Renminbi

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (September 2009) |

| 人民币 Template:Zh icon | |

|---|---|

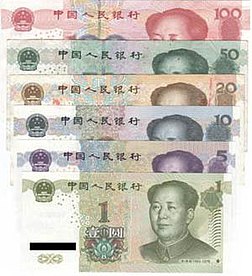

Renminbi banknotes of the 2005 series | |

| ISO 4217 | |

| Code | CNY (numeric: 156) |

| Subunit | 0.01 |

| Unit | |

| Plural | The language(s) of this currency do(es) not have a morphological plural distinction. |

| Symbol | ¥ |

| Nickname | none |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 1 | yuán (元,圓) |

| 1/10 | jiǎo (角) |

| 1/100 | fēn (分) |

| Nickname | |

| yuán (元,圓) | kuài (块) |

| jiǎo (角) | máo (毛) |

| Banknotes | |

| Freq. used | ¥1, ¥5, ¥10, ¥20, ¥50, ¥100 |

| Rarely used | ¥0.1, ¥0.2, ¥0.5, ¥2 |

| Coins | |

| Freq. used | ¥0.1, ¥0.5, ¥1 |

| Rarely used | ¥0.01, ¥0.02, ¥0.05 |

| Demographics | |

| Official user(s) | |

| Unofficial user(s) | |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | People's Bank of China |

| Website | www.pbc.gov.cn |

| Valuation | |

| Inflation | 5.4% March 2011. |

| Pegged with | Partially, to a basket of trade-weighted international currencies |

| Renminbi | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 人民幣 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 人民币 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| yuan | |||||||||

| Chinese | 元 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Renminbi (RMB, sign: ¥; code: CNY; also CN¥, 元 and CN元) is the official currency of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Renminbi is legal tender in mainland China, but not in Hong Kong or Macau. It is issued by the People's Bank of China, the monetary authority of the PRC.[4] Its name (simplified Chinese: 人民币; traditional Chinese: 人民幣; pinyin: rénmínbì) means "people's currency".

The primary unit of renminbi is the yuán (元). One yuan is subdivided into 10 jiǎo (角), which in turn is subdivided into 10 fēn (分). Renminbi banknotes are available in denominations from 1 jiao to 100 yuan (¥0.1–100) and coins have denominations from 1 fen to 1 yuan (¥0.01–1). Thus, some denominations exist in coins and banknotes, but they are usually used in coins if under ¥1. Coins under ¥0.1 are used infrequently.

Through most of its history, the value of the renminbi was pegged to the U.S. dollar. As China pursued its gradual transition from central planning to a free market economy, and increased its participation in foreign trade, the renminbi was devalued to increase the competitiveness of Chinese industry. It has been claimed that the current official exchange rate is lower than the value of the renminbi by purchasing power parity, undervalued by as much as 37.5% (see below).[5]

Since 2005, the renminbi exchange rate has been allowed to float in a narrow margin around a fixed base rate determined with reference to a basket of world currencies. The Chinese government has announced that it will gradually increase the flexibility of the exchange rate. China has initiated various pilot projects to "internationalize" the RMB in the hope that it will become a reserve currency over the long term.[6][7]

Etymology

A variety of currencies circulated in China during the Republic of China (ROC) era, most of which were denominated in the unit "yuán" (pronounced [jʏɛn˧˥]). Each was distinguished by a currency name, such as the fabi ("legal tender"), the "gold yuan", and the "silver yuan". The word yuan (wrtiten as 元 (informally) or 圓 (formally)) in Chinese literally means round, after the shape of the coins.[8] The Korean and Japanese currency units, won and yen respectively, are cognates of the yuan and have the same Chinese character (hanja/kanji) representation, but in different forms (respectively, 원/圓 and 円/圓), also meaning round in Korean and Japanese. However, they do not share the same names for the subdivisions. The principal unit of New Taiwan dollar, used in Taiwan as the currency of the Republic of China, is also referred to in the Chinese language as "yuán" (written as 元 or 圓).

As the Communist Party of China took control of ever larger territories in the latter part of the Chinese Civil War, its People's Bank of China began in 1948 to issue a unified currency for use in Communist-controlled territories. Also denominated in yuan, this currency was identified by different names, including "People's Bank of China banknotes" (simplified Chinese: 中国人民银行钞票; traditional Chinese: 中國人民銀行鈔票; from November 1948), "New Currency" (simplified Chinese: 新币; traditional Chinese: 新幣; from December 1948), "People's Bank of China notes" (simplified Chinese: 中国人民银行券; traditional Chinese: 中國人民銀行券; from January 1949), "People's Notes" (人民券, as an abbreviation of the last name), and finally "People's Currency", or "renminbi", from June 1949.[9]

Production and minting

Renminbi currency production is carried out by a state owned corporation, China Banknote Printing and Minting (CBPMC; 中国印钞造币总公司) headquartered in Beijing.[10] CBPMC uses several printing and engraving and minting facilities around the country to produce banknotes and coins for subsequent distribution. Banknote printing facilities are based in Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu, Xi'an, Shijiazhuang, and Nanchang. Mints are located in Nanjing, Shanghai, and Shenyang. Also, high grade paper for the banknotes is produced at two facilities in Baoding and Kunshan. The Baoding facility is the largest facility in the world dedicated to developing banknote material according to its website.[11] In addition, the People's Bank of China has its own printing technology research division that researches new techniques for creating banknotes and making counterfeiting more difficult.

First series

The first series of renminbi banknotes was introduced by the People's Bank of China in December 1948, about a year before the establishment of the People's Republic of China. It was issued only in paper money form and replaced the various currencies circulating in the areas controlled by the communists. One of the first tasks of the new government was to end the hyperinflation that had plagued China in the final years of the Kuomintang (KMT) era. That achieved, a revaluation occurred in 1955, at the rate of 1 new yuan = 10,000 old yuan.

Banknotes

On December 1, 1948, the newly founded People's Bank of China introduced notes in denominations of 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 and 1000 yuan. Notes for 200, 500, 5000 and 10,000 yuan followed in 1949, with 50,000 yuan notes added in 1950. A total of 62 different designs were issued. The notes were officially withdrawn on various dates between April 1 and May 10, 1955.

These first renminbi notes were printed with the words "People's Bank of China", "Republic of China", and the denomination, written in Chinese characters by Dong Biwu.[12]

The name "renminbi" was first recorded as an official name in June 1949. After work began in 1950 to design the second series of the renminbi, the previous series were retroactively dubbed the "first series of the renminbi".[9]

Second to fifth series

The second series of renminbi banknotes was introduced in 1955. During the era of the command economy, the value of the renminbi was set to unrealistic values in exchange with western currency and severe currency exchange rules were put in place. With the opening of the mainland Chinese economy in 1978, a dual-track currency system was instituted, with renminbi usable only domestically, and with foreigners forced to use foreign exchange certificates. The unrealistic levels at which exchange rates were pegged led to a strong black market in currency transactions.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the PRC worked to make the RMB more convertible. Through the use of swap centres, the exchange rate was brought to realistic levels and the dual track currency system was abolished.

The renminbi is convertible on current accounts but not capital accounts. The ultimate goal has been to make the RMB fully convertible. However, partly in response to the Asian financial crisis in 1998, the PRC has been concerned that the mainland Chinese financial system would not be able to handle the potential rapid cross-border movements of hot money, and as a result, as of 2007, the currency trades within a narrow band specified by the Chinese central government.

The fen and jiao have become increasingly unnecessary as prices have increased. Chinese retailers tend to avoid decimal values (such as ¥9.99), opting instead for integer values of yuan (such as ¥9 or ¥10).[13]

Coins

In 1955, aluminium 1, 2 and 5 fen coins were introduced. In 1980, brass 1, 2, and 5 jiao and cupro-nickel 1 yuan coins were added, although the 1 and 2 jiao were only produced until 1981, with the last 5 jiao and 1 yuan issued in 1985. In 1991, a new coinage was introduced, consisting of an aluminium 1 jiao, brass 5 jiao and nickel-clad-steel 1 yuan. Issuance of the 1 and 2 fen coins ceased in 1991, with that of the 5 fen halting a year later[citation needed]. The small coins were still made for annual mint sets, and from the beginning of 2005 again for general circulation. New designs of the 1 and 5 jiao and 1 yuan were introduced in between 1999 and 2002. The frequency of usage of coins varies between different parts of China.

Banknotes

In 1955, notes (dated 1953), were introduced in denominations of 1, 2 and 5 fen, 1, 2 and 5 jiao, and 1, 2, 3, 5 and 10 yuan. Except for the three fen denominations and the 3 yuan, notes in these denominations continue to circulate, with 50 and 100 yuan notes added in 1980 and 20 yuan notes added in or after 1999.

The denomination of each banknote is printed in Chinese. The numbers themselves are printed in financial Chinese numeral characters, as well as Arabic numerals. The denomination and the words "People's Bank of China" are also printed in Mongolian, Tibetan, Uyghur and Zhuang on the back of each banknote, in addition to the boldface Hanyu Pinyin "Zhongguo Renmin Yinhang" (without tones). The right front of the note has a tactile representation of the denomination in Chinese braille starting from the fourth series.

Second series

The second series of renminbi banknotes (the first having been issued for the previous currency) was introduced on 1 March 1955. Each note has the words "People's Bank of China" as well as the denomination in the Uyghur, Tibetan, Mongolian and Zhuang languages on the back, which has since appeared in each series of renminbi notes. The denominations available in banknotes were ¥0.01, ¥0.02, ¥0.05, ¥0.1, ¥0.2, ¥0.5, ¥1, ¥2, ¥3, ¥5 and ¥10.

Third series

The third series of renminbi banknotes was introduced on April 15, 1962. For the next two decades, the second and third series banknotes were used concurrently. The denominations were of ¥0.1, ¥0.2, ¥0.5, ¥1, ¥2, ¥5 and ¥10. The third series was phased out during the 1990s and then was recalled completely on July 1, 2000.

Fourth series

The fourth series was introduced between 1987 and 1997, although the banknotes were dated 1980, 1990, or 1996. They are still legal tender. Banknotes are available in denominations of ¥0.1, ¥0.2, ¥0.5, ¥1, ¥2, ¥5, ¥10, ¥50 and ¥100.

Fifth series

In 1999, a new series of renminbi banknotes and coins was progressively introduced. The fifth series consists of banknotes for ¥1, ¥5, ¥10, ¥20, ¥50 and ¥100. Significantly, the fifth series uses the portrait of Mao Zedong on all banknotes, in place of the various leaders and workers which had been featured previously.

Commemorative designs

In 1999, a commemorative red ¥50 note was issued in honor of the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the People's Republic of China. This note features Mao Zedong on the front and various animals on the back.

An orange polymer note, and so far, China's only polymer note, commemorating the new millennium was issued in 2000 with a face value of ¥100. This features a dragon on the obverse and the reverse features the China Millennium monument (Center for cultural and scientific fairs).

For the 2008 Beijing Olympics, a green ¥10 note was issued featuring the Bird's Nest on the front with the back showing a classical Olympic discus thrower and various other athletes.

Suggested future design

On March 13, 2006, some delegates to an advisory body at the National People's Congress proposed to include Sun Yat-sen and Deng Xiaoping on the renminbi banknotes. However, the proposal was not adopted.[14]

International use

International Trade

Before 2009, the Chinese renminbi had little to no exposure in the international markets because of strict government controls by the central Chinese government that prohibited almost all forms of yuan holdings or transactions. Transactions between Chinese companies and a foreign entity would have to be denominated in US dollars. With Chinese companies unable to hold US dollars and foreign companies unable to hold Chinese yuan, all transactions would go through the People's Bank of China. Once the sum was paid by the foreign party in dollars, the central bank would pass the settlement in renminbi to the Chinese company. In June 2009 the Chinese officials announced a pilot scheme where business and trade transactions were allowed between limited businesses in Guangdong and Shanghai municipalities and only counterparties in Hong Kong, Macau, and select ASEAN nations. Proving a success,[citation needed] the program was further extended to 20 Chinese provinces and counterparties internationally in July 2010, and in September 2011 it was announced that the remaining 11 Chinese provinces would be included.

In steps intended to establish the renminbi as an international reserve currency, China has agreements with Russia, Vietnam, and Thailand allowing trade with those countries to be settled directly in renminbi instead of requiring conversion to US dollars.[15]

International Reserve Currency

Currency restrictions regarding renminbi denominated bank deposits and financial products were greatly liberalized in July, 2010.[16] In 2010 renminbi denominated bonds were reported to have been purchased by Malaysia's central bank[17] and that McDonald's had issued renmimbi denominated corporate bonds through Standard Chartered Bank of Hong Kong.[18] Such liberalization allows the yuan to look more attractive as it can be held with higher return on investment yields, whereas previously that yield was virtually none. Nevertheless, some national banks such as Bank of Thailand (BOT) have expressed a serious concern about RMB since BOT cannot substitute the depreciated US Dollars in the 200 billion dollar Foreign Exchange Reserves held by BOT with Renminbi Yuan as much as BOT wishes because:

- The Chinese Government has not taken the full responsibilities and commitments on the economic affairs at the global levels.

- Renminbi Yuan still has not become well-liquidated (fully convertible) yet.

- The Chinese government still lacks deep and wide vision about how to perform fund-raising to handle international loans at global levels.[19]

However HSBC expects the Renminbi to become the third major reserve currency in 2011.[20]

Countries that are left-leaning in the political spectrum have also begun to use the Renminbi as an alternative reserve currency to the United States dollar; the Chilean central bank reported in 2011 to have US$91 million worth of Renminbi in reserves, and the president of the central bank of Venezuela, Nelson Merentes, made statements in favour of the Renminbi following the announcement of reserve withdrawals from Europe and the United States.[21]

Use as a currency outside China

The two special administrative regions, Hong Kong and Macau, have their own respective currencies. According to the "one country, two systems" principle and the basic laws of the two territories.[22][23]. Therefore, the Hong Kong dollar and the Macanese pataca remain the legal tenders in the two territories, and renminbi, although sometimes accepted, is not legal tender. Banks in Hong Kong allow people to maintain accounts in RMB.[24] Because of changes in legislation in July 2010, many banks around the world[25] are now slowly offering individuals the chance to hold deposits in Chinese renminbi.

The RMB had a presence in Macau even before the 1999 return to the People's Republic of China from Portugal. Banks in Macau can issue credit cards based on the renminbi but not loans. Renminbi based credit cards cannot be used in Macau's casinos.[26]

The current Republic of China government in Taiwan believes wide usage of the renminbi would create an underground economy and undermine its sovereignty.[27] Tourists are allowed to bring in up to 20,000 renminbi when visiting Taiwan. These renminbi must be converted to the New Taiwan dollar at trial exchange sites in Matsu and Kinmen.[28] The Chen Shui-bian administration insisted that it would not allow full convertibility until the mainland signs a bilateral foreign exchange settlement agreement,[29] though president Ma Ying-jeou has pledged to allow full convertibility as soon as possible.

The renminbi is circulated in some of China's neighbors, such as Pakistan, Mongolia[2][3] and northern part of Thailand.[30][31] Cambodia welcomes the renminbi as an official currency and Laos and Myanmar allow it in border provinces.[2] Though unofficial[clarification needed], Vietnam recognizes the exchange of the renminbi to the đồng.[2]

April 2011: In Hongkong, the Chinese property investment trust, Hui Xian has raised Rmb10.48 billion ($1.6 billion) in the first Initial Public Offering with denomination in Renminbi. Beijing has allowed renminbi-denominated financial markets to develop in Hong Kong because the central Chinese government wants to increase the usage of renminbi in international market and consequently reduce the use of the US dollar.[32]

Since 2007, RMB-nominated bonds are issued outside the Mainland China; these are called "dim sum bonds".

CNH

While the CNY is the RMB which is traded both onshore in China, and offshore (primarily in Hong Kong) are the same currency, they trade at different rates. This is by design: as regulation has explicitly kept onshore and offshore separated, the respective supply and demand conditions lead to separate market clearing exchange rates. Hence the emergence of a new currency code, CNH, to represent the exchange rate of RMB that trades offshore in Hong Kong. However, it does not end here. There is the traditional offshore RMB market, the dollar settled non-deliverable forward (NDF), which itself trades independently of either onshore CNY or offshore CNH, as well as a trade-settlement exchange rate (sometimes called CNT) to which offshore corporates have access, just to add to the complexity.

Value

For most of its early history, the RMB was pegged to the U.S. dollar at 2.46 yuan per USD (note: during the 1970s, it was appreciated until it reached 1.50 yuan per USD in 1980). When China's economy gradually opened in the 1980s, the RMB was devalued in order to improve the competitiveness of Chinese exports. Thus, the official RMB/USD exchange rate declined from 1.50 yuan in 1980 to 8.62 yuan by 1994 (lowest ever on the record). Improving current account balance during the latter half of the 1990s enabled the Chinese government to maintain a peg of 8.27 yuan per USD from 1997 to 2005.

As of August 30, 2011, yuan's exchange rate at 6.38 to the U.S. dollar—its highest official level since a currency revaluation in 2005.[33] China's leaders raised the yuan to tame inflation, a step U.S. officials have pushed for years to help repair the massive trade deficit with China.[33]

Depegged from the U.S. dollar

On July 21, 2005, the peg was finally lifted, which saw an immediate one-off RMB revaluation to 8.11 per USD.[34] The exchange rate against the euro stood at 10.07060 yuan per euro.

However the peg was reinstituted unofficially when the financial crisis hit: "Under intense pressure from Washington, China took small steps to allow its currency to strengthen for three years starting in July 2005. But China 're-pegged' its currency to the dollar as the financial crisis intensified in July 2008." [35]

On June 19, 2010, the People’s Bank of China released a statement simultaneously in Chinese and English indicating that they would "proceed further with reform of the RMB exchange rate regime and increase the RMB exchange rate flexibility." [36] The news was greeted with praise by world leaders including Barack Obama, Nicolas Sarkozy and Stephen Harper.[37] The PBoC maintained there would be no "large swings" in the currency. The RMB rose to its highest level in five years and markets worldwide surged on Monday, June 21 following China's announcement.[38]

China has shifted some of their reserves from dollar accounts to accounts in their competitor nations[citation needed], leading these other nations to invest in dollars to keep their own currencies down[citation needed]. [39]

Managed Float

The RMB is now moved to a managed floating exchange rate based on market supply and demand with reference to a basket of foreign currencies. The daily trading price of the U.S. dollar against the RMB in the inter-bank foreign exchange market would be allowed to float within a narrow band of 0.3% around the central parity published by the People's Bank of China (PBC); in a later announcement published on May 18, 2007, the band was extended to 0.5%.[40] The PRC has stated that the basket is dominated by the United States dollar, Euro, Japanese yen and South Korean won, with a smaller proportion made up of the British pound, Thai baht, Russian ruble, Australian dollar, Canadian dollar and Singapore dollar.[41]

On April 10, 2008, it traded at 6.9920 yuan per US dollar, which was the first time in more than a decade that a dollar had bought less than seven yuan,.[42] and at 11.03630 yuan per euro.

Beginning in January 2010, Chinese and non-Chinese citizens have an annual quota to change a maximum of 50,000 USD. Exchange will only proceed if the applicant appears in person at the relevant bank and presents his passport or his Chinese ID; these deals are being centrally registered. The maximum withdrawal is 10,000 USD per day, the maximum purchase quota of USD is 500 per day. This stringent management of the currency leads to a bottled-up demand for exchange in both directions. It is viewed as a major tool to keep the currency peg, preventing inflows of 'hot money'.

A shift of Chinese reserves into the currencies of their other trading partners has caused these nations to shift more of their reserves into dollars, leading to no great change in the value of the Renminbi against the dollar.[43]

Futures market

Renminbi futures are traded at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. The futures are cash-settled at the exchange rate published by the People's Bank of China.[44]

Purchasing power parity

Scholarly studies suggest that the yuan is undervalued on the basis of purchasing power parity analysis. One recent study suggests 37.5% undervaluation.[5]

- The World Bank estimated that, by purchasing power parity, one International dollar was equivalent to approximately RMB1.9 in 2004.[45]

- The International Monetary Fund estimated that, by purchasing power parity, one United States dollar was equivalent to approximately RMB3.462 in 2006, RMB3.621 in 2007, RMB3.798 in 2008, RMB3.872 in 2009, and RMB3.922 in 2010.[46]

| Current CNY exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD RUB |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD RUB |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD RUB |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD RUB |

See also

- List of Renminbi exchange rates

- Chinese lunar coins

- China Banknote Printing and Minting Corporation (CBPMC)

- Economy of the People's Republic of China

References

- ^ The Chinese Renminbi is widely accepted, alongside the Mongolian tögrög which is the official currency.

- ^ a b c d e "RMB increases its influence in neighbouring areas". People's Daily. 2004-02-17. Retrieved 2007-01-13.

- ^ a b 2009-5-6, 人民幣在蒙古國被普遍使用 - Takungpao

- ^ Article 2, "The People's Bank of China Law of the People's Republic of China". 2003-12-27.

- ^ a b Lipman, Joshua Klein (2011). "Law of Yuan Price: Estimating Equilibrium of the Renminbi" (PDF). Michigan Journal of Business. 4 (2). Retrieved 2011-05-23.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wagner, Wieland (26 January 2011). "China Plans Path to Economic Hegemony". Der Spiegel.

- ^ Frankel, Jeffrey (10 October 2011). "The rise of the renminbi as international currency: Historical precedents". Voxeu.org.

- ^ http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/yuan

- ^ a b 中华人民共和国第一套人民币概述

- ^ China Banknote Printing and Minting

- ^ 保定钞票纸厂

- ^ 中国最早的一张人民币

- ^ Coldness Kwan (2007-03-06). "Do you get one fen change at Origus?". China Daily. Retrieved 2007-03-26.

- ^ Quentin Sommerville (13 March 2006). "China mulls Mao banknote change". BBC News, Shanghai. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "In China, Tentative Steps Toward a Global Currency" article by David Barboza in The New York Times February 11, 2011

- ^ "China revs up renminbi expansion" article by Robert Cookson in The Financial Times July 28, 2010 17:50, accessed October 7, 2010

- ^ "Malaysian bond boost for renminbi" article by Kevin Brown in Singapore, Robert Cookson in Hong Kong and Geoff Dyer in Beijing in The Financial Times September 19, 2010, accessed October 7, 2010

- ^ " McDonald's RMB Corporate Bond Launched in HK" 2010-08-19 Xinhua Web Editor: Xu Leiying, accessed October 7, 2010

- ^ "ธปท.หาทางถ่วงน้ำหนักทุนสำรองหลังดอลลาร์สหรัฐผันผวน". MCOT. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ Yongding, Yu. "The renminbi's journey to the world." Al Jazeera, 29 May 2011.

- ^ Diego Laje, 29 September 2011, China's yuan moving toward global currency?, CNN Business

- ^ "The Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China". 1990-04-04. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

Article 18: National laws shall not be applied in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region except for those listed in Annex III to this Law.

- ^ "The Basic Law of the Macao Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China". 1993-03-31. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

Article 18: National laws shall not be applied in the Macao Special Administrative Region except for those listed in Annex m to this Law.

- ^ "Hong Kong banks to conduct personal renminbi business on trial basis". Hong Kong Monetary Authority. 18 November 2003. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- ^ "Bank of China New York Offers Renminbi Deposits". Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ^ "Macao gets green light for RMB services". China Daily. 2004-08-05. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- ^ "Regular Press Briefing of the Mainland Affairs Council". Mainland Affairs Council. 5 January 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-21. [dead link]

- ^ "CBC head urges immediate liberalization of reminbi conversion". Government Information Office, Taiwan. 2006-12-26. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ^ "Taiwan prepares to allow renminbi exchange". Financial Times. 3 January 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ "Asian Monetary Cooperation: Perspective of RMB Asianalization".

{{cite news}}: Text "www.newasiaforum.org/china_zhang_runlin.pdf" ignored (help) - ^ "Widely used in Mongolia".

- ^ "Hong Kong's first renminbi IPO raises $1.6bn". Financial Times.

- ^ a b Yahoo Finance, Dollar extends slide on views of low US rates. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- ^ "Public Announcement of the People's Bank of China on Reforming the RMB Exchange Rate Regime". 2005-07-21.

- ^ "'Critically important' that China move on currency: Geithner. Treasury chief says he shares Congress' ire over dollar peg". 2010-06-10.

- ^ http://www.pbc.gov.cn/english/detail.asp?col=6400&id=1488

- ^ Phillips, Michael M.; Talley, Ian (2010-06-21). "Global Leaders Welcome China's Yuan Plan". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "World stocks soar after Chinese move on yuan".

- ^ Jonathan Wheatley and Peter Garnham, Brazil in 'International Currency War': Finance Minister Financial Times, 28 September 2010

- ^ "Public Announcement of the People's Bank of China on Enlarging the Floating Band of the RMB Trading Prices against the US Dollar in the Inter-bank Spot Foreign Exchange Market". 2007-05-18.

- ^ "央行行长周小川在央行上海总部揭牌仪式上的讲话". 2005-08-10.

- ^ David Barboza (2008-04-10). "Yuan Hits Milestone Against Dollar". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

- ^ Frangos, Alex Don’t Worry About China, Japan Will Finance U.S. Debt The Wall Street Journal, September 16, 2010

- ^ "Chinese Renminbi Futures" (PDF). CME Group. Retrieved 2010-02-19.

- ^ World Bank: World Development Indicators 2006

- ^ IMF: World Economic Outlook Database, April 2009

Further reading

- Krause, Chester L.; Clifford Mishler (1991). Standard Catalog of World Coins: 1801–1991 (18th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873411501.

- Pick, Albert (1994). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: General Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (7th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-207-9.

- Ansgar Belke, Christian Dreger und Georg Erber: Reduction of Global Trade Imbalances: Does China Have to Revalue Its Currency? In: Weekly Report. 6/2010, Nr. 30, 2010, ISSN 1860-3343, S. 222–229 (PDF-File; DIW Online).

External links

- Stephen Mulvey, 26 June 2010, Why China's currency has two names - BBC News

- Template:Zh icon Template:En icon SinoBanknote

- How to detect counterfeit Chinese money

- Photographs of all Chinese currency and sound of pronunciation in Chinese

- What is the new Chinese currency regime?

- Economist article on Chinese currency valuation

- 'Yuan revaluation the only cure for China's problem', an interview with Michael Pettis, by Venkatesan Vembu, Daily News & Analysis, July 3, 2008.

Chinese external links

News

- China Severs Its Currency's Link to Dollar, Washington Post, July 21, 2005

- China lifts currency basket lid, BBC, August 10, 2005

- 1, 2 and 5 fen banknotes to be withdrawn, from Xinhua online.

- China Announces Further Exchange Rate Reforms, Econ Grapher, June 20, 2010