History of India

- This article is about the history of South Asia prior to the Partition of British India in 1947. For the history of the modern Republic of India, see History of the Republic of India. For the histories of Pakistan and Bangladesh see History of Pakistan and History of Bangladesh.

| History of South Asia |

|---|

|

The history of India begins with the Indus Valley Civilization, which spread and flourished in the north-western part of the Indian subcontinent, from c. 3300 to 1300 BCE. Its Mature Harappan period lasted from 2600-1900 BCE. This Bronze Age civilization collapsed at the beginning of the second millennium BCE and was followed by the Iron Age Vedic period, which extended over much of the Indo-Gangetic plains and which witnessed the rise of major kingdoms known as the Mahajanapadas. In one of these kingdoms Magadha, Mahavira and Gautama Buddha were born in the 6th century BCE, who propagated their Shramanic philosophies among the masses.

Later, successive empires and kingdoms ruled the region and enriched its culture - from the Achaemenid Persian empire[1] around 543 BCE, to Alexander the Great[2] in 326 BCE. The Indo-Greek Kingdom, founded by Demetrius of Bactria, included Gandhara and Punjab from 184 BCE; it reached its greatest extent under Menander, establishing the Greco-Buddhist period with advances in trade and culture.

The subcontinent was united under the Maurya Empire during the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE. It subsequently became fragmented, with various parts ruled by numerous Middle kingdoms for the next ten centuries. Its northern regions were united once again in the 4th century CE, and remained so for two centuries thereafter, under the Gupta Empire. This period, of Hindu religious and intellectual resurgence, is known among its admirers as the "Golden Age of India." During the same time, and for several centuries afterwards, Southern India, under the rule of the Chalukyas, Cholas, Pallavas and Pandyas, experienced its own golden age, during which Indian civilization, administration, culture, and religion (Hinduism and Buddhism) spread to much of south-east Asia.

Islam arrived on the subcontinent in 712 CE, when the Arab general Muhammad bin Qasim conquered Sindh and Multan in southern Punjab,[3] setting the stage for several successive Islamic invasions between the 10th and 15th centuries CE from Central Asia, leading to the formation of Muslim empires in the Indian subcontinent, including the Ghaznavid, the Ghorid, the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire. Mughal rule came to cover most of the northern parts of the subcontinent. Mughal rulers introduced middle-eastern art and architecture to India. In addition to the Mughals, several independent Hindu kingdoms, such as the Maratha Empire, the Vijayanagara Empire and various Rajput kingdoms, flourished contemporaneously, in Western and Southern India respectively. The Mughal Empire suffered a gradual decline in the early eighteenth century, which provided opportunities for the Afghans, Balochis and Sikhs to exercise control over large areas in the northwest of the subcontinent until the British East India Company[4] gained ascendancy over South Asia.

Beginning in the mid-18th century and over the next century, India was gradually annexed by the British East India Company. Dissatisfaction with Company rule led to the First War of Indian Independence, after which India was directly administered by the British Crown and witnessed a period of both rapid development of infrastructure and economic decline.

During the first half of the 20th century, a nationwide struggle for independence was launched by the Indian National Congress, and later joined by the Muslim League. The subcontinent gained independence from Great Britain in 1947, after being partitioned into the dominions of India and Pakistan. Pakistan's eastern wing became the nation of Bangladesh in 1971.

Pre-Historic era

Stone Age

Isolated remains of Homo erectus in Hathnora in the Narmada Valley in Central India indicate that India might have been inhabited since at least the Middle Pleistocene era, somewhere between 200,000 to 500,000 years ago.[5][6] The Mesolithic period in the Indian subcontinent covered a timespan of around 25,000 years, starting around 30,000 years ago. Modern humans seem to have settled the subcontinent towards the end of the last Ice Age, or approximately 12,000 years ago. The first confirmed permanent settlements appeared 9,000 years ago in the Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka in modern Madhya Pradesh. Early Neolithic culture in South Asia is represented by the Mehrgarh findings (7000 BCE onwards) in present day Balochistan, Pakistan. Traces of a Neolithic culture have been found submerged in the Gulf of Khambat, radiocarbon dated to 7500 BCE.[7] Late Neolithic cultures sprang up in the Indus Valley region between 6000 and 2000 BCE and in southern India between 2800 and 1200 BCE.

The region of the subcontinent that is now the country of Pakistan has been inhabited continuously for at least two million years.[8][9] The ancient history of the region includes some of South Asia's oldest settlements[10] and some of its major civilizations.[11][12]

The earliest archaeological site in Pakistan is the palaeolithic hominid site in the Soan River valley.[13] Village life began with the Neolithic site of Mehrgarh,[14] while the first urban civilization of the region was the Indus Valley Civilization,[15] with major sites at Mohenjo Daro and Harappa.[16]

Bronze Age

Template:History of Pakistan rotation

The Bronze Age on the Indian subcontinent began around 3300 BCE with the beginning of the Indus Valley Civilization. Inhabitants of the ancient Indus river valley, the Harappans, developed new techniques in metallurgy and produced copper, bronze, lead and tin.

The Indus Valley Civilization which flourished from about 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE marked the beginning of the urban civilization on the subcontinent. The ancient civilization included urban centers such as Harappa and Mohenjo-daro (in modern day Pakistan), Dholavira and Lothal (in modern day India). It was centred on the Indus River and its tributaries, and extended into the Ghaggar-Hakra River valley,[11] the Ganges-Yamuna Doab,[17] Gujarat,[18] and northern Afghanistan.[19]

The civilization is noted for its cities built of brick, road-side drainage system and multi-storied houses. Among the settlements were the major urban centres of Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, as well as Dholavira, Ganweriwala, Lothal, Kalibangan and Rakhigarhi. It is thought by some that geological disturbances and climate change, leading to a gradual deforestation may ultimately have contributed to the civilization's downfall. The decline of the Indus Valley Civilization also included a break down of urban society and of the use of distinctively urban traits such as the use of writing and seals.[20]

Iron Age

Vedic period

The Vedic culture is the Indo-Aryan culture associated with the Hindu sacred texts of Vedas, which were orally composed in Vedic Sanskrit. Vedas are some of the oldest extant texts. This period lasted from about 1500 BCE to 500 BCE, and during which time the definitions of much of latter Indian language, culture and most importantly, religion were laid down. However, the timing of this period is disputed by some nationalist Indian historians who posit the earlier date of 3000 BCE.[21] Properly speaking, the first 500 years (1500 - 1000 BCE) of the Vedic Age correspond to Bronze Age India and the next 500 years (1000 - 500 BCE) to Iron Age India. Many scholars today postulate an Indo-Aryan migration into India, proposing that early Indo-Aryan speaking tribes migrated into the north-west regions of the Indian subcontinent in the early 2nd millennium BCE. Some scholars postulate these Indo-Aryan tribes as originating in Central Asia and Afghanistan from where they migrated east into India, and west into Mesopotamia and finally assimilating with them whilst spreading their language and culture.[22] This has been opposed by the proponents of Out of India theory, who claim Aryans were indigenous to the Indian subcontinent. It is to be noted that the 19th century "Aryan Invasion theory" has long been abandoned by scholars[citation needed]. Instead the various scenarios of an "Aryan Immigration" are presently researched.

Early Vedic society consisted of largely pastoral groups, with late Harappan urbanization being abandoned for unknown reasons.[23] After the Rigveda, Aryan society became increasingly agricultural, and was socially organized around the four Varnas. In addition to the principal texts of Hinduism (the Vedas), the epics (the Ramayana and Mahabharata) are said to have their ultimate origins during this period.[24] Early Indo-Aryan presence probably corresponds, in part, to the presence of Ochre Coloured Pottery in archaeological findings.[25] The kingdom of the Kurus[26] corresponds to the Black and Red Ware and Painted Gray Ware culture and the beginning of the Iron Age in Northwestern India, around 1000 BCE (roughly contemporaneous with the composition of the Atharvaveda, the first Indian text to mention Iron, as śyāma ayas, literally "black metal"). The Painted Grey Ware culture spanning much of Northern India were prevalent from about 1100 to 600 BCE.[25] This later period also corresponds with a change in outlook towards the prevalent tribal system of living leading to establishment of kingdoms called Mahajanapadas.

The Mahajanapadas

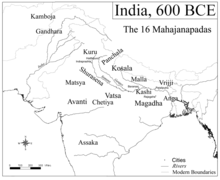

In the later Vedic Age, a number of small kingdoms or city states had covered the subcontinent, many mentioned during Vedic, early Buddhist and Jaina literature as far back as 1000 BCE. By 500 BCE, sixteen monarchies and 'republics' known as the Mahajanapadas — Kasi, Kosala, Anga, Magadha, Vajji (or Vriji), Malla, Chedi, Vatsa (or Vamsa), Kuru, Panchala, Machcha (or Matsya), Surasena, Assaka, Avanti, Gandhara, Kamboja — stretched across the Indo-Gangetic plains from modern-day Afghanistan to Bengal and Maharastra. This period was that of the second major urbanisation in India after the Indus Valley Civilization. Many smaller clans mentioned within early literature seem to have been present across the rest of the subcontinent. Some of these kings were hereditary; other states elected their rulers. The educated speech at that time was Sanskrit, while the dialects of the general population of northern India are referred to as Prakrits. Many of the sixteen kingdoms had coalesced to four major ones by 500/400 BCE, that is by the time of Siddhartha Gautama. These four were Vatsa, Avanti, Kosala and Magadha.[27]

Hindu rituals at that time were complicated and conducted by the priestly class. It is thought that the Upanishads, late Vedic texts dealing mainly with incipient philosophy, were composed in the later Vedic Age and early in this period of the Mahajanapadas (from about 600 - 400 BCE). Upanishads had a substantial effect on Indian philosophy, and were contemporary to the development of Buddhism and Jainism, indicating a golden age of thought in this period. It is believed that in 537 BCE, that Siddhartha Gautama attained the state of "enlightenment", and became known as the 'Buddha' - the awakened one. Around the same time, Mahavira (the 24th Jain Tirthankara according to Jains) propagated a similar theology, that was to later become Jainism.[28] However, Jain orthodoxy believes it predates all known time. The Vedas are believed to have documented a few Jain Tirthankars, and an ascetic order similar to the sramana movement.[29] The Buddha's teachings and Jainism had doctrines inclined toward asceticism, and were preached in Prakrit, which helped them gain acceptance amongst the masses. They have profoundly influenced practices that Hinduism and Indian spiritual orders are associated with namely, vegetarianism, prohibition of animal slaughter and ahimsa (non-violence).

While the geographic impact of Jainism was limited to India, Buddhist nuns and monks eventually spread the teachings of Buddha to Central Asia, East Asia, Tibet, Sri Lanka and South East Asia.

Persian and Greek invasions

Template:History of Pakistan rotation Template:History of Pakistan rotation Much of the northwestern Indian Subcontinent (present day Eastern Afghanistan and Pakistan) came under the rule of the Persian Achaemenid Empire in c. 520 BCE during the reign of Darius the Great, and remained so for two centuries thereafter.[30] In 334 BCE, Alexander the Great conquered Asia Minor and the Achaemenid Empire, reaching the north-west frontiers of the Indian subcontinent. There, he defeated King Puru in the Battle of the Hydaspes (near modern-day Jhelum, Pakistan) and conquered much of the Punjab;[31] however, Alexander's troops refused to go beyond the Hyphases (Beas) River near modern day Jalandhar, Punjab. Alexander left many Macedonian veterans in the conquered regions[citation needed]; he himself turned back and marched his army southwest.

The Persian and Greek invasions had important repercussions on Indian civilization. The political systems of the Persians was to influence future forms of governance on the subcontinent, including the administration of the Mauryan dynasty. In addition, the region of Gandhara, or present-day eastern Afghanistan and north-west Pakistan, became a melting pot of Indian, Persian, Central Asian and Greek cultures and gave rise to a hybrid culture, Greco-Buddhism, which lasted until the 5th century CE and influenced the artistic development of Mahayana Buddhism.

The Magadha Empire

Amongst the sixteen Mahajanapadas, the kingdom of Magadha rose to prominence under a number of dynasties. According to tradition, the Haryanka dynasty founded the Magadha Empire in 684 BC whose capital was Rajagriha, later Pataliputra, near the present day Patna. This dynasty was succeeded by the Shishunaga dynasty which, in turn, was overthrown by the Nanda dynasty in 424 BCE. The Nandas were followed by the Maurya dynasty.

Maurya dynasty

In 321 BCE, exiled general Chandragupta Maurya, under direct patronage of the genius of Chanakya, founded the Maurya dynasty after overthrowing the reigning king Dhana Nanda. Most of the subcontinent was united under a single government for the first time under the Maurya rule. Mauryan empire under Chandragupta would not only conquer most of the Indian subcontinent, but also push its boundaries into Persia and Central Asia, conquering the Gandhara region. Chandragupta Maurya is credited for the spread of Jainism in southern Indian region.

Chandragupta was succeeded by his son Bindusara, who expanded the kingdom over most of present day India, barring Kalinga, and the extreme south and east, which may have held tributary status. Bindusara's kingdom was inherited by his son Ashoka the Great who initially sought to expand his kingdom. In the aftermath of the carnage caused in the invasion of Kalinga, he renounced bloodshed and pursued a policy of non-violence or ahimsa after converting to Buddhism. The Edicts of Ashoka are the oldest preserved historical documents of India, and from Ashoka's time, approximate dating of dynasties becomes possible. The Mauryan dynasty under Ashoka was responsible for the proliferation of Buddhist ideals across the whole of East Asia and South-East Asia, fundamentally altering the history and development of Asia as a whole. Ashoka's grandson Samprati adopted Jainism and helped spread Jainism.

Post Mauryan Magadha dynasties

The Sunga Dynasty was established in 185 BCE, about fifty years after Ashoka's death, when the king Brihadratha, the last of the Mauryan rulers, was murdered by the then commander-in-chief of the Mauryan armed forces, Pusyamitra Sunga. The Kanva dynasty replaced the Sunga dynasty, and ruled in the eastern part of India from 71 BCE to 26 BCE. In 30 BCE, the southern power swept away both the Kanvas and Sungas. Following the collapse of the Kanva dynasty, the Satavahana dynasty of the Andhra kingdom replaced the Magadha kingdom as the most powerful Indian state.

Early middle kingdoms — the golden age

The middle period was a time of notable cultural development. The Satavahanas, also known as the Andhras, were a dynasty which ruled in Southern and Central India starting from around 230 BCE. Satakarni, the sixth ruler of the Satvahana dynasty, defeated the Sunga dynasty of North India. Gautamiputra Satakarni was another notable ruler of the dynasty. Kuninda Kingdom was a small Himalayan state that survived from around the 2nd century BCE to roughly the 3rd century CE. The Kushanas invaded north-western India about the middle of the 1st century CE, from Central Asia, and founded an empire that eventually stretched from Peshawar to the middle Ganges and, perhaps, as far as the Bay of Bengal. It also included ancient Bactria (in the north of modern Afghanistan) and southern Tajikistan. The Western Satraps (35-405 CE) were Saka rulers of the western and central part of India. They were the successors of the Indo-Scythians (see below) and contemporaneous with the Kushans who ruled the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, and the Satavahana (Andhra) who ruled in Central India.

Different empires such as the Pandyan Kingdom, Early Cholas, Chera dynasty, Kadamba Dynasty, Western Ganga Dynasty, Pallavas and Chalukya dynasty dominated the southern part of the Indian peninsula, at different periods of time. Several southern kingdoms formed overseas empires that stretched across South East Asia. The kingdoms warred with each other and Deccan states, for domination of the south. Kalabhras, a Buddhist kingdom, briefly interrupted the usual domination of the Cholas, Cheras and Pandyas in the South.

Northwestern hybrid cultures

The north-western hybrid cultures of the subcontinent included the Indo-Greeks, the Indo-Scythians, the Indo-Parthians, and the Indo-Sassinids. The first of these, the Indo-Greek Kingdom, founded when the Greco-Bactrian king Demetrius invaded the region in 180 BCE, extended over various parts of present-day Afghanistan and Pakistan. Lasting for almost two centuries, it was ruled by a succession of more than 30 Greek kings, who were often in conflict with each other. The Indo-Scythians were a branch of the Indo-European Sakas (Scythians), who migrated from southern Siberia first into Bactria, subsequently into Sogdiana, Kashmir, Arachosia, Gandhara and finally into India; their kingdom lasted from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century BCE. Yet another kingdom, the Indo-Parthians (also known as Pahlavas) came to control most of present-day Afghanistan and northern Pakistan, after fighting many local rulers such as the Kushan ruler Kujula Kadphises, in the Gandhara region. The Sassanid empire of Persia, who were contemporaries of the Guptas, expanded into the region of present-day Pakistan, where the mingling of Indian and Persian cultures gave birth to the Indo-Sassanid culture.

Roman trade with India

Roman trade with India started around 1 CE following the reign of Augustus and his conquest of Egypt, theretofore India's biggest trade partner in the West.

The trade started by Eudoxus of Cyzicus in 130 BCE kept increasing, and according to Strabo (II.5.12.[32]), by the time of Augustus up to 120 ships were setting sail every year from Myos Hormos to India. So much gold was used for this trade, and apparently recycled by the Kushans for their own coinage, that Pliny (NH VI.101) complained about the drain of specie to India:

"India, China and the Arabian peninsula take one hundred million sesterces from our empire per annum at a conservative estimate: that is what our luxuries and women cost us. For what percentage of these imports is intended for sacrifices to the gods or the spirits of the dead?"

— Pliny, Historia Naturae 12.41.84.[33]

These trade routes and harbour are described in detail in the 1st century CE Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.

Gupta dynasty

In the 4th and 5th centuries, the Gupta Dynasty unified northern India. During this period, known as India's Golden Age of Hindu renaissance, Hindu culture, science and political administration reached new heights. Chandragupta I, Samudragupta, and Chandragupta II were the most notable rulers of the Gupta dynasty. The Vedic Puranas are also thought to have been written around this period. The empire came to an end with the attack of the Huns from central Asia. After the collapse of the Gupta Empire in the 6th century, India was again ruled by numerous regional kingdoms. A minor line of the Gupta clan continued to rule Magadha after the disintegration of the empire. These Guptas were ultimately ousted by the Vardhana king Harsha, who established an empire in the first half of the seventh century.

The White Huns, who seem to have been part of the Hephthalite group, established themselves in Afghanistan by the first half of the fifth century, with their capital at Bamiyan. They were responsible for the downfall of the Gupta dynasty, and thus brought an end to what historians consider a golden age in northern India. Nevertheless, much of the Deccan and southern India were largely unaffected by this state of flux in the north.

Late middle kingdoms — the classical age

The classical age in India began with the resurgence of the north during Harsha's conquests around the 7th century, and ended with the fall of the Vijayanagar Empire in the South, due to pressure from the invaders to the north in the 13th century. This period produced some of India's finest art, considered the epitome of classical development, and the development of the main spiritual and philosophical systems which continued to be in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.

King Harsha of Kannauj succeeded in reuniting northern India during his reign in the 7th century, after the collapse of the Gupta dynasty. His kingdom collapsed after his death. From the 7th to the 9th century, three dynasties contested for control of northern India: the Pratiharas of Malwa and later Kannauj; the Palas of Bengal, and the Rashtrakutas of the Deccan. The Sena dynasty would later assume control of the Pala kingdom, and the Pratiharas fragmented into various states. These were the first of the Rajputs, a series of kingdoms which managed to survive in some form for almost a millennium until Indian independence from the British. The first recorded Rajput kingdoms emerged in Rajasthan in the 6th century, and small Rajput dynasties later ruled much of northern India. One Rajput of the Chauhan dynasty, Prithviraj Chauhan, was known for bloody conflicts against the encroaching Islamic Sultanates. The Shahi dynasty ruled portions of eastern Afghanistan, northern Pakistan, and Kashmir from the mid-seventh century to the early eleventh century. Whilst the northern concept of a pan-Indian empire had collapsed at the end of Harsha's empire, the ideal instead shifted to the south.

The Chalukya Empire ruled parts of southern and central India from 550 to 750 from Badami, Karnataka and again from 970 to 1190 from Kalyani, Karnataka. The Pallavas of Kanchi were their contemporaries further to the south. With the decline of the Chalukya empire, their feudatories, Hoysalas of Halebidu, Kakatiya of Warangal, Seuna Yadavas of Devagiri and a southern branch of the Kalachuri divided the vast Chalukya empire amongst themselves around the middle of 12th century. Later during the middle period, the Chola kingdom emerged in northern Tamil Nadu, and the Chera kingdom in Kerala. By 1343 A.D., all these kingdoms had ceased to exist giving rise to the Vijayanagar empire. Southern Indian kingdoms of the time expanded their influence as far as Indonesia, controlling vast overseas empires in Southeast Asia. The ports of southern India were involved in the Indian Ocean trade, chiefly involving spices, with the Roman Empire to the west and Southeast Asia to the east.[34][35] Literature in local vernaculars and spectacular architecture flourished till about the beginning of the 14th century when southern expeditions of the sultan of Delhi took their toll on these kingdoms. The Hindu Vijayanagar dynasty[Karnata Rajya] came into conflict with Islamic rule (the Bahmani Kingdom) and the clashing of the two systems, caused a mingling of the indigenous and foreign culture that left lasting cultural influences on each other. The Vijaynagar Empire eventually declined due to pressure from the first Delhi Sultanates who had managed to establish themselves in the north, centered around the city of Delhi by that time.

The Islamic sultanates

After the Arab invasion of India's ancient western neighbour Persia, expanding forces in that area were keen to invade India, which was the richest classical civilization, with a flourishing international trade and the only known diamond mines in the world. After resistance for a few centuries by various north Indian kingdoms, short lived Islamic empires (Sultanates) got established and spread across the northern subcontinent over a period of a few centuries. But, prior to Turkic invasions, Muslim trading communities had flourished throughout coastal South India, particularly in Kerala, where they arrived in small numbers, mainly from the Arabian peninsula, through trade links via the Indian Ocean. However, this had marked the introduction of an Abrahamic Middle Eastern religion in Southern India's pre-existing dharmic Hindu culture, often in puritanical form. Later, the Bahmani Sultanate and Deccan sultanates flourished in the south.

Delhi sultanate

In the 12th and 13th centuries, Arabs,[36] Turks and Afghans invaded parts of northern India and established the Delhi Sultanate at the beginning of the 13th century, in the former Rajput holdings.[37] The subsequent Slave dynasty of Delhi managed to conquer large areas of northern India, approximate to the ancient extent of the Guptas, while the Khilji Empire was also able to conquer most of central India, but were ultimately unsuccessful in conquering and uniting most of the subcontinent. The Sultanate ushered in a period of Indian cultural renaissance. The resulting "Indo-Muslim" fusion of cultures left lasting syncretic monuments in architecture, music, literature, religion, and clothing. It is surmised that the language of Urdu (literally meaning "horde" or "camp" in various Turkic dialects) was born during the Delhi Sultanate period as a result of the inter-mingling of the local speakers of Sanskritic prakrits with the Persian, Turkish and Arabic speaking immigrants under the Muslim rulers. The Delhi Sultanate is the only Indo-Islamic empire to stake a claim to enthroning one of the few female rulers in India, Razia Sultan (1236-1240).

A Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur began a trek starting in 1398 to invade the reigning Sultan Nasir-u Din Mehmud of the Tughlaq Dynasty in the north Indian city of Delhi.[38] The Sultan's army was defeated on December 17, 1398. Timur entered Delhi and the city was sacked, destroyed, and left in ruins.[39]

The Mughal era

In 1526, Babur, a Timurid (Turco-Persian) descendant of Timur and Genghis Khan, swept across the Khyber Pass and established the Mughal Empire, which lasted for over 200 years.[40] The Mughal Dynasty ruled most of the Indian subcontinent by 1600; it went into a slow decline after 1707 and was finally defeated during the 1857 war of independence also called the Indian rebellion of 1857. This period marked vast social change in the subcontinent as the Hindu majority were ruled over by the Mughal emperors, some of whom showed religious tolerance, liberally patronising Hindu culture, and some of whom destroyed historical temples and imposed taxes on non-Muslims. During the decline of the Mughal Empire, which at its peak occupied an area slightly larger than the ancient Maurya Empire, several smaller empires rose to fill the power vacuum or themselves were contributing factors to the decline. The Mughals were perhaps the richest single dynasty to have ever existed. In 1739, Nader Shah defeated the Mughal army at the huge Battle of Karnal. After this victory, Nader captured and sacked Delhi, carrying away many treasures, including the Peacock Throne.[41]

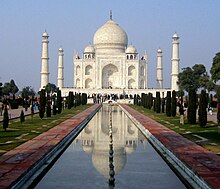

During the Mughal era, the dominant political forces consisted of the Mughal Empire and its tributaries and, later on, the rising successor states - including the Maratha confederacy - who fought an increasingly weak and disfavoured Mughal dynasty. The Mughals, while often employing brutal tactics to subjugate their empire, had a policy of integration with Indian culture, which is what made them successful where the short-lived Sultanates of Delhi had failed. Akbar the Great was particularly famed for this. Akbar declared "Amari" or non-killing of animals in the holy days of Jainism. He rolled back the Jazia Tax for non-Muslims. The Mughal Emperors married local royalty, allied themselves with local Maharajas, and attempted to fuse their Turko-Persian culture with ancient Indian styles, creating unique Indo-Saracenic architecture. It was the erosion of this tradition coupled with increased brutality and centralisation that played a large part in their downfall after Aurangzeb, who unlike previous emperors, imposed relatively non-pluralistic policies on the general population, that often inflamed the majority Hindu population.

Post-Mughal regional kingdoms

The post-Mughal era was dominated by the rise of the Maratha suzerianity as other small regional states (mostly post-Mughal tributary states) emerged, and also by the increasing activities of European powers (see colonial era below). The Maratha Kingdom was founded and consolidated by Shivaji. By the 18th century, it had transformed itself into the Maratha Empire under the rule of the Peshwas. By 1760, the Empire had stretched across practically the entire subcontinent. This expansion was brought to an end by the defeat of the Marathas by an Afghan army led by Ahmad Shah Abdali at the Third Battle of Panipat (1761). The last Peshwa, Baji Rao II, was defeated by the British in the Third Anglo-Maratha War.

Mysore was a kingdom of southern India, which was founded around 1400 CE by the Wodeyar dynasty. The rule of the Wodeyars was interrupted by Hyder Ali and his son Tippu Sultan. Under their rule Mysore fought a series of wars sometimes against the combined forces of the British and Marathas, but mostly against the British with some aid or promise of aid from the French. Hyderabad was founded by the Qutb Shahi dynasty of Golconda in 1591. Following a brief Mughal rule, Asif Jah, a Mughal official, seized control of Hyderabad declaring himself Nizam-al-Mulk of Hyderabad in 1724. It was ruled by a hereditary Nizam from 1724 until 1948. Both Mysore and Hyderabad became princely states in British India.

The Punjabi kingdom, ruled by members of the Sikh religion, was a political entity that governed the region of modern day Punjab. This was among the last areas of the subcontinent to be conquered by the British. The Anglo-Sikh wars marked the downfall of the Sikh Empire. Around the 18th century modern Nepal was formed by Gorkha rulers, and the Shahs and the Ranas very strictly maintained their national identity and integrity.

Colonial era

Vasco da Gama's maritime success to discover for Europeans a new sea route to India in 1498 paved the way for direct Indo-European commerce.[42] The Portuguese soon set up trading-posts in Goa, Daman, Diu and Bombay. The next to arrive were the Dutch, the British—who set up a trading-post in the west-coast port of Surat[43] in 1619—and the French. The internal conflicts among Indian Kingdoms gave opportunities to the European traders to gradually establish political influence and appropriate lands. Although these continental European powers were to control various regions of southern and eastern India during the ensuing century, they would eventually lose all their territories in India to the British islanders, with the exception of the French outposts of Pondicherry and Chandernagore, the Dutch port of Travancore, and the Portuguese colonies of Goa, Daman, and Diu.

The British Raj

The British East India Company had been given permission by the Mughal emperor Jahangir in 1617 to trade in India.[44] Gradually their increasing influence led the de-jure Mughal emperor Farrukh Siyar to grant them dastaks or permits for duty free trade in Bengal in 1717.[45] The Nawab of Bengal Siraj Ud Daulah, the de facto ruler of the Bengal province, opposed British attempts to use these permits. This led to the Battle of Plassey in 1757, in which the 'army' of East India Company, led by Robert Clive, defeated the Nawab's forces. This was the first political foothold with territorial implications that the British acquired in India. Clive was appointed by the Company as its first 'Governor of Bengal' in 1757.[46] After the Battle of Buxar in 1764, the Company acquired the civil rights of administration in Bengal from the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II; it marked the beginning of its formal rule, which was to engulf eventually most of India and extinguish the Moghul rule and dynasty itself in a century.[47] The East India Company monopolized the trade of Bengal. They introduced a land taxation system called the Permanent Settlement which introduced a feudal like structure (See Zamindar) in Bengal. By the 1850s, the East India Company controlled most of the Indian sub-continent, which included present-day Pakistan and Bangladesh. Their policy was sometimes summed up as Divide and Rule, taking advantage of the enmity festering between various princely states and social and religious groups.

The first major movement against the British Company's high handed rule resulted in the Indian Rebellion of 1857, also known as the "Indian Mutiny" or "Sepoy Mutiny" or the "First War of Independence". After a year of turmoil, and reinforcement of the East India Company's troops with British soldiers, the British overcame the rebellion. The nominal leader of the uprising, the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar, was exiled to Burma, his children were beheaded and the Moghul line abolished. In the aftermath all power was transferred from the East India Company to the British Crown, which began to administer most of India as a colony; the Company's lands were controlled directly and the rest through the rulers of what it called the Princely states.

The Indian Independence movement

The first step toward Indian independence and western-style democracy was taken with the appointment of Indian councillors to advise the British viceroy,[48] and with the establishment of provincial Councils with Indian members the councillors' participation was subsequently widened in legislative councils.[49] From 1920 leaders such as Mohandas Gandhi began mass movements to campaign against the British Raj. Revolutionary activities against the British rule also took place throughout the Indian sub-continent, these movements succeeded in bringing Independence to the Indian sub-continent in 1947.

Independence and Partition

| History of India |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

Along with the desire for independence, tensions between Hindus and Muslims had also been developing over the years. The Muslims had always been a minority, and the prospect of an exclusively Hindu government made them wary of independence; they were as inclined to mistrust Hindu rule as they were to resist the Raj. In 1915, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi came onto the scene, calling for unity between the two groups in an astonishing display of leadership that would eventually lead the country to independence. The profound impact Gandhi had on India and his ability to gain independence through a totally non-violent mass movement made him one of the most remarkable leaders the world has ever known. He led by example, wearing homespun clothes to weaken the British textile industry and orchestrating a march to the sea, where demonstrators proceeded to make their own salt in protest against the British monopoly. Indians gave him the name Mahatma, or Great Soul, first suggested by the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore. The British promised that they would leave India by 1947.

British Indian territories gained independence in 1947, after being partitioned into the Union of India and Dominion of Pakistan. Following the division of pre-partition Punjab and Bengal provinces, rioting broke out between Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims in several parts of India, including Punjab, Bengal and Delhi, leaving some 500,000 dead.[50] Also, this period saw one of the largest mass migrations ever recorded in modern history, with a total of 12 million Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims moving between the newly created nations of India and Pakistan.[50]

References

- ^ "Achaemenians". Jona Lendering, Livius.org. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- ^ Plutarchus, Mestrius (1919). Plutarch's Lives. London: William Heinemann. pp. Ch. LX. ISBN 0674991109. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "History in Chronological Order". Government of Pakistan. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- ^ "Pakistan". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- ^ Mudur, G.S (March 21, 2005). "Still a mystery". KnowHow. The Telegraph. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The Hathnora Skull Fossil from Madhya Pradesh, India". Multi Disciplinary Geoscientific Studies. Geological Survey of India. 20 September 2005. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Gaur, A. S. (July 10, 1999). "Ancient shorelines of Gujarat, India, during the Indus civilization (Late Mid-Holocene): A study based on archaeological evidences". Current Science. 77 (1): 180–185. ISSN 0011-3891. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Palaeolithic and Pleistocene of Pakistan". Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

- ^ Murray, Tim (1999). Time and archaeology. London; New York: Routledge. p. 84. ISBN 0415117623.

- ^ Coppa, A. (6 April 2006). "Palaeontology: Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry" (PDF). Nature. 440: 755–756. doi:10.1038/440755a. Retrieved 2007-11-22.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Possehl, G. L. (1990). "Revolution in the Urban Revolution: The Emergence of Indus Urbanization". Annual Review of Anthropology. 19: 261–282. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.19.100190.001401. ISSN 0084-6570. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "possehl" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (2005). The Ancient South Asian World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195174224.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Rendell, H. R. (1989). Pleistocene and Palaeolithic Investigations in the Soan Valley, Northern Pakistan. British Archaeological Reports International Series. Cambridge University Press. p. 364.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jarrige, C. (1995). Mehrgarh Field Reports 1975 to 1985 - From the Neolithic to the Indus Civilization. Dept. of Culture and Tourism, Govt. of Sindh, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, France.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Feuerstein, Georg (1995). In search of the cradle of civilization: new light on ancient India. Wheaton, Illinois: Quest Books. pp. pp. 147. ISBN 0835607208.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kenoyer, J. Mark (1998). The Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195779401.

- ^ Indian Archaeology, A Review. 1958-1959. Excavations at Alamgirpur. Delhi: Archaeol. Surv. India, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Leshnik, Lawrence S. (1968). "The Harappan "Port" at Lothal: Another View". American Anthropologist, New Series,. 70 (5): 911–922. doi:10.1525/aa.1968.70.5.02a00070. ISSN 1548-1433. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Kenoyer, Jonathan (15 September 1998). Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. USA: Oxford University Press. pp. p96. ISBN 0195779401.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ The Post-Urban Period in northwestern India. Retrieved on May 12, 2007.

- ^ See Demise of the Aryan Invasion Theory by Dr. Dinesh Agarwal

- ^ Mallory, J.P. (1989). In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archeology and Myth (Reprint edition (April 1991) ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. pp. p 43. ISBN 0500276161.

The great majority of scholars insist that the Indo-Aryans were intrusive into northwest India

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ India: Reemergence of Urbanization. Retrieved on May 12, 2007.

- ^ Valmiki (1990). Goldman, Robert P (ed.). The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India, Volume 1: Balakanda. Ramayana of Valmiki. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. p. 23. ISBN 069101485X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Krishna Reddy (2003). Indian History. New Delhi: Tata McGraw Hill. pp. p. A11. ISBN 0070483698.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ M. WItzel, Early Sanskritization. Origins and development of the Kuru State. B. Kölver (ed.), Recht, Staat und Verwaltung im klassischen Indien. The state, the Law, and Administration in Classical India. München : R. Oldenbourg 1997, 27-52 = Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies, vol. 1,4, December 1995, [1]

- ^ Krishna Reddy (2003). Indian History. New Delhi: Tata McGraw Hill. pp. p. A107. ISBN 0070483698.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Mary Pat Fisher (1997) In: Living Religions: An Encyclopedia of the World's Faiths I.B.Tauris : London ISBN 1860641482 - Jainism's major teacher is the Mahavira, a contemporary of the Buddha, and who died approximately 526 BCE. Page 114

- ^ Mary Pat Fisher (1997) In: Living Religions: An Encyclopedia of the World's Faiths I.B.Tauris : London ISBN 1860641482 - “The extreme antiquity of Jainism as a non-vedic, indigenous Indian religion is well documented. Ancient Hindu and Buddhist scriptures refer to Jainism as an existing tradition which began long before Mahavira.” Page 115

- ^ Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art (2004). "The Achaemenid Persian Empire (550–330 B.C.E)". Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fuller, J.F.C. (February 3, 2004). "Alexander's Great Battles". The Generalship of Alexander the Great (Reprint ed.). New York: Da Capo Press. pp. 188–199. ISBN 0306813300.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "At any rate, when Gallus was prefect of Egypt, I accompanied him and ascended the Nile as far as Syene and the frontiers of Ethiopia, and I learned that as many as one hundred and twenty vessels were sailing from Myos Hormos to India, whereas formerly, under the Ptolemies, only a very few ventured to undertake the voyage and to carry on traffic in Indian merchandise." Strabo II.5.12. Source

- ^ "minimaque computatione miliens centena milia sestertium annis omnibus India et Seres et paeninsula illa imperio nostro adimunt: tanti nobis deliciae et feminae constant. quota enim portio ex illis ad deos, quaeso, iam vel ad inferos pertinet?" Pliny, Historia Naturae 12.41.84.

- ^ Miller, J. Innes. (1969). The Spice Trade of The Roman Empire: 29 B.C. to A.D. 641. Oxford University Press. Special edition for Sandpiper Books. 1998. ISBN 0-19-814264-1.

- ^ Search for India's ancient city. BBC News. Retrieved on June 22, 2007.

- ^ See P. Hardy's review of Srivastava, A. L. "The Sultanate of Delhi (Including the Arab Invasion of Sindh), A. D. 711-1526", appearing in Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 14, No. 1 (1952), pp. 185-187.

- ^ Battuta's Travels: Delhi, capital of Muslim India

- ^ Timur - conquest of India

- ^ Timur’s Invasion

- ^ The Islamic World to 1600: Rise of the Great Islamic Empires (The Mughal Empire)

- ^ Iran in the Age of the Raj

- ^ "Vasco da Gama: Round Africa to India, 1497-1498 CE". Internet Modern History Sourcebook. Paul Halsall. 1998. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) From: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., The Library of Original Sources (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. V: 9th to 16th Centuries, pp. 26-40. - ^ "Indian History - Important events: History of India. An overview". History of India. Indianchild.com. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "The Great Moghul Jahangir: Letter to James I, King of England, 1617 A.D." Indian History Sourcebook: England, India, and The East Indies, 1617 CE. Internet Indian History Sourcebook, Paul Halsall. 1998. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) From: James Harvey Robinson, ed., Readings in European History, 2 Vols. (Boston: Ginn and Co., 1904-1906), Vol. II: From the opening of the Protestant Revolt to the Present Day, pp. 333–335. - ^ "KOLKATA (CALCUTTA) : HISTORY". Calcuttaweb.com. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ Rickard, J. (1 November 2000). "Robert Clive, Baron Clive, 'Clive of India', 1725-1774". Military History Encyclopedia on the Web. historyofwar.org. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Prakash, Om. "The Transformation from a Pre-Colonial to a Colonial Order: The Case of India" (PDF). Global Economic History Network. Economic History Department, London School of Economics. pp. 3–40. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ Mohsin, K.M. "Canning, (Lord)". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

Indian Council Act of 1861 by which non-official Indian members were nominated to the Viceroy's Legislative Council.

- ^ "Minto-Morley Reforms". storyofpakistan.com. Jin Technologies. June 1 2003. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Symonds, Richard (1950). The Making of Pakistan. London: Faber and Faber. pp. p 74. OCLC 1462689. ASIN B0000CHMB1.

at the lowest estimate, half a million people perished and twelve million became homeless

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)

Further reading

- Allan, J. T. Wolseley Haig, and H. H. Dodwell, The Cambridge Shorter History of India (1934)

- Chandavarkar, Raj. The Origins of Industrial Capitalism in India: Business Strategies and the Working Class in Bombay 1900-1940 (1994)

- Cohen, Stephen P. India: Emerging Power (2002)

- Daniélou, Alain. A Brief History of India (2003)

- Das, Gurcharan. India Unbound: The Social and Economic Revolution from Independence to the Global Information Age (2002)

- Elliot, Sir H. M., Edited by Dowson, John. The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period; published by London Trubner Company 1867–1877. (Online Copy: The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period; by Sir H. M. Elliot; Edited by John Dowson; London Trubner Company 1867–1877 - This online Copy has been posted by: The Packard Humanities Institute; Persian Texts in Translation; Also find other historical books: Author List and Title List)

- Keay, John. India: A History (2001)

- Kishore, Prem and Anuradha Kishore Ganpati. India: An Illustrated History (2003)

- Kulke, Hermann and Dietmar Rothermund. A History of India. 3rd ed. (1998)

- Mahajan, Sucheta. Independence and partition: the erosion of colonial power in India, New Delhi [u.a.] : Sage 2000, ISBN 0-7619-9367-3

- Majumdar, R. C., H.C. Raychaudhuri, and Kaukinkar Datta. An Advanced History of India London: Macmillan. 1960. ISBN 0-333-90298-X

- Majumdar, R. C. The History and Culture of the Indian People New York: The Macmillan Co., 1951.

- Mcleod, John. The History of India (2002)

- Rothermund, Dietmar. An Economic History of India: From Pre-Colonial Times to 1991 (1993)

- Smith, Vincent. The Oxford History of India (1981)

- Spear, Percival. The History of India Vol. 2 (1990)

- Thapar, Romila. Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300 (2004)

- von Tunzelmann, Alex. Indian Summer (2007). Henry Holt and Company, New York. ISBN 0-8050-8073-2

- Wolpert, Stanley. A New History of India 6th ed. (1999)

See also

- History of South Asia

- History of Pakistan

- History of Bangladesh

- Contributions of Indian Civilization

- Economic history of India

- History of Buddhism

- History of Hinduism

- Indian maritime history

- Kingdoms of Ancient India

- Military history of India

- Timeline of Indian history

- Harappan mathematics

- Negationism in India - Concealing the Record of Islam

- Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent