Clindamycin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /klɪndəˈmaɪsɪn/ |

| Trade names | Cleocin, Dalacin, Clinacin, others |

| Other names | 7-chloro-lincomycin 7-chloro-7-deoxylincomycin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682399 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | by mouth, topical, IV, intravaginal |

| Drug class | Lincosamide antibiotic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 90% (by mouth) 4–5% (topical) |

| Protein binding | 95% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 2–3 hours |

| Excretion | Biliary and renal (around 20%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.038.357 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

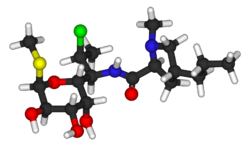

| Formula | C18H33ClN2O5S |

| Molar mass | 424.98 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Clindamycin is an antibiotic useful for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections.[2] This includes middle ear infections, bone or joint infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, strep throat, pneumonia, and endocarditis among others.[2] It can be useful against some cases of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).[3] It may also be used for acne and in addition to quinine for malaria.[2][4] It is available by mouth, intravenously, and as a cream to be applied to the skin or in the vagina.[2][4]

Common side effects include nausea, diarrhea, rash, and pain at the site of injection.[2] It increases the risk of hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile colitis about fourfold.[5] Other antibiotics may be recommended instead due to this reason.[2] It appears to be generally safe in pregnancy.[2] It is of the lincosamide class and works by blocking bacteria from making protein.[2]

Clindamycin was first made in 1966 or 1967.[6][7] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[8] It is available as a generic medication and is not very expensive.[9] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about 0.06 to 0.12 USD per pill.[10] In the United States it costs about 2.70 USD a dose.[2]

Medical uses

Clindamycin is used primarily to treat anaerobic infections caused by susceptible anaerobic bacteria, including dental infections,[11] and infections of the respiratory tract, skin, and soft tissue, and peritonitis.[12] In people with hypersensitivity to penicillins, clindamycin may be used to treat infections caused by susceptible aerobic bacteria, as well. It is also used to treat bone and joint infections, particularly those caused by Staphylococcus aureus.[12][13] Topical application of clindamycin phosphate can be used to treat mild to moderate acne.[14]

Acne

The use of clindamycin in conjunction with benzoyl peroxide is more effective in the treatment of acne than the use of either product by itself.[15][16][17]

Clindamycin and adapalene in combination are also more effective than either drug alone, although adverse effects are more frequent.[18]

Susceptible bacteria

It is most effective against infections involving the following types of organisms:

- Aerobic Gram-positive cocci, including some members of the Staphylococcus and Streptococcus (e.g. pneumococcus) genera, but not enterococci.[19]

- Anaerobic, Gram-negative rod-shaped bacteria, including some Bacteroides, Fusobacterium, and Prevotella, although resistance is increasing in Bacteroides fragilis.

Most aerobic Gram-negative bacteria (such as Pseudomonas, Legionella, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella) are resistant to clindamycin,[19][20] as are the facultative anaerobic Enterobacteriaceae.[21] A notable exception is Capnocytophaga canimorsus, for which clindamycin is a first-line drug of choice.[22]

The following represents MIC susceptibility data for a few medically significant pathogens.

- Staphylococcus aureus: 0.016 μg/ml - >256 μg/ml

- Streptococcus pneumoniae: 0.002 μg/ml - >256 μg/ml

- Streptococcus pyogenes: <0.015 μg/ml - >64 μg/ml

D-Test

When testing a Gram-positive culture for sensitivity to clindamycin, it is common to perform a "D-Test" to determine if there is a macrolide-resistant subpopulation of bacteria present. This test is necessary because some bacteria express a phenotype known as MLSB, in which susceptibility tests will indicate the bacteria are susceptible to clindamycin, but in vitro the pathogen displays inducible resistance.

To perform a D-test, an agar plate is inoculated with the bacteria in question and two drug-impregnated disks (one with erythromycin, one with clindamycin) are placed 15–20 mm apart on the plate. If the area of inhibition around the clindamycin disk is "D" shaped, the test result is positive and clindamycin should not be used due to the possibility of resistant pathogens and therapy failure. If the area of inhibition around the clindamycin disk is circular, the test result is negative and clindamycin can be used.[24]

Malaria

Given with chloroquine or quinine, clindamycin is effective and well tolerated in treating Plasmodium falciparum malaria; the latter combination is particularly useful for children, and is the treatment of choice for pregnant women who become infected in areas where resistance to chloroquine is common.[25][26] Clindamycin should not be used as an antimalarial by itself, although it appears to be very effective as such, because of its slow action.[25][26] Patient-derived isolates of Plasmodium falciparum from the Peruvian Amazon have been reported to be resistant to clindamycin as evidenced by in vitro drug susceptibility testing.[27]

Other

Clindamycin may be useful in skin and soft tissue infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA);[3] many strains of MRSA are still susceptible to clindamycin; however, in the United States spreading from the West Coast eastwards, MRSA is becoming increasingly resistant.

Clindamycin is used in cases of suspected toxic shock syndrome,[28] often in combination with a bactericidal agent such as vancomycin. The rationale for this approach is a presumed synergy between vancomycin, which causes the death of the bacteria by breakdown of the cell wall, and clindamycin, which is a powerful inhibitor of toxin synthesis. Both in vitro and in vivo studies have shown clindamycin reduces the production of exotoxins by staphylococci;[29] it may also induce changes in the surface structure of bacteria that make them more sensitive to immune system attack (opsonization and phagocytosis).[30][31]

Clindamycin has been proven to decrease the risk of premature births in women diagnosed with bacterial vaginosis during early pregnancy to about a third of the risk of untreated women.[32]

The combination of clindamycin and quinine is the standard treatment for severe babesiosis.[33]

Clindamycin may also be used to treat toxoplasmosis,[19][34][35] and, in combination with primaquine, is effective in treating mild to moderate Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.[36]

Side effects

Common adverse drug reactions associated with systemic clindamycin therapy – found in over 1% of people – include: diarrhea, pseudomembranous colitis, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain or cramps and/or rash. High doses (both intravenous and oral) may cause a metallic taste. Common adverse drug reactions associated with topical formulations – found in over 10% of people – include: dryness, burning, itching, scaliness, or peeling of skin (lotion, solution); erythema (foam, lotion, solution); oiliness (gel, lotion). Additional side effects include contact dermatitis.[37][38] Common side effects – found in over 10% of people – in vaginal applications include fungal infection.

Pseudomembranous colitis is a potentially lethal condition commonly associated with clindamycin, but which occurs with other antibiotics, as well.[5][39] Overgrowth of Clostridium difficile, which is inherently resistant to clindamycin, results in the production of a toxin that causes a range of adverse effects, from diarrhea to colitis and toxic megacolon.[37]

Rarely – in less than 0.1% of patients – clindamycin therapy has been associated with anaphylaxis, blood dyscrasias, polyarthritis, jaundice, raised liver enzyme levels, renal dysfunction, cardiac arrest, and/or hepatotoxicity.[37]

Breastfeeding

Clindamycin is classified as compatible with breastfeeding by the American Academy of Pediatrics,[40] however, the World Health Organization categorises it as "avoid if possible".[41] It is classified as L2 probably compatible with breastfeeding according to Medications and Mothers' Milk.[42] A 2009 review found it was likely safe in breastfeeding mothers, but did find one complication (hematochezia) in a breastfed infant which might be attributable to clindamycin.[43]

Interactions

Clindamycin may prolong the effects of neuromuscular-blocking drugs, such as succinylcholine and vecuronium.[44][45][46] Its similarity to the mechanism of action of macrolides and chloramphenicol means they should not be given simultaneously, as this causes antagonism[20] and possible cross-resistance.

Chemistry

Clindamycin is a semisynthetic derivative of lincomycin, a natural antibiotic produced by the actinobacterium Streptomyces lincolnensis. It is obtained by 7(S)-chloro-substitution of the 7(R)-hydroxyl group of lincomycin.[48][49] The synthesis of clindamycin was first announced by BJ Magerlein, RD Birkenmeyer, and F Kagan on the fifth Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC) in 1966.[50] It has been on the market since 1968.[38]

The topically used clindamycin phosphate is a phosphate-ester prodrug of clindamycin.[47]

Mechanism of action

Clindamycin has a primarily bacteriostatic effect. It is a bacterial protein synthesis inhibitor by inhibiting ribosomal translocation,[51] in a similar way to macrolides. It does so by binding to the 50S rRNA of the large bacterial ribosome subunit, overlapping with the binding sites of the oxazolidinone, pleuromutilin, and macrolide antibiotics, among others.[19][52]

The X-ray crystal structures of clindamycin bound to ribosomes (or ribosomal subunits) derived from Escherichia coli,[53] Deinococcus radiodurans,[54] and Haloarcura marismortui[55] have been determined; the structure of the closely related antibiotic lincomycin bound to the 50S ribosomal subunit of Staphylococcus aureus has also been reported.[56]

Market

Cost

It is available as a generic medication and is not very expensive.[9] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about 0.06 to 0.12 USD per pill.[10] In the United States it costs about 2.70 USD per dose.[2]

Available forms

Clindamycin preparations for oral administration include capsules (containing clindamycin hydrochloride) and oral suspensions (containing clindamycin palmitate hydrochloride).[25] Oral suspension is not favored for administration of clindamycin to children, due to its extremely foul taste and odor. Clindamycin is formulated in a vaginal cream and as vaginal ovules for treatment of bacterial vaginosis.[32] It is also available for topical administration in gel form, as a lotion, and in a foam delivery system (each containing clindamycin phosphate) and a solution in ethanol (containing clindamycin hydrochloride) and is used primarily as a prescription acne treatment.[15]

Several combination acne treatments containing clindamycin are also marketed, such as single-product formulations of clindamycin with benzoyl peroxide—sold as BenzaClin (Sanofi-Aventis), Duac (a gel form made by Stiefel), and Acanya, among other trade names—and, in the United States, a combination of clindamycin and tretinoin, sold as Ziana.[57] In India, vaginal suppositories containing clindamycin in combination with clotrimazole are manufactured by Olive Health Care and sold as Clinsup-V. In Egypt, vaginal cream containing clindamycin produced by Biopharmgroup sold as Vagiclind indicated for vaginosis.

Clindamycin is available as a generic drug, for both systemic (oral and intravenous) and topical use.[25] (The exception is the vaginal suppository, which is not available as a generic in the USA).[citation needed]

Clindamycin is marketed as generic and under trade names including Cleocin HCl, Dalacin, Lincocin (Bangladesh), Dalacin, and Clindacin. Combination products include Duac, BenzaClin, Clindoxyl and Acanya (in combination with benzoyl peroxide), and Ziana (with tretinoin).

Veterinary use

The veterinary uses of clindamycin are quite similar to its human indications, and include treatment of osteomyelitis,[58] skin infections, and toxoplasmosis, for which it is the preferred drug in dogs and cats.[59] Toxoplasmosis rarely causes symptoms in cats, but can do so in very young or immunocompromised kittens and cats.

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Clindamycin Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-09-05. Retrieved Sep 4, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Daum RS (2007). "Clinical practice. Skin and soft-tissue infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus". N Engl J Med. 357 (4): 380–90. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp070747. PMID 17652653.

- ^ a b Leyden, James J. (2006). Hidradenitis suppurativa. Berlin: Springer. p. 152. ISBN 9783540331018. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Thomas C, Stevenson M, Riley TV (2003). "Antibiotics and hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea: a systematic review" (PDF). J Antimicrob Chemother. 51 (6): 1339–50. doi:10.1093/jac/dkg254. PMID 12746372. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-07.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Neonatal Formulary: Drug Use in Pregnancy and the First Year of Life (7 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. 2014. p. 162. ISBN 9781118819517. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Smieja, M. (January–February 1998). "Current indications for the use of clindamycin: A critical review". Can J Infect Dis. 9 (1): 22–28. PMC 3250868. PMID 22346533.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 108. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ^ a b "Clindamycin". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Brook I, Lewis MA, Sándor GK, Jeffcoat M, Samaranayake LP, Vera Rojas J. Clindamycin in dentistry: more than just effective prophylaxis for endocarditis? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005 ;100:550-8

- ^ a b "Cleocin I.V. Indications & Dosage". RxList.com. 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-11-27. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Darley ES, MacGowan AP (2004). "Antibiotic treatment of gram-positive bone and joint infections" (PDF). J Antimicrob Chemother. 53 (6): 928–35. doi:10.1093/jac/dkh191. PMID 15117932. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-11-06.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Feldman S, Careccia RE, Barham KL, Hancox J (May 2004). "Diagnosis and treatment of acne" (PDF). Am Fam Physician. 69 (9): 2123–30. PMID 15152959. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-27.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Cunliffe WJ, Holland KT, Bojar R, Levy SF (2002). "A randomized, double-blind comparison of a clindamycin phosphate/benzoyl peroxide gel formulation and a matching clindamycin gel with respect to microbiologic activity and clinical efficacy in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris". Clin Ther. 24 (7): 1117–33. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(02)80023-6. PMID 12182256.

- ^ Leyden JJ, Berger RS, Dunlap FE, Ellis CN, Connolly MA, Levy SF (2001). "Comparison of the efficacy and safety of a combination topical gel formulation of benzoyl peroxide and clindamycin with benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin and vehicle gel in the treatments of acne vulgaris". Am J Clin Dermatol. 2 (1): 33–9. doi:10.2165/00128071-200102010-00006. PMID 11702619.

- ^ Lookingbill DP, Chalker DK, Lindholm JS, et al. (1997). "Treatment of acne with a combination clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide gel compared with clindamycin gel, benzoyl peroxide gel and vehicle gel: combined results of two double-blind investigations". J Am Acad Dermatol. 37 (4): 590–5. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(97)70177-4. PMID 9344199.

- ^ Wolf JE, Kaplan D, Kraus SJ, et al. (2003). "Efficacy and tolerability of combined topical treatment of acne vulgaris with adapalene and clindamycin: a multicenter, randomized, investigator-blinded study". J Am Acad Dermatol. 49 (3 Suppl): S211–7. doi:10.1067/S0190-9622(03)01152-6. PMID 12963897.

- ^ a b c d "Lincosamides, Oxazolidinones, and Streptogramins". Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. Merck & Co. November 2005. Archived from the original on 2007-12-02. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Bell EA (January 2005). "Clindamycin: new look at an old drug". Infectious Diseases in Children. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gold, Howard S.; Robert C. Moellering, Jr. (1999). "Macrolides and clindamycin". In Root, Richard E.; Francis Waldvogel; Lawrence Corey; Walter E. Stamm (eds.). Clinical infectious diseases: a practical approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 291–7. ISBN 0-19-508103-X.

{{cite book}}:|archive-url=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Retrieved January 19, 2009 through Google Book Search. - ^ Jolivet-Gougeon A, Sixou JL, Tamanai-Shacoori Z, Bonnaure-Mallet M (April 2007). "Antimicrobial treatment of Capnocytophaga infections". Int J Antimicrob Agents. 29 (4): 367–73. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.10.005. PMID 17250994.

- ^ http://www.toku-e.com/Assets/MIC/Clindamycin%20phosphate.pdf

- ^ Woods, Charles. "Macrolide-Inducible Resistance to Clindamycin and the D-Test" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-07. Retrieved 2012-06-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Lell B, Kremsner PG (2002). "Clindamycin as an Antimalarial Drug: Review of Clinical Trials" (PDF). Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 46 (8): 2315–20. doi:10.1128/AAC.46.8.2315-2320.2002. ISSN 0066-4804. PMC 127356. PMID 12121898. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Griffith KS, Lewis LS, Mali S, Parise ME (2007). "Treatment of malaria in the United States: a systematic review" (PDF). JAMA. 297 (20): 2264–77. doi:10.1001/jama.297.20.2264. PMID 17519416.

- ^ Dharia NV, Plouffe D, Bopp SE, González-Páez GE, Lucas C, Salas C, Soberon V, Bursulaya B, Kochel TJ, Bacon DJ, Winzeler EA (2010). "Genome scanning of Amazonian Plasmodium falciparum shows subtelomeric instability and clindamycin-resistant parasites". Genome Research. 20 (11): 1534–44. doi:10.1101/gr.105163.110. PMC 2963817. PMID 20829224. Archived from the original on 2016-01-07.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Annane D, Clair B, Salomon J (2004). "Managing toxic shock syndrome with antibiotics". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 5 (8): 1701–10. doi:10.1517/14656566.5.8.1701. PMID 15264985.

- ^ Coyle EA, Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists (2003). "Targeting bacterial virulence: the role of protein synthesis inhibitors in severe infections. Insights from the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists". Pharmacotherapy. 23 (5): 638–42. doi:10.1592/phco.23.5.638.32191. PMID 12741438. Archived from the original on 2008-12-05.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gemmell CG, O'Dowd A (1983). "Regulation of protein A biosynthesis in Staphylococcus aureus by certain antibiotics: its effect on phagocytosis by leukocytes". J Antimicrob Chemother. 12 (6): 587–97. doi:10.1093/jac/12.6.587. PMID 6662837.

- ^ Gemmell CG, Peterson PK, Schmeling D, et al. (1981). "Potentiation of Opsonization and Phagocytosis of Streptococcus pyogenes following Growth in the Presence of Clindamycin". J Clin Invest. 67 (5): 1249–56. doi:10.1172/JCI110152. PMC 370690. PMID 7014632.

- ^ a b Lamont RF (2005). "Can antibiotics prevent preterm birth—the pro and con debate". BJOG. 112 (Suppl 1): 67–73. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00589.x. PMID 15715599.

- ^ Homer MJ, Aguilar-Delfin I, Telford SR, Krause PJ, Persing DH (July 2000). "Babesiosis" (PDF). Clin Microbiol Rev. 13 (3): 451–69. doi:10.1128/CMR.13.3.451-469.2000. PMC 88943. PMID 10885987. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-07-21.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Pleyer U, Torun N, Liesenfeld O (2007). "Okuläre Toxoplasmose" [Ocular toxoplasmosis]. Ophthalmologe (in German). 104 (7): 603–16. doi:10.1007/s00347-007-1535-8. PMID 17530262.

- ^ Jeddi A, Azaiez A, Bouguila H, et al. (1997). "Intérêt de la clindamycine dans le traitement de la toxoplasmose oculaire" [Value of clindamycin in the treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis]. Journal français d'ophtalmologie (in French). 20 (6): 418–22. ISSN 0181-5512. PMID 9296037.

- ^ Fishman JA (June 1998). "Treatment of Infection Due to Pneumocystis carinii" (PDF). Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 42 (6): 1309–14. ISSN 0066-4804. PMC 105593. PMID 9624465. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-04.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006.

- ^ a b De Groot, M. C. H.; Van Puijenbroek, E. N. P. (2007). "Clindamycin and taste disorders". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 64 (4): 542–545. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02908.x. PMC 2048568. PMID 17635503.

- ^ Starr J (2005). "Clostridium difficile associated diarrhoea: diagnosis and treatment". BMJ. 331 (7515): 498–501. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7515.498. PMC 1199032. PMID 16141157. Archived from the original on 2008-03-09.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. The transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics 2001;108;776–89.

- ^ World Health Organization. Breastfeeding and maternal medication. Recommendations for drugs in the eleventh WHO model list of essential drugs. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2002.

- ^ Hale, Thomas Wright (2017). Medications & mothers' milk. Rowe, Hilary E. (Seventeenth ed.). New York, NY: Springer. ISBN 9780826128584. OCLC 959873270.

- ^ Mitrano, Jennifer A; Spooner, Linda M; Belliveau, Paul (2009-09-01). "Excretion of Antimicrobials Used to Treat Methicillin-ResistantStaphylococcus aureusInfections During Lactation: Safety in Breastfeeding Infants". Pharmacotherapy. 29 (9): 1103–1109. doi:10.1592/phco.29.9.1103. ISSN 1875-9114.

- ^ Fogdall RP, Miller RD (1974). "Prolongation of a pancuronium-induced neuromuscular blockade by clindamycin". Anesthesiology. 41 (4): 407–8. doi:10.1097/00000542-197410000-00023. PMID 4415332.

- ^ al Ahdal O, Bevan DR (1995). "Clindamycin-induced neuromuscular blockade". Can J Anaesth. 42 (7): 614–7. doi:10.1007/BF03011880. PMID 7553999.

- ^ Sloan PA, Rasul M (2002). "Prolongation of rapacuronium neuromuscular blockade by clindamycin and magnesium" (PDF). Anesth Analg. 94 (1): 123–4, table of contents. doi:10.1097/00000539-200201000-00023. PMID 11772813.

- ^ a b "Clindamycin Phosphate Topical Solution". RxList. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2017-01-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Birkenmeyer, R. D.; Kagan, F. (1970). "Lincomycin. XI. Synthesis and structure of clindamycin, a potent antibacterial agent". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 13 (4): 616–619. doi:10.1021/jm00298a007. PMID 4916317.

- ^ Meyers BR, Kaplan K, Weinstein L (1969). "Microbiological and Pharmacological Behavior of 7-Chlorolincomycin". Appl Microbiol. 17 (5): 653–7. PMC 377774. PMID 4389137.

- ^ Magerlein, B. J.; Birkenmeyer, R. D.; Kagan, F. (1966). "Chemical modification of lincomycin". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 6: 727–736. PMID 5985307.

- ^ Clindamycin University of Michigan. Retrieved July 31, 2009

- ^ Wilson, Daniel N. (2014). "Ribosome-targeting antibiotics and mechanisms of bacterial resistance". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 12 (1): 35–48. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3155.

- ^ Dunkle, Jack A.; Xiong, Liqun; Mankin, Alexander S.; Cate, Jamie H. D. (2010-10-05). "Structures of the Escherichia coli ribosome with antibiotics bound near the peptidyl transferase center explain spectra of drug action". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (40): 17152–17157. doi:10.1073/pnas.1007988107. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2951456. PMID 20876128. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Schlünzen, Frank; Zarivach, Raz; Harms, Jörg; Bashan, Anat; Tocilj, Ante; Albrecht, Renate; Yonath, Ada; Franceschi, François (2001). "Structural basis for the interaction of antibiotics with the peptidyl transferase centre in eubacteria". Nature. 413 (6858): 814–821. doi:10.1038/35101544.

- ^ Tu, Daqi; Blaha, Gregor; Moore, Peter B.; Steitz, Thomas A. (2005). "Structures of MLSBK Antibiotics Bound to Mutated Large Ribosomal Subunits Provide a Structural Explanation for Resistance". Cell. 121 (2): 257–270. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.005.

- ^ Matzov, Donna; Eyal, Zohar; Benhamou, Raphael I.; Shalev-Benami, Moran; Halfon, Yehuda; Krupkin, Miri; Zimmerman, Ella; Rozenberg, Haim; Bashan, Anat (2017). "Structural insights of lincosamides targeting the ribosome of Staphylococcus aureus". Nucleic Acids Research. 45: 10284–10292. doi:10.1093/nar/gkx658.

- ^ Waknine, Yael (December 1, 2006). "FDA Approvals: Ziana, Kadian, Polyphenon E". Medscape Medical News. Archived from the original (free registration required) on February 6, 2011. Retrieved 2007-12-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ (February 8, 2005) "Osteomyelitis" Archived 2008-01-07 at the Wayback Machine, in Kahn, Cynthia M., Line, Scott, Aiello, Susan E. (ed.): The Merck Veterinary Manual, 9th ed., John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-911910-50-6. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- ^ (February 8, 2005) "Toxoplasmosis: Introduction" Archived 2007-12-20 at the Wayback Machine, in Kahn, Cynthia M., Line, Scott, Aiello, Susan E. (ed.): The Merck Veterinary Manual, 9th ed., John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-911910-50-6. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

External links

- Clindamycin drug information from Lexi-Comp. Includes dosage information and a comprehensive list of international brand names.

- NCBI