Concentrated animal feeding operation

This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. (January 2021) |

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (April 2020) |

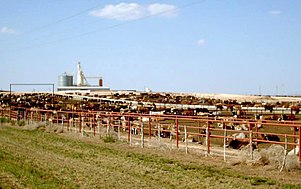

In animal husbandry, a concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO), as defined by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), is an intensive animal feeding operation (AFO) in which over 1000 animal units are confined for over 45 days a year. An animal unit is the equivalent of 1000 pounds of "live" animal weight. A thousand animal units equates to 700 dairy cows, 1000 meat cows, 2500 pigs weighing more than 55 pounds (25 kg)s, 10,000 pigs weighing under 55 pounds, 10,000 sheep, 55,000 turkeys, 125,000 chickens, or 82,000 egg laying hens or pullets.[1]

CAFOs are governed by regulations that restrict how much waste can be distributed and the quality of the waste materials.[1] As of 2016 there were around 212,000 AFOs in the United States,[2]: 1.2 19,496 of which were CAFOs.[3][a]

Livestock production has become increasingly dominated by CAFOs in the United States and other parts of the world.[4] Most poultry was raised in CAFOs starting in the 1950s, and most cattle and pigs by the 1970s and 1980s.[5] By the mid-2000s CAFOs dominated livestock and poultry production in the United States, and the scope of their market share is steadily increasing. In 1966, it took one million farms to house 57 million pigs; by the year 2001, it took only 80,000 farms to house the same number.[6][7]

Definition

There are roughly 212,000 AFOs in the United States,[2]: 1.2 of which 19,496 met the more narrow criteria for CAFOs in 2016.[3] The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has delineated three categories of CAFOs, ordered in terms of capacity: large, medium and small.[8] The relevant animal unit for each category varies depending on species and capacity. For instance, large CAFOs house 1,000 or more cattle, medium CAFOs can have 300–999 cattle, and small CAFOs harbor no more than 300 cattle.[8]

The table below provides some examples of the size thresholds for CAFOs:

| Animal Sector | Large CAFOs | Medium CAFOs | Small CAFOs |

|---|---|---|---|

| cattle or cow/calf pairs | 1,000 or more | 300–999 | less than 300 |

| mature dairy cattle | 700 or more | 200–699 | less than 200 |

| turkeys | 55,000 or more | 16,500–54,999 | less than 16,500 |

| laying hens or broilers (liquid manure handling systems) | 30,000 or more | 9,000–29,999 | less than 9,000 |

| chickens other than laying hens (other than a liquid manure handling systems) | 125,000 or more | 37,500–124,999 | less than 37,500 |

| laying hens (other than a liquid manure handling systems) | 82,000 or more | 25,000–81,999 | less than 25,000 |

The categorization of CAFOs affects whether a facility is subject to regulation under the Clean Water Act (CWA). EPA's 2008 rule specifies that "large CAFOs are automatically subject to EPA regulation; medium CAFOs must also meet one of two 'method of discharge' criteria to be defined as a CAFO (or may be designated as such); and small CAFOs can only be made subject to EPA regulations on a case-by-case basis."[8] A small CAFO will also be designated a CAFO for purposes of the CWA if it discharges pollutants into waterways of the United States through a man-made conveyance such as a road, ditch or pipe. Alternatively, a small CAFO may be designated an ordinary animal feeding operation (AFO) once its animal waste management system is certified at the site.

Since it first coined the term, the EPA has changed the definition (and applicable regulations) for CAFOs on several occasions. Private groups and individuals use the term CAFO colloquially to mean many types of both regulated and unregulated facilities, both inside and outside the United States. The definition used in everyday speech may thus vary considerably from the statutory definition in the CWA. CAFOs are commonly characterized as having large numbers of animals crowded into a confined space, a situation that results in the concentration of manure in a small area.

Key issues

Environmental impact

The EPA has focused on regulating CAFOs because they generate millions of tons of manure every year. When improperly managed, the manure can pose substantial risks to the environment and public health.[9] In order to manage their waste, CAFO operators have developed agricultural wastewater treatment plans. The most common type of facility used in these plans, the anaerobic lagoon, has significantly contributed to environmental and health problems attributed to the CAFO.[10]

Water quality

The large amounts of animal waste from CAFOs present a risk to water quality and aquatic ecosystems.[11] States with high concentrations of CAFOs experience on average 20 to 30 serious water quality problems per year as a result of manure management issues.[12]

Animal waste includes a number of potentially harmful pollutants. Pollutants associated with CAFO waste principally include:

- nitrogen and phosphorus, collectively known as nutrient pollution;

- organic matter;

- solids, including the manure itself and other elements mixed with it such as spilled feed, bedding and litter materials, hair, feathers and animal corpses;

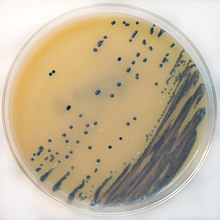

- pathogens (disease-causing organisms such as bacteria and viruses);

- salts;

- trace elements such as arsenic;

- odorous/volatile compounds such as carbon dioxide, methane, hydrogen sulfide, and ammonia;

- antibiotics;

- pesticides and hormones.[12][13]

The two main contributors to water pollution caused by CAFOs are soluble nitrogen compounds and phosphorus. The eutrophication of water bodies from such waste is harmful to wildlife and water quality in aquatic system like streams, lakes, and oceans.[14]

Because groundwater and surface water are closely linked, water pollution from CAFOs can affect both sources if one or the other is contaminated.[12] Surface water may be polluted by CAFO waste through the runoff of nutrients, organics, and pathogens from fields and storage. Waste can be transmitted to groundwater through the leaching of pollutants.[15] Some facility designs, such as lagoons, can reduce the risk of groundwater contamination, but the microbial pathogens from animal waste may still pollute surface and groundwater, causing adverse effects on wildlife and human health.[16]

A CAFO is responsible for one of the biggest environmental spills in U.S. history. In 1995, a 120,000-square-foot (11,000 m2) lagoon ruptured in North Carolina. North Carolina contains a significantly large portion of the United State's industrial hog operations which disproportionally affects Black, Hispanic and Indian American residents.[17] The spill released 25.8 million US gallons (98,000 m3) of effluvium into the New River[18] and resulted in the killing of 10 million fish in local water bodies. The spill also contributed to an outbreak of Pfiesteria piscicida, which caused health problems for humans in the area including skin irritations and short term cognitive problems.[19]

Air quality

CAFOs contribute to the reduction of ambient air quality. CAFOs release several types of gas emissions—ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, methane, and particulate matter—all of which bear varying human health risks. The amount of gas emissions depends largely on the size of the CAFO. The primary cause of gas emissions from CAFOs is the decomposition of animal manure being stored in large quantities.[12] Additionally, CAFOs emit strains of antibiotic resistant bacteria into the surrounding air, particularly downwind from the facility. Levels of antibiotics measured downwind from swine CAFOs were three times higher than those measured upwind.[20] While it is not widely known what is the source of these emissions, the animal feed is suspected.[21]

Globally, ruminant livestock are responsible for about 115 Tg/a of the 330 Tg/a (35%) of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions released per year.[22] Livestock operations are responsible for about 18% of greenhouse gas emissions globally and over 7% of greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S.[23] Methane is the second most concentrated greenhouse gas contributing to global climate change,[24] with livestock contributing nearly 30% of anthropogenic methane emissions.[25] Only 17% of these livestock emissions are due to manure management, with the majority resulting from enteric fermentation, or gases produced during digestion.[25] With regards to antibiotic resistant bacteria, Staphylococcus Aureus accounts for 76% of bacteria grown within a swine CAFO.[20] Group A Streptococci, and Fecal Coliforms were the two next most prevalent bacteria grown within the ambient air inside of swine CAFO.[20]

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) acknowledges the significant effect livestock has on methane emissions, antibiotic resistance, and climate change, and thus, recommends eliminating environmental stressors and modifying feeding strategies, including sources of feed grain, amount of forage, and amount of digestible nutrients as strategies for reducing emissions.[26] The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) advocates for minimizing the use of non-therapeutic antibiotics, especially those that are widely used in human medicine, at the advice of over 350 organizations including the American Medical Association.[27] If no change is made and methane emissions continue increasing in direct proportion to the number of livestock, global methane production is predicted to increase 60% by 2030.[28] Greenhouse gases and climate change affect the air quality with adverse health effects including respiratory disorders, lung tissue damage, and allergies.[29] Reducing the increase of greenhouse gas emissions from livestock could rapidly curb global warming.[30] In addition, people who live near CAFOs frequently complain of the odors, which come from a complex mixture of ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, carbon dioxide, and volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds.

In regard to air quality effects caused by waste disposal, some CAFOs will use "spray fields" and pump the waste of thousands of animals into a machine that sprays it onto an open field. The spray can be carried by wind onto nearby homes, depositing pathogens, heavy metals, and antibiotic resistant bacteria into the air of communities often consisting mostly of low income and/or racial minority families. The odor plume caused by emissions and spraying often pervades nearby communities, contains respiratory and eye irritants including hydrogen sulfide and ammonia.[31]

Economic impact

Increased role in the market

The economic role of CAFOs has expanded significantly in the U.S. in the past few decades, and there is clear evidence that CAFOs have come to dominate animal production industries. The rise in large-scale animal agriculture began in the 1930s with the modern mechanization of swine slaughterhouse operations.[32]

The growth of corporate contracting has also contributed to a transition from a system of many small-scale farms to one of relatively few large industrial-scale farms. This has dramatically changed the animal agricultural sector in the United States. According to the National Agricultural Statistics Service, "In the 1930s, there were close to 7 million farms in the United States and as of the 2002 census, just over 2 million farms remain."[33] From 1969 to 2002, the number of family farms dropped by 39%,[34] yet the percentage of family farms has remained high. As of 2004, 98% of all U.S. farms were family-owned and -operated.[35] Most meat and dairy products are now produced on large farms with single-species buildings or open-air pens.[36]

Due to their increased efficiency, CAFOs provide a source of low cost animal products: meat, milk and eggs. CAFOs may also stimulate local economies through increased employment and use of local materials in their production.[37] The development of modern animal agriculture has increased the efficiency of raising meat and dairy products. Improvements in animal breeding, mechanical innovations, and the introduction of specially formulated feeds (as well as animal pharmaceuticals) have contributed to the decrease in cost of animal products to consumers.[38] The development of new technologies has also helped CAFO owners reduce production cost and increase business profits with less resources consumption. The growth of CAFOs has corresponded with an increase in the consumption of animal products in the United States. According to author Christopher L. Delgado, "milk production has doubled, meat production has tripled, and egg production has increased fourfold since 1960" in the United States.[39]

Along with the noted benefits, there are also criticisms regarding CAFOs' impact on the economy. Many farmers in the United States find that it is difficult to earn a high income due to the low market prices of animal products.[40] Such market factors often lead to low profit margins for production methods and a competitive disadvantage against CAFOs. Alternative animal production methods, like "free range" or "family farming" operations[41] are losing their ability to compete, though they present few of the environmental and health risks associated with CAFOs.

Negative production externalities

Critics have long argued [by whom?] that the "retail prices of industrial meat, dairy, and egg products omit immense impacts on human health, the environment, and other shared public assets." The negative production externalities of CAFOs have been described as including "massive waste amounts with the potential to heat up the atmosphere, foul fisheries, pollute drinking water, spread disease, contaminate soils, and damage recreational areas" that are not reflected in the price of the meat product. Environmentalists contend that "citizens ultimately foot the bill with hundreds of billions of dollars in taxpayer subsidies, medical expenses, insurance premiums, declining property values, and mounting cleanup costs."[4] Some economists agree that CAFOs "operate on an inefficient scale."[42] It has been argued, for instance, that "diminishing returns to scale quickly lead to costs of animal confinement that overwhelm any benefits of CAFOs."[42] These economists claim that CAFOs are at an unfair competitive advantage because they shift the costs of animal waste from CAFOs to the surrounding region (an unaccounted for "externality").

The evidence shows that CAFOs may be contributing to the drop in nearby property values. There are many reasons for the decrease in property values, such as loss of amenities, potential risk of water contamination, odors, air pollution, and other health related issues. One study shows that property values on average decrease by 6.6% within a 3-mile (4.8 km) radius of a CAFO and by 88% within 1/10 of a mile from a CAFO.[43] Proponents of CAFOs, including those in farm industry, respond by arguing that the negative externalities of CAFOs are limited. One executive in the pork industry, for instance, claims that any odor or noise from CAFOs is limited to an area within a quarter-mile of the facility.[44] Proponents also point to the positive effect they believe CAFOs have on the local economy and tax base. CAFOs buy feed from and provide fertilizer to local farmers.[45] And the same executive claims that farmers near CAFOs can save $20 per acre by using waste from CAFOs as a fertilizer.[46]

Environmentalists contend that "sustainable livestock operations" present a "less costly alternative." These operations, it is argued, "address potential health and environmental impacts through their production methods." And though "sustainably produced foods may cost a bit more, many of their potential beneficial environmental and social impacts are already included in the price."[4] In other words, it is argued that if CAFO operators were required to internalize the full costs of production, then some CAFOs might be less efficient than the smaller farms they replace.[47]

Other economic criticisms

Critics of CAFOs also maintain that CAFOs benefit from the availability of industrial and agricultural tax breaks/subsidies and the "vertical integration of giant agribusiness firms."[42] The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), for instance, spent an average of $16 billion annually between FY 1996 to FY 2002 on commodity based subsidies.[48] Some allege that the lax enforcement of anti-competitive practices may be contributing to the formulation of market monopoly. Critics also contend that CAFOs reduce costs and maximize profits through the overuse of antibiotics.[49]

Public health concerns

The direct discharge of manure from CAFOs and the accompanying pollutants (including nutrients, antibiotics, pathogens, and arsenic) is a serious public health risk.[50] The contamination of groundwater with pathogenic organisms from CAFOs can threaten drinking water resources, and the transfer of pathogens through drinking water contamination can lead to widespread outbreaks of illness. The EPA estimates that about 53% of people in the United States rely on groundwater resources for drinking water.[51]

There are numerous effects on human health due to water contaminated by CAFOs. Accidental ingestion of contaminated water can result in diarrhea or other gastrointestinal illnesses and dermal exposure can result in irritation and infection of the skin, eyes or ear.[52] High levels of nitrate also pose a threat to high-risk populations such as young children, pregnant women or the elderly. Several studies have shown that high levels of nitrate in drinking water are associated with increased risk of hyperthyroidism, insulin dependent diabetes and central nervous system malformations.[52]

The exposure to chemical contaminates, such as antibiotics, in drinking water also creates problems for public health.[11] In order to maximize animal production, CAFOs have used an increasing number of antibiotics, which in turn, increases bacterial resistance. This resistance threatens the efficiency of medical treatment for humans fighting bacterial infections. Contaminated surface and groundwater is especially concerning, due to its role as a pathway for the dissemination of antibiotic resistant bacteria.[53] Due to the various antibiotics and pharmaceutical drugs found at a high density in contaminated water, antibiotic resistance can result due to DNA mutations, transformations and conjugations.[53]

Antibiotics are used heavily in CAFOs to both treat and prevent illness in individual animals as well as groups. The close quarters inside CAFOs promote the sharing of pathogens between animals and thus, the rapid spread of disease. Even if their stock are not sick, CAFOs will incorporate low doses of antibiotics into feed “to reduce the chance for infection and to eliminate the need for animals to expend energy fighting off bacteria, with the assumption that saved energy will be translated into growth”.[37] This practice is an example of a non-therapeutic use of antibiotics. Such antibiotic use is thought to allow animals to grow faster and bigger, consequently maximizing production for that CAFO. Regardless, the World Health Organization has recommended that the non-therapeutic use of antibiotics in animal husbandry be reevaluated, as it contributes to the overuse of antibiotics and thus the emergence of resistant bacteria that can spread to humans.[54][55][56] When bacteria naturally occurring in the animals’ environment and/or body are exposed to antibiotics, natural selection results in bacteria, who have genetic variations that protect them from the drugs, to survive and spread their advantageously resistant traits to other bacteria present in the ecosystem.[57] This is how the problem of antimicrobial resistance increases with the continued use of antibiotics by CAFOs. This is of concern to public health because resistant bacteria generated by CAFOs can be spread to the surrounding environment and communities via waste water discharge or aerosolization of particles.[58]

Consequences of the air pollution caused by CAFO emissions include asthma, headaches, respiratory problems, eye irritation, nausea, weakness, and chest tightness. These health effects are felt by farm workers and nearby residents, including children.[59] The risks to nearby residents was highlighted in a study evaluating health outcomes of more than 100,000 individuals living in regions with high densities of CAFOs, finding a higher prevalence of pneumonia and unspecified infectious diseases in those with high exposures compared to controls.[60] Furthermore, a Dutch cross-sectional study 2,308 adults found decreases in residents' lung function to be correlated with increases particle emissions by nearby farms.[61] In regards to workers, multiple respiratory consequences should be noted. Although "in many big CAFOs, it takes only a few workers to run a facility housing thousands of animals,"[62] the long exposure and close contact to animals puts CAFO employees at an increased risk. This includes a risk of contracting diseases like Novel H1N1 flu, which erupted globally in spring of 2009,[63] or MRSA, a strain of antibiotic resistant bacteria.[55] For instance, livestock-associated MRSA has been found in the nasal passages of CAFO workers, on the walls of the facilities they work in, and in the animals they tend.[55] In addition, individuals working in CAFOs are at risk for chronic airway inflammatory diseases secondary to dust exposure, with studies suggesting the possible benefits to utilizing inhaler treatments empirically.[64] Studies conducted by the University of Iowa show that the asthma rate of children of CAFO operators is higher than that of children from other farms.[65]

Negative effects on minority populations

Low income and minority populations suffer disproportionately from proximity to CAFO and pollution and waste.[31] These populations suffer the most due to their lack of political clout to oppose construction of CAFOs and are often not economically capable of simply moving somewhere else.

In southern United States, the "Black Belt", a roughly crescent-shaped geological formation of dark fertile soil in the Southern United States well suited to cotton farming, has seen the long-lasting effects of slavery. During and after the Civil War, this area consisted mostly of black people who worked as sharecroppers and tenant farmers. Due to ongoing discrimination in land sales and lending, many African American farmers were systematically deprived of farmland. Today, communities in the Black Belt experience poverty, poor housing, unemployment, poor health care and have little political power when it comes to the building of CAFOs. Black and brown people living near CAFOs often lack the resources to leave compromised areas and are further trapped by plummeting property values and poor quality of life.[66] In addition to financial problems, CAFOs are also protected by "right-to-farm" law that protects them from residents that are living in CAFO occupied communities.[67]

Not only are communities surrounded negatively affected by CAFOs, but the workers themselves experience harm from being on the job. In a study done in North Carolina that focused on twenty one Latino chicken catchers for a poultry-processing plant, the work place was found to be forcefully high intensity labor with high potential for injury and illness including trauma, respiratory illness, drug use and musculoskeletal injuries. Workers were also found to have little training about the job or safety.[68] In the United States, agricultural workers are engaged in one of the most hazardous jobs in the country.[69]

CAFO workers have historically been African American but there has been a surge of Hispanic and often undocumented Hispanic workers. Between 1980 and 2000, there was a clear shift in an ethnic and racially diverse workforce, led by Hispanic workforce growth.[7] Oftentimes, CAFO owners will preferably hire Hispanic workers because they are low-skilled workers who are willing to work longer hours and do more intensive work. Due to this, there are increased ICE raids on meat processing plants.

Animal health and welfare concerns

CAFO practices have raised concerns over animal welfare from an ethics standpoint. Some view such conditions as neglectful to basic animal welfare. Many people believe that the harm to animals before their slaughter should be addressed through public policy.[70] Laws regarding animal welfare in CAFOs have already been passed in the United States. For instance, in 2002, the state of Florida passed an amendment to the state's constitution banning the confinement of pregnant pigs in gestation crates.[71] As a source for comparison, the use of battery cages for egg-laying hens and battery cage breeding methods have been completely outlawed in the European Union since 2012.[72]

Whereas some people are concerned with animal welfare as an end in itself, others are concerned about animal welfare because of the effect of living conditions on consumer safety. Animals in CAFOs have lives that do not resemble those of animals found in the wild.[73] Although CAFOs help secure a reliable supply of animal products, the quality of the goods produced is debated, with many arguing that the food produced is unnatural. For instance, confining animals into small areas requires the use of large quantities of antibiotics to prevent the spread of disease. There are debates over whether the use of antibiotics in meat production is harmful to humans.[74]

We have discussed that milk production is a metric of a cows health. Since 1960 average milk cow production has increased from 5-kilogram /day (11 lb) to 30-kilogram /day (66 lb) by 2008, as noted by Dale Bauman and Jude Capper in the Efficiency of Dairy Production and its Carbon Footprint. The article points to the fact that the carbon footprint resulting the production of a gallon of milk is in 2007 is 37% of what it was in 1944.[75] This is largely due to the efficiencies found in larger farming operations and a further understanding of the health needs of farm animals.

Regulation under the Clean Water Act

Basic structure of CAFO regulations under the CWA

The command-and-control permitting structure of the Clean Water Act (CWA) provides the basis for nearly all regulation of CAFOs in the United States. Generally speaking, the CWA prohibits the discharge of pollution to the "waters of the United States" from any "point source", unless the discharge is authorized by a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit issued by the EPA (or a state delegated by the EPA). CAFOs are explicitly listed as a point source in the CWA.[76] Unauthorized discharges made from CAFOs (and other point sources) violate the CWA, even if the discharges are "unplanned or accidental."[77] CAFOs that do not apply for NPDES permits "operate at their own risk because any discharge from an unpermitted CAFO (other than agricultural stormwater) is a violation of the CWA subject to enforcement action, including third party citizen suits."[78]

The benefit of an NPDES permit is that it provides some level of certainty to CAFO owners and operators. "Compliance with the permit is deemed compliance with the CWA... and thus acts as a shield against EPA or State CWA enforcement or against citizen suits under... the CWA."[78] In addition, the "upset and bypass" provisions of the permit can give permitted CAFO owners a legal defense when "emergencies or natural disasters cause discharges beyond their reasonable control."[78]

Under the CWA, the EPA specifies the maximum allowable amounts of pollution that can be discharged by facilities within an industrial category (like CAFOs). These general "effluent limitations guidelines" (ELG) then dictate the terms of the specific effluent limitations found in individual NPDES permits. The limits are based on the performance of specific technologies, but the EPA does not generally require the industry to use these technologies. Rather, the industry may use "any effective alternatives to meet the pollutant limits."[79]

The EPA places minimum ELG requirements into each permit issued for CAFOs. The requirements can include both numeric discharge limits (the amount of a pollutant that can be released into waters of the United States) and other requirements related to ELGs (such as management practices, including technology standards).[80]

History of regulations

The major CAFO regulatory developments occurred in the 1970s and in the 2000s. The EPA first promulgated ELGs for CAFOs in 1976.[77] The 2003 rule issued by the EPA updated and modified the applicable ELGs for CAFOs, among other things. In 2005, the court decision in Waterkeeper Alliance v. EPA (see below) struck down parts of the 2003 rule. The EPA responded by issuing a revised rule in 2008.

A complete history of EPA's CAFO rulemaking activities is provided on the CAFO Rule History page.[81]

Background laws

The Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948 was one of the first major efforts of the U.S. federal government to establish a comprehensive program for mitigating pollution in public water ways. The writers of the act aimed to improve water quality for the circulation of aquatic life, industry use, and recreation. Since 1948, the Act has been amended many times to expand programming, procedures, and standards.[82]

President Richard Nixon’s executive order, Reorganization Plan No. 3, created the EPA in 1970. The creation of the EPA was an effort to create a more comprehensive approach to pollution management. As noted in the order, a single polluter may simultaneously degrade a local environment’s air, water, and land. President Nixon noted that a single government entity should be monitoring and mitigating pollution and considering all effects. As relevant to CAFO regulation, the EPA became the main federal authority on CAFO pollution monitoring and mitigation.[83]

Congress passed the CWA in 1972 when it reworked the Federal Water Pollution Control Amendments.[84] It specifically defines CAFOs as point source polluters and required operations managers and/or owners to obtain NPDES permits in order to legally discharge wastewater from its facilities.[85]

Initial regulations (1970s)

The EPA began regulating water pollution discharges from CAFOs following passage of the 1972 CWA. ELGs for feedlot operations were promulgated in 1974, placing emphasis on best available technology in the industry at the time.[86][failed verification] In 1976 EPA began requiring all CAFOs to be first defined as AFOs. From that point, if the specific AFO met the appropriate criteria, it would then be classified as a CAFO and subject to appropriate regulation. That same year, EPA defined livestock and poultry CAFO facilities and established a specialized permitting program.[87] NPDES permit procedures for CAFOs were also promulgated in 1976.[88]

Prior to 1976, size had been the main defining criteria of CAFOs. However, after the 1976 regulations came into effect, the EPA stipulated some exceptions. Operations that were identified as particularly harmful to federal waterways could be classified as CAFOs, even if the facilities’ sizes fall under AFOs standards. Additionally, some CAFOs were not required to apply for wastewater discharge permits if they met the two major operational-based exemptions. The first exception applied to operations that discharge wastewater only during a 25-year, 24-hour storm event. (The operation only discharges during a 24-hour rainfall period that occurs once every 25 years or more on average.) The second exception was when operations apply animal waste onto agricultural land.[87]

Developments in the 1990s

In 1989, the Natural Resources Defense Council and Public Citizen filed a lawsuit against the EPA (and Administrator of the EPA, William Reilly). The plaintiffs claimed the EPA had not complied with the CWA with respect to CAFOs.[87] The lawsuit, Natural Resources Defense Council v. Reilly (D.D.C. 1991), resulted in a court order mandating the EPA update its regulations. They did so in what would become the 2003 Final Rule.[89]

In 1995, the EPA released a "Guide Manual on NPDES Regulations for Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations" to provide more clarity to the public on NPDES regulation after the EPA's report "Feedlots Case Studies of Selected States" revealed there was uncertainty in the public regarding CAFO regulatory terminology and criteria.[85] Although the document is not a rule, it did offer insight and furthered public understanding of previous rules.

In his 1998 Clean Water Action Plan, President Bill Clinton directed the USDA and the EPA to join forces to develop a framework for future actions to improve national water quality standards for public health. The two federal agencies’ specific responsibility was to improve the management of animal waste runoff from agricultural activities. In 1998, the USDA and the EPA hosted eleven public meetings across the country to discuss animal feeding operations (AFOs).[90]

On March 9, 1999 the agencies released the framework titled the Unified National Strategy for Animal Feeding Operations.[91] In the framework, the agencies recommended six major activities to be included in operations’ Comprehensive Nutrient Management Plans (CNMPs):

- feed management

- manure handling and storage

- land application of manure

- land management

- record keeping

- activities that utilize manure.[92]

The framework also outlined two types of related programs. First, “voluntary programs” were designed to assist AFO operators with addressing public health and water quality problems.[92] The framework outlines three types of voluntary programs available: “locally led conservation,” “environmental education,” and “financial and technical assistance.”[92] The framework explained that those that participate in voluntary programs are not required to have a comprehensive nutrient management plan (CNMP). The second type of program outlined by the framework was regulatory, which includes command-and-control regulation with NPDES permitting.[92]

EPA final rule (2003)

EPA's 2003 rule updated decades-old policies to reflect new technology advancements and increase the expected pollution mitigation from CAFOs.[93] The EPA was also responding to a 1991 court order based on the district court's decision in Natural Resources Defense Council v. Reilly.[87] The final rule took effect on April 14, 2003 and responded to public comments received following the issuance of the proposed rule in 2000.[94] The EPA allowed authorized NPDES states until February 2005 to update their programs and develop technical standards.[94]

The 2003 rule established "non-numerical best management practices" (BMPs) for CAFOs that apply both to the "production areas" (e.g. the animal confinement area and the manure storage area) and, for the first time ever, to the "land application area" (land to which manure and other animal waste is applied as fertilizer).[95][96] The standards for BMPs in the 2003 rule vary depending on the regulated area of the CAFO:

- Production Area: Discharges from a production area must meet a performance standard that requires CAFOs to "maintain waste containment structures that generally prohibit discharges except in the event of overflows or runoff resulting from a 25-year, 24-hour rainfall event."[96] New sources are required to meet a standard of "no discharge" except in the event of a 100-year, 24-hour rainfall event.[79]

- Land Application Area: The BMPs for land application areas include different requirements, such as vegetative buffer strips and setback limits from water bodies.[96]

The 2003 rule also requires CAFOs to submit an annual performance report to the EPA and to develop and implement a comprehensive nutrient management plan (NMP) for handling animal waste.[96] Lastly, in an attempt to broaden the scope of regulated facilities, the 2003 rule expanded the number of CAFOs required to apply for NPDES permits by making it mandatory for all CAFOs (not just those who actually discharge pollutants into waters of the United States).[96] Many of the provisions of the rule were affected by the Second Circuit's decision issued in Waterkeeper Alliance v. EPA.

Waterkeeper Alliance v. EPA (2nd Cir. 2005)

Environmental and farm industry groups challenged the 2003 final rule in court, and the Second Circuit Court of Appeals issued a decision in the consolidated case Waterkeeper Alliance, Inc. v. EPA, 399 F.3d 486 (2nd Cir. 2005). The Second Circuit's decision reflected a "partial victory" for both environmentalists and industry, as all parties were "unsatisfied to at least some extent" with the court's decision.[97] The court's decision addressed four main issues with the 2003 final rule promulgated by the EPA:

- Agricultural Stormwater Discharges: The EPA's authority to regulate CAFO waste that results in agricultural stormwater discharge was one of the "most controversial" aspects of the 2003 rule.[98] The issue centered on the scope of the Clean Water Act (CWA), which provides for the regulation only of "point sources." The term was defined by the CWA to expressly include CAFOs but exclude "agricultural stormwater."[99] The EPA was thus forced to interpret the statutory definition to "identify the conditions under which discharges from the land application area of [waste from] a CAFO are point source discharges that are subject to NPDES permitting requirements, and those which are agricultural stormwater discharges and thus are not point source discharges."[98] In the face of widely divergent views of environmentalists and industry groups, the EPA in the 2003 rule determined that any runoff resulting from manure applied in accordance with agronomic rates would be exempt from the CWA permitting requirements (as "agricultural stormwater"). However, when such agronomic rates are not used, the EPA concluded that the resulting runoff from a land application is not "agricultural stormwater" and is therefore subject to the CWA (as a discharge from a point source, i.e. the CAFO). The Second Circuit upheld the EPA's definition as a "reasonable" interpretation of the statutory language in the CWA.

- Duty to Apply for an NPDES Permit: The 2003 EPA rule imposed a duty on all CAFOs to apply for an NPDES permit (or demonstrate that they had no potential to discharge).[100] The rationale for this requirement was the EPA's "presumption that most CAFOs have a potential to discharge pollutants into waters of the United States" and therefore must affirmatively comply with the requirements of the Clean Water Act.[101] The Second Circuit sided with the farm industry plaintiffs on this point and ruled that this portion of the 2003 rule exceeded the EPA's authority. The court held that the EPA can require NPDES permits only where there is an actual discharge by a CAFO, not just a potential to discharge. The EPA later estimated that 25 percent fewer CAFOs would seek permits as a result of the Second Circuit's decision on this issue.[102]

- Nutrient Management Plans (NMPs): The fight in court over the portion of the 2003 rule on NMPs was a proxy for a larger battle over public participation by environmental groups in the implementation of the CWA. The 2003 rule required all permitted CAFOs that "land apply" animal waste to develop an NMP that satisfied certain minimum requirements (e.g. ensuring proper storage of manure and process wastewater). A copy of the NMP was to be kept on-site at the facility, available for viewing by the EPA or other permitting authority. The environmental plaintiffs argued that this portion of the rule violated the CWA and the Administrative Procedure Act by failing to make the NMP part of the NPDES permit itself (which would make the NMP subject to both public comments and enforcement in court by private citizens). The court sided with the environmental plaintiffs and vacated this portion of the rule.[103]

- Effluent Limitation Guidelines (ELGs) for CAFOs: The 2003 rule issued New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) for new sources of swine, poultry, and veal operations. The CWA requires that NSPS be based on what is called the "best available demonstrated control technology."[104] The EPA's 2003 rule required that these new sources meet a "no discharge" standard, except in the case of a 100-year, 24-hour rainfall event (or a less restrictive measure for new CAFOs that voluntarily use new technologies and management practices). The Second Circuit ruled that the EPA did not provide an adequate basis (either in the statute or in evidence) for this portion of the rule.[79] The Second Circuit also required the EPA to go back and provide additional justification for the requirements in the 2003 rule dealing with the "best control technology for conventional pollutants" (BCT) standards for reducing fecal coliform pathogen. Lastly, the court ordered the EPA to provide additional analysis on whether the more stringent "water quality-based effluent permit limitations" (WQBELs) should be required in certain instances for CAFO discharges from land application areas, a policy that the EPA had rejected in the 2003 rule.

EPA final rule (2008)

The EPA published revised regulations that address the Second Circuit court's decision in Waterkeeper Alliance, Inc. v. EPA on November 20, 2008 (effective December 22, 2008).[105] The 2008 final rule revised and amended the 2003 final rule.

The 2008 rule addresses each point of the court's decision in Waterkeeper Alliance v. EPA. Specifically, the EPA adopted the following measures:

- The EPA replaced the "duty to apply" standard with one that requires NPDES permit coverage for any CAFO that "discharges or proposes to discharge." The 2008 rule specifies that "a CAFO proposes to discharge if it is designed, constructed, operated, or maintained such that a discharge will occur."[106] On May 28, 2010, the EPA issued guidance "designed to assist permitting authorities in implementing the [CAFO regulations] by specifying the kinds of operations and factual circumstances that EPA anticipates may trigger the duty to apply for permits.”[107] On March 15, 2011, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in National Pork Producers Council v. EPA again struck down the EPA's rule on this issue, holding that the "propose to discharge" standard exceeds the EPA's authority under the CWA. After the Fifth Circuit's ruling, a CAFO cannot be required to apply for an NPDES permit unless it actually discharges into a water of the United States.[108]

- The EPA modified the requirements related to the nutrient management plans (NMP). In keeping with the court's decision in Waterkeeper Alliance v. EPA, the EPA instituted a requirement that the permitting authority (either the EPA or the State) incorporate the enforceable "terms of the NMP" into the actual permit. The "terms of the NMP" include the "information, protocols, best management practices (BMPs) and other conditions in the NMP necessary to meet the NMP requirements of the 2003 rule."[78] The EPA must make the NMPs in the applications filed by CAFOs publicly available.

- The EPA reiterated that in order to take advantage of the "agricultural stormwater" exception (upheld by the court in Waterkeeper Alliance v. EPA) an unpermitted CAFO must still implement "site-specific nutrient management practices that ensure appropriate agricultural utilization of the nutrients as specified previously under the 2003 rule."[78] The unpermitted facility must keep documentation of such practices and make it available to the permitting authority in the case of a precipitation-related discharge.[78]

- The EPA addressed the Second Circuit's ruling on the effluent limitation guidelines (ELGs) for CAFOs. The agency deleted the provision allowing new sources of CAFOs to meet a 100-year, 24-hour precipitation-event standard, replacing it with a "no discharge" standard through the establishment of best management practices.[78] The EPA also clarified and defended its previous positions on (1) the availability of water quality-based effluent limitations (WQBELs) and (2) the appropriateness of the best control technology (BCT) standards for fecal coliform. First, the 2008 rule "explicitly recognizes" that the permitting authority may impose WQBELs on all production area discharges and all land application discharges (other than those that meet the "agricultural stormwater" exemption) if the technology-based effluent limitations are deemed insufficient to meet the water quality standards of a particular body of water. In particular, the EPA noted that a case-by-case review should be adopted in cases where CAFOs discharge to the waters of the United States through a direct hydrologic connection to groundwater.[78] Second, the EPA announced that it would not be promulgating more stringent standards for fecal coliform than in the 2003 rule because it reached the conclusion there is "no available, achievable, and cost reasonable technology on which to base such limitations."[78]

The 2008 final rule also specifies two approaches that a CAFO may use to identify the "annual maximum rates of application of manure, litter, and process wastewater by field and crop for each year of permit coverage." The linear approach expresses the rate in terms of the "amount of nitrogen and phosphorus from manure, litter, and process wastewater allowed to be applied." The narrative rate approach expresses the amount in terms of a "narrative rate prescribing how to calculate the amount of manure, litter, and process wastewater allowed to be applied.[78] The EPA believes that the narrative approach gives CAFO operators the most flexibility. Normally, CAFO operators are subject to the terms of their permit for a period of 5 years. Under the narrative approach, CAFO operators can use "real time" data to determine the rates of application. As a result, CAFO operators can more easily "change their crop rotation, form and source of manure, litter, and process wastewater, as well as the timing and method of application" without having to seek a revision to the terms of their NPDES permits.[78]

Government assistance for compliance

The EPA points to several tools available to assist CAFO operators in meeting their obligations under the CWA. First, the EPA awards federal grants to provide technical assistance to livestock operators for preventing discharges of water pollution (and reducing air pollution). The EPA claims that CAFOs can obtain an NMP for free under these grants.[109] Recently, the annual amount of the grant totaled $8 million.[78] Second, a Manure Management Planner (MMP) software program has been developed by Purdue University in conjunction with funding by a federal grant. The MMP is tailored to each state's technical standards (including Phosphorus Indexes and other assessment tools).[78] The MMP program provides free assistance to both permitting authorities and CAFO operators and can be found at the Purdue University website.[110] Lastly, the EPA notes that the USDA offers a "range of support services," including a long-term program that aims to assist CAFOs with NMPs.[78]

Debate over EPA policy

Environmentalists argue that the standards under the CWA are not strong enough. Researchers have identified regions in the country that have weak enforcement of regulations and, therefore, are popular locations for CAFO developers looking to reduce cost and expand operations without strict government oversight.[111] Even when laws are enforced, there is the risk of environmental accidents. The massive 1995 manure spill in North Carolina highlights the reality that contamination can happen even when it is not done maliciously.[112] The question of whether such a spill could have been avoided is a contributing factor in the debate for policy reform.

Environmental groups have criticized the EPA's regulation of CAFOs on several specific grounds, including the following.[113]

- Size threshold for "CAFO": Environmentalists favor reducing the size limits required to qualify as a CAFO; this would broaden the scope of the EPA's regulations on CAFOs to include more industry farming operations (currently classified as AFOs).

- Duty to apply: Environmentalists strongly criticized the portion of the Court's ruling in Waterkeeper Alliance that deleted the EPA's 2003 rule that all CAFOs must apply for an NPDES permit. The EPA's revised permitted policy is now overly reactive, environmentalists maintain, because it "allow[s] CAFO operators to decide whether their situation poses enough risk of getting caught having a discharge to warrant the investment of time and resources in obtaining a permit."[114] It is argued that CAFOs have very little incentive to seek an NPDES permit under the new rule.[115]

- Requirement for co-permitting entities that exercise "substantial operational control" over CAFOs: Environmental groups unsuccessfully petitioned the EPA to require "co-permitting of both the farmer who raises the livestock and the large companies that actually own the animals and contract with farmers."[113] This modification to EPA regulations would have made the corporations legally responsible for the waste produced on the farms with which they contract.

- Zero discharge requirement to groundwater when a direct hydrologic connection exists to surface water: The EPA omitted a provision in its 2003 rule that would have held CAFOs to a zero discharge limit from the CAFO's production area to "ground water that has a direct hydrologic connection to surface water."[116] Environmentalists criticized the EPA's decision to omit this provision on the basis that ground water is often a drinking source in rural areas, where most all CAFOs are located.

- Specific performance standards: Environmentalists urged the EPA to phase out the use of lagoons (holding animal waste in pond-like structures) and sprayfields (spraying waste onto crops). Environmentalists argued that these techniques for dealing with animal waste were outmoded and present an "unacceptable risk to public health and the environment" due to their ability to pollute both surface and groundwater following "weather events, human error, and system failures."[116] Environmentalists suggested that whenever manure is land applied that it should be injected into the soil (and not sprayed).

- Lack of regulation of air pollution: The revisions to the EPA's rules under the CWA did not address air pollutants. Environmentalists maintain that the air pollutants from CAFOs—which include ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, methane, volatile organic compounds, and particulate matter—should be subject to EPA regulation.[117]

Conversely, industry groups criticize the EPA's rules as overly stringent. Industry groups vocally opposed the requirement in the 2008 rule (since struck down by the Fifth Circuit) that required CAFOs to seek a permit if they "propose to discharge" into waters of the United States.[118] Generally speaking, the farm industry disputes the presumption that CAFOs do discharge pollutants and it therefore objects to the pressure that the EPA places on CAFOs to voluntarily seek an NPDES permit.[118] As a starting point, farm industry groups "emphasize that most farmers are diligent stewards of the environment, since they depend on natural resources of the land, water, and air for their livelihoods and they, too, directly experience adverse impacts on water and air quality."[119] Some of the agricultural industry groups continue to maintain that the EPA should have no authority to regulate any of the runoff from land application areas because they believe this constitutes a nonpoint source that is outside the scope of the CWA.[113] According to this viewpoint, voluntary programs adequately address any problems with excess manure.[113]

States' role and authority

The role of the federal government in environmental issues is generally to set national guidelines and the state governments’ role is to address specific issues. The framework of federal goals is as such that the responsibility to prevent, reduce, and eliminate pollution are the responsibility of the states.[120]

The management of water and air standards follows this authoritative structure. States that have been authorized by the EPA to directly issue permits under NPDES (also known as "NPDES states"[121]) have received jurisdiction over CAFOs. As a result of this delegation of authority from the EPA, CAFO permitting procedures and standards may vary from state to state.

Specifically for water pollution, the federal government establishes federal standards for wastewater discharge and authorized states develop their own wastewater policies to fall in compliance. More specifically, what a state allows an individual CAFO to discharge must be as strict or stricter than the federal government's standard.[122] This protection includes all waterways, whether or not the water body can safely sustain aquatic life or house public recreational activities. Higher standards are upheld in some cases of pristine publicly owned waterways, such as parks. They keep higher standards in order to maintain the pristine nature of the environment for preservation and recreation. Exceptions are in place for lower water quality standards in certain waterways if it is deemed economically significant.[120] These policy patterns are significant when considering the role of state governments’ in CAFO permitting.

State versus federal permit issuance

Federal law requires CAFOs to obtain NPDES permits before wastewater may be discharged from the facility. The state agency responsible for approving permits for CAFOs in a given state is dependent on the authorization of that state. The permitting process is divided into two main methods based on a state's authorization status. As of 2018, EPA has authorized 47 states to issue NPDES permits. Although they have their own state-specific permitting standards, permitting requirements in authorized states must be at least as stringent as the federal standards.[85]: 13 In the remaining states and territories, an EPA regional office issues NPDES permits.[121]

Permitting process

A state's authority and the state's environmental regulatory framework will determine the permit process and the state offices involved. Below are two examples of states’ permitting organization.

Authorized state case study: Arizona

Arizona issues permits through a general permitting process. CAFOs must obtain both a general Arizona Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (AZPDES) Permit and a general Aquifer Protection Permit.[123] The Arizona state agency tasked with managing permitting is the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ).

For the Aquifer Protection Permit, CAFOs are automatically permitted if they comply with the state's BMP outlined in the relevant state rule, listed on the ADEQ's website. Their compliance is evaluated through agency CAFO Inspection Program's onsite inspections. If a facility is found to be unlawfully discharging, then the agency may issue warnings and, if necessary, file suit against the facility. For the AZPDES permit, CAFOs are required to submit a Notice of Intent to the ADEQ. In addition, they must complete and submit a Nutrient Management Plan (NMP) for the state's annual report.[123]

Even in an authorized state, the EPA maintains oversight of state permitting programs. This would be most likely to happen in the event that a complaint is filed with the EPA by a third party. For instance, in 2008, Illinois Citizens for Clean Air & Water filed a complaint with the EPA arguing that the state was not properly implementing its CAFO permitting program. The EPA responded with an "informal" investigation. In a report released in 2010, the agency sided with the environmental organization and provided a list of recommendations and required action for the state to meet.

Unauthorized state case study: Massachusetts

In unauthorized states, the EPA has the authority for issuing NPDES permits. In these states, such as Massachusetts, CAFOs communicate and file required documentation through an EPA regional office. In Massachusetts, the EPA issues a general permit for the entire state. The state's Department of Agricultural Resources (MDAR) has an agreement with the EPA for the implementation of CAFO rules. MDAR's major responsibility is educational. The agency assists operators in determining if their facility qualifies as a CAFO. Specifically they do onsite evaluations of facilities, provide advice on best practices, and provide information and technical assistance.[124]

If a state has additional state specific rules for water quality standards, the state government maintains the authority for permitting. For instance, New Mexico, also unauthorized, requires CAFOs and AFOs to obtain a Groundwater Permit if the facilities discharge waste in a manner that might affect local groundwater. The EPA is not involved in the issuing of this state permit.[124] Massachusetts, however, does not have additional state permit requirements.[124]

Zoning ordinances

State planning laws and local zoning ordinances represent the main policy tools for regulating land use. Many states have passed legislation that specifically exempt CAFOs (and other agricultural entities) from zoning regulations.[125] The promulgation of so-called "right to farm" statutes have provided, in some instances, a shield from liability for CAFOs (and other potential nuisances in agricultural).[125] More specifically, the right-to-farm statutes seek to "limit the circumstances under which agricultural operations can be deemed nuisances."

The history of these agricultural exemptions dates back to the 1950s. Right-to-farm statutes expanded in the 1970s when state legislatures became increasingly sensitive to the loss of rural farmland to urban expansion.[126] The statutes were enacted at a time when CAFOs and "modern confinement operations did not factor into legislator's perceptions of the beneficiaries of [the] generosity" of such statutes.[125] Forty-three (43) states now have some sort of statutory protection for farmers from nuisance. Some of these states (such as Iowa, Oklahoma, Wyoming, Tennessee, and Kansas) also provide specific protection to animal feeding operations (AFOs) and CAFOs.[126] Right-to-farm statutes vary in form. Some states, for instance, require agricultural operation be located "within an acknowledged and approved agricultural district" in order to receive protection; other states do not.[126]

Opponents of CAFOs have challenged right-to-farm statutes in court, and the constitutionality of such statutes is not entirely clear. The Iowa Supreme Court, for instance, struck down a right-to-farm statute as a "taking" (in violation of the 5th and 14th Amendments of the U.S. Constitution) because the statute stripped neighboring landowners of property rights without compensation.[127]

Regulation under the Clean Air Act

CAFOs are potentially subject to regulation under the Clean Air Act (CAA), but the emissions from CAFOs generally do not exceed established statutory thresholds.[128] In addition, the EPA's regulations do not provide a clear methodology for measuring emissions from CAFOs, which has "vexed both regulators and the industry."[129] Negotiations between the EPA and the agricultural industry did, however, result in an Air Compliance Agreement in January 2005.[128] According to the agreement, certain animal feeding operations (AFOs) received a covenant not to sue from the EPA in exchange for payment of a civil penalty for past violations of the CAA and an agreement to allow their facilities to be monitored for a study on air pollution emissions in the agricultural sector.[128] Results and analysis of the EPA's study are scheduled to be released later in 2011.[128]

Environmental groups have formally proposed to tighten EPA regulation of air pollution from CAFOs. A coalition of environmental groups petitioned the EPA on April 6, 2011 to designate ammonia as a "criteria pollutant" and establish National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for ammonia from CAFOs.[128] The petition alleges that "CAFOs are leading contributors to the nation’s ammonia inventory; by one EPA estimate livestock account for approximately 80 percent of total emissions. CAFOs also emit a disproportionately large share of the ammonia in certain states and communities.”[130] If the EPA adopts the petition, CAFOs and other sources of ammonia would be subject to the permitting requirements of the CAA.

See also

Notelist

- ^ "Today, there are slightly more than one million farms with livestock in the United States. EPA estimates that about 212,000 of those farms are likely to be AFOs—operations where animals are kept and raised in confinement. Although the number of AFOs has declined since 2003, the total number of animals housed at AFOs has continued to grow because of expansion and consolidation in the industry. As Figure 1-1 shows, EPA’s NPDES CAFO program tracking indicates that 20,000 of those AFOs are CAFOs—AFOs that meet certain numeric thresholds or other criteria ..."[2]: 1.2

References

- ^ a b "Animal Feeding Operations". Livestock. Washington, D.C.: United States Natural Resources Conservation Service. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- ^ a b c NPDES Permit Writers' Manual for Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). February 2012. EPA 833-F-12-001.

- ^ a b NPDES CAFO Permitting Status Report—National Summary (Report). EPA. 2016-12-31.

- ^ a b c Imhoff, Daniel; Tompkins, Douglas; Carra, Roberto (2010). CAFO: The Tragedy of Industrial Animal Factories. Devon, UK: Earth Aware Editions/NHBS. ISBN 9781601090584.

- ^ Burkholder, J.; Libra, B.; Weyer, P.; Heathcote, S.; Kolpin, D.; Thorne, P. S.; Wichman, M. (2006). "Impacts of Waste from Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations on Water Quality". Environmental Health Perspectives. 115 (2): 308–312. doi:10.1289/ehp.8839. PMC 1817674. PMID 17384784.

- ^ Walker, Polly; et al. (2005). "Public health implications of meat production and consumption" (PDF). Public Health Nutrition. 8 (4): 348–356. doi:10.1079/phn2005727. PMID 15975179.

- ^ MacDonald, James and McBride, William (January 2009). "The transformation of U.S. livestock agriculture: Scale, efficiency, and risks", Economic Information Bulletin, No. EIB-43, United States Department of Agriculture.

- ^ a b c R:\Public\...\sector_table.wp [PFP#1221434595]

- ^ Waterkeeper Alliance, Inc. et al, v. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 399 F. 3d 486 (2d Cir. 2005-02-28 (amended 2005-03-16; 2005-04-18)).

- ^ "Pollution from Giant Livestock Farms Threatens Public Health". Issue Areas: Water. New York, NY: Natural Resources Defense Council. Archived from the original on 2011-10-11.

- ^ a b Burkholder, J; Libra, B; Weyer, P; Heathcote, S; Kolpin, D; Thorne, PS; Wichman, M (2007). "Impacts of waste from concentrated animal feeding operations on water quality". Environ. Health Perspect. 115 (2): 308–12. doi:10.1289/ehp.8839. PMC 1817674. PMID 17384784.

- ^ a b c d Hribar, Carrie (2010). Shultz, Mark (ed.). Understanding Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations and Their Impact on Communities (PDF) (Report). Bowling Green, OH: National Association of Local Boards of Health.

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). "National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System Permit Regulation and Effluent Limitations Guidelines and Standards for Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations." Federal Register, 66 FR 2976-79 2960, 2976-79 (proposed Jan. 12, 2001). See also: Preamble to the Final Rule at 7181.

- ^ Doug Gurian-Sherman. April 2008. CAFOs Uncovered: The Untold Costs of Confined Animal Feeding Operations, Union of Concerned Scientists, Cambridge, MA.

- ^ MacDonald, J.M. and McBride, W.D. (2009). The transformation of U.S. livestock agriculture: Scale, efficiency, and risks. United States Department of Agriculture.

- ^ e.g., Burkholder et al. 1997; Mallin 2000

- ^ Wing, Steve; Johnston, Jill (August 29, 2014). "Industrial Hog Operations in North Carolina Disproportionately Impact African-Americans, Hispanics and American Indians" (PDF). NC Policy Watch. Raleigh, NC.

- ^ Institute of Science, Technology and Public Policy, Maharishi University of Management, Assessment of Impacts on Health, Local Economies, and the Environment with Suggested Alternatives

- ^ "Facts about Pollution from Livestock Farms". Environmental Issues: Water. New York, NY: Natural Resource Defense Council. 2011-01-13. Archived from the original on 2011-12-07.

- ^ a b c Gibbs, Shawn G.; Green, Christopher F.; Tarwater, Patrick M.; Mota, Linda C.; Mena, Kristina D.; Scarpino, Pasquale V. (2006). "Isolation of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria from the Air Plume Downwind of a Swine Confined or Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation". Environmental Health Perspectives. 114 (7): 1032–1037. doi:10.1289/ehp.8910. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 1513331. PMID 16835055.

- ^ Ferguson, Dwight D.; Smith, Tara C.; Hanson, Blake M.; Wardyn, Shylo E.; Donham, Kelley J. (2016). "Detection of Airborne Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Inside and Downwind of a swine Building, and in Animal Feed: Potential Occupational, Animal Health, and Environmental Implications". Journal of Agromedicine. 21 (2): 149–153. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2016.1142917. ISSN 1059-924X. PMC 4927327. PMID 26808288.

- ^ "Trace Gases: Current Observations, Trends, and Budgets", Climate Change 2001, IPCC Third Assessment Report. IPCC/United Nations Environment Programme

- ^ David N. Cassuto, The CAFO Hothouse: Climate Change, Industrial Agriculture and the Law

- ^ EPA (1999). "U.S. methane emissions 1990–2020: Inventories, Projections, and Opportunities for Reduction." EPA 430-R-99-01.

- ^ a b H. Augenbraun [1] Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine Augenbraun, H., Matthews, E., & Sarma, D. (1997). "The Global Methane Cycle"

- ^ B. Metz [2] Archived 2011-12-20 at the Wayback Machine Metz, B., Davidson, O., Bosch, P., Dave, R., & Meyer, L. (Eds.) (2007). Chapter 8: Agriculture. In IPCC Fourth Assessment Report: Climate Change 2007, "Mitigation of Climate Change". Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ States, The Humane Society of the United (2008). "An HSUS Report: Human Health Implications of Non-Therapeutic Antibiotic Use in Animal Agriculture". Animal Studies Repository.

- ^ Kumar, S., Puniya, A.K., Puniya, M., Dagar, S.S., Sirohi, S.K., Singh, K., Griffith, G.W. (2009). "Factors affecting rumen methanogens and methane mitigation strategies". World J. Microbiol Biotechnol, 25:1557–1566

- ^ "Climate Impacts on Human Health: Air Quality Impacts". EPA. 2017-01-13. Retrieved 2017-10-24.

- ^ McMichael, A. J., Powles, J. W., Butler, C. D., & Uauy, R. (2007). "Food, livestock, production, energy, climate change, and health". The Lancet, 1253–1263

- ^ a b Nicole, Wendee (June 1, 2013). "CAFOs and Environmental Justice: The Case of North Carolina". Environ Health Perspect. 121 (6): a182 – a189. doi:10.1289/ehp.121-a182. PMC 3672924. PMID 23732659.

- ^ Putting Meat on the table: Industrial Farm Animal Production, Report of Pew Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Production

- ^ United States. National Agricultural Statistics Service. Farms and Land in Farms. February 2002

- ^ Oksana Nagayet. “Small Farms: Current Status and Key Trends.” Wye College. 26 June 2005

- ^ Robert A. Hoppe, Penni Korb, Erik J. O’Donoghue, and David E. Banker, Structure and Finances of U.S. Farms, Family Farm Report, 2007 Edition, http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/201419/eib24_reportsummary_1_.pdf

- ^ MacDonald, J.M. and McBride, W.D. (2009). The transformation of U.S. livestock agriculture: Scale, efficiency, and risks. United States Department of Agriculture. http://www.ers.usda.gov/Publications/EIB43/EIB43.pdf

- ^ a b Hribar, Carrie (2010). "Understanding Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations and Their Impact on Communities" (PDF).

- ^ https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/Docs/Understanding_CAFOs_NALBOH.pdf

- ^ Delgado, CL (2003). "Rising rates of the consumption of meat and milk in developing countries has created a new food revolution". Journal of Nutrition. 133 (11 Suppl 2): 3907S – 3910S. doi:10.1093/jn/133.11.3907S. PMID 14672289.

- ^ Steven C. Blank (April 1999). The end of american farm Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Daryll E. Ray and the Agricultural Policy Analysis Center, TN. CAFO critics promote alternative approaches to production Archived 2011-08-21 at the Wayback Machine, University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

- ^ a b c William J. Weida (Jan. 5, 2000). "Economic Implications of Confined Animal Feeding Operations" Archived 2011-08-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Understanding Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations and Their Impact on Communities.

- ^ Jonathan Wales (Sept.–Oct. 2007). [www.bizvoicemagazine.com/archives/07sepoct/Agriculture.pdf "Agricultural Values on the Rise"] BuzVoice.

- ^ Jonathan Wales (Sept.–Oct. 2007). [www.bizvoicemagazine.com/archives/07sepoct/Agriculture.pdf "Agricultural Values on the Rise"]. BuzVoice

- ^ Jonathan Wales (Sept.–Oct. 2007). [www.bizvoicemagazine.com/archives/07sepoct/Agriculture.pdf "Agricultural Values on the Rise"]. BuzVoice.

- ^ John Ikerd. “Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations and the Future of Agriculture”. University of Missouri, Columbia.

- ^ Becker, Geoffrey S. Farm Commodity Programs: A Short Primer. Congressional Research Service. 20 June 2002.

- ^ Walsh, Bryan (May 25, 2011). "Environmental Groups Sue the FDA Over Antibiotics and Meat Production". Time. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ Walker, Polly; Rhubart-Berg, Pamela; McKenzie, Shawn; Kelling, Kristin; Lawrence, Robert S. (2005). "Public health implications of meat production and consumption". Public Health Nutrition. 8 (4): 348–356. doi:10.1079/PHN2005727. ISSN 1475-2727. PMID 15975179.

- ^ (EPA 2004)

- ^ a b Burkholder, JoAnn; Libra, Bob; Weyer, Peter; Heathcote, Susan; Kolpin, Dana; Thorne, Peter S.; Wichman, Michael (2006). "Impacts of Waste from Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations on Water Quality". Environmental Health Perspectives. 115 (2): 308–312. doi:10.1289/ehp.8839. PMC 1817674. PMID 17384784.

- ^ a b Finley, Rita L.; Collignon, Peter; Larsson, D. G. Joakim; McEwen, Scott A.; Li, Xian-Zhi; Gaze, William H.; Reid-Smith, Richard; Timinouni, Mohammed; Graham, David W. (2013-09-01). "The Scourge of Antibiotic Resistance: The Important Role of the Environment". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 57 (5): 704–710. doi:10.1093/cid/cit355. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 23723195.

- ^ World Health Organization(WHO). "Antibiotic use in food-producing animals must be curtailed to prevent increased resistance in humans". Press Release WHO/73. Geneva: WHO, 1997.

- ^ a b c Bos, Marian E H; Verstappen, Koen M; Cleef, Brigitte A G L van; Dohmen, Wietske; Dorado-García, Alejandro; Graveland, Haitske; Duim, Birgitta; Wagenaar, Jaap A; Kluytmans, Jan A J W (2016). "Transmission through air as a possible route of exposure for MRSA". Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology. 26 (3): 263–269. doi:10.1038/jes.2014.85. ISSN 1559-064X. PMID 25515375. S2CID 37597687.

- ^ "Antibiotic resistance". World Health Organization. 2017. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- ^ Landers, T. F. (2012). "A Review of Antibiotic Use in Food Animals: Perspective, Policy, and Potential". Public Health Reports. 127 (1): 4–22. doi:10.1177/003335491212700103. PMC 3234384. PMID 22298919.

- ^ Douglas, Philippa; Robertson, Sarah; Gay, Rebecca; Hansell, Anna L.; Gant, Timothy W. (2017). "A systematic review of the public health risks of bioaerosols from intensive farming". International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 221 (2): 134–173. doi:10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.10.019. hdl:10044/1/54616. PMID 29133137.

- ^ Understanding Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations and Their Impact on communities.

- ^ Hooiveld, Mariëtte; Smit, Lidwien A. M.; van der Sman-de Beer, Femke; Wouters, Inge M.; van Dijk, Christel E.; Spreeuwenberg, Peter; Heederik, Dick J. J.; Yzermans, C. Joris (2016). "Doctor-diagnosed health problems in a region with a high density of concentrated animal feeding operations: a cross-sectional study". Environmental Health. 15: 24. doi:10.1186/s12940-016-0123-2. ISSN 1476-069X. PMC 4758110. PMID 26888643.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Borlée, Floor; Yzermans, C. Joris; Aalders, Bernadette; Rooijackers, Jos; Krop, Esmeralda; Maassen, Catharina B. M.; Schellevis, François; Brunekreef, Bert; Heederik, Dick (2017). "Air Pollution from Livestock Farms Is Associated with Airway Obstruction in Neighboring Residents". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 196 (9): 1152–1161. doi:10.1164/rccm.201701-0021oc. PMID 28489427. S2CID 34473838.

- ^ Schmidt, Charles W. (September 4, 2009). Swine CAFOs and Novel H1N1 Influenza,Environmental Health Perspectives.

- ^ Schmidt, Charles W. Swine CAFOs & Novel H1N1 Flu Separating Facts from Fears Archived 2010-05-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Romberger, Debra J.; Heires, Art J.; Nordgren, Tara M.; Poole, Jill A.; Toews, Myron L.; West, William W.; Wyatt, Todd A. (2016). "β2-Adrenergic agonists attenuate organic dust-induced lung inflammation". American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 311 (1): L101 – L110. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00125.2016. ISSN 1040-0605. PMC 4967192. PMID 27190062.

- ^ Merchant, JA; Naleway, AL; Svendsen, ER; Kelly, KM; Burmeister, LF; Stromquist, AM; et al. (2005). "Asthma and farm exposures in a cohort of rural Iowa children". Environmental Health Perspectives. 113 (3): 350–6. doi:10.1289/ehp.7240. PMC 1253764. PMID 15743727.

- ^ Ball-Blakely, Christine (Fall 2017). "CAFOS: Plaguing North Carolina Communities of Color". Sustainable Development Law & Policy – via American University Washington College of Law.

- ^ "Right To Farm".

- ^ Quandt, Sara A.; Arcury‐Quandt, Alice E.; Lawlor, Emma J.; Carrillo, Lourdes; Marín, Antonio J.; Grzywacz, Joseph G.; Arcury, Thomas A. (2013). "3-D jobs and health disparities: The health implications of latino chicken catchers' working conditions". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 56 (2): 206–215. doi:10.1002/ajim.22072. ISSN 1097-0274. PMID 22618638.

- ^ F. M. Mitloehner; M. S. Calvo (2008). "Worker Health and Safety in Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations". Journal of Agricultural Safety and Health. 14 (2): 163–187. doi:10.13031/2013.24349. ISSN 1943-7846. PMID 18524283.

- ^ Phillips, Clive, The Welfare Of Animals: The Silent Majority, Springer, 2009

- ^ Sun-Sentinel/Associated Press (November 6, 2002). Tallahassee

- ^ “EU bans battery hen cages”, BBC News, January 28, 1999.

- ^ Imhoff, Dan (2011-05-25). "Honoring The Food Animals On Your Plate". Huffington Post.

- ^ Ebner, Paul (2007). CAFOs and Public Health: The Issue of Antibiotic Resistance (PDF) (Report). Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service. ID-349.

- ^ Bauman, Dale E.; Capper, Jude L. (2008). "Efficiency of Dairy Production and its Carbon Footprint" (PDF). dairy.ifas.ufl.edu/. University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ 33 U.S.C. 1362.

- ^ a b Claudia Copeland, Animal Waste and Water Quality: EPA's Response to the Waterkeeper Alliance Court Decision on Regulation of CAFOs, in WATER POLLUTION ISSUES AND DEVELOPMENTS 77 (Sarah V. Thomas, ed., 2008).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, "Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations Final Rulemaking - Q&A (Dec. 3, 2008).

- ^ a b c Claudia Copeland, Animal Waste and Water Quality: EPA's Response to the Waterkeeper Alliance "Court Decision on Regulation of CAFOs", in Water Pollution Issues and Developments 82 (Sarah V. Thomas, ed., 2008).

- ^ Frank R. Spellmen & Nancy E. Whiting, Environmental Management of Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) 29 (2007).

- ^ EPA – CAFO Rule History Archived November 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Federal Water Pollution Control Act (Clean Water Act)." Digest of Federal Resource Laws of Interest to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

- ^ Reorganization Plan No. 3 of 1970 | EPA History | US EPA Archived 2007-07-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ United States. Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972. Pub.L. 92-500, October 18, 1972.

- ^ a b c EPA (December 1995). "Guide Manual On NPDES Regulations For Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations." EPA 833-B-95-001.

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 39 Federal Register 5704.

- ^ a b c d U.S. Government Accountability Office, Washington, D.C. "Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations: EPA Needs More Information and a Clearly Defined Strategy to Protect Air and Water Quality from Pollutants of Concern." Report GAO-08-944.

- ^ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 41 Federal Register 11,458

- ^ EPA – Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations – Final Rule

- ^ Office of Wastewater Management - Small Communities

- ^ EPA - AFO Unified Strategy

- ^ a b c d USDA and EPA (2012). "Unified National AFO Strategy Executive Summary."

- ^ Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFO) Rule; Information Sheet (PDF) (Report). EPA. 2002. EPA 833-G-02-014.

- ^ a b "Animal Feeding Operations CAFO Rule Animal Waste Program - Department of Biological And Agricultural Engineering at NC State University". Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- ^ EPA. "Final Rule: National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System Permit Regulation and Effluent Limitation Guidelines and Standards for Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs)". Federal Register, February 12, 2003.

- ^ a b c d e Claudia Copeland, Animal Waste and Water Quality: EPA's Response to the Waterkeeper Alliance "Court Decision on Regulation of CAFOs," in Water Pollution Issues and Developments 78 (Sarah V. Thomas, ed., 2008).

- ^ Claudia Copeland, Animal Waste and Water Quality: EPA's Response to the Waterkeeper Alliance Court Decision on Regulation of CAFOs, in WATER POLLUTION ISSUES AND DEVELOPMENTS 77–78 (Sarah V. Thomas, ed., 2008).