Third Battle of Panipat: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

The picture that had been depicted seems to be of the lowest ranked Maratha soldier...Common Maratha soldiers looked sharp and elegant in their white attire with a distinct red 'pagdi' |

||

| Line 120: | Line 120: | ||

==Reasons for the outcome== |

==Reasons for the outcome== |

||

[[File:Maratha soldier.gif|thumb|Eighteenth century painting of a Maratha Soldier (by François Balthazar Solvyns)]] |

|||

The main reason for the failure of Marathas was that they went to war without good allies. Though their infantry was based on European style contingent and had some of the best French made guns of the times, their artillery was static and lacked mobility against the fast moving Afghan forces.<ref>{{cite book |title=Medieval India: From Sultanate to the Mughals Part - II|last=Chandra|first=Satish|authorlink= |coauthors=|year=2004 |publisher=Har-Anand|chapter=Later Mughals|location= |isbn=8124110662 |page= |pages= }}</ref> |

The main reason for the failure of Marathas was that they went to war without good allies. Though their infantry was based on European style contingent and had some of the best French made guns of the times, their artillery was static and lacked mobility against the fast moving Afghan forces.<ref>{{cite book |title=Medieval India: From Sultanate to the Mughals Part - II|last=Chandra|first=Satish|authorlink= |coauthors=|year=2004 |publisher=Har-Anand|chapter=Later Mughals|location= |isbn=8124110662 |page= |pages= }}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 08:41, 20 November 2010

| Third Battle of Panipat | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Maratha Empire, Durrani Empire | |||||||||

The Third battle of Panipat, 14 January 1761, Hafiz Rahmat Khan, standing right to Ahmad Shah Durrani, who is shown on a brown horse. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Sadashivrao Bhau Vishwasrao Malharrao Holkar Mahadji Shinde Jankoji Shinde Ibrahim Khan Gardi Shamsher Bahadur (Son of Bajirao) Sardar Bhivrao Panse (Artillery) Sardar Bhoite Sardar Purandare Sardar Vinchurkar (Infantry & Cavalry) Sardar Sidoji Gharge-Deshmukh(Cavalry) |

Ahmad Shah Durrani Najib-ud-Daula Shuja-ud-Daula Mian Ghulam Shah Kalhoro Tipu Sultan Shah Alam II | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 40,000 cavalry, 15,000 infantry, 15,000 Pindaris and 200 pieces of artillery,. The force was accompanied by 300,000 non-combatants (pilgrims and camp-followers). Thus, totally an army of 70,000. | 42,000 cavalry, 38,000 infantry in addition to 10,000 reserves, 4,000 personal guards and 5,000 Qizilbash, 120–130 pieces of cannon as well as large numbers of irregulars. Thus, totally an army of 100,000. | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 30,000 on the battlefield and another 10,000 in the subsequent massacre as well as 40,000 camp followers were either captured or killed. Therefore 80,000 casualties. | 3500 total | ||||||||

| India's Historic Battles: From Alexander the Great to Kargil By Kaushik Roy (2005) Published by Orient Longman, p 96 | |||||||||

The Third Battle of Panipat took place on 14 January 1761, at Panipat (Haryana State, India), about 60 miles (95.5 km) north of Delhi. The battle pitted the French-supplied[1] artillery and cavalry of the Marathas against the heavy cavalry and mounted artillery(zamburak and jizail) of the Afghans led by Ahmad Shah Durrani, an ethnic Pashtun, also known as Ahmad Shah Abdali. The battle is considered one of the largest battles fought in the 18th century.[2]

The decline of the Mughal Empire had led to territorial gains for the Maratha Confederacy. Ahmad Shah Abdali, amongst others, was unwilling to allow the Marathas' gains to go unchecked. In 1759, he raised an army from the Pashtun tribes and made several gains against the smaller garrisons. The Marathas, under the command of Sadashivrao Bhau, responded by gathering an army of between 70,000-100,000[3] people with which they ransacked the Mughal capital of Delhi. There followed a series of skirmishes along the banks of the river Yamuna at Karnal and Kunjpura which eventually turned into a two-month-long siege led by Abdali against the Marathas.

The specific site of the battle itself is disputed by historians but most consider it to have occurred somewhere near modern day Kaalaa Aamb and Sanauli Road. The battle lasted for several days and involved over 125,000 men. Protracted skirmishes occurred, with losses and gains on both sides. The forces led by Ahmad Shah Durrani came out victorious after destroying several Maratha flanks. The extent of the losses on both sides is heavily disputed by historians, but it is believed that between 60,000–70,000 were killed in fighting, while numbers of the injured and prisoners taken vary considerably. The result of the battle was the halting of the Maratha advances in the North.

Background

...We have already brought Lahore, Multan, Kashmir and other subahs on this side of Attock under our rule for the most part, and places which have not come under our rule we shall soon bring under us. Ahmad Khan Abdali's son Taimur Sultan and Jahan Khan have been pursued by our troops, and their troops completely looted. Both of them have now reached Peshawar with a few broken troops...we have decided to extend our rule up to Kandahar.

-- Raghoba's letter to the Peshwa, 4 May 1758[4]

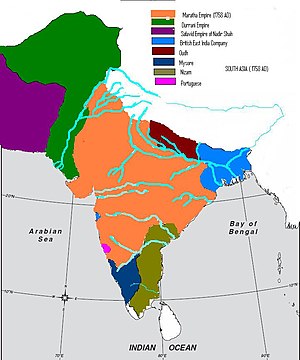

(shown here in yellow)

The Mughal Empire had been in decline since the death of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, in 1707. The decline was accelerated by the invasion of India by Nadir Shah in 1739. Continued rebellions by the Marathas in the south, and the de-facto separation of a number of states (including Hyderabad and Bengal), weakened the state further. Within a few years of Aurangzeb's death, the Marathas had reversed all his territorial gains in the Deccan, and had conquered almost all Mughal territory in central and north India. Mughals had thus become just the titular heads of Delhi. In 1761, they wanted to expand further north and north west, where their path crossed Ahmad Shah Abdali — the ruler of Afghanistan, who had been making raids into Punjab and had appointed his son as its governor.

The Marathas had gained control of a considerable part of India in the intervening period (1707–1757). In 1758, they occupied Delhi, captured Lahore and drove out Timur Shah Durrani,[4] the son and viceroy of the Afghan ruler, Ahmad Shah Abdali. This was the high-water mark of the Maratha expansion, where the boundaries of their empire extended in the north to the Indus and the Himalayas, and in the south nearly to the extremity of the peninsula. This territory was ruled through the Peshwa, who talked of placing his son Vishwasrao on the Mughal throne.[5] However Delhi still remained under the nominal control of Mughals, key Muslim intellectuals including Shah Waliullah and other Muslim clergy in India and Punjab who were alarmed at these developments. In desperation they appealed to Ahmad Shah Abdali, the ruler of Afghanistan, to halt the threat.[6]

Prelude

"The lofty and spacious tents, lined with silks and broadcloths,

were surmounted by large gilded ornaments, conspicuous at a distance... Vast numbers of elephants, flags of all descriptions, the finest horses, magnificently caparisoned ... seemed to be collected from every quarter ... it was an imitation of the more becoming and tasteful array of the Mughuls in the zenith of their glory."

-- Grant Duff, describing the Maratha army[7]

Ahmad Shah Durrani (Ahmad Shah Abdali) angered by the news from his son and his allies was unwilling to allow the Marathas spread go unchecked. By the end of 1759, Abdali with his Afghan (Pashtun) tribes, and his Rohilla ally Najib Khan had reached Lahore as well as Delhi and defeated the smaller enemy garrisons. Ahmed Shah, at this point, withdrew his army to Anupshahr, on the frontier of the Rohilla country, where he successfully convinced the Nawab of Oudh Shuja-ud-Daula to join his alliance against the Marathas.

This in spite of the Marathas time and again helping and showing sympathy towards Shuja-ud-daula. The Nawab’s mother was of the opinion that he should join the Marathas. The Marathas had helped Safdarjung (father of Shuja) in defeating Rohillas in Farrukhabad. However, Shuja was very much ill-treated in the Abdali camp. Abdali was a Sunni Muslim and Shuja was a Shia Muslim.[8]

The Marathas under Sadashivrao Bhau (referred to as the Bhau or Bhao in sources) responded to the news of the Afghans' return to North India by raising a big army, and they marched North. Bhau's force was bolstered by some Maratha forces under Holkar, Scindia, Gaikwad and Govind Pant Bundela. Suraj Mal of Bharatpur also had joined Bhausaheb but then left midway. This combined army of over 100,000 regular troops captured the Mughal capital, Delhi, from an Afghan garrison in December 1759.[9] As Delhi was reduced to ashes due to many invasions and there being acute shortage of supplies in the Maratha camp, Bhau ordered the sacking of the already depopulated city.[10] He is said to have planned to place his nephew and the Peshwa's son, Vishwasrao, on the Mughal throne. The Jats (with the exception of Ala Singh, the first Maharaja of Patiala), did not support the Marathas. Their withdrawal from the ensuing battle was to play a crucial role in its result. The Sikhs, did not support either side and decided to sitback and see what would happen. The exception was Ala Singh of Patiala, who sided with the afghans and was actually being granted and crowned the first Sikh Maharajah despite the Sikh holy temple being destroyed by the Afghans.[11]

Initial skirmishes

With both sides poised for battle there followed much manoeuvring, with skirmishes between the two armies fought at Karnal and Kunjpura. Kunjpura, on the banks of the Yamuna River sixty miles to the north of Delhi, was stormed by the Marathas and the whole Afghan garrison was killed or enslaved.[12] Marathas achieved a rather easy victory at Kunjpura although there was a substantial army posted there. Noted generals of Abdali were killed. Ahmad Shah was encamped on the left bank of the Yamuna River, which was swollen by rains, and so was powerless to aid the garrison. The massacre of the Kunjpura garrison, within the sight of the Durrani camp, exasperated him to such an extent that he ordered crossing of the river at all costs.[13] Ahmed Shah and his allies on 17 October 1760, broke up from Shahdara, marching South. Taking a calculated risk, Abdali plunged into the river, followed by his bodyguards and the troops. Between 23 and 25 October, they were able to cross at Baghpat(a small town about twenty-four miles up the river), as a man from the village in exchange of money, showed Abdali a way through Yamuna, from where the river could be crossed,[8] unopposed by the Marathas who were still preoccupied with the sacking of Kunjpura.

Bhauaheb had stationed 4-5 military posts (which were away from one another) of about 1,000-1,500 men each and had ordered them to not allow Abdali to cross Yamuna. But, as Abdali was marching to the south of Panipat to block the road leading to Delhi, these military posts one-by-one saw that Abdali had crossed Yamuna. Thus, not withstanding their frustration they attacked the Afghan army. But due to the massive force of Abdali they couldn’t stop him. However, many Afghans were slain by the Marathas. One of the generals of Abdali was also killed.[8]

After the Marathas failed to prevent Abdali's forces crossing the Yamuna river, they set up defensive works in the ground near Panipat, thereby blocking his access back to Afghanistan just as his forces blocked theirs to the south. However, on the afternoon of 26 October, Ahmad Shah's advance guard reached Sambalka, about half-way between Sonepat and Panipat, where they encountered the vanguard of the Marathas. A fierce skirmish ensued, in which the Afghans lost a thousand men, killed and wounded, but drove back the Marathas to their main body, which kept on retreating slowly for several days. This led to the partial encirclement of the Maratha army. In skirmishes that followed, Govind Pant Bundela, with 10,000 light cavalry who weren’t formally trained as soldiers was on a foraging mission. He was surprised when he was with about 500 of his men and slain by an Afghan force near Meerut.[8] This in turn was followed by the loss of another 2,000 Maratha soldiers, who were delivering salaries for the soldiers from Delhi. This completed the encirclement as Ahmad Shah had cut off the Maratha Army's supply lines.[14]

With supplies and stores dwindling, tensions also rose in the Maratha camp as the mercenaries in the Maratha army were complaining of lack of pay. Initially the Marathas then moved in almost 150 pieces of modern long-range French-made artillery. With a range of several kilometres, these guns were some of the best of the times. Their plan was to lure the Afghan army to confront them while they had close artillery support.[14]

However, Bhausaheb sheltered and let go 4,000 injured Rohillas who were taken as prisoners by the Marathas in their win in Kunjpura.[8]

Siege of Panipat

During the next two months of the siege constant skirmishes and duels took place between parties and individual champions upon either side. In one of these Najib lost 3,000 of his Rohillas, and was very near killed himself but ran away. Facing a seeming stalemate Abdali decided to seek terms, which Bhau was willing. However Najib Khan delayed any chance of an agreement with an appeal on religious grounds and threw doubt into whether the Marathas would honour any agreement.[7]

After the Marathas moved from Kunjpura to Panipat, Diler Khan Marwat with his father Alam Khan Marwat and a force of 2500 Pashtuns attacked and took control of Kunjpura where there was a Maratha garrison of about 700-800 soldiers. At that time, Atai Khan Baluch, son of the Wazir of Abdali, came from Afghanistan with 10,000 cavalry and cut off the supplies provided by Alasingh Jat. He ordered Atai Khan to cut off the supplies from Ala Singh Jat of Punjab and to destroy the villages providing supplies to the Marathas.[8]

The Marathas at Panipat were surrounded by Abdali in the south, Pashtun Tribes (Yousuf Zai, Afridi, Khattak) in the east, Shuja, Atai Khan and others in the north and other Pashtun Tribes (Gandapur, Marwat, Durranis & Kakars) along with Rajputs in the west. Abdali had also ordered Wazir Shaha Wali Khan Afridi and others to keep a watch in the thorny jungles surrounding Panipat. Thus, all supplies lines were cut.[8]

The Marathas’ difficulty in securing supplies worsened as the local population became hostile to them. As after becoming increasingly desperate for supplies, they had pillaged the surrounding areas.

While Sadashivrao Bhau was still eager to make terms, a message was received from the Peshawa insisting on going to war and promising that reinforcements were under way. Unable to continue without supplies or wait for the reinforcements any longer, Bhau decided to break the siege. His plan was to pulverise the enemy formations with cannon fire and not to employ his cavalry until the Afghans were thoroughly softened up. With the Afghans broken, he would move camp in a defensive formation towards Delhi, where they were assured supplies.[7]

Battle

Formations

The Maratha lines began a little to the north of Kala Amb. They had thus blocked the northward path of Abdali's troops and at the same time they themselves were blocked by the latter from the south which was in the direction to Delhi, where they could get badly needed supplies. Bhau, with the Peshwa's son and the household troops, were in the centre. The left wing consisted of the gardis under Ibrahim Khan. Holkar and Sindhia were on the extreme right.[14]

The Maratha line was to be formed up some 12 km across, with the artillery in front, protected by infantry, pikemen, musketeers and bowmen. The cavalry was instructed to wait behind the artillery and bayonet wielding musketeers, ready to be thrown in when control of battlefield had been fully established. Behind this line was another ring of 30,000 young Maratha soldiers who were not battle tested, and then the roughly 30,000 civilians entrained.[14] Many were middle class men, women and children on their pilgrimage to the Hindu holy places and shrines. Behind the civilians was yet another protective infantry line, of young inexperienced soldiers.

On the other side, the Afghans formed a somewhat similar line, probably a few metres to the south of Sanauli road of today. Their left was being formed by Najib, and their right by two brigades of Persian troops. Their left centre was led by the two Viziers, Shuja-ud-daulah with 3,000 soldiers, about 50-60 cannons and Ahmad Shah's Vizier Shah Wali with a choice body of 19,000 mailed Afghan horsemen.[14] The right centre consisted of 15,000 Rohillas, under Hafiz Rahmat and other chiefs of the Rohilla Pathans. Pasand Khan covered the left wing with 5,000 cavalry, Barkurdar Khan and Amir Beg covered the right wing with 3,000 Rohilla cavalry with the choicest Persian horses,[8] long range Musketeers were also present during the battle. In this order the army of Ahmed Shah moved forward, leaving Ahmed Shah at his preferred post in the centre, which was now in rear of the line, from where he could watch and direct the battle.

Early phases

Before dawn, on 14 January 1761, the Maratha troops broke their fast with the last remaining grain in camp, and prepared for combat; coming from their lines with turbans disheveled and turmeric-smeared faces. The Maratha forces emerged from the trenches, pushing the artillery into position on their prearranged lines, some 2 km from the Afghans. Seeing that the battle was on, Ahmad Shah positioned his 60 smooth-bore cannon and opened fire. However, because of the short range of the Afghan weapons and the static nature of the Maratha artillery, the Afghan cannons proved ineffectual.

The initial attack was led by the Maratha left flank under Ibrahim Khan, who in his eagerness to prove his worth; advanced his infantry in formation against the Rohillas and Shah Pasand Khan. The first salvos from the Maratha artillery went over the Afghans' heads and inflicted very little damage. Nevertheless, the first Afghan attack was broken by Maratha bowmen and pikemen, along with some famed Gardi musketeers stationed close to the artillery positions. The second and subsequent salvos were fired at point blank range into the Afghan ranks. The resulting carnage sent the Rohillas reeling back to their lines, leaving the battlefield virtually in the hands of Ibrahim for the next three hours during which the 8,000 Gardi musketeers had killed about 12,000 Rohillas.[8]

In the second phase, Bhau himself led the charge against the left of center Afghan forces, under the Afghan Vizier Shah Wali Khan. The sheer force of the attack nearly broke the Afghan lines, and soldiers started to desert their positions amidst the confusion. Desperately trying to rally his forces, Shah Wali appealed to Shuja ud Daulah for assistance. However, the Nawab did not break from his position, effectively splitting the Afghan Army's center. Despite Bhau's success, the over-enthusiasm of the charge and due to a phenomenon called ‘Dakshinayan’ on that fateful day, the sunlight went directly into the horses' eyes, many of the half starved Maratha horses exhausted long before they had traveled the two kilometers to the Afghan lines; some simply collapsed. Making matters worse was the suffocating odor of the rotting corpses of men and animals left on the field from the fighting of the previous months.[8]

Final phase

In the final phase the Marathas, under Scindia, attacked Najib. However, Najib successfully fought a defensive action keeping Scindia's forces at bay. By this stage at noon it looked as though Bhau would clinch victory for the Marathas once again. The Afghan left flank still held its own under the two; but the centre was cut in two, and the right was almost destroyed. Ahmad Shah had watched the fortunes of the battle from his tent, guarded by the still unbroken forces on his left.

Ahmad Shah sent his body guards to call up his reserves of 15,000 troops from his camp and arranged it as a column in front of his cavalry of musketeers (Qizilbash) and 2,000 swivel mounted shaturnals or cannons on the back of camels.[15] The shaturnals, because of their positioning on camels, could fire an extensive salvo over the heads of their own infantry and at the Maratha cavalry. The Maratha cavalry were unable to withstand the muskets and camel-mounted swivel cannons of the Afghans. They could be fired without the rider having to dismount and were especially effective against fast moving cavalry. He therefore sent 500 of his own body-guards with orders to raise all able-bodied men out of camp, and send them to the front at any cost. He sent 1,500 more, to encounter those who were fleeing, and slay without pity anyone who would not return to the fight. These extra troops, along with 4,000 of his reserve troops, went to support the broken ranks of the Rohillas on the right. The remainder of the reserve, 10,000 strong, were sent to the aid of Shah Wali, still labouring unequally against the Bhao in the centre of the field. These mailed warriors were to charge with the Vizir in close order, and at full gallop. As often as they charged the enemy in front, the chief of the staff and Najib were directed to fall upon either flank.

With their own men in the firing line, the Maratha artillery could not respond to the shathurnals and the cavalry charge. Some 7,000 Maratha cavalry and infantry were killed before the hand to hand fighting began at around 14:00. By 16:00 the tired Maratha infantry began to succumb to the onslaught of attacks from fresh Afghan reserves, protected by armoured leather jackets.

Outflanked

Sadashivrao Bhau, seeing his forward lines dwindling and civilians behind, had not kept any reserves and upon seeing Vishwasrao disappear amongst the fighting felt he had no choice but to come down from his elephant and lead the battle at the head of the troops.[4] Some Maratha soldiers, seeing that their general had disappeared from his elephant, panicked and began to flee. Vishwasrao had already fallen to a shot in the head. Bhau and his loyal bodyguards fought to the end, the Maratha leader having three horses shot out from under him. At this stage Holkar realising the battle was lost broke from the Maratha left flank and retreated.[4]

Abdali had given a part of his army the task to surround and kill the Gardis under Ibrahim Gardi, who were at the leftmost part of the Maratha army. Bhausaheb had ordered Vitthal Vinchurkar (with 1500 cavalry) and Damaji Gaikwad (with 2500 cavalry) to protect the Gardi’s. But seeing the Gardi’s fight, they lost their patience, became over enthusiastic and decided to fight the Rohillas themselves. Thus, they broke the round (circle) i.e. they didn’t follow the idea of round battle and went all out on the Rohillas and the Rohillas then started accurately shooting the rifleless Maratha cavalry which was equipped with swords. This gave opportunity to the Rohillas to encircle the Gardis and outflank the Maratha centre while, Shah Wali pressed on attacking the front. Thus, the Gardis were left defenceless and started falling down one by one.[8]

The Maratha army was routed and fled under the devastating attack. Only 15,000 soldiers managed to reach Gwalior, while the rest including the large numbers of non-combatants were either killed or captured.[4]

The Maratha army had captured some Afghan soldiers earlier during the siege of Kunjpura. Amidst the general melée the slaves revolted. The slaves deliberately spread rumours about the defeat of the Marathas. They started looting the pilgrims.[8] This brought confusion and great consternation to loyal Maratha soldiers, who thought that the enemy had attacked from their rear.

Rout

The Afghans pursued the fleeing Maratha army and the civilians, while the Maratha front lines remained largely intact, with some of their artillery units fighting till sunset. Choosing not to launch a night attack, many escaped that night. Bhau's wife Parvatibai, who was assisting in the administration of the Maratha camp escaped to Pune with her bodyguards.

The Afghan cavalry and pikemen ran wild through the streets of Panipat, killing any Maratha soldier or civilian who offered any resistance. About 6,000 women and children sought shelter with Shuja (ally of Abdali) whose Hindu officers persuaded him to protect them. Shuja had to give Rs.3 lakhs to Barkurdarkhan on the condition that the refugees wouldn’t be harmed. Surajmal Jat of Bharatpur also gave refuge to the Marathas.[8]

Reasons for the outcome

The main reason for the failure of Marathas was that they went to war without good allies. Though their infantry was based on European style contingent and had some of the best French made guns of the times, their artillery was static and lacked mobility against the fast moving Afghan forces.[16]

The Marathas had interfered in the internal affairs of the Rajputana states (present day Rajasthan) and levied heavy taxes and huge fines on them. They had also made huge territorial and monetary claims upon Awadh. Their raids in the Sikh territory had resulted in the loss of trust of Sikh chiefs like Ala Singh and the Jat chiefs. They had, therefore, to fight their enemies alone.

Moreover, the senior Maratha chiefs constantly bickered with one another. Each one of them had ambitions of carving out their independent states and had no interest in fighting against a common enemy.[17] Some of them didn't support the idea of a round battle and wanted to battle using Guerilla tactics charging the enemy head-on.[8]

The Maratha Army was also burdened with 150,000 pilgrims who wished to worship at Hindu places of worship like Mathura, Prayag, Kashi, etc. The pilgrims wanted to go with the army as they would be secure with them.[citation needed][original research?]

Before the battle, the Marathas along with all the horses, elephants and cattles were forced to fast for many days and thus fought the battle of Panipat on an empty stomach. Moreover, it took many more days for the Marathas to reach the North due to the constant halting of pilgrims at the places of worship. If not for these pilgrims, the Marathas would have reached the North in the scheduled number of days and would have been in a better position to face Abdali.[8]

Najib, Shuja and the Rohillas knew North India very well and most of North India had allied with Abdali, thus, it can be said that there wasn't any hostility against Abdali. However, the Afghans too started the battle with some disadvantages, facing a well trained, western equipped Army, that was undefeated and led by a single leader. Ahmad Shah Abdali compensated for this by his use of shaturnals, camels with mobile artillery pieces at his disposal. He was also diplomatic striking up agreements with Hindu leaders, especially the Jats and Rajputs, and former rivals like the Nawab of Awadh appealing to him in the name of religion.[citation needed][original research?]

He also had better intelligence on the movements of his enemy, which played a crucial role in his encirclement of the enemy army. Abdali had also kept a fresh force in reserve, which he used when his existing force was being slaughtered.[citation needed][original research?]

Aftermath

The body of Vishwasrao and Bhau were recovered by the Afghans and under Ahmad Shah's personal direction were cremated according to Hindu custom. Bhau's wife Parvatibai was saved by Holkar as per the directions of Bhau and eventually they returned to Pune.

Peshwa Balaji Baji Rao, uninformed about the state of his army, was crossing the Narmada with reinforcements when a tired Charkara arrived with a cryptic message "Two pearls have been dissolved, 27 gold coins have been lost and of the silver and copper the total cannot be cast up". The Peshwa never recovered from the shock of the total debacle at Panipat. He returned to Pune and died a broken man in a temple on Paravati Hill.[4]

Jankoji Scindia was taken prisoner and executed at the instigation of Najib. Ibrahim Khan Gardi was tortured and executed at the hands of enraged Afghan soldiers.[18] The Marathas never fully recovered from the loss at Panipat, however they remained the predominant military power in India and managed to retake Delhi 10 years later. However, their claim over all of India ended with the three Anglo-Maratha Wars, almost 50 years after Panipat.[19]

The Jats under Suraj Mal benefited significantly from not participating in the battle of Panipat. They provided considerable assistance to the Maratha soldiers and civilians who escaped the fighting. Suraj Mal himself was killed in battle against Najib-ud-Daula in 1763.[20][21] Ahmad Shah's victory left him, in the short term, the undisputed master of North India. However, his alliance quickly unravelled amidst squabbles between his generals and other princes, the increasing restlessness of his soldiers over pay, the increasing Indian heat and arrival of the news that Marathas had organised another 100,000 men in the south to avenge their loss and to rescue the captured prisoners. Before departing, he ordered the Indian chiefs, through a Royal Firman (order) (including Clive of India), to recognise Shah Alam II as Emperor.[22]

Ahmad Shah also appointed Najib-ud-Daula as ostensible regent to the Mughal Emperor. In addition, Najib and Munir-ud-daulah agreed to pay to Abdali, on behalf of the Mughal King, an annual tribute of four million rupees.[22] This was to be Ahmad Shah's final major expedition to North India, as he became increasingly pre-occupied with the increasingly successful rebellions by the Sikhs.[23]

Shah Shuja was to regret his decision to join the Afghan forces. In time, his forces became embroiled in clashes between the orthodox Sunni Afghan's and his own Shia followers. He is alleged to have later secretly sent letters to Bhausaheb through his spies regretting his decision to join Abdali.[8]

After the battle of Panipat the services of the Rohillas were rewarded by the grants of Shikohabad to Nawab Faiz-ullah Khan and of Jalesar and Firozabad to Nawab Sadullah Khan. Najib Khan proved to be an effective ruler in that time. However, after his death in 1770, the Rohillas were defeated by the British East India Company.[24][25]

However the Marathas soon stabilized the situation and control over North Indian political scene. According to the eminent historian Sardesai the situation did not change much. The victory did not fetch any benefit to Abdali. He wrote to the Peshwa stating that they had no reason to be enemies and that he was sorry since Peshwa's son and brother got killed. He even added that Peshwa could continue controlling Delhi politics and let him (Abdali) have the Punjab province.

Legacy

The Third Battle of Panipat saw an enormous number of casualties and deaths in a single day of battle. It was the last major battle between indigenous South Asian military powers, until the creation of Pakistan in 1947.

To save their kingdom, the Mughals once again changed sides and welcomed the Afghans to Delhi. The Mughals remained in nominal control over small areas of India, but were never a force again. The empire officially ended in 1857 when its last emperor, Bahadur Shah II, was accused of being involved in the Sepoy Mutiny and exiled.

The Marathas' expansion was stopped in the battle, and soon broke into infighting within their empire. They never regained any unity. They recovered their position under the next Peshwa Madhavrao I and by 1772 were back in control of the north, finally occupying Delhi. However, after the death of Madhavrao, due to infighting and increasing pressure from the British, their claims to empire only officially ended in 1818 after three wars with the British.

Meanwhile the Sikhs, the original reason Ahmad invaded, were left largely untouched by the battle. They soon retook Lahore. When Ahmad Shah returned in March 1764 he was forced to break off his siege after only two weeks due to rebellion in Afghanistan. He returned again in 1767, but was unable to win any decisive battle. With his own troops arguing over a lack of pay, he eventually abandoned the district to the Sikhs, who remained in control until 1849.

The Marathi term "Sankrant Kosalali"(सक्रांत कोसळली), meaning "Sankranti has befallen us", is said to have originated from the events of the battle.[26] There are some verbs in Marathi language related to this loss as "Panipat zale"(पानिपत झाले)[a major loss has happened] This verb is even today used in Marathi language. A common pun is "Aamchaa Vishwaas Panipataat gela" (आमचा विश्वास पानीपतात गेला) [we lost our own (Vishwas) faith since Panipat]. Many historians, including British historians of the time, have argued that had it not been for the weakening of the Maratha power at Panipat, the British might never have had a strong foothold in India.

The battle proved the inspiration for Rudyard Kipling's poem "With Scindia to Delhi".

It is however also remembered as a scene of valour on both sides - Sadashiv Bhau was found with almost twenty dead Afghans around him. Santaji Wagh's corpse was found with over forty mortal wounds. Vishwa Rao, the Peshwas son's bravery was acknowledged even by the Afghans.[27] Yashwantrao Pawar also fought with great courage killing many Afghans. He killed Ataikhan, the grandson of the Wazir of Abdali by climbing onto the latter’s elephant.[8]. On the Afghan side, there were many heroes, still remembered for their bravery in the Afghan folklore. Rohilas showed exemplary valour and rallied after having been routed earlier to inflict the final blows of the battle.

The strength of Afghan military prowess was to both inspire hope in many orthodox Muslims, Mughal royalists and fear in the British. However the real truth of so many battle hardened Afghans killed in the struggle with the Marathas never allowed them to dream of controlling the Mughal Empire realistically again. On the other side, Marathas, possibly one of the only two real Indian military powers left capable of challenging the British were fatally weakened by the defeat and could not mount a serious challenge in the Anglo-Maratha wars 50 years later.

See also

Notes and references

- ^ "Maratha Confederacy". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- ^ Black, Jeremy (2002) Warfare In The Eighteenth Century (Cassell'S History Of Warfare) (Paperback - 25 Jul 2002)ISBN 0304362123

- ^ Abdali. Retrieved 14 January 2010

- ^ a b c d e f Roy, Kaushik. India's Historic Battles: From Alexander the Great to Kargil. Permanent Black, India. pp. 80–1. ISBN 978-8178241098.

- ^ Elphinstone, Mountstuart (1841). History of India. John Murray, Albermarle Street. p. 276.

- ^ "Shah Wali Ullah (1703-1762)". Storyofpakistan.com. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- ^ a b c Keene, H.G. (1887). Part I, Chapter VI: The Fall of the Moghul Empire of Hindustan.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Patil, Vishwas. Panipat. Cite error: The named reference "Vishwas Patil" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Robinson, Howard (1922). "Mogul Empire". The Development of the British Empire. Houghton Mifflin. p. 91.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Agrawal, Ashvini (1983). "Events leading to the Battle of Panipat". Studies in Mughal History. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 26. ISBN 8120823265.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Sinha, Narendra Krishna (2008) [1973]. "Ala Singh". Rise of the Sikh power. University of Michigan. p. 37.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Also see Syed Altaf Ali Brelvi, Life of Hafiz Rahmat Khan, pp. 108–9.

- ^ Lateef, S M. “History of the Punjab”, p. 235,.

- ^ a b c d e Rawlinson, H. G. (1926). An Account Of The Last Battle of Panipat. Oxford University Press.

- ^ War Elephants Written by Konstantin Nossov, Illustrated by Peter Dennis Format: Trade Paperback ISBN 9781846032684

- ^ Chandra, Satish (2004). "Later Mughals". Medieval India: From Sultanate to the Mughals Part - II. Har-Anand. ISBN 8124110662.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ James Rapson, Edward. The Cambridge History of India : The Mughul period, planned by W. Haig. Vol. 4. Cambridge University Press. p. 448.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pradeep Barua, "Military Developments in India, 1750-1850" Vol. 58, No. 4 (1994), p. 616

- ^ Jadunath Sarkar Fall of the Mughal Empire Sangam Books 1992 P 235 ISBN 0861317491

- ^ K.R. Qunungo, History of the Jats, Ed. Vir Singh, Delhi, 2003, pp. 202-205

- ^ G.C.Dwivedi, The Jats, Their role in the Mughal Empire, Ed Dr Vir Singh, Delhi, 2003, p. 253

- ^ a b Mohsini, Haroon. "Invasions of Ahmad Shah Abdali". afghan-network.net. Retrieved 13 August 2007.

- ^ MacLeod, John, The History of India, 2002, Greenwood Press

- ^ Strachey, John. Hastings and the Rohilla War. BR Publishing. p. 374. ISBN 8170480051.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Strachey, p. 380

- ^ "Land Maratha". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009.

- ^ Rao, S. "Walking the streets of Panipat". Indian Oil News. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

Further reading

- Britannica "Panipat, Battles of" (2007) Retrieved 24 May 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- T S Shejwalkar, Panipat 1761 Deccan College Monograph Series. I., Pune (1946)

- H. G. Rawlinson, An Account Of The Last Battle of Panipat and of the Events Leading To It, Hesperides Press (2006) ISBN 1406726251

- Vishwas Patil, Panipat" - a novel based on the 3rd battle of Panipat, Venus (1990)

External links

- Panipat War memorial Pictures

- With Scindia to Delhi 1890 Rudyard Kipling

- The Maratha community

- The Saraswathi Mahal Library at Thanjavur

- District Panipat

- Was late mediaeval India ready for a Revolution in Military Affairs?- Part II Airavat Singh

- Invasions of Ahmad Shah Abdali

- Detailed genealogy of the Durrani dynasty

- Famous Diamonds: The Koh-I-Noor

- Rampur

- Historical maps of India in the 18th century