Socialism

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. |

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

Socialism is an economic and political theory advocating public or common ownership and cooperative management of the means of production and allocation of resources.[1][2][3]

The theory of true socialism is to have no social classes. However, that means that there would be no higher class in government. Socialism revolves around the community unit where everyone contributes. Although, this would never work because human nature cannot follow a peaceful existence in a community. Man's true nature involves sin. Since there would be no government, sin would take control over men, causing anarchy to set in. The theory is supposed to work but it would not if put into practice. In a socialist economic system, production is carried out by a free association of workers to directly maximise use-values (instead of indirectly producing use-value through maximising exchange-values), through coordinated planning of investment decisions, distribution of surplus, and the means of production. Socialism is a set of social and economic arrangements based on a post-monetary system of calculation, such as labour time, energy units or calculation-in-kind; at least for the factors of production.[4]

Socialists advocate a method of compensation based on individual merit or the amount of labour one contributes to society.[5] They generally share the view that capitalism unfairly concentrates power and wealth within a small segment of society that controls capital and derives its wealth through a system of exploitation. They argue that this creates an unequal society that fails to provide equal opportunities for everyone to maximise their potential,[6] and does not utilise technology and resources to their maximum potential in the interests of the public.[7] Socialists characterise full socialism as a society no longer based on coercive wage-labour, organized on the basis of relatively equal power-relations and adhocracy rather than hierarchical, bureaucratic forms of organization in the productive sphere. Reformists and revolutionary socialists disagree on how a socialist economy should be established.

Modern socialism originated in the late 18th-century intellectual and working class political movement that criticised the effects of industrialisation and private property on society. Utopian socialists such as Robert Owen (1771–1858), tried to found self-sustaining communes by secession from a capitalist society. Henri de Saint Simon (1760–1825), who coined the term socialisme, advocated technocracy and industrial planning.[8] Saint-Simon, Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx advocated the creation of a society that allows for the widespread application of modern technology to rationalise economic activity by eliminating the anarchy of capitalist production.[9][10] They argued that this would allow for economic output (or surplus value) and power to be distributed based on the amount of work expended in production.

Some socialists advocate complete nationalisation of the means of production, distribution, and exchange, while others advocate state control of capital within the framework of a market economy. Socialists inspired by the Soviet model of economic development have advocated the creation of centrally planned economies directed by a state that owns all the means of production. Others, including Yugoslavian, Hungarian, East German and Chinese communist governments in the 1970s and 1980s, instituted various forms of market socialism, combining co-operative and state ownership models with the free market exchange and free price system (but not free prices for the means of production).[11]

Libertarian socialists (including social anarchists and libertarian Marxists) reject state control and ownership of the economy altogether, and advocate direct collective ownership of the means of production via co-operative workers' councils and workplace democracy.

Contemporary social democrats propose selective nationalisation of key national industries in mixed economies, while maintaining private ownership of capital and private business enterprise.

Economics

Economically, socialism denotes an economic system of either state ownership and/or worker ownership and administration of the means of production, and management over the allocation of producer goods and the means of production. Public or worker ownership can refer to nationalisation, municipalisation, the establishment of cooperative enterprises or in some cases direct-worker ownership. The fundamental feature of a socialist economy is that publicly owned, state or worker-run institutions produce goods and services in at least the commanding heights of the economy.[12][13]

An economic goal of socialism is to more effectively satisfy demand by producing utility directly without being burdened by private property relations in the means of production and the need to generate profit, which socialists generally view as being remnants of a defunct mode of production and an impediment to contemporary productive capabilities.

Various differing definitions of what constitutes a socialist economy exist, from those that define it as an entirely post-market and moneyless economy, to those that simply define it as publicly-owned and cooperative enterprises in a mixed-market or free-market economy.

"I am convinced there is only one way to eliminate (the) grave evils (of capitalism), namely through the establishment of a socialist economy, accompanied by an educational system which would be oriented toward social goals. In such an economy, the means of production are owned by society itself and are utilized in a planned fashion. A planned economy, which adjusts production to the needs of the community, would distribute the work to be done among all those able to work and would guarantee a livelihood to every man, woman, and child. The education of the individual, in addition to promoting his own innate abilities, would attempt to develop in him a sense of responsibility for his fellow-men in place of the glorification of power and success in our present society."

Albert Einstein, Why Socialism?, 1949 [14]

Planned economy

This form of socialism combines public ownership and management of the means of production with centralised state planning, and can refer to a broad range of economic systems from the centralised Soviet-style command economy to participatory planning via workplace democracy. In a centrally planned economy, decisions regarding the quantity of goods and services to be produced as well as the allocation of output (distribution of goods and services) are planned in advance by a planning agency. This type of economic system was often combined with a single-party political system, and is thus associated with the Communist states of the 20th century.

In the economy of the Soviet Union, state ownership of the means of production was combined with central planning, in relation to which goods and services to make and provide, how they were to be produced, the quantities, and the sale prices. Soviet economic planning was an alternative to allowing the market (supply and demand) to determine prices and production. During the Great Depression, many socialists considered Soviet-style planned economies the remedy to capitalism's inherent flaws– monopoly, business cycles, unemployment, unequally distributed wealth, and the economic exploitation of workers.

Consequent to Soviet economic stagnation in the 1970s and 1980s, socialists began to accept parts of their critique. Polish economist Oskar Lange, an early proponent of market socialism, proposed a central planning board establishing prices and controls of investment. The prices of producer goods would be determined through trial and error. The prices of consumer goods would be determined by supply and demand, with the supply coming from state-owned firms that would set their prices equal to the marginal cost, as in perfectly competitive markets. The central planning board would distribute a "social dividend" to ensure reasonable income equality.[15]

State-directed economy

A state-directed economy is a system where either the state or worker cooperatives own the means of production, but economic activity is directed to some degree by a government agency or planning ministry through coordinating mechanisms such as Indicative planning and dirigisme. This differs from a centralised planned economy (or a command economy) in that micro-economic decision making, such as quantity to be produced and output requirements, is left to managers and workers in state enterprises or cooperative enterprises rather than being mandated by a comprehensive economic plan from a centralised planning board. However, the state will plan long-term strategic investment and some aspect of production. It is possible for a state-directed economy to have elements of both a market and planned economy. For example, production and investment decisions may be semi-planned by the state, but distribution of output may be determined by the market mechanism.

State-directed socialism can also refer to technocratic socialism; economic systems that rely on technocratic management mechanisms in addition to public ownership of the means of production. A forerunner of this concept was Henri de Saint-Simon, who understood the state would undergo a transformation in a socialist system and change its role from one of "political administration of men, to the administration of things".[16]

In western Europe, particularly in the period after World War II, many socialist and social democratic parties in government implemented what became known as mixed economies, some of which included a degree of state-directed economic activity. In the biography of the 1945 UK Labour Party Prime Minister Clement Attlee, Francis Beckett states: "the government... wanted what would become known as a mixed economy".[17] Beckett also states that "Everyone called the 1945 government 'socialist'." These governments nationalised major and economically vital industries while permitting a free market to continue in the rest. These were most often monopolistic or infrastructural industries like mail, railways, power and other utilities. In some instances a number of small, competing and often relatively poorly financed companies in the same sector were nationalised to form one government monopoly for the purpose of competent management, of economic rescue (in the UK, British Leyland, Rolls-Royce), or of competing on the world market.

Also in the UK, British Aerospace was a combination of major aircraft companies British Aircraft Corporation, Hawker Siddeley and others. British Shipbuilders was a combination of the major shipbuilding companies including Cammell Laird, Govan Shipbuilders, Swan Hunter, and Yarrow Shipbuilders Typically, this was achieved through compulsory purchase of the industry (i.e. with compensation). In the UK, the nationalisation of the coal mines in 1947 created a coal board charged with running the coal industry commercially so as to be able to meet the interest payable on the bonds which the former mine owners' shares had been converted into.[18][19]

Market socialism

Market socialism refers to various economic systems that involve either public ownership and management or worker cooperative ownership over the means of production, or a combination of both, and the market mechanism for allocating economic output, deciding what to produce and in what quantity. In state-oriented forms of market socialism where state enterprises attempt to maximise profit, the profits can fund government programs and services eliminating or greatly diminishing the need for various forms of taxation that exist in capitalist systems.

The current economic system in China is formally titled Socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics. It combines a large state sector that comprises the 'commanding heights' of the economy, which are guaranteed their public ownership status by law,[20] with a private sector mainly engaged in commodity production and light industry responsible from anywhere between 33%[21] (People's Daily Online 2005) to over 70% of GDP generated in 2005.[22] However by 2005 these market-oriented reforms, including privatization, virtually halted and were partially reversed.[23] Directive centralized planning based on mandatory output requirements and production quotas has been displaced by the free-market mechanism for most of the economy and directive planning in large state industries.[24]

Many political scientists compare this to Gorbachev's perestroika programmes and to the New Economic Policy. A fundamental change between the old planned economy and the socialist market economy is the organisation of state enterprises; in the latter state industries are corporatised. 150 corporate state enterprises report directly to China's central government.[25] By 2008, these state-owned corporations had become dynamic enterprises and generated large increases in revenue for the state,[26][27] resulting in the state-sector leading the economic recovery and contributing to most of the economic growth during the 2009 financial crises.[28]

The Socialist Republic of Vietnam has adopted a similar model after the Doi Moi economic renovation, officially called the socialist-oriented market economy. This model slightly differs from the Chinese model in that the Vietnamese government retains firm control over the state sector and strategic industries, but allows for a considerable increase in private-sector activity for firms engaged in commodity production.[29]

Although there is dispute as to whether or not the Chinese and Vietnamese systems actually constitute state capitalism rather than a socialist commodity economy, the decisive means of production remain under public ownership. Proponents of the socialist market economic system defend it from a Marxist perspective, stating that a planned socialist economy can only become possible after first establishing the necessary comprehensive commodity market economy and letting it fully develop until it exhausts its historical stage and gradually transforms itself into a planned economy.[30] They distinguish themselves from market socialists who believe that economic planning is unattainable, undesirable or ineffective at distributing goods, viewing the market as the solution rather than a temporary phase in development of a socialist planned economy.

De-centralized planned economy

Some socialists propose various decentralised, worker-managed economic systems, as in Mutualism. A de-centralised planned economy is one where ownership of enterprises is accomplished through various forms of worker cooperatives; autogestion and planning of production and distribution are done from the bottom up by local worker councils in a democratic manner. One such system is the cooperative economy, a largely free market economy in which workers manage the firms and democratically determine remuneration levels and labour divisions. Productive resources would be legally owned by the cooperative and rented to the workers, who would enjoy usufruct rights.[31]

Another, more recent, variant is participatory economics, based on Anarcho-Collectivism, wherein the economy is planned by decentralised councils of workers and consumers. Workers would be remunerated solely according to effort and sacrifice, so that those engaged in dangerous, uncomfortable, and strenuous work would receive the highest incomes and could thereby work less.[32]

Social and political theory

Marxist and non-Marxist social theorists agree that socialism developed in reaction to modern industrial capitalism, but disagree on the nature of their relationship. In this context, socialism has been used to refer to a political movement, a political philosophy and a hypothetical form of society these movements aim to achieve. As a result, in a political context socialism has come to refer to the strategy (for achieving a socialist society) or policies promoted by socialist organisations and socialist political parties. Examples include characterising socialist movements by the class struggle or revolutionary activity, or associating socialism with trade-union organisation and various forms of social activism, all of which have no connection to socialism as a socioeconomic system or mode of production.

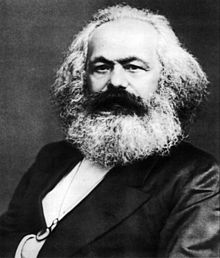

Marxism

In the most influential of all socialist theories, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels believed the consciousness of those who earn a wage or salary (the "working class" in the broadest Marxist sense) would be molded by their "conditions" of "wage-slavery", leading to a tendency to seek their freedom or "emancipation" by throwing off the capitalist ownership of society. For Marx and Engels, conditions determine consciousness and ending the role of the capitalist class leads eventually to a classless society in which the state would wither away.

Marx wrote: "It is not the consciousness of [people] that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness."[33]

The Marxist conception of socialism is that of a specific historical phase that will displace capitalism and precede communism. The major characteristics of socialism (particularly as conceived by Marx and Engels after the Paris Commune of 1871) are that the proletariat will control the means of production through a workers' state erected by the workers in their interests. Economic activity would still be organised through the use of incentive systems and social classes would still exist, but to a lesser and diminishing extent than under capitalism.[34]

For orthodox Marxists, socialism is the lower stage of communism based on the principle of "from each according to his ability, to each according to his contribution" while upper stage communism is based on the principle of "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need"; the upper stage becoming possible only after the socialist stage further develops economic efficiency and the automation of production has led to a superabundance of goods and services.[35][36]

Marx argued that the material productive forces (in industry and commerce) brought into existence by capitalism predicated a cooperative society since production had become a mass social, collective activity of the working class to create commodities but with private ownership (the relations of production or property relations). This conflict between collective effort in large factories and private ownership would bring about a conscious desire in the working class to establish collective ownership commensurate with the collective efforts their daily experience.[37]

"At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or – this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms – with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. Then begins an era of social revolution. The changes in the economic foundation lead sooner or later to the transformation of the whole immense superstructure."[37] A socialist society based on democratric cooperation thus arises. Eventually the state, associated with all previous societies which are divided into classes for the purpose of suppressing the oppressed classes, withers away.

By contrast, Émile Durkheim posits that socialism is rooted in the desire to bring the state closer to the realm of individual activity, in countering the anomie of a capitalist society, considering socialism to "simply represented a system in which moral principles discovered by scientific sociology could be applied". Durkheim could be considered a modern social democrat for advocating social reforms, but rejecting the creation of a socialist society.[38]

Che Guevara sought socialism based on the rural peasantry rather than the urban working class, attempting to inspire the peasants of Bolivia by his own example into a change of consciousness. Guevara said in 1965:

Socialism cannot exist without a change in consciousness resulting in a new fraternal attitude toward humanity, both at an individual level, within the societies where socialism is being built or has been built, and on a world scale, with regard to all peoples suffering from imperialist oppression.[39]

In the middle of the twentieth century, socialist intellectuals retained considerable influence in European philosophy. Eros and Civilisation (1955), by Herbert Marcuse, explicitly attempted to merge Marxism with Freudianism. The social science of Marxist structuralism had a significant influence on the socialist New Left in the 1960s and the 1970s.

Utopian versus scientific

The distinction between "utopian" and "scientific socialism" was first explicitly made by Friedrich Engels in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, which contrasted the "utopian pictures of ideal social conditions" of social reformers with the Marxian concept of scientific socialism. Scientific socialism begins with the examination of social and economic phenomena—the empirical study of real processes in society and history.

For Marxists, the development of capitalism in western Europe provided a material basis for the possibility of bringing about socialism because, according to the Communist Manifesto, "What the bourgeoisie produces above all is its own grave diggers",[40] namely the working class, which must become conscious of the historical objectives set it by society. In Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, Joseph Schumpeter, an Austrian economist, presents an alternative mechanism of how socialism will come about from a Weberian perspective: the increasing bureaucratisation of society that occurs under capitalism will eventually necessitate state-control in order to better coordinate economic activity.

Eduard Bernstein revised this theory to suggest that society is inevitably moving toward socialism, bringing in a mechanical and teleological element to Marxism and initiating the concept of evolutionary socialism. Thorstein Veblen saw socialism as an immediate stage in an ongoing evolutionary process in economics that would result from the natural decay of the system of business enterprise; in contrast to Marx, he did not believe it would be the result of political struggle or revolution by the working class and did not believe it to be the ultimate goal of humanity.[41]

Utopian socialists establish a set of ideals or goals and present socialism as an alternative to capitalism, with subjectively better attributes. Examples of this form of socialism include Robert Owen's New Harmony community.

Social anarchism

Social anarchism, socialist anarchism,[42] anarcho-socialism, anarchist socialism[43] or communitarian anarchism[44] (sometimes used interchangeably with libertarian socialism,[42] left-libertarianism[45] or left-anarchism[46] in its terminology) is an umbrella term used to differentiate two broad categories of anarchism, this one being the collectivist, with the other being individualist anarchism. Social anarchism sees "individual freedom as conceptually connected with social equality and emphasize community and mutual aid."[47]

Social anarchism rejects private property, seeing it as a source of social inequality.[48] Social anarchism is used to specifically describe tendencies within anarchism that have an emphasis on the communitarian and cooperative aspects of anarchist theory and practice. Social anarchism includes (but is not limited to) anarcho-collectivism, anarcho-communism, some forms of libertarian socialism, anarcho-syndicalism and social ecology.

Pierre Joseph Proudhon was involved with the Lyons mutualists and later adopted the name to describe his own teachings.[49] Mutualism is an anarchist school of thought that originates in the writings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who envisioned a society where each person might possess a means of production, either individually or collectively, with trade representing equivalent amounts of labor in the free market.[50] Integral to the scheme was the establishment of a mutual-credit bank that would lend to producers at a minimal interest rate, just high enough to cover administration.[51] Mutualism is based on a labor theory of value that holds that when labor or its product is sold, in exchange, it ought to receive goods or services embodying "the amount of labor necessary to produce an article of exactly similar and equal utility".[52] Receiving anything less would be considered exploitation, theft of labor, or usury.

Collectivist anarchism (also known as anarcho-collectivism) is a revolutionary[53] doctrine that advocates the abolition of the state and private ownership of the means of production. Instead, it envisions the means of production being owned collectively and controlled and managed by the producers themselves. Once collectivization takes place, workers' salaries would be determined in democratic organizations based on the amount of time they contributed to production. These salaries would be used to purchase goods in a communal market.[54] Collectivist anarchism is most commonly associated with Mikhail Bakunin, the anti-authoritarian sections of the First International, and the early Spanish anarchist movement.

Anarchist communism is a theory of anarchism which advocates the abolition of the state, private property, and capitalism in favor of common ownership of the means of production,[55][56] direct democracy and a horizontal network of voluntary associations and workers' councils with production and consumption based on the guiding principle: "from each according to ability, to each according to need".[57][58]

Anarchist communism as a coherent, modern economic-political philosophy was first formulated in the Italian section of the First International by Carlo Cafiero, Emilio Covelli, Errico Malatesta, Andrea Costa and other ex-Mazzinian Republicans.[59] Out of respect for Mikhail Bakunin, they did not make their differences with collectivist anarchism explicit until after Bakunin's death.[60] By the early 1880s, most of the European anarchist movement had adopted an anarchist communist position, advocating the abolition of wage labour and distribution according to need. Ironically, the "collectivist" label then became more commonly associated with Marxist state socialists who advocated the retention of some sort of wage system during the transition to full communism.

Anarcho-syndicalism is a branch of anarchism which focuses on the labour movement.[61] Syndicalisme is a French word, ultimately derived from the Greek, meaning "trade unionism" – hence, the "syndicalism" qualification. Syndicalism is an alternative co-operative economic system. Adherents view it as a potential force for revolutionary social change, replacing capitalism and the state with a new society democratically self-managed by workers.

Reform versus revolution

Reformists, such as classical social democrats, believe that a socialist system can be achieved by reforming capitalism. Socialism, in their view, can be reached through the existing political system by reforming private enterprise. Revolutionaries, such as Marxists and Anarchists, believe such methods will fail because the state ultimately acts in the interests of capitalist business interests. They believe that revolution is the only means to establish a new socio-economic system. They do not necessarily define revolution as a violent insurrection, but instead as a thorough and rapid change.[62]

Socialism from above or below

Socialism from above refers to the viewpoint that reforms or revolutions for socialism will come from, or be led by, higher status members of society who desire a more rational, efficient economic system. Claude Henri de Saint-Simon, and later evolutionary economist Thorstein Veblen, believed that socialism would be the result of innovative engineers, scientists and technicians who want to organise society and the economy in a rational fashion, instead of the working-class. Social democracy is often advocated by intellectuals and the middle-class, as well as the working class segments of the population. Socialism from below refers to the position that socialism can only come from, and be led by, popular solidarity and political action from the lower classes, such as the working class and lower-middle class. Proponents of socialism from below — such as syndicalists and orthodox Marxists — often liken socialism from above to elitism and/or Stalinism.

Technocratic management versus democratic management

The distinction between technocratic/scientific management and democratic management refers to positions on how state institutions and the economy are to be managed. Technocratic organisational management is distinct from bureaucratic and democratic techniques, with the state apparatus being transformed as an administration of economic affairs through technical management as opposed to the administration of people through the creation and enforcement of laws. Some proponents of technocratic socialism are Claude Henri de Saint-Simon, Alexander Bogdanov, Thorstein Veblen, Howard Scott and H. G. Wells.

They include proponents of economic planning (except those, like the Trotskyists, who emphasise the need for democratic workers' control), and socialists inspired by Taylorism. They show a tendency to promote scientific management, whereby technical experts manage institutions and receive their position in society based on a demonstration of their technical expertise or merit, with the aim of creating a rational, effective and stable organisation. Although scientific management is based on technocratic organisation, elements of democracy can be present in the system, such as having democratically decided social goals that are executed by a technocratic state.

Allocation of resources

Resource allocation is the subject of intense debate between market socialists and proponents of planned economies.

Proponents of democratic planning reject both state-led planning and the market, instead arguing for inclusive decision-making on what should be produced, with the distribution of the output being based on direct democracy or council democracy. Leon Trotsky held the view that central planners, regardless of their intellectual capacity, operated without the input and participation of the millions of people who participate in the economy and understand/respond to local conditions and changes in the economy would be unable to effectively coordinate all economic activity.[63]

Equality of opportunity versus equality of outcome

Proponents of equality of opportunity advocate a society in which there are equal opportunities and life chances for all individuals to maximise their potentials and attain positions in society. This would be made possible by equal access to the necessities of life. This position is held by technocratic socialists, Marxists and social democrats. Equality of outcome refers to a state where everyone receives equal amounts of rewards and an equal level of power in decision-making, with the belief that all roles in society are necessary and therefore none should be rewarded more than others. This view is shared by some communal utopian socialists and anarcho-communists.

History

The English word socialism (1839) derives from the French socialisme (1832), the mainstream introduction of which usage is attributed, in France, to Pierre Leroux,[64] and to Marie Roch Louis Reybaud; and in Britain to Robert Owen in 1827, father of the cooperative movement.[65][66] Socialist models and ideas espousing common or public ownership have existed since antiquity. Mazdak, a Persian communal proto-socialist,[67] instituted communal possessions and advocated the public good, and later the classical Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle espoused a form of communism.[68]

The first advocates of socialism favoured social levelling in order to create a meritocratic or technocratic society based upon individual talent. Count Henri de Saint-Simon is regarded as the first individual to coin the term socialism.[8] Saint-Simon was fascinated by the enormous potential of science and technology and advocated a socialist society that would eliminate the disorderly aspects of capitalism and would be based upon equal opportunities.[69] He advocated the creation of a society in which each person was ranked according to his or her capacities and rewarded according to his or her work.[8] The key focus of Simon's socialism was on administrative efficiency and industrialism, and a belief that science was the key to progress.[1]

This was accompanied by a desire to implement a rationally organised economy based on planning and geared towards large-scale scientific and material progress,[8] and thus embodied a desire for a more directed or planned economy. Other early socialist thinkers, such as Thomas Hodgkin and Charles Hall, based their ideas on David Ricardo's economic theories. They reasoned that the equilibrium value of commodities approximated to prices charged by the producer when those commodities were in elastic supply, and that these producer prices corresponded to the embodied labour — the cost of the labour (essentially the wages paid) that was required to produce the commodities. The Ricardian socialists viewed profit, interest and rent as deductions from this exchange-value.[70]

West European social critics, including Robert Owen, Charles Fourier, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Louis Blanc, Charles Hall and Saint-Simon, were the first modern socialists who criticised the excessive poverty and inequality of the Industrial Revolution. They advocated reform, with some such as Robert Owen advocating the transformation of society to small communities without private property. Robert Owen's contribution to modern socialism was his understanding that actions and characteristics of individuals were largely determined by the social environment they were raised in and exposed to.[1]

Linguistically, the contemporary connotation of the words socialism and communism accorded with the adherents' and opponents' cultural attitude towards religion. In Christian Europe, of the two, communism was believed the atheist way of life. In Protestant England, the word communism was too culturally and aurally close to the Roman Catholic communion rite, hence English atheists denoted themselves socialists.[71]

Friedrich Engels argued that in 1848, at the time when the Communist Manifesto was published, "socialism was respectable on the continent, while communism was not." The Owenites in England and the Fourierists in France were considered "respectable" socialists, while working-class movements that "proclaimed the necessity of total social change" denoted themselves communists. This latter branch of socialism produced the communist work of Étienne Cabet in France and Wilhelm Weitling in Germany.[72]

First International and Second International

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), also known as the First International, was founded in London in 1864. Victor Le Lubez, a French radical republican living in London, invited Karl Marx to come to London as a representative of German workers.[73] The IWA held a preliminary conference in 1865, and had its first congress at Geneva in 1866. Marx was appointed a member of the committee, and according to Saul Padover, Marx and Johann Georg Eccarius, a tailor living in London, became "the two mainstays of the International from its inception to its end".[73] The First International became the first major international forum for the promulgation of socialist ideas.

As the ideas of Marx and Engels took on flesh, particularly in central Europe, socialists sought to unite in an international organisation. In 1889, on the centennial of the French Revolution of 1789, the Second International was founded, with 384 delegates from 20 countries representing about 300 labour and socialist organizations.[74] It was termed the "Socialist International" and Engels was elected honorary president at the third congress in 1893.

Revolutions of 1917–1936

If Socialism can only be realized when the intellectual development of all the people permits it, then we shall not see Socialism for at least five hundred years.

— Vladimir Lenin, November 1917 [75]

By 1917, the patriotism of World War I changed into political radicalism in most of Europe, the United States, and Australia. In February 1917, revolution exploded in Russia. Workers, soldiers and peasants established soviets (councils), the monarchy fell, and a provisional government convoked pending the election of a constituent assembly.

In April of that year, Vladimir Lenin arrived in Russia from Switzerland, calling for "All power to the soviets." In October, his party, the Bolsheviks, won support of most soviets at the second All-Russian Congress of Soviets, while he and Leon Trotsky simultaneously led the October Revolution. As a matter of political pragmatism, Lenin reversed Marx’s order of economics over politics, allowing for a political revolution led by a vanguard party of professional revolutionaries rather than a spontaneous establishment of socialist institutions led by a spontaneous uprising of the working class as predicted by Karl Marx.[76] On 25 January 1918, at the Petrograd Soviet, Lenin declared "Long live the world socialist revolution!",[77] He proposed an immediate armistice on all fronts, and transferred the land of the landed proprietors, the crown and the monasteries to the peasant committees without compensation.[78]

On 26 January 1918, the day after assuming executive power, Lenin wrote Draft Regulations on Workers' Control, which granted workers control of businesses with more than five workers and office employees, and access to all books, documents and stocks, and whose decisions were to be "binding upon the owners of the enterprises".[79] Governing through the elected soviets, and in alliance with the peasant-based Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, the Bolshevik government began nationalising banks, industry, and disavowed the national debts of the deposed Romanov royal régime. It sued for peace, withdrawing from World War I, and convoked a Constituent Assembly in which the peasant Socialist-Revolutionary Party (SR) won a majority.[80]

The Constituent Assembly elected Socialist-Revolutionary leader Victor Chernov President of a Russian republic, but rejected the Bolshevik proposal that it endorse the Soviet decrees on land, peace and workers' control, and acknowledge the power of the Soviets of Workers', Soldiers' and Peasants' Deputies. The next day, the Bolsheviks declared that the assembly was elected on outdated party lists,[81] and the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the Soviets dissolved it.[82][83]

The Bolshevik Russian Revolution of January 1918 engendered Communist parties worldwide, and their concomitant revolutions of 1917-23. Few Communists doubted that the Russian success of socialism depended upon successful, working-class socialist revolutions in developed capitalist countries.[84][85] In 1919, Lenin and Trotsky organised the world's Communist parties into a new international association of workers– the Communist International, (Comintern), also called the Third International.

By 1920, the Red Army, under its commander Trotsky, had largely defeated the royalist White Armies. In 1921, War Communism was ended and, under the New Economic Policy (NEP), private ownership was allowed for small and medium peasant enterprises. While industry remained largely state-controlled, Lenin acknowledged that the NEP was a necessary capitalist measure for a country unripe for socialism. Profiteering returned in the form of "NEP men" and rich peasants (Kulaks) gained power in the countryside.[86]

In 1922, the fourth congress of the Communist International took up the policy of the United Front, urging Communists to work with rank and file Social Democrats while remaining critical of their leaders, who they criticised for betraying the working class by supporting the war efforts of their respective capitalist classes. For their part, the social democrats pointed to the dislocation caused by revolution, and later, the growing authoritarianism of the Communist Parties. When the Communist Party of Great Britain applied to affiliate to the Labour Party in 1920 it was turned down.

In 1923, on seeing the Soviet State's growing coercive power, the dying Lenin said Russia had reverted to "a bourgeois tsarist machine... barely varnished with socialism."[87] After Lenin's death in January 1924, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union – then increasingly under the control of Joseph Stalin – rejected the theory that socialism could not be built solely in the Soviet Union, in favour of the concept of Socialism in One Country. Despite the marginalised Left Opposition's demand for the restoration of Soviet democracy, Stalin developed a bureaucratic, authoritarian government, that was condemned by democratic socialists, anarchists and Trotskyists for undermining the initial socialist ideals of the Bolshevik Russian Revolution.[88][89]

The Russian Revolution of October 1917 brought about the definitive ideological division between Communists as denoted with a capital "С" on the one hand and other communist and socialist trends such as anarcho-communists and social democrats, on the other. The Left Opposition in the Soviet Union gave rise to Trotskyism which was to remain isolated and insignificant for another fifty years, except in Sri Lanka where Trotskyism gained the majority and the pro-Moscow wing was expelled from the Communist Party.

After World War II

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2010) |

In 1945, the world’s three great powers met at the Yalta Conference to negotiate an amicable and stable peace. UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill joined USA President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee. With the relative decline of Britain compared to the two superpowers, the USA and the Soviet Union, however, many viewed the world as "bi-polar"– a world with two irreconcilable and antagonistic political and economic systems.

Many termed the Soviet Union "socialist", not least the Soviet Union itself, but also commonly in the USA, China, Eastern Europe, and many parts of the world where Communist Parties had gained a mass base. In addition, scholarly critics of the Soviet Union, such as economist Friedrich Hayek were commonly cited as critics of socialism. This view was not universally shared, particularly in Europe, and especially in Britain, where the Communist Party was very weak.

In 1951, British Health Minister Aneurin Bevan expressed the view that, "It is probably true that Western Europe would have gone socialist after the war if Soviet behaviour had not given it too grim a visage. Soviet Communism and Socialism are not yet sufficiently distinguished in many minds."[90]

In 1951, the Socialist International was re-founded by the European social democratic parties. It declared: "Communism has split the International Labour Movement and has set back the realisation of Socialism in many countries for decades... Communism falsely claims a share in the Socialist tradition. In fact it has distorted that tradition beyond recognition. It has built up a rigid theology which is incompatible with the critical spirit of Marxism."[91]

The last quarter of the twentieth century marked a period of major crisis for Communists in the Soviet Union and the Eastern bloc, where the shortages of housing and consumer goods, combined with the lack of individual rights to assembly and speech, began to disillusion more and more Communist party members and Marxists worldwide. With the rapid dismantling of Communist party rule in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe between 1989 and 1991, the Soviet version of socialism had effectively disappeared as a worldwide political force.

In the postwar years, socialism became increasingly influential throughout the so-called Third World. Countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America frequently adopted socialist economic programmes. In many instances, these nations nationalised industries held by foreign owners. The Soviet Union had become a superpower through its adoption of a planned economy, albeit at enormous human cost. This achievement seemed hugely impressive from the outside, and convinced many nationalists in the former colonies, not necessarily communists or even socialists, of the virtues of state planning and state-guided models of social development. This was later to have important consequences in countries like China, India and Egypt, which tried to import some aspects of the Soviet model.

Social democracy in power

| Part of a series on |

| Social democracy |

|---|

|

In 1945, the British Labour Party, led by Clement Attlee, was elected to office based upon a radical, socialist programme. Social Democratic parties dominated the post-war French, Italian, Czechoslovakian, Belgian, Norwegian, and other, governments. In Sweden, the Social Democratic Party held power from 1936 to 1976 and then again from 1982 to 1991 and from 1994 to 2006. Labour parties governed Australia and New Zealand. In Germany, the Social Democrats lost in 1949. In Eastern Europe, the war-resistance unity, between 'Social Democrats and Communists, continued in the immediate postwar years, until Stalin imposed Communist régimes.

In the UK, the Labour Party was influenced by the British social reformer William Beveridge, who had identified five "Giant Evils" afflicting the working class of the pre-war period: "want" (poverty), disease, "ignorance" (lack of access to education), "squalor" (poor housing), and "idleness" (unemployment).[92] Unemployment benefit, as well as national insurance and hence state pensions, were introduced by the 1945 Labour government. However Aneurin Bevan, who had introduced the Labour Party’s National Health Service in 1948, criticised the Attlee Government for not progressing further, demanding that the "main streams of economic activity are brought under public direction" with economic planning, and criticising the implementation of nationalisation for not empowering the workers with democratic control of operations.

Bevan's In Place of Fear became the most widely read socialist book of the post-war period. It states: "A young miner in a South Wales colliery, my concern was with one practical question: Where does the power lie in this particular state of Great Britain, and how can it be attained by the workers?" [93][94]

Socialists in Europe widely believed that fascism arose from capitalism. The Frankfurt Declaration of the re-founded Socialist International stated:

1. From the nineteenth century onwards, Capitalism has developed immense productive forces. It has done so at the cost of excluding the great majority of citizens from influence over production. It put the rights of ownership before the rights of Man. It created a new class of wage-earners without property or social rights. It sharpened the struggle between the classes.

Although the world contains resources, which could be made to provide a decent life for everyone, Capitalism has been incapable of satisfying the elementary needs of the world’s population. It proved unable to function without devastating crises and mass unemployment. It produced social insecurity and glaring contrasts between rich and poor. It resorted to imperialist expansion and colonial exploitation, thus making conflicts, between nations and races, more bitter. In some countries, powerful capitalist groups helped the barbarism of the past to raise its head again in the form of Fascism and Nazism.| The Frankfurt Declaration 1951[91]

The post-war social democratic governments introduced social reform and wealth redistribution via state welfare and taxation. The UK Labour Government nationalised major public utilities such as mines, gas, coal, electricity, rail, iron, steel, and the Bank of England.[95] France claimed to be the world's most State-controlled, capitalist country.[96]

In the UK, the National Health Service provided free health care to all.[97] Working-class housing was provided in council housing estates, and university education available via a school grant system. Ellen Wilkinson, Minister for Education, introduced free milk in schools, saying, in a 1946 Labour Party conference: "Free milk will be provided in Hoxton and Shoreditch, in Eton and Harrow. What more social equality can you have than that?" Clement Attlee's biographer argued that this policy "contributed enormously to the defeat of childhood illnesses resulting from bad diet. Generations of poor children grew up stronger and healthier, because of this one, small, and inexpensive act of generosity, by the Attlee government".[98]

In 1956, Anthony Crosland said that 25 per cent of British industry was nationalised, and that public employees, including those in nationalised industries, constituted a similar percentage of the country's total employed population.[99] However, the Labour government did not seek to end capitalism, in terms of nationalising of the commanding heights of the economy, as Lenin had put it. In fact, the "government had not the smallest intention of bringing in the ‘common ownership of the means of production, distribution, and exchange’",[100] yet this was the declared aim of the Labour Party, stated in its 'socialist clause', Clause 4 of the Labour Party Constitution. Cabinet minister Herbert Morrison argued that, "Socialism is what the Labour Government does."[100] Crosland claimed capitalism had ended: "To the question, ‘Is this still capitalism?’, I would answer ‘No’."[101]

Social democracy adopts free market policies

Many social democratic parties, particularly after the Cold war, adopted neoliberal-based market policies that include privatization, liberalization, deregulation and financialization; resulting in the abandonment of pursuing the development of moderate socialism in favor of market liberalism. Despite the name, these pro-capitalist policies are radically different from the many non-capitalist free-market socialist theories that have existed throughout history.

In 1959, the German Social Democratic Party adopted the Godesberg Program, rejecting class struggle and Marxism. In 1980, with the rise of conservative neoliberal politicians such as Ronald Reagan in the U.S., Margaret Thatcher in Britain and Brian Mulroney, in Canada, the Western, welfare state was attacked from within. Monetarists and neoliberalism attacked social welfare systems as impediments to private entrepreneurship at public expense.

In the 1980s and 1990s, western European socialists were pressured to reconcile their socialist economic programmes with a free-market-based communal European economy. In the UK, the Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock made a passionate and public attack against the party's Militant Tendency at a Labour Party conference, and repudiated the demands of the defeated striking miners after the 1984-1985 strike against pit closures. In 1989, at Stockholm, the 18th Congress of the Socialist International adopted a new Declaration of Principles, saying:

Democratic socialism is an international movement for freedom, social justice, and solidarity. Its goal is to achieve a peaceful world where these basic values can be enhanced and where each individual can live a meaningful life with the full development of his or her personality and talents, and with the guarantee of human and civil rights in a democratic framework of society.[102]

In the 1990s, released from the Left's pressure, the British Labour Party, under Tony Blair, posited policies based upon the free market economy to deliver public services via private contractors. In 1995, the Labour Party re-defined its stance on socialism by re-wording clause IV of its constitution, effectively rejecting socialism by removing any and all references to public, direct worker or municipal ownership of the means of production. In 1995, the British Labour Party revised its political aims: "The Labour Party is a democratic socialist party. It believes that, by the strength of our common endeavour we achieve more than we achieve alone, so as to create, for each of us, the means to realise our true potential, and, for all of us, a community in which power, wealth, and opportunity are in the hands of the many, not the few."[103]

The objectives of the Party of European Socialists, the European Parliament's socialist bloc, are now "to pursue international aims in respect of the principles on which the European Union is based, namely principles of freedom, equality, solidarity, democracy, respect of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, and respect for the Rule of Law." As a result, today, the rallying cry of the French Revolution – "Egalité, Liberté, Fraternité" – which overthrew absolutism and ushered industrialization into French society, are promoted as essential socialist values.[104]

Early 2000s

Those who championed socialism in its various Marxist and class struggle forms sought out other arenas than the parties of social democracy at the turn of the 21st century. Anti-capitalism and anti-globalisation movements rose to prominence particularly through events such as the opposition to the WTO meeting of 1999 in Seattle. Socialist-inspired groups played an important role in these new movements, which nevertheless embraced much broader layers of the population, and were championed by figures such as Noam Chomsky. The 2003 invasion of Iraq led to a significant anti-war movement in which socialists argued their case.

The Financial crisis of 2007–2010 led to mainstream discussions as to whether "Marx was right".[105][106] Time magazine ran an article 'Rethinking Marx' and put Karl Marx on the cover of its European edition in a special for the 28 January 2009 Davos meeting.[107][108] While the mainstream media tended to conclude that Marx was wrong, this was not the view of socialists and left-leaning commentators.[109][110]

A Globescan BBC poll on the twentieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall found that 23% of respondents believe capitalism is "fatally flawed and a different economic system is needed", with that figure rising to 40% of the population in some developed countries such as France; while a majority of respondents including over 50% of Americans believe capitalism "has problems that can be addressed through regulation and reform".[111]

Africa

African socialism has been and continues to be a major ideology around the continent. Julius Nyerere was inspired by Fabian socialist ideals.[9] He was a firm believer in rural Africans and their traditions and ujamaa, a system of collectivisation that according to Nyerere was present before European imperialism. Essentially he believed Africans were already socialists. Other African socialists include Jomo Kenyatta, Kenneth Kaunda, and Kwame Nkrumah. Fela Kuti was inspired by socialism and called for a democratic African republic. In South Africa the African National Congress (ANC) abandoned its partial socialist allegiances after taking power, and followed a standard neoliberal route. From 2005 through to 2007, the country was wracked by many thousands of protests from poor communities. One of these gave rise to a mass movement of shack dwellers, Abahlali baseMjondolo that, despite major police suppression, continues to advocate for popular people's planning and against the creation of a market economy in land and housing. Today many African countries have been accused of being exploited under neoliberal economics.[10]

Asia

The People's Republic of China, North Korea, Laos and Vietnam are Asian countries remaining from the wave of Marxism-Leninist implemented socialism in the 20th century. States with socialist economies have largely moved away from centralised economic planning in the 21st century, placing a greater emphasis on markets, in the case of the Chinese Socialist market economy and Vietnamese Socialist-oriented market economy, worker cooperatives as in Venezuela, and utilising state-owned corporate management models as opposed to modeling socialist enterprise off traditional management styles employed by government agencies.

In New China, the Chinese Communist Party has led a transition from the command economy of the Mao period to an economic program they term the socialist market economy or "socialism with Chinese characteristics". Under Deng Xiaoping, the leadership of China embarked upon a programme of market-based reform that was more sweeping than had been Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev's perestroika program of the late 1980s. Deng's programme, however, maintained state ownership rights over land, state or cooperative ownership of much of the heavy industrial and manufacturing sectors and state influence in the banking and financial sectors.

Elsewhere in Asia, some elected socialist parties and communist parties remain prominent, particularly in India and Nepal. The Communist Party of Nepal in particular calls for multi-party democracy, social equality, and economic prosperity.[112] In Singapore, a majority of the GDP is still generated from the state sector comprising government-linked companies.[113] In Japan, there has been a resurgent interest in the Japanese Communist Party among workers and youth.[114][115] In Malaysia, the Socialist Party of Malaysia got its first Member of Parliament, Dr. Jeyakumar Devaraj, after the 2008 general election.

Europe

In Europe, the socialist Left Party in Germany grew in popularity[116] due to dissatisfaction with the increasingly neoliberal policies of the SPD, becoming the fourth biggest party in parliament in the general election on 27 September 2009.[117] Communist candidate Dimitris Christofias won a crucial presidential runoff in Cyprus, defeating his conservative rival with a majority of 53%.[118] In Greece, in the general election on 4 October 2009, the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) won the elections with 43.92% of the votes, the Communist KKE got 7.5% and the new Socialist grouping, (Syriza or "Coalition of the Radical Left"), won 4.6% or 361,000 votes.[119]

In Ireland, in the 2009 European election, Joe Higgins of the Socialist Party took one of three seats in the capital Dublin European constituency. In Denmark, the Socialist People's Party (SF or Socialist Party for short) more than doubled its parliamentary representation to 23 seats from 11, making it the fourth largest party.[120]

In the UK, the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers put forward a slate of candidates in the 2009 European Parliament elections under the banner of No to the EU – Yes to Democracy, a broad left-wing alter-globalisation coalition involving socialist groups such as the Socialist Party, aiming to offer an alternative to the "anti-foreigner" and pro-business policies of the UK Independence Party.[121][122][123]

In France, the Revolutionary Communist League (LCR) candidate in the 2007 presidential election, Olivier Besancenot, received 1,498,581 votes, 4.08%, double that of the Communist candidate.[124] The LCR abolished itself in 2009 to initiate a broad anti-capitalist party, the New Anticapitalist Party, whose stated aim is to "build a new socialist, democratic perspective for the twenty-first century".[125]

Latin America

"Every factory must be a school to educate, like Che Guevara said, to produce not only briquettes, steel, and aluminum, but also, above all, the new man and woman, the new society, the socialist society."

— Hugo Chávez, at a May 2009 socialist transformation workshop [126]

Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega, Bolivian President Evo Morales, and Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa refer to their political programmes as socialist. Chávez has adopted the term socialism of the 21st century. After winning re-election in December 2006, Chávez said, "Now more than ever, I am obliged to move Venezuela's path towards socialism."[127]

"Pink tide" is a term being used in contemporary 21st century political analysis in the media and elsewhere to describe the perception that Leftist ideology in general, and Left-wing politics in particular, is increasingly influential in Latin America.[128][129][130]

United States

Socialist parties in the United States reached their zenith in the early twentieth century, but currently active parties and organizations include the Socialist Party USA, the Socialist Workers Party and the Democratic Socialists of America, the latter having approximately 10,000 members.[131]

In the United States since the 1930s, some conservatives have used the terms socialist and creeping socialism as epithets to attack what are actually socially liberal programs that expand the role of the government in the economy.[132]

A December 2008 Rasmussen poll found that when asked whether they supported a state-managed economy or a free-market economy, 70% of American likely voters preferred a free-market economy and 15% preferred a government-managed economy.[133] An April 2009 Rasmussen Reports poll, conducted during the Financial crisis of 2007–2010, suggested that there had been a growth of support for socialism in the United States. The poll results stated that 53% of American adults thought capitalism was better than socialism, and that "Adults under 30 are essentially evenly divided: 37% prefer capitalism, 33% socialism, and 30% are undecided". The question posed by Rasmussen Reports did not define either capitalism or socialism, allowing for the possibility of confusing socialism with regulated capitalism or authoritarian communism.[134]

Criticisms of Socialism

Criticism of socialism refers to a critique of socialist models of economic organization, their efficiency and feasibility; as well as the political and social implications of such a system. Some criticisms are not directed toward socialism as a system, but are directed toward the socialist movement, socialist political parties or existing socialist states. Some critics consider socialism to be a purely theoretical concept that should be criticized on theoretical grounds; others hold that certain historical examples exist and that can be criticized on practical grounds. Because socialism is a broad concept, some criticisms presented in this article will only apply a specific model of socialism that may differ sharply from other types of socialism.

Economic liberals, pro-capitalist Libertarians and some classical liberals view private property of the means of production and the market exchange as natural and/or moral phenomena, which are central to their conceptions of freedom and liberty and thus perceive public ownership of the means of production, cooperatives and economic planning as infringements upon liberty.

Some of the primary criticisms of socialism are distorted or absent price signals[135][136], slow or stagnant technological advance[137], reduced incentives[138][139].[140], reduced prosperity[141][142], feasibility[135][136][137], and its social and political effects.[143][144][145][146][147][148]

See also

- Anarchism

- Anti-Globalisation

- Anti-capitalism

- Class struggle

- Communism

- Dictatorship of the proletariat

- Economic planning

- History of socialism

- Labour movement

- Market Socialism

- Marxism

- Nationalisation

- Nano socialism

- Proletariat

- Proletarian revolution

- Social democracy

- Socialism (Marxism)

- Socialist state

- Socialization of production

- State ownership or Public ownership

- Syndicalism

- To each according to his contribution

- Worker cooperative

- Workers' self-management

Template:Multicol-break National:

- History of socialism in Great Britain, Fabian Society

- Socialism in the United States

- Socialism in Canada

Lists:

References

- ^ a b c Newman, Michael. (2005) Socialism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280431-6

- ^ "Socialism". Oxford English Dictionary. "1. A theory or policy of social organisation which aims at or advocates the ownership and control of the means of production, capital, land, property, etc., by the community as a whole, and their administration or distribution in the interests of all people 2. A state of society in which things are held or used in common."

- ^ "Socialism".Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary

- ^ Socialism and Calculation, on worldsocialism.org. Retrieved February 15, 2010, from worldsocialism.org: http://www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/overview/calculation.pdf: "Although money, and so monetary calculation, will disappear in socialism this does not mean that there will no longer be any need to make choices, evaluations and calculations...Wealth will be produced and distributed in its natural form of useful things, of objects that can serve to satisfy some human need or other. Not being produced for sale on a market, items of wealth will not acquire an exchange-value in addition to their use-value. In socialism their value, in the normal non-economic sense of the word, will not be their selling price nor the time needed to produce them but their usefulness. It is for this that they will be appreciated, evaluated, wanted. . . and produced."

- ^ Critique of the Gotha Programme, Karl Marx.

- ^ Socialism, (2009), in Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 14, 2009, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/551569/socialism, "Main" summary: "Socialists complain that capitalism necessarily leads to unfair and exploitative concentrations of wealth and power in the hands of the relative few who emerge victorious from free-market competition—people who then use their wealth and power to reinforce their dominance in society."

- ^ Marx and Engels Selected Works, Lawrence and Wishart, 1968, p. 40. Capitalist property relations put a "fetter" on the productive forces.

- ^ a b c d "Adam Smith". Fsmitha.com. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ Socialism: Utopian and Scientific at Marxists.org

- ^ Frederick Engels (1910). Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. C.H. Kerr. pp. 92–11.Chapter III: Historical Materialism

- ^ "Market socialism," Dictionary of the Social Sciences. Craig Calhoun, ed. Oxford University Press 2002; and "Market socialism" The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics. Ed. Iain McLean and Alistair McMillan. Oxford University Press, 2003. See also Joseph Stiglitz, "Whither Socialism?" Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995 for a recent analysis of the market socialism model of mid–20th century economists Oskar R. Lange, Abba P. Lerner, and Fred M. Taylor.

- ^ http://www.dlc.org/ndol_ci.cfm?contentid=1570&kaid=125&subid=162 Review of Commanding Heights by the Fred Seigel of the Democratic Leadership Council.

- ^ http://www.amazon.com/Commanding-Heights-Battle-World-Economy/dp/product-description/068483569X Excerpt from Commanding Heights.

- ^ Why Socialism? by Albert Einstein, Monthly Review, May 1949

- ^ John Barkley Rosser and Marina V. Rosser, Comparative Economics in a Transforming World Economy (Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press, 2004).

- ^ Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, on Marxists.org: http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1880/soc-utop/ch01.htm: "In 1816, he declares that politics is the science of production, and foretells the complete absorption of politics by economics. The knowledge that economic conditions are the basis of political institutions appears here only in embryo. Yet what is here already very plainly expressed is the idea of the future conversion of political rule over men into an administration of things and a direction of processes of production."

- ^ Beckett, Francis, Clem Attlee, (2007) Politico's.

- ^ Socialist Party of Great Britain (1985). The Strike Weapon: Lessons of the Miners’ Strike (PDF). London: Socialist Party of Great Britain. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^ Hardcastle, Edgar (1947). "The Nationalisation of the Railways". Socialist Standard. 43 (1). Socialist Party of Great Britain. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^ "China names key industries for absolute state control". Chinadaily.com.cn. 2006-12-19. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ english@peopledaily.com.cn (2005-07-13). "People's Daily Online - China has socialist market economy in place". English.people.com.cn. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ "Microsoft Word - China2bandes.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ Talent, Jim. "10 China Myths for the New Decade | The Heritage Foundation". Heritage.org. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ "The Role of Planning in China's Market Economy" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ "Reassessing China's State-Owned Enterprises". Forbes.com. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ "InfoViewer: China's champions: Why state ownership is no longer proving a dead hand". Us.ft.com. 2003-08-28. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ http://ufirc.ou.edu/publications/Enterprises%20of%20China.pdf

- ^ "China grows faster amid worries". BBC News. 2009-07-16. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- ^ "VN Embassy : Socialist-oriented market economy: concept and development soluti". Vietnamembassy-usa.org. 2003-11-17. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ Market Economy and Socialist Road Duan Zhongqiao <http://docs.google.com/gview?a=v&q=cache:tWl8XGM_vQAJ:www.nodo50.org/cubasigloXXI/congreso06/conf3_zhonquiao.pdf+Socialist+planned+commodity+economy&hl=en&gl=us>

- ^ Vanek, Jaroslav, The Participatory Economy (Ithaca, NY.: Cornell University Press, 1971).

- ^ Michael Albert and Robin Hahnel, The Political Economy of Participatory Economics (Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press, 1991).

- ^ Marx, Karl. A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, (1859)

- ^ "Economic: Karl Marx Socialism and Scientific Communism". Economictheories.org. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ Schaff, Kory (2001). Philosophy and the problems of work: a reader. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 224. ISBN 0-7425-0795-5.

- ^ Walicki, Andrzej (1995). Marxism and the leap to the kingdom of freedom: the rise and fall of the Communist utopia. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press. p. 95. ISBN 0-8047-2384-2.

- ^ a b Karl Marx, Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, 1859

- ^ http://uregina.ca/~gingrich/s16f02.htm

- ^ "At the Afro-Asian Conference in Algeria" speech by Che Guevara to the Second Economic Seminar of Afro-Asian Solidarity in Algiers, Algeria on February 24, 1965

- ^ Marx and Engels, Communist Manifesto

- ^ The life of Thorstein Veblen and perspectives on his thought,

Wood, John (1993). The life of Thorstein Veblen and perspectives on his thought. introd. Thorstein Veblen. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415074878.

The decisive difference between Marx and Veblen lay in their respective attitudes on socialism. For while Marx regarded socialism as the ultimate goal for civilization, Veblen saw socialism as but one stage in the economic evolution of society.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=,|chapterurl=,|laydate=, and|laysummary=(help) - ^ a b Ostergaard, Geoffrey. "Anarchism". The Blackwell Dictionary of Modern Social Thought. Blackwell Publishing. p. 14.

- ^ Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (1893). What is Property?, p. 118

- ^ Morris, Christopher W. 1998. An Essay on the Modern State. Cambridge University Press. p. 74

- ^ Bookchin, Murray (1995). Social Anarchism Or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm. AK Press.

- ^ Thagard, Paul. 2002. Coherence in Thought and Action. MIT Press. p. 153

- ^ Suissa, Judith(2001) "Anarchism, Utopias and Philosophy of Education" Journal of Philosophy of Education 35 (4), 627–646. doi:10.1111/1467-9752.00249

- ^ Ostergaard, Geoffrey. "Anarchism". A Dictionary of Marxist Thought. Blackwell Publishing, 1991. p. 21.

- ^ Woodcock, George. Anarchism: A History Of Libertarian Ideas And Movements. Broadview Press. p. 100

- ^ "Introduction". Mutualist.org. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- ^ Miller, David. 1987. "Mutualism." The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Political Thought. Blackwell Publishing. p. 11

- ^ Tandy, Francis D., 1896, Voluntary Socialism, chapter 6, paragraph 15.

- ^ Patsouras, Louis. 2005. Marx in Context. iUniverse. p. 54

- ^ Bakunin Mikail. Bakunin on Anarchism. Black Rose Books. 1980. p. 369

- ^ From Politics Past to Politics Future: An Integrated Analysis of Current and Emergent Paradigms Alan James Mayne Published 1999 Greenwood Publishing Group 316 pages ISBN 0275961516

- ^ Anarchism for Know-It-Alls By Know-It-Alls For Know-It-Alls, For Know-It-Alls Published by Filiquarian Publishing, LLC., 2008 ISBN 1599862182, 9781599862187 72 pages

- ^ Fabbri, Luigi. "Anarchism and Communism." Northeastern Anarchist #4. 1922. 13 October 2002. http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/anarchist_archives/worldwidemovements/fabbrianarandcom.html

- ^ Makhno, Mett, Arshinov, Valevski, Linski (Dielo Trouda). "The Organizational Platform of the Libertarian Communists". 1926. Constructive Section: available here http://www.nestormakhno.info/english/platform/constructive.htm

- ^ Nunzio Pernicone, "Italian Anarchism 1864 - 1892", pp. 111-113, AK Press 2009.

- ^ James Guillaume, "Michael Bakunin - A Biographical Sketch"

- ^ Georges Sorel in Stuart Isaacs & Chris Sparks, Political Theorists in Context (Routledge, 2004), p. 248. ISBN 0-415-20126-8

- ^ Schaff, Adam, 'Marxist Theory on Revolution and Violence', p. 263. in Journal of the history of ideas, Vol 34, no.2 (Apr-Jun 1973)

- ^ Writings 1932-33, P.96, Leon Trotsky.

- ^ Leroux: socialism is “the doctrine which would not give up any of the principles of Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” of the French Revolution of 1789. "Individualism and socialism" (1834)

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, etymology of socialism

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (1972). A History of Western Philosophy. Touchstone. p. 781

- ^ A Short History of the World. Progress Publishers. Moscow, 1974

- ^ "Economic: Aristotle and Plato Communism". Economictheories.org. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ "2:BIRTH OF THE SOCIALIST IDEA". Anu.edu.au. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ "Utopian Socialists". Cepa.newschool.edu. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ Williams, Raymond (1976). Keywords: a vocabulary of culture and society. Fontana. ISBN 0006334792.

- ^ Engels, Frederick, Preface to the 1888 English Edition of the Communist Manifesto, p. 202. Penguin (2002)

- ^ a b MIA: Encyclopedia of Marxism: Glossary of Organisations, First International (International Workingmen’s Association), accessed 5 July, 2007

- ^ The Second (Socialist) International 1889-1923. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- ^ Ten Days That Shook the World, by John Reed, 2007, ISBN 1-4209-3025-7, pg 165

- ^ Commanding Heights: Lenin's Critique of Global Capitalism"

- ^ Lenin, Vladimir. Meeting of the Petrograd Soviet of workers and soldiers' deputies 25 January 1918, Collected works, Vol 26, p. 239. Lawrence and Wishart, (1964)

- ^ Lenin, Vladimir. To workers Soldiers and Peasants, Collected works, Vol 26, p. 247. Lawrence and Wishart, (1964)

- ^ Lenin, Vladimir. Collected Works, Vol 26, pp. 264–5. Lawrence and Wishart (1964)

- ^ Caplan, Brian. "Lenin and the First Communist Revolutions, IV". George Mason University. Retrieved 2008-02-14. Strictly, the Right Socialist Revolutionaries won - the Left SRs were in alliance with the Bolsheviks.

- ^ Declaration of the RSDLP (Bolsheviks) group at the Constituent Assembly meeting January 5, 1918 Lenin, Collected Works, Vol 26, p. 429. Lawrence and Wishart (1964)

- ^ Draft Decree on the Dissolution of the Constituent Assembly Lenin, Collected Works, Vol 26, p. 434. Lawrence and Wishart (1964)

- ^ Payne, Robert; "The Life and Death of Lenin", Grafton: paperback pp. 425–440

- ^ Bertil, Hessel, Introduction, Theses, Resolutions and Manifestos of the first four congresses of the Third International, pxiii, Ink Links (1980)

- ^ "We have always proclaimed, and repeated, this elementary truth of Marxism, that the victory of socialism requires the joint efforts of workers in a number of advanced countries." Lenin, Sochineniya (Works), 5th ed. Vol. XLIV p. 418, Feb 1922. (Quoted by Mosche Lewin in Lenin's Last Struggle, p. 4. Pluto (1975))

- ^ "''Soviet history: NEPmen''". Soviethistory.org. Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ^ Serge, Victor, From Lenin to Stalin, p. 55

- ^ Serge, Victor, From Lenin to Stalin, p. 52.

- ^ Brinton, Maurice (1975). "The Bolsheviks and Workers' Control 1917–1921 : The State and Counter-revolution". Solidarity. Archived from the original on December 20, 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-22.

- ^ Bevan, Aneurin, In Place of Fear, p 63, p91

- ^ cf Beckett, Francis, Clem Attlee, Politico, 2007, p243. "Idleness" meant unemployment and hence the starvation of the worker and his/her family. It was not then a pejorative term.

- ^ Crosland, Anthony, The Future of Socialism, p52

- ^ Bevan, Aneurin, In Place of Fear p.50, pp.126–128, p.21 MacGibbon and Kee, second edition (1961)

- ^ British Petroleum, privatised in 1987, was officially nationalised in 1951 per government archives [1] with further government intervention during the 1974–79 Labour Government, cf 'The New Commanding Height: Labour Party Policy on North Sea Oil and Gas, 1964–74' in Contemporary British History, Volume 16, Issue 1 Spring 2002 , pages 89–118. Elements of these entities already were in public hands. Later Labour re-nationalised steel (1967, British Steel) after Conservatives denationalised it, and nationalised car production (1976, British Leyland), [2]. In 1977, major aircraft companies and shipbuilding were nationalised

- ^ The nationalised public utilities include CDF (Charbonnages de France), EDF (Électricité de France), GDF (Gaz de France), airlines (Air France), banks (Banque de France), and Renault (Régie Nationale des Usines Renault) [3].

- ^ "One of the consequences of the universality of the British Health Service is the free treatment of foreign visitors." Bevan, Aneurin, In Place of Fear p.104, MacGibbon and Kee, second edition (1961)

- ^ Beckett, Francis, Clem Attlee, p247. Politico's (2007)

- ^ Crosland, Anthony, The Future of Socialism, pp.9, 89. Constable (2006)

- ^ a b Beckett, Francis, Clem Attlee, Politico, 2007, p243