Bač, Serbia

Bač

Бач (Serbian) | |

|---|---|

Town and municipality | |

View of the fortress and the town of Bač | |

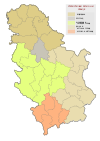

Location of the municipality of Bač within Serbia | |

| Coordinates: 45°23′N 19°14′E / 45.383°N 19.233°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Region | Bačka (Podunavlje) |

| District | South Bačka |

| Municipality | Bač |

| Settlements | 6 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Lela Milinović (SNS) |

| Area | |

| • Town | 111.89 km2 (43.20 sq mi) |

| • Municipality | 367.48 km2 (141.88 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 83 m (272 ft) |

| Population (2022 census)[2] | |

| • Town | 4,405 |

| • Town density | 39/km2 (100/sq mi) |

| • Municipality | 11,431 |

| • Municipality density | 31/km2 (81/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 21420 |

| Area code | +381 21 |

| Car plates | NS |

| Website | www |

Bač (Serbian Cyrillic: Бач, pronounced [bâːtʃ] ; Hungarian: Bács) is a town and municipality located in the South Bačka District of the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. The town has a population of 4,405, while the municipality has 11,431 inhabitants.[3] The entire geographical region between the rivers Danube and Tisza, today divided between Serbia and Hungary, was named Bačka after the town.[4]

Name

[edit]In Serbian, the town is known as Бач (Bač); in Slovak as Báč; in Croatian (Šokac) as Bač; in Hungarian as Bács; in German as Batsch; in Latin as Bach or Bacs; and in Turkish as Baç. Along with Serbian, Slovak and Hungarian are also in official use in the municipality administration.

In the ninth and tenth centuries, the name of the town was Bagasin.[5] The Byzantine writer John Kinnamos writes that Παγάτζιον is the most important city in Sirmium.[6] In 1154, the Arab geographer Idrisi mention it under name Bakasin and claim that "it is a famous city that was mentioned among old big cities".

The current name of the town was first recorded in 1094. In 1111 the parish was mentioned as Bache.[7] This name probably derived from the same personal name. In Serbian this name is written as Bač (Бач), in Hungarian as Bács, and in Romanian as Baci, although the Romanian population used this word as a title rather than as a name. The name is of uncertain origin and its existence was recorded among Vlachs, Slavs and Hungarians in the Middle Ages. The origin of the name could be Paleo-Balkanic,[8] Romanian, Slavic,[9] or Old Turkic.[10]

In the Romanian, Baci means "tenant, mountaineer or chieftain of the shepherd habitation in the mountain". The name could be spread into other languages by the Vlach shepherds. However, a similar name, Bača, was recorded among old Russians, which implies the possibility of Slavic origin.[11] Hungarian linguists claim that a similar but originally different Hungarian personal name was derived from the Old Turkic baya dignity in the form Bácsa, which later evolved into Bács.[12] It is not certain whether name of the town came from Vlach-Slavic or from the Hungarian name. Some Hungarian historians assume that the town was named after the first comes of the county, Bács ispán (Bač župan).[13] However, the existence of that person is not historically confirmed and his ethnic origin is uncertain.

There are several more places with same name (in North Macedonia, Slovenia, Montenegro and Albania), as well as a large number of place names beginning with letters "bač-" or "bács-" that are scattered all over the Balkans and Central Europe, as well as in some other regions.[14]

History

[edit]

Evidence show that the area was inhabited already in the younger Neolithic. The town later developed on an island in the meander of the Mostonga river and for centuries was accessible only by the wooden bridge. The river is channeled today as part of the Danube–Tisa–Danube Canal system and has two proper bridges, so the fortress and the old town are now on a dry land.[4]

Bač is one of the oldest towns in Vojvodina. The archeological research showed that an ancient Roman settlement existed in this area. Bač was first mentioned in 535 AD, in a letter written by Eastern Roman emperor Justinian. In 873 AD, the town was mentioned as Avar fortress, inhabited by both, Avars and Slavs. In this time, the Saint Methodius, a creator of the Slavic alphabet, converted to Christianity Slavs that lived in Bačka and Bač.

In the tenth century, this region became part of the Kingdom of Hungary. In the Middle Ages the town was the seat of the Bacsensis County. The foundation date of the county is a disputed question, some historians assume that it was one of the first counties of the Kingdom established by Stephen I but there is no documentary evidence of its existence in that time.[15] The first known prefect (comes) of the county was recorded in 1074 and his name was Vid.

King Ladislaus I made the town the seat of a new archbishopric in 1085. Previously historians assumed that Bač (Bacs) was a bishopric before that time. The first archbishop, Fabian (1085–1103) helped the king in the course of the campaign against Croatia and was rewarded with the title.[16]

Gyula Városy proved that king Ladislaus only moved the seat of the archbishopric of Kalocsa to Bač (Bacs), where he built a cathedral and established a chapter house around 1090. After 1135 the archbishops moved back to their former seat in Kalocsa. Later the diocese was called the "Archbishopric of Kalocsa-Bacs" (first mentioned in 1266).[17]

In 1154, the Arab geographer Idrisi wrote that Bač is a rich town with many merchants and craftsmen, a place with a lot of wheat and many "Greek scholars" which could refer to Orthodox priests and monks.

In the early 13th century. Ugrin Csák, Archbishop of Kalocsa, founded a hospital in Bač, as the first such facility in this part of Europe. Pope Gregory IX wrote about the "Bačka hospital" in 1234, as being open for the sick and poor.[4]

The town prospered with the Hungarian king Charles Robert I built the fortress in the first half of the 14th century. The fort developed and reached its full extension by the 16th century. From the 15th century, it was the most important Hungarian ramparts against the invading Ottoman forces. The pivotal moment was the disastrous Hungarian defeat in 1526 at the Battle of Mohacs, so the Ottomans conquered Bač in 1529.[4] During the war between Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary, in the 16th century, Serbian despot Stevan Berislavić successfully defended the Bač fortress from the Ottomans for a long time until the fortress finally fell.

During the Ottoman rule (16th-17th century), Bač was a seat of a kaza of Bač in Sanjak of Segedin. Since 1686 the town was under Habsburg. The fortress was mined with explosives in 1704, during the Rákóczi's War of Independence.[4] During the Austrian rule, many Germans settled in Bač during this time. After 1918, Bač was part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and subsequent South Slavic states. It was occupied by Hungary between 1941 and 1944 during World War II.

Characteristics

[edit]Bač Fortress is the best preserved medieval fort in Vojvodina. Section of Bač below the fortress is called Podgrađe. It consists of 36 houses in the typical lowland Vojvodina style and is protected, together with the fort, as the Spatial Cultural-Historical Units of Exceptional Importance. The section is directly accessed via the bridge across the canal and through the gate of Šiljak. The houses were built from the 18th to the 20th century, and residents are not allowed to change façades without prior consent from the institutes in charge of protection.[4]

The fort used to have 8 towers, but five are preserved today. There are four side towers and the tallest, over 20 m (66 ft), keep (donžon). The fortress was left to the elements from 18th to 20th century. First occasional archaeological explorations began in the 19th century, but the survey in earnest began in the 20th century.[4] Reconstruction and conservation project, which includes the exploration works, started in 2006. The fortress was restored, archaeological sections were conserved while the visitors center was open in the keep. The project was awarded the 2018 Europa Nostra Award, European Union prize for cultural heritage.[18]

One of the first modern pharmacies in this part of Vojvodina was open in Bač in 1828. It was founded by the Gebauer family, in their family home. The house still exists today and, though the interior is changed, the original display window and the stairs are preserved.[4]

Inhabited places

[edit]

Bač municipality includes the town of Bač (together with Mali Bač settlement) and the following villages:

- Bačko Novo Selo

- Bođani

- Vajska (together with Labudnjača and Živa settlements)

- Plavna

- Selenča

Media

[edit]Zvonik, a Roman Catholic magazine in Croatian, was founded in Bač in 1994.

Demographics

[edit]According to the 2022 census, the Bač municipality has 11,431 inhabitants.[3]

Historical population of the town

[edit]- 1961: 6,321

- 1971: 5,916

- 1981: 5,994

- 1991: 6,046

- 2011: 5,390

- 2022: 4,405

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 19,215 | — |

| 1953 | 21,050 | +1.84% |

| 1961 | 22,262 | +0.70% |

| 1971 | 19,348 | −1.39% |

| 1981 | 18,243 | −0.59% |

| 1991 | 17,249 | −0.56% |

| 2002 | 16,268 | −0.53% |

| 2011 | 14,405 | −1.34% |

| 2022 | 11,431 | −2.08% |

| Source: [19][3] | ||

Ethnic groups

[edit]The ethnic composition of the municipality:[3]

| Ethnic group | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| Serbs | 5,210 | 45.58% |

| Slovaks | 2,260 | 19.77% |

| Croats | 873 | 7.64% |

| Roma | 817 | 7.15% |

| Hungarians | 632 | 5.53% |

| Romanians | 151 | 1.32% |

| Muslims | 115 | 1.01% |

| Yugoslavs | 71 | 0.62% |

| Germans | 59 | 0.52% |

| Montenegrins | 24 | 0.21% |

| Others | 1,219 | 10.66% |

| Total | 11,431 |

Settlements with Serb ethnic majority are: Bač, Bačko Novo Selo, and Bođani. The settlement with Slovak ethnic majority is Selenča. Ethnically mixed settlements with relative Serb majority are Vajska and Plavna.

- Town

- Serbs (70.22%)

- Croats (8.36%)

- Hungarians (6.87%)

- Yugoslavs (4.47%)

- Slovaks (2.33%)

In the 17th century some Šokci Croats from Tuzla area migrated to Bač as refugees. Today they comprise less than 9% of the population.

Languages

[edit]According to the 2002 census, 66% of inhabitants of the Bač municipality speak Serbian as mother tongue. Other spoken languages include Slovak (20%), Romanian (4%), Hungarian (3%), Croatian (3%), and Romani (2%).

Serbian, Slovak, and Hungarian are officially used by municipal authorities.

Economy

[edit]The following table gives a preview of total number of employed people per their core activity (as of 2017):[20]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 184 |

| Mining | 2 |

| Processing industry | 454 |

| Distribution of power, gas and water | - |

| Distribution of water and water waste management | 96 |

| Construction | 170 |

| Wholesale and retail, repair | 391 |

| Traffic, storage and communication | 85 |

| Hotels and restaurants | 98 |

| Media and telecommunications | 10 |

| Finance and insurance | 21 |

| Property stock and charter | - |

| Professional, scientific, innovative and technical activities | 40 |

| Administrative and other services | 68 |

| Administration and social assurance | 158 |

| Education | 208 |

| Healthcare and social work | 105 |

| Art, leisure and recreation | 13 |

| Other services | 38 |

| Total | 2,143 |

Politics

[edit]Seats in the municipality parliament won in the 2012 local elections: [1]

- Democratic Party (9)

- Serbian Radical Party (2)

- SNS (6)

- Socialist Party of Serbia (5)

- LSV (3)

Sites of interest

[edit]- Bač Fortress;

- Bođani monastery;[4]

- Remains of the Turkish bath;[4]

- Kalvarija, memorial locality which consists of 12 pillars built in the 19th century and dedicated to the Christian saints;[4]

In 2017 the fortress was visited by 6,500 tourists. Other attractions include the Provala Lake, which was formed in the mid-20th century after a flood of the Danube, and a Berava stream, popular among the fishermen.[4]

Franciscan monastery

[edit]Origins can be traced to the 12th century.[4] In 1169, canons from the knighthood Order of the Holy Sepulchre built a small church in the Romanesque style. They used some building materials from much older previous edifices. Franciscans took over the church in 1300. In the second half of the 14th century, the Franciscans expanded it, forming a monastery. The inner corridors are designed to practically form the cubes. Franciscans added the tall bell tower and the monastery building, all in the Gothic style. A nice, Renaissance style sink is still preserved. The monastery was surrounded by a moat and the walls with towers, as was the usual for the monasteries in Hungary at the time. After the Ottoman conquest, the monastery was converted to a mosque in the 16th century. Some of the Ottoman adaptations still remain, like the south wall's mihrab - a niche in the wall that indicates the direction of Mecca. With the withdrawal of the Ottomans, the Franciscans returned in the 17th century.[21][22]

The present appearance of the complex dates from the 1734-1768 period. Visually, the monastery is today a combination of Gothic, Romanesque and Classicist architecture. The dining room still has a large doorknob from 1736. The monastery hosts a mechanical pipe organ, one of the oldest in this part of Europe. The original one was acquired in 1716 and was "like the one that Bach plays on". It was replaced with the larger and bigger one, which was made in 1826 and installed in 1827. It has 2 manuals, 16 registers, almost 1,000 organ pipes and is fully functional.[21][22]

Restoration of the monastery, dedicated to the Assumption of Mary, began in 2016. The remains of the old moat were discovered during the digging. During the reconstruction, one part of the monastery was adapted into the museum. A permanent archaeological exhibition was set, which shows the continuous habitation of the area, from the Prehistoric time until the 18th century. As the monastery holds numerous Franciscan relics, books, dishes, cloths and other items, they are also exhibited. The idea is to make this one part of the "diffused museum" within the scopes of the "Centuries in Bač" project, which would also include the fortress and the Serbian Orthodox Bođani monastery.[21] The reconstruction was finished in June 2019.[22]

Artifacts in the museum include bricks from the Roman period, which have the game Nine men's morris or the crosses carved on. Also exhibited are the 13th century remains of the fresco paintings, including the fresco Crucifixion of Jesus with Virgin Mary which was discovered accidentally in 2011. There is also an icon of Mary, Mother of God, painted in 1684, which is protected by the state in 1948 with some of the old and rare books from the monastery library.[22]

International relations

[edit]Twin towns — Sister cities

[edit]Bač is twinned with:

See also

[edit]- Municipalities of Serbia

- List of places in Serbia

- List of cities, towns and villages in Vojvodina

- Bačka

References

[edit]- ^ "Municipalities of Serbia, 2006". Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ^ "2022 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings: Ethnicity (data by municipalities and cities)" (PDF). Statistical Office of Republic Of Serbia, Belgrade. April 2023. ISBN 978-86-6161-228-2. Retrieved 2023-04-30.

- ^ a b c d "2022 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings" (PDF). Retrieved 2023-12-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Andrijana Cvetićanin (1 April 2018). "Tvrđava pod prolećnim snegom" [Fortress under the spring snow]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1070 (in Serbian). pp. 19–21.

- ^ Prof. Dr. Miloš Blagojević, Istorijski atlas, Beograd, 1999

- ^ Boris Stojkovski: Southern Hungary and Serbia in al-Idrisi’s Geography, page 8, trivent-publishing.eu.

- ^ 02BACS Archived January 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Milica Grković, Rečnik imena Banjskog, Dečanskog i Prizrenskog vlastelinstva u XIV veku, Beograd, 1986

- ^ Dr. Aleksa Ivić, Istorija Srba u Vojvodini, Novi Sad, 1929

- ^ A Pallas Nagy Lexikona Archived September 11, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ С. Б. Веселовскии, Ономастикон, древнерусские имена, прозвиша и фамилии, Москва, 1974

- ^ 403 Forbidden[permanent dead link]

- ^ A Délvidék Rövid Történelme Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Places in World that start with Bač Archived January 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "História 2000/04. - ZSOLDOS ATTILA: Szent István vármegyéi. Források, következtetések". Historia.hu. Archived from the original on 2012-02-04. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ^ "A Pallas nagy lexikona". Elib.hu. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ^ "Magyar Katolikus Lexikon". Lexikon.katolikus.hu. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ^ M.Đorđević (16 May 2018). "Tri nagrade za srpsko nasleđe" [Three awards for Serbian heritage]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 20.

- ^ "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ^ "ОПШТИНЕ И РЕГИОНИ У РЕПУБЛИЦИ СРБИЈИ, 2018" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ a b c Andrijana Cvetićanin (3 June 2018). "Занимљива Србија - Муѕејска поставка у фрањевачком самостану" [Interesting Serbia - Museum exhibition in the Franciscan monastery]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1079 (in Serbian). pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b c d Jelena Čalija (28 June 2019). Фрањевачки самостан - чувар историје [Franciscan monastery - guardian of history]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 8.

- ^ "Bač". Skgo.org. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

Bibliography

[edit]- Slobodan Ćurčić, Broj stanovnika Vojvodine, Novi Sad, 1996.

Gallery

[edit]-

The Orthodox Church in Bač

-

The new Orthodox Church in Mali Bač

-

The Franciscan Monastery