Woody Allen

Woody Allen | |

|---|---|

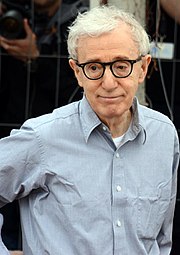

Allen at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival | |

| Born | Allan Stewart Konigsberg December 1, 1935 |

| Other names | Heywood Allen |

| Occupation(s) | Actor, author, filmmaker, comedian, playwright, musician |

| Years active | 1950–present |

| Spouses | Harlene Susan Rosen

(m. 1956; div. 1962) |

| Partners |

|

| Children |

|

| Relatives | Letty Aronson (sister) |

| Awards | See Awards and Nominations |

| Comedy career | |

| Medium | Stand-up, film, television, theatre, books |

| Genres | Observational comedy, satire, black comedy, self-deprecation, cringe comedy, deadpan |

| Signature |  |

| Website | woodyallen |

Woody Allen[1] (born Allan Stewart Konigsberg, December 1, 1935)[2] is an American actor, author, filmmaker, comedian, playwright, and musician, whose career spans more than six decades.

He worked as a comedy writer in the 1950s, writing jokes and scripts for television and publishing several books of short humor pieces. In the early 1960s, Allen began performing as a stand-up comedian, emphasizing monologues rather than traditional jokes. As a comedian, he developed the persona of an insecure, intellectual, fretful nebbish, which he maintains is quite different from his real-life personality.[3] In 2004, Comedy Central[4] ranked Allen in fourth place on a list of the 100 greatest stand-up comedians, while a UK survey ranked Allen as the third greatest comedian.[5]

By the mid-1960s Allen was writing and directing films, first specializing in slapstick comedies before moving into dramatic material influenced by European art cinema during the 1970s, and alternating between comedies and dramas to the present. He is often identified as part of the New Hollywood wave of filmmakers of the mid-1960s to late 1970s.[6] Allen often stars in his films, typically in the persona he developed as a standup. Some best-known of his over 40 films are Annie Hall (1977), Manhattan (1979), and Hannah and Her Sisters (1986). In 2007 he said Stardust Memories (1980), The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985), and Match Point (2005) were his best films.[7] Critic Roger Ebert described Allen as "a treasure of the cinema."[8]

Allen won four Academy Awards: three for Best Original Screenplay and one for Best Director (Annie Hall). He also won nine British Academy of Film and Television Arts Awards. His screenplay for Annie Hall was named the funniest screenplay by the Writers Guild of America in its list of the "101 Funniest Screenplays."[9] In 2011, PBS televised the film biography, Woody Allen: A Documentary, on the American Masters TV series.[10]

Early life

Allen was born Allan Stewart Konigsberg[2] in The Bronx. He and his sister, Letty (b. 1943) were raised in Midwood, Brooklyn.,[11] New York, the son of Nettie (née Cherry; November 8, 1906 – January 27, 2002), a bookkeeper at her family's delicatessen, and Martin Konigsberg (December 25, 1900 – January 8, 2001),[12] a jewelry engraver and waiter.[13] His family was Jewish; his grandparents immigrated from Russia and Austria, and spoke Yiddish, Hebrew, and German.[14][15] His parents were both born and raised on the Lower East Side of Manhattan.[14]

His childhood was not particularly happy; his parents did not get along, and he had a rocky relationship with his stern, temperamental mother.[16] Allen spoke German quite a bit in his early years.[17] He would later joke that when he was young he was often sent to inter-faith summer camps, where he "was savagely beaten by children of all races and creeds."[18] While attending Hebrew school for eight years, he went to Public School 99 (now the Isaac Asimov School for Science and Literature)[19] and to Midwood High School, where he graduated in 1953.[20] At that time, he lived in an apartment at 968 East 14th Street.[21] Unlike his comic persona, he was more interested in baseball than school and his strong arms ensured he was first to be picked for a team.[22][23] He impressed students with his extraordinary talent at card and magic tricks.[18]

To raise money, he wrote jokes (or "gags") for agent David O. Alber, who sold them to newspaper columnists. At the age of 17, he legally changed his name to Heywood Allen[1] and later began to call himself Woody Allen. According to Allen, his first published joke read: "Woody Allen says he ate at a restaurant that had O.P.S. prices – over people's salaries."[24] He was then earning more than both parents combined.[22] After high school, he attended New York University, studying communication and film in 1953, before dropping after failing the course "Motion Picture Production". He later briefly studied film at City College of New York in 1954, but did not finish the semester.[25] Later, he learned via self-study rather than in the classroom.[23] He eventually taught at The New School. He also studied with writing teacher Lajos Egri.[23]p.74 His status before the Selective Service System was "4-F", a medical deferment,[26] although he later claimed his actual status was "4-P", hostage.[27]

Career

Comedy writer

Allen began writing short jokes when he was 15,[28] and the following year began sending them to various Broadway writers to see if they'd be interested in buying any. He also began going by the name "Woody Allen."[29]: 539 One of those writers was Abe Burrows, coauthor of Guys and Dolls, who wrote, "Wow! His stuff was dazzling." Burrows then wrote Allen letters of introduction to Sid Caesar, Phil Silvers, and Peter Lind Hayes, who immediately sent Allen a check for just the jokes Burrows included as samples.[29]: 541

As a result of the jokes Allen mailed to various writers, he was invited, then age 19, to join the NBC Writer's Development Program in 1955, followed by a job on The NBC Comedy Hour in Los Angeles. He was later hired as a full-time writer for humorist Herb Shriner, initially earning $25 a week.[24] He began writing scripts for The Ed Sullivan Show, The Tonight Show, specials for Sid Caesar post-Caesar's Hour (1954–1957), and other television shows.[23][30]p.111 By the time he was working for Caesar, he was earning $1,500 a week; with Caesar, he worked alongside Danny Simon, whom Allen credits for helping form his writing style.[24][31] In 1962 alone he estimated that he wrote twenty thousand jokes for various comics.[29]: 533

Allen also wrote for the Candid Camera television show, and appeared in some episodes.[32][33][34] Along with that show, he wrote jokes for the Buddy Hackett sitcom Stanley and The Pat Boone Chevy Showroom. And in 1958 he cowrote a few Sid Caesar specials with Larry Gelbart.[29]: 542 After writing for many of television's leading comedians and comedy shows, Allen was gaining the reputation for being a "genius", says composer Mary Rodgers. When given an assignment for a show he would leave and come back the next day with "reams of paper", according to producer Max Liebman.[29]: 542 Similarly, after writing for Bob Hope, Hope called him "half a genius".[29]: 542

His daily writing routine could go as long as fifteen hours, and he could focus and write anywhere necessary. Dick Cavett was amazed at Allen's capacity to write: "He can go to a typewriter after breakfast and sit there until the sun sets and his head is pounding, interrupting work only for coffee and a brief walk, and then spend the whole evening working."[29]: 551 When Allen wrote for other comedians, they would use eight out of ten of his jokes. When he began performing as a stand-up, he was much more selective, typically using only one out of ten jokes. He estimated that to prepare for a 30-minute show, he spent six months of intensive writing.[29]: 551 He enjoyed writing, however, despite the work: "Nothing makes me happier than to tear open a ream of paper. And I can't wait to fill it! I love to do it."[29]: 551

Allen started writing short stories and cartoon captions for magazines such as The New Yorker; he was inspired by the tradition of New Yorker humorists S. J. Perelman, George S. Kaufman, Robert Benchley and Max Shulman, whose material he modernized.[35][36][37][38][39] Allen has published four collections of his short pieces and plays.[40][41] These are Getting Even, Without Feathers, Side Effects, and Mere Anarchy. His early comic fiction was heavily influenced by the zany, pun-ridden humour of S.J. Perelman. In 2010, Allen released digital spoken word versions of his four books, in which he reads 73 short story selections from his work and for which he was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album.[42]

Stand-up comedian

From 1960 to 1969, Allen performed as a stand-up comedian to supplement his comedy writing. His contemporaries during those years included Lenny Bruce, Shelley Berman, the team of Mike Nichols and Elaine May, and Mort Sahl, his personal favorite. Comedy historian Gerald Nachman notes that Allen, while not the first to do stand-up, would eventually have greater impact than all the others in the 1960s, and would redefine the meaning of stand-up comedy: "He helped turn it into biting, brutally honest satirical commentary on the cultural and psychological tenor of the times."[29]: 525

After Allen was taken under the wing of his new manager, Jack Rollins, who had recently discovered Nichols and May, Rollins suggested he perform his written jokes as a stand-up. Allen was resistant at first, but after seeing Mort Sahl on stage, he felt safer to give it a try: "I'd never had the nerve to talk about it before. Then Mort Sahl came along with a whole new style of humor, opening up vistas for people like me."[29]: 545 Allen made his professional stage debut at the Blue Angel nightclub in Manhattan in October 1960, where comedian Shelley Berman introduced him as a young television writer who would perform his own material.[29]: 545

His early stand-up shows with his different style of humor were not always well received or understood by his audiences. Unlike other comedians, Allen spoke to his audiences in a low-key conversational style, often appearing to be searching for words, although his style was well rehearsed. He acted "normal", dressed casually, and made no attempt to project a stage "personality". And he did not improvise: "I put very little premium on improvisation," he told Studs Terkel.[29]: 532 His jokes were created from life experiences, and typically presented with a dead serious demeanor which made them funnier: "I don't think my family liked me. They put a live teddy bear in my crib."[29]: 533

The subjects of his jokes were rarely topical, political or even socially relevant. Unlike Bruce and Sahl, he did not discuss current events such as civil rights, women's rights, the Cold War, or Vietnam. And although he was described as a "classic nebbish", he did not tell Jewish jokes. Comedy screenwriter Larry Gelbart compared Allen's style to Elaine May: "He just styled himself completely after her," he said.[29]: 546 Like Nichols and May, he often made fun of intellectuals.

Television talk show host Dick Cavett, who was among the minority who quickly appreciated Allen's unique style, recalls seeing the audience at the Blue Angel mostly ignore Allen's monologue: "I recognized immediately that there was no young comedian in the country in the same class with him for sheer brilliance of jokes, and I resented the fact that the audience was too dumb to realize what they were getting."[29]: 550 It was his subdued stage presence, while initially unappreciated, that eventually became one of Allen's strongest traits, explains Nachman: "The utter absence of showbiz veneer and shtick was the best shtick any comedian had ever devised. This uneasy onstage naturalness became a trademark."[29]: 530 When he was finally noticed by the media, writers like New York Times' Arthur Gelb would describe Allen's nebbish quality as being "Chaplinesque" and "refreshing".

Allen developed a neurotic, nervous, and intellectual persona for his stand-up routine, a successful move that secured regular gigs for him in nightclubs and on television. Allen brought innovation to the comedy monologue genre and his stand-up comedy would be considered influential.[43] Allen first appeared on the Tonight Show in November 1963. He subsequently released three LP albums of live nightclub recordings: the self-titled Woody Allen (1964), Volume 2 (1965), and The Third Woody Allen Album (1968) recorded at a fund-raiser for Senator Eugene McCarthy's presidential run.

Allen had his own TV show beginning in 1965, called The Woody Allen Show, where he would intersperse humor with interviews of famous people, including Rev. Billy Graham[44] and William F. Buckley.[45][46] He also performed stand-up comedy on other venues, including a 1965 TV show in the U.K., while he was there during the filming of Casino Royale.[47] In 1971 Allen hosted The Tonight Show, which included as guests Bob Hope and James Coco.[48]

Playwright

In 1966, Allen wrote the play Don't Drink the Water. The play starred Lou Jacobi, Kay Medford, Anita Gillette and Allen's future movie co-star Tony Roberts.[49] A film adaptation of the play, directed by Howard Morris, was released in 1969, starring Jackie Gleason. Because he was not particularly happy with the 1969 film version of his play, in 1994, Allen directed and starred in a second version for television, with Michael J. Fox and Mayim Bialik.[50]

The next play Allen wrote for Broadway was Play It Again, Sam, in which he also starred. The play opened on February 12, 1969, and ran for 453 performances. It featured Diane Keaton and Roberts.[51] The play was significant to Keaton's budding career, and she has stated she was in "awe" of Allen even before auditioning for her role, which was the first time she met him.[52] During an interview in 2013, Keaton stated that she "fell in love with him right away," adding, "I wanted to be his girlfriend so I did something about it."[53] After co-starring alongside Allen in the subsequent film version of Play It Again, Sam, she would later co-star in Sleeper, Love and Death, Interiors, Manhattan and Annie Hall. "He showed me the ropes and I followed his lead. He is the most disciplined person I know. He works very hard," Keaton has stated.[53] "I find the same thing sexy in a man now as I always have: humor. I love it when they are funny. It's to die for."[54]

For its March 21, 1969, issue, Life featured Allen on its cover.[55] In 1981, his play The Floating Light Bulb premiered on Broadway and ran for 65 performances.[56] While receiving mixed reviews, it gave an autobiographical insight into Allen's childhood, specifically his fascination with magic tricks. He has written several one-act plays, including Riverside Drive and Old Saybrook exploring well-known Allen themes.[57][58]

On October 20, 2011, Allen's one-act play Honeymoon Motel opened as part of a larger piece entitled Relatively Speaking on Broadway, with two other one-act plays, one by Ethan Coen and one by Elaine May.[59]

Early films

His first movie was the Charles K. Feldman production What's New Pussycat? in 1965, for which he wrote the screenplay.[10] He was disappointed with the final product, which inspired him to direct every film that he would later write.[10] Allen's first directorial effort was What's Up, Tiger Lily? (1966, co-written with Mickey Rose), in which an existing Japanese spy movie—Kokusai himitsu keisatsu: Kagi no kagi (1965), "International Secret Police: Key of Keys"—was redubbed in English by Allen and friends with fresh new, comic dialogue. In 1967, Allen played Jimmy Bond in the 007 spoof Casino Royale.

Allen directed, starred in, and co-wrote (with Mickey Rose) Take the Money and Run in 1969, which received positive reviews. He later signed a deal with United Artists to produce several films. Those films eventually became Bananas (1971, co-written with Rose), Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* (1972), Sleeper (1973), and Love and Death (1975).[10] Sleeper was the first of four films where the screenplay was co-written by Allen and Marshall Brickman.

I don't like meeting heroes. There's nobody I want to meet and nobody I want to work with—I'd rather work with Diane Keaton than anyone—she's absolutely great, a natural.

Woody Allen, Rolling Stone interview (1976)[28]

In 1972, Allen wrote and starred in the film version of Play It Again, Sam, directed by Herbert Ross and co-starring Diane Keaton. In 1976, he starred as cashier Howard Prince, in The Front, directed by Martin Ritt. The Front was a humorous and poignant account of Hollywood blacklisting during the 1950s; Ritt, screenwriter Walter Bernstein, and three of Allen's cast-mates, Samuel "Zero" Mostel, Herschel Bernardi, and Lloyd Gough, had all themselves been actual blacklisting victims.[citation needed]

Then came two of Allen's most popular films. Annie Hall won four Academy Awards in 1977, including Best Picture, Best Actress in a Leading Role for Diane Keaton, Best Original Screenplay and Best Director for Woody Allen. Annie Hall set the standard for modern romantic comedy and ignited a fashion trend with the clothes worn by Diane Keaton in the film. In an interview with journalist Katie Couric, Keaton does not deny that Allen wrote the part for her and about her.[60] She also explains that Allen wrote the part based on aspects of her personality at the time:

Of course I recognized myself in the roles [Woody Allen] wrote. I mean, in Annie Hall (1977) particularly. I was this sort of novice who had lots of feelings but didn't know how to express herself, and I see that in Annie. I think Woody used a kind of essential quality that he found in me at that time, and I'm glad he did because it worked really well in the movie.[54]

The film is ranked at No. 35 on the American Film Institute's "100 Best Movies" and at No. 4 on the AFI list of "100 Best Comedies."

Manhattan (1979), is a black-and-white film often viewed as an homage to New York City. As in many Allen films, the main protagonists are upper-middle class writers and academics. The love–hate opinion of cerebral persons found in Manhattan is characteristic of many of Allen's movies, including Crimes and Misdemeanors and Annie Hall. Manhattan focuses on the complicated relationship between middle-aged Isaac Davis (Allen) with 17-year-old Tracy (Mariel Hemingway), and co-stars Diane Keaton.

Keaton, who made eight movies with Allen during her career, tries to explain why his films are unique:

He just has a mind like nobody else. He's bold. He's got a lot of strength, a lot of courage in terms of his work. And that is what it takes to do something really unique. Along with a genius imagination.[60]

Between Annie Hall and Manhattan, Allen wrote and directed the dark drama Interiors (1978), in the style of Swedish director Ingmar Bergman, one of Allen's chief influences. Interiors represented a departure from Allen's "early, funny" comedies (a line from 1980's Stardust Memories).

1980s

Allen's 1980s films, even the comedies, have somber and philosophical undertones, with their influences being the works of European directors, specifically Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini. Stardust Memories was based on 8½, which it parodies, and Wild Strawberries. A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy was adapted from Smiles of a Summer Night. In Hannah and Her Sisters, part of the film's structure and background is borrowed from Fanny and Alexander. Amarcord inspired Radio Days. September resembles Autumn Sonata. Allen uses many elements from Wild Strawberries. In Crimes and Misdemeanors, Allen references a scene from Wild Strawberries.[61]

Stardust Memories (1980) features Sandy Bates, a successful filmmaker played by Allen, who expresses resentment and scorn for his fans. Overcome by the recent death of a friend from illness, the character states, "I don't want to make funny movies any more" and a running gag has various people (including visiting space aliens) telling Bates that they appreciate his films, "especially the early, funny ones."[62] Allen believes this to be one of his best films.[63]

Mia's a good actress who can play many different roles. She has a very good range, and can play serious to comic roles. She's also very photogenic, very beautiful on screen. She's just a good realistic actress . . . and no matter how strange and daring it is, she does it well.

Woody Allen (1993)[64]

A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy (1982) was the first of 13 movies Allen made starring Mia Farrow, who stepped into Diane Keaton's role when Keaton was shooting Reds.[65] He next produced a vividly idiosyncratic tragi-comical parody of documentary, Zelig, in which he starred as a Leonard Zelig, man who has the ability to transform his appearance to that of the people who surround him.[66]

Allen combined tragic and comic elements in such films as Hannah and Her Sisters (1985) and Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989), in which he tells two stories that connect at the end. He also made three films about show business: Broadway Danny Rose, in which he plays a New York show business agent, The Purple Rose of Cairo, a movie that shows the importance of the cinema during the Depression through the character of the naive Cecilia, and Radio Days, a film about his childhood in Brooklyn and the importance of the radio. The film co-starred Farrow in a part Allen wrote specifically for her.[64]

The Purple Rose of Cairo was named by Time as one of the 100 best films of all time[67] and Allen described it as one of his three best films, along with Stardust Memories and Match Point[68] (Allen defines them as "best" not in terms of quality but because they came closest to his vision). In 1989, Allen teamed with directors Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese to make New York Stories, an anthology film about New Yorkers. Allen's short, Oedipus Wrecks, is about a neurotic lawyer and his critical mother. His short pleased critics, but New York Stories bombed at the box office.[69][70]

1990s

His 1991 film Shadows and Fog is a black-and-white homage to the German expressionists and features the music of Kurt Weill.[71] Allen then made his critically acclaimed comedy-drama Husbands and Wives (1992), which received two Oscar nominations: Best Supporting Actress for Judy Davis and Best Original Screenplay for Allen. His film Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993) combined suspense with dark comedy and marked the return of Diane Keaton, Alan Alda and Anjelica Huston.

He returned to lighter movies like Bullets over Broadway (1994), which earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Director, followed by a musical, Everyone Says I Love You (1996). The singing and dancing scenes in Everyone Says I Love You are similar to musicals starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. The comedy Mighty Aphrodite (1995), in which Greek drama plays a large role, won an Academy Award for Mira Sorvino. Allen's 1999 jazz-based comedy-drama Sweet and Lowdown was nominated for two Academy Awards for Sean Penn (Best Actor) and Samantha Morton (Best Supporting Actress). In contrast to these lighter movies, Allen veered into darker satire toward the end of the decade with Deconstructing Harry (1997) and Celebrity (1998).

During this decade, Allen also starred in the television film The Sunshine Boys (1995), based on the Neil Simon play of the same name.[72]

Allen made one sitcom "appearance" via telephone on the show Just Shoot Me! in a 1997 episode, "My Dinner with Woody" which paid tribute to several of his films. Allen provided the lead voice in the 1998 animated film Antz, which featured many actors he had worked with and Allen's character was similar to his earlier neurotic roles.[73]

2000s

Small Time Crooks (2000) was Allen's first film with the DreamWorks studio and represented a change in direction: Allen began giving more interviews and made an attempt to return to his slapstick roots. The film is similar to the 1942 film Larceny, Inc. (from a play by S.J. Perelman).[74] Allen never commented on whether this was deliberate or if his film was in any way inspired by it. Small Time Crooks was a relative financial success, grossing over $17 million domestically but Allen's next four films foundered at the box office, including Allen's most costly film, The Curse of the Jade Scorpion (with a budget of $26 million). Hollywood Ending, Anything Else, and Melinda and Melinda were given "rotten" ratings from film-review website Rotten Tomatoes and each earned less than $4 million domestically.[75] Some critics claimed that Allen's early 2000s films were subpar and expressed concern that Allen's best years were behind him.[76] Others were less harsh; reviewing the little-liked Melinda and Melinda, Roger Ebert wrote, "I cannot escape the suspicion that if Woody had never made a previous film, if each new one was Woody's Sundance debut, it would get a better reception. His reputation is not a dead shark but an albatross, which with admirable economy Allen has arranged for the critics to carry around their own necks."[77] Woody gave his godson Quincy Rose a small part in Melinda and Melinda.

Allen was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2001.[78]

Match Point (2005) was one of Allen's most successful films of the decade, garnering positive reviews.[79] Set in London, it starred Jonathan Rhys Meyers and Scarlett Johansson. It is markedly darker than Allen's first four films with DreamWorks SKG. In Match Point, Allen shifted focus from the intellectual upper class of New York to the moneyed upper class of London. The film earned more than $23 million domestically (more than any of his films in nearly 20 years) and over $62 million in international box office sales.[80] Match Point earned Allen his first Academy Award nomination since 1998, for Best Writing – Original Screenplay, with directing and writing nominations at the Golden Globes, his first Globe nominations since 1987. In a 2006 interview with Premiere Magazine, Allen stated this was the best film he has ever made.[81]

Allen returned to London to film Scoop, which also starred Johansson, Hugh Jackman, Ian McShane, Kevin McNally and Allen himself. The film was released on July 28, 2006, and received mixed reviews. He filmed Cassandra's Dream in London. Cassandra's Dream was released in November 2007, and stars Colin Farrell, Ewan McGregor and Tom Wilkinson.

After finishing his third London film, Allen headed to Spain. He reached an agreement to film Vicky Cristina Barcelona in Avilés, Barcelona and Oviedo, where shooting started on July 9, 2007. The movie stars Scarlett Johansson, Javier Bardem, Rebecca Hall and Penélope Cruz.[82][83] Speaking of his experience there, Allen said: "I'm delighted at being able to work with Mediapro and make a film in Spain, a country which has become so special to me." Vicky Cristina Barcelona was well received, winning Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy at the Golden Globe awards. Penélope Cruz received the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role in the film.

Allen has said that he "survives" on the European market. Audiences there tend to be more receptive to his films, particularly in Spain, France and Italy—countries where he has a large audience (joked about in Hollywood Ending). "In the United States things have changed a lot, and it's hard to make good small films now," Allen said in a 2004 interview. "The avaricious studios couldn't care less about good films—if they get a good film they're twice as happy but money-making films are their goal. They only want these $100 million pictures that make $500 million."[84]

In April 2008, he began filming a story focused more toward older audiences starring Larry David, Patricia Clarkson[85][better source needed] and Evan Rachel Wood.[86] Released in 2009, Whatever Works,[87] described as a dark comedy, follows the story of a botched suicide attempt turned messy love triangle. Whatever Works was written by Allen in the 1970s and the character played by Larry David was written for Zero Mostel, who died the year Annie Hall came out.

2010s

You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger, filmed in London, stars Antonio Banderas, Josh Brolin, Anthony Hopkins, Anupam Kher, Freida Pinto and Naomi Watts. Filming started in July 2009. It was released theatrically in the US on September 23, 2010, following a Cannes debut in May 2010, and a screening at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 12, 2010. Allen announced that his next film would be titled Midnight in Paris,[88] starring Adrien Brody, Owen Wilson, Marion Cotillard, Rachel McAdams, Kathy Bates, Michael Sheen, Gad Elmaleh and Carla Bruni, the First Lady of France at the time of production. The film follows a young engaged couple in Paris who see their lives transformed. It debuted at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival on May 12, 2011. Allen said he wanted to "show the city emotionally," during the press conference. "I just wanted it to be the way I saw Paris – Paris through my eyes," he added.[89] Critically acclaimed, the film was considered by some a mark for his return to form.[90] Midnight in Paris won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. His next film, To Rome with Love, was a Rome-set comedy released in 2012. The film was structured in four vignettes featuring dialogue in both Italian and English. It marked Allen's return to acting since his last role in Scoop.[91]

Blue Jasmine debuted in July 2013.[92] The film is set in San Francisco and New York, and stars Alec Baldwin, Cate Blanchett, Louis C.K., Andrew Dice Clay, Sally Hawkins, and Peter Sarsgaard.[93] Opened to critical acclaim, the film earned Allen another Academy Award nomination for Best Original Screenplay,[94] and Blanchett went to receive the Academy Award for Best Actress.[95] In 2013, in Nice, France, Allen shot the romantic comedy Magic in the Moonlight, set in the 1920s on the French Riviera[96] and starring Colin Firth and Emma Stone.[97] Allen co-stars with John Turturro in Fading Gigolo, written and directed by Turturro, which premiered in September 2013.[98]

It’s really cool to work with a director who’s done so much, because he knows exactly what he wants. The fact that he does one shot for an entire scene—[and] this could be a scene with eight people and one to two takes—it gives you a level of confidence... he’s very empowering.

Blake Lively, on acting in Café Society[99]

From July through August 2014, Allen filmed the mystery drama Irrational Man in Newport, Rhode Island, with Joaquin Phoenix, Emma Stone, Parker Posey and Jamie Blackley.[100] Allen has said that this film, as well as the next three he has planned, have the financing and full support of Sony Pictures Classics.[101] Allen's next film, Café Society, starred an ensemble cast, including Jesse Eisenberg, Kristen Stewart, and Blake Lively.[102] Bruce Willis was set to co-star, but was replaced by Steve Carell during filming.[103] The film is distributed by Amazon Studios, and opened the 2016 Cannes Film Festival on May 11, 2016, marking the third time Allen has opened the festival.[104]

Future projects

For many years, Allen wanted to make a film about the origins of jazz in New Orleans. The film, tentatively titled American Blues, would follow the vastly different careers of Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet. Allen stated that the film would cost between $80 and $100 million and is therefore unlikely to be made.[105]

On January 14, 2015, it was announced Allen will write and direct a TV series of half-hour episodes for Amazon Studios, marking the first time he has developed a television show. It will be available exclusively on Amazon Prime Instant Video, and Amazon Studios has already ordered a full season. Allen said of the series, "I don't know how I got into this. I have no ideas and I'm not sure where to begin. My guess is that Roy Price [the head of Amazon Studios] will regret this."[106][107][108] At the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, Allen said, in reference to his upcoming Amazon show, "It was a catastrophic mistake. I don't know what I'm doing. I'm floundering. I expect this to be a cosmic embarrassment."[109]

Amazon Video debuted Allen's first television series production on September 30, 2016. The series is a comedy which takes place during the 1960s. It focuses on the life of a suburban family after a surprise visitor creates chaos among them. Titled Crisis in Six Scenes, it stars Allen alongside Elaine May and Miley Cyrus. Cyrus plays the part of a radical hippie fugitive who sells marijuana.[110][111]

In September 2016, Allen started filming his next project, set in 1950's Coney Island and stars Kate Winslet and Justin Timberlake.[112]

Theatre

While best known for his films, Allen has enjoyed a successful career in theatre, starting as early as 1960, when he wrote sketches for the revue From A to Z. His first great success was Don't Drink the Water, which opened in 1968, and ran for 598 performances for almost two years on Broadway. His success continued with Play It Again, Sam, which opened in 1969, starring Allen and Diane Keaton. The show played for 453 performances and was nominated for three Tony Awards, although none of the nominations were for Allen's writing or acting.[113]

In the 1970s, Allen wrote a number of one-act plays, most notably God and Death, which were published in his 1975 collection Without Feathers.

In 1981, Allen's play The Floating Light Bulb opened on Broadway. The play was a critical success and a commercial flop. Despite two Tony Award nominations, a Tony win for the acting of Brian Backer (who won the 1981 Theater World Award and a Drama Desk Award for his work), the play only ran for 62 performances.[114]

After a long hiatus from the stage, Allen returned to the theatre in 1995, with the one-act Central Park West, an installment in an evening of theatre known as Death Defying Acts that was also made up of new work by David Mamet and Elaine May.[115]

For the next few years, Allen had no direct involvement with the stage, yet notable productions of his work were staged. A production of God was staged at The Bank of Brazil Cultural Center in Rio de Janeiro,[116] and theatrical adaptations of Allen's films Bullets Over Broadway[117] and September[118] were produced in Italy and France, respectively, without Allen's involvement. In 1997, rumors of Allen returning to the theatre to write a starring role for his wife Soon-Yi Previn turned out to be false.[119]

In 2003, Allen finally returned to the stage with Writer's Block, an evening of two one-acts—Old Saybrook and Riverside Drive—that played Off-Broadway. The production marked the stage-directing debut for Allen.[120] The production sold out the entire run.[121]

Also in 2003, reports of Allen writing the book for a musical based on Bullets Over Broadway surfaced, and it opened in New York in 2014.[122] The musical closed on August 24, 2014, after 156 performances and 33 previews.[123] In 2004, Allen's first full-length play since 1981, A Second Hand Memory,[124] was directed by Allen and enjoyed an extended run Off-Broadway.[121]

In June 2007, it was announced that Allen would make two more creative debuts in the theatre, directing a work that he did not write and directing an opera — a reinterpretation of Puccini's Gianni Schicchi for the Los Angeles Opera[125]—which debuted at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion on September 6, 2008.[126] Commenting on his direction of the opera, Allen said, "I have no idea what I'm doing." His production of the opera opened the Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto, Italy, in June 2009.[127]

In October 2011, Woody Allen's one-act play called Honeymoon Motel premiered as one in a series of one act plays on Broadway titled Relatively Speaking.[128] Also contributing to the plays are Elaine May and Ethan Coen with John Turturro directing.[129]

It was announced in February 2012 that Allen would adapt Bullets over Broadway into a Broadway musical. It opened on April 10, 2014 and closed on August 24, 2014.[130]

Music

Allen is a passionate fan of jazz, featured prominently in the soundtracks to his films. He began playing the clarinet as a child and took his stage name from clarinetist Woody Herman.[131] He has performed publicly at least since the late 1960s, notably with the Preservation Hall Jazz Band on the soundtrack of Sleeper.[132] One of his earliest televised performances was on The Dick Cavett Show on October 20, 1971.[133]

Woody Allen and his New Orleans Jazz Band have been playing each Monday evening at Manhattan's Carlyle Hotel for many years[134] (as of 2011,[135] specializing in classic New Orleans jazz from the early twentieth century).[136] He plays songs by Sidney Bechet, George Lewis, Johnny Dodds, Jimmie Noone and Louis Armstrong.[137] The documentary film Wild Man Blues (directed by Barbara Kopple) documents a 1996 European tour by Allen and his band, as well as his relationship with Previn. The band has released two CDs: The Bunk Project (1993) and the soundtrack of Wild Man Blues (1997). In a 2011 review of a concert by Allen's jazz band, critic Kirk Silsbee of the L.A. Times suggested that Allen should be regarded as a competent musical hobbyist with a sincere appreciation for early jazz: "Allen's clarinet won't make anyone forget Sidney Bechet, Barney Bigard or Evan Christopher. His piping tone and strings of staccato notes can't approximate melodic or lyrical phrasing. Still his earnestness and the obvious regard he has for traditional jazz counts for something."[138]

Allen and his band played the Montreal International Jazz Festival on two consecutive nights in June 2008.[139]

Works about Allen

Apart from Wild Man Blues, directed by Barbara Kopple, there are other documentaries featuring Woody Allen, including the 2002 cable-television documentary Woody Allen: a Life in Film, directed by Time film critic Richard Schickel, which interlaces interviews of Allen with clips of his films, and Meetin' WA, a short interview of Allen by French director Jean-Luc Godard. In 2011 the PBS series American Masters co-produced a comprehensive documentary about him, Woody Allen: a Documentary directed by Robert B. Weide.[10]

Eric Lax authored the book Woody Allen: A Biography.[140] From 1976 to 1984, Stuart Hample wrote and drew Inside Woody Allen, a comic strip based on Allen's film persona.[141]

Personal life

Marriages and romantic relationships

Allen has had three wives: Harlene Rosen (1956–1959), Louise Lasser (1966–1970) and Soon-Yi Previn (1997–present). Though he had a 12-year on and off romantic relationship with actress Mia Farrow, the two never married. Allen also had long-term romantic relationships with Stacey Nelkin and Diane Keaton.

Harlene Rosen

At age 20, Allen married 17-year-old Harlene Rosen.[142] The marriage lasted from 1956 to 1959.[143] Time stated that the years were "nettling" and "unsettling."[142]

Rosen, whom Allen referred to in his standup act as "the Dread Mrs. Allen", sued him for defamation due to comments at a TV appearance shortly after their divorce. Allen tells a different story on his mid-1960s standup album Standup Comic. In his act, Allen said that Rosen sued him because of a joke he made in an interview. Rosen had been sexually assaulted outside her apartment and according to Allen, the newspapers reported that she "had been violated". In the interview, Allen said, "Knowing my ex-wife, it probably wasn't a moving violation." In an interview on The Dick Cavett Show, Allen brought up the incident again where he repeated his comments and stated that the sum for which he was sued was "$1 million."[144]

Louise Lasser

Allen married Louise Lasser in 1966. They divorced in 1970, and Allen did not marry again until 1997. Lasser appeared in three Allen films shortly after the divorce—Take the Money and Run, Bananas, and Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* (*But Were Afraid to Ask)—and later briefly appeared in Stardust Memories.

Diane Keaton

In 1969, Allen cast Diane Keaton in his Broadway show, Play It Again, Sam. During the run she and Allen became romantically involved and although they broke up after a year, she continued to star in a number of his films, including Sleeper as a futuristic poet and Love and Death as a composite character based on the novels of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. Annie Hall was very important in Allen and Keaton's careers. It is said that the role was written for her, as Diane Keaton's birth name was Diane Hall. She then starred in Interiors as a poet, followed by Manhattan. In 1987, she had a cameo as a nightclub singer in Radio Days, and was chosen to replace Mia Farrow in the co-starring role for Manhattan Murder Mystery after Allen and Farrow began having troubles with their personal and working relationship while making this film. Keaton has not worked with Allen since Manhattan Murder Mystery. Since the end of their romantic relationship, Keaton and Allen remain close friends.[145]

Stacey Nelkin

The film Manhattan is said by the Los Angeles Times[146] to be widely known to have been based on his romantic relationship with actress Stacey Nelkin. Her bit part in Annie Hall ended up on the cutting room floor, and their relationship, though never publicly acknowledged by Allen, reportedly began when she was 17, and a student at New York's Stuyvesant High School.[147][148][149] Nelkin played the role of Rita in Woody Allen's 1994 film, Bullets over Broadway.

Mia Farrow

Around 1980, Allen began a twelve-year relationship with actress Mia Farrow, who starred in 13 of his films from 1982 to 1992. They never married or lived together, but lived near one another on opposite sides of Central Park in Manhattan.[150]

In December 1991, after ten years together, Allen formally adopted two of Farrow's own previously adopted children, Dylan, 7, and Moses, 13. Farrow told the court that Allen was an “excellent father,” although the children lived with her. The New York Times wrote that Allen and Farrow "are constantly in touch with each other, and not many fathers spend as much time with their children as Allen does."[150] He tried to be with them every day.[151]

The following month, January 1992, Farrow was at Allen's home and came across nude photos of her adopted daughter, 21-year-old Soon-Yi Previn, which were taken by Allen. Farrow realized that Allen was having an affair with Previn.[152] This resulted in a bitter breakup of the long-term relationship between Allen and Farrow, with Previn then moving in with Allen.[153] In her autobiography, What Falls Away, Farrow says that Allen admitted to the relationship with Soon-Yi.[154]

Soon-Yi Previn

Soon-Yi Previn is the adopted daughter of Farrow and her former husband, composer André Previn; she is now Allen's wife. Previn was born in Korea and was abandoned in the slums of Seoul. Farrow and Previn adopted her in 1978, at which time a bone scan determined she was between five and seven years old.[151][152]

Allen and Previn began a relationship while Allen was still in a relationship with Previn's mother, Mia Farrow. After discovering the affair in 1992, Farrow's relationship with Allen ended acrimoniously. Allen and Previn continued their relationship, with Previn moving in with Allen.[153] They married on December 23, 1997,[155] and have adopted two daughters.[156]

Children

Allen and Mia Farrow, though unmarried, jointly adopted two children: Dylan Farrow (who changed her name to Eliza and later to Malone) and Moshe Farrow (known as Moses); they also had one biological child, Satchel Farrow (known as Ronan). Ronan's paternity came into question, however, after Farrow claimed in 2013 that he might in fact be the biological child of Frank Sinatra, her first husband, with whom she "never really split up," she said.[157] Allen did not adopt any of Farrow's other children, including Soon-Yi.

Following Allen's separation from Farrow, and after a bitter custody battle, she won custody of their children. Allen was denied visitation rights with Malone and could see Ronan only under supervision. Moses, who was then 15, chose not to see Allen but by age 36 he had become estranged from his mother and reestablished his relationship with Allen and his sister.[158] Farrow tried to have Allen's two adoptions with her nullified, but the court decided in Allen's favor and he continues to be their legal father.[159]

Sex abuse allegations

Allen and Farrow engaged in a heated and emotionally damaging custody battle after they broke up in January 1992, during which time Farrow alleged that he once sexually abused their daughter, which he has denied. In August 1992, Allen visited his children at Farrow's home by mutual arrangement while she went shopping.[160] Dylan, his seven-year-old daughter, later told Mia Farrow that he molested her during that visit.[161] Farrow filed a complaint with the police.[151] Dylan said that the abuse took place in the attic. In 2014, Dylan's older brother, Moses, denied that abuse in the attic was possible, saying that there were several people present in the house during Allen's entire visit and "no one, not my father or sister, was off in any private spaces".[162]

The case was closed in 1993 after a seven-month probe by a police-appointed medical team concluded that Dylan had not been molested.[163] Among the reasons cited for the team's conclusion were the contradictory statements made by Dylan and that her statements had a "rehearsed quality".[163] The judge eventually found that the sex abuse charges were inconclusive.[164] In addition, investigators with the New York Department of Social Services closed their own 14-month investigation after their similar conclusion, namely that: "No credible evidence was found that the child named in this report has been abused or maltreated."[165] Allen was interviewed by 60 Minutes a few months following the allegation, when he described the custody battle, heated exchanges, and the allegations.[166]

In February 2014, Dylan Farrow repeated the allegation in an open letter published by Nicholas Kristof, one of Farrow's friends,[167] in his New York Times blog. She alleged that Allen had treated her in a way that made her physically uncomfortable "for as long as [she] could remember", citing occasions when he got in bed with her in his underwear.[161] Allen again repeated his denial of the allegation, calling them "untrue and disgraceful", and followed with his own response in The New York Times.[168][169] Dylan's brother, Moses, currently a family therapist, told People magazine, "Of course Woody did not molest my sister... She loved him and looked forward to seeing him when he would visit." He claimed that their mother had manipulated her children into hating Allen as "a vengeful way to pay him back for falling in love with Soon-Yi."[170][171] Dylan denies she was ever coached by her mother and stands by her allegations. Several of Farrow's other children have spoken out in support of Dylan.[170]

Psychoanalysis

Allen spent over 37 years undergoing psychoanalysis. Some of his films, such as Annie Hall, jokingly include references to psychoanalysis. Moment Magazine says, "It drove his self-absorbed work." Allen's biographer, John Baxter, wrote, "Allen obviously found analysis stimulating, even exciting."[172] Allen says his psychoanalysis ended around the time he began his relationship with Previn, although he is still claustrophobic and agoraphobic.[173]

Allen has described himself as being a "militant Freudian atheist".[174]

Theatrical works

In addition to directing, writing, and acting in films, Allen has written and performed in a number of Broadway theatre productions.

| Year | Title | Credit | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | From A to Z | Writer (book) | Plymouth Theatre |

| 1966 | Don't Drink the Water | Writer | Coconut Grove Playhouse, Florida |

| 1969 | Play It Again, Sam | Writer, Performer (Allan Felix) | Broadhurst Theatre[175] |

| 1975 | God | Writer | — |

| 1975 | Death | Writer | — |

| 1981 | The Floating Light Bulb | Writer | Vivian Beaumont Theater |

| 1995 | Central Park West | Writer | Variety Arts Theatre |

| 2003 | Old Saybrook | Writer, Director | Atlantic Theatre Company |

| 2003 | Riverside Drive | Writer, Director | Atlantic Theatre Company |

| 2004 | A Second Hand Memory | Writer, Director | Atlantic Theater Company |

| 2011 | "Honeymoon Motel" (segment of 3-part anthology play Relatively Speaking) | Writer | Brooks Atkinson Theatre |

| 2014 | Bullets Over Broadway | Writer (Book) | St. James Theatre |

Filmography

See also

References

- ^ a b Woody Allen at Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b Lax, Eric (1991). "Woody Allen: A Biography". Woody Allen: A Biography. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

Woody Allen was born in Brooklyn, New York, in the spring of 1952, when Allan Stewart Konigsberg, who was born in the Bronx on December 1, 1935, settled on the name as a suitable cover.

- ^ Gross, Terry (2009–12). "Woody Allen: Blending Real Life With Fiction". Fresh Air. Retrieved April 7, 2012.

- ^ Comedy Central's 100 Greatest Stand-Ups of all Time. Everything2 (April 18, 2004). Retrieved May 4, 2012.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (January 2, 2005). "Cook tops poll of comedy greats". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Newton, Michael (January 13, 2012). "Woody Allen: cinema's great experimentalist". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

In the 1970s, Allen looked irreverent, hip, a part of the New Hollywood generation. In an age of 'auteurs', he was the auteur personified, the writer, director and star of his films, active in the editing, choosing the soundtrack, initiating the projects

- ^ Lax, Eric (November 18, 2007). Conversations With Woody Allen. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-41533-5. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Midnight in Paris :: rogerebert.com :: Reviews". Rogerebert.suntimes.com. May 25, 2011. Retrieved June 20, 2011.

- ^ McNary, Dave (November 11, 2015). "'Annie Hall' Named Funniest Screenplay by WGA Members". Variety.

- ^ a b c d e Weide, Robert B. (Director). Woody Allen: A Documentary (Television). PBS, November 21, 2011. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ Newman, Andy; Kilgannon, Corey (June 5, 2002). "Curse of the Jaded Audience: Woody Allen, in Art and Life". The New York Times. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

'I think he's slacked off the last few movies', said Norman Brown, 70, a retired draftsman from Mr. Allen's old neighborhood, Midwood, Brooklyn, who said he had seen nearly all of Mr. Allen's 33 films.

- ^ "Martin Konigsberg". Variety. January 16, 2001. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- ^ "Woody Allen Biography (1935–)". Filmreference.com. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ a b "The religion of Woody Allen, director and actor". Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- ^ Encyclopedia of American Jewish history – Stephen Harlan Norwood, Eunice G. Pollack – Google Books. Books.google.ca. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- ^ "The Unruly Life of Woody Allen". The New York Times. March 5, 2000. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ "The Religious Affiliation of Woody Allen, Influential Director and Actor". Adherents.com. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ a b "Woody Allen : Comedian Profile". Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- ^ Meade, Marion (2000). The unruly life of Woody Allen: a biography. New York: Scribner. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-684-83374-3. OCLC 42291110.

- ^ The principal of P.S. 99 was Mrs. Eudora Fletcher; Allen has used her name for characters in several of his films.

- ^ Woody Allen visits the house in Weide's documentary

- ^ a b "Woody Allen on Life, Films And Whatever Works". June 15, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Lax, Eric (December 26, 2000). Woody Allen: a biography (2nd ed.). Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80985-9. OCLC 45714340.

- ^ a b c "Woody Allen: Rabbit Running". Time. July 3, 1972. Retrieved June 8, 2007.

- ^ Schmitz, Paul (December 31, 2011). "Lessons from famous college dropouts". cnn.com. CNN. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ Woody Allen

- ^ Woody Allen - Standup Comic

- ^ a b Kelley, Ken. Rolling Stone, "A Conversation with the Real Woody Allen", July 1, 1976 pp. 34-40

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Nachman, Gerald (2003). Seriously Funny The Rebel Comedians of the 1950s and 1960s. New York, NY: Pantheon Books. p. 659. ISBN 9780375410307. OCLC 50339527.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help); Invalid|script-title=: missing prefix (help) - ^ "IMDb: Woody Allen". Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ Bernstein, Adam. "TV Comedy Writer Danny Simon Dies". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ "Woody Allen Candid Camera Must See". YouTube. February 15, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ O'Connor, John J. (February 17, 1987). "TV Reviews; 'Candid Camera' Marks 40 Years With a Special". The New York Times. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ "Woody Allen = IMDb". Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Daniele Luttazzi, preface to the Italian translation of Allen's trilogy Complete prose, ISBN 978-88-452-3307-4 p. 7 quote: Archived August 19, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ^ Allen, W. (October 24, 2004) "I Appreciate George S. Kaufman", The New York Times.

- ^ Woody Allen: Rabbit Running. Time. July 3, 1972. pp. 5–6 quote: "I never had a teacher who made the least impression on me, if you ask me who are my heroes, the answer is simple and truthful: George S. Kaufman and the Marx Brothers."

- ^ Michiko Kakutani (1995) "Woody Allen". This interview is part I of the series The Art of Humor, published by Paris Review 37(136):200 (Fall, 1995). [1]

- ^ Galef, David (February 21, 2003). "Getting Even: Literary Posterity and the Case for Woody Allen". South Atlantic Review. 64 (2). South Atlantic Modern Language Association: 146–160. doi:10.2307/3201987. JSTOR 3201987.

- ^ "The Insanity Defense – The Complete Prose". Amazon.com. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ "Amazon.com: Woody Allen plays: Books". Amazon. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (July 20, 2010). "Immortalized by Not Dying Woody Allen Goes Digital". The New York Times. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ^ Scanzi, Andrea (2002). "Man on the moon, interview with comedian Daniele Luttazzi" (in Italian). Il Mucchio Selvaggio.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Billy Graham on Woody Allen Show, 1967, 2-part video, 10 min.

- ^ Finch, John; Cox Michael. Granada Television -The First Generation, Manchester University Press (2003) p. 113

- ^ "William F. Buckley on Woody Allen Show, 1967, video, 9 min.

- ^ Woody Allen performing on British TV, 1965

- ^ Woody Allen guest hosts The Tonight Show", 1971

- ^ "Don't Drink the Water – Broadway Play – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ^ Leonard, John (December 12, 1994). "Made-for-TV Woody". New York Magazine. (Google Books). p. 92.

- ^ "Play It Again, Sam – Broadway Play – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ^ Keaton, Diane (October 20, 2011). "Diane Keaton: The Big Picture". Vogue. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ^ a b "Actress Diane Keaton Talks About Woody Allen, Her Career and Personal Life", Netquake, June 2, 2013

- ^ a b "Personal quotes by Diane Keaton, IMDB

- ^ "1969 LIFE Magazine Cover Art". Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ "The Floating Light Bulb – Broadway Play – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ^ Rich, Frank (April 28, 1981). "Stage: 'Light Bulb', By Woody Allen". The New York Times. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ^ Sullivan, Dan (January 12, 1987). "Stage Review : Few Laughs In Allen's 'Light Bulb'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ^ "Each Family, Tortured in Its Own Way" by Charles Isherwood, The New York Times, October 20, 2011

- ^ a b "Annie Hall Interview with Diane Keaton by Katie Couric" on YouTube, video interview, 2 min.

- ^ Wilmington, Michael (October 22, 1989). "rectors (Page 2 of 2) COMMENTARY : Woody Allen Keeps the Faith : 'Crimes and Misdemeanors' tears down the wall between his serious and comic sides (Page 2)". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ "Stardust Memories review". Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ Kamp, David (November 18, 2007). "Woody Talks". The New York Times. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Allen, Woody. Woody Allen on Woody Allen, Grove Press (1993) p. 133

- ^ Morgan, David. "The films of Woody Allen". CBS News. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ Carby, Vincent (July 17, 1983). "Zelig (1983) WOODY ALLEN CONTINUES TO REFINE HIS CINEMATIC ART". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (January 15, 2010). "Best Movies of All Time". Time. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ Matloff, Jason. "Woody Allen Speaks!". Premiere Magazine. Archived from the original on March 17, 2006. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ^ "Box Office Information for New York Stories". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (March 12, 1989). "FILM VIEW; Anthologies Can Be A Bargain". The New York Times. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ Dowd, A.A. (July 26, 2013). "Woody does German Expressionism in Shadows And Fog". The A.V. Club. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ Evans, Greg (December 21, 1997). "Review: 'The Sunshine Boys'". Variety. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ Clinton, Paul (October 2, 1998). "Review: Woody Allen still Woody in 'Antz'". CNN. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ Robert Osborne of Turner Classic Movies on June 15, 2006

- ^ "Woody Allen – Rotten Tomatoes Celebrity Profile". Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ "Melinda and Melinda review (2004) Woody Allen – Qwipster's Movie Reviews". Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ Roger Ebert's Movie Yearbook 2007. Google Books. November 1, 2006. ISBN 978-0-7407-6157-7. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter A" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ "Match Point Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved December 30, 2011.

- ^ "Box Office Mojo – People Index". Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ Matloff, Jason (February 2006). "Woody Allen's European Vacation". Premiere. 19 (5): 98–101.

I think it turned out to be the best film I've ever made.

- ^ "Woody Allen's Next Star: Penelope Cruz – Celebrity Gossip". FOX News. February 1, 2007. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ Hopewell, John (January 2, 2006). "Spain woos Woody". Variety. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ Garfield, Simon (August 8, 2004). "Why I love London". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ "Watch out for our Emma in Woody Allen's next movie". Daily Mail. London. March 7, 2008. Retrieved March 8, 2008.

- ^ "Larry David, Evan Rachel Wood to star in Woody Allen's next movie". Hollywood Insider. Archived from the original on February 18, 2008. Retrieved February 7, 2008.

- ^ Mark Harris (May 24, 2009). "Twilight of the Tummlers". New York. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

- ^ McNary, Dave (April 22, 2010). "Woody Allen reveals details of upcoming pic". Variety. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Bagnetto, Laura Angela (May 12, 2011). "Woody Allen's film featuring Carla Bruni opens Cannes Film Festival". Radio France Internationale. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Zacharek, Stephanie (May 19, 2011). "Review: Woody Allen Returns to Form for Real This Time with Midnight in Paris. Movieline. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Hickman, Angela (May 9, 2011). "Woody Allen adds himself to the cast of his next picture". National Post. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Brody, Richard (July 25, 2013). "Woody Allen's 'Blue Jasmine'". The New Yorker. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Kilday, Gregg (June 4, 2012). "Believe It: Woody Allen's Next Movie Features Louis C.K., Andrew Dice Clay". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ "Blue Jasmine (2013)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Nominees for the 86th Academy Awards | Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences. Oscars.org (August 24, 2012). Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ Miller, William (August 4, 2013). "Woody Allen 2014 Film Update: More Images from Antibes and Nice, France". The Woody Allen Pages. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Magic in Moonlight. Internet Movie Database. 2014.

- ^ Bailey, Cameron (undated). "Fading Gigolo". Toronto International Film Festival. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ "Blake Lively Talks Working with Woody Allen...", Hamptons, June 29, 2016

- ^ Goldstein, Meredith; Shanahan, Mark (July 8, 2014). "Emma Stone stays in Rhode Island for Woody Allen film". The Boston Globe. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (July 20, 2014). "A Master of Illusion Endures". The New York Times. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ Fleming Jr., Mike (March 9, 2015). "Jesse Eisenberg, Bruce Willis, Kristen Stewart To Star In Next Woody Allen Pic". Deadline.com. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ^ Jaafar, Ali; Hipes, Patrick (August 28, 2015). "Steve Carell Replacing Bruce Willis In Woody Allen Movie". Deadline.com. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ^ Chang, Justin; Keslassy, Elsa (March 29, 2016). "Cannes: Woody Allen's 'Cafe Society' to Open Film Festival". Variety. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ Lax, Eric; Allen, Woody (2007). Conversations with Woody Allen – His Films, the Movies and Moviemaking. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 315–316. ISBN 978-1400031498.

- ^ Weinstein, Shelli (January 13, 2015). "Woody Allen to Create His First Television Series for Amazon". Variety. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Steel, Emily (January 13, 2015). "Amazon Signs Woody Allen to Write and Direct TV Series". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- ^ Massa, Annie; Soper, Spencer; Palmeri, Chris (January 13, 2015). "Amazon's Woody Allen Hiring Underscores Video Risk". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Zeitchik, Steven (May 15, 2015). "Cannes 2015: Woody Allen Sings a Bleak Tune". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ "Miley Cyrus Explains Why She’s in Awe of Woody Allen: 'He’s Never Fake'". Vanity Fair, Sept. 16, 2016

- ^ "Watch First Clip From Woody Allen's 'Crisis in Six Scenes' TV Show", Rolling Stone, August 8, 2016

- ^ "Kate Winslet Joining Woody Allen's Next Film". Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- ^ The Broadway League (March 14, 1970). "Internet Broadway Database: Play It Again, Sam Production Credits". Ibdb. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ The Broadway League. "Internet Broadway Database: The Floating Light Bulb Production Credits". Ibdb.com. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ "Death Defying Acts and No One Shall Be Immune – David Mamet Society". Mamet.eserver.org. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ "Allen's God Shows Up in Rio, Jan. 16". Playbill. January 15, 1998. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ "Playbill News: Woody Allen Adaptation Debuts at Italian Theater Festival, Aug. 1". Playbill. July 31, 1998. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ "Playbill News: Stage Version of Woody Allen's September to Bow in France, Sept. 16". Playbill. September 15, 1999. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ "NY Post: Woody Allen Penning Play for Soon-Yi Previn". Playbill. December 31, 1997. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ "Playbill News: Woody Allen's Writer's Block, with Neuwirth and Reiser, Opens Off Broadway May 15". Playbill. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ a b "Playbill News: Two Weeks Added to Woody Allen's New Play, Second Hand Memory, at Off-Bway's Atlantic". Playbill. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ "Playbill News: Work Continues of Musical Version of Bullets Over Broadway". Playbill. July 17, 2003. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ Gans, Andrew and Hetrick, Adam. "Curtain Comes Down on Woody Allen Musical Bullets Over Broadway " playbill.com, August 24, 2014

- ^ "Playbill News: Woody Allen Directs His Second Hand Memory, Opening Nov. 22 Off-Broadway". Playbill. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ "Woody Allen makes debut at opera". BBC News. BBC. September 8, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony (September 7, 2008). "Puccini With a Sprinkling of Woody Allen Whimsy". The New York Times. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (May 7, 2009). "Woody Allen's Puccini Goes to Spoleto". The New York Times. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- ^ Relatively Speaking relativelyspeakingbroadway.com. Retrieved January 4, 2012

- ^ Isherwood, Charles (October 20, 2011). "Each Family, Tortured in Its Own Way". The New York Times.

- ^ Healy, Patrick (February 23, 2012). "'Bullets Over Broadway' Is Heading There". The New York Times. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- ^ Gonzalez, Victor (September 19, 2011). "Woody Allen and His New Orleans Jazz Band Announce Miami Beach Haunukkah Show". Miami New Times. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Stafford, Jeff. "Sleeper". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Galbraith, Stuart, IV (February 21, 2006). "The Dick Cavett Show: Comic Legends DVD Talk Review of the DVD Video". dvdtalk.com. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Olsen, Erik (October 19, 2005). "New York City: Catch Woody Allen at the Cafe Carlyle". gadling.com. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Alcantara, Krisanne (March 3, 2011). "Woody Allen Plays Jazz at the Carlyle Hotel". nearsay.com. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ "New Orleans Trombone, Jerry Zigmont – Jazz Trombone, Eddy Davis & His New Orleans Jazz Band featuring Woody Allen, Cafe Carlyle, Woody Allen Band". Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ Woody Allen en concert ce lundi à Monaco, Monaco-Matin, December 28, 2014

- ^ Silsbee, Kirk (December 30, 2011). "Jazz review: Woody Allen's New Orleans band at Royce Hall". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "Concert: Woody Allen And His New Orleans Jazz Band – Festival International de Jazz de Montreal". Montreal Jazz Festival. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Lax, Eric (1991). Woody Allen: a biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394583495. OCLC 22662351.

- ^ Hample, Stuart (October 19, 2009). "How I turned Woody Allen into a comic strip". The Guardian. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ a b "Woody Allen: Rabbit Running". Time. July 3, 1972. p. 3. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- ^ Certificate of Registry of Marriage of Allan Stewart Konigsberg and Harlene Susan Rosen, March 15, 1956, retrieved from findmypast.com.

- ^ "Dick & Woody discuss particle physics". Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ^ Q&A: Diane Keaton. CBS News. February 18, 2004. Retrieved February 21, 2006.

- ^ [dead link] "Stacey Nelkin". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 19, 2010.

- ^ Fox, Julian (1996). Woody: Movies from Manhattan. Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0879516925.

- ^ Baxter, John (1998). Woody Allen: A Biography. New York: Carroll & Graf. pp. 226, 248, 249, 250, 253, 273–74, 385, 416. ISBN 978-0786708079.

- ^ Bailey, Peter J. (2001). The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. p. 61. ISBN 978-0813190419.

- ^ a b Lax, Eric (February 24, 1991). "Woody and Mia: A New York Story". The New York Times. p. 5 of 12. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

They are not married, neither do they live together; their apartments face each other across Central Park.

- ^ a b c Callahan, Maureen (January 8, 2012). "The quiet victory of Mia & the kids Woody left behind". New York Post.

...Soon-Yi, whom Farrow had adopted with ex-husband Previn in 1978.... [W]hen Farrow got her back to the States, a bone scan determined she was somewhere between 5 and 7 years old.

- ^ a b Orth, Maureen (November 1992). "Mia's Story". Vanity Fair. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

Nobody knows how old Soon-Yi really is. Without ever seeing her, Korean officials put her age down as seven on her passport. A bone scan in the U.S. put her age at between five and seven. In the family, Soon-Yi is considered to have turned 20 this year [1992], on October 8.

- ^ a b Tait, Robert (May 5, 2016). "Woody Allen 'immune' to criticism over affair with former partner's daughter". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ^ Gliatto, Tom. "A Family Affair". People. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Fields-Meyer, Thomas (January 12, 1998). "Love in Venice". People. Time Inc. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- ^ Woody Allen, Soon-Yi Previn Still Going Strong 20 Years After Mia Farrow Scandal Carey Vanderborg, International Business Times, August 23, 2012

- ^ "Exclusive: Mia Farrow and Eight of Her Children Speak Out on Their Lives, Frank Sinatra, and the Scandals They've Endured". Vanity Fair. October 2, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ Marks, Peter. "Allen Loses to Farrow in Bitter Custody Battle". The New York Times. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Robert B. Weide (January 27, 2014). "The Woody Allen Allegations: Not So Fast". The Daily Beast.

Moses Farrow, now 36, .... has been estranged from Mia for several years. During a recent conversation, he spoke of "finally seeing the reality" of Frog Hollow and used the term "brainwashing" without hesitation. He recently reestablished contact with Allen and is currently enjoying a renewed relationship with him and Soon-Yi.

- ^ "Moses Farrow defends Woody Allen over child abuse accusations", The Guardian, Feb. 5, 2015

- ^ a b http://kristof.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/02/01/an-open-letter-from-dylan-farrow/?_r=0

- ^ "Dylan Farrow's Brother Moses Says Mia Farrow, Not Woody Allen Was Abusive", ABC News, Feb. 5, 2014

- ^ a b Pérez-Peña, Richard (May 4, 1993). "Doctor Cites Inconsistencies In Dylan Farrow's Statement". The New York Times. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Brozan, Nadine (May 13, 1994). "Chronicle". The New York Times. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Pérez-Peña, Richard (October 26, 1993). "Agency Drops Abuse Inquiry in Allen Case". The New York Times. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ “Woody Allen defends himself on 60 Minutes in '92”, CBS, November 22, 1992

- ^ "Dylan Farrow's Story". NYTimes.com. February 1, 2014. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ^ Staff (February 3, 2014). "Woody Allen rejects 'untrue and disgraceful' sex abuse claims". Agence France-Presse (via Yahoo! News). Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Moore, Suzanne (February 3, 2014). "The kangaroo court of Twitter is no place to judge Woody Allen". The Guardian. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ a b Dennis, Alicia. "Dylan Farrow's Brother Moses Defends Woody Allen", People magazine, Feb. 5, 2014. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Rothma, Michael (February 5, 2014). Dylan's brother, Ronan Farrow, supported his sister and her decision to speak out against Woody Allen in a tweet that read, "I love and support my sister and I think her words speak for themselves." [2] [3] "Dylan Farrow's Brother Moses Says Mia Farrow, Not Woody Allen Was Abusive". ABC News. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ^ "Moment Mag". Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Biskind, Peter (December 2005). "Reconstructing Woody". Vanity Fair. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ "YouTube". May 19, 2008. Retrieved May 19, 2008.

- ^ "Woody Allen Biography (1935–)". filmreference.com. Retrieved February 28, 2008.

External links

- Official website

- Woody Allen at IMDb

- Woody Allen at AllMovie

- Woody Allen at the TCM Movie Database

- Woody Allen at the Internet Broadway Database

- Woody Allen on National Public Radio June 15, 2009

- Please use a more specific IOBDB template. See the template documentation for available templates.

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Template:Worldcat id

- Woody Allen collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- Woody Allen collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Woody Allen

- 1935 births

- 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American musicians

- 21st-century American dramatists and playwrights

- 21st-century American male actors

- 21st-century American musicians

- American atheists

- American film directors

- American film producers

- American humorists

- American satirists

- American jazz clarinetists

- American male film actors

- American male musicians

- American male screenwriters

- American people of Austrian-Jewish descent

- American people of Russian-Jewish descent

- American short story writers

- American stand-up comedians

- Antinatalists

- Ashkenazi Jews

- Best Directing Academy Award winners

- Best Director BAFTA Award winners

- Best Original Screenplay Academy Award winners

- Cecil B. DeMille Award Golden Globe winners

- César Award winners

- Comedians from New York

- David di Donatello winners

- Directors Guild of America Award winners

- Dixieland clarinetists

- English-language film directors

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Film directors from New York City

- Independent Spirit Award winners

- Jewish American male actors

- Jewish American musicians

- Jewish American writers

- Jewish atheists

- Jewish comedy and humor

- Jewish dramatists and playwrights

- Jewish male comedians

- Jews and Judaism in New York City

- Living people

- Male actors from New York City

- O. Henry Award winners

- Entertainers from the Bronx

- Secular Jews

- Tisch School of the Arts alumni

- Writers Guild of America Award winners

- Writers from Brooklyn

- American male dramatists and playwrights

- American male short story writers

- Midwood High School alumni