Western African Ebola virus epidemic

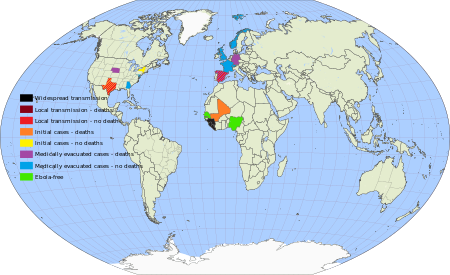

Situation map of the outbreak in West Africa | |

| Date | December 2013 – present[1] |

|---|---|

| Casualties | |

Note: the CDC estimates that actual cases in the most infected countries are two to three times higher than officially reported numbers.[3][4]

| |

As of 2014[update], the most widespread epidemic of Ebola virus disease (EVD) in history is currently ongoing in several West African countries.[7][8] It has caused significant mortality, with a reported case fatality rate (CFR) of about 71%.[9][10] It began in Guinea in December 2013 and then spread to Liberia and Sierra Leone.[10] A small outbreak of twenty cases occurred in Nigeria, and one case occurred in Senegal. The latter two countries were declared disease-free on 20 October 2014 after a 42 day waiting period.[5][11][12] Secondary infections of medical workers have occurred in the United States and Spain[13][14] but have not spread further. One imported case has been identified in Mali[15][16] with two more possible cases under investigation.[17] An independent outbreak of EVD in the Democratic Republic of the Congo that started in August 2014 has been shown by genetic analysis to be unconnected to the main epidemic.

As of 25 October 2014[update], the World Health Organization (WHO) reported a total of 13,703 suspected cases and 4,922 deaths,[18] though the WHO believes that this substantially understates the magnitude of the outbreak[19] with true figures numbering three times as many cases as have been reported.[3][20] The assistant director-general of the WHO warned in mid-October that there could be as many as 10,000 new EVD cases per week by December 2014.[21] Almost all of the cases have occurred in the three initial countries.

Some countries have encountered difficulties in their efforts to control the epidemic.[22] In some areas, people have become suspicious of both the government and hospitals, some of which have been attacked by angry protesters who believe either that the disease is a hoax or that the hospitals are responsible for the disease. Many of the areas seriously affected by the outbreak are areas of extreme poverty with limited access to the soap and running water needed to help control the spread of disease.[23] Other factors include reliance on traditional medicine and cultural practices that involve physical contact with the deceased, especially death customs such as washing and kissing[24] the body of the deceased.[25][26][27] Some hospitals lack basic supplies and are understaffed, increasing the chance of staff catching the virus themselves. In August, the WHO reported that ten percent of the dead have been health care workers.[28] By the end of August, the WHO reported that the loss of so many health workers was making it difficult for them to provide sufficient numbers of foreign medical staff.[29] In September, the WHO estimated that the countries' capacity for treating EVD patients was insufficient by the equivalent of 2,122 beds. By the end of October many of the hospitals in the affected area had become dysfunctional or had been closed, leading some health experts to state that the inability to treat other medical needs may be causing "an additional death toll [that is] likely to exceed that of the outbreak itself".[30][31]

By September 2014, Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF), the largest NGO working in the affected countries, had grown increasingly critical of the international response. Speaking on 3 September, the president of MSF spoke out concerning the lack of assistance from the United Nations member countries saying, "Six months into the worst Ebola epidemic in history, the world is losing the battle to contain it."[32] A United Nations spokesperson stated, "They could stop the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 6 to 9 months, but only if a 'massive' global response is implemented."[33] The Director-General of the WHO, Margaret Chan, called the outbreak "the largest, most complex and most severe we've ever seen" and said that it is "racing ahead of control efforts".[33] In a 26 September statement, the WHO said, "The Ebola epidemic ravaging parts of West Africa is the most severe acute public health emergency seen in modern times."[34]

| Articles related to the |

| Western African Ebola virus epidemic |

|---|

|

| Overview |

| Nations with widespread cases |

| Other affected nations |

| Other outbreaks |

Epidemiology

Outbreak

Researchers believe that a 2-year-old boy, later identified as Emile Ouamouno, who died in December 2013 in the village of Meliandou, Guéckédou Prefecture, Guinea, was the index case of the current Ebola virus disease epidemic.[35][36] Reports suggest that his family hunted bats of the Ebola-harboring species Hypsignathus monstrosus and Epomops franqueti for bushmeat, which may have been the original source of the infection.[37][38] His mother, sister, and grandmother then became ill with similar symptoms and also died. People infected by those initial cases spread the disease to other villages.[1] Although Ebola represents a major public health issue in sub-Saharan Africa, no cases had ever been reported in West Africa and the early cases were diagnosed as other diseases more common to the area. Thus, the disease had several months to spread before it was recognized as Ebola.[1][39]

On 19 March, the Guinean Ministry of Health acknowledged a local outbreak of an undetermined viral hemorrhagic fever that had sickened at least 35 people and killed 23. "We thought it was Lassa fever or another form of cholera but this disease seems to strike like lightning. We are looking at all possibilities, including Ebola, because bushmeat is consumed in that region and Guinea is in the Ebola belt."[40] By 24 March, MSF had set up an isolation facility in Guéckédou.[41]

On 25 March, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that Guinea's Ministry of Health had reported an outbreak of Ebola virus disease in four southeastern districts, with suspected cases in the neighbouring countries of Liberia and Sierra Leone being investigated. In Guinea, a total of 86 suspected cases, including 59 deaths (case fatality ratio: 68.5%), had been reported as of 24 March.[42] By 31 March, there were 112 suspected and confirmed cases including 70 deaths, while two cases were reported from Liberia of people who had recently traveled to Guinea.[42] On 30 April, Guinea's Ministry of Health reported 221 suspected and confirmed cases with 146 deaths, including 26 health care workers with 16 deaths. By late May, the outbreak had spread to Conakry, Guinea's capital, a city of about two million inhabitants.[42] On 28 May, the total number of cases reported had reached 281 with 186 deaths.[42]

In Liberia, the disease was reported in four counties by mid-April and cases in Liberia's capital Monrovia were reported in mid-June.[43][44] The outbreak then spread to Sierra Leone and progressed rapidly. A study of the virus genomes determined that twelve Sierra Leone residents had become infected while attending a funeral in Guinea.[45] On 25 May, the first cases in the Kailahun District, near the border with Guéckédou in Guinea, were reported.[46] By 20 June, there were 158 suspected cases, mainly in Kailahun and the adjacent district of Kenema.[47] By 17 July, the total number of suspected cases in the country stood at 442, overtaking the number in Guinea and Liberia.[48] By 20 July, additional cases of the disease had been reported in the Bo District and the first case in Freetown, Sierra Leone's capital, was reported in late July.[49][50]

The first death in Nigeria was reported on 25 July:[51] a Liberian-American with Ebola flew from Liberia to Nigeria and died in Lagos soon after arrival.[52] As part of the effort to contain the disease, possible contacts were monitored – 353 in Lagos and 451 in Port Harcourt.[53] On 22 September, the WHO reported a total of 20 cases, including eight deaths. The WHO's representative in Nigeria officially declared Nigeria Ebola-free on 20 October after no new active cases were reported in the follow up contacts.[5]

On 29 August, Senegalese Minister of Health announced the first case in Senegal. The victim was subsequently identified as a Guinean national who had been exposed to the virus and had been under surveillance, but had travelled to Dakar by road and fallen ill after arriving.[54] This person subsequently recovered, and on 17 October, the WHO officially declared that the outbreak in Senegal had ended.[55]

Two Spanish health care workers contracted Ebola and were transferred to Spain for treatment where they both died. In October, a nursing assistant who had been part of their health care team was diagnosed with Ebola, making this the first case of Ebola contracted outside of Africa. The nursing assistant recovered and was declared disease-free on 19 October.[57] There have been cases of Ebola in the United States of America as well. A Liberian man who had traveled from Liberia to be with his family in Texas was declared to have Ebola and subsequently died on 8 October. Two nurses who had cared for the patient contracted the disease and as of 20 October remain in treatment.[58]Both of these nurses have subsequently recovered and tested Ebola-free 27 October 2014.

Countries with widespread transmission

Guinea

On 25 March, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that Guinea's Ministry of Health had reported an outbreak of Ebola virus disease in four southeastern districts. In Guinea, a total of 86 suspected cases, including 59 deaths (case fatality ratio: 68.5%), had been reported as of 24 March.[42] On 31 March, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sent a five-person team to assist Guinea's Ministry of Health and the WHO as they led an international response to the Ebola outbreak.[42]

Thinking that the virus was contained, MSF closed its treatment centers in May leaving only a small skeleton staff to handle the Macenta region. However, high numbers of new cases reappeared in the region in late August. According to Marc Poncin, a coordinator for MSF, the new cases were related to persons returning to Guinea from neighbouring Liberia or Sierra Leone.[59]

It has been reported that some people in this area believe that health workers have been purposely spreading the disease to the people, while others believe that the disease does not exist. Riots recently broke out in the regional capital, Nzérékoré, when rumors were spread that people were being contaminated when health workers were spraying a market area to decontaminate it.[60]

On 18 September, it was reported that the bodies of a team of Guinean health and government officials, accompanied by journalists, who had been distributing Ebola information and doing disinfection work, were found in a latrine in the town of Womey near Nzérékoré.[61] The workers had been murdered by residents of the village after they initially went missing after a riot against the presence of the health education team. Government officials said "the bodies showed signs of being attacked with machetes and clubs" and "three of them had their throats slit."[62]

WHO estimated on 21 September that Guinea's capacity to treat EVD cases falls short by the equivalent of 40 beds.[22] On 13 October, France indicated it would build more treatment centers.[63] On 18 October, Egypt sent three tons of medical aid, consisting of medicine and medical equipment.[64]

On 19 October Guinea have reported two new districts with EVD cases. The Kankan district, on the border with the Côte d'Ivoire and a major trade route to Mali, confirmed 1 case. Kankan also borders the district of Kerouane in this country, one of the areas with the most intense virus transmissions. The Faranah district to the north of the border area of Koinadugu in Sierra Leone in the north also reported a confirmed case. Koinadugu was one on the last EVD free regions in that country. According to the latest WHO report this new developmental highlights the need for increased surveillance of cross border traffic in an effort to contain the disease to the three most affected countries.[18]

Liberia

In Liberia, the disease was reported in Lofa and Nimba counties in late March.[65] In July, the health ministry implemented measures to improve the country's response.[66] On 27 July, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the Liberian president, announced that Liberia would close its borders, with the exception of a few crossing points such as the airport, where screening centres would be established.[67] Football events were banned,[68] schools and universities were closed,[69][70] and the worst-affected areas in the country were to be placed under quarantine.[71]

In August, President Sirleaf declared a national state of emergency, noting that it might require the "suspensions of certain rights and privileges".[72] The National Elections Commission announced that it would be unable to conduct the scheduled October 2014 senatorial election and requested postponement,[73] one week after the leaders of various opposition parties had publicly taken different sides on the question.[74] In late August, Liberia's Port Authority cancelled all "shore passes" for sailors from ships coming into the country's four seaports.[75] As of 8 September, Ebola had been identified in 14 of Liberia's 15 counties.[76]

With only 50 physicians in the entire country—one for every 70,000 Liberians—Liberia already faced a health crisis even before the outbreak.[77] In September the US CDC reported that some hospitals had been abandoned while those which were still functioning lacked basic facilities such as running water, rubber gloves, and sanitizing supplies.[78] The WHO estimated that Liberia's capacity to treat EVD cases fell short by the equivalent of 1,550 beds.[22] In September, a new 150-bed treatment clinic was opened in Monrovia. At the opening ceremony six ambulances were already waiting with potential patients. More patients were waiting by the clinic after making their way on foot with the help of relatives.[79]

In October, the Liberian ambassador in Washington was reported as saying that he feared that his country may be "close to collapse".[77] On 12 October, Liberian nurses threatened a strike over wages.[80] On 14 October, another 100 U.S. troops arrived, bringing the total to 565 to aid in the fight against the disease.[81] On 16 October, U.S. President Obama authorized, via executive order, the use of National Guard and reservists to Liberia.[82] A report of 15 October indicates that Liberia needs 80,000 more body bags and about 1 million protective suits for the next six months.[83] On October 20, the Liberian ambassador to Canada indicated it was time to try the ZMapp drug on the infected in Liberia.[84]

By 19 October only one area in Liberia, Grand Gedeh, had yet to report an EVD case; 14 out of the 15 districts had reported cases. In the capital of Monrovia 305 new cases were reported in the past week alone.[18] On 24 October this district became the last to report cases. Grand Gedeh reported 4 cases of which 2 tested positive.[85] On 27 October, U.S. soldiers returning from Liberia were put in isolation upon their arrival in Italy.[86]

Sierra Leone

The first person reported infected in the spread to Sierra Leone was a tribal healer. She had treated one or more infected people and died on 26 May. According to tribal tradition, her body was washed for burial and this appears to have led to infections in women from neighbouring towns.[87] On 11 June, Sierra Leone shut its borders for trade with Guinea and Liberia and closed some schools in an attempt to slow the spread of the virus.[88] On 30 July, the government began to deploy troops to enforce quarantines.[89]

On 29 July, well-known physician Sheik Umar Khan, Sierra Leone's only expert on hemorrhagic fever, died after contracting Ebola at his clinic in Kenema. Khan had long worked with Lassa fever, a disease that kills over 5,000 a year in Africa. He had expanded his clinic to accept Ebola patients. Sierra Leone's president, Ernest Bai Koroma, celebrated Khan as a "national hero".[87]

In August, awareness campaigns in Freetown, Sierra Leone's capital, were delivered over the radio and through loudspeakers.[90] Also in August, Sierra Leone passed a law that subjected anyone hiding someone believed to be infected to two years in jail. At the time the law was enacted, a top parliamentarian criticised failures by neighbouring countries to stop the outbreak.[91]

In an attempt to control the disease, Sierra Leone imposed a three-day lockdown on its population from 19 to 21 September. During this period 28,500 trained community workers and volunteers went door-to-door providing information on how to prevent infection, as well as setting up community Ebola surveillance teams.[92] On 22 September, government officials said that the three-day lockdown had obtained its objective and would not be extended. Eighty percent of targeted households were reached in the operation. A total of around 150 new cases were uncovered, although reports from remote locations had not yet been received.[93]

WHO estimated on 21 September that Sierra Leone's capacity to treat EVD cases falls short by the equivalent of 532 beds.[22] There have been reports that political interference and administrative incompetence have hindered the flow of medical supplies into the country.[94] On 4 October, Sierra Leone recorded 121 fatalities, the largest number in a single day.[95] On 8 October, Sierra Leone burial crews went on strike.[96] On 12 October, it was reported that the U.K. would begin providing military support to Sierra Leone.[97]

The last district in Sierra Leone untouched by the Ebola virus has declared Ebola cases. According to Abdul Sesay, a local health official, 15 suspected deaths with two confirmed cases of the deadly disease were reported on 16 October in the village of Fakonya. The village is 60 miles from the town of Kabala in the center of a mountainous region of the Koinadugu district. All of the districts in this country now have confirmed cases of Ebola.[98] On 24 October, U.K. Prime Minister Cameron pledged 80 million (pounds) to Sierra Leone's fight against the virus,and asked other countries in Europe to donate.[99] On 28 October, the Sierra Leone government took exception to a ban, imposed on the same day, by the Australian government for any visas issued towards individuals from the affected west African region. Amnesty International stated it was a "narrow approach".[100] On October 30th about 300 UK personnel, with 3 helicopters and 32 trucks, arrived on the British ship Argus.[101]

Countries with limited local transmission

Spain

On 5 August 2014, the Brothers Hospitallers of St. John of God confirmed that Brother Miguel Pajares, who had been volunteering in Liberia, had become infected. He was evacuated to Spain on 6 August, and died on 12 August.[102] On 21 September it was announced that Brother Manuel García Viejo, another Spanish citizen who was medical director at the San Juan de Dios Hospital in Lunsar, had been evacuated to Spain from Sierra Leone after being infected with the virus. His death was announced on 25 September.[103]

In October, a nursing assistant, later identified as Teresa Romero, who had cared for these patients became unwell and on 6 October tested positive for Ebola.[104] A second test confirmed the diagnosis,[105] making this the first confirmed case of Ebola transmission outside Africa. On 19 October, it was reported that Romero had recovered and was officially declared to be Ebola free.[57]

United States

On 30 September, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declared its first case of Ebola virus disease. The CDC disclosed that Thomas Eric Duncan became infected in Liberia and traveled to Texas on 20 September. On 26 September he fell ill and sought medical treatment but was sent home with antibiotics. He returned to the hospital by ambulance on 28 September and was placed in isolation and tested for Ebola.[106][107] Thomas Duncan died on 8 October.[108] On 19 October his four relatives and 44 other people who had had contact with Duncan were released from quarantine.[109]

On 12 October, the CDC confirmed that a health worker who treated Duncan tested positive for the Ebola virus, making this the first known transmission of the disease in the United States. Two days later a second health worker at the same hospital tested positive for Ebola.[110] Nina Pham, the first nurse infected, was transferred to a facility at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland on 16 October,[111] while the second, Amber Joy Vinson, was transferred to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia.[58] Both patients recovered and were declared free of the virus by 24 October.[112] A fourth case of Ebola virus disease was diagnosed on 23 October in New York City. MSF doctor Craig Spencer had recently returned from treating Ebola patients in West Africa where he contracted the disease.[113] On 28 October, Spencer's condition was listed as serious; he had "entered the next phase" of the viral infection, as per Bellevue hospital.[114]

Countries with initial cases

Mali

On 23 October, the first case of Ebola disease in Mali was confirmed; a two year-old girl who had returned from Guinea.[16] According to a health ministry official, the girl's mother had died in Guinea a few weeks previously and the child was then brought by relatives to Mali.[15] It was reported that she and her grandmother had arrived in Bamako on 20 October after attending the funeral of her father, who died of Ebola. They then arrived in Kayes the next day.[115]

On 24 October, a health official reported that the girl had died as a result of Ebola disease.[116] Many people may have been exposed during her bus journey from Guinea, when she was already symptomatic.[117][118] On 25 October, Mauritania, as a preventive measure, closed its border with Mali.[119] On 28 October the WHO stated "the possibility of setting up a treatment center in Kayes" had been discussed.[120]On 29 October WHO reported that 82 contacts are being traced with 57 in Kayes and 27 in Bamako.[2]

On 31 October, Reuters reported that two more suspected cases of Ebola virus disease had been identified.[17]

Countries with contained spread

Senegal

In March, the Senegal Ministry of Interior closed the southern border with Guinea,[121] but on 29 August the Senegal health minister announced Senegal's first case, a university student from Guinea who was being treated in a Dakar hospital.[54] The case was a native of Guinea who had traveled to Dakar, arriving on 20 August. On 23 August, he sought medical care for symptoms including fever, diarrhoea, and vomiting. He received treatment for malaria, but did not improve and left the facility. Still experiencing the same symptoms, on 26 August he was referred to a specialized facility for infectious diseases, and was subsequently hospitalized.[54]

On 28 August, authorities in Guinea issued an alert informing medical services in Guinea and neighbouring countries that a person who had been in close contact with an Ebola infected patient had escaped their surveillance system. The alert prompted testing for Ebola at the Dakar laboratory, and the positive result launched an investigation and triggered urgent contact tracing.[54] On 10 September, it was reported that the student had recovered but health officials would continue to monitor his contacts for 21 days.[122] No further cases were reported.[123] and on 17 October, the WHO officially declared that the outbreak in Senegal had ended.[6]

The WHO have officially commended the Senegalese government, and in particular the President Macky Sall and the Minister of Health Dr Awa Coll-Seck, for their quick response in quickly isolating the patient and tracing and following up 74 contacts as well as for their public awareness campaign. This acknowledgement was also extended to MSF and the CDC for their assistance.[124]

Nigeria

The first case in Nigeria was a Liberian-American, Patrick Sawyer, who flew from Liberia to Nigeria's commercial capital Lagos on 20 July. Sawyer became violently ill upon arriving at the airport and died five days later. In response, the Nigerian government observed all of Sawyer's contacts for signs of infection and increased surveillance at all entry points to the country.[125] On 6 August, the Nigerian health minister told reporters, "Yesterday the first known Nigerian to die of Ebola was recorded. This was one of the nurses that attended to the Liberian. The other five [newly confirmed] cases are being treated at an isolation ward."[126]

On 19 August, it was reported that the doctor who treated Sawyer, Ameyo Adadevoh, had also died of Ebola disease. Adadevoh was posthumously praised for preventing the index case (Sawyer) from leaving the hospital at the time of diagnosis, thereby playing a key role in curbing the spread of the virus in Nigeria.[127][128]

On 22 September, the Nigeria health ministry announced, "As of today, there is no case of Ebola in Nigeria. All listed contacts who were under surveillance have been followed up for 21 days." According to the WHO, 20 cases had been confirmed with the death of eight. Four of the dead were health care workers who had cared for Sawyer. In all, 529 contacts had been followed and of that date they had all completed a 21 day mandatory period of surveillance.[129] The WHO's representative in Nigeria officially declared Nigeria to be Ebola free on 20 October after no new active cases were reported in the follow up contacts, stating it was a "spectacular success story".[5]

On 9 October, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) acknowledged Nigeria's positive role in controlling the effort to contain the Ebola outbreak. "We wish to thank the Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria, and the staff of the Ebola Emergency Centre who coordinated the management of cases, containment of outbreaks and treatment protocols in Nigeria." Nigeria's quick responses, including intense and rapid contact tracing, surveillance of potential contacts, and isolation of all contacts were of particular importance in controlling and limiting the outbreak, according to the ECDC.[130] Complimenting Nigeria's successful efforts to control the outbreak, "the usually measured WHO declared the feat 'a piece of world-class epidemiological detective work'."[131]

Countries with medically evacuated cases

A number of people who had become infected with Ebola virus disease have been medically evacuated to treatment in isolation wards in Europe or the US. These are mostly health workers with one of the NGOs in the area. Germany is currently the only country which has agreed to treat non citizens.[132]

Most medical evacuations have been carried out on Gulfstream III planes operated by Phoenix Air.[133]

France

A French volunteer health worker, working for MSF in Liberia, contracted EVD and was flown to France on 18 September. After successful treatment at a military hospital near Paris, she was discharged on 4 October.[134]

According to the FujiFilm company, the woman was treated with their drug favipiravir. This fact has not yet been confirmed by the French health authorities.[135]

Germany

Germany set up an isolation ward to care for six patients at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. On 27 August, a Senegalese epidemiologist working for the WHO in Sierra Leone became the first patient. On 4 October he was discharged after being declared noninfectious.[136]

The WHO requested that a Ugandan doctor working in Sierra Leone who had contracted the disease be treated in Germany. The request was granted by Germany and he was flown to the country on 3 October. The patient is being treated in an isolation unit at the University Hospital in Frankfurt. The doctor was working for an Italian NGO in Sierra Leone, according to Stefan Gruettner, the State Health Minister of Hessen.[137]

On 9 October, a third patient was medevaced to Leipzig, Germany. The 56-year-old Sudanese man, who worked as a UN employee in Liberia, was transferred to St Georg Hospital in Leipzig.[138] He died on 14 October, becoming the first person on German soil to die of Ebola.[139]

Norway

On 6 October, MSF announced that one of their workers, a Norwegian national, had become infected in Sierra Leone. On 7 October the woman, Silje Lehne Michalsen, was admitted to a special isolation unit at Oslo University Hospital.[140][141] On 20 October, it was announced that she had been successfully treated and had been discharged. It was reported that Michalsen had received an unspecified drug as part of her treatment plan.[142] After discharge Michalsen remarked, "For three months I saw the total absence of an international response. For three months I became more and more worried and frustrated."[141]

United Kingdom

An isolation unit at the Royal Free Hospital, London, received its first case on 24 August. William Pooley, a British nurse, was evacuated from Sierra Leone by the Royal Air Force on a specially-equipped C-17 aircraft. He was released from hospital on 3 September.[143][144]

United States

A number of American citizens who contracted Ebola virus disease while working in the affected areas have been evacuated to the United States for treatment; none have died.

Separate outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

| |

| Casualties | |

|---|---|

In August 2014, the WHO reported an outbreak of Ebola virus in the Boende District, Democratic Republic of the Congo.[146] They confirmed that the current strain of the virus is the Zaire Ebola species, which is common in the country (the name "Zaire" is the former name of DR Congo). The virology results and epidemiological findings indicate no connection to the current epidemic in West Africa. This is the country's seventh Ebola outbreak since 1976.[147][148]

In August, 13 people were reported to have died of Ebola-like symptoms in the remote northern Équateur province, a province that lies about 1,200 km (750 mi) north of the capital Kinshasa.[148] The initial case was a woman from Ikanamongo Village who became ill with symptoms of Ebola after she had butchered a bush animal that her husband had killed. The following week, relatives of the woman, several health-care workers who had treated the woman, and individuals with whom they had been in contact came down with similar symptoms.[148] On 26 August, the Équateur Province Ministry of Health notified the WHO of an outbreak of Ebola.[148] According to the WHO, as of 27 October 2014[update] there have been 66 cases with 49 deaths including eight healthcare workers. All contact cases have been followed up.[2]

In a show of African solidarity, Congo will train more than 1,000 volunteers in the capital city of Kinshasa to help Ebola-ravaged West Africa.[149] On 23 October, medical investigators set out to the Congo jungle to track the source of the latest Ebola outbreak.[150]

Virology

Ebola virus disease is caused by four of five viruses classified in the genus Ebolavirus. Of the four disease-causing viruses, Ebola virus (formerly and often still called the Zaire virus), is the most dangerous and is the species responsible for the ongoing epidemic in West Africa.[45][151]

Since the discovery of the viruses in 1976 when outbreaks occurred in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (then called Zaire), Ebola virus disease has been confined to areas in Central Africa, where it is endemic. With the current outbreak, it was initially thought that a new species endemic to Guinea might be the cause, rather than being imported from central to West Africa.[39] However, further studies have shown that the current outbreak is likely caused by an Ebola virus lineage that has spread from Central Africa into West Africa, with the first viral transfer to humans in Guinea.[45][152]

In a study done by Tulane University, the Broad Institute and Harvard University, in partnership with the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation, researchers may have provided information about the origin and transmission of the Ebola virus that sets this outbreak apart from previous outbreaks. For this study, 99 Ebola virus genomes were collected and sequenced from 78 patients diagnosed with the Ebola virus during the first 24 days of the outbreak in Sierra Leone. From the resulting sequences, and three previously published sequences from Guinea, the team found 341 genetic changes that make the outbreak distinct from previous outbreaks. It is still unclear whether these differences are related to the severity of the current situation.[45] Five members of the research team became ill and died from Ebola before the study was published in August.[45]

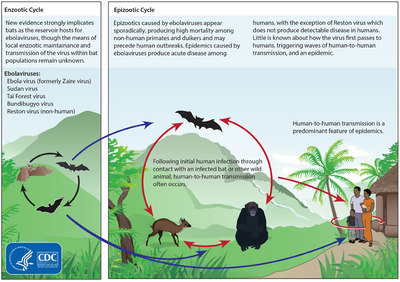

Transmission

It is not entirely clear how an Ebola outbreak starts.[153] The initial infection is believed to occur after an Ebola virus is transmitted to a human by contact with an infected animal's body fluids. Evidence strongly implicates bats as the reservoir hosts for ebolaviruses. Bats drop partially eaten fruits and pulp, then land mammals such as gorillas and duikers feed on these fallen fruits. This chain of events forms a possible indirect means of transmission from the natural host to animal populations.[154]

Human-to-human transmission occurs only via direct contact with blood or bodily fluids from an infected person who is showing signs of infection or by contact with objects recently contaminated by an actively ill infected person.[155] Airborne transmission has not been documented during Ebola outbreaks. The time interval from infection with the virus to onset of symptoms is two to twenty-one days. Because dead bodies are still infectious, the handling of the bodies of Ebola victims can only be done while observing proper barrier/ separation procedures.[156] Semen and possibly other body fluids (e.g., breast milk) may be infectious in survivors for months.[157][158]

One of the primary reasons for spread is the poorly-functioning health systems in the part of Africa where the disease occurs.[159] The risk of transmission is increased among those caring for people infected. Recommended measures when caring for those who are infected include medical isolation via the proper use of boots, gowns, gloves, masks and goggles, and sterilizing equipment and surfaces.[153] However, even with proper isolation equipment available, working conditions such as no running water, no climate control, and no floors may continue to make direct care more difficult. Two American health workers who had contracted the disease and later recovered said that to the best of their knowledge their team of workers had been following "to the letter all of the protocols for safety that were developed by the CDC and WHO", including a full body coverall, several layers of gloves, and face protection including goggles. One of the two, a physician, had worked with patients, but the other was assisting workers to get in and out of their protective gear, while wearing protective gear herself.[160]

Successfully addressing one of the "biggest danger(s) of infection" faced by medical staff requires their learning how to properly suit up with, and later remove, personal protective equipment. In Sierra Leone, the typical training period for the use of such safety equipment lasts approximately 12 days.[161]

Difficulties in attempting to contain the outbreak include its multiple locations across country borders.[162] Dr Peter Piot, the scientist who co-discovered the Ebola virus, has stated that the present outbreak is not following its usual linear patterns as mapped out in previous outbreaks. This time the virus is "hopping" all over the West African epidemic region.[59] Furthermore, past epidemics have occurred in remote regions, but this outbreak has spread to large urban areas, which has increased the number of contacts an infected person may have and has made transmission harder to track and break.[29]

Prevention

Contact tracing

Contact tracing is an essential method of preventing the spread of the disease. It involves finding everyone who has had close contact with an Ebola case and tracking them for 21 days. However, this requires careful record-keeping by properly trained and equipped staff.[163] WHO Assistant Director-General for Global Health Security, Keiji Fukuda, said on 3 September, "We don't have enough health workers, doctors, nurses, drivers, and contact tracers to handle the increasing number of cases."[164] There is a massive ongoing effort to train volunteers and health workers. According to reports, 20,419 people from Sierra Leone and 18,699 from Liberia are listed and being traced as of 17 October. Figures for Guinea are not known.[165][166]

Travel restrictions

On 8 August, a cordon sanitaire, a disease-fighting practice that forcibly isolates affected regions, was established in the triangular area where Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone are separated only by porous borders and where 70 percent of the known cases had been found. (The cordon sanitaire, a common disease-fighting tactic in the 14th-century Black Death that is considered inhumane today, had apparently not been used in the world since 1918.)[167] By September, the closure of borders had caused a collapse of cross-border trade and was having a devastating effect on the economies of the involved countries. A United Nations spokesperson reported that the price of some food staples had increased by as much as 150% and warned that if they continue to rise widespread food shortages can be expected.[citation needed]

On 2 September, WHO Director-General Margaret Chan advised against travel restrictions, saying that they are not justified and that they are preventing medical experts from entering the affected areas and are "marginalizing the affected population and potentially worsening [the crisis]". UN officials working on the ground have also criticized the travel restrictions, saying the solution is "not in travel restrictions but in ensuring that effective preventive and curative health measures are put in place".[28] MSF, also speaking out against the closure of international borders, called it "another layer of collective irresponsibility" and added, "The international community must ensure that those who try to contain the outbreak can enter and leave the affected countries if need be. A functional system of medical evacuation has to be set up urgently."[32]

Despite this advice from WHO and UN, a large number of countries - among them Rwanda, Senegal, Ivory Coast, Chad, South Africa, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Kenya, Colombia, Panama, Australia, Canada and the United States - have either banned or restricted travel for people travelling from countries in West Africa afflicted by Ebola.[168][169][170][171] North Korea has banned all foreign tourists from its country in response to the Ebola epidemic.[172]

Quarantines

The United Nations is concerned about travel restrictions placed on medical workers returning from West Africa and has issued a statement disapproving of the excessive quarantine of medical personnel.[173] The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends monitoring of exposed people for 21 days but doesn't require quarantine, in which they are kept away from others, however some states in the United States have placed health care workers and others under mandatory 21-day quarantine.[174] On 7 October, the governor of Connecticut signed an order authorizing the mandatory quarantine for 21 days of anyone, even if asymptomatic, who had direct contact with Ebola patients.[175][176] On 24 October, the governor of New York, Andrew Cuomo, and the governor of New Jersey, Chris Christie, issued similar quarantine authorizations following an Ebola case reported in New York City. It affects people, in particular health care workers, entering the United States through JFK and Newark airports in New York and New Jersey respectively. Governor Christie said at a news conference with Governor Cuomo that "we are no longer relying on C.D.C. standards."[177] White House spokesmen and National Institute of Health expert Anthony Fauci have both urged against these mandatory quarantines, warning that they would further discourage American healthcare workers from traveling to affected areas.[178]

The first health care worker to be quarantined, Kaci Hickox, a nurse from Maine who was returning after working with Doctors Without Borders, was placed in mandatory quarantine in a tent outside of a Newark hospital in accordance with the new policy measures.[179] Under threat of legal action, Hickox was allowed to return to her home in northern Maine on 27 October, where she remains under mandatory quarantine.[180] Speaking on 29 October, US President Barack Obama said that "subjecting returning health-care workers to lengthy quarantines is motivated by fear, not science, and will be counterproductive because it will dissuade people from joining the fight against the disease in West Africa."[181]

Community

In order to reduce the spread, the World Health Organization recommends raising community awareness of the risk factors for Ebola infection and the protective measures individuals can take.[182] These include avoiding contact with infected people and regular hand washing using soap and water.[183] A condition of extreme poverty exists in many of the areas that have experienced a high incidence of infections. According to the director of the NGO Plan International in Guinea, "The poor living conditions and lack of water and sanitation in most districts of Conakry pose a serious risk that the epidemic escalates into a crisis. People do not think to wash their hands when they do not have enough water to drink."[184]

Containment efforts have been hindered because there is reluctance among residents of rural areas to recognize the danger of infection related to person-to-person spread of disease, such as burial practices which include washing of the body of one who has died.[25][26][27][49] A 2014 study found that nearly two thirds of cases of Ebola in Guinea are believed to be due to burial practices.[185]

Denial in some affected countries has also made containment efforts difficult.[186] Language barriers and the appearance of medical teams in protective suits has sometimes increased fears of the virus.[187] There are reports that some people believe that the disease is caused by sorcery and that doctors are killing patients.[188] In late July, the former Liberian health minister, Peter Coleman, stated that "people don't seem to believe anything the government now says."[67]

Acting on a rumor that the virus was invented to conceal "cannibalistic rituals" (due to medical workers preventing families from viewing the dead), demonstrations were staged outside of the main hospital treating Ebola patients in Kenema, Sierra Leone. The demonstrations were broken up by the police and resulted in the need to use armed guards at the hospital.[189] In Liberia, a mob attacked an Ebola isolation centre, stealing equipment and "freeing" patients while shouting, "There's no Ebola."[190] Red Cross staff were forced to suspend operations in southeast Guinea after they were threatened by a group of men armed with knives.[191] On 18 September in the town of Womey in Guinea, suspicious inhabitants wielding machetes murdered at least eight aid workers and dumped their bodies in a latrine.[192]

Treatment

No proven Ebola virus-specific treatment presently exists,[193] however there are measures that can be taken that will improve a patient's chances of survival.[194] Ebola symptoms may begin as early as two days or as long as 21 days after one is exposed to the virus. They usually begin with a sudden influenza-like stage characterized by feeling tired, fever, and pain in the muscles and joints. Later symptoms may include headache, nausea, and abdominal pain.[195] This is often followed by severe vomiting and diarrhoea.[195] Without fluid replacement, such extreme loss of fluids leads to dehydration which may lead to hypovolaemic shock, a condition which occurs when there isn't enough blood for the heart to pump through the body. If a patient is alert and is not vomiting, oral rehydration fluids may be given, but patients who are vomiting or are delirious must be treated with intravenous fluids. As the disease progresses, some severely ill patients may also experience the loss of blood through bleeding internally and/or externally. Severe blood loss must be treated with the administration of blood products.

Prognosis

Ebola virus disease has a high risk of death in those infected which varies between 25 percent and 90 percent of those who have contracted the disease. The case fatality rate (CFR), the average risk of death among those infected, in previous Ebola infections is 50%.[196] The CDC has reported a CFR for the current epidemic of about 71%.[9] The disease affects males and females equally and the majority of those that contract Ebola disease are between 15 and 45 years of age.[10] Only rarely do pregnant women survive. A midwife who works with MSF in a Sierra Leone treatment center states that she knew of "no reported cases of pregnant mothers and unborn babies surviving Ebola in Sierra Leone."[197]

It has been suggested that the loss of human life is not limited to Ebola victims alone. Many hospitals have shut down leaving people with medical needs other than treatment for Ebola without care. A spokesperson for the UK-based health foundation the Wellcome Trust said in October that "the additional death toll from malaria and other diseases [is] likely to exceed that of the outbreak itself".[30] Doctor Paul Farmer states "Most of Ebola's victims may well be dying from other causes: women in childbirth, children from diarrhoea, people in road accidents or from trauma of other sorts." [198]

Level of care

Local authorities have not had resources to contain the disease, with health centres closing and hospitals overwhelmed.[199] In late June, the Director-General of MSF said, "Countries affected to date simply do not have the capacity to manage an outbreak of this size and complexity on their own. I urge the international community to provide this support on the most urgent basis possible."[162] Adequate equipment has not been provided for medical personnel,[200] with even a lack of soap and water for hand-washing and disinfection.[201]

In late August, MSF called the situation "chaotic" and the medical response "inadequate". They reported that they had expanded their operations but were unable to keep up with the rapidly increasing need for assistance which had forced them to reduce the level of care they were able to offer: "It is not currently possible, for example, to administer intravenous treatments." Calling the situation "an emergency within the emergency", MSF reported that many hospitals have had to shut down due to lack of staff or fears of the virus among patients and staff, which has left people with other health problems without any care at all. Speaking from a remote region, a MSF worker said that a shortage of protective equipment was making the medical management of the disease difficult and that they had limited capacity to safely bury bodies.[202]

By September, treatment for Ebola patients had become unavailable in some areas. Speaking on 12 September, WHO Director-General Margaret Chan said, "In the three hardest hit countries, Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, the number of new cases is moving far faster than the capacity to manage them in the Ebola-specific treatment centers. Today, there is not one single bed available for the treatment of an Ebola patient in the entire country of Liberia."[203] According to a WHO report released on 19 September, Sierra Leone is currently meeting only 25% of its need for patient beds, and Liberia is meeting only 20% of its need.[204]

| Countries | Existing beds | Planned beds | Percentage of existing/Planned beds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guinea | 160 | 260 | 61% |

| Liberia | 620 | 2,690 | 23% |

| Sierra Leone | 346 | 1,198 | 29% |

| Total | 1,126 | 4,148 | 27% |

Healthcare settings

A number of Ebola Treatment Centres have been set up in the area, supported by international aid organisations and staffed by a combination of local and international staff. Each treatment centre is divided into a number of distinct and rigorously separate areas. For patients, there is a triage area, and low- and high-risk care wards. For staff, there are areas for preparation and decontamination. An important part of each centre is an arrangement for safe burial or cremation of bodies, required to prevent further infection.[205][206]

Although the WHO does not advise caring for Ebola patients at home, it is an option and even a necessity when no hospital treatment beds are available. For those being treated at home, the WHO advises informing the local public health authority and acquiring appropriate training and equipment.[207][208] UNICEF, USAID and the NGO Samaritan's Purse have begun to take measures to provide support for families that are forced to care for patients at home by supplying caregiver kits intended for interim home-based interventions. The kits include protective clothing, hydration items, medicines, and disinfectant, among other items.[209][210] Even where hospital beds are available, it has been debated whether conventional hospitals are the best place to care for Ebola patients, as the risk of spreading the infection is high.[211] The WHO and non-profit partners have launched a program in Liberia to move infected people out of their homes into ad hoc centres that will provide rudimentary care.[212]

Protective clothing

The Ebola epidemic has caused an increasing demand in protective clothing. It is assumed that a health worker uses seven suits per bed per day. A full set of protective clothing includes a suit, goggles, mask, socks and boots, and an apron. Boots and aprons can be disinfected and reused, but everything else must be destroyed. Health workers change garments frequently, discarding gear that has barely been used. This not only uses a great deal of time but also exposes them to the virus because for health care workers wearing protective clothing, one of the most dangerous times for catching Ebola is while suits are being removed.[213] The protective clothing set that MSF uses cost about $75 apiece. Staff who have returned from deployments to West Africa say the clothing is so heavy that it can be worn for only about 40 minutes at a stretch. A physician working in Sierra Leone has said, "After about 30 or 40 minutes, your goggles have fogged up; your socks are completely drenched in sweat. You're just walking in water in your boots. And at that point, you have to exit for your own safety...Here it takes 20-25 minutes to take off a protective suit and must be done with two trained supervisors who watch every step in a military manner to ensure no mistakes are made, because a slip up can easily occur and of course can be fatal." [214][215] According to some reports, protective outfits are beginning to be in short supply and manufacturers have started to increase their production,[216] but the need to find better types of suits has also been raised.[217]

USAID published an open competitive bidding for proposals that address the challenge of developing "... new practical and cost-effective solutions to improve infection treatment and control that can be rapidly deployed (1) to help health care workers provide better care and (2) transform our ability to combat Ebola".[218]

Deaths of healthcare workers

In August, it was reported that healthcare workers represented nearly 10 percent of the cases and fatalities, significantly impairing the ability to respond to the outbreak in an area which already faces a severe shortage of doctors.[219] In the hardest hit areas there have historically been only one or two doctors available to treat 100,000 people, and these doctors are heavily concentrated in urban areas.[29] Healthcare providers caring for people with Ebola, and family and friends in close contact with people with Ebola, are at the highest risk of getting infected because they may come in direct contact with the blood or body fluids of the sick person. In some places affected by the current outbreak, care may be provided in clinics with limited resources, and workers could be in these areas for several hours with a number of Ebola infected patients.[9] According to the WHO, the high proportion of infected medical staff can be explained by a lack of the number of medical staff needed to manage such a large outbreak, shortages of protective equipment or improperly using what is available, and "the compassion that causes medical staff to work in isolation wards far beyond the number of hours recommended as safe".[29]

Among the fatalities is Samuel Brisbane, a former advisor to the Liberian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, described as "one of Liberia's most high-profile doctors".[220] In July, leading Ebola doctor Sheik Umar Khan from Sierra Leone died in the outbreak. His death was followed by two more deaths in Sierra Leone: Modupe Cole, a senior physician at the country's main referral facility,[221] and Sahr Rogers, who worked in Kenema.[222][223][224] In August, a well-known Nigerian physician, Ameyo Adadevoh, died. She was posthumously praised for preventing the Nigerian index case from leaving the hospital at the time of diagnosis, thereby playing a key role in curbing the spread of the virus in Nigeria.[127]

By 27 October, the WHO reported 521 workers had been infected and 272 had died. Liberia has been especially hard hit with almost half the total cases (299 with 123 deaths) reported. Sierra Leone registered 127 cases with 101 fatalities, thus indicating a death toll of 79.5% in Sierra Leone. Guinea reported 80 infected cases with 43 deaths. In Nigeria 11 healthcare workers were also infected and 5 deaths were recorded.[2] One infected case in Spain was reported, as well as two in the United States.[110][225]

Experimental treatments

There is as yet no known effective medication or vaccine. The director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has stated that the scientific community is still in the early stages of understanding how infection with the Ebola virus can be treated and prevented.[226] The unavailability of treatments in the most-affected regions has spurred controversy, with some calling for experimental drugs to be made more widely available in Africa on a humanitarian basis, and others warning that making unproven drugs widely available would be unethical, especially in light of past experimentation conducted in developing countries by Western drug companies.[227][228] As a result of the controversy, on 12 August an expert panel of the WHO endorsed the use of interventions with as-yet-unknown effects for both treatment and prevention of Ebola, and also said that deciding which treatments should be used and how to distribute them equitably were matters that needed further discussion.[229]

A number of experimental treatments are being considered for use in the context of this outbreak, and are currently or will soon undergo clinical trials,[230] but it will still be some time before sufficient quantities have been produced for widespread trials.[226]

- Serum Transfusion - Identified as a promising method since the early 1970s days of Ebola research,[231] the WHO has recognised that transfusion of whole blood or purified serum from Ebola survivors is the therapy with the greatest potential to be implemented in the short term, although there is little information on its efficacy.[232] On 21 October Dr Marie Paule Kieny, WHO assistant director general for health system and innovation, announced the development of partnerships in the three countries which would be able to safely extract plasma for treatment of infected patients. The first of these is likely to become operational in Liberia during November.[233]

- ZMapp, a combination of monoclonal antibodies. The limited supply of the drug has been used to treat 7 individuals infected with the Ebola virus.[234] Although some of them have recovered, the outcome is not considered to be statistically significant.[235] ZMapp has proved highly effective in a trial involving rhesus macaque monkeys.[236] Texas A&M University stated on 8 October that it was preparing to mass-produce the drug, in its Center for Innovation in Advanced Development and Manufacturing, pending final approval.[237]

- TKM-Ebola, an RNA interference drug.[238] A Phase 1 clinical trial involving healthy volunteers was started in early 2014 but suspended because of concern over side effects; however the FDA has approved emergency use to treat patients actually infected with the virus.[239][240]

- Favipiravir (Avigan), a drug approved in Japan for stockpiling against influenza pandemics. The drug appears to be useful in a mouse model of the disease[241][242] and a clinical trial is being planned for Ebola patients in Guinea, due November.[243]

- BCX4430 is a broad-spectrum antiviral drug developed by BioCryst Pharmaceuticals and currently being researched as a potential treatment for Ebola by USAMRIID.[244] The drug has been approved to progress to Phase 1 trials, expected late in 2014.[245]

- Brincidofovir, another antiviral drug, has been granted an emergency FDA approval as an investigational new drug for the treatment of Ebola after it was found to be effective against Ebola virus in in vitro tests.[246] On 16 October, it was cleared to start clinical trials.[247]

- JK-05 is an antiviral drug developed by the Chinese company Sihuan Pharmaceutical along with the Chinese Academy of Military Medical Sciences. In tests on mice, JK-05 shows efficacy against a range of viruses, including Ebola. It is claimed to have a simple molecular structure, which should be readily amenable to synthesis scale-up for mass production. The drug has been given preliminary approval by the Chinese authorities to be available for Chinese health workers involved in combating the outbreak, and Sihuan are preparing to conduct clinical trials in West Africa.[248][249]

Experimental preventative vaccines

- In September, an experimental vaccine, now known as the cAd3-ZEBOV vaccine, commenced simultaneous Phase 1 trials, being administered to volunteers in Oxford and Bethesda. The vaccine was developed jointly by GlaxoSmithKline and the NIH. During October the vaccine is being administered to a further group of volunteers in Mali. If these trials are completed successfully, the vaccine will be fast tracked for use in West Africa. In preparation for this, GSK is preparing a stockpile of 10,000 doses.[250][251]

- A second vaccine candidate, rVSV-ZEBOV, has been developed by the Public Health Agency of Canada. On 29 October, the Wellcome Trust announced that multiple trials are to begin swiftly in healthy volunteers in Europe, Gabon, Kenya, and the USA. This is the latest of several international commitments to fast-track early tests of candidate Ebola vaccines so they could be available for trial in West Africa by the end of the year, and if successful deployed more widely in 2015.[252]

- A third vaccine candidate, consisting of a prime-boost regimen of an adenovirus vaccine component from Crucell (Johnson & Johnson) and a modified vaccinia Ankara component from Bavarian Nordic is being prepared for clinical trials in early 2015.[253] Johnson & Johnson have announced their commitment to accelerate the development of the vaccine and will produce more than 1 million doses of the vaccine during 2015.[254]

Outlook

Since the beginning of the outbreak, there has been considerable difficulty in getting reliable estimates both of the number of people affected, and of the geographical extent of the outbreak.[255] The three countries which are most affected, Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia, are among the poorest in the world, with extremely low levels of literacy, few hospitals or doctors, poor physical infrastructure, and poorly functioning government institutions.[256] One effect of the epidemic has been to weaken the institutions which already exist as healthcare and government workers become overwhelmed by the workload, in some cases abandoning their posts, or succumb to infection. Since the symptoms of EVD resemble other diseases such as malaria which are common in the area, even diagnosis is uncertain unless a blood sample can reach one of the few testing centres which are equipped to perform PCR or ELISA tests. WHO, MSF and the CDC have warned that the official counts of EVD cases and deaths are not consistent with field observations, and are likely to understate the extent of the epidemic.[3][14][257]

Statistical measures

Calculating an accurate case fatality rate (CFR) is difficult for an ongoing epidemic due to differences in testing policies, the inclusion of probable and suspected cases, and the inclusion of new cases that have not run their course. In late August, the WHO made an initial CFR estimate of 53% though this included suspected cases.[258][259] On 23 September, the WHO released a revised and more accurate CFR of 70.8% (with 95% confidence intervals of 68.6%-72.8%), derived using data from patients with definitive clinical outcomes.[10]

The basic reproduction number (R0) is a statistical measure of the number of people who are expected to be infected by one person who has the disease in question. If the rate is less than 1, the infection will die out in the long run; if the rate is greater than 1, the infection will continue to spread in a population.[260] The BRN of the current outbreak is estimated to be between 1.71 and 2.02.[10]

Projections of future cases

On 28 August, the WHO released its first estimate of the possible total cases (20,000) from the outbreak as part of its roadmap for stopping the transmission of the virus.[261] The WHO roadmap states "[t]his Roadmap assumes that in many areas of intense transmission the actual number of cases may be two- to fourfold higher than that currently reported. It acknowledges that the aggregate case load of EVD could exceed 20,000 over the course of this emergency. The Roadmap assumes that a rapid escalation of the complementary strategies in intense transmission, resource-constrained areas will allow the comprehensive application of more standard containment strategies within three months."[261] It includes an assumption that some country or countries will pay the required cost of their plan, estimated at half a billion dollars.[261]

When the WHO released its first estimated projected number of cases, a number of epidemiologists presented data to show that the WHO's projection of a total of 20,000 cases was likely an underestimate. On 31 August, the journal Science quoted Christian Althaus, a mathematical epidemiologist at the University of Bern in Switzerland, as saying that if the epidemic were to continue in this way until December, the cumulative number of cases would exceed 100,000 in Liberia alone.[262] According to a research paper released in early September, in the hypothetical worst-case scenario, if a BRN of over 1.0 continues for the remainder of the year we would expect to observe a total of 77,181 to 277,124 additional cases within 2014. The researchers believe this is unlikely but say that Ebola "must be regarded as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern".[263] On 9 September, Jonas Schmidt-Chanasit of the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine in Germany, controversially announced that the containment fight in Sierra Leone and Liberia has already been "lost" and that the disease would "burn itself out".[264] Writing in The New York Times on 12 September, Bryan Lewis, an epidemiologist at the Virginia Bioinformatics Institute at Virginia Tech, said that researchers at various universities who have been using computer models to track the growth rate say that at the virus's present rate of growth, there could easily be close to 20,000 cases in one month, not in nine.[265]

On 8 September, the WHO warned that the number of new cases in Liberia was increasing exponentially, and would increase by "many thousands" in the following three weeks. In a 23 September WHO report, the WHO revised their previous projection, stating that they expect the number of Ebola cases in West Africa to be in excess of 20,000 by 2 November.[10] They further stated, that if the disease is not adequately contained it could become endemic in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, "spreading as routinely as malaria or the flu",[266] and according to an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, eventually to other parts of Africa and beyond.[267]

In a 23 September CDC report, a projection calculates a potential underreporting which is corrected by a factor of 2.5. With this correction factor, approximately 21,000 total cases are the estimate for the end of September 2014 in Liberia and Sierra Leone alone. The same report predicted that total cases, including unreported cases, could reach 1.4 million in Liberia and Sierra Leone by 20 January 2015 if no improvement in intervention or community behaviour occurred.[3]

On 2 September, an assessment of the probability of Ebola virus disease case importation in countries across the world was published in PLOS Currents Outbreaks.[268] The projections are based on simulations of epidemic spread worldwide. The analysis was updated with simulations based on new data on 6 October, and the updated results are available online.[269] On 14 October, during a news conference in Geneva, the assistant director-general of the WHO stated that there could be as many as 10,000 new Ebola cases per week by December 2014.[21]

A third of all Ebola cases ever documented were diagnosed by September 2014. The WHO Ebola Response team reported that the doubling times of the outbreak were 15.7 days in Guinea, 23.6 days in Liberia and 30.2 days in Sierra Leone.[10]

Economic effects

In addition to the loss of life, the outbreak is having a number of significant economic impacts.

- Markets and shops are closing, due to travel restrictions, a cordon sanitaire, or fear of human contact, which leads to loss of income for producers and traders.[270]

- Movement of people away from affected areas has disturbed agricultural activities.[271][272] The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) has warned that the outbreak could endanger harvest and food security in West Africa.[273]

- Tourism is directly impacted in affected countries.[274] Other countries in Africa which are not directly affected by the virus have also reported adverse effects on tourism.[275]

- Many airlines have suspended flights to the area.[276]

- Foreign mining companies have withdrawn non-essential personnel, deferred new investment, and cut back operations.[272][277][278]

- The outbreak is straining the finances of governments, with Sierra Leone using Treasury bills to fund the fight against the virus.[279]

- The IMF is considering expanding assistance to Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia as their national deficits are ballooning and their economies contract sharply.[280]

- On 8 October, the World Bank issued a report which estimated overall economic impacts of between $3.8 billion and $32.6 billion, depending on the extent of the outbreak and the speed with which it can be contained. The economic impact would be felt most severely in the three affected countries, with a wider impact felt across the broader West African region.[281][282]

Responses

In July, the World Health Organization, a United Nations agency which coordinates international response to disease outbreaks, convened an emergency meeting with health ministers from eleven countries and announced collaboration on a strategy to co-ordinate technical support to combat the epidemic. In August they published a roadmap to guide and coordinate the international response to the outbreak, aiming to stop ongoing Ebola transmission worldwide within 6–9 months, and formally designated the outbreak as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.[283] This is a legal designation used only twice before (for the 2009 H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic and the 2014 resurgence of polio) which invokes legal measures on disease prevention, surveillance, control, and response, by 194 signatory countries.[20][284] There has been heavy criticism of the WHO from some aid agencies because its response has been perceived as slow and insufficient, especially during the early stage of the outbreak.[285] In October, the Associated Press reported that in a leaked preliminary draft report the WHO admitted to mistakes saying that they had missed chances to stop the spread of Ebola "thanks to incompetent staff, a lack of information, and bureaucracy due to 'politically motivated appointments'." Peter Piot, co-discoverer of the Ebola virus, has called the WHO staff "really not competent.”[286]

In September, the United Nations Security Council declared the Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa "a threat to international peace and security" and unanimously adopted a resolution urging UN member states to provide more resources to fight the outbreak; the WHO stated that the cost for combating the epidemic will be a minimum of $1 billion.[287][288]

During October, WHO and UNMEER announced a comprehensive 90-day plan to control and reverse the epidemic of EVD. The immediate objective is to isolate at least 70% of EVD cases and safely bury at least 70% of patients who die from EVD by 1 December 2014 (the 60-day target) - this has become known as the 70:70:60 program. The ultimate goal is to have capacity in place for the isolation of 100% of EVD cases and the safe burial of 100% of casualties by 1 January 2015 (the 90-day target).[289] Many nations and charitable organizations are cooperating to realise this plan.[290]

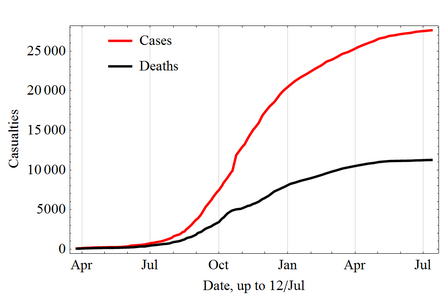

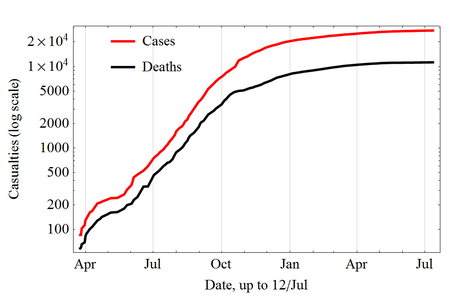

Timeline of cases and deaths

Data comes from reports by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention[291] and the WHO.[292] All numbers are correlated with United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) if available.[293] The table includes suspected cases that have not yet been confirmed. The reports are sourced from official information from the affected countries' health ministries. The WHO has stated the reported numbers "vastly underestimate the magnitude of the outbreak", estimating there may be 3 times as many cases as officially reported.[3][19][20] Liberia was singled out in the 8 and 14 October reports from WHO, noting "There continue to be profound problems affecting data acquisition in Liberia... it is likely that the figures will be revised upwards in due course."[14]

The case numbers reported may include probable or suspected cases. Numbers are revised downward if a case is later found to be negative. (Numbers may differ from reports as per respective Government reports. See notes at the bottom for stated source file.)

-

Cumulative totals of cases and deaths over time

-

Cumulative totals in log scale

-

Average new cases and deaths per day (between WHO reporting dates) [original research?]

-

The reported weekly cases of Ebola in West Africa as listed on Wikipedia Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa; some values are interpolated

-

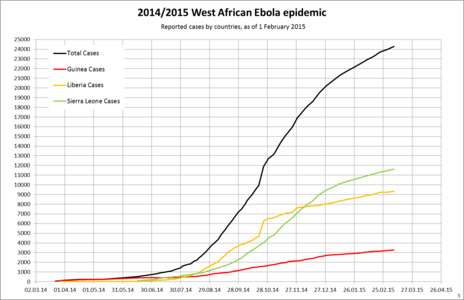

Cumulative number of cases by country, using a linear scale

-

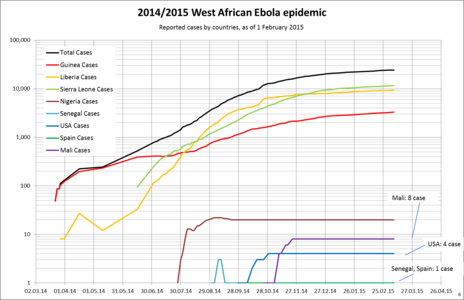

Cumulative number of cases by country, using a logarithmic scale

-

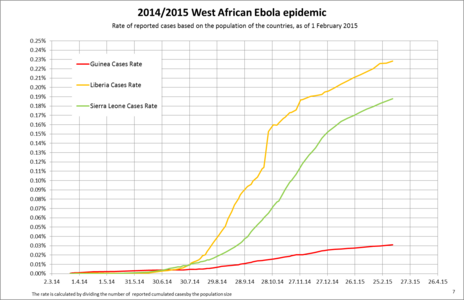

Cases based on population, using a linear scale

-

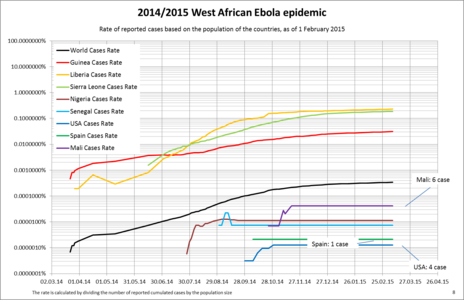

Cases based on population, using a logarithmic scale

| Date | Total | Guinea | Liberia | Sierra Leone | Refs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Deaths | Cases | Deaths | Cases | Deaths | Cases | Deaths | ||

| 27 Oct 2014 | 13,703 | ≥4,922 | 1,906 | 997 | 6,535 | ≥2,413 | 5,235 | 1,500 | [note 1][2] |

| 24 Oct 2014 | 12,008 | 5,078 | 1,598 | 981 | 6,253 | ≥2,704 | 4,017 | 1,341 | [note 2][85][294][295] |

| 19 Oct 2014 | 9,936 | 4,877 | 1,540 | 926 | ≥4,665 | ≥2,705 | 3,706 | 1,259 | [note 3][18] |

| 17 Oct 2014 | 9,693 | 4,811 | 1,501 | 886 | ≥4,607 | ≥2,689 | 3,560 | 1,227 | [note 4][6][165][166][296] |

| 12 Oct 2014 | 8,997 | 4,493 | 1,472 | 843 | ≥4,249 | ≥2,458 | 3,252 | 1,183 | [note 5][225] |

| 7 Oct 2014 | 8,386 | 3,988 | 1,350 | 778 | ≥4,076 | ≥2,316 | 2,937 | 885 | [note 6][297][298] |

| 5 Oct 2014 | 8,033 | 3,865 | 1,298 | 768 | ≥3,924 | ≥2,210 | 2,789 | ≥879 | ✓[note 7][14][297] |

| 1 Oct 2014 | 7,492 | 3,439 | 1,199 | 739 | ≥3,834 | ≥2,069 | 2,437 | 623 | ✓[note 8][299] |

| 28 Sep 2014 | 7,192 | 3,286 | 1,157 | 710 | ≥3,696 | ≥1,998 | 2,317 | 570 | ✓[note 9] [300][301][302] |

| 25 Sep 2014 | 6,808 | 3,159 | 1,103 | 668 | ≥3,564 | ≥1,922 | 2,120 | 561 | ✓[note 10] [303][304][305] |

| 23 Sep 2014 | 6,574 | 3,043 | 1,074 | 648 | ≥3,458 | ≥1,830 | 2,021 | 557 | ✓[note 11][306][307] |

| 21 Sep 2014 | 6,263 | 2,900 | 1,022 | 635 | ≥3,280 | ≥1,707 | 1,940 | 550 | ✓[note 12][308][309] |

| 17 Sep 2014 | 5,762 | 2,746 | 965 | 623 | ≥3,022 | ≥1,578 | 1,753 | 537 | ✓[note 13][310][311][312] |

| 14 Sep 2014 | 5,339 | 2,586 | 942 | 601 | ≥2,720 | ≥1,461 | 1,655 | 516 | ✓[note 14][313][314][315] |

| 10 Sep 2014 | 4,848 | 2,376 | 899 | 568 | 2,415 | 1,307 | 1,509 | 493 | ✓[note 15][316][317] |

| 7 Sep 2014 | 4,391 | 2,177 | 861 | 557 | 2,081 | 1,137 | 1,424 | 476 | ✓ [note 16][318][319] |

| 3 Sep 2014 | 4,001 | 2,059 | 823 | 522 | 1,863 | 1,078 | 1,292 | 452 | ✓[320] |

| 31 Aug 2014 | 3,707 | 1,808 | 771 | 494 | 1,698 | 871 | 1,216 | 436 | ✓[note 17] [259][321] |

| 25 Aug 2014 | 3,071 | 1,553 | 648 | 430 | 1,378 | 694 | 1,026 | 422 | ✓[322] |

| Date | Nigeria | Senegal | United States | Spain | Mali | Refs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Deaths | Cases | Deaths | Cases | Deaths | Cases | Deaths | Cases | Deaths | ||

| 27 Oct 2014 | 20 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | [2] |

| 23 Oct 2014 | 20 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | [18] |

| 19 Oct 2014 | 20 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | - | - | [18] |

| 12 Oct 2014 | 20 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 7 Oct 2014 | 20 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 5 Oct 2014 | 20 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 1 Oct 2014 | 20 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| 28 Sep 2014 | 20 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| 25 Sep 2014 | 20 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| 23 Sep 2014 | 20 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| 21 Sep 2014 | 20 | 8 | 1 | 0 | |||||||

| 17 Sep 2014 | 20 | 8 | 1 | 0 | |||||||

| 14 Sep 2014 | 21 | 8 | 1 | 0 | |||||||

| 10 Sep 2014 | 21 | 8 | 1 | 0 | |||||||

| 7 Sep 2014 | 22 | 8 | 3 | 0 | |||||||

| 3 Sep 2014 | 22 | 7 | 3 | 0 | |||||||

| 31 Aug 2014 | 22 | 7 | 1 | 0 | |||||||

| 25 Aug 2014 | 21 | 7 | 1 | 0 | |||||||

| Date | Total | Guinea | Liberia | Sierra Leone | Nigeria | Refs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Deaths | Cases | Deaths | Cases | Deaths | Cases | Deaths | Cases | Deaths | ||

| 20 Aug 2014 | 2,615 | 1,427 | 607 | 406 | 1,082 | 624 | 910 | 392 | 16 | 5 | ✓[19] |

| 18 Aug 2014 | 2,473 | 1,350 | 579 | 396 | 972 | 576 | 907 | 374 | 15 | 4 | ✓[323] |

| 16 Aug 2014 | 2,240 | 1,229 | 543 | 394 | 834 | 466 | 848 | 365 | 15 | 4 | ✓[324] |

| 13 Aug 2014 | 2,127 | 1,145 | 519 | 380 | 786 | 413 | 810 | 348 | 12 | 4 | ✓[325] |

| 11 Aug 2014 | 1,975 | 1,069 | 510 | 377 | 670 | 355 | 783 | 334 | 12 | 3 | ✓[326] |

| 9 Aug 2014 | 1,848 | 1,013 | 506 | 373 | 599 | 323 | 730 | 315 | 13 | 2 | ✓[327] |

| 6 Aug 2014 | 1,779 | 961 | 495 | 367 | 554 | 294 | 717 | 298 | 13 | 2 | ✓[328] |

| 4 Aug 2014 | 1,711 | 932 | 495 | 363 | 516 | 282 | 691 | 286 | 9 | 1 | ✓[329] |

| 1 Aug 2014 | 1,603 | 887 | 485 | 358 | 468 | 255 | 646 | 273 | 4 | 1 | ✓[330] |

| 30 Jul 2014 | 1,440 | 826 | 472 | 346 | 391 | 227 | 574 | 252 | 3 | 1 | ✓[331] |

| 27 Jul 2014 | 1,323 | 729 | 460 | 339 | 329 | 156 | 533 | 233 | 1 | 1 | ✓[332] |

| 23 Jul 2014 | 1,201 | 672 | 427 | 319 | 249 | 129 | 525 | 224 | ✓[51] | ||

| 20 Jul 2014 | 1,093 | 660 | 415 | 314 | 224 | 127 | 454 | 219 | ✓[333] | ||

| 17 Jul 2014 | 1,048 | 632 | 410 | 310 | 196 | 116 | 442 | 206 | ✓[48] | ||

| 14 Jul 2014 | 982 | 613 | 411 | 310 | 174 | 106 | 397 | 197 | ✓[334] | ||

| 12 Jul 2014 | 964 | 603 | 406 | 304 | 172 | 105 | 386 | 194 | ✓[335] | ||

| 8 Jul 2014 | 888 | 539 | 409 | 309 | 142 | 88 | 337 | 142 | ✓[336] | ||

| 6 Jul 2014 | 844 | 518 | 408 | 307 | 131 | 84 | 305 | 127 | ✓[337] | ||

| 2 Jul 2014 | 779 | 481 | 412 | 305 | 115 | 75 | 252 | 101 | ✓[338] | ||

| 30 Jun 2014 | 759 (6/25)+22 |

467 +14 |

413 +3 |

303 +5 |

107 +8 |

65 +7 |

239 +11 |

99 +2 |

✓[339] | ||

| 22 Jun 2014 | 599 | 338 | — | — | 51 | 34 | — | — | ✓[47] | ||

| 20 Jun 2014 | 581 | 328 | 390 +0 |

270 +3 |

— | — | 158 +0 |

34 +4 |

✓[47] | ||

| 17 Jun 2014 | 528 | 337 | — | — | — | — | 97 (6/15)+31 |

49 +4 |

✓[340] | ||

| 16 Jun 2014 | 526 | 334 | 398 | 264 | 33 (6/11)+9 |

24 +5 |

— | — | ✓[340] | ||

| 15 Jun 2014 | 522 | 333 | 394 | 263 | 33 | 24 | 95 | 46 | ✓[341] | ||

| 10 Jun 2014 | 474 | 252 | 372 | 236 | — | — | — | — | CDC[42] | ||

| 6 Jun 2014 | 453 | 245 | — | — | — | — | 89 +8 |

7 +1 |

✓[342] | ||

| 5 Jun 2014 | 445 | 244 | 351 +7 |

226 +6 |

— | — | 81 +9 |

6 | ✓[342][343] | ||

| 3 Jun 2014 | 436 | 233 | 344 +11 |

215 +3 |

— | — | — | — | ✓[343] | ||

| 1 Jun 2014 | 383 | 211 | 328 | 208 +21 |

— | — | 79 +13 |

6 | ✓[344] | ||

| 29 May 2014 | 354 | 211 | — | — | — +1 |

— +1 |

50 +34 |

6 +1 |

✓[345] | ||

| 28 May 2014 | 319 | 209 | 291 | 193 | — | — | — | — | ✓[345] | ||

| 27 May 2014 | 309 | 202 | 281 | 186 | — | — | 16 | 5 | ✓[346][347] | ||

| 23 May 2014 | 270 | 185 | 258 | 174 | — | — | — | — | ✓[348] | ||

| 18 May 2014 | 265 | 187 | 253 | 176 | — | — | — | — | ✓[349] | ||

| 12 May 2014 | 260 | 182 | 248 | 171 | — | — | — | — | ✓[350] | ||

| 10 May 2014 | 245 | 168 | 233 | 157 | 12 | 11 | — | — | ✓[351] | ||

| 7 May 2014 | 249 | 169 | 236 | 158 | — | — | — | — | ✓[352] | ||