Boeing 737

| Boeing 737 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Boeing 737-700 with blended winglets of Southwest Airlines, the type's largest operator | |

| Role | Narrow-body jet airliner and Business jet |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Boeing Commercial Airplanes |

| First flight | April 9, 1967 |

| Introduction | February 10, 1968, with Lufthansa |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Southwest Airlines Ryanair United Airlines American Airlines |

| Produced | 1966–present |

| Number built | 9,247 as of October 2016[1] |

| Variants | Boeing T-43 |

| Developed into | Boeing 737 Classic Boeing 737 Next Generation Boeing 737 MAX |

The Boeing 737 is an American short- to medium-range twinjet narrow-body airliner. Originally developed as a shorter, lower-cost twin-engine airliner derived from Boeing's 707 and 727, the 737 has developed into a family of ten passenger models with capacities from 85 to 215 passengers. The 737 is Boeing's only narrow-body airliner in production, with the 737 Next Generation (-700, -800, and -900ER) variants currently being built. Production has also begun on the re-engined and redesigned 737 MAX, which is set to enter service in 2017.

Originally envisioned in 1964, the initial 737-100 made its first flight in April 1967 and entered airline service in February 1968 at Lufthansa.[2][3] Next, the lengthened 737-200 entered service in April 1968. In the 1980s Boeing launched the -300, -400, and -500 models, subsequently referred to as the Boeing 737 Classic series. The 737 Classics added capacity and incorporated CFM56 turbofan engines along with wing improvements.

In the 1990s, Boeing introduced the 737 Next Generation, with multiple changes including a redesigned, increased span laminar flow wing, upgraded "glass" cockpit, and new interior. The 737 Next Generation comprises the four -600, -700, -800, and -900 models, ranging from 102 ft (31.09 m) to 138 ft (42.06 m) in length. Boeing Business Jet versions of the 737 Next Generation are also produced.

The 737 series is the best-selling jet commercial airliner.[2] The 737 has been continuously manufactured by Boeing since 1967 with 9,247 aircraft delivered and 4,321 orders yet to be fulfilled as of October 2016[update].[1] 737 assembly is centered at the Boeing Renton Factory in Renton, Washington. Many 737s serve markets previously filled by 707, 727, 757, DC-9, and MD-80/MD-90 airliners, and the aircraft currently competes primarily with the Airbus A320 family.[4] As of 2006, there were an average of 1,250 Boeing 737s airborne at any given time, with two departing or landing somewhere every five seconds.[5]

Development

Background

Boeing had been studying short-haul jet aircraft designs and wanted to produce another aircraft to supplement the 727 on short and thin routes.[6] Preliminary design work began on May 11, 1964,[7] and Boeing's intense market research yielded plans for a 50- to 60-passenger airliner for routes 50 to 1,000 mi (80 to 1,609 km) long.[6][8] Lufthansa became the launch customer on February 19, 1965,[9] with an order for 21 aircraft, worth $67 million[10] in 1965, after the airline received assurances from Boeing that the 737 project would not be canceled.[11] Consultation with Lufthansa over the previous winter resulted in an increase in capacity to 100 seats.[9]

On April 5, 1965, Boeing announced an order by United Airlines for 40 737s. United wanted a slightly larger airplane than the original 737. So Boeing stretched the fuselage 91 centimeters (36 in) ahead of, and 102 cm (40 in) behind the wing.[12] The longer version was designated 737-200, with the original short-body aircraft becoming the 737-100.[13]

Detailed design work continued on both variants at the same time. Boeing was far behind its competitors when the 737 was launched, as rival aircraft BAC-111, Douglas DC-9, and Fokker F28 were already into flight certification.[10] To expedite development, Boeing used 60% of the structure and systems of the existing 727, the most notable being the fuselage cross-section. This fuselage permitted six-abreast seating compared to the rival BAC-111 and DC-9's five-abreast layout.[9] Design engineers decided to mount the nacelles directly to the underside of the wings to reduce the landing gear length and kept the engines low to the ground for easy ramp inspection and servicing.[14] Many thickness variations for the engine attachment strut were tested in the wind tunnel and the most desirable shape for high speed was found to be one which was relatively thick, filling the narrow channels formed between the wing and the top of the nacelle, particularly on the outboard side. Originally, the span arrangement of the airfoil sections of the 737 wing was planned to be very similar to that of the 707 and 727, although somewhat thicker. However, a substantial improvement in drag at high Mach numbers was achieved by altering these sections near the nacelle.[15] The engine chosen was the Pratt & Whitney JT8D-1 low-bypass ratio turbofan engine, delivering 14,500 lbf (64 kN) thrust.[16] With the wing-mounted engines, Boeing decided to mount the horizontal stabilizer on the fuselage rather than the T-tail style of the Boeing 727.[12]

Production and testing

The initial assembly of the 737 was adjacent to Boeing Field (now officially named King County International Airport) because the factory in Renton was filled to capacity with the building of the 707 and 727. After 271 aircraft were built, production moved to Renton in late 1970.[11][17] A significant portion of fuselage assembly occurs in Wichita, Kansas, which was previously done by Boeing but now by Spirit AeroSystems, which purchased some of Boeing's assets in Wichita.[18][19]

The fuselage is joined with the wings and landing gear, then moves down the assembly line for the engines, avionics, and interiors. After rolling out the aircraft, Boeing tests the systems and engines before its maiden flight to Boeing Field, where it is painted and fine-tuned before delivery to the customer.[20]

The first of six -100 prototypes rolled out in December 1966, and made its maiden flight on April 9, 1967, piloted by Brien Wygle and Lew Wallick.[21] On December 15, 1967, the Federal Aviation Administration certified the -100 for commercial flight,[22] issuing Type Certificate A16WE.[23] The 737 was the first aircraft to have, as part of its initial certification, approval for Category II approaches.[24] Lufthansa received its first aircraft on December 28, 1967, and on February 10, 1968, became the first non-American airline to launch a new Boeing aircraft.[22] Lufthansa was the only significant customer to purchase the 737-100. Only 30 aircraft were produced.[25]

The 737-200 had its maiden flight on August 8, 1967. It was certified by the FAA on December 21, 1967,[23][26] and the inaugural flight for United was on April 28, 1968, from Chicago to Grand Rapids, Michigan.[22] The lengthened -200 was widely preferred over the -100 by airlines.[27]

Initial derivatives

The original engine nacelles incorporated thrust reversers taken from the 727 outboard nacelles. However, they proved to be relatively ineffective and apparently tended to lift the aircraft up off the runway when deployed. This reduced the downforce on the main wheels thereby reducing the effectiveness of the wheel brakes. In 1968, an improvement to the thrust reversal system was introduced.[28] A 48-inch tailpipe extension was added and new, target-style, thrust reversers were incorporated. The thrust reverser doors were set 35 degrees away from the vertical to allow the exhaust to be deflected inboard and over the wings and outboard and under the wings.[29] The improvement became standard on all aircraft after March 1969, and a retrofit was provided for active aircraft. Boeing fixed the drag issue by introducing new longer nacelle/wing fairings, and improved the airflow over the flaps and slats. The production line also introduced an improvement to the flap system, allowing increased use during takeoff and landing. All these changes gave the aircraft a boost to payload and range, and improved short-field performance.[22] In May 1971, after aircraft #135, all improvements, including more powerful engines and a greater fuel capacity, were incorporated into the 737-200, giving it a 15% increase in payload and range over the original -200s.[24] This became known as the 737-200 Advanced, which became the production standard in June 1971.[30]

In 1970, Boeing received only 37 orders. Facing financial difficulties, Boeing considered closing the 737 production-line and selling the design to Japanese aviation companies.[11] After the cancellation of the Boeing Supersonic Transport, and scaling back of 747 production, enough funds were freed up to continue the project.[31] In a bid to increase sales by offering a variety of options, Boeing offered a 737C (Convertible) model in both -100 and -200 lengths. This model featured a 340 cm × 221 cm (134 in × 87 in) freight door just behind the cockpit, and a strengthened floor with rollers, which allowed for palletized cargo. A 737QC (Quick Change) version with palletized seating allowed for faster configuration changes between cargo and passenger flights.[32] With the improved short-field capabilities of the 737, Boeing offered the option on the -200 of the gravel kit, which enables this aircraft to operate on remote, unpaved runways.[33][34] Until retiring its -200 fleet in 2007, Alaska Airlines used this option for some of its rural operations in Alaska.[35] Northern Canadian operators Air Inuit, Air North, Canadian North, First Air and Nolinor Aviation still operate the gravel kit aircraft in Northern Canada, where gravel runways are common.

In 1988, the initial production run of the -200 model ended after producing 1,114 aircraft. The last one was delivered to Xiamen Airlines on August 8, 1988.[36][37]

Improved variants

Development began in 1979 for the 737's first major revision. Boeing wanted to increase capacity and range, incorporating improvements to upgrade the aircraft to modern specifications, while also retaining commonality with previous 737 variants. In 1980, preliminary aircraft specifications of the variant, dubbed 737-300, were released at the Farnborough Airshow.[38]

Boeing engineer Mark Gregoire led a design team, which cooperated with CFM International to select, modify and deploy a new engine and nacelle that would make the 737-300 into a viable aircraft. They chose the CFM56-3B-1 high-bypass turbofan engine to power the aircraft, which yielded significant gains in fuel economy and a reduction in noise, but also posed an engineering challenge, given the low ground clearance of the 737 and the larger diameter of the engine over the original Pratt & Whitney engines. Gregoire's team and CFM solved the problem by reducing the size of the fan (which made the engine slightly less efficient than it had been forecast to be), placing the engine ahead of the wing, and by moving engine accessories to the sides of the engine pod, giving the engine a distinctive non-circular "hamster pouch"[39] air intake.[40][41] Earlier customers for the CFM56 included the U.S. Air Force with its program to re-engine KC-135 tankers.[42]

The passenger capacity of the aircraft was increased to 149 by extending the fuselage around the wing by 2.87 meters (9 ft 5 in). The wing incorporated a number of changes for improved aerodynamics. The wingtip was extended 9 in (23 cm), and the wingspan by 1 ft 9 in (53 cm). The leading-edge slats and trailing-edge flaps were adjusted.[40] The tailfin was redesigned, the flight deck was improved with the optional EFIS (Electronic Flight Instrumentation System), and the passenger cabin incorporated improvements similar to those developed on the Boeing 757.[43] The prototype -300, the 1,001st 737 built, first flew on 24 February 1984 with pilot Jim McRoberts.[43] It and two production aircraft flew a nine-month-long certification program.[44]

In June 1986, Boeing announced the development of the 737-400,[45] which stretched the fuselage a further 10 ft (3.0 m), increasing the passenger load to 188.[46] The -400s first flight was on February 19, 1988, and, after a seven-month/500-hour flight-testing run, entered service with Piedmont Airlines that October.[47]

The -500 series was offered, due to customer demand, as a modern and direct replacement of the 737-200. It incorporated the improvements of the 737 Classic series, allowing longer routes with fewer passengers to be more economical than with the 737-300. The fuselage length of the -500 is 1 ft 7 in (48 cm) longer than the 737-200, accommodating up to 140[48] passengers. Both glass and older-style mechanical cockpits arrangements were available.[47] Using the CFM56-3 engine also gave a 25% increase in fuel efficiency over the older -200s P&W engines.[47]

The 737-500 was launched in 1987 by Southwest Airlines, with an order for 20 aircraft,[49] and flew for the first time on June 30, 1989.[47] A single prototype flew 375 hours for the certification process,[47] and on February 28, 1990, Southwest Airlines received the first delivery.[50]

After the introduction of the -600/700/800/900 series, the -300/400/500 series was called the 737 Classic series.[51]

The price of jet fuel reached a peak in 2008, when airlines devoted 40% of the retail price of an air ticket to pay for fuel, versus 15% in 2000.[52][53] Consequently, in that year carriers retired Classic 737 series aircraft to reduce fuel consumption; replacements consisted of more efficient Next Generation 737s or Airbus A320/A319/A318 series aircraft. On June 4, 2008, United Airlines announced it would retire all 94 of its Classic 737 aircraft (64 737-300 and 30 737-500 aircraft), replacing them with Airbus A320 jets taken from its Ted subsidiary, which has been shut down.[54][55][56]

Next-Generation models

Prompted by the modern Airbus A320, Boeing initiated development of an updated series of aircraft in 1991.[57] After working with potential customers, the 737 Next Generation (NG) program was announced on November 17, 1993.[58] The 737NG encompasses the -600, -700, -800, and -900, and is to date the most significant upgrade of the airframe. The performance of the 737NG is, in essence, that of a new aircraft, but important commonality is retained from previous 737 models.[59]

The wing was redesigned with a new airfoil section, greater chord, increased wing span by 16 ft (4.9 m) and area by 25%, which increased total fuel capacity by 30%. New, quieter, more fuel-efficient CFM56-7B engines were used.[60] The wing, engine, and fuel capacity improvements combined increase the 737's range by 900 nautical miles to over 3,000 nautical miles (5,600 km),[61] now permitting transcontinental service.[58] With the increased fuel capacity, higher maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) specifications are offered. The 737NG included redesigned vertical stabilizers, and winglets were available on most models.[62] The flight deck was upgraded with modern avionics, and passenger cabin improvements similar to those on the Boeing 777, including more curved surfaces and larger overhead bins than previous-generation 737s. The Next Generation 737 interior was also adopted on the Boeing 757-300.[63][64]

The first NG to roll out was a -700, on December 8, 1996. This aircraft, the 2,843rd 737 built, first flew on February 9, 1997. The prototype -800 rolled out on June 30, 1997, and first flew on July 31, 1997. The smallest of the new variants, the -600s, is the same size as the -500. It was the last in this series to launch, in December 1997. First flying January 22, 1998, it was given certification on August 18, 1998.[58][65] A flight test program was operated by 10 aircraft; 3 -600s, 4 -700s, and 3 -800s.[58]

In 2004, Boeing offered a Short Field Performance package in response to the needs of Gol Transportes Aéreos, which frequently operates from restricted airports. The enhancements improve takeoff and landing performance. The optional package is available for the 737NG models and standard equipment for the 737-900ER. The CFM56-7B Evolution nacelle began testing in August 2009 to be used on the new 737 PIP (Performance Improvement Package) due to enter service mid-2011. This new improvement is said to shave at least 1% off overall drag and have some weight benefits. Overall, it is claimed to have a 2% improvement on fuel burn on longer stages.[66] In 2010, new interior options for the 737NG included the 787-style Boeing Sky Interior.[66]

Boeing delivered the 5,000th 737 to Southwest Airlines on February 13, 2006. Boeing delivered the 6,000th 737 to Norwegian Air Shuttle in April 2009. Boeing delivered the 8,000th 737 to United Airlines on April 16, 2014.[67] The Airbus A320 family has outsold the 737NG over the past decade,[68][69][70] although its order totals include the A321 and A318, which have also rivaled Boeing's 757 and 717, respectively.[4] The 737NG has also outsold the A320 on an annual basis in past years,[71][72][73][74][75] with the next generation series extending the jetliner's run as the most widely sold[76][77][78] and commonly flown airliner family since its introduction.[79][80][81][82][83][84] The 10,000th aircraft was ordered in July 2012.[85]

Boeing produces 42 of the type per month in 2015, and expects to increase to 52 per month in 2018.[86] The slow selling 737-600 is no longer being marketed and was removed from the Boeing website as of 2016, its position as the smallest model being taken by the more popular 737-700.[87]

Replacement or re-engining

Since 2006, Boeing has discussed replacing the 737 with a "clean sheet" design (internally named "Boeing Y1") that could follow the Boeing 787 Dreamliner.[88] A decision on this replacement was postponed, and delayed into 2011.[89] In November 2014, it was reported that Boeing plans to develop a new aircraft to replace the 737 in the 2030 time frame. The airplane is to have a similar fuselage, but probably made from composite materials similar to the Boeing 787 Dreamliner.[90] Boeing also considers a parallel development along with the 757 replacement, similar to when the 757/767 were developed in the 1970s.[91]

On July 20, 2011, Boeing announced plans for a new 737 version to be powered by the CFM International LEAP-X engine, with American Airlines intending to order 100 of these aircraft.[92] On August 30, 2011, Boeing confirmed the launch of the 737 new engine variant, called the 737 MAX,[93] with new CFM International LEAP-1B engines.[94][95][96]

On September 23, 2015, Boeing announced a collaboration with Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China Ltd. to build a completion and delivery facility for the 737 in China, the first outside the U.S.[97][98]

Design

The 737's main landing gear under the wings at mid-cabin rotates into wells in the aircraft's belly. The legs are covered by partial doors, and "brush-like" seals aerodynamically smooth (or "fair") the wheels in the wells. The sides of the tires are exposed to the air in flight. "Hub caps" complete the aerodynamic profile of the wheels. It is forbidden to operate without the caps, because they are linked to the ground speed sensor that interfaces with the anti-skid brake system. The dark circles of the tires are clearly visible when a 737 takes off, or is at low altitude.[99]

737s are not equipped with fuel dump systems. The original aircraft were too small to require them, and adding a fuel dump system to the later, larger variants would have incurred a large weight penalty. Boeing instead demonstrated an "equivalent level of safety". Depending upon the nature of the emergency, 737s either circle to burn off fuel or land overweight. If the latter is the case, the aircraft is inspected by maintenance personnel for damage and then returned to service if none is found.[100][101]

Engines

Engines on the 737 Classic series (300, 400, 500) and Next-Generation series (600, 700, 800, 900) do not have circular inlets like most aircraft. The 737 Classic series featured CFM56 turbofan engines, which yielded significant gains in fuel economy and a reduction in noise over the JT8D engines used on the -100 and -200, but also posed an engineering challenge given the low ground clearance of the 737. Boeing and engine supplier CFMI solved the problem by placing the engine ahead of (rather than below) the wing, and by moving engine accessories to the sides (rather than the bottom) of the engine pod, giving the 737 a distinctive non-circular air intake.[40]

The wing also incorporated a number of changes for improved aerodynamics. The engines' accessory gearbox was moved from the 6 o'clock position under the engine to the 4 o'clock position (from a front/forward looking aft perspective). This side-mounted gearbox gives the engine a somewhat triangular rounded shape. Because the engine is close to the ground, 737-300s and later models are more prone to engine foreign object damage (FOD). The improved CFM56-7 turbofan engine on the 737 Next Generation is 7% more fuel-efficient than the previous CFM56-3 in the 737 classics. The newest 737 variants, the 737 MAX family, are to feature CFM International LEAP-1B engines with a 1.73 m fan diameter. These engines are expected to be 10-12% more efficient than the CFM56-7B engines on the 737 Next Generation family.[102]

Flight systems

The primary flight controls are intrinsically safe. In the event of total hydraulic system failure or double engine failure, they will automatically and seamlessly revert to control via servo tab. In this mode, the servo tabs aerodynamically control the elevators and ailerons; these servo tabs are in turn controlled by cables running to the control yoke. The pilot's muscle forces alone control the tabs. For the 737 Next Generation, a six-screen LCD glass cockpit with modern avionics was implemented while retaining crew commonality with previous generation 737.[103]

Most 737 cockpits are equipped with "eyebrow windows" positioned above the main glareshield. Eyebrow windows were a feature of the original 707 and 727.[104] They allowed for greater visibility in turns, and offered better sky views if navigating by stars. With modern avionics, they became redundant, and many pilots actually placed newspapers or other objects in them to block out sun glare. They were eliminated from the 737 cockpit design in 2004, although they are still installed at customer request.[105] These windows are sometimes removed and plugged, usually during maintenance overhauls, and can be distinguished by the metal plug which differs from the smooth metal in later aircraft that were not originally fitted with the windows.[105]

Upgrade packages

Winglets

The 737 has four different winglet types: 737-200 Mini-winglet, 737 Classic/NG Blended Winglet, 737 Split Scimitar Winglet, and 737 Max Advanced Technology Winglet.[105] The 737-200 Mini-winglets are part of the Quiet Wing Corp modification kit that received certification in 2005.[105]

Blended winglets are in production on 737 NG aircraft and are available for retrofit on 737 Classic models. These winglets stand approximately 8 feet (2.4 m) tall and are installed at the wing tips. They help to reduce fuel burn (by reducing vortex drag), engine wear, and takeoff noise. Overall fuel efficiency improvement is up to five percent through the reduction of lift-induced drag.[106][107]

Split Scimitar winglets became available in 2014 for the 737-800, 737-900ER, BBJ2 and BBJ3, and in 2015 for the 737-700, 737-900 and BBJ1.[108] Split Scimitar winglets were developed by Aviation Partners Inc. (API), the same Seattle based corporation that developed the blended winglets; the Split Scimitar winglets produce up to a 5.5% fuel savings per aircraft compared to 3.3% savings for the blended winglets. Southwest Airlines flew their first flight of a 737-800 with Split Scimitar winglets on April 14, 2014.[109] The next generation 737, 737 Max, will feature an Advanced Technology (AT) Winglet that is produced by Boeing. The Boeing AT Winglet resembles a cross between the Blended Winglet and the Split Scimitar Winglet.[110]

Carbon brakes

As of July 2008[update] the 737 features carbon brakes manufactured by Messier-Bugatti. These new brakes, now certified by the Federal Aviation Administration, weigh 550–700 lb (250–320 kg) less than the steel brakes normally fitted to the Next-Gen 737s (weight savings depend on whether standard or high-capacity brakes are fitted).[111] A weight reduction of 700 pounds on a Boeing 737-800 results in 0.5% reduction in fuel burn.[112]

Short-field design package

A short-field design package is available for the 737-600, -700, and -800, allowing operators to fly increased payload to and from airports with runways under 5,000 feet (1,500 m). The package consists of sealed leading edge slats (improved lift), a two-position tail skid (enabling greater protection against tail strikes that may be caused by the lower landing speeds), and increased flight spoiler deflection on the ground. These improvements are standard on the 737-900ER.[113]

Interior

The 737 interior arrangement has changed in successive generations. The original 737 interior was restyled for the 737 Classic models using 757 designs, while 777 architecture was used for the debut of the Next Generation 737. Designed using Boeing's new cabin concepts, the latest Sky Interior features sculpted sidewalls and redesigned window housings, along with increased headroom and LED mood lighting.[66][114] Larger pivot-bins similar to those on the 777 and 787 have more luggage space than prior designs.[114] The Sky Interior is also designed to improve cabin noise levels by 2–4 dB.[66] The first 737 equipped with the Boeing Sky Interior was delivered to Flydubai in late 2010.[66] Continental Airlines,[115][116] Malaysia Airlines,[117] and TUIFly have also received Sky Interior-equipped 737s.[118]

Variants

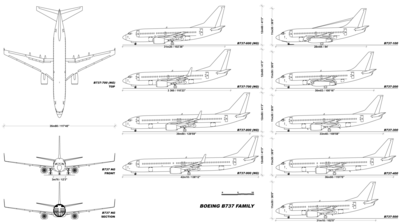

The 737 models can be divided into three generations, including nine major variants. The "Original" models consist of the 737-100, 737-200/-200 Advanced. The "Classic" models consist of the 737-300, 737-400, and 737-500. The "Next Generation" variants consist of the 737-600, 737-700/-700ER, 737-800, and 737-900/-900ER. Of these nine variants, many feature additional versions such as the T-43, which was a modified Boeing 737-200 used by the United States Air Force (USAF).

The fourth generation derivative - the 737 MAX - is currently under development and will encompass the 737-MAX-7, 737-MAX-8, and 737-MAX-9 which will replace the -700, -800 and -900/900ER versions of the NG family, respectively.

737 Original series

737-100

The initial model was the 737-100. It was launched in February 1965. The -100 was rolled out on January 17, 1967, had its first flight on April 9, 1967 and entered service with Lufthansa in February 1968. The aircraft is the smallest variant of the 737. A total of 30 737-100s were ordered and delivered; the final commercial delivery took place on October 31, 1969 to Malaysia–Singapore Airlines. No 737-100s remain in commercial service. The original Boeing prototype, last operated by NASA and retired more than 30 years after its maiden flight, is on exhibit in the Museum of Flight in Seattle.[58]

737-200

The 737-200 is a 737-100 with an extended fuselage, launched by an order from United Airlines in 1965. The -200 was rolled out on June 29, 1967, and entered service at United in April 1968. The 737-200 Advanced is an improved version of the -200, introduced into service by All Nippon Airways on May 20, 1971.[119] The -200 Advanced has improved aerodynamics, automatic wheel brakes, more powerful engines, more fuel capacity, and longer range than the -100.[120] Boeing also provided the 737-200C (Cargo), which allowed for conversion between passenger and cargo use and the 737-200QC (Quick Change), which facilitated a rapid conversion between roles. The 1,095th and last delivery of a -200 series aircraft was in August 1988 to Xiamen Airlines.[1][59] Many 737-200s have been phased out or replaced by newer 737 versions. In July 2015, there were a combined 99 Boeing 737-200s in service, mostly with "second and third tier" airlines, and those of developing nations.[121]

With a gravelkit modification the 737-200 can use unimproved or unpaved landing strips, such as gravel runways, that other similarly-sized jet aircraft cannot. Gravel-kitted 737-200 Combis are currently used by Canadian North, First Air, Air Inuit, Nolinor and Air North in northern Canada. For many years, Alaska Airlines made use of gravel-kitted 737-200s to serve Alaska's many unimproved runways across the state.[122]

Nineteen 737-200s were used to train aircraft navigators for the U.S. Air Force, designated T-43. Some were modified into CT-43s, which are used to transport passengers, and one was modified as the NT-43A Radar Test Bed. The first was delivered on July 31, 1973 and the last on July 19, 1974. The Indonesian Air Force ordered three modified 737-200s, designated Boeing 737-2x9 Surveiller. They were used as Maritime reconnaissance (MPA)/transport aircraft, fitted with SLAMMAR (Side-looking Multi-mission Airborne Radar). The aircraft were delivered between May 1982 and October 1983.[123]

After 40 years the final 737-200 aircraft in the U.S. flying scheduled passenger service were phased out in March 2008, with the last flights of Aloha Airlines.[124] The variant still sees regular service through North American charter operators such as Sierra Pacific.[125]

737 Classic series

The Boeing 737 Classic is the name given to the -300/-400/-500 series of the Boeing 737 after the introduction of the -600/700/800/900 series. The Classic series was originally introduced as the 'new generation' of the 737.[126] Produced from 1984 to 2000, 1,988 aircraft were delivered.[50]

737 Next Generation

By the early 1990s, it became clear that the new Airbus A320 was a serious threat to Boeing's market share, as Airbus won previously loyal 737 customers such as Lufthansa and United Airlines. In November 1993, Boeing's board of directors authorized the Next Generation program to replace the 737 Classic series. The -600, -700, -800, and -900 series were planned.[127] After engineering trade studies and discussions with major 737 customers, Boeing proceeded to launch the 737 Next Generation series. Variants include the P-8 Poseidon.

737 MAX

In 2011, Boeing announced the 737 MAX program. Boeing will be offering three variants-the 737 MAX 7, 737 MAX 8 and the 737 MAX 9. These aircraft will replace the 737-700, 737-800 and 737-900ER, respectively. The main changes are the use of CFM International LEAP-1B engines, the addition of fly-by-wire control to the spoilers, and the lengthening of the nose landing gear. Deliveries are scheduled to begin in 2017.[128][129] Southwest Airlines announced on December 13, 2011 that it would order the 737 MAX and became the launch customer.[130] Ryanair, Norwegian Air Shuttle, and others have also placed firm orders for 737 MAX aircraft.[131]

Boeing Business Jet (BBJ)

The Boeing Business Jet is a customized version of the 737. Plans for a business jet version of the 737 are not new. In the late 1980s, Boeing marketed the 77-33 jet, a business jet version of the 737-300.[132] The name was short-lived. After the introduction of the next generation series, Boeing introduced the Boeing Business Jet (BBJ) series. The BBJ1 was similar in dimensions to the 737-700 but had additional features, including stronger wings and landing gear from the 737-800, and had increased range (through the use of extra fuel tanks) over the other 737 models. The first BBJ rolled out on August 11, 1998 and flew for the first time on September 4.[133]

On October 11, 1999 Boeing launched the BBJ2. Based on the 737-800, it is 5.84 meters (19 ft 2 in) longer than the BBJ, with 25% more cabin space and twice the baggage space, but has slightly reduced range. It is also fitted with auxiliary belly fuel tanks and winglets. The first BBJ2 was delivered on 28 February 2001.[133]

Boeing's BBJ3 is based on the 737-900ER. The BBJ3 has 1,120 square feet (104 m2) of floor space, 35% more interior space, and 89% more luggage space than the BBJ2. It has an auxiliary fuel system, giving it a range of up to 4,725 nautical miles (8,751 km), and a Head-up display. Boeing completed the first example in August 2008. This aircraft's cabin is pressurized to a simulated 6,500-foot (2,000 m) altitude.[134][135]

Freighter

Boeing is studying plans to offer passenger to freighter conversion for the 737-800. Boeing has signed an agreement with Chinese YTO Airlines to provide the airline with 737-800 Boeing Converted Freighters (BCFs) pending a planned program launch.[136]

Operators

The 737 is operated by more than 500 airlines, flying to 1,200 destinations in 190 countries. With over 10,000 aircraft ordered, over 7,000 delivered, and over 4,500 still in service, at any given time there are on average 1,250 airborne worldwide. On average, somewhere in the world, a 737 took off or landed every five seconds in 2006.[5] Since entering service in 1968, the 737 has carried over 12 billion passengers over 74 billion miles (120 billion km; 65 billion nm), and has accumulated more than 296 million hours in the air. The 737 represents more than 25% of the worldwide fleet of large commercial jet airliners.[5][137]

Civilian

As of August 2013, 140 Boeing 737-200 aircraft were in civilian service.[138]

Military

Many countries operate the 737 passenger, BBJ, and cargo variants in government or military applications.[139] Users with 737s include:

Competition

The Boeing 737 Classics and the Boeing 737 Next Generation have faced main challenges from the Airbus A320 family introduced in 1988, which was developed to compete also with the McDonnell Douglas MD-80/90 series and the Boeing 717 (formerly named McDonnell Douglas MD-95).

Boeing has shipped 9,213 aircraft of the 737 family since late 1967,[1] with 7,707 of those deliveries since March 1, 1988,[140] and has a further 4,350 on firm order as of September 2016.[1] In comparison, Airbus has delivered 7,256 A320 series aircraft since their certification/first delivery in early 1988, with another 5,520 on firm order (as of September 2016).[141] Template:Line chart Template:Line chart

Orders and deliveries

Total production

In total, 9,247 units of the Boeing 737 have been built and delivered as of October 31, 2016.[1]

| Total Orders | Total Deliveries | Unfilled | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13,568 | 9,247 | 4,321 | 402 | 495 | 485 | 440 | 415 | 372 | 376 | 372 | 290 | 330 |

| Year | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | 1996 | 1995 | 1994 | 1993 | 1992 | 1991 | 1990 | 1989 | 1988 | 1987 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deliveries | 302 | 212 | 202 | 173 | 223 | 299 | 281 | 320 | 281 | 135 | 76 | 89 | 121 | 152 | 218 | 215 | 174 | 146 | 165 | 161 |

| Year | 1986 | 1985 | 1984 | 1983 | 1982 | 1981 | 1980 | 1979 | 1978 | 1977 | 1976 | 1975 | 1974 | 1973 | 1972 | 1971 | 1970 | 1969 | 1968 | 1967 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deliveries | 141 | 115 | 67 | 83 | 95 | 108 | 92 | 77 | 40 | 25 | 41 | 51 | 55 | 23 | 22 | 29 | 37 | 114 | 105 | 4 |

Units by generation

As of 31 October 2016[update], 13,568 units of the Boeing 737 have been ordered, with 4,321 units still to be delivered.[1] Units built by model type for 737 Original, Classic, Next Generation, and Boeing Business Jet families are as follows:

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Data from Boeing.com through end of October 2016[1]

Accidents and incidents

For incidents involving other 737 variants see Boeing 737 Classic incidents and Boeing 737 Next Generation incidents.

As of October 2015, a total of 368 aviation accidents and incidents involving all 737 aircraft have occurred,[145] including 184 hull-loss accidents resulting in a total of 4,862 fatalities.[146] The 737 has also been in 111 hijackings involving 325 fatalities.[147]

An analysis by Boeing on commercial jet airplane accidents in the period 1959–2013 showed that the original series had a hull loss rate of 1.75 per million departures versus 0.54 for the classic series and 0.27 for the Next Generation series.[148]

- Notable accidents and incidents involving 737-100, and -200 aircraft

- July 19, 1970 – United Airlines Flight 611, a new Boeing 737-200 (registration N9005U "City of Bristol") was damaged beyond economical repair after an aborted take off at Philadelphia International Airport. During take off, a loud "bang" was heard, and the aircraft veered right. The captain aborted the take off, and the aircraft ran off the end of the runway, stopping 1634 feet past its end, in a field. There were no fatalities. This was the first non-fatal incident involving a 737.[149]

- July 5, 1972 – Pacific Southwest Airlines Flight 710 was hijacked by two men demanding $800,000 and to be taken to the Soviet Union. In San Francisco, the plane was stormed and the two hijackers were killed along with one passenger.[150]

- December 8, 1972 – United Airlines Flight 553, a 737-200 (registration N9031U) crashed while attempting to land at Chicago Midway International Airport. Two people on the ground and 43 of the 61 passengers and crew on board were killed. This was the first fatal incident involving a 737.[151]

- May 31, 1973 – Indian Airlines Flight 440, a 737-200, crashed while on approach to Palam International Airport in New Delhi, India. Of the 65 passengers and crew on board, 48 were killed.[152]

- December 17, 1973 – In the wake of the events surrounding Pan Am Flight 110, a parked Lufthansa Boeing 737–100 (registered D-ABEY) was hijacked at Leonardo da Vinci-Fiumicino Airport in Rome. Two pilots and two flight attendants were on board preparing the aircraft for departure to Munich when five Palestinian terrorists entered the aircraft with ten Italian hostages taken from the airport. The crew were then forced to fly the aircraft to Athens and then on to several other airports, until the ordeal ended at Kuwait International Airport the next day, where the hijackers surrendered.[153][154]

- March 31, 1975 – Western Airlines Flight 470, a 737-200 (registration N4527W) overshot a runway contaminated with snow at Casper/Natrona County International Airport in Casper, Wyoming. Four of the 99 aboard were injured, and the aircraft was damaged beyond repair.

- October 13, 1977 – Lufthansa Flight 181 was hijacked by four Palestinians, demanded the release of seven Red Army Faction members in German prisons and $15,000,000. The captain was fatally shot. On October 17, GSG-9 stormed the plane and killed 3 of the hijackers and captured the other.[155]

- December 4, 1977 – Malaysian Airline System Flight 653, a 737-200 (registration 9M-MBD) crashed following a phugoid oscillation that saw the aircraft diving into a swamp after both its pilots were shot following a hijacking. The crash happened in the Southern Malaysian state of Johor. A total of 93 passengers and seven crew were killed, including Malaysian Agricultural Minister, Dato' Ali Haji Ahmad; Public Works Department Head, Dato' Mahfuz Khalid; and Cuban Ambassador to Japan, Mario García Incháustegui.

- February 11, 1978 – Pacific Western Airlines Flight 314, a 737-200, crashed while attempting to land at Cranbrook Airport, British Columbia, Canada. The aircraft crashed after thrust reversers did not fully stow following a go-around that was executed in order to avoid a snowplow. The crash killed four of the crew members and 38 of the 44 passengers.[156]

- April 26, 1979 – An Indian Airlines was damaged by a bomb in the forward lavatory. The plane made a flapless landing in Chennai, India.[157]

- November 4, 1980 – TAAG Angola Airlines 737-200 registration D2-TAA, that landed short of the runway at Benguela Airport, slid some 900 m following the collapse of the gear; a fire broke out on the right wing but there were no reported fatalities. The aircraft caught fire during recovery operations on next day and was written off.[158][159]

- May 2, 1981 – Aer Lingus Flight 164, a 737-200, which was hijacked and en route from Dublin Airport, Ireland to London Heathrow Airport, UK. While on approach to Heathrow, about five minutes before the flight was due to land, a 55-year-old Australian man named Laurence James Downey went into the toilet and doused himself in petrol.[160] He then went to the cockpit and demanded that the plane continue on to Le Touquet – Côte d'Opale Airport in France, and refuel there for a flight to Tehran, Iran.[161][162] Upon landing at Le Touquet, Downey further demanded the publication in the Irish press of a nine-page statement which he had the Captain throw from the cockpit window.[163] After an eight-hour standoff (during which time Downey released 11 of his 112 hostages),[164] French special forces stormed the plane and apprehended Downey. No shots were fired and nobody was injured.[165]

- August 22, 1981 – Far Eastern Air Transport Flight 103, a 737-200 (registration B-2603) broke apart in mid-air and crashed 14 minutes after taking off from Taipei Songshan Airport in Taiwan. All 6 crew and 104 passengers were killed, including Japanese TV screenwriter Kuniko Mukoda.[166]

- January 13, 1982 – Air Florida Flight 90, a 737-200 crashed in a severe snowstorm, immediately after takeoff from Washington National Airport, hitting the 14th Street Bridge and fell into the ice-covered Potomac River in Washington, D.C.. All but five of the 74 passengers and five crew members died; four motorists on the bridge were also killed.[167]

- May 25, 1982 – VASP 737-2A1 registration PP-SMY, on landing procedures at Brasília during rain, made a hard landing with nose gear first. The gear collapsed and the aircraft skidded off the runway breaking in two. Two passengers out of 118 occupants died.[168]

- August 26, 1982 – Southwest Air Lines Flight 611, a 737-200 (registration JA8444) overran the runway at Ishigaki Airport in Japan and was destroyed. There were no fatalities but some were injured during the emergency evacuation.[169]

- March 27, 1983 – LAM Mozambique Airlines 737-200 registration C9-BAB Undercarriage failure after landing some 400 metres (1,300 ft) short of the runway at Quelimane Airport. There were no fatalities.[170]

- July 11, 1983 – TAME 737-2V2 Advanced, registration HC-BIG, crashed while attempting to land at Mariscal Lamar Airport, killing all 111 passengers and eight crew on board. The cause of the crash was a CFIT (Controlled Flight Into Terrain) as a cause of the pilot's inexperience with the aircraft. It remains the deadliest aviation accident in Ecuadorean history.[171][172][173] after a radio station reported witnesses to a mid-air explosion.[174]

- September 23, 1983 – Gulf Air Flight 771, a 737-200 (registration A40-BK) experienced an attempted terrorist bomb exploded in the baggage compartment, stalled and crashed in the desert near Mina Jebel Ali between Abu Dhabi and Dubai in the United Arab Emirates. All 5 crew and 107 passengers were killed, many of whom were Pakistani citizens.[175][176]

- November 8, 1983 – TAAG Angola Airlines Flight 462 stalled and crashed shortly after taking off from Lubango Mukanka Airport in Angola resulting of the deaths of all its 130 occupants (126 passengers and 4 crew) on board.[177][178]

- February 9, 1984 – TAAG Angola Airlines 737-200 registration D2-TBV, that departed from Albano Machado Airport operating a scheduled passenger service, suffered hydraulic problems following an explosion in the rear of the aircraft and returned to the airport of departure for an emergency landing. The plane touched down fast and overran the runway.[179]

- March 22, 1984 – Pacific Western Airlines Flight 501, a 737-200 regularly scheduled flight that caught fire in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Five people were seriously injured and 22 suffered minor injuries, but no-one was killed.

- August 30, 1984 – Cameroon Airlines Flight 786, a 737-200 (registration TJ-CBD) caught fire as the aircraft was taxiing out for takeoff for Douala International Airport in Douala, Littoral Province, Cameroon. All but two of 109 passengers and two crew were reported to have survived.[180]

- June 21, 1985 – Braathens SAFE Flight 139, a 737-200 that was hijacked by a 24-year-old man, Stein Arvid Huseby at the Trondheim Airport in Værnes, Norway. His demands were to make a political statement and talk to Prime Minister Kåre Willoch and Minister of Justice Mona Røkke. The plane landed at Oslo Airport in Fornebu and was surrounded by the police. After one hour, Huseby released 70 hostages in exchange for having the aircraft being moved closer to the terminal building. Thirty minutes later, Huseby released the remaining passengers. He drank throughout the incident, and after he consumed the plane's beer supply, he surrendered his weapon in exchange for more beer. The plane was immediately stormed and Huseby arrested.

- August 22, 1985 – British Airtours Flight 28M, a 737-200, caught fire after an aborted takeoff at Manchester Airport, UK, after a crack in one of the combustors of the left Pratt & Whitney JT8D-15 engine. Of the 136 passengers and crew on board, 56 died, most due to toxic smoke inhalation. Research following the accident investigation led to many innovations in air safety, including a redesign of the 737's galley area.[181]

- January 28, 1986 – VASP 737-2A1 registration PP-SME, tried to take-off from a taxiway at São Paulo-Guarulhos Airport. The take-off was aborted, but the aircraft overran, collided with a dyke and broke in two. The weather was foggy. There was one fatality.[182]

- October 15, 1986 – Iran Air 737-200 registration EP-IRG was attacked by Iraqi aircraft. Passengers were disembarking at the time of the attack. According to Iranian authorities a number of C-130 Hercules aircraft were also destroyed. Three occupants were killed.[183]

- December 25, 1986 – Iraqi Airways Flight 163, a 737-200 that was hijacked and crashed, catching fire in Arar near Saudi Arabia. There were 106 people on board, and 60 passengers and 3 crew members died.

- August 4, 1987 – LAN Chile 737-200 registration CC-CHJ, operated in a flight, while on the approach at El Loa Airport, Chile, landed short of the displaced threshold of runway 27. The nosegear collapsed and the aircraft broke in two. A fire broke out 30 minutes later and destroyed the aircraft. The threshold was displaced by 880m due to construction work. There was one fatality.[184]

- August 31, 1987 – Thai Airways Flight 365, a 737-200 (registration HS-TBC) crashed into the sea off Ko Phuket, Thailand. A total of 74 passengers and 9 crew on board lost their lives.[185]

- January 2, 1988 – Condor Flight 3782, a charter operated 737-200, crashed in Serefsihar near Izmir, Turkey, due to ILS problems. All 11 Passengers and 5 crew were killed in the accident.

- April 28, 1988 – Aloha Airlines Flight 243, a 737-200, suffered extensive damage after an explosive decompression at 24,000 feet (7,300 m), but was able to land safely at Kahului Airport on Maui with one fatality. A flight attendant, who was not in restraints at the moment of decompression, was blown out of the aircraft over the ocean and was never found.

- September 15, 1988 – Ethiopian Airlines Flight 604, a 737-200, suffered a multiple bird strike while taking off from Bahir Dar Airport. Both engines failed and the airliner crashed and caught fire while trying to return to the airport. Thirty-five of 98 passengers died while all six crew members survived.[186]

- September 26, 1988 – Aerolineas Argentinas 737-200 registration LV-LIU operating Flight 648 departed in Jorge Newbery Airport in Buenos Aires, Argentina and made an emergency landing at Ushuaia Airport in Ushuaia, Argentina. There were no fatalities.[187]

- February 9, 1989 – LAM Mozambique Airlines 737-200 registration C9-BAD overran the runway while making an emergency landing at Lichinga Airport. There were no fatalities.[188][189]

- September 3, 1989 – Varig 737-241 registration PP-VMK operating Flight 254 flying from São Paulo-Guarulhos to Belém-Val de Cans with intermediate stops, crashed near São José do Xingu while on the last leg of the flight between Marabá and Belém due to a pilot navigational error, which led to fuel exhaustion and a subsequent belly landing into the jungle, 450 miles (724 km) southwest of Marabá. Out of 54 occupants, there were 13 fatalities, all of them passengers. The survivors were discovered two days later.[190][191]

- October 2, 1990 – The 1990 Guangzhou Baiyun airport collisions were the result of the hijacking of Xiamen Airlines Flight 8301, a 737-200 (registration B-2510). Whilst attempting to land at Guangzhou Baiyun it struck two other airplanes. The hijacked aircraft struck a parked China Southwest Airlines Boeing 707 first, inflicting only minor damage, but then collided with China Southern Airlines Flight 2812, a Boeing 757-200 waiting for takeoff, and flipped on its back. A total of 128 people were killed, including 7 of 9 crew members and 75 of 93 passengers on Flight 8301 and 46 of 110 passengers on Flight 2812.

- March 3, 1991 – United Airlines Flight 585, a 737-291 carrying 20 passengers and five crew members, lost control after a rudder malfunction and crashed outside of Colorado Springs Municipal Airport, killing everyone on board.

- June 6, 1992 – Copa Airlines Flight 201, a 737-204 Advanced registration HP-1205CMP en route from Tocumen International Airport in Panama City, Panama to Alfonso Bonilla Aragón International Airport in Cali, Colombia crashed into the Darien Gap 29 minutes after taking-off from Tocumen International Airport. All 47 on board (40 passengers and 7 crew) were killed in the crash.[192]

- June 22, 1992 – VASP cargo 737-2A1C registration PP-SND en route from Rio Branco to Cruzeiro do Sul crashed in the jungle while on arrival procedures to Cruzeiro do Sul. The crew of two and one passenger died.[193]

- December 21, 1994 – Air Algérie Flight 702P, a 737-200C on behalf of Phoenix Aviation crashed in Coventry, England, UK. All 5 crew members were killed.

- August 9, 1995 – Aviateca Flight 901, a 737-200 (registration N125GU) crashed on approach to the El Salvador International Airport in San Salvador, El Salvador. 58 of 65 occupants were killed.[194]

- November 13, 1995 – Nigeria Airways Flight 357, a 737-2F9 (5N-AUA), suffered a runway overrun at Kaduna Airport in Nigeria. All 14 crew members survived, but 11 of the 124 passengers were killed.[195]

- December 3, 1995 – Cameroon Airlines Flight 3701, a 737-200 (registration TJ-CBE) crashed after it lost control and on approach to the Douala International Airport in Douala, Littoral Province, Cameroon. 71 passengers and crew lost their lives, but there were 5 survivors.[196][197]

- February 29, 1996 – Faucett Flight 251, a 737-200 (registration OB-1451) crashed on approach to Rodríguez Ballón International Airport in Arequipa, Peru. A total of 117 passengers and 6 crew on board lost their lives.[198]

- April 3, 1996 – United States Air Force CT-43A (a modified 737-200 and serial number 73-1149) (86th Airlift Wing, based at Ramstein Air Base, Germany) operating in a VIP transport flight crashed on approach to Dubrovnik Airport in Dubrovnik, Croatia while on an official trade mission. All 5 crew and 30 passengers were killed, including U.S. Secretary of Commerce Ron Brown and The New York Times Frankfurt Bureau chief Nathaniel C. Nash. Air Force Technical Sergeant Shelly Kelly survived the crash, but died three hours after the crash from an injury sustained in an ambulance.[199][200]

- June 9, 1996 – Eastwind Airlines Flight 517, a 737-2H5 on a scheduled domestic passenger flight between Trenton-Mercer Airport in Trenton, New Jersey and Richmond International Airport in Richmond, Virginia, the flight lost rudder control but was able to land successfully. There were no fatalities but one flight attendant suffered minor injuries, among 48 passengers and 4 crew members surviving.[201]

- February 14, 1997 – Varig 737-241, registration PP-CJO operating flight 265, flying from Marabá to Carajás, while on touchdown procedures at Carajás during a thunderstorm, veered off the right side of the runway after its right main landing gear collapsed rearwards. The aircraft crashed into a forest. One crew member was killed.[202]

- April 12, 1998 – Orient Eagle Airways Flight 717, a 737-200 Overran the runway at a speed of 80 knots after a heavy landing on a wet runway at Almaty International Airport in Kazakhstan. The right main gear collapsed. There were no fatalities.

- May 5, 1998 – Occidental Petroleum 737-200 (FAP-351) leased from Peruvian Air Force, operating a charter flight from Coronel FAP Francisco Secada Vignetta International Airport in Iquitos, Peru, which crashed in rainy weather whilst on approach to Alférez FAP Alfredo Vladimir Sara Bauer Airport in Andoas, Peru. There were 75 fatalities, only eleven passengers and two crew members survived.

- May 10, 1999 – Mexican Air Force 737-247 was on a training flight when it overran the runway while making an emergency landing at Loma Bonita Air Base, Mexico. The nosegear collapsed. Grass near the aircraft caught fire causing the airplane to burn out. There were no fatalities.

- August 31, 1999 – LAPA Flight 3142, a 737-200, crashed while attempting to take off from the Jorge Newbery Airport in Buenos Aires en route to Córdoba, Argentina. The crash resulted in 65 fatalities.

- April 19, 2000 – Air Philippines Flight 541, a 737-200 flying from Ninoy Aquino International Airport in Manila crashed on approach to Francisco Bangoy International Airport in Davao City, Philippines. All 124 passengers and 7 crew members on board were killed.[203][204]

- December 26, 2002 – TAAG Angola Airlines 737-200 registration D2-TDB and operating flight 572 that had departed from Windhoek Hosea Kutako International Airport bound for Luanda, was involved in a mid-air collision over Namibian airspace with a propeller-driven light aircraft Cessna 404 registration V5-WAA, that took off from Windhoek Eros Airport in Namibia.[205][206]

- March 6, 2003 – Air Algérie Flight 6289, a 737-200 crashed shortly after taking off from Tamanrasset, Algeria. All 97 passengers and 6 crew on board perished with the exception of a 28-year-old soldier, Youcef Djillali.[207]

- July 8, 2003 – Sudan Airways Flight 139, a 737-200C (registration ST-AFK) stalled and crashed in Port Sudan, Sudan resulting of the deaths of all its 117 occupants (106 passengers and 11 crew members) on board.

- February 3, 2005 – Kam Air Flight 904, a 737-200 registration EX-037 crashed into the Pamir mountain in Afghanistan. All 96 passengers and 8 crew members on board lost their lives.

- August 23, 2005 – TANS Perú Flight 204, a 737-200 crashed on approach to Pucallpa Airport in Peru. 40 of 98 occupants lost their lives, while 58 others survived.[208][209]

- September 5, 2005 – Mandala Airlines Flight 091, a 737-200, crashed in a densely populated neighborhood of Medan, North Sumatra, Indonesia, because trying to take off with incorrect flap settings. It was carrying 117 on board (of whom 100 passengers and 5 crew) as well as 49 people on the ground were killed.[210]

- October 22, 2005 – Bellview Airlines Flight 210, a 737-200 (registration 5N-BFN) stalled and crashed shortly after taking off from Murtala Mohammed Airport in Lagos, Nigeria en route to the Nnamdi Azikiwe International Airport for the Nigerian capital Abuja, resulting of the deaths of all its 117 occupants (111 passengers and 6 crew members) on board.

- October 29, 2006 – ADC Airlines Flight 53, a 737-200 crashed during a storm shortly after takeoff from Nnamdi Azikiwe International Airport in Abuja, Nigeria. All but seven of the 104 passengers and crew were reported to have been killed.[211]

- January 24, 2007 – Air West Flight 612, a 737-200 was hijacked by a 26-year-old man, Mohamed Abdu Altif, who entered the cockpit of the aircraft approximately half an hour after takeoff from Khartoum International Airport in Sudan. The aircraft landed safely at the N'Djamena International Airport in Chad where the hijacker surrendered. All 95 passengers and 8 crew on board survived.

- June 28, 2007 – TAAG Angola Airlines 737-200 crashed in northern Angola.

- August 24, 2008, Iran Aseman Airlines Flight 6895, a 737-200 from Itek Air wet leased to Iran Aseman Airlines crashed while attempting an emergency landing on return, ten minutes after departure from Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. The airliner was flying to Tehran, Iran. Out of 83 passengers and seven crew, there were 22 survivors.

- August 30, 2008 – ConViasa 737-200 Advanced registration YV-102T operating a ferry flight from Simón Bolívar International Airport in Maiquetía, Venezuela stalled and crashed into the Illiniza Volcano, Ecuador. One passenger and both pilots died.[212]

- March 1, 2010 – Air Tanzania Flight 100, a 737-200 (5H-MVZ) sustained substantial damage when it departed the runway on landing at Mwanza Airport and the nose gear collapsed. Damage was also caused to an engine.[213]

- August 20, 2010 – Chanchangi Airlines Flight 334, a 737-200 (5N-BIF), struck the localizer antenna and landed short of the runway at Kaduna Airport. Several passengers were slightly injured and the aircraft was substantially damaged. Chanchangi Airlines again suspended operations following the accident.[214]

- August 20, 2011 – First Air Flight 6560, a 737-200, crashed near Resolute Bay in the Canadian territory of Nunavut. Of the 15 people on board, there were three survivors.[215]

- April 20, 2012 – Bhoja Air Flight 213, a 737-200, crashed in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. All 127 passengers and crew on board were killed.[216]

Aircraft on display

- 737-130 N515NA is on display in NASA markings at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington. It was the first 737 built.[217]

- 737-222 N9065U is partially preserved at the Hiller Aviation Museum in San Carlos, California.[218]

- 737-201 N213US is partially preserved at the Museum of Flight in Seattle in US Air markings.[219]

- 737-2H4 N29SW, formerly operated by Ryan International Airlines, is on display at the Kansas Aviation Museum in Wichita, Kansas.[220]

- 737-2H4 N86SW is partially preserved as a restaurant in Walnut Ridge, Arkansas.[221]

- 737-2Z6 L-11-1/26 of the Royal Thai Air Force is displayed at Don Muang Airport, Bangkok.[222]

- 737-290C N740AS, formerly of Alaska Airlines, is preserved at the Alaska Aviation Museum in Anchorage, Alaska.[223]

- 737-281 LV-WTX is displayed at the National Museum of Aeronautics in Morón, Argentina.[224]

- 737-2H4(A) C-GWJT is used by the British Columbia Institute of Technology Aerospace Technology Campus in Richmond, British Columbia, Canada, for ground instructional training and static public display. The aircraft was donated by WestJet and bears it livery. It was towed from the adjacent YVR Vancouver International Airport via the public Russ Baker Way road, which was closed to traffic and had light standards temporarily removed. [225]

- 737-219/Adv ZS-SMD is preserved at the South African Airways Museum in Germiston, South Africa.[226]

- 737-3H4 N300SW is on display in its Southwest Airlines livery at the Frontiers of Flight Museum in Dallas, Texas.[227]

- 737-3Q8 B-2921 is on display outside at the Pima Air & Space Museum in China Southern Airlines markings.[228]

Specifications

| 737-100 | 737-200 | 737-200 Advanced | 737 Classic (-300/-400/-500) | 737 Next Generation (-600/-700/-800/-900ER) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cockpit crew | Two | ||||

| Seating capacity | 124 (maximum) 85 (2-class, typical) |

136 (maximum) 97 (2-class, typical) |

140 - 188 (maximum) 108 - 146 (2-class, typical) |

130 - 220[229] (maximum) 108 - 177 (2-class, typical) | |

| Length | 94 ft (28.65 m) | 100 ft 2 in (30.53 m) | 102–120 ft (31–37 m) | 102–138 ft (31–42 m) | |

| Wingspan | 93 ft (28.35 m) | 94 ft 9 in (28.88 m) | 112 ft 7 in (34.32 m) 117 ft 5 in (35.79 m) with winglets | ||

| Wing area | 102.0 m2 (1,098 sq ft) | 105.4 m2 (1,135 sq ft) | 124.58 m2 (1,341.0 sq ft) | ||

| Wing sweepback | 25 degrees | 25.02 degrees | |||

| Overall height | 36 ft 10 in (11.23 m) | 36 ft 4 in (11.07 m) | 41 ft 3 in (12.57 m) | ||

| Maximum cabin width | 11 ft 7 in (3.53 m) | ||||

| Fuselage width | 12 ft 4 in (3.76 m) | ||||

| Cargo capacity | 650 cu ft (18.4 m3) | 875 cu ft (24.8 m3) | 822–1,373 cu ft (23.3–38.9 m3) | 756–1,835 cu ft (21.4–52.0 m3) | |

| Operating empty weight, typical | 62,000 lb (28,100 kg) | 69,700 lb (31,600 kg) | 69,800 lb (31,700 kg) | 69,000–74,170 lb (31,300–33,600 kg) | 80,200–98,500 lb (36,400–44,700 kg) |

| Maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) | 111,000 lb (50,300 kg) | 115,500 lb (52,400 kg) | 128,100 lb (58,100 kg) | 138,500–150,000 lb (62,800–68,000 kg) | 144,500–187,700 lb (65,500–85,100 kg) |

| Cruising speed | Mach 0.74 (485 mph, 780 km/h) | Mach 0.78 (511 mph, 823 km/h) | |||

| Maximum speed | Mach 0.82 (544 mph, 877 km/h) | ||||

| Takeoff field length (MTOW, SL, ISA) | 6,646 ft (2,026 m) | - | - | 7,550–8,500 ft (2,300–2,590 m) | 5,249–9,843 ft (1,600–3,000 m) |

| Maximum range, fully loaded | 1,540 nmi (2,850 km; 1,770 mi) | 1,900–2,300 nmi (3,500–4,300 km; 2,200–2,600 mi) | 2,270–2,400 nmi (4,200–4,440 km; 2,610–2,760 mi) | 3,050–5,510 nmi (5,650–10,200 km; 3,510–6,340 mi) | |

| Maximum fuel capacity | 4,720 US gal (17,900 L; 3,930 imp gal) | 4,780 US gal (18,100 L; 3,980 imp gal) | 5,160 US gal (19,500 L; 4,300 imp gal) | 5,311 US gal (20,100 L; 4,422 imp gal) | 6,875 US gal (26,020 L; 5,725 imp gal) |

| Service ceiling | 35,000 ft (10,700 m) | 37,000 ft (11,300 m) | 41,000 ft (12,500 m) | ||

| Engines (×2) | Pratt & Whitney JT8D | CFM International CFM56-3 series | CFM International CFM56-7 series | ||

| Thrust (×2) | 14,500 lbf (64 kN) | 14,500–17,400 lbf (64–77 kN) | 20,000–23,500 lbf (89–105 kN) | 19,500–27,300 lbf (87–121 kN) | |

Sources: Boeing 737 specifications,[230] 737 Airport Planning Report,[231] b737.org.uk site.[232]

| ICAO code[233] | Model(s) |

|---|---|

| B731 | 737-100 |

| B732 | 737-200/CT-43/VC-96 |

| B733 | 737-300 |

| B734 | 737-400 |

| B735 | 737-500 |

| B736 | 737-600 |

| B737 | 737-700/BBJ/C-40 |

| B738 | 737-800/BBJ2 |

| B739 | 737-900/BBJ3 |

See also

Related development

- Boeing 737 Classic

- Boeing 737 Next Generation

- Boeing 737 MAX

- Boeing T-43

- Boeing Business Jet

- Boeing 737 AEW&C

- Boeing C-40 Clipper

- Boeing P-8 Poseidon

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Airbus A320 family

- Boeing 717

- Bombardier CSeries

- Comac C919

- Dassault Mercure

- Sukhoi Superjet 100

- Embraer 195

- McDonnell Douglas DC-9

- McDonnell Douglas MD-80

- McDonnell Douglas MD-90

- Irkut MC-21

- Tupolev Tu-154M

- Tupolev Tu-204

- Yakovlev Yak-42D

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Boeing Commercial Airplanes – Orders and Deliveries – 737 Model Summary". boeing.com. Boeing. September 30, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Kingsley-Jones, Max. "6,000 and counting for Boeing’s popular little twinjet." Flight International, Reed Business Information, April 22, 2009. Retrieved: April 22, 2009.

- ^ "The Boeing 737-100/200." Airliners.net, Demand Media, Inc. Retrieved: April 22, 2009.

- ^ a b "Airbus A320 Aircraft Facts, Dates and History." Archived January 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Flightlevel350.com. Retrieved: May 12, 2010.

- ^ a b c "The 737 Story: Little Wonder." flightglobal.com. February 7, 2006. Retrieved: January 7, 2008.

- ^ a b "Transport News: Boeing Plans Jet." The New York Times, July 17, 1964. Retrieved: February 26, 2008.

- ^ Endres 2001, p. 122

- ^ Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 12

- ^ a b c Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 13

- ^ a b "German Airline Buys 21 Boeing Short-Range Jets." The Washington Post, February 20, 1965. Retrieved: February 26, 2008.

- ^ a b c Wallace, J. "Boeing delivers its 5,000th 737." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 13, 2006. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 17

- ^ Redding & Yenne 1997, p. 182

- ^ Sutter 2006, pp. 76–78.

- ^ Olason, M.L. and Norton, D.A. "Aerodynamic Philosophy of the Boeing 737", AIAA paper 65-739, presented at the AIAA/RAeS/JSASS Aircraft Design and Technology Meeting, Los Angeles California, November 1965. Reprinted in the AIAA Journal of Aircraft, Vol.3 No.6, November/December 1966, pp.524-528.

- ^ Shaw 1999, p. 6

- ^ Gates, Dominic. "Successor to Boeing 737 likely to be built in state." Seattle Times, 30 December 2005. Retrieved: February 10, 2008.

- ^ John W. McCurry. "Spirit of Expansion". siteselection.com. Site Selection Online. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ Jon Ostrower (August 12, 2013). "Spirit AeroSystems CEO Says Boeing Exploring Increasing 737 Production". online.wsj.com. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Shaw 1999, p. 16

- ^ "Original 737 Comes Home to Celebrate 30th Anniversary". www.boeing.com. Boeing. May 2, 1997. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 20

- ^ a b "Type Certificate Data Sheet A16WE." faa.gov. Retrieved: September 3, 2010.

- ^ a b Redding & Yenne 1997, p. 183

- ^ Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 120

- ^ Endres 2001, p. 124

- ^ "Boeing 737 History". ModernAirlines.com. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Sharpe, Shaw, Mike, Robbie (2001). Boeing 737-100 and 200. MBI Publishing Company. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Powerplant - Reverse Thrust." b737.org.uk. Retrieved: November 1, 2011.

- ^ "737 Airplane Characteristics for Airport Planning" (PDF). Boeing. May 2011. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 21

- ^ Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 19

- ^ "Unpaved Strip Kit." b737.org.uk. Retrieved: February 10, 2008.

- ^ Boeing 737-2T2C/Adv "Boeing 737." airliners.net. Retrieved: February 10, 2008.

- ^ Carey, Susan (April 13, 2007). "Arctic Eagles Bid Mud Hens Farewell At Alaska Airlines". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 23

- ^ "737 Family." Boeing.com, January 5, 2008. Retrieved: April 12, 2008.

- ^ Endres 2001, p. 126

- ^ a b Brady, Chris. "History & Development of the Boeing 737 - Classics." The Boeing 737 Information Site, 1999. Retrieved: September 5, 2010.

- ^ a b c Endres 2001, p. 128

- ^ Sweetman, Bill, All mouth, Air & Space, September 2014, p.14

- ^ Garvin, Robert V. "Starting Something Big - The Commercial Emergence of GE Aircraft Engines", American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Inc. Reston, 1998, ISBN 1-56347-289-9, p. 137.

- ^ a b Shaw 1999, p. 10

- ^ Shaw 1999, pp. 12–13

- ^ Redding & Yenne 1997, p. 185

- ^ FAA Type Certificate Data Sheet http://rgl.faa.gov/Regulatory_and_Guidance_Library/rgMakeModel.nsf/0/9c59427a20b3253686257d03004d8faa/$FILE/A16WE_Rev_53.pdf

- ^ a b c d e Shaw 1999, p. 14

- ^ FAA Type Certificate Data Sheet http://rgl.faa.gov/Regulatory_and_Guidance_Library/rgMakeModel.nsf/0/9c59427a20b3253686257d03004d8faa/$FILE/A16WE_Rev_53.pdf

- ^ Shaw 1999, p. 40

- ^ a b Endres 2001, p. 129

- ^ "Boeing: Boeing 737 Facts". Boeing. September 6, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ "To Save Fuel, Airlines Find No Speck Too Small." New York Times, June 11, 2008.

- ^ "Jet Fuel Price Development". IATA. Retrieved April 10, 2015.

- ^ "UAL Cuts Could Be Omen." The Wall Street Journal, June 5, 2008, p. B3.

- ^ David Grossman (June 29, 2000). "Why Ted's demise is a boost for business travelers". usatoday30.usatoday.com. USA Today. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ^ "Airline Shares Gain Despite Losses." The Wall Street Journal, July 23, 2008, p. B3.

- ^ Endres 2001, p. 132

- ^ a b c d e Shaw 1999, p. 8

- ^ a b "About the 737 Family." The Boeing Company. Retrieved: December 20, 2007.

- ^ Endres 2001, p. 133

- ^ "About the 737 Family". www.boeing.com. Boeing. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ^ "Aero 17 - Blended Winglets". Boeing. 2009. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ Birtles 2001, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Norris & Wagner 1999, pp. 101–02.

- ^ Shaw 1999, pp. 14–15

- ^ a b c d e Kingsley-Jones, Max. "Narrow margins: Airbus and Boeing face pressue with the A-320 and 737." flightglobal.com, October 27, 2009. Retrieved: June 23, 2010.

- ^ "Boeing's 737 Turns 8,000: The Best-Selling Plane Ever Isn't Slowing". Bloomberg Business Week. April 16, 2014.

- ^ "Airbus A320 Family passes the 5,000th order mark". Airbus. January 25, 2007. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Airbus 320 Aircraft History, Information, Pictures and Facts." aviationexplorer.com.. Retrieved: September 3, 2010.

- ^ "Airbus orders and deliveries." Archived September 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Airbus. Retrieved: September 3, 2010.

- ^ Gorman, Brian. "Boeing's Continuing Climb." Motley Fool., February 1, 2007. Retrieved: May 12, 2010.

- ^ Kingsley-Jones, Max. "Boeing-Airbus 2007 orders race closes with 'diplomatic' finish." Flight Global, January 2008. Retrieved: May 12, 2010.

- ^ "Global aircraft orders, deliveries and backlog in units for Boeing vs Airbus". Interavia Business & Technology, 2002-01.

- ^ Cochennec, Yonn. "What goes up." Interavia Business & Technology, February 2003. Retrieved: May 12, 2010.

- ^ Sutton, Oliver. "Any advance on ten percent?" Interavia Business & Technology, February 2001. Retrieved: May 12, 2010.

- ^ "Boeing 737: Das meistverkaufte Flugzeug der Welt" (in German). Rhein-Zeitung, January 3, 2004. via Agence France-Presse. Retrieved: May 12, 2010.

- ^ Robertson, David. "Boeing gets ready for all-new 737." The Times, March 12, 2007. Retrieved: April 22, 2010.

- ^ Anderson & Eberhardt 2009, p. 61

- ^ O’Sullivan, Matt. "Boeing shelves plans for 737 replacement." The Sydney Morning Herald, January 2, 2009. Retrieved: April 22, 2010. Quote: Boeing will stick with the 737, the world's most widely flown aircraft.

- ^ "Boeing airliner deliveries rise 11%." Chicago Tribune, January 4, 2008. Retrieved: April 22, 2010.

- ^ Layne, Rachel. "Bombardier’s Win May Prod Airbus, Boeing to Upgrade Engines." BusinessWeek, February 26, 2010. Retrieved: April 22, 2010.

- ^ Rahn, Kim. "B737: Best-Selling Aircraft in the World." Korea Times. Retrieved: April 22, 2010.

- ^ "Boeing 737 Aircraft Profile." Flight Global. Retrieved: April 22, 2010. Quote: the best selling commercial airliner in history.

- ^ Jiang, Steven. "Jetset: 'Tianjin Takes Off'." The Beijinger. Retrieved: April 22, 2010. Quote: A320, the workhorse of many airlines and the second best-selling jetliner family of all time (after Boeing’s venerable B737).

- ^ "737 tops 10,000 orders" Boeing.com, July 12, 2012. Retrieved: July 20, 2012.

- ^ Anselmo, Joe (March 2, 2015). "Analysts Flag Potential Airliner Glut". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Archived from the original on March 4, 2015. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.boeing.com/commercial/737ng/

- ^ "Boeing firms up 737 replacement studies by appointing team." Flight International, March 3, 2006. Retrieved: April 13, 2008.

- ^ Hamilton, Scott. "737 decision may slip to 2011: Credit Suisse." flightglobal, 2010. Retrieved: June 26, 2010.

- ^ "Boeing plans to develop new airplane to replace 737 Max by 2030". Chicago Tribune, November 5, 2014.

- ^ Guy Norris and Jens Flottau (December 12, 2014). "Boeing Revisits Past In Hunt For 737/757 Successors". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Archived from the original on December 14, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Boeing and American Airlines Agree on Order for up to 300 Airplanes". Boeing, July 20, 2011. Retrieved: November 1, 2011.

- ^ Boeing 737 MAX. NewAirplane.com

- ^ "Boeing Launches 737 New Engine Family with Commitments for 496 Airplanes from Five Airlines." boeing.mediaroom.com, August 30, 2011.

- ^ "Boeing officially launches re-engined 737." flightglobal.com, August 30, 2011.

- ^ Guy Norris (August 30, 2011). "Boeing Board Gives Go-Ahead To Re-Engined 737". aviationweek.com. Aviation Week.

- ^ Thompson, Loren. "Boeing To Build Its First Offshore Plane Factory In China As Ex-Im Bank Withers". Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ "Boeing".

- ^ Dekkers, Daniel, et al. (Project 2A2H). [home.deds.nl/~hink07/Report.pdf "Analysis Landing Gear 737-500."][dead link] Hogeschool van Amsterdam. Aviation Sudies. October 2008. Retrieved: August 20, 2011.

- ^ "Boeing Commercial Aircraft - In-Flight Fuel Jettison Capability" (PDF). Boeing. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ^ Cheung, Humphrey. "Troubled American Airlines jet lands safely at LAX." tgdaily.com, 2 September 2008. Retrieved: August 20, 2011.

- ^ Ostrower, Jon (August 30, 2011). "Boeing designates 737 MAX family". Air Transport Intelligence. Archived from the original on September 25, 2011. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ^ "Boeing's MAX, Southwest's 737". theflyingengineer. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ^ "COCKPIT WINDOWS Next-Generation 737, Classic 737, 727, 707 Airplanes" (PDF). PPG Aerospace Transparencies. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Chris Brady. The Boeing 737 Technical Guide. pp. 144–145.

- ^ Freitag, William; Schulze, Terry (2009). "Blended winglets improve performance" (PDF). Aero Magazine. pp. 9, 12. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ Faye, Robert; Laprete, Robert; Winter, Michael (2002). "Blended Winglets". Aero Magazine. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ "Split Scimitar Schedules". aviationpartnersboeing.com. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ^ "Southwest flies first 737 with new 'split scimitar' winglets". Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ^ "Design, Analysis and Multi-Objective Constrained Optimization of Multi-Winglets" (PDF). Florida International University. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ^ Volkmann, Kelsey. "Boeing gets OK for new carbon brakes." St. Louis Business Journal via bizjournals.com. Retrieved: April 22, 2010.

- ^ Wilhelm, Steve. "Mindful of rivals, Boeing keeps tinkering with its 737." Puget Sound Business Journal, August 8, 2008. Retrieved: January 21, 2011.

- ^ "Boeing Delivers First 737 with Enhanced Short Runway Package to GOL". Boeing. July 31, 2006. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- ^ a b "Check Out Boeing's Swanky New High-Tech Interior." businessinsider.com. Retrieved: November 1, 2011.

- ^ "Continental first North American carrier to offer Boeing's new Sky Interior". Flightglobal. December 29, 2010. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Continental Airlines Is First North American Carrier to Fly With Boeing's New Sky Interior". ir.unitedcontinentalholdings.com. United Airlines. December 29, 2010. Retrieved November 22, 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "MAS takes delivery of first 737-800 with Sky Interior". Flightglobal.com. November 1, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ "Wolkenlos in Seattle – an Bord des neuen Jets von TUIfly." podcastexperten, March 7, 2011. Retrieved: May 12, 2011.

- ^ Bowers 1989, p. 496

- ^ Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 41

- ^ "World Airliner Census 2015". Flightglobal Insight: 11. 2015.

- ^ "The Airplane That Never Sleeps". Boeing. July 15, 2002. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ^ Bowers 1989, pp. 498–499

- ^ "Southwest Airlines Retires Last of Founding Aircraft; Employees Help Celebrate the Boeing 737-200's Final Flight". swamedia.com. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ^ "World Airliner Census 2014". Flightglobal Insight: 12. 2014.

- ^ Shaw 1999, p. 7

- ^ "Next Generation 737 Program Milestones." The Boeing Company. Retrieved: January 22, 2008.

- ^ "Boeing Introduces 737 MAX With Launch of New Aircraft Family". August 30, 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- ^ Hepher, Tim (November 12, 2011). "AIRSHOW-Boeing 737 draft orders reach 700". Reuters. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ Burruss, Logan (November 17, 2011). "Boeing sets record with $22 billion order". CNN Money. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- ^ "Ryanair finalizes Boeing 737 MAX 200 order". Associated Press. December 2, 2014. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Endres 2001.

- ^ a b "The Boeing 737-700/800 BBJ/BBJ2." airliners.net. Retrieved: February 3, 2008.

- ^ "Boeing Business Jets Launches New Family Member". Boeing. October 16, 2006. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Boeing Completes First BBJ 3". www.wingsmagazine.com. Wings. August 14, 2008. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ Boeing to launch 737 freighter conversion program| http://www.aviationanalysis.net/2015/10/boeing-to-launch-737-freighter-conversion.html

- ^ "Boeing 737 Facts". www.boeing.com. Boeing. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ^ World Airliner Census 2013 [dead link]

- ^ "Boeing looks to sell more 737-based military jets". SeattlePi. June 9, 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ^ "Orders and Deliveries search page". Boeing. September 30, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ a b "Orders & deliveries viewer". Airbus. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "Historical Orders and Deliveries 1974–2009". Airbus S.A.S. January 2010. Archived from the original (Microsoft Excel) on December 23, 2010. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ^ "Historical Deliveries". Boeing. December 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2016.