq, Scandal, and Campaign Finance in the 2006 Election (2008)

- ^ http://www.afajournal.org/2006/april/406noi.asp

- ^ See Exit Poll results

- ^ Markman, Joe (September 15, 2009). "Crowd estimates vary wildly for Capitol march". Los Angeles Times. latimes.com. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ^ Kleefeld, Eric (September 14, 2009). "FreedomWorks Cuts Estimate For Crowd At Its 9/12 Rally By One Half". Talking Points Memo. (tpmdc.talkingpointsmemo.com). Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ^ Scott Rasmussen and Doug Schoen, Mad As Hell: How the Tea Party Movement Is Fundamentally Remaking Our Two-Party System (2010).

- ^ See 2010 Exit Polls