High-fructose corn syrup

High-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) (also called glucose-fructose, isoglucose and glucose-fructose syrup[1][2]) is a sweetener made from corn starch that has been processed by glucose isomerase to convert some of its glucose into fructose. HFCS was first marketed in the early 1970s by the Clinton Corn Processing Company, together with the Japanese Agency of Industrial Science and Technology where the enzyme was discovered in 1965.[3]: 5

As a sweetener, HFCS is often compared to granulated sugar, but manufacturing advantages of HFCS over sugar include that it is easier to handle and more cost-effective.[4] The United States Food and Drug Administration has determined that HFCS is a safe ingredient for food and beverage manufacturing.[5] There is debate over whether HFCS presents greater health risks than other sweeteners.[6] Uses and exports of HFCS from American producers have continued to grow during the early 21st century.[7]

Apart from comparisons between HFCS and table sugar, there is some evidence that the overconsumption of added sugar in any form, including HFCS, is a major health problem, especially for onset of obesity.[4][8][9] Consuming added sugars, particularly as sweetened soft drinks, is strongly linked to weight gain.[4][10] The World Health Organization has recommended that people limit their consumption of added sugars to 10% of calories, but experts say that typical consumption of empty calories in the United States is nearly twice that level.[10]

Food

In the U.S., HFCS is among the sweeteners that mostly replaced sucrose (table sugar) in the food industry.[11] Factors in the rise of HFCS use include production quotas of domestic sugar, import tariff on foreign sugar, and subsidies of U.S. corn, raising the price of sucrose and lowering that of HFCS, making it cheapest for many sweetener applications.[12][13] The relative sweetness of HFCS 55, used most commonly in soft drinks, is comparable to sucrose.[14] HFCS (and/or standard corn syrup) is the primary ingredient in most brands of commercial "pancake syrup", as a less expensive substitute for maple syrup.[15]

Because of its similar sugar profile and lower price, HFCS has been used illegally to "stretch" honey. Assays to detect adulteration with HFCS use differential scanning calorimetry and other advanced testing methods.[16][17]

Production

Process

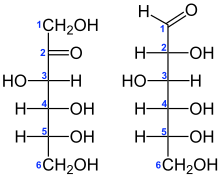

In the contemporary process, corn is milled to extract corn starch and an "acid-enzyme" process is used, in which the corn-starch solution is acidified to begin breaking up the existing carbohydrates.[18] It is necessary to carry out the extraction process in the presence of mercuric chloride (0.01 M) in order to inhibit endogenous starch-degrading enzymes.[19]: 374–376 High-temperature enzymes are added to further metabolize the starch and convert the resulting sugars to fructose.[18]: 808–813 The first enzyme added is alpha-amylase, which breaks the long chains down into shorter sugar chains – oligosaccharides. Glucoamylase is mixed in and converts them to glucose; the resulting solution is filtered to remove protein, then using activated carbon, and then demineralized using ion-exchange resins. The purified solution is then run over immobilized xylose isomerase, which turns the sugars to ~50–52% glucose with some unconverted oligosaccharides and 42% fructose (HFCS 42), and again demineralized and again purified using activated carbon. Some is processed into HFCS 90 by liquid chromatography, then mixed with HFCS 42 to form HFCS 55. The enzymes used in the process are made by microbial fermentation.[18]: 808–813 [3]: 20–22

Composition and varieties

HFCS is 24% water, the rest being mainly fructose and glucose with 0–5% unprocessed glucose oligomers.[20] There are several varieties of HFCS, numbered by the percentage of fructose they contain:

- HFCS 42 (≈42% fructose if water were removed) is used in beverages, processed foods, cereals, and baked goods.[21]

- HFCS 55 is mostly used in soft drinks.

- HFCS 65 is used in soft drinks dispensed by Coca-Cola Freestyle machines.[22]

- HFCS 90 has some niche uses [23] but is mainly mixed with HFCS 42 to make HFCS 55.

History

Commercial production of corn syrup began in 1864.[3]: 17 In the late 1950s, scientists at Clinton Corn Processing Company of Clinton, Iowa tried to turn glucose from corn starch into fructose, but the process was not scalable.[3]: 17 [24] In 1965–1970 Yoshiyuki Takasaki, at the Japanese National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) developed a heat-stable xylose isomerase enzyme from yeast. In 1967, the Clinton Corn Processing Company obtained an exclusive license to a manufacture glucose isomerase derived from Streptomyces bacteria and began shipping an early version of HFCS in February 1967.[3]: 140 In 1983, the FDA approved HFCS as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS), and that decision was reaffirmed in 1996[25]

Prior to the development of the worldwide sugar industry, dietary fructose was limited to only a few items. Milk, meats, and most vegetables, the staples of many early diets, have no fructose, and only 5–10% fructose by weight is found in fruits such as grapes, apples, and blueberries. Most traditional dried fruits, however, contain about 50% fructose. From 1970 to 2000, there was a 25% increase in "added sugars" in the U.S.[26] After being classified as generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1976,[27] HFCS began to replace sucrose as the main sweetener of soft drinks in the United States. At the same time, rates of obesity rose. That correlation, in combination with laboratory research and epidemiological studies that suggested a link between consuming large amounts of fructose and changes to various proxy health measures, including elevated blood triglycerides, size and type of low-density lipoproteins, uric acid levels, and weight, raised concerns about health effects of HFCS itself.[20]

United States

In the U.S., sugar tariffs and quotas keep imported sugar at up to twice the global price since 1797,[28] while subsidies to corn growers cheapen the primary ingredient in HFCS, corn. Industrial users looking for cheaper replacements rapidly adopted HFCS in the 1970s.[29][30]

HFCS is easier to handle than granulated sucrose, although some sucrose is transported as solution. Unlike sucrose, HFCS cannot be hydrolyzed, but the free fructose in HFCS may produce hydroxymethylfurfural when stored at high temperatures; these differences are most prominent in acidic beverages.[31] Soft drink makers such as Coca-Cola and Pepsi continue to use sugar in other nations but transitioned to HFCS for U.S. markets in 1980 before completely switching over in 1984.[32] Large corporations, such as Archer Daniels Midland, lobby for the continuation of government corn subsidies.[33]

Consumption of HFCS in the U.S. has declined since it peaked at 37.5 lb (17.0 kg) per person in 1999. The average American consumed approximately 27.1 lb (12.3 kg) of HFCS in 2012,[34] versus 39.0 lb (17.7 kg) of refined cane and beet sugar.[35][36] This decrease in domestic consumption of HFCS resulted in a push in exporting of the product. In 2014, exports of HFCS were valued at $436 million, a decrease of 21% in one year, with Mexico receiving about 75% of the export volume.[7]

In 2010, the Corn Refiners Association petitioned the FDA to call HFCS "corn sugar", but the petition was denied.[37]

European Union

In the European Union (EU), HFCS, known as isoglucose in sugar regime, is subject to a production quota. In 2005, this quota was set at 303,000 tons; in comparison, the EU produced an average of 18.6 million tons of sugar annually between 1999 and 2001.[38]

Japan

In Japan, HFCS is manufactured mostly from imported U.S. corn, and the output is regulated by the government. For the period from 2007 to 2012, HFCS had a 27–30% share of the Japanese sweetener market.[39]

Health

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,176 kJ (281 kcal) |

76 g | |

| Dietary fiber | 0 g |

0 g | |

0 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 1% 0.019 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 0% 0 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 0% 0.011 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 1% 0.024 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 0% 0 μg |

| Vitamin C | 0% 0 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 0% 6 mg |

| Iron | 2% 0.42 mg |

| Magnesium | 0% 2 mg |

| Phosphorus | 0% 4 mg |

| Potassium | 0% 0 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 2 mg |

| Zinc | 2% 0.22 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 24 g |

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[40] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[41] | |

Health concerns have been raised about a relationship between HFCS and metabolic disorders, and with regard to manufacturing contaminants. In general, however, the United States Food and Drug Administration has declared HFCS as a safe ingredient in food manufacturing, and there is no evidence that retail HFCS products contain harmful compounds or cause diseases.[4][5]

Nutrition

HFCS is composed of 76% carbohydrates and 24% water, containing no fat, no protein, and no essential nutrients in significant amounts (table). In a 100 gram serving, it supplies 281 Calories, whereas in one tablespoon of 19 grams, it supplies 53 Calories (table link).

Obesity and metabolic disorders

Sugars became a health concern among the American public in the early 1970s with the publication of John Yudkin's book, Pure, White and Deadly. The book claimed that simple sugars, an increasingly large part of the Western diet, were dangerous.[3]: 18 In the 1980s and 1990s were publications cautioning consumption of sucrose and of HFCS.[3]: 18 [3]: 18 [42] In subsequent interviews, two of the study's authors stated the article was distorted to place emphasis solely on HFCS when the actual issue was the overconsumption of any type of sugar.[43][44] While fructose absorption and modification by the intestines and liver does differ from glucose initially, the majority of the fructose molecules are converted to glucose or metabolized into byproducts identical to those produced by glucose metabolism. Consumption of moderate amounts of fructose has also been linked to positive outcomes, including reducing appetite if consumed before a meal, lower blood sugar increases compared to glucose, and (again compared to glucose) delaying exhaustion if consumed during exercise.[20]

In 2007, an expert panel assembled by the University of Maryland's Center for Food, Nutrition and Agriculture Policy reviewed the links between HFCS and obesity and concluded there was no ecological validity in the association between rising body mass indexes (a measure of obesity) and the consumption of HFCS. The panel stated that since the ratio of fructose to glucose had not changed substantially in the United States since the 1960s when HFCS was introduced, the changes in obesity rates were probably not due to HFCS specifically, but rather a greater consumption of calories overall.[45] In 2009 the American Medical Association published a review article on HFCS and concluded it was unlikely that HFCS contributed more to obesity or other health conditions than sucrose, and there was insufficient evidence to suggest warning about or restricting use of HFCS or other fructose-containing sweeteners in foods. The review did report that while some studies found direct associations between high intakes of fructose and other sugars and adverse health outcomes, including obesity and the metabolic syndrome, there was insufficient evidence to ban or restrict use of HFCS in the food supply or to require warning labels on products containing HFCS.[46]

Epidemiological research has suggested that the increase in metabolic disorders like obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is linked to increased consumption of sugars and/or calories in general and not due to any special effect of HFCS.[20][47][48] A 2014 systematic review found little evidence for an association between HFCS consumption and liver diseases, enzyme levels or fat content.[49] A 2012 review found that fructose did not appear to cause weight gain when it replaced other carbohydrates in diets with similar calories.[50] One study investigating HFCS as a possible contributor to diabetes and obesity states that, "As many of the metabolic consequences of a diet high in fructose-containing sugars in humans can also be observed with high-fat or high-glucose feeding, it is possible that excess calories may be the main culprit in the development of the metabolic syndrome."[51] Another study compared similar intakes of honey, white cane sugar, and HFCS, showing similar rises in both blood sugar level and triglycerides.[52] High fructose consumption has been linked to high levels of uric acid in the blood, though this is only thought to be a concern for patients with gout.[20]

Numerous agencies in the United States recommend reducing the consumption of all sugars, including HFCS, without singling it out as presenting extra concerns. The Mayo Clinic cites the American Heart Association's recommendation that women limit the added sugar in their diet to 100 calories a day (~6 teaspoons) and that men limit it to 150 calories a day (~9 teaspoons), noting that there is not enough evidence to support HFCS having more adverse health effects than excess consumption of any other type of sugar.[53][54] The United States departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services recommendations for a healthy diet state that consumption of all types of added sugars be reduced.[55]: p.27

People with fructose malabsorption should avoid foods containing HFCS.[56]

Safety and manufacturing concerns

Since 2014, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has declared HFCS to be safe as a food ingredient.[5] In 2015, production of HFCS in the United States was 8.5 million tons from some 500 million bushels of corn.[57]

One consumer concern about HFCS is that processing of corn is more complex than used for “simpler” or “more natural” sugars, such as fruit juice concentrates or agave nectar, but all sweetener products derived from raw materials involve similar processing steps of pulping, hydrolysis, enzyme treatment, and filtration, among other common steps of sweetener manufacturing from natural sources.[4][57][58] In the contemporary process to make HFCS, an "acid-enzyme" step is used in which the cornstarch solution is acidified to digest the existing carbohydrates, then enzymes are added to further metabolize the cornstarch and convert the resulting sugars to their constituents of fructose and glucose.[57][58] Analyses published in 2014 showed that HFCS content of fructose was consistent across samples from 80 randomly selected carbonated beverages sweetened with HFCS.[59]

One prior concern in manufacturing was whether HFCS contains reactive carbonyl compounds or advanced glycation end-products evolved during processing.[60] This concern was dismissed, however, with evidence that HFCS poses no dietary risk from these compounds.[4]

Through the early 21st Century, some factories manufacturing HFCS had used a chlor-alkali corn processing method which, in cases of applying mercury cell technology for digesting corn raw material, left trace residues of mercury in some batches of HFCS.[61] In a 2009 release,[62] The Corn Refiners Association stated that all factories in the American industry for manufacturing HFCS had used mercury-free processing over several previous years, making the prior report outdated.[61] As of 2017, the USDA, FDA and US Centers for Disease Control list HFCS as a safe food ingredient, and do not mention mercury as a safety concern in HFCS products.[5][57][63]

Other

Taste difference

Some countries, including Mexico, use sucrose, or table sugar, in soft drinks. In the U.S., soft drinks, including Coca-Cola, are typically made with HFCS. Some Americans seek out drinks such as Mexican Coca-Cola in ethnic groceries because they prefer the taste more than the HFCS-sweetened Coca-Cola.[64][65] Kosher Coca-Cola, sold in the U.S. around the Jewish holiday of Passover, also uses sucrose rather than HFCS and is highly sought after by people who prefer the original taste.[66] While these are simply opinions, a 2011 study further backed up the idea that people enjoy sucrose (table sugar) more than HFCS. The study, conducted by Michigan State University, included a 99-member panel that evaluated yogurt sweetened with sucrose (table sugar), HFCS, and different varieties of honey for likeness. The results showed that, overall, the panel enjoyed the yogurt with sucrose (table sugar) added more than those that contained HFCS or honey.[67]

Beekeeping

In apiculture in the United States, HFCS is a honey substitute for some managed honey bee colonies during times when nectar is in low supply.[68][69] However, when HFCS is heated to about 45 °C (113 °F), hydroxymethylfurfural, which is toxic to bees, can form from the breakdown of fructose.[70][71] Although some researchers cite honey substitution with HFCS as one factor among many for colony collapse disorder, there is no evidence that HFCS is the only cause.[68][69][72] Compared to hive honey, HFCS may be a deficiency in the diet for developing genes associated with protein metabolism and physiological benefits affecting bee health.[69]

Public relations

There are various public relations concerns with HFCS, including how the product is being advertised as well as it being labeled as "natural." More concerns include companies that have moved back to sucrose (table sugar) and a proposed name change from "high fructose corn syrup" to "corn sugar." In 2010, the Corn Refiners Association, or CRA, applied to allow HFCS to be renamed "corn sugar", but was rejected by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 2012.[73] The CRA has reportedly spent millions in public relation campaigns in an effort to portray HFCS in a positive light, sometimes without disclosing their involvement in the campaigns. For example, in 2009 the association paid the public relations firm Berman & Company $3.5 million to defend their products. An email sent out by a CRA staff member stated, "As you know, our sponsorship of this campaign remains confidential, [. . .] We are funding Berman & Company directly, not the Center for Consumer Freedom, which is running the ads. If asked, please feel free to state the following: 'The Corn Refiners Association is not funding the Center for Consumer Freedom.'"[74] This was one of several campaigns that the CRA chose not to disclose their involvement in.

McDonald's reported in August 2016 that, in a move to please health-conscious customers, they would be replacing all HFCS in their buns with sucrose (table sugar). In addition, they would also cut out preservatives and other artificial additives from their menu items. Marion Gross, senior vice president of McDonald's stated, "We know that they [consumers] don't feel good about high-fructose corn syrup so we're giving them what they're looking for instead." [75] Other companies such as Hunt's Ketchup, Gatorade, and Wheat Thins have also phased out HFCS, replacing it with conventional sugar (sucrose). Companies such as PepsiCo and Heinz have also released products that use sucrose (table sugar) in lieu of HFCS, although they still sell the original HFCS-sweetened versions as well.[76]

See also

References

- ^ European Starch Association. "Factsheet on Glucose Fructose Syrups and Isoglucose".

- ^ "Glucose-fructose syrup: How is it produced?". European Food Information Council (EUFIC). Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h White J. S. Sucrose, HFCS, and Fructose: History, Manufacture, Composition, Applications, and Production. Chapter 2 in J. M. Rippe (ed.), Fructose, High Fructose Corn Syrup, Sucrose and Health, Nutrition and Health. Springer Science+Business Media New York 2014. ISBN 9781489980779.

- ^ a b c d e f White, J. S. (2009). "Misconceptions about high-fructose corn syrup: Is it uniquely responsible for obesity, reactive dicarbonyl compounds, and advanced glycation endproducts?". Journal of Nutrition. 139 (6): 1219S–1227S. doi:10.3945/jn.108.097998. PMID 19386820.

- ^ a b c d "High Fructose Corn Syrup: Questions and Answers". US Food and Drug Administration. 5 November 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ Lindsay Abrams (27 November 2012). "Study: Countries That Use More High Fructose Corn Syrup Have More Diabetes". The Atlantic. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ a b "U.S. Exports of Corn-Based Products Continue to Climb". Foreign Agricultural Service, US Department of Agriculture. 21 January 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ Alexandra Sifferlin (29 January 2015). "This Is the No. 1 Driver of Diabetes and Obesity". Time. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ Juliana Bunim (27 October 2015). "Obese Children's Health Rapidly Improves With Sugar Reduction Unrelated to Calories". University of California San Francisco. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ a b Lindsay H Allen; Andrew Prentice (28 December 2012). Encyclopedia of Human Nutrition 3E. Academic Press. pp. 231–233. ISBN 978-0-12-384885-7. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ (Bray, 2004 & U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Sugar and Sweetener Yearbook series, Tables 50–52)

- ^ Pollan M (12 October 2003). "The (Agri)Cultural Contradictions Of Obesity". The New York Times.

- ^ Engber, Daniel (28 April 2009). "The decline and fall of high-fructose corn syrup". Slate Magazine. Slate.com. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ Hanover LM, White JS (1993). "Manufacturing, composition, and applications of fructose". Am J Clin Nutr. 58 (suppl 5): 724S–732S. PMID 8213603.

- ^ "5 Things You Need to Know About Maple Syrup". Retrieved 2016-09-29.

- ^ "Advances in Honey Adulteration Detection". Food Safety Magazine. 1974-08-12. Retrieved 2015-05-09.

- ^ Everstine K, Spink J, Kennedy S (April 2013). "Economically motivated adulteration (EMA) of food: common characteristics of EMA incidents". J Food Prot. 76 (4): 723–35. doi:10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-399. PMID 23575142.

Because the sugar profile of high-fructose corn syrup is similar to that of honey, high-fructose corn syrup was more difficult to detect until new tests were developed in the 1980s. Honey adulteration has continued to evolve to evade testing methodology, requiring continual updating of testing methods.

- ^ a b c Hobbs, Larry (2009). "21. Sweeteners from Starch: Production, Properties and Uses". In BeMiller, James N.; Whistler, Roy L. (eds.). Starch: chemistry and technology (3rd ed.). London: Academic Press/Elsevier. pp. 797–832. ISBN 978-0-12-746275-2.

- ^ Guzman-Maldonado, Horacio (1995). "Amylolytic Enzymes and Products Derived from Starch: A Review". Critical Review in Food Science and Nutrition. 35: 376–403.

- ^ a b c d e Rizkalla, S. W. (2010). "Health implications of fructose consumption: A review of recent data". Nutrition & Metabolism. 7: 82. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-7-82. PMC 2991323. PMID 21050460.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Sugar and Sweeteners: Background". United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. 14 November 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ "COCA COLA FREESTYLE DISPENSER Users Manual" (PDF). The Coca-Cola Company. 2010-03-23. pp. 4, 13. Retrieved 2016-08-12.

- ^ John S. White (2 December 2008). "HFCS: How sweet it is". Food Product Design. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ^ Marshall R. O.; Kooi E. R. (1957). "Enzymatic Conversion of d-Glucose to d-Fructose". Science. 125 (3249): 648–649. Bibcode:1957Sci...125..648M. doi:10.1126/science.125.3249.648. PMID 13421660.

- ^ High Fructose Corn Syrup A Guide for Consumers Policymakers and the Media (PDF). Grocery Manufacturers Association. 2008. pp. 1–14.

- ^ Leeper H. A.; Jones E. (October 2007). "How bad is fructose?" (PDF). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 86 (4). American Society for Clinical Nutrition: 895–896. PMID 17921361.

- ^ "Database of Select Committee on GRAS Substances (SCOGS) Reviews". Accessdata.fda.gov. 2006-10-31. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- ^ "U.S. Sugar Policy". SugarCane.org. Retrieved 2015-02-11.

- ^ "Food without Thought: How U.S. Farm Policy Contributes to Obesity". Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. November 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27.

- ^ "Corn Production/Value". Allcountries.org. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- ^ "Understanding High Fructose Corn Syrup". Beverage Institute.

- ^ Daniels, Lee A. (1984-11-07). "Coke, Pepsi to use more corn syrup". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

- ^ James Bovard. "Archer Daniels Midland: A Case Study in Corporate Welfare". cato.org. Archived from the original on 2007-07-11. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Table 51. Refined cane and beet sugar: estimated number of per capita calories consumed daily, by calendar year". Economic Research Service. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- ^ "Table 50. U.S. per capita caloric sweeteners estimated deliveries for domestic food and beverage use, by calendar year". Economic Research Service. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- ^ "U.S. Consumption of Caloric Sweeteners". Economic Research Service. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- ^ Landa, Michael M (30 May 2012). "Response to Petition from Corn Refiners Association to Authorize "Corn Sugar" as an Alternate Common or Usual Name for High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS)". Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ M. Ataman Aksoy; John C. Beghin, eds. (2005). "Sugar Policies: An Opportunity for Change". Global Agricultural Trade and Developing Countries. World Bank Publications. p. 329. ISBN 0-8213-5863-4.

- ^ International Sugar Organization March 2012 Alternative Sweeteners in a High Sugar Price Environment.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154.

- ^ Samuel VT (February 2011). "Fructose induced lipogenesis: from sugar to fat to insulin resistance". Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 22 (2): 60–5. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2010.10.003. PMID 21067942.

- ^ Parker-Pope, Tara (September 20, 2010). "In Worries About Sweeteners, Think of All Sugars". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- ^ Warner, M (2006-07-02). "A Sweetener With a Bad Rap". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ^ Forshee RA; Storey, ML; et al. (2007). "A critical examination of the evidence relating high-fructose corn syrup and weight gain" (pdf). Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 47 (6): 561–82. doi:10.1080/10408390600846457. PMID 17653981.

- ^ Moeller, S. M.; Fryhofer, S. A.; Osbahr Aj, 3rd; Robinowitz, C. B.; Council On Science Public Health, American Medical Association (2009). "The effects of high fructose syrup". Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 28 (6): 619–26. PMID 20516261.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Stanhope, Kimber L.; Schwarz, Jean-Marc; Havel, Peter J. (June 2013). "Adverse metabolic effects of dietary fructose". Current Opinion in Lipidology. 24 (3): 198–206. doi:10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283613bca. PMC 4251462. PMID 23594708.

- ^ Allocca, M; Selmi C (2010). "Emerging nutritional treatments for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease". In Preedy VR; Lakshman R; Rajaskanthan RS (eds.). Nutrition, diet therapy, and the liver. CRC Press. pp. 131–146. ISBN 1-4200-8549-2.

- ^ Chung, M; Ma, J; Patel, K; Berger, S; Lau, J; Lichtenstein, A. H. (2014). "Fructose, high-fructose corn syrup, sucrose, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or indexes of liver health: A systematic review and meta-analysis". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 100 (3): 833–849. doi:10.3945/ajcn.114.086314. PMC 4135494.

- ^ Sievenpiper, JL; de Souza, RJ; Mirrahimi, A; Yu, ME; Carleton, AJ; Beyene, J; Chiavaroli, L; Di Buono, M; Jenkins, AL; Leiter, LA; Wolever, TM; Kendall, CW; Jenkins, DJ (21 February 2012). "Effect of fructose on body weight in controlled feeding trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 156 (4): 291–304. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-156-4-201202210-00007. PMID 22351714.

- ^ Cozma, Adrian (2013). "The Role of Fructose, Sucrose, and High-fructose Corn Syrup in Diabetes". U.S. Endocrinology. 9: 128–138.

- ^ Bliss, Rosalie Marion (2016). "The Not-So-Sweet Truth About Sugars". Agricultural Research. 64: 1.

- ^ "High-fructose corn syrup: What are the health concerns?". Mayo Clinic. 2012-09-27. Retrieved 2012-10-17.

At this time, there's insufficient evidence to say that high-fructose corn syrup is any less healthy than other types of sweeteners.

- ^ American Heart Association. Updated: November 19, 2014 Added Sugars Quote: "The AHA recommendations focus on all added sugars, without singling out any particular types such as high-fructose corn syrup"

- ^ Dietary Guidelines for Americans (pdf) (7th ed.). United States Department of Agriculture and United States Department of Health and Human Services. December 2010. Retrieved 2012-10-17.

- ^ Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR (2006). "Fructose malabsorption and symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: guidelines for effective dietary management" (PDF). Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 106 (10): 1631–9. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2006.07.010. PMID 17000196.

- ^ a b c d "Sugar and Sweeteners, Background: High-Fructose Corn Syrup Production and Prices". US Department of Agriculture. 17 January 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ a b "What is Corn Refining?". The Corn Refiners Association. 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ White, J. S.; Hobbs, L. J.; Fernandez, S (2014). "Fructose content and composition of commercial HFCS-sweetened carbonated beverages". International Journal of Obesity. 39 (1): 176–182. doi:10.1038/ijo.2014.73. PMC 4285619.

- ^ "Soda Warning? High-fructose Corn Syrup Linked To Diabetes, New Study Suggests". ScienceDaily. 23 August 2007. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ a b Dufault, Renee (2009). "Mercury from chlor-alkali plants: measured concentrations in food product sugar". Environmental Health. 8: 2. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-8-2. PMC 2637263. PMID 19171026.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "High Fructose Corn Syrup Mercury Study Outdated; Based on Discontinued Technology". The Corn Refiners Association. 26 January 2009. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ "Mercury and Your Health". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Centers for Disease Control, US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ Louise Chu (2004-11-09). "Is Mexican Coke the real thing?". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2007-10-27.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Mexican Coke a hit in U.S." The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Dixon, Duffie (April 9, 2009). "Kosher Coke 'flying out of the store'". USA Today. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ Popa, Darclee; Ustunol, Zeynep (2011-08-01). "Sensory attributes of low-fat strawberry yoghurt as influenced by honey from different floral sources, sucrose and high-fructose corn sweetener". International Journal of Dairy Technology. 64 (3): 451–454. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0307.2011.00694.x. ISSN 1471-0307.

- ^ a b Mao, W; Schuler, M. A.; Berenbaum, M. R. (2013). "Honey constituents up-regulate detoxification and immunity genes in the western honey bee Apis mellifera". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (22): 8842–8846. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.8842M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1303884110. PMC 3670375.

- ^ a b c Wheeler, M. M.; Robinson, G. E. (2014). "Diet-dependent gene expression in honey bees: Honey vs. Sucrose or high fructose corn syrup". Scientific Reports. 4: 5726. Bibcode:2014NatSR...4E5726W. doi:10.1038/srep05726. PMC 4103092. PMID 25034029.

- ^ Krainer, S; Brodschneider, R; Vollmann, J; Crailsheim, K; Riessberger-Gallé, U (2016). "Effect of hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) on mortality of artificially reared honey bee larvae (Apis mellifera carnica)". Ecotoxicology. 25 (2): 320–8. doi:10.1007/s10646-015-1590-x. PMID 26590927.

- ^ Leblanc, B. W.; Eggleston, G; Sammataro, D; Cornett, C; Dufault, R; Deeby, T; St Cyr, E (2009). "Formation of hydroxymethylfurfural in domestic high-fructose corn syrup and its toxicity to the honey bee (Apis mellifera)". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 57 (16): 7369–76. doi:10.1021/jf9014526. PMID 19645504.

- ^ "Colony collapse disorder". US Environmental Protection Agency. 16 September 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ FDA rejects industry bid to change name of high fructose corn syrup to "corn sugar"

- ^ Lipton, Eric (12 February 2014). "Sweet-Talking the Public". New York Times.

- ^ CNBC (2016-08-02). "McDonald's to remove corn syrup from buns, curbs antibiotics in chicken". CNBC. Retrieved 2016-11-16.

- ^ "Major Brands No Longer Sweet on High-Fructose Corn Syrup". Retrieved 2016-11-16.

Further reading

- Litchfield, Ruth (2008). High Fructose Corn Syrup—How Sweet It Is. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. Retrieved 2013-03-01.