Radical centrism

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism |

|---|

|

The terms radical centrism, radical center (or radical centre), and radical middle refer to a political philosophy that arose in the Western nations, predominantly the United States and the United Kingdom, in the late 20th century. At first it was defined in a variety of ways, but at the beginning of the 21st century a number of texts and think tanks gave the philosophy a more developed cast.[1][2]

The "radical" in the term refers to a willingness on the part of most radical centrists to call for fundamental reform of institutions.[3] The "centrism" refers to a belief that genuine solutions require realism and pragmatism, not just idealism and emotion.[4] Thus one radical centrist text defines radical centrism as "idealism without illusions".[5][nb 1]

Most radical centrists borrow what they see as good ideas from left, right, and wherever else they may be found, often melding them together.[1] Most support market-based solutions to social problems with strong governmental oversight in the public interest.[7] There is support for increased global engagement and the growth of an empowered middle class in developing countries.[8] Many radical centrists work within the major political parties, but also support independent or third-party initiatives and candidacies.[9]

Criticism of radical centrist policies and strategies has mounted as the political philosophy has developed. One common criticism is that radical centrist policies are only marginally different from conventional centrist policies.[10] Another criticism is that the radical centrist penchant for third parties is naive and self-defeating.[10] Some observers see radical centrism as primarily a process of catalyzing dialogue and fresh thinking among polarized people and groups.[11]

Influences and precursors

Some influences on radical centrist political philosophy are not directly political. Robert C. Solomon, a philosopher with radical-centrist interests,[12] identifies a number of philosophical concepts supporting balance, reconciliation, or synthesis, including Confucius's concept of ren, Aristotle's concept of the mean, Erasmus's and Montaigne's humanism, Vico's evolutionary vision of history, William James's and John Dewey's pragmatism,[nb 2] and Aurobindo Ghose's integration of opposites.[14][nb 3]

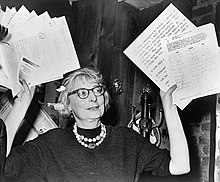

However, most commonly cited influences and precursors are from the political realm. For example, British radical-centrist politician Nick Clegg considers himself an heir to political theorist John Stuart Mill, former Liberal Prime Minister David Lloyd George, economist John Maynard Keynes, social reformer William Beveridge, and former Liberal Party leader Jo Grimond.[17] In his book Independent Nation (2004), John Avlon discusses precursors of 21st-century U.S. political centrism, including President Theodore Roosevelt, Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Senator Margaret Chase Smith, and African-American Senator Edward W. Brooke.[18] Radical centrist writer Mark Satin points to political influences from outside the electoral arena, including communitarian thinker Amitai Etzioni, magazine publisher Charles Peters, management theorist Peter Drucker, city planning theorist Jane Jacobs, and futurists Heidi and Alvin Toffler.[19][nb 4] Satin calls Benjamin Franklin the radical middle's favorite Founding Father since he was "extraordinarily practical", "extraordinarily creative", and managed to "get the warring factions and wounded egos [at the U.S. Constitutional Convention] to transcend their differences".[22]

Late 20th century groundwork

Initial definitions

One of the first uses of the term "radical middle" in a political context came in 1962, when cartoonist Jules Feiffer employed it to mock what he saw as the timid and pretentious outlook of the American political class.[23][24][nb 5] One of the first people to develop a positive definition was Renata Adler, a staff writer for The New Yorker. In the introduction to her second collection of essays, Toward a Radical Middle (1969), she presented radical centrism as a healing radicalism.[26] It rejected the violent posturing and rhetoric of the 1960s, she said, in favor of such "corny" values as "reason, decency, prosperity, human dignity, [and human] contact".[27] She called for the "reconciliation" of the white working class and African-Americans.[27]

In the 1970s, sociologist Donald I. Warren described the radical center as consisting of those "middle American radicals" who were suspicious of big government, the national media, and academics, as well as rich people and predatory corporations. Although they might vote for Democrats or Republicans, or for populists like George Wallace, they felt politically homeless and were looking for leaders who would address their concerns.[28][nb 6]

In the 1980s and 1990s, several authors contributed their understandings to the concept of the radical center. For example, futurist Marilyn Ferguson added a holistic dimension to the concept when she said, "[The] Radical Center ... is not neutral, not middle-of-the-road, but a view of the whole road".[31][nb 7] Sociologist Alan Wolfe located the creative part of the political spectrum at the center: "The extremes of right and left know where they stand, while the center furnishes what is original and unexpected."[33] African-American theorist Stanley Crouch upset many political thinkers when he pronounced himself a "radical pragmatist".[34] He explained, "I affirm whatever I think has the best chance of working, of being both inspirational and unsentimental, of reasoning across the categories of false division and beyond the decoy of race".[35]

In the 1990s, political independents Jesse Ventura, Angus King, and Lowell Weicker became governors of American states. According to John Avlon, they pioneered the combination of fiscal prudence and social tolerance that has served as a model for radical centrist governance ever since.[30] They also developed a characteristic style, a combination of "common sense and maverick appeal".[36][nb 8]

In his influential[39] 1995 Newsweek cover story, "Stalking the Radical Middle", journalist Joe Klein described radical centrists as angrier and more frustrated than conventional Democrats and Republicans. He said they share four broad goals: getting money out of politics, balancing the budget, restoring civility, and figuring out how to run government better. He also said their concerns were fueling "what is becoming a significant intellectual movement, nothing less than an attempt to replace the traditional notions of liberalism and conservatism".[40] [nb 9] [nb 10]

Relations to "Third Way"

In 1998, British sociologist Anthony Giddens claimed that the radical center is synonymous with the Third Way.[44] For Giddens, an advisor to former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, and for many other European political actors, the Third Way is a reconstituted form of social democracy.[38][45]

Some radical centrist thinkers do not equate radical centrism with the Third Way. In Britain, many do not see themselves as social democrats. Most prominently, British radical-centrist politician Nick Clegg has made it clear he does not consider himself an heir to Tony Blair,[17] and Richard Reeves, Clegg's longtime advisor, emphatically rejects social democracy.[46]

In the United States, the situation is different because the term Third Way was adopted by the Democratic Leadership Council and other moderate Democrats.[47] However, most U.S. radical centrists also avoid the term. Ted Halstead and Michael Lind's introduction to radical centrist politics fails to mention it,[48] and Lind subsequently accused the organized moderate Democrats of siding with the "center-right" and Wall Street.[29] Radical centrists have expressed dismay with what they see as "split[ting] the difference",[40] "triangulation",[29][49] and other supposed practices of what some of them call the "mushy middle".[50][51][nb 11]

Twenty-first century overviews

The first years of the 21st century saw publication of four introductions to radical centrist politics: Ted Halstead and Michael Lind's The Radical Center (2001), Matthew Miller's The Two Percent Solution (2003), John Avlon's Independent Nation (2004), and Mark Satin's Radical Middle (2004).[53][54] These books attempted to take the concept of radical centrism beyond the stage of "cautious gestures"[55] and journalistic observation and define it as a political philosophy.[1][2]

The authors came to their task from diverse political backgrounds: Avlon had been a speechwriter for New York Republican Mayor Rudolph Giuliani;[56] Miller had been a business consultant before serving in President Bill Clinton's budget office;[57] Lind had been an exponent of Harry Truman-style "national liberalism";[58] Halstead had run a think tank called Redefining Progress;[52] and Satin had co-drafted the U.S. Green Party's foundational political statement, "Ten Key Values".[59] There is, however, a generational bond: all these authors were between 31 and 41 years of age when their books were published (except for Satin, who was nearing 60).

While the four books do not speak with one voice, among them they express assumptions, analyses, policies, and strategies that helped set the parameters for radical centrism as a 21st-century political philosophy:

Assumptions

- Our problems cannot be solved by twiddling the dials; substantial reforms are needed in many areas.[60][61]

- Solving our problems will not require massive infusions of new money.[30][62]

- However, solving our problems will require drawing on the best ideas from left and right and wherever else they may be found.[4][63]

- It will also require creative and original ideas – thinking outside the box.[64][65][66]

- Such thinking cannot be divorced from the world as it is, or from tempered understandings of human nature. A mixture of idealism and realism is needed.[67] "Idealism without realism is impotent", says John Avlon. "Realism without idealism is empty".[4]

Analysis

- North America and Western Europe have entered an Information Age economy, with new possibilities that are barely being tapped.[68][69]

- In this new age, a plurality of people is neither liberal nor conservative, but independent[70] and looking to move in a more appropriate direction.[71]

- Nevertheless, the major political parties are committed to ideas developed in, and for, a different era; and are unwilling or unable to realistically address the future.[72][73]

- Most people in the Information Age want to maximize the amount of choice they have in their lives.[74][75]

- In addition, people are insisting that they be given a fair opportunity to succeed in the new world they are entering.[75][76]

Policies (in general)

- An overriding commitment to fiscal responsibility,[30] even if it entails means-testing of social programs.[77][78]

- An overriding commitment to reforming public education, whether by equalizing spending on school districts,[79] offering school choice,[80] hiring better teachers,[81] or empowering the principals and teachers we have now.[82]

- A commitment to market-based solutions in health care, energy, the environment, etc., so long as the solutions are carefully regulated by government to serve the public good.[83][84] The policy goal, says Matthew Miller, is to "harness market forces for public purposes".[7]

- A commitment to provide jobs for everyone willing to work, whether by subsidizing jobs in the private sector[85] or by creating jobs in the public sector.[86]

- A commitment to need-based rather than race-based affirmative action;[87][88] more generally, a commitment to race-neutral ideals.[89]

- A commitment to participate in institutions and processes of global governance, and be of genuine assistance to people in the developing nations.[8][90]

Strategy

- A new political majority can be built, whether it be seen to consist largely of Avlon's political independents,[91] Satin's "caring persons",[92] Miller's balanced and pragmatic individuals,[63] or Halstead and Lind's triad of disaffected voters, enlightened business leaders, and young people.[93]

- National political leadership is important; local and nonprofit activism is not enough.[94][95]

- Political process reform is also important – for example, implementing rank-order voting in elections and providing free media time to candidates.[96][97]

- A radical centrist party should be created, assuming one of the major parties cannot simply be won over by radical centrist thinkers and activists.[73][nb 12]

- In the meantime, particular independent, major-party, or third-party candidacies should be supported.[9][99]

Idea creation and dissemination

Along with publication of the four overviews of radical centrist politics, the first part of the 21st century saw a rise in the creation and dissemination of radical centrist policy ideas.[1][2]

Think tanks and mass media

Several think tanks are developing radical centrist ideas more thoroughly than was done in the overview books. Among them are Demos, in Britain; the Cape York Institute for Policy and Leadership, in Australia; and the New America Foundation, in the United States. The New America Foundation was started by authors Ted Halstead and Michael Lind, and two others, to bring radical centrist ideas to Washington, D.C. journalists and policy researchers.[52][nb 13]

A radical centrist perspective can also be found in major periodicals. In the United States, for example, The Washington Monthly was started by early radical centrist thinker Charles Peters,[101][102][nb 14] and many large-circulation magazines publish articles by New America Foundation fellows.[104] Columnists who write from a radical centrist perspective include John Avlon at The Daily Beast,[105] Thomas Friedman at The New York Times,[106] Joe Klein at Time magazine,[107] and Matthew Miller at The Washington Post.[108] Prominent journalists James Fallows and Fareed Zakaria have been identified as radical centrist.[1]

In Britain, the news magazine The Economist positions itself as radical centrist. An editorial ("leader") in 2012 declared, in bolded type, "A new form of radical centrist politics is needed to tackle inequality without hurting economic growth."[109] An essay on The Economist 's website the following year, introduced by the editor, argues that the magazine had always "com[e] ... from what we like to call the radical centre".[110]

Books on specific topics

Many books are offering radical centrist perspectives and policy proposals on specific topics. Some examples:

Foreign policy. In Ethical Realism (2006), British liberal Anatol Lieven and U.S. conservative John Hulsman advocate a foreign policy based on modesty, principle, and seeing ourselves as others see us.[111]

Environmentalism. In Break Through (2007), environmental strategists Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger call on activists to become more comfortable with pragmatism, high-technology, and aspirations for human greatness.[112]

Underachievement among minorities. In Winning the Race (2005), linguist John McWhorter says that many African Americans are negatively affected by a cultural phenomenon he calls "therapeutic alienation".[113]

Economics. In The Origin of Wealth (2006), Eric Beinhocker of the Institute for New Economic Thinking portrays the economy as a dynamic but imperfectly self-regulating evolutionary system, and suggests policies that could support benign socio-economic evolution.[114]

International relations. In How to Run the World (2011), scholar Parag Khanna argues that the emerging world order should not be run from the top down, but by a galaxy of nonprofit, nation-state, corporate, and individual actors cooperating for their mutual benefit.[115]

Defining others as enemies. In The Righteous Mind (2012), psychologist Jonathan Haidt attempts to explain "why good people are divided by politics and religion".[116]

Political organizing. In Voice of the People (2008), conservative activist Lawrence Chickering and liberal attorney James Turner attempt to lay the groundwork for a grassroots "transpartisan" movement across the U.S.[117]

What one person can do. In his memoir Radical Middle: Confessions of an Accidental Revolutionary (2010), South African journalist Denis Beckett tries to show that one person can make a difference in a situation many might regard as hopeless.[118]

Ideas into action

Ross Perot

Some commentators identify Ross Perot's 1992 U.S. Presidential campaign as the first radical middle national campaign.[40][119] However, many radical centrist authors are not enthusiastic about Ross Perot. Matthew Miller acknowledges that Perot had enough principle to support a gasoline tax hike,[120] Halstead and Lind note that he popularized the idea of balancing the budget,[121] and John Avlon says he crystallized popular distrust of partisan extremes.[122] But none of those authors examines Perot's ideas or campaigns in depth, and Mark Satin does not mention Perot at all.

Joe Klein mocks one of Perot's campaign gaffes and says he was not a sufficiently substantial figure.[40] Miller characterizes Perot as a rich, self-financed lone wolf.[123] By contrast, what most radical centrists say they want in political action terms is the building of a grounded political movement.[124][125]

By the decade of the 2010s, radical centrists were engaged in a variety of actions in the English-speaking nations:

Britain

Following the 2010 election, Nick Clegg, then leader of the Liberal Democrats (Britain's third-largest party at the time), had his party enter into a Conservative – Liberal Democrat coalition agreement to form a majority government.[126] In a speech to party members in the spring of 2011, Clegg declared that he considers himself and his party to be radical centrist:

For the left, an obsession with the state. For the right, a worship of the market. But as liberals, we place our faith in people. People with power and opportunity in their hands. Our opponents try to divide us with their outdated labels of left and right. But we are not on the left and we are not on the right. We have our own label: Liberal. We are liberals and we own the freehold to the centre ground of British politics. Our politics is the politics of the radical centre.[127]

In the autumn of 2012, Clegg's longtime policy advisor elaborated on the differences between Clegg's identity as a "radical liberal" and traditional social democracy.[46]

Australia

In Australia, Aboriginal lawyer Noel Pearson is building an explicitly radical centrist movement among Aborigines.[128] The movement is seeking more assistance from the Australian state, but is also seeking to convince individual Aborigines to take more responsibility for their lives.[129]

United States

In the U.S., the radical centrist movement is being played out in the national media. In 2010, for example, The New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman called for "a Tea Party of the radical center", an organized national pressure group.[130] At The Washington Post, columnist Matthew Miller was explaining "Why we need a third party of (radical) centrists".[131][nb 15]

In 2011 Friedman championed Americans Elect, an insurgent group of radical centrist Democrats, Republicans and independents who were hoping to run an independent Presidential candidate in 2012.[106] Meanwhile, Miller offered "The third-party stump speech we need".[135] In his book The Price of Civilization (2011), Columbia University economist Jeffrey Sachs called for the creation of a third U.S. party, an "Alliance for the Radical Center".[136]

While no independent radical-centrist Presidential candidate emerged in 2012, John Avlon emphasized the fact that independent voters remain the fastest-growing portion of the electorate.[105]

Beyond the English-speaking nations

Explicitly radical centrist ideas and activities are largely confined to majority-English-speaking nations. However, analogous political perspectives are arising in other parts of the world.

In India, for example, there is interest in an outlook sometimes called "socio-capitalism".[137] In China, "New Confucianism" is making an appearance.[138][139] In Latin America, people speak of a "new pragmatism" pioneered by leaders like Brazil's Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Chile's Ricardo Lagos and Michelle Bachelet, despite the left-wing position of their own parties.[140][141]

Zack Taylor, conflict specialist for Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States at the United Nations Development Programme, is convinced that inequality, elitism, corruption, and cronyism are pushing many middle class Eurasians toward "constitutional liberalism" – which Taylor calls the "radical middle".[142]

Criticisms

Even before the 21st century, some observers were speaking out against what they saw as radical centrism.[nb 16] In 1998, for example, Belgian political theorist Chantal Mouffe argued that passionate and often bitter conflict between left and right is a necessary feature of any democracy.[144][nb 17]

Objections to ideas and attitudes

Some 21st century commentators argue that radical centrist ideas are not substantially different from conventional centrist ideas.[10][146] For example, U.S. economist Robert Kuttner says there already is a radical centrist party – "It's called the Democrats".[147] Social theorist Richard Kahlenberg says that Ted Halstead and Michael Lind's book Radical Center, in particular, is too skeptical about the virtues of labor unions, and too ardent about the virtues of the market.[148]

In 2001, media critic Eric Alterman said that New America Foundation was not liberal nor a progressive think tank and did not know what it was.[52]

Some think radical centrist ideas are too different from current policies. Sam Tanenhaus the editor of The New York Times Book Review called the proposals in Halstead and Lind's book "utopian".[2] According to Ed Kilgore, the policy director of the Democratic Leadership Council, Mark Satin's Radical Middle book "ultimately places him in the sturdy tradition of 'idealistic' American reformers who think smart and principled people unencumbered by political constraints can change everything".[146]

Political analyst James Joyner does not think that U.S. states employing non-partisan redistricting commissions implement more fiscally responsible measures than states without commissions.[149]

Radical centrist attitudes have also been criticized. For example, many bloggers have characterized Thomas Friedman's columns on radical centrism as elitist and glib.[10] Former South African freedom fighter Duma Ndlovu finds "warmth" and "humanity" in South African journalist Denis Beckett's memoir Radical Middle, but he also finds "a bit of self-righteousness ... because Denis does no wrong".[150]

Objections to strategies

Some observers question the wisdom of seeking consensus, post-partisanship, or reconciliation in political life.[10] Political scientist Jonathan Bernstein argues that American democratic theory from the time of James Madison's Federalist No. 10 (1787) has been based on the acknowledgement of faction and the airing of debate, and he sees no reason to change now.[10]

Other observers feel radical centrists are misreading the political situation. For example, conservative journalist Ramesh Ponnuru says liberals and conservatives are not ideologically opposed to such radical centrist measures as limiting entitlements and raising taxes to cover national expenditures. Instead, voters are opposed to them, and things will change when voters can be convinced otherwise.[151]

The third-party strategy favored by many U.S. radical centrists has been criticized as impractical and diversionary. According to these critics, what is needed instead is (a) reform of the legislative process, and (b) candidates in existing political parties who will support radical centrist ideas.[10] The specific third-party vehicle favored by many U.S. radical centrists in 2012 – Americans Elect [152] – was criticized as an "elite-driven party"[10] supported by a "dubious group of Wall Street multi-millionaires".[147]

After spending time with a variety of radical centrists, journalist Alec MacGillis concluded that their perspectives are so disparate that they could never come together to build a viable political organization.[153]

Internal concerns

Some radical centrists are less than sanguine about their future. One concern is co-optation. For example, Michael Lind worries that the enthusiasm for the term radical center, on the part of "arbiters of the conventional wisdom", may signal a weakening of the radical vision implied by the term.[29]

Another concern is passion. John Avlon fears that some centrists cannot resist the lure of passionate partisans, whom he calls "wingnuts".[154] By contrast, Mark Satin worries that radical centrism, while "thoroughly sensible", lacks an "animating passion" – and claims there has never been a successful political movement without one.[155]

Radical centrism as dialogue and process

Some radical centrists, such as mediator Mark Gerzon[156] and activist Joseph F. McCormick, see radical centrism as primarily a commitment to process.[66][157] Their approach is to facilitate processes of structured dialogue among polarized people and groups, from the neighborhood level on up.[66][158] A major goal is to enable dialogue participants to come up with new perspectives and solutions that can address every party's core interests.[66][159] Both ecologist Gary Nabhan and Onward Christian Athletes author Tom Krattenmaker speak of the radical center as that (metaphoric) space where such dialogue and innovation can occur.[11][160]

Organizations seeking to catalyze dialogue and innovation among diverse people and groups include AmericaSpeaks, National Issues Forums, and Search for Common Ground. The city of Portland, Oregon, has been characterized as "radical middle" in USA Today newspaper because many formerly antagonistic groups there are said to be talking to, learning from, and working with one another.[11]

See also

Notes

- ^ The phrase was originally John F. Kennedy's.[6]

- ^ For an extended discussion of neoclassical American pragmatism and its possible political implications, see Louis Menand's book The Metaphysical Club.[13]

- ^ An international evangelical movement, the Association of Vineyard Churches, describes itself as "radical middle" because it believes that spiritual truth is found by holding supposedly contradictory concepts in tension. Examples include head vs. heart, planning vs. being Spirit-led, and standing for truth vs. standing for Unity.[15]

- ^ In the 1980s, Satin's own Washington, D.C.-based political newsletter, New Options, described itself as "post-liberal".[20] Culture critic Annie Gottlieb says it urged the New Left and New Age to "evolve into a 'New Center'".[21]

- ^ According to journalist John Judis, the first person to employ the term "radical centrism" was an American sociologist, Seymour Martin Lipset, who used it in his book Political Man (1960) to help explain European fascism.[25]

- ^ Warren's book influenccd Michael Lind and other 21st century radical centrists.[2][29]

- ^ Two years later, another prominent futurist, John Naisbitt, wrote in bolded type, "The political left and right are dead; all the action is being generated by a radical center" .[32]

- ^ By the end of the 20th century, some mainstream politicians were cloaking themselves in the language of the radical center. For example, in 1996 former U.S. Defense Secretary Elliot Richardson stated, "I am a moderate – a radical moderate. I believe profoundly in the ultimate value of human dignity and equality".[37] At a conference in Berlin, Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chrétien declared, "I am the radical center".[38]

- ^ Subsequent to Klein's article, some political writers posited the existence of two radical centers, one neopopulist and bitter and the other moderate and comfortable.[25][41] According to historian Sam Tanenhaus, one of the strengths of Ted Halstead and Michael Lind's book The Radical Center (2001) is it attempts to weld the two supposed radical-centrist factions together.[2]

- ^ A 1991 story in Time magazine with a similar title, "Looking for The Radical Middle", revealed the existence of a "New Paradigm Society" in Washington, D.C., a group of high-level liberal and conservative activists seeking ways to bridge the ideological divide.[42] The article discusses what it describes as the group's virtual manifesto, E. J. Dionne's book Why Americans Hate Politics.[43]

- ^ In 2010, radical centrist Michael Lind stated that "to date, President Obama has been the soft-spoken tribune of the mushy middle".[29]

- ^ Matthew Miller added an "Afterword" to the paperback edition of his book favoring formation of a "transformational third party" by the year 2010, if the two major parties remained stuck in their ways.[98]

- ^ Besides Halstead and Lind, thinkers affiliated with the New America Foundation in the early 2000s included Katherine Boo, Steven Clemons, James Fallows, Maya MacGuineas, Walter Russell Mead, James Pinkerton, Jedediah Purdy, and Sherle Schwenninger.[52][100]

- ^ Peters used the term "neoliberal" to distinguish his ideas from those of neoconservatives and conventional liberals. His version of neoliberalism is separate from what came to be known internationally as neoliberalism.[102][103]

- ^ In 2009, on The Huffington Post website, the president of The Future 500[132] – following up on his earlier endorsement of the "radical middle"[133] – made the case for a "transpartisan" alliance between left and right.[134]

- ^ In 1967, a novella by science fiction writer Mack Reynolds portrayed a conspiracy of powerful men that called itself the "Radical Center". They planned to take over the government by spreading an anything-goes morality that would make citizens selfish, apathetic, and non-judgmental.[143]

- ^ Mouffe also criticized radical centrism for its "New Age rhetorical flourish".[145]

References

- ^ a b c d e Olson, Robert (January–February 2005). "The Rise of 'Radical Middle' Politics". The Futurist, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 45–47. Publication of the World Future Society. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Tanenhaus, Sam (14 April 2010). "The Radical Center: The History of an Idea". The New York Times Book Review. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ Halstead, Ted; Lind, Michael (2001). The Radical Center: The Future of American Politics. Doubleday / Random House, p. 16. ISBN 978-0-385-50045-6.

- ^ a b c Avlon, John (2004). Independent Nation: How the Vital Center Is Changing American Politics. Harmony Books / Random House, p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4000-5023-9.

- ^ Satin, Mark (2004). Radical Middle: The Politics We Need Now. Westview Press and Basic Books, p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8133-4190-3.

- ^ Avlon (2004), p. 109.

- ^ a b Miller, Matthew (2003). The Two Percent Solution: Fixing America's Problems in Ways Liberals and Conservatives Can Love. Public Affairs / Perseus Books Group. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-58648-158-2.

- ^ a b Halstead, Ted, ed.(2004). The Real State of the Union: From the Best Minds in America, Bold Solutions to the Problems Politicians Dare Not Address. Basic Books, Chaps. 27–31. ISBN 978-0-465-05052-9.

- ^ a b Avlon (2004), Part 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Marx, Greg (25 July 2011). "Tom Friedman's 'Radical' Wrongness". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ a b c Krattenmaker, Tom (27 December 2012). "Welcome to the 'Radical Middle'". USA Today newspaper. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ Solomon, Robert C. (2003). A Better Way to Think About Business: How Personal Integrity Leads to Corporate Success. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538315-7.

- ^ Menand, Louis (2001). The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Part Five. ISBN 978-0-374-19963-0.

- ^ Solomon Robert C. Higgins, Kathleen M. (1996). A Short History of Philosophy. Oxford University Press, pp. 93, 66, 161, 179, 222, 240, and 298. ISBN 978-0-19-510-196-6.

- ^ Jackson, Bill (1999). The Quest for the Radical Middle: A History of the Vineyard. Vineyard International Publishing, pp. 18–21. ISBN 978-0-620-24319-3.

- ^ Satin (2004), p. 30.

- ^ a b Stratton, Allegra; Wintour, Patrick (13 March 2011). "Nick Clegg Tells Lib Dems They Belong in 'Radical Centre' of British Politics". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ Avlon, John (2004), pp. 26, 173, 223, 244, and 257.

- ^ Satin (2004), pp. 10, 23, and 30

- ^ Rosenberg, Jeff (17 March 1989). "Mark's Ism: New Options's Editor Builds a New Body Politic". Washington City Paper, pp 6–8.

- ^ Gottlieb, Annie (1987). Do You Believe in Magic?: Bringing thev 60s Back Home. Simon & Schuster, p. 154. ISBN 978-0-671-66050-5.

- ^ Satin (2004), p. 22.

- ^ Feiffer, Jules (21 January 1962). "We've All Heard of the Radical Right and the Radical Left ... ". Library of Congress website. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ Feiffer, Jules (2010). Backing into Forward: A Memoir. Nan A. Talese / Doubleday, p. 345. ISBN 978-0-385-53158-0.

- ^ a b Judis, John (16 October 1995). "TRB from Washington: Off Center". The New Republic, vol. 213, no. 16, pp. 4 and 56.

- ^ Adler, Renata (1969). Toward a Radical Middle: Fourteen Pieces of Reporting and Criticism. Random House, pp. xiii–xxiv. ISBN 978-0-394-44916-6.

- ^ a b Adler (1969), p. xxiii.

- ^ Warren, Donald I. (1976). The Radical Center: Middle Americans and the Politics of Alienation. University of Notre Dame Press, Chap. 1. ISBN 978-0-268-01594-7.

- ^ a b c d e Lind, Michael (20 April 2010). "Now More than Ever, We Need a Radical Center". Salon.com website. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d Avlon (2004), pp. 277–93 ("Radical Centrists").

- ^ Ferguson, Marilyn (1980). The Aquarian Conspiracy: Personal and Social Transformation in the 1980s. J. P. Tarcher Inc. / Houghton Mifflin, pp. 228–29. ISBN 978-0-87477-191-6.

- ^ Naisbitt, John (1982). Megatrends: Ten New Directions Transforming Our Lives. Warner Books / Warner Communications Company, p. 178. ISBN 978-0-446-35681-7.

- ^ Wolfe, Alan (1996). Marginalized in the Middle. University of Chicago Press, p. 16. ISBN 978-0-226-90516-7.

- ^ Author unidentified (30 January 1995). "The 100 Smartest New Yorkers". New York Magazine, vol. 28, no. 5, p. 41.

- ^ Crouch, Stanley (1995). The All-American Skin Game; or, The Decoy of Race. Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-679-44202-8.

- ^ Avlon (2004), p. 277.

- ^ Richardson, Elliot (1996). Reflections of a Radical Moderate. Pantheon Books, Preface. ISBN 978-0-679-42820-6.

- ^ a b Andrews, Edward L. (4 June 2000). "Growing Club of Left-Leaning Leaders Strains to Find a Focus". The Nev York Times, p. 6.

- ^ Satin (2004), p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Klein, Joe (24 September 1995). "Stalking the Radical Middle". Newsweek, vol. 126, no. 13, pp. 32–36. Web version identifies the author as "Newsweek Staff". Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ Lind, Michael (3 December 1995). "The Radical Center or The Moderate Middle?" The New York Times Magazine, pp. 72–73. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ^ Duffy, Michael (20 May 1991). "Looking for The Radical Middle". Time magazine. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ Dionne, E. J. (1991). Why Americans Hate Politics. Touchstone / Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-68255-2.

- ^ Giddens, Anthony (1998). The Third Way: The Renewal of Social Democracy. Polity Press, pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-0-7456-2267-5.

- ^ Giddens, Anthony (2000). The Third Way and Its Critics. Polity Press, Chap. 2 ("Social Democracy and the Third Way"). ISBN 978-0-7456-2450-1.

- ^ a b Reeves, Richard (19 September 2012). "The Case for a Truly Liberal Party". The New Statesman, p. 26. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ Smith, Ben (7 February 2011). "The End of the Democratic Leadership Council Era". Politico website. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ Halstead and Lind (2001), p. 263.

- ^ Burns, James MacGregor; Sorenson, Georgia J. (1999). Dead Center: Clinton-Gore Leadership and the Perils of Moderation. Scribner, p. 221. ISBN 978-0-684-83778-9.

- ^ Satin (2004), p. ix.

- ^ Ray, Paul H.; Anderson, Sherry Ruth (2000). The Cultural Creatives: How 50 Million People Are Changing the World. Harmony Books / Random House, pp. xiv and 336. ISBN 978-0-609-60467-0.

- ^ a b c d e Morin, Richard; Deane, Claudia (10 December 2001). "Big Thinker. Ted Halstead's New America Foundation Has It All: Money, Brains and Buzz". The Washington Post, Style section, p. 1.

- ^ Satin (2004), p. 10 (citing "big-picture introductions" by Halstead-Lind and Miller).

- ^ Wall, Wendy L. (2008). Inventing the 'American Way': The Politics of Consensus from the New Deal to the Civil Rights Movement. Oxford University Press, pp. 297–98 n. 25 (citing Avlon, Halstead-Lind, and Satin as contemporary calls to the creative center). ISBN 978-0-19-532910-0.

- ^ Avlon (2004), p. 3.

- ^ Avlon (2004), pp. 378–79.

- ^ Miller (2003), p. xiv.

- ^ Lind, Michael (1996). Up from Conservatism: Why the Right Is Wrong for America. Free Press / Simon & Schuster, p. 259. ISBN 978-0-684-83186-2.

- ^ Gaard, Greta (1998). Ecological Politics: Ecofeminism and the Greens. Temple University Press, pp. 142–43. ISBN 978-1-56639-569-4.

- ^ Halstead and Lind (2001), p. 16.

- ^ Satin (2004), pp. 3–5.

- ^ Miller (2003), pp. ix–xiii.

- ^ a b Miller (2003), pp. xii–xii.

- ^ Avlon (2004), p. 21.

- ^ Halstead and Lind (2001), pp. 6–12.

- ^ a b c d Utne, Leif (September–October 2004). "The Radical Middle". Utne Reader, issue no. 125, pp. 80–85. Contains brief interviews with 10 radical centrists including Halstead, Satin, Tom Atlee, Laura Chasin, Joseph F. McCormick, and Joel Rogers. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ Satin (2004), pp. 5–6.

- ^ Halstead and Lind (2001), pp. 13, 56-58, and 64.

- ^ Satin (2004), pp. 14–17.

- ^ Avlon (2004), pp. 1 and 13.

- ^ Miller (2003), p. 52.

- ^ Avlon (2004), p. 19.

- ^ a b Halstead and Lind (2001), pp. 223–24.

- ^ Halstead and Lind (2001), p. 19.

- ^ a b Satin (2004), pp. 6–8.

- ^ Miller (2003), Chap. 4.

- ^ Halstead and Lind (2001), p. 78.

- ^ Miller (2003), p. 207.

- ^ Halstead and Lind (2001), p. 154.

- ^ Miller (2003), Chap. 7.

- ^ Miiller (2003), Chap. 6.

- ^ Satin (2004), Chap. 7.

- ^ Avlon (2004), pp. 15 and 26–43 (on Theodore Roosevelt).

- ^ Halstead and Lind (2001), p. 14.

- ^ Miller (2003), Chap. 8.

- ^ Satin (2004), pp. 92–93.

- ^ Halstead and Lind (2001), pp. 170–76.

- ^ Satin (2004), Chap. 8.

- ^ Avlon (2004), pp. 257–76 (on Senator Edward W. Brooke).

- ^ Satin (2004), Chaps. 13–15.

- ^ Avlon (2004), pp. 10–13.

- ^ Satin (2004), pp. 17–18.

- ^ Halstead and Lind (2004), pp. 214–23.

- ^ Avlon (2004), p. 18.

- ^ Miller (2003), p. 230, and Postscript.

- ^ Halstead and Lind (2001), pp. 109–28.

- ^ Satin (2004), pp. 198–202.

- ^ Miller, Matthew (2003a). The Two Percent Solution: Fixing America's Problems in Ways Liberals and Conservatives Can Love. Public Affairs / Perseus Books Group. Paperback edition, pp. 263–88. ISBN 978-1-58648-289-3.

- ^ Satin (2004), Chap. 18.

- ^ Halstead, ed. (2004), pp. v–vii and xiii.

- ^ Satin (2004), pp. 22–23 ("Franklin to Peters to You").

- ^ a b Carlson, Peter (30 April 2001). "Charlie Peters: The Genuine Article". The Washington Post, p. C01. Reprinted at the Peace Corps Online website. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ Peters, Charles (May 1983). "A Neoliberal's Manifesto". The Washington Monthly, pp. 8–18. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ "Articles" page. New America Foundation website. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ a b Avlon, John (23 September 2012). "Political Independents: The Future of Politics?". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ a b Friedman, Thomas (23 July 2011). "Make Way for the Radical Center". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ Klein, Joe (13 June 2007). "The Courage Primary". Time magazine. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ Miller, Matthew (24 June 2010). "A Case for 'Radical Centrism'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ Leader (13 October 2012). "True Progressivism: Inequality and the World Economy". The Economist. Accessed 4 September 2013.

- ^ J.C. (2 September 2013). "Is The Economist Left- or Right-Wing?" The Economist website. Accessed 4 September 2013.

- ^ Lieven, Anatol; Hulsman, John (2006). Ethical Realism: A Vision for America's Role in the World. Pantheon Books / Random House, Introduction. ISBN 978-0-375-42445-8.

- ^ Nordhaus, Ted; Shellenberger, Michael (2007). Break Through: From the Death of Environmentalism to the Politics of Possibility. Houghton Mifflin, Introduction. ISBN 978-0-618-65825-1.

- ^ McWhorter, John (2005). Winning the Race: Beyond the Crisis in Black America. Gotham Books / Penguin Group, Chap. 5. ISBN 978-1-59240-188-8.

- ^ Beinhocker, Eric D. (2006). The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics. Harvard Business School Press, pp. 11–13 and Chap. 18 ("Politics and Policy: The End of Left versus Right"). ISBN 978-1-57851-777-0.

- ^ Khanna, Parag (2011). How to Run the World: Charting a Course to the Next Renaissance. Random House, Part One. ISBN 978-0-6796-0428-0.

- ^ Haidt, Jonathan (2012). The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. Pantheon Books, Introduction. ISBN 978-0-307-37790-6.

- ^ Chickering, A. Lawrence; Turner, James S. (2008). Voice of the People: The Transpartisan Imperative in American Life. DaVinci Press, Part V. ISBN 978-0-615-21526-6.

- ^ Beckett, Denis (2010). Radical Middle: Confessions of an Accidental Revolutionary. Tafelberg. ISBN 978-0-624-04912-8.

- ^ Sifry, Micah L. (2003). Spoiling for a Fight: Third-Party Politics in America. Routledge, Section II ("Organizing the Angry Middle"). ISBN 978-0-415-93142-7.

- ^ Miller (2003), p. 187.

- ^ Halstead and Lind (2001), p. 115.

- ^ Avlon (2004), p. 284.

- ^ Miller (2003), p. 178.

- ^ Halstead and Lind (2001), Chap. 5 ("The Politics of the Radical Center").

- ^ Satin (2004), Part Six ("Be a Player, Not a Rebel").

- ^ Author unidentified (12 May 2011). "David Cameron and Nick Clegg Pledge ‘United' Coalition". BBC News website. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ Clegg, Nick (13 March 2011). "Full Transcript, Speech to Liberal Democrat Spring Conference, Sheffield, 13 March 2011". New Statesman. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ Pearson, Noel (2 September 2010). "Nights When I Dream of a Better World: Moving from the Centre-Left to the Radical Centre of Australian Politics". The John Button Foundation website. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ Pearson, Noel (21 April 2007). "Hunt for the Radical Centre". The Australian. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ Friedman, Thomas L. (20 March 2010). "A Tea Party Without Nuts". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ Miller, Matt (11 November 2010). "Why We Need a Third Party of (Radical) Centrists". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ Future 500. Official website. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ Shireman, Bill (5 April 2009). "The Radical Middle Wins in Iowa". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ Shireman, Bill (20 April 2009). "Time for a Tea Party with the Right: Why Progressives Need a Transpartisan Strategy". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ Miller, Matt (25 September 2011). "The Third-Party Stump Speech We Need". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ Sachs, Jeffrey R. (2011). The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity. Random House, pp. 247–48. ISBN 978-0-8129-8046-2.

- ^ Jaganathan, R. (10 May 2009). "Socio-Capitalism Set to Become the New Economic Doctrine?". DNA: Daily News & Analysis (Mumbai). Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ Bell, Daniel A. (2008). China's New Confucianism: Politics and Everyday Life in a Changing Society. Princeton University Press, Chapter One. Chapter retrieved 5 January 2013. ISBN 978-0-691-13690-5.

- ^ Tu Weiming (no fixed date). Tu Weiming: China's New Confucianism. Website of New-Confucian scholar with concurrent positions at Beijing University and Harvard University. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ Santiso, Javier (2006). Latin America's Political Economy of the Possible. Introduction by Andres Velasco. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-0-262-69359-2.

- ^ Shifter, Michael (6 August 2010). "Latin America's Shift to the Center". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ Taylor, Zack (25 January 2012). "Inequality and the 'Radical Middle'". Voices from Eurasia, weblog of the United Nations Development Programme in Europe and CIS. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ Reynolds, Mack (1967). "Radical Center". Reprinted in Olander, Joseph D.; Greenberg, Martin H.; Warrick, Patricia (1974). American Government Through Science Fiction. Foreword by Frederik Pohl. Rand McNally College Publishing Co., pp. 14–42. ISBN 978-0-528-65902-7.

- ^ Mouffe, Chantal (summer 1998). "The Radical Centre: A Politics Without Adversary". Soundings, issue no. 9, pp. 11–23.

- ^ Mouffe (summer 1998), p. 12.

- ^ a b Kilgore, Ed (June 2004). "Good Government: Time to Stop Bashing the Two-Party System". The Washington Monthly, pp. 58–59. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ a b Kuttner, Robert (19 February 2012). "The Radical Center we Don't Need". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ Kahlenberg, Richard (19 December 2001). "Radical in the Center". American Prospect. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ Joyner, James (2010-03-24). "Radical Center: Friedman's Fantasy". Outside the Beltway. Retrieved 2013-04-30

- ^ Ndlovu, Duma (3 February 2011). "So That's What the White Bosses Were Up To?". D2: Democracy Version Two website. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ Ponnuru, Ramesh (24 March 2010). "The Corner: Tom Friedman's Radical Confusion". National Review. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ MacGillis, Alec (26 October 2011). "Third Wheel". The New Republic. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ MacGillis, Alec (2 November 2011). "Beware: 'Radical Centrists' On the March!". The New Republic. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ Avlon, John (2010). Wingnuts: How the Lunatic Fringe Is Hijacking America. Beast Books / Perseus Books Group, pp. 1–3 and 238–39. ISBN 978-0-9842951-1-1.

- ^ Satin, Mark (fall 2002). "Where's the Juice?". The Responsive Community, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 74–75. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ Satin (2004), p. 27.

- ^ Gerzon, Mark (2006). Leading Through Conflict: How Successful Leaders Transform Differences into Opportunity. Harvard Business School Press, pp. 4–8. ISBN 978-1-59139-919-3.

- ^ Gerzon (2006, Chaps. 9–10.

- ^ Gerzon (2006), Chap. 11.

- ^ Nabhan, Gary Paul, and 19 others (February 2003). "An Invitation to Join the Radical Center". A West That Works website. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

Further reading

From the 1990s

- Coyle, Diane (1997). The Weightless World: Strategies for Managing the Digital Economy. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03259-9.

- Esty, Daniel C.; Chertow, Marian, eds. (1997). Thinking Ecologically: The Next Generation of Ecological Policy. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07303-4.

- Penny, Tim; Garrett, Major (1998). The 15 Biggest Lies in Politics. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-18294-6.

- Sider, Ronald J. (1999). Just Generosity: A New Vision for Overcoming Poverty in America. Baker Books. ISBN 978-0-8010-6613-9.

- Ventura, Jesse (2000). I Ain't Got Time to Bleed: Reworking the Body Politic from the Bottom Up. New York: Signet. ISBN 0451200861.

- Wolfe, Alan (1998). One Nation, After All: What Middle-Class Americans Really Think. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-87677-8.

From the 2000s

- Anderson, Walter Truett (2001). All Connected Now: Life in the First Global Civilization. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-3937-5.

- Florida, Richard (2002). The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It's Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02476-6.

- Lukes, Steven (2009). The Curious Enlightenment of Professor Caritat: A Novel of Ideas. Verso Books, 2nd ed. ISBN 978-1-84467-369-8.

- Miller, Matt (2009). The Tyranny of Dead Ideas: Letting Go of the Old Ways of Thinking to Unleash a New Prosperity. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-8050-9150-2.

- Penner, Rudolph; Sawhill, Isabel; Taylor, Timothy (2000). Updating America's Social Contract: Economic Growth and Opportunity in the New Century. W. W. Norton and Co., Chap. 1 ("An Agenda for the Radical Middle"). ISBN 978-0-393-97579-6.

- Wexler, David B.; Winick, Bruce, eds. (2003). Judging in a Therapeutic Key: Therapeutic Justice and the Courts. Carolina Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-89089-408-8.

- Whitman, Christine Todd (2005). It's My Party, Too: The Battle for the Heart of the GOP and the Future of America. The Penguin Press, Chap. 7 ("A Time for Radical Moderates"). ISBN 978-1-59420-040-3.

From the 2010s

- Brock, H. Woody (2012). American Gridlock: Why the Right and Left Are Both Wrong. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-63892-7.

- Edwards, Mickey (2012). The Parties Versus the People: How to Turn Republicans and Democrats Into Americans. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-18456-3.

- Pearson, Noel (2011). Up From the Mission: Selected Writings. Black Inc. 2nd ed. Part Four ("The Quest for a Radical Centre"). ISBN 978-1-86395-520-1.

- Salit, Jacqueline S. (2012). Independents Rising: Outsider Movements, Third Parties, and the Struggle for a Post-Partisan America. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-33912-5.

- Whelan, Charles (2013). The Centrist Manifesto. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-34687-9.

External links

Organizations

- Breakthrough Institute – U.S. think tank

- Cape York Institute for Policy & Leadership – Australian think tank

- Centre Forum – U.K. think tank

- Centrist Project – U.S. political group

- Demos – U.K. think tank

- Mediators Foundation – U.S. dialogues

- National Issues Forums – U.S. dialogues

- New America Foundation – U.S. think tank

- No Labels – U.S. political group

- Search for Common Ground – global dialogues

Opinion websites

- CenterLine – Charles Wheelan

- James Fallows blog – James Fallows

- John Avlon articles – John Avlon

- Matt Miller: The Archives – Matt Miller

- Michael Lind articles - Michael Lind

- New America articles – opinion from New America Foundation's staff and fellows

- Radical Middle Newsletter – Mark Satin

Manifestos, in chronological order

- "Road to Generational Equity" – Tim Penny, Richard Lamm, and Paul Tsongas (1995). Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- "Invitation to Join the Radical Center" – Gary Paul Nabhan and others (2003). Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- "The Cape York Agenda" – Noel Pearson (2005). Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- "Ten Big Ideas for a New America" – New America Foundation (2007). Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- "The Liberal Moment" – Nick Clegg (2009). Retrieved 2 October 2012.