First Turkic Khaganate

First Turkic Khaganate | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 552 – 603 | |||||||||||||

The Turkic Khaganate at its greatest extent, in 576. | |||||||||||||

| Status | Khaganate (Nomadic empire) | ||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||||||

| Religion | Tengrism | ||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Türük Türk | ||||||||||||

| Qaghan | |||||||||||||

• 551–552 | Bumïn Qaγan | ||||||||||||

• 553–572 | Muqan Qaγan | ||||||||||||

• 572–581 | Tatpar Qaγan | ||||||||||||

• 581 | Umna Qaγan | ||||||||||||

• 581–587 | Ishbara Qaγan | ||||||||||||

• 581–587 | Apa Qaγan | ||||||||||||

• 587–589 | Bagha Qaγan | ||||||||||||

• 589–599 | Tulan Qaγan | ||||||||||||

• 599–603 | Tardu Qaγan | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Kurultai[citation needed] | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Post-classical | ||||||||||||

• Bumin Qaghan revolts against Rouran Khaganate | 542 | ||||||||||||

• Established | 552 | ||||||||||||

• Death of Tatpar Qaγan initiates the Göktürk civil war | 581 | ||||||||||||

• Brief re-unification | 603 | ||||||||||||

• Division of Western and Eastern Turkic Khaganates | 603 | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 557[8][9] | 6,000,000 km2 (2,300,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

The First Turkic Khaganate (Template:Lang-otk;[10] Chinese: 突厥汗國; pinyin: Tūjué hánguó, also referred to as First Turkic Empire,[11] Turkic Khaganate or Göktürk Khaganate), was a khaganate established by the Ashina clan of the Göktürks in medieval Inner Asia. Under the leadership of Bumin Qaghan (d. 552) and his brother Istämi. The First Turkic Khaganate succeeded Rouran Khaganate as the hegemonic power of the Mongolian Plateau and rapidly expanded their territories in Central Asia. Initially the Khaganate would use Sogdian in official and numismatic functions. Although the Göktürks spoke Old Turkic, the Khaganate's early official texts and coins were written in Sogdian.[2][12] It was the first Turkic state to use the name Türk politically.[13] Old Turkic script was invented at the first half of the 6th century.[14][15]

It was the first Central Asian transcontinental empire from Manchuria to the Black Sea.[16]

It collapsed in 603, after a series of conflicts and civil wars which separated the polity into the Eastern Turkic Khaganate and Western Turkic Khaganate. The Tang Empire conquered the Eastern Turkic Khaganate in 630 and the Western Turkic Khaganate in 657 in a series of military campaigns. The Second Turkic Khaganate emerged in 682 and lasted until 744 when it was overthrown by the Uyghur Khaganate.

First Khaganate

The origins of the Turkic Khanate trace back to 546, when Bumin Qaghan made a preemptive strike against the Uyghur and Tiele groups planning a revolt against their overlords, the Rouran Khanate. For this service he expected to be rewarded with a Rouran princess, thus marrying into the royal family. However, the Rouran khagan, Yujiulü Anagui, sent an emissary to Bumin to rebuke him, saying, "You are my blacksmith slave. How dare you utter these words?" As Anagui's "blacksmith slave" (Chinese: 鍛奴; pinyin: duànnú) comment was recorded in Chinese chronicles, some claim that the Göktürks were indeed blacksmith servants for the Rouran elite,[17][18][19][20] and that "blacksmith slavery" may have indicated a form of vassalage within Rouran society.[21] According to Denis Sinor, this reference indicates that the Türks specialized in metallurgy, although it is unclear if they were miners or, indeed, blacksmiths.[22][23] Whatever the case, that the Turks were "slaves" need not be taken literally, but probably represented a form of vassalage, or even unequal alliance.[24]

A disappointed Bumin allied with the Western Wei against the Rouran, their common enemy. In 552, Bumin defeated Anagui and his forces north of Huaihuang (modern Zhangjiakou, Hebei).[25]

Having excelled both in battle and diplomacy, Bumin declared himself Illig Khagan of the new khanate at Otukan, but died a year later. His son, Muqan Qaghan, defeated the Hephthalite Empire,[26] Khitan and Kyrgyz.[27] Bumin's brother Istämi (d. 576) bore the title "Yabgu of the West" and collaborated with the Sassanid Empire of Iran to defeat and destroy the Hephthalites, who were allies of the Rouran. This war tightened the Ashina clan's grip on the Silk Road.

The appearance of the Pannonian Avars in the West has been interpreted as a nomadic faction fleeing the westward expansion of the Göktürks, although the specifics are a matter of irreconcilable debate given the lack of clear sources and chronology. Rene Grousset links the Avars with the downfall of the Hephthalites rather than the Rouran,[28] while Denis Sinor argues that Rouran-Avar identification is "repeated from article to article, from book to book with no shred of evidence to support it".[29]

Istämi's policy of western expansion brought the Göktürks into Europe.[30] In 576 the Göktürks crossed the Kerch Strait into the Crimea. Five years later they laid siege to Chersonesus; their cavalry kept roaming the steppes of Crimea until 590.[31] As for the southern borders, they were drawn south of the Amu Darya, bringing the Ashina into conflict with their former allies, the Sasanian Empire. Much of Bactria (including Balkh) remained a dependency of the Ashina until the end of the century.[31]

-

Gold Mask Inlaid with Rubies, probably belonging to the Turkic Empire of Central Asia. 5th - 6th century CE. Excavated at Boma Tomb in Zhaosu County, Xinjiang. Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture Museum collection.[32]

-

Göktürk petroglyphs from Mongolia (6th to 8th century).[33]

-

The First Turkic Khaganate.

Relation with the Byzantine Empire

The first Türk delegation arrived in Constantinople was in 563. It had been sent by Askel, head of the first tribe of the Nushibi tribal federation of the Western Türks. It was followed five years later by a more substantial trade delegation headed by a Sogdian called Maniakh. He was received by Emperor Justin II, who was more interested in securing an ally to the rear of the Sasanians than in the importation of silk. According to the Byzantine historian Menander, the Türk ruler on whose behalf Maniakh negotiated was Silziboulos. Silziboulos and his son Turxath were minor rulers in the westernmost parts of the Türk Empire, perhaps on the same level of authority as the previously mentioned Askel. Menander clearly states that Turxath was but one of the eight chiefs among whom rule over the Türks was divided. On his return journey, Maniakh was accompanied by a Byzantine counter embassy led by the strategos Zemarkhos, who was, in his turn, very well received by Silziboulos. Other diplomatic exchanges followed until 572 when, on his second mission to the Türks, the Byzantine envoy Valentine was received by Turxath, son of the just deceased Silziboulos. In sign of mourning, members of the Byzantine delegation were not only requested to lacerate their faces, but were given a bitterly hostile reception by Turxath, who accused the Byzantine emperor of treason for having given asylum to the Avars, whom they considered to be fugitive subjects of the Türks. At that time the principal ruler of the Western Frontier Region of the Türk Empire was Tardu, son of Istemi.[35]

Civil war

The Turkic Khanate split in two after the death of the fourth ruler, Taspar Qaghan, c. 584. He had willed the title of khagan to Muqan's son Apa Qaghan, but the high council appointed Ishbara Qaghan instead. Factions formed around both leaders. Before long, four rivals claimed the title. They were successfully played off against each other by Sui and Tang China.[citation needed]

The most serious contender was the western one, Istämi's son Tardu, a violent and ambitious man who had already declared himself independent from the Qaghan after his father's death. He now seized the title and led an army east to claim the seat of imperial power, Otukan.[citation needed]

In order to buttress his position, Ishbara of the Eastern Khaganate applied to Emperor Yang of Sui for protection. Tardu attacked Chang'an, the Sui capital, around 600, demanding Emperor Yangdi end his interference in the civil war. In retaliation, Chinese diplomacy successfully incited a revolt of Tardu's Tiele vassals, which led to the end of Tardu's reign in 603. Among the dissident tribes were the Uyghurs and Xueyantuo.[citation needed]

Eastern Turkic Khaganate

The civil war left the empire divided into eastern and western parts. The eastern part, still ruled from Otukan, remained in the orbit of the Sui and retained the name Göktürk. The Shibi Khan (609–619) and Illig Qaghan (620–630) attacked China at its weakest moment during the transition between the Sui and Tang. Shibi Khan's surprise attack against Yanmen Commandery during an imperial tour of the northern frontier almost captured Emperor Yang, but his Chinese wife Princess Yicheng—who had been well treated by Empress Xiao during an earlier visit—sent a warning ahead, allowing the emperor and empress time to flee to the commandery seat at present-day Daixian in Shanxi.[44] This was besieged by the Turkic army on September 11, 615,[45][46] but Chinese reinforcements and a false report from Princess Yicheng to her husband about a northern attack on the khaganate caused him to lift the siege before its completion.[44]

In 626, Illig Qaghan took advantage of the Xuanwu Gate Incident and drove on to Chang'an. On September 23, 626,[47] Illig Qaghan and his iron cavalry reached the bank of the Wei River north of Bian Bridge (in present-day Xianyang, Shaanxi). On September 25, 626,[48] Li Shimin (later Emperor Taizong of Tang) and Illig Qaghan formed an alliance by sacrificing a white horse on Bian Bridge. The Tang paid compensation and promised further tribute, so Illig Qaghan ordered his iron cavalry to withdraw. This is known as the Alliance of the Wei River (渭水之盟), or the Alliance of Bian Qiao (便橋會盟 / 便桥会盟).[49] All in all, 67 incursions on Chinese territories were recorded.[31]

Before mid-October 627, heavy snows on the Mongolian-Manchurian grassland covered the ground to a depth of several feet, preventing the nomads' livestock from grazing and causing a massive die-off among the animals.[50] According to the New Book of Tang, in 628, Taizong mentioned that "There has been a frost in midsummer. The sun had risen from same place for five days. The moon had had the same light level for three days. The field was filled with red atmosphere (dust storm)."[51]

Illig Qaghan was brought down by a revolt of his Tiele vassal tribes (626–630), allied with Emperor Taizong of Tang. This tribal alliance figures in Chinese records as the Huihe (Uyghur).[52]

On March 27, 630,[53] a Tang army under the command of Li Jing defeated the Eastern Turkic Khaganate under the command of Illig Qaghan at the Battle of Yinshan (陰山之戰 / 阴山之战).[54][55][56] Illig Qaghan fled to Ishbara Shad, but on May 2, 630[57] Zhang Baoxiang's army advanced to Ishbara Shad's headquarters. Illig Qaghan was taken prisoner and sent to Chang'an.[56] The Eastern Turkic Khaganate collapsed and was incorporated into the Jimi system of Tang. Emperor Taizong said, "It's enough for me to compensate my dishonor at Wei River."[55]

Western Turkic Khaganate

The Western khagan Sheguy and Tong Yabghu Qaghan constructed an alliance with the Byzantine Empire against the Sasanian Empire and succeeded in restoring the southern borders along the Tarim and Amu Darya rivers. Their capital was Suyab in the Chu River valley, about 6 km south east of modern Tokmok. In 627 Tung Yabghu, assisted by the Khazars and Emperor Heraclius, launched a massive invasion of Transcaucasia which culminated in the taking of Derbent and Tbilisi (see the Third Perso-Turkic War for details). In April 630 Tung's deputy Böri Shad sent the Göktürk cavalry to invade Armenia, where his general Chorpan Tarkhan succeeded in routing a large Persian force. Tung Yabghu's murder in 630 forced the Göktürks to evacuate Transcaucasia.[citation needed]

Western Turkic Khaganate was modernized through an administrative reform of Ashina clan (reigned 634–639) and came to be known as the Onoq.[60] The name refers to the "ten arrows" that were granted by the khagan to ten leaders (shads) of its two constituent tribal confederations, the Duolu (five churs) and Nushibi (five irkins), whose lands were divided by the Chui River.[60] The division fostered the growth of separatist tendencies. Soon, chieftain Kubrat of the Dulo clan, whose relation ship with the Duolu is possible but not proven, seceded from the Khaganate. The Tang dynasty campaigned against the khaganate and its vassals, the oasis states of the Tarim Basin. The Tang campaign against Karakhoja in 640 led to the retreat of the Western Turks, who were defeated during the Tang campaigns against Karasahr in 644 and the Tang campaign against Kucha in 648, [61][62] leading to the 657 conquest of the Western Turks by the Tang general Su Dingfang.[63] Emperor Taizong of Tang was proclaimed Khagan of the Göktürks.

In 657, the emperor of China could impose indirect rule along the Silk Road as far as Iran. He installed two khagans to rule the ten arrows (tribes) of Göktürks. Five arrows of Tulu (咄陆) were ruled by khagans bearing the title of Xingxiwang (興昔亡可汗) while five arrows of Nushipi (弩失畢可汗) were ruled by Jiwangjue (繼往絕可汗). Five Tulu corresponded to the area east of Lake Balkash while five arrows of Nushipi corresponded to the land east of the Aral Sea. Göktürks now carried Chinese titles and fought by their side in their wars. The era spanning from 657–699 in the steppes was characterized by numerous rulers – weak, divided, and engaged in constant petty wars under the Anxi Protectorate until the rise of Turgesh.

Customs and culture

Political system

The Göktürks were governed by Kurultai, a political and military council of khans and other high ranking leaders, such as aqsaqals.[65][page needed]

Religion

The Göktürks and other ancient Turkic peoples were mainly adherents of Tengrism, worshipping the sky god Tengri. The Khaganate received missionaries from the Buddhist religion, which was incorporated into Tengrism. After the fall of the khaganate, many refugees settled in Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe, and adopted the Islamic faith.

Culinary

According to Nevin Halıcı, ayran is a traditional Turkic drink that was consumed by nomadic Turks prior to 1000 CE.[66] According to Celalettin Koçak and Yahya Kemal Avşar (Professor of Food Engineering at Mustafa Kemal University), ayran was first developed thousands of years ago by the Göktürks, who would dilute bitter yogurt with water in an attempt to improve its flavor.[67]

Gallery

-

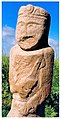

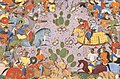

Shahnameh illustration of Bahram Chobin and Bagha Qaghan fighting.

-

Ceramic figures of the Göktürks from the Tang Dynasty period, Mongolia (7th century).

-

Map of the First Turkic kaganate circa 570.

-

A fresh ayran

See also

| History of the Turkic peoples pre–14th century |

|---|

|

| History of Central Asia |

|---|

|

- Bain Tsokto inscriptions

- Göktürk family tree

- History of the Turkic peoples

- Turks in the Tang military

- Horses in East Asian warfare

- Kangly

- Orkhon inscription (Khöshöö Tsaidam Monuments)

- Kürşat (hero)

- Orkhon script

- Qaghans of the Turkic khaganates

- Timeline of the Turkic peoples (500–1300)

- Bumin Qaghan

- Oghuz Turks

- Ashina tribe

- Ashide

References

- ^ "The tamga of the royal clan of the first Turkish empire was a neatly drawn lineal picture of an ibex", Kljastornyj, 1980, p. 93

- ^ a b Roux 2000, p. 79.

- ^ Vovin 2019, p. 133.

- ^ Sinor 1969, p. 101.

- ^ Peter Roudik, (2007), The History of the Central Asian Republics, p. 24

- ^ Peter B. Golden, (2011), Central Asia in World History, p 37

- ^ Lirong, M. A. "Sino-Turkish Cultural Ties under the Framework of Silk Road Strategy". In Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies (in Asia). Volume 8, No. 2, June 2014

- ^ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D. (December 2006). "East–West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ Taagepera, Rein (1979). "Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D.". Social Science History. 3 (3/4): 129. doi:10.2307/1170959. JSTOR 1170959.

- ^ Mirkamal, Aydar (15 June 2015). "Kültegin ve Bilge Kağan Yazıtlarındaki İdi O(o)qs(u)z Sözü Üzerine". Uluslararası Türkçe Edebiyat Kültür Eğitim (Teke) Dergisi. 4 (1): 16–24.

- ^ Luc Kwanten, (1979), Imperial Nomads: A History of Central Asia, 500-1500, p. 35

- ^ Baratova 2005.

- ^ West, Barbara A. (19 May 2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 829. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

The first people to use the ethnonym Turk to refer to themselves were the Turuk people of the Gokturk Khanate in the mid sixth-century

- ^ Mouton, 2002, Archivum Ottomanicum, p. 49

- ^ Sigfried J. de Laet, Joachim Herrmann, (1996), History of Humanity: From the seventh century B.C. to the seventh century A.D., p. 478

- ^ Peter Benjamin Golden, (2010), Central Asia in World History, p. 49

- ^ 馬長壽, 《突厥人和突厥汗國》, 上海人民出版社, 1957,p. 10–11 (in Chinese)

- ^ 陳豐祥, 余英時, 《中國通史》, 五南圖書出版股份有限公司, 2002, ISBN 978-957-11-2881-8, p. 155 (in Chinese)

- ^ Gao Yang, "The Origin of the Turks and the Turkish Khanate", X. Türk Tarih Kongresi: Ankara 22 – 26 Eylül 1986, Kongreye Sunulan Bildiriler, V. Cilt, Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1991, s. 731. (in English)

- ^ Burhan Oğuz, Türkiye halkının kültür kökenleri: Giriş, beslenme teknikleri, İstanbul Matbaası, 1976, p. 147. «Demirci köle» olmaktan kurtulup reisleri Bumin'e (in Turkish)

- ^ Larry W. Moses, "Relations with the Inner Asian Barbarian", ed. John Curtis Perry, Bardwell L. Smith, Essays on Tʻang society: the interplay of social, political and economic forces, Brill Archive, 1976, ISBN 978-90-04-04761-7, p. 65. '"Slave" probably meant vassalage to the Juan Juan [=Ruanruan or Rouran] qaghan, whom they [the Türks] served in battle by providing iron weapons, and also marching with the qaghan's armies.' (in English)

- ^ Denis Sinor, Inner Asia: history-civilization-languages : a syllabus, Routledge, 1997, ISBN 978-0-7007-0380-7, p. 26. Contacts had already begun in 545 A.D. between the so-called "blacksmith-slave" Türk and certain of the kingdoms of north China,

- ^ Denis Sinor, ibid, p. 101. 'Beyond A-na-kui's disdainful reference to his "blacksmith slaves" there is ample evidence to show that the Turks were indeed specializing in metallurgy, though it is difficult to establish whether they were miners or rather blacksmiths.' (in English)

- ^ Nachaeva (2011)

- ^ Linghu Defen et al., Book of Zhou, Vol. 50. (in Chinese)

- ^ Li Yanshou (李延寿), History of Northern Dynasties, Vol. 99.

- ^ Sima Guang, Zizhi Tongjian, Vol. 166.

- ^ Grousset (1970, p. 82)

- ^ History and historiography of the Nomad Empires of Central Eurasia. D Sinor. Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientarum Hung. 58 (1) 3 – 14, 2005

- ^ Walter Pohl, Die Awaren: ein Steppenvolk im Mitteleuropa, 567–822 n. Chr, C.H.Beck (2002), ISBN 978-3-406-48969-3, p. 26–29.

- ^ a b c Grousset 81.

- ^ Giumlía-Mai, Alessandra (2013). "METALLURGY AND TECHNOLOGY OF THE HUNNIC GOLD HOARD FROM NAGYSZÉKSÓS" (PDF). The Silkroad Foundation: 21, Fig 14.

- ^ ALTINKILIÇ, Dr. Arzu Emel (2020). "Göktürk giyim kuşamının plastik sanatlarda değerlendirilmesi" (PDF). Journal of Social and Humanities Sciences Research: 1101-1110.

- ^ Kubik, Adam (2018). "The Kizil Caves as an terminus post quem of the Central and Western Asiatic pear-shape spangenhelm type helmets The David Collection helmet and its place in the evolution of multisegmented dome helmets, Historia i Świat nr 7/2018, 141-156". Historia i Swiat. 7: 145–148.

- ^ D. Sinor and S. G. Klyashtorny, The Türk Empire, p. 333

- ^ ALTINKILIÇ, Dr. Arzu Emel (2020). "Göktürk giyim kuşamının plastik sanatlarda değerlendirilmesi" (PDF). Journal of Social and Humanities Sciences Research: 1101-1110.

- ^ Narantsatsral, D. "THE SILK ROAD CULTURE AND ANCIENT TURKISH WALL PAINTED TOMB" (PDF). The Journal of International Civilization Studies.

- ^ Cosmo, Nicola Di; Maas, Michael. Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, ca. 250–750. Cambridge University Press. pp. 350–354. ISBN 978-1-108-54810-6.

- ^ Baumer, Christoph. History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 185–186. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- ^ ALTINKILIÇ, Dr. Arzu Emel (2020). "Göktürk giyim kuşamının plastik sanatlarda değerlendirilmesi" (PDF). Journal of Social and Humanities Sciences Research: 1101-1110.

- ^ Narantsatsral, D. "THE SILK ROAD CULTURE AND ANCIENT TURKISH WALL PAINTED TOMB" (PDF). The Journal of International Civilization Studies.

- ^ Cosmo, Nicola Di; Maas, Michael. Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, ca. 250–750. Cambridge University Press. pp. 350–354. ISBN 978-1-108-54810-6.

- ^ Baumer, Christoph. History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 185–186. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- ^ a b Xiong (2006), pp. 63–4.

- ^ 大業十一年 八月癸酉 Academia Sinica Archived 2010-05-22 at the Wayback Machine (in Chinese)

- ^ Sima Guang, Zizhi Tongjian, Vol. 182. (in Chinese)

- ^ 武德九年 八月癸未 Academia Sinica Archived 2010-05-22 at the Wayback Machine (in Chinese)

- ^ 武德九年 八月乙酉 Academia Sinica Archived 2010-05-22 at the Wayback Machine (in Chinese)

- ^ Sima Guang, Zizhi Tongjian, Vol. 191. (in Chinese)

- ^ David Andrew Graff, Medieval Chinese warfare, 300–900, Routledge, 2002, ISBN 978-0-415-23955-4, p. 186.

- ^ Ouyang Xiu, New Book of Tang, Vol. 215-I (in Chinese)

- ^ Liu 劉, Xu 昫 (945). Old Book of Tang 舊唐書 Vol.194 & Vol.195.

- ^ 貞觀四年 二月甲辰 Academia Sinica Archived 2010-05-22 at the Wayback Machine (in Chinese)

- ^ Old Book of Tang, Vol. 3. (in Chinese)

- ^ a b Ouyang Xiu et al., New Book of Tang, Vol. 93. (in Chinese)

- ^ a b Sima Guang, Zizhi Tongjian, Vol. 193. (in Chinese)

- ^ 貞觀四年 三月庚辰

- ^ Baumer, Christoph. History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- ^ Grenet, Frantz (2004). "Maracanda/Samarkand, une métropole pré-mongole". Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales. 5/6: Fig. B.

- ^ a b Gumilev 238.

- ^ Grousset 1970, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Wechsler 1979, pp. 225–228.

- ^ Skaff 2009, p. 183.

- ^ Tafazzoli, A. (2003), "Iranian Languages," in C. E. Bosworth and M. S. Asimov, History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume IV: The Age of Achievement, A.D. 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited, p 323.

- ^ Balaban, Ayhan (2006), İskit, Hun ve Göktürklerde Sosyal ve Ekonomik Hayat (PDF) (in Turkish), T.C. Gazi Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-12-11, retrieved 11 December 2011

- ^ Halici, Nevin (Winter 2001). "Turkish Delights". Gastronomica: The Journal of Critical Food Studies. 1 (1). University of California Press: 92–93. doi:10.1525/gfc.2001.1.1.92.

- ^ Kocak, C., Avsar, Y. K., 2009. "Ayran: Microbiology and Technology". In: Yildiz, F. (Ed.), Development and Manufacture of Yogurt and Functional Dairy Products. CRC Press, Boca Raton, U.S., pp. 123–141.

External links

Bibliography

- Asimov, M.S. (1998), History of civilizations of Central Asia Volume IV The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century Part One The historical, social and economic setting, UNESCO Publishing

- Baratova, Larissa (2005). "Turko-Sogdian Coinage". Encyclopedia Iranica.

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- Benson, Linda (1998), China's last Nomads: the history and culture of China's Kazaks, M.E. Sharpe

- Bregel, Yuri (2003), An Historical Atlas of Central Asia, Brill

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2000), The Age of Achievement: A.D. 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century – Vol. 4, Part II : The Achievements (History of Civilizations of Central Asia), UNESCO Publishing

- Bughra, Imin (1983), The history of East Turkestan, Istanbul: Istanbul publications

- Drompp, Michael Robert (2005), Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire: A Documentary History, Brill

- Haywood, John (1998), Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600–1492, Barnes & Noble

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1964), The Chinese, their history and culture, Volumes 1–2, Macmillan

- Mackerras, Colin (1990), "Chapter 12 – The Uighurs", in Sinor, Denis (ed.), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, pp. 317–342, ISBN 0-521-24304-1

- Millward, James A. (2007), Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press

- Mackerras, Colin, The Uighur Empire: According to the T'ang Dynastic Histories, A Study in Sino-Uighur Relations, 744–840. Publisher: Australian National University Press, 1972. 226 pages, ISBN 0-7081-0457-6

- Golden, Peter B. (2011), Central Asia in World History, Oxford University Press

- Roux, Jean-Paul (2000). Histoire des Turcs (in French). Fayard.

- Sinor, Denis (1969). Inner Asia: History-Civilization-Languages. Indiana University Press.

- Sinor, Denis (1990), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9

- Vovin, A. (2019). "Groping in the Dark: The First Attempt to Interpret the Bugut Brahmi Inscription". Journal Asiatique. 307 (1): 121–134.

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2006), Emperor Yang of the Sui Dynasty: His Life, Times, and Legacy, Albany: State University of New York Press, ISBN 9780791482681.

- Xiong, Victor (2008), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 978-0810860537

- Xue, Zongzheng (薛宗正). (1992). Turkic peoples (突厥史). Beijing: 中国社会科学出版社. ISBN 978-7-5004-0432-3; OCLC 28622013

![Tamga of Ashina tribe.[1] of Göktürk Khaganate](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a3/Tamga_of_Ashina.png/85px-Tamga_of_Ashina.png)

![Gold Mask Inlaid with Rubies, probably belonging to the Turkic Empire of Central Asia. 5th - 6th century CE. Excavated at Boma Tomb in Zhaosu County, Xinjiang. Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture Museum collection.[32]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ee/%E9%95%B6%E5%B5%8C%E7%BA%A2%E5%AE%9D%E7%9F%B3%E9%87%91%E9%9D%A2%E5%85%B7_%E8%A3%81%E5%89%AA.jpg/160px-%E9%95%B6%E5%B5%8C%E7%BA%A2%E5%AE%9D%E7%9F%B3%E9%87%91%E9%9D%A2%E5%85%B7_%E8%A3%81%E5%89%AA.jpg)

![Göktürk petroglyphs from Mongolia (6th to 8th century).[33]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6e/Tyurki.jpg/200px-Tyurki.jpg)