User:Apoxyomenus/Fast

Embodying so many "firsts" in music terms and outside her industry.

Contextual lens in defining Madonna's career[edit]

Billboard's Louis Virtel argues that "the task of defining Madonna's impact is brutal".[2] Varios authors start this journey in defining her career per se, as according to some she attained a relatively "unusual" status (mainly attributed in female terms).[3] Robin Raven from Grammy.com also noted that "it's often said that Madonna was ahead of her time".[4] English music journalist Paul Morley, states "what made her so ahead of her time, is that you can use her, colourise her, mix her, remix her, as part of your own narrative of meaning.[5] In the late-1980s, Billboard staff said she was always stayed one step ahead our expectations.[6]

According to The Daily Telegraph, she has contributed more to the cultural conversation than any female performer in history.[7] Singaporean magazine GameAxis Unwired explained that she pioneered a multifaceted career that "encompasses virtually every aspect of contemporary culture".[8] The New York Times staff confirmed that she has "singular career" beyond music, fashion and movies that's "crossed boundaries and obliterated the status quo".[9] Virtel further describes her career that amounts to "living mythology",[2] and that "she graduated from pop hero to mythological wonder".[10]

Providing an explanation in the claims of a near-singularity position as a woman performer, scholars Katie Milestone and Anneke Meyer from Manchester Metropolitan University wrote that "she has been heralded as a 'unique female' figure because of the control that she exerts over her identity".[11] This cohabits to what editor Liz Brewer, in an interview with The Independent said, that a lot of women do, what Madonna does, but "the difference is that she translates it into a phenomenon".[12] Also, author Marjorie Hallenbeck-Huber said "everything Madonna does is extreme".[13] At her profile in The 100 most Influential Musicians of All Time (2009) by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., editors proclaimed she "achieve levels of power and control unprecedented for a woman in the entertainment industry".[14] Gene N. Landrum, author of Profiles of Female Genius: Thirteen Creative Women who Changed the World (1994) wrote that "Madonna has been able to impact her industry as much as any woman in history".[15]

A group of observers like publicist Michael Levine and professor Thomas Ferraro agreed that another significance in Madonna's career is never doing the same thing twice;[16][17] virtually and literally or at least in a big part of her career. In this vein, British journalist Bidisha said that the singer has "no interest in nostalgia".[18] Writer Matt Cain also shared similar thoughts praising her because she "never wanted to be seen as a nostalgia artist".[19]

Transcending boundaries of music and popular culture[edit]

To American writer Christopher Zara, Madonna symbolizes "one of those rare artists who forced the world to conform to her".[20] For Janice Min, editor-in-chief of Billboard she "is one of a miniscule number of super-artists whose influence and career transcended music".[21] Her music alone, played a second role for those who were interested in discussing what she means, approaching Madonna's work from a variety of perspectives.[22] As editor of 100 Entertainers Who Changed America (2013), wrote that "her music alone cannot tell the full story of Madonna's colossal success and influence".[23]

Another group agreed that she transcended her roles as an singer and pop culture symbol, and this include American essayist Chuck Klosterman which said "Madonna's status is no longer connected to music or sales".[24] Canadian professor Karlene Faith observed what she calls "Madonna's peculiarity" because "she has cruised so freely through so many cultural terrains", becoming in a cult figure in many subcultures.[25]

In terms of transcending her pop cultural status, in the 20th-century for instance, Robert Christgau sees Madonna as a pop cultural symbol but also extended his vision that she transcended it.[26] Decades later, Russell Iliffe from PRS for Music concluded that she "transcended the term 'pop star' to become a global cultural icon".[27] She was also described as the antithesis of the manufactured pop star.[7]

In 2015, an editor from El Cultural felt that she "surpasses the laws of physics, time, popular culture, and even metaphysics", and becoming at the same time in a historical figure.[28] Others observers like academic Camille Paglia concurred that she is a "historical figure".[1] For her part, professor E. Ann Kaplan called her as a "historical subject".[29]

General spectrum of Madonna's cultural significance[edit]

She's a major historical figure and when she passes, the retrospectives will loom larger and larger in history.

—Academic Camille Paglia on Madonna (2017) in a feminist perspective.[1]

Academic Camille Paglia presaged in the late-20th century, that "historically people will see the enormous impact that Madonna has had around the world".[12] In 2018, The New York Times writers described her impact as "broad and deep influence".[9] Romanian professor Doru Pop at Babeș-Bolyai University adds that her cultural impact has been "extensively analyzed by many authors".[30] Editors of Encyclopedia of Women in Today's World, Volume 1 (2011), summed up her cultural meaning:

Madonna's cultural influence has been profound and pervasive, as her multiple transformations and controversies have attracted the attention of numerous scholars working in a variety of fields, namely feminist and queer theory, cultural studies, film and media studies. Scholarly debates about Madonna encompass a broad of spectrum of topics ...[31]

Eduardo Viñuela of University of Oviedo in conversation with Radio France Internationale (RFI) summarizing that "analyzing Madonna" is to delve into the evolution of many of the most relevant aspects of society in recent decades.[32] In a similar suggestion, Jock McGregor of Christian organization L'Abri concluded that "by looking at her life and what she symbolizes we can learn much about the values and weaknesses of our culture. We may even learn something about ourselves".[33]

To professor Lisa N. Peñaloza, she is a "veritable cultural production industry".[34] Within the compendium The Madonna companion: two decades of commentary, American poet Jane Miller proposes that "Madonna functions as an archetype directly inside contemporary culture" and she compared its with the Black Virgin.[35] In the description of American author Strawberry Saroyan, Madonna is a "storyteller" and a "cultural pioneer". She stated: "Madonna's ability to take her message beyond music and impact women's lives has been her legacy".[36]

William Langley from The Daily Telegraph feels that "Madonna has changed the world's social history, has done more things as more different people than anyone else is ever likely to".[37] Marissa G. Muller from W remarked that "Madonna has left her mark on every facet of culture", further adding that "the world would look very different without Madonna in it".[38]

Timeline: 20th and 21st centuries[edit]

We can feel the effect of the changes she triggered in our everyday life.

—British sociologist Ellis Cashmore (2018).[39]

There was a general agreement that Madonna reflected society of her time during most part of the 20th century and as cultural critic Greil Marcus has said "she is undeniably part of our culture".[40] Professor John Izod of University of Stirling once said that she can be seen as a "hero of our times".[30] In 2000, writer Rodrigo Fresán described her as "the mirror of our days".[41] In similar veins, American professor Marjorie Garber stated that "perhaps more than any other [she] has read the temper of the times".[42] In 1993, French editor Martine Trittoleno commented that "more than a witness of the epoch, she is an active reflection of it".[43]

According to British author George Pendle, she defined a way of living in the 1980s and 1990s, and this led to consistently described her as a "cultural icon".[44] She was deemed as "a full package of a way of living".[45] Venezuelan writer, Boris Izaguirre commented that "there is a 'Madonna generation' of people who have grown up with her".[46] In 1998, writing for The New York Times Ann Powers suggested that Madonna worked as "a secular goddess, designated by her audience and pundits alike as the human face of social change".[47] Indeed, some scholars described Madonna around this time as "a barometer of culture that directs the attention to cultural shifts, struggles and changes".[48]

In 2002, British academic researcher Brian McNair proposed that "Madonna more than made up for in iconic status and cultural influence".[49] Many years after, her status as a cultural icon is acknowledged in all press accounts according to authors of Ageing, Popular Culture and Contemporary Feminism (2014).[50] In 2018, British sociologist Ellis Cashmore said that "we can feel the effect of the changes she triggered in our everyday life".[39] Bob Batchelor, assistant professor at Kent State University retroactively viewed that no artist of the 1980s "had a larger effect on the cultural landscape than Madonna".[51] In a similar suggestion, editors of The Rough Guide to Rock (2003) made a comparison to other artists of the 1980s, concluding that "nobody changed people's lives the way Madonna did".[52]

Madonna as a mythological-like modern figure[edit]

In 2009, art organization MiratecArts commented that "her influence is so powerful that it extends deep into the subconscious world of imagination, fantasy and dreams".[53] Authors of Mythic Astrology Applied: Personal Healing Through the Planets (2004) wrote in this regard: "Many men and women have reported Madonna appearing in their dreams. As she has become a living archetype in our culture, it is no wonder that this is so".[54] American author Mark Bego informed the case of an artist named Brent Wolf which confesses he dreamed of her every night for five years.[55] Sandra Bernhard is another example documented, as she reported dreaming about Madonna more than anyone "I know (or don't know"); and "somehow she's indelibly written into my subconscious".[56]

Kay Turner, a folklorist scholar,[57] covered this topic in her book I Dream of Madonna: Women's Dreams of the Goddess of Pop (1993) which is about the dreaming of 50 women on Madonna.[58] Writers such as Lucy Goodison and Alice Robb have noted Turner's research on Madonna,[59][57] and this led to Robb conclude that many of these woman found "emotional support in their Madonna dreams, waking with a sense of peace or resolution that persisted in their real lives".[57] In I Had the Strangest Dream...: The Dreamer's Dictionary for the 21st Century (2009), author Kelly Sullivan Walden interpreted dreams of her, saying "then you are tapping into your rebellious creativity and transforming/reinventing yourself".[60]

In Doing Gender in Media, Art and Culture (2009), scholars of Utrecht University noted Guilbert's analysis on Madonna as a "postmodern myth", adding that she is "a privileged source" of mythology.[43] Professor John Izod related Madonna to numerous Roman and Greek mythological figures.[61] Andy Koopmans, in his biography Madonna (2003) observed that she became in a "cultural obsession".[62] American journalist Ricardo Baca described that "to some, Madonna is a divine creation —an otherworldly gift to the masses in the form of an incessantly morphing entity".[63] On other reports, some deemed her as a "postmodern deity".[64]

American culture[edit]

Identified as an "American icon", her impact in the American culture has been articulated both by Americans and international observers. For the academic and music critic Gina Arnold, her primary contribution to her national culture has been musical.[66] In Fresán's view she is one of the "classic symbols of Made in USA".[67] In a course devoted to her at the University of Oviedo, a musicologist taught that her history and evolution is "comparable" and can be useful to analyze the historical development of the United States.[68] French academic Guilbert proposes that "America knows more about Madonna than about any passage of the Bible".[69] Scholars Johan Galtung and Daisaku Ikeda giving a perspective of the United States history commented: "US business and the hyper-successful US plebeian culture, outranking Christianity with its Penta-M: Mickey Mouse, Madonna, Michael (Jackson), McDonald's".[70]

One of the main impacts of Madonna in American culture was in sexuality terms and for freedom. As Ann Powers, said that "intellectuals described her as embodying sex, capitalism and celebrity itself".[47] Writer Sara Marcus concurred that she "brought the changes to American culture" further adding that "her revelatory spreading of sexual liberation to Middle America, changed this country for the better. And that's not old news; we're still living it". Marcus also concluded that Madonna "remade American culture".[71] Scholar Frances Negrón-Muntaner opined that on a "global scale", she embodied the freedom, in/morality, and material "excess" of (white) America.[65] Historian professor Glen Jeansonne gives his point saying that she "freed Americans from their inhibitions and made them feel good about having fun".[72] For Scottish author Andrew O'Hagan "Madonna is like a heroic opponent of cultural and political authoritarianism of the American "establishment".[73]

Professor Thomas Ferraro, puts in context the 1980s as a background saying that "no one was more important to the culture as whole than Madonna" declaring her as a "miracle worker, and wonder woman" and having the faith healer of Ronald Reagan's divide and—conquer American, for its youth especially.[74]

Globalization[edit]

Mass and popular culture[edit]

One of the great conundrums of the internet era is pop culture's short memory[...] But Madonna made real cultural change, and caused a few cultural crises, over and over again.

—Caryn Ganz of The New York Times on Madonna (2018).[9]

To many observers, she is more a pop icon rather than a musician, as critic Stephen Holden once pointed out: "Madonna is still much more significant as a pop culture symbol than as a songwriter or singer".[75] Professors Santiago Fouz-Hernández and Freya Jarman-Ivens, noticed that she reveals "to be an ideal focus for the developing critical resources of popular cultural theory".[76] Professor Abigail Gardner at University of Gloucestershire, wrote that perhaps more than any other pop star, Madonna "holds a privileged place" in the studies of popular culture.[77]

An array group of commentators have pondered her influence in popular culture. American writer Gayl Jones even used the term "the Madonna culture".[78] In Masquerade: Essays on Tradition and Innovation Worldwide (2014), professor Deborah Bell at University of North Carolina wrote that her impact "on pop culture is immeasurable".[79] Commemorating two decades of her influence, Harper's Bazaar in 2003, held that "the ultimate pop-culture icon('s) ... influence is endless".[39] Writer Matt Cain, is from the idea that "without her, from music to fashion to the whole concept of celebrity, today's pop culture landscape would simply not exist as it is".[80]

Madonna's popular culture contributions have been praised. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, argues that she is the first multimedia pop icon.[81] In 2019, The A.V. Club editors commented that as she "is modern pop's original icon" her influence will be "shared, enjoyed, and debated for decades to come".[82] In this vein, sociologist Cashmore said that "even allowing for exaggeration, the point is that Madonna changed how the game works".[39] Cashmore's justification goes on to suggest that even if she was not single-handedly responsible for moving the tectonic plates of popular culture, "there is a sense in which she was an archetype: others who aspired to become celebs were going to have to follow her example. Conspicuousness was everything".[39] Noah Robischon from Entertainment Weekly has concurred that she "has defined, transcended, and redefined pop culture".[83]

Due Madonna's staying permanence in popular culture terms, a multitude of commentators deemed her as a "foremost figure", and also gave her an "unusual" status compared to almost any other entertainment figure. In the late-20th century, academic Gina Arnold compared Madonna with other artists such as Michael Jackson and Bruce Springsteen, saying that "her longevity alone proves which one of those three artists truly altered the face of popular culture".[66] Across the 21st-century, supporting comments include columnist Gail Walker of Belfast Telegraph, who in 2008, compared to her with contemporary fellows or newer artists, and this led him to conclude "she is from an entirely different universe", adding that "not even male icons have stayed at the front of popular culture the way she has".[45] A decade later, in 2018, Rolling Stone staff remarked her "ability to stay at the center of pop culture for longer than nearly anyone".[84]

In 2012, Latin critics like Víctor Lenore perceived her as the most influential presence of popular culture at that time of writing.[85] In 2015, a scholar from program "Research in the Disciplines" of Rutgers University said that "Madonna has become the world's biggest and most socially significant pop icon, as well as the most controversial".[86] In 2018, The Observer columnist Barbara Ellen called her the "pop's greatest survivor",[87] while years prior, Elysa Gardner of USA Today named her "our most durable pop star".[88]

Musical impact[edit]

Musicianship[edit]

Music critic J. D. Considine, wrote in 1996, that along with Michael Jackson, Madonna redefined our notions of "artistic impact".[89] For a long, Madonna scholarship was steered away from any serious consideration of her music,[90] especially the area of musicology.[91] American musicologist Susan McClary made an important step, as some argued she presented the first musicological article to discuss Madonna as a serious artist in the early-1990s.[91] At any rate, critical studies on her contributed in "understanding of the role of technology in relation to contemporary popular music".[92] Madonna also proved bring a different value for female performers, as music critic Robert Christgau puts it:

[...] the world Madonna made—a world in which female vocalists are obliged to be far more glamorous than the "girl singers" who rose up after the big band bubble popped..[93]

To some writers, she is a much "underrated musician and lyricist".[94] Writing for i-D, Nick Levine said: "If you're hoping for Madonna Sings the Great American Songbook, you don't really get her as an artist".[95] Madonna's music is remembered not for its technical complexity but for the accompanying visuals.[96] Stan Hawkins, a musicologist at University of Oslo, decries criticism towards Madonna's music like Jeremy Beadle's comments, arguing that fails to acknowledge her musical reflexivity in any critical enough manner.[90] In Hawkins's view, "her musical texts should not be dismissed in view of their 'simplistic' formulae".[97]

Barry Walters from Spin suggests that what she does best is music, and it's usually left out "when we talk about Madonna". He also said that her consistency suggests something few have noticed about her: "She's a great songwriter. No matter who helped write them, all her hits have that unforgettable Madonna-stamped hook".[98] A year later, in 1996, Gina Arnold similarly stated that her music has a personal injection, noting her continuity and consistency, concluding that "compared to other artists of her ilk, Madonna's vision is incredibly broad".[66]

Emirati editor Saeed Saeed from The National said that "Madonna's worst albums are considered a solid offering when compared to other artists".[99] According to Marissa Muller from W, Madonna helped in normalize "the idea that pop stars could and should write their own songs".[38] Xavi Sancho of El País, said "the releases of this woman are not mere musical and commercial events", but rather exercises that marked the way forward.[100]

Particularly, American editor Annalee Newitz commented in the early-1990s: "Madonna is not a musician. Certainly, she achieved fame within the music industry, but perhaps it might be more accurate to say that she began to be famous within the music industry".[101] American music critic Steven Hyden summarized:

[...] from the beginning of her career, Madonna has been primarily defined not by her music but by her ambition and her ability to present herself in visually interesting and ever-changing guises. There talking points have been repeated in pretty much every magazine profile ever written about her.[102]

Voice[edit]

In 1986, Dr. Karl Podhoretz of the University of Dallas called her a "revolutionary voice who has altered the very meaning of sound in our time".[104] Decades later, in 2013, Rolling Stone described her as "the most important female voice in the history of modern music".[103] Dutch linguist Theo van Leeuwen cited her as perhaps "the first singer who used quite different voices for different songs".[105]

British writer Lucy O'Brien noticed that "over the years many have criticized Madonna's vocal ability, saying she is a weak singer".[106] Another group of commentators, however, have disagreed with this, praising both her voice and versatility in music. O'Brien cited Jon Gordon, a guitarist whose declared that "she was very good at making her vocal limitations work for her", as well "she's a strong interpreter and she doesn't over-embellish things".[106] In this group, Christopher Rosa from VH1 manifested while she has been known to lip-synch, she "can sing" adding that "the proof is in the very-much-in-tune pudding".[107] Other group have praised the fact becoming a musician was never her initial intention. In fact, her usage of the voice and self-transformation was noted as "paramount", noting Madonna's vocal metamorphosis has "proven to be a central and yet under-theorized aspect of her career".[91] Another supporter is Sal Cinquemani from Slant Magazine.[108]

Scholars Andy Bennett and Steve Waksman have also analyzed the cliché associated with her vocals. They asserted "for pop singers in the style of Madonna, brilliant singing ability is not of utmost important", and this contrast to Africa-American artists of soul or R&B, "whose considerable vocal skill is a crucial aspect of their success".[109] In one conclusion, they pointed out that the fact that listeners can sing along to Madonna with ease, can hear themselves reflected in her voice, and can, perhaps, imagine themselves in her place, are all significant to her role as a pop star.[109]

Music contributions impact (genderless)[edit]

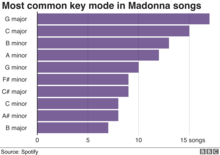

Her contributions to the music industry have been appreciated. Associate dean for Penn State, Jacqueline Edmondson stated that her continued importance is that "her legacy is important to understanding issues surrounding gender and the music industry in the twenty-first century".[110] She has been credited to popularize various music genres and styles. Arie Kaplan called her a "pioneer" in popularize subgenre of dance-pop.[111] Madonna also popularized dance music, and played a major role for the concept of remixes.

Constantine Chatzipapatheodoridis, a Greek adjunct lecturer at University of Patras, concurred that "Madonna's cultural impact helped shape the contemporary music stage, in terms of sound and image, performance, sex and fandom", as well reinvention.[112] Another consideration came from author Marshawn Evans, who wrote in her book S.K.I.R.T.S in the Boardroom (2013) that Madonna has "revolutionized how music is performed, delivered to the masses, purchased, packaged, downloaded, and even simulcast across a variety of cutting-edge platforms".[113]

Others credited Madonna to paved the way for revitalizing pop releases and how artists were marketed. In this regard, Slant Magazine's Sal Cinquemani commented that Madonna "has single-handedly changed the way artists and music are consumed".[114] Thomas R. Harrison, an associate professor of music business and recording at Jacksonville University also concurred that the singer changed the way pop artists were marketed.[115] Erica Russell from MTV stated that Madonna helped shape the way pop artists release music adding that "reignite interest in the art of the concept album within mainstream pop" after the decline of the rock-oriented concept album in the 1980s.[116]

Impact on women's music history and stages of dance, pop and rock[edit]

Madonna is commonly credited as the first female musician to have complete control of her music and image by a wide group of observers, which includes Edna Gundersen, Stephen Thomas Erlewine or Roger Blackwell.[117][118][119] Batanga Media's editor Ana Laglere provides an explanation saying before Madonna, record labels determined every step of artists but she introduced her style and conceptually directed every part of her career.[120] Author Carol Benson commented that the singer entered the music business with definite ideas about her image, but "it was her track record that enabled her to increase her level of creative control over her music".[121] Discussing the gender boundaries of that time, Francesca Cavallo and Elena Favilli have explained that female artists would generally let "their male managers, producers, and agents make most of their decisions for them. Not Madonna".[122] Mary Cross said "Madonna is not the product of some music industry idea, but her own woman".[123]

Others have credited her presence for "changing", "revolutionize" or "paving the way" for women's in contemporary music history, and also regardless gender, commonly for dance and pop stages, and even for rock.[124][125][107][111][126] Her figure was summarized by authors of Ageing, Popular Culture and Contemporary Feminism (2014), arguing that she "is widely considered to have defined the discursive space for examining female popular music".[50] In the Encyclopedia of American Social History (1993), authors described: "No singer better illustrates the new images of women in contemporary rock and pop than Madonna".[127] British sociologist David Gauntlett cited another author's view: "Madonna, whether you like her or not, started a revolution amongst women in music".[128] Joe Levy, Blender editor-in-chief makes a similar argument in discussing this, saying: She "opened the door for what women could achieve and were permitted to do".[117]

Her influence is still felt in the way modern female musicians are viewed, regarded and accepted.

—Erik Thompson from City Pages (2011).[129]

In regards rock-style arena, and according to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, she became an early embleme of "'women in rock' helping dissolve gender boundaries in the music business to the point where that catchphrase has become unnecessary and even a bit anachronistic".[130] She was also described as the catalyst that changed music from being rock-centric to being dance and R&B-oriented.[125] Although Madonna is not the first pop female artist, Deutsche Welle staff credited her as "the first woman to dominate the male world of pop".[131]

According to Tony Sclafani from MSNBC, "the word 'female' is significant" in the assessment of Madonna "because she presented herself in a fresh way for women artists".[125] Sclafani concluded that with female artists everywhere these days, it's easy to forget how revolutionary Madonna was. He explained that the Beatles changed the paradigm of performer from solo act to band. And Madonna changed it back, with an emphasis on the female.[125] In 2014, music journalist Diego A. Manrique, noted the dominance on record charts by female artists, calling them as Madonna's heirs due her influence on them, concluding that in terms of popular culture we are living in a "Madonna era".[132] Like Manrique and Sclafani, British music journalist David Hepworth stated that "most of biggest of the pop music" are women and Madonna "is the person who proved that this was possible, who opened up a new world for them to grow into".[133] Gillian Branstetter of The Daily Dot found this as very significant for the context in which Madonna thrived when she appeared back in the 1980s, where "the vast majority of the top artists in the world were men".[134] In 1987, Ken Barnes from Radio & Records, commented that Madonna has inspired a vast array of (mostly) female vocalists, to aspire to stardom using only their first names.[135]

Influence on other artists[edit]

Madonna's influence reigns supreme on today's artists [...] Madonna changed the role of women in pop music. She gave women power, the ability to do more than just record dance hits, and brought about change in the industry that gave birth to every single pop star today.

—Culture columnist Art Tavana writing for company Spin Media (2014).[124]

Madonna's influence on others artists (most notable in female performers) is a well-articulated theme in both music journalism and scholarship discourse. She herself "is aware of the influence she has" on others.[136] Aside commentaries from critics, an array group of female artists widely acknowledge the important influence of Madonna on their own careers.[109] In this regard, The O2 said that "other artists aren’t afraid to admit their admiration for her".[137] Branstetter said that Madonna "is scattered through every major act" and her influence is "almost smothering in its totality" in her native country.[134] Mary Cross, in a similar statement said that her "influence is undeniable and far reaching".[138] An author noticed that "artists still use her ideas and seem modern and edgy doing so".[125]

Authors like Branstetter are aware of the influence of Madonna's fellow in the musical landscape,[134] but like Branstetter or Nick Levine,[95] it was noted even though "she didn't set the template alone", she created the rules of engagement now followed by everyone.[95] Billboard staff reinforced this, comparing her to others, saying "Madonna is still the one who most set the template for what a pop star could and should be".[139] In the case of various artists, an observer noted that are influenced by Madonna more than any other artist past or present.[124] Erik Thompson from City Pages commented that those "that denies that Madonna is an influence or an inspiration to them is either lying or simply ignorant of music history".[129]

She was credited even to established a matriarchy in the pop scene.[140] As her influence in pop stars drew media attention and she has been called as the "Queen of Pop", MTV's Madeline Roth ranked in 2010, "princesses of pop who have earned Madonna's blessing" adding that she "has voiced her disapproval for pitting women against each other".[141]

British sociologist David Gauntlett studied the influence of Madonna on other performers and proposed four key themes that she established as central, and that have since been used and emphasized by her successors (and imitators).[142] Media outlets and authors as various as Ann Powers, Diego A. Manrique and la Repubblica have called numerous female performers as "Madonna's daughters" or her "musical daughters" due her influence on them. In this regards, Gauntlett commented that "many of them are Madonna's daughters in the very direct sense that they grew up listening to and admiring Madonna, and decided they wanted to be like her. Most of them have said so explicitly at some point".[128] A subject also of listicles, MTV Latin American created a ranking with the intention to find her "heir".[143]

Superlatives and status as a musician[edit]

It is not uncommon to read in the most prestiges media that she is the most influential woman in contemporary music.

—Announcer Juanma Ortega on Madonna (2020).[144]

Madonna has been discussed with euphemism by numerous authors or media outlets, as "perhaps" and "arguably" the "greatest" female artist as well the most "influential" woman in music history; either in general female terms or for pop woman stage.[145][146] Ben Kelly of The Independent commented that she has "ensured her legacy as the greatest female artist of all time".[147] Norman Mailer proclaimed her as "our greatest living artist".[148] Music outlets such as MTV or BET have deemed her as the most influential figure or woman in American music history as well.[149][150]

Multiple reviewers have deemed Madonna to have a distinctive position. Views came from both 20th and 21st centuries. In 2021, Saeed Saeed summed up this status saying that "we do hold her to a higher standard".[99] In the perception of Susan Sarandon: "The history of women in popular music can, pretty much, be divided into before and after Madonna".[151] In 2018, Billboard staff made a similar statement, saying that "the history of pop music can essentially be divided into two eras: pre-Madonna and post-Madonna".[139]

In the lens of listicles, she has been placed high in several music-related lists, topping many of them. She was ranked as the greatest woman in music by VH1, both by their staff (2012) and their public (2002).[153][154] In 1999, she was crowned as the "best female artist of all time" in a poll conducted by HMV and Channel 4 in the United Kingdom.[155]

In addition to be certified by the Guinness World Records as the best-selling female artist in music history,[152] they also recognized her as "the most successful female artist", a title updated from the late-20th century to the early-21st century.[156] Similiar superlatives are found in the academic world, with Canavan Brendan and Claire McCamley summed up in a 2020 article for Journal of Business Research, that "she's probably the most successful female music artist ever in terms of her record sales, tour receipts, brand recognition and longevity".[157] In the suggestion of British musicologist David Nicholls: "Madonna became the most successful woman in music history by skillfully evoking, inflecting, and exploiting the tensions implicit in a variety of stereotypes and images of women".[158] In 2015, musicologist Laura Viñuela taught at University of Oviedo in a course devoted to her, that she "is the only woman who has such a long and massively successful career in the world of music".[68]

Madonna was a long-time the wealthiest woman in music, and even briefly for the entertainment industry recognized by Forbes.[159][160]T She also featured in several Forbes earning lists as the highest grossing female artist during various years across four consecutive decades. As of 2016, Madonna remains the highest-grossing solo touring artist in history.[161] Madonna also attained superlatives related to her business success; biographer Chris Dicker summarized that it has been said that she is "the most successful woman in the history of the music business".[162] Deutsche Welle called her "music business' most successful woman",[131] while David Horowitz and professor Peter N. Carroll have concurred that she is "the most financially successful female entertainer in history".[163]

Impact in the film industry[edit]

Only Madonna's inability to conquer movies has kept her from being acknowledged as the greatest entertainment phenomenon ever

—Profiles of Female Genius: Thirteen Creative Women who Changed the World (1994).[15]

Madonna started in the film industry before became a musician. She maintained an acting career alongside her musical one during various years.[164] Her case has been analyzed from the lens of film studies, as was noted by British cultural theorist Angela McRobbie, and this also include the perspectives of feminist film theory.[165] Her film career as a whole has been the subject of extensive comments, most notably because she has been lambasted as an actress.[164] Her films, have come in for more than their fair share of criticism.[166] In this respect, Italian writer Francesco Falconi commented Madonna was even criticized a priori before her films were premiered.[167]

Madonna's film career was described by Robert Ham of Portland Mercury and Juan Sanguino from Vanity Fair as an "unusual" case in Hollywood.[168][169] American novelist Norman Mailer also said she was unusual among celebrities for choosing film roles that didn't boost her status.[170] For Landon Palmer, assistant professor at University of Alabama, Madonna's film career epitomized the discordance between older and newer models of stardom, with the studio-era Hollywood and MTV-era and beyond,[171] further adding that her case, "entails many of the filmic trajectories of music stars".[172]

Critical analysis also discussed a variety of reasons of her commercial and critical failure of many of her films, while others even defended her acting, or at least many of her films in retrospective noting "notable examples".[31] British magazine Stylist confirmed that she has divided critics,[173] and others called her film career at best, as "mixed" when discussing these things.[174] In Liz Smith's view, "part of the problem was that from the start, so much was expected of her" and watching her early impressive music videos, "how could Madonna not become a major screen star?".[175] Professor Palmer, also included her success as a video star, commenting that "were not readily transferable to commercial filmmaking".[172]

There is a general agreement, what Madonna does better is a role when she is being Madonna, or a very similar character with her persona.[168][176] Guilbert as others do, argued that only her movies sometimes escape her control, unlike her other professional projects.[177]

Feats[edit]

Madonna's cinema works have also made an impact in certain ways. At first instance, several of her films have been exhibited in museums around the world, notably the Pompidou Center in Paris, as modern works of art.[55] Also, Evita is reported to be the first (and perhaps only) American film to be screened at North Korea as part of the Pyongyang International Film Festival.[178] In 2016, movie theater Metrograph, premiered Body of Work: A Madonna Retrospective, a devoted five-days retrospective to celebrate her film career and particular position as an actress.[176] On the contrary, in 2009, it was presented Almost Human: Madonna on Film a festival comedic tribute at Central Cinema hosted by David Schmader as a celebration of bad acting of Madonna.[179] Some of her films garnered a cult status amongst different audiences, including Madonna: Truth or Dare,[180][181] and Desperately Seeking Susan.[182][183]

In her filmography, Truth or Dare found a greater social significance as it is commonly attributed to anticipate many things in popular culture. Guy Lodge of The Guardian deemed this work as her "most significant contribution to cinema".[184] Joe Coscarelli from The New York Times commented it "presaged the celeb-reality complex".[181] The film crossed the boundaries of the "real" Madonna and the "celebrity" showing how she is in control of every aspect of her career.[185] This perception of a star, was something unusual at that point as celebrities of the magnitude of Madonna, were prized for their "distant mystique", not their "familiarity".[184] For many ways, this film is often referred as a precursor of the reality television.[80]

Some of her movies enjoyed box-office success, and this include Truth or Dare which ended for a while as the highest-grossing documentary in history, altering the popular perception of "what the concert movie was supposed to be".[186][184] Her movie theme songs and its accompanying soundtrack albums, enjoyed more success than her roles. For example, "Crazy for You", "Live to Tell", "Who's That Girl", and "This Used to Be My Playground" topped the Billboard Hot 100.[187] While she didn't win the category, Madonna is the interpreter of two Oscar-winning themes for the Best Original Song, "Sooner or Later" and "You Must Love Me"

Madonna also found impact within some of her films through fashion. Authors of Social History of the United States (2008) noticed in the case of Desperately Seeking Susan she inspired new fashions for teenage girls.[183] She set the world record in Evita as the most costume changes in a film for a character with 85 times.[152] Professor of cinema studies, David Desser concurred that she "illuminated changes in Hollywood's fashion mettle through her role in Evita".[188] The film was reported to be an influence for the revival at that time of the 1950s-style, and companies such as Estée Lauder and Bloomingdale's launched boutique products inspired in the movie.[189]

Influence on others actors and cinematic works[edit]

She also influenced others films and actors. Is the case of Mexican actress Salma Hayek as she told the press that took inspiration from Madonna for the role in Tale of Tales.[190] Katy Perry did the same for her documentary concert film, Katy Perry: Part of Me.[191] Other actresses reported to be influenced by her, like Anne Hathaway.[192] Madonna has been depicted in other cinematic works, which include the television film Madonna: Innocence Lost. While Maverick was under her control, she made possible for the Chinese film Farewell My Concubine to reach a relatively large American public.[177]

Madonna has been known to take inspiration from other actresses and films during her career. This indeed, impacted in some way the career of some movie stars. A premier example in the eyes of multiple observers, is Marilyn Monroe. Largely thanks to Madonna, Monroe was deemed as "the woman who will not die", as Gloria Steinem puts it, "an ever-present fixture in everyday American culture".[193] Professors Robert Sternberg and Aleksandra Kostić, said that at least in the 1980s, "Madonna's TV-pictured soft-tousled blond hair popularized the sexy, Marilyn Monroe look of the 1950s".[194]

- adolescents in the mid-19990s mistakenly assumed that the painting portrayed the pop music star Madonna (Twenty-Five Colored Marilyns) | Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth 110 (pag 186)

Madonna in the contemporary arts[edit]

Impact in the contemporary literature[edit]

Madonna's authorship[edit]

Some of Madonna's written works have impacted its industry and setting various world records. Professor Landon Palmer concurred that she impacted popular culture via areas that include the publishing realm.[172] Carol Gnojewski, author of Madonna: Express Yourself (2007) wrote that Madonna "has been a prolific writer" and noticed she keeps a pillow book of ideas (a diary or journal), jotting down dreams or poems.[196] Gnojewski called her an "avid diarist", who used material she wrote in her journals as the basis for song lyrics.[197] Professor Mary Cross, called her poems as "confessionals" as she writes them to crystallize her feelings. She even wrote poems to her assistants in gratitude of their help.[138]

Her first book Sex ended as the best and fastest-selling coffee table book.[198][137] It was also the largest initial release of any illustrated book and remains as one of the most in-demand out-of-print publications of all time.[199][200] The social and retail impact of Sex was of far-reaching, that an editor of Entertainment Weekly deemed it as "the publishing event of the century".[201] 20-years later, critic Mark Blankenship concurred that "literature changed forever" after its publishing.[202]

As a children author, two of her books are ranked among the largest publishing titles in history by its number of translations. Along with this, The English Roses represented the largest simultaneous multi-language publication for a book, with a target of more than 100 countries in 30 languages,[203] and the fastest-selling picture book by a debutant children's author.[204] Her success in this literary genre, was noted by Ed Pilkington from The Guardian, in 2006, who believed that she "lured a host of other celebrities and publishers into the [children's book] market".[205]

Madonna's influence on other authors and beyond[edit]

Numerous agents have dedicated a varied of literary works to Madonna. Maura Johnston said that "the appetite for books on Madonna is large, and the variety of approaches writers, editors, and photographers have taken to craft their portraits is a testament to how her career has both inspired and provoked".[206] Various authors, including writers and journalists have commented the influence of Madonna in their career and life. Is the case of writers Francesco Falconi and Matt Cain; the first dedicated his first non-fictional writing to a Madonna biography.[167] There exists devoted articles from journalists discussing her influence on them. Is the case of Natalia Mardero, or one piece from Belfast Telegraph, when in 2018 three of their writers shared her impact on them.[207][208] Others, like novelists Paulo Coelho and Lynne Truss have commented they "admire" and "respect" Madonna.[209][12]

On a broader scale, in 1985, Australian newspaper The Canberra Times quickly attributed to Madonna in "nearly reversed the typical pattern of rock idol analysis".[210] At least from an academic perspective, Madonna is credited in brought pop artists to the foreground of scholarly attention, as well her academic discipline played a major role for the direction of the American cultural studies.[211][212] A Vice contributor said: "Reviews of her work have served as a roadmap for scrutinizing women at each stage in their music career".[213]

Associate professor Diane Pecknold in American Icons (2006) noticed that she helped to popularize words and phrases in the English lexicon.[212] She included the term "wannabe" used by Time magazine back in 1985 to describe the Madonna wannabe phenomenon. Another inclusion was the title of her first major film role, Desperately Seeking Susan which produced a new idiomatic phrase considering the newspaper headlines.[212] People staff agreed that she "coined" the term for "Get rid of it".[214]

Measurement of literature about Madonna[edit]

The literature about Madonna is "extensive" as noticed professor Robert Miklitsch of Ohio University.[215] Stephen Brown from University of Ulster defined that "the literature on Madonna is almost mind-boggling in its abundance".[216] Pamela Church Gibson of London College of Fashion wrote in Fashion and Celebrity Culture (2013): "I realize that there is a veritable library of literature available on the subject of Madonna".[217]

In this journey, Madonna has been labelled by Douglas Kellner as "the most discussed female singer in popular music".[218] Similarly, in 1994, Landrum attributed the press in making her the most debated female in modern times.[15] Editors of Ageing, Popular Culture and Contemporary Feminism (2014) deemed Madonna as "the most studied, critically acclaimed, derided and analysed of the performers".[50] Overall, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame called Madonna as one of the most "well-documented figures of the modern age".[81]

Sexton, noticed such saturation commenting that an author can't even write a book-length essay on the writer he's obsessed by without mentioning Madonna's name.[75] A Time contributor once said: "Cut Madonna, and ink comes out".[219]

From academy[edit]

Alongside the popular literature, Australian historian Robert Aldrich, said that Madonna is a "performer of inimitable ubiquity" in the academia as she "has saturated the pages of academic journals".[220] Associate professor José F. Blanco, wrote in The Journal of Popular Culture that "it can be argued that Madonna is overexposed in academic research".[221] To Alina Simone, "there is no dearth of material about Madonna, but an overwhelming excess".[222]

Correspondence with critics[edit]

Madonna's relationship with the critics became in a well-established and crucial aspect of her career.[91] Educator Francine Shapiro as do others, commented that many critics "love to hate" her.[223] She also has defenders against her critics, like gossip columnist Liz Smith, who Madonna herself thanked many times.[170] Editor Marc Andrews noticed Erotica's track "Words" as a "protest against the things written about her" and this led him to conclude Madonna was ahead of her time here calling out what pre-Internet were called critics and nowadays are trolls.[224]

An author suggested that she was at least one step ahead of her commentators, as with Madonna there was a constant-danger within the real of critique or commentary.[225] American journalist Jon Pareles said that she has "labeled herself more efficiently than any observer" since the beginning of her career.[226] J. Hoberman goes further saying that she "directs her critics, the millions of sociologist, psychologists, and students of semiotics who have made her the world's biggest pop star".[225]

Authors working on Madonna[edit]

- Matthew Rettermund: my publishing career was born (Encyclopedia Madonnica)

- How Marc Andrews went from Mediaweek to world of hitmakers Kylie and Madonna

- Madonna And Me: Our Writers Reveal The Queen Of Pop's Personal Impact - Huffinton Post

- AVClub_ the most widely discussed, analyzed, and debated pop star to emerge since the 1960s.

Impact through religious imagery[edit]

Madonna has also been pondered in the lens of religious studies, as American professor Arthur Asa Berger confirmed the singer has raised to the authors many questions about religion.[42] Professor Pellegrino D'Acierno at Hofstra University, wrote in The Italian American Heritage (1998), that "so many critics seem to love to discuss Madonna's obsession with religion".[227] Especially in the 1990s, she was a favorite topic for religious fundamentalists.[228] While many of her works have seen devoted studies of its religion connotations, "Like a Prayer" is perhaps more than any other music video inspired scholarly analysis of its religious meanings.[228]

Analysis[edit]

Anne-Marie Korte from Utrecht University recalls that "religion plays a major role in Madonna's statements and provocations".[43] The resemblance of cults in her career was described by American professor of religion Diane Winston, saying that "the success of Madonna as an international pop star cannot be disconnected from the religious history she created through her relationship to a series of religious authorities —Catholic, Hindu, and Jewish— and who she incited to reply to her ostensible profanations".[229] Canadian professor of religious studies, Aaron W. Hughes summed up that "for Madonna, religion in general and Judaism in particular are inherently divisive and this divisiveness is ultimately responsible for the problems we face".[230] About her first cult contact, Catholicism, author Landrum held that "Madonna has demonstrated an almost messianic desire to rebuke the Catholic Church" and she blames the church for much of society's problems.[15] Authors Peter Levenda and Paul Krassner concurred that probably no person of the 1980s and 1990s in the American popular culture represents better the conflicting spiritual forces that Madonna.[231]

Influence[edit]

Madonna is credited to brought religious symbolism into pop music.[45] Associate professors of Fordham University, discussed in the book Battleground: The Media (2008) that "she popularized the cross as a decorative object for her shows and videos".[232] Historically, she is one of the world's first performers to "manipulate the juxtaposition of sexual and religious themes" according to Jamie Anderson.[233] Helen Weinreich-Haste, noticed this cross-over usage of sexualism and religion, noting that "much has been written about her subversive effect on middle-class and Catholic values",[234] while for academic Marcel Danesi, "perhaps no one has come to symbolize the sacred vs. profane dichotomy more than Madonna".[235]

British-Australian sociologist Bryan Turner wrote that popular religion became a component in the entertainment industry and Madonna "is the most spectacular illustration of this process".[236] Time editor Cady Lang, stated that her "obsession with her Catholic upbringing "has undeniably shaped both the pop culture and fashion landscape".[237] Lang further adds, that there are few figures closely associated in popular culture with religion than Madonna.[238]

She has been largely criticized by religious leaders and followers. American author Boyé Lafayette De Mente observed that millions regarded her as an anti-Christ because she is frequently profaning religious symbols.[239] Contrary, others like professor of religion and Christian follower, Donna Freitas or priest Andrew Greeley have defended her.[240][241] In this regard, a Christian contributor from L'Abri observed that "not all Christians have been hostile".[33] Karl Dallas, said that "so far she has done little more than to use the talents God gave her, and challenged a few sensibilities with them".[33]

Madonna also played a direct role to normalize some spiritual cultural practices in the modern Western society. Is the case of the Jewish mysticism, according to a variety of sources like The Independent.[242] American novelist and former educator Alison Strobel commented that "Madonna had popularized it to the point where it was simple to find a place to go learn".[243] Madonna has been a catalyst for the role of the Kabbalah in Occident to the point to convert it "trendy" according to Australian writer and linguist Karen Stollznow.[244] Media analyst Mark Dice called her the "celebrity face" of this practice.[245] However, associate professors at University of Northern Iowa, found that some charges Madonna in turn a multithousand year old religious study into entertainment.[246]

Author Eric Michael Mazur wrote that "she has almost single-handedly made American teenagers vaguely familiar with Hindu mantras and Jewish kabbalistic".[247] The New York Times concluded she "brought" yoga to the masses.[9] In this line, professors Isabel Dyck and Pamela Moss particularly credited Madonna the popularity of Ashtanga Yoga.[248]

Impact through multiculturalism and identity politics[edit]

- BBC One: There is only one Madonna, Documentary charting Britain's relationship with the pop icon, including the influence she has had on the country's music, fashion and sexual politics.

The Australasian gay & lesbian law journal, in a 1993 article wrote that "it is not possible to read/interpret Madonna without a recognition of elements such as race, class [and] ethnicity. These elements , which themselves are present in almost all of Madonna's texts"[249]

The impact and literature on Madonna was also centered in her relationship with diverse subcultures, even "appropriation" of their elements,[31] and her own cultural diversity (both from ancestors and posterity). Professor George J. Leonard called her "the last ethnic and the first post-ethnic diva".[250] Some authors devoted their studies to a specific race, like bell hooks with the black culture. Overall, her academic branch, the Madonna studies provided a challenge views on racial perspectives,[211] and revealed her as a critical nexus of race.[31]

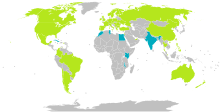

Madonna's footprints have been documented in press accounts in numerous countries, either to discuss her impact or relationship with them. In this scenario, newspaper of record like La Nación (Argentina),[251] South China Morning Post (Hong Kong) and El País (Spain) did in their respective countries.[252][253] Madonna's mapping of the world cohabits with her singing in other languages. Partially or fully, aside of her native English, she also sung in Spanish ("Verás" or "Lo Que Siente La Mujer"), French ("La Vie en rose" or "Je t'aime... moi non plus"), Portuguese ("Faz Gostoso" or "Fado Pechincha"), Sanskrit ("Shanti/Ashtangi") or Euskara ("Sagarra jo").

Critical analysis[edit]

Historically, Madonna deliberately cemented her popularity on ambiguity, thus appealing to not one but many social groups and subcultures.[254] In this regard, American professor Gail Dines concurred that in understanding her, requires focus on audiences, not just as individuals but as members of specific groups.[255] Academic Kellner, even further suggests that the singer "helped bring marginal groups and concerts into the cultural mainstream".[256] This has been a constant in her career, as Cain states that she "has always produced work that has brought marginalised groups to the fore", including black, Latinos, or LGBT people.[80]

One of the academic interrogation of Madonna has focused on her appropriations, subversions and transformations but her motivations in addressing cultural politics are uncertain for some.[257] Some have argued, for example that Madonna's insistence on solidarity with marginal groups and on moving between worlds was "duplicitous".[258] British professor Yvonne Tasker articulates her ambivalence, calling her an "interesting figure to the extent that her appropriation does at times work to question assumptions".[259] Taking her as a paragon, assistant professors Jennifer Esposito and Erica B. Edwards have commented that "pop stars today contend with this legacy and as a result take elements adding 'freshness' to their persona without dealing with the histories and realities the cultural imprints are born of".[260]

Latino and Spanish culture[edit]

Professor Santiago Fouz-Hernández stated that the Hispanic culture "is perhaps the most influential and revisited 'ethnic' style in her work".[254] Before the Latino boom-way invaded the world pop in the 1990s, Madonna released Spanish-inspired works like "La Isla Bonita".[261] Authors of Bitch She's Madonna (2018), commented that American pop singers such Jennifer Lopez, Beyonce or Christina Aguilera replicated it.[262]

In Boricua Pop: Puerto Ricans and the Latinization of American Culture (2004), scholar Frances Negrón-Muntaner, discussed Madonna's impact in the Latin culture of the United States, with a special focus among Puerto Ricans during the 1980s and through the 1990s. She agreed that "Madonna's nod created the illusion of insider status for Latinos of all sexualities in U.S. culture",[263] and deemed her as "last century's American transcultural dominatrix".[65]

According to Negrón-Muntaner, Madonna "came to most successfully commodify boricua cultural practices for all to see".[65] She further adds, Madonna is the first "white pop star to make boricuas the overt object of her affections", producing "a queer juncture for Puerto Ricans representation in popular culture".[65] Also, Negrón-Muntaner concluded in romancing Latinos in this specific way, Madonna made boricua men desirable to an unprecedented degree in (and through) mass culture.[264]

Black culture[edit]

Madonna is typically credited as the first to use black gay culture, in a clear and forward way.[260] In 1990, CineAction! summed up: "Madonna's 'blackness' is a common, though poorly articulated theme of popular press literature".[266] As with other ethnics, Madonna commented about black culture, recalling that she wanted to be black as a child.[109] In her early career, she was subtly marketed as a black artist by Sire Records before revealing her face to the public.[267][268]

Professor Ferraro studied her relationship with black culture, saying that "no white pop star (in the 1980s and 1990s) ever owes more to black male productions, including Reggie Lucas, Nile Rogers, and Stephen Bray, than Madonna".[269] He also concluded that "no diva has spent more time on camera and off with men of color, professionally and romantically involved" and ends describing her as "the most accomplished Italian-to-black crossover artist in history".[269]

Madonna, however, attracted a wide-range of criticism for her usage of black subculture themes, with some seeing it as white privilege. Barbadian-British historian Andrea Stuart concerned that she "deliberately affected black style to attract a wider audience".[270] American historian David Roediger noticed bell hooks' criticism (a famous Madonna detractor), that for her "the image Madonna most exploits is that of the quintessential 'white girl' and to maintain that image she must always position herself as an outsider in relation to black culture".[271] Hooks problematizes that as a cultural icon, Madonna is "dangerous" and called her the "Italian girl wanting to be black".[22] Hooks also charges that the singer "never articulates the cultural debt she owes to black females",[272] proposing that one cannot make sense of Madonna without noting of her benefits taken from the community.[273]

Art historian John A. Walker, also observed criticism from hooks, and concluded that this caused many women of color to dislike Madonna.[265]

- Perhaps that is why so many of the grown black women I spoke with about Madonna had no interest in her as a cultural icon and said things like, “The bitch can't even sing.” It was only among young black females that I could find (hooks)

Asian and other cultures[edit]

Mostly in her 1992–1993 and 1998–2001 periods, Madonna also adopted, modified, subverted and deconstructed Asian (specially Thai, Hindu and Japanese) elements and imagery.[254] She also replicated the practice of hiring Asian and African American backup singers and dancers.[274]

Other observers also noticed the influence of England heritage in her work, as she was married to Guy Ritchie and lived in the United Kingdom for years. However, Madonna's exploration of intra-Caucasian identities has received little academic attention.[275]

Madonna and her usage of other cultural elements impacted industries like fashion. Academics like Gayatri Gopinath and Kellner, noted Madonna's importance in popularizing Indian cultural elements.[276] Kellner, said "although Madonna did not initiate the Indian fashion accessories beauty" she did propel it into the public eye by attracting the attention of the worldwide media.[277] Professor Christopher Partridge, in a similar statement declared that "since Madonna first put Indian cultural symbols on the global fashion map, henna, bindis and Indian sartorial designs have become part of the global popular culture". Further, Partridge suggested that "she ensured the Hindu invasion of Western popular musical space and made South Asian popular culture globally visible".[278]

Italianness and American culture[edit]

Fosca D'Acierno in The Italian American Heritage (1998), noticed "so much has been written about Madonna, but rather little has been about" singer's 'Italianness'".[279] In her analysis, Fosca proposed her as a "vehicle for the expression of many of the qualities that are exclusive not only to Italian" but even more so to Italian American.[279] Professor Ferraro also studied her Italian roots, and commented she "never stops talking about her background".[17]

Musically speaking, she has been classified as one of the Italian American performers that played a "definitive role" in the musical culture.[250] Various critics agree that rather than export US music, however, has imported new (mostly European) trends into the United States.[254] In terms of iconography, US culture does not seem to have played a central role in her work either, according to José Igor Prieto-Arranz from University of the Balearic Islands.[254] For example, she rarely wrapped herself (metaphorically or literally) in the American flag, but has often adopted other flags of convenience.[257]

Impact in fashion[edit]

Impact in feminism[edit]

Sexuality[edit]

Mass media impact[edit]

Madonna studies also centered in the media studies.[63] She largely found an impact in the traditional media, and for scholar José Igor Prieto-Arranz, rather than a singer, she is a global multimedia phenomenon.[280] For professor Ann Cvetkovich, a figure like Madonna reveals the "global reach of media culture".[281] The sizeable studies on Madonna in these areas has been of a large-scale, that authors of academic compendium The Madonna Connection explained that "with Madonna, the extensive tie-in between media scholars" has produced an "exaggerated metacritical level".[282]

Ubiquity: Analogous and digital era[edit]

Pre-internet, before information was a quick google away, Madonna was a rare and precious conduit, a woman who seemed plugged into the white-hot centre of the universe, yet all the while appearing to be her own current

Laura Craik from The Daily Telegraph (2018).[7]

An article from The Charlotte Observer issued in July 1978, covering the American Dance Festival's first year at Duke University in Durham, might be the first notice from the press that Madonna received in her life.[283] The New York Times staff once wrote: "Millions of words will be printed around the globe about her. The controversy, the reviews, the analyses, the gossip, and the photos of the star will complete the phenomenon".[284]

Before the massively use of internet, the volume of media attention Madonna commanded was a feat; only Michael Jackson was noted to rivaled it.[285] In Cashmore's words, she got more saturation media coverage than anyone, present and past.[286] Spanish philosopher Ana Marta González proposed that with her media appearances the singer "would be more culturally significant than most of the people who have changed the course of history or thought".[287] Authors of Madonnarama (1993), wrote that she has come to occupy that large public media attention, that Madonna functions rather like what environmentalists call a "megafauna".[288]

In the mid-late 1990s, Frances Wasserlein was one of the first to devote the presence of Madonna on the Net, documenting literally billions of bytes on web sites all over the world about her.[289] Writing for Vulture, Lindsay Zoladz compared if the internet is our modern religion, then Madonna is its Old Testament God.[290]

Critical analysis[edit]

Others scholars "analyze media-Madonna discourses and representations".[282] Author Tim Delaney suggests what "set the tone for public discourse and analysis" is her perceived "outrageous behaviour".[291] Media scholars such as David Tetzlaff and John Fiske devoted polysemous texts; with Fiske recognizing her as a "site of meanings" and a "rich terrain to explore".[219][292] An author, have remarked that interpreting Madonna has never been only a domain of tabloid media.[293] Cashmore commented that the singer exploited the expansion of media opportunities.[286]

Media manipulation[edit]

Reviewers noticed that Madonna earned a reputation of "media manipulator". American journalist Josh Tyrangiel said that she reached her peak as a such with the advent of her album Like a Prayer.[294] This reputation was notorious on her commentators, as music critic J. D. Considine puts that Madonna was "more media manipulator than musician".[295] At the end, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame asserted that "no one in the pop realm has manipulated the media with such a savvy sense of self-promotion".[81] For critics like Stephen Thomas Erlewine, the public and media manipulation become in one of her greatest achievements.[118]

Media theorist Douglas Rushkoff explained that "Madonna's career has been more dependent on media backlash than it has on positive excitement or artistic achievement in the traditional sense".[284] At the end, British sociologist Ellis Cashmore proposed that "Madonna effected a change" in the manner in which stars engaged with the media.[39] Authors in The Best Value Beauty Book Ever! (2007) described her as "perhaps the most media-savvy female performer ever".[296]

Cashmore further credits in the case with Madonna, that would change the very nature of the media's relation with performers as more than any other artist, Madonna uncovered herself to the media, making it less possible for others to engage the media without baring their all, so to speak. He concludes, we witnessed the effects in legions of young people of massively varying degrees of ability performed in front of tv cameras in often embarrassing attempts to win contests like Pop Idol or American Idol.[297]

Impact through print media outlets[edit]

MTV[edit]

Madonna and MTV simultaneously emerging and rise become synonymous, as well both had contributed substantially to each other's success.[298] Arie Kaplan said that "she was the first artist to really use MTV to establish her popularity".[111] Another supporter of this view, is editor Carrie Havranek who concluded that "quite simply there was no one else like her".[299] However, biographer Chris Dickers stated that she transcended her "MTV persona",[162] and another observer adds that she is "the first pop star of the MTV era to remain prolific at 60".[285]

Rolling Stone editors Bilge Ebiri, Maura Johnston among others, concurred that "no artist conquered the medium" like her as "Madonna's music videos defined the MTV era and changed pop culture forever".[300] Jim Farber of The New York Times, also remained that she gave MTV Video Music Awards their defining tone at their inaugural ceremony in 1984.[9] Same editor said that "Madonna's clips have given the network more media headlines than any other artist".[9]

Madonna's fame impact[edit]

If Madonna standardized the script for the reception of — and debates surrounding — pop stars, she also broke and commented on taboos with special impish aplomb.

Bego among others, have seen Madonna more as a star rather than a public performer, singer or actress. Professor Martha Bayles said that "is in the extramusical realm that Madonna really made her name".[302] Robert Christgau commented that "celebrity is her true art", and once said her fame is so far-reaching that it is difficult even to measure.[212]

She also become in one of the most "recognizable names in the world", beyond music.[81]

Timeline[edit]

Madonna as the most famous woman in the world[edit]

Madonna has been slightly described as "the most famous woman" by numerous publications during five consecutive decades (1980s—2020s). This media label has been also commented by numerous agents, including scholars.

- Other similar titles

In regards music fame terms, Alina Simone, called her in Madonnaland as the "the most famous female performer of all time".

- “Since her career began at roughly the same time as the behemoth network, Madonna and MTV are forever ... “As our girl morphed [into] the world's most famous woman, so, too, did MTV evolve into a sleek superpower. The History of Music Videos - Page 35 by Hal Marcovitz (2012)

Cultural effects and responses[edit]

The concept of producing stars rather than waiting for them to emerge stayed largely intact until the mid-1980s. Madonna, more than any other entertainer, realized this. And she not only epitomized this, but helped it materialize.[303]

Commercial influence[edit]

She's been spectacularly successful [...] She's also garnered mammoth sales from concerts, movies, books and videos.

—Business professor Oren Harari.[304]

Madonna's semiotic and impact extended to the marketing and business schools community as experts pondered her cultural impact applying their areas of expertise. For some academics she became a central image in studies of commercialism.[305] Morton concurred that her "success has certainly impressed the business community".[306] For scholar Douglas Kellner, Madonna's chief success comes from her marketing brilliance,[22] as he proposes that "one cannot fully grasp the Madonna phenomenon without analyzing her marketing and publicity strategies".[307] Kelley School of Business commented that "she is someone everyone can learn from, though the lessons run counter to conventional marketing wisdom of the 4Ps variet".[308]

Devoted case studies and terms[edit]

A variety of experts devoted classes and case studies to her name. Economist Robert M. Grant, praised her because the "intensely competitive" and "volatile world of entertainment".[309] In his study, professor of marketing Stephen Brown called her a "marketing genius".[216] Jamie Anderson and Martin Kupp, taught at London Business School that she "is a born entrepreneur".[233]

Other experts have created phrases denoting her influence for the community. Business professor Oren Harari coined the expression the "Madonna effect" inspired in her business tactics and changes while deems its use for both individuals and organizations.[304][310] Doctor Peter van Ham writing for NATO Review explained the "Madonna-curve", an expression used by some business analysts to describe the "adapting to new tasks whilst staying true to one's own principles". He further explained that "businesses use Madonna as a role model of self-reinvention".[311]

Longevity and enduring "success"[edit]

In an industry where some artists don't last longer than a packet of chewing gum, Madonna has built a career of success and longevity that is unparalleled.

—David Thomas of MTV Australia (2013).[312]

Background: Shortly after her musical debut, Madonna was considered a one-hit wonder by American music critics such as Robert Hilburn and Paul Grain (from Billboard), as they "predicted" a rapid decline.[313] In this journey, Madonna faced comparison with Cyndi Lauper, documented as the first singer that she was compared to, with Grain saying: "Lauper will be around for a long time; Madonna will be out of the business in six months".[313]

In her next years, Madonna's perpetual controversies led some arguing the end of her career, because she "gone too far". The early-1990s was a peak for these feelings, with a premier example when she published the book Sex, accompanied of the album Erotica and the NC-17 movie, Body of Evidence. This led media scholar David Tetzlaff, to suggest around this time: "Never before has a popular performer survived so much hype for so long and continued to attract the fascination of a broad public while staying completely contemporary".[314] Tetzlaff was aware of the cultural longevity of others performers as various as Elvis Presley, Liz Taylor or the Rolling Stones, but was based largely in nostalgia.[314]

Timeline: The term longevity attached on Madonna, is generally dated in the early 1990s before having a 10-years of career, and that definition was unusual for a musician under her conditions of that era. Contemporary articles described her as a "veteran" and having a career "equivalent to five lifetimes in rock-star years".[315][316] Meanwhile, outlets started largely discuss Madonna's longevity along her success, including Australian newspaper The Canberra Times in 1992,[317] with author Landrum going further: "Her success has made her the most visible show business personality of the era, and arguably of the century".[318] In 2022, Helen Brown from Financial Times noticed many of these views on Madonna, adding that "then as now, the average chart-life of a pop singer was two to six years, generally shorter for women than men".[319] However, Matthew Jacobs of HuffPost, also noticed these views but calling them as the start of "fatigue" on her.[285]

Analysis: New Zealand professor Roy Shuker, wrote that "the continued success of Madonna provides a fascinating case study of the nature of star appeal in popular music".[223] In 1999, Thales de Menezes from Brazilian newspaper Folha de S.Paulo, deemed her as a "rare case" of a lasting relationship with success.[320] Professor Miklitsch, concluded that she sardonically ask her critics in "Human Nature" about her longevity and controversies with the phrase: "Did I stay too long?".[321] Decades later, in 2016 at the Billboard Women in Music, singer told the audience: "I think the most controversial thing I have ever done is to stick around".[319]

Legacy: Her long-time enduring success and longevity have found an impact not only for her, but also on others. Professor Thomas Harrison, summed up that she "had a profound impact" on what artists needed to do to be successful in the 1980s and the decades after.[322] In 2010, Time editor Michelle Castillo convinced that "every pop star (of the past two or three decades) has Madonna to thank in some part for his or her success".[323] In a similar statement, professor Mary Cross stated that "new pop icons owe Madonna a debt of thanks".[138]

The attribution was larger to female artists. On the whole, Madonna ended embodying "female success in a male-dominated industry".[324] One supporter is author Stuart A. Kallen, describing that Madonna's success "opened doors for female musicians in the male-dominated world of rock and roll".[325] In another consideration, Sclafani added: Madonna's successive hit records "opened people's minds as to how successful a female artist could be".[125] In a general sense, Dutch academics added that female artists "are very often measured against the yardstick that Madonna has become".[326]

As she accumulated success in multiple decades, while some presaged the "ending" of her career due controversies, British sociologist David Gauntlett said the singer has provided a recipe for "longevity", which many artists, female and male, may try to emulate.[128] British sociologist Ellis Cashmore, also discussed this, saying that she both epitomized and helped usher in an age in which the epithets "shocking", "disgusting" or "filthy" didn't presage the end of a career.[39]

As a businesswoman[edit]

Once named "America's smartest businesswoman",[327] this treatment was then unusual in her era, as her business acumen and entrepreneurial talent were becoming legend when such bastions of male capitalism as Forbes named as such according to Landrum.[318] A contemporary view came from professor E. Ann Kaplan, who says the singer "has entered the public sphere as an entrepreneur earning a lot of money, something that is not considered natural for women".[328] Historically, Madonna became in one of the few female CEOs in the industry;[329] she co-funded her own entertainment company Maverick, becoming in one of the first female artist to have a "real label" (Maverick Records), and one of the few women to run her own entertainment company.[330] She set up a number of other companies and firms in her career.[331][332]