Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington | |

|---|---|

Lexington skyline Donamire Farm | |

| Nickname(s): Athens of the West,[1] Horse Capital of the World | |

Interactive map of Lexington | |

| Coordinates: 38°02′47″N 84°29′49″W / 38.04639°N 84.49694°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Kentucky |

| Counties | Fayette |

| Established | 1782[2] |

| Incorporated | 1831[2] |

| Named for | Lexington, Massachusetts |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | Linda Gorton (R) |

| • Urban County Council | 15-member legislative council |

| Area | |

| • Consolidated city-county | 285.54 sq mi (739.54 km2) |

| • Land | 283.64 sq mi (734.62 km2) |

| • Water | 1.90 sq mi (4.92 km2) |

| • Urban | 87.5 sq mi (226.7 km2) |

| Elevation | 978 ft (298 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Consolidated city-county | 322,570 |

| • Estimate (2022)[5] | 320,347 |

| • Rank | US: 59th Kentucky: 2nd |

| • Density | 1,100/sq mi (440/km2) |

| • Urban | 315,631 (US: 130th)[4] |

| • Metro | 517,056 (US: 109th) |

| • CSA | 745,033 (US: 70th) |

| Demonym | Lexingtonian |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 40502–40517, 40522–40524, 40526, 40533, 40536, 40544, 40546, 40550, 40555, 40574–40583, 40588, 40591, 40598 |

| Area code | 859 |

| FIPS code | 21-46027 |

| Website | www |

Lexington is a consolidated city coterminous with and the county seat of Fayette County, Kentucky, United States. As of the 2020 census the city's population was 322,570, making it the second-most populous city in Kentucky (after Louisville), the 14th-most populous city in the Southeast, and the 59th-most populous city in the United States. By land area, it is the country's 30th-largest city.

Lexington is known as the "Horse Capital of the World" due to the hundreds of horse farms in the region, as well as the Kentucky Horse Park, The Red Mile and Keeneland race courses. It is within the state's Bluegrass region. Notable locations within the city include venues Rupp Arena and Central Bank Center, colleges and universities such as the University of Kentucky, Transylvania University, and Bluegrass Community and Technical College, and the National Thoroughbred Racing Association (NTRA) Headquarters.

The city anchors the Lexington–Fayette metropolitan area of 516,811 people and the greater Lexington–Fayette–Richmond–Frankfort combined statistical area of 747,919 people. It has been consolidated entirely within Fayette County since 1974 and has a nonpartisan mayor-council form of government, with 12 council districts and three members elected at large, with the highest vote-getter designated vice mayor.

History

[edit]Lexington was named in June 1775, in what was then considered Fincastle County, Virginia, 17 years before Kentucky became a state. A party of frontiersmen, led by William McConnell, camped on the Middle Fork of Elkhorn Creek (now known as Town Branch and rerouted under Vine Street) at the site of the present-day McConnell Springs. Upon hearing of the colonists' victory in the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, they named the site Lexington. It was the first of many American places to be named after the Massachusetts town.[6]

On January 25, 1780, 45 original settlers signed the Lexington Compact, known also as the "Articles of Agreement, made by the inhabitants of the town of Lexington, in the County of Kentucky."[7] The settlement at Lexington at this time was also known as Fort Lexington, as it was surrounded by fortifications to protect from potential attacks from British-allied Indians. The Articles allocated land by granting "In" lots of 1/2 acre to each share, along with "Out" lots of 5 acres for each share. Presumably the "In" lots were for the family dwelling inside the fortifications, while the "Out" lots were to be "cleared" for farming. (Corn is the only crop specifically mentioned in the Articles.) It is known that several of these original settlers (perhaps many of them) served under General George Rogers Clark in the Illinois campaign (also called the Northwestern campaign) against the British in 1778–79.[8][9] While the ostensible founder of Lexington, William McConnell, is not one of the signees, an Alexander McConnell is. Within two years of signing the Agreement, both John and Jacob Wymore were killed by Indians in separate incidents outside the walls of "Fort Lexington".[10]

In December 1781, a huge caravan of around 600 pioneers from Spotsylvania County, Virginia—dubbed "The Travelling Church"—arrived in the Lexington area. Led by the preacher Lewis Craig and Captain William Ellis, the Travelling Church established numerous churches, including the South Elkhorn Christian Church in Lexington.[11] On May 6, 1782, the town of Lexington was chartered by an act of the Virginia General Assembly.[2] Around 1790, the First African Baptist Church was founded in Lexington by Peter Durrett,[12] a Baptist preacher and slave held by Joseph Craig. Durrett had helped guide "The Travelling Church" on its trek to Kentucky. This church is the oldest black Baptist congregation in Kentucky and the third-oldest in the United States.[12][13]

In the early 1800s, Lexington was a rising city of the vast territory to the west of the Appalachian Mountains; Josiah Espy described it in a published version of his notes as he toured Ohio and Kentucky:[14]

Lexington is the largest and most wealthy town in Kentucky, or indeed west of the Allegheny Mountains; the main street of Lexington has all the appearance of Market Street in Philadelphia on a busy day ... I would suppose it contains about five hundred dwelling houses [it was closer to three hundred], many of them elegant and three stories high. About thirty brick buildings were then raising, and I have little doubt but that in a few years it will rival, not only in wealth, but in population, the most populous inland town of the United States ... The country around Lexington for many miles in every direction, is equal in beauty and fertility to anything the imagination can paint and is already in a high state of cultivation.[15]

In the early 19th century, Lexington planter John Wesley Hunt became the first millionaire west of the Alleghenies. Henry Clay, a lawyer who married into one of the wealthiest families of Kentucky and served as Speaker of the United States House of Representatives in 1812, helped to lead the War Hawks, pushing for war with Britain to bolster the markets of American products.[16] Six companies of volunteers came from Lexington, with a rope-walk on James Erwin's farm on the Richmond Road used as a recruiting office and barracks until the war ended.[17] Several Lexingtonians served with prominence as officers in the war. For example, Captain Nathaniel G.S. Hart commanded the Lexington Light Infantry (also known as the "Silk Stocking Boys") and was killed while a captive after the Battle of the River Raisin.[18] Henry Clay also served as a negotiator at the Treaty of Ghent in 1814.

The growing town was devastated by a cholera epidemic in 1833, which had spread throughout the waterways of the Mississippi and Ohio valleys: 500 of 7,000 Lexington residents died within two months, including nearly one-third of the congregation of Christ Church Episcopal.[19] London Ferrill, second preacher of First African Baptist, was one of three clergy who stayed in the city to serve the suffering victims.[13]

Farmers in the areas around Lexington held slaves for use as field hands, laborers, artisans, and domestic servants. In the city, slaves worked primarily as domestic servants and artisans, although they also worked with merchants, shippers, and in a wide variety of trades. Farms raised commodity crops of tobacco and hemp, and thoroughbred horse breeding and racing became established in this part of the state. By 1850, Lexington had the highest concentration of enslaved people in the entire state. The city also had a significant population of free blacks, who were often of mixed race. By 1850, First African Baptist Church, led by London Ferrill, a free black from Virginia, had a congregation of 1,820 persons. At that time, First African Baptist Church had the largest congregation of any church, black or white, in the state of Kentucky.[13]

20th century to present

[edit]City school superintendent Massillon Alexander Cassidy (1886–1928) implemented Progressive Era reforms. He focused on upgrading the buildings and setting up teacher-training. He emphasized the need to improve literacy rates and expand access to public schooling. Cassidy's own philosophy stressed the use of science, business, and expertise. He also had a paternalistic attitude toward blacks, who were in segregated public schools.[20]

Amidst the tensions between black and white populations over the lack of affordable housing in the city, a race riot broke out on September 1, 1917. At the time, the Colored A. & M. Fair (one of the largest African American fairs in the South) on Georgetown Pike had attracted more African Americans from the surrounding area into the city. Also during this time, some United States National Guard troops were camping on the edge of the city. Three troops passed in front of an African American restaurant and shoved some people on the sidewalk. A fight broke out, reinforcements for the troops and civilians both appeared, and soon a riot began. The Kentucky National Guard was summoned, and once the riot had ended, armed soldiers and police patrolled the streets. All other National Guard troops were barred from the city streets until the fair ended.[21]

On February 9, 1920, tensions flared up again, this time over the trial of Will Lockett, a black man who murdered Geneva Hardman, a 10-year-old white girl. When a large mob gathered outside the courthouse where Lockett's trial was underway, Kentucky Governor Edwin P. Morrow massed the National Guard troops into the streets to work alongside local law enforcement. As the mob advanced on the courthouse, the National Guard opened fire, killing six and wounding 50 others. Fearing further retaliation from the mob, Morrow urged the United States Army to provide assistance. Led by Brigadier General Francis C. Marshall, approximately 1,200 federal troops from nearby Camp Zachary Taylor moved into the city the same day to assist National Guard forces and local police in bringing order and peace. Marshall declared martial law in the city and had soldiers positioned throughout the area for two weeks. Lockett was eventually executed on March 11 at the Kentucky State Penitentiary in Eddyville, after being found guilty of murdering Hardman.[22]

In 1935, during the Great Depression, the Addiction Research Center (ARC) was created as a small research unit at the United States Public Health Service hospital in Lexington.[23] Founded as one of the first drug rehabilitation clinics in the nation, the ARC was affiliated with a federal prison. Expanded as the first alcohol and drug rehabilitation hospital in the United States, it was known as "Narco" of Lexington. The hospital was later converted to operate as part of the federal prison system; it is known as the Federal Medical Center, Lexington and serves a variety of health needs for prisoners. Lexington also served as the headquarters for a pack horse library in the late 1930s and early 1940s.[24]

Geography

[edit]The Lexington-Fayette metro area includes five additional counties: Clark, Jessamine, Bourbon, Woodford, and Scott. This is the second-largest metro area in Kentucky after Louisville. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 285.5 sq mi (739 km2), of which 284.5 sq mi (737 km2) is land and 1.0 sq mi (2.6 km2), or 0.35%, is covered by water.[25]

Cityscape

[edit]Lexington features a diverse cityscape.

Planning

[edit]

Lexington has had to manage a rapidly growing population while working to maintain the character of the surrounding horse farms that give the region its identity. In 1958, Lexington enacted the nation's first urban growth boundary, restricting new development to an urban service area (USA). It set a minimum area requirement of 40 acres (160,000 m2) to maintain open space for landholdings in the rural service area.[26]

In 1980, the comprehensive plan was updated: the USA was modified to include urban activity centers (UACs) and rural activity centers (RACs).[27] The UACs were commercial and light-industrial districts in urbanized areas, while RACs were retail trade and light-industrial centers clustered around the Interstate 64/Interstate 75 interchanges. In 1996, the USA was expanded when 5,300 acres (21 km2) of the RSA were acquired through the expansion area master plan (EAMP).[26] This was controversial: this first major update to the comprehensive plan in over a decade was accompanied by arguments among residents about the future of Lexington and the Thoroughbred farms.[27]

The EAMP included new concepts of impact fees, assessment districts, neighborhood design concepts, design overlays, mandatory greenways, major roadway improvements, storm water management, and open-space mitigation for the first time. It also included a draft of the rural land management plan, which included large-lot zoning and traffic-impact controls. A pre-zoning of the entire expansion area was refuted in the plan. A 50-acre (200,000 m2) minimum proposal was defeated. Discussion of this proposal appeared to stimulate the development of numerous 10-acre (40,000 m2) subdivisions in the RSAs.[27]

Three years after the expansion was initiated, the RSA land management plan was adopted, which increased the minimum lot size in the agricultural rural zones to 40 acres (160,000 m2).[26] In 2000, a purchase of development rights plan was adopted, granting the city the power to purchase the development rights of existing farms; in 2001, $40 million was allocated to the plan from a $25 million local, $15 million state grant.[27]

Climate

[edit]Lexington is in the northern periphery of the humid subtropical climate zone (Köppen: Cfa),[28] with hot, humid summers and moderately cold winters with occasional mild periods; it falls in USDA hardiness zone 6b.[29] The city and the surrounding Bluegrass region have four distinct seasons that include cool plateau breezes; moderate nights in the summer; and no prolonged periods of heat, cold, rain, wind, or snow. The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 33.9 °F (1.1 °C) in January to 76.7 °F (24.8 °C) in July, while the annual mean temperature is 56.3 °F (13.5 °C).[30] On average, 25 days at or above 90 °F (32 °C) occur annually and 23 days per winter where the high is at or below freezing.[31] Annual precipitation is 49.84 in (1,270 mm), with the late spring and summer being slightly wetter; snowfall averages 14.5 in (37 cm) per season.[31] Extreme temperatures range from −21 °F (−29 °C) on January 24, 1963, to 108 °F (42 °C) on July 10 and 15, 1936.[30]

Lexington is recognized as a high allergy area by the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America.[32]

| Climate data for Lexington, Kentucky (Blue Grass Airport), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1872–present[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 80 (27) |

80 (27) |

86 (30) |

91 (33) |

96 (36) |

104 (40) |

108 (42) |

105 (41) |

103 (39) |

97 (36) |

83 (28) |

75 (24) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 64.2 (17.9) |

68.4 (20.2) |

75.0 (23.9) |

81.6 (27.6) |

87.2 (30.7) |

92.0 (33.3) |

93.9 (34.4) |

93.4 (34.1) |

90.9 (32.7) |

83.6 (28.7) |

73.5 (23.1) |

65.6 (18.7) |

95.9 (35.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 42.3 (5.7) |

46.8 (8.2) |

56.1 (13.4) |

67.2 (19.6) |

75.8 (24.3) |

83.8 (28.8) |

86.9 (30.5) |

86.2 (30.1) |

80.2 (26.8) |

68.6 (20.3) |

55.8 (13.2) |

45.9 (7.7) |

66.3 (19.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 33.9 (1.1) |

37.5 (3.1) |

45.9 (7.7) |

56.2 (13.4) |

65.4 (18.6) |

73.3 (22.9) |

76.7 (24.8) |

75.7 (24.3) |

69.1 (20.6) |

57.8 (14.3) |

46.1 (7.8) |

37.8 (3.2) |

56.3 (13.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 25.4 (−3.7) |

28.3 (−2.1) |

35.8 (2.1) |

45.2 (7.3) |

55.0 (12.8) |

62.8 (17.1) |

66.5 (19.2) |

65.2 (18.4) |

58.1 (14.5) |

47.0 (8.3) |

36.4 (2.4) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

46.3 (7.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 3.5 (−15.8) |

7.8 (−13.4) |

16.9 (−8.4) |

28.1 (−2.2) |

38.9 (3.8) |

49.8 (9.9) |

56.9 (13.8) |

54.9 (12.7) |

43.5 (6.4) |

30.8 (−0.7) |

20.2 (−6.6) |

11.5 (−11.4) |

0.3 (−17.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −21 (−29) |

−20 (−29) |

−2 (−19) |

15 (−9) |

26 (−3) |

39 (4) |

47 (8) |

42 (6) |

32 (0) |

20 (−7) |

−3 (−19) |

−19 (−28) |

−21 (−29) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.42 (87) |

3.64 (92) |

4.48 (114) |

4.42 (112) |

5.44 (138) |

4.96 (126) |

5.12 (130) |

3.71 (94) |

3.42 (87) |

3.66 (93) |

3.37 (86) |

4.20 (107) |

49.84 (1,266) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.7 (12) |

4.5 (11) |

2.8 (7.1) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

1.9 (4.8) |

14.5 (37) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 12.6 | 11.6 | 12.8 | 12.8 | 12.6 | 11.7 | 10.7 | 9.6 | 7.7 | 9.2 | 10.3 | 12.6 | 134.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 4.5 | 3.8 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 13.4 |

| Source: NOAA[30][31] | |||||||||||||

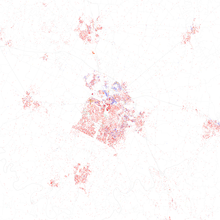

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 834 | — | |

| 1800 | 1,795 | 115.2% | |

| 1810 | 4,326 | 141.0% | |

| 1820 | 5,270 | 21.8% | |

| 1830 | 6,026 | 14.3% | |

| 1840 | 6,997 | 16.1% | |

| 1850 | 8,159 | 16.6% | |

| 1860 | 9,321 | 14.2% | |

| 1870 | 14,801 | 58.8% | |

| 1880 | 16,656 | 12.5% | |

| 1890 | 21,567 | 29.5% | |

| 1900 | 26,369 | 22.3% | |

| 1910 | 35,099 | 33.1% | |

| 1920 | 41,534 | 18.3% | |

| 1930 | 45,736 | 10.1% | |

| 1940 | 49,304 | 7.8% | |

| 1950 | 55,534 | 12.6% | |

| 1960 | 62,810 | 13.1% | |

| 1970 | 108,137 | 72.2% | |

| 1980 | 204,165 | 88.8% | |

| 1990 | 225,366 | 10.4% | |

| 2000 | 260,512 | 15.6% | |

| 2010 | 295,803 | 13.5% | |

| 2020 | 322,570 | 9.0% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 320,347 | [5] | −0.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[33] | |||

The Lexington-Fayette Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) includes Bourbon, Clark, Fayette, Jessamine, Scott, and Woodford Counties. The MSA population is 516,811 as of the 2020 census.[34]

The Lexington–Fayette–Richmond–Frankfort combined statistical area had a population of 747,919 in 2020.[35] This includes the metro area and an additional seven counties.[36]

2020

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[37] | Pop 2010[38] | Pop 2020[39] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 206,174 | 216,072 | 215,343 | 79.14% | 73.05% | 66.76% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 34,876 | 42,336 | 47,501 | 13.39% | 14.31% | 14.73% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 457 | 599 | 480 | 0.18% | 0.20% | 0.15% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 6,360 | 9,506 | 13,374 | 2.44% | 3.21% | 4.15% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 80 | 107 | 133 | 0.03% | 0.04% | 0.04% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 470 | 546 | 1,667 | 0.18% | 0.18% | 0.52% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 3,534 | 6,163 | 14,322 | 1.36% | 2.08% | 4.44% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 8,561 | 20,474 | 29,750 | 3.29% | 6.92% | 9.22% |

| Total | 260,512 | 295,803 | 322,570 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 census, there were 322,570 people, 129,784 households, and 74,761 families within the city. The population density was 1,137.3/sq mi (439.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 70.7% non-Hispanic White, 15.6% Black or African American, 0.3% Native American, 4.1% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, and 2.7% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino residents of any race were 7.4% of the population.

The most common spoken language in Lexington is English with the Southern American English dialect being the native and most common of the city and region, but there are approximately 196 languages from all parts of the world spoken in Lexington.[40] The non-English language spoken by the largest group is Spanish followed by Swahili.[41] Other more common non-English languages in the city are Arabic, Nepali, Japanese, French, Mandarin, Kinyarwanda, Korean and Portuguese.[40] Local estimates drawn from English Language Learner enrollment in Fayette County Public Schools estimates that approximately 23% of the total Lexington population speaks a language other than English at home.[40]

Of the 131,929 households reported in the 2019 American Community Survey, 52% were married couples living together, 15% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27% were non-families. 28.4% of households were home to children under the age of 18. The average household size was 2.37, and the average family size was 2.99. 31.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older.

In 2019, 20.9% of residents were under the age of 18, 14.2% were from 18 to 24, 28.6% from 25 to 44, 23.4% from 45 to 64, and 13.0% were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34.6 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.2 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $57,291 in 2019, slightly below the national average of $62,843, and for a family it was $53,264. Males living alone had a median income of $36,268 versus $30,811 for females. The per capita income for the city was $34,442. About 8.7% of families and 14.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 17.6% of those under the age of 18 and 9.4% of those ages 65 and older.

The table below illustrates the population growth of Fayette County since the first U.S. Census in 1790. Lexington city limits became coterminous with Fayette County in 1974.

Sources:

- 1790 to 1960 census:[42]

- 1970 census:[43]

- 1980 census:[44]

- 1990 census:[45]

- 2000 to 2005 census:[46]

- 2006 census:[47]

Economy

[edit]

Lexington has one of the nation's most stable economies. Lexington describes itself as having "a fortified economy, strong in manufacturing, technology, and entrepreneurial support, benefiting from a diverse, balanced business base".[48] The Lexington Metro Area had an unemployment rate of 3.7% in August 2015, lower than many cities of similar size.[49]

The city is home to several large corporations. Sizable employment is generated by four Fortune 500 companies: Xerox (which acquired Affiliated Computer Services), Lexmark International, Lockheed-Martin, and IBM, employing 3,000, 2,800, 1,705, and 552, respectively.[50] United Parcel Service, Trane, and Amazon.com, Inc. have large operations in the city, and Toyota Motor Manufacturing Kentucky is within the Lexington CSA, located in adjoining Georgetown. A Jif peanut butter plant located in the city produces more peanut butter than any other factory in the world.[51]

Notable corporate headquarters include Lexmark International, a manufacturer of printers and enterprise software;[52] Link-Belt Construction Equipment, a designer and manufacturer of telescopic and lattice boom crawler cranes;[53] Big Ass Fans, a manufacturer of large ceiling fans and lighting fixtures for industrial, commercial, agricultural, and residential use;[54] A&W Restaurants, a restaurant chain known for root beer;[55] and Fazoli's, an Italian-American fast-food chain.[56]

The city's largest employer, the University of Kentucky, employed 16,743 as of 2020.[57]

Other sizable employers include the Lexington-Fayette County government and other hospital facilities. The Fayette County Public Schools employ 5,374, and the Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government employs 2,699. Central Baptist Hospital, Saint Joseph Hospital, Saint Joseph East, and the Veterans Administration Hospital employ 7,000 persons in total.[50]

Arts and culture

[edit]Annual cultural events and fairs

[edit]

June has two popular music festivals: Bluegrass and Broadway. The Festival of the Bluegrass, Kentucky's oldest bluegrass music festival, is in early June; it includes three stages for music and a "bluegrass music camp" for school children. For more than two decades, during the second and third weekends, UK Opera Theatre presents a Broadway medley "It's A Grand Night for Singing!"[58]

Later in June, the Gay and Lesbian Services Organization hosts the Lexington Pride Festival, which celebrates pride of the LGBTQIA+ community and welcomes allies. The festival offers live music, crafts, food, and informational booths from diverse service organizations. Lexington Mayor Jim Gray, elected in 2010 and openly gay, proclaimed June 29, 2013, as Pride Day.[59] Lexington has one of the highest concentrations of gay and lesbian couples in the United States for a city its size.[59]

Area residents gather downtown for the Fourth of July festivities, which extend for several days. On July 3, the Gratz Park Historic District is transformed into an outdoor music hall, when the Patriotic Music Concert is held on the steps of Morrison Hall at Transylvania University. The Lexington Singers and the Lexington Philharmonic Orchestra perform at this event. On the Fourth, events include a reading of the Declaration of Independence on the steps of the Old Courthouse, a 10K run, a parade, street vendors for wares and food, and fireworks.[60][61] The Woodland Arts Fair, an outdoor art fair hosted by the Lexington Art League in the summer, is almost five decades old and attracts over 70,000 attendees.[62][63]

"Southern Lights: Spectacular Sights on Holiday Nights", which takes place from November 18 to December 31, is held at the Kentucky Horse Park. It includes a 3 mi (4.8 km) drive through the park, showcasing numerous displays, many in character with the horse industry and history of Lexington. The "Mini-Train Express", an indoor petting zoo featuring exotic animals, the International Museum of the Horse, an exhibit showcasing the Bluegrass Railway Club's model train, and Santa Claus are other major highlights.[64]

Other events and fares include:

- The Lexington Philharmonic Orchestra presents several annual concerts.[65]

- The Lexington Ballet Company performs their annual Nutcracker Ballet.

- LexArts Gallery HOP is a seasonal event when the city's art galleries are open to the public on the third Friday of January, March, May, July, September, and November.[66]

Historical structures and museums

[edit]

Additional historic sites include:

The University of Kentucky Art Museum is the premier art museum for Lexington and the only accredited museum in the region. Its collection of over 4,000 objects ranges from Old Masters to Contemporary. It regularly hosts special exhibitions.[68]

The local Woolworth's building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places for its significance as a site of protests during the Civil Rights Movement against segregation during the 1960s. Activists conducted sit-ins to gain integrated lunch service, full access to facilities, and more employment. However, in 2004, the building was demolished by its owner, and the area was paved for use as a parking lot until further development.[69]

Pablo Eskobear, the American black bear that overdosed on cocaine that was dropped from smuggler Andrew C. Thornton II's airplane—an incident which inspired the 2023 movie Cocaine Bear—has been stuffed and can be visited at the Kentucky for Kentucky Fun Mall.[70]

Sports

[edit]College athletics

[edit]

The Kentucky Wildcats, the athletic program of the University of Kentucky, is Lexington's most popular sports entity. The school fields 22 varsity sports teams, most of which compete in the Southeastern Conference as a founding member.[71] The men's basketball team is one of the winningest programs in NCAA history, having won eight national championships. The basketball program was also the first to reach 2000 wins.[72]

Professional sports

[edit]

Lexington is home to the Lexington Legends, a member of the Atlantic League of Professional Baseball, an independent MLB Partner league.[73][74] The minor league team plays home games at The Ballpark at 207 Legends Lane. In 2020, the team lost MLB affiliation under a new plan by the MLB.[75]

The city also hosts Lexington SC of third-division professional soccer league USL League One. The club was founded in 2021 and currently plays at Toyota Stadium on the campus of Georgetown College. In October 2023, Lexington SC announced it would be building a new stadium on their youth training ground off of Athens-Boonesboro Road. It will be open by 2024, with a capacity for 5,000 fans, with up to 11,000 possible.[76]

Former professional sport teams based in Lexington were the Kentucky Thoroughblades, Lexington Men O' War, Lexington Bluegrass Bandits, Kentucky Horsemen, Bluegrass Warhorses, Bluegrass Stallions, Lexington Colts, and Lexington Counter Clocks.

Horse racing and equestrian events

[edit]

The city is home to two horse-racing tracks, Keeneland and The Red Mile harness track. Keeneland, sporting live races in April and October, is steeped in tradition; little has changed since the track's opening in 1936. Keeneland hosted the 2015 Breeders' Cup, with the event's signature race, the Breeders' Cup Classic, won by Triple Crown winner American Pharoah. This track also has the world's largest Thoroughbred auction house; 19 Kentucky Derby winners, 21 Preakness Stakes winners, and 18 Belmont Stakes winners were purchased at Keeneland sales. Its most notable race is the Blue Grass Stakes, which is considered an important preparation for the Kentucky Derby. The Red Mile is the oldest horse racing track in the city and the second-oldest in the nation. It runs live harness races, in which horses pull two-wheeled carts called sulkies. The two tracks announced a partnership in 2014.[77]

The Kentucky Horse Park, located along scenic Iron Works Pike in northern Fayette County, is a comparative latecomer to Lexington, opening in 1978. Although commonly known as a tourist attraction and museum, it is also a working horse farm with a farrier and famous retired horses such as 2003 Kentucky Derby winner Funny Cide. Since its opening in April 1978, the Kentucky Horse Park has hosted the Rolex Kentucky Three Day Event, which is one of the top-three annual equestrian eventing competitions in the world and is held immediately before the Kentucky Derby at Churchill Downs in Louisville. In September and October 2010, Lexington was the first city outside of Europe to host the World Equestrian Games.[78]

Other sports

[edit]

Lexington is home to Roller Derby of Central Kentucky and Lexington Bike Polo League. In 2017, Lexington hosted the World Hardcourt Bike Polo Championship, the most competitive bike polo tournament in the world, at facilities in Coolavin Park.[79] Two years prior the city hosted the North American Hardcourt Bike Polo Championship for teams from across Canada, Mexico, and the United States.[80] In 2023, Roller Derby of Central Kentucky returned to competitive play at Central Bank Center after a three-year hiatus.[81]

The Dirt Bowl is a long-standing local basketball tournament held by Lexington Parks and Recreation at Douglass Park. The league has been around since the early 1970s. Sports Illustrated covered it in 1983 and called it one of the premier summer leagues in the country at the time. The basketball courts at Douglass Park were originally dirt, giving the tournament its "Dirt Bowl" name. The courts have since been paved.[82]

Parks and recreation

[edit]City parks and facilities

[edit]

Lexington has over 100 parks, ranging in size from the 8,719 sq ft (810.0 m2) Smith Street Park to the 659-acre (2.7 km2) Masterson Station Park.[83][84] Many Lexington parks recently received improvements as part of a $25,183,270.63 investment from the American Rescue Plan Act.[85] Lexington's parks include:

- Five public golf courses at Kearney Hill Links, Lakeside, Meadowbrook, Tates Creek, and Picadome

- Six dog parks at Jacobson, Masterson Station, Coldstream, Pleasant Ridge, Veteran's Park, and Wellington

- Three public 18-hole disc golf courses at Shillito Park, Jacobson Park, and Veterans Park

- A public skate park at Woodland Park, featuring 12,000 sq ft (1,100 m2) of "ramps, platforms, bowls, and pipes"[83]

- Triangle Park in the heart of downtown Lexington.

- Gatton Park on the Town Branch, a $39 million 10-acre (40,000 m2) private park in the center of downtown, will open in 2025.[86]

Natural areas

[edit]

The city is home to Raven Run Nature Sanctuary, a 734-acre (3.0 km2) nature preserve along the Kentucky River Palisades.[83][87]

The Arboretum is a 100-acre (0.40 km2) preserve adjacent to the University of Kentucky.[83]

The city also plays host to the historic McConnell Springs, a 26-acre (110,000 m2) park within the industrial confines off Old Frankfort Pike.[83][87]

Government

[edit]Mayor

[edit]Lexington-Fayette elects a mayor on a nonpartisan basis every four years.[88] The current mayor, Linda Gorton, is a registered Republican[89] and is in her second term. She defeated former councilmember David Kloiber in the November 2022 General Election by a 71% to 14% margin.[90] Gorton, 75, is eligible to run for one additional term in 2026. The mayor may serve up to three consecutive terms.[88]

Urban County Council

[edit]The city's legislative branch is the 15-member Urban County Council. Twelve of the members represent specific districts and serve two-year terms; three are "at-large" members elected citywide and serve four-year terms. The at-large member receiving the highest number of votes in the general election automatically becomes the vice mayor, who acts as the presiding officer of the council when the mayor is absent. The council members as of 2024 are:[91]

| Councilmember | District | Term ends |

|---|---|---|

| Dan Wu[92] | Vice Mayor | 2026 |

| James Brown[93] | At-large | 2026 |

| Chuck Ellinger II[94] | At-large | 2026 |

| Tayna Fogle[95] | 1st | 2024 |

| Shayla Lynch[96] | 2nd | 2024 |

| Hannah LeGris[97] | 3rd | 2024 |

| Brenda Monarrez[98] | 4th | 2024 |

| Liz Sheehan[99] | 5th | 2024 |

| Denise Gray[100] | 6th | 2024 |

| Preston Worley[101] | 7th | 2024 |

| Fred Brown[102] | 8th | 2024 |

| Whitney Baxter[103] | 9th | 2024 |

| Dave Sevigny[104] | 10th | 2024 |

| Jennifer Reynolds[105] | 11th | 2024 |

| Kathy Plomin[106] | 12th | 2024 |

Government meetings

[edit]

Most Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government meetings are open to the public. Council meetings are held Thursdays at 6 p.m. at the LFUCG Government Center at 200 East Main Street.[107]

Judicial

[edit]

Lexington has three main active judicial courts in its downtown district. It is served by Fayette Circuit Court, Fayette District Court, and US District Court, Eastern District of Kentucky Lexington Division.[108][109]

Education

[edit]

According to the United States Census, among Lexington's population over the age of 25, 22.4% hold a bachelor's degree, 11.4% hold a master's degree, 3.1% hold a professional degree, and 2.6% hold a doctoral degree.

The city is served by the Fayette County Public Schools. The system currently consists of six district high schools, along with multiple smaller multidistrict high schools, 12 middle schools, one combined middle/high school, and 37 elementary schools, and is supplemented with many private schools. FCPS opened two new elementary schools in August 2016, and opened a new high school in August 2017.[110][111][112] Fayette County Public Schools' Fiscal Year 2023 – 2024 general fund budget is $677,440,375.[113]

The two traditional colleges are the University of Kentucky, which is the state's flagship public university, and Transylvania University, which is the state's oldest four-year university and the first university west of the Alleghenies.[114]

Media

[edit]

Lexington's largest daily circulating newspaper is the Lexington Herald-Leader. Business Lexington[115] is a monthly business newspaper. The Chevy Chaser Magazine[116] and Southsider Magazine[116] are two community publications.

The region is also served by eight primary television stations, including WLEX, WKYT, WDKY, WTVQ, WLJC, WUPX, WKLE, WKON. The state's public television network, Kentucky Educational Television, is headquartered in Lexington and is one of the nation's largest public networks, reaching all 1.6 million television households in the state.[117]

Infrastructure

[edit]Transportation

[edit]Highways

[edit]

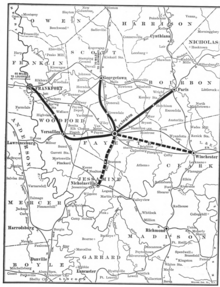

Interstate 75 runs north–south on the edge of Lexington. Interstate 64 runs east–west on the northern edge of the city. Lexington itself is at the confluence of US Route 25, US Route 27, US Route 60, US Route 68 and US Route 421.

Lexington suffers considerable traffic congestion for a city of its size due to the lack of freeways, the proximity of the University of Kentucky to downtown, and the substantial number of commuters from outlying towns.[citation needed] For traffic relief on northern New Circle Road, Citation Boulevard is planned.[118]

Railroads

[edit]

The Southern Railway, well into the 1960s, ran passenger trains through its Lexington station on a Cincinnati-Florida route: the Ponce de Leon and the Royal Palm.[119] The last remnant of the Royal Palm left Lexington in 1970. Union Station, open from 1907 and demolished in March 1960, hosted the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway and the Louisville and Nashville.[120] The C&O's Louisville-Ashland connector train to the company's George Washington[121] ran until 1970.

Airport

[edit]The Blue Grass Airport is on the west side of Lexington on US Route 60. It has passenger flights by four carriers: Allegiant, American, Delta and United.[122]

Modal characteristics

[edit]In 2019, 79.3% of working Lexingtonians commuted by driving alone, 9.3% carpooled, 2.0% used public transportation, and 3.0% walked. 1.9% of commuters used all other forms of transportation, including taxi, bicycle, and motorcycle. About 4.4% worked from home.[123]

In 2015, 7.2 percent of city of Lexington households were without a car, which increased slightly to 7.4 percent in 2016. The national average was 8.7 percent in 2016. Lexington averaged 1.7 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8 per household.[124]

Law enforcement

[edit]Primary law enforcement duties within Lexington-Fayette County are the responsibility of the Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government Division of Police. As of July 1, 2021, the Division of Police (also called Lexington Police Department) is authorized for 639 sworn police officers and 16 traffic safety officers. The Division of Police resulted from the merger of the Lexington Police Department with the Fayette County Patrol in 1974. The Fayette County Sheriff's Office is responsible for court service, including court security, prisoner transport, process and warrant service, and property tax collection. The 1974 merger also consolidated the office of city jailer into the office of county jailer, a constitutional position. In 1992 (effective 1993), the Kentucky General Assembly enabled a correctional services division to be established by ordinance, making employees civil-service employees rather than political appointees.[125]

Fire protection

[edit]All fire/rescue protection within Lexington-Fayette County (with the exception of the Blue Grass Airport) is provided by the Lexington Fire Department. The current department was formed with the merger of the county and city fire departments in 1973. Lexington Fire Department is the largest single fire department in Kentucky with over 600 personnel and 24 individual fire stations broken into five districts (battalions).[126]

Notable people

[edit]Sister cities

[edit]Lexington has four sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International:

Deauville, Calvados, Normandy, France (since 1957)[127]

Deauville, Calvados, Normandy, France (since 1957)[127] County Kildare, Leinster, Ireland (since 1984)[127]

County Kildare, Leinster, Ireland (since 1984)[127] Newmarket, Suffolk, United Kingdom (since 2003)[127][128]

Newmarket, Suffolk, United Kingdom (since 2003)[127][128] Shinhidaka, Hokkaido, Japan (since 2006)

Shinhidaka, Hokkaido, Japan (since 2006)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ Official records for Lexington were kept at the State College on South Limestone Street from October 1872 to July 1876 before closing, the Tower State College Building on the University of Kentucky campus from September 1888 to July 1915 after reopening downtown in 1887, various locations near downtown from July 1915 to July 1944, and Blue Grass Airport since July 1944. For more information, see [1].

References

[edit]- ^ "Athens of the West". National Register of Historic Places (Essay). National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. May 2, 2019. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c Commonwealth of Kentucky. Office of the Secretary of State. Land Office. "Lexington, Kentucky". Accessed September 18, 2013.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

- ^ United States Census Bureau (December 29, 2022). "2020 Census Qualifying Urban Areas and Final Criteria Clarifications". Federal Register. Archived from the original on December 30, 2022. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ^ a b "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places in Kentucky: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2022". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 20, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ Ramsay, Robert L. (1952). Our Storehouse of Missouri Place Names. University of Missouri Press. p. 16. ISBN 9780826205865. Archived from the original on April 2, 2024. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ Of these 45 original co-founders, the most common surnames were Wymore (4) and Thompson (3), while Johnson, Niblack, Collins, McDonald, Lindsay, Shannon, Stevenson, and Martin have two signees per name. The Lexington "Articles of Agreement" can be found in the Pogue Library of Murray State University, Murray, KY.

- ^ Paul L. Trovillion, Jr., A History and Genealogy of the Wymores of Southern Illinois,' pp. 1–4, 'Silver Horse: Paducah, KY, 1998.

- ^ Copies of the full Lexington "Articles of Agreement" may be found in the Pogue Library, Murray State University, and in Fayette County, Kentucky Records, Vol. 1: pp. 356–357, by Michael L. Cook, C.G. & Betty Cummings Cook, C.G. Cook Publications, 3318 Wimberg, Evansville, IN 47712.

- ^ Paul L. Trovillion, Jr., A History and Genealogy of the Wymores", p. 6.

- ^ George Washington Ranck (1910). The Travelling Church: An Account of the Baptist Exodus from Virginia to Kentucky in 1781 under the Leadership of Rev. Lewis Craig and Capt. William Ellis. Louisville, KY. p. 22. Archived from the original on April 2, 2024. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "First African Baptist Church" Archived June 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Lexington: The Athens of the West, National Park Service. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c H. E. Nutter, "A Brief History of the First Baptist Church (Black) Lexington, Kentucky" Archived September 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, in Souvenir, Sesqui-Centennial Celebration, 1790–1940, Lexington, KY: 1940, accessed August 22, 2010

- ^ Espy, Josiah. "Memorandums of a Tour in Ohio and Kentucky in 1805". Espy – Morehead, Phil and Pat. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ "Athens of the West;" Lexington, Kentucky: The Athens of the West – A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary; National Park Service; 2009

- ^ Hammack, James W. Jr. (1976). Kentucky and the Second American Revolution: The War of 1812. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

- ^ Coleman, J. Winston (1981). Lexington, the Athens of the West. Lexington, Ky.: Winburn Press. p. 28.

- ^ Lindsey, Helen B. (July 1944). "The Lexington Light Infantry Company War of 1812". Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society. 42 (140): 263–266.

- ^ "Christ Church Episcopal" Archived June 28, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Lexington, National Park Service. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ^ Richard E. Day and Lindsey N. DeVries. "A Southern Progressive: M. A. Cassidy and the Lexington Schools, 1886–1928." American Educational History Journal 39.1/2 (2012): 107–125.

- ^ "Race Riot of 1917 (Lexington, KY)". Notable Kentucky African Americans Database. Archived from the original on February 5, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ Brackney, Peter (January 20, 2020). The Murder of Geneva Hardman and Lexington's Mob Riot of 1920. The History Press. pp. 89–100, 103–120. ISBN 978-1-4671-4396-7.

- ^ "History of the Addiction Research Center". Drugabuse.gov. May 15, 1935. Archived from the original on August 25, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ "Need in Kentucky". The Indianapolis Star. November 21, 1937. Archived from the original on April 2, 2024. Retrieved September 3, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Fayette County". QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

- ^ a b c "\"Greenbrier Small Area Plan\" (PDF)" (PDF) (Press release). Lexington-Fayette Urban County, Kentucky. April 17, 2003. Archived from the original on June 22, 2019. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Planning History" (Press release). Lexington-Fayette Urban County, Kentucky. Archived from the original on May 23, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ How Stuff Works Archived October 19, 2014, at the Wayback Machine map of American climate zones. Retrieved on January 31, 2010

- ^ United States Department of Agriculture. "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". United States National Arboretum. Archived from the original on March 3, 2015. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Station Name: KY LEXINGTON BLUEGRASS AP". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on July 11, 2022. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ "Information About Asthma, Allergies, Food Allergies and More!". Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. Archived from the original on December 31, 2010. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. July 2015. Archived from the original (CSV) on February 14, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

- ^ "Table 2. Annual Estimates of the Population of Combined Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". 2015 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 2015. Archived from the original (CSV) on February 14, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Population of Combined Statistical Areas: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2006 (CBSA-EST2006-02)". 2006 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. April 5, 2007. Archived from the original (CSV) on September 14, 2007. Retrieved April 7, 2007.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Lexington-Fayette, California". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 2, 2024. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Lexington-Fayette urban county, California". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 2, 2024. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Lexington-Fayette urban county, California". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 3, 2024. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Global Lex". City of Lexington. Archived from the original on October 18, 2023.

- ^ "Galls' English classes give Congolese refugees confidence on the job". WLEX. March 25, 2022. Archived from the original on April 23, 2023.

- ^ Hillery, George A. Jr. (1966). Population Growth in Kentucky, 1820–1960. University of Kentucky Agriculture Experiment Station.

- ^ 1970 Census of the Population, Volume 1: Characteristics of the Population, Part 19, Kentucky. United States Government Printing Office. 1973.

- ^ 1980 Census of the Population, Volume 1: Characteristics of the Population, Part 19, Kentucky. United States Government Printing Office. 1982.

- ^ "KSDC News". Kentucky State Data Center. Spring 1997.

- ^ "Lexington-Fayette, Kentucky – Population finder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Population for Incorporated Places in Kentucky". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 30, 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- ^ "A Fortified Economy" (PDF). delta-sky.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 1, 2008. Retrieved September 15, 2008.

- ^ "Lexington-Fayette, KY Economy at a Glance". www.bls.gov. Archived from the original on June 9, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ a b "Major Employers". Commerce Lexington. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ "Fun Tidbits". The J.M. Smucker Co. Archived from the original on March 28, 2010. Retrieved December 28, 2007.

- ^ "Company Overview – Lexmark United States". Archived from the original on July 17, 2016. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ "ABOUT ~ Link-Belt Construction Equipment Co". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ "About Big Ass Solutions – Big Ass Fans". Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ "Lexington, KY local and state news by the Lexington Herald-Leader - Kentucky.com". kentucky.com. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ "Fazoli's Company Info". fazolis.com. Archived from the original on August 19, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ "Major Regional Employers". Commerce Lexington. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ Hale, Whitney (May 30, 2013). ""It's a Grand Night for Singing!" Turns 21". UKNow. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ a b Mead, Andy (November 7, 2010). "Lexington to become third-largest U.S. city with an openly-gay mayor". Lexington Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ "Ace Weekly's July 4th Weekend Guide". Ace Weekly. July 2002. Archived from the original on July 3, 2024. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ "Fourth of July Celebration". lexingtonky.gov. July 2, 2024. Archived from the original on July 2, 2024. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ "Woodland Arts Fair". lexingtonartleague.org. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ "About". woodlandartfair.org. Archived from the original on June 15, 2024. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ "Holiday Admission Discount Coupon". kyhorsepark.com. Archived from the original on February 6, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- ^ "The Lexington Philharmonic Online". Lexington, Kentucky, USA: lexphil.org. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ^ "LexArts Hop 2018". lexarts.org. Archived from the original on February 22, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ "Lexington Opera House". Lexington Opera House. Archived from the original on April 2, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ "University of Kentucky Art Museum". Uky.edu. Archived from the original on November 10, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ "Downtown Lexington's Next Loss: Woolworth's". Preservation. August 2004. Retrieved March 7, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Cocaine Bear, Lexington, Kentucky". RoadsideAmerica.com. Archived from the original on March 1, 2023. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "SEC History". secsports.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ "'Uk2k' shirt a surprise winner". December 23, 2009. Archived from the original on May 16, 2010. Retrieved September 13, 2010. Herald-Leader [Lexington]

- ^ "Legends join the Atlantic League of Professional Baseball". The Lane Report. February 18, 2021. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "We're The Lexington Counter Clocks". Lexington Counter Clocks. March 6, 2023. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023.

- ^ "Lexington Legends part of proposed downsizing". kentucky.com. Archived from the original on November 27, 2019. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- ^ "Lexington Sporting Club Announces New State of the Art Stadium". lexsporting.com. Archived from the original on January 17, 2024. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ "Red Mile and Keeneland Joint Venture – Red Mile – Lexington, Kentucky". October 13, 2014. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ "2010 Alltech FEI World Equestrian Games". Archived from the original on March 18, 2012. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ^ "2017 World Hardcourt Bike Polo Championship". 2017 World Hardcourt Bike Polo Championship. Archived from the original on July 2, 2022. Retrieved April 28, 2022.

- ^ "2015 North American Hardcourt Championship – Lexington Bicycle Polo League". September 30, 2017. Archived from the original on May 22, 2022.

- ^ "The Return of ROCK! Home Bout Double Header! – ROCK". August 20, 2023. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ "Super Sunday: Dirt Bowl Summer Basketball League Showcase". City of Lexington. Archived from the original on October 29, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Fun Guide 2007. City of Lexington, Kentucky, Division of Parks and Recreation. 2007.

- ^ "Parks – Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government". Archived from the original on February 19, 2016.

- ^ "American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA)". City of Lexington. Archived from the original on September 21, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ "Construction update on Lexington's new $39 million 'living room,' set to open in 2025". Yahoo News. January 1, 2024. Archived from the original on January 3, 2024. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ a b "Parks – Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government". Archived from the original on October 16, 2006. Retrieved August 31, 2006.

- ^ a b "Elected officials". City of Lexington. Archived from the original on September 3, 2023. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ Kapos, Shia (December 8, 2021). "It's Kentucky straight in Lexington City Hall". POLITICO. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ "Results: Mayor Linda Gorton defeats David Kloiber in Lexington, Kentucky's mayoral election". Yahoo Sports. November 17, 2022. Archived from the original on September 3, 2023. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ "Councilmembers | City of Lexington". Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "Council At-Large and Vice Mayor, Dan Wu". City of Lexington. Archived from the original on March 20, 2019. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ "Council At-Large, James Brown". City of Lexington. Archived from the original on September 3, 2023. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ "Council-at-large 2nd member". Archived from the original on August 15, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "Council District 1, Tayna Fogle". City of Lexington. Archived from the original on September 3, 2023. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ "2nd district council member". Archived from the original on December 8, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "3rd district council member". Archived from the original on September 21, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "4th district council member". Archived from the original on September 20, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "5th district council member". Archived from the original on September 20, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "Council District 6, Denise Gray, JD". City of Lexington. Retrieved September 3, 2024.

- ^ "7th district council member". Archived from the original on September 21, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "8th district council member". Archived from the original on September 21, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "9th district council member". Archived from the original on September 21, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "Council District 10, Dave Sevigny". City of Lexington. Archived from the original on November 24, 2018. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ "Council District 11, Jennifer Reynolds". Archived from the original on May 29, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "12th district council member". Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ^ "Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government – Calendar". lexington.legistar.com. Archived from the original on September 3, 2023. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ "Fayette – Kentucky Court of Justice". kycourts.gov. Archived from the original on October 29, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ "Eastern District of Kentucky | United States District Court". www.kyed.uscourts.gov. Archived from the original on October 3, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ Honeycutt Spears, Valarie (August 4, 2016). "Fayette County Schools: What you need to know about new school year". Lexington Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ "Fayette County redistricting plans posted for elementary and middle schools". WKYT-TV. January 30, 2015. Archived from the original on July 13, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Honeycutt Spears, Valarie (February 4, 2015). "State approves a new Fayette County high school; construction could begin in June". Lexington Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on February 5, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Budget & Financial Planning – Fayette County Public Schools". www.fcps.net. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ Transylvania University. 2016. https://www.transy.edu/about/our-history Archived April 17, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Business". Smiley Pete Publishing. Archived from the original on July 10, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ a b "Community". Smiley Pete Publishing. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ "KET Annual Report FY 2017". issuu. February 15, 2018. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ^ Aretakis, Rachel (August 7, 2013). "Citation Boulevard extension begins". Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on July 9, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ^ Official Guide of the Railways, July 1965, Southern Railway section, Tables L, M, O, P

- ^ Official Guide of the Railways, December 1951, Index of Railroad Stations

- ^ C&O/B&O timetable, April 26, 1964, Table 3 https://streamlinermemories.info/Eastern/C&OB&O64TT.pdf Archived November 1, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Airline Destinations". Blue Grass Airport. Archived from the original on January 22, 2024. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ "Means of Transportation to Work by Age". Census Reporter. Archived from the original on January 28, 2022. Retrieved January 28, 2022.

- ^ "Car Ownership in U.S. Cities Data and Map". Governing. December 9, 2014. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ^ KRS 67A.028

- ^ "Lexington". www.kentuckyfiretrucks.com. Archived from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "sister cities". Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ^ "Newmarket, England". Lexington Sister Cities. Archived from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Day, Richard E., and Lindsey N. DeVries. "A Southern Progressive: M. A. Cassidy and the Lexington Schools, 1886–1928." American Educational History Journal 39.1/2 (2012): 107–125 online.

- Gelbert, Doug. A Walking Tour of Lexington, Kentucky (2011) excerpt and text search

- Leet, Karen M. et al. Civil War Lexington, KY: Bluegrass Breeding Ground of Power (2011) excerpt and text search

- Hollingsworth, Randolph (2004). Lexington: Queen of the Bluegrass. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Press. ISBN 9780738524665.

- Jillson, Willard Rouse (October 1929). "The Founding of Lexington, Kentucky". Filson Club History Quarterly. 3 (5).

- Klotter, James C.; Rowland, Daniel, eds. (2012). Bluegrass Renaissance: The History and Culture of Central Kentucky, 1792–1852. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813136073. (emphasis on the architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe and "neoclassical" Lexington)

- Smith, Gerald L. Lexington Kentucky (KY) (Black America) (2002)

- Wilson, Samuel M. (January 1930). "Date of the First Settlement of Lexington, Kentucky". Filson Club History Quarterly. 4 (1).

- Wright, John D. Jr. Lexington: Heart of the Bluegrass (1994); 244pp; a history

External links

[edit]- Official website of Lexington, Kentucky

- Official website of Downtown Lexington Corporation

- Official website of the Lexington Convention and Visitors Bureau

- Lexington Kentucky: The Athens of the West, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- Downloadable PDF and Plain text versions of George Washington Ranck's 1872 book, History of Lexington, Kentucky

- Digitized images from the Ethel Williams collection on Lexington, Kentucky, 1902–1909, housed at the University of Kentucky Libraries Special Collections research Center

- Digitized images from A Review of Lexington, Kentucky, as she is: her wealth and industry, her wonderful growth and admirable enterprise, her great business concerns, her manufacturing advances, and commercial resources, housed at the University of Kentucky Libraries Special Collections Research Center