Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science: Difference between revisions

| Line 899: | Line 899: | ||

How long (typically) after a minor cut (such as a paper cut) does the skin become impermeable to viruses? Thanks. |

How long (typically) after a minor cut (such as a paper cut) does the skin become impermeable to viruses? Thanks. |

||

After a good scab (don't pick it) is developed. If no viruses have gotten in, you should be safe. --[[User:Chemicalinterest|Chemicalinterest]] ([[User talk:Chemicalinterest|talk]]) 19:49, 29 April 2010 (UTC) |

|||

Revision as of 19:49, 29 April 2010

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

April 25

relation between the expansion of orbits and of the universe

It seems quite reasonable that because orbits like the Moon can expand that such expansion could the explanation for the expansion of the Universe since orbits seem to be a Universal phenomenon, pun intended. Indulging this line of thought consider that somewhere then there must be a center about which everything orbits which probably contains the center of mass as well. What science denies that such a center exists and that orbit is only a local phenomenon and not one that is totally universal? Plain vanilla with chocolate chips (talk) 05:28, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- I'm sorry - but what you are suggesting makes zero sense.

- Why would you think that the gradual expansion of the moon's orbit would have anything to do with the expansion of the universe? The gradual increase in the moons' orbit is caused by gradual consumption of the moons' kinetic energy as it raises tides - there is no such mechanism happening in the universe as a whole. You can't just say "Thing A is expanding because of reason B, hence the expansion of thing C must also be because of reason B."

- So I'm not going to "indulge this line of thought" - because it's 100% wrong. There doesn't have to be a "center" about which everything orbits or a "center of mass" because this whole orbital theory of yours is not remotely true:

- We know the universe is expanding because we see redshift in light from distant galaxies.

- Einstein field equations of general relativity explain why this is happening in mathematically specific form.

- General relativity is an exceedingly well tried and tested theory.

- Furthermore, many experiments - including the decisive observations of the cosmic background radiation) prove conclusively that space has been expanding ever since the big bang.

- To be credible, your "explanation" would have to explain why Einsteins' field equations are somehow incorrect and explain why we observe all of the other effects of general relativity and somehow find another explanation for all of those experiments which you are (in effect) saying must be false.

- Science does not allow you to just come up with a mental model that (to you) explains something you don't understand. You also have to tie that in to all of the other aspects of physics that relate to that idea. You won't be able to do that - which is why we know you're wrong.

- I suggest you carefully read Metric expansion of space which explains what we know - how we know it - and (crucially) which experiments have been done to show that these theories correctly explain our observations...but "orbits" have nothing whatever to do with that.

- SteveBaker (talk) 06:48, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

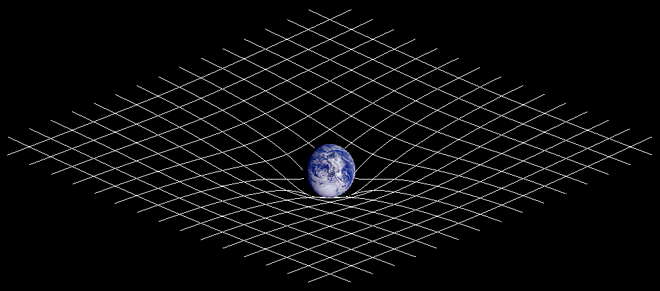

- Gravity is often depicted as an indentation on a grid. How do you express the moon's expanding orbit on this grid? Does the grid become flatter and flatter in the area of the moon's orbit and it so what happens if it becomes entirely flat? Same question for the Universe assuming there is a center around which everything else orbits? Would not this flatter and flatter grid represent the expansion of the Universe as the area of orbit furthest from the center just like we see in galaxies? Plain vanilla with chocolate chips (talk) 09:06, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- The indentation stays the same, since the mass of the Earth doesn't change. Imagine you have a big bowl and roll a marble in it - depending on how fast you roll the marble, it will go around the bowl at different heights (it will gradually move lower due to friction, but that's a limitation of the analogy - there is no significant friction for the moon). The tidal interaction between the Earth and Moon just changes the height of the orbit since it changes the speed of the moon. --Tango (talk) 13:49, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- The moon doesn't move outwards due to consumption of energy, really, (that doesn't make much sense - energy is conserved, so it is just transferred not consumed). It is due to the lag between the moon's current, always moving, position and the tidal bulges it causes (the bulges take time to move, so lag behind the moon). The gravitational interaction between the moon and those bulges results in a transfer of angular momentum between the Earth and moon. --Tango (talk) 13:49, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Indeed, energy never "goes away" it's just converted to another form. However, we don't usually go around talking about how the batteries in our flashlights transferred all of their energy to this and that form - we say that it ran out of energy and those who care about those kinds of things understand what we're talking about. So, sure, the kinetic energy of the moon is converted into heat and into making the earth rotate a bit faster...both a consequence of tidal effects. But the bottom line is that the moon loses kinetic energy due to tidal effects and that's causing it's orbit to slowly get bigger. SteveBaker (talk) 18:11, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Gravity is often depicted as an indentation on a grid. How do you express the moon's expanding orbit on this grid? Does the grid become flatter and flatter in the area of the moon's orbit and it so what happens if it becomes entirely flat? Same question for the Universe assuming there is a center around which everything else orbits? Would not this flatter and flatter grid represent the expansion of the Universe as the area of orbit furthest from the center just like we see in galaxies? Plain vanilla with chocolate chips (talk) 09:06, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

I would be inclined to agree partially with the original post in that the earth revolves around the sun, the solar system aroung the galaxy and the galaxies around some greater point, what is that point? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 62.172.58.82 (talk) 09:39, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- There is no evidence that the galaxies are rotating around "some greater point". They rotate about their own centers - but precisely because there is no "center" to the universe - there is no larger scale rotation going on. That's yet another reason why this idea is a non-starter. It's tempting to think that because moons orbit planets and planets orbit stars and stars orbit galaxies, that there should be some higher order rotation - but there isn't...so right there (and in a dozen other ways) this theory falls to the ground. It is as I said before - you can't understand the universe by just thinking stuff up in your head - your hypotheses have to fit in with all the other bits of known science - and this hypothesis of yours doesn't do that...not even close! In your mind, this idea "fixes" something you evidently don't understand about the metric expansion of space - but it "un-fixes" a million other things we know with great certainty! SteveBaker (talk) 18:11, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Some of the larger galaxies do have smaller satellite galaxies orbiting them. The OP might also be interested in the Local Group article, which describes what the Milky Way, and the Andromeda Galaxy etc are doing, the Virgo Cluster and Virgo Supercluster articles, which describes how they are bound to other groups, and the large-scale structure of the cosmos article which describes the situation in general. CS Miller (talk) 22:14, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- See the true expansion of gravity Plain vanilla with chocolate chips (talk) 09:50, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- We can measure the distance to the moon and theorise about what ought to happen to that distance. There is no significant discrepancy between the measurements and the predictions, so we don't need to try and come up with another explanation. --Tango (talk) 13:49, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- I have not read Ismail Kaddah's article at Academia.Wikia. All I have seen is the diagram he uploaded which shows a theoretical (IMHO) center of the Universe around which things that orbit each other orbit so you will have to ask him. Plain vanilla with chocolate chips (talk) 15:58, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Academia.Wikia is not a peer reviewed journal (their "peer review" process doesn't seem to include any verification of credentials, so cannot be consider to be peer review), so you shouldn't trust any theories posted there. If the theory was likely to have any validity, it would have been published in a real journal. --Tango (talk) 17:54, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- I have not read Ismail Kaddah's article at Academia.Wikia. All I have seen is the diagram he uploaded which shows a theoretical (IMHO) center of the Universe around which things that orbit each other orbit so you will have to ask him. Plain vanilla with chocolate chips (talk) 15:58, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- That wikia piece is complete incoherent gibberish. You should ignore it. Wikia is a terrible place to go to find truth and fact. Wikia's policies allow anyone to write anything. I could write an article saying that electricity is carried around by tiny little green men in recycled WalMart shopping bags - and it would be accepted there. Without any kind of control of reliability (such as we have here on Wikipedia) - you simply cannot trust anything that's written there. It truly is a waste of disk space. SteveBaker (talk) 18:11, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- If an object is orbiting below the synchronous rotation orbit height, then it will slow down, and reduce its orbit height until it either enters the atmosphere or collides with the surface, see tidal acceleration. CS Miller (talk) 22:25, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

Someone mentioned that part of the energy drained from the moon is transfered to earth's rotation, speeding it up. That's not correct. The earth is actually slowing down its rotation. Dauto (talk) 15:34, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

Physics-Question regarding Vacuum

What happens when a fan is switched on inside a perfect vacuum? Imagine a glass room that is completely sealed. Perfect vacuum is maintained. A battery is kept in and a fan be connected to it. If we switch it on with any remote controller, will it run or what happens? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Srvnbv (talk • contribs) 06:17, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- It is very easy to answer this question without having to achieve a vacuum. Simply remove the fan blades and run the electric motor. Without a load on the motor it runs at its zero-load speed. Contrary to what you might imagine, the unloaded electric motor doesn't keep accelerating forever. Electric motors have an equilibrium speed determined by their power source and their system of magnetic field and wiring. With no load, the motor will run at its no-load speed. When the motor is loaded, such as with a fan, it runs at a speed somewhat slower than its zero-load speed. Have a look at Synchronous motor. Dolphin (t) 06:25, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- If the motor has internal friction (as all "real" motors do) - then the fan would run quite a bit faster than it would in air - but the system would quickly reach an equilibrium at which point all of the electrical energy coming from the battery would go into overcoming friction. If you imagine a totally frictionless motor - then it would either continue to speed up faster and faster so long as you kept a charged battery connected to it...or it would cease to draw power from the battery when it reached a certain maximum speed. (Which of these things would happen depends on the design of the motor). SteveBaker (talk) 07:07, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- If we're talking about the portable battery operated fans that we use in our motor-homes, hobby shacks, etc. then it would be a cheap-an'-cheerful brushed DC motor . It would speed up a bit with no load but the back Electromotive force being generated would limit its maximum speed . As the article Brushed DC electric motor explains As As an unloaded DC motor spins, it generates a backwards-flowing electromotive force that resists the current being applied to the motor. The current through the motor drops as the rotational speed increases, and a free-spinning motor has very little current. It is only when a load is applied to the motor that slows the rotor that the current draw through the motor increases. So it would run a bit cooler without load, but without some gas present to aid cooling, it would get hotter and hotter. The cheap-an'-cheerful bearings are unlikely to be lubricated with vacuum grease (nor employ dry running ceramic ball bearings) so there goes your hope of maintaining a perfect vacuum. The insulating vanish on the windings would start out-gassing with the rising heat too. The plastics would also 'out-gas' and you'd lose perfect vacuum that way too. You would lose vacuum faster than you could pump out the vapours and thus the motor would then start to lose heat. A quick consideration of the tribological effects of the vacuum and one has to ask what happens as the lubrication evaporates and the bearings dry. Without their lubrication (and protective oxide layers) the metal will (or may, depending on different things) start to form many temporary 'micro-welds' creating heat and the micro-weld particles and rough surfaces produced from this, increasing the friction. The carbon brushes will also wear out and fail in a very much sorter time when run in a vacuum. Another phenomena you might witness as the commutator spins: that without the presence of air to quench all those little sparks, a low voltage Corona discharge may lead to speed loss due to shorting. Putting all that together: The fanless fan, would most likely seize first, and if there is no current trip, the windings will (in places) short and glow about 'cherry red' (at which point it will be radiating heat more efficiently), until the conductors sublimate into space/vacuum and an open circuit condition is achieved. If NASA could ignore these problems, it could buy most of its stuff from RadioShack and space exploration would be a lot cheaper. --Aspro (talk) 09:38, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

power in watts used when sending a phone text message.

any estimates for this ...sending a text phone message , a tweet, a facbook update? I know the phone powers up as you can hear interference on electrical equipment. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 89.241.1.51 (talk) 11:45, 25 April 2010

- According to Mobile phone radiation and health, a GSM phone emits a peak power of 2W, other technologies rather less. The actual power radiated will not depend on the content, but on how accessible the base station is. --ColinFine (talk) 14:15, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- The watts used depends on how far the base station is. But a text message transmits for a very short time - just a chirp, rather than the continuous transmission with voice. Your phone makes these "chirps" anyway, even without a text message, all the time, so that the base station can keep track of it. Ariel. (talk) 08:14, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- I think that the maximum rating set by the FCC and Canada authorities is 1.6W/kg. Normally a phone is less. I don't believe that the radiation emitted by a phone has any effects on the body. --Cheminterest (talk) 20:55, 27 April 2010 (UTC)

What is suprastine

I'm assuming that this was intended to be a separate question, and have made it into a heading. --ColinFine (talk) 14:15, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

I don't know. Wikipedia and Google both say "Do you mean suprastin?". In WP that redirects to Chloropyramine. --ColinFine (talk) 14:15, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

Riding a bicycle - reducing energy used per mile

Air resitance increases with the square of speed, but what about rolling resistance? I recall hearing that it decreases with speed, is that correct? My own experience of going on long rides using a conventional bike is that it feels like you are using less energy per mile the faster you go. Is that impression correct please? Is there an ideal speed that balances wind resistance and rolling resitance?

I have always cycled in old jeans and so on. Would I notice any difference in air resistance if I wore the lycra fetish clothes that racing cyclists wear? I probably only cycle at about 10 miles per hour, although I may get fit enough and practiced enough to go faster.

I like going for long rides of say 40 miles through the english countryside. I am not particularly interested in speed, but am very interested in what is best regarding doing long rides without getting very tired on the way home. Thanks 89.243.216.99 (talk) 13:36, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Hi 89.243, I can't answer your question off the top of my head, but Bicycling Science by D G Wilson is excellent. I think the gist of it is that the most cost-effective way of reducing rolling resistance is making sure your tires are pumped up (and not using knobbly MTB tyres if you're on the road). Bicycling Science also has extensive chapters on energy consumption and air resistance which will be of use to you. Some informed speculation for you: unless you're wearing MC Hammer-style trousers, I don't think switching to lycra will save you much energy: Richard's Bicycle Book (in one of its incarnations at least) says that shaving ones legs will only take about 0.125 seconds off someone's time for a 40km time trial, or there abouts. I would be surprised if the advantage is much more pronounced between jeans and tights. Most people I know find that shorts surpass jeans when it comes to comfort over distance, as there's less to flap about, it's cooler, there's less chafing, your knees are more free to move and if you get wet you don't get stuck in cardboard-like soggy denim! Happy cycling. Brammers (talk) 15:55, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks, I read parts of the book, but could not see anything about rolling resistance and speed unfortunately. 89.243.216.99 (talk) 17:50, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Had a rummage for you (would have done it sooner but I left my copy at home and I'm at uni now). This chart shows that although rolling resistance is velocity-dependent, the difference in rolling resistance at two (fairly extreme) speeds decreases sharply with tyre pressure. The data is for car tyres, but I think that since bicycle tyres are pumped to about 5 bar (70 psi) and travel at much slower speeds, the change in rolling resistance with speed would be negligible. Brammers (talk) 10:33, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks, I read parts of the book, but could not see anything about rolling resistance and speed unfortunately. 89.243.216.99 (talk) 17:50, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- One correction - the horsepower required to overcome air resistance increases as the CUBE of the speed - not the square. The power to overcome rolling resistance increases roughly linearly with speed. So from a pure mechanical energy consumption perspective, slow is without doubt better. However, this is a human-powered system - and humans are not simple machines. It takes a certain amount of energy to pump your legs, breathe, maintain body temperature and all sorts of other things that may be completely independent of speed. In that case, getting there quickly has benefit to you - even if you have to apply more power to the bicycle to do it. The trouble is that doing analysis with a human in the loop takes this out of the realm of simple mechanics and into complicated biochemistry stuff...which is the point where I have to shrug and say "I dunno". SteveBaker (talk) 17:46, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Agreed. But the secret to avoid getting "very tired" on the way home is to eat some carbs while on the bike (or on a break - I'd rather have a nice plate of pasta than the chemical paste used by racers). Once you've run down your glucose levels, the body goes into energy saving mode, and every km hurts. I once rode down from Trento to Lake Garda with a nice backwind, and found out to late that all shops and restaurants were closed. The way back was somewhat less than pleasant... --Stephan Schulz (talk) 20:24, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Power increases with the cube of speed, but the OP isn't talking about power (which is energy per unit time), but rather energy per unit distance. That cancels one of the speed factors, so turns the cube to a square. Alternative proof: Air resistance, as a force, is proportional to the square of speed (this is well known). Energy=Force x distance (for constant force, which we have), so energy per unit distance is just force. --Tango (talk) 21:20, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Above ten miles an hour, you're always going to use more energy the faster you go. The most important factor for rolling resistance is your tires -- you want the thinnest, smoothest tires with the highest air pressure. The problem with pushing that to the limit, though, is that with "racing" tires you get a heck of a lot of flats (and keeping them inflated is a bore). The next most important factor is to have good bearings that are well lubricated. The next most important factor, I think, is the frame, and particularly the fork -- a carbon fork is very springy and doesn't absorb much energy from the roughness of the road. Looie496 (talk) 21:56, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- The most important factor is actually getting a well-fitting bike. Bikes are quite efficient machines, so you are bound to lose more energy due to bad ergonomics than due to rolling resistance. And, surprisingly, all other things being equal, a fatter tire has a lower rolling resistance than a slimmer one. Slimmer ones are lighter, have less air resistance, and are faster to accelerate, but at the same pressure, they actually have higher rolling resistance. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 22:20, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Recumbent bikes have far less air resistance than normal ones, especially the fully enclosed ones. Thus they need less energy to move, or your top speed is far higher. CS Miller (talk) 23:27, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- The most important factor is actually getting a well-fitting bike. Bikes are quite efficient machines, so you are bound to lose more energy due to bad ergonomics than due to rolling resistance. And, surprisingly, all other things being equal, a fatter tire has a lower rolling resistance than a slimmer one. Slimmer ones are lighter, have less air resistance, and are faster to accelerate, but at the same pressure, they actually have higher rolling resistance. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 22:20, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

Would changing from knobbly tires to smooth ones make much difference in the energy required to travel a particular distance please? 78.151.144.28 (talk) 11:30, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Yes, it makes a noticeable difference, but the pressure in the tires makes even more of a difference (in my experience). Looie496 (talk) 17:21, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

What to do with left over cooking oil?

Is the any way to convert this into electricity (quietly) in a domestic situation? I have a small brick garden shed and a first floor flat with an attic, and it is possible to send a 240 volt cable from shed to my flat. Also, is there any way to power my 36 volt electric bike by the same method? [Trevor Loughlin]80.1.88.25 (talk) 14:28, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- There is a way to use used cooking oil to power an internal combustion generator, basically all you need to do is filter the oil and maybe make a few adjustments to the engine. So, you could power a generator. You would get an odor, but it actually smells good, like fried food. The noise is another problem, as neighbors wouldn't want to hear that at night. You could charge the batteries on the electric bike using such a generator, too. However, you would need large quantities of used cooking oil to make this all worthwhile, which usually means you need to have restaurant(s) willing to donate their oil to the cause. StuRat (talk) 14:48, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- (EC) You can find plenty of homebrew guides for making biodiesel from used/waste vegetable oil online. [1] [2] [3] www.ehow.com/how_5254968_make-biodiesel-out-waste-oil.html www.squidoo.com/Making-Biodiesel-At-Home-Using-Waste-Vegetable-Oil. I presume many diesel generators should work with this either directly or blended with regular diesel. (Generally people do it for cars where the conversions to run on waste vegetable oil are expensive, and damage and problems due to the oil difficult and costly to repair, and the tolerances and conditions required more difficult.) It's a lot of effort if all you have is a small amount of oil from home use however.

- A quick search also finds plenty of references to generators that can use the oil directly. E.g. [4] [5] [6] [7].

- However most of these look big so I'm guessing cost quite a bit and I somewhat doubt they'll be cost effective unless you want such a big generator for other purposes (e.g. if your house is completely off the grid) particularly if your only supply is from your home, unless you run some sort of home-business where you deep fry stuff and have large amounts of oil. This one for example is targeted to restaurants [8]. (Actually even a say $250 generator is not going to be cost effective but it's less extreme then buying a $5000 generator to use it for 30 seconds.) And getting another supply may not be easy, many restaurants are already selling their waste oil I believe (see Vegetable oil#Waste oil).

- You can of course try making or converting a generator yourself [9] [10] but I'm guessing this may be beyond your capabilities.

- BTW Vegetable oil fuel may be of interest.

- Incidentally, I wouldn't recommend running a mains wire by yourself, especially one that is exposed to the elements.

- Nil Einne (talk) 15:15, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- What you need is a diesel generator - these cost between $800 and $1500 (new). You can filter the oil and take measures to remove the water - and use that to power the generator - which in turn can drive electrical appliances - or power the battery charger for your bike. You do need quite a lot of oil to make this worth-while though. If you have just a couple of pints a week - or even a couple of pints per day - then the cost hand hassle of the generator would probably not be worth it. You'll need a diesel generator though - doing this with a regular gasoline powered generator would require converting the oil into gasoline and that requires a lot of complicated chemistry. See: Vegetable oil fuel and Biodiesel SteveBaker (talk) 15:58, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- It's easy to spend more money than your going to get back. The article on Domestic_energy_consumption show more energy is consumed (whether as gas, electric, oil etc.) for heating than for lighting. A Micro combined heat and power unit might be more economical if you are able to do the plumbing yourself. They can use gas (of most types) too, if you run short on oil. You might find Microgeneration a useful article to read for more inspiration. Also, make sure you have your roof fully insulated (there are all sorts of grants available for some of these things) and ask your down-stairs neighbour to turn his heating up in the winter, which will help save on your heating costs.--Aspro (talk) 16:31, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- You could perhaps try a model steam engine with a dynamo or a thermo-electric generator. Burning the oil direct like a candle has a fire risk and may be unhealthy like secondary smoking. 89.243.216.99 (talk) 18:33, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- If you heat with heating oil you might be able to just dump the stuff in your tank. And what do you know, we have an article on that: Bioheat. Ariel. (talk) 08:08, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Oil won't burn as readily, so it wouldn't be feasible to use it to run an engine, which needs a quick-burning fuel like gasoline to provide the sudden thrust of power.--Cheminterest (talk) 22:24, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

What if I built my own multi-cylinder Stirling Engine to run a generator, with a series of candle-like wicks to heat the bottom of the cylinder, but with the cooking oil instead of wax as the fuel? As for the amount of oil, my own fry-ups already amount to a gallon this month. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 80.1.88.1 (talk) 11:07, 27 April 2010 (UTC)

- What!?! You're considering this question for a gallon a month!! OK - I really wish you'd mentioned that at the outset. That's WAY too little to be considering anything fancy. It isn't going to produce enough energy to make it worth-while to build any complicated equipment. Consider that a gallon of diesel fuel (which is rather more energy-dense than cooking oil) costs a couple of dollars (US) - and an equivalent amount of electricity (at 10c per kWh) would run to maybe $4.00 (but bear in mind that your conversion of cooking oil to electricity would be maybe 20% efficient - so you'd maybe get more like $0.80 per gallon in electricity). So using this cooking oil could be saving you maybe $25 a year if you could run your car on it - or maybe $10 a year if you could turn it into electricity somehow. If you consider your personal effort to be worth minimum-wage pay rates then you can't spend much effort on doing this either! Any piece of equipment you might make or buy to use your oil is only likely to run without replacement for (let's be generous) 10 years. So just to break even, you can't spend more than $250 on it (if it's going to make biodiesel) or $100 (if it's going to make electricity) - and it certainly can't take a lot of your time and effort to do it. So sterling engines and generators and things like that are completely out of the question! You're reduced to burning it and using the heat directly - which might require little enough equipment to make it worth-while. If you have an oil fired heating system - then I'd just toss the used cooking oil into the tank...maybe consider filtering it through a coffee filter first to get bits of food out...but that's going to take time and you'd make much more money flipping burgers at McDonalds for one weekend a year than spending an hour a month carefully collecting and filtering your used cooking oil. At the low levels you're doing it at, the heating system wouldn't care about the type of oil. If you have a wood or coal-burning stove - you could certainly pour small amounts of cooking oil onto the fire after every fry-up and get benefit from the oil that way - with no filtering required. Anything else is never going to be cost-effective. SteveBaker (talk) 12:54, 28 April 2010 (UTC)

homoaromaticity in dimedone?

I'm trying to figure out why dimedone is almost as acidic as barbituric acid, compared to other diketones (3 pKa drop). One thing I've been thinking about is homoaromaticity (and the aromaticity-stabilisation for barbituric acid probably is significantly reduced because of the number of heteroatoms and EWGs involved). John Riemann Soong (talk) 17:23, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

Oh the same inquiry especially goes to Meldrum's acid, which would appear to have 6pi electrons. John Riemann Soong (talk) 17:28, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- This is continuation/follwup of Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2009 November 23#acidity of dimedone, barbituric acid and acetylacetone. DMacks (talk) 17:54, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

Anyone? This is a REALLY curious phenomenon. Why is it so ill-studied? John Riemann Soong (talk) 03:01, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- If you draw your ideas out in ChemDraw, I'll happily have a think about them. At the moment it's a bit difficult to see what you're seeing.

- The anion of Meldrum's acid (deprotonated at the doubly-α position) definitely doesn't look aromatic. When you say "...has 6π electrons" and discussing aromaticity, I assume you are considering primarily the resonance-form of each ester group (oxonium/carbonyl in ring and oxy-anion attached to ring rather than neutral/ether/lone-pair in ring and carbonyl attached to ring)? Regarding barbituric acid, was it ever proven whether the reported thermodynamic pKa is actually for the doubly-α position rather than an amide N-H? That would be a quick'n'easy NMR study. DMacks (talk) 17:19, 27 April 2010 (UTC)

- I think it was evident from syntheses involving barbituric acid. You add a little base, some electrophile... boom! I was thinking Meldrum's acid could have weak aromaticity (sort of like aromatic equivalent of paramagnetism) through homoaromaticity. John Riemann Soong (talk) 10:40, 28 April 2010 (UTC)

- Hold on, I'm rushing for an assignment right now. I shouldn't even be on RD. I'll get back to you in 3 hours. ;-) John Riemann Soong (talk) 10:42, 28 April 2010 (UTC)

Volcanoes

How do volcanoes make lightning? In the news a few days ago, they showed a picture of that volcano in Iceland with lighting coming out of the ash cloud. Also, the cover of my physics textbook has a picture of Sakurajima with a bunch of lightning coming out of it. --75.34.67.8 (talk) 17:49, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Somewhat off the top of my head, I believe it is just static electricity generated through friction, similar to 'normal' lighning, though it appears the exact mechanism, as for lightning, is not understood completely. See Dirty thunderstorm, also a mention in the WIkipedia Lightning article. This site might help thunderbolts.info though it seems rather "fringe science" on a quick look (looks like your Sakurajima piccy too). This National Geographic article, Volcanic Lightning Sparked by "Dirty Thunderstorms" and this one New Lightning Type Found Over Volcano? seem more reliable. And this IEEE—Volcanic Lightning article. Try this pic from Chile Chaitin volcano, May 3 2008 Awesome! There is actually a lot on the net, try Googling "volcano lightning cause" for more info.--220.101.28.25 (talk) 19:00, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Here is a site that has some good technical attempts to explain the phemomena. geology.com --220.101.28.25 (talk) 19:32, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- The ash particles collide and separate into positive and negative charges, similar to the collisions in cumulonimbus clouds involving ice particles and supercooled water droplets. ~AH1(TCU) 23:17, 28 April 2010 (UTC)

Is this correct?

An atom is moving in the +x direction and a laser beam is headed in the -x direction. The atom absorbs a photon and emits it in the -x direction. What is the photon's energy?

Answer: I think that in the atom's reference frame, the photon's energy is hf*sqrt(1+v/c)/sqrt(1-v/c) before absorption. After emission, the photon's energy is still hf*sqrt(1+v/c)/sqrt(1-v/c) in the atom's reference frame. However, blueshifting this into the lab's frame gives hf*(1+v/c)(1-v/c) = hf*(1+2v/c). Is this correct? --99.237.234.104 (talk) 18:01, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- This is a very tricky question, but I think the energy does not change. Are we assuming the photon is emitted with the same frequency that was absorbed (relative to the atom)? The light is blueshifted relative to the atom when absorbed. The photon is then redshifted relative to the atom when emitted and ends up back where it started. The atom basically did nothing - it picked up the photon, and then let it go. Perhaps the assumption is that any energy absorbed is then emitted? That gives the same result. Are you wondering if the atom can give the photon energy in some way? From the atoms point of view, it's not moving, and has no energy to give the photon. The only way the system as a whole can transfer energy from the atom to the photon, would be to slow down the atom, and speed up (well, "mass up") the photon, but conservation of momentum does not allow that, because a heavier photon would give the atom a larger kick - but then the atom is actually moving faster, not slower. Ariel. (talk) 07:48, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- (OP here) What do you mean by "the photon is then redshifted relative to the atom when emitted"? Assuming that the atom's momentum is much larger than the photon's, the photon should have the same frequency relative to the atom as it did before absorption: in other words, hf*sqrt(1+v/c)/sqrt(1-v/c). However, in the lab frame, moving at speed v relative to the atom, the emitted photon should appear blueshifted: E=hf*sqrt(1+v/c)/sqrt(1-v/c) * sqrt(1+v/c)/(sqrt(1-v/c). This is approximately hf(1+2v/c). I think this should be the answer, but I have an answer key that contradicts this, saying that E=hf if only terms first-order in v are considered. --206.130.23.2 (talk) 16:25, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- You are right, I meant observer not atom. Let me start over. The observer is located at -x. He sees the photon emitted, with no shift. The atom sees the photon with a blueshift, and absorbs it. The atom then emits the same (higher) frequency it absorbed. To the atom this emitted photon in not shifted, but it is at a higher frequency that it started. To the observer the emitted photon is redshifted, because the emitter (the atom) is moving away from the observer. The end result is no change. Ariel. (talk) 20:47, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- If you make your frame of reference the atom, then the atom absorbs and emits the same, unchanged (from it's point of view) frequency. How do you know the atom did not change speed? Because it absorbed momentum by catching the photon, it then lost exactly the same momentum be emitting it. So it could not have changed in speed. No (net) change in speed for the atom means the photon's energy could not have changed. Ariel. (talk) 21:14, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- If you choose the +x observer instead, then you might think that when the photon is emitted from the atom it's blueshifted - since it's heading toward you. But actually, think about it in a different way. The photon is emitted with full speed, but the motion of the atom is away from the direction of the photon, meaning that the photon now is slower (since the motion of the atom robbed it of some speed). Photons are not actually slower, instead it red shifts. This also is correct if the observer is at -x. It's actually correct for all observers. Because the motion of the photon, and atom are opposites, it makes no difference where the observer sits. Ariel. (talk) 21:14, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- That makes perfect sense. I don't know what I was thinking; I was just having another mental block. Thanks. --99.237.234.104 (talk) 21:53, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

Small windmill for electricity

I saw what looked like a home-made windmill recently, about a meter in diameter. It had blades all the way around, like the old fashioned things used on farms for pumping water, so it was not just a propeller. It was turning what may have been a bicycle dynamo. Has anyone any idea how much average power it would provide under average conditions? Thanks 89.243.216.99 (talk) 18:01, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- I don't think a one meter windmill is going to do you much good. A carefully constructed (but homemade) three meter windmill on at least a 20 meter pole (to get it above roof and tree height) will produce about 1kW.hr per day in the right location. Most homes consume 10 to 20 kW.hr per day...so don't get too excited about living off the grid! You can basically use the thing to drive a car alternator and thereby charge a bank of car batteries - and then use an inverter to turn that into mains A/C voltage so you can run things from it. If you have the tools and the DIY expertise, you could probably knock one up for a couple of hundred bucks. People who spent a lot of money (like maybe $15,000) on small, commercially made, windmills have had very mixed results. Some find that they perform no better than the home-built contraptions, on occasion not producing enough energy to run their own electronic control modules! Others seem to be getting maybe 50% of their household power from them. But that's not gonna be remotely cost-effective. If your electricity bill is (let's say) $200 a month - and the windmill is saving half of that - then it's going to take 150 months to pay for itself (well, actually more than that because you could have invested that $15,000 and made interest from it). Will the windmill actually last the 15 to 20 years it takes to pay for itself? I very much doubt it. The trouble with wind power is that it's horribly bad at small-scale installations. If you could get a few hundred neighbors to invest in a one megawatt windmill that you'd all share, then probably it would be worthwhile - but at the scale you can manage by yourself, I don't think windmills are the answer. Solar panels offer much more opportunity for cost-effectiveness - but only if you live somewhere with year-round sunshine. From every angle I've investigated, by far the most cost-effective thing you can do is to conserve energy with better home insulation, energy-efficient appliances and that kind of thing. SteveBaker (talk) 19:26, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Depends. In the UK the grid companies are now obliged to buy the power back from you at three times the grid price, even if you use the power yourself (ie they have to sell what you use back to you for a lot less than they just paid you for it). They pay about 30p a unit whereas cheap rate night power in the UK is about 5p a unit and peak rate about 10p a unit. Reasonably site gives about 8 years payback on that basis. The societical sense is a bit more arguable but the political argument is that this is the only way to get enough units built to get the cost down. --BozMo talk 19:46, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- That seems ripe for someone to find a cheap way to draw and store as much 5p power as possible and sell it all back for 30p. Dragons flight (talk) 22:14, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Hmmm... now how does one go about building a pumped storage hydroelectric generator, I'm sure no-one will notice if I flood the abandoned quarry at the top of the hill. I'm going to be rich! 131.111.185.69 (talk) 22:33, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- That seems ripe for someone to find a cheap way to draw and store as much 5p power as possible and sell it all back for 30p. Dragons flight (talk) 22:14, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Depends. In the UK the grid companies are now obliged to buy the power back from you at three times the grid price, even if you use the power yourself (ie they have to sell what you use back to you for a lot less than they just paid you for it). They pay about 30p a unit whereas cheap rate night power in the UK is about 5p a unit and peak rate about 10p a unit. Reasonably site gives about 8 years payback on that basis. The societical sense is a bit more arguable but the political argument is that this is the only way to get enough units built to get the cost down. --BozMo talk 19:46, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

30p a unit? I wonder if that makes buying a "proper" windmill a good investment.

I have always been intrigued with the idea of having a twelve volt wiring system in a house in addition to the 220v (or 110v) one, and using the fittings designed for caravans, such as 12v lighting, 12v fridges, and 12v TVs. Then you might be able to avoid using mains electricity completely. Since its only 12v, it should be safe for competant non-electricians to do the wiring. Even very inefficient home-made windmills that cost very little could be worth having, and you could have several. Energy-saving lightbulbs only use a few watts, so perhaps they could be run although there would be the problem of stepping up the voltage.

Sometimes old houses have wells in the garden, so I wonder how much money would be saved by going completely off-grid in the Uk or elsewhere? 78.151.144.28 (talk) 09:39, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- You would need some seriously fat wires to run things at 12 volts. You would not save any money at all going off grid - you would spend much more. If people could save money going off grid everyone would be doing it already. Also, if you wire an entire house with 12 volts, you would have a ton of amps going through those wires - any mistake in the wiring and you would have a fire. So, going 12 volts will not let a non-electrician do the wiring. You might not electrocute yourself, but that's not the only hazard available with electricity. Ariel. (talk) 09:54, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

I'm doubtful you would get a "ton of amps" off a 12v car-battery set up. 78.151.144.28 (talk) 10:09, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Car batteries (lead-acid batteries) have a very low internal resistance and they can pump out hundreds of amps in the case of shorts (which is useful for starter motors, but not for house wiring). --antilivedT | C | G 11:24, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- People have been electrocuted and died with as little as 3 volts - and you can easily take a 1,000,000 volt shock from an electrostatic discharge with no ill effects. It's not the voltage that kills you! You can most certainly be killed with the current from a car battery - and you can also start fires that way. SteveBaker (talk) 12:22, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Best solution for home generation if you are already on or are close to the grid is an inverter so you can use ordinary AC appliances. But you could have one DC socket straight from it, for example to charge an electric car or perhaps to heat water for storage. Itsmejudith (talk) 17:09, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

Mass wrapping around a rod

Mass m is attached to a post of Radius R by a string. Initially it is at a distance r from the center of the post and is moving tangentially with speed v0, and as the mass moves the string wraps around the rod. What is the final speed of the mass?

That angular momentum is not conserved I understand. But according to: http://physics141.uchicago.edu/2002/hw6.pdf (middle of second page) the total energy is conserved. I don't see why the tension wouldn't do any work. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 173.179.59.66 (talk) 18:05, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- It depends

whetherhow muchyouyour professor wants to simplify, and assume that the string is perfect/ideal/does not stretch or deform. In that case, the string length is exactly constant, and the only change in radius is due to the string wrapping around the pole. If you want to add complexity, you can add two parameters to the string: elastic stretching, which you can model with Hooke's law; and inelastic deformation, which you should model based on an empirical estimate. In any case, angular momentum is always conserved; it is just that you are only considering the rod/string in this problem; those do not constitute a closed system. The angular momentum is transferred outside of that system, to the person holding the rod (or to the Earth, if the rod is planted in the ground); and can be ignored for your considerations. - To estimate a spring constant for the elastic stretching of the string, I would suggest treating the string as an extremely stiff spring (say, thousands of newtons per meter for the spring constant). Of course, this value depends on the type of fiber the string is made of. For the inelastic deformation, we are modeling how much the string permanently degrades (fibres unwinding and changing microscopic position and shape). This is very hard to model, but easy to estimate from measurements. Work is done on the string to deform those fibres; some energy goes into heat, and some goes into the process of changing the material properties of the fibre. How much energy is used will depend on the fibre properties.

- You can use the elastic model to simulate dynamics - but you should use a Lagrangian mechanics formulation, because you have multiple variables in an arbitrary coordinate-system (radius, height above ground, and string stretching displacement); each coordinate is described with its own set of kinetic and potential energy terms. Adding the inelastic term will be sort of like adding a "frictional loss" term; it may be best to simply approximate that with an "engineering fudge factor" numerical constant, so that you can match the modeled velocity and wind-up time to experimentally observed times. This is the "work" that is being done by the tension (really, only the inelastic deformation constitutes "work" / energy loss - the elastic stretching will cause a dynamic oscillation, but the net work done by that component is zero). (Well, if you want to be very complicated, you can use a more sophisticated spring law than Hooke's Law; then you could model separate dynamic losses for the oscillation that are distinct from the inelastic deformation; but this adds parameters that you need to experimentally measure, and it is not clear that the oscillatory loss would be caused by a different physical effect than the inelastic deformation anyway - so modeling it separately is dubious).

- In any case, you can see that the added complexity may require messier math, more parameters, and (possibly) require a formulation of physics, Lagrangian mechanics, that has not been introduced to you yet (though you could try to do this with strict Newtonian mechanics, the algebra and the integrals will be very ugly and hard). Furthermore, it is reasonable to assume that the string stretching is "small" for most real problems (aside from rubber bungees). So, it may be easier to simplify than to include this added terms. Nimur (talk) 18:37, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- I'm assuming the string is ideal (and based on your answer, I'm glad I am). It's just that...as the mass starts falling in, isn't the tension applying a force which isn't perpendicular to the velocity. If it's pulling in the mass, it seems to me that it must... 173.179.59.66 (talk) 20:52, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

Actually I see it now, thanks. But what force applies the torque??? Is it the contact force between the rope and the string? Because then R and F would be parallel, and so I would expect no torque.173.179.59.66 (talk) 20:59, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Note that the string pulls on the mass at any given time in the direction of the edge of the pole where the string touches the pole. As the string is winding itself around the pole, that point is changing, but what is important to realize is that the direction of the force is always some point on the edge of the pole and not the center of the pole.

- So, you see that the torque relative to the instanteneous contact point of the string on the pole is always zero, but then the torque relative to the center of the pole is not zero. Count Iblis (talk) 21:54, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

Any chance of getting a reactionless drive out of this method?[Trevor Loughlin]80.1.88.1 (talk) 10:59, 27 April 2010 (UTC)

Detonations and the like

I should really know this but if I filled a small plastic fizzy drinks bottle with a liquid and the liquid blew off both ends (classic flower petal each way) does that definitely mean the liquid detonated? I was trying to blow the bottle up (essentially with compressed gas) but I was a bit surprised to see both ends go because I did not think the mixture was detonable. Presumably the drinks bottle are designed with a failure mode and I daresay it got hot but I cannot see why unless the pressure rose significantly on a timescale similar to the acoustic time between the ends one end shouldn't inevitably go first... what am I missing? --BozMo talk 19:41, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- If you slowly raise the pressure, you are likely to get a single point of failure, that's true, but it is still possible to get multiple, simultaneous points of failure, as you also get in an explosion. StuRat (talk) 19:47, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- Hmm. You said the bottle was full of liquid, but then you said you were trying to blow it up essentially with compressed gas. Please clarify. Looie496 (talk) 21:40, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- What did you fill it with? --Dr Dima (talk) 22:39, 25 April 2010 (UTC)

- When we work with explosives, we use terminology very carefully (just like everything else). Usually we use detonation to describe the type of exothermic chemical reaction which produces supersonic gas - a shock front or shock wave. It is compared to deflagration, the type of exothermic chemical reaction that produces subsonic gas products. In your case you are not actually creating a chemical reaction at all - you are simply using a pressurized gas to expand explosively - so what you really have is a BLEVE - neither detonation nor deflagration - just rapidly expanding liquid and exploding vapor. Because you are using fizzy soda pop, your BLEVE gas is carbon dioxide, which is actually not ever in liquid state (only dissolved in water) - so the quantity of energy you release is small by comparison (the CO2 never boiled from liquid state, it just came out of solution). Also, carbon dioxide does not burn (in fact, it is a common fire extinguisher ingredient). So, your BLEVE is actually just a "EVE" - expanding vapor explosion. Do not try to create a BLEVE with other gases - some will rapidly combust on contact with atmospheric oxygen if the pressure and shock front conditions are right, and can not be easily extinguished. Nimur (talk) 00:23, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- (nighttime in the UK intervened) I was using the words carefully I thought and was asking about detonation. The mixture I was using was finely powdered mixed citric acid and KMnO4 with a dribble of water. I got banned from Chemistry as a school child for this mixture because of its delightful property of doing nothing for nearly a minute before eruptively evolving CO2 furiously and smothering everything with boiling MnO2 which is very destructive to teacher's clothing, skin etc (sigh, happy memories). But in general it just got hot and evolved gas. With the right proportions (no clues) sealed in a pop bottle it turns out it blows both ends of simultaneously. I am surprised if it is detonable but perhaps with the heat and pressure of the bottle it can be? --BozMo talk 06:25, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- FWIW though I think StuRat is probably right it was probably a coincident failure of the ends. --BozMo talk 10:42, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- I'm no expert, but I am pretty sure that permanganate-acid reactions do not create a shock-front (it is a very slow reaction as you are already aware). All you have done is over-pressure your container, which is not a detonation, properly. High explosive detonates even if uncontained; that is what makes them "high" (dangerous) and subject to legal and logistics controls. If you performed the same reaction without a soda-pop bottle, your reaction would fizz a bunch, but there would be no "exploding." Nimur (talk) 16:14, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- FWIW though I think StuRat is probably right it was probably a coincident failure of the ends. --BozMo talk 10:42, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- (nighttime in the UK intervened) I was using the words carefully I thought and was asking about detonation. The mixture I was using was finely powdered mixed citric acid and KMnO4 with a dribble of water. I got banned from Chemistry as a school child for this mixture because of its delightful property of doing nothing for nearly a minute before eruptively evolving CO2 furiously and smothering everything with boiling MnO2 which is very destructive to teacher's clothing, skin etc (sigh, happy memories). But in general it just got hot and evolved gas. With the right proportions (no clues) sealed in a pop bottle it turns out it blows both ends of simultaneously. I am surprised if it is detonable but perhaps with the heat and pressure of the bottle it can be? --BozMo talk 06:25, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Again, just for the sake of droning, do not play with dangerous chemicals unless you know what you are doing. I mean, we're just random people on the internet and we can't stop you from doing whatever you are doing - but if you were thrown out of chemistry class, it's probably because you did something unsafe. Energetic materials can be a lot of fun, but you need to follow proper, cautious procedures - and the only way to do so is to learn from experts. At the high-school level, those experts are your chemistry and physics teachers. If you satisfy all of their (not so difficult) intellectual and safety criteria, you can move on up to playing with more interesting things - but it doesn't matter what kind of rocket scientist, construction engineer, or military demolition expert you are - people who work with energetic materials do not tolerate recklessness. (This includes splashing even harmless chemicals on lab benches. It sets a bad precedent). Nimur (talk) 16:25, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- In so far as this is directed at me, this is a reasonable remark but a little out of context. A couple of decades ago I spent a few years in industrial research blowing up some fairly major bits of kit (three people working for me had "fit persons" licences for high explosives and we had fun). I am now more interested in bucket chemistry to do with my own kids which is why I would rather avoid possible detonations. Mn2O7 of course detonates and permangate with strong acid is therefore worth avoiding. But as you I am reasonably sure that unlike nitrates etc it is otherwise relatively ok. I made fireworks as a kid myself and am kind of looking for something safer. --BozMo talk 16:37, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- It seems at least theoretically feasible to get an explosion (if not detonation) that way. If the reaction is slow enough that a lot of CO2 dissolves into the liquid, then once the pressure is released by one end of the bottle blowing, the CO2 will start to come out of solution, further raising the pressure. Another factor is that when one end blows off, conservation of momentum will cause the liquid inside to be hurled in the other direction. If the bottle was being held in place by something (not specified here), it seems like this could easily be enough force to blow out the other end. Looie496 (talk) 17:19, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- It is not a permanganate-acid reaction. Any reducible carbon compound (most of them are) such as sugar can be used, but some are better than others. The MnO2 is a staining solid. You could react permanganate with glycerin to produce gas, or just react baking soda with 10M hydrochloric acid. It will probably burst the bottle if you can find a way to detonate it once the lid is closed. It may be considered deflagrating though. --Cheminterest (talk) 22:21, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- This is the reaction that was going on:

- It is not a permanganate-acid reaction. Any reducible carbon compound (most of them are) such as sugar can be used, but some are better than others. The MnO2 is a staining solid. You could react permanganate with glycerin to produce gas, or just react baking soda with 10M hydrochloric acid. It will probably burst the bottle if you can find a way to detonate it once the lid is closed. It may be considered deflagrating though. --Cheminterest (talk) 22:21, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- When we work with explosives, we use terminology very carefully (just like everything else). Usually we use detonation to describe the type of exothermic chemical reaction which produces supersonic gas - a shock front or shock wave. It is compared to deflagration, the type of exothermic chemical reaction that produces subsonic gas products. In your case you are not actually creating a chemical reaction at all - you are simply using a pressurized gas to expand explosively - so what you really have is a BLEVE - neither detonation nor deflagration - just rapidly expanding liquid and exploding vapor. Because you are using fizzy soda pop, your BLEVE gas is carbon dioxide, which is actually not ever in liquid state (only dissolved in water) - so the quantity of energy you release is small by comparison (the CO2 never boiled from liquid state, it just came out of solution). Also, carbon dioxide does not burn (in fact, it is a common fire extinguisher ingredient). So, your BLEVE is actually just a "EVE" - expanding vapor explosion. Do not try to create a BLEVE with other gases - some will rapidly combust on contact with atmospheric oxygen if the pressure and shock front conditions are right, and can not be easily extinguished. Nimur (talk) 00:23, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

12 KMnO4 + 2 C6H8O7 → 12 CO2 + 2 H2O + 12 KOH --Cheminterest (talk) 22:29, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

April 26

Stingray question

Do stingrays make a sound. I have looked extensively and have not found anything about stingrays making noises of any kind. thank you for considering this question. :)174.97.235.163 (talk) 00:45, 26 April 2010 (UTC)pat

- Somehow I doubt it, as most fish don't (at least nothing we can hear). StuRat (talk) 00:51, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Did you have something in mind, particular to a stingray? I used to have an electric catfish as a pet and it made lots of noise at night while electrocuting the minnows. Perhaps a stingray makes a sound (in the most general sense of 'making a sound') when it thrashes it's stinger into predator/prey...I mean, more so than a goldfish, let's say. DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 01:27, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- In this youtube video you can hear a clicking noise and you see a stingray: Octopus Attack - Fuertaventura 2009. Cacycle (talk) 06:53, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Did you have something in mind, particular to a stingray? I used to have an electric catfish as a pet and it made lots of noise at night while electrocuting the minnows. Perhaps a stingray makes a sound (in the most general sense of 'making a sound') when it thrashes it's stinger into predator/prey...I mean, more so than a goldfish, let's say. DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 01:27, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Of course every type of fish makes sound as a result of water sliding over its body. When it comes to other types of sound, I wasn't able to find any reports in a quick Google Scholar search. There are apparently certain types of fish that "vocalize" by vibrating their swim bladders, but elasmobranches (sharks and rays) don't seem to be among them as far as I can tell. Looie496 (talk) 17:10, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

is there an exit valve? what about on the scuba fireman where? and on oxygen tanks in a ambulance or hospital?

where does the exhaled air go —Preceding unsigned comment added by Tom12350 (talk • contribs) 01:36, 26 April 2010

- This question was answered above. Look for the section about 2-3 days ago labeled "scuba". --Jayron32 02:40, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

no they answered about scuba not scuba fireman where and on oxygen tanks in a ambulance —Preceding unsigned comment added by Tom12350 (talk • contribs) 05:21, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- In a hospital or ambulance oxygen is normally given in two ways. In an emergency where a patient has collapsed and respiration is administered with a mask and pump bag the pump bag apparatus has an exit valve. When oxygen is given over a longer period with a light mask or little tubes at the entrance to the nose then the excess oxygen just dissipates into the atmosphere as there is no closed circuit to contain it. I suspect that the equipment used by firemen is similar in design principle to an underwater scuba, a closed circuit with a one-way exhaust valve. Richard Avery (talk) 07:21, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- On the side of the mask. See if this article helps: Firemens SCBA apparatus and and Oxygen maskAnd see diagram on the right --Aspro (talk) 07:23, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- And again, to be pedantic - the firemans' apparatus is an "SCBA" because the 'U' in "SCUBA" stands for "Underwater". SteveBaker (talk) 12:17, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

you say "light mask or little tubes at the entrance to the nose then the excess oxygen just dissipates into the atmosphere as there is no closed circuit to contain it."

but hows that because isint the mask tight? like is this pic ?

http://thumbs.dreamstime.com/thumb_54/1145221626xhnGC8.jpg

or this

http://fransonchiropractic.files.wordpress.com/2009/04/oxygen20mask.jpg

or this

http://www.watersafety.com/rescue-and-response-equipment/images/4225023.jpg —Preceding unsigned comment added by Tom12350 (talk • contribs) 22:07, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

milk

can buffered solutions like milk be used to naturalize acids or will it not work cause its buffered. —Preceding unsigned comment added by Tom12350 (talk • contribs) 01:55, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- So long as you don't exceed the buffer capacity of the milk, yes, it can be used to neutralize acid. The property of a buffer is that it works to neutralize BOTH acid and base (more properly, a buffer is something that maintains a constant pH with the addition of either acids or bases). See buffer for more info. --Jayron32 02:39, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

what is the "the buffer capacity of the milk" —Preceding unsigned comment added by Tom12350 (talk • contribs) 05:20, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Please start signing your posts by using four tildes like this: ~~~~. Please read the Buffer solution article for more info. A buffer is basically an acid and its conjugate base. That is, it consists of a pair of compounds that differ by a hydrogen ion, for example a solution that contained both acetic acid, HC2H3O2, and the acetate anion, C2H3O21- would be a buffer. It works because, by adding either acid or base, the conjugate acid/base pair works by reacting with either an added acid OR an added base, and so neutralizes either. Also, because the system is a dynamic equilibrium, the system obeys Le Chatelier's principle such that it resists all changes to return to its initial state. The buffer capacity merely means that the buffer only exists so long as both parts of the conjugate acid/base pair exist in the solution. If you add so much acid that you use up the base part of the buffer, then you no longer have a buffer, and you have exceeded the buffer capacity. --Jayron32 05:27, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Additionally, you should probably also read up on Brønsted–Lowry acid-base theory which is the basis for understanding how buffers work. --Jayron32 05:30, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

i already read those. what is the "the buffer capacity of the milk" —Preceding unsigned comment added by Tom12350 (talk • contribs) 06:35, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- I just explained that. A buffer consists of an acid and its conjugate base mixed together in water. If you add too much additional acid, you will consume all of the base, and thus destroy the buffer. --Jayron32 12:02, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- I'm not sure but perhaps the OP wants to know what the buffer capacity of milk actually is, not what it means. Having said that I wonder whether the OP actually properly understands buffer capacity or thinks it's a simple value that tells you precisely how 'powerful' a buffer is. In any case, the buffer capacity would vary depending on the type of milk I presume. Edit: These should provide a basic overview on what the buffer capacity of milk actually is [11] [12] [13]. Also [14] if you can find it. Nil Einne (talk) 12:32, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- With a complex solution like milk, it would be quite impossible to calculate directly. You could certainly do an experiment to find the value for yourself. You would need to titrate the milk dropwise with a strong acid, and track the effect of the added acid on the milk's pH. Then you would need to do the same experiment, but with fresh milk and a strong base. The resulting graphs should tell you roughly how much acid or base you can add before exceeding the buffering capacity of the milk. (after edit conflict) It looks like Nil Einne found the results of some of those experiments above. --Jayron32 12:46, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

i dont need a exact value just a estimate. anyone know? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Tom12350 (talk • contribs) 21:56, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- From the article that requires a subscription: At pH7, the buffering capacity (dB/dpH) looks like it's around 0.02. It changes a lot depending on pH - eg. at pH 6 it's closer to 0.03. Aaadddaaammm (talk) 13:43, 27 April 2010 (UTC)

hats that mean? how strong a acid can it be used on —Preceding unsigned comment added by Tom12350 (talk • contribs) 21:15, 27 April 2010 (UTC)

- "Used on" to do what? Maybe if you rephrase the original question, with more specifics about what you're actually trying to do we could help more. Aaadddaaammm (talk) 10:36, 28 April 2010 (UTC)

Source of pneumonia in bedridden elderly?

From what sources do the elderly often contract pneumonia? I'm thinking of bedridden individuals in nursing homes who are not likely to be able to spread it to other individuals in similar conditions, and who (because they're in the nursing home, not in hospital) by definition can't get hospital-acquired pneumonia. I don't see anything in our article that discusses the question, since it seems unlikely to me that the large number of elderly people who die from it are all infected with fungi, parasites, pneumonia-causing bacteria, or pneumonia-causing viruses when those around them don't have any of these problems. Nyttend (talk) 02:29, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- I think part of the problem is a lack of ability to clear the lungs while bedridden. Thus, any standard cold or flu can cause fluid accumulation in the lungs, which can suffocate the bedridden person. I am pretty sure that is the impression I get from the issue. I could be wrong though. --Jayron32 03:50, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Also see the short article Aspiration pneumonia, which describes any non-infectious pneumonia caused by the inhalation of material, including one's own saliva and mucus. My guess is that this could explain many of these elderly, bedridden pneumonia cases. There's also Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, "Idiopathic" being doctor speak for "We haven't the faintest clue what is causing this". --Jayron32 05:37, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

Hubble's "visible spectrum" image of the Carina nebula

I'm wondering what the moon, or the earth would look like if an image were compiled in the same way that the Carina nebula was. (wavelengths detailed here). Is it relatively simple to attempt this? 219.102.220.42 (talk) 02:30, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- If you could obtain the raw images taken at those wavelengths which record those spectral colours then yes. One could easily do the next stage of combining and balancing them in to one image. This image manipulation could be done with GIMP (which I have noticed the Jet Propulsion Laboratories in Pasadena have used) or Photoshop, etc. This web page explains in plain language, the technical bits about what needs to be recorded .Cameras and H-a Emission Nebulas. And what would Earth and the Moon look like? Well I sure: if people were able to mentally work that out, there would be no point using these imaging technique in the first place. However, the United States Geological Survey Spectroscopy Lab has some images of Earth. And the Jet Pro Lab has some images of the moon. [16] As always, Wikipedia has some articles:Imaging spectroscopy, Moon Mineralogy Mapper.--Aspro (talk) 08:00, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Which elements do you want to use to make your images of the moon/earth? The picture basically shows areas where one element or another are more concentrated. If you use elements in the earths atmosphere, you'll have a white circle and nothing more, since those are basically perfectly mixed. If you choose elements on the ground, you'll see colors showing you where the elements you chose are more/less concentrated. Ariel. (talk) 08:05, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Those nebula are emission nebulas wich emit light at particular wavelengths in a line spectrum. The earth and moon reflect are much more continuous spectrum, and so are not so easy to establish elemental composition by transition lines. In visible light what you see will be a good clue, eg yellow iron oxide, green chlorophyll. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 09:10, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

Dibenzodiazepines follow-up

I notice all the compounds listed in Category:Dibenzodiazepines are antiaromatic. So it must not be a coincidence. I guess the antiaromaticity destabilisation must not be very large? I'm curious about the relationship between conformation and agonism / antagonism of the target receptors. AFAIK lysergic acid compounds are planar ... right? Or are they? I notice some resonance structures are antiaromatic in LSD too. John Riemann Soong (talk) 03:24, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- What counts most for receptor binding are shape and charge. Antiaromaticity per se does not have a direct effect on binding (whereas aromatic rings allow for specific interactions such as pi stacking). Cacycle (talk) 06:49, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Regarding LSD, the indole part is definitely aromatic. If you're considering "all the resonance possibilities" (treating them as distinct structures that contribute to the overall "real" average structure), you can mostly disregard antiaromatic ones if there are others that are aromatic. If you have an alkene or lone-pair or something that "maybe could resonate into a ring, but that would make antiaromaticity", that piece of the structure probably does not do that, and thus acts like an independent functional group. DMacks (talk) 08:47, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks... I was wondering because it doesn't appear to be a factor in LSD, whereas I can envision resonance structures in clozapine that would make it aromatic, not antiaromatic, e.g. by simply drawing benzene a different way. You know what I mean? John Riemann Soong (talk) 20:11, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- If you're interested in stereoelectronics in medicinal chemistry, you might like to get a good book on the topic, like this one, or search the literature. I did a quick Google search for "stereoelectronic QSAR" and found several interesting-looking articles, including Dynamic QSAR: A New Search for Active Conformations and Significant Stereoelectronic Indices.

- Further Wikipedia articles of interest:

- Books you could borrow from a library:

Life expectancy of nuclear power plants.

What is the average life expectancy of a nuclear generating station? How do plants built in the US differ from ones overseas in terms of longevity? ataricom (talk) 05:00, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- According to Nuclear power#Economics, a reactor can last as long as 40-60 years. Dismas|(talk) 07:27, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Not if they are destroyed by sea level rise. ~AH1(TCU) 23:14, 28 April 2010 (UTC)

- So don't build them so close to water. BTW, isn't one of the reasons for building nuclear reactors the fact that they can generate electricity without polluting the atmosphere (barring an extremely unlikely Chernobyl-style catastrophic nuclear meltdown, of course)? 76.103.104.108 (talk) 02:08, 29 April 2010 (UTC)

- Not if they are destroyed by sea level rise. ~AH1(TCU) 23:14, 28 April 2010 (UTC)

Ant for ID

Hello! I must catch 10 of this type of ant everyday in my house. Is this a fire ant or a carpenter ant? What is the best way of getting rid of them, sort of calling an exterminator as a last resort? Could they be living outside my house in nests or in my house's foundation? I've found winged ants in my house, as well, which, as I understand, are the ones who help reproduce. Is that a bad sign? Any advice appreciated. Thanks.--el Aprel (facta-facienda) 08:17, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- If this was Australia I would say you had a sugar ant. Fill up all the holes they may come in through. You can spray poison around, but may poison you and may not last either. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 09:04, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- I'm not sure, but it does look like Camponotus sayi, red carpenter ant, to me. Red link for the red ant - isn't it ironic? Not really a harmful critter, there are much worse than it; but it can build nests (colonies) in wooden structures which is not something homeowners generally like. This article gives suggestions on how to deal with them, if that ant is really what I think it is. As I said, I am not sure. --Dr Dima (talk) 10:07, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- No. Unless of course, their there on vacation. 'Florida' has however, narrowed it down a bit. Here's our next suggestion. Go to | Florida Ants. On the right hand column, under the heading 'Tools” is a link entitled - Florida ants in Google Earth. This link then gives you a map of which ants occur in which localities. I don't know how accurate it is but it looks impressive. In the mean time, see if they like water with some sugar added, because then use could try using borax.--Aspro (talk) 20:43, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Did you mean to type "THEY'RE there on vacation"? Cuddlyable3 (talk) 23:45, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Mix a little jam with borax and smear it inside saucers, jar lids or the like, and leave them near where you find the ants. Replace daily. The ants come and eat the jam, and the borax poisons them. You get borax from places which sell old-fashioned cleaning materials (it's jolly useful stuff). DuncanHill (talk) 22:02, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

You could also get borax (sodium tetraborate decahydrate) at the grocery store. It is normally sold there for laundry freshening and a host of other uses. Are you sure you aren't talking about boric acid though? --Cheminterest (talk) 22:16, 26 April 2010 (UTC)

- Not many grocers here sell borax anymore. I get mine at Boots the Chemists, and some old-fashioned hardware shops have it. Yes, I'm sure I mean borax. DuncanHill (talk) 22:32, 26 April 2010 (UTC)