Christian Science: Difference between revisions

SlimVirgin (talk | contribs) m typo |

Simplywater (talk | contribs) other Tremont temple account isn't complete and this has non cs scholarship |

||

| Line 366: | Line 366: | ||

*Theologian Charles S. Braden accused Eddy of having plagiarized an essay by [[Lindley Murray]] (1745–1826), and wrote that another essay, "Taking Offense," was printed as one of Eddy's when it had first been published anonymously by an obscure newspaper; see [http://www.jstor.org/stable/1384067 Braden 1967], p. 296. |

*Theologian Charles S. Braden accused Eddy of having plagiarized an essay by [[Lindley Murray]] (1745–1826), and wrote that another essay, "Taking Offense," was printed as one of Eddy's when it had first been published anonymously by an obscure newspaper; see [http://www.jstor.org/stable/1384067 Braden 1967], p. 296. |

||

*Gardner 1993, pp. 145–154, listed other writers whose words he said she had used without attribution, including [[John Ruskin]] (1819–1900), [[Thomas Carlyle]] (1795–1881), [[Charles Kingsley]] (1819–1875), [[Henri-Frédéric Amiel]] (1821–1881), and [[Hugh Blair]] (1718–1800).</ref> |

*Gardner 1993, pp. 145–154, listed other writers whose words he said she had used without attribution, including [[John Ruskin]] (1819–1900), [[Thomas Carlyle]] (1795–1881), [[Charles Kingsley]] (1819–1875), [[Henri-Frédéric Amiel]] (1821–1881), and [[Hugh Blair]] (1718–1800).</ref> |

||

====''Eddy's Debt to Wesley and Tremont Temple''=== |

|||

The 19th century religious landscape was complex making it difficult to categorize the healing movements of the time.<ref>Curtis; Faith in the Great Physician, John Hopkins University Press, (pg.100) </ref> The explosion of [[Protestant]] divine healing movements (also referred to as faith healing, faith cure, or simply healing movement) was non-denominational including several Protestant denominations. It's roots lying in the Primative [[Methodists]] inspired by "A Plain Account of Christian Perfection" written by [[John Wesley]]<ref>Porterfield, Amanda; Healing in the History of Christianity, Oxford University Press p. 166,</ref>.<ref>Mix,Sarah; Faith, Cures and Answered Prayers Syracuse University Press (This book, with an introduction by Rosemary Gooden is edited by Amanda Porterfield and Mary Farrell Bednarowski and part of the series Women and Gender in North American Religions), pp xxiv</ref>the minister who founded Methodism. Christian Science needs to be viewed within the context of the Holiness movement both because of the access this movement gave to women<ref>Melton; Women's Leadership in Marginal Religions, Oxford University Press (p.91:The emergence and importance of Emma Curtis Hopkins (as well as other nineteenth-century female religious leaders such as Helena P. Blavatsky, Ellen G. White, and Mary Baker Eddy) cannot be understood apart from the appreciation of the tremendous opening of new space for women in the religious community created by the holiness movement, and the atmosphere of longing and expectation it generated among women in other religious groupings.)</ref> and because Eddy was “an heir to Wesley’s understanding of Christian Healing.”<ref>Porterfield, pp 178-180:Another heir to Wesley's understanding of Christian healing, Mary Baker Eddy (1821-1910) also emphasized the power of Christ's Spirit in effecting cures. For Eddy, the "El Dorado of Christianity" was Christian Science, which "recognizes only the divine control of Spirit, in which Soul is our master, and material sense and human will have no place."</ref> |

|||

John Wesley ‘emphasized the importance of subjective experience of the Spirit’ and wrote “I believe that God now hears and answers prayer even beyond the ordinary course of nature.” <ref>Porterfied p. 166,</ref> Although he healed, spiritual healing was not his focus. In the 1830’s American Methodist lay woman, Phoebe Palmer “reformulated” John Wesley’s teaching. <ref>Mix, pp. xix-xxiv</ref> Palmer argued that ‘perfection’ or ‘holiness’ didn’t need to be a process but could be immediate. Physical healing of the body was evidence of instantaneous sanctification. Ethan O. Allen a Methodist layman who believed that purification from sin would eradicate sickness, became the first evangelist to make healing his ministry. Charles Cullis, an Episcopal layman and homeopathic physician in Boston advocated that complete salvation included both spiritual and physical healing.<ref>Mix, pp xxiv</ref> |

|||

Mary Baker Eddy is included in the list of Protestant reformers “who objected to the notion that God ordained bodily suffering”. <ref> Porterfield, Amanda; pp 178-180</ref>. “Faith cure and Christian Science did seem to propose a similar hermeneutics of healing”. <ref>Curtis, (p. 100)</ref> and Christian Science had in common the beliefs of nineteenth century evangelical [[Protestantism]] which included a strong belief in the spiritual power of healing.<ref>Mix, (page xvl)</ref><ref>Porterfield, (p. 3):When I embarked on this book, I did not anticipate the extent to which I would come to see Christianity as a religion of healing.(p.5)Within the Protestant tradition Methodists provide the central narrative thread, since they and their heirs in the Adventist, Holiness, and Pentecostal movements embraced religious experience in greater numbers and with greater enthusiasm than most other Protestants. As Protestants embrace new religious movements-Spiritualism, Christian Science, New Thought, and Theosophy that wrestle directly with matters of experience and explanation, they in turn are woven into the narrative. </ref><ref>Curtis, (p. 19):While I do evoke Chritian Science, Spiritualism, and other healing movements at various points throughout this work, my aim in doing so is to illumine the rich and variegated history of evangelical faith cure.</ref> All of these healing movements "involved rejecting a materialistic view of the body" and giving up the ethic of passive resignation.<ref>Curtis, (p. 18)</ref> Clergy tried to make a distinction between Christian Science and the divine healing movement. Still in the eyes of the public, they seemed the same. <ref>Curtis, (p.58-59)</ref> |

|||

In 1885 Methodist minister and Boston University Professor [[Luther T. Townsend]], an adversary among others, of the divine healing movement and mind cure movement, wrote a treatise called “Faith Work, Christian Science and Other Cures”. In that treatise Townsend highlighted the similarities between the [[divine healing movement]] and Christian Science saying both were the response of the operation of ordinary ‘physical laws’ without intervention or the miraculous power of God. |

|||

Around the same time A.J. Gordon a proponent of Christian perfection and involved in the divine healing movement, wanted to distance his movement from Christian Science.<ref>Curtis, Heather, Faith and the Great Physician,John Hopkins University Press pg 22</ref> A letter, written by Gordon was sent to the popular Evangelical Boston lecturer Joseph Cook,<ref>Pointer, Stephen, Josephy Cook, Boston Lecturer and Evangilical Apoligist.</ref> and in February 1885 at the Tremont Temple Monday lectures, to a crowd of 3,000, the letter was read by Cook. Through the letter Gordon attacked Christian Science saying it was a 'false religion'.<ref>Bendroth, Margaret, Fundamentalists in the City, Conflict and Division in Boston's churches, Oxford Press p.23</ref> |

|||

He also said through Cook that “it was anti-christian in it’s no personal Deity, no personal devil, no personal man, no forgiveness of sin, no such thing as sin, no sacrificial atonement, no intercesary prayer”.<ref>Mix, Mix, p xxxvi</ref> |

|||

Hearing about the attack, Mary Baker Eddy wrote Cook and asked for the opportunity to reply. He agreed and gave her 10 minitues to defend her system of healing as Christian at one of the Monday Tremont Temple lectures<ref>Mix, p xxxvii</ref> |

|||

On March 16, 1885 at Tremont Temple, to a crowed of 3,000<ref>Bendroth, Margaret, Fundamentalists in the City; Conflict and Division in Boston's Churches, Oxford University Press, (p </ref> in an extemporaneous reply, Eddy asked |

|||

“Do not the reverend gentlemen demand the right to explain their creed?”<ref>Eddy, Mary, Defense of Christian Science Against Joseph Cook and J. Gordon's religious Ban, Kessinger Publishing p.</ref> She then commenced to explain her doctrines on atonement, God, sin and the trinity. She said |

|||

:::Do I believe in a personal God? |

|||

:::I believe in God as the Supreme Being. I know not what the person of omnipotence and ominipresence is, or :::what the infinite includes; therefore, I worship that of which I can conceive, first as a loving Father and Mother; then as thought ascends the scale of being to diviner consciousness, God becomes to me, as to the apostle who declared it, “God is Love”, - divine Principle, - which I worship; and ‘after the manner of my fathers, so worship I God.”<ref>Mix, pg xxxviii</ref> |

|||

In reply to attacks on her doctrine of atonement, Eddy replied that ‘this becomes more to me since it includes man’s redemption from sickness as well as from sin. I reverence and adore Christ as never before.” <ref>Gooden, pg xxxviii</ref> |

|||

Some argue that Eddy’s doctrine of atonement, which includes both salvation from sin and suffering was the same doctrine of the faith cure movement and a result of the Protestant healing movement of the 1830's <ref>Mix, page xxxviii</ref> <ref>Stillson, Judah. The History and Philosophy of Metaphysical Movements page 281</ref> Although having "obvious ties to Christian tradition",<ref>Moore, Religious Outsiders and the Making of Americans, Oxford University Press page 107</ref> many theologians feel a deeper understanding of the theology places it outside traditional Christian theology. |

|||

Today Christian Scientists distance themselves from 20th century faith cure movements who have have “ridgely proscriptive views of medicine” . <ref>Palmer, Luanne; When Parents say No: Religious and Cultural Influences on Pediatric HealthCare Treatment, Sigma Theta Tau International Publishing pg 81</ref>. |

|||

{{anchor|MAM}} |

{{anchor|MAM}} |

||

Revision as of 21:23, 27 March 2014

| Christian Science | |

|---|---|

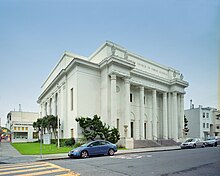

The First Church of Christ, Scientist Boston, Massachusetts | |

| Founder | Mary Baker Eddy (1821–1910) |

| Mother Church | The First Church of Christ, Scientist, Back Bay, Boston |

| Key texts | Mary Baker Eddy, Science and Health With Key to the Scriptures and Manual of the Mother Church |

| Membership | 100,000–400,000 worldwide, as of 2008[1] |

| Number of churches | 1,100 in the United States, 600 elsewhere, as of 2010[2] |

| Key beliefs | Scientific statement of being;[3] "Basic teachings", Church of Christ, Scientist |

| Website | |

| christianscience.com | |

Christian Science is a set of beliefs and practices belonging to the metaphysical family of new religious movements.[4] It was developed in the United States by Mary Baker Eddy (1821–1910) after she experienced what she said was a miraculous recovery from a fall. She subsequently wrote Science and Health (1875), which argued that sickness is an illusion that can be corrected by prayer alone. The book became Christian Science's central text along with the Bible; by 2001, according to the church, it had sold ten million copies in 16 languages.[5]

Eddy and around 25 followers were granted a charter in 1879 to found the Church of Christ (Scientist), and in 1894 the Mother Church, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, was built in Boston, Massachusetts.[6] Eddy's ideas proved popular: during the first decades of the 20th century Christian Science became the fastest growing American religion. A census in 1936 counted nearly 270,000 Scientists in the United States, a figure that had declined by the 1990s to just over 100,000; a church estimate in 2008 placed the global membership at 400,000.[7] The religion is known for the Christian Science Monitor, which won seven Pulitzer Prizes between 1950 and 2002, and for its Reading Rooms, which are open to the public in around 1,200 cities.[8]

Christian Scientists see their religion as consistent with Christian theology, despite key differences.[9] In particular they subscribe to a radical form of philosophical idealism, believing that reality is purely spiritual and the material world an illusion. This includes the view that disease is a spiritual rather than physical disorder, that there is no death, and that the sick should be treated, not by medicine, but by a form of prayer that seeks to correct the beliefs responsible for the illusion of ill health.[10]

The church does not require that Christian Scientists avoid all medicine – adherents use dentists, optometrists, obstetricians, physicians for broken bones, and vaccination when required by law – but maintains that Christian Science prayer is most effective when not combined with medical care.[11] Between the 1880s and 1990s the avoidance of medical treatment and vaccination led to the deaths of several adherents and their children; parents and others were prosecuted for manslaughter or neglect, and in a few cases convicted.[12]

Background and theology

Metaphysical–Christian Science–New Thought family

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Christian Science |

|---|

|

| Part of a series of articles on |

| New Thought |

|---|

Two periods of Protestant Christian revival known as the Second and Third Great Awakening (c. 1800–1830 and 1850–1900) nurtured a proliferation of religious movements in the United States, including Adventists, Jehovah's Witnesses, Latter Day Saints, Spiritualists, Swedenborgians, Theosophists, and the metaphysical family.[13]

The metaphysical family consists of several groups, including Christian Science, that were known as the mind-cure, mental-cure, or mental-healing movement, and from the mid-1890s as New Thought (though Christian Science distinguished itself from the latter). The movement emphasized the centrality of the mental world (what it called the "metaphysical"), rather than the material, and in particular saw the mind as the key to physical health.[4] Eddy several times referred to Christian Science as "Metaphysical Science" and "Metaphysical Healing."[14] There was keen interest in alternatives to medicine, such as homeopathy, hydropathy, mesmerism and the relationship between mind, body and diet, in large measure because medical practice was crude and frightening, but also in reaction to the idea that suffering was something to be endured as a test or punishment from God.[15]

The mind-cure movement traced its roots to the work of New England "mental healer" Phineas Parkhurst Quimby (1802–1866), whose motto was "the truth is the cure" (persuade the patient that she is not ill and she will recover); Eddy was a patient of Quimby's and was accused of having founded Christian Science on the basis of his unpublished manuscripts.[16] William James (1842–1910) saw in mind-cure traces of spiritism, Hinduism, the subjective idealism of George Berkeley (1685–1753) and the transcendentalism of Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882). The point above all was to maintain a cheerful attitude; James described the mind-cure literature as "moonstruck with optimism."[17]

New Thought and Christian Science adherents believed they were applying newly discovered spiritual laws scientifically; Philip Jenkins wrote that they saw themselves at the "apex of modern thinking."[18] They differed in that Eddy's philosophy was not dualist. She did not argue merely for the primacy of mind, but dismissed the material world entirely as an illusion; reality for Eddy was purely spiritual.[19] She taught that the mind (or what she called "mortal mind") cannot cure disease, because disease is the mind's mistake and mind cannot cure what it has caused. What heals, she argued, is "not one mind acting upon another mind ... not the transference of human images of thought to other minds," but Divine Mind.[20]

Christian Science theology

Eddy regarded Christian Science as a return to early Christianity and its "lost element of healing," and saw Science and Health as an inspired text and a kind of second coming.[21] At the core of her theology is the idea that God's creation is entirely good, that the material world, including evil, sickness and death, are illusions, and that humankind, as an idea of God or Mind, is perfect; the limitations and flaws of "mortal man" are simply humankind's mistaken view of itself.[22] Her radical idealism is summed up by her "scientific statement of being," which she called the "first plank in the platform of Christian Science": "There is no life, truth, intelligence, nor substance in matter. All is infinite Mind and its infinite manifestation."[3] For Christian Scientists, the spiritualization of thought that comes with the acceptance of this has the power to heal.[23]

"[T]here is no person to be healed, no material body, no patient, no matter, no illness, no one to heal, no substance, no person, no thing and no place that needs to be influenced. This is what the practitioner must first be clear about."

— Frank Prinz-Wondollek,

Christian Science practitioner, 2011[24]

Christian Science practitioners are Scientists who, for a fee, offer a special kind of prayer to address ill health or any other problem a patient might have. There is no appeal to a personal god, no supplication; the process involves the practitioner engaging, alone (known as "absent treatment), in a silent rhetorical argument to reaffirm to herself the unreality of matter. She might also suggest that the patient read passages from Science and Health. In the view of Christian Science this process connects the patient, as a spiritual being, to Divine Mind; historian of religion Amanda Porterfield describes it in terms of an "invisible spiritual force that stimulates healing."[25]

Christian Science leaders see their religion as Christian and reject any identification with the New Thought movement; Eddy herself was strongly influenced by her Congregationalist upbringing.[26] There are nevertheless key differences between Christian Science theology and that of traditional Christianity. Eddy redefined the Christian vocabulary, leading to very different views of the Trinity, creation, divinity of Jesus, atonement, resurrection, heaven and hell.[9]

Eddy saw God not as a person, but as "incorporeal, divine, supreme, infinite Mind, Spirit, Soul, Principle, Life, Truth, Love."[27] (In referring to God as "All-in-all" she denied that she had embraced pantheism, but that was nevertheless how the clergy interpreted it.)[28] She distinguished between Jesus the man and the concept of Christ; Christ was a quality rather than an identity, a synonym for Truth.[29] She regarded Jesus as the first person fully to manifest Divine Mind, a template for other human beings; Eddy called him a Christian Scientist and a "Way-shower" between humanity and God. His death she regarded as an illusion like any other.[30] A person who seems to die simply adjusts to a level of consciousness inaccessible to the living.[31]

The Holy Ghost is "Divine Science" or Christian Science, and heaven and hell are states of mind.[32] Eddy also reinterpreted the Lord's Prayer: "Our Father–Mother God, all-harmonious."[33] In 1907 Mark Twain (1835–1910) described the appeal of the new religion:

She has delivered to them a religion which has revolutionized their lives, banished the glooms that shadowed them, and filled them and flooded them with sunshine and gladness and peace; a religion which has no hell; a religion whose heaven is not put off to another time, with a break and a gulf between, but begins here and now, and melts into eternity as fancies of the waking day melt into the dreams of sleep.

They believe it is a Christianity that is in the New Testament; that it has always been there, that in the drift of ages it was lost through disuse and neglect, and that this benefactor has found it and given it back to men, turning the night of life into day, its terrors into myths, its lamentations into songs of emancipation and rejoicing.[34]

Eddy's view of Science and Health as inspired by God represented a challenge to the Bible's authority, in the opinion of the more conservative of the Protestant clergy.[35] "Eddyism," as it was known, was regularly referred to as a cult; one of the first uses of the modern sense of the word cult was in Anti-Christian Cults (1898) by A. H. Barrington, a book about Spiritualism, Theosophy and Christian Science.[36] Some ministers interpreted Christian Science as gnosticism, the idea (regarded by Christians as heretical) that the material world is the result of a mistake on the part of a supreme being and the work of a demiurge.[37] Others defended the new religion's rejection of materialism. In a few cases Christian Scientists saw themselves expelled from Christian congregations, but for the most part ministers worried that their parishioners were crossing over. The Boston correspondent of the London Times wrote in May 1885: "Scores of the most valued church members are joining the Christian Scientist branch of the metaphysical organization, and it has thus far been impossible to check the defection."[38]

History

Birth

Mary Baker Eddy

Christian Science | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mary Baker Eddy in the 1850s, the earliest known photograph of her[39] | |||||||||||||

| Born | Mary Morse Baker July 16, 1821 | ||||||||||||

| Died | December 3, 1910 (aged 89) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Mary Baker Eddy was born Mary Morse Baker on a farm in Bow, New Hampshire, the youngest of six children. The family were Protestant Congregationalists; her father, Mark Baker, was a deeply religious man who would lead the family in lengthy prayer every morning and evening.[43] In common with most women at the time, she was given little formal education, but by some accounts she read widely at home.[44]

Eddy experienced protracted ill health from childhood, with conditions she described as chronic indigestion and spinal inflammation, and established a pattern of appearing to be seriously ill, even losing consciousness, then quickly recovering.[45] The literary critic Harold Bloom described her as "an extraordinary wreck, a monumental hysteric of classical dimensions, indeed a kind of anthology of nineteenth-century nervous ailments."[46] McClure's magazine wrote in 1907, in a series of highly critical articles: "Nothing had the power of exciting Mark Baker like one of Mary's 'fits,' as they were called. His neighbors ... remember him as he went to fetch Dr. Ladd, how he lashed his horses down the hill, standing upright in his wagon and shouting in his tremendous voice: 'Mary is dying!'"[47]

Christian Scientists regard this criticism as inaccurate and sexist, an attack (typical of that period) on the sanity of a woman who was challenging powerful male interests. Eddy was a target of this, they argue, because she stood against the hegemony of the clergy and medical establishment.[48]

Eddy's first husband died shortly before her 23rd birthday, six months after they married and three months before the birth of their son, leaving her penniless; as a result of her poor health she lost custody of the boy when he was four, although sources differ as to whether she could have prevented this.[49] Her second husband, who left her after 13 years of marriage, promised to become the child's legal guardian – per the legal doctrine of coverture, women at that time in the United States could not be their own children's guardians – but it is unclear whether he did, and Eddy lost contact with her son until he was in his thirties. Her third husband, Asa Gilbert Eddy, died five years after they married.[50]

She wore an imported black satin dress heavily beaded with tiny black jet beads, black satin slippers, beaded, and had on her rarely beautiful diamonds. ... She stood before us, seemingly slight, graceful of carriage, and exquisitely beautiful even to critical eyes. Then, still standing, she faced her class as one who knew herself to be a teacher by divine right.

– C. Lulu Blackman, 1885[51]

Gillian Gill, one of Eddy's biographers, wrote that Eddy was by all accounts charismatic – charming and flattering when she needed to be – and able to inspire great loyalty, although she could also be irrational, capricious and unkind.[52] It was in part because of her unusual personality that Christian Science flourished, despite the numerous legal and other disputes she initiated, including among her closest followers.[53]

"She was like a patch of colour in those gray communities," McClure's wrote, "She never laid aside her regal air; never entered a room or left it like other people. There was something about her that continually excited and stimulated, and she gave people the feeling that a great deal was happening."[54] Mark Twain, a prominent critic of hers, described her as "vain, untruthful [and] jealous," but "[i]n several ways ... the most interesting woman that ever lived, and the most extraordinary."[55]

Phineas Parkhurst Quimby

Eddy tried every remedy for her ailments, including homeopathy, mesmerism, hydropathy at the Vail's Hydropathic Institute in Hill, New Hampshire, and the vegetarian Graham diet of the Rev. Sylvester Graham (1794–1851), who took the view that "all medicine, as such, is itself an evil."[56] According to Ronald Numbers and Rennie Schoepflin, alternative practitioners were much sought after at a time when physicians, or allopaths as they were known, regularly "bled, puked and purged" their patients.[57]

In 1862 Eddy heard of "Quimbyism," a healing method developed by Phineas Parkhurst "Park" Quimby (1802–1866), a former clockmaker who worked in Portland, Maine. Styled Dr. P.P. Quimby, he called himself "a teacher of the science of health and happiness," and his philosophy was "the truth is the cure." This would sometimes consist of shouting at a patient who could not walk, "you can walk!"[58] McClure's wrote of Quimby that, although he had had only six weeks' schooling, he was regarded as a "mild-mannered New England Socrates" because of his refusal to accept anything on authority. So far as local legend was concerned, McClure's wrote, when Quimby got to work consumptives recovered and the blind saw.[59]

Treating people whether or not they could pay, Quimby started practicing after hearing a lecture by the French mesmerist Charles Poyen, who visited Maine in 1838. Mesmerism, also called animal magnetism, was named after Franz Mesmer (1734–1815), a German physician who argued that animals produced an invisible force or fluid that could be used to heal.[60] Quimby saw himself as a medium or clairvoyant who could feel and change this fluid, thereby correcting his patients' mistaken view that they were ill.[61]

Quimby argued that the real person – spiritual man or "scientific man" – is the perfect embodiment of Spirit, Wisdom, Principle, Truth, Mind, Science. Scientific man cannot be sick, but he is overwhelmed by the man of matter and false beliefs. (He drew a similar distinction between Jesus the man and the concept of Christ or Truth.)[62] In the 1850s he began to write his ideas down; he was generous in allowing patients to copy these unpublished manuscripts, which became an issue when Eddy was accused, after his death, of having based her own writing on his.[63]

Eddy wrote to Quimby in August 1862, telling him she could barely sit up; she had to be carried up the stairs to his consulting rooms (she told the Boston Post in 1883 that, before she saw him, she had been more or less confined to her bed or room for seven years).[64] She felt better immediately and returned to see him several times.[65]

The fall in Lynn

Eddy's father died in October 1865 when she was 44 years old, followed by the death of Quimby on January 16, 1866. Eddy wrote a poem on January 22, "Lines on the Death of Dr. P. P. Quimby, Who Healed with the Truth that Christ Taught, in Contradistinction to All Isms," which was published in a local newspaper.[66] Two weeks later, on February 1, Eddy slipped on some ice in Lynn, Massachusetts, injuring her head and neck. She recovered after a few days of bed rest. Years later, she wrote that, while in bed from the fall, she had read a Bible passage about one of Jesus's healings and that it was this reading, or an insight she experienced because of the reading (Eddy called it a revelation), that had healed her. Christian Scientists call this the "fall in Lynn," and see it as the birth of their religion.[67] The first time she published a link between the fall and Christian Science was in 1871 in a letter to a prospective student, after she had started teaching her healing method:

Mrs. Mary Patterson of Swampscott fell upon the ice near the corner of Market and Oxford Streets on Thursday evening and was severely injured. She was taken up in an insensible condition and carried into the residence of S.M. Bubier, Esq., near by, where she was kindly cared for during the night. Doctor Cushing, who was called, found her injuries to be internal and of a serious nature, inducing spasms and internal suffering. She was removed to her home in Swampscott yesterday afternoon, though in a critical condition.

— Lynn Reporter, February 3, 1866[68]

I have demonstrated on myself in an injury occasioned by a fall, that it did for me what surgeons could not do. Dr. Cushing of this city pronounced my injury incurable and that I could not survive three days because of it, when on the third day I rose from my bed and to the utter confusion of all I commenced my usual avocations and notwithstanding displacements, etc., I regained the natural position and functions of the body. How far my students can demonstrate in such extreme cases depends on the progress they have made in this Science."[69]

The physician who treated her, Alvin M. Cushing, swore in an affidavit for McClure's in 1907 that the injury had not been a serious one, that he had not told Eddy otherwise, and that she had responded to morphine and a homeopathic remedy (arnica); she had not said anything to him about a miraculous healing.[70]

The degree to which she considered herself healed at the time is also disputed. Two weeks after the accident she wrote to Julius Dresser (1838–1893), a patient and devotee of Quimby's.[71] She enclosed the poem she had written for Quimby and asked Dresser to "step forward into the place [Quimby had] vacated." She told Dresser she had awoken after the fall to find herself "the helpless cripple I was before I saw Dr. Quimby," and asked if he would treat her.[72] Dresser replied that he had no intention of stepping into Quimby's shoes; it would be more beneficial to teach Quimby's method to others than to practice it, he said.[73]

In June 1866 she again suggested she had not recovered; the Mayor of Lynn told the city Eddy had sent them a letter "in which she states that owing to the unsafe condition of [the streets] ... she slipped and fell, causing serious personal injuries, from which she has little prospect of recovering, and asking for pecuniary recompense for the injuries received."[74] In February 1867 Eddy and her husband, Daniel Patterson, a dentist, filed a lawsuit against the city to recover damages.[75]

In her autobiography, Retrospection and Introspection (1891), Eddy was clear about attributing the discovery of Christian Science prayer to the fall in Lynn.[76] But in the first edition of Science and Health (1875), she wrote that she had discovered it while struggling with indigestion as a child.[77] Eddy offered more than one version of this. In the first edition she wrote that she had spent years of her youth following a rigid version of the Graham diet: a once-a-day helping of vegetables, a slice of bread, and water. She continued: "After years of suffering ... our eyes were suddenly opened, and we learned suffering is self-imposed, a belief, and not truth." In later editions, when the fall in Lynn took precedence, Eddy attributed the indigestion to a woman she had known and offered its disappearance as the result of Christian Science prayer. In the final edition she wrote that it had happened to a man she had known.[78]

Writing and teaching

Richard Kennedy's practice

Eddy and her husband, then married for 13 years, experienced a period of poverty in early 1866, and moved into an unfurnished room in the home of a Baptist minister. At some point her husband left and Eddy was evicted, unable to pay the rent; she moved into a boarding house where two of her biographers surmise that she offered a healing in lieu of rent. Her husband appears to have returned briefly – in August he paid Dr. Cushing's bill from the fall – but the marriage was over and ended in divorce in 1873.[79]

Eddy moved between friends' homes and boarding houses. Money was a constant source of worry. In June and July 1868 she advertised for students in a spiritualist magazine, the Banner of Light, promising a new healing method, a "principle of science" that would heal with "[n]o medicine, electricity, physiology or hygiene required for unparalleled success in the most difficult cases." The ad was signed Mary B. Glover, using her first husband's surname.[80]

She at first called her ideas Moral Science, and later Divine Science, Metaphysical Science, Metaphysical Healing, the Christ-cure and the Truth-cure. In the first edition of Science and Health in 1875 she called it Christian Science too, first using the lower-case science, but later in the same edition capitalizing it.[81] Quimby had referred to the "religion of Christ [being] shown in the progress of Christian science" in his essay Aristocracy and Democracy (February 1863).[82] She may also have found the term in William Adams's (1813–1897) The Elements of Christian Science (1850), and Edmond de Pressensé's (1824–1891) The Early Years of Christianity (1870), copies of which were in her library; she had underlined a passage in de Pressensé's book that referred to primitive Christianity and Christian science.[83]

Eddy became close to a fellow lodger, Richard Kennedy, in one of the Spiritualist boarding houses she lived in (she would later accuse him of using mesmerism against her). When they met he was a teenager working in a box factory. She began to teach him Moral Science and in 1870 they decided to open a practice in Lynn; he would see patients and she would teach. Her business card read "Mrs. Mary M. Glover, Teacher of Moral Science." Kennedy agreed to pay her $1,000 for the previous two years' tuition in quarterly installments of $50.[84] He leased rooms in June that year on the second floor of Miss Susie Magoun's school on the corner of Shepard Street and South Common, and put a sign in the yard, "Dr. Kennedy"; he was 21 at this point and Eddy was in her fifties. The practice became popular; Cather and Milmine wrote that people would say: "Go to Dr. Kennedy. He can't hurt you, even if he doesn't help you."[85]

The Science of Man

Eddy placed an ad in the Lynn Semi-Weekly Reporter on August 13, 1870: "Mrs. Glover, the well-known Scientist, will receive applications for one week from ladies and gentlemen who wish to learn how to heal the sick without medicine, and with a success unequaled by any known method of the present day, at Dr. Kennedy's office, No. 71 South Common Street, Lynn, Mass."[86]

Lynn was a center of the shoe industry, so many of the students were shoe workers. When the classes began Eddy charged $100, raised a few weeks later to $300 (one third of a shoe worker's annual income), for a three-week, 12-lesson course. She based the lessons on an unpublished manuscript that she called The Science of Man or the principle which controls all phenomena, and later The Science of Man by which the Sick are healed, or Questions and Answers in Moral Science. McClure's and others charged that this manuscript was Quimby's.[87]

In these early years Eddy did acknowledge her debt to Quimby. When a prospective student asked in 1871 whether her methods had been advertised or practiced before, she replied: "Never advertised and practiced only by one individual who healed me, Dr. Quimby ... I discovered the art in a moment's time, and he acknowledged it to me; he died shortly after and since then, eight years, I have been founding and demonstrating the science."[88] Two books were published around that time, The Mental Cure (1871) and Mental Medicine (1872), by Warren F. Evans, a Swedenborgian minister who had been in touch with Quimby, and which elaborated on the same or a similar healing system.[89]

Eddy's classes consisted of lessons in metaphysics, in question-and-answer format, beginning with "What is God?" The answer was "Principle, wisdom, love, and truth," rather than the anthropomorphic vision the students were used to.[90] They were told to make a copy of the manuscript, but were forbidden, under a $3,000 bond, from showing it to anyone. They agreed to pay her 10 percent annually of any income they derived from her methods and $1,000 if they did not practice or teach it.[91] The manuscript advised students to rub their patients' heads, as Quimby had done, but when a student accused Eddy of practicing mesmerism and demanded a refund, she told her remaining students to ignore that part of the manuscript, and from that point on Christian Science healing did not involve touching patients.[92]

It was a running thread throughout Eddy's life that she fell out with those around her, and inevitably Kennedy was added to that list. He came to believe that Moral Science could achieve far less than Eddy promised, and although his practice and her classes were flourishing he urged her to be more circumspect, which angered her. In November 1871 she accused him in front of others of cheating at cards; it was one of many scenes she had caused between them and he walked out on her, ignoring one of her fainting spells.[93]

Mary B. Glover's Christian Scientists' Home

Once Kennedy and Eddy had settled their financial affairs in May 1872, she was left with $6,000. Peel writes that she had already started work on Science and Health, and at that point had completed 60 pages. She again moved between boarding houses and the homes of friends, and was renting rooms in Lynn at 9 Broad Street, when the house opposite came on the market. She purchased 8 Broad Street in March 1875 for $5,650, taking in tenants to pay the mortgage. It was in the attic room of this house that she completed the first edition of Science and Health.[93]

Shortly after moving in, Eddy became close to another student, Daniel Spofford. He was 33 years old and married when he joined her class (his wife had taken it years earlier); he ended up leaving his wife in the hope that he might marry Eddy, but his feelings were not reciprocated. Spofford and seven other students agreed to form an association that would pay Eddy a certain amount a week for one year if she would preach to them every Sunday. They called themselves the Christian Scientists Association.[95] Spofford would later find himself the object of Eddy's fury: expelled from the association, sued for engaging in mental malpractice, and allegedly targeted for murder by Eddy's third husband (a claim that remained unproven).[96]

Eddy placed a sign on 8 Broad Street, Mary B. Glover's Christian Scientists' Home.[97] According to Cather and Milmine, there was a regular turnover of tenants and domestic staff, whom Eddy accused of stealing from the house; she blamed Richard Kennedy for using mesmerism to turn people against her.[98] Peel writes that there was local gossip about the attractive woman, the men who came and went, and whether she was engaged in witchcraft. She was hurt, but made light of it: "Of course I believe in free love; I love everyone."[99]

Science and Health

Eddy copyrighted her book, then called The Science of Life, in July 1874. Several publishers turned it down, but in September that year a printer agreed to handle it if Eddy would pay the costs.[100] Three of her students, George Barry, Elizabeth Newhall and Daniel Spofford, came up with the necessary $2,000, and after much proofreading and revision by Eddy it was published by the Christian Science Publishing Company on October 30, 1875, as Science and Health, with eight chapters and 456 pages. (Barry ended up suing Eddy for, among other things, payment for his copying the manuscript in long hand for the printer.)[101]

Martin Gardner (1914–2010) called the book a "chaotic patchwork of repetitious, poorly paragraphed topics," full of spelling, punctuation and grammatical mistakes.[102] It was positively received by Amos Bronson Alcott (1799–1888), who wrote to Eddy in January 1876 that she had "reaffirm[ed] in modern phrase the Christian revelations," and that he was pleased it had been written by a woman.[103]

Eddy added Key to the Scriptures to the sixth edition in 1884, and for the 16th edition in 1886 hired an editor, James Henry Wiggin (1836–1900), a Unitarian clergyman. Eddy's personal assistant, Calvin Frye (1845–1917), first contacted Wiggin for help in August 1885; Wiggin told his literary executor (who first made this public after Wiggin's death) that he had been surprised by the mistakes, contradictions and untidy structure in Science and Health, so he rewrote the book. He removed some contradictions, reduced the demonology chapter, added some Greek, Latin and Sanskrit, and wrote a new chapter, "Wayside Hints." Robert Peel (1909–1992) wrote that Wiggin "toned up" Eddy's style, but did not affect her thinking.[104] Twenty-two editions were published between 1886 and 1888.[105]

People said that simply reading Science and Health had been enough to heal them; cures were claimed for everything from cancer to blindness. New York lawyer William Purrington argued in 1900 that the beneficiaries were "hysterical patients, the morbidly introspective, the worriers, the malades imaginaires, the victims of obscure nervous ailments."[106] Richard Cabot (1868–1939) of Harvard Medical School investigated the testimonies that appeared in the Christian Science Journal, which Eddy founded in 1883, for his senior thesis, The Medical Bearing of Mind-Care (1892).[107] He wrote in McClure's in 1908 that the claims were based on self-diagnosis or secondhand stories about what a doctor had supposedly said; he attributed them to the placebo effect.[108]

Eddy continued to revise the book until her death in 1910, issuing 432 editions in all; the final edition ran to 18 chapters and 600 pages.[109] She encouraged members to buy a new copy whenever she published a major revision, which brought in significant earnings.[110] Other income derived from the sale of rings and brooches, pictures of Eddy, and in 1889 the Mary Baker Eddy souvenir spoon; Eddy asked every Christian Scientist to buy at least one, or a dozen if they could afford to.[111]

When the copyright on Science and Health expired in 1971, the church persuaded Congress to pass a law (overturned in 1987 as unconstitutional), extending it to the year 2046; the bill was supported by two of President Nixon's aides, Christian Scientists H.R. Haldeman (1926–1993) and John Ehrlichman (1925–1999).[112] By April 2001, according to the church, the book had sold ten million copies and was available in 16 languages and English Braille.[5]

Eddy's view: sickness is belief

Science and Health expanded on the view that sickness was simply a belief. Eddy wrote in the first edition: "Physical effects proceed from mental causes; the belief we can move our hand moves it, and the belief we cannot do this renders it impossible during this state of mind. Palsy is a belief that attacks mind, and holds a limb inactive independent of the mind's consent, but the fact that a limb is moved only with mind proves the opposite, namely, that mind renders it also immovable."[113]

My experiments in homeopathy had made me sceptical as to material curative methods. ... [T]he drug is attenuated to such a degree that not a vestige of it remains; and from this I learn that it is not the drug that cures the disease or changes one of the symptoms ... The highest attenuation of homeopathy and the most potent steps out of matter into Mind; and thus it should be seen that Mind is the healer, or metaphysics, and that there is no efficacy in the drug.

– Mary Baker Eddy, 1889[114]

"Agree not with sickness," she wrote, "meet the physical condition with a mental protest, that destroys it as one property destroys another in chemistry."[115] She wrote years later that she had personally healed tuberculosis, diphtheria and cancer: "at one visit a cancer that had eaten the flesh of the neck and exposed the jugular vein so that it stood out like a cord. I have physically restored sight to the blind, hearing to the deaf, speech to the dumb, and have made the lame walk."[116]

Eddy's views derived in part from her skepticism about homeopathy, after she witnessed what was arguably the placebo effect in patients she said she had treated with homeopathic remedies; they seemed to recover despite being administered remedies so diluted they were drinking plain water. She concluded from this that Mind, or what she called "metaphysics," was the healer.[114]

In later editions of Science and Health she wrote that even naming and reading about disease could turn thoughts into physical symptoms.[117] She argued similarly against the recording of ages: "Timetables of birth and death are so many conspiracies against manhood and womanhood."[118] To counter the argument that people can be harmed by poison in the absence of any belief about it, she referred to the power of majority opinion.[119]

She allowed exceptions from Christian Science prayer for the dentist and basic surgical procedures, such as fixing broken limbs; she said that she had healed broken bones using "mental surgery," but that this skill would be the last to be learned.[120] She herself wore glasses, used morphine, had her third husband treated by a physician, and arranged for an autopsy when he died.[121] But for the most part (then and now), Christian Scientists believe that medicine and Christian Science prayer are incompatible, because they proceed from contradictory assumptions. Medicine asserts that something is physically broken and needs to be fixed, while Christian Science asserts that the spiritual reality is perfect and any belief to the contrary needs to be corrected.[122]

Eddy's debt to Quimby

Gill wrote that the nature of Eddy's debt to Quimby became the single most controversial issue of her life.[123] In her later work Eddy drew a distinction between her methods and Quimby's, maintaining that "Christian Science is based on the action of the divine Mind over the human mind and body whereas, 'mind-cure' rests on the notion that the human mind can cure its own disease."[124] She described her relationship to his work in various ways over the years, but in 1883 summed it up as: "We caught some of his thoughts, and he caught some of ours; and both of us were pleased to say this to each other."[125]

It is apparent, then, that in Christian Science it is not one man's mind acting upon another man's mind that heals; that it is solely the Spirit of God that heals; that the healer's mind performs no office but to convey that force to the patient; that it is merely the wire which carries the electric fluid, so to speak, and delivers the message. Therefore, if these things be true, mental-healing and Science-healing are separate and distinct processes, and no kinship exists between them.

– Mark Twain, Christian Science (1907)[126]

In 1882 one of Quimby's followers, Julius Dresser, arrived in Boston, apparently angry to find that, in his view, Eddy was teaching Quimby's methods as her own. In February 1883 there was an exchange of letters in the Boston Post. Dresser or an associate (the letter was signed "A. O.") accused "some parties healing through a mental method" of having taken Quimby's unpublished ideas.[127] Eddy or an associate (the letter was signed "E. G.") disparaged Quimby as a mesmerist and claimed "the science of healing" for Eddy.[128] Dresser replied that Eddy had copied Quimby's writings. Eddy wrote, in turn, that she had "laid the foundation of mental healing" before she met Quimby.[129]

The issue ended up in court in September 1883 when Eddy filed a complaint that Edward J. Arens, one of her students, had published a pamphlet in 1881, Theology, or the Understanding of God as Applied to Healing the Sick, that copied over 20 pages of Science and Health (he credited Quimby, the Gottesfreunde, Jesus, and "some thoughts contained in a work by Eddy").[130] Arens counter-claimed that Eddy had copied it from Quimby in the first place. Quimby's son was so unwilling to produce his father's manuscripts that he sent them out of the country for safe-keeping, and Eddy won the case.[131]

Eddy suggested that her own work was being confused for Quimby's; she had "take[n] Quimby's scribblings and fix[ed] them over for him," and now stood accused of having copied her own writing.[132] She had also handed her manuscripts out to students, and now people were saying those texts were not hers.[133] In July 1904 the New York Times obtained one of Quimby's manuscripts and she was again accused.[134] McClure's repeated the charge in 1907: "For 20 closely written pages, Quimby's manuscript, Questions and Answers, is word for word the same as Mrs. Glover's manuscript, The Science of Man."[135]

Quimby's manuscripts were published in full in 1921. Eddy's biographers differ as to whether Eddy relied on them. Part of the confusion stems from the difficulty of finding and comparing early versions of Eddy's Science and Man pamphlets; the Rare Book Company of New Jersey has published several of them.[136] Ernest Sutherland Bates (1879–1939) and John V. Dittemore (1876–1937), a former director of the Christian Science church, argued in 1932 that "as far as the thought is concerned, Science and Health is practically all Quimby," except for malicious animal mesmerism.[137] Robert Peel, who also worked for the church, wrote in 1966 that there are traces of Eddy in Quimby's work, and that she may have influenced him as much as he influenced her.[138] Gillian Gill maintained in 1998 that there were only general similarities, while Caroline Fraser wrote a year later that the plagiarism claims had been exaggerated, but that it was clear Quimby was Eddy's inspiration.[139]

=Eddy's Debt to Wesley and Tremont Temple

The 19th century religious landscape was complex making it difficult to categorize the healing movements of the time.[140] The explosion of Protestant divine healing movements (also referred to as faith healing, faith cure, or simply healing movement) was non-denominational including several Protestant denominations. It's roots lying in the Primative Methodists inspired by "A Plain Account of Christian Perfection" written by John Wesley[141].[142]the minister who founded Methodism. Christian Science needs to be viewed within the context of the Holiness movement both because of the access this movement gave to women[143] and because Eddy was “an heir to Wesley’s understanding of Christian Healing.”[144]

John Wesley ‘emphasized the importance of subjective experience of the Spirit’ and wrote “I believe that God now hears and answers prayer even beyond the ordinary course of nature.” [145] Although he healed, spiritual healing was not his focus. In the 1830’s American Methodist lay woman, Phoebe Palmer “reformulated” John Wesley’s teaching. [146] Palmer argued that ‘perfection’ or ‘holiness’ didn’t need to be a process but could be immediate. Physical healing of the body was evidence of instantaneous sanctification. Ethan O. Allen a Methodist layman who believed that purification from sin would eradicate sickness, became the first evangelist to make healing his ministry. Charles Cullis, an Episcopal layman and homeopathic physician in Boston advocated that complete salvation included both spiritual and physical healing.[147]

Mary Baker Eddy is included in the list of Protestant reformers “who objected to the notion that God ordained bodily suffering”. [148]. “Faith cure and Christian Science did seem to propose a similar hermeneutics of healing”. [149] and Christian Science had in common the beliefs of nineteenth century evangelical Protestantism which included a strong belief in the spiritual power of healing.[150][151][152] All of these healing movements "involved rejecting a materialistic view of the body" and giving up the ethic of passive resignation.[153] Clergy tried to make a distinction between Christian Science and the divine healing movement. Still in the eyes of the public, they seemed the same. [154]

In 1885 Methodist minister and Boston University Professor Luther T. Townsend, an adversary among others, of the divine healing movement and mind cure movement, wrote a treatise called “Faith Work, Christian Science and Other Cures”. In that treatise Townsend highlighted the similarities between the divine healing movement and Christian Science saying both were the response of the operation of ordinary ‘physical laws’ without intervention or the miraculous power of God. Around the same time A.J. Gordon a proponent of Christian perfection and involved in the divine healing movement, wanted to distance his movement from Christian Science.[155] A letter, written by Gordon was sent to the popular Evangelical Boston lecturer Joseph Cook,[156] and in February 1885 at the Tremont Temple Monday lectures, to a crowd of 3,000, the letter was read by Cook. Through the letter Gordon attacked Christian Science saying it was a 'false religion'.[157] He also said through Cook that “it was anti-christian in it’s no personal Deity, no personal devil, no personal man, no forgiveness of sin, no such thing as sin, no sacrificial atonement, no intercesary prayer”.[158] Hearing about the attack, Mary Baker Eddy wrote Cook and asked for the opportunity to reply. He agreed and gave her 10 minitues to defend her system of healing as Christian at one of the Monday Tremont Temple lectures[159]

On March 16, 1885 at Tremont Temple, to a crowed of 3,000[160] in an extemporaneous reply, Eddy asked “Do not the reverend gentlemen demand the right to explain their creed?”[161] She then commenced to explain her doctrines on atonement, God, sin and the trinity. She said

- Do I believe in a personal God?

- I believe in God as the Supreme Being. I know not what the person of omnipotence and ominipresence is, or :::what the infinite includes; therefore, I worship that of which I can conceive, first as a loving Father and Mother; then as thought ascends the scale of being to diviner consciousness, God becomes to me, as to the apostle who declared it, “God is Love”, - divine Principle, - which I worship; and ‘after the manner of my fathers, so worship I God.”[162]

In reply to attacks on her doctrine of atonement, Eddy replied that ‘this becomes more to me since it includes man’s redemption from sickness as well as from sin. I reverence and adore Christ as never before.” [163] Some argue that Eddy’s doctrine of atonement, which includes both salvation from sin and suffering was the same doctrine of the faith cure movement and a result of the Protestant healing movement of the 1830's [164] [165] Although having "obvious ties to Christian tradition",[166] many theologians feel a deeper understanding of the theology places it outside traditional Christian theology. Today Christian Scientists distance themselves from 20th century faith cure movements who have have “ridgely proscriptive views of medicine” . [167].

Malicious animal magnetism

In January 1877 Eddy spurned an approach from Daniel Spofford, and to everyone's surprise married another of her students, Asa Gilbert Eddy (1826–1882).[168] Eddy already believed that her former student Richard Kennedy was plotting against her; weeks after the wedding Spofford was suspected too. She had hinted in October 1876 that he might be a successor; instead he found himself expelled from the Christian Scientists' Association in January 1878 for "immorality" after quarrelling with her over money. She also filed lawsuits against Spofford and several other students to recover royalties from their healing practices or unpaid tuition fees. Cather and Milmine wrote that Eddy "required of her students absolute and unquestioning conformity to her wishes; any other attitude of mind she regarded as dangerous."[169]

The conviction that she was at the center of plots and counter-plots became a feature of Eddy's life. This was expressed as a belief that the mind could act at a distance to cause harm or even death (or, at least, the illusion of harm or death), and that several of her students were using this power against her. She called it malicious animal magnetism (MAM), malicious mesmerism or mental malpractice.[170] Eddy wrote in earlier editions of Science and Health, for example in 1889, that MAM was "literally demonology" (a sentence missing from the final edition), and that it had gained strength from Christian Science "as if to forestall the power of good."[171] She spoke openly about it, including to the press, despite the ridicule it attracted.[172]

Everything that went wrong in her life from the late 1870s she blamed on MAM.[173] Cather and Milmine wrote: "Those of her students who believed in mesmerism were always on their guard with each other, filled with suspicion and distrust. Those who did not believe in it dared not admit their disbelief."[174]

Salem witchcraft trial, murder charge

In May 1878 Eddy brought a case against Spofford, in the name of a patient, Lucretia Brown, in Salem, Massachusetts, for practicing mesmerism; it came to be known as the second Salem witchcraft trial. For reasons that remain unclear, Brown believed that Spofford had bewitched her, causing her, according to Eddy, "severe spinal pains and neuralgia and a temporary suspension of mind."[175] Eddy held a power of attorney allowing her to appear in court on Brown's behalf, along with 20 of her supporters (a "cloud of witnesses," according to the Boston Globe), but Judge Horace Gray (1828–1902) declined to hear the case.[176] Amos Bronson Alcott accompanied Eddy to the hearing.[177]

In preparation for the hearing, Eddy organized a 24-hour "watch" at 8 Broad Street, during which she asked 12 of her students to use their minds for two hours each to think of Spofford and block the MAM.[178] She continued to organize these watches for the rest of her life; the students, known as mental workers or metaphysical workers, would be required to give "adverse treatment" to one of her enemies, often Richard Kennedy, calling him, for example, bilious, consumptive, or poisoned by arsenic.[179] According to Adam H. Dickey, her private secretary for the last three years of her life, she required the watchers to attend hour-long meetings at least twice a day to address manifestations of MAM.[180]

The attempt to have Spofford tried was not the end of the dispute. In October 1878 Eddy's husband and another of her students, Edward Arens (whom Eddy accused four years later of having killed her husband with MAM when he died of a heart condition), were charged with conspiring to murder Spofford. A barman said they had offered him $500 to carry out the killing; after a complex series of claims and counter-claims, the charges were dropped when a key witness retracted his statement.[181] Eddy attributed the allegations to a plot by former students to undermine sales of the second edition of Science and Health, just published.[182] Her lawyer ended up having to file for an attachment order against her house to collect his fee.[183]

Growth

Establishing the church, move to Boston

On August 23, 1879, the Christian Scientists' Association was granted a charter to form the Church of Christ (Scientist).[184] With an initial congregation of 26 members, services were held in people's homes in Lynn and later in Hawthorne Hall, Boston.[185] On January 31, 1881, Eddy was granted another charter to form the Massachusetts Metaphysical College. The college lived wherever Eddy did; a new sign appeared on 8 Broad Street. The college's stated purpose: "To teach pathology, ontology, therapeutics, moral science, metaphysics, and their application to the treatment of disease."[186]

In October 1881 there was a revolt. Eight of the church's most active members resigned after tiring of malicious mesmerism and the legal disputes. They signed a document complaining of Eddy's "frequent ebullitions of temper, love of money, and the appearance of hypocrisy." Only a few students remained, including Calvin Frye (1845–1917), who went on to become her most loyal personal assistant. Eddy rallied the remaining members, who appointed her pastor of the new church in November 1881. They drew up a resolution in February 1882 that she was "the chosen messenger of God to the nations," and "unless we hear Her voice we do not hear His voice."[187]

The resignations ended Eddy's time in Lynn. The church was struggling to survive and her reputation had been damaged by the disputes. By now 61 years old, she decided to move to Boston and in early 1882 rented a house at 569 Columbus Avenue, a silver plaque announcing the arrival of the Massachusetts Metaphysical College.[188] Between 1881 and October 1889, when Eddy closed the college, 4,000 students took her 12-lesson course, at $300 per person or married couple, making her a rich woman.[189] Mark Twain wrote that she had turned a sawdust mine (possibly Quimby's) into a Klondike.[190]

Third husband's death

Shortly after the move to Boston, Eddy's husband died of heart disease. On the day of his death, June 4, 1882, she asked the Boston Globe to send a reporter to her home. The newspaper said she "could scarcely control herself enough to make the following statement":

Her husband, she said, had died with every symptom of arsenical poisoning. Both he and she knew it to be the result of a malicious mesmeric influence exerted upon his mind by certain parties here in Boston, who had sworn to injure them. She had formerly had the same symptoms of arsenical poison herself, and it was some time before she discovered it to be the mesmeric work of an enemy. Soon after her marriage her husband began to manifest the same symptoms and had since shown them from time to time; but was, with her help, always able to overcome them. A few weeks ago she observed that he did not look well, and when questioned he said that he was unable to get the idea of this arsenical poison out of his mind. He had been steadily growing worse ever since, but still had hoped to overcome the trouble until the last. After the death the body had turned black.[191]

A doctor performed an autopsy and showed Eddy her husband's diseased heart, but she responded with more interviews about mesmerism.[192] Fraser wrote that the articles made Eddy a household name, a real-life version of the charismatic and beautiful Verena Tarrant in Henry James's The Bostonians (1885–1886), with her interest in spiritualism, women's rights and the mind cure.[193]

First journal, first church

After her husband's death, Eddy moved next door to 571 Columbus Avenue. Several students moved in with her; she taught and they saw patients.[194] In 1883 she founded the Journal of Christian Science, later called the Christian Science Journal, which spread news of her ideas still further.[195] According to Cather and Milmine: "Copies found their way to remote villages in Missouri and Arkansas, to lonely places in Nebraska and Colorado, where people had much time for reflection, little excitement, and a great need to believe in miracles."[196]

In 1885 Eddy was accused of Spritualism, pantheism, theosophy and blasphemy by the Reverend Adoniram J. Gordon (1836–1895), a Baptist minister, in a letter read out by the Reverend Joseph Cook at Tremont Temple in Boston. She demanded a right of reply and was offered ten minutes on March 16.[197] According to Stephen Gottschalk (1941–2005), the occasion marked the "emergence of Christian Science into American religious life."[198] Before a congregation of 3,000, Eddy denied that she was a Spiritualist; she said that "[t]here have always attended my life phenomena of an uncommon order, which spiritualists have miscalled mediumship, but I clearly understand that no human agencies were employed." She told them she believed in God as the Supreme Being, Love, divine Principle, Mind; and she affirmed her belief in the atonement. She described Christian Science healing "not [as] one mind acting upon another mind," but as "Christ come to destroy the power of the flesh; it is Truth over error."[199]

Ernest Sutherland Bates and John V. Dittemore, in their 1932 biography of Eddy, wrote that the years 1884–1888 saw Christian Science develop into an established national institution. Eddy was teaching four to six classes of practitioners a year and by 1889 had probably made at least $100,000.[200] The first church building was erected in 1886 in Oconto, Wisconsin, at a cost of $1,137.20, by several local women who felt that Christian Science had helped them.[201] The National Christian Scientists' Association was formed the same year, and for a down payment of $2,000 and a mortgage of $8,763 the church purchased land in Falmouth Street, Boston, for the erection of a church building.[202] Eddy asked Augusta Stetson (1842–1928), a prominent Scientist, to go to New York to set up a church there too.[203]

According to Bates and Dittemore, by the end of 1886 small Christian Science teaching institutes had sprung up around the United States: the California Metaphysical Institute, the Chicago Christian Science University, the Academy of Christian Science in Boston. In December 1887 Eddy moved to a $40,000, 20-room house at 385 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston.[204] By 1890 the Church of Christ (Scientist) had 8,724 members in the United States, after starting out 11 years earlier with just 26.[205]

First prosecutions

In 1887 Eddy started teaching a "metaphysical obstetrics" course consisting of two one-week classes. She had styled herself "Professor of Obstetrics" in 1882 and had been allowing her students to attend women in childbirth for years. McClure's wrote: "Hundreds of Mrs. Eddy's students were then practising who knew no more about obstetrics than the babes they helped into this world."[206]

The first prosecution of Christian Scientists was in March 1888, when Abby H. Corner, a practitioner in Medford, Massachusetts, was charged with manslaughter after attending to her own daughter during childbirth; the daughter bled to death and the baby did not survive. Corner was acquitted after the defense argued that they might have died even with medical attention.[207] Eddy distanced herself from Corner, to the dismay of the Christian Scientists' Association (the secretary resigned). She told the Boston Globe that Corner had never entered the obstetrics class and had attended the college for one term only.[208]

From then until the 1990s around 50 parents and practitioners were prosecuted after adults and children died without medical care.[2] The American Medical Association (AMA) declared war on Christian Scientists, calling them in 1895: "Molochs to infants, and pestilential perils to communities in spreading contagious diseases."[209] Juries were nevertheless reluctant to convict where there was a sincere belief that the patient was being helped. There was also opposition to the AMA's effort to strengthen medical licencing laws to outlaw Christian Science treatment. Historian Shawn Francis Peters writes that other religions rallied to the Christian Scientists' defence; in the courts and in public debate, Christian Scientists and Jehovah's Witnesses linked their healing claims directly to early Christianity to gain support from other Christians.[210]

In 1893 Ezra Buswell, a practitioner in Beatrice, Nebraska, was charged with practicing medicine without a licence after a child died of cholera under his care; a jury acquitted but he was convicted on appeal.[211] Practitioners in Ohio, Minnesota and Wisconsin were acquitted of the same offence in 1898, 1899 and 1900.[212] In 1898 novelist Harold Frederic, London correspondent for the New York Times, died in England of heart disease after being attended to by a practitioner, but the charge of manslaughter was dropped.[213] The following year seven-year-old Rolfe Saunders died of pneumonia without medical care at Fort Porter, near Buffalo, New York; a grand jury failed to return indictments against his Christian Scientist parents and two practitioners.[214]

Eddy issued instructions in 1902 that Christian Scientists would no longer treat infectious diseases and should report them as required by law, after the death that year of seven-year-old Esther Quimby of diphtheria in White Plains, New York; her parents and the practitioner were charged with manslaughter, but the case was dismissed.[215] In England in 1913 Christian Scientist Benjamin Jewell was also acquitted of manslaughter after his seven-year-old daughter died of diphtheria.[216]

Building the Mother Church, fastest growing religion

In 1888 Eddy became close to another of her students, Ebenezer Johnson Foster, a homeopath and graduate of the Hahnemann Medical College, Philadelphia. There was a significant age gap between them (he was 41 and she was 67), but apparently needing affection and someone to be loyal to her she adopted him legally in November that year and he changed his name to Ebenezer Johnston Foster Eddy.[217]

A year later, in October 1889, she closed the Massachusetts Metaphysical College; Bates and Dittemore wrote that she may have been concerned that the state attorney was investigating colleges that were fraudulently graduating medical students. She also foreclosed the mortgage on the land in Boston the church had purchased, then purchased it herself for $5,000 through a middle man, though it was worth considerably more. She told the church they could have the land for their building on condition that they formally dissolve the church; this was apparently intended to quash several internal rebellions that had troubled her.[218]

The cornerstone of the Mother Church, The First Church of Christ, Scientist – hollow and containing the Bible, Eddy's writings, and a list of directors and financial contributors – was laid in May 1894 in the Back Bay area of Boston.[219] Church members raised funds for the construction, and the building was finished in December 1894 at a cost of $250,000.[220] It contained a "Mother's Room" in the tower for Eddy's personal use, though she spent only one night there and it was later turned into a storage room. The archway at the entrance to the room was made of Italian marble, with the word Mother engraved on the floor. It was furnished with rare books, silks, tapestries, Persian rugs, a 200-year-old lamp, a fireplace rug made of 100 duck skins, and a dressing gown, slippers, handkerchiefs and a pin cushion.[221]

Within two years the Boston membership had exceeded the church's seating capacity, and plans began for an extension. By 1903 the whole block around the church had been purchased by Christian Scientists and the extension was completed in 1906; it accommodated 5,000 people at a cost of $2 million.[222] This attracted the criticism that, whereas Christian Scientists spent money on a magnificent church, they maintained no hospitals, orphanages or missions in the slums.[223]

Christian Science went on to become the fastest growing American religion in the first few decades of the 20th century.[224] The US federal religious census recorded 85,717 Christian Scientists in 1906; 30 years later it was 268,915.[225] There were seven Christian Science churches in the US in 1890 and 1,077 by 1910. Churches began to appear in other countries: 58 in England, 38 in Canada and 28 elsewhere by 1910.[226]

View of Mark Twain

Mark Twain was a prominent contemporaneous critic of Eddy's. His first article about her was published in Cosmopolitan in October 1899.[227] Another three appeared between December 1902 and February 1903 in North American Review, then a book, Christian Science (1907).[228] He also wrote "The Secret History of Eddypus, the World Empire" (1901–1902), in which Christian Science replaces Christianity and Eddy becomes the Pope.[229]

Twain described Eddy as "[g]rasping, sordid, penurious, famishing for everything she sees – money, power, glory – vain, untruthful, jealous, despotic, arrogant, insolent, pitiless where thinkers and hypnotists are concerned, illiterate, shallow, incapable of reasoning outside of commercial lines, immeasurably selfish."[230] He believed she was using Christian Science to accrue wealth: "From end to end of the Christian Science literature not a single (material) thing in the world is conceded to be real, except the Dollar."[231]

Science and Health he called "strange and frantic and incomprehensible and uninterpretable" (and he argued that Eddy had not written it herself):[232] "There is nothing in Christian Science that is not explicable; for God is one, Time is one, Individuality is one, and may be one of a series, one of many, as an individual man, individual horse; whereas God is one, not one of a series, but one alone and without an equal."[227] Eddy apart, Twain felt ambivalent toward mind-cure; he argued that "the thing back of it is wholly gracious and beautiful."[233] His daughter Clara (1874–1962) became a Christian Scientist and wrote a book about it, Awake to a Perfect Day (1956).[234]

McClure's articles

The first biography of Eddy, and the first history of Christian Science, appeared in McClure's magazine (1893–1929) in a devastating critique published in 14 installments between January 1907 and June 1908, preceded by an editorial in December 1906.[236] The essence of the articles was that Eddy was dishonest, had taken her ideas from Quimby, and her chief concern was money. The material, which included court documents and affidavits from people who knew Eddy, was published in book form in 1909 as The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy and the History of Christian Science.[237] It became the key source for most subsequent non-church histories of the religion.[238]

The editor-in-chief S.S. McClure (1857–1949) assigned five writers to work on the series: Willa Cather (1873–1947), the principal author; Burton J. Hendrick (1870–1949); Will Irwin (1873–1948); political columnist Mark Sullivan (1874–1952); researcher Georgine Milmine (1874–1950); and briefly Ida Tarbell (1857–1944).[239] The book was kept out of print from early in its life by the Christian Science church, which bought the original manuscript.[240] It was republished in 1971 by Baker Book House when its copyright expired, and again in 1993 by the University of Nebraska Press.[239]

In his introduction to the 1993 edition, David Stouck wrote that Willa Cather's portrayal of Eddy contains "some of the finest portrait sketches and reflections on human nature" that she would ever write.[241] Gillian Gill wrote that some of the McClure's writers were in touch with the litigants in the so-called "Next Friends" suit in 1907, in which Eddy's relatives sought to have her declared unable to manage her own affairs, and that each side was feeding information to the other, to the detriment of accuracy.[242]

Next Friends suit, Christian Science Monitor, Eddy's death

In March 1907 several of Eddy's relatives filed an unsuccessful lawsuit, the "Next Friends suit," against members of Eddy's household, alleging that they were misusing her property, and that Eddy, by then 85 years old, was unable to conduct her own affairs. Calvin Frye, her long-time personal assistant, was a particular target of the allegations.[243] The litigants consisted of Eddy's closest relatives (or "next friends"): her biological son, George Glover; granddaughter, Mary Baker Glover; two nephews, George W. Baker and Fred W. Baker; and adoptive son, Ebenezer J. Foster Eddy.[244]

Gill wrote that the lawsuit originated with stories in the New York World (1860–1931), owned by Joseph Pulitzer (1847–1911), that Eddy was sick and dying; the newspaper apparently paid for some of the plaintiffs' legal expenses, because it wanted to secure a story to rival the McClure's series.[243] Four psychiatrists (then known as "alienists") were sent to Eddy's home to interview her as part of the proceedings, and concluded that she was mentally competent. One of them, Dr. Allan McLane Hamilton (1848–1919), told the New York Times that the attacks on Eddy were the result of "a spirit of religious persecution that has at last quite overreached itself."[246]

In response to the stories in the New York World and McClure's, Eddy asked the Christian Science Publishing Society on August 8, 1908, to found the Christian Science Monitor as a platform for responsible journalism.[247] It was published for the first time on November 25 that year,[248] and went on to win seven Pulitzer Prizes between 1950 and 2002.[249]

Eddy died two years later, on the evening of Saturday, December 3, 1910, aged 89. The first reader of the Mother Church in Boston announced the death at the end of the Sunday morning service, saying that Eddy had "passed from our sight." The church issued a statement reaffirming its belief that "the time will come when there will be no more death," but that Christian Scientists "do not look for [Mrs. Eddy's] return in this world."[250] It placed an armed guard outside her tomb at Mount Auburn cemetery, which triggered complaints from Christian Scientists who believed she would be resurrected.[251] Her estate was valued at $1.5 million, most of which she left to the church.[252]

Decline and reasons for the rise

| Christian Science practitioners (US) (Stark 1998)[253] |

Practitioners per million | |

|---|---|---|

| 1883 | 14 | 0.3 |

| 1887 | 110 | 1.9 |

| 1895 | 553 | 7.9 |

| 1911 | 3,280 | 34.9 |

| 1919 | 6,111 | 58.5 |

| 1930 | 9,722 | 79.0 |

| 1941 | 11,200 | 84.0 |

| 1945 | 9,823 | 70.2 |

| 1953 | 8,225 | 51.7 |

| 1972 | 5,848 | 28.0 |

| 1981 | 3,403 | 15.1 |

| 1995 | 1,820 | 6.9 |