7 July 2005 London bombings

| 7 July 2005 London bombings | |

|---|---|

Emergency vehicles at Russell Square following the bombings. | |

| Location | London, United Kingdom |

| Date | 7 July 2005 8:50 am – 9:47 am (UTC+1) |

| Target | Transport in London |

Attack type | Suicide bombings |

| Deaths | 52 |

| Injured | ≈700 |

| Perpetrators | Hasib Hussain, Mohammad Sidique Khan, Germaine Lindsay, and Shehzad Tanweer |

The 7 July 2005 London bombings (also called the 7/7 bombings) were a series of coordinated bomb blasts planned by Islamist extremists motivated by the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan. Hitting London's public transport system during the morning rush hour; at 8:50 a.m. three bombs exploded within fifty seconds of each other on three London Underground trains. A fourth bomb exploded on a bus nearly an hour later at 9:47 a.m. in Tavistock Square. The bombings killed 52 commuters and the four suicide bombers, injured 700, and caused disruption of the city's transport system (severely for the first day) and the country's mobile telecommunications infrastructure. The series of suicide-bomb explosions constituted the largest and deadliest terrorist attack on London in its history.

Incidents

Attacks on the Underground

08:50 — Three bombs on the London Underground exploded within fifty seconds of each other:

- The first bomb exploded on an eastbound Circle Line sub-surface Underground train, number 204, travelling between Liverpool Street and Aldgate. The train had left King's Cross St. Pancras about eight minutes earlier. At the time of the explosion, the third carriage of the train was approximately 100 yards (90 m) down the tunnel from Liverpool Street. The parallel track of the Hammersmith and City Line from Liverpool Street to Aldgate East was also damaged.

- The second bomb exploded on the second carriage of a westbound Circle Line sub-surface Underground train, number 216. The train had just left platform 4 at Edgware Road and was heading for Paddington. The train had left King's Cross St. Pancras about eight minutes earlier. There were several other trains nearby at the time of the explosion. An eastbound Circle Line train (arriving at platform 3 at Edgware Road from Paddington) was passing next to the train and was damaged,[1] along with a wall that later collapsed. There were two other trains at Edgware Road: an unidentified train on platform 2, and an eastbound Hammersmith & City Line train that had just arrived at platform 1.

- The third bomb exploded on a southbound Piccadilly Line deep-level Underground train, number 311, travelling between King's Cross St. Pancras and Russell Square. The bomb exploded about one minute after the train left King's Cross, by which time it had travelled about 500 yards (450 m). The explosion took place at the rear of the first carriage of the train, causing severe damage to the rear of that carriage, as well as the front of the second one.[2] The surrounding tunnel also sustained damage.

It was originally thought that there had been six, rather than three, explosions on the Underground. The bus bombing brought the reported total to seven; however, this error was corrected later that day. This was because the blasts occurred on trains that were between stations, causing the wounded to emerge from both stations, giving the impression that there was an incident at each station. Police also revised the timings of the tube blasts: initial reports had indicated that they occurred over a period of almost half an hour. This was due to initial confusion at London Underground, where the explosions were initially thought to be due to a power surge. One initial report, in the minutes after the explosions, involved a person under a train, while another concerned a derailment (both of which did actually occur, but only as a result of the explosions). A Code Amber Alert was declared at 09:19, and London Underground began to shut down the network, bringing trains into stations and suspending all services.[3] The effects of the bombs are thought to have varied due to the differing characteristics of the tunnels.[4]

- The Circle Line is a "cut and cover" sub-surface tunnel, about 7 m (21 ft) deep. Because the tunnel contains two parallel tracks, it is relatively wide. The two explosions on this line were probably able to vent their force into the tunnel, reducing their destructive force.

- The Piccadilly Line is a deep tunnel, up to 30 m (100 ft) underground, with narrow (3.5 m, or 11 ft) single-track tubes and just 15 cm (6 in) clearances. This narrow space reflected the blast force, concentrating its effect.

Attack on a double-decker bus

- 09:47 — An explosion occurred in Tavistock Square on a No. 30 Dennis Trident 2 double-decker bus, registration LX03BUF, two years in service at the time, operated by Stagecoach London travelling its route from Marble Arch to Hackney Wick.

Earlier, the bus had passed through the King's Cross area as it travelled from Hackney Wick to Marble Arch. At Marble Arch, the bus turned around and started the return route from Marble Arch to Hackney Wick. It left Marble Arch at 09:00 a.m. and arrived at Euston bus station at 09:35 a.m., where crowds of people had been evacuated from the tube and were boarding buses. The bus was diverted from its normal route by police, allegedly because of road closures in the King's Cross area.[citation needed]. People who had been evacuated from the Underground were continuing to board the bus.[citation needed] At the time of the explosion the bus was travelling through Tavistock Square at the point where it joins Upper Woburn Place.

The explosion ripped the roof off the top deck of the vehicle and destroyed the back of the bus. Witnesses reported seeing "half a bus flying through the air".

The detonation took place close to the British Medical Association building on Upper Woburn Place, and a number of doctors in or near the building were able to provide immediate emergency medical assistance. BBC Radio 5 and The Sun newspaper later reported that two injured bus passengers said that they saw a man exploding in the bus. News reports have identified Hasib Hussain as the person with the bomb on the bus.[5]

The bus bomb exploded towards the rear of the vehicle's top deck, totally destroying that portion of it but leaving the front of the bus intact. Most of the passengers at the front of the top deck are believed to have survived, as did those on the front of the lower deck including the driver, but those at the top and lower rear of the bus took the brunt of the explosion. The extreme physical damage caused to the victims' bodies resulted in a lengthy delay in announcing the death toll from the bombing while the police determined how many bodies were present and whether the bomber was one of them. A number of passers-by were also injured by the explosion and surrounding buildings were damaged by fragments.

Two more suspicious packages were found on underground trains and were destroyed using controlled explosions. Police later said they were not bombs.

Context

The bombings came while the UK was hosting the first full day of the 31st G8 summit, a day after London was chosen to host the 2012 Summer Olympics, two days after the beginning of the trial of fundamentalist cleric Abu Hamza al-Masri, five days after the Live 8 concert, and shortly after the UK had assumed the rotating presidency of the Council of the European Union. The bombings were on the fourth anniversary of the racially-motivated Bradford Riot.

Initial reports

The first reports suggested that a power surge in the Underground power grid had caused explosions in power circuits. This was later ruled out by the National Grid, the power suppliers. Commentators suggested that the explanation had arisen because of bomb damage to power lines along the tracks; the rapid series of power failures caused by the explosions (or power being cut off by means of switches at the locations to permit evacuation) looked similar, from the point of view of a control room operator, to a cascading series of circuit breaker operations that would result from a major power surge.

Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Ian Blair stated within a couple of hours of the explosions that he believed that they were "probably a major terrorist attack." He also indicated that police had found indications of explosives at one of the blast sites, though he would not speculate on who might have carried out the attack. The investigation thus concentrated on possible terrorist suspects.

A couple of hours after the bombings, the then Home Secretary Charles Clarke told the House of Commons of the incidents as terrorist attacks [1]

On the same day as the bombings Peter Power gave two interviews in which he referred to the terror exercise he was running on the morning of 7th July.

Peter Power on Radio 5 Live's Drivetime [2]

The first of Mr Power's interviews was given on the afternoon of 7th July 2005, presumably after Mr Power had finished orchestrating his private terror rehearsal, when he appeared on BBC Radio 5 Live's Drivetime programme. Below is a transcript from the Radio 5 Live programme.

POWER: ...at half-past nine this morning we were actually running an exercise for, er, over, a company of over a thousand people in London based on simultaneous bombs going off precisely at the railway stations where it happened this morning, so I still have the hairs on the back of my neck standing upright!

PETER ALLEN: To get this quite straight, you were running an exercise to see how you would cope with this and it happened while you were running the exercise?

POWER: Precisely, and it was, er, about half-past nine this morning, we planned this for a company and for obvious reasons I don't want to reveal their name but they're listening and they'll know it. And we had a room full of crisis managers for the first time they'd met and so within five minutes we made a pretty rapid decision, 'this is the real one' and so we went through the correct drills of activating crisis management procedures to jump from 'slow time' to 'quick time' thinking and so on.

Power refers to 'simultaneous bombs going off'. Note that it wasn't until 9th July 2005, two days after the incidents, that it was revealed the explosions on the underground were 'almost simultaneous'. Power's fictional scenario, as explained by the man himself on the day, bears a closer resemblance to the eventual story of 7/7 than it does to the actual story that had been presented to the public by the police and authorities at the time of his interview.

Peter Power on ITV News: 7/7 Vision at 20:20

A short while after his appearance on BBC Radio, at 20:20 on 7/7, Peter Power gave a television interview to ITV news. [3]

POWER: Today we were running an exercise for a company - bearing in mind I'm now in the private sector - and we sat everybody down, in the city - 1,000 people involved in the whole organisation - but the crisis team. And the most peculiar thing was, we based our scenario on the simultaneous attacks on an underground and mainline station. So we had to suddenly switch an exercise from 'fictional' to 'real'. And one of the first things is, get that bureau number, when you have a list of people missing, tell them. And it took a long time -

INTERVIEWER: Just to get this right, you were actually working today on an exercise that envisioned virtually this scenario?

POWER: Er, almost precisely. I was up to 2 oclock this morning, because it's our job, my own company. Visor Consultants, we specialise in helping people to get their crisis management response. How do you jump from 'slow time' thinking to 'quick time' doing? And we chose a scenario - with their assistance - which is based on a terrorist attack because they're very close to, er, a property occupied by Jewish businessmen, they're in the city, and there are more American banks in the city than there are in the whole of New York - a logical thing to do. And it, I've still got the hair....

Incidents of 21st July

On 21 July 2005, a second series of four explosions took place on the London Underground and a London bus. The detonators of all four bombs exploded, but none of the main explosive charges detonated, and there were no casualties: the single injury reported at the time was later revealed to be an asthma sufferer. All suspected bombers from this failed attack escaped from the scenes but were later arrested.

Memorial event

On 7 July 2006, the country held a two-minute silence at midday to remember those who died in the bombings a year before. Plaques were unveiled at the tube stations where the bombs exploded and memorial services were held at each scene to pay tribute to the lives lost.

| 2005 London bombings |

|---|

|

Investigation

Initial results

There was initially a great deal of confused information from police sources as to the origin, method, and even timings of the explosions. Forensic examiners had initially thought that military grade plastic explosives were used, and, as the blasts were thought to have been simultaneous, that synchronised timed detonators were employed. This all changed as further information became available. Home-made organic peroxide-based devices were used, according to a May 2006 report from the British government's Intelligence and Security Committee[6]

Fifty-six people, including the four suicide bombers, were killed in the attacks[7] and about 700 were injured, of whom about 100 required overnight hospital treatment or more. The incident was the deadliest single act of terrorism in the United Kingdom since Lockerbie (the 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 which killed 270), and the deadliest bombing in London since the Second World War. More people were killed in the bombings than in any single Provisional IRA attack (in Great Britain or Ireland) during the Troubles.

Police examined about 2,500 items of CCTV footage and forensic evidence from the scenes of the attacks. The bombs were probably placed on the floors of the trains and bus.

Police investigators identified four men whom they alleged had in fact been suicide bombers. This would make the 7 July incident the first suicide bombings in Western Europe.[8] French Interior Minister Nicolas Sarkozy caused consternation at the British Home Office when he briefed the press that one of the names had been described the previous year at an Anglo-French security meeting as an asset of British Intelligence. This was denied by then Home Secretary Charles Clarke, or at any rate he described this as "not his recollection, to say the least".

Vincent Cannistraro, former head of the CIA's anti-terrorism centre, told The Guardian that "two unexploded bombs" were recovered as well as "mechanical timing devices", although this claim was explicitly rejected by the Metropolitan Police.[9]

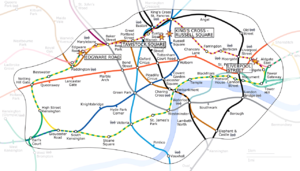

It has been reported that the intention was to have four explosions on the Underground forming a cross of fire with arms in the four cardinal directions, possibly centered symbolically at King's Cross. It was said that one bomber was turned away from the Underground as the explosions had already started, and took a bus instead. It is also speculated that the fourth bomber meant to take the Northern Line. Whilst it has been widely reported that the Northern line was suspended, it was in fact serving all destinations at the time of the attacks, having previously been part suspended because of a faulty train. Northern Line trains were, however, extremely crowded as a result of the earlier disruption.

The Underground bombs exploded when trains were crossing, thus affecting two trains with each explosion. This is one of the features which led rapidly to the suspicion of a terrorist attack by suicide bombers as the cause of the explosions.

Suicide bombings

The four explosions were widely reported as suicide bombings, but at the time the police would only confirm that they believed the bombers died in the bombings. However in the aftermath of the subsequent 21 July 2005 London bombings and the shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes, Sir Ian Blair publicly confirmed that they did believe they were dealing with suicide bombers.[10]

It is not clear why the bombers carried identifying items, which led to the discovery of the bomb factory in Leeds. The bomb factory appears to have been intended for future use and a number of other explosive devices are said to have been found in the bombers' car at Luton station. In addition, the bombers bought return tickets to London from Luton.[11] This has led to speculation that the bombers may have expected to survive the attacks, perhaps having been misled about the time that they had to escape or the nature of the devices that they were carrying.[11]

The first three bombs exploded within 50 seconds of each other, suggesting that a timing device or remote activation was used.[12] It is believed that mobile phones were used to remotely detonate the Madrid train bombs, either by using the phones' alarm function or by calling the phone.[13] The former method would work in the London Underground, but the bombs could not have been detonated by calling the phones as mobile phone signals are not available. As of 19 July 2005, no forensic evidence of either of these mechanisms had been made public, making a manual detonation likely.[14]

No public inquiry

The government has not held a public inquiry, stating that... "it would be a drain on resources and tie up key officials and police officers". Former Prime Minister Tony Blair said an independent inquiry would undermine support for the security service[15] A group of survivors and relatives of those killed are now pursuing legal action in the High Court and European Courts for a full Public Inquiry to clear up conflicting accounts of this day. The Shadow Home Secretary, David Davis said "It is becoming more and more clear that the story presented to the public and parliament is at odds with the facts." [16]

Rumours and conspiracy theories about the July 2005 London bombings

See Rumours and conspiracy theories about the July 2005 London bombings.

The bombers

Identification of bombers

A police press conference on 12 July provided further details on the progress of the investigation. Investigators focused on a group of four men, three of whom were from Leeds, West Yorkshire, and were reported as being primarily cleanskins, meaning previously unknown to authorities. On 7 July 2005, all four travelled to Luton in Bedfordshire by car, then to London by train. They were recorded on CCTV arriving at King's Cross station at about 08:30 a.m. Property associated with the men was found at the site of the explosions. On 12 July the BBC reported that Deputy Assistant Commissioner Peter Clarke, Metropolitan Police counter-terrorism chief, had said that the property of one of the bombers had been found at both the Aldgate and Edgware Road blasts.

Raids

Police raided six properties in the Leeds area on 12 July: two houses in Beeston, two houses in Thornhill, one house in Holbeck and one house in 18 Alexandra Grove, Hyde Park. One man was arrested.

According to West Yorkshire police, a significant amount of explosive material was found in the raids in Leeds and a controlled explosion was carried out at one of the properties. Explosives were also found in the vehicle associated with one of the bombers Shehzad Tanweer at Luton railway station and subjected to controlled explosions.[17][18][19][20]

The police also raided a residential property on Northern Road in the Buckinghamshire town of Aylesbury on 13 July.

Bombers' profiles

The following men are stated to have carried out the attacks:

- Mohammad Sidique Khan (30) - Edgware Road Tube 8.50 a.m. Lived in Dewsbury with his heavily pregnant wife and young child. (Hasina Patel miscarried August 2005).

- Shehzad Tanweer (22) - Aldgate Tube 8.50 a.m. Lived in Leeds with his mother and father working in a fish and chip shop.

- Germaine Lindsay (19) - Russell Square 8.50 a.m. Lived in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire with his pregnant wife.

- Hasib Hussain (18) - Tavistock Square 9.47 a.m. Lived in Leeds with his brother Imran and sister-in-law Shazia.

Luton cell

There has been speculation regarding links between the bombers and another alleged al-Qaeda cell in Luton, Bedfordshire, which was broken up in August 2004. That group was uncovered after al-Qaeda operative Muhammad Naeem Noor Khan was arrested in Lahore, Pakistan. His laptop computer was said to contain plans for tube attacks in London, as well as attacks on financial buildings in New York and Washington. The group was placed under surveillance, but on 2 August 2004 the New York Times published his name, citing Pakistani sources. The leak caused police in Britain and Canada to make arrests before their investigations were complete. The U.S. government later said they had given the name to some journalists as background, for which Tom Ridge, the U.S. homeland security secretary, apologised.

When the Luton cell was broken up, one of the London bombers, Mohammad Sidique Khan (no known relation), was briefly scrutinised by MI5 who determined that he was not a likely threat and he was not put under surveillance.[22]

March 2007 arrests

On 22 March 2007, three men were arrested in connection with the 7/7 bombings. Two men were arrested at 1 pm at Manchester Airport, attempting to board a plane due to depart for Pakistan at around 4.30 pm that afternoon. They were apprehended by undercover officers who had been following the men as part of a surveillance operation. They had not intended to arrest the men that day, but felt they could not risk letting the suspects leave Britain. The other man was arrested in the Beeston area of Leeds, West Yorkshire, at an address on the street where one of the suicide bombers had lived before the attacks.[23]

May 2007 arrests

On 9 May2007 police made four further arrests, three in Yorkshire and one in Selly Oak, Birmingham. Hasina Patel, widow of the presumed ringleader Mohammed Sidique Khan, was among those arrested for "commissioning, preparing or instigating acts of terrorism". [24].

Three of those arrested, including Patel, were released on 15 May2007.[25] The fourth, Khalid Khaliq, an unemployed single father of three, was charged with possessing an al-Qaeda training manual on 17 July 2005, but this charge was not related to the 7 July bombing. The possession of a document containing information likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism carries a maximum 10-year jail sentence.[26]

Deportation of Sheikh Abdullah el-Faisal

Sheikh Abdullah el-Faisal was deported to his country of origin, Jamaica, from Britain on Friday May 25,2006 after reaching the parole date in his prison sentence. He was found guilty of three charges of soliciting the murder of Jews, Americans and Hindus and two charges of using threatening words to stir up racial hatred in 2003 and after his appeal was sentenced to seven years in prison. In 2006 John Reid told MPs that el-Faisal had influenced Jamaican-born Briton Germaine Lindsay. [27][28]

Claims of responsibility

At around 12:10 p.m. on 7 July, BBC News reported that a website known to be operated by associates of al-Qaeda had been located with a 200-word statement claiming responsibility for the attacks. The news magazine Der Spiegel in Germany and BBC Monitoring both reported that a group named "Secret Organisation — al-Qaeda in Europe" had posted an announcement claiming responsibility on the al-Qal3ah ("The Castle") Internet forum.[29] The announcement claims the attacks are a response due to the British involvement in the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan. The letter also warned other governments involved in Iraq (mentioning specifically Denmark and Italy) to withdraw troops from Iraq and Afghanistan. A Saudi commentator in London noted that the statement was grammatically poor, and that a Qur'anic quotation was incorrect. This has been disputed.[30]

The attacks bear similarities to the 11 March 2004 Madrid train bombings and suggest an attack in the style of al-Qaeda. Budapest-based security analyst Sebestyén Gorka told the Reuters wire service that "the first thing that's very obvious is the synchronised nature of the attacks, and that's pretty classic for Al-Qaeda or organisations related to al-Qaeda".

In the opinion of former Metropolitan Police Commissioner Lord Stevens of Kirkwhelpington, before the identity of the bombers became known, the bombers were almost certainly born or based in Britain.[31] The attacks would have required extensive preparation and prior reconnaissance efforts, and a familiarity with bomb-making and the London transport network as well as access to significant amounts of bomb-making equipment and chemicals.

Some newspaper editorials in Iran have blamed the bombing on British or American authorities seeking to further justify their War on Terrorism, and have claimed that the plan that included the bombings also involved increasing harassment of Muslims in Europe.[32]

On 13 August 2005 The Independent newspaper reported, quoting police and MI5 sources, that the 7 July bombers acted independently of an al-Qaeda terror mastermind someplace abroad.[33]

On 1 September 2005, al-Qaeda officially claimed responsibility for the attacks in a videotape aired on the Arab television network al Jazeera.

An official inquiry by the British government reported that the tape claiming responsibility had been edited after the attacks, and that the bombers had no direct support from al Qaeda[34].

Translated statement

Within hours after the attack, someone using the name "Nur al-Iman" and identified as a "new guest", posted a statement on the Al-Qal3ah website which claimed responsibility on behalf of "The Secret Organisation Group of Al-Qaeda of Jihad Organisation in Europe". The following is a translation of the statement:

- In the name of God, the merciful, the compassionate, may peace be upon the cheerful one and undaunted fighter, Prophet Muhammad, Allah's peace be upon him.

- Nations of Islam and Arab nations: Rejoice, for it is time to take revenge against the British Zionist crusader government in retaliation for the massacres Britain is committing in Iraq and Afghanistan. The heroic Mujahideen [holy warriors] have carried out a blessed raid [ghazw] in London. Britain is now burning with fear, terror and panic in its northern, southern, eastern, and western quarters.

- We have repeatedly warned the British government and people. We have fulfilled our promise and carried out our blessed military raid in Britain after our Mujahideen exerted strenuous efforts over a long period of time to ensure the success of the raid.

- We continue to warn the governments of Denmark and Italy and all the crusader governments that they will be punished in the same way if they do not withdraw their troops from Iraq and Afghanistan. He who warns is excused.

- Allah says: "If ye will aid (the cause of) Allah, He will aid you, and plant your feet firmly"

The quotation at the end of the statement is from the Qur'an, in Sura 47:7. The translation of the quotation given here is by Abdullah Yusuf Ali.

The term ghazw, here translated as "raid", has historically often been used in Islamic contexts with the connotations of an attack on the enemies of an Islamic state seen as a meritorious act; those who carry out such attacks (ghazawat) are called ghazis.

This anonymous post has come under dispute as MSNBC TV translator Jacob Keryakes noted that the claim of responsibility contained an error in one of the Quranic verses it cited. That suggests that the claim may be phony, he said. "This is not something al-Qaida would do," he said.[35]

Abu Hafs al-Masri Brigade

A second claim of responsibility was posted on the Internet on 9 July, claiming the attacks for another Al Qaeda-linked group, Abu Hafs al-Masri Brigade. The group has previously falsely claimed responsibility for events that were the result of technical problems, such as the 2003 London blackout and 2003 North America blackout.[36] They have also claimed authorship of the 2004 Madrid train bombings.

Tape of Mohammad Sidique Khan

On 1 September 2005, Al Jazeera aired a tape featuring Mohammad Sidique Khan, one of the bombers, in which he said:

- I and thousands like me are forsaking everything for what we believe. Our drive and motivation doesn't come from tangible commodities that this world has to offer. Our religion is Islam, obedience to the one true God and following the footsteps of the final prophet messenger.

- Your democratically elected governments continuously perpetuate atrocities against my people all over the world. And your support of them makes you directly responsible, just as I am directly responsible for protecting and avenging my Muslim brothers and sisters.

- Until we feel security you will be our targets and until you stop the bombing, gassing, imprisonment and torture of my people we will not stop this fight. We are at war and I am a soldier. Now you too will taste the reality of this situation.

The tape had been edited and also featured Al Qaeda number two, Ayman al-Zawahiri, in a way intended to suggest a direct link between Khan and Al Qaeda. There has been no report that Khan said anything linking the bombing to Al Qaeda.

A more complete transcription of the tape is available at Wikisource.

Effects

Security alerts

Although there were security alerts at many locations, no other terrorist incidents occurred outside central London. Suspicious packages were destroyed in controlled explosions in Edinburgh, Brighton, Coventry, Southampton, Portsmouth and Darlington. Security across the UK was raised to the highest alert level.

Many other countries raised their own terror alert status (for example: Canada, United States, France, and Germany), especially for public transport. For a time US commanders ordered troops based in the UK to avoid London.

Police sniper units were reported to be following as many as a dozen Al Qaeda suspects in Britain. The covert armed teams were under orders to shoot to kill if surveillance suggested that a terror suspect was carrying a bomb and he refused to surrender if challenged.[37]

Transport and telecoms disruption

AVOID LONDON

AREA CLOSED

TURN ON RADIO

Vodafone reported that its mobile phone network reached capacity at about 10:00 a.m. on the day of the incident, and it was forced to initiate emergency procedures to prioritise emergency calls (ACCOLC, the "access overload control scheme"). Other mobile phone networks also reported failures. The BBC speculated that the phone system was closed by the security services to prevent the possibility of mobile phones being used to trigger bombs. Although this option was considered, it later became clear that the intermittent unavailability of both mobile and landline phone systems were due to excessive usage.

For most of the day, central London's public transport system was effectively crippled because of the complete closure of the underground system, the closure of the Zone 1 bus networks, and the evacuation of Russell Square. Bus services restarted at 4 p.m. the same day, and most mainline train stations reopened shortly after. Tourist river vessels were pressed into service to provide a free alternative to the overcrowded trains and buses. Thousands of people chose to walk home or make their way to the nearest Zone 2 bus or train station. Most of the Underground apart from the affected stations restarted the next morning, though some commuters chose to stay at home.

Much of King's Cross station was also closed, with the ticket hall and waiting area being used as a makeshift hospital to treat casualties on the spot. Although the station reopened later in the day, only suburban rail services were able to use it, with GNER trains terminating at Peterborough (the service was fully restored on 9 July). King's Cross St. Pancras tube station remained open only to Metropolitan Line services in order to facilitate the ongoing recovery and investigation effort for a week, though Victoria Line services were restored on 15 July and Northern Line services on 18 July. St. Pancras Station, located next to King's Cross, was shut on Thursday afternoon with all Midland Mainline trains terminating in Leicester disrupting services to Sheffield, Nottingham and Derby.

By 25 July there were still disruptions to the Piccadilly Line (which was not running between Arnos Grove and Hyde Park Corner in either direction), the Hammersmith & City Line (which was only running a shuttle service between Hammersmith and Paddington) and the Circle Line (which was suspended in its entirety). The Metropolitan line resumed services to between Moorgate and Aldgate on 25 July. The Hammersmith and City was also operating a peak hours service between Whitechapel and Baker Street. Most of the tube network was however running normally.

On 2 August the Hammersmith & City Line resumed normal service; the Circle Line service was still suspended, though all Circle Line stations are also served by other lines. The Piccadilly Line service resumed on 4 August.

Economic impact

There were limited immediate reactions to the attack in the world economy as measured by financial market and exchange rate activity. The pound fell 0.89 cents to a 19-month low against the U.S. dollar. The FTSE 100 Index fell by about 200 points in the two hours after the first attack. This was its biggest fall since the start of the war in Iraq, and it triggered the London Stock Exchange's special measures, restricting panic selling and aimed at ensuring market stability. However, by the time the market closed it had recovered to only 71.3 points (1.36%) down on the previous day's three-year closing high. Markets in France, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain also closed about 1% down on the day.

US market indexes rose slightly, in part because the dollar index rose sharply against the pound and the euro. The Dow Jones Industrial Average gained 31.61 to 10,302.29. The Nasdaq Composite Index rose 7.01 to 2075.66. The S&P 500 rose 2.93 points to 1197.87 after declining up to 1%. Every benchmark gained 0.3%.[38]

The markets picked up again on 8 July as it became clear that the damage caused by the bombings was not as great as initially thought. By close of trading the market had fully recovered to above its level at start of trading on 7 July. Insurers in the UK tend to re-insure their terrorist liabilities in excess of the first £75,000,000 with Pool Re, a mutual insurer set up by the government with leading insurers. Pool Re has substantial reserves and newspaper reports indicated that claims would easily be covered.

On 9 July, the Bank of England, HM Treasury and the Financial Services Authority revealed that they had instigated contingency plans immediately after the attacks to ensure that the UK financial markets could keep trading. This involved the activation of a "secret chatroom" on the British Government's Financial Sector Continuity website, which allowed the institutions to communicate with the country's banks and market dealers.[39]

Response

Media response

Rolling news coverage of the attacks was broadcast throughout 7 July, by both BBC One and ITV1 uninterrupted until 7pm. Sky News did not carry any advertisements for 24 hours. ITN later confirmed that its coverage on ITV1 was its longest uninterrupted on-air broadcast in its 50 year history. Television coverage was notable for the use of mobile phone video sent in from members of the public and live shots from traffic CCTV cameras. Local and national radio also generally either suspended regular programming for news reports, or provided regular updates as part of scheduled shows.

Many films and drama broadcasts were cancelled or postponed on grounds of taste. For example, BBC Radio 4 pulled its scheduled Classic Serial without explanation; it was to have been John Buchan's Greenmantle, about the revolt of Muslims against British interests abroad. ITV replaced the movies The X Files, in which a building is partly destroyed by a bomb, with Stakeout, and The Siege, where a bomb destroys a bus full of passengers, with Gone in 60 Seconds. Even the BBC flagship soap EastEnders was forced to re-edit that night's episode, which contained a sequence involving a house explosion, ambulances and survivors choking from smoke inhalation. Big Brother 2005 that was going on at the time decided against telling the housemates of the day's attacks after the producers found out that all relatives and friends of the housemates were well. Sky One broadcast an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation in place of Terror Attacks: Could You Survive ...?. Also, Viacom-owned music channels MTV, VH1, TMF and all their sub-channels broadcasted a 'sombre' music playlist for the rest of the day, and into some of the next (the MTV studios were situated in Camden Town, close to some of the bomb sites). A two-part episode of CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, directed by Quentin Tarantino and concerning a suicide bomber, and being trapped underground, due to be shown on 12 July on Five, was postponed for a week.

The bbc.co.uk website recorded an all time bandwidth peak of 11 Gb/s at 12:00 on 7 July. BBC News received some 1 billion total hits on the day of the event (including all images, text and HTML), serving some 5.5 terabytes of data. At peak times during the day there were 40,000 page requests per second for the BBC News website. The previous day's announcement of the 2012 Olympics being awarded to London caused a peak of around 5 Gb/s. The previous all time high at bbc.co.uk was caused by the announcement of the Michael Jackson verdict, which used 7.2 Gb/s.[40]

On Tuesday 12 July it was reported that the far-right political party, the British National Party, released leaflets showing images of the "Number 30 Bus" after it was blown up. The slogan "Maybe now it's time to start listening to the BNP" was printed beside the photo. Then Home Secretary Charles Clarke described it as an attempt by the BNP to, "cynically exploit the current tragic events in London to further their spread of hatred".[41] In several countries outside the United Kingdom, governments and media outlets perceived that the UK government was lenient towards radical Islamist militants (as long as they were involved in activities outside of the UK), as well as the UK's refusal to extradite or prosecute suspects of terror acts committed outside of the UK, led to London being sometimes called Londonistan, and have called these purported policies into question (New York Times, Le Figaro). Such policies were believed to be a cynical attempt of quid pro quo: the UK allegedly exchanged an absence of attacks on its soil against toleration.

Leaked report in The Observer

On 9 April 2006 The Observer newspaper published leaked details of the first draft of a forthcoming Home Office report on the bombings, compiled for the then Home secretary Charles Clarke by a senior civil servant.[42] This section includes only information about a forthcoming report gleaned from a newspaper article, and should be read as such rather than as verified fact.

The article reports that the attack was planned probably with a budget of only a few hundred pounds by four men using information from the internet. While they had visited Pakistan, there was no direct support or planning by al-Qaeda; meetings in Pakistan were ideological, rather than practical. All four bombers died in the suicide bombings. While there was a search for a fifth suspect after police found an unused rucksack of explosives in the bombers' abandoned car at Luton station, there was no fifth bomber.

While the videotape of Mohammed Sidique Khan released after the attacks had footage of Osama bin Laden's deputy, Ayman al-Zawahiri, the Home Office believes the tape was edited after the suicide attacks and dismisses it as evidence of al-Qaeda's involvement in the attacks.

Khan was the ringleader. Links to other suspected terrorists are not discussed for legal reasons. The bombers-to-be followed an extreme interpretation of Islam, and they, in particular Jermaine Lindsay, were happy to enjoy a Western lifestyle. The attacks were largely motivated by concerns over British foreign policy, seen as deliberately anti-Muslim, and the promise of immortality.

The report does not say why no action was taken against the suspect bombers beforehand, although Mohammed Sidique Khan was identified by intelligence officers months before the attack. A separate report into the attacks by the Commons intelligence and security committee will ask why MI5 did not maintain surveillance of Khan.

Criticism of the leaked Observer report

Conservative spokesman Patrick Mercer said 'A series of reports such as this narrative simply does not answer questions such as the reduced terror alert before the attack, the apparent involvement of al-Qaeda and links to earlier or later terrorist plots.'

Investigation of the ringleader, Mohammad Sidique Khan

The Guardian Unlimited in its May 3 2007 edition said the that police investigated ringleader Mohammad Sidique Khan twice in 2005. The paper said it "learned that on January 27 2005, police took a statement from the manager of a garage in Leeds which had loaned Khan a courtesy car while his vehicle was being repaired. It also said that "On the afternoon of February 3 an officer from Scotland Yard's anti-terrorism branch carried out inquiries with the company which had insured a car in which Khan was seen driving almost a year earlier". Nothing about these inquiries appeared in the report by parliament's intelligence and security committee after it investigated the 7 July attacks. Scotland Yard described the 2005 inquiries as "routine", while security sources said they were related to the fertiliser bomb plot.

Victims

The 52 known victims of the 7/7 bombings are listed below. For further information on those involved and injured see here; for images of the victims listed below, follow the link [4].

King's Cross bomb

- James Adams, 32, a mortgage broker who was travelling from his home in Peterborough to London through King's Cross from where he called his mother.

- Samantha Badham, 36, had taken the Tube with her partner, Lee Harris. The couple usually cycled to work but caught the Tube because they were planning a romantic dinner to celebrate their 14th anniversary.

- Lee Harris, 30, an architect who died after receiving treatment at the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel, east London. His partner, Samantha Badham, also died in the attacks.

- Phil Beer, 22, a hair stylist, was on his way to work at the Sanrizz salon in Knightsbridge with his best friend, Patrick Barnes, who was injured.

- Anna Brandt, 42, a Polish cleaner living in Wood Green.

- Ciaran Cassidy, 22, of Upper Holloway, north London.

- Elizabeth Daplyn, 26, an administrator at University College Hospital in London, left home in Highgate with her partner, Rob Brennan, before taking a Piccadilly Line train.

- Arthur Edlin Frederick, 60, of Seven Sisters, north London.

- Karolina Gluck, 29, from Poland, said goodbye to boyfriend, Richard Deer, 28, at 8.30am. The IT consultant was travelling from Finsbury Park to Russell Square.

- Gamze Günoral, 24, a Turkish student, left her aunt’s house in north London to catch the tube to go to her language college in Hammersmith.

- Ojara Ikeagwu, 55, a married mother-of-three from Luton, was on her way to Hounslow where she was a social worker.

- Emily Jenkins, 24, from Richmond.

- Adrian Johnson, 37, a keen golfer and hockey-player with two young children. He was on his way to work at the Burberry fashion house in Haymarket where he was a product technical manager.

- Helen Jones, 28, a Scottish (London-based) accountant who had previously escaped death in 1988 when wreckage of Pan Am Flight 103 crashed upon Lockerbie. Her family, from Annan, Dumfries and Galloway, said: "Helen will live on in the hearts of her family and her many, many friends".

- Susan Levy, 53, from Cuffley in Hertfordshire, the mother of Daniel, 25, and James, 23. She had just said goodbye to her younger son.

- Shelley Mather, 26, from New Zealand

- Michael Matsushita, 37, left his fiancee, Rosie Cowen, 28, at the couple's flat in Islington for his second day at work as a tour guide.

- James Mayes, 28, worked as an analyst for the Healthcare Commission and had just returned from a holiday in Prague. He was heading from his home in Barnsbury to an ‘away day’ at Lincoln’s Inn and was thought to be travelling by Tube via King's Cross.

- Behnaz Mozakka, 47, a biomedical records officer from Finchley who worked at Great Ormond Street Childrens Hospital.

- Mihaela Otto, 46, from Romania, known as Michelle. A dental technician of Mill Hill, north London, who was killed at King's Cross.

- Atique Sharifi, 24, an Afghan national who was living in Hounslow, Middlesex.

- Ihab Slimane, a 24-year-old waiter from Paris who was working at a restaurant near Piccadilly Circus, was said by friends to have caught a Tube from Finsbury Park.

- Christian 'Njoya' Small, 28, an advertising salesman from Walthamstow, east London.

- Monika Suchocka, 23, from northern Poland, arrived in London two months earlier to start work as a trainee accountant in West Kensington.

- Mala Trivedi, 51, from Wembley was manager of the X-ray department at Great Ormond Street Childrens Hospital.

- Rachelle Chung For Yuen, 27, an accountant from Mill Hill, north London, who was originally from Mauritius.

Edgware Road bomb

- Michael Stanley Brewster, 52, a father of two who was travelling to work from Derby.

- Jonathan Downey, 34, an HR systems development officer with the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea from Milton Keynes, had just said goodbye to his wife at Euston .

- David Foulkes, 22, a media sales worker from Oldham, Lancashire, was on his way to meet a colleague.

- Colin Morley, 52, of Finchley, he used his brilliant communication skills to try to help charities and businesses understand their brand and, on a wider scale, he tried to change the world of media and marketing into a force for social good.

- Jenny Nicholson, 24, daughter of a Bristol vicar, who had just started work at a music company in London

- Laura Webb, 29, from Islington, a PA.

Aldgate bomb

- Lee Baisden, 34, an accountant from Romford who was going to work at the London Fire Brigade.

- Benedetta Ciaccia, 30, an Italian-born business analyst from Norwich.

- Richard Ellery, 21, was travelling from his home in Ipswich to his job in the Jessops store in Kensington, via Liverpool Street Station. He texted his parents, Beverley and Trevor, at 8.30am to say he was on his way to work.

- Richard Gray, 41, a tax manager from Ipswich.

- Anne Moffat, 48, from Harlow in Essex, who was head of marketing and communications for Girlguiding UK.

- Fiona Stevenson, 29, a solicitor who lived at the Barbican, London. Her parents, Ivan and Eimar, of Little Baddow, Essex, described her as "irreplaceable".

- Carrie Taylor, a 24-year-old graduate from Billericay, Essex. June Taylor, her mother, said: "We have a little farewell ritual. Carrie gives me a kiss goodbye".

Tavistock Square bus bomb

- Anthony Fatayi-Williams, 26, an Nigerian-born executive with an oil and gas company based in Old Street, had been living in the UK for eight years.

- Jamie Gordon, 30, from Enfield, worked for City Asset Management and was engaged to be married to his girlfriend Yvonne Nash.

- Giles Hart, 55, a BT engineer from Hornchurch and father-of-two, was travelling to Angel via Aldgate.

- Marie Hartley, 34, from Oswaldtwistle, Lancashire, was in London on a course.

- Miriam Hyman, 32, from Barnet, North London, a picture researcher. She had spoken to her father by phone after being evacuated from King's Cross station and reassured him that she was all right.

- Shahara Akther Islam, 20, from Plaistow, East London, a bank cashier who lived with her parents, and was both fully Westernised and a devout Muslim.

- Neetu Jain, 37, was evacuated from Euston and caught the bus to take her to work as a computer analyst. Ms Jain was planning to move in with her boyfriend, Gous Ali.

- Sam Ly, 28, from Melbourne, died at the National Hospital of Neurology - the only fatality of ten Australians caught in the bombing.

- Shyanuja Parathasangary, 30, a Post Office worker travelling from Kensal Rise to Alder Street.

- Anat Rosenberg, 39, an Israeli-born charity worker who called her boyfriend to tell him she was on the Number 30 bus moments before the blast. John Falding, 62, her boyfriend, said: "She was afraid of going back to Israel because she was scared of suicide bombings on buses".

- Philip Russell, a 28-year-old finance worker at JP Morgan who lived at Kennington in South-East London.

- William Wise, 54 , an IT specialist at Equitas Holdings in St Mary Axe.

- Gladys Wundowa, 50, from Ilford in Essex, a cleaner at University College London. She had finished her shift and was heading to a college course in Shoreditch. Her body was taken to her homeland of Ghana for burial.

Historical comparisons

The bombings were the deadliest attack in London since a V2 rocket killed 131 people in Stepney on 27 March 1945, near the end of World War II. They were the deadliest post-World War II incident in the capital since the Great Smog of 1952 that killed 4,000 people.

They were the second-deadliest terrorist attack in the UK, after the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland (270 dead). Other terrorist bombings in recent history include the 1998 Omagh bombing (29 dead) and the 1974 Birmingham pub bombings (21 dead). The 2005 attacks are the first coordinated suicide bombings perpetrated by Islamic Extremists in the history of London. The three train bombings, with a total of 39 dead, constitute one of the deadliest incidents in the peacetime history of the London Underground, with more casualties than the King's Cross fire of November 1987 (31 dead), but fewer than the Moorgate tube crash of February 1975 (43 dead) and the wartime bombings of Balham station (14 October 1940) - 65 dead, and Bank station (11 January 1941) - 56 dead, or the panic crush during an air raid at Bethnal Green station on 3 March 1943 when 173 people lost their lives.

The London Underground had been targeted by bombers before. In January 1885 a bomb exploded on a Metropolitan Line train at Gower Street (now Euston Square) station, and in February 1913 a crude bomb - probably the work of Suffragettes - was discovered at Westbourne Park station. Bombs planted by the Irish Republican Army (IRA) exploded at Tottenham Court Road and Leicester Square station on 3 February 1939. In August and December 1973 the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) left several explosive devices in the tube network, and again in February and March 1976. On 4 March 1976, eight people were injured by a bomb in Cannon Street; 11 days later, nine people were injured by a premature explosion at West Ham tube station. Seconds after that incident, Julius Stephen, the driver of the train, was shot dead when he attempted to pursue the fleeing bomber. On the same day, a further device found at Oxford Circus station was defused, while on March 18 another bomb exploded on an empty train at Wood Green station as it was preparing to enter the reversing siding there.[43]

The 2005 attack featured the most explosions in a single terrorist incident in a UK city since Bloody Friday in Belfast in July 1972 (22 bombs planted). They were the world's deadliest attack on a public transport system since the Madrid train bombings of 11 March 2004 (191 dead), although the March 1995 Sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway injured far more people.

There has only been one other bomb explosion on a London bus in recent times: on 18 February 1996 at Wellington Street near Aldwych, in which the only fatality was the IRA member transporting the device. This was thought to have been the result of the accidental detonation of a bomb that he intended to plant elsewhere, rather than a suicide attack.

The 2005 attacks were the first terrorist (i.e. politically motivated) killings in London since 30 April 1999, when the neo-Nazi David Copeland nailbombed the Admiral Duncan pub in Soho in a homophobic attack, killing three people. They were also the first suicide bombings carried out anywhere in Western Europe.

In 1995, the GIA Islamist militant group staged a series of attacks against the French public, targeting public transportation. These attacks killed 8 and injured more than 100. The attacks were apparently designed to be a broadening of the civil war in Algeria, a former French colony.

Contacts

- People with information regarding the bombings were asked to report it to the Home Office anti-terrorist hotline 0800 789 321 (UK).[44]

- Scotland Yard requested that members of the public with video or images on mobile phones or otherwise send them to images@met.police.uk.

- British Red Cross website for donations to the victims relief fund.

- The police force with responsibility for London Underground is the British Transport Police.

See also

- Response to the 2005 London bombings

- 7 July 2005 London bombings memorials and services

- Rumours and conspiracy theories about the July 2005 London bombings

- Jean Charles de Menezes

- 21 July 2005 London bombings

- COBRA

- 1995 bombings in France

- 11 March 2004 Madrid train bombings

- 11 July 2006 Mumbai train bombings

- 2006 transatlantic aircraft plot

- 2007 London car bombs

- 2007 Glasgow International Airport attack

References

- ^ "I'm lucky to be here, says driver". BBC. 2005-07-11. Retrieved 2006-11-12.

- ^ North, Rachel (2005-07-15). "Coming together as a city". BBC. Retrieved 2006-11-12.

- ^ "Tube log shows initial confusion". BBC. 2005-07-12. Retrieved 2006-11-12.

- ^ Bbc News | Indepth | London Attacks

- ^ Duncan Campbell and Sandra Laville (2005-07-13). "British suicide bombers carried out London attacks, say police". The Guardian. Retrieved 2006-11-15.

- ^ Intelligence and Security Committee (May 2006). "Report into the London Terrorist Attacks on 7 July 2005" (PDF). pp. p. 11.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "List of the bomb blast victims". BBC News. 2005-07-20. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ^ Eggen, Dan (2005-07-17). "Suicide Bombs Potent Tools of Terrorists". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Muir, Hugh (2005-07-08). "Four bombs in 50 minutes - Britain suffers its worst-ever terror attack". The Guardian. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Transcript: Interview with Sir Ian Blair". Sunday with Adam Boulton. Sky News. 2005-07-24. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ a b Edwards, Jeff (2005-07-16). "Exclusive: Was It Suicide?". The Daily Mirror. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ "Tube bombs "almost simultaneous"". BBC News. 2005-07-09. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ "La bolsa bomba que no explotó". Elmundo. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ Bennetto, Jason (2005-07-19). "Revealed: suicide bombers flew together to Karachi". The Independent. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ 7/7 leader: more evidence reveals what police knew The Guardian May 3 2007

- ^ Dodd, Vikram (2007-05-03). "7/7 leader: more evidence reveals what police knew". The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ "London bombers "were all British"". BBC News. 2005-07-12. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ "One London bomber died in blast". BBC News. 2005-07-12. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (2005-07-13). "British suicide bombers carried out London attacks, say police". The Guardian. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bennetto, Jason (2005-07-13). "The suicide bomb plot hatched in Yorkshire". The Independent. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Image of bombers' deadly journey". BBC News. 2005-07-17. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ Leppard, David (2005-07-17). "MI5 judged bomber "no threat"". The Times Online. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ "Three held over 7 July bombings".

- ^ "Three held over 7 July bombings".

- ^ "Police release 7/7 bomber's widow".

- ^ BBC NEWS | UK | Man bailed over 'al-Qaeda manual'

- ^ BBC NEWS | UK | Race hate cleric Faisal deported

- ^ BBC NEWS | England | London | 'Hate preacher' loses his appeal

- ^ Link to www.qal3ati.com on The Internet Archive

- ^ Cole, Juan (2005-07-09). "Update on London Bombing Investigation. Cole: Unlikely to be by British Muslims". Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ "Police appeal for bombing footage". BBC News. 2005-07-10. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ "Iran press blames West for blasts". BBC News. 2005-07-11. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ Bennetto, Jason (2005-08-13). "London bombings: the truth emerges". The Independent. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Leak reveals official story of London bombings | UK news | The Observer

- ^ "Islamic group claims London attack". MSNBC. 2005-07-07. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ Johnston, Chris (2005-07-09). "Tube blasts "almost simultaneous"". The Guardian. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ "Police snipers track al-Qaeda suspects". The Times Online. 2005-07-17. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ Lawrence, Dune (2005-07-07). "U.S. Stocks Rise, Erasing Losses on London Bombings; Gap Rises". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ "Banks talked via secret chatroom". BBC News. 2005-07-08. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ "Statistics on BBC Webservers 7th July 2005". BBC Online. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ BBC NEWS | Politics | BNP campaign uses bus bomb photo

- ^ Townsend, Mark (2006-04-09). "Leak reveals official story of London bombings". The Guardian. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ Jenkins, Brian Michael (December 1997). "Protecting Surface Transportation Systems and Patrons from Attacks - A Chronology of Attacks" (PDF). International Institute for Surface Transportation Policy Studies. pp. p.118.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ ""One week anniversary" bombings appeal". 2005-07-14. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

External links

Support

Official reports

- Greater London Authority report (PDF)

- House of Commons report (PDF)

- Intelligence and Security Committee report (PDF)

Police statements

- London Metropolitan Police Police investigation continues into the 7/7 bombings. Retrieved July 18 2005

- London Metropolitan Police press conference. Retrieved July 14 2005

Medical report

- The account of the doctor leading the team at the scene of the Tavistock Square bus bomb. Retrieved August 11 2005

News articles

- BBC In-depth report. Retrieved July 12 2005.

- BBC Animated overview of events. Retrieved July 2005.

- BBC London blasts: At a glance. Retrieved July 12 2005.

- BBC BBC News - 'Long-term scars' of London bombs - 30/11/06

- The Cambridge Evening News London terror attack: The CEN Online blog. 7 July 2005.

- The London News Review A Letter To The Terrorists, From London. Retrieved 7 July 2005.

- The Times Online Controlled explosion at home raided by anti-terror police. Retrieved 12 July 2005.

- BBC Online UK Holds two minutes silence to remember the victims. Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- Fire Brigade operations - London Fire Journal

- archive of newspaper front pages world wide following attack

Radio broadcasts

- The Jon Gaunt show originally broadcast live at 9:00 a.m. on 7 July 2005 on BBC London.

Memoirs

- Memoirs of the Subway Bombings - From MemoryWiki.

Tributes and obituaries

- Tributes to those who died with portrait photographs

- Obituaries

Remembrance

- National Day of Tolerance Petition from Tolerance International UK to make 7th July National Day of Tolerance in Britain.

- Department for Culture, Media and Sport Two minutes of silence on the first anniversary of 7th July 2005.

Photos and videos

- http://www.abuhamza.org.uk video about 7/7 by al-qaeda

- Video statement by the bomber Shehzad Tanweer

- Swedish newspaper Aftonbladet writes about posters honouring the terrorists [5]