Opioid use disorder: Difference between revisions

trimmed |

consistent citation formatting |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{Infobox medical condition (new) |

{{Infobox medical condition (new) |

||

| name = Opioid use disorder |

| name = Opioid use disorder |

||

| synonyms = Opioid addiction,<ref name=FDA2016/> problematic opioid use,<ref name=FDA2016>{{cite web|title=Press Announcements – FDA approves first buprenorphine implant for treatment of opioid dependence|url=https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm503719.htm|website=www.fda.gov| |

| synonyms = Opioid addiction,<ref name=FDA2016/> problematic opioid use,<ref name=FDA2016>{{cite web|title=Press Announcements – FDA approves first buprenorphine implant for treatment of opioid dependence|url=https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm503719.htm|website=www.fda.gov|access-date=16 March 2017|language=en|date=26 May 2016}}</ref> opioid abuse,<ref>{{cite book|title=Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction.|date=2004|publisher=Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US)|location=Rockville (MD)|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64237/|language=en|chapter=3 Patient Assessment}}</ref> opioid dependence<ref name=CDC2018Def/> |

||

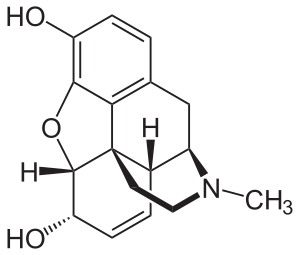

| image = Morphin - Morphine.svg |

| image = Morphin - Morphine.svg |

||

| width = 300 |

| width = 300 |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

| prevention = |

| prevention = |

||

| treatment = [[Opioid replacement therapy]], [[Addiction#Behavioral therapy|behavioral therapy]], [[twelve-step program]]s, take home [[naloxone]]<ref name=BMJ2017Re/><ref name=Sam2017Tx/><ref name=Mc2016/> |

| treatment = [[Opioid replacement therapy]], [[Addiction#Behavioral therapy|behavioral therapy]], [[twelve-step program]]s, take home [[naloxone]]<ref name=BMJ2017Re/><ref name=Sam2017Tx/><ref name=Mc2016/> |

||

| medication = [[Buprenorphine]], [[methadone]], [[naltrexone]]<ref name=BMJ2017Re/><ref name=Shar2016>{{cite journal| |

| medication = [[Buprenorphine]], [[methadone]], [[naltrexone]]<ref name=BMJ2017Re/><ref name=Shar2016>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sharma B, Bruner A, Barnett G, Fishman M | title = Opioid Use Disorders | journal = Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America | volume = 25 | issue = 3 | pages = 473–87 | date = July 2016 | pmid = 27338968 | pmc = 4920977 | doi = 10.1016/j.chc.2016.03.002 }}</ref> |

||

| prognosis = |

| prognosis = |

||

| frequency = c. 0.4%<ref name=DSM5/> |

| frequency = c. 0.4%<ref name=DSM5/> |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

<!-- Definition and symptoms --> |

<!-- Definition and symptoms --> |

||

'''Opioid use disorder''' is a problematic pattern of [[opioid]] use that causes significant impairment or distress.<ref name=CDC2018Def>{{cite web |title=Commonly Used Terms |url=https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/opioids/terms.html |website=www.cdc.gov | |

'''Opioid use disorder''' is a problematic pattern of [[opioid]] use that causes significant impairment or distress.<ref name=CDC2018Def>{{cite web |title=Commonly Used Terms |url=https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/opioids/terms.html |website=www.cdc.gov |access-date=16 July 2018 |language=en-us |date=29 August 2017}}</ref> Symptoms of the disorder include a strong desire to use opioids, increased [[drug tolerance|tolerance]] to opioids, failure to fulfill obligations, trouble reducing use, and [[withdrawal syndrome]] with discontinuation.<ref name=DSM5/><ref name=Sam2015>{{Cite web|url=https://www.samhsa.gov/disorders/substance-use|title=Substance Use Disorders| author = Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration }}</ref> Opioid withdrawal symptoms may include nausea, muscle aches, diarrhea, trouble sleeping, or a low mood.<ref name=Sam2015/> [[Addiction]] and [[drug dependence|dependence]] are components of a [[substance use disorder]].<ref name="Brain disease"/> Complications may include [[opioid overdose]], [[suicide]], [[HIV/AIDS]], [[hepatitis C]], marriage problems, or unemployment.<ref name=DSM5/><ref name=Sam2015/> |

||

<!-- Cause and diagnosis --> |

<!-- Cause and diagnosis --> |

||

Opioids include substances such as [[heroin]], [[morphine]], [[fentanyl]], [[codeine]], [[oxycodone]], and [[hydrocodone]].<ref name=Sam2015/><ref name=ACOG2017>{{cite web |title=Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy |url=https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/Opioid-Use-and-Opioid-Use-Disorder-in-Pregnancy |website=ACOG | |

Opioids include substances such as [[heroin]], [[morphine]], [[fentanyl]], [[codeine]], [[oxycodone]], and [[hydrocodone]].<ref name=Sam2015/><ref name=ACOG2017>{{cite web |title=Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy |url=https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/Opioid-Use-and-Opioid-Use-Disorder-in-Pregnancy |website=ACOG |access-date=16 July 2018 |date=August 2017}}</ref> In the United States, a majority of heroin users begin by using prescription opioids.<ref name=NIH2018Risk>{{cite web |title=Prescription opioid use is a risk factor for heroin use |url=https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/relationship-between-prescription-drug-heroin-abuse/prescription-opioid-use-risk-factor-heroin-use |website=National Institute on Drug Abuse |access-date=16 July 2018 |language=en}}</ref><ref name=NYT2018>{{cite news|last1=Hughes|first1=Evan|title=The Pain Hustlers|url=https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/05/02/magazine/money-issue-insys-opioids-kickbacks.html?hp&action=click&pgtype=Homepage&clickSource=story-heading&module=photo-spot-region®ion=top-news&WT.nav=top-news|access-date=3 May 2018|publisher=New York Times|date=2 May 2018}}</ref> These can be bought illegally or prescribed.<ref name=NIH2018Risk/> Diagnosis may be based on criteria by the [[American Psychiatric Association]] in the [[Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders|DSM-5]].<ref name=DSM5>{{citation|author=American Psychiatric Association|year=2013|title=Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.)|location=Arlington|publisher=American Psychiatric Publishing|pages=540–546|isbn=978-0890425558}}</ref> If more than two of eleven criteria are present during a year the diagnosis is said to be present.<ref name=DSM5/> If a person is appropriately taking opioids for a medical condition issues of tolerance and withdrawal do not apply.<ref name=DSM5/> |

||

<!-- Treatment --> |

<!-- Treatment --> |

||

Individuals with an opioid use disorders are often treated with [[opioid replacement therapy]] using [[methadone]] or [[buprenorphine]].<ref name=BMJ2017Re/> Being on such treatment reduces the risk of death.<ref name=BMJ2017Re>{{cite journal| |

Individuals with an opioid use disorders are often treated with [[opioid replacement therapy]] using [[methadone]] or [[buprenorphine]].<ref name=BMJ2017Re/> Being on such treatment reduces the risk of death.<ref name=BMJ2017Re>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Wiessing L, Ferri M, Pastor-Barriuso R | title = Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies | journal = Bmj | volume = 357 | pages = j1550 | date = April 2017 | pmid = 28446428 | pmc = 5421454 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.j1550 }}</ref> Additionally, individuals may benefit from [[cognitive behavioral therapy]], other forms of support from mental health professionals such as individual or group therapy, [[twelve-step program]]s, and other peer support programs.<ref name=Sam2017Tx>{{Cite web|url=https://www.samhsa.gov/treatment/substance-use-disorders|title=Treatment for Substance Use Disorders| authors =Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration }}</ref> The medication [[naltrexone]] may also be useful to prevent relapse.<ref name=Shar2016/> [[Naloxone]] is useful for treating an [[opioid overdose]] and giving those at risk naloxone to take home is beneficial.<ref name=Mc2016>{{cite journal | vauthors = McDonald R, Strang J | title = Are take-home naloxone programmes effective? Systematic review utilizing application of the Bradford Hill criteria | journal = Addiction | volume = 111 | issue = 7 | pages = 1177–87 | date = July 2016 | pmid = 27028542 | pmc = 5071734 | doi = 10.1111/add.13326 }}</ref> |

||

<!-- Epidemiology and culture --> |

<!-- Epidemiology and culture --> |

||

In 2013, opioid use disorders affected about 0.4% of people.<ref name=DSM5/> As of 2015, it was estimated that about 16 million people worldwide have been affected at one point in their lives.<ref>{{cite journal| |

In 2013, opioid use disorders affected about 0.4% of people.<ref name=DSM5/> As of 2015, it was estimated that about 16 million people worldwide have been affected at one point in their lives.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Schuckit MA | title = Treatment of Opioid-Use Disorders | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 375 | issue = 4 | pages = 357–68 | date = July 2016 | pmid = 27464203 | doi = 10.1056/NEJMra1604339 }}</ref> Long term opioid use occurs in about 4% of people following their use for trauma or surgery related pain.<ref name=Moh2018>{{cite journal | vauthors = Mohamadi A, Chan JJ, Lian J, Wright CL, Marin AM, Rodriguez EK, von Keudell A, Nazarian A | title = Risk Factors and Pooled Rate of Prolonged Opioid Use Following Trauma or Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-(Regression) Analysis | journal = The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume | volume = 100 | issue = 15 | pages = 1332–1340 | date = August 2018 | pmid = 30063596 | doi = 10.2106/JBJS.17.01239 }}</ref> Onset is often in young adulthood.<ref name=DSM5/> Males are affected more often than females.<ref name=DSM5/> It resulted in 122,000 deaths worldwide in 2015,<ref name=GBD2015>{{cite journal | vauthors = | title = Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 | journal = Lancet | volume = 388 | issue = 10053 | pages = 1459–1544 | date = October 2016 | pmid = 27733281 | pmc = 5388903 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1 }}</ref> up from 18,000 deaths in 1990.<ref name=GDB2013/> In the United States during 2016, there were more than 42,000 deaths due to opioid overdose, of which more than 15,000 were the result of heroin use.<ref>{{cite web|title=Data Brief 294. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2016|url=https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db294_table.pdf|website=CDC|access-date=18 May 2018}}</ref> |

||

{{TOC limit}} |

{{TOC limit}} |

||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

===Withdrawal=== |

===Withdrawal=== |

||

Onset of [[Drug withdrawal|withdrawal]] from opioids depends on which opioid was used last.<ref name=Rie2009/> With heroin this typically occurs 5 hours after use, while with methadone it might not occur until 2 days later.<ref name=Rie2009>{{cite book |last1=Ries |first1=Richard K. |last2=Miller |first2=Shannon C. |last3=Fiellin |first3=David A. |title=Principles of Addiction Medicine |date=2009 |publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins |isbn=9780781774772 |pages=593–594 |url=https://books.google.ca/books?id=j6GGBud8DXcC&pg=PA593 |language=en}}</ref> The length of time that major symptoms occur also depends on the opioid used.<ref name=Rie2009/> For heroin symptoms are typically greatest at two to four days and can last for up to two weeks.<ref name=Rie2009/><ref>{{cite journal | |

Onset of [[Drug withdrawal|withdrawal]] from opioids depends on which opioid was used last.<ref name=Rie2009/> With heroin this typically occurs 5 hours after use, while with methadone it might not occur until 2 days later.<ref name=Rie2009>{{cite book |last1=Ries |first1=Richard K. |last2=Miller |first2=Shannon C. |last3=Fiellin |first3=David A. | name-list-format = vanc |title=Principles of Addiction Medicine |date=2009 |publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins |isbn=9780781774772 |pages=593–594 |url=https://books.google.ca/books?id=j6GGBud8DXcC&pg=PA593 |language=en}}</ref> The length of time that major symptoms occur also depends on the opioid used.<ref name=Rie2009/> For heroin symptoms are typically greatest at two to four days and can last for up to two weeks.<ref name=Rie2009/><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Rahimi-Movaghar A, Gholami J, Amato L, Hoseinie L, Yousefi-Nooraie R, Amin-Esmaeili M | title = Pharmacological therapies for management of opium withdrawal | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 6 | pages = CD007522 | date = June 2018 | pmid = 29929212 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD007522.pub2 }}</ref> Less significant symptoms may remain for an even longer period, in which case it is known as a [[protracted abstinence syndrome]].<ref name=Rie2009/> |

||

*Agitation<ref name=DSM5/> |

*Agitation<ref name=DSM5/> |

||

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

==Cause== |

==Cause== |

||

Opioid use disorder can develop as a result of [[self medication|self-medication]], though this is controversial.<ref name="pmid21514751">{{cite journal |title=An examination of psychiatric comorbidities as a function of gender and substance type within an inpatient substance use treatment program | |

Opioid use disorder can develop as a result of [[self medication|self-medication]], though this is controversial.<ref name="pmid21514751">{{cite journal | vauthors = Chen KW, Banducci AN, Guller L, Macatee RJ, Lavelle A, Daughters SB, Lejuez CW | title = An examination of psychiatric comorbidities as a function of gender and substance type within an inpatient substance use treatment program | journal = Drug and Alcohol Dependence | volume = 118 | issue = 2-3 | pages = 92–9 | date = November 2011 | pmid = 21514751 | pmc = 3188332 | doi = 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.003 }}</ref> Scoring systems have been derived to assess the likelihood of opiate addiction in chronic pain patients.<ref name="pmid16336480">{{cite journal | vauthors = Webster LR, Webster RM | title = Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the Opioid Risk Tool | journal = Pain Medicine | volume = 6 | issue = 6 | pages = 432–42 | year = 2005 | pmid = 16336480 | doi = 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00072.x }}</ref> Prescription opioids are the source of nearly half of misused opioids and the majority of these are initiated for trauma or surgery pain management.<ref name=Moh2018 /> |

||

According to position papers on the treatment of opioid dependence published by the [[United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime]] and the [[World Health Organization]], care providers should not treat opioid use disorder as the result of a weak [[Moral character|character]] or [[will (philosophy)|will]].<ref name=WHOsub2004>{{cite book |title=Substitution maintenance therapy in the management of opioid dependence and HIV/AIDS prevention |publisher=World Health Organization |year=2004 |isbn=92-4-159115-3 |url=http://whqlibdoc.who.int/unaids/2004/9241591153_eng.pdf}}</ref><ref name=WHOmain>{{cite web|title=Treatment of opioid dependence|url=http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/idu/position_paper_substitution_opioid/en/index.html|publisher=WHO|date=2004| |

According to position papers on the treatment of opioid dependence published by the [[United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime]] and the [[World Health Organization]], care providers should not treat opioid use disorder as the result of a weak [[Moral character|character]] or [[will (philosophy)|will]].<ref name=WHOsub2004>{{cite book |title=Substitution maintenance therapy in the management of opioid dependence and HIV/AIDS prevention |publisher=World Health Organization |year=2004 |isbn=92-4-159115-3 |url=http://whqlibdoc.who.int/unaids/2004/9241591153_eng.pdf}}</ref><ref name=WHOmain>{{cite web|title=Treatment of opioid dependence|url=http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/idu/position_paper_substitution_opioid/en/index.html|publisher=WHO|date=2004|access-date=28 August 2016}}{{update after|2018|3|7}}</ref> Additionally, [[detoxification]] alone does not constitute adequate treatment. |

||

==Mechanism== |

==Mechanism== |

||

| Line 103: | Line 103: | ||

===Addiction=== |

===Addiction=== |

||

[[Addiction]] is a [[brain disorder]] characterized by compulsive drug use despite adverse consequences.<ref name="Brain disease">{{cite journal | vauthors = Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT | title = Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction | journal = |

[[Addiction]] is a [[brain disorder]] characterized by compulsive drug use despite adverse consequences.<ref name="Brain disease">{{cite journal | vauthors = Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT | title = Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 374 | issue = 4 | pages = 363–71 | date = January 2016 | pmid = 26816013 | doi = 10.1056/NEJMra1511480 | quote = Addiction: A term used to indicate the most severe, chronic stage of substance-use disorder, in which there is a substantial loss of self-control, as indicated by compulsive drug taking despite the desire to stop taking the drug. In the DSM-5, the term addiction is synonymous with the classification of severe substance-use disorder. }}</ref><ref name="Cellular basis" /><ref name="Addiction glossary">{{cite book |vauthors=Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE |veditors=Sydor A, Brown RY | title = Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience | year = 2009 | publisher = McGraw-Hill Medical | location = New York | isbn = 9780071481274 | pages = 364–375| edition = 2nd | chapter = Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders}}</ref><ref name="Nestler Labs Glossary">{{cite web|title=Glossary of Terms | url=http://neuroscience.mssm.edu/nestler/glossary.html | website=Mount Sinai School of Medicine | publisher=Department of Neuroscience | access-date=9 February 2015}}</ref> Addiction is a component of a [[substance use disorder]] and represents the most severe form of the disorder.<ref name="Brain disease" /> |

||

Overexpression of the [[gene transcription factor]] [[ΔFosB]] in the [[nucleus accumbens]] plays a crucial role in the development of an addiction to opioids and other addictive drugs by [[reward sensitization|sensitizing drug reward]] and amplifying compulsive drug-seeking behavior.<ref name="Cellular basis">{{cite journal | |

Overexpression of the [[gene transcription factor]] [[ΔFosB]] in the [[nucleus accumbens]] plays a crucial role in the development of an addiction to opioids and other addictive drugs by [[reward sensitization|sensitizing drug reward]] and amplifying compulsive drug-seeking behavior.<ref name="Cellular basis">{{cite journal | vauthors = Nestler EJ | title = Cellular basis of memory for addiction | journal = Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience | volume = 15 | issue = 4 | pages = 431–43 | date = December 2013 | pmid = 24459410 | pmc = 3898681 | doi = | quote = DESPITE THE IMPORTANCE OF NUMEROUS PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS, AT ITS CORE, DRUG ADDICTION INVOLVES A BIOLOGICAL PROCESS }}</ref><ref name="Nestler" /><ref name="Natural and drug addictions" /><ref name="What the ΔFosB?">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ruffle JK | title = Molecular neurobiology of addiction: what's all the (Δ)FosB about? | journal = The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse | volume = 40 | issue = 6 | pages = 428–37 | date = November 2014 | pmid = 25083822 | doi = 10.3109/00952990.2014.933840 }}</ref> Like other [[addictive drug]]s, overuse of opioids leads to increased ΔFosB expression in the [[nucleus accumbens]].<ref name="Nestler">{{cite journal | vauthors = Robison AJ, Nestler EJ | title = Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction | journal = Nature Reviews. Neuroscience | volume = 12 | issue = 11 | pages = 623–37 | date = October 2011 | pmid = 21989194 | pmc = 3272277 | doi = 10.1038/nrn3111 }}</ref><ref name="Natural and drug addictions">{{cite journal | vauthors = Olsen CM | title = Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions | journal = Neuropharmacology | volume = 61 | issue = 7 | pages = 1109–22 | date = December 2011 | pmid = 21459101 | pmc = 3139704 | doi = 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010 }}</ref><ref name="What the ΔFosB?" /><ref name="ΔFosB reward">{{cite journal | vauthors = Blum K, Werner T, Carnes S, Carnes P, Bowirrat A, Giordano J, Oscar-Berman M, Gold M | title = Sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll: hypothesizing common mesolimbic activation as a function of reward gene polymorphisms | journal = Journal of Psychoactive Drugs | volume = 44 | issue = 1 | pages = 38–55 | year = 2012 | pmid = 22641964 | pmc = 4040958 | doi = 10.1080/02791072.2012.662112 }}</ref> Opioids affect [[dopamine]] [[neurotransmission]] in the nucleus accumbens via the disinhibition of dopaminergic pathways as a result of inhibiting the [[GABA]]-based projections to the [[ventral tegmental area]] (VTA) from the [[rostromedial tegmental nucleus]] (RMTg), which negatively modulate dopamine neurotransmission.<ref name="VTA tail">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bourdy R, Barrot M | title = A new control center for dopaminergic systems: pulling the VTA by the tail | journal = Trends in Neurosciences | volume = 35 | issue = 11 | pages = 681–90 | date = November 2012 | pmid = 22824232 | doi = 10.1016/j.tins.2012.06.007 }}</ref><ref name="KEGG Morphine addiction">{{cite web | title = Morphine addiction – Homo sapiens (human) | url=http://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa05032 | website=KEGG | publisher=Kanehisa Laboratories | access-date=11 September 2014 | date=18 June 2013}}</ref> In other words, opioids inhibit the projections from the RMTg to the VTA, which in turn disinhibits the dopaminergic pathways that project from the VTA to the nucleus accumbens and elsewhere in the brain.<ref name="VTA tail" /><ref name="KEGG Morphine addiction" /> |

||

Neuroimaging has shown functional and structural alterations in the brain.<ref>{{ |

Neuroimaging has shown functional and structural alterations in the brain.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND | title = Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: neuroimaging findings and clinical implications | journal = Nature Reviews. Neuroscience | volume = 12 | issue = 11 | pages = 652–69 | date = October 2011 | pmid = 22011681 | pmc = 3462342 | doi = 10.1038/nrn3119 | url = http://www.nature.com/nrn/journal/v12/n11/full/nrn3119.html }}</ref> A 2017 study showed that chronic intake of opioid, such as heroin, may cause long-term effect in the orbitofrontal area (OFC), which is essential for regulating reward-related behaviors, emotional responses, and anxiety.<ref name="pmid28422138">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ieong HF, Yuan Z | title = Abnormal resting-state functional connectivity in the orbitofrontal cortex of heroin users and its relationship with anxiety: a pilot fNIRS study | journal = Scientific Reports | volume = 7 | issue = | pages = 46522 | date = April 2017 | pmid = 28422138 | pmc = 5395928 | doi = 10.1038/srep46522 }}</ref>{{secondary source needed|date=April 2017}} Moreover, neuroimaging and neuropsychological studies demonstrated dysregulation of circuits associated with emotion, stress and high impulsivity.<ref name="Ieong"/> |

||

===Dependence=== |

===Dependence=== |

||

[[Drug dependence]] is an adaptive state associated with a [[drug withdrawal|withdrawal syndrome]] upon cessation of repeated exposure to a stimulus (e.g., drug intake).<ref name="Cellular basis" /><ref name="Addiction glossary" /><ref name="Nestler Labs Glossary" /> Dependence is a component of a [[substance use disorder]].<ref name="Brain disease" /><ref name="Opioid use disorder - DSM-5 criteria">{{cite encyclopedia|section=Opioid Use Disorder: Diagnostic Criteria|title=Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition|chapter-url=http://pcssmat.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/5B-DSM-5-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Diagnostic-Criteria.pdf|publisher=American Psychiatric Association| |

[[Drug dependence]] is an adaptive state associated with a [[drug withdrawal|withdrawal syndrome]] upon cessation of repeated exposure to a stimulus (e.g., drug intake).<ref name="Cellular basis" /><ref name="Addiction glossary" /><ref name="Nestler Labs Glossary" /> Dependence is a component of a [[substance use disorder]].<ref name="Brain disease" /><ref name="Opioid use disorder - DSM-5 criteria">{{cite encyclopedia|section=Opioid Use Disorder: Diagnostic Criteria|title=Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition|chapter-url=http://pcssmat.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/5B-DSM-5-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Diagnostic-Criteria.pdf|publisher=American Psychiatric Association|access-date=27 March 2017|pages=1–9}}</ref> Opioid dependence can manifest as [[physical dependence]], [[psychological dependence]], or both.<ref name="pmid26740398" /><ref name="Addiction glossary" /><ref name="Opioid use disorder - DSM-5 criteria" /> |

||

Increased [[brain-derived neurotrophic factor]] (BDNF) signaling in the [[ventral tegmental area]] (VTA) has been shown to mediate opioid-induced withdrawal symptoms via downregulation of [[insulin receptor substrate 2]] (IRS2), [[protein kinase B]] (AKT), and [[mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 2]] (mTORC2).<ref name="Cellular basis" /><ref>{{cite journal | |

Increased [[brain-derived neurotrophic factor]] (BDNF) signaling in the [[ventral tegmental area]] (VTA) has been shown to mediate opioid-induced withdrawal symptoms via downregulation of [[insulin receptor substrate 2]] (IRS2), [[protein kinase B]] (AKT), and [[mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 2]] (mTORC2).<ref name="Cellular basis" /><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Vargas-Perez H, Ting-A Kee R, Walton CH, Hansen DM, Razavi R, Clarke L, Bufalino MR, Allison DW, Steffensen SC, van der Kooy D | title = Ventral tegmental area BDNF induces an opiate-dependent-like reward state in naive rats | journal = Science | volume = 324 | issue = 5935 | pages = 1732–4 | date = June 2009 | pmid = 19478142 | pmc = 2913611 | doi = 10.1126/science.1168501 }}</ref> As a result of downregulated signaling through these proteins, opiates cause VTA neuronal hyperexcitability and shrinkage (specifically, the size of the [[Soma (biology)|neuronal soma]] is reduced).<ref name="Cellular basis" /> It has been shown that when an opiate-naive person begins using opiates in concentrations that induce [[euphoria]], BDNF signaling increases in the VTA.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Laviolette SR, van der Kooy D | title = GABA(A) receptors in the ventral tegmental area control bidirectional reward signalling between dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic neural motivational systems | journal = The European Journal of Neuroscience | volume = 13 | issue = 5 | pages = 1009–15 | date = March 2001 | pmid = 11264674 | doi = 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2001.01458.x }}</ref> |

||

Upregulation of the [[cyclic adenosine monophosphate]] (cAMP) [[signal transduction]] pathway by [[cAMP response element binding protein]] (CREB), a gene [[transcription factor]], in the [[nucleus accumbens]] is a common mechanism of [[psychological dependence]] among several classes of drugs of abuse.<ref name="pmid26740398">{{cite journal | vauthors = Nestler EJ | title = Reflections on: "A general role for adaptations in G-Proteins and the cyclic AMP system in mediating the chronic actions of morphine and cocaine on neuronal function" | journal = Brain |

Upregulation of the [[cyclic adenosine monophosphate]] (cAMP) [[signal transduction]] pathway by [[cAMP response element binding protein]] (CREB), a gene [[transcription factor]], in the [[nucleus accumbens]] is a common mechanism of [[psychological dependence]] among several classes of drugs of abuse.<ref name="pmid26740398">{{cite journal | vauthors = Nestler EJ | title = Reflections on: "A general role for adaptations in G-Proteins and the cyclic AMP system in mediating the chronic actions of morphine and cocaine on neuronal function" | journal = Brain Research | volume = 1645 | issue = | pages = 71–4 | date = August 2016 | pmid = 26740398 | doi = 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.12.039 | quote = Specifically, opiates in several CNS regions including NAc, and cocaine more selectively in NAc induce expression of certain adenylyl cyclase isoforms and PKA subunits via the transcription factor, CREB, and these transcriptional adaptations serve a homeostatic function to oppose drug action. In certain brain regions, such as locus coeruleus, these adaptations mediate aspects of physical opiate dependence and withdrawal, whereas in NAc they mediate reward tolerance and dependence that drives increased drug self-administration. }}</ref><ref name="Cellular basis" /> Upregulation of the same pathway in the [[locus coeruleus]] is also a mechanism responsible for certain aspects of opioid-induced [[physical dependence]].<ref name="pmid26740398" /><ref name="Cellular basis" /> |

||

===Opioid receptors=== |

===Opioid receptors=== |

||

A genetic basis for the efficacy of opioids in the treatment of pain has been demonstrated for a number of specific variations; however, the evidence for clinical differences in opioid effects is ambiguous. The [[pharmacogenomics]] of the opioid receptors and their [[endogenous]] [[ligands]] have been the subject of intensive activity in association studies. These studies test broadly for a number of [[phenotypes]], including opioid dependence, [[cocaine dependence]], [[alcohol dependence]], [[Methamphetamine|methamphetamine dependence]]/[[Stimulant psychosis|psychosis]], response to naltrexone treatment, personality traits, and others. [[Substance dependence#Genetic Factors|Major and minor variants]] have been reported for every receptor and ligand coding gene in both coding sequences, as well as regulatory regions. |

A genetic basis for the efficacy of opioids in the treatment of pain has been demonstrated for a number of specific variations; however, the evidence for clinical differences in opioid effects is ambiguous. The [[pharmacogenomics]] of the opioid receptors and their [[endogenous]] [[ligands]] have been the subject of intensive activity in association studies. These studies test broadly for a number of [[phenotypes]], including opioid dependence, [[cocaine dependence]], [[alcohol dependence]], [[Methamphetamine|methamphetamine dependence]]/[[Stimulant psychosis|psychosis]], response to naltrexone treatment, personality traits, and others. [[Substance dependence#Genetic Factors|Major and minor variants]] have been reported for every receptor and ligand coding gene in both coding sequences, as well as regulatory regions. |

||

Newer approaches shift away from analysis of specific genes and regions, and are based on an unbiased screen of genes across the entire genome, which have no apparent relationship to the phenotype in question. These [[Genome-wide association study|GWAS]] studies yield a number of implicated genes, although many of them code for seemingly unrelated proteins in processes such as [[cell adhesion]], [[transcriptional regulation]], cell structure determination, and [[RNA]], [[DNA]], and protein handling/modifying.<ref name="pmid23872493">{{cite journal | vauthors = Hall FS, Drgonova J, Jain S, Uhl GR | title = Implications of genome wide association studies for addiction: are our a priori assumptions all wrong? | journal = |

Newer approaches shift away from analysis of specific genes and regions, and are based on an unbiased screen of genes across the entire genome, which have no apparent relationship to the phenotype in question. These [[Genome-wide association study|GWAS]] studies yield a number of implicated genes, although many of them code for seemingly unrelated proteins in processes such as [[cell adhesion]], [[transcriptional regulation]], cell structure determination, and [[RNA]], [[DNA]], and protein handling/modifying.<ref name="pmid23872493">{{cite journal | vauthors = Hall FS, Drgonova J, Jain S, Uhl GR | title = Implications of genome wide association studies for addiction: are our a priori assumptions all wrong? | journal = Pharmacology & Therapeutics | volume = 140 | issue = 3 | pages = 267–79 | date = December 2013 | pmid = 23872493 | pmc = 3797854 | doi = 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.07.006 }}</ref> |

||

Currently, there are no specific pharmacogenomic dosing recommendations for opioids due to a lack of clear evidence connecting genotype to drug effect, toxicity, or likelihood of dependence.{{citation needed|date=March 2017}} |

Currently, there are no specific pharmacogenomic dosing recommendations for opioids due to a lack of clear evidence connecting genotype to drug effect, toxicity, or likelihood of dependence.{{citation needed|date=March 2017}} |

||

====118A>G variant==== |

====118A>G variant==== |

||

While over 100 variants have been identified for the opioid mu-receptor, the most studied mu-receptor variant is the non-synonymous 118A>G variant, which results in functional changes to the receptor, including lower binding site availability, reduced [[mRNA]] levels, altered signal transduction, and increased affinity for [[beta-endorphin]]. In theory, all of these functional changes would reduce the impact of [[exogenous]] opioids, requiring a higher dose to achieve the same therapeutic effect. This points to a potential for a greater addictive capacity in these individuals who require higher dosages to achieve pain control. However, evidence linking the 118A>G variant to opioid dependence is mixed, with associations shown in a number of study groups, but negative results in other groups. One explanation for the mixed results is the possibility of other variants which are in [[linkage disequilibrium]] with the 118A>G variant and thus contribute to different [[haplotype]] patterns that more specifically associate with opioid dependence.<ref name="pmid23374939">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bruehl S, Apkarian AV, Ballantyne JC, Berger A, Borsook D, Chen WG, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Horn SD, Iadarola MJ, Inturrisi CE, Lao L, Mackey S, Mao J, Sawczuk A, Uhl GR, Witter J, Woolf CJ, Zubieta JK, Lin Y | title = Personalized medicine and opioid analgesic prescribing for chronic pain: opportunities and challenges | journal = |

While over 100 variants have been identified for the opioid mu-receptor, the most studied mu-receptor variant is the non-synonymous 118A>G variant, which results in functional changes to the receptor, including lower binding site availability, reduced [[mRNA]] levels, altered signal transduction, and increased affinity for [[beta-endorphin]]. In theory, all of these functional changes would reduce the impact of [[exogenous]] opioids, requiring a higher dose to achieve the same therapeutic effect. This points to a potential for a greater addictive capacity in these individuals who require higher dosages to achieve pain control. However, evidence linking the 118A>G variant to opioid dependence is mixed, with associations shown in a number of study groups, but negative results in other groups. One explanation for the mixed results is the possibility of other variants which are in [[linkage disequilibrium]] with the 118A>G variant and thus contribute to different [[haplotype]] patterns that more specifically associate with opioid dependence.<ref name="pmid23374939">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bruehl S, Apkarian AV, Ballantyne JC, Berger A, Borsook D, Chen WG, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Horn SD, Iadarola MJ, Inturrisi CE, Lao L, Mackey S, Mao J, Sawczuk A, Uhl GR, Witter J, Woolf CJ, Zubieta JK, Lin Y | title = Personalized medicine and opioid analgesic prescribing for chronic pain: opportunities and challenges | journal = The Journal of Pain | volume = 14 | issue = 2 | pages = 103–13 | date = February 2013 | pmid = 23374939 | pmc = 3564046 | doi = 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.10.016 }}</ref> |

||

====Non-opioid receptor genes==== |

====Non-opioid receptor genes==== |

||

The [[preproenkephalin]] gene, PENK, encodes for the endogenous opiates that modulate pain perception, and are implicated in reward and addiction. [[Microsatellite|(CA) repeats]] in the 3' flanking sequence of the PENK gene was associated with greater likelihood of opiate dependence in repeated studies. Variability in the MCR2 gene, encoding [[melanocortin receptor]] type 2 has been associated with both protective effects and increased susceptibility to heroin addiction. The CYP2B6 gene of the [[cytochrome P450]] family also mediates breakdown of opioids and thus may play a role in dependence and overdose.<ref name="pmid20055697">{{cite journal | vauthors = Khokhar JY, Ferguson CS, Zhu AZ, Tyndale RF | title = Pharmacogenetics of drug dependence: role of gene variations in susceptibility and treatment | journal = |

The [[preproenkephalin]] gene, PENK, encodes for the endogenous opiates that modulate pain perception, and are implicated in reward and addiction. [[Microsatellite|(CA) repeats]] in the 3' flanking sequence of the PENK gene was associated with greater likelihood of opiate dependence in repeated studies. Variability in the MCR2 gene, encoding [[melanocortin receptor]] type 2 has been associated with both protective effects and increased susceptibility to heroin addiction. The CYP2B6 gene of the [[cytochrome P450]] family also mediates breakdown of opioids and thus may play a role in dependence and overdose.<ref name="pmid20055697">{{cite journal | vauthors = Khokhar JY, Ferguson CS, Zhu AZ, Tyndale RF | title = Pharmacogenetics of drug dependence: role of gene variations in susceptibility and treatment | journal = Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology | volume = 50 | issue = | pages = 39–61 | date = 2010 | pmid = 20055697 | doi = 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105826 }}</ref> |

||

==Diagnosis== |

==Diagnosis== |

||

| Line 148: | Line 148: | ||

=== Opioid related deaths === |

=== Opioid related deaths === |

||

[[Naloxone]] is used for the [[Opioid overdose#Treatment|emergency treatment of an overdose]].<ref name="HMDB Naloxone">{{cite encyclopedia | title = Naloxone | url = http://www.hmdb.ca/metabolites/HMDB0015314 | work = Human Metabolome Database – Version 4.0 | |

[[Naloxone]] is used for the [[Opioid overdose#Treatment|emergency treatment of an overdose]].<ref name="HMDB Naloxone">{{cite encyclopedia | title = Naloxone | url = http://www.hmdb.ca/metabolites/HMDB0015314 | work = Human Metabolome Database – Version 4.0 | access-date = 2 November 2017 | date = 23 October 2017 }}</ref> It can be given by many routes (e.g., intramuscular, intravenous, subcutaneous, intranasal, and inhalation) and acts quickly by displacing opioids from opioid receptors and preventing activation of these receptors by opioids.<ref>{{cite web|title=Naloxone for Treatement of Opioide Overdose|url=https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/AnestheticAndAnalgesicDrugProductsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM522690.pdf|website=FDA|access-date=7 November 2017}}</ref> Naloxone kits are recommended for laypersons who may witness an opioid overdose, for individuals with large prescriptions for opioids, those in substance use treatment programs, or who have been recently released from incarceration.<ref name=":11">{{Cite web|url=https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6423a2.htm|title=Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone to Laypersons — United States, 2014|website=www.cdc.gov|language=en|access-date=9 March 2017}}</ref> Since this is a life-saving medication, many areas of the United States have implemented standing orders for law enforcement to carry and give naloxone as needed.<ref name="FDA – law enforcement and naloxone">{{cite web | vauthors = Childs R | date = July 2015 | title = Law enforcement and naloxone utilization in the United States | url = https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/NewsEvents/UCM454810.pdf | website = United States Food and Drug Administration | publisher = North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition | access-date = 2 November 2017 | pages = 1–24}}</ref><ref name="Naloxone standing orders">{{cite web | title = Case studies: Standing orders | url = http://naloxoneinfo.org/case-studies/standing-orders | website = NaloxoneInfo.org | publisher = Open Society Foundations | access-date = 2 November 2017}}</ref> In addition, naloxone could be used to challenge a person's opioid abstinence status prior to starting a medication such as [[naltrexone]], which is used in the management of opioid addiction.<ref name="pmid27464203">{{cite journal | vauthors = Schuckit MA | title = Treatment of Opioid-Use Disorders | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 375 | issue = 4 | pages = 357–68 | date = July 2016 | pmid = 27464203 | doi = 10.1056/NEJMra1604339 | url = http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1604339#t=article }}</ref> |

||

==Management== |

==Management== |

||

Opioid use disorders typically require [[Long-term care|long-term treatment and care]] with the goal of reducing risks for the individual, reducing criminal behaviour, and improving the long-term physical and psychological condition of the person.<ref name=WHOmain/> Most strategies aim ultimately to reduce drug use and lead to abstinence.<ref name=WHOmain/> No single treatment works for everyone, so several strategies have been developed including therapy and drugs.<ref name=WHOmain/><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Nicholls L, Bragaw L, Ruetsch C |title=Opioid |

Opioid use disorders typically require [[Long-term care|long-term treatment and care]] with the goal of reducing risks for the individual, reducing criminal behaviour, and improving the long-term physical and psychological condition of the person.<ref name=WHOmain/> Most strategies aim ultimately to reduce drug use and lead to abstinence.<ref name=WHOmain/> No single treatment works for everyone, so several strategies have been developed including therapy and drugs.<ref name=WHOmain/><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Nicholls L, Bragaw L, Ruetsch C | title = Opioid dependence treatment and guidelines | journal = Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy | volume = 16 | issue = 1 Suppl B | pages = S14-21 | date = February 2010 | pmid = 20146550 | url = http://www.healthanalytic.com/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=osz9-YYUsUU%3D&tabid=78 }}</ref> |

||

As of 2013 in the US, there was a significant increase of prescription opioid abuse compared to [[illicit drugs|illegal opiates]] like [[heroin]].<ref name="pmid23881609">{{cite journal | vauthors = Daubresse M, Gleason PP, Peng Y, Shah ND, Ritter ST, Alexander GC | title = Impact of a drug utilization review program on high-risk use of prescription controlled substances | journal = |

As of 2013 in the US, there was a significant increase of prescription opioid abuse compared to [[illicit drugs|illegal opiates]] like [[heroin]].<ref name="pmid23881609">{{cite journal | vauthors = Daubresse M, Gleason PP, Peng Y, Shah ND, Ritter ST, Alexander GC | title = Impact of a drug utilization review program on high-risk use of prescription controlled substances | journal = Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety | volume = 23 | issue = 4 | pages = 419–27 | date = April 2014 | pmid = 23881609 | doi = 10.1002/pds.3487 }}</ref> This development has also implications for the prevention, treatment and therapy of opioid dependence.<ref>Amy Maxmen (June 2012), "Tackling the US pain epidemic". ''Nature News'' {{DOI|10.1038/nature.2012.10766}}</ref> Though treatment reduces mortality rates, the period during the first four weeks after treatment begins and the four weeks after treatment ceases are the times that carry the highest risk for drug related deaths. These periods of increased vulnerability are significant because many of those in treatment leave programs during these critical periods.<ref name="BMJ2017Re" /> |

||

===Medications=== |

===Medications=== |

||

Opioid replacement therapy (ORT), also called opioid substitution therapy or opioid maintenance therapy, involves replacing an [[opioid]], such as [[heroin]], with a longer acting but less euphoric opioid.<ref name="NEPOD Report" /> Commonly used drugs for ORT are [[methadone]] or [[buprenorphine]] which are taken under medical supervision.<ref name="NEPOD Report">Richard P. Mattick et al.: [http://content.webarchive.nla.gov.au/gov/wayback/20140211195842/http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/Publishing.nsf/content/8BA50209EE22B9C6CA2575B40013539D/$File/mono52.pdf National Evaluation of Pharmacotherapies for Opioid Dependence (NEPOD): Report of Results and Recommendation]</ref> As of 2018 [[buprenorphine/naloxone]] is preferentially recommended.<ref name=CMAJ2018>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bruneau J, Ahamad K, Goyer MÈ, Poulin G, Selby P, Fischer B, Wild TC, Wood E | title = Management of opioid use disorders: a national clinical practice guideline | journal = |

Opioid replacement therapy (ORT), also called opioid substitution therapy or opioid maintenance therapy, involves replacing an [[opioid]], such as [[heroin]], with a longer acting but less euphoric opioid.<ref name="NEPOD Report" /> Commonly used drugs for ORT are [[methadone]] or [[buprenorphine]] which are taken under medical supervision.<ref name="NEPOD Report">Richard P. Mattick et al.: [http://content.webarchive.nla.gov.au/gov/wayback/20140211195842/http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/Publishing.nsf/content/8BA50209EE22B9C6CA2575B40013539D/$File/mono52.pdf National Evaluation of Pharmacotherapies for Opioid Dependence (NEPOD): Report of Results and Recommendation]</ref> As of 2018 [[buprenorphine/naloxone]] is preferentially recommended.<ref name=CMAJ2018>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bruneau J, Ahamad K, Goyer MÈ, Poulin G, Selby P, Fischer B, Wild TC, Wood E | title = Management of opioid use disorders: a national clinical practice guideline | journal = Cmaj | volume = 190 | issue = 9 | pages = E247-E257 | date = March 2018 | pmid = 29507156 | pmc = 5837873 | doi = 10.1503/cmaj.170958 }}</ref> |

||

The driving principle behind ORT is the program's capacity to facilitate a resumption of stability in the user's life, while the patient experiences reduced symptoms of [[drug withdrawal]] and less intense [[Craving (withdrawal)|drug cravings]]; a strong euphoric effect is not experienced as a result of the treatment drug.<ref name="NEPOD Report"/> In some countries (not the US, or Australia),<ref name="NEPOD Report"/> regulations enforce a limited time period for people on ORT programs that conclude when a stable economic and psychosocial situation is achieved. (People with [[HIV|HIV/AIDS]] or [[hepatitis C]] are usually excluded from this requirement.) In practice, 40–65% of patients maintain abstinence from additional opioids while receiving opioid replacement therapy and 70–95% are able to reduce their use significantly.<ref name="NEPOD Report" /> Along with this is a concurrent elimination or reduction in medical (improper [[diluent]]s, non-[[Sterilization (microbiology)|sterile]] injecting equipment), psychosocial ([[mental health]], relationships), and legal ([[arrest]] and [[imprisonment]]) issues that can arise from the use of illegal opioids.<ref name="NEPOD Report"/> [[Clonidine]] or [[lofexidine]] can help treat the symptoms of withdrawal.<ref>{{cite journal| |

The driving principle behind ORT is the program's capacity to facilitate a resumption of stability in the user's life, while the patient experiences reduced symptoms of [[drug withdrawal]] and less intense [[Craving (withdrawal)|drug cravings]]; a strong euphoric effect is not experienced as a result of the treatment drug.<ref name="NEPOD Report"/> In some countries (not the US, or Australia),<ref name="NEPOD Report"/> regulations enforce a limited time period for people on ORT programs that conclude when a stable economic and psychosocial situation is achieved. (People with [[HIV|HIV/AIDS]] or [[hepatitis C]] are usually excluded from this requirement.) In practice, 40–65% of patients maintain abstinence from additional opioids while receiving opioid replacement therapy and 70–95% are able to reduce their use significantly.<ref name="NEPOD Report" /> Along with this is a concurrent elimination or reduction in medical (improper [[diluent]]s, non-[[Sterilization (microbiology)|sterile]] injecting equipment), psychosocial ([[mental health]], relationships), and legal ([[arrest]] and [[imprisonment]]) issues that can arise from the use of illegal opioids.<ref name="NEPOD Report"/> [[Clonidine]] or [[lofexidine]] can help treat the symptoms of withdrawal.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gowing L, Farrell M, Ali R, White JM | title = Alpha₂-adrenergic agonists for the management of opioid withdrawal | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | issue = 5 | pages = CD002024 | date = May 2016 | pmid = 27140827 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD002024.pub5 }}</ref> |

||

Participation in methadone and buprenorphine treatment reduces the risk of mortality due to overdose.<ref name="BMJ2017Re" /> The starting of methadone and the time immediately after leaving treatment with both drugs are periods of particularly increased mortality risk, which should be dealt with by both public health and clinical strategies.<ref name=BMJ2017Re/> ORT has proven to be the most effective treatment for improving the health and living condition of people experiencing problematic illegal opiate use or dependence, including mortality reduction<ref name="NEPOD Report"/><ref>Michel et al.: [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1797169 Substitution treatment for opioid addicts in Germany], Harm Reduct J. 2007; 4: 5.</ref><ref name=BMJ2017Re/> and overall societal costs, such as the economic loss from [[drug-related crime]] and healthcare expenditure.<ref name="NEPOD Report"/> Opioid Replacement Therapy is endorsed by the [[World Health Organization]], [[United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime]] and [[UNAIDS]] as being effective at reducing injection, lowering risk for HIV/AIDS, and promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy.<ref name="BMJ2017Re" /> Currently, 55 countries worldwide use methadone replacement therapy, while some countries such as Russia do not.<ref>{{cite news|title=Russia Scorns Methadone for Heroin Addiction|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/22/health/22meth.html?pagewanted=all| |

Participation in methadone and buprenorphine treatment reduces the risk of mortality due to overdose.<ref name="BMJ2017Re" /> The starting of methadone and the time immediately after leaving treatment with both drugs are periods of particularly increased mortality risk, which should be dealt with by both public health and clinical strategies.<ref name=BMJ2017Re/> ORT has proven to be the most effective treatment for improving the health and living condition of people experiencing problematic illegal opiate use or dependence, including mortality reduction<ref name="NEPOD Report"/><ref>Michel et al.: [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1797169 Substitution treatment for opioid addicts in Germany], Harm Reduct J. 2007; 4: 5.</ref><ref name=BMJ2017Re/> and overall societal costs, such as the economic loss from [[drug-related crime]] and healthcare expenditure.<ref name="NEPOD Report"/> Opioid Replacement Therapy is endorsed by the [[World Health Organization]], [[United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime]] and [[UNAIDS]] as being effective at reducing injection, lowering risk for HIV/AIDS, and promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy.<ref name="BMJ2017Re" /> Currently, 55 countries worldwide use methadone replacement therapy, while some countries such as Russia do not.<ref>{{cite news|title=Russia Scorns Methadone for Heroin Addiction|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/22/health/22meth.html?pagewanted=all|access-date=5 April 2014|newspaper=The New York Times|date=22 July 2008| first = Michael | last = Schwartz | name-list-format = vanc }}</ref> |

||

====Methadone==== |

====Methadone==== |

||

[[File:Methadone 40mg.jpg|thumb|40 mg of methadone]] |

[[File:Methadone 40mg.jpg|thumb|40 mg of methadone]] |

||

{{Main|Methadone maintenance}} |

{{Main|Methadone maintenance}} |

||

[[Methadone]] maintenance treatment (MMT), a form of opioid replacement therapy, reduces and/or eliminates the use of illegal opiates, the criminality associated with opiate use, and allows patients to improve their health and social productivity.<ref name="JosephStancliffLangrod"/><ref name="Connock">{{cite journal | |

[[Methadone]] maintenance treatment (MMT), a form of opioid replacement therapy, reduces and/or eliminates the use of illegal opiates, the criminality associated with opiate use, and allows patients to improve their health and social productivity.<ref name="JosephStancliffLangrod"/><ref name="Connock">{{cite journal | vauthors = Connock M, Juarez-Garcia A, Jowett S, Frew E, Liu Z, Taylor RJ, Fry-Smith A, Day E, Lintzeris N, Roberts T, Burls A, Taylor RS | title = Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence: a systematic review and economic evaluation | journal = Health Technology Assessment | volume = 11 | issue = 9 | pages = 1–171, iii-iv | date = March 2007 | pmid = 17313907 | doi = 10.3310/hta11090 | url = http://www.hta.ac.uk/execsumm/summ1109.htm }}</ref> Methadone is an [[agonist]] of opioids. If initial doses during the beginning of treatment are too high or are concurrent with illicit opioid use, this may present an increased risk of death from overdose.<ref name=BMJ2017Re/> In addition, enrollment in methadone maintenance has the potential to reduce the transmission of infectious diseases associated with opiate injection, such as hepatitis and HIV.<ref name="JosephStancliffLangrod"/> The principal effects of methadone maintenance are to relieve narcotic craving, suppress the abstinence syndrome, and block the euphoric effects associated with opiates. Methadone maintenance has been found to be medically safe and non-sedating.<ref name="JosephStancliffLangrod"/> It is also indicated for pregnant women addicted to opiates.<ref name="JosephStancliffLangrod">{{cite journal | vauthors = Joseph H, Stancliff S, Langrod J | title = Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT): a review of historical and clinical issues | journal = The Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, New York | volume = 67 | issue = 5-6 | pages = 347–64 | year = 2000 | pmid = 11064485 }}</ref> |

||

[[Methadone maintenance]] treatment is given to addicted individuals who feel unable to go the whole way and get clean. For individuals who wish to completely move away from drugs, they can start a methadone reduction program. A methadone reduction program is where an individual is prescribed an amount of methadone which is increased until withdrawal symptoms subside, after a period of stability, the dose will then be gradually reduced until the individual is either free of the need for methadone or is at a level which allows a switch to a different opiate with an easier withdrawal profile, such as [[suboxone]]. Methadone toxicity has been shown to be associated with specific phenotypes of [[CYP2B6]].<ref name="pmid20668445">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bunten H, Liang WJ, Pounder DJ, Seneviratne C, Osselton D | title = OPRM1 and CYP2B6 gene variants as risk factors in methadone-related deaths | journal = |

[[Methadone maintenance]] treatment is given to addicted individuals who feel unable to go the whole way and get clean. For individuals who wish to completely move away from drugs, they can start a methadone reduction program. A methadone reduction program is where an individual is prescribed an amount of methadone which is increased until withdrawal symptoms subside, after a period of stability, the dose will then be gradually reduced until the individual is either free of the need for methadone or is at a level which allows a switch to a different opiate with an easier withdrawal profile, such as [[suboxone]]. Methadone toxicity has been shown to be associated with specific phenotypes of [[CYP2B6]].<ref name="pmid20668445">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bunten H, Liang WJ, Pounder DJ, Seneviratne C, Osselton D | title = OPRM1 and CYP2B6 gene variants as risk factors in methadone-related deaths | journal = Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics | volume = 88 | issue = 3 | pages = 383–9 | date = September 2010 | pmid = 20668445 | doi = 10.1038/clpt.2010.127 }}</ref> |

||

Some impairment in cognition has been demonstrated in those using methadone.<ref name="Ieong">{{ |

Some impairment in cognition has been demonstrated in those using methadone.<ref name="Ieong">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ieong HF, Yuan Z | title = Resting-State Neuroimaging and Neuropsychological Findings in Opioid Use Disorder during Abstinence: A Review | language = English | journal = Frontiers in Human Neuroscience | volume = 11 | pages = 169 | date = 1 January 2017 | pmid = 28428748 | doi = 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00169 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Darke S, Sims J, McDonald S, Wickes W | title = Cognitive impairment among methadone maintenance patients | journal = Addiction | volume = 95 | issue = 5 | pages = 687–95 | date = May 2000 | pmid = 10885043 | doi = 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9556874.x }}</ref> |

||

====Buprenorphine==== |

====Buprenorphine==== |

||

[[File:Suboxone.jpg|thumb|Buprenorphine/naloxone tablet]] |

[[File:Suboxone.jpg|thumb|Buprenorphine/naloxone tablet]] |

||

Treatment with buprenorphine may be associated with reduced mortality.<ref name="BMJ2017Re" /> Buprenorphine [[Sublingual administration|under the tongue]] is often used to manage opioid [[Chemical dependency|dependence]]. Preparations were approved for this use in the United States in 2002.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm191521.htm | title=Subutex and Suboxone Approved to Treat Opiate Dependence | publisher=FDA | date=8 October 2002 | |

Treatment with buprenorphine may be associated with reduced mortality.<ref name="BMJ2017Re" /> Buprenorphine [[Sublingual administration|under the tongue]] is often used to manage opioid [[Chemical dependency|dependence]]. Preparations were approved for this use in the United States in 2002.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm191521.htm | title=Subutex and Suboxone Approved to Treat Opiate Dependence | publisher=FDA | date=8 October 2002 | access-date=1 November 2014}}</ref> Some formulations of buprenorphine incorporate the opiate antagonist [[naloxone]] during the production of the [[Tablet (pharmacy)|pill]] form to prevent people from crushing the tablets and injecting them, instead of using the [[sublingual]] (under the tongue) route of administration.<ref name="NEPOD Report"/> |

||

====Diamorphine==== |

====Diamorphine==== |

||

{{See also|Heroin maintenance}} |

{{See also|Heroin maintenance}} |

||

In Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, long-term [[Injecting Drug User|injecting drug user]]s who do not benefit from [[methadone]] and other medication options are treated with pure injectable [[diamorphine]] that is administered under the supervision of medical staff. For this group of patients, diamorphine treatment has proven superior in improving their social and health situation.<ref>{{cite journal | |

In Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, long-term [[Injecting Drug User|injecting drug user]]s who do not benefit from [[methadone]] and other medication options are treated with pure injectable [[diamorphine]] that is administered under the supervision of medical staff. For this group of patients, diamorphine treatment has proven superior in improving their social and health situation.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Haasen C, Verthein U, Degkwitz P, Berger J, Krausz M, Naber D | title = Heroin-assisted treatment for opioid dependence: randomised controlled trial | journal = The British Journal of Psychiatry | volume = 191 | pages = 55–62 | date = July 2007 | pmid = 17602126 | doi = 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.026112 }}</ref> |

||

====Dihydrocodeine==== |

====Dihydrocodeine==== |

||

[[Dihydrocodeine]] in both extended-release and immediate-release form are also sometimes used for maintenance treatment as an alternative to methadone or buprenorphine in some European countries.<ref>{{cite journal | |

[[Dihydrocodeine]] in both extended-release and immediate-release form are also sometimes used for maintenance treatment as an alternative to methadone or buprenorphine in some European countries.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Robertson JR, Raab GM, Bruce M, McKenzie JS, Storkey HR, Salter A | title = Addressing the efficacy of dihydrocodeine versus methadone as an alternative maintenance treatment for opiate dependence: A randomized controlled trial | journal = Addiction | volume = 101 | issue = 12 | pages = 1752–9 | date = December 2006 | pmid = 17156174 | doi = 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01603.x }}</ref> Dihydrocodeine is an opioid agonist.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/dihydrocodeine#section=Top|title=Dihydrocodeine|work = Pubchem }}</ref> It may be used as a second line treatment.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/doc/retrieve/docid/patch_f/6747#f_uses|title=Login|website=online.lexi.com|language=en-US|access-date=2018-11-02}}</ref> There is a lack of effective data suggesting its safety of use with concerns of more deaths.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Zamparutti G, Schifano F, Corkery JM, Oyefeso A, Ghodse AH | title = Deaths of opiate/opioid misusers involving dihydrocodeine, UK, 1997-2007 | journal = British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology | volume = 72 | issue = 2 | pages = 330–7 | date = August 2011 | pmid = 21235617 | pmc = 3162662 | doi = 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03908.x }}</ref> |

||

==== Heroin-assisted treatment ==== |

==== Heroin-assisted treatment ==== |

||

[[Heroin-assisted treatment]] (HAT, the medical prescription of heroin) has been available in Switzerland since 1994.<ref name="pmid11705488">{{cite journal |vauthors=Rehm J, Gschwend P, Steffen T, Gutzwiller F, Dobler-Mikola A, Uchtenhagen A |title=Feasibility, safety, and efficacy of injectable heroin prescription for refractory opioid addicts: a follow-up study |journal=Lancet |volume=358 |issue=9291 |pages=1417–23 | |

[[Heroin-assisted treatment]] (HAT, the medical prescription of heroin) has been available in Switzerland since 1994.<ref name="pmid11705488">{{cite journal | vauthors = Rehm J, Gschwend P, Steffen T, Gutzwiller F, Dobler-Mikola A, Uchtenhagen A | title = Feasibility, safety, and efficacy of injectable heroin prescription for refractory opioid addicts: a follow-up study | journal = Lancet | volume = 358 | issue = 9291 | pages = 1417–23 | date = October 2001 | pmid = 11705488 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06529-1 | url = http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140-6736(01)06529-1 }}</ref> A 2001 study found a high rate of treatment retention and significant improvement in health, social situation and likelihood to leave the illegal drug scene in enrolled participants.<ref name="pmid11705488"/> The study found that the most common reason for discharge was the start of abstinence treatment or methadone treatment.<ref name="pmid11705488"/> The study also found that heroin-assisted treatment is cost-beneficial on a society level due to reduced criminality and improved overall health of participants.<ref name="pmid11705488"/> |

||

The heroin-assisted treatment program was introduced in Switzerland to combat the increase in heroin use in the 1980s and 1990s and written into law 2010 as one pillar of a four-pillar strategy using repression, prevention, treatment and risk reduction.<ref name="urlDrogenpolitik2013">{{cite web |url=http://www.nzz.ch/schweiz/heroinabgabe-gemaess-experten-ein-erfolg-1.18194137 |title=Drogenpolitik: Heroinabgabe gemäss Experten ein Erfolg – NZZ Schweiz |format= |work= | |

The heroin-assisted treatment program was introduced in Switzerland to combat the increase in heroin use in the 1980s and 1990s and written into law 2010 as one pillar of a four-pillar strategy using repression, prevention, treatment and risk reduction.<ref name="urlDrogenpolitik2013">{{cite web |url=http://www.nzz.ch/schweiz/heroinabgabe-gemaess-experten-ein-erfolg-1.18194137 |title=Drogenpolitik: Heroinabgabe gemäss Experten ein Erfolg – NZZ Schweiz |format= |work= |access-date=4 March 2016}}</ref> Usually, only a small percentage of patients receives heroin and have to fulfil a number of criteria.<ref name="bag_heroin">{{cite web|url=http://www.bag.admin.ch/themen/drogen/00042/00629/00799/index.html?lang=de|title=Bundesamt für Gesundheit – Substitutionsgestützte Behandlung mit Diacetylmorphin (Heroin)|format=|work=|access-date=|deadurl=yes|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160313061735/http://www.bag.admin.ch/themen/drogen/00042/00629/00799/index.html?lang=de|archive-date=13 March 2016}}</ref><ref name="nzz_heroin2012">{{cite web |url=http://www.nzz.ch/heroinsuechtige-mitten-im-leben-1.14171541 |title=Dank der ärztlichen Heroinabgabe können rund 1400 Süchtige legal konsumieren – Einige schaffen den Anschluss an die Gesellschaft: Heroinsüchtige mitten im Leben – NZZ |format= |work= |access-date=}}</ref> Since then, HAT programs have been adopted in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany, Spain, Denmark, Belgium, Canada, and Luxembourg.<ref name="urlHeroin Assisted Treatment | Drug Policy Alliance">{{cite web |url=http://www.drugpolicy.org/resource/heroin-assisted-treatment-hat |title=Heroin Assisted Treatment | Drug Policy Alliance |format= |work= |access-date=4 March 2016}}</ref> |

||

====Morphine (extended-release)==== |

====Morphine (extended-release)==== |

||

An [[extended-release morphine]] confers a possible reduction of opioid use and with fewer depressive symptoms but overall more adverse effects when compared to other forms of long-acting opioids. Retention in treatment was not found to be significantly different.<ref name="FerriMinozzi2013">{{cite journal| |

An [[extended-release morphine]] confers a possible reduction of opioid use and with fewer depressive symptoms but overall more adverse effects when compared to other forms of long-acting opioids. Retention in treatment was not found to be significantly different.<ref name="FerriMinozzi2013">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ferri M, Minozzi S, Bo A, Amato L | title = Slow-release oral morphine as maintenance therapy for opioid dependence | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | issue = 6 | pages = CD009879 | date = June 2013 | pmid = 23740540 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD009879.pub2 }}</ref> It is used in Switzerland and more recently in Canada.<ref name="bag_heroin"/> |

||

====Naltrexone==== |

====Naltrexone==== |

||

[[Naltrexone]] is used for the treatment of opioid addiction.<ref name=":12">{{Cite web|url=https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/021897s029lbl.pdf|title=Vivitrol Prescribing Information| |

[[Naltrexone]] is used for the treatment of opioid addiction.<ref name=":12">{{Cite web|url=https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/021897s029lbl.pdf|title=Vivitrol Prescribing Information|publisher = Alkermes Inc. |date=July 2013|access-date=2 November 2017}}</ref><ref name=":13">{{cite journal | vauthors = Skolnick P | title = The Opioid Epidemic: Crisis and Solutions | journal = Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology | volume = 58 | issue = 1 | pages = 143–159 | date = January 2018 | pmid = 28968188 | doi = 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010617-052534 | url = http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010617-052534 }}</ref> It works by blocking the physiological, [[Euphoria|euphoric]], and [[Reinforcement|reinforcing]] effects of opioids.<ref name=":13" /><ref name=":14">{{Cite book|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64042/|title=Chapter 4—Oral Naltrexone | author = Center for Substance Abuse Treatment |date=2009|publisher=Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US)|language=en}}</ref> Non-[[Adherence (medicine)|compliance]] with naltrexone therapy is a concern with oral [[Dosage form|formulations]] because of its daily dosing,<ref name=":14" /> and although the alternative [[Intramuscular injection|intramuscular (IM) injection]] has better compliance due to its monthly dosing, attempts to override the blocking effect with higher doses and stronger drugs have proven dangerous. Naltrexone monthly IM injections received FDA approval in 2010 for the treatment of opioid dependence in [[Abstinence#Medicine|abstinent]] opioid users.<ref name=":12" /><ref name=":14" /> |

||

===Behavioral therapy=== |

===Behavioral therapy=== |

||

| Line 196: | Line 196: | ||

====Cognitive behavioral therapy==== |

====Cognitive behavioral therapy==== |

||

[[Cognitive behavioral therapy]] (CBT), a form of psychosocial intervention that is used to improve mental health, may not be as effective as other forms of treatment.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/698332858|title=Cognitive behavior therapy : basics and beyond| |

[[Cognitive behavioral therapy]] (CBT), a form of psychosocial intervention that is used to improve mental health, may not be as effective as other forms of treatment.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/698332858|title=Cognitive behavior therapy : basics and beyond | vauthors = Beck JS |publisher=|year=|isbn=9781609185046|edition=Second|location=New York|pages=19–20|oclc=698332858}}</ref> CBT primarily focuses on an individual's coping strategies to help change their cognition, behaviors and emotions about the problem. This intervention has demonstrated success in many psychiatric conditions (e.g., depression) and substance use disorders (e.g., tobacco).<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Huibers MJ, Beurskens AJ, Bleijenberg G, van Schayck CP | title = Psychosocial interventions by general practitioners | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | issue = 3 | pages = CD003494 | date = July 2007 | pmid = 17636726 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD003494.pub2 }}</ref> However, the use of CBT alone in opioid dependence has declined due to the lack of efficacy and many are relying on medication therapy or medication therapy with CBT since it was found to be more efficacious than CBT alone.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.uptodate.com/contents/psychosocial-interventions-for-opioid-use-disorder|title=Psychosocial interventions for opioid use disorder|website=www.uptodate.com|access-date=2 November 2017}}</ref> |

||

====Twelve-step programs==== |

====Twelve-step programs==== |

||

{{Main|Twelve-step program}} |

{{Main|Twelve-step program}} |

||

While medical treatment may help with the initial symptoms of opioid withdrawal, once the first stages of withdrawal are through, a method for long-term preventative care is attendance at 12-step groups such as [[Narcotics Anonymous]].<ref>{{cite journal| |

While medical treatment may help with the initial symptoms of opioid withdrawal, once the first stages of withdrawal are through, a method for long-term preventative care is attendance at 12-step groups such as [[Narcotics Anonymous]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Melemis SM | title = Relapse Prevention and the Five Rules of Recovery | journal = The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine | volume = 88 | issue = 3 | pages = 325–32 | date = September 2015 | pmid = 26339217 | pmc = 4553654 }}</ref> Some evidence supports the use of these programs in adolescents as well.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sussman S | title = A review of Alcoholics Anonymous/ Narcotics Anonymous programs for teens | journal = Evaluation & the Health Professions | volume = 33 | issue = 1 | pages = 26–55 | date = March 2010 | pmid = 20164105 | pmc = 4181564 | doi = 10.1177/0163278709356186 }}</ref> |

||

The [[12-step program]] is an adapted form of the [[Alcoholics Anonymous]] program. The program strives to help create behavioral change by fostering peer-support and self-help programs. The model helps assert the gravity of addiction by enforcing the idea that addicts must surrender to the fact that they are addicted and to be able to recognize the problem. It also helps maintain self-control and restraint to help promote one's capabilities.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://americanaddictioncenters.org/rehab-guide/12-step/|title=12 Step Programs for Drug Rehab & Alcohol Treatment|work=American Addiction Centers|access-date=24 October 2017|language=en-US}}</ref> |

The [[12-step program]] is an adapted form of the [[Alcoholics Anonymous]] program. The program strives to help create behavioral change by fostering peer-support and self-help programs. The model helps assert the gravity of addiction by enforcing the idea that addicts must surrender to the fact that they are addicted and to be able to recognize the problem. It also helps maintain self-control and restraint to help promote one's capabilities.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://americanaddictioncenters.org/rehab-guide/12-step/|title=12 Step Programs for Drug Rehab & Alcohol Treatment|work=American Addiction Centers|access-date=24 October 2017|language=en-US}}</ref> |

||

| Line 206: | Line 206: | ||

==Epidemiology== |

==Epidemiology== |

||

{{see also|Opioid crisis}} |

{{see also|Opioid crisis}} |

||

Globally, the number of people with opioid dependence increased from 10.4 million in 1990 to 15.5 million in 2010.<ref name="BMJ2017Re" /> Opioid use disorders resulted in 122,000 deaths worldwide in 2015,<ref name=GBD2015>{{cite journal| |

Globally, the number of people with opioid dependence increased from 10.4 million in 1990 to 15.5 million in 2010.<ref name="BMJ2017Re" /> Opioid use disorders resulted in 122,000 deaths worldwide in 2015,<ref name=GBD2015>{{cite journal | vauthors = | title = Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 | journal = Lancet | volume = 388 | issue = 10053 | pages = 1459–1544 | date = October 2016 | pmid = 27733281 | pmc = 5388903 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1 }}</ref> up from 18,000 deaths in 1990.<ref name=GDB2013>{{cite journal | vauthors = | title = Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 | journal = Lancet | volume = 385 | issue = 9963 | pages = 117–71 | date = January 2015 | pmid = 25530442 | pmc = 4340604 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2 }}</ref> Deaths from all causes rose from 47.5 million in 1990 to 55.8 million in 2013.<ref name=GDB2013/><ref name=GBD2015/> |

||

===United States=== |

===United States=== |

||

| Line 213: | Line 213: | ||

The current epidemic of opioid abuse is the most lethal drug epidemic in American history.<ref name=NYT2018/> In 2008, there were four times as many deaths due to overdose than there were in 1999. <ref name=":10" /> According to the CDC in 2017, in the US, "the age-adjusted drug poisoning death rate involving opioid analgesics increased from 1.4 to 5.4 deaths per 100,000 population between 1999 and 2010, decreased to 5.1 in 2012 and 2013, then increased to 5.9 in 2014, and to 7.0 in 2015. The age-adjusted drug poisoning death rate involving heroin doubled from 0.7 to 1.4 deaths per 100,000 resident population between 1999 and 2011 and then continued to increase to 4.1 in 2015."<ref>{{cite book|title=Health, United States, 2016: With Chartbook on Long-term Trends in Health|date=2017|publisher=CDC, National Center for Health Statistics.|location=Hyattsville, MD.|page=4|url=https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus16.pdf}}</ref> |

The current epidemic of opioid abuse is the most lethal drug epidemic in American history.<ref name=NYT2018/> In 2008, there were four times as many deaths due to overdose than there were in 1999. <ref name=":10" /> According to the CDC in 2017, in the US, "the age-adjusted drug poisoning death rate involving opioid analgesics increased from 1.4 to 5.4 deaths per 100,000 population between 1999 and 2010, decreased to 5.1 in 2012 and 2013, then increased to 5.9 in 2014, and to 7.0 in 2015. The age-adjusted drug poisoning death rate involving heroin doubled from 0.7 to 1.4 deaths per 100,000 resident population between 1999 and 2011 and then continued to increase to 4.1 in 2015."<ref>{{cite book|title=Health, United States, 2016: With Chartbook on Long-term Trends in Health|date=2017|publisher=CDC, National Center for Health Statistics.|location=Hyattsville, MD.|page=4|url=https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus16.pdf}}</ref> |

||

In 2012 it was estimated that 9.2 percent of the population over the age of 12 years old had used an [[Illegal drug trade|illicit drug]] in the previous month.<ref>Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4795. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013.</ref> In 2015, it was estimated the 20.5 million Americans had a [[substance use disorder]].<ref name=":10">{{Cite web|url=http://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/advocacy/opioid-addiction-disease-facts-figures.pdf|title=Opioid Addiction 2016 Facts and Figures| |