Grunge

This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (September 2018) |

| Grunge | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Mid-1980s, Seattle, Washington, U.S. |

| Typical instruments | |

| Derivative forms | |

| Local scenes | |

| Seattle, Washington, U.S. | |

| Other topics | |

Grunge (sometimes referred to as the Seattle sound) is a fusion genre of alternative rock, punk rock, and heavy metal[3] and a subculture that emerged during the mid-1980s in the Pacific Northwest U.S. state of Washington, particularly in Seattle and nearby towns. The early grunge movement revolved around Seattle's independent record label Sub Pop and the region's underground music scene. By the early 1990s its popularity had spread, with grunge bands appearing in California, then emerging in other parts of the United States and in Australia, building strong followings and signing major record deals.

Grunge was commercially successful in the early to mid-1990s, due to releases such as Nirvana's Nevermind, Pearl Jam's Ten, Soundgarden's Badmotorfinger, Alice in Chains' Dirt and Stone Temple Pilots' Core. The success of these bands boosted the popularity of alternative rock and made grunge the most popular form of rock music at the time.[3] Although most grunge bands had disbanded or faded from view by the late 1990s, they influenced modern rock music, as their lyrics brought socially conscious issues into pop culture[4] and added introspection and an exploration of what it means to be true to oneself.[5] Grunge was also an influence on later genres such as post-grunge (such as Creed and Nickelback) and nu metal (such as Korn and Limp Bizkit).

Grunge fuses elements of punk rock, and heavy metal, such as the distorted electric guitar used in both genres, although some bands performed with more emphasis on one or the other. Like these genres, grunge typically uses electric guitar, bass guitar, a drummer and a singer. Grunge also incorporates influences from indie rock bands such as Sonic Youth. Lyrics are typically angst-filled and introspective, often addressing themes such as social alienation, apathy, concerns about confinement, and a desire for freedom.

A number of factors contributed to grunge's decline in prominence. During the mid-to-late 1990s, many grunge bands broke up or became less visible. Nirvana's Kurt Cobain, labeled by Time as "the John Lennon of the swinging Northwest", appeared unusually tortured by success and struggled with an addiction to heroin before he died by suicide at the age of 27 in 1994.

Origin of the term

The word "grunge" first appeared on a 1957 Johnny Burnette rockabilly album,[6] in 1965 as "American English teen slang" to refer to sloppy, dirty aspects or untidiness,[7] by music critic Lester Bangs in 1972,[6] by writer Paul Rambali in a 1978 NME article to describe mainstream guitar rock,[8] and in a 1986 SPIN magazine article which stated that "Noise. Rock has always been about it. There's primal grunge...,distortion...and fuzz...", a reference to distorted sounds in rock in a general sense.[9]

Mark Arm, the vocalist for the Seattle band Green River—and later Mudhoney—is generally credited as being the first to use the term grunge to describe the Seattle genre of music. Arm first used the term in 1981, when he wrote a letter under his given name Mark McLaughlin to the Seattle zine Desperate Times, criticizing his own band Mr. Epp and the Calculations as "Pure grunge! Pure noise! Pure shit!".[10] Clark Humphrey, contributor to Desperate Times, cites this as the earliest use of the term to refer to a Seattle band, and mentions that Bruce Pavitt of Sub Pop popularized the term as a musical label in 1987–88, using it on several occasions to describe Green River.[11] Sub Pop called Green River's 1986 EP Dry as a Bone "ultra-loose GRUNGE that destroyed the morals of a generation."[1] Everett True states that when Arm stated that Seattle's streets were "paved with grunge", he was using the word in a negative way to mean "[w]orthless."[6]

Arm said years later that he did not make the term up himself; he stated that the term had been used in Australia in the mid-1980s to describe bands such as King Snake Roost, The Scientists, Salamander Jim, and Beasts of Bourbon.[12] Arm used grunge as a descriptive term rather than a genre term, but it eventually came to describe the punk/metal hybrid sound of the Seattle music scene.[13] Catherine Strong states that grunge's "dirty sound" in the late 1980s, when low budgets, unfamiliarity with recording and a "deliberate lack of professionalism" may be the origin of the term "grunge".[14] The term "grunge" has been extended to other forms, such as writer Josh Henderson referring to Seattle scene members from the 1990s as "grungers" in 2016.[15]

Grunge was also called the "Seattle sound" or referred to as the "Seattle scene", the latter a reference to the active music subculture in that city centred around the independent label Sub Pop, and the strong alternative scene centred on the University of Washington and the Evergreen State College.[16] Evergreen State was a progressive college which did not use grading and which had its own alternative music radio station.[16] Bands from Portland, Oregon, such as the Wipers, also influenced the genre's pioneers.[17]

Some bands associated with the genre, such as Soundgarden, Pearl Jam and Alice in Chains, have not been receptive to the label, preferring instead to be referred to as "rock and roll" bands.[18][19][20] Ben Shepherd from Soundgarden stated that he "hates the word" grunge and hates "being associated with it."[21] Seattle musician Jeff Stetson states that when he visited Seattle in the late 1980s and early 1990s as a touring musician, the local musicians did not refer to themselves as "grunge" performers or their style as "grunge" and they were not flattered that their music was being called "grunge".[22]

Rolling Stone noted the genre's lack of a clear definition.[23] Robert Loss acknowledges the challenges of defining "grunge"; stating that while he can recount stories about grunge, they do not serve to provide a useful definition.[24] Roy Shuker states that the term "obscured a variety of styles."[16] Stetson states that grunge was not a movement, "monolithic musical genre", or a way to react to 1980s-era metal pop; he calls the term a misnomer mostly based on hype.[22] Shuker states that the "'Seattle sound' became a marketing ploy for the music industry." [16] Stetson also states that prominent bands considered to be grunge (Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Alice in Chains, Mudhoney and Hammerbox) all sound different.[22] Mark Yarm, author of Everybody Loves Our Town: An Oral History of Grunge, pointed out vast differences between grunge bands, with some being punk and others being metal-based.[21]

Characteristics

Musical style

Seattle music journalist Charles R. Cross defines "grunge" as distortion-filled, down-tuned and riff-based rock that uses loud electric guitar feedback and heavy, "ponderous" bass lines to support its song melodies.[25] Robert Loss calls grunge a melding of "violence and speed, muscularity and melody", where there is space for all people, including women musicians.[24]

Grunge fuses elements of punk rock (specifically American hardcore punk such as Black Flag) and heavy metal (especially traditional, earlier heavy metal groups such as Black Sabbath), although some bands performed with more emphasis on one or the other. Allmusic calls grunge a "hybrid" that blends elements of heavy metal and punk rock.[3] Alex DiBlasi states that indie rock was a third key source, with the most important influence coming from Sonic Youth's "free-form" noise.[1] Grunge shares with punk a raw, lo fi sound and similar lyrical concerns,[3] and it also used punk's haphazard and untrained approach to playing and performing. However, grunge was "deeper and darker"-sounding than punk rock and it decreased the "adrenaline"-fueled tempos of punk to a slow, "sludgy" speed[26] and used more dissonant harmonies.

As well, VH1 writer Dan Tucker points out that different grunge bands were influenced by different genres. He stated that while Nirvana drew on punk, Pearl Jam was influenced by classic rock and "sludgy, dark, heavy bands" such as Soundgarden, Alice in Chains and Tad had a sinister metal tone.[27]

Grunge music has what has been called an "ugly" aesthetic, both in the roar of the distorted electric guitars and in the darker lyrical topics. This approach was chosen both to counter the "slick" elegant sound of the then-predominant mainstream rock and because grunge artists wanted to mirror the "ugliness" they saw around them and shine a light on unseen "depths and depravity" of the real world.[28] Some key individuals in the development of the grunge sound, including Sub Pop producer Jack Endino and the Melvins, explained grunge's incorporation of heavy rock influences such as Kiss as "musical provocation". Grunge artists considered these bands "cheesy" but nonetheless enjoyed them; Buzz Osborne of the Melvins described it as an attempt to see what ridiculous things bands could do and get away with.[29] In the early 1990s, Nirvana's signature "stop-start" song format and alternating between soft and loud sections became a genre convention.[3]

Instruments

Electric guitar

Grunge is generally characterized by a sludgy electric guitar sound with a "thick" middle register and rolled-off treble tone and a high level of distortion and fuzz, typically created with small 1970s-style stompbox pedals, with some guitarists chaining several fuzz pedals together and plugging them into a tube amplifier and speaker cabinet.[30] Grunge guitarists use very loud Marshall guitar amplifiers [31] and some used powerful Mesa-Boogie amplifiers, including Kurt Cobain and Dave Grohl (the latter in early, grunge-oriented Foo Fighters songs ).[32] Grunge has been called the rock genre with the most "lugubrious sound"; the use of heavy distortion and loud amps has been compared to a massive "buildup of sonic fog".[33] or even dismissed as "noise" by one critic.[34] As with metal and punk, a key part of grunge's sound is very distorted power chords played on the electric guitar.[26]

Whereas metal guitarists' overdriven sound generally comes from a combination of overdriven amplifiers and distortion pedals, grunge guitarists typically got all of their "dirty" sound from overdrive and fuzz pedals, with the amp just used to make the sound louder.[32] Grunge guitarists tended to use the Fender Twin Reverb and the Fender Champion 100 combo amps (Cobain used both of these amps).[32] The use of pedals by grunge guitarists was a move away from the expensive, studio-grade rackmount effects units used in other rock genres. The positive way that grunge bands viewed stompbox pedals can be seen in Mudhoney's use of the name of two overdrive pedals, the Univox Super-Fuzz and the Big Muff, in the title of their "debut EP Superfuzz Bigmuff".[35] In the song Mudride, the band's guitars were said to have "growled malevolently" through its "Cro-magnon slog".[36]

Other key pedals used by grunge bands included four brands of distortion pedals (the Big Muff, DOD and BOSS DS-2 and BOSS DS-1 distortion pedals) and the Small Clone chorus effect, used by Kurt Cobain on "Come As You Are" and by the Screaming Trees on "Nearly Lost You".[32] The RAT distortion pedal played a key role in Cobain’s switching from quiet to loud and back to quiet approach to songwriting.[37] The use of small pedals by grunge guitarists helped to start off the revival of interest in boutique, hand-soldered, 1970s-style analog pedals.[30] The other effect that grunge guitarists used was one of the most low-tech effects devices, the wah-wah pedal. Both "[Kim] Thayil and Alice in Chains’ Jerry Cantrell...were great advocates of the wah wah pedal."[30] Wah was also used by the Screaming Trees, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Mudhoney and Dinosaur Jr.[32]

Grunge guitarists played loud, with Kurt Cobain's early guitar sound coming from an unusual set-up of four 800 watt PA system power amplifiers.[30] Guitar feedback effects, in which a highly amplified electric guitar is held in front of its speaker, were used to create high-pitched, sustained sounds that are not possible with regular guitar technique. Grunge guitarists were influenced by the raw, primitive sound of punk, and they favored "...energy and lack of finesse over technique and precision"; key guitar influences included the Sex Pistols, The Dead Boys, Celtic Frost, Voivod, Neil Young[38] (Rust Never Sleeps, side two), The Replacements, Hüsker Dü, Black Flag and The Melvins.[39] Grunge guitarists often downtuned their instruments for a lower, heavier sound.[30] Soundgarden’s guitarist, Kim Thayil, did not use a regular guitar amplifier; instead, he used a bass combo amp equipped with a 15-inch speaker as he played low riffs, and the bass amp gave him a deeper tone.[30]

Guitar solos

Grunge guitarists "flatly rejected" the virtuoso "shredding" guitar solos that had become the centerpiece of heavy metal songs, instead opting for melodic, blues-inspired solos – focusing "on the song, not the guitar solo".[40] Jerry Cantrell of Alice in Chains stated that solos should be to serve the song, rather than to show off a guitarist's technical skill.[41] In place of the strutting guitar heroes of metal, grunge had "guitar anti-heroes" like Cobain, who showed little interest in mastering the instrument.[39]

In Will Byers' article "Grunge committed a crime against music--it killed the guitar solo", in The Guardian, he states that while the guitar solo managed to survive through the punk rock era, it was weakened by grunge.[42] He states that when Kurt Cobain played guitar solos that were a restatement of the main vocal melody, fans realized that they did not need to be a Jimi Hendrix-level virtuoso to play the instrument; he says this approach helped to make music feel accessible by fans in a way not seen since the 1960s folk music movement.[43] The producer of Nirvana's Nevermind, Butch Vig, stated that this album and Nirvana "killed the guitar solo".[44] Soundgarden guitarist Kim Thayil stated he feels in part to be responsible for the "death of the guitar solo"; he said that his punk rocker aspects made him feel that he did not want to solo, so in the 1980s, he preferred to make noise and do feedback during the guitar solo.[45] Baeble Music calls the grunge guitar solos of the 1990s "..raw", "sloppy" and "basic".[46]

Not all sources support the "grunge killed the guitar solo" argument. Sean Gonzalez states that Pearl Jam has plentiful examples of guitar solos.[44] Michael Azerrad praises the guitar playing of Mudhoney's Steve Turner, calling him the "...Eric Clapton of grunge", a reference to the British blues guitarist [47] who Time magazine has named as number five in their list of "The 10 Best Electric Guitar Players".[48] Pearl Jam guitarist Mike McCready has been praised for his blues-influenced, rapid licks.[49] The Smashing Pumpkins' guitarist Billy Corgan has been called the "...arena rock genius of the 90’s" for pioneering guitar playing techniques and showing through his playing skill that grunge guitarists do not have to be sloppy players to rebel against mainstream music.[49] Thayil stated that when other major grunge bands, such as Nirvana, were reducing their guitar solos, Soundgarden responded by bringing back the solos.[45]

Bass guitar

For bass guitar playing, About.com's Melissa Bobbitt highlights the bass work of The Smashing Pumpkins' D'arcy Wretzky.[50] Bobbitt states that in the song "I Am One", Wretsky's "...combative bass line" and "slinky delivery" (i.e., playing style) on electric bass "...was the glue that held [the song] all together".[50] Bobbitt also praises Alice in Chains bassist Mike Starr’s bass playing on the EP "Would?". She states that Starr's "...bass line sounds like the slithering coil of the dragon that is heroin...".[50] "Would?" was written as a tribute to Mother Love Bone singer Andrew Wood, who died from a heroin overdose. NME states that Nirvana's bassist Krist Novoselic's "...dirty, sliding bass lines anchor[ed] the grunge chaos around him" created by singer-guitarist Kurt Cobain and drummer Dave Grohl.[51] TAD's Kurt Danielson stated that he was "...completely blown away [by] Krist's bass playing."[52] The early Seattle grunge album Skin Yard recorded in 1987 by the band of the same name included fuzz bass (overdriven bass guitar) played by Jack Endino and Daniel House.[53] Some grunge bassists, such as Ben Shepherd, layered power chords with distorted low-end density by adding a fifth and an octave-higher note to a bass note.[54]

An example of the powerful, loud bass amplifier systems used in grunge is Alice in Chains bassist Mike Inez's setup. He uses four powerful Ampeg SVT-2 PRO tube amplifier heads, two of them plugged into four 1x18" subwoofer cabinets for the low register, and the other two plugged into two 8x10" cabinets.[55] Krist Novoselic and Jeff Ament are also known for using Ampeg SVT tube amplifiers.[56][57] Ben Shepherd uses a 300 watt all-tube Ampeg SVT-VR amp and a 600 watt Mesa/Boogie Carbine M6 amplifier.[58] Ament uses four 6x10" speaker cabinets.[57]

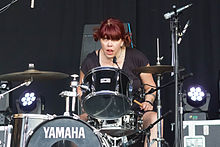

Drums

Modern Drummer Magazine states that the pioneering drummers who created the "gritty punk-meets-metal Seattle sound" were the "highly influential" Dale Crover from the Melvins and Alex Vincent from Green River.[59] Bobbitt lists among the top ten alternative rock drummers from the 1990s five musicians who have been associated with grunge. Her list includes Nirvana's Dave Grohl, The Smashing Pumpkins' Jimmy Chamberlin, Hole's Patty Schemel, Pearl Jam and Soundgarden's Matt Cameron (he played in both bands), and Babes in Toyland's Lori Barbero.[60] Bobbitt calls Dave Grohl a "gifted" drummer and she says he "kills his [drum]kits" in concerts. Blake Madden praises Grohl's "precise and powerful drumming"[61] and Modern Drummer Magazine states that Grohl's work with Nirvana was the "...most impassioned and expertly crafted drumming" in rock history.[59] Bobbitt states that Jimmy Chamberlin had a "jazz background", which infused his band's grunge sound with the "lightness and versatility" of Buddy Rich-style swing jazz drumming.[60] Bobbitt states that while Patty Schemel struggled with drugs and alcohol during her tenure in Courtney Love's musical groups from 1992 to 1998, Schemel turned "clean and sober", enabling her to garner recognition for "...her ability to tear up the percussion" kit; Bobbitt notes that Love hired Schemel based on Cobain's recommendation of Schemel's drum skills.[60] Bobbitt states that Matt Cameron holds the distinction of playing drums in two major grunge bands: Pearl Jam and Soundgarden. She calls him "grunge's [drum] guru" and praises his "forceful" playing and huge dynamic (loudness and softness) changes. As well, she notes that Soundgarden singer Chris Cornell stated that Cameron's playing was an important source of confidence for the band.[60] Bobbitt also praises Lori Barbero, a "self-taught" player with "inimitable" drumkit style who "finds...strength [with] tribal" playing and who could "summon hellfire" with the power of her drum sound.[60]

In contrast to the "massive drum kits" used in 1980s pop metal,[62] grunge drummers used relatively smaller drum kits. One example of the drumkit used by a notable grunge drummer is Matt Cameron's set-up. He uses a six-piece kit (this way of describing drumkits counts only the wooden drums, and does not count the cymbals), including a "12x8-inch rack tom; 13x9-inch rack tom; 16x14-inch floor tom; 18x16-inch floor tom; 24x14-inch bass drum" and a snare drum and, for cymbals, Zildjian instruments, including "...14-inch K Light [Hi-]hats; 17-inch K Custom Dark crash [cymbal] and 18-inch K Crash Ride; 19-inch Projection crash; a 20-inch Rezo crash;...and a... 22-inch A Medium ride [cymbal]".[63] A second example is Dave Grohl's set-up during 1990 and 1991. He used a four-piece Tama drumset, with an 8" × 14" birch snare drum, a 14" × 15" rack tom, a 16" × 18" floor tom and a 16" × 24" bass drum (this kit "...was demolished at the Cabaret Metro, Chicago, 10/12/91").[64] Like Cameron, Grohl used Zildjian cymbals. Grohl used the company's A Series Medium cymbals, including an 18" and a 20" crash cymbal, a 22" ride cymbal and a pair of 15" hi-hat cymbals.[64]

Other instruments

Although keyboards are generally not used in grunge, Seattle band Gorilla created controversy by breaking the "guitars only" approach and using a 1960s-style Vox organ in their group.[65] In 2002, Pearl Jam added a keyboard player named Kenneth "Boom" Gaspar, who played piano, Hammond organ and other keyboards; the addition of a keyboardist to the band would have been "inconceivable" in the band's "grungy" early years, but it shows how a group's sound can change over time.[66]

Singing

The grunge singing style was similar to the "outburst" of loud, heavily distorted electric guitar in tone and delivery; Kurt Cobain used a "gruff, slurred articulation and gritty timbre" and Eddie Vedder of Pearl Jam made use of a "wide, powerful vibrato" to show his "depth of expression."[35] In general, grunge singers used a "deeper vocal style" which matched the lower-sounding, downtuned guitars and the darker-themed lyrical messages used in the style.[30] Grunge singers used "gravelly, raspy" vocals,[26] "...growls, moans, screams and mumbles" [67] and "plaintive groans"; this range of singing styles was used to communicate the "varied emotions" of the lyrics.[68] Cobain’s reaction to the "bad times" and discontent of the era was that he screamed his lyrics.[69] In general, grunge songs were sung "simply, often somewhat unintelligibly"; the virtuoso "operatics of hair-metal were shunned."[69] Grunge singing has been characterized as "borderline out-of-tune vocals".[70]

According to The Atlantic, the four most influential grunge singers were Alice in Chains' Layne Staley, Soundgarden's Chris Cornell, Vedder, and Cobain.[71] Jeff Stetson praises Cobain and Mark Lanegan for the distinctiveness of their singing voices and he calls Cornell, Staley and Carrie Akre "...some of the greatest voices...to be heard in modern rock"; he also states that these singers achieved their vocal level without the 2010s-era "industry standard air brushing" of Auto Tune pitch correction.[22]

Lyrics

Grunge lyrics are typically dark, nihilistic,[1] angst-filled, and anguished, often addressing themes such as social alienation, apathy, concerns about confinement, and a desire for freedom. An article by MIT states that grunge "lyrics [were] obsessed with disenfranchisement" and described a mood of "resigned despair".[72] Catherine Strong states that grunge songs were usually about "negative experiences or feelings", with the main themes being alienation and depression, but with an "ironic sneer." [73] Grunge artists expressed "strong feelings" in their lyrics about "societal ills", including a "desire to 'crucify the insincere'", an approach which fans appreciated for its authenticity.[74] Grunge lyrics have been criticized as "...violent and often obscene." [75] In 1996, conservative columnist Rich Lowry wrote an essay criticizing grunge, entitled "Heroin, Our Hero"; he called it a music that is mostly "...shorn of ideals and the impulse for political action".[76]

A number of factors influenced the focus on such subject matter. Many grunge musicians displayed a general disenchantment with the state of society, as well as a discomfort with social prejudices. Grunge lyrics contained "...explicit political messages and...questioning about...society and how it might be changed...".[77] While grunge lyrics were less overtly political than punk songs, grunge songs still indicated a concern for social issues, particularly those affecting young people.[73] The main themes in grunge were "tolerance of difference", "support of women", "mistrust of authority" and "cynicism towards big corporations."[73] Grunge song themes bear similarities to those addressed by punk rock musicians.[3] In 1992, music critic Simon Reynolds said that "there's a feeling of burnout in the culture at large. Kids are depressed about the future".[78] The topics of grunge lyrics–homelessness, suicide, rape,[73] "broken homes, drug addiction and self-loathing" contrasted sharply to the glam metal lyrics of Poison, which described "life in the fast lane",[79] partying and hedonism.

Grunge lyrics developed as part of "Generation X malaise", reflecting that demographic's feelings of "disillusionment and uselessness".[80] Grunge songs about love were usually about "...failed, boring, doomed or destructive relationships." (e.g., "Black" by Pearl Jam).[73] Alice in Chains songs "Dirt" and "Hate to Feel" have heroin references.[81] Grunge lyrics tended to be more introspective and aimed to enable the listener to see into "hidden" personal issues and examine the "depravity" of the world.[28] This approach can be seen in Mudhoney's song "Touch Me, I'm Sick", which includes lyrics with "deranged imagery" which depict a "broken world and a fragmented self-image"; the song includes the lines "I feel bad, and I've felt worse" and "I won't live long and I'm full of rot".[26] Nirvana's song "Lithium", from their 1991 album Nevermind, is about a "...man who finds faith after his girlfriend's suicide"; it depicts "...irony and ugliness" as a way of dealing with these "dark issues".[28]

Production

Like punk, grunge's sound came from a lo fi (low fidelity) recording and production approach.[26] Before the arrival of major labels, early grunge albums were recorded using low-budget studios: "Nirvana's first album Bleach, was recorded for $606.17 in 1989."[82] Sub Pop recorded most of their music at a "...low-rent studio named Reciprocal", where producer Jack Endino created the grunge genre's aesthetic, a "raw and unpolished sound with distortion, but usually without any added studio effects".[83] Endino is known for his stripped-down recording practices and his dislike of 'over-producing' music with effects and remastering. His work on Soundgarden's Screaming Life and Nirvana's Bleach as well as for the bands Green River, Screaming Trees, L7, The Gits, Hole, 7 Year Bitch, and TAD helped to define the grunge sound. An example of the lower cost production approach is Mudhoney; even after the band signed to Warner Music, "[t]rue to [the band's] indie roots...[they are]...probably one of the few bands that would have to fight [their label] to record for a lower budget rather than a higher one."[47]

Steve Albini, nicknamed the "Godfather of grunge",[84] was another important influence on the grunge sound. Albini prefers to be called a "recording engineer", because he believes that putting record producers in charge of recording sessions often destroys the band's real sound, while the role of the recording engineer is to capture the actual sound of the musicians, not to threaten the artists' control over their creative product.[85] Albini's recordings have been analyzed by writers such as Michael Azerrad, who stated that Albini's "recordings were both very basic and very exacting: like Endino, Albini used few special effects; got an aggressive, often violent guitar sound; and made sure the rhythm section slammed as one."[86]

Nirvana's In Utero is a typical example of Albini's recording approach. He preferred to have the entire band play live in the studio, rather than use mainstream rock's approach of recording each instrument on a separate track at different times, and then mixing them using multi-track recording. While multitracking results in a more polished product, it does not capture the "live" sound of the band playing together. Albini used a range of different microphones for the vocals and instruments. Like most metal and punk recording engineers, he mics the guitar amp speakers and bass amp speakers to capture each performer's unique tone.

Concerts

Grunge concerts were known for being straightforward, high-energy performances. Grunge shows were "...celebrations, parties [and] carnivals" where the audience expressed its spirit by stagediving, moshing and thrashing.[87] Simon Reynolds states that in "...some of the most masculine forms of rock —thrash metal, grunge, moshing becomes a form of surrogate combat" in which "male bodies" can contact in the "sweat-and-bloodbath" of the moshpit.[88] As with punk shows, grunge "...performances were about frontmen who screamed and jumped around on stage and musicians who thrashed wildly on their instruments."[89] While grunge lyrical themes focused on "angst and rage", the audience at shows were positive and created a "life-affirming" attitude.[87] Grunge bands rejected the complex and high budget presentations of many mainstream musical genres, including the use of complex digitally controlled light arrays, pyrotechnics, and other visual effects then popular in "hair metal" shows. Grunge performers viewed these elements unrelated to playing the music. Stage acting and "onstage theatrics" were generally avoided.[79]

Instead the bands presented themselves as no different from minor local bands. Jack Endino said in the 1996 documentary Hype! that Seattle bands were inconsistent live performers, since their primary objective was not to be entertainers, but simply to "rock out".[29] Grunge bands gave enthusiastic performances; they would thrash their long hair during shows as "a symbolic weapon" for releasing "pent-up aggression" (Dave Grohl was particularly noted for his "head flips").[90] One of the philosophies of the grunge scene was authenticity. Dave Rimmer writes that with the revival of punk ideals of stripped-down music in the early 1990s, "for Cobain, and lots of kids like him, rock & roll...threw down a dare: Can you be pure enough, day after day, year after year, to prove your authenticity, to live up to the music ... And if you can't, can you live with being a poseur, a phony, a sellout?"[91]

Clothing and style

1980s–1990s

Clothing commonly worn by grunge musicians in Washington were a "mundane everyday style", in which they would wear the same clothes on stage that they wore at home.[26] This Pacific Northwest "slacker style" or "slouch look" contrasted sharply with the "wild" mohawks, leather jackets and chains worn by punks. This everyday clothing approach was used by grunge musicians because authenticity was a key principle in the Seattle scene.[26] The grunge look typically consisted of thrift store items and the typical outdoor clothing (most notably flannel shirts) of the region, as well as a generally unkempt appearance and long hair.[79] For grunge singers, long hair was used "as a mask to conceal the face" so they can "expres[s their] innermost thoughts"; Cobain is a notable example.[90] Male grunge musicians were "...unkempt...[and]...unshaven[92] [,] with...tousled hair"[93] that was often unwashed, greasy and "...matted [into a] sheep-dog mop".[94]

Seattle and Aberdeen, Washington were logging towns and hence, the lumberjack attire was a common sight in the thrift stores for the low prices that musicians could afford.[95] Grunge style consisted of ripped jeans, thermal underwear,[80] mom jeans, Doc Martens boots or combat boots (often unlaced), band T-shirts, oversized knit sweaters, long and droopy skirts, ripped tights, Birkenstocks, hiking boots,[96][97][98] and eco-friendly clothing made from recycled textiles or fair trade organic cotton.[99] As well, since women in the grunge scene wore the "...same plaid [shirt]s, boots, and short cropped heads as their male counterparts", women showed "...that they are not defined by their sex appeal."[100]

"Grunge...became an anti-consumerist movement where the less you spent on clothes, the more ‘coolness’ you had."[101] The style did not evolve out of a conscious attempt to create an appealing fashion; music journalist Charles R. Cross said, "[Nirvana frontman] Kurt Cobain was just too lazy to shampoo", and Sub Pop's Jonathan Poneman said, "This [clothing] is cheap, it's durable, and it's kind of timeless. It also runs against the grain of the whole flashy aesthetic that existed in the 80s."[78] The flannel and "...cracked leatherette coats" in the grunge scene were part "...of the Pacific Northwest's thrift-shop esthetic.[94] Grunge fashion was very much an anti-fashion response and a non-conformist move against the "manufactured image",[102] often pushing musicians to dress in authentic ways and to not glamorize themselves. At the same time, Sub-Pop utilized the ‘grunge look’ in their marketing of their bands. In an interview with VH1, photographer Charles Peterson commented that members from grunge band Tad "were given blue collar identities that weren’t entirely earned. Bruce (Pavitt) really got him to dress up in flannel and a real chain saw and really play up this image of a mountain man and it worked."[103]

Dazed magazine calls Courtney Love One of "ten women who defined the 1990s" from a style perspective: the "...image of Courtney Love’s too-short baby doll dress, tattered fur coat and shock of platinum hair", a look dubbed "kinderwhore", "...topped with a tiara, of course – is seared on the memory of anyone who lived through the decade."[104] The kinderwhore look consisted of torn, ripped tight or low-cut babydoll and peter pan collared dresses, slips, heavy makeup with dark eyeliner,[105] barrettes, and leather boots or Mary–Jane shoes.[106][107][108] Kat Bjelland of Babes in Toyland was the first to define it, while Courtney Love of Hole was the first to popularize it. Love has claimed that she took the style from Divinyls frontwoman Christina Amphlett.[106] The look became very popular in 1994.[109]

Vogue stated in 2014 that "Cobain pulled liberally from both ends of a woman’s and a man’s wardrobe, and his Seattle thrift-store look ran the gamut of masculine lumberjack workwear and 40s-by-way-of-70s feminine dresses. It was completely counter to the shellacked, flashy aesthetic of the 1980s in every way. In disheveled jeans and floral frocks, he softened the tough exterior of the archetypal rebel from the inside out, and set the ball in motion for a radical, millennial idea of androgyny."[110] Cobain's way of dressing "was the antithesis of the macho American man", because he "...made it cooler to look slouchy and loose, no matter if you were a boy or a girl."[110] Music and culture writer Julianne Escobedo Shepherd wrote that with Cobain's style of dress "Not only did he make it okay to be a freak, he made it desirable."[110]

Adoption by mainstream

Grunge music hit the mainstream in the early 1990s with Soundgarden, Alice in Chains, and Nirvana being signed to major record labels. Grunge fashion began to break into mainstream fashion in mid-1992 for both sexes and peaked in late 1993 and early 1994.[96][111][112] As it picked up momentum, the grunge tag was being used by shops selling expensive flannelette shirts to cash in on the trend.[101] Ironically, the non-conformist look suddenly became a mainstream trend. In the fashion world, Marc Jacobs presented a show for Perry Ellis in 1992, featuring grunge-inspired clothing mixed with high-end fabrics. Jacobs found inspiration in the ‘realism’ of grunge streetwear; he mixed it with the luxury of fashion by sending models down the catwalk in beanies, floral dresses and silk flannel shirts.[113] Unfortunately, this did not sit well with the brand owners and Jacobs was dismissed. Other designers like Anna Sui, also drew inspiration from grunge during the spring/summer 1993 season.[102]

In the same year, Vogue did a spread called "Grunge & Glory" with fashion photographer Steven Miesel who shot supermodels Naomi Campbell and Kristen McMenamy in a savanna landscape wearing grunge-styled clothing. This shoot made McMenamy the face for grunge, as she had her eyebrows shaved and her hair cropped short. Designers like Christian Lacroix, Donna Karen and Karl Lagerfeld incorporated the grunge influence into their looks.[113] In 1993, James Truman, editor of Details, said: "to me the thing about grunge is it’s not anti-fashion, it’s unfashion. Punk was anti-fashion. It made a statement. Grunge is about not making a statement, which is why it’s crazy for it to become a fashion statement."[114] The unkempt fashion sense defined the look of the "slacker generation", who "skipped school, smoked pot...[and] cigarettes and listened to music" hoping to become a rock star one day.[103]

2000s–2010s

Even though the grunge movement died down in 1994 after the death of Kurt Cobain, designers have continued to draw inspiration from the movement from time to time. Grunge appeared as a trend again in 2008 and for Fall/Winter 2013, Hedi Slimane at Yves Saint Laurent brought back grunge to the runway. With Courtney Love as his muse for the collection, she reportedly loved the collection. "No offense to MJ [Marc Jacobs] but he never got it right," Courtney said. "This is what it really was. Hedi knows his shit. He got it accurate, and MJ and Anna [Sui] did not."[115] Both Cobain and Love apparently burnt the Perry Ellis collection they received from Marc Jacobs back in 1993.[116] In 2016, grunge inspired an upscale "reinvention" of the style by A$AP Rocky, Rihanna and Kanye West.[117] However, "dressing grunge is no longer a badge of authenticity, though: the signifiers of rebellion (Dr Martens boots, plaid shirts) are omnipotent on the high street", says Lynette Nylander, deputy editor of i-D magazine.[117]

Alcohol and drugs

Many music subcultures are associated with particular drugs, such as the hippie counterculture and reggae, both of which are associated with marijuana and psychedelics. In the 1990s, the media focused on the use of heroin by musicians in the Seattle grunge scene, with a 1992 New York Times article listing the city's "three principal drugs" as "espresso, beer and heroin" [82] and a 1996 article calling Seattle's grunge scene the "...subculture that has most strongly embraced heroin".[118] Tim Jonze from The Guardian states that "...heroin had blighted the [grunge] scene ever since its inception in the mid-80s" and he argues that the "...involvement of heroin mirrors the self-hating, nihilistic aspect to the music"; in addition to the heroin deaths, Jonze points out that Stone Temple Pilots' Scott Weiland, as well as Courtney Love, Mark Lanegan, Jimmy Chamberlin and Evan Dando "...all had their run-ins with the drug, but lived to tell the tale."[119] A 2014 book stated that whereas in the 1980s, people used the "stimulant" cocaine to socialize and "...celebrate good times", in the 1990s grunge scene, the "depressant" heroin was used to "retreat" into a "cocoon" and be "...sheltered from a harsh and unforgiving world which offered...few prospects for...change or hope."[120] Justin Henderson states that all of the "downer" opiates, including "heroin, morphine, codeine, opium, [and] hydrocodone...seemed to be the habit of choice for many a grunger".[15]

The title of Nirvana's debut album Bleach was inspired by a harm reduction poster aimed at heroin injection users, which stated "Bleach your works [e.g., syringe and needle ] before you get stoned". The poster was released the U.S. State Health Department which was trying to reduce AIDS transmission caused through sharing used needles. Alice in Chains' song "God Smack" includes the line "stick your arm for some real fun", a reference to injecting heroin.[118] Seattle musicians known to use heroin included Cobain, who was using "heroin when he shot himself in the head"; "Andrew Wood of Mother Love Bone [, who] overdosed on heroin in 1990"; "Stefanie Sargent of 7 Year Bitch[, who] died of an overdose of the same opiate in 1992...[and] Layne Staley of Alice in Chains [who] publicly detailed his battles with heroin...".[121] Mike Starr of Alice in Chains [120] and Jonathan Melvoin from The Smashing Pumpkins also died from heroin. After Cobain's death, his "...widow, singer Courtney Love, characterized Seattle as a drug mecca, where heroin is easier to get than in San Francisco or Los Angeles."[121]

However, Daniel House, who owned C/Z Records, disputed these perceptions in 1994. House stated that there was "...no more (heroin) here [in Seattle] than anyplace else"; he stated that the "heroin is not a big part of the [Seattle music] culture", and that "marijuana and alcohol...are far more prevalent". Jeff Gilbert, one of the editors of Guitar World magazine, stated in 1994 that the media association of the Seattle grunge scene with heroin was "really overblown"; instead, he says that Seattle musicians were "...all a bunch of potheads."[121] Gil Troy's history of America in the 1990s states that in the Seattle grunge scene, the "...drug of choice switched from upscale cocaine [of the 1980s] to blue-collar marijuana."[122] Rolling Stone magazine reported that members of Seattle's grunge scene were "coffee-crazed" by day on espresso and "...by night, they quaff[ed] oceans of beer – jolted by Java and looped with liquor, no wonder the [grunge] music sounds like it does." [123] "Some [Seattle] scene veterans maintain that MDA", a drug related to Ecstasy, "was a vital contributor to grunge", because it gave users a "body high" (in contrast to marijuana's "head high") that made them appreciate "bass-heavy grooves".[124] Pat Long's History of the NME states that scene members involved with the Sub Pop label would have multi-day MDMA parties in the woods, which shows that what Long calls Ecstasy's "warm glow" had an impact even in the wet, grey and isolated Pacific Northwest region.[125]

Graphic design

Regarding graphic design and images, a common feature of grunge bands was the use of "lo-fi" (low fidelity) and deliberately unconventional album covers, for example presenting intentionally murky or miscolored photography, collage or distressed lettering. Early grunge "[a]lbum covers and concert flyers appeared Xeroxed not in allegiance to some DIY aesthetic" but because of "economic necessity", as "bands had so little money".[126] This was already a common feature of punk rock design, but could be extended in the grunge period due to the increasing use of Macintosh computers for desktop publishing and digital image processing. The style was sometimes called 'grunge typography' when used outside music.[127][128][129] A famous example of 'grunge'-style experimental design was Ray Gun magazine, art directed by David Carson.[130][131]

Carson, who has been called the "Godfather of Grunge" graphic design, developed a technique of "ripping, shredding and remaking letters"[130][131] and using "overprinted, disharmonious letters" and experimental design approaches, including "deliberate 'mistakes' in alignment".[132] Carson's art used "...messy and chaotic design" and he did not "..respect any rule of composition", using an "..experimental, personal and intuitive" approach.[133] Another "grunge graphic designer" was Elliott Earls, who used "distorted...older typefaces" and "aggressively illegible" type which adopted the "unkempt expressiveness" of the "grunge [music] aesthetic"; this radical, anti-establishment approach in graphic design was influenced by the 1910s-era avant-garde Dada movement.[132] Hat Nguyen's Droplet, Harriet Goren's Morire and Eric Lin's Tema Canante were all "signature grunge fonts."[130][131] Sven Lennartz states that grunge design images have a "realistic, genuine look" which is created by adding simulated torn paper, dog-eared corners, creases, yellowed scotch tape, coffee cup stains, hand-drawn images and handwritten words, typically over a "dirty" background texture which is done with dull, subdued colours.[134]

A key figure in creating the "look" of the grunge scene for outsiders was music photographer Charles Peterson. Peterson's black and white, uncropped, and sometimes blurry shots of the underground Pacific Northwest music scene's members playing and jamming, wearing their characteristic everyday clothes, were used by Sub Pop to promote its Seattle bands.

Literature

Zines

Following the 1980s tradition of amateur, fan-produced zines in the punk subculture, members of the grunge scene also produced DIY publications which were "distributed at gigs or by mail order". The zines were typically photocopied and contained handwritten, "hand-coloured pages", "typing errors and grammatical mistakes, misspellings and jumbled pagination", all proof of their amateur nature.[135] Backlash was a zine that was published from 1987–1991 by Dawn Anderson, covering the "...dirtier, heavier, more underground and rock side of Seattle's music scene", including "...punk, metal, underground rock, grunge before it was called grunge and even some local hip-hop."[136] Grunge Gerl #1 was one early 1990s grunge zine, was written by and for riot grrrls in the Los Angeles area. It stated that "...we're girls, we're angry, we're powerful."[135]

Local newspapers

In 1992, Rolling Stone music critic Michael Azerrad called The Rocket the Seattle music "scene's [most] respected commentator".[47] The Rocket was a free newspaper about the Pacific Northwest music scene which was launched in 1979. Edited by Charles R. Cross, the paper only covered "fairly obscure alternative bands" in the local area, such as The Fartz, The Allies, The Heats/The Heaters, Visible Targets, Red Dress, and The Cowboys.[137] In the mid-1980s, the paper had stories on Slayer, Wild Dogs, Queensrÿche, and Metal Church. By 1988, the metal scene had faded, and The Rocket’s focus shifted to covering the pre-grunge local alternative rock bands. Dawn Anderson states that in 1988, long before any other publication took notice of them, Soundgarden and Nirvana were Rocket cover stars.[138] In 1991, The Rocket expanded to a Portland, Oregon edition.

Fiction

Grunge lit is an Australian literary genre of fictional or semi-autobiographical writing in the early 1990s about young adults living in an "inner cit[y]" "...world of disintegrating futures where the only relief from...boredom was through a nihilistic pursuit of sex, violence, drugs and alcohol".[139] Often the central characters are disfranchised, alienated, and lacking drive and determination beyond the desire to satisfy their basic needs. It was typically written by "new, young authors"[139] who examined "gritty, dirty, real existences"[139] of everyday characters. It has been described as both a sub-set of dirty realism and an offshoot of Generation X literature.[140] Stuart Glover states that the term "grunge lit" takes the term "grunge" from the "late 80’s and early 90’s—...Seattle [grunge] bands".[141] Glover states that the term "grunge lit" was mainly a marketing term used by publishing companies; he states that most of the authors who have been categorized as "grunge lit" writers reject the label.[141] The Australian fiction authors McGahan, McGregor and Tsiolkas criticized the "homogenizing effect" of conflating such a different group of writers.[139] Tsiolkas called the "grunge lit" term a "media creation".[139]

History

1980–1985: Roots, predecessors, and influences

Grunge's sound partly resulted from Seattle's isolation from other music scenes. As Sub Pop's Jonathan Poneman noted, "Seattle was a perfect example of a secondary city with an active music scene that was completely ignored by an American media fixated on Los Angeles and New York [City]."[142] Mark Arm claimed that the isolation meant, "this one corner of the map was being really inbred and ripping off each other's ideas".[143] Seattle "...was a remote and provincial city" in the 1980s; Bruce Pavitt states that the city was "...very working class", a place of "deprivation", and so the scene's "...whole aesthetic – work clothes, thriftstore truckers’ hats, pawnshop guitars" was not just a style, it was done because Seattle "...was very poor."[144] Indeed, when "...Nevermind reached number one in the U.S. charts, Cobain was living in a car." [144]

Bands began to mix metal and punk in the Seattle music scene around 1984, with much of the credit for this fusion going to The U-Men.[145] However, some critics have noted that in spite of The U-Men's canonical place as original grunge progenitors, that their sound was less indebted to heavy metal and much more akin to post-punk. However the unique idiosyncrasy of the band may have been the bigger inspiration, more than the aesthetics themselves.[146] Soon Seattle had a growing and "varied music scene" and "diverse urban personality" expressed by local "post-punk garage bands".[26] Grunge evolved from the local punk rock scene, and was inspired by bands such as The Fartz, The U-Men, 10 Minute Warning, The Accüsed, and the Fastbacks.[29] Additionally, the slow, heavy, and sludgy style of the Melvins was a significant influence on the grunge sound.[147] Roy Shuker states that grunge's success built on the "foundations...laid throughout the 1980s by earlier alternative music scenes."[148] Shuker states that music critics "...emphasized the perceived purity and authenticity of the Seattle scene.[148]

Outside the Pacific Northwest, a number of artists and music scenes influenced grunge. Alternative rock bands from the Northeastern United States, including Sonic Youth, Pixies, Pavement, and Dinosaur Jr., are important influences on the genre. Through their patronage of Seattle bands, Sonic Youth "inadvertently nurtured" the grunge scene, and reinforced the fiercely independent attitudes of its musicians.[149] The raw, distorted and feedback-intensive sound of some noise rock bands such as Scratch Acid, the Butthole Surfers,[79][150] The Jesus Lizard, Killdozer, Silverfish and Flipper, a band known for its slowed-down and murky "noise punk".

Several Australian bands, including The Scientists, Cosmic Psychos and Feedtime, are cited as precursors to grunge, their music influencing the Seattle scene through the college radio broadcasts of Sub Pop founder Jonathan Poneman and members of Mudhoney.[151][152] The influence of Pixies on Nirvana was noted by Kurt Cobain, who commented in a Rolling Stone interview, "I connected with that band so heavily that I should have been in that band—or at least a Pixies cover band. We used their sense of dynamics, being soft and quiet and then loud and hard."[153] In August 1997, in an interview with Guitar World, Dave Grohl said: "From Kurt, Krist [Novoselic] and I liking the Knack, Bay City Rollers, Beatles and Abba just as much as we liked Flipper and Black Flag...You listen to any Pixies record and it's all over there. Or even Black Sabbath's "War Pigs"-it's there: the power of the dynamic. We just sort of abused it with pop songs and got sick with it."[154]

Aside from the genre's punk and alternative rock roots, many grunge bands were equally influenced by heavy metal of the early 1970s. Clinton Heylin, author of Babylon's Burning: From Punk to Grunge, cited Black Sabbath as "perhaps the most ubiquitous pre-punk influence on the northwest scene".[155] Black Sabbath played a role in shaping the grunge sound, through their own records and the records they inspired.[156] Musicologist Bob Gulla asserted that Black Sabbath's sound "shows up in virtually all of grunge's most popular bands, including Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Alice in Chains".[157] The influence of Led Zeppelin is also evident, particularly in the work of Soundgarden, whom Q magazine noted were "in thrall to '70s rock, but contemptuous of the genre's overt sexism and machismo".[158] Jon Wiederhorn of Guitar World wrote: "So what exactly is grunge?...Picture a supergroup made up of Creedence Clearwater Revival, Black Sabbath and the Stooges, and you're pretty close."[159] Catherine Strong states that grunge's strongest metal influence was thrash metal, which had a tradition of "equality with the audience", based on the notion that "anyone could start a band" (a way of thinking also shared by US hardcore punk, which Strong also cites as an influence on grunge) which was also taken up by grunge bands.[14] Strong states that grunge musicians were opposed to the then-popular "hair metal" bands.[14]

Strong states that "...sections of what was [US] hardcore became known as grunge." [14] Seattle songwriter Jeff Stetson states that "[t]here is no real difference...between Punk and Grunge." [22] Like punk bands, grunge groups were "embraced as back-to-basics rock ‘n’ roll bands which reminded the public that the music was supposed to be raw and raunchy", and they were a response to "bloated and over-the-top...progressive rock...or "not seriou[s groups] like the hair bands of the ‘80s."[89] One example of the influence of US hardcore on grunge is the impact that the Los Angeles hardcore punk band Black Flag had on grunge. Black Flag's 1984 record My War, on which the band combined heavy metal with their traditional sound, made a strong impact in Seattle. Mudhoney's Steve Turner commented, "A lot of other people around the country hated the fact that Black Flag slowed down...but up here it was really great...we were like 'Yay!' They were weird and fucked-up sounding."[160] Turner explained grunge's integration of metal influences, noting, "Hard rock and metal was never that much of an enemy of punk like it was for other scenes. Here, it was like, 'There's only twenty people here, you can't really find a group to hate.'" Charles R. Cross states that grunge was the "...culmination of twenty years of punk rock" development.[25] Cross states that the bands most representing the grunge genre were Seattle bands Blood Circus, TAD, and Mudhoney and Sub Pop's Denver band The Fluid; he states that Nirvana, with its pop influences and blend of Sonic Youth and Cheap Trick, was lighter-sounding than bands like Blood Circus.[25]

After Neil Young played a few concerts with Pearl Jam and recorded the album Mirror Ball with them, some members of the media gave him the title "Godfather of Grunge". This was grounded not only in his work with his band Crazy Horse and his regular use of distorted guitar—most notably on the album Rust Never Sleeps—but also his dress and persona.[161] A similarly influential yet often overlooked album is Neurotica by Redd Kross, about which Jonathan Poneman said, "Neurotica was a life changer for me and for a lot of people in the Seattle music community."[162]

The context for the development of the Seattle grunge scene was a "..golden age of failure, a time when a swath of American youth embraced the...vices of indolence and lack of motivation".[144] The "...idlers of Generation X [were] trying to forestall the dread day of corporate enrollment" and embrace the "cult of the loser"; indeed Nirvana's 1991 song "Smells Like Teen Spirit" "...opens with Cobain intoning 'It’s fun to lose.'"[144] The "grunge credo was more about a death by slow suffocation", a "resistance through withdrawal" from the world.[163] Rupa Huq calls grunge "unrelentingly white" in "timbre and texture".[164] Robert Loss states that while the grunge scene was more welcoming to women than the glam metal world, and while grunge "...endeavoured to be more accepting of ethnic and cultural difference, it was overwhelmingly white"; he states that hip hop music artists such as Jay-Z had way more "crossover" appeal to listeners of different races.[24]

1985–1989: Early development

In 1985, the band Green River released their debut EP Come on Down, which is cited by many as being the very first grunge record.[165] Another seminal release in the development of grunge was the Deep Six compilation, released by C/Z Records in 1986. The record featured multiple tracks by six bands: Green River, Soundgarden, Melvins, Malfunkshun, Skin Yard, and The U-Men. For many of them it was their first appearance on record. The artists had "a mostly heavy, aggressive sound that melded the slower tempos of heavy metal with the intensity of hardcore". The recording process was low-budget; each band was given four hours of studio time. As Jack Endino recalled, "People just said, 'Well, what kind of music is this? This isn't metal, it's not punk, What is it?' [...] People went 'Eureka! These bands all have something in common.'"[160] Later that year Bruce Pavitt released the Sub Pop 100 compilation and Green River's Dry As a Bone EP as part of his new label, Sub Pop. An early Sub Pop catalog described the Green River EP as "ultra-loose GRUNGE that destroyed the morals of a generation".[166] Sub Pop's Bruce Pavitt and Jonathan Poneman, inspired by other regional music scenes in music history, worked to ensure that their label projected a "Seattle sound", reinforced by a similar style of production and album packaging. While music writer Michael Azerrad acknowledged that early grunge bands like Mudhoney, Soundgarden, and Tad had disparate sounds, he noted "to the objective observer, there were some distinct similarities."[167]

Early grunge concerts were sparsely attended (many by fewer than a dozen people) but Sub Pop photographer Charles Peterson's pictures helped create the impression that such concerts were major events.[168] Mudhoney, which was formed by former members of Green River, served as the flagship band of Sub Pop during their entire time with the label and spearheaded the Seattle grunge movement.[169] Other record labels in the Pacific Northwest that helped promote grunge included C/Z Records, Estrus Records, EMpTy Records and PopLlama Records.[29]

Grunge attracted media attention in the United Kingdom after Pavitt and Poneman asked journalist Everett True from the British magazine Melody Maker to write an article on the local music scene. This exposure helped to make grunge known outside of the local area during the late 1980s and drew more people to local shows.[29] The appeal of grunge to the music press was that it "promised the return to a notion of a regional, authorial vision for American rock".[170] Grunge's popularity in the underground music scene was such that bands began to move to Seattle and approximate the look and sound of the original grunge bands. Mudhoney's Steve Turner said, "It was really bad. Pretend bands were popping up here, things weren't coming from where we were coming from."[171] As a reaction, many grunge bands diversified their sound, with Nirvana and Tad in particular creating more melodic songs.[172] Dawn Anderson of the Seattle fanzine Backlash recalled that by 1990 many locals had tired of the hype surrounding the Seattle scene and hoped that media exposure had dissipated.[29]

Chris Dubrow from The Guardian states that in the late 1980s, Australia's "sticky-floored...alternative pub scene" in seedy inner-city areas produced grunge bands with "raw and awkward energy" such as The Scientists, X, Beasts of Bourbon, feedtime, Cosmic Psychos and Lubricated Goat.[173] Dubrow said "Cobain...admitted the Australian wave was a big influence" on his music.[173] Everett True states that "[t]here's more of an argument to be had for grunge beginning in Australia with the Scientists and their scrawny punk ilk."[6]

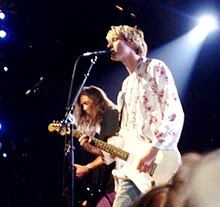

Early–mid 1990s: Mainstream success

Grunge bands had made inroads to the musical mainstream in the late 1980s. Soundgarden was the first grunge band to sign to a major label when they joined the roster of A&M Records in 1989. Soundgarden, along with other major label signings Alice in Chains and Screaming Trees, performed "okay" with their initial major label releases, according to Jack Endino.[29] Nirvana, originally from Aberdeen, Washington, was also courted by major labels, while releasing its first album Bleach in 1989. Nirvana got signed by Geffen Records in 1990. In September 1991, Nirvana released its major label debut, Nevermind. The album was at best hoped to be a minor success on par with Sonic Youth's Goo, which Geffen had released a year earlier.[174] It was the release of the album's first single "Smells Like Teen Spirit" that "marked the instigation of the grunge music phenomenon". Due to constant airplay of the song's music video on MTV, Nevermind was selling 400,000 copies a week by Christmas 1991.[175] In January 1992, Nevermind replaced pop superstar Michael Jackson's Dangerous at number one on the Billboard 200.[176] Nevermind was certified diamond by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) in 1999.[177]

The success of Nevermind surprised the music industry. Nevermind not only popularized grunge, but also established "the cultural and commercial viability of alternative rock in general."[178] Michael Azerrad asserted that Nevermind symbolized "a sea-change in rock music" in which the glam metal that had dominated rock music at that time fell out of favor in the face of music that was perceived as authentic and culturally relevant.[179] Grunge made it possible for genres thought to be of a niche audience, no matter how radical, to prove their marketability and be co-opted by the mainstream, cementing the formation of an individualist, fragmented culture.[180] Other grunge bands subsequently replicated Nirvana's success. Pearl Jam, which featured former Mother Love Bone members Jeff Ament and Stone Gossard, had released its debut album Ten in August 1991, a month before Nevermind, but album sales only picked up a year later. By the second half of 1992 Ten had become a breakthrough success, being certified gold and reaching number two on the Billboard charts.[181] Ten by Pearl Jam was certified 13x platinum by the RIAA.[182]

The band Soundgarden's album Badmotorfinger and the band Alice in Chains' album Dirt, along with the band Temple of the Dog's self-titled album, a collaboration featuring members of Pearl Jam and Soundgarden, were also among the 100 top selling albums of 1992.[183] The popular breakthrough of these grunge bands prompted Rolling Stone to nickname Seattle "the new Liverpool".[78] Major record labels signed most of the prominent grunge bands in Seattle, while a second influx of bands moved to the city in hopes of success.[184] The grunge scene was the backdrop in the 1992 Cameron Crowe film Singles. There were several small roles, performances, and cameos in the film by popular Seattle grunge bands including Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and Alice in Chains. Filmed in and around Seattle in 1991, the film was not released until 1992 during the height of grunge popularity.[78]

The popularity of grunge resulted in a large interest in the Seattle music scene's perceived cultural traits. While the Seattle music scene in the late 1980s and early 1990s in actuality consisted of various styles and genres of music, its representation in the media "served to depict Seattle as a music 'community' in which the focus was upon the ongoing exploration of one musical idiom, namely grunge".[185] The fashion industry marketed "grunge fashion" to consumers, charging premium prices for items such as knit ski hats and plaid shirts. Critics asserted that advertising was co-opting elements of grunge and turning it into a fad. Entertainment Weekly commented in a 1993 article, "There hasn't been this kind of exploitation of a subculture since the media discovered hippies in the '60s".[186] Marketers used the "grunge" concept to sell grunge air freshener, grunge hair gel and even CDs of "easy-listening music" called "grunge light".[25] The New York Times compared the "grunging of America" to the mass-marketing of punk rock, disco, and hip hop in previous years.[78] Ironically the New York Times was tricked into printing a fake list of slang terms that were supposedly used in the grunge scene; often referred to as the grunge speak hoax. This media hype surrounding grunge was documented in the 1996 documentary Hype!.[29] As mass media began to use the term "grunge" in any news story about the key bands, Seattle scene members began to refer to the term as "the G-word".[25]

A backlash against grunge began to develop in Seattle; in late 1992, Jonathan Poneman said that in the city, "All things grunge are treated with the utmost cynicism and amusement [. . .] Because the whole thing is a fabricated movement and always has been."[78] Many grunge artists were uncomfortable with their success and the resulting attention it brought. Nirvana's Kurt Cobain told Michael Azerrad, "Famous is the last thing I wanted to be."[187] Pearl Jam also felt the burden of success, with much of the attention falling on frontman Eddie Vedder.[188]

Nirvana's follow-up album In Utero (1993) featured an intentionally abrasive album that Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic described as a "wild aggressive sound, a true alternative record".[189] Nevertheless, upon its release in September 1993, In Utero topped the Billboard charts.[190] In 1996, In Utero was certified 5x platinum by the RIAA.[191] Pearl Jam also continued to perform well commercially with its second album, Vs. (1993). The album sold a record 950,378 copies in its first week of release, topped the Billboard charts, and outperformed all other entries in the top ten that week combined.[192] In 1993, the grunge band Candlebox released their self-titled album, which was certified 4x platinum by the RIAA.[193] In February 1994, Alice in Chains' EP, Jar of Flies peaked at number 1 on the Billboard 200 album chart.[194] Soundgarden's album Superunknown, which was also released in 1994, peaked at number 1 on the Billboard 200 chart,[195] and was certified 5x platinum by the RIAA.[196] In 1995, Alice in Chains' self-titled album became their second number 1 album on the Billboard 200,[194] and was certified 2x platinum.[197]

At the height of grunge's commercial success in the early 1990s, the commercial success of grunge put record labels on a nationwide search for undiscovered talent to promote. This included San Diego, California-based Stone Temple Pilots,[198] Texas-based Tripping Daisy[3][199] and Toadies,[200][201][202] Paw,[203] Chicago-based Veruca Salt,[203] and Australian band Silverchair, bands whose early work continues to be identified broadly (if not in Seattle itself) as "grunge". In 2014, Paste ranked Veruca Salt's "All Hail Me" #39 and Silverchair's "Tomorrow" #45 on their list of the 50 best grunge songs of all time.[203] Loudwire named Stone Temple Pilots one of the ten best grunge bands of all time.[198] Grunge bands outside of the United States emerged in several countries. In Canada, Eric's Trip, the first Canadian band signed by the Sub Pop label, has been classified as grunge [204] and Nickelback's debut album was considered to be grunge. Silverchair achieved mainstream success in the 1990s; the band's song "Tomorrow" went to number 22 on the Radio Songs chart in September 1995[205] and the band's debut album Frogstomp, released in June 1995, was certified 2x platinum by the RIAA in February 1996.[206]

During this period, grunge bands that were not from Seattle were often panned by critics, who accused them of being bandwagon-jumpers. Grunge band Stone Temple Pilots in particular fell victim to this. In a January 1994 Rolling Stone poll, Stone Temple Pilots was simultaneously voted "Best New Band" by Rolling Stone's readers and "Worst New Band" by the magazine's music critics, highlighting the disparity between critics and fans.[207] Stone Temple Pilots became very popular; their album Core was certified 8x platinum by RIAA[208] and their album Purple was certified 6x platinum by the RIAA.[209] The British grunge band Bush released their debut album Sixteen Stone in 1994.[210] In a review of their second album Razorblade Suitcase, Rolling Stone criticized the album and called Bush "the most successful and shameless mimics of Nirvana's music".[211] In the book Fargo Rock City: A Heavy Metal Odyssey in Rural North Dakota, Chuck Klosterman wrote, "Bush was a good band who just happened to signal the beginning of the end; ultimately, they would become the grunge Warrant".[212] In the book Accidental Revolution: The Story of Grunge, Kyle Anderson wrote:

"The twelve songs on Sixteen Stone sound exactly like what grunge is supposed to sound like, while the whole point of grunge was that it didn't really sound like anything, including itself. Just consider how many different bands and styles of music have been shoved under the "grunge" header in this discography alone, and you realize that grunge is probably the most ill-defined genre of music in history."[213]

Mid–late 1990s: Decline of mainstream popularity

End of subculture

A number of factors contributed to grunge's decline in prominence. Critics and historians do not agree on the exact point that grunge ended.[214] Catherine Strong states that "...at the end of 1993...[,]grunge had become unstable, and was entering the first stages of being killed off"; she points out that the "...scene had become so successful" and widely known that "imitators had begun to enter the field".[215] Paste magazine states by 1994, grunge "...was fading fast", with "...Pearl Jam retreating from the spotlight as fast as they could; Alice in Chains, Stone Temple Pilots and hordes of others were battling horrid drug addictions and struggling for survival."[4] In Grunge: Seattle, Justin Henderson states that the "downward spiral" began in mid-1994, as the influx of major label money into the scene changed the culture and it had "nowhere to go but down"; he states the death of Hole bassist Kristen Pfaff on June 16, 1994, from a heroin overdose, was "another nail in grunge's coffin." [216]

In Jason Heller's 2013 article "Did grunge really matter?", in A.V. CLUB, he stated that Nirvana's In Utero (September 1993) was "grunge’s death knell. As soon as Cobain grumbled, "Teenage angst has paid off well / Now I’m bored and old," it was all over."[217] Heller states that after Cobain's death in 1994, the "hypocrisy" in the grunge of the time "became ...glaring" and "idealism became embarrassing", with the result being that "grunge became the new [mainstream] Aerosmith".[217] Heller states that "grunge became an evolutionary dead end", because "it stood for nothing and was built on nothing, and that ethos of negation was all it was about."[217]

During the mid-1990s many grunge bands broke up or became less visible. Kurt Cobain, labeled by Time as "the John Lennon of the swinging Northwest", appeared "unusually tortured by success" and struggled with an addiction to heroin. Rumors surfaced in early 1994 that Cobain suffered a drug overdose and that Nirvana was breaking up.[218] On April 8, 1994, Cobain was found dead in his Seattle home from an apparently self-inflicted gunshot wound; Nirvana summarily disbanded. Cobain's suicide "served as a catalyst for grunge’s...demise", because it "...deflated the energy from grunge and provided the opening for saccharine and corporate-formulated music to regain" its lost footing."[219]

That same year Pearl Jam canceled its summer tour in protest of ticket vendor Ticketmaster's unfair business practices.[220] Pearl Jam then began a boycott of the company; however, Pearl Jam's initiative to play only at non-Ticketmaster venues effectively, with a few exceptions, prevented the band from playing shows in the United States for the next three years.[221] In 1996, Alice in Chains gave their final performances with their ailing and estranged lead singer, Layne Staley,[222] who subsequently died from an overdose of cocaine and heroin in 2002.[223] In 1996, Soundgarden and Screaming Trees released their final studio albums of the 1990s, Down on the Upside[224] and Dust,[225] respectively. Strong states that Roy Shuker and Stout have written that the "...end of grunge" can be seen as being "...as late as the breakup of Soundgarden in 1997".[215]

Post-grunge

During the latter half of the 1990s, grunge was supplanted by post-grunge, which remained commercially viable into the start of the 21st century. Post-grunge "...transformed the thick guitar sounds and candid lyrical themes of the Seattle bands into an accessible, often uplifting mainstream aesthetic".[226] These artists were seen as lacking the underground roots of grunge and were largely influenced by what grunge had become, namely "a wildly popular form of inward-looking, serious-minded hard rock". Post-grunge was a more commercially viable genre that tempered the distorted guitars of grunge with polished, radio-ready production.[227][228] When grunge became a mainstream genre, major labels started signing bands that sounded similar to these bands' sonic identities. Bands labeled as post-grunge that emerged when grunge was mainstream such as Bush, Candlebox and Collective Soul all are noted for emulating the sound of the bands that launched grunge into the mainstream.[227] Although the bands Bush[229][230][231] and Candlebox[232] have been categorized as grunge, both bands have been largely categorized as post-grunge, too.[227]

In 1995, SPIN writer Charles Aaron stated that with grunge "spent", pop punk in a slump, Britpop a "giddy memory" and album-oriented rock over, the music industry turned to "Corporate[-produced] Alternative", which he calls "soundalike fake grunge" or "scrunge".[233] Bands Aaron lists as "scrunge" groups include: Better Than Ezra; Bush; Collective Soul; Garbage; Hootie & the Blowfish; Hum; Silverchair; Sponge; Tripping Daisy; Jennifer Trynin and Weezer; Aaron includes the Foo Fighters in his list, but states that Dave Grohl avoided becoming a "scrunge fall gu[y]" by combining 1980s hardcore punk with 1970s arena trash music in his post-Nirvana group.[233]

Bands described as grunge like Bush[229][230][231] and Candlebox[232] also have been largely categorized as post-grunge.[228] These two bands became popular after 1992.[228] Tim Grierson of About.com described bands such as Bush and Candlebox, writing:

"Perhaps not surprisingly, because these bands seemed to be merely ripping off a trendy sound, critics dismissed them as bandwagon-jumpers. Tellingly, these bands were labeled almost pejoratively as "post-grunge," suggesting that rather than being a musical movement in their own right, they were just a calculated, cynical response to a legitimate stylistic shift in rock music."[227]

Other bands categorized as post-grunge that emerged when Bush and Candlebox became popular include Collective Soul[227] and Live.[234] Post-grunge still was popular in the late 1990s and early 2000s with newer bands such as Creed, Nickelback, 3 Doors Down and Puddle of Mudd.[227] Other post-grunge bands include Foo Fighters, Staind and Matchbox Twenty. These post-grunge artists were criticized for their commercialized sound as well as their "worldview built around the comforts of community and romantic relationships", as opposed to grunge's lyrical exploration of "troubling issues such as suicide, societal hypocrisy and drug addiction."[227] Adam Steininger criticized post-grunge bands' "diluted ditties filled with watered-down lyrics, all seemingly revolving around suffering through romance."[235] Criticizing many bands that have been described as post-grunge, Steininger criticized Candlebox for their "pop-filled" sound, focus on "love lyrics, and writing songs without "versatility and creativity; Three Days Grace for their "diluted" and "radio-friendly music"; 3 Doors Down for focusing on "...snagging hit singles instead of creating quality albums"; Finger Eleven for going in a "pop rock" direction; Bush's "random phrasings of nonsense"; Live's "pseudo pop poetry" that "strangled the essence of grunge", Puddle of Mudd's "watered down post-grunge sound"; Lifehouse, for tearing "...down ...grunge's sound and groundbreaking structure to appeal more to the masses"; and Nickelback, which he calls the "featherweight...punching bags of post-grunge" whose music is "dull as dishwater".[235]

Reaction by Britpop

Conversely, another rock genre, Britpop, emerged in part as a reaction against the dominance of grunge in the United Kingdom. In contrast to the dourness of grunge, Britpop was defined by "youthful exuberance and desire for recognition".[236] The leading Britpop bands, "Blur and Oasis[,] exist[ed] as reactionary forces to [grunge's] eternal downcast glare."[237] Britpop artists' new approach was inspired by Blur's tour of the United States in the spring of 1992. Justine Frischmann, formerly of Suede and leader of Elastica (and at the time in a relationship with Damon Albarn) explained, "Damon and I felt like we were in the thick of it at that point ... it occurred to us that Nirvana were out there, and people were very interested in American music, and there should be some sort of manifesto for the return of Britishness."[238]

Britpop artists were vocal about their disdain for grunge. In a 1993 NME interview, Damon Albarn of Britpop band Blur agreed with interviewer John Harris' assertion that Blur was an "anti-grunge band", and said, "Well, that's good. If punk was about getting rid of hippies, then I'm getting rid of grunge" (ironically Kurt Cobain once cited Blur as his favorite band).[239] Noel Gallagher of Oasis, while a fan of Nirvana, wrote music that refuted the pessimistic nature of grunge. Gallagher noted in 2006 that the 1994 Oasis single "Live Forever" "was written in the middle of grunge and all that, and I remember Nirvana had a tune called 'I Hate Myself and I Want to Die,' and I was like...'Well, I'm not fucking having that.' As much as I fucking like him [Cobain] and all that shit, I'm not having that. I can't have people like that coming over here, on smack [heroin], fucking saying that they hate themselves and they wanna die. That's fucking rubbish."[240]

2000s–2010s: Revival

Many major grunge bands have continued recording and touring with success in the 2000s and 2010s. Perhaps the most notable grunge act of the 21st century has been Pearl Jam. In 2006 Rolling Stone writer Brian Hiatt described Pearl Jam as having "spent much of the past decade deliberately tearing apart their own fame", he noted the band developed a loyal concert following akin to that of the Grateful Dead.[241] They saw a return to wide commercial success with 2006's Pearl Jam, 2009's Backspacer and 2013's Lightning Bolt.[242] Alice In Chains reformed for a handful of reunion dates in 2005 with several different vocalists replacing Layne Staley. Eventually settling on William Duvall as Staley's replacement, in 2009 they released Black Gives Way to Blue, their first record in 15 years. The band's 2013 release, The Devil Put Dinosaurs Here, reached number 2 on the Billboard 200.[243] Soundgarden reformed in 2010 and released their album King Animal two years later which reached the top five of the national albums charts in Denmark, New Zealand, and the United States.[244] Matt Cameron and Ben Shepherd joined Alain Johannes (Queens of the Stone Age, Eleven), Mark Lanegan (Screaming Trees, Queens of the Stone Age) and Dimitri Coats (Off!) to form side project Ten Commandos in 2016.[245]