Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong | |

|---|---|

| 毛泽东 | |

| File:Mao.jpg Official 1967 portrait of Mao Zedong | |

| 1st Chairman of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China | |

| In office June 19, 1945 – September 9, 1976 | |

| Deputy | Liu Shaoqi Lin Biao Zhou Enlai Hua Guofeng |

| Preceded by | Himself (as Central Politburo Chairman) |

| Succeeded by | Hua Guofeng |

| 1st Chairman of the Central Politburo of the Communist Party of China | |

| In office March 20, 1943 – April 24, 1969 | |

| Preceded by | Zhang Wentian (as Central Committee General Secretary) |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as Central Committee Chairman) |

| 1st Chairman of the CPC Central Military Commission | |

| In office August 23, 1945 – 1949 September 8, 1954 – September 9, 1976 | |

| Preceded by | Position created |

| Succeeded by | Hua Guofeng |

| 1st Chairman of the National Committee Of the CPPCC | |

| In office September 21, 1949 – December 25, 1954 Honorary Chairman December 25, 1954 – September 9, 1976 | |

| Preceded by | Position Created |

| Succeeded by | Zhou Enlai |

| 1st Chairman of the People's Republic of China | |

| In office September 27, 1954 – April 27, 1959 | |

| Premier | Zhou Enlai |

| Deputy | Zhu De |

| Preceded by | Position Created |

| Succeeded by | Liu Shaoqi |

| Member of the National People's Congress | |

| In office September 15, 1954 – April 18, 1959 December 21, 1964 – September 9, 1976 | |

| Constituency | Beijing At-large |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 26, 1893 Shaoshan, Hunan |

| Died | September 9, 1976 (aged 82) Beijing |

| Resting place | Chairman Mao Memorial Hall, Beijing, People's Republic of China |

| Nationality | Han Chinese |

| Political party | Communist Party of China |

| Spouse(s) | Luo Yixiu (1907–1910) Yang Kaihui (1920–1930) He Zizhen (1930–1937) Jiang Qing (1939–1976) |

| Signature |  |

Template:Contains Chinese text

| Mao Zedong | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 毛泽东 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 毛澤東 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Máo Zédōng [mɑ̌ʊ tsɤ̌tʊ́ŋ] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman Mao | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 毛主席 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Máo zhǔxí | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Mao Zedong, also transliterated as Mao Tse-tung , and commonly referred to as Chairman Mao (December 26, 1893 – September 9, 1976), was a Chinese communist revolutionary, political theorist and politician. The architect and founding father of the People's Republic of China (PRC) from its establishment in 1949, he governed the country as Chairman of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China until his death in 1976. Politically a Marxist-Leninist, his theoretical contribution to the ideology along with his military strategies and brand of policies are collectively known as Maoism.

Born the son of a wealthy farmer in Shaoshan, Hunan, Mao adopted a Chinese nationalist and anti-imperialist outlook in early life, particularly influenced by the events of the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 and May Fourth Movement of 1919. Coming to adopt Marxism, he became an early member of the Chinese Communist Party, soon rising to a senior position. Mao rose to power by commanding the Long March, forming a united front with Kuomintang (KMT) during the Second Sino-Japanese War to repel a Japanese invasion,[1] and leading the Communist Party of China (CPC) to victory against Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang (KMT) in the Chinese Civil War. After solidifying the reunification of China through his Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries, Mao enacted sweeping land reform, by using violence and terror to overthrow the feudal landlords before seizing their large estates and dividing the land into people's communes.[2][3]

Nationwide political campaigns led by Mao, such as the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, are often considered catastrophic failures; while his rule is believed to have caused the deaths of 40 to 70 million people.[4][5] Severe starvation during the Great Chinese Famine, mass suicide as a result of the Three-anti/five-anti campaigns, and political persecution during both the Anti-Rightist Movement and struggle sessions all resulted from these programs. His campaigns are further blamed for damaging the historical culture and society of China, as relics and religious sites were destroyed in an effort to rapidly modernize the consciousness of the nation.

However, during the years when Mao was China's "Great Helmsman", a range of positive changes also came to China. These included promoting the status of women, improving popular literacy, doubling the school population, providing universal housing, abolishing unemployment and inflation, increasing health care access, and dramatically raising life expectancy.[6][7] In addition, China's population almost doubled during the period of Mao's leadership[8] (from around 550 to over 900 million).[3][7] As a result, Mao is still officially held in high regard by many[who?] in China as a great political strategist, military mastermind, and savior of the nation. Maoists further promote his role as a theorist, statesman, poet, and visionary,[9] while anti-revisionists continue to defend most of his policies.

Although Mao's stated goals of combating bureaucracy, encouraging popular participation, and stressing China's self-reliance are generally seen as laudable—and the rapid industrialization that began during Mao's reign is credited for laying a foundation for China's development in the late 20th century—the harsh methods he used to pursue them, including torture and executions, have been widely rebuked as being ruthless and self-defeating.[3] Mao is still regarded as one of the most important figures in modern world history,[10] and was named one of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century by Time magazine.[11]

Early life

Childhood: 1893–1911

Mao was born on December 26, 1893 in a rural village in Shaoshan, Hunan Province.[12][13][14][15] His father, Mao Shun-sheng (1870–?), had been born into a poverty-stricken peasant family, and had gained two years worth of education before joining the army. Eventually returning to agriculture, he earned a living as both a moneylender and a grain merchant, buying up local grain and then selling it on in the city for a higher price, allowing him to become one of the wealthiest farmers in Shaoshen, with 20 acres of land. Mao Zedong would describe his father as a stern disciplinarian, who would often punish his son and other children – two boys, Tse-min (b.1896) and Tse-tan (b.1905), and an adopted girl – for any perceived wrongdoings, sometimes by beating them.[13][16][17][18] His wife, Wen Ch'i-mei, was illiterate but a devout Buddhist who tried to temper her husband's strict attitude towards both his children and other locals.[19][20][21] Following his mother's example, Mao also became a practising Buddhist from an early age, venerating a bronze statue of the Buddha which was in their home, but abandoned this faith in his mid-teenage years. His father was largely irreligious, although after surviving an encounter with a tiger, began to give offerings to the gods in thanks.[19][22][23]

Aged 8, Mao was sent to the local Shaoshan Primary School by his father, who recognised the financial value of a basic education. Here, Mao was taught the value systems of Confucianism, one of the dominant moral ideologies in China, but he would later admit that he did not enjoy reading the classical Chinese texts which preached Confucian morals, instead favouring popular novels such as Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin.[24][25] Reacting against his Confucian upbringing, aged 10 Mao ran away from home, heading for what he believed was a nearby town, but eventually his father found him and brought him home.[26][27][28]

Aged 13, Mao finished primary education, and his father had him married to Luo Yixiu (1889–1910), a woman eight years his senior, in order to unite their two land-owning families. They never lived together and Mao refused to recognise her as his wife, becoming a fierce critic of arranged marriage.[29][30][31][32] He began work on his father's farm, but continued to read voraciously in his spare time.[28][29] One of the most influential texts that he read was Cheng Kuan-ying's Sheng-shih Wei-yen (Words of Warning to an Affluent Age), a political tract that lamented the deterioration of Chinese power in East Asia, arguing for technological, economic and political reform, modelling China on the representative democracies of the western world. He would later claim that he first developed a "political consciousness" from that booklet.[33][34] Another influential book which he read at the time was a translation of Great Heroes of the World, becoming inspired by the American revolutionary George Washington and French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, whose military prowess and nationalistic fervour greatly impressed him.[35][36]

His political views of the time were also shaped by popular protests that had erupted following a famine in Changsha, the capital of Hunan; Mao supported the protester's demands, but the armed forces soon suppressed the dissenters and executed their leaders.[30][37][38] The famine soon spread throughout Hunan, reaching Shaoshan; here, starving peasants seized some of his father's grain, and while Mao disapproved of their actions as morally wrong, he also claimed a great deal of sympathy for their situation.[39][40] Aged 16, Mao moved on to study at a higher primary school in nearby Tungshan.[28][37] Here, he was taught alongside students of a higher social standing, and was often bullied for his scruffy appearance and peasant background; being much older than the other pupils, he failed to fit in.[41][42][43]

The Xinhai Revolution: 1911–1912

In 1911, Mao convinced his father to allow him to attend middle school in the city of Changsha.[28][41][44] At the time, the city was "a revolutionary hotbed", with widespread animosity towards the governing Emperor Puyi (1906–1967) and the concept of absolute monarchy itself. While some advocated a reformist transition to a constitutional monarchy, most revolutionaries advocated republicanism, hoping to overthrow the Emperor and replace him with a democratically elected President. The primary figurehead behind this republican movement was Dr. Sun Yat-Sen (1867–1925), the leader of a secret society known as the Tongmenghui who had spent time in the United States and converted to Christianity.[45] At Changsha, Mao first read a copy of Sun's newspaper, The People's Strength (Min-lin-pao), and was greatly influenced by it.[46][47] Inspired by Sun's example, Mao penned his first political essay, which he stuck to the school wall; later admitting that it was "somewhat muddled", it involved a plan for overthrowing the monarchy and replacing it with a republic governed by the presidency of Sun, but with concessions made to the moderates by having Kang Youwei as premier and Liang Qichao as minister of foreign affairs.[43][48][49][50] As a symbol of rebellion against the Manchu monarch, he and a friend cut off their queue pigtails – a sign of subservience to the emperor – before forcibly cutting off those of some of their classmates too.[46][49][50]

Later that year, the Chinese armed forces, inspired by the republican ideas of Sun, rose up in insurrection against the Emperor across southern China, sparking the Xinhai Revolution. The city of Changsha initially remained under the control of the monarch, with the governor proclaiming martial law on its streets to quell any popular protests. Soon however, the infantry brigade guarding the city proclaimed their support for the revolution, and the governor was forced to flee, leaving the city in republican hands.[51][52][53] Eager to support the revolutionary cause, Mao joined the rebel army as a private soldier, but was not involved in the fighting. The northern provinces had remained loyal to the Emperor, and hoping to avoid a civil war, Sun Yat-Sen – already proclaimed "provisional president" by his supporters – had come to a compromise with the Emperor's key ally Yuan Shikai (1859–1916); the monarchy would be abolished, and Late Imperial China would be converted into a new Republic of China, but it would be the royalist Yuan and not the revolutionary Sun who would become its first President. The Xinhai Revolution over, Mao resigned from the army in 1912, after six months of being a soldier.[54][55][56][57] It had been during this period that Mao had first learned of the imported western concept of socialism from a newspaper article, and intrigued, he read several pamphlets by Jiang Kanghu (1883–1954), a student who had founded the Chinese Socialist Party in November 1911. Nevertheless, while remaining convinced of the need of a republican government, he was not yet convinced by the need for a socialist economy.[58][59]

Fourth Normal School of Changsha: 1912–1917

Returning his attention to education, Mao enrolled and dropped out of a series of schools in quick succession; a police academy, a soap-production school, a law school and an economics school, the latter being the only course which his father approved of. However, the lectures were given in the English language, which Mao could not understand, and so he soon abandoned this and began attendance at the government-run Changsha Middle School; he soon dropped out of this too, finding its courses too rooted in old Confucian ideas and traditions.[57][60][61][62] Deciding to undertake his studies independently, he spent much time in the newly opened public library at Changsha, reading the core works of classical liberalism such as Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations and Montesquieu's The Spirit of the Laws, as well as the works of western scientists and philosophers like Charles Darwin, J.S. Mill, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Herbert Spencer.[63][64][65] Seeing no use in his son's purely intellectual pursuits, Mao's father cut off his allowance, forcing Mao to move into a hostel for the destitute.[66]

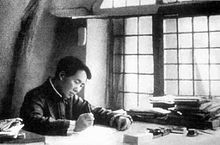

Deciding that he would like to become a professional teacher, Mao enrolled at a teacher training college, the Fourth Normal School of Changsha, which had high standards yet low fees and cheap accommodation. Several months later, it amalgamated with the prestigious First Normal School of Changsha, widely seen as the best school in Hunan province; Mao biographer Stuart Schram would later note that the environment of the school provided "an ideal training ground for his apprenticeship as a political worker."[67][68] He was heavily influenced by several teachers at the school, including the professor of ethics, Yang Changji, who urged Mao and his other students to read a radical newspaper, New Youth (Hsien Ch'ing-nien), which was the creation of his friend Chen Duxiu (1879–1942), Dean of the Faculty of Letters at Peking University. Although a Chinese nationalist, Chen argued that in order to progress, China must look to the west, adopting "Mr. Democracy and Mr. Science" in order to cleanse itself of superstition and autocracy.[69] Mao would publish his first article, "A Study of Physical Culture", in New Youth in April 1917, in which he instructed all Chinese people to increase their physical strength in order to serve the revolutionary cause.[70][71][72][73] He also joined another revolutionary organisation, The Society for the Study of Wang Fuzhi (Chuan-shan Hsüeh-she) which had been founded by a number of Changsha literati who wished to emulate Wang Fuzhi (1619–1692), a philosopher who had become a symbol of Han resistance to Manchu invasion.[74][75]

In his first year at the school, Mao befriended an older student, Siao Yu, and together they went on a walking holiday through the countryside, along the way begging in order to obtain food.[76] Mao also remained active in school politics, in 1915 becoming elected to the position of secretary of the Students Society. He used his position to forge an Association for Student Self-Government, leading protests against various rules then implemented in the school.[72][77][78] In spring 1917, he was also elected to command the students' volunteer army, set up to defend the school from potential attack after two warlords began fighting one another in Hunan.[79][80] With two close friends, Mao began undertaking feats of physical endurance – such as sleeping outdoors and living on a frugal diet – and they began describing themselves as the "Three Heroes" after the rebels that featured in Chinese literature. They attracted other young people with radical political ideas around them, forming a society known as the New People's Study Society who debated Chen Duxiu's ideas.[81][82] Having passed his exams, Mao graduated from the school in the spring of 1918.[83][84]

Revolutionary activity

Peking and Marxism: 1917–1919

Leaving Changsha, Mao moved to the capital city of Peking, where his school mentor Yang Changji had recently migrated to take up a job at Peking University.[85][86][87] Yang was favourable towards Mao, writing in his journal that "it is truly difficult to imagine someone so intelligent and handsome [as him]."[88] Yang secured Mao employment at the university library, where he became assistant to the librarian Li Dazhao (1888–1927), an early Chinese communist.[85][87][89][90] Li authored a series of articles in New Youth on the subject of the October Revolution which had just occurred in Russia, during which the communist Bolshevik Party under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924) had seized power. Lenin was an advocate of the socio-political theory of Marxism, first developed by the German sociologists Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) in the mid-19th century, and Li's articles helped bring an understanding of Marxism to the Chinese revolutionary movement, even though he failed to fully understand it himself.[91][92] Mao would claim that although he did not accept Marxism at first, he had come under the influence of anarchism and was becoming "more and more radical" as the months went on. Beginning to read and discuss the work of Marx with Li and other like-minded radicals at a Marxist Study Group, he eventually "developed rapidly toward Marxism" under Li's tutelage during the winter of 1918–19, looking for ways to combine it with ancient Chinese philosophies that would be applicable to modern China.[93][94][95] Eventually coming to adopt an orthodox Marxist-Leninist position by accepting not only Marx's ideas but also those of Lenin, he came to view Chinese nationalism as a powerful tool in the national liberation struggle against western and Japanese dominance, but unlike orthodox Marxist-Leninists also viewed nationalism as something intrinsically valuable in itself.[96]

Paid a low wage, Mao was forced to live in a cramped room near to the university with seven other Hunanese students, but believed that the beauty of Peking offered "vivid and living compensation."[85][97][98] A number of his friends and future colleagues took advantage of the Mouvement Travail-Études to study in France, but Mao, perhaps because of a lack of ability to learn languages and the requirement to learn French, turned down the opportunity.[90][99][100][101] Remaining at the university, he tried to strike up conversations with academics working there, but most snubbed him because of his rural Hunanese accent and lowly position as librarian's assistant. Nonetheless, by joining the university's Philosophy and Journalism Societies, he was able to attend various lectures and seminars by the likes of Chen Duxiu, Hu Shi, and Qian Xuantong, but various lecturers still treated him with contempt and refused to answer his questions.[85][89][90] Mao's time in Peking came to an end in the spring of 1919, when he traveled to Shanghai with friends departing from the port for France. On the way visiting a number of historic sites such as Qufu, the burial place of Confucius, he traveled much of the journey on foot, at one point losing his shoes.[94][102][103]

Student rebellions: 1919–1920

At the time, China had fallen victim to the expansionist policies of the Empire of Japan, who had conquered large areas of Chinese-controlled territory, namely Taiwan, Korea and South Manchuria. The Japanese claim to these lands had been supported by the western powers of France, the U.K. and the U.S. at the Treaty of Versailles, who also agreed that Japan could take control of all the territories in China that had formerly been under the dominion of the defeated German Empire. The Chinese government, under the control of the warlord Duan Qirui (1865–1936), had accepted Japanese dominance, agreeing to their Twenty-One Demands, despite popular opposition among the Chinese populace.[104][105][106] In May 1919, the May Fourth Movement had erupted in Peking, with Chinese patriots rallying against the Japanese occupation and Duan's collaborative government. Chinese troops were sent in to crush the protests, but the mass unrest spread throughout much of China.[106][107][108][109] In Changsha, Mao took advantage of the unrest to help organize protests against the Governor of Hunan Province, Zhang Jinghui, a supporter of Duan's. Mao was a founding member of the United Student Association and in July 1919 began production of a weekly radical magazine, Hsiang River Review (Hsiang-chiang P'ing-lun). Using vernacular language that would be understandable to the majority of China's populace, he put forward his socialist political views, calling for revolution against the government; in one notable article, he proclaimed the need for a "Great Union of the Popular Masses", but failed to put forward an expressly Marxist analysis of how that revolution should proceed.[108][110][111]

Governor Zhang soon ordered the United Student Association and its associated weekly shut down, but Mao continued publishing his views after assuming editorship of the student magazine New Hunan (Hsin Hunan). When this in turn was also shut down by Zhang's provincial administration, he then began publishing his articles in the popular local newspaper Ta Kung Po. Several of these articles advocated his staunchly feminist views, calling for the liberation of women in Chinese society; alongside his early experiences with forced arranged marriage, this was possibly influenced by the recent death of his mother and his increasing romantic involvement with Yang Kaihui (1901–1930), the daughter of Mao's recently deceased mentor Yang Changji.[31][112][113][114] In November 1919, Mao took a leading role in the re-organization of the banned United Student Association, and in December helped to organize a student strike in Changsha's schools, designed to cripple Zhang's control. The strike did secure some concessions, but Mao and other student leaders felt that they were now under threat from the furious Zhang, and were sent as representatives to China's provincial centers; thus, Mao once again traveled to Peking.[115][116]

In Peking, Mao found that he had achieved a level of fame among the revolutionary movement for his fervent article writing, and he set about soliciting support in overthrowing Zhang's rule in Hunan. It was in the city that he also came across newly translated Marxist literature, further committing him to the revolutionary socialist cause: these included Thomas Kirkup's A History of Socialism, Karl Kautsky's Karl Marx's Ökonomische Lehren and most importantly, Marx and Engels' political pamphlet, The Communist Manifesto.[117][118] From Peking, Mao moved along to Shanghai, working as a laundryman and meeting with Chen Duxiu, who had been recently freed from prison; together, they discussed Marxism, which Chen was also beginning to accept. Mao later noted that Chen's adoption of Marxism "deeply impressed me at what was probably a critical period in my life."[119][120] In Shanghai, Mao also met with one of his old teachers, Yi Peiji, a revolutionary and member of the Kuomintang, or Chinese Nationalist Party, which at the time was gaining increasing support and influence across China.[118] Yi Peiji introduced Mao to General Tan Yankai, a senior Kuomintang member who held the loyalty of the troops stationed along the border between Hunan and Kwantung. Tan was plotting to overthrow Governor Zhang and his pro-Japanese administration, and Mao aided him by organizing the students of Changsha. In June 1920, Tan led his troops into Changsha, while Zhang fled. In the subsequent reorganization of the provincial administration, Mao was appointed as the headmaster of the junior section of the First Normal School.[118][121][122] Now receiving a large income, he was able to marry Yang Kaihui in the winter of 1920.[121][123][124]

Founding the Communist Party of China: 1921–1922

The Communist Party of China was founded by Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao in the French concession of Shanghai in 1921 as a study society and an informal network. Mao soon set up his own branch in Changsha, also establishing a branch of the Socialist Youth Corps. He also opened a bookstore under the control of his new Cultural Book Society, whose purpose was to propagate revolutionary literature throughout Hunan.[123][125][126][127] He also became a labour organiser, helping to set up workers' strikes in the winter of 1920–1921.[123][128] Mao was also involved in the movement advocating autonomy for the province, a viewpoint shared by figures from a variety of different political persuasions. Mao's hope was that the creation of a Hunanese constitution would increase civil liberties in the province and thereby make his revolutionary activity easier; although it proved successful, in later life, he would subsequently deny any involvement in the movement.[129][130] By 1921, small groups of Marxists existed in six Chinese cities: Shanghai, Peking, Changsha, Wuhan, Canton and Tsinan, with a further group having been founded by Chinese students in Paris. It was decided that they should send delegates for a central meeting, which began in Shanghai on July 23, 1921. The first session of the National Congress of the Communist Party of China was attended by 13 delegates, Mao included, and initially met in a girls' school that had been closed for the summer. After the authorities learned of this meeting and sent a police spy to report on their subversive activities, the delegates instead moved their activities to a boat on South Lake near to Chiahsing, where they escaped detection by claiming to be on a holiday excursion. Although delegates from the Soviet Union and Comintern had attended, the first congress ignored Lenin's advice by refusing to accept a temporary alliance between the communists and the "bourgeois democrats" who also advocated national revolution; instead they stuck to the orthodox Marxist belief that only the urban proletariat could lead a socialist revolution.[131][132][133]

Now the party secretary for Hunan, Mao stationed himself in Changsha, from where he went on a recruitment drive to gain support for the Communist Party.[134][135] In August 1921, Mao founded the Self-Study University, through which readers could gain access to Marxist and other revolutionary literature, and which was housed in the premises of the Society for the Study of Wang Fuzhi (Chuan-shan Hsüeh-she).[134][135][136] He also took part in the mass education movement to fight illiteracy, founded in 1921 by members of the Chinese Young Men's Christian Association with U.S. backing. Opening a Changsha branch, Mao replaced the usual textbooks with revolutionary tracts in order to spread Marxist ideas among the illiterate peasantry.[135][137] He also continued with his work in organizing the labour movement to strike in an attempt to damage the administration of Hunanese Governor Chao Heng-t'i, particularly after the latter executed two anarchist activists.[138][139] In July 1922, the Second Congress of the Communist Party took place in Shanghai; while Mao lost the address and was unable to attend, the delegates decided to finally adopt the Leninist advice by agreeing to an alliance with the "bourgeois democrats" of the Kuomintang for the good of the "national revolution" to unite China and free it of foreign imperialist influence. As a result, members of the Communist Party began to join the Kuomintang, hoping to influence its politics in a leftward direction.[140][141] Mao agreed with this decision, vocally arguing for an anti-imperialist alliance which constituted all of China's socio-economic classes, and not merely the urban proletariat. In his writings, he lambasted the governments of Japan, Great Britain and the United States, describing the latter as "the most murderous of hangmen."[142][143]

Collaboration with the Kuomintang: 1922–1927

At the Third Congress of the Communist Party, held in Shanghai in June 1923, the delegates reaffirmed their commitment to working with the Kuomintang, accepting that they should become the driving force leading the labour movement in China. A staunch supporter of this position, at the Congress Mao was elected to the Communist Party Committee, taking up residence in Shanghai.[144] He became involved with the Kuomintang, attending their First Congress, held in Canton in January and February 1924. His enthusiastic support for the nationalist party earned him the suspicion of some of the communists; he was even elected an alternate member of the Kuomintang Central Executive Committee, and in February 1924 put forward four resolutions that argued that power in the party was too centralized among a few cadres in Canton, and that power should instead he decentralized to urban and rural bureaus.[143][145] Biographer Stuart Schram would later comment that during the period between 1925 and 1927, Mao was closer to the Kuomintang than he was to the Communist Party, something he attributed to Mao's belief that the good of China was more important than the cause of socialism.[146]

In late 1924, Mao returned to his home village of Shaoshan for the first time in 15 years to recuperate from an illness. Here, he discovered that the peasantry were becoming increasingly restless as a result of the social and political upheaval of the past decade, with some seizing land from wealthy landowners and founding their own communes. These actions convinced him of the revolutionary potential of the peasants, an idea advocated by the Kuomintang but not the Communist Party.[147][148] As a result, he was subsequently appointed to the leadership of the Kuomintang's Peasant Training Institute, also becoming the Director of the Party's Propaganda Department.[149] Mao and the communists came to comprise most of the left-wing of the Kuomintang, who were opposed by the party's right wing. When party leader Sun Yat-Sen died in May 1925, he was succeeded by a rightist, Chiang Kai-shek (1887–1977), who was opposed to Mao's involvement.[150] On May 30, 1925, police from the International Settlement in Shanghai followed the orders of a British policeman and opened fire on a group of protesters, killing 10 and wounding 50. The Chinese Chamber of Commerce agreed on a strike in solidarity with the protesters, which in turn led to increasingly repressive measures by the authorities.[151][152]

For a while, Mao remained in Shanghai, an important city that the CPC emphasized for the Revolution. However, the Party encountered major difficulties organizing labor union movements and building a relationship with its nationalist ally, the KMT. The Party had become poor, and Mao was disillusioned with the revolution and moved back to Shaoshan. During his stay at home, Mao's interest in the revolution was rekindled after hearing of the 1925 uprisings in Shanghai and Guangzhou. His political ambitions returned, and he then went to Guangdong, the base of the Kuomintang, to take part in the preparations for the second session of the National Congress of Kuomintang. In October 1925, Mao became acting Propaganda Director of the Kuomintang.[citation needed]

In early 1927, Mao returned to Hunan where, in an urgent meeting held by the Communist Party, he made a report based on his investigations of the peasant uprisings in the wake of the Northern Expedition. His "Report on the Peasant Movement in Hunan" is considered the initial and decisive step towards the successful application of Mao's revolutionary theories.[153]

His two 1937 essays, On Practice[154] and On Contradiction,[155] are concerned with the practical strategies of a revolutionary movement and stress the importance of practical, grass-roots knowledge obtained through experience. Both essays reflect the guerrilla roots of Maoism in the need to build up support in the countryside against a Japanese occupying force and emphasise the need to win over hearts and minds through 'education'. The essays, excerpts of which appear in the 'Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong', warn against the behaviour of the blindfolded man trying to catch sparrows, and the 'Imperial envoy' descending from his carriage to 'spout opinions'.

War

"Revolution is not a dinner party, nor an essay, nor a painting, nor a piece of embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another."

In 1927, after a large-scale purge of Communists from the Kuomintang in Shanghai that ended their alliance during the Northern Expedition, Mao conducted the Autumn Harvest Uprising in Changsha as commander-in-chief. Mao led an army, called the "Revolutionary Army of Workers and Peasants", which was defeated by the KMT forces and scattered after fierce battles. Afterwards, the exhausted troops were forced to leave Hunan for Sanwan, Jiangxi, where Mao re-organized the scattered soldiers, rearranging the military division into smaller regiments. Mao also ordered that each company must have a party branch office with a commissar as its leader who would give political instructions based upon superior mandates. This military rearrangement in Sanwan, Jiangxi initiated the CPC's absolute control over its military force and is considered to have had a fundamental and profound impact upon the Chinese revolution. Later, the army moved to the Jinggang Mountains, Jiangxi. In the Jinggang Mountains, Mao persuaded two local insurgent leaders to pledge their allegiance to him. There, Mao joined his army with that of Zhu De, creating the Workers' and Peasants' Red Army of China, Red Army in short. Mao's tactics were based on that of the Spanish Guerrillas during the Napoleonic Wars.[citation needed]

From 1931 to 1934, Mao helped establish the Soviet Republic of China and was elected Chairman of this small republic in the mountainous areas in Jiangxi. Here, Mao was married to He Zizhen. His previous wife, Yang Kaihui, had been arrested and executed in 1930, just three years after their departure. In Jiangxi, Mao's authoritative domination, especially that of the military force, was challenged by the Jiangxi branch of the CPC and military officers. Mao's opponents, among whom the most prominent was Li Wenlin, the founder of the CPC's branch and Red Army in Jiangxi, were against Mao's land policies and proposals to reform the local party branch and army leadership. Mao reacted first by accusing the opponents of opportunism and kulakism and then set off a series of systematic suppressions of them.[158]

It is reported that horrible methods of torture were employed under Mao's direction,[159] and given names such as 'sitting in a sedan chair', 'airplane ride', 'toad-drinking water', and 'monkey pulling reins.' The wives of several suspects that defied him had their breasts cut open and their genitals burned.[159] It estimated that tens of thousands of suspected enemies,[160] perhaps as many as 186,000,[161] were killed during this purge. Critics accuse Mao's authority in Jiangxi of being secured and reassured through the revolutionary terrorism, or red terrorism.[162]

Mao's first appearance in The Times was in August 1929:

"The name of Chu Mao[163] has been infamous on the borders of Fukien and Kwangtung for two years past. Twice he has been driven to refuge in the mountains, being too mobile to catch, but at the first sign of relaxed authority [...], he comes down again to ravage the plains. Chu Mao calls himself a Communist [...]; and wherever Chu Mao goes he begins by calling on the farmers to rise and destroy the capitalists and bourgeois. But he is really the worst kind of brigand."[164]

— The Times: Brigandage in China. In the name of Communism. August 3, 1929

Mao, with the help of Zhu De, built a modest but effective army, undertook experiments in rural reform and government, and provided refuge for Communists fleeing the KMT purges in the cities. Mao's methods are normally referred to as guerrilla warfare; but he himself made a distinction between guerrilla warfare (youji zhan) and mobile warfare (yundong zhan). Mao's doctrines of guerrilla warfare and mobile warfare were based upon the fact of the poor armament and military training of the Red Army which consisted mainly of impoverished peasants, who, however, were fired by revolutionary passions and the aspiration for a communist utopia.

Around 1930, there had been more than ten regions, usually entitled "soviet areas", under control of the CPC.[165] The relative prosperity of "soviet areas" startled and worried Chiang Kai-shek, chairman of the Kuomintang government, who waged five waves of besieging campaigns against the "central soviet area." More than one million Kuomintang soldiers were involved in these five campaigns, four of which were defeated by the Red Army led by Mao. By June 1932 (the height of its power), the Red Army had no less than 45,000 soldiers, with a further 200,000 local militia acting as a subsidiary force.[166]

Under increasing pressure from the KMT Encirclement Campaigns, there was a struggle for power within the Communist leadership. Mao was removed from his important positions and replaced by individuals (including Zhou Enlai) who appeared loyal to the orthodox line advocated by Moscow and represented within the CPC by a group known as the 28 Bolsheviks. Chiang, who had earlier assumed nominal control of China due in part to the Northern Expedition, was determined to eliminate the Communists. By October 1934, he had them surrounded, prompting them to engage in the "Long March", a retreat from Jiangxi in the southeast to Shaanxi in the north west of China. It was during this 9,600-kilometer (6,000 mi), year-long journey that Mao emerged as the top Communist leader, aided by the Zunyi Conference and the defection of Zhou Enlai to Mao's side. At this Conference, Mao entered the Standing Committee of the Politburo of the Communist Party of China.

In 1936 Manchurian warlord and Chiang's former ally Zhang Xueliang decided to conspire with the CPC and kidnapped Chiang Kai-shek in Xi'an to force an end to the conflict between KMT and CPC. To secure the release of Chiang, the KMT was forced to agree to a temporary end to the Chinese Civil War and the forming of a United Front between the CPC and KMT against Japan. The alliance took place with salutary effects for the beleaguered CPC after relentless attacks by Chiang's forces. CPC agreed to form the New Fourth Army and the 8th Route Army which were nominally under the command of the National Revolutionary Army.

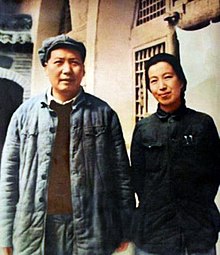

During the Sino-Japanese War, Mao advocated a strategy of avoiding open confrontations with the Japanese army and concentrating on guerrilla warfare from his base in Yan'an, while leaving the KMT to take on the brunt of the fighting and suffer tremendous casualties.[167] Instead Mao directed the CPC forces to concentrate on absorbing, and eliminating if necessary, Chinese militia behind enemy lines. This led to intensified conflicts between KMT and CPC forces, and the fragile alliance broke down after the New Fourth Army incident in January 1941. Mao further consolidated power over the Communist Party in 1942 by launching the Shu Fan movement, or "Rectification" campaign against rival CPC members such as Wang Ming, Wang Shiwei, and Ding Ling. Also while in Yan'an, Mao divorced He Zizhen[citation needed] and married the actress Lan Ping, who would become known as Jiang Qing.

Mao also greatly expanded CPC's sphere of influence in areas outside of Japanese control, mainly through rural mass organizations, administrative, land and tax reform measures favouring poor peasants; while the Nationalists attempted to neutralize the spread of Communist influence by military blockade of areas controlled by CPC and fighting the Japanese at the same time.[169]

In 1944, the Americans sent a special diplomatic envoy, called the Dixie Mission, to the Communist Party of China. According to Edwin Moise, in Modern China: A History 2nd Edition:

- Most of the Americans were favourably impressed. The CPC seemed less corrupt, more unified, and more vigorous in its resistance to Japan than the KMT. United States fliers shot down over North China...confirmed to their superiors that the CPC was both strong and popular over a broad area. In the end, the contacts with the USA developed with the CPC led to very little.

After the end of World War II, the U.S. continued their military assistance to Chiang Kai-shek and his KMT government forces against the People's Liberation Army (PLA) led by Mao Zedong in the civil war for control of China. Likewise, the Soviet Union gave quasi-covert support to Mao by their occupation of north east China, which allowed the PLA to move in en masse and took large supplies of arms left by the Japanese's Kwantung Army.

In 1948, under direct orders from Mao, the People's Liberation Army starved out the Kuomintang forces occupying the city of Changchun. At least 160,000 civilians are believed to have perished during the siege, which lasted from June until October. PLA lieutenant colonel Zhang Zhenglu, who documented the siege in his book White Snow, Red Blood, compared it to Hiroshima: "The casualties were about the same. Hiroshima took nine seconds; Changchun took five months."[170] On January 21, 1949, Kuomintang forces suffered great losses in battles against Mao's forces. In the early morning of December 10, 1949, PLA troops laid siege to Chengdu, the last KMT-held city in mainland China, and Chiang Kai-shek evacuated from the mainland to Taiwan.

Leadership of China

The People's Republic of China was established on October 1, 1949. It was the culmination of over two decades of civil and international wars. From 1943 to 1976, Mao was the Chairman of the Communist Party of China. During this period, Mao was called Chairman Mao (毛主席, Máo Zhǔxí) or the Great Leader Chairman Mao (伟大领袖毛主席, Wěidà Lǐngxiù Máo Zhǔxí). Mao famously announced: "The Chinese people have stood up."[171]

Mao took up residence in Zhongnanhai, a compound next to the Forbidden City in Beijing, and there he ordered the construction of an indoor swimming pool and other buildings. Mao often did his work either in bed or by the side of the pool, preferring not to wear formal clothes unless absolutely necessary, according to Dr. Li Zhisui, his personal physician. (Li's book, The Private Life of Chairman Mao, is regarded as controversial, especially by those sympathetic to Mao.)

In October 1950, Mao made the decision to send the People's Volunteer Army into Korea and fight against the United Nations forces led by the U.S. Historical records showed that Mao directed the PVA campaigns in the Korean War to the minute details.[172]

Along with land reform, during which significant numbers of landlords and well-to-do peasants were beaten to death at mass meetings organized by the Communist Party as land was taken from them and given to poorer peasants,[173] there was also the Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries,[174] which involved public executions targeting mainly former Kuomintang officials, businessmen accused of "disturbing" the market, former employees of Western companies and intellectuals whose loyalty was suspect.[175] The U.S. State department in 1976 estimated that there may have been a million killed in the land reform, and 800,000 killed in the counterrevolutionary campaign.[176]

Mao himself claimed that a total of 700,000 people were executed during the years 1949–53.[177] However, because there was a policy to select "at least one landlord, and usually several, in virtually every village for public execution",[178] the number of deaths range between 2 million[178][179] and 5 million.[180][181] In addition, at least 1.5 million people,[182] perhaps as many as 4 to 6 million,[183] were sent to "reform through labour" camps where many perished.[183] Mao played a personal role in organizing the mass repressions and established a system of execution quotas,[184] which were often exceeded.[174] He defended these killings as necessary for the securing of power.[185]

Starting in 1951, Mao initiated two successive movements in an effort to rid urban areas of corruption by targeting wealthy capitalists and political opponents, known as the three-anti/five-anti campaigns. A climate of raw terror developed as workers denounced their bosses, spouses turned on their spouses, and children informed on their parents; the victims often were humiliated at struggle sessions, a method designed to intimidate and terrify people to the maximum. Mao insisted that minor offenders be criticized and reformed or sent to labor camps, "while the worst among them should be shot." These campaigns took several hundred thousand additional lives, the vast majority via suicide.[186]

In Shanghai, suicide by jumping from tall buildings became so commonplace that residents avoided walking on the pavement near skyscrapers for fear that suicides might land on them.[187] Some biographers have pointed out that driving those perceived as enemies to suicide was a common tactic during the Mao-era. For example, in his biography of Mao, Philip Short notes that in the Yan'an Rectification Movement, Mao gave explicit instructions that "no cadre is to be killed," but in practice allowed security chief Kang Sheng to drive opponents to suicide and that "this pattern was repeated throughout his leadership of the People's Republic."[188]

Following the consolidation of power, Mao launched the First Five-Year Plan (1953–58). The plan aimed to end Chinese dependence upon agriculture in order to become a world power. With the Soviet Union's assistance, new industrial plants were built and agricultural production eventually fell to a point where industry was beginning to produce enough capital that China no longer needed the USSR's support. The success of the First-Five Year Plan was to encourage Mao to instigate the Second Five-Year Plan, the Great Leap Forward, in 1958. Mao also launched a phase of rapid collectivization. The CPC introduced price controls as well as a Chinese character simplification aimed at increasing literacy. Large-scale industrialization projects were also undertaken.

Programs pursued during this time include the Hundred Flowers Campaign, in which Mao indicated his supposed willingness to consider different opinions about how China should be governed. Given the freedom to express themselves, liberal and intellectual Chinese began opposing the Communist Party and questioning its leadership. This was initially tolerated and encouraged. After a few months, Mao's government reversed its policy and persecuted those, totalling perhaps 500,000[citation needed], who criticized, as well as those who were merely alleged to have criticized, the party in what is called the Anti-Rightist Movement. Authors such as Jung Chang have alleged that the Hundred Flowers Campaign was merely a ruse to root out "dangerous" thinking.[189]

Others such as Dr Li Zhisui have suggested that Mao had initially seen the policy as a way of weakening those within his party who opposed him, but was surprised by the extent of criticism and the fact that it began to be directed at his own leadership.[190] It was only then that he used it as a method of identifying and subsequently persecuting those critical of his government. The Hundred Flowers movement led to the condemnation, silencing, and death of many citizens, also linked to Mao's Anti-Rightist Movement, with death tolls possibly in the millions.[citation needed]

Great Leap Forward

In January 1958, Mao Zedong launched the second Five-Year Plan, known as the Great Leap Forward, a plan intended as an alternative model for economic growth to the Soviet model focusing on heavy industry that was advocated by others in the party. Under this economic program, the relatively small agricultural collectives which had been formed to date were rapidly merged into far larger people's communes, and many of the peasants were ordered to work on massive infrastructure projects and on the production of iron and steel. Some private food production was banned; livestock and farm implements were brought under collective ownership.

Under the Great Leap Forward, Mao and other party leaders ordered the implementation of a variety of unproven and unscientific new agricultural techniques by the new communes. Combined with the diversion of labor to steel production and infrastructure projects, these projects combined with cyclical natural disasters led to an approximately 15% drop in grain production in 1959 followed by a further 10% reduction in 1960 and no recovery in 1961.[191]

In an effort to win favor with their superiors and avoid being purged, each layer in the party hierarchy exaggerated the amount of grain produced under them. Based on the fabricated success, party cadres were ordered to requisition a disproportionately high amount of the true harvest for state use, primarily in the cities and urban areas but also for export. The net result, which was compounded in some areas by drought and in others by floods, left rural peasants with little food for themselves and many millions starved to death in the largest famine known as the Great Chinese Famine. This famine was a direct cause of the death of some 30 million Chinese peasants between 1959 and 1962 and about the same number of births were lost or postponed.[192] Further, many children who became emaciated and malnourished during years of hardship and struggle for survival died shortly after the Great Leap Forward came to an end in 1962.[191]

The extent of Mao's knowledge of the severity of the situation has been disputed. According to some, most notably Dr. Li Zhisui, Mao was not aware that the situation amounted to more than a slight shortage of food and general supplies until late 1959.[citation needed]

Hong Kong-based historian Frank Dikötter, who conducted extensive archival research on the Great Leap Forward in local and regional Chinese government archives,[193] challenged the notion that Mao did not know about the famine until it was too late:

"The idea that the state mistakenly took too much grain from the countryside because it assumed that the harvest was much larger than it was is largely a myth – at most partially true for the autumn of 1958 only. In most cases the party knew very well that it was starving its own people to death. At a secret meeting in the Jinjiang Hotel in Shanghai dated March 25, 1959, Mao specifically ordered the party to procure up to one third of all the grain, much more than had ever been the case. At the meeting he announced that 'When there is not enough to eat, people starve to death. It is better to let half of the people die so that the other half can eat their fill.'"

In Hungry Ghosts, Jasper Becker notes that Mao was dismissive of reports he received of food shortages in the countryside and refused to change course, believing that peasants were lying and that rightists and kulaks were hoarding grain. He refused to open state granaries,[195] and instead launched a series of "anti-grain concealment" drives that resulted in numerous purges and suicides.[196] Other violent campaigns followed in which party leaders went from village to village in search of hidden food reserves, and not only grain, as Mao issued quotas for pigs, chickens, ducks and eggs. Many peasants accused of hiding food were tortured and beaten to death.[197]

In contrast, journals such as the Monthly Review have disputed the reliability of the figures commonly cited, the qualitative evidence of a "massive death toll", and Mao's complicity in those deaths which occurred.[198]

Whatever the case, the Great Leap Forward caused Mao to lose esteem among many of the top party cadres and was eventually forced to abandon the policy in 1962, while losing some political power to moderate leaders, notably Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping in the process. However, Mao, supported by national propaganda, claimed that he was only partly to blame. As a result, he was able to remain Chairman of the Communist Party, with the Presidency transferred to Liu Shaoqi.

The Great Leap Forward was a disaster for China. Although the steel quotas were officially reached, almost all of the supposed steel made in the countryside was iron, as it had been made from assorted scrap metal in home-made furnaces with no reliable source of fuel such as coal. This meant that proper smelting conditions could not be achieved. According to Zhang Rongmei, a geometry teacher in rural Shanghai during the Great Leap Forward:

"We took all the furniture, pots, and pans we had in our house, and all our neighbors did likewise. We put everything in a big fire and melted down all the metal."

The worst of the famine was steered towards enemies of the state.[199] As Jasper Becker explains:

"The most vulnerable section of China's population, around five per cent, were those whom Mao called 'enemies of the people'. Anyone who had in previous campaigns of repression been labeled a 'black element' was given the lowest priority in the allocation of food. Landlords, rich peasants, former members of the nationalist regime, religious leaders, rightists, counter-revolutionaries and the families of such individuals died in the greatest numbers."[200]

Consequences

At the Lushan Conference in July/August 1959, several leaders expressed concern that the Great Leap Forward had not proved as successful as planned. The most direct of these was Minister of Defence and Korean War General Peng Dehuai. Mao, fearing loss of his position, orchestrated a purge of Peng and his supporters, stifling criticism of the Great Leap policies. Senior officials who reported the truth of the famine to Mao were branded as "right opportunists."[201] A campaign against right opportunism was launched and resulted in party members and ordinary peasants being sent to camps where many would subsequently die in the famine. Years later the CPC would conclude that 6 million people were wrongly punished in the campaign.[202]

The number of deaths by starvation during the Great Leap Forward is deeply controversial. Until the mid 1980s, when official census figures were finally published by the Chinese Government, little was known about the scale of the disaster in the Chinese countryside, as the handful of Western observers allowed access during this time had been restricted to model villages where they were deceived into believing that the Great Leap Forward had been a great success. There was also an assumption that the flow of individual reports of starvation that had been reaching the West, primarily through Hong Kong and Taiwan, must be localized or exaggerated as China was continuing to claim record harvests and was a net exporter of grain through the period. Because Mao wanted to pay back early to the Soviets debts totaling 1.973 billion yuan from 1960 to 1962,[203] exports increased by 50%, and fellow Communist regimes in North Korea, North Vietnam and Albania were provided grain free of charge.[195]

Censuses were carried out in China in 1953, 1964 and 1982. The first attempt to analyse this data in order to estimate the number of famine deaths was carried out by American demographer Dr. Judith Banister and published in 1984. Given the lengthy gaps between the censuses and doubts over the reliability of the data, an accurate figure is difficult to ascertain. Nevertheless, Banister concluded that the official data implied that around 15 million excess deaths incurred in China during 1958–61, and that based on her modelling of Chinese demographics during the period and taking account of assumed under-reporting during the famine years, the figure was around 30 million. The official statistic is 20 million deaths, as given by Hu Yaobang.[204] Yang Jisheng, a former Xinhua News Agency reporter who had privileged access and connections available to no other scholars, estimates a death toll of 36 million.[203] Frank Dikötter estimates that there were at least 45 million premature deaths attributable to the Great Leap Forward from 1958 to 1962.[205][206] Various other sources have put the figure at between 20 and 46 million.[207]

On the international front, the period was dominated by the further isolation of China. The Sino-Soviet split resulted in Nikita Khrushchev's withdrawal of all Soviet technical experts and aid from the country. The split was triggered by arguments over the control and direction of world communism and other disputes pertaining to foreign policy.[citation needed] Most of the problems regarding communist unity resulted from the death of Joseph Stalin in March 1953 and his replacement by Khrushchev. Only Albania under the leadership of Enver Hoxha openly sided with China against the Soviets, which began an alliance between the two countries which would last until the Sino-Albanian split after Mao's death in 1976.

Stalin had established himself as the successor of "correct" Marxist thought well before Mao controlled the Communist Party of China, and therefore Mao never challenged the suitability of any Stalinist doctrine (at least while Stalin was alive). Upon the death of Stalin, Mao believed (perhaps because of seniority) that the leadership of the "correct" Marxist doctrine would fall to him. The resulting tension between Khrushchev (at the head of a politically and militarily superior government), and Mao (believing he had a superior understanding of Marxist ideology) eroded the previous patron-client relationship between the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the CPC.[citation needed] In China, the formerly favorable Soviets were now denounced as "revisionists" and listed alongside "American imperialism" as movements to oppose.[citation needed]

Partly surrounded by hostile American military bases (in South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan), China was now confronted with a new Soviet threat from the north and west. Both the internal crisis and the external threat called for extraordinary statesmanship from Mao, but as China entered the new decade the statesmen of the People's Republic were in hostile confrontation with each other.

At a large Communist Party conference in Beijing in January 1962, called the "Conference of the Seven Thousand," State Chairman Liu Shaoqi denounced the Great Leap Forward as responsible for widespread famine.[208] The overwhelming majority of delegates expressed agreement, but Defense Minister Lin Biao staunchly defended Mao.[208] A brief period of liberalization followed while Mao and Lin plotted a comeback.[208] Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping rescued the economy by disbanding the people's communes, introducing elements of private control of peasant smallholdings and importing grain from Canada and Australia to mitigate the worst effects of famine.[citation needed]

Cultural Revolution

Mao was concerned with the nature of post-1959 China. He saw that the revolution had replaced an old elite with a new one. He was concerned that those in power were becoming estranged from the people they were supposed to serve.

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (April 2012) |

Mao believed that a revolution of culture would unseat and unsettle the "ruling class" and keep China in a state of "perpetual revolution" that served the interests of the majority, not a tiny elite.[209] Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, then the State Chairman and General Secretary, respectively, had favored the idea that Mao should be removed from actual power but maintain his ceremonial and symbolic role, with the party upholding all of his positive contributions to the revolution. They attempted to marginalize Mao by taking control of economic policy and asserting themselves politically as well. Many claim that Mao responded to Liu and Deng's movements by launching the Cultural Revolution in 1966. Some scholars, such as Mobo Gao, claim the case for this is perhaps overstated.[210] Others, such as Frank Dikötter, hold that Mao launched the Cultural Revolution to wreak revenge on those who had dared to challenge him over the Great Leap Forward.[211]

Believing that certain liberal bourgeois elements of society continued to threaten the socialist framework, groups of young people known as the Red Guards struggled against authorities at all levels of society and even set up their own tribunals. Chaos reigned in many parts of the country, and millions were persecuted, including a famous philosopher, Chen Yuen. During the Cultural Revolution, the schools in China were closed and the young intellectuals living in cities were ordered to the countryside to be "re-educated" by the peasants, where they performed hard manual labor and other work.

The Revolution led to the destruction of much of China's traditional cultural heritage and the imprisonment of a huge number of Chinese citizens, as well as creating general economic and social chaos in the country. Millions of lives were ruined during this period, as the Cultural Revolution pierced into every part of Chinese life, depicted by such Chinese films as To Live, The Blue Kite and Farewell My Concubine. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, perished in the violence of the Cultural Revolution.[207]

When Mao was informed of such losses, particularly that people had been driven to suicide, he is alleged to have commented: "People who try to commit suicide — don't attempt to save them! . . . China is such a populous nation, it is not as if we cannot do without a few people."[212] The authorities allowed the Red Guards to abuse and kill opponents of the regime. Said Xie Fuzhi, national police chief: "Don't say it is wrong of them to beat up bad persons: if in anger they beat someone to death, then so be it."[213] As a result, in August and September 1966, there were 1,772 people murdered in Beijing alone.[214]

It was during this period that Mao chose Lin Biao, who seemed to echo all of Mao's ideas, to become his successor. Lin was later officially named as Mao's successor. By 1971, however, a divide between the two men became apparent. Official history in China states that Lin was planning a military coup or an assassination attempt on Mao. Lin Biao died in a plane crash over the air space of Mongolia, presumably on his way to flee China, probably anticipating his arrest. The CPC declared that Lin was planning to depose Mao, and posthumously expelled Lin from the party. At this time, Mao lost trust in many of the top CPC figures. The highest-ranking Soviet Bloc intelligence defector, Lt. Gen. Ion Mihai Pacepa described his conversation with Nicolae Ceauşescu who told him about a plot to kill Mao Zedong with the help of Lin Biao organized by the KGB.[215]

In 1969, Mao declared the Cultural Revolution to be over, although the official history of the People's Republic of China marks the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976 with Mao's death. In the last years of his life, Mao was faced with declining health due to either Parkinson's disease or, according to Li Zhisui, motor neuron disease, as well as lung ailments due to smoking and heart trouble. Some also attributed Mao's decline in health to the betrayal of Lin Biao. Mao remained passive as various factions within the Communist Party mobilized for the power struggle anticipated after his death.

This period is often looked at in official circles in China and in the West as a great stagnation or even of reversal for China. While many—an estimated 100 million—did suffer,[216] some scholars, such as Lee Feigon and Mobo Gao, claim there were many great advances, and in some sectors the Chinese economy continued to outperform the west.[217] They conclude that the Cultural Revolution period laid the foundation for the spectacular growth that continues in China. During the Cultural Revolution, China exploded its first H-Bomb (1967), launched the Dong Fang Hong satellite (January 30, 1970), commissioned its first nuclear submarines and made various advances in science and technology. Healthcare was free, and living standards in the countryside continued to improve.[217]

This article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (August 2012) |

Death

This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (April 2012) |

Mao had been in poorer health for several years and had declined visibly for at least six months prior to his death and there are unconfirmed reports that he possibly had ALS or Lou Gehrig's disease.[218] Mao's last public appearance was on May 27, 1976, where he met the visiting Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto during the latter's one-day visit to Beijing.

At around 5:00 pm on September 2, 1976, Mao suffered a heart attack, far more severe than his previous two and affecting a much larger area of his heart. X-rays indicated that his current lung infection had worsened, and his urine output dropped to less than 300 cc a day.[citation needed] Mao was awake and alert throughout the crisis and asked his team of doctors, several times, whether he was in danger. His condition continued to fluctuate and his life hung in the balance. Three days later, on September 5, Mao's condition was still critical, and Hua Guofeng called Jiang Qing back from her trip.[which?] She spent only a few minutes visiting him in Building 202 (where Mao was staying) before returning to her own residence in the Spring Lotus Chamber.[citation needed] On the afternoon of September 7, Mao's condition took a turn for the worse. Jiang Qing went to Building 202 where she learned the news. Mao had just fallen asleep and needed the rest, but she insisted on rubbing his back and moving his limbs, and she sprinkled powder on his body. The medical team protested that the dust from the powder was not good for his lungs, but she instructed the nurses on duty to follow her example later. The next morning, September 8, she went again. She demanded the medical staff to change Mao's sleeping position, claiming that he had been lying too long on his left side.[citation needed] The doctor on duty objected, knowing that he could breathe only on his left side, but she had him moved nonetheless.[citation needed] Mao's breathing stopped and his face turned blue.[citation needed] Jiang Qing left the room while the medical staff put him on a respirator and performed emergency cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Mao barely revived and Hua Guofeng urged Jiang Qing not to interfere further with the doctors' work, as her actions were detrimental to Mao's health and helped cause his death faster.[citation needed] Mao's organs failed quickly and he fell into a coma shortly before noon where he was put on life support machines. He was taken off life support over 12 hours later quarter to midnight and was pronounced dead at 12:10 am on September 9, 1976. September 9 was chosen to let Mao die on because it was an easy day to remember, being the ninth day of the ninth month of the calendar.[citation needed]

His body lay in state at the Great Hall of the People. A memorial service was held in Tiananmen Square on September 18, 1976. There was a three-minute silence observed during this service. His body was later placed into the Mausoleum of Mao Zedong, even though he had wished to be cremated and had been one of the first high-ranking officials to sign the "Proposal that all Central Leaders be Cremated after Death" in November 1956.[219]

As anticipated after Mao's death, there was a power struggle for control of China. On one side was the left wing led by the Gang of Four, who wanted to continue the policy of revolutionary mass mobilization. On the other side was the right wing opposing these policies. Among the latter group, the right wing restorationists, led by Chairman Hua Guofeng, advocated a return to central planning along the Soviet model, whereas the right wing reformers, led by Deng Xiaoping, wanted to overhaul the Chinese economy based on market-oriented policies and to de-emphasize the role of Maoist ideology in determining economic and political policy. Eventually, the reformers won control of the government. Deng Xiaoping, with clear seniority over Hua Guofeng, defeated Hua in a bloodless power struggle a few years later.

Legacy

"[Mao] turned China from a feudal backwater into one of the most powerful countries in the World ... The Chinese system he overthrew was backward and corrupt; few would argue the fact that he dragged China into the 20th century. But at a cost in human lives that is staggering."

Mao remains a controversial figure and there is little agreement over his legacy both in China and abroad. He is generally credited and praised with having unified China and ending the previous decades of civil war. He is also credited with having improved the status of women in China and improving literacy and education. His policies caused the deaths of tens of millions of people during his 27-year reign, more than any other Twentieth Century leader, however supporters point out that in spite of this, life expectancy improved during his reign. Supporters claim that he rapidly industrialized China, but detractors claim that his policies, particularly the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, were impediments to industrialization and modernization. Supporters claim that his policies laid the groundwork for China's later rise to become an economic superpower, while detractors claim that his policies delayed economic development and that China's economy only underwent its rapid growth after Mao's policies had been widely abandoned. Mao's revolutionary tactics continue to be used by insurgents, and his political ideology continues to be embraced by many communist organizations around the world.

In mainland China, Mao is still revered by many supporters of the Communist Party and respected by a majority of the general population as the "Founding Father of modern China", credited for giving "the Chinese people dignity and self-respect."[2] Mobo Gao in his 2008 book The Battle for China's Past: Mao and the Cultural Revolution, credits Mao for raising the average life expectancy from 35 in 1949 to 63 by 1975, bringing "unity and stability to a country that had been plagued by civil wars and foreign invasions", and laying the foundation for China to "become the equal of the great global powers".[6] Gao also lauds Mao for carrying out massive land reform, promoting the status of women, improving popular literacy, and positively "transform(ing) Chinese society beyond recognition."[6]

However, Mao has many Chinese critics, both those who live inside and outside China. Opposition to Mao is subject to restriction in mainland China, but is especially strong elsewhere, where he is often reviled as a brutish ideologue. In the West, his name is generally associated with tyranny and his economic theories widely discredited – though to some political activists he remains a symbol against capitalism, imperialism and western influence. Even in China, key pillars of his economic theory have been largely dismantled by market reformers like Deng Xiaoping and Zhao Ziyang, who succeeded him as leaders of the Communist Party.

Though the Chinese Communist Party, which Mao led to power, has rejected in practice the economic fundamentals of much of Mao's ideology, it retains for itself many of the powers established under Mao's reign: it controls the Chinese army, police, courts and media and does not permit multi-party elections at the national or local level, except in Hong Kong. Thus it is difficult to gauge the true extent of support for the Chinese Communist Party and Mao's legacy within mainland China. For their part, the Chinese government continues to officially regard Mao as a national hero. In 2008, China opened the Mao Zedong Square to visitors in his hometown of central Hunan Province to mark the 115th anniversary of his birth.[220][221]

There continue to be disagreements on Mao's legacy. Former Party official Su Shachi, has opined that "he was a great historical criminal, but he was also a great force for good."[2] In a similar vein, journalist Liu Bin Yan has described Mao as "both monster and a genius."[2] Some historians claim that Mao Zedong was "one of the great tyrants of the twentieth century",[222] and a dictator comparable to Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin,[222][223] with a death toll surpassing both.[4][5] In The Black Book of Communism, Jean Louis Margolin writes that "Mao Zedong was so powerful that he was often known as the Red Emperor... the violence he erected into a whole system far exceeds any national tradition of violence that we might find in China."[224] Mao was also frequently compared to China's First Emperor Qin Shi Huang, notorious for burying alive hundreds of scholars, and liked the comparison.[225] During a speech to party cadre in 1958, Mao said he had far outdone Qin Shi Huang in his policy against intellectuals: "He buried 460 scholars alive; we have buried forty-six thousand scholars alive.... You [intellectuals] revile us for being Qin Shi Huangs. You are wrong. We have surpassed Qin Shi Huang a hundredfold."[226] As a result of such tactics, critics have pointed out that:

The People's Republic of China under Mao exhibited the oppressive tendencies that were discernible in all the major absolutist regimes of the twentieth century. There are obvious parallels between Mao's China, Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. Each of these regimes witnessed deliberately ordered mass 'cleansing' and extermination.[223]

Mao's English interpreter Sidney Rittenberg wrote in his memoir The Man Who Stayed Behind that whilst Mao "was a great leader in history", he was also "a great criminal because, not that he wanted to, not that he intended to, but in fact, his wild fantasies led to the deaths of tens of millions of people."[227] Li Rui, Mao's personal secretary, goes further and claims he was dismissive of the suffering and death caused by his policies: "Mao's way of thinking and governing was terrifying. He put no value on human life. The deaths of others meant nothing to him."[228] Biographer Jung Chang goes further still and argues that Mao was well aware that his policies would be responsible for the deaths of millions. While discussing labor-intensive projects such as waterworks and making steel, Chang claims Mao said to his inner circle in November 1958: "Working like this, with all these projects, half of China may well have to die. If not half, one-third, or one-tenth – 50 million – die."[229] Thomas Bernstein of Columbia University argues that this quotation is taken out of context, claiming:

The Chinese original, however, is not quite as shocking. In the speech, Mao talks about massive earthmoving irrigation projects and numerous big industrial ones, all requiring huge numbers of people. If the projects, he said, are all undertaken simultaneously "half of China's population unquestionably will die; and if it's not half, it'll be a third or ten percent, a death toll of 50 million people." Mao then pointed to the example of Guangxi provincial Party secretary, Chén Mànyuǎn (陈漫远) who had been dismissed in 1957 for failing to prevent famine in the previous year, adding: "If with a death toll of 50 million you didn't lose your jobs, I at least should lose mine; whether I should lose my head would also be in question. Anhui wants to do so much, which is quite all right, but make it a principle to have no deaths."[230]

Chang and Halliday take literally Mao's penchant for talking about mass death in highly irresponsible, provocative, callous and reckless ways, exemplified by his famous remark that in a nuclear war, half of China's population would perish but the rest would survive and rebuild. In 1958, when ruminating about the dialectics of life and death, he thought that deaths were beneficial, for without them, there could be no renewal.[citation needed] Imagine, he asked, what a disaster it would be if Confucius were still alive.[citation needed] "When people die there ought to be celebrations."[citation needed] In December 1958 he remarked that "destruction (mièwáng 灭亡, also extinction) [of people] has advantages. One can make fertilizer. You say you can't, but actually you can, but you must be spiritually prepared."[citation needed] The authors note that these kinds of remarks could well have justified the indifference of lower-level cadres to peasant deaths.[citation needed]

Jasper Becker and Frank Dikötter reach a similar conclusion. Becker notes that "archive material gathered by Dikötter... confirms that far from being ignorant or misled about the famine, the Chinese leadership were kept informed about it all the time. And he exposes the extent of the violence used against the peasants":[231]

Mass killings are not usually associated with Mao and the Great Leap Forward, and China continues to benefit from a more favourable comparison with Cambodia or the Soviet Union. But as fresh and abundant archival evidence shows, coercion, terror and systematic violence were the foundation of the Great Leap, and between 1958 to 1962, by a rough approximation, some 6 to 8 per cent of those who died were tortured to death or summarily killed – amounting to at least 3 million victims. Countless others were deliberately deprived of food and starved to death. Many more vanished because they were too old, weak or sick to work – and hence unable to earn their keep. People were killed selectively because they had the wrong class background, because they dragged their feet, because they spoke out or simply because they were not liked, for whatever reason, by the man who wielded the ladle in the canteen.