St Paul's Cathedral: Difference between revisions

→Description: moving pics into gallery |

m →West front: remoe extra pics |

||

| Line 332: | Line 332: | ||

==== West front ==== |

==== West front ==== |

||

{{more citations needed|section|date=October 2017}}<!--first three paragraphs have no citations--> |

{{more citations needed|section|date=October 2017}}<!--first three paragraphs have no citations--> |

||

[[File:St Pauls Cathedral West Front.jpg|thumb|St Paul's Cathedral west front dome street view]] |

|||

[[File:St_Pauls_Cathedral_from_West_-_Feb_2007.jpg|thumb|West front]] |

|||

For the Renaissance architect designing the west front of a large church or cathedral, the universal problem was how to use a facade to unite the high central nave with the lower aisles in a visually harmonious whole. Since [[Leon Battista Alberti|Alberti]]'s additions to [[Santa Maria Novella]] in Florence, this was usually achieved by the simple expedient of linking the sides to the centre with large brackets. This is the solution that Wren saw employed by Mansart at Val-de-Grâce. Another feature employed by Mansart was a boldly projecting Classical portico with paired columns. Wren faced the additional challenge of incorporating towers into the design, as had been planned at St Peter's Basilica. At St Peter's, [[Carlo Maderno]] had solved this problem by constructing a [[narthex]] and stretching a huge screen facade across it, differentiated at the centre by a pediment. The towers at St Peter's were not built above the parapet. |

For the Renaissance architect designing the west front of a large church or cathedral, the universal problem was how to use a facade to unite the high central nave with the lower aisles in a visually harmonious whole. Since [[Leon Battista Alberti|Alberti]]'s additions to [[Santa Maria Novella]] in Florence, this was usually achieved by the simple expedient of linking the sides to the centre with large brackets. This is the solution that Wren saw employed by Mansart at Val-de-Grâce. Another feature employed by Mansart was a boldly projecting Classical portico with paired columns. Wren faced the additional challenge of incorporating towers into the design, as had been planned at St Peter's Basilica. At St Peter's, [[Carlo Maderno]] had solved this problem by constructing a [[narthex]] and stretching a huge screen facade across it, differentiated at the centre by a pediment. The towers at St Peter's were not built above the parapet. |

||

Revision as of 15:33, 12 January 2024

| St Paul's | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle | |

Aerial view of the St Paul's Cathedral | |

Interactive fullscreen map | |

| 51°30′50″N 0°05′54″W / 51.5138°N 0.0983°W | |

| Location | London, EC4 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholicism |

| Website | stpauls.co.uk |

| History | |

| Status | Active |

| Consecrated | 1697 |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Grade I Listed |

| Previous cathedrals | 4 |

| Architect(s) | Sir Christopher Wren |

| Style | English Baroque |

| Years built | 1675–1710 |

| Groundbreaking | 1675 |

| Completed | 1710 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 518 ft (158 m) |

| Nave width | 121 ft (37 m) |

| Width across transepts | 246 ft (75 m) |

| Height | 365 ft (111 m) |

| Dome height (outer) | 278 ft (85 m)[citation needed] |

| Dome height (inner) | 225 ft (69 m)[1] |

| Dome diameter (outer) | 112 ft (34 m)[citation needed] |

| Dome diameter (inner) | 102 ft (31 m)[1] |

| Number of towers | 2 |

| Tower height | 221 ft (67 m)[1] |

| Administration | |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | London (since 604) |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Sarah Mullally |

| Dean | Andrew Tremlett |

| Precentor | James Milne |

| Chancellor | Paula Gooder (lay reader) |

| Canon Treasurer | vacant |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Andrew Carwood |

| Organist(s) | William Fox (acting) |

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London. Its dedication in honour of Paul the Apostle dates back to the original church on this site, founded in AD 604.[2] The present structure, which was completed in 1710, is a Grade I listed building that was designed in the English Baroque style by Sir Christopher Wren. The cathedral's construction was part of a major rebuilding programme initiated in the aftermath of the Great Fire of London.[3] The earlier Gothic cathedral (Old St Paul's Cathedral), largely destroyed in the Great Fire, was a central focus for medieval and early modern London, including Paul's walk and St Paul's Churchyard, being the site of St Paul's Cross.

The cathedral is one of the most famous and recognisable sights of London. Its dome, surrounded by the spires of Wren's City churches, has dominated the skyline for over 300 years. At 365 ft (111 m) high, it was the tallest building in London from 1710 to 1963. The dome is still one of the highest in the world. St Paul's is the second-largest church building in area in the United Kingdom, after Liverpool Cathedral.

Services held at St Paul's have included the funerals of Admiral Lord Nelson, the Duke of Wellington, Winston Churchill and Margaret Thatcher; jubilee celebrations for Queen Victoria; an inauguration service for the Metropolitan Hospital Sunday Fund;[4] peace services marking the end of the First and Second World Wars; the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer; the launch of the Festival of Britain; and the thanksgiving services for the Silver, Golden, Diamond, and Platinum Jubilees and the 80th and 90th birthdays of Queen Elizabeth II. St Paul's Cathedral is the central subject of much promotional material, as well as of images of the dome surrounded by the smoke and fire of the Blitz.[5] The cathedral is a working church with hourly prayer and daily services. The tourist entry fee at the door is £23 for adults (January 2023, cheaper if booked online), but no charges are made to worshippers attending advertised services.[6]

The nearest London Underground station is St Paul's, which is 130 yards (120 m) away from St Paul's Cathedral.[7]

History

Before the cathedral

The location of Londinium's original cathedral is unknown, but legend and medieval tradition claims it was St Peter upon Cornhill. St Paul is an unusual attribution for a cathedral, and suggests there was another one in the Roman period. Legends of St Lucius link St Peter upon Cornhill as the centre of the Roman Londinium Christian community. It stands upon the highest point in the area of old Londinium, and it was given pre-eminence in medieval procession on account of the legends. There is, however, no other reliable evidence and the location of the site on the Forum makes it difficult for it to fit the legendary stories. In 1995, a large fifth-century building on Tower Hill was excavated, and has been claimed as a Roman basilica, possibly a cathedral, although this is speculative. [8][9]

The Elizabethan antiquarian William Camden argued that a temple to the goddess Diana had stood during Roman times on the site occupied by the medieval St Paul's Cathedral.[10] Wren reported that he had found no trace of any such temple during the works to build the new cathedral after the Great Fire, and Camden's hypothesis is no longer accepted by modern archaeologists.[11]

Pre-Norman cathedral

There is evidence for Christianity in London during the Roman period, but no firm evidence for the location of churches or a cathedral. Bishop Restitutus is said to have represented London at the Council of Arles in 314 AD.[12] A list of the 16 "archbishops" of London was recorded by Jocelyn of Furness in the 12th century, claiming London's Christian community was founded in the second century under the legendary King Lucius and his missionary saints Fagan, Deruvian, Elvanus and Medwin. None of that is considered credible by modern historians but, although the surviving text is problematic, either Bishop Restitutus or Adelphius at the 314 Council of Arles seems to have come from Londinium.[a]

Bede records that in AD 604 Augustine of Canterbury consecrated Mellitus as the first bishop to the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Saxons and their king, Sæberht. Sæberht's uncle and overlord, Æthelberht, king of Kent, built a church dedicated to St Paul in London, as the seat of the new bishop.[13] It is assumed, although not proved, that this first Anglo-Saxon cathedral stood on the same site as the later medieval and the present cathedrals.

On the death of Sæberht in about 616, his pagan sons expelled Mellitus from London, and the East Saxons reverted to paganism. The fate of the first cathedral building is unknown. Christianity was restored among the East Saxons in the late seventh century and it is presumed that either the Anglo-Saxon cathedral was restored or a new building erected as the seat of bishops such as Cedd, Wine and Erkenwald, the last of whom was buried in the cathedral in 693.

Earconwald was consecrated bishop of London in 675, and is said to have bestowed great cost on the fabric, and in later times he almost occupied the place of traditionary, founder: the veneration paid to him is second only to that which was rendered to St. Paul.[14] Erkenwald would become a subject of the important High Medieval poem St Erkenwald.

King Æthelred the Unready was buried in the cathedral on his death in 1016; the tomb is now lost. The cathedral was burnt, with much of the city, in a fire in 1087, as recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.[15]

Old St Paul's

The fourth St Paul's, generally referred to as Old St Paul's, was begun by the Normans after the 1087 fire. A further fire in 1135 disrupted the work, and the new cathedral was not consecrated until 1240. During the period of construction, the style of architecture had changed from Romanesque to Gothic and this was reflected in the pointed arches and larger windows of the upper parts and East End of the building. The Gothic ribbed vault was constructed, like that of York Minster, of wood rather than stone, which affected the ultimate fate of the building.[citation needed]

An enlargement programme commenced in 1256. This "New Work" was consecrated in 1300 but not complete until 1314. During the later Medieval period St Paul's was exceeded in length only by the Abbey Church of Cluny and in the height of its spire only by Lincoln Cathedral and St. Mary's Church, Stralsund. Excavations by Francis Penrose in 1878 showed that it was 585 feet (178 m) long and 100 feet (30 m) wide (290 feet (88 m) across the transepts and crossing). The spire was about 489 feet (149 m) in height.[citation needed] By the 16th century the building was deteriorating.

The English Reformation under Henry VIII and Edward VI (accelerated by the Chantries Acts) led to the destruction of elements of the interior ornamentation and the chapels, shrines, and chantries. This would come to include the removal of the cathedral's collection of relics, which by the sixteenth century was understood to include:[16][17]

- the body of St Erkenwald

- both arms of St Mellitus

- a knife thought to belong to Jesus

- hair of Mary Magdalen

- blood of St Paul

- milk of the Virgin Mary

- the head of St John

- the skull of Thomas Becket

- the head and jaw of King Ethelbert

- part of the wood of the cross,

- a stone of the Holy Sepulchre,

- a stone from the spot of the Ascension, and

- some bones of the eleven thousand virgins of Cologne.

In October 1538, an image of St Erkenwald, probably from the shrine, was delivered to the master of the king's jewels. Other images may have survived, at least for a time. More systematic iconoclasm happened in the reign of Edward VI: the Grey Friar's Chronicle reports that the rood and other images were destroyed in November 1547.

In late 1549, at the height of the iconoclasm of the reformation, Sir Rowland Hill altered the route of his Lord Mayor's day procession and said a de profundis at the tomb of Erkenwald.[18] Later in Hill's mayoralty of (1550)[19] the high altar of St Paul's was removed[20] overnight[21] to be destroyed,[22] an occurrence that provoked a fight in which a man was killed.[23] Hill had ordered, unusually for the time, that St Barnabus's Day would not be kept as a public holiday ahead of these events.

Three years later, by October 1553, "Alle the alteres and chappelles in alle Powlles churche" were taken down.[19] In August, 1553, the dean and chapter were cited to appear before Queen Mary's commissioners.[14]

Some of the buildings in the St Paul's churchyard were sold as shops and rental properties, especially to printers and booksellers. In 1561 the spire was destroyed by a lightning strike, an event that Roman Catholic writers claimed was a sign of God's judgment on England's Protestant rulers. Bishop James Pilkington preached a sermon in response, claiming that the lightning strike was a judgement for the irreverent use of the cathedral building.[24] Immediate steps were taken to repair the damage, with the citizens of London and the clergy offering money to support the rebuilding.[25] However, the cost of repairing the building properly was too great for a country and city recovering from a trade depression. Instead, the roof was repaired and a timber "roo"’[clarification needed] put on the steeple.

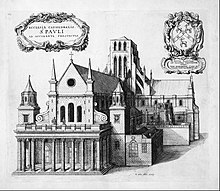

In the 1630s a west front was added to the building by England's first classical architect, Inigo Jones. There was much defacing and mistreatment of the building by Parliamentarian forces during the Civil War, and the old documents and charters were dispersed and destroyed.[26][page needed] During the Commonwealth, those churchyard buildings that were razed supplied ready-dressed building material for construction projects, such as the Lord Protector's city palace, Somerset House. Crowds were drawn to the north-east corner of the churchyard, St Paul's Cross, where open-air preaching took place.[citation needed]

In the Great Fire of London of 1666, Old St Paul's was gutted.[27] While it might have been possible to reconstruct it, a decision was taken to build a new cathedral in a modern style. This course of action had been proposed even before the fire.

Present St Paul's

The task of designing a replacement structure was officially assigned to Sir Christopher Wren on 30 July 1669.[28] He had previously been put in charge of the rebuilding of churches to replace those lost in the Great Fire. More than 50 city churches are attributable to Wren. Concurrent with designing St Paul's, Wren was engaged in the production of his five Tracts on Architecture.[29]

Wren had begun advising on the repair of the Old St Paul's in 1661, five years before the fire in 1666.[30] The proposed work included renovations to interior and exterior to complement the classical facade designed by Inigo Jones in 1630.[31] Wren planned to replace the dilapidated tower with a dome, using the existing structure as a scaffold. He produced a drawing of the proposed dome which shows his idea that it should span nave and aisles at the crossing.[32] After the Fire, it was at first thought possible to retain a substantial part of the old cathedral, but ultimately the entire structure was demolished in the early 1670s.

In July 1668 Dean William Sancroft wrote to Wren that he was charged by the Archbishop of Canterbury, in agreement with the Bishops of London and Oxford, to design a new cathedral that was "Handsome and noble to all the ends of it and to the reputation of the City and the nation".[33] The design process took several years, but a design was finally settled and attached to a royal warrant, with the proviso that Wren was permitted to make any further changes that he deemed necessary. The result was the present St Paul's Cathedral, still the second largest church in Britain, with a dome proclaimed as the finest in the world.[34] The building was financed by a tax on coal, and was completed within its architect's lifetime with many of the major contractors engaged for the duration.

The "topping out" of the cathedral (when the final stone was placed on the lantern) took place on 26 October 1708, performed by Wren's son Christopher Jr and the son of one of the masons.[35] The cathedral was declared officially complete by Parliament on 25 December 1711 (Christmas Day).[36] In fact, construction continued for several years after that, with the statues on the roof added in the 1720s. In 1716 the total costs amounted to £1,095,556[37] (£207 million in 2023).[38]

Consecration

On 2 December 1697, 31 years and 3 months after the Great Fire destroyed Old St Paul's, the new cathedral was consecrated for use. The Right Reverend Henry Compton, Bishop of London, preached the sermon. It was based on the text of Psalm 122, "I was glad when they said unto me: Let us go into the house of the Lord." The first regular service was held on the following Sunday.

Opinions of Wren's cathedral differed, with some loving it: "Without, within, below, above, the eye / Is filled with unrestrained delight",[39][page needed] while others hated it: "There was an air of Popery about the gilded capitals, the heavy arches ... They were unfamiliar, un-English ...".[40]

Since 1900

Suffragette terror attacks

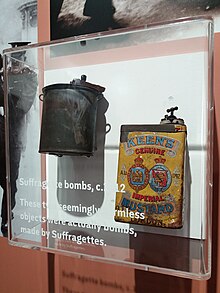

St. Paul's was the target of two suffragette bombing attacks in 1913 and 1914 respectively, which nearly caused the destruction of the cathedral. This was as part of the suffragette bombing and arson campaign between 1912 and 1914, in which suffragettes from the Women's Social and Political Union, as part of their campaign for women's suffrage, carried out a series of politically motivated bombings and arson nationwide.[41] Churches were explicitly targeted by the suffragettes as they believed the Church of England was complicit in reinforcing opposition to women's suffrage.[42] Between 1913 and 1914, 32 churches across Britain were attacked.[43]

The first attack on St. Paul's occurred on 8 May 1913, at the start of a sermon.[44] A bomb was heard ticking and discovered as people were entering the cathedral.[44] It was made out of potassium nitrate.[44] Had it exploded, the bomb likely would have destroyed the historic bishop's throne and other parts of the cathedral.[44] The remains of the device, which was made partly out of a mustard tin, are now on display at the City of London Police Museum.[44]

A second bombing of the cathedral by the suffragettes was attempted on 13 June 1914, however the bomb was again discovered before it could explode.[41] This attempted bombing occurred two days after a bomb had exploded at Westminster Abbey, which damaged the Coronation Chair and caused a mass panic for the exits.[44] Several other churches were bombed at this time, such as St Martin-in-the-Fields church in Trafalgar Square and the Metropolitan Tabernacle.[41]

War damage

The cathedral survived the Blitz although struck by bombs on 10 October 1940 and 17 April 1941. The first strike destroyed the high altar, while the second strike on the north transept left a hole in the floor above the crypt.[45][46] The latter bomb is believed to have detonated in the upper interior above the north transept and the force was sufficient to shift the entire dome laterally by a small amount.[47][48]

On 12 September 1940 a time-delayed bomb that had struck the cathedral was successfully defused and removed by a bomb disposal detachment of Royal Engineers under the command of Temporary Lieutenant Robert Davies. Had this bomb detonated, it would have totally destroyed the cathedral; it left a 100-foot (30 m) crater when later remotely detonated in a secure location.[49] As a result of this action, Davies and Sapper George Cameron Wylie were each awarded the George Cross.[50] Davies' George Cross and other medals are on display at the Imperial War Museum, London.

One of the best known images of London during the war was a photograph of St Paul's taken on 29 December 1940 during the "Second Great Fire of London" by photographer Herbert Mason,[b] from the roof of a building in Tudor Street showing the cathedral shrouded in smoke. Lisa Jardine of Queen Mary, University of London, has written:[45]

Wreathed in billowing smoke, amidst the chaos and destruction of war, the pale dome stands proud and glorious—indomitable. At the height of that air-raid, Sir Winston Churchill telephoned the Guildhall to insist that all fire-fighting resources be directed at St Paul's. The cathedral must be saved, he said, damage to the fabric would sap the morale of the country.

Post-war

On 29 July 1981, the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer was held at the cathedral. The couple selected St Paul's over Westminster Abbey, the traditional site of royal weddings, because the cathedral offered more seating.[51]

Extensive copper, lead and slate renovation work was carried out on the Dome in 1996 by John B. Chambers. A 15-year restoration project—one of the largest ever undertaken in the UK—was completed on 15 June 2011.[52]

Occupy London

In October 2011 an anti-capitalism Occupy London encampment was established in front of the cathedral, after failing to gain access to the London Stock Exchange at Paternoster Square nearby. The cathedral's finances were affected by the ensuing closure. It was claimed that the cathedral was losing revenue of £20,000 per day.[53] Canon Chancellor Giles Fraser resigned, asserting his view that "evicting the anti-capitalist activists would constitute violence in the name of the Church".[54] The Dean of St Paul's, the Right Revd Graeme Knowles, then resigned too.[55] The encampment was evicted at the end of February 2012, by court order and without violence, as a result of legal action by the City of London Corporation.[56]

2019 terrorist plot

On 10 October 2019, Safiyya Amira Shaikh, a Muslim convert, was arrested following an MI5 and Metropolitan Police investigation. In September 2019, she had taken photos of the cathedral's interior. While trying to radicalise others using the Telegram messaging software, she planned to attack the cathedral and other targets such as a hotel and a train station using explosives. Shaikh pleaded guilty and was sentenced to life imprisonment.[57]

National events

The size and location of St Paul's has made it an ideal setting for Christian services marking great national events. The opportunity for long processions culminating in the dramatic approach up Ludgate Hill, the open area and steps at the west front, the great nave and the space under the dome are all well suited for ceremonial occasions. St Paul's can seat many more people than any other church in London, and in past centuries, the erection of temporary wooden galleries inside allowed for congregations exceeding 10,000. In 1935, the dean, Walter Matthews, wrote:[58]

No description in words can convey an adequate idea of the majestic beauty of a solemn national religious ceremony in St Paul's. It is hard to believe that there is any other building in the world that is so well adapted to be the setting of such symbolical acts of communal worship.

National events attended by the royal family, government ministers and officers of state include national services of thanksgiving, state funerals and a royal wedding. Some of the most notable examples are:

- Thanksgiving service for the Acts of Union 1707, 1 May 1707

- State funeral of Horatio Nelson, 9 January 1806

- State funeral of the Duke of Wellington, 18 November 1852

- Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria, 22 June 1897

- Thanksgiving service for the Treaty of Versailles, 6 July 1919

- Silver Jubilee of George V, 6 May 1935

- Thanksgiving services for VE Day and VJ Day, 13 May and 19 August 1945

- Silver Jubilee of Elizabeth II, 7 June 1977

- Wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer, 29 July 1981

- Golden Jubilee of Elizabeth II, 4 June 2002

- Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II, 5 June 2012

- Ceremonial funeral of Margaret Thatcher, 17 April 2013

- Thanksgiving service for the Queen's 90th Birthday, 10 June 2016

- Platinum Jubilee National Service of Thanksgiving, 3 June 2022

Ministry and functions

St Paul's Cathedral is a busy church with four or five services every day, including Matins, Eucharist and Evening Prayer or Choral Evensong.[59] In addition, the cathedral has many special services associated with the City of London, its corporation, guilds and institutions. The cathedral, as the largest church in London, also has a role in many state functions such as the service celebrating the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II. The cathedral is generally open daily to tourists and has a regular programme of organ recitals and other performances.[60] The Bishop of London is Sarah Mullally, whose appointment was announced in December 2017 and whose enthronement took place in May 2018.

Dean and chapter

The cathedral chapter is currently composed of seven individuals: the dean, three residentiary canons (one of whom is, exceptionally, lay), one "additional member of chapter and canon non-residentiary" (ordained), and two lay canons. Each has a different responsibility in the running of the cathedral.[61] As of October 2022:[62]

- Dean — Andrew Tremlett (since 25 September 2022)[63]

- Precentor — James Milne (since 9 May 2019)[64]

- Treasurer — vacant

- Chancellor — Paula Gooder (since 9 May 2019;[64] lay reader since 23 February 2019)[65]

- Steward — Neil Evans (since June 2022)[66]

- Additional member of chapter and canon non-residentiary — Sheila Watson (since January 2017).[67]

- Lay Canon — Pamela (Pim) Jane Baxter[68] (since March 2014). Deputy Director at the National Portrait Gallery, with experience in opera, theatre and the visual arts.

- Lay Canon — Sheila Nicoll (since October 2018). She is Head of Public Policy at Schroder Investment Management.[69]

- Lay Canon — Clement Hutton-Mills (since March 2021). He is also a Managing Director at Goldman Sachs.

- Lay Canon — Gillian Bowen (since June 2022). She is Chief Executive Officer of YMCA London City and North and is a magistrate.[66]

Minor canons and priest vicar

Director of Music

The Director of Music is Andrew Carwood.[70] Carwood was appointed to succeed Malcolm Archer as Director of Music, taking up the post in September 2007.[71] He is the first non-organist to hold the post since the 12th century.

Organs

An organ was commissioned from Bernard Smith in 1694.[72][73]

In 1862 the organ from the Panopticon of Science and Art (the Panopticon Organ) was installed in a gallery over the south transept door.[74]

The Grand Organ was completed in 1872, and the Panopticon Organ moved to the Victoria Rooms in Clifton in 1873.

The Grand Organ is the fifth-largest in Great Britain,[c][75] in terms of number of pipes (7,256),[76] with 5 manuals, 136 ranks of pipes and 137 stops, principally enclosed in an impressive case designed in Wren's workshop and decorated by Grinling Gibbons.[77]

Details of the organ can be found online at the National Pipe Organ Register.[78]

Choir

St Paul's Cathedral has a full professional choir, which sings regularly at services. The earliest records of the choir date from 1127. The present choir consists of up to 30 boy choristers, eight probationers and the vicars choral, 12 professional singers. In February 2017 the cathedral announced the appointment of the first female vicar choral, Carris Jones (a mezzo-soprano), to take up the role in September 2017.[79][80][81] In 2022, it was announced that girls would be admitted to a cathedral choir in 2025.[82]

During school terms the choir sings Evensong six times per week, the service on Mondays being sung by a visiting choir (or occasionally said) and that on Thursdays being sung by the vicars choral alone. On Sundays the choir also sings at Mattins and the 11:30 am Eucharist.[70]

Many distinguished musicians have been organists, choir masters and choristers at St Paul's Cathedral, including the composers John Redford, Thomas Morley, John Blow, Jeremiah Clarke, Maurice Greene and John Stainer, while well-known performers have included Alfred Deller, John Shirley-Quirk and Anthony Way as well as the conductors Charles Groves and Paul Hillier and the poet Walter de la Mare.

Wren's cathedral

Development of the design

Sir Christopher Wren

Said, "I am going to dine with some men.

If anyone calls,

Say I'm designing Saint Paul's."

A clerihew by Edmund Clerihew Bentley

In designing St Paul's, Christopher Wren had to meet many challenges. He had to create a fitting cathedral to replace Old St Paul's, as a place of worship and as a landmark within the City of London. He had to satisfy the requirements of the church and the tastes of a royal patron, as well as respecting the essentially medieval tradition of English church building which developed to accommodate the liturgy. Wren was familiar with contemporary Renaissance and Baroque trends in Italian architecture and had visited France, where he studied the work of François Mansart.

Wren's design developed through five general stages. The first survives only as a single drawing and part of a model. The scheme (usually called the First Model Design) appears to have consisted of a circular domed vestibule (possibly based on the Pantheon in Rome) and a rectangular church of basilica form. The plan may have been influenced by the Temple Church. It was rejected because it was not thought "stately enough".[83] Wren's second design was a Greek cross,[84] which was thought by the clerics not to fulfil the requirements of Anglican liturgy.[85]

Wren's third design is embodied in the "Great Model" of 1673. The model, made of oak and plaster, cost over £500 (approximately £32,000 today) and is over 13 feet (4 m) tall and 21 feet (6 m) long.[86] This design retained the form of the Greek-Cross design but extended it with a nave. His critics, members of a committee commissioned to rebuild the church, and clergy decried the design as too dissimilar to other English churches to suggest any continuity within the Church of England. Another problem was that the entire design would have to be completed all at once because of the eight central piers that supported the dome, instead of being completed in stages and opened for use before construction finished, as was customary. The Great Model was Wren's favourite design; he thought it a reflection of Renaissance beauty.[87] After the Great Model, Wren resolved not to make further models and not to expose his drawings publicly, which he found did nothing but "lose time, and subject [his] business many times, to incompetent judges".[85] The Great Model survives and is housed within the cathedral itself.

Wren's fourth design is known as the Warrant design because it received a Royal warrant for the rebuilding. In this design Wren sought to reconcile Gothic, the predominant style of English churches, to a "better manner of architecture". It has the longitudinal Latin Cross plan of a medieval cathedral. It is of 1+1⁄2 storeys and has classical porticos at the west and transept ends, influenced by Inigo Jones's addition to Old St Paul's.[85] It is roofed at the crossing by a wide shallow dome supporting a drum with a second cupola, from which rises a spire of seven diminishing stages. Vaughan Hart has suggested that influence in the design of the spire may have been drawn from the oriental pagoda. Not used at St Paul's, the concept was applied in the spire of St Bride's, Fleet Street.[29][page needed] This plan was rotated slightly on its site so that it aligned, not with true east, but with sunrise on Easter of the year construction began. This small change in configuration was informed by Wren's knowledge of astronomy.[31]

Final design

The final design as built differs substantially from the official Warrant design.[88][page needed] Wren received permission from the king to make "ornamental changes" to the submitted design, and Wren took great advantage of this. Many of these changes were made over the course of the thirty years as the church was constructed, and the most significant was to the dome: "He raised another structure over the first cupola, a cone of brick, so as to support a stone lantern of an elegant figure ... And he covered and hid out of sight the brick cone with another cupola of timber and lead; and between this and the cone are easy stairs that ascend to the lantern" (Christopher Wren, son of Sir Christopher Wren). The final design was strongly rooted in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. The saucer domes over the nave were inspired by François Mansart's Church of the Val-de-Grâce, which Wren had seen during a trip to Paris in 1665.[87]

The date of the laying of the first stone of the cathedral is disputed. One contemporary account says it was 21 June 1675, another 25 June and a third on 28 June. There is, however, general agreement that it was laid in June 1675. Edward Strong later claimed it was laid by his elder brother, Thomas Strong, one of the two master stonemasons appointed by Wren at the beginning of the work.[89]

Structural engineering

Wren's challenge was to construct a large cathedral on the relatively weak clay soil of London. St Paul's is unusual among cathedrals in that there is a crypt, the largest in Europe, under the entire building rather than just under the eastern end.[90] The crypt serves a structural purpose. Although it is extensive, half the space of the crypt is taken up by massive piers which spread the weight of the much slimmer piers of the church above. While the towers and domes of most cathedrals are supported on four piers, Wren designed the dome of St Paul's to be supported on eight, achieving a broader distribution of weight at the level of the foundations.[91] The foundations settled as the building progressed, and Wren made structural changes in response.[92]

One of the design problems that confronted Wren was to create a landmark dome, tall enough to visually replace the lost tower of St Paul's, while at the same time appearing visually satisfying when viewed from inside the building. Wren planned a double-shelled dome, as at St Peter's Basilica.[93] His solution to the visual problem was to separate the heights of the inner and outer dome to a much greater extent than had been done by Michelangelo at St Peter's, drafting both as catenary curves, rather than as hemispheres. Between the inner and outer domes, Wren inserted a brick cone which supports both the timbers of the outer, lead-covered dome and the weight of the ornate stone lantern that rises above it. Both the cone and the inner dome are 18 inches thick and are supported by wrought iron chains at intervals in the brick cone and around the cornice of the peristyle of the inner dome to prevent spreading and cracking.[91][94]

The Warrant Design showed external buttresses on the ground floor level. These were not a classical feature and were one of the first elements Wren changed. Instead he made the walls of the cathedral particularly thick to avoid the need for external buttresses altogether. The clerestory and vault are reinforced with flying buttresses, which were added at a relatively late stage in the design to give extra strength.[95] These are concealed behind the screen wall of the upper story, which was added to keep the building's classical style intact, to add sufficient visual mass to balance the appearance of the dome and which, by its weight, counters the thrust of the buttresses on the lower walls.[91][93]

Designers, builders and craftsmen

During the extensive period of design and rationalisation, Wren employed from 1684 Nicholas Hawksmoor as his principal assistant.[29][page needed] Between 1696 and 1711 William Dickinson was measuring clerk.[96] Joshua Marshall (until his early death in 1678) and Thomas and his brother Edward Strong were master masons, the latter two working on the construction for its entirety. John Langland was the master carpenter for over thirty years.[77] Grinling Gibbons was the chief sculptor, working in both stone on the building itself, including the pediment of the north portal, and wood on the internal fittings.[77] The sculptor Caius Gabriel Cibber created the pediment of the south transept[97] while Francis Bird was responsible for the relief in the west pediment depicting the Conversion of St Paul, as well as the seven large statues on the west front.[98] The floor was paved by William Dickinson in black and white marble in 1709–10[99] Jean Tijou was responsible for the decorative wrought ironwork of gates and balustrades.[77] The ball and cross on the dome were provided by an armorer, Andrew Niblett.[100] Following the war damage mentioned above, many craftsmen were employed to restore the wood carvings and stone work that had been destroyed by the bomb impact. One of particular note is Master Carver, Gino Masero who was commissioned to carve the replacement figure of Christ, an eight-foot sculpture in lime which currently stands on the High Altar.[101]

Description

St Paul's Cathedral is built in a restrained Baroque style which represents Wren's rationalisation of the traditions of English medieval cathedrals with the inspiration of Palladio, the classical style of Inigo Jones, the baroque style of 17th century Rome, and the buildings by Mansart and others that he had seen in France.[102][page needed] It is particularly in its plan that St Paul's reveals medieval influences.[91] Like the great medieval cathedrals of York and Winchester, St Paul's is comparatively long for its width, and has strongly projecting transepts. It has much emphasis on its facade, which has been designed to define rather than conceal the form of the building behind it. In plan, the towers jut beyond the width of the aisles as they do at Wells Cathedral. Wren's uncle Matthew Wren was the Bishop of Ely, and, having worked for his uncle, Wren was familiar with the unique octagonal lantern tower over the crossing of Ely Cathedral, which spans the aisles as well as the central nave, unlike the central towers and domes of most churches. Wren adapted this characteristic in designing the dome of St Paul's.[91] In section St Paul's also maintains a medieval form, having the aisles much lower than the nave, and a defined clerestory.[citation needed]

Exterior

The most renowned exterior feature is the dome, which rises 365 feet (111 m) to the cross at its summit,[103] and dominates views of the city. The height of 365 feet is explained by Wren's interest in astronomy. Until the late 20th century St Paul's was the tallest building on the City skyline, designed to be seen surrounded by the delicate spires of Wren's other city churches. The dome is described by Sir Banister Fletcher as "probably the finest in Europe", by Helen Gardner as "majestic", and by Sir Nikolaus Pevsner as "one of the most perfect in the world". Sir John Summerson said that Englishmen and "even some foreigners" consider it to be without equal.[34][104][105][106]

Dome

Wren drew inspiration from Michelangelo's dome of St Peter's Basilica, and that of Mansart's Church of the Val-de-Grâce, which he had visited.[106] Unlike those of St Peter's and Val-de-Grâce, the dome of St Paul's rises in two clearly defined storeys of masonry, which, together with a lower unadorned footing, equal a height of about 95 feet. From the time of the Greek Cross Design it is clear that Wren favoured a continuous colonnade (peristyle) around the drum of the dome, rather than the arrangement of alternating windows and projecting columns that Michelangelo had used and which had also been employed by Mansart.[105] Summerson suggests that he was influenced by Bramante's "Tempietto" in the courtyard of San Pietro in Montorio.[107] In the finished structure, Wren creates a diversity and appearance of strength by placing niches between the columns in every fourth opening.[107] The peristyle serves to buttress both the inner dome and the brick cone which rises internally to support the lantern.

Above the peristyle rises the second stage surrounded by a balustraded balcony called the "Stone Gallery". This attic stage is ornamented with alternating pilasters and rectangular windows which are set just below the cornice, creating a sense of lightness. Above this attic rises the dome, covered with lead, and ribbed in accordance with the spacing of the pilasters. It is pierced by eight light wells just below the lantern, but these are barely visible. They allow light to penetrate through openings in the brick cone, which illuminates the interior apex of this shell, partly visible from within the cathedral through the ocular opening of the lower dome.[91]

The lantern, like the visible masonry of the dome, rises in stages. The most unusual characteristic of this structure is that it is of square plan, rather than circular or octagonal. The tallest stage takes the form of a tempietto with four columned porticos facing the cardinal points. Its lowest level is surrounded by the "Golden Gallery" and its upper level supports a small dome from which rises a cross on a golden ball. The total weight of the lantern is about 850 tons.[34]

West front

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

For the Renaissance architect designing the west front of a large church or cathedral, the universal problem was how to use a facade to unite the high central nave with the lower aisles in a visually harmonious whole. Since Alberti's additions to Santa Maria Novella in Florence, this was usually achieved by the simple expedient of linking the sides to the centre with large brackets. This is the solution that Wren saw employed by Mansart at Val-de-Grâce. Another feature employed by Mansart was a boldly projecting Classical portico with paired columns. Wren faced the additional challenge of incorporating towers into the design, as had been planned at St Peter's Basilica. At St Peter's, Carlo Maderno had solved this problem by constructing a narthex and stretching a huge screen facade across it, differentiated at the centre by a pediment. The towers at St Peter's were not built above the parapet.

Wren's solution was to employ a Classical portico, as at Val-de-Grâce, but rising through two storeys, and supported on paired columns. The remarkable feature here is that the lower story of this portico extends to the full width of the aisles, while the upper section defines the nave that lies behind it. The gaps between the upper stage of the portico and the towers on either side are bridged by a narrow section of wall with an arch-topped window.

The towers stand outside the width of the aisles, but screen two chapels located immediately behind them. The lower parts of the towers continue the theme of the outer walls, but are differentiated from them in order to create an appearance of strength. The windows of the lower story are smaller than those of the side walls and are deeply recessed, a visual indication of the thickness of the wall. The paired pilasters at each corner project boldly.

Above the main cornice, which unites the towers with the portico and the outer walls, the details are boldly scaled, in order to read well from the street below and from a distance. The towers rise above the cornice from a square block plinth which is plain apart from large oculi, that on the south being filled by the clock, while that on the north is void. The towers are composed of two complementary elements, a central cylinder rising through the tiers in a series of stacked drums, and paired Corinthian columns at the corners, with buttresses above them, which serve to unify the drum shape with the square plinth on which it stands. The entablature above the columns breaks forward over them to express both elements, tying them together in a single horizontal band. The cap, an ogee-shaped dome, supports a gilded finial in the form of a pineapple.[108]

The transepts each have a semi-circular entrance portico. Wren was inspired in the design by studying engravings of Pietro da Cortona's Baroque facade of Santa Maria della Pace in Rome.[109][page needed] These projecting arcs echo the shape of the apse at the eastern end of the building.

Walls

The building is of two storeys of ashlar masonry, above a basement, and surrounded by a balustrade above the upper cornice. The balustrade was added, against Wren's wishes, in 1718.[109][page needed] The internal bays are marked externally by paired pilasters with Corinthian capitals at the lower level and Composite at the upper level. Where the building behind is of only one story (at the aisles of both nave and choir) the upper story of the exterior wall is sham.[34] It serves a dual purpose of supporting the buttresses of the vault, and providing a satisfying appearance when viewed rising above buildings of the height of the 17th-century city. This appearance may still be seen from across the River Thames.

Between the pilasters on both levels are windows. Those of the lower storey have semi-circular heads and are surrounded by continuous mouldings of a Roman style, rising to decorative keystones. Beneath each window is a floral swag by Grinling Gibbons, constituting the finest stone carving on the building and some of the greatest architectural sculpture in England. A frieze with similar swags runs in a band below the cornice, tying the arches of the windows and the capitals. The upper windows are of a restrained Classical form, with pediments set on columns, but are blind and contain niches. Beneath these niches, and in the basement level, are small windows with segmental tops, the glazing of which catches the light and visually links them to the large windows of the aisles. The height from ground level to the top of the parapet is approximately 110 feet.

Fencing

The original fencing, designed by Wren, was dismantled in the 1870s. The surveyor for the government of Toronto had it shipped to Toronto, where it has since adorned High Park.[110]

Interior

Internally, St Paul's has a nave and choir in each of its three bays. The entrance from the west portico is through a square domed narthex, flanked by chapels: the Chapel of St Dunstan to the north and the Chapel of the Order of St Michael and St George to the south.[91] The nave is 91 feet (28 m) in height and is separated from the aisles by an arcade of piers with attached Corinthian pilasters rising to an entablature. The bays, and therefore the vault compartments, are rectangular, but Wren roofed these spaces with saucer-shaped domes and surrounded the clerestory windows with lunettes.[91] The vaults of the choir are decorated with mosaics by Sir William Blake Richmond.[91] The dome and the apse of the choir are all approached through wide arches with coffered vaults which contrast with the smooth surface of the domes and punctuate the division between the main spaces. The transepts extend to the north and south of the dome and are called (in this instance) the North Choir and the South Choir.

The choir holds the stalls for the clergy, cathedral officers and the choir, and the organ. These wooden fittings, including the pulpit and Bishop's throne, were designed in Wren's office and built by joiners. The carvings are the work of Grinling Gibbons whom Summerson describes as having "astonishing facility", suggesting that Gibbons aim was to reproduce popular Dutch flower painting in wood.[77] Jean Tijou, a French metalworker, provided various wrought iron and gilt grilles, gates and balustrades of elaborate design, of which many pieces have now been combined into the gates near the sanctuary.[77]

The cathedral is some 574 feet (175 m) in length (including the portico of the Great West Door), of which 223 feet (68 m) is the nave and 167 feet (51 m) is the choir. The width of the nave is 121 feet (37 m) and across the transepts is 246 feet (75 m).[111] The cathedral is slightly shorter but somewhat wider than Old St Paul's.

Dome

The main internal space of the cathedral is that under the central dome which extends the full width of the nave and aisles. The dome is supported on pendentives rising between eight arches spanning the nave, choir, transepts, and aisles. The eight piers that carry them are not evenly spaced. Wren has maintained an appearance of eight equal spans by inserting segmental arches to carry galleries across the ends of the aisles, and has extended the mouldings of the upper arch to appear equal to the wider arches.[93]

Above the keystones of the arches, at 99 feet (30 m) above the floor and 112 feet (34 m) wide, runs a cornice which supports the Whispering Gallery so called because of its acoustic properties: a whisper or low murmur against its wall at any point is audible to a listener with an ear held to the wall at any other point around the gallery. It is reached by 259 steps from ground level.

The dome is raised on a tall drum surrounded by pilasters and pierced with windows in groups of three, separated by eight gilded niches containing statues, and repeating the pattern of the peristyle on the exterior. The dome rises above a gilded cornice at 173 feet (53 m) to a height of 214 feet (65 m). Its painted decoration by Sir James Thornhill shows eight scenes from the life of St Paul set in illusionistic architecture which continues the forms of the eight niches of the drum.[112] At the apex of the dome is an oculus inspired by that of the Pantheon in Rome. Through this hole can be seen the decorated inner surface of the cone which supports the lantern. This upper space is lit by the light wells in the outer dome and openings in the brick cone. Engravings of Thornhill's paintings were published in 1720.[d]

Apse

The eastern apse extends the width of the choir and is the full height of the main arches across choir and nave. It is decorated with mosaics, in keeping with the choir vaults. The original reredos and high altar were destroyed by bombing in 1940. The present high altar and baldacchino are the work of W. Godfrey Allen and Stephen Dykes Bower.[90] The apse was dedicated in 1958 as the American Memorial Chapel.[113] It was paid for entirely by donations from British people.[114] The Roll of Honour contains the names of more than 28,000 Americans who gave their lives while on their way to, or stationed in, the United Kingdom during the Second World War.[115] It is in front of the chapel's altar. The three windows of the apse date from 1960 and depict themes of service and sacrifice, while the insignia around the edges represent the American states and the US armed forces. The limewood panelling incorporates a rocket—a tribute to America's achievements in space.[116]

Artworks, tombs and memorials

St Paul's at the time of its completion, was adorned by sculpture in stone and wood, most notably that of Grinling Gibbons, by the paintings in the dome by Thornhill, and by Jean Tijou's elaborate metalwork. It has been further enhanced by Sir William Richmond's mosaics and the fittings by Dykes Bower and Godfrey Allen.[90] Other artworks in the cathedral include, in the south aisle, William Holman Hunt's copy of his painting The Light of the World, the original of which hangs in Keble College, Oxford. The St. Paul's version was completed with a significant input from Edward Robert Hughes as Hunt was now suffering from glaucoma. In the north choir aisle is a limestone sculpture of the Madonna and Child by Henry Moore, carved in 1943.[90] The crypt contains over 200 memorials and numerous burials. Christopher Wren was the first person to be interred, in 1723. On the wall above his tomb in the crypt is written in Latin: Lector, si monumentum requiris, circumspice ("Reader, if you seek his monument, look around you").

The largest monument in the cathedral is that to the Duke of Wellington by Alfred Stevens. It stands on the north side of the nave and has on top a statue of Wellington astride his horse "Copenhagen". Although the equestrian figure was planned at the outset, objections to the notion of having a horse in the church prevented its installation until 1912. The horse and rider are by John Tweed. The Duke is buried in the crypt.[90] The tomb of Horatio, Lord Nelson is located in the crypt, next to that of Wellington.[117] The marble sarcophagus which holds his remains was made for Cardinal Wolsey but not used as the cardinal had fallen from favour.[118][90] At the eastern end of the crypt is the Chapel of the Order of the British Empire, instigated in 1917, and designed by John Seely, Lord Mottistone.[90] There are many other memorials commemorating the British military, including several lists of servicemen who died in action, the most recent being the Gulf War.

Also remembered are Florence Nightingale, J. M. W. Turner, Arthur Sullivan, Hubert Parry, Samuel Johnson, Lawrence of Arabia, William Blake,William Jones and Sir Alexander Fleming as well as clergy and residents of the local parish. There are lists of the Bishops and cathedral Deans for the last thousand years. One of the most remarkable sculptures is that of the Dean and poet, John Donne. Before his death, Donne posed for his own memorial statue and was depicted by Nicholas Stone as wrapped in a burial shroud, and standing on a funeral urn. The sculpture, carved around 1630, is the only one to have survived the conflagration of 1666 intact.[90] The treasury is also in the crypt but the cathedral has very few treasures as many have been lost, and on 22 December 1810 a major robbery took almost all of the remaining precious artefacts.[119]

The funerals of many notable figures have been held in the cathedral, including those of Lord Nelson, the Duke of Wellington, Winston Churchill, George Mallory and Margaret Thatcher.[120]

Clock and bells

A clock was installed in the south-west tower by Langley Bradley in 1709 but was worn out by the end of the 19th century.[121] The present mechanism was built in 1893 by Smith of Derby incorporating a design of escapement by Edmund Denison Beckett similar to that used by Edward Dent on Big Ben's mechanism in 1895. The clock mechanism is 19 feet (5.8 m) long and is the most recent of the clocks introduced to St Paul's Cathedral over the centuries. Since 1969 the clock has been electrically wound with equipment designed and installed by Smith of Derby, relieving the clock custodian from the work of cranking up the heavy drive weights.

The south-west tower also contains four bells, of which Great Paul, cast in 1881 by J. W. Taylor of Taylor's bell foundry of Loughborough, at 16+1⁄2 long tons (16,800 kg) was the largest bell in the British Isles until the casting of the Olympic Bell for the 2012 London Olympics.[122] Although the bell is traditionally sounded at 1 pm each day, Great Paul had not been rung for several years because of a broken chiming mechanism.[123] In the 1970s, the bolt that held the clapper in place inside the bell had broken. The clapper and its suspension, which together weigh a tonne, had fallen through the clock mechanism below, causing £30,000 worth of damage. In about 1989, the clapper had finally and irrevocably fractured.[124] On 31 July 2021, during the London Festival of the Bells, Great Paul rang for the first time in two decades, being hand swung by the bell ringers. The clock bells included Great Tom, which was moved from St Stephen's Chapel at the Palace of Westminster and has been recast several times, the last time by Richard Phelps. It chimes the hour and is traditionally tolled on occasions of a death in the royal family, the Bishop of London, or the Lord Mayor of London, although an exception was made at the death of the US president James Garfield.[125] It was last tolled for the death of Queen Elizabeth II in 2022, ringing once every minute along with other bells across the country in honor of the 96 years of her life.[126] In 1717, Richard Phelps cast two more bells that were added as "quarter jacks" that ring on the quarter hour. Still in use today, the first weighs 13 long cwt (1,500 lb; 660 kg), is 41 inches (100 cm) in diameter and is tuned to A♭; the second weighs 35 long cwt (3,900 lb; 1,800 kg) and is 58 inches (150 cm) in diameter and is tuned to E♭.

The north-west tower contains a ring of 12 bells by John Taylor & Co of Loughborough hung for change ringing. In January 2018 the bells were removed for refurbishment and were rehung in September that year, being rung again for the first time on All Saints' Day. The original service or "Communion" bell dating from 1700 and known as "the Banger" is rung before 8 am services.[122]

| Bell | Weight | Nominal Hz |

Note | Diameter | Date cast |

Founder | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (long measure) | (lb) | (kg) | (in) | (cm) | |||||

| 1 | 8 long cwt 1 qr 4 lb | 928 | 421 | 1,461 | F | 30.88 | 78.4 | 1878 | John Taylor & Co |

| 2 | 9 long cwt 0 qr 20 lb | 1,028 | 466 | 1,270 | E♭ | 32.50 | 82.6 | 1878 | John Taylor & Co |

| 3 | 9 long cwt 3 qr 12 lb | 1,104 | 501 | 1,199 | D | 34.00 | 86.4 | 1878 | John Taylor & Co |

| 4 | 11 long cwt 2 qr 22 lb | 1,310 | 594 | 1,063 | C | 36.38 | 92.4 | 1878 | John Taylor & Co |

| 5 | 13 long cwt 1 qr 0 lb | 1,484 | 673 | 954 | B♭ | 38.63 | 98.1 | 1878 | John Taylor & Co |

| 6 | 13 long cwt 2 qr 14 lb | 1,526 | 692 | 884 | A | 39.63 | 100.7 | 1878 | John Taylor & Co |

| 7 | 16 long cwt 1 qr 18 lb | 1,838 | 834 | 784 | G | 43.75 | 111.1 | 1878 | John Taylor & Co |

| 8 | 21 long cwt 3 qr 18 lb | 2,454 | 1,113 | 705 | F | 47.63 | 121.0 | 1878 | John Taylor & Co |

| 9 | 27 long cwt 1 qr 22 lb | 3,074 | 1,394 | 636 | E♭ | 52.50 | 133.4 | 1878 | John Taylor & Co |

| 10 | 29 long cwt 3 qr 21 lb | 3,353 | 1,521 | 592 | D | 55.25 | 140.3 | 1878 | John Taylor & Co |

| 11 | 43 long cwt 2 qr 0 lb | 4,872 | 2,210 | 525 | C | 61.25 | 155.6 | 1878 | John Taylor & Co |

| 12 | 61 long cwt 2 qr 12 lb | 6,900 | 3,130 | 468 | B♭ | 69.00 | 175.3 | 1878 | John Taylor & Co |

| Clock | 12 long cwt 2 qr 9 lb | 1,409 | 639 | 853 | A♭ | 1707 | Richard Phelps | ||

| Clock | 24 long cwt 2 qr 26 lb | 2,770 | 1,256 | 622 | E♭ | 1707 | Richard Phelps | ||

| Clock | 102 long cwt 1 qr 22 lb | 11,474 | 5,205 | 425 | A♭ | 82.88 | 210.5 | 1716 | Richard Phelps |

| Bourdon | 334 long cwt 2 qr 19 lb | 37,483 | 17,002 | 317 | E♭ | 114.75 | 291.5 | 1881 | John Taylor & Co |

| Communion | 18 long cwt 2 qr 26 lb | 2,098 | 952 | 620 | E♭ | 49.50 | 125.7 | 1700 | Philip Wightman |

Education, tourism and the arts

Interpretation Project

The Interpretation Project is a long-term project concerned with bringing St Paul's to life for all its visitors. In 2010, the Dean and Chapter of St Paul's opened St Paul's Oculus, a 270° film experience that brings 1400 years of history to life.[127] Located in the former Treasury in the crypt, the film takes visitors on a journey through the history and daily life of St Paul's Cathedral. Oculus was funded by American Express Company in partnership with the World Monuments Fund, J. P. Morgan, the Garfield Weston Trust for St Paul's Cathedral, the City of London Endowment Trust and AIG.

In 2010, new touchscreen multimedia guides were also launched. These guides are included in the price of admission. Visitors can discover the cathedral's history, architecture and daily life of a busy working church with these new multimedia guides. They are available in 12 different languages: English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Polish, Russian, Mandarin, Japanese, Korean and British Sign Language (BSL). The guides have fly-through videos of the dome galleries and zoomable close-ups of the ceiling mosaics, painting and photography. Interviews and commentary from experts include the Dean of St Paul's, conservation team and the Director of Music. Archive film footage includes major services and events from the cathedral's history.

Charges for sightseers

St Paul's charges for the admission of those people who are sightseers, rather than worshippers; the charge is £23 (£20.50 when purchased online).[128] Outside service times, people seeking a quiet place to pray or worship are admitted to St Dunstan's Chapel free of charge. On Sundays people are admitted only for services and concerts and there is no sightseeing. The charge to sightseers is made because St Paul's receives little regular or significant funding from the Crown, the Church of England or the state and relies on the income generated by tourism to allow the building to continue to function as a centre for Christian worship, as well as to cover general maintenance and repair work.[129][130]

St Paul's Cathedral Arts Project

The St Paul's Cathedral Arts Project explores art and faith. Projects have included installations by Gerry Judah, Antony Gormley, Rebecca Horn, Yoko Ono and Martin Firrell.

In 2014, St Paul's commissioned Gerry Judah to create an artwork in the nave to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the First World War. Two spectacular sculptures consisting of three-dimensional white cruciforms reflect the meticulously maintained war graves of northern France and further afield. Each sculpture is also embellished with miniaturised destroyed residential blocks depicting war zones in the Middle East—Syria, Baghdad, Afghanistan—thus connecting 100 years of warfare.[131]

Bill Viola has created two altarpieces for permanent display in St Paul's Cathedral. The project commenced production in mid-2009. Following the extensive programme of cleaning and repair of the interior of St Paul's, completed in 2005, Viola was commissioned to create two altarpieces on the themes of Mary and Martyrs. These two multi-screen video installations are permanently located at the end of the Quire aisles, flanking the High Altar of the cathedral and the American Memorial Chapel. Each work employs an arrangement of multiple plasma screen panels configured in a manner similar to historic altarpieces.

In summer 2010, St Paul's chose two new works by the British artist Mark Alexander to be hung either side of the nave. Both entitled Red Mannheim, Alexander's large red silkscreens are inspired by the Mannheim Cathedral altarpiece (1739–41), which was damaged by bombing in the Second World War. The original sculpture depicts Christ on the cross, surrounded by a familiar retinue of mourners. Rendered in splendid giltwood, with Christ's wracked body sculpted in relief, and the flourishes of flora and incandescent rays from heaven, this masterpiece of the German Rococo is an object of ravishing beauty and intense piety.

In March 2010, Flare II, a sculpture by Antony Gormley, was installed in the Geometric Staircase.[132]

In 2007, the Dean and Chapter commissioned Martin Firrell to create a major public artwork to mark the 300th anniversary of the topping-out of Wren's building. The Question Mark Inside consisted of digital text projections to the cathedral dome, West Front and inside onto the Whispering Gallery. The text was based on blog contributions by the general public as well as interviews conducted by the artist and on the artist's own views. The project presented a stream of possible answers to the question: "What makes life meaningful and purposeful, and what does St Paul's mean in that contemporary context?" The Question Mark Inside opened on 8 November 2008 and ran for eight nights.

Depictions of St Paul's

St Paul's Cathedral has been depicted many times in paintings, prints and drawings. Among the well-known artists to have painted it are Canaletto, Turner, Daubigny, Pissarro, Signac, Derain, and Lloyd Rees.

- Paintings and engravings of St Paul's

-

Canaletto: The River Thames with St. Paul's Cathedral on Lord Mayor's Day (1746; Lobkowicz Collections, Prague)

-

19th-century coloured engraving from the south-west by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd

-

Romantic 19th-century engraving of St Paul's in the evening after rain by Edward Angelo Goodall

-

Oil painting, John O'Connor, Evening on Ludgate Hill (1887) St Paul's looms beyond St Martin's

-

St Paul's from Richmond House by the Venetian painter Canaletto (1747)

-

St Paul's viewed from a loggia, a capriccio (c. 1748) by Antonio Joli who also worked in Venice

-

An Impressionist view of St Paul's from the River by Ernest Dade (before 1936)

-

St Paul's from Bankside, a watercolour by Frederick E. J. Goff (before 1931)

Photography and film

St Paul's Cathedral has been the subject of many photographs, most notably the iconic image of the dome surrounded by smoke during the Blitz.(see above) It has also been used in films and TV programmes (including Thames Television's most recognized ident), either as the focus of the film, as in the episode of Climbing Great Buildings; as a feature of the film, as in Mary Poppins; or as an incidental location such as Wren's Geometric Staircase in the south-west tower which has appeared in several films including Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban.

Films in which St Paul's has been depicted include:

- St. Paul's Cathedral (1942), a wartime documentary film for the British Council, the final part of which shows bomb damage in and around St Paul's.[133]

- Lawrence of Arabia (1962) shows the exterior of the building and the bust of T.E. Lawrence.

- Mary Poppins (1964) shows the steps and west front of the cathedral, the main setting for the song '"Feed the Birds'".

- St Paul's Cathedral has appeared as a filming location twice in Doctor Who, in the 1968 serial The Invasion, and in the 2014 two-part story "Dark Water"/"Death in Heaven". In both, the Cybermen are shown descending steps outside the cathedral.

- St Paul's is seen briefly in the Goodies episode "Kitten Kong" (1971). During his rampage through London, Twinkle damages London landmarks, including St Paul's Cathedral, the dome of which is knocked off.

- In the BBC educational programme "A Guide to Armageddon" (1982), a 1-megaton nuclear weapon is detonated over London, with St Paul's used as ground zero.

- Lifeforce (1985) - the cathedral's interior is the setting for the climax of the film.

- The Madness of King George (1994) shows the Geometric Staircase in the South West Bell Tower.

- Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004) shows the Geometric Staircase in the south west bell tower, representing the staircase towards the Divination classroom.

- Star Trek Into Darkness (2013) depicts St Paul's in 23rd century London along with other notable modern-day London buildings.[e]

- St Paul's is the only building of ancient London that survived the "Sixty Minute War" in the movie Mortal Engines (2018) and the books it is based on.

See also

- Cyril Raikes (fire watching on the dome of St Paul's Cathedral in the Second World War)

- Category:Burials at St Paul's Cathedral

- List of cathedrals in the United Kingdom

- List of churches and cathedrals of London

- Magnificat and Nunc dimittis for St Paul's Cathedral

- Paternoster Square

- Tall buildings in London

- History of early modern period domes

- List of tallest domes

- List of tallest structures built before the 20th century

References

Notes

- ^ "Nomina Episcoporum, cum Clericis Suis, Quinam, et ex Quibus Provinciis, ad Arelatensem Synodum Convenerint" ["The Names of the Bishops with Their Clerics who Came Together at the Synod of Arles and from which Province They Came"](from Labbé & Cossart 1671, col. 1429 included in Thackery 1843, pp. 272 ff.).

- ^ Not to be confused with an identically named film director.

- ^ The largest is at Liverpool Cathedral, followed by the Royal Albert Hall, the Royal Festival Hall and St George's Hall.

- ^ Entered in the Entry Book at Stationers' Hall on 7 May 1720 by Thornhill. The Bodleian Library's deposit copy survives (Arch.Antiq.A.III.23).

- ^ Advertising poster for Star Trek Into Darkness (2013) — bottom right, the dome is visible to the left of and behind 30 St Mary Axe (the Gherkin)

Citations

- ^ a b c Ward Lock & Co., Limited (1914). A Pictorial and Descriptive Guide to London and Its Environs (Thirty-Eighth Edition—Revised ed.). London: Ward Lock & Co., Limited. p. 209. OCLC 437623827. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ Hibbert et al. 2011, p. 778.

- ^ Gardner, Kleiner & Mamiya 2004, p. 760.

- ^ The London Standard 10/6/1873 page 6

- ^ Pierce 2004.

- ^ "Sightseeing, Times & Prices". Stpauls.co.uk. The Chapter of St Paul's Cathedral. Archived from the original on 29 January 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ "St. Paul's Cathedral". Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ Denison 1995.

- ^ Sankey 1998, pp. 78–82.

- ^ Camden 1607, pp. 306–307.

- ^ Clark 1996, pp. 1–9.

- ^ Mann, J. C. (December 1961). "The Administration of Roman Britain". Antiquity. 35 (140): 316–20. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00106465. S2CID 163142469. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ Bede 1910, pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b "Secular canons: Cathedral of St. Paul | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ^ Garmonsway 1953, p. 218.

- ^ "St Paul's: To the Great Fire | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of OLD ST. PAUL'S CATHEDRAL By WILLIAM BENHAM, D.D., F.S.A." www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ Sharpe, Reginald R. (Reginald Robinson) (13 November 2006). London and the Kingdom - Volume 1A History Derived Mainly from the Archives at Guildhall in the Custody of the Corporation of the City of London.

- ^ a b Lehmberg 2014, p. 114.

- ^ Dickens, A. G. (1 January 1989). The English Reformation (2nd ed.). Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-02868-2.

- ^ "The Architectural Setting of Anglican Worship by Addleshaw G W O Etchells Frederick - AbeBooks". www.abebooks.co.uk. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "Tudor Constitutional Documents 1485 1603 by J R Tanner - AbeBooks". www.abebooks.co.uk. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "St.Paul's Cathedral during the Reformation | The History of London". 25 January 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Morrissey 2011, p. 3.

- ^ Dugdale 1658, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Kelly 2004.

- ^ "The Survey of Building Sites in London after the Great Fire of 1666" Mills, P/ Oliver, J Vol I p59: Guildhall Library MS. 84 reproduced in facsimile, London, London Topographical Society, 1946

- ^ Campbell 2007, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Hart 2002.

- ^ Campbell 2007, p. 10.

- ^ a b Lang 1956, pp. 47–63.

- ^ Summerson 1983, p. 204.

- ^ Summerson 1983, p. 223.

- ^ a b c d Fletcher 1962, p. 913.

- ^ Keene, Burn & Saint 2004, p. 219.

- ^ Campbell 2007, p. 161.

- ^ Campbell 2007, p. 69.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Wright 1693.

- ^ Tinniswood 2001, p. 315.

- ^ a b c "Suffragettes, violence and militancy". British Library. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ Webb, Simon (2014). The Suffragette Bombers: Britain's Forgotten Terrorists. Pen and Sword. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-78340-064-5. Archived from the original on 29 July 2023. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ Bearman, C. J. (2005). "An Examination of Suffragette Violence". The English Historical Review. 120 (486): 378. doi:10.1093/ehr/cei119. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 3490924. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Jones, Ian (2016). London: Bombed Blitzed and Blown Up: The British Capital Under Attack Since 1867. Frontline Books. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-1-4738-7901-0. Archived from the original on 29 July 2023. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ a b Jardine 2006.

- ^ "St. Paul's Cathedral in London Hit by Bomb". The Evening Independent. 19 April 1941. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ The Chapter of St Paul's Cathedral 2014.

- ^ Geffen 2014.

- ^ 1942531 Sapper George Cameron Wylie. Bomb Disposal: Royal Engineers—George Cross, 33 Engineer regiment, Royal Engineers website, archived from the original on 30 January 2008, retrieved 28 January 2008

- ^ "No. 34956". The London Gazette (Supplement). 27 September 1940. pp. 5767–5768.

- ^ Miller, Julie. "Inside Princess Diana's Royal Wedding Fairy Tale". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "St Paul's Cathedral completes £40m restoration project". BBC News. 15 June 2011. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ Walker & Butt 2011.

- ^ Ward 2011.

- ^ Walker 2011.

- ^ St Paul's protest: Occupy London camp evicted, BBC, 28 February 2012, archived from the original on 25 June 2018, retrieved 21 July 2018

- ^ "Woman jailed for life following triple-bomb plot conviction". Counter Terrorism Policing. 3 July 2020. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ Burns 2004, p. 381.

- ^ "Worship – Choral Evensong". St Paul's Cathedral. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ^ The Chapter of St Paul's Cathedral (2016), "Home — St Paul's Cathedral", Stpauls.co.uk, archived from the original on 4 February 2016, retrieved 18 February 2016

- ^ The Chapter of St Paul's Cathedral 2016c.

- ^ The Chapter of St Paul's Cathedral 2016d.

- ^ "Press release", Stpauls.co.uk, archived from the original on 28 September 2022, retrieved 28 September 2022

- ^ a b "Service Schedule, May 2019" (PDF). 29 May 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ "Service Schedule, February 2019" (PDF). 29 May 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Gillian Bowen and the Reverend Neil Evans appointed to Cathedral Chapter". St Paul's Cathedral. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ "Appointment of The Venerable Sheila Watson as Additional Chapter Member and Canon Non-Residentiary of St Paul's Cathedral – St Paul's Cathedral". Stpauls.co.uk. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ "Gov.uk" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ "Sheila Nicoll OBE to become Lay Canon at St Paul's – St Paul's Cathedral". Stpauls.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Cathedral Choirs & Musicians". Stpauls.co.uk. The Chapter of St Paul's Cathedral. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ "Appointment of new Director of Music". St Paul's Cathedral website, news section. Dean and Chapter of St Paul's. 21 May 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 23 May 2007.

- ^ Lang 1956, p. 171.

- ^ "The Organs & Bells – St Paul's Cathedral". Stpauls.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Sayers, M D. "St Paul's Cathedral, St Paul's Churchyard C00925". The National Pipe Organ Register. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ "The world's largest and most famous organs". Die Orgelseite. Archived from the original on 13 August 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "St. Paul's". stpauls.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Summerson 1983, pp. 238–240.

- ^ Sayers, M D. "St Paul's Cathedral, St Paul's Churchyard A00752". The National Pipe Organ Register. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ Rudgard, Olivia (28 February 2017). "St Paul's Cathedral appoints first female chorister in 1,000-year history". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ "St Paul's Cathedral admits first woman to choir". BBC News. 28 February 2017. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ de la Ware, Tess (1 March 2017). "St Paul's appoints first full-time female chorister in 1,000-year history". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ "St Paul's Cathedral to admit girls to choir for first time in 900 years". The Guardian. 5 May 2022. Archived from the original on 5 May 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ Campbell 2007, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Tabor 1919, p. 108.

- ^ a b c Downes 1987, pp. 11–34.

- ^ Saunders 2001, p. 60.

- ^ a b Hart 1995, pp. 17–23.

- ^ Barker & Hyde 1982.

- ^ Campbell 2007, pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Harris 1988, pp. 214–15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Fletcher 1962, p. 906.

- ^ Campbell 2007, p. 56–59.

- ^ a b c Summerson 1983, p. 228.

- ^ Campbell 2007, p. 137.

- ^ Campbell 2007, pp. 105–114.

- ^ Tinniswood 2010, p. 203.

- ^ Lang 1956, p. 209.

- ^ Lang 1956, pp. 252, 230.

- ^ St Paul's website, Miscellaneous Drawings Archived 20 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ St Paul's Cathedral website, Climb the Dome Archived 21 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Figure of Christ – St. Paul's Cathedral • Gino Masero". Gino Masero. 21 October 2017. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Gardner, Kleiner & Mamiya 2004.

- ^ Fletcher 1962, p. 912.

- ^ Gardner, Kleiner & Mamiya 2004, pp. 604–05.

- ^ a b Pevsner 1964, pp. 324–26.

- ^ a b Summerson 1983, p. 236.

- ^ a b Summerson 1983, p. 234.

- ^ "6. The western towers, c.1685–1710 – St Paul's Cathedral". Stpauls.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ a b Leapman 1995.

- ^ "The Story of a Fence". Archived from the original on 10 February 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.