Roman numerals

Roman numerals, the numeric system used in ancient Rome, employs combinations of letters from the Latin alphabet to signify values. The numbers 1 to 10 can be expressed in Roman numerals as follows:

- I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X.

The Roman numeral system is a cousin of Etruscan numerals. Use of Roman numerals continued after the decline of the Roman Empire. From the 14th century on, Roman numerals began to be replaced in most contexts by more convenient Hindu-Arabic numerals; however this process was gradual, and the use of Roman numerals in some minor applications continues to this day.

Reading Roman numerals

MMXXIV

|

| "2024" as a Roman numeral |

The Roman number system, numerals, is based upon seven symbols to represent numerical values.[1]

| Symbol | Value |

|---|---|

| I | 1 |

| V | 5 |

| X | 10 |

| L | 50 |

| C | 100 |

| D | 500 |

| M | 1,000 |

To make up the rest of the numbers we must combine the symbols, thus adding or subtracting to make a number. So II is two ones, i.e. 2, and XIII is a ten and three ones, i.e. 13. There is no zero in this system, so 207, for example, is CCVII, using the symbols for two hundreds, a five and two ones. 1066 is MLXVI, one thousand, fifty and ten, a five and a one.

Symbols are placed from left to right in order of value, starting with the largest. However, in a few specific cases,[2] to avoid four characters being repeated in succession (such as IIII or XXXX) these can be reduced using subtractive notation as follows:[3][4]

- the numeral I can be placed before V and X to make 4 units (IV) and 9 units (IX) respectively

- X can be placed before L and C to make 40 (XL) and 90 (XC) respectively

- C can be placed before D and M to make 400 (CD) and 900 (CM) according to the same pattern[5]

An example using the above rules would be 1904: this is composed of 1 (one thousand), 9 (nine hundreds), 0 (zero tens), and 4 (four units). To write this numeral, we should treat the non-zero digits separately. Thus 1,000 = M, 900 = CM, and 4 = IV. Therefore, 1904 is MCMIV. This reflects typical modern usage rather than a universally accepted convention: historically numerals have been written less consistently.[6]

A common exception to the practice of placing a smaller value before a larger in order to reduce the number of characters, is the use of IIII instead of IV for 4, especially, although by no means exclusively, on clock faces; see below. Another good example of the additive rather than subtractive form of numbers is at theAdmiralty Arch in London, where DCCCC is used instead of CM for 900 (see illustration). In general, the "rules" about subtractively applied symbols are the most frequently "broken".

Numerals are still used in today's society, for example;

- 1954 as MCMLIV (Trailer for the movie The Last Time I Saw Paris)[7]

- 1990 as MCMXC (The title of musical project Enigma's debut album MCMXC a.D., named after the year of its release.)

- 2008 as MMVIII - the year of the games of the XXIX (29th) Olympiad (in Beijing)

History

Pre-Roman times and Ancient Rome

Numerals were originally written as independent symbols, prior to the Romans. The Etruscans, for example, used I, Λ, X, ⋔, 8, ⊕, for I, V, X, L, C, and M, of which only I and X happened to be letters in their alphabet.

Hypotheses About the Origin of Roman Numerals

Tally sticks

One hypothesis is that the Etrusco-Roman numeral system actually derive from notches on tally sticks, which continued to be used by Italian and Dalmatian shepherds into the 19th century.[8]

Thus, 'I' descends not from the letter 'I' but from a notch scored across the stick. Every fifth notch was double cut i.e. ⋀, ⋁, ⋋, ⋌, etc.), and every tenth was cross cut (X), IIIIΛIIIIXIIIIΛIIIIXII..., much like European tally marks today. This produced a positional system: Eight on a counting stick was eight tallies, IIIIΛIII, or the eighth of a longer series of tallies; either way, it could be abbreviated ΛIII (or VIII), as the existence of a Λ implies four prior notches. By extension, eighteen was the eighth tally after the first ten, which could be abbreviated X, and so was XΛIII. Likewise, number four on the stick was the I-notch that could be felt just before the cut of the Λ (V), so it could be written as either IIII or IΛ (IV). Thus the system was neither additive nor subtractive in its conception, but ordinal. When the tallies were transferred to writing, the marks were easily identified with the existing Roman letters I, V and X. The tenth V or X along the stick received an extra stroke. Thus 50 was written variously as N, И, K, Ψ, ⋔, etc., but perhaps most often as a chicken-track shape like a superimposed V and I: ᗐ. This had flattened to ⊥ (an inverted T) by the time of Augustus, and soon thereafter became identified with the graphically similar letter L. Likewise, 100 was variously Ж, ⋉, ⋈, H, or as any of the symbols for 50 above plus an extra stroke. The form Ж (that is, a superimposed X and I) came to predominate. It was written variously as >I< or ƆIC, was then abbreviated to Ɔ or C, with C variant finally winning out because, as a letter, it stood for [centum] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Latin for "hundred".

The hundredth V or X was marked with a box or circle. Thus 500 was like a Ɔ superimposed on a ⋌ or ⊢ — that is, like a Þ with a cross bar,— becoming D or Ð by the time of Augustus, under the graphic influence of the letter D. It was later identified as the letter D; an alternative symbol for "thousand" was (I) or CIƆ, and half of a thousand or "five hundred" is the right half of the symbol, I) or IƆ, and this may have been converted into D.[9] This at least was the false etymology given to it later on.

Meanwhile, 1000 was a circled or boxed X: Ⓧ, ⊗, ⊕, and by Augustinian times was partially identified with the Greek letter Φ phi. Over time, the symbol changed to Ψ and ↀ. The latter symbol further evolved into ∞, then ⋈, and eventually changed to M under the influence of the Latin word [mille] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "thousand".

Hand signals

Alfred Hooper, a mathematician, has an alternative hypothesis for the origin of the Roman numeral system, for small numbers.[10] Hooper contends that the digits are related to hand signals. For example, the numbers I, II, III, IIII correspond to the number of fingers held up for another to see. V, then represents that hand upright with fingers together and thumb apart. Numbers 6–10, are represented with two hands as follows (left hand, right hand) 6=(V,I), 7=(V,II), 8=(V,III), 9=(V,IIII), 10=(V,V) and X results from either crossing of the thumbs, or holding both hands up in a cross.

Intermediate symbols deriving from few original symbols

A third hypothesis about the origins states that the basic ciphers were I, X, C and Φ (or ⊕) and that the halfthrough ones derived from taking half of those (half a X is V, half a C is L and half a Φ/⊕ is D).[11]

Middle Ages and Renaissance

| Part of a series on |

| Numeral systems |

|---|

| List of numeral systems |

Minuscule (lower case) letters were developed in the Middle Ages, well after the demise of the Western Roman Empire, and lower-case versions of Roman numbers are now also commonly used: i, ii, iii, iv, etc. In the Middle Ages, a j was sometimes substituted for the final i of a number, such as iij for 3 or vij for 7. This j was considered a swash variant of i. The use of a final j is still used in medical prescriptions to prevent tampering with or misinterpretation of a number after it is written.[12][13]

Subtractive numerals (for instance IV for IIII and IX for VIIII) were introduced relatively late (the Romans themselves did without them) and for many years they were applied patchily and inconsistently.

During the Middle Ages, a more comprehensive system was developed in order to represent larger numbers. This system used other letters of the Latin alphabet to signify large numbers, usually those that consisted of repetitions of the same symbol. They are still listed today in most dictionaries, although through disfavor are primarily out of use.[14]

| Modern number |

Medieval abbreviation |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | A | Resembles an upside-down V. Also said to equal 500. |

| 6 | Ϛ | Either a ligature of VI, or the Greek letter stigma (Ϛ), having the same numerical value.[15] |

| 7 | S, Z | Presumed abbreviation of septem, Latin for 7. |

| 11 | O | Presumed abbreviation of (e.g.) onze, French for 11. |

| 40 | F | Presumed abbreviation of English forty. |

| 70 | S | Also could stand for 7, and has same etymology. |

| 80 | R | |

| 90 | N | Presumed abbreviation of nonaginta, Latin for 90. |

| 150 | Y | Possibly derived from the lowercase y's shape. |

| 151 | K | This unusual abbreviation's origin is unknown; it has also been said to stand for 250.[16] |

| 160 | T | Possibly derived from Greek tetra, as 4 x 40 = 160. |

| 200 | H | |

| 250 | E | |

| 300 | B | |

| 400 | P, G | |

| 500 | Q | Redundant with D, abbreviation for quingenti, Latin for 500. |

| 2000 | Z |

Chronograms, messages with a numbers encoded into them, were popular during the Renaissance era. The chronogram would be a phrase containing the letters I, V, X, L, C, D, and M. By putting these letters together, the reader would obtain a number, usually indicating a particular year.

Modern usage

By the 11th century Hindu–Arabic numerals had been introduced into Europe from al-Andalus, by way of Arab traders and arithmetic treatises. However, Roman numerals proved to be persistent, remaining in common use in the "west" well into the 14th and 15th centuries, even in accounting and other business records (where the actual calculations would have been by abacus). Their eventual almost complete replacement by their more convenient "Arabic" equivalents happened quite gradually, in fact Roman numerals are still used today in several niche contexts. A few examples of their current use are:

- Names of monarchs and Popes, e.g. Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, Pope Benedict XVI. These are referred to as regnal numbers; e.g. "II" is pronounced "the second". This tradition began in Europe sporadically in the Middle Ages, gaining widespread use in England only during the reign of Henry VIII. Previously, the monarch was not known by numeral but by an epithet such as Edward the Confessor.

- Generational suffixes, particularly seen in the USA, for people who share the same name across generations, for example William Howard Taft IV.

- The year of production of films, television shows and other works of art within the work itself, which according to BBC News was originally done "in an attempt to disguise the age of films or television programmes."[17] Outside reference to the work will use regular Hindu–Arabic numerals.

- Hour marks on timepieces. In this context 4 is usually written IIII.

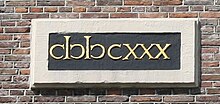

- The year of construction on building faces and cornerstones.

- Page numbering of prefaces and introductions of books.

- Book volume and chapter numbers.

- Sequels of movies, video games, and other works.

- Outlines, which use numbers to show hierarchical relationships.

- Occurrences of a recurring grand event, for instance:

- The Summer and Winter Olympic Games (e.g. the XXI Olympic Winter Games; the Games of the XXX Olympiad)

- The Super Bowl, the annual championship game of the National Football League (e.g. Super Bowl XLVII)

- WrestleMania, the annual professional wrestling event for the WWE (e.g. the forthcoming WrestleMania XXX)

In astronomy, the natural satellites or "moons" of the planets are traditionally designated by a Roman numeral.

In chemistry, numerals are often used to denote the groups of the periodic table. They are also used in the IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry, for the oxidation number of cations which can take on several different positive charges. They are also used for naming phases of polymorphic crystals, such as ice.

In earthquake seismology, numerals are often used to designate degrees of the Mercalli intensity scale.

In music theory, the diatonic functions are identified using Roman numerals. See: Roman numeral analysis. In musical performance practice, individual strings of stringed instruments, such as the violin, are often denoted by numerals, with higher numbers denoting lower strings.

Numerals are also used to denote varying levels of brightness in photography.

Modern non-English-speaking usage

Roman numerals, which are written in capital letters, are used to denote centuries (e.g., XVIII refers to the eighteenth century) in Bulgarian, Croatian, French, Hungarian, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Georgian, and Spanish languages — and occasionally in Engish. This use has largely been replaced by Hindu-Arabic numerals (e.g. 18.) in Czech and Slovak languages.

In Central Europe, Italy, Russia, and in Bulgarian, Croatian, Portuguese, Romanian, and Serbian languages, mixed Roman and Hindu-Arabic numerals are used to record dates (usually on tombstones, but also elsewhere, such as in formal letters and official documents). The month is written in Roman numerals while the day is in Hindu-Arabic numerals: 14. VI. 1789 is 14 June 1789. This use has largely been replaced by Hindu-Arabic numerals (e.g. 14.06.1789) in Czech, Slovene, Slovak, Polish, Portuguese and Russian languages.

In the Baltic and Eastern European nations, numerals are quite often used to represent the days of the week in hours-of-operation signs displayed in windows or on doors of businesses,[18] and also sometimes in railway and bus timetables. Monday is represented by I, which is the initial day of the week. Sunday is represented by VII, which is the final day of the week. The hours of operation signs are tables composed of two columns where the left column is the day of the week in Roman numerals and the right column is a range of hours of operation from starting time to closing time. The following example hours-of-operation table would be for a business whose hours of operation are 9:30 AM to 5:30 PM on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays; 9:30 AM to 7:00 PM on Tuesdays and Fridays; and 9:30 AM to 1:00 PM on Saturdays; and which is closed on Sundays.

| I | 9:30–17:30 |

| II | 9:30–19:00 |

| III | 9:30–17:30 |

| IV | 9:30–17:30 |

| V | 9:30–19:00 |

| VI | 9:30–13:00 |

| VII | — |

In Rome, Greece, Romania, and other European countries to a lesser extent,[19][20] numerals are used for floor numbering. Likewise, apartments in central Amsterdam are indicated as 138-III, with both an Hindu-Arabic numeral (number of the block or house) and a Roman numeral (floor number). The apartment on the ground floor is indicated as '138-huis'.

In Italy, where roads outside built-up areas have kilometer signs, major roads and motorways also mark 100-metre subdivisionals, using Roman numerals from I to IX for the smaller intervals. The sign IX | 17 thus marks km. 17·900.

Special values

Zero

The number zero does not have its own numeral, but instead the word nulla (the Latin word meaning "none") was used by medieval computists in lieu of 0. Dionysius Exiguus was known to use nulla alongside numerals in 525AD.[21][22] About 725, Bede or one of his colleagues used the letter N, the initial of nulla, in a table of epacts, all written in Roman numerals.[23]

Fractions

Though the Romans used a decimal system for whole numbers, reflecting how they counted in Latin, they used a duodecimal system for fractions, because the divisibility of twelve (12 = 3 × 2 × 2) makes it easier to handle the common fractions of 1/3 and 1/4 than does a system based on ten (10 = 2 × 5). On coins, many of which had values that were duodecimal fractions of the unit [as] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), they used a tally-like notational system based on twelfths and halves. A dot (•) indicated an [uncia] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "twelfth", the source of the English words inch and ounce; dots were repeated for fractions up to five twelfths. Six twelfths (one half) was abbreviated as the letter S for [semis] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "half". Uncia dots were added to S for fractions from seven to eleven twelfths, just as tallies were added to V for whole numbers from six to nine.[24]

Each of these fractions had a name, which was also the name of the corresponding coin:

| Fraction | Roman Numeral | Name (nominative and genitive) | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1/12 | • | [uncia, unciae] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | "ounce" |

| 2/12 = 1/6 | •• or : | [sextans, sextantis] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | "sixth" |

| 3/12 = 1/4 | ••• or ∴ | [quadrans, quadrantis] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | "quarter" |

| 4/12 = 1/3 | •••• or :: | [triens, trientis] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | "third" |

| 5/12 | ••••• or :·: | [quincunx, quincuncis] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | "five-ounce" (quinque unciae → quincunx) |

| 6/12 = 1/2 | S | [semis, semissis] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | "half" |

| 7/12 | S• | [septunx, septuncis] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | "seven-ounce" (septem unciae → septunx) |

| 8/12 = 2/3 | S•• or S: | [bes, bessis] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | "twice" (as in "twice a third") |

| 9/12 = 3/4 | S••• or S:· | [dodrans, dodrantis] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) or [nonuncium, nonuncii] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

"less a quarter" (de-quadrans → dodrans) or "ninth ounce" (nona uncia → nonuncium) |

| 10/12 = 5/6 | S•••• or S:: | [dextans, dextantis] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) or [decunx, decuncis] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) |

"less a sixth" (de-sextans → dextans) or "ten ounces" (decem unciae → decunx) |

| 11/12 | S••••• or S:·: | [deunx, deuncis] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | "less an ounce" (de-uncia → deunx) |

| 12/12 = 1 | I | [as, assis] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | "unit" |

The arrangement of the dots was variable and not necessarily linear. Five dots arranged like (:·:) (as on the face of a die) are known as a quincunx from the name of the Roman fraction/coin. The Latin words sextans and quadrans are the source of the English words sextant and quadrant.

Other Roman fractions include the following:

- 1/8 [sescuncia, sescunciae] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (from sesqui- + uncia, i.e. 1½ uncias), represented by a sequence of the symbols for the semuncia and the uncia.

- 1/24 [semuncia, semunciae] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (from semi- + uncia, i.e. ½ uncia), represented by several variant glyphs deriving from the shape of the Greek letter Sigma (Σ), one variant resembling the pound sign (£) without the horizontal line(s) and another resembling the Cyrillic letter (Є).

- 1/36 [binae sextulae, binarum sextularum] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("two sextulas") or [duella, duellae] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), represented by (ƧƧ), a sequence of two reversed Ss.

- 1/48 [sicilicus, sicilici] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), represented by (Ɔ), a reversed C.

- 1/72 [sextula, sextulae] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (1/6 of an uncia), represented by (Ƨ), a reversed S.

- 1/144 = 12−2 [dimidia sextula, dimidiae sextulae] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("half a sextula"), represented by (ƻ), a reversed S crossed by a horizontal line.

- 1/288 [scripulum, scripuli] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (a scruple), represented by the symbol (℈).

- 1/1728 = 12−3 [siliqua, siliquae] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), represented by a symbol resembling closing guillemets (»).

Large numbers

In the Middle Ages, a horizontal line was used above a particular numeral to represent one thousand times that numeral, and additional vertical lines on both sides of the numeral to denote one hundred times the number, as in these examples:

- I for one thousand

- V for five thousand

- |I| for one hundred thousand

- |V| for five hundred thousand

The same overline was also used with a different meaning, to clarify that the characters were numerals. Sometimes both underline and overline were used, e. g. MCMLXVII, and in certain (serif) typefaces, particularly Times New Roman, the capital letters when used without spaces simulates the appearance of the under/over bar, e.g. MCMLXVII.

Sometimes 500, usually D, was written as original |Ɔ, while 1,000, usually M, was written as original C|Ɔ. This is a system of encasing numbers to denote thousands (imagine the Cs and Ɔs as parentheses), which has its origins in Etruscan numeral usage. The D and M used to represent 500 and 1,000 were most likely derived from IƆ and CIƆ, respectively, and subsequently influenced by assumed abbreviations.

An extra Ɔ denoted 500, and multiple extra Ɔs are used to denote 5,000, 50,000, etc. For example:

| Base number | CIƆ = 1,000 | CCIƆƆ = 10,000 | CCCIƆƆƆ = 100,000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 extra Ɔ | IƆ = 500 | CIƆƆ = 1,500 | CCIƆƆƆ = 10,500 | CCCIƆƆƆƆ = 100,500 |

| 2 extra Ɔs | IƆƆ = 5,000 | CCIƆƆƆƆ = 15,000 | CCCIƆƆƆƆƆ = 105,000 | |

| 3 extra Ɔs | IƆƆƆ = 50,000 | CCCIƆƆƆƆƆƆ = 150,000 |

Sometimes CIƆ was reduced to ↀ for 1,000. John Wallis is often credited for introducing the symbol for infinity (modern ∞), and one conjecture is that he based it on this usage, since 1,000 was hyperbolically used to represent very large numbers. Similarly, IƆƆ for 5,000 was reduced to ↁ; CCIƆƆ for 10,000 to ↂ; IƆƆƆ for 50,000 to ↇ; and CCCIƆƆƆ for 100,000 to ↈ.

"IIII" on clocks

Clock faces that are labeled using Roman numerals conventionally show IIII for four o'clock and IX for nine o'clock, using the subtractive principle in one case and not the other. There are many suggested explanations for this:

- Many clocks use IIII because that was the tradition established by the earliest surviving clock, which is the Wells Cathedral clock built between 1386 and 1392. It used IIII because that was the typical method used to denote 4 in contemporary manuscripts (as iiij or iiii). That clock had an asymmetrical 24-hour dial and used Hindu-Arabic numerals for a minute dial and a moon dial, so theories depending on a symmetrical 12-hour clock face do not apply.[25]

- Perhaps IV was avoided because IV represented the Roman god Jupiter, whose Latin name, IVPPITER, begins with IV. This suggestion has been attributed to Isaac Asimov.[26]

- Louis XIV, king of France, who preferred IIII over IV, ordered his clockmakers to produce clocks with IIII and not IV, and thus it has remained.[27]

- Using standard numerals, two sets of figures would be similar and therefore confusable by children and others unused to reading clockfaces: IV and VI are similar, as are IX and XI. As the first pair are upside down on the face, an additional level of confusion would be introduced—a confusion avoided by using IIII to provide a clear distinction from VI.

- The four-character form IIII creates a visual symmetry with the VIII on the other side, which the two-character IV would not.

- With IIII, the number of symbols on the clock totals twenty Is, four Vs, and four Xs,[28] so clock makers need only a single mould with a V, five Is, and an X in order to make the correct number of numerals for their clocks: VIIIIIX. This is cast four times for each clock and the twelve required numerals are separated:

- V IIII IX

- VI II IIX

- VII III X

- VIII I IX

- The IIX and one of the IXs are rotated 180° to form XI and XII. The alternative with IV uses seventeen Is, five Vs, and four Xs, requiring the clock maker to have several different patterns.

- Only the I symbol would be seen in the first four hours of the clock, the V symbol would only appear in the next four hours, and the X symbol only in the last four hours. This would add to the clock's radial symmetry.

A well-known exception to the conventional use of IIII on clock faces with Roman numerals is the clock in Elizabeth Tower (often erroneously called "Big Ben") on the Palace of Westminster in London. It uses IV for four o'clock.

See also

References

- ^ Alphabetic symbols for larger numbers, such as Q for 500,000, have also been used to various degrees of standardization.Gordon, Arthur E. (1982). Illustrated Introduction to Latin Epigraphy. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520050797.

- ^ Reddy, Indra K.; Khan, Mansoor A. (2003). Essential Math and Calculations for Pharmacy Technicians. CRC Press.

- ^ Dela Cruz, M. L. P.; Torres, H. D. (2009). Number Smart Quest for Mastery: Teacher's Edition. Rex Bookstore, Inc.

- ^ Martelli, Alex; Ascher, David (2002). Python Cookbook. O'Reilly Media Inc.

- ^ Stroh, Michael. Trick question: How to spell 1999? Numerals: Maybe the Roman Empire fell because their computers couldn't handle calculations in Latin. The Baltimore Sun, December 27, 1998.

- ^ Adams, Cecil (February 23, 1990). "The Straight Dope". The Straight Dope.

- ^ Hayes, David P. "Guide to Roman Numerals". Copyright Registration and Renewal Information Chart and Web Site.

- ^ Ifrah, Georges (2000). The Universal History of Numbers: From Prehistory to the Invention of the Computer. Translated by David Bellos, E. F. Harding, Sophie Wood, Ian Monk. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1966, 1977). Asimov On Numbers. Pocket Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 9.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Alfred Hooper. The River Mathematics (New York, H. Holt, 1945).

- ^ Keyser, Paul (1988). "The Origin of the Latin Numerals 1 to 1000". American Journal of Archaeology. 92: 529–546.

- ^ Sturmer, Julius W. Course in Pharmaceutical and Chemical Arithmetic, 3rd ed. (LaFayette, IN: Burt-Terry-Wilson, 1906). p25 Retrieved on 2010-03-15.

- ^ Bastedo, Walter A. Materia Medica: Pharmacology, Therapeutics and Prescription Writing for Students and Practitioners, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders, 1919) p582 Retrieved on 2010-03-15.

- ^ Capelli, A. Dictionary of Latin Abbreviations. 1912.

- ^ Perry, David J. Proposal to Add Additional Ancient Roman Characters to UCS.

- ^ Bang, Jørgen. Fremmedordbog, Berlingske Ordbøger, 1962 (Danish)

- ^ Owen, Rob (January 13, 2012). "TV Q&A: ABC News, 'Storage Wars' and 'The Big Bang Theory'". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Beginners latin, Nationalarchives.gov.uk, Retrieved December 1, 2013

- ^ Roman Arithmetic, Southwestern Adventist University, Retrieved December 1, 2013

- ^ Roman Numerals History, Retrieved December 1, 2013

- ^ Faith Wallis, trans. Bede: The Reckoning of Time (725), Liverpool: Liverpool Univ. Pr., 2004. ISBN 0-85323-693-3.

- ^ Byrhtferth's Enchiridion (1016). Edited by Peter S. Baker and Michael Lapidge. Early English Text Society 1995. ISBN 978-0-19-722416-8.

- ^ C. W. Jones, ed., Opera Didascalica, vol. 123C in Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina.

- ^ Maher, David W.; Makowski, John F., "Literary Evidence for Roman Arithmetic with Fractions", Classical Philology 96 (2011): 376–399.

- ^ Paul Lewis, Clocking the fours: A new theory about IIII; see the clock

- ^ http://www.voxinghistory.com/?tag=roman_numerals

- ^ W.I. Milham, Time & Timekeepers (New York: Macmillan, 1947) p. 196

- ^ FAQ: Roman IIII vs. IV on Clock Dials – Donn Lathrop's page on IIII vs. IV.

- Menninger, Karl (1992). Number Words and Number Symbols: A Cultural History of Numbers. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-27096-8.

External links

- FAQ No. 1 Why do clocks with Roman numerals use "IIII" instead of "IV"?:

- Child friendly roman numerals webquest

- French book with 841 chapters, numbered up to DCCCXLI

- Roman ad Arabic numerus racio et vice versa

- CESCNC - a handy and easy-to use numeral converter

- Online converter of Roman numerals into Arabic numbers with check of correct notation and random tests