Hardcore punk

| Hardcore punk | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Late 1970s, Southern California,[2][3][4][5][6][7] Washington, D.C.,[7] San Francisco,[7][8] Vancouver |

| Typical instruments | |

| Derivative forms | |

| Subgenres | |

| Fusion genres | |

| Regional scenes | |

| |

| Other topics | |

Hardcore punk (often abbreviated to hardcore) is a punk rock music genre that originated in the late 1970s. It is generally faster, harder, and more aggressive than other forms of punk rock.[9] Its roots can be traced to earlier punk scenes in San Francisco and Southern California which arose as a reaction against the still predominant hippie cultural climate of the time and was also inspired by New York punk rock and early proto-punk.[8] New York punk had a harder-edged sound than its San Francisco counterpart, featuring anti-art expressions of masculine anger, energy and subversive humor. Hardcore punk generally disavows commercialism, the established music industry and "anything similar to the characteristics of mainstream rock"[10] and often addresses social and political topics.

Hardcore sprouted underground scenes across the United States in the early 1980s, particularly in Washington, D.C., New York, New Jersey, and Boston—as well as in Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom. Hardcore has spawned the straight edge movement and its associated submovements, hardline and youth crew. Hardcore was heavily involved with the rise of the independent record labels in the 1980s, and with the DIY ethics in underground music scenes. It has also influenced various music genres that have experienced widespread commercial success, including alternative rock, thrash metal, emo, nu metal and metalcore.

While traditional hardcore has never experienced mainstream commercial success, some of its early pioneers have garnered appreciation over time. Black Flag's Damaged, Minutemen's Double Nickels on the Dime and Hüsker Dü's New Day Rising were included in Rolling Stone's list of The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time in 2003 and Dead Kennedys have seen one of their albums reach gold status over a period of 25 years.[11] In 2011, Rolling Stone writer David Fricke placed Greg Ginn of Black Flag 99th place in his 100 Greatest Guitarists list. Although the music genre started in English-speaking western countries, notable hardcore scenes have existed in Italy, Brazil, Japan, Europe and the Middle East.

Origin of term

The origin of the term "hardcore punk" is uncertain. The Vancouver-based band D.O.A. may have helped to popularize the term with the title of their 1981 album, Hardcore '81.[12][13] A September 1981 article by Tim Sommer shows the author applying the term to the "15 or so" punk bands gigging around the city at that time, which he considered a belated development relative to Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Washington D.C.[14] Hardcore historian Steven Blush said that the term "hardcore" is also a reference to the sense of being "fed up" with the existing punk and new wave music.[15] Blush also states that the term refers to "an extreme: the absolute most Punk."[16]

Characteristics

An article in Drowned in Sound argues that 1980s-era "hardcore is the true spirit of punk", because "after all the poseurs and fashionistas fucked off to the next trend of skinny pink ties with New Romantic haircuts, singing wimpy lyrics", the punk scene consisted only of people "completely dedicated to the DIY ethics".[17] One definition of the genre is "a form of exceptionally harsh punk rock."[18] Like the Oi! subgenre of the UK, hardcore punk can be considered an internal music reaction. According to one writer, "distressed by the 'art'ificiality [sic] of much post-punk and the emasculated sellouts of new wave, hardcore sought to strengthen its core punk principles."[2] Lacking the art-school grace of post-punk, hardcore punk "favor[ed] low key visual aesthetic over extravagance and breaking with original punk rock song patterns."[19]

One of the important philosophies in the hardcore scene is authenticity. The pejorative term "poseur" is applied to those who associate with punk and adopt its stylistic attributes but are deemed not to share or understand the underlying values and philosophy. Joe Keithley, the vocalist of D.O.A. said in an interview: "For every person sporting an anarchy symbol without understanding it there’s an older punk who thinks they’re a poseur."[20]

Musical characteristics

In the vein of earlier punk rock, most hardcore punk bands have followed the traditional singer/guitar/bass/drum format. The songwriting has more emphasis on rhythm rather than melody. Critic Steven Blush writes "The Sex Pistols were still rock'n'roll...like the craziest version of Chuck Berry. Hardcore was a radical departure from that. It wasn't verse-chorus rock. It dispelled any notion of what songwriting is supposed to be. It's its own form."[21] According to AllMusic, the overall blueprint for hardcore was playing louder, harder and faster.[22] Hardcore vocalists often shout,[22] scream or chant along with the music. Hardcore vocal lines are often based on minor scales.[23] Hardcore songs may include shouted background vocals from the other band members.

Guitar parts in hardcore can be complex, technically versatile and rhythmically challenging.[24] Guitar melody lines usually use the same minor scales used by vocalists (although some solos use pentatonic scales).[24] Some hardcore punk guitarists play solos, octave leads and grooves, as well as tapping into the various feedback and harmonic noises available to them. The guitar sound is almost always distorted and amplified, creating what has been called a "buzzsaw" sound.[25] Hardcore bassists use varied rhythms in their basslines, ranging from longer held notes (whole notes and half notes) to quarter notes, to rapid eighth note or sixteenth note runs. To play rapid bass lines that would be hard to play with the fingers, some bassists use a pick.[24] Some bassists emphasize a very technical style of bass playing. According to Tobias Hurwitz, '[h]ardcore drumming falls somewhere between the straight-ahead rock styles of old-school punk and the frantic, warp-speed bashing of thrash."[26] Some hardcore punk drummers play fast D beat one moment and then drop tempo into elaborate musical breakdowns the next. Drummers typically play eighth notes on the cymbals, because at the tempos used in hardcore it would be difficult to play a smaller subdivision of the beat.[24]

Politics

Hardcore punk lyrics often express anti-establishment, anti-militarist, anti-authoritarian, anti-violence, and pro-environmentalist sentiments, in addition to other typically left-wing, anarchist, or egalitarian political views. During the 1980s, the subculture often rejected what was perceived to be "yuppie" materialism and interventionist American foreign policy.[27] Numerous hardcore punk bands have taken far left political stances such as anarchism or other varieties of socialism and in the 1980s expressed opposition to political leaders such as then US president Ronald Reagan and British prime minister Margaret Thatcher. Reagan's economic policies, sometimes dubbed "Reaganomics", and social conservatism were common subjects for criticism by hardcore bands of the time.[28][29] Jimmy Gestapo of Murphy's Law, however, endorsed Reagan and even went as far to call then former-president Jimmy Carter a "pussy" in a 1986 New York Magazine cover story.[30] Shortly after Reagan's death in 2004, the Maximumrocknroll radio show aired an episode composed of anti-Reagan songs by early hardcore punk bands.[31]

Certain hardcore punk bands have conveyed messages sometimes deemed "politically incorrect" by placing offensive content in their lyrics and relying on stage antics to shock listeners and people in their audience. Boston band the F.U.'s generated controversy with their 1983 album, "My America", whose lyrics contained what appeared to be conservative and patriotic views. Its messages were sometimes taken literally, when they were actually intended as a parody of conservative bands.[32] Another act from Massachusetts, Vile, were known to insult women, minorities and homosexuals in their lyrics and would even go as far as putting their albums on the windshields of people's cars.[33] On the other hand, Tim Yohannan and Punk Rock Fanzine Maximumrocknroll were criticized by some Punk Rockers for acting as the "politically correct scene police"[34] and having what was perceived to be "a very narrow definition of what fits into Punk" and apparently being "authoritarian and trying to dominate the scene" with their views.[35] During the 2001–2009 United States presidency of George W. Bush, it was not uncommon for hardcore bands to express anti-Bush messages. During the 2004 United States presidential election, several hardcore punk artists and bands were involved with the anti-Bush political activist group PunkVoter.[36][37] A minority of hardcore musicians have expressed right wing views, such as the band Antiseen, whose guitarist Joe Young ran for public office as a North Carolina Libertarian.[38] Former Misfits singer Michale Graves appeared on an episode of The Daily Show, voicing support for George W. Bush.[39] Conservative Punk was an American website that attempted to merge right-wing politics with the punk subculture.

Moshing

The early 1980s hardcore punk scene developed slam dancing (also called moshing), a style of dance in which participants push or slam into each other, and stage diving. Moshing works as a vehicle for expressing anger by "represent[ing] a way of playing at violence or roughness that allowed participants to mark their difference from the banal niceties of middle-class culture."[40] Moshing is in another way a "parody of violence,"[27][41] that nevertheless leaves participants bruised and sometimes bleeding.[27] The term mosh came into use in the early 1980s American hardcore scene in Washington, D.C. A performance by Fear on the 1981 Halloween episode of Saturday Night Live was cut short when slam dancers, including John Belushi and members of a few hardcore punk bands, invaded the stage, damaged studio equipment and used profanity.[42][43] Those band members included John Joseph and Harley Flanagan of Cro-Mags and John Brannon of Negative Approach and Ian Mackaye of Minor Threat.[44] Other early examples of American hardcore dancing can be seen in the documentaries Another State of Mind, Urban Struggle, The Decline of Western Civilization, American Hardcore, and 30 Years of Northwest Punk.

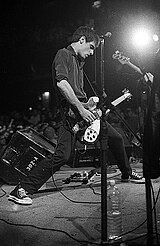

Clothing style

Many North American hardcore punk fans adopted a dressed-down style of T-shirts, jeans, combat boots or sneakers and crewcut-style haircuts. Women in the hardcore scene typically wore army pants, band T-shirts and hooded sweatshirts.[45] The clothing style was a reflection of hardcore ideology, which included dissatisfaction with suburban America and the hypocrisy of American culture. It was essentially deconstruction of American fashion staples—ripped jeans, holey T-shirts, torn stockings for women, and work boots.[46] The style of the 1980s hardcore scene contrasted with the more provocative fashion styles of late 1970s punk rockers (elaborate hairdos, torn clothes, patches, safety pins, studs, spikes, etc.).

Siri C. Brockmeier writes that "hardcore kids do not look like punks", since hardcore scene members wore basic clothing and short haircuts, in contrast to the "embellished leather jackets and pants" worn in the punk scene.[47] Lauraine Leblanc, however, claims that the standard hardcore punk clothing and styles included torn jeans, leather jackets, spiked armbands and dog collars and mohawk hairstyles and DIY ornamentation of clothes with studs, painted band names, political statements, and patches.[48] Tiffini A. Travis and Perry Hardy describe the look that was common in the San Francisco hardcore scene as consisting of biker-style leather jackets, chains, studded wristbands, multiple piercings, painted or tattooed statements (e.g., an anarchy symbol) and hairstyles ranging from military-style haircuts dyed black or blonde to mohawks and shaved heads.[49]

Circle Jerks frontman Keith Morris wrote: "the ... punk scene was basically based on English fashion. But we had nothing to do with that. Black Flag and the Circle Jerks were so far from that. We looked like the kid who worked at the gas station or sub. shop."[50] Henry Rollins stated that for him, getting dressed up meant putting on a black shirt and some dark pants; Rollins viewed an interest in fashion as being a distraction.[51] Jimmy Gestapo from Murphy's Law describes his own transition from dressing in a punk style (spiked hair and a bondage belt) to adopting a hardcore style (shaved head and boots) as being based on needing more functional clothing.[45]

Fanzines

In the pre-Internet era, fanzines, commonly called zines, enabled hardcore scene members to learn about bands, clubs, and record labels. Zines typically included reviews of shows and records, interviews with bands, letters, and ads for records and labels. Zines were DIY products, "proudly amateur, usually handmade, and always independent" and in the "’90s, zines were the primary way to stay up on punk and hardcore." They acted as the "blogs, comment sections, and social networks of their day."[52]

In the American Midwest, the zine Touch and Go described the Midwest hardcore scene from 1979 to 1983. We Got Power described the LA scene from 1981 to 1984, and it included show reviews and band interviews with groups including D.O.A., the Misfits, Black Flag, Suicidal Tendencies and the Circle Jerks. My Rules was a photo zine that included photos of hardcore shows from across the US. In Effect, which began in 1988, described the New York City scene.[52] By 1990, Maximum Rocknroll "had become the de facto bible of the scene." Maximum Rocknroll is a thick, monthly, newsprint magazine with subscriptions in many countries all over the world. MRR had a "passionate yet dogmatic view" of what hardcore was supposed to be, while HeartattaCk and Profane Existence were "even more religious about their DIY ethos." HeartattaCk was mainly about emo and post-hardcore. Profane Existence was mostly about crust punk.[52] The Bay Area zine Cometbus "captured an entire dimension of ’90s punk culture that provided necessary roughage compared to the empty calories of mainstream punk’s MTV/Warped Tour narrative."

Other 1990 zines included Gearhead, Slug and Lettuce and Riot Grrrl. [52] In Canada, the zine Standard Issue chronicles the Ottawa hardcore scene. With the arrival of the Internet, some hardcore punk zines became available online. One example is the e-zine chronicling the Australian hardcore scene, RestAssured.

History

Late 1970s-early 1980s

United States

Los Angeles

Michael Azerrad states that "[b]y 1979 the original punk scene [in Southern California] had almost completely died out." "They were replaced by a bunch of toughs coming in from outlying suburbs who were only beginning to discover punk's speed, power and aggression";"[d]ispensing with all pretension, these kids boiled the music down to its essence, then revved up the tempos...and called the result "hardcore", creating a music that was "younger, faster and angrier, [and] full of...pent-up rage..."[53] Hardcore historian Steven Blush states that for West coasters, the first hardcore record was Out of Vogue by the Santa Ana band Middle Class,[54] released in December 1978.[55] The band pioneered a shouted, fast version of punk rock which would shape the hardcore sound that would soon emerge. In terms of impact upon the hardcore scene, Black Flag has been deemed the most influential group. Michael Azerrad, author of Our Band Could Be Your Life, calls Black Flag the "godfathers" of hardcore punk and states that even "...more than the flagship band of American hardcore", they were "...required listening for anyone who was interested in underground music."[56] Blush states that Black Flag defined American hardcore in the same way that the Sex Pistols defined punk.[15] Formed in Hermosa Beach, California by guitarist and lyricist Greg Ginn, they played their first show in December 1977. Originally called Panic, they changed their name to Black Flag in 1978.[57] Black Flag's sound mixed the raw simplicity of the Ramones with atonal guitar solos and frequent tempo shifts.

By 1979, Black Flag were joined by other Los Angeles-area bands playing hardcore punk, including Fear, the Germs, and the Circle Jerks (featuring Black Flag's original singer, Keith Morris). This group of bands was featured in Penelope Spheeris' 1981 documentary The Decline of Western Civilization.[58] By the time the film was released, other hardcore bands were making a name for themselves in Los Angeles and neighboring Orange County, including The Adolescents, Angry Samoans, Bad Religion, Dr. Know, Ill Repute, Minutemen, New Regime, Suicidal Tendencies, T.S.O.L., Wasted Youth, and Youth Brigade.

Whilst popular traditional punk bands such as the Ramones, The Clash, and Sex Pistols were signed to major record labels, the hardcore punk bands were generally not. Black Flag, however, was briefly signed to MCA subsidiary Unicorn Records, but were dropped because an executive considered their music to be "anti-parent".[59] Instead of trying to be courted by the major labels, hardcore bands started their own independent record labels and distributed their records themselves. Ginn started SST Records, which released Black Flag's debut EP Nervous Breakdown in 1979. SST went on to release a number of albums by other hardcore artists, and was described by Azerrad as "easily the most influential and popular underground indie of the Eighties."[56] SST was followed by a number of other successful artist-run labels—including BYO Records (started by Shawn and Mark Stern of Youth Brigade), Epitaph Records (started by Brett Gurewitz of Bad Religion), New Alliance Records (started by the Minutemen's D. Boon)—as well as fan-run labels like Frontier Records and Slash Records.

Bands also funded and organized their own tours. Black Flag's tours in 1980 and 1981 brought them in contact with developing hardcore scenes in many parts of North America, and blazed trails that were followed by other touring bands.[60][61][62] Youth Brigade and Social Distortion were two of the first hardcore punk bands to create a documentary of their tour, releasing Another State of Mind in 1984.[63] The Another State of Mind tour was funded by "Youth Movement '82", a concert organized by BYO at the Hollywood Palladium that—in addition to Youth Brigade—featured T.S.O.L., The Adolescents, Wasted Youth, Social Distortion and Blades. The concert was one of the largest punk shows ever held around that time, attended by more than 3,500 people.[64] Concerts in the early Los Angeles hardcore scene increasingly became sites of violent battles between police and concertgoers. Another source of violence in LA was tension created by what one writer calls the invasion of "antagonistic suburban poseurs" into hardcore venues.[65] Violence at hardcore concerts was portrayed in episodes of the popular television shows CHiPs and Quincy, M.E.[66]

San Francisco

Shortly after Black Flag debuted in Los Angeles, Dead Kennedys were formed in San Francisco. While the band's early releases were played in a style closer to traditional punk rock, In God We Trust, Inc. (1981) marked a shift into hardcore. Similar to Black Flag and Youth Brigade, Dead Kennedys released their albums on their own label Alternative Tentacles. While not as large as the scene in Los Angeles, the San Francisco Bay Area hardcore scene of the 1980s included a number of noteworthy bands, including Crucifix, Flipper, and Whipping Boy.

Additionally, during this time, seminal Texas-based bands The Dicks, MDC, Verbal Abuse, and Dirty Rotten Imbeciles (D.R.I.) relocated to San Francisco. This scene was helped in particular by the San Francisco club Mabuhay Gardens, whose promoter, Dirk Dirksen, became known as "The Pope of Punk".[67] Another important local institution was Tim Yohannan's fanzine, Maximumrocknroll, as well as his show on Berkeley, California public radio station KPFA Maximum RocknRoll Radio Show, which played the younger Northern California bands. One of those bands was Tales of Terror from Sacramento. Many, including Mark Arm, cite Tales of Terror as a key inspiration for the then-burgeoning grunge scene.[68]

Washington, D.C.

The first hardcore punk band to form on the east coast of the United States was Washington, D.C.'s Bad Brains. Initially formed in 1977 as a jazz fusion ensemble called Mind Power, and consisting of all African-American members, their early foray into hardcore featured some of the fastest tempos in rock music.[69] The band released its debut single, "Pay to Cum", in 1980, and were influential in establishing the D.C. hardcore scene. Hardcore historian Steven Blush calls the single the first East coast hardcore record.[70]

Ian MacKaye and Jeff Nelson, influenced by Bad Brains, formed the band Teen Idles in 1979. The group broke up in 1980, and MacKaye and Nelson went on to form Minor Threat, who became a big influence on the hardcore punk genre. The band used faster rhythms and more aggressive, less melodic riffs than was common at the time. Minor Threat popularized the straight edge movement with its song "Straight Edge", which spoke out against alcohol, drugs and promiscuity.[71][72] MacKaye and Nelson ran their own record label, Dischord Records, which released records by D.C. hardcore bands including: The Faith, Iron Cross, Scream, State of Alert, Government Issue, Void, and DC's Youth Brigade. The Flex Your Head compilation was a seminal document of the early 1980s DC hardcore scene. The record label was run out of the Dischord House, a Washington, D.C. punk house.

Boston

Seminal Boston hardcore bands included Jerry's Kids, Gang Green, The F.U.'s, SS Decontrol, Negative FX, The Freeze and Siege. A faction of the scene was influenced by D.C.'s straight edge scene. Members of bands such as DYS, Negative FX, and SS Decontrol formed the Boston Crew, a militant straight edge group that frequently assaulted punks who drank or used drugs. The controversy surrounding this crew and their antics sparked a debate about violence within the hardcore scene. In the late 1980s, Elgin James became involved in the militant faction of the Boston straight edge scene, and he later helped found the organization Friends Stand United, which would eventually be classified as a street gang.[73] In 1982, Modern Method Records released This Is Boston, Not L.A., a seminal compilation album of the Boston hardcore scene. The compilation included songs by The Proletariat, The Freeze, The F.U.'s, Jerry's Kids and Gang Green. Curtis Casella's Taang! Records was also pivotal in releasing material by bands from this era.

New York

The New York City hardcore scene emerged in 1981 when Bad Brains moved to the city from Washington, D.C.[74][75] Starting in 1981, there was an influx of new hardcore bands in the city, including Beastie Boys, Murphy's Law, Agnostic Front and Warzone. A number of bands associated with New York hardcore scene came from New Jersey, including Misfits, Adrenalin OD and Hogan's Heroes.[76][77] Steven Blush calls the Misfits "crucial to the rise of hardcore."[78] In the early 1980s, the New York hardcore scene was headquartered in a small after-hours bar, A7, on the lower east side of Manhattan. Later, New York's hardcore scene was centered around the bar CBGB, whose owner, Hilly Kristal, embraced hardcore punk. The Dead Boys, originally from Cleveland but gained popularity in New York played at Hilly's club often and he even managed them. The Dead Boys album released in 1977 titled "Young, Loud and Snotty" is an[who?]early hardcore punk album.[citation needed] For several years, CBGB held weekly hardcore matinees on Sundays. This stopped in 1990 when violence led Kristal to ban hardcore shows at the club.

Early radio support in New York's surrounding Tri state area came from Pat Duncan, who had hosted live punk and hardcore bands weekly on WFMU since 1979.[79] Bridgeport, Connecticut's WPKN had a radio show featuring hardcore called Capital Radio, hosted by Brad Morrison, beginning in February 1979 and continuing weekly until late 1983. In New York City, Tim Sommer hosted Noise The Show on WNYU.[80] In 1982, Bob Sallese produced The Big Apple Rotten To The Core compilation on S.I.N. Records, featuring The Mob, Ism and four other bands from the early A7 era. The album gained notoriety on the commercial radio station WLIR, and nationally on college radio. The LP was followed by The Big Apple Rotten To The Core, Vol. 2 in 1987 on Raw Power Records.

Other American cities

Minneapolis hardcore consisted of bands such as Hüsker Dü and The Replacements, while Chicago had Articles of Faith, Big Black and Naked Raygun. The Detroit area was home to Crucifucks, Degenerates, The Meatmen, Necros, Negative Approach, Spite and Violent Apathy. JFA and Meat Puppets were both from Phoenix, Arizona;, 7 Seconds were from Reno, Nevada; and Butthole Surfers, Big Boys, The Dicks, Dirty Rotten Imbeciles (D.R.I.), Really Red, Verbal Abuse and MDC were from Texas. Portland, Oregon hardcore punk bands included Poison Idea, Final Warning and The Wipers. Hardcore bands in Washington state included The Accüsed, The Fartz, Melvins, The Dehumanizers, Subvert, and 10 Minute Warning. Hardcore punk from Raleigh, North Carolina included Corrosion of Conformity. Hardcore punk from South Carolina included Bored Suburban Youth (Columbia), Scott Free (Myrtle Beach), Bazooka Joe (Myrtle Beach), Sex Mutants (Florence), Civilian Chaos Corps (Charleston), and Uncalled Four (Charleston).Dayton, Ohio had Toxic Reasons.

Canada

D.O.A. formed in Vancouver, British Columbia in 1978 and were one of the first bands to refer to its style as "hardcore", with the release of their album Hardcore '81. Other early hardcore bands from British Columbia included Dayglo Abortions, the Subhumans and The Skulls. In 1988, the Dayglo Abortions became the center of national media attention when a police officer instigated a criminal investigation of the band after his daughter brought home a copy of Here Today, Guano Tomorrow. Obscenity charges were laid against the Dayglo Abortion’s record label, Fringe Product, and the label's record store, Record Peddler, but those charges were cleared in 1990.[81][82][83]

Nomeansno is a hardcore band originally from Victoria, British Columbia and now located in Vancouver. SNFU formed in Edmonton in 1981 and also later relocated to Vancouver. Bunchofuckingoofs (BFGs), from the Kensington Market neighbourhood of Toronto, Ontario, formed in November 1983 as a response to "a local war with glue huffing Nazi skinheads."[84]Fucked Up is a Toronto band which won the 2009 Polaris Music Prize for the album The Chemistry of Common Life. One early Montreal hardcore band is The Asexuals, a mainstay of the Montreal punk scene in the 1980s.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom a hardcore scene eventually cropped up. Referred to under a number of names including "U.K. Hardcore", "UK 82", "second wave punk",[85] "real punk",[86] and "No Future punk",[87] it took the previous punk sound and added the incessant, heavy drumbeats and heavily distorted guitar sound of new wave of British heavy metal bands, especially Motörhead.[88] Formed in 1977 in Stoke-on-Trent, Discharge played a huge role in influencing other European hardcore bands. AllMusic calls the band's sound a "high-speed noise overload" characterized by "ferocious noise blasts."[89] Their style of hardcore punk was coined as D-beat, a term referring to a distinctive drum beat that a number of 1980s imitators of Discharge are associated with.[90]

Another UK band, The Varukers, were one of the original D-beat bands,[91] and Sweden in particular produced a number of D-beat bands during this time period including Anti-Cimex, Disfear, and Totalitär. Scottish band The Exploited were also influential, with the term "UK 82" (used to refer to UK hardcore in the early 1980s) being taken from one of their songs. They contrasted with early American hardcore bands by placing an emphasis on appearance. Frontman Walter "Wattie" Buchan had a giant red mohawk and the band continued to wear swastikas, an approach influenced by the wearing of this symbol by 1970s punks such as Sid Vicious. Because of this, The Exploited were labeled by others in the scene as "cartoon punks".[92] Other influential UK hardcore bands from this period included Broken Bones, Chaos UK, Charged GBH, Dogsflesh, Disorder, Anti-Establishment, English Dogs, and grindcore innovators Napalm Death.

Australia

Australian hardcore bands began appearing in the mid-1980s. Massappeal of Sydney began performing in 1985 and released its first album in 1986.[93] Adelaide's Where's the Pope? formed in 1985 and released their first album in 1987.[94] Other Australian hardcore bands include Mindsnare (formed in 1993), Break Even and 50 Lions (formed in 2005), Iron Mind (formed in 2006), and Confession (formed in 2008). Australian hardcore is played on the national Triple J network on the short.fast.loud program.[95] Veganism and straight edge beliefs are becoming more prominent in the hardcore scene, particularly in Adelaide.[96] Labels that release hardcore include Broken Hive Records, El Shaddai Records, Resist Records and UNFD Records.

Other countries

Hardcore scenes also developed in Italy, other European countries, Brazil, Japan, and the Middle East.

There was a dynamic Italian hardcore punk scene in the 1980s. Inspired by UK bands such as Crass and Discharge, many Italian groups had lyrics that were anti-war and anti-NATO. Groups included Wretched, Raw Power, and Negazione. The Last White Christmas festival, held in Pisa on Dec. 4, 1983, was one of the most important concert with a lot of Italian groups (CCM, I Refuse It!, Raw Power, Purid Fever, War Dogs, ecc.). Sweden developed several influential hardcore bands, including Mob 47 and Anti Cimex, whose music has also inspired many foreign bands. Since the early 1990s, many Swedish groups were D-beat "tribute bands" to groups such as UK's Discharge. A hardcore scene that emerged in Umeå and other northern cities in the 1990s, with bands such as Refused (Umeå) and Raised Fist (Luleå). Finland produced some influential hardcore bands, including Terveet Kädet, one of the first hardcore groups to emerge in the country. In Eastern Europe notable hardcore bands included Hungaria's Galloping Coroners from 1975, Yugoslavia's 1980s-era Niet from Ljubljana, KUD Idijoti from Pula, and KBO!.

In Brazil, the hardcore scene was given a jump start with the opening of a punk record shop called Punk Rock Discos in São Paulo in 1979. By the early 1980s, the store was bringing records from England, including British bands like Discharge and Disorder as well as Swedish and Finnish hardcore. Around 1981, punk gigs were happening often around São Paulo, where there were already dozens of active bands, mostly playing hardcore punk and similar styles, most importantly Cólera and Inocentes.

A Japanese hardcore scene arose to protest the social and economic changes sweeping the country in the late 1970s and during the 1980s. The band SS is regarded as the first, forming in 1977.[97] Bands such as The Stalin and GISM soon followed, both forming in 1980. Other notable Japanese hardcore bands include: Anti Feminism, Balzac, Bomb Factory, Disclose (a D-beat band), Garlic Boys, Gauze, The Piass, SOB, and The Star Club.

In recent years, Muslim hardcore bands have emerged in the US, Canada, Pakistan, and Indonesia. The development of Muslim hardcore has been traced to the impact of a 2010 film Taqwacore, a documentary about the Muslim hardcore scene. Bands include "The Kominas from Boston, the all-girl Secret Trial Five from Toronto, Al Thawra (The Power) from Chicago and even a few bands out in Pakistan and Indonesia."[98]

Mid-1980s

The mid-1980s were a time of transition for the hardcore scene. Bands such as Hüsker Dü, Articles of Faith, and new bands formed by members of bands like Deep Wound and Minutemen experimented with other genres and were embraced by college radio, coining the term "College Rock". Many Boston bands such as SS Decontrol, Gang Green, DYS, and The F.U.'s, as well as Midwestern hardcore bands Necros, Negative Approach and The Meatmen moved in a slower, heavier hard rock direction. Crossover thrash was another influential movement in mid-1980s hardcore, with bands like D.R.I., Corrosion of Conformity, Suicidal Tendencies, Los Cycos, Cro-Mags, Fang (band), Agnostic Front, Rich Kids on LSD, The Accüsed and Cryptic Slaughter embracing the thrash metal of bands like Slayer. Most of the Washington, D.C. hardcore scene eschewed hardcore in favor of a college rock-influenced style of punk.

Late 1980s

By the mid to late 1980s, many of the most prominent early hardcore punk bands had broken up. Bad Religion made a progressive rock album with Into the Unknown,[99] the Beastie Boys gained fame by playing hip hop, and Bad Brains incorporated more reggae into their music, such as in their 1989 album Quickness.[100] Social Distortion went on hiatus after its first album was released, due to Mike Ness's drug problems, and returned with a sound based more on country music, which was referred to as cowpunk.[101]

Youth crew

During the late eighties in New York City, Influenced by original straight edge bands 7 Seconds, Minor Threat, Bl'ast, and Uniform Choice, bands spearheaded a youth crew movement. An extension to the original pioneers groundwork of lyrically expressing views against drugs, alcohol and promiscuous sex, this rebirth also focused on topics such as vegetarianism or veganism.[102] In the late 1980s, most bands associated with youth crew included Bold, Gorilla Biscuits, Side by Side, Youth of Today, and beyond the New York area to Southern California bands such as Chain of Strength and Inside Out.

1990s

In the beginning of the 1990s, bands such as Born Against, Rorschach, Burn and Drive Like Jehu took the 1980s styles of hardcore and pushed them into more contemporary sounds. Many of the bands from this era were strongly influenced by other genres, such as heavy metal, alternative, pop, and even rap. Hardcore subsequently became a broad term, as a variety of different genres arose, such as melodic hardcore (Avail, Lifetime, Kid Dynamite), emo (Endpoint, Saves the Day), D-beat (Avskum, Aus Rotten, Skitsystem), powerviolence (Spazz, Dropdead, Charles Bronson), thrashcore (What Happens Next?, Voorhees, Vivisick), mathcore (The Dillinger Escape Plan, Botch, Converge), screamo (Heroin, Antioch Arrow, Portraits of Past, Swing Kids) and rapcore (Biohazard).[103][104][105][106][107]

While the 1990s had many different sounds and styles emerging, the genre primarily branched into two directions; new school metallic hardcore (also referred as metalcore), which incorporated aspects of thrash metal and death metal for a heavier and more technical sound, and old school, reminiscent of the classic beginnings of hardcore punk. "New school" bands such as Strung Out, Earth Crisis, Snapcase, Strife, Hatebreed, 108, Integrity and Damnation A.D. dominated the scene in the early 1990s, but towards the end of the decade, a new-found interest in "old school" had developed, represented by bands like Battery, Ten Yard Fight, In My Eyes, Good Clean Fun, H2O and Better Than a Thousand.[108][109][110][111] As usage of the Internet became a mainstream tool, music festivals such as Hellfest were born. Many of the bands during this time wrote lyrics about abstinence from drugs, politics, civil rights, animal rights and spirituality.

2000s

With the increased popularity of punk rock in the mid-1990s and the 2000s, some hardcore bands signed with major record labels. The first was New York's H2O, who released its album Go (2001) for MCA. Despite an extensive tour and an appearance on Late Night with Conan O'Brien, the album was not commercially successful, and when the label folded, the band and the label parted ways. In 2002, California's AFI signed to DreamWorks Records and changed its sound considerably for its successful major label debut Sing the Sorrow. Chicago's Rise Against were signed by Geffen Records, and three of its releases on the label were certified platinum by the RIAA.[112] Rise Against gradually diminished hardcore elements from their music, culminating with 2008's Appeal to Reason, which lacked the intensity found in their earlier albums.[113][114] Notable independent label Bridge 9 Records have seen several of their artists rise to prominence, including Defeater, Verse and Have Heart, who had a Billboard chart entry with their second album, 'Songs To Scream At The Sun'.[115]

United Kingdom band Gallows were signed to Warner Bros. Records for £1 million.[116] Their major label debut Grey Britain was described as being even more aggressive than their previous material, and the band was subsequently dropped from the label.[117] The UK has also seen a flurry of Melodic Hardcore bands in the 2010s, including Landscapes (who have signed to notable Californian label Pure Noise Records, Bridge 9 Records' Dead Swans, and Heart In Hand (band)

Los Angeles band The Bronx briefly appeared on Island Def Jam Music Group for the release of their 2006 self-titled album, which was named one of the top 40 albums of the year by Spin magazine.[118] They appeared in the Darby Crash biopic What We Do Is Secret, playing members of Black Flag. In 2007, Toronto's Fucked Up appeared on MTV Live Canada, where they were introduced as "Effed Up".[119] During the performance of its song "Baiting the Public", the majority of the audience was moshing, which caused $2000 in damages to the set.[120]

Subgenres and fusion genres

Hardcore punk has spawned a number of subgenres, fusion genres and derivative forms. Its subgenres include D-beat, emo,[19] melodic hardcore and thrashcore. Important fusion genres include crossover thrash,[19] crust punk,[19] grindcore,[19] and metalcore,[19] all of which fuse hardcore punk with extreme metal styles. Key derivatives include post-hardcore and skate punk, and hardcore punk has also influenced a number of heavy metal subgenres.

Subgenres

D-beat

D-beat (also known as discore or kängpunk) is a hardcore punk subgenre, developed in the early 1980s by imitators of the band Discharge, after whom the genre is named, as well as a drum beat characteristic of this subgenre. The bands Discharge[121] and The Varukers[122] are pioneers of the D-beat genre. Robbie Mackey of Pitchfork Media described D-beat as "hardcore drumming set against breakneck riffage and unintelligible howls about anarchy, working-stiffs-as-rats, and banding together to, you know, fight."[123]

Emo and post-hardcore

The 1980s saw the development of post-hardcore, which took the hardcore style in a more complex and dynamic direction, with a focus on singing rather than screaming. The post-hardcore style first took shape in Chicago, with bands such as Big Black, The Effigies and Naked Raygun,[124] while later developed in Washington, DC within the community of bands on Ian MacKaye's Dischord Records with bands such as Fugazi, The Nation of Ulysses, and Jawbox.[125] The style has extended until the late 2000s.[125] The mid-80s Washington, D.C. post-hardcore scene would also see the birth of emo. Guy Picciotto formed Rites of Spring in 1984, breaking free of hardcore's self-imposed boundaries in favor of melodic guitars, varied rhythms, and deeply personal, impassioned lyrics dealing with nostalgia, romantic bitterness, and poetic desperation.[126] Other D.C. bands such as Gray Matter, Beefeater, Fire Party, Dag Nasty, also became connected to this movement.[127][128] The style was dubbed "emo", "emo-core",[129] or "post-harDCore"[130] (in reference to one of the names given to the Washington, D.C. hardcore scene[131]).

Thrashcore

Often confused with crossover thrash and sometimes thrash metal, is thrashcore.[132] Thrashcore (also known as fastcore[133]) is a subgenre of hardcore punk that emerged in the early 1980s.[134] It is essentially sped-up hardcore punk, with bands often using blast beats.[133] Just as hardcore punk groups distinguished themselves from their punk rock predecessors by their greater intensity and aggression, thrashcore groups (often identified simply as "thrash") sought to play at breakneck tempos that would radicalize the innovations of hardcore. Early American thrashcore groups included Cryptic Slaughter (Santa Monica), D.R.I. (Houston), Septic Death (Boise) and Siege (Weymouth, Massachusetts). Thrashcore spun off into powerviolence, another raw and dissonant subgenre of hardcore punk.[132] Notable powerviolence bands include Man is the Bastard and Spazz.

Fusion genres

Grindcore

Grindcore is an extreme genre of music that began the early–mid 1980s. Grindcore music relies on heavy metal instrumentation and eventually changed into a genre similar to death metal. Grindcore vocals, according to AllMusic, range "from high-pitched shrieks to low, throat-shredding growls and barks".[135] Grindcore also features blast beats,[136] According to Adam MacGregor of Dusted, "the blast-beat generally comprises a repeated, sixteenth-note figure played at a very fast tempo, and divided uniformly among the kick drum, snare and ride, crash, or hi-hat cymbal."[136] The band Napalm Death invented the grindcore genre; their debut album Scum was described by AllMusic as "perhaps the most representative example of" grindcore.[137]

Metalcore

Metalcore is a fusion genre which combines hardcore ethics and heavier hardcore music with heavy metal elements. Heavy metal-hardcore punk hybrids arose in the mid-1980s and would also radicalize the innovations of hardcore as the two genres and their ideologies intertwined noticeably,[138] resulting in two main genres one being metalcore. The term has been used to refer to bands that were not purely hardcore nor purely metal such as pioneering bands Earth Crisis, Integrity and Hogan's Heroes.[139]Metallica and Slayer, pioneers of the heavy metal subgenre thrash metal, were influenced by a number of hardcore bands. Metallica's cover album Garage Inc. included covers of two Discharge and three Misfits songs, while Slayer's cover album Undisputed Attitude consisted of covers of predominately hardcore punk bands.

Influence on other genres

Alternative rock

Some hardcore bands began experimenting with other styles as their careers progressed in the 1980s, becoming known as alternative rock.[140] Bands such as Minutemen, Meat Puppets, Hüsker Dü, and The Replacements drew from hardcore they had played earlier in their careers, but broke away from its "loud and fast" formula.

Grunge

In the mid-1980s, northern West Coast state bands such as Melvins, Flipper and Green River developed a sludgy, "aggressive sound that melded the slower tempos of heavy metal with the intensity of hardcore," creating an alternative rock subgenre known as grunge.[141] Grunge evolved from the local Seattle punk rock scene, and it was inspired by bands such as The Fartz, 10 Minute Warning and The Accüsed.[142] Grunge fuses elements of hardcore and heavy metal, although some bands performed with more emphasis on one or the other. Grunge's key guitar influences included Black Flag and The Melvins.[143] Black Flag's 1984 record My War, on which the band combined heavy metal with their traditional sound, made a strong impact in Seattle.[144]

Electronic music

Digital hardcore is a music genre fusing elements of hardcore punk and various forms of electronic music and techno.[145][146] It developed in Germany during the early 1990s, and often features sociological or left-extremist lyrical themes.[145][146] Nintendocore, another musical style, fuses hardcore with video game music, chiptunes, and 8-bit music.[147][148][149]

Sludge metal

Melvins, aside from their influence on grunge, helped create what would be known as sludge metal, which is also a combination between Black Sabbath-style music and hardcore punk.[150] This genre developed during the early 1990s, in the Southern United States (particularly in the New Orleans metal scene).[151][152][153] Some of the pioneering bands of sludge metal were: Eyehategod,[150] Crowbar,[154] Down,[155] Buzzov*en,[152] Acid Bath[156] and Corrosion of Conformity.[153] Later, bands such as Isis and Neurosis,[157] with similar influences, created a style that relies mostly on ambience and atmosphere[158] that would eventually be named atmospheric sludge metal or post-metal.[159]

See also

References

- ^ Glasper 2004, p 47

- ^ a b Ellis, Iain (2008). Rebels Wit Attitude: Subversive Rock Humorists. Counterpoint Press. p. 172. ISBN 9781593762063.

- ^ Thompson, Stacy (Feb 1, 2012). Punk Productions: Unfinished Business. SUNY Press. p. 71. ISBN 9780791484609.

- ^ James F. Short, Lorine A. Hughes (Jan 1, 2006). Studying Youth Gangs. Rowman Altamira. p. 149. ISBN 9780759109391.

- ^ Moore, Ryan (Dec 1, 2009). Sells like Teen Spirit: Music, Youth Culture, and Social Crisis. NYU Press. p. 50. ISBN 9780814796030.

- ^ Waksman, Steve (Jan 5, 2009). This Ain't the Summer of Love: Conflict and Crossover in Heavy Metal and Punk. University of California Press. p. 210. ISBN 9780520943889.

- ^ a b c Chapman, Roger (2010). Culture Wars. M.E. Sharpe. p. 449. ISBN 9780765622501.

- ^ a b Leblanc, Lauraine (1999). Pretty in Punk: Girls' Gender Resistance in a Boys' Subculture. Rutgers University Press. p. 49. ISBN 9780813526515.

- ^ Blush, Stephen (November 9, 2001). American Hardcore: A Tribal History. Feral House. ISBN 0-922915-71-7.

- ^ Milagros Peña, Curry Malott (2004). Punk Rockers' Revolution: A Pedagogy of Race, Class, and Gender. Peter Lang. p. 56. ISBN 9780820461427.

- ^ "Recording Industry Association of America". RIAA. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ "D.O.A. To Rock Toronto International Film Festival". PunkOiUK. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

- ^ "D.O.A." punknews.org. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

- ^ Tim Sommer Sounds 10 October 1981 http://20thcpunkarchives.tripod.com/id62.htm

- ^ a b https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/26264/BrockmeierxDUO.pdf?sequence=1 p. 9

- ^ Steven Blush. American Hardcore: a Tribal History. Feral House, 2001. p. 18

- ^ Symonds, Rene (16 August 2007). "Features – Soul Brothers: DiS meets Bad Brains". Drowned in Sound. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ^ The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition copyright ©2000 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Updated in 2009. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company.

- ^ a b c d e f Kuhn, Gabriel (Feb 1, 2010). Sober Living for the Revolution. PM Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781604863437.

- ^ Ladouceur, Liisa (2004). "Lords Of The New Church". This Magazine.

- ^ Blush, Steven (January 2007). "Move Over My Chemical Romance: The Dynamic Beginnings of US Punk". Uncut.

- ^ a b Pop/Rock » Punk/New Wave » Hardcore Punk. "Hardcore Punk | Significant Albums, Artists and Songs". AllMusic. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- ^ Kortepeterp, Derek, The Rage and the Impact: An Analysis of American Hardcore Punk, p. 12

- ^ a b c d Kortepeter, Derek. "Kortepeterp, Derek, ''The Rage and the Impact: An Analysis of American Hardcore Punk''". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- ^ Steven Blush. American Hardcore: A Tribal Tradition. Feral House, 2001. p. 151

- ^ Hurwitz, Tobias (1999). Punk Guitar Styles: The Guitarist's Guide to Music of the Masters. WAlfred Music Publishing. p. 32.

- ^ a b c Williams, J. Patrick (Apr 17, 2013). Subcultural Theory: Traditions and Concepts. John Wiley & Sons. p. 111. ISBN 9780745637327.

- ^ "Reagan". nestorindetroit.com. Archived from the original on 2007-12-13.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tax Policy, Economic Growth and American Families". house.gov. Internet Archive. July 20, 1995. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ http://www.deeplinking.net/media/NYMHC.pdf

- ^ "Maximum Rocknroll Radio · Dead Reagan Special". Radio.maximumrocknroll.com. 2004-06-06. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ Blush, Steven (2001). American Hardcore. USA: Feral House. p. 186. ISBN 9781932595895.

- ^ "Vile Kill From The Heart Page". Kill From The Heart.

- ^ "Maximum Rocknroll: Kick-Ass Photos From Iconic Punk Mag". WIRED. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- ^ Duncombe, Stephen (2014-11-29). Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture. Microcosm Publishing. ISBN 9781621062783.

- ^ Swanson, David (January 14, 2004). "Punk Rockers Invade Iowa". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2009-03-31.

- ^ "About Punkvoter.com: Members". punkvoter.com. Internet Archive. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007.

- ^ Cotton, Quinn (2001-11-17). "Rocked By The Vote | News | Creative Loafing Charlotte". Charlotte.creativeloafing.com. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ "Brendan Kelly, Michael Graves Daily Show footage online". Punknews.org. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ Martin, Bradford (Mar 1, 2011). The Other Eighties: A Secret History of America in the Age of Reagan. Macmillan. p. 111. ISBN 9781429953429.

- ^ Palmer, Craig T. (Spring 2005). "Mummers and Moshers: Two Rituals of Trust in Changing Social Environments." Retrieved 2014-11-29

- ^ Fear at AllMusic

- ^ "Fear on SNL and Ian MacKaye". culturebully.com. 1 March 2006.

- ^ "Spit Stix interview". Markprindle.com. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ a b https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/26264/BrockmeierxDUO.pdf?sequence=1 Brockmeier, Siri C., “Not Just Boys’ Fun?”: The Gendered Experience of American Hardcore, MA Thesis in American Studies Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages ILOS (Universitet I Oslo, 2009) p. 12

- ^ Thompson, William Forde (Aug 12, 2014). Music in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. p. 500. ISBN 9781452283029.

- ^ https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/26264/BrockmeierxDUO.pdf?sequence=1 p. 11

- ^ Leblanc, Lauraine, Pretty in Punk: Girls' Gender Resistance in a Boys' Subculture. (Rutgers University Press, 1999), p. 52

- ^ Travis, Tiffini A. and Perry Hardy, Skinheads: A Guide to an American Subculture (ABC-CLIO, 2012), p. 123 (section entitled "From San Francisco Hardcore Punks to Skinheads")

- ^ "CITIZINE Interview – Circle Jerks' Keith Morris (Black Flag, Diabetes)". Citizinemag.com. 2003-02-17. Archived from the original on 2011-10-06. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Hardcore Punk | Complex". M.complex.com. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- ^ a b c d Heller, Jason (2013-10-15). "With zines, the '90s punk scene had a living history · Fear Of A Punk Decade · The A.V. Club". Avclub.com. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- ^ Azerrad, Michael (2001). Our Band Could Be Your Life. Bay Back Books. pp. 13–14. ISBN 9780316787536.

- ^ Steven Blush. American Hardcore: A Tribal Tradition. Feral House, 2001. p. 19

- ^ "Middle Class". Flipside. No. 12. Whittier, California. January 1979. p. 6.

- ^ a b Azerrad, Michael. Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground, 1981–1991. Underground Music. ISBN 0-316-78753-1.

- ^ Grad, David (July 1997). "Fade to Black". Spin.

- ^ The Decline of Western Civilization at IMDb

- ^ "Black Flag". Sounds magazine. Retrieved May 27, 2006.

- ^ Black Flag on Punknews.org

- ^ Black Flag at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ "Black Flag". VH1. Archived from the original on 26 May 2009.

- ^ Another State of Mind at IMDb

- ^ "BYO RECORDS – Punk Since 1982". www.byorecords.com. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ "Fantagraphics Books – Los Bros. Hernandez". Fantagraphics.com. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ "Battle of the Bands". CHiPs Wiki.

- ^ Selvin, Joel (2006-11-22). "KEN GARCIA – S.F. Punk – Those Were The Days / Mabuhay Gardens featured likes of Switchblades, Devo". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Gustafson, Guphy (2010-01-01). "Tales of Terror: Bad Dream or Acid Trip?". Midtown Monthly. Retrieved 2012-04-27.

- ^ "Bad Brains". homepages.nyu.edu. New York University.

- ^ Steven Blush. American Hardcore: A Tribal Tradition." Feral House, 2001. p. 19

- ^ Cogan, Brian (2008). The Encyclopedia of Punk. New York: Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4027-5960-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Azerrad, Michael (2001). Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground, 1981–1991. New York: Little, Brown and Company. p. 121. ISBN 0-316-78753-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "FBI — Alleged Founder of Street Gang that Uses Violence to Control Hardcore Punk Rock Music Scene Arrested on Extortion Charge for Shaking Down $5,000 from Recording Artist for Protection". Fbi.gov. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- ^ Andersen, Mark; Mark Jenkins (2001). Dance of Days: Two Decades of Punk in the Nation's Capital. New York: Soft Skull Press. ISBN 1-887128-49-2.

- ^ Blush, Steven (2001). American Hardcore: A Tribal History. Los Angeles: Feral House. ISBN 0-922915-71-7.

- ^ Bello, John (October 1988). Maximum RockNRoll. New York City: 82.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ 1948–1999 Muze, Inc. Hogan's Heroes "POP Artists beginning with 'HOD'". Phonolog (7–278B): 1. 1999. Section 207.

- ^ Steven Blush. American Hardcore: A Tribal Tradition. Feral House, 2001. p. 195

- ^ "Playlists and Archives for Pat Duncan". WFMU. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

- ^ "Tim Sommer". Beastiemania.com. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

- ^ "Record Company Found Not Guilty of Obscenity - Los Angeles Times". Articles.latimes.com. Reuters. 1990-11-09. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- ^ Mary (2012-04-26). "Dayglo Abortions | theVAULTmagazine". Thevaultmag.com. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- ^ Canadian Press, "Record firms, rights groups laud obscenity case ruling: Impact on music industry, criminal laws still in doubt" (November 10, 1990)., Reprinted in The Globe and Mail, p. C13.

- ^ "Goof for life: Garbage day with Crazy Steve of T.O. punk legends Bunchofuckingoofs". Montreal Mirror.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)[dead link] - ^ Glasper 2004, p. 8-9

- ^ Liner notes, Discharge, Hear Nothing See Nothing Say Nothing, Castle, 2003

- ^ Glasper 2004, p. 384.

- ^ Glasper 2004, p. 47

- ^ Dean McFarlane (2002-07-09). "Discharge - Discharge | Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- ^ "I just wanna be remembered for coming up with that f-ckin' D-beat in the first place! And inspiring all those f-ckin' great Discore bands around the world!" – Terry "Tez" Roberts, Glasper 2004, p. 175.

- ^ Glasper 2004, p. 65.

- ^ Glasper 2004, p. 360

- ^ "KFTH - Mass Appeal Page". Homepages.nyu.edu. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- ^ "KFTH - Where's the Pope? Page". Homepages.nyu.edu. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- ^ "SHORT.FAST.LOUD. on Triple J". Abc.net.au. 2004-06-30. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- ^ Winston McCall of Parkway Drive interviewed by Maddi West of db magazine interview

- ^ グローバル・プラス株式会社. "<パンクロックの封印を解く>"東京ロッカーズ"の全貌に迫る『ROCKERS[完全版]』 | V.A.(PUNK) | BARKS音楽ニュース". Barks.jp. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- ^ Sanjiv Bhattacharya. "How Islamic punk went from fiction to reality." The Guardian, Thursday 4 August 2011. Available online at: http://www.theguardian.com/music/2011/aug/04/islamic-punk-muslim-taqwacores Accessed on July 28, 2014.

- ^ Hobey Echlin (2010-03-25). "Bad Religion's Recipe for Longevity – Page 1 – Music – Orange County". OC Weekly. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ "Darryl Jenifer Of Bad Brains: 'I Want To Be The Soldier Of My Music'". Ultimate Guitar Archive. 2007-07-12.

- ^ "A Conversation with Mike Ness of Social Distortion – Music – Music Features – Pittsburgh City Paper". Pittsburghcitypaper.ws. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ "Tension building interview with Ray Cappo". FortuneCity. Internet Archive. Archived from the original on 4 July 2004.

- ^ Ambrose, Joe (2001). "Moshing - An Introduction". The Violent World of Moshpit Culture. Omnibus Press. p. 5. ISBN 0711987440.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ McIver, Joel (2002). "The Shock of the New". Nu-metal: The Next Generation of Rock & Punk. Omnibus Press. p. 10. ISBN 0711992096.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Dent, Susie (2003). The Language Report. Oxford University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0198608608.

- ^ Signorelli, Luca (ed.). "Stuck Mojo". Metallus. Il libro dell'Heavy Metal (in Italian). Giunti Editore Firenze. p. 173. ISBN 8809022300.

- ^ Bush, John (2002). "Limp Bizkit". All Music Guide to Rock. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 656. ISBN 087930653X.

One of the most energetic groups in the fusion of metal, punk and hip-hop sometimes known as rapcore

- ^ Revelation Records. "Bands: Battery". Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ SAVEYOURSCENE.COM. Interviews: Good Clean Fun.[1]. Retrieved 2009-08-30.

- ^ Insound. MP3: Ten Yard Fight, "Hardcore Pride".[2]. Retrieved 2009-08-30. Archived November 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Epitaph Records. "Artist Info: Better Than A Thousand". Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ "Recording Industry Association of America". RIAA. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ Marc Weingarten (2008-09-30). "Appeal to Reason Review | Music Reviews and News". EW.com. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ Stewart, Bill. "Rise Against: Appeal to Reason < PopMatters". Popmatters.com. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ^ http://www.billboard.com/artist/303342/have-heart/chart

- ^ "Gallows working on new album".

- ^ Myers, Ben (2010-01-06). "Gallows' great rock'n'roll swindle". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "The 40 Best Albums of 2006". SPIN.com. 2006-12-14. Archived from the original on 2011-12-09. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sutherland, Sam (2007). "What the Fuck? Curse Word Band Names Challenge the Music Industry". Exclaim! Magazine. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- ^ "Fucked Up Banned From MTV". VICE magazine. TypePad.

- ^ Glasper 2009, p. 26.

- ^ Glasper 2004, p. 65.

- ^ Mackey, Robbie (February 15, 2008). "Disfear: Live the Storm". Pitchfork Media.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Huey, Steve. "Effigies – Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ a b Post-Hardcore at AllMusic

- ^ Greenwald, p. 12-13.

- ^ Blush, Steven (2001). American Hardcore: A Tribal History. New York: Feral House. p. 157. ISBN 0-922915-71-7.

- ^ Greenwald, p. 14.

- ^ Azerrad, Michael (2001). Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground 1981–1991. New York: Little, Brown and Company. p. 380. ISBN 0-316-78753-1.

- ^ Grubbs, Eric (2008). POST: A Look at the Influence of Post-Hardcore-1985-2007. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse, Inc. p. 27. ISBN 0-595-51835-4. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- ^ Grubbs, p. 14.

- ^ a b "Powerviolence: The Dysfunctional Family of Bllleeeeaaauuurrrgghhh!!". Terrorizer (172): 36–37. July 2008.

- ^ a b "Interview with Max Ward". Maximum Rock'n'Roll. Retrieved 19 June 2008.

- ^ Felix von Havoc. Maximumrocknroll. Issue 219

- ^ "Grindcore". AllMusic.

- ^ a b MacGregor, Adam (June 11, 2006). "Agoraphobic Nosebleed - PCP Torpedo / ANBrx". Dusted.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Grindcore at AllMusic. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ Ferris, D.X. (Jun 1, 2008). Slayer's Reign in Blood. A&C Black. p. 146. ISBN 9780826429094.

- ^ 1948–1999 Muze, Inc. Hogan's Heroes. Pop Artists Beginning with Hod, Phonolog, 1999, p. 1. No. 7-278B Section 207.

- ^ Reynolds, Simon (2005). Rip It Up and Start Again: Post Punk 1978–1984. London and New York: Faber and Faber. pp. 460–467. ISBN 0-571-21569-6.

- ^ Azerrad, Michael (2001). Our Band Could Be Your Life. New York: Little, Brown. p. 419. ISBN 0-316-78753-1.

- ^ Pray, D., Helvey-Pray Productions (1996). Hype! Republic Pictures.

- ^ Prown, Pete and Newquist, Harvey P. Legends of Rock Guitar: The Essential Reference of Rock's Greatest Guitarists. Hal Leonard Corporation, 1997. p. 242-243

- ^ Azerrad, Michael. Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground, 1981-1991. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 2001. ISBN 0-316-78753-1, p. 419.

- ^ a b Interview with J. Amaretto of DHR, WAX Magazine, issue 5, 1995. Included in liner notes of Digital Hardcore Recordings, Harder Than the Rest!!! compilation CD.

- ^ a b Empire, Alec (28 December 2006). "On the Digital Hardcore scene and its origins". Indymedia.ie. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- ^ Loftus, Johnny. "HORSE the Band – Biography". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ Payne, Will B. (2006-02-14). "Nintendo Rock: Nostalgia or Sound of the Future". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

- ^ Wright (2010-12-09). "Subgenre(s) of the Week: Nintendocore (feat. Holiday Pop)". The Quest. Archived from the original on January 21, 2012. Retrieved 2011-03-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Huey, Steve. Eyehategod at AllMusic. Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- ^ Doom metal at AllMusic. Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- ^ a b York, William. Buzzov*en at AllMusic. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- ^ a b Huey, Steve. Corrosion of Conformity at AllMusic. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- ^ Huey, Steve. Crowbar at AllMusic. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ Prato, Greg. Down at AllMusic. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- ^ York, William. Acid Bath at AllMusic. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- ^ Burgess, Aaron (2006-05-23). "The loveliest album to crush our skull in months". Alternative Press. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ Downey, Ryan J.. Isis at AllMusic. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- ^ Karan, Tim (2007-02-02). "Post-metal titans sniff, jump into the ether". Alternative Press. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

Bibliography

- Hurchalla, George (2005). Going Underground: American Punk 1979–1992. Zuo Press.

- Manley, Frank (1993). Smash the State: A Discography of Canadian Punk, 1977–92. No Exit. ISBN 0-9696631-0-2.

- Glasper, Ian (2004). Burning Britain: The History of UK Punk, 1980-1984. Cherry Red. ISBN 9781901447248.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Glasper, Ian (2009). Trapped in a Scene: UK Hardcore 1985-1989. Cherry Red Books. ISBN 9781901447613.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)