Islamic Golden Age: Difference between revisions

→Scientific Revolution: elaborated on Mathematics |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 163: | Line 163: | ||

Several Muslim astronomers also considered the possibility of the [[Earth's rotation]] on its axis and perhaps a [[heliocentric]] solar system.<ref name=Ajram>K. Ajram (1992). ''Miracle of Islamic Science'', Appendix B. Knowledge House Publishers. ISBN 0911119434.</ref><ref>S. H. Nasr (1964), ''An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines,'' (Cambridge: Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press), pp. 135-6</ref> It is known that the [[Copernican heliocentrism|Copernican heliocentric model]] in [[Nicolaus Copernicus]]' ''[[De revolutionibus]]'' was adapted from the [[geocentric model]] of [[Ibn al-Shatir]] and the [[Maragheh observatory|Maragheh school]] in a [[Heliocentrism|heliocentric]] context.<ref>[[George Saliba]] (1999). [http://www.columbia.edu/~gas1/project/visions/case1/sci.1.html Whose Science is Arabic Science in Renaissance Europe?] [[Columbia University]]. The relationship between Copernicus and the [[Maragheh observatory|Maragheh school]] is detailed in Toby Huff, ''The Rise of Early Modern Science'', Cambridge University Press.</ref> |

Several Muslim astronomers also considered the possibility of the [[Earth's rotation]] on its axis and perhaps a [[heliocentric]] solar system.<ref name=Ajram>K. Ajram (1992). ''Miracle of Islamic Science'', Appendix B. Knowledge House Publishers. ISBN 0911119434.</ref><ref>S. H. Nasr (1964), ''An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines,'' (Cambridge: Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press), pp. 135-6</ref> It is known that the [[Copernican heliocentrism|Copernican heliocentric model]] in [[Nicolaus Copernicus]]' ''[[De revolutionibus]]'' was adapted from the [[geocentric model]] of [[Ibn al-Shatir]] and the [[Maragheh observatory|Maragheh school]] in a [[Heliocentrism|heliocentric]] context.<ref>[[George Saliba]] (1999). [http://www.columbia.edu/~gas1/project/visions/case1/sci.1.html Whose Science is Arabic Science in Renaissance Europe?] [[Columbia University]]. The relationship between Copernicus and the [[Maragheh observatory|Maragheh school]] is detailed in Toby Huff, ''The Rise of Early Modern Science'', Cambridge University Press.</ref> |

||

=== |

===Chemistry=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

The 9th century [[chemist]], [[Geber]] (Jabir ibn Hayyan), is considered the father of [[chemistry]],<ref>John Warren (2005). "War and the Cultural Heritage of Iraq: a sadly mismanaged affair", ''Third World Quarterly'', Volume 26, Issue 4 & 5, p. 815-830.</ref><ref>Dr. A. Zahoor (1997). [http://www.unhas.ac.id/~rhiza/saintis/haiyan.html JABIR IBN HAIYAN (Geber)]. [[University of Indonesia]].</ref> for introducing the first [[experiment]]al [[scientific method]] for chemistry, as well as the [[alembic]], [[still]], [[retort]], pure [[distillation]], [[liquefaction]], [[crystallisation]], [[purification]], [[oxidisation]], [[evaporation]], and [[filtration]].<ref name=Vallely/> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Al-Kindi]] was the first to debunk the theory of the [[Philosopher's stone|transmutation of metals]],<ref>Felix Klein-Frank (2001), "Al-Kindi", in [[Oliver Leaman]] & [[Hossein Nasr]], ''History of Islamic Philosophy'', p. 174. London: [[Routledge]].</ref> followed by [[Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī]]<ref>Michael E. Marmura (1965). "''An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines. Conceptions of Nature and Methods Used for Its Study by the Ikhwan Al-Safa'an, Al-Biruni, and Ibn Sina'' by Seyyed [[Hossein Nasr]]", ''Speculum'' '''40''' (4), p. 744-746.</ref> and [[Avicenna]].<ref>[[Robert Briffault]] (1938). ''The Making of Humanity'', p. 196-197.</ref> [[Alexander von Humboldt]] and [[Will Durant]] regarded the Muslim chemists as the founders of chemistry.<ref>Dr. Kasem Ajram (1992). ''Miracle of Islamic Science'', Appendix B. Knowledge House Publishers. ISBN 0911119434.</ref><ref>[[Will Durant]] (1980). ''The Age of Faith ([[The Story of Civilization]], Volume 4)'', p. 162-186. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671012002.</ref> |

|||

===Experimental physics=== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

The study of [[experimental physics]] began with [[Ibn al-Haytham]],<ref>Rüdiger Thiele (2005). "In Memoriam: Matthias Schramm", ''Arabic Sciences and Philosophy'' '''15''', p. 329–331. [[Cambridge University Press]].</ref> the father of [[optics]], who pioneered the [[experiment]]al [[scientific method]] and used it drastically transform the understanding of [[light]] and [[vision]] in his ''[[Book of Optics]]'', which has been ranked alongside [[Isaac Newton]]'s ''[[Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica]]'' as one of the most influential books in the [[history of physics]].<ref> H. Salih, M. Al-Amri, M. El Gomati (2005). "The Miracle of Light", ''A World of Science'' '''3''' (3). [[UNESCO]].</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | The experimental scientific method was soon introduced into [[mechanics]] by [[al-Biruni]],<ref>Mariam Rozhanskaya and I. S. Levinova (1996), "Statics", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., ''[[Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science]]'', Vol. 2, p. 614-642 [642]. [[Routledge]], London and New York.</ref> and early precursors to [[Newton's laws of motion]] were discovered by several Muslim scientists. The law of [[inertia]], known as Newton's first law of motion, and the concept of [[momentum]], part of Newton's second law of motion, were discovered by [[Ibn al-Haytham]] (Alhacen)<ref>[[Abdus Salam]] (1984), "Islam and Science". In C. H. Lai (1987), ''Ideals and Realities: Selected Essays of Abdus Salam'', 2nd ed., World Scientific, Singapore, p. 179-213.</ref><ref>Seyyed [[Hossein Nasr]], "The achievements of Ibn Sina in the field of science and his contributions to its philosophy", ''Islam & Science'', December 2003.</ref> and [[Avicenna]].<ref name=Espinoza>Fernando Espinoza (2005). "An analysis of the historical development of ideas about motion and its implications for teaching", ''Physics Education'' '''40''' (2), p. 141.</ref><ref>Seyyed [[Hossein Nasr]], "Islamic Conception Of Intellectual Life", in Philip P. Wiener (ed.), ''Dictionary of the History of Ideas'', Vol. 2, p. 65, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1973-1974.</ref> The proportionality between [[force]] and [[acceleration]], foreshadowing Newton's second law of motion, was discovered by [[Hibat Allah Abu'l-Barakat al-Baghdaadi]],<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |

||

| last = [[Shlomo Pines]] |

| last = [[Shlomo Pines]] |

||

| title = Abu'l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī, Hibat Allah |

| title = Abu'l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī, Hibat Allah |

||

| Line 179: | Line 188: | ||

<br>([[cf.]] Abel B. Franco (October 2003). "Avempace, Projectile Motion, and Impetus Theory", ''Journal of the History of Ideas'' '''64''' (4), p. 521-546 [528].)</ref> while the concept of [[Reaction (physics)|reaction]], foreshadowing Newton's third law of motion, was discovered by [[Ibn Bajjah]] (Avempace).<ref>[[Shlomo Pines]] (1964), "La dynamique d’Ibn Bajja", in ''Mélanges Alexandre Koyré'', I, 442-468 [462, 468], Paris. |

<br>([[cf.]] Abel B. Franco (October 2003). "Avempace, Projectile Motion, and Impetus Theory", ''Journal of the History of Ideas'' '''64''' (4), p. 521-546 [528].)</ref> while the concept of [[Reaction (physics)|reaction]], foreshadowing Newton's third law of motion, was discovered by [[Ibn Bajjah]] (Avempace).<ref>[[Shlomo Pines]] (1964), "La dynamique d’Ibn Bajja", in ''Mélanges Alexandre Koyré'', I, 442-468 [462, 468], Paris. |

||

<br>([[cf.]] Abel B. Franco (October 2003). "Avempace, Projectile Motion, and Impetus Theory", ''Journal of the History of Ideas'' '''64''' (4), p. 521-546 [543].)</ref> Theories foreshadowing [[Newton's law of universal gravitation]] were developed by [[Ja'far Muhammad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir]],<ref>[[Robert Briffault]] (1938). ''The Making of Humanity'', p. 191.</ref> [[Ibn al-Haytham]],<ref>Nader El-Bizri (2006), "Ibn al-Haytham or Alhazen", in Josef W. Meri (2006), ''Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopaedia'', Vol. II, p. 343-345, [[Routledge]], New York, London.</ref> and [[al-Khazini]].<ref>Mariam Rozhanskaya and I. S. Levinova (1996), "Statics", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., ''Encyclopaedia of the History of Arabic Science'', Vol. 2, p. 622. London and New York: Routledge.</ref> It is known that [[Galileo Galilei]]'s mathematical treatment of [[acceleration]] and his concept of [[Inertia#Early understanding of motion|impetus]]<ref>Galileo Galilei, ''Two New Sciences'', trans. Stillman Drake, (Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Pr., 1974), pp 217, 225, 296-7.</ref> grew out of earlier medieval Muslim analyses of [[Motion (physics)|motion]], especially those of [[Avicenna]]<ref name=Espinoza/> and [[Ibn Bajjah]].<ref>Ernest A. Moody (1951). "Galileo and Avempace: The Dynamics of the Leaning Tower Experiment (I)", ''Journal of the History of Ideas'' '''12''' (2), p. 163-193.</ref> |

<br>([[cf.]] Abel B. Franco (October 2003). "Avempace, Projectile Motion, and Impetus Theory", ''Journal of the History of Ideas'' '''64''' (4), p. 521-546 [543].)</ref> Theories foreshadowing [[Newton's law of universal gravitation]] were developed by [[Ja'far Muhammad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir]],<ref>[[Robert Briffault]] (1938). ''The Making of Humanity'', p. 191.</ref> [[Ibn al-Haytham]],<ref>Nader El-Bizri (2006), "Ibn al-Haytham or Alhazen", in Josef W. Meri (2006), ''Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopaedia'', Vol. II, p. 343-345, [[Routledge]], New York, London.</ref> and [[al-Khazini]].<ref>Mariam Rozhanskaya and I. S. Levinova (1996), "Statics", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., ''Encyclopaedia of the History of Arabic Science'', Vol. 2, p. 622. London and New York: Routledge.</ref> It is known that [[Galileo Galilei]]'s mathematical treatment of [[acceleration]] and his concept of [[Inertia#Early understanding of motion|impetus]]<ref>Galileo Galilei, ''Two New Sciences'', trans. Stillman Drake, (Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Pr., 1974), pp 217, 225, 296-7.</ref> grew out of earlier medieval Muslim analyses of [[Motion (physics)|motion]], especially those of [[Avicenna]]<ref name=Espinoza/> and [[Ibn Bajjah]].<ref>Ernest A. Moody (1951). "Galileo and Avempace: The Dynamics of the Leaning Tower Experiment (I)", ''Journal of the History of Ideas'' '''12''' (2), p. 163-193.</ref> |

||

===Mathematics=== |

|||

{{main|Islamic mathematics}} |

|||

| ⚫ | Among the achievements of Muslim mathematicians during this period include the development of [[algebra]] and [[algorithm]]s (see [[Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī]]), the invention of [[spherical trigonometry]],<ref>{{cite book |last=Syed |first=M. H. |authorlink= |coauthors= |editor= |others= |title=Islam and Science |origdate= |origyear= |origmonth= |url= |format= |accessdate= |accessyear= |accessmonth= |edition= |series= |date= |year=2005 |month= |publisher=Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. |location= |language= |isbn=8-1261-1345-6 |oclc= |doi= |id= |pages=71 |chapter= |chapterurl= |quote= }}</ref> the addition of the [[decimal point]] notation to the [[Arabic numerals]], the introduction of [[Mathematical proof|proof]] by [[mathematical induction]], and numerous other advances in [[arithmetic]], [[calculus]], [[geometry]], [[number theory]], and [[trigonometry]]. |

||

===Medicine=== |

===Medicine=== |

||

| Line 202: | Line 216: | ||

===Other sciences=== |

===Other sciences=== |

||

{{main|Islamic science}} |

{{main|Islamic science}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Among the achievements of Muslim |

||

Many other advances were made by Muslim scientists in [[biology]] ([[anatomy]], [[botany]], [[evolution]], [[physiology]] and [[zoology]]) |

Many other advances were made by Muslim scientists in [[biology]] ([[anatomy]], [[botany]], [[evolution]], [[physiology]] and [[zoology]]), the [[earth science]]s ([[anthropology]], [[cartography]], [[geodesy]], [[geography]] and [[geology]]), [[psychology]] ([[experimental psychology]], [[psychiatry]], [[psychophysics]] and [[psychotherapy]]), and the [[social sciences]] ([[demography]], [[economics]], [[Early Muslim sociology|sociology]], [[Historiography of early Islam|history and historiography]]). |

||

Some of the most famous scientists from the Islamic world include [[Geber]] ([[polymath]], father of [[chemistry]]), [[Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī]] (father of [[algebra]] and [[algorithm]]s), [[al-Farabi]] (polymath), [[Abu al-Qasim]] (father of modern [[surgery]]),<ref>A. Martin-Araguz, C. Bustamante-Martinez, Ajo V. Fernandez-Armayor, J. M. Moreno-Martinez (2002). "Neuroscience in al-Andalus and its influence on medieval scholastic medicine", ''Revista de neurología'' '''34''' (9), p. 877-892.</ref> [[Ibn al-Haytham]] (polymath, father of [[optics]], founder of [[experimental psychology]], pioneer of [[scientific method]], "first scientist")<ref name=Khaleefa/>, [[Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī]] (polymath, father of [[Indology]]<ref>Zafarul-Islam Khan, [http://milligazette.com/Archives/15-1-2000/Art5.htm At The Threshhold Of A New Millennium – II], ''The Milli Gazette''.</ref> and [[geodesy]], "first [[anthropologist]]"),<ref>Akbar S. Ahmed (1984). "Al-Beruni: The First Anthropologist", ''RAIN'' '''60''', p. 9-10.</ref> [[Avicenna]] (polymath, father of [[momentum]]<ref>Seyyed Hossein Nasr, "Islamic Conception Of Intellectual Life", in Philip P. Wiener (ed.), ''Dictionary of the History of Ideas'', Vol. 2, p. 65, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1973-1974.</ref> and modern [[medicine]]),<ref>Cas Lek Cesk (1980). "The father of medicine, Avicenna, in our science and culture: Abu Ali ibn Sina (980-1037)", ''Becka J.'' '''119''' (1), p. 17-23.</ref> [[Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī]] (polymath), and [[Ibn Khaldun]] (father of [[demography]],<ref name=Mowlana>H. Mowlana (2001). "Information in the Arab World", ''Cooperation South Journal'' '''1'''.</ref> [[cultural history]],<ref>Mohamad Abdalla (Summer 2007). "Ibn Khaldun on the Fate of Islamic Science after the 11th Century", ''Islam & Science'' '''5''' (1), p. 61-70.</ref> [[historiography]],<ref>Salahuddin Ahmed (1999). ''A Dictionary of Muslim Names''. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1850653569.</ref> the [[philosophy of history]], [[sociology]],<ref name=Akhtar>Dr. S. W. Akhtar (1997). "The Islamic Concept of Knowledge", ''Al-Tawhid: A Quarterly Journal of Islamic Thought & Culture'' '''12''' (3).</ref> and the [[social sciences]]),<ref>Akbar Ahmed (2002). "Ibn Khaldun’s Understanding of Civilizations and the Dilemmas of Islam and the West Today", ''Middle East Journal'' '''56''' (1), p. 25.</ref> among many others. |

Some of the most famous scientists from the Islamic world include [[Geber]] ([[polymath]], father of [[chemistry]]), [[Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī]] (father of [[algebra]] and [[algorithm]]s), [[al-Farabi]] (polymath), [[Abu al-Qasim]] (father of modern [[surgery]]),<ref>A. Martin-Araguz, C. Bustamante-Martinez, Ajo V. Fernandez-Armayor, J. M. Moreno-Martinez (2002). "Neuroscience in al-Andalus and its influence on medieval scholastic medicine", ''Revista de neurología'' '''34''' (9), p. 877-892.</ref> [[Ibn al-Haytham]] (polymath, father of [[optics]], founder of [[experimental psychology]], pioneer of [[scientific method]], "first scientist")<ref name=Khaleefa/>, [[Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī]] (polymath, father of [[Indology]]<ref>Zafarul-Islam Khan, [http://milligazette.com/Archives/15-1-2000/Art5.htm At The Threshhold Of A New Millennium – II], ''The Milli Gazette''.</ref> and [[geodesy]], "first [[anthropologist]]"),<ref>Akbar S. Ahmed (1984). "Al-Beruni: The First Anthropologist", ''RAIN'' '''60''', p. 9-10.</ref> [[Avicenna]] (polymath, father of [[momentum]]<ref>Seyyed Hossein Nasr, "Islamic Conception Of Intellectual Life", in Philip P. Wiener (ed.), ''Dictionary of the History of Ideas'', Vol. 2, p. 65, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1973-1974.</ref> and modern [[medicine]]),<ref>Cas Lek Cesk (1980). "The father of medicine, Avicenna, in our science and culture: Abu Ali ibn Sina (980-1037)", ''Becka J.'' '''119''' (1), p. 17-23.</ref> [[Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī]] (polymath), and [[Ibn Khaldun]] (father of [[demography]],<ref name=Mowlana>H. Mowlana (2001). "Information in the Arab World", ''Cooperation South Journal'' '''1'''.</ref> [[cultural history]],<ref>Mohamad Abdalla (Summer 2007). "Ibn Khaldun on the Fate of Islamic Science after the 11th Century", ''Islam & Science'' '''5''' (1), p. 61-70.</ref> [[historiography]],<ref>Salahuddin Ahmed (1999). ''A Dictionary of Muslim Names''. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1850653569.</ref> the [[philosophy of history]], [[sociology]],<ref name=Akhtar>Dr. S. W. Akhtar (1997). "The Islamic Concept of Knowledge", ''Al-Tawhid: A Quarterly Journal of Islamic Thought & Culture'' '''12''' (3).</ref> and the [[social sciences]]),<ref>Akbar Ahmed (2002). "Ibn Khaldun’s Understanding of Civilizations and the Dilemmas of Islam and the West Today", ''Middle East Journal'' '''56''' (1), p. 25.</ref> among many others. |

||

Revision as of 03:55, 21 October 2007

During the Islamic Golden Age, usually dated from the 8th century to the 13th century,[1] engineers, scholars and traders of the Islamic world contributed enormously to the arts, economics, industry, literature, navigation, philosophy, sciences, and technology, both by preserving and building upon earlier traditions and by adding many inventions and innovations of their own.[2] Muslim philosophers and poets, artists and scientists, and princes and laborers, created a unique culture that has influenced societies on every continent.[2]

Foundations

The Islamic Golden Age was inaugurated by the ascension of the Abbasid Caliphate and the transfer of the capital from Damascus to Baghdad.[3] The Abbassids were influenced by the Qur'anic injunctions and hadith such as "the ink of scientists is equal to the blood of martyrs" stressing the value of knowledge.[3] During this period the Muslim world became the unrivaled intellectual center for science, philosophy, medicine and education as the Abbasids championed the cause of knowledge and established a "House of Wisdom" in Baghdad; where both Muslim and non-Muslim scholars sought to translate and gather all the world's knowledge into Arabic.[3] Many classic works of antiquity that would otherwise have been lost were translated into Arabic and later in turn translated into Turkish, Persian, Hebrew and Latin.[3] During this period the Muslim world was a cauldron of cultures which collected, synthesized and advanced the works collected from the Chinese, Persian, Egyptian, North African, Greek, Spanish, Sicilian and Byzantine civilizations.[3] Rival Muslim dynasties such as the Fatimids of Egypt, the Umayyads of al-Andalus were also major intellectual centers with cities such as Cairo and Córdoba rivaling Baghdad.[3] Religious freedom, though limited, helped create cross-cultural networks by attracting Muslim, Christian and Jewish intellectuals and thereby helped spawn the greatest period of philosophical creativity in the Middle Ages during the 12th and 13th centuries.[3]

A major innovation of this period was paper - originally a secret tightly guarded by the Chinese.[4] The art of papermaking was obtained from prisoners taken at the Battle of Talas (751), resulting in paper mills being built in Samarkand and Baghdad.[4] The Arabs improved upon the Chinese techniques of using mulberry bark by using starch to account for the Muslim preference for pens vs. the Chinese for brushes.[4] By AD 900 there were hundreds of shops employing scribes and binders for books in Baghdad and even public libraries began to become established,[4] including the first lending libraries. From here paper-making spread west to Fez and then to al-Andalus and from there to Europe in the 13th century.[4]

By the 10th century, Cordoba had 700 mosques, 60,000 palaces, and 70 libraries, the largest of which had 600,000 books, while as many as 60,000 treatises, poems, polemics and compilations were published each year in al-Andalus.[5] The library of Cairo had more than 100,000 books, while the library of Tripoli is said to have had as many as three million books. The number of important and original Arabic works on science that have survived is much larger than the combined total of Greek and Latin works on science.[6]

Much of this learning and development can be linked to geography. Even prior to Islam's presence, the city of Mecca served as a center of trade in Arabia and the Islamic prophet Muhammad was a merchant. The tradition of the pilgrimage to Mecca became a center for exchanging ideas and goods. The influence held by Muslim merchants over African-Arabian and Arabian-Asian trade routes was tremendous. As a result, Islamic civilization grew and expanded on the basis of its merchant economy, in contrast to their Christian, Indian and Chinese peers who built societies from an agricultural landholding nobility. Merchants brought goods and their faith to China, India (the Indian subcontinent now has over 450 million followers), Southeast Asia (which now has over 230 million followers), and the kingdoms of Western Africa and returned with new inventions. Merchants used their wealth to invest in textiles and plantations.

Aside from traders, Sufi missionaries also played a large role in the spread of Islam, by bringing their message to various regions around the world. The principal locations included: Persia, Ancient Mesopotamia, Central Asia and North Africa. Although, the mystics also had a significant influence in parts of Eastern Africa, Ancient Anatolia (Turkey), South Asia, East Asia and Southeast Asia. [7][8]

Ò===Age of discovery===

The earliest forms of globalization began emerging during the Arab Empire and the Islamic Golden Age, when the knowledge, trade and economies from many previously isolated regions and civilizations began integrating due tcalos waz here look for my last mameo contacts with Muslim explorers, sailors, scholars, traders, and travelers. Some have called this period the "Pax Islamica" or "Afro-Asiatic age of discovery", in reference to the Muslim Southwest Asian and North African traders and explorers who travelled most of the Old World, and established an early global economy[9] across most of Asia and Africa and much of Europe, with their trade networks extending from the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea in the west to the Indian Ocean and China Sea in the east.[10] This helped establish the Arab Empire (including the Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid and Fatimid caliphates) as the world's leading extensive economic power throughout the 7th-13th centuries.[11]

Apart from the Nile, Tigris and Euphrates, navigable rivers were uncommon, so transport by sea was very important. Navigational sciences were highly developed making use of a magnetic compass and a rudimentary sextant known as a kamal, used for celestial navigation and for measuring the altitudes and latitudes of the stars. When combined with detailed maps of the period, sailors were able to sail across oceans rather than skirt along the coast. Muslim sailors were also responsible for introducing the lateen sails and large three-masted merchant vessels to the Mediterranean. The origins of the caravel ship, used for long distance travel by the Spanish and Portuguese since the 15th century, also date back to the qarib used by Andalusian explorers by the 13th century.[12]

Ibn Battuta (1304-1368) was a traveler and explorer, whose account documents his travels and excursions over a period of almost thirty years, covering some 73,000 miles (117,000 km). These journeys covered most of the known Old World, extending from North Africa, West Africa, Southern Europe and Eastern Europe in the west, to the Middle East, Indian subcontinent, Central Asia, Southeast Asia and China in the east, a distance readily surpassing that of his predecessors and his near-contemporary Marco Polo.

Several contemporary medieval Arabic reports suggest that Muslim explorers from Islamic Spain and Northwest Africa may have travelled in expeditions across the Atlantic Ocean, possibly even to the Americas, between the 9th and 14th centuries. Ali al-Masudi (896-956) reported that the navigator Khashkhash Ibn Saeed Ibn Aswad, from Cordoba, Islamic Spain, sailed from Delba (Palos) in 889, crossed the Atlantic, reached an unknown land, and returned with fabulous treasures.[13][14][15] Another Muslim navigator, Ibn Farrukh, from Granada, sailed into the Atlantic on February 999, landed in Gando (Canary islands) visiting King Guanariga, and continued westward where he eventually saw and named two islands, Capraria and Pluitana. He arrived back in Spain in May 999.[14][16] Other theories suggest that explorers from the Muslim West African Mali Empire may have reached the Americas, or possibly the Hui Chinese Muslim explorer Zheng He according to the 1421 hypothesis. When Christopher Columbus made his first voyage to the Americas in 1492, he was accompanied by a number of Muslim sailors (Andalusian Moors), who travelled with him to the New World.[17]

Agricultural Revolution

The Islamic Golden Age witnessed a fundamental transformation in agriculture known as the "Muslim Agricultural Revolution", "Arab Agricultural Revolution", or "Green Revolution".[18] Due to the global economy established by Muslim traders across the Old World, this enabled the diffusion of many plants and farming techniques between different parts of the Islamic world, as well as the adaptation of plants and techniques from beyond the Islamic world. Crops from Africa such as sorghum, crops from China such as citrus fruits, and numerous crops from India such as mangos, rice, and especially cotton and sugar cane, were distributed throughout Islamic lands which normally would not be able to grow these crops.[19] Some have referred to the diffusion of numerous crops during this period as the "Globalisation of Crops",[20] which, along with an increased mechanization of agriculture (see Industrial growth below), led to major changes in economy, population distribution, vegetation cover,[21] agricultural production and income, population levels, urban growth, the distribution of the labour force, linked industries, cooking and diet, clothing, and numerous other aspects of life in the Islamic world.[19]

During the Muslim Agricultural Revolution, sugar production was refined and transformed into a large-scale industry by the Arabs, who built the first sugar refineries and sugar plantations. The Arabs and Berbers diffused sugar throughout the Arab Empire from the 8th century.[22]

Muslims introduced cash cropping[23] and the modern crop rotation system where land was cropped four or more times in a two-year period. Winter crops were followed by summer ones, and in some cases there was in between. In areas where plants of shorter growing season were used, such as spinach and eggplants, the land could be cropped three or more times a year. In parts of Yemen, wheat yielded two harvests a year on the same land, as did rice in Iraq.[19] Muslims developed a scientific approach based on three major elements; sophisticated systems of crop rotation, highly developed irrigation techniques, and the introduction of a large variety of crops which were studied and catalogued according to the season, type of land and amount of water they require. Numerous encyclopaedias on farming and botany were produced, with highly accurate precision and details.[24] The earliest cookbooks on Arab cuisine were also written, such as the Kitab al-Tabikh (The Book of Dishes) of Ibn Sayyiir al-Warraq (10th century) and the Kitab al-Tabikh of Muhammad bin Hasan al-Baghdadi (1226).[25]

Many other agricultural innovations were introduced by Muslim farmers and engineers, such as new forms of land tenure, improvements in irrigation, a variety of sophisticated irrigation methods,[26] the introduction of fertilizers and widespread artificial irrigation systems, the development of gravity-flow irrigation systems from rivers and springs,[18] the first uses of noria and chain pumps for irrigation purposes,[27] the establishment of the sugarcane industry in the Mediterranean and experimentation in sugar cultivation,[28] numerous advances in industrial milling and water-raising machines (see Industrial growth below), and many other improvements and innovations.

The Caliphate understood that real incentives were needed to increase productivity and wealth, thus enhancing tax revenues, hence they introduced a social transformation through the changed ownership of land,[27] where any individual of any gender[29] or any ethnic or religious background had the right to buy, sell, mortgage and inherit land for farming or any other purposes. They also introduced the signing of a contract for every major financial transaction concerning agriculture, industry, commerce, and employment. Copies of the contract was usually kept by both parties involved.[27]

The two types of economic systems that prompted agricultural development in the Islamic world were either politically-driven, by the conscious decisions of the central authority to develop under-exploited lands; or market-driven, involving the spread of advice, education, and free seeds, and the introduction of high value crops or animals to areas where they were previously unknown. These led to increased subsistence, a high level of economic security that ensured wealth for all citizens, and a higher quality of life due to the introduction of artichokes, spinach, aubergines, carrots, sugar cane, and various exotic plants; vegetables being available all year round without the need to dry them for winter; citrus and olive plantations becoming a common sight, market gardens and orchards springing up in every Muslim city; intense cropping and the technique of intensive irrigation agriculture with land fertility replacement; a major increase in animal husbandry; higher quality of wool and other clothing materials; and the introduction of selective breeding of animals from different parts of the Old World resulting in improved horse stocks and the best load-carrying camels.[27]

Many dams, acequia and qanat water supply systems and "Tribunal of Waters" irrigation systems were built during the Islamic Golden Age and are still in use today in the Islamic world and in formerly Islamic regions of Europe such as Sicily and the Iberian Peninsula, particularly in the Andalusia, Aragon and Valencia provinces of Spain. The Arabic systems of irrigation and water distribution were later adopted in the Canary Islands and Americas due to the Spanish and are still used in places like Texas, Mexico, Peru, and Chile.[22]

Botany

- Main article: Islamic science - Botany

Capitalist market economy

The origins of capitalism and free markets can be traced back to the Caliphate,[30] where the first market economy and earliest forms of merchant capitalism took root between the 8th-12th centuries, which some refer to as "Islamic capitalism".[31] A vigorous monetary economy was created on the basis of the expanding levels of circulation of a stable high-value currency (the dinar) and the integration of monetary areas that were previously independent. Innovative new business techniques and forms of business organisation were introduced by economists, merchants and traders during this time. Such innovations included the earliest trading companies, big businesses, contracts, bills of exchange, long-distance international trade, the first forms of partnership (mufawada) such as limited partnerships (mudaraba), and the earliest forms of credit, debt, profit, loss, capital (al-mal), capital accumulation (nama al-mal),[23] circulating capital, capital expenditure, revenue, cheques, promissory notes,[32] trusts (waqf), startup companies,[33] savings accounts, transactional accounts, pawning, loaning, exchange rates, bankers, money changers, ledgers, deposits, assignments, and the double-entry bookkeeping system.[34] Organizational enterprises similar to corporations independant from the state also existed in the medieval Islamic world.[35][36] Many of these early capitalist concepts were adopted and further advanced in medieval Europe from the 13th century onwards.[23]

A market economy was established in the Islamic world on the basis of merchant capitalism. Capital formation was promoted by labour in medieval Islamic society, and financial capital was developed by a considerable number of owners of monetary funds and precious metals. Riba (usury) was prohibited by the Qur'an, but this did not hamper the development of capital in any way. The capitalists (sahib al-mal) were at the height of their power between the 9th-12th centuries, but their influence declined after the arrival of the ikta (landowners) and after production was monopolized by the state, both of which hampered the development of industrial capitalism in the Islamic world.[37]

During the 11th-13th centuries, the "Karimis", the earliest multinational corporation, enterprise and business group controlled by capitalistic entrepreneurs, came to dominate much of the Islamic world's economy.[38] The group was controlled by about fifty Muslim merchants labelled as "Karimis" who were of Yemeni, Egyptian and sometimes Indian origins.[39] Each Karimi merchant had considerable wealth, ranging from at least 100,000 dinars to as much as 10 million dinars. The group had considerable influence in most important eastern markets and sometimes in politics through its financing activities and through a variety of customers, including Emirs, Sultans, Viziers, foreign merchants, and common consumers. The Karimis dominated many of the trade routes across the Mediterranean Sea, Red Sea, and Indian Ocean, and as far as Francia in the north, China in the east, and sub-Saharan Africa in the south, where they obtained gold from gold mines. Innovations introduced by the Karimis include the use of agents, the financing of projects as a method of acquiring capital, and a banking institution for loans and deposits. Another important difference between the Karimis and other entrepreneurs before and during their time was that they were not tax collectors or landlords, but their capitalism was due entirely to trade and financial transactions.[40]

Commerce

Guilds were officially unrecognized by the medieval Islamic city, but trades were supervised by an official recognized by the city. Each trade developed its own identity, whose members would attend the same mosque, and serve together in the militia. Slaves were often employed on sugar plantations and salt mines, but more likely as domestic house servants or professional soldiers.

Technology and Industry of Islamic civilization was highly developed. Distillation techniques supported a flourishing perfume industry, while chemical ceramic glazes were developed constantly to compete with ceramics imported from China. A scientific approach to metallurgy made it easier to adopt and improve steel technologies from India and China. Primary exports included manufactured luxuries, such as wood carving, metal and glass, textiles, and ceramics.

The systems of contract relied upon by merchants was very effective. Merchants would buy and sell on commission, with money loaned to them by wealthy investors, or a joint investment of several merchants, who were often Muslim, Christian and Jewish. Recently, a collection of documents was found in an Egyptian synagogue shedding a very detailed and human light on the life of medieval Middle Eastern merchants. Business partnerships would be made for many commercial ventures, and bonds of kinship enabled trade networks to form over huge distances. Networks developed during this time enabled a world in which money could be promised by a bank in Baghdad and cashed in Spain, creating the cheque system of today. Each time items passed through the cities along this extraordinary network, the city imposed a tax, resulting in high prices once reaching the final destination. These innovations made by Muslims and Jews laid the foundations for the modern economic system.

Transport was simple yet highly effective. Each city had an area outside its gates where pack animals were assembled, found in the cities markets were large secure warehouses, while accommodations were provided for merchants in cities and along trade routes by a sort of medieval motel.

Economic thought

- Main article: Early Muslim sociology - Economic thought

Industrial growth

Muslim engineers in the Islamic world were responsible for numerous innovative industrial uses of hydropower, the first industrial uses of tidal power, wind power, steam power, and fossil fuels such as petroleum, and the earliest large factory complexes (tiraz in Arabic).[41] The industrial uses of watermills in the Islamic world date back to the 7th century, while horizontal-wheeled and vertical-wheeled water mills were both in widespread use since at least the 9th century. A variety of industrial mills were first invented in the Islamic world, including fulling mills, gristmills, hullers, paper mills, sawmills, shipmills, stamp mills, steel mills, sugar mills, tide mills, and windmills. By the 11th century, every province throughout the Islamic world had these industrial mills in operation, from al-Andalus and North Africa to the Middle East and Central Asia.[42] Muslim engineers also invented crankshafts and water turbines, first employed gears in mills and water-raising machines, and pioneered the use of dams as a source of water power, used to provide additional power to watermills and water-raising machines.[22] Such advances made it possible for many industrial tasks that were previously driven by manual labour in ancient times to be mechanized and driven by machinery instead in the medieval Islamic world. The transfer of these technologies to medieval Europe later laid the foundations for the Industrial Revolution in 18th century Europe.[43]

Many industries were generated due to the Muslim Agricultural Revolution, including the earliest industries for agribusiness, astronomical instruments, ceramics, chemicals, distillation technologies, clocks, glass, mechanical hydropowered and wind powered machinery, matting, mosaics, pulp and paper, perfumery, petroleum, pharmaceuticals, rope-making, shipping, shipbuilding, silk, sugar, textiles, water, weapons, and the mining of minerals such as sulfur, ammonia, lead and iron. The first large factory complexes (tiraz) were built for many of these industries. Knowledge of these industries were later transmitted to medieval Europe, especially during the Latin translations of the 12th century, as well as before and after. For example, the first glass factories in Europe were founded in the 11th century by Egyptian craftsmen in Greece.[44] The agricultural and handicraft industries also experienced high levels of growth during this period.[10]

Muslim engineers pioneered two solutions to achieve the maximum output from a water mill. The first solution was to mount them to piers of bridges to take advantage of the increased flow. The second solution was the shipmill, a unique type of water mill powered by water wheels mounted on the sides of ships moored in midstream. This was first employed along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in 10th century Iraq, where large shipmills made of teak and iron could produce 10 tons of flour from corn every day for the granary in Baghdad.[45] Industrial water mills were also employed in the first large factory complexes built in al-Andalus between the 11th and 13th centuries. Fulling mills, paper mills, steel mills, and other mills, spread from Islamic Spain to Christian Spain by the 12th century.[46]

Windmills were first built in Sistan, Afghanistan, from the 7th century. These were verticle axle windmills, which had long vertical shafts with rectangle shaped blades.[47] The first windmill was built by the Rashidun caliph Umar (634-644).[48] Made of six to twelve sails covered in reed matting or cloth material, these windmills were used to grind corn and draw up water, and were used in the gristmilling and sugarcane industries.[45]

After paper was introduced into the Islamic world by Chinese prisoners following the Battle of Talas, Muslims made significant improvements to papermaking and built the first paper mills in Baghdad, Iraq, as early as 794. Papermaking was transformed from an art into a major industry as a result.[49] This allowed the manufacturing of paper in the Islamic world to be performed using water power rather than manual labour. The first fulling mills were later invented in the 10th century, followed by the first stamp mills and steel mills in the 11th century.[50]

The first gristmills were invented by Muslim engineers in the Islamic world, and were used for grinding corn and other seeds to produce meals, and many other industrial uses such as fulling cloth, husking rice, papermaking, pulping sugarcane, and crushing metalic ores before extraction. Gristmills in the Islamic world were often made from both watermills and windmills. In order to adapt water wheels for gristmilling purposes, cams were used for raising and releasing trip hammers to fall on a material.[45] The first water turbine, which had water wheels with curved blades onto which water flow was directed axially, was also first invented in the Islamic world, and was described in a 9th century Arabic text for use in a watermill.[45]

Noria and chain pump (saqiya) machines became more widespread during the Muslim Agricultural Revolution, when Muslim engineers made a number of improvements to the device.[18] These include the first uses of noria and chain pumps for irrigation purposes,[27] and the invention of the flywheel mechanism, used to smooth out the delivery of power from a driving device to a driven machine, which was first invented by Ibn Bassal (fl. 1038-1075) of al-Andalus, who pioneered the use of the flywheel in the saqiya and noria.[51]

The chemical industry and petroleum industry were established in the 8th century, when the mineral acids (such as sulfuric acid) were first produced through dry distillation, and when the streets of Baghdad were paved with tar, derived from petroleum through destructive distillation. In the 9th century, oil fields were exploited in the area around modern Baku, Azerbaijan, to produce naphtha. These fields were described by Masudi in the 10th century, and by Marco Polo in the 13th century, who described the output of those oil wells as hundreds of shiploads.[52] Petroleum was distilled by al-Razi in the 9th century, producing chemicals such as kerosene in the alembic, which he used to invent kerosene lamps for use in the oil lamp industry.[53]

The first industrial use of steam power dates back to the perfumery industry established by Muslim chemists such as Geber, al-Razi, and Avicenna, who pioneered and perfected the extraction of fragrances and essential oils through steam distillation, introduced new raw ingredients, and developed cheap methods for the mass production of perfumery and incenses. Both the raw ingredients and distillation technology significantly influenced Western perfumery. Muslim traders had wide access to a variety of different spices, herbs, and other fragrance materials. In addition to trading them, many of these exotic materials were cultivated by the Muslims such that they could be successfully grown outside of their native climates. Two examples of this include jasmine, which is native to South Asia and Southeast Asia, and various citrus fruits native to East Asia. Both of these ingredients are still highly important in modern perfumery.

In 1206, al-Jazari invented a variety of machines for raising water, which were the most efficient in his time, as well as water wheels with cams on their axle used to operate automata. He invented the crankshaft and connecting rod, and employed them in a crank-connecting rod system for two of these water-raising machines. His invention of the crankshaft is considered the most important single mechanical invention after the wheel, as it transforms continuous rotary motion into a linear reciprocating motion, and is central to modern machinery such as the steam engine and the internal combustion engine.[54][55] Al-Jazari's most sophisticated water-raising machine featured the first suction pipes and suction pump, the first use of the double-action principle, the first reciprocating piston engine, the earliest valve operations, and the use of a water wheel and a system of gears. This invention is important to the development of modern machinery, including the steam engine, modern reciprocating pumps,[56] internal combustion engine,[57] artificial heart,[58] bicycle, bicycle pump, etc.[59]

In 1551, after the decline of the golden age, the Egyptian engineer Taqi al-Din invented the first practical steam turbine as a prime mover for rotating a spit. This was the first time steam power was used to operate a practical machine or appliance. A similar steam turbine later appeared in Europe a century later, which eventually led to the steam engine and Industrial Revolution in 18th century Europe.[60]

Labour

The labour force in the Caliphate were employed from diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds, while both men and women were involved in diverse occupations and economic activities.[61] Women were employed in a wide range of commercial activities and diverse occupations[62] in the primary sector (as farmers for example), secondary sector (as construction workers, dyers, spinners, etc.) and tertiary sector (as investors, doctors, nurses, presidents of guilds, brokers, peddlers, lenders, scholars, etc.).[63] Muslim women also had a monopoly over certain branches of the textile industry.[62]

The division of labour was diverse and had been evolving over the centuries. During the 8th-11th centuries, there were 63 unique occupations in the primary sector of economic activity (extractive), 697 unique occupations in the secondary sector (manufacturing), and 736 unique occupations in the tertiary sector (service). By the 12th century, the number of unique occupations in the primary sector and secondary sector decreased to 35 and 679 respectively, while the number of unique occupations in the tertiary sector increased to 1,175. These changes in the division of labour reflect the increased mechanization and use of machinery to replace manual labour and the increased standard of living and quality of life of most citizens in the Caliphate.[64]

An economic transition occurred during this period, due to the diversity of the service sector being far greater than any other previous or contemporary society, and the high degree of economic integration between the labour force and the economy. Islamic society also experienced a change in attitude towards manual labour. In previous civilizations such as ancient Greece and in contemporary civilizations such as early medieval Europe, intellectuals saw manual labour in a negative light and looked down on them with contempt. This resulted in technological stagnation as they did not see the need for machinery to replace manual labour. In the Islamic world, however, manual labour was seen in a far more positive light, as intellectuals such as the Brethren of Purity likened them to a participant in the act of creation, while Ibn Khaldun alluded to the benefits of manual labour to the progress of society.[62]

Technology

- Further information: Industrial growth and Timeline of science and technology in the Islamic world

A significant number of inventions and technological advances were made in the Muslim world, as well as adopting and improving technologies centuries before they were used in the West. For example, papermaking was adopted from China many centuries before it was known in the West.[65] Iron was a vital industry in Muslim lands and was given importance in the Qur'an.[66][67] The knowledge of gunpowder was also transmitted from China to Islamic countries, where Muslim chemists were the first to purify saltpeter to the weapons-grade purity for use in gunpowder, as potassium nitrate must be purified to be used effectively. This purification process was first described by Ibn Bakhtawayh in his Al-Muqaddimat in the early 11th century.[68][69] Gunpowder weapons were employed by Muslim armies against Christian armies during the Crusades and Byzantine-Ottoman wars.[70] Knowledge of chemical processes (alchemy and chemistry) and distillation (alcohol, kerosene and other chemical substances) also spread to Europe from the Muslim world. Numerous contributions were made in laboratory practices such as "refined techniques of distillation, the preparation of medicines, and the production of salts."[71] Advances were made in irrigation and farming, using technology such as the windmill. Crops such as almonds and citrus fruit were brought to Europe through al-Andalus, and sugar cultivation was gradually adopted by the Europeans.[72]

Fielding H. Garrison wrote in the History of Medicine:

"The Saracens themselves were the originators not only of algebra, chemistry, and geology, but of many of the so-called improvements or refinements of civilization, such as street lamps, window-panes, firework, stringed instruments, cultivated fruits, perfumes, spices, etc..."

A significant number of other inventions were also produced by medieval Muslim scientists and engineers, including inventors such as Abbas Ibn Firnas, Taqi al-Din, and especially al-Jazari, who is considered the "father of robotics"[54] and "father of modern day engineering".[73]

Some of the other inventions and discoveries from the Islamic Golden Age include the camera obscura, coffee, hang glider, hard soap, shampoo, pure distillation, liquefaction, crystallisation, purification, oxidisation, evaporation, filtration, distilled alcohol, uric acid, nitric acid, alembic, crankshaft, valve, reciprocating suction piston pump, mechanical clocks driven by water and weights, programmable humanoid robot, combination lock, quilting, pointed arch, scalpel, bone saw, forceps, surgical catgut, windmill, inoculation, smallpox vaccine, fountain pen, cryptanalysis, frequency analysis, three-course meal, stained glass and quartz glass, Persian carpet, modern cheque, celestial globe, explosive rockets and incendiary devices, torpedo, and royal pleasure gardens.[54]

Urbanization

As urbanization increased, Muslim cities grew unregulated, resulting in narrow winding city streets and neighborhoods separated by different ethnic backgrounds and religious affiliations. These qualities proved efficient for transporting goods to and from major commercial centers while preserving the privacy valued by Islamic family life. Suburbs lay just outside the walled city, from wealthy residential communities, to working class semi-slums. City garbage dumps were located far from the city, as were clearly defined cemeteries which were often homes for criminals. A place of prayer was found just near one of the main gates, for religious festivals and public executions. Similarly, Military Training grounds were found near a main gate.

While varying in appearance due to climate and prior local traditions, Islamic cities were almost always dominated by a merchant middle class. Some peoples' loyalty towards their neighborhood was very strong, reflecting ethnicity and religion, while a sense of citizenship was at times uncommon (but not in every case). The extended family provided the foundation for social programs, business deals, and negotiations with authorities. Part of this economic and social unit were often the tenants of a wealthy landlord.

State power normally focused on Dar al Imara, the governor's office in the citadel. These fortresses towered high above the city built on thousands of years of human settlement. The primary function of the city governor was to provide for defence and to maintain legal order. This system would be responsible for a mixture of autocracy and autonomy within the city. Each neighborhood, and many of the large tenement blocks, elected a representative to deal with urban authorities. These neighborhoods were also expected to organize their young men into a militia providing for protection of their own neighborhoods, and as aid to the professional armies defending the city as a whole.

The head of the family was given the position of authority in his household, although a qadi, or judge was able to negotiate and resolve differences in issues of disagreements within families and between them. The two senior representatives of municipal authority were the qadi and the muhtasib, who held the responsibilities of many issues, including quality of water, maintenance of city streets, containing outbreaks of disease, supervising the markets, and a prompt burial of the dead.

Another aspect of Islamic urban life was waqf, a religious charity directly dealing with the qadi and religious leaders. Through donations, the waqf owned many of the public baths and factories, using the revenue to fund education, and to provide irrigation for orchards outside the city. Following expansion, this system was introduced into Eastern Europe by Ottoman Turks.

While religious foundations of all faiths were tax exempt in the Muslim world, civilians paid their taxes to the urban authorities, soldiers to the superior officer, and landowners to the state treasury. Taxes were also levied on an unmarried man until he was wed. Instead of zakat, the mandatory charity required of Muslims, non-Muslims were required to pay the jizya, a discriminatory religious tax, imposed on Christians and Jews. During the Muslim Conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries conquered populations were given the three choices of either converting to Islam, paying the jizya, or dying by the sword.

Animals brought to the city for slaughter were restricted to areas outside the city, as were any other industries seen as unclean. The more valuable a good was, the closer its market was to the center of town. Because of this, booksellers and goldsmiths clustered around the main mosque at the heart of the city.

Muslim cities also had advanced domestic water systems with sewers, public baths, drinking fountains, piped drinking water supplies,[74] and widespread private and public toilet and bathing facilities.[75]

Scientific Revolution

A number of modern scholars, notably Robert Briffault, Will Durant, Fielding H. Garrison, Alexander von Humboldt, Muhammad Iqbal, and Hossein Nasr, consider modern science to have begun from Muslim scientists, who were pioneers of the scientific method and introduced a modern empirical, experimental and quantitative approach to scientific inquiry. Some have referred to their achievements as a "Muslim scientific revolution".[76][77][78][79]

Scientific method

- Further information: Islamic science - Scientific method

The modern scientific method was first developed in the Muslim world, where significant progress in methodology was made, especially in the works of Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) in the 11th century, who was the pioneer of experimental physics.[80] The most important development of the scientific method was the use of experimentation and quantification to distinguish between competing scientific theories set within a generally empirical orientation. Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) wrote the Book of Optics, and he is known as the father of optics for empirically proving that vision occurred because of light rays entering the eye, as well as for inventing the camera obscura to demonstrate the physical nature of light rays.[81][82] Ibn al-Haytham has also been described as the "first scientist" for his introduction of the scientific method,[83] and some also consider him the founder of psychophysics and experimental psychology,[84] for his pioneering work on the psychology of visual perception.[85][86]

Astronomy

Advances in astronomy included the construction of the first observatory in Baghdad during the reign of Caliph Al-Ma'mun,[87] the first elaborate experiments related to astronomical phenomena by Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī, the collection and correction of previous astronomical data, resolving significant problems in the Ptolemaic model, perfected forms of the astrolabe,[88] the invention of numerous other astronomical instruments, and the beginning of astrophysics and celestial mechanics after Ja'far Muhammad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir discovered that the heavenly bodies and celestial spheres were subject to the same laws of physics as Earth.[89] Several Muslim astronomers also considered the possibility of the Earth's rotation on its axis and perhaps a heliocentric solar system.[52][90] It is known that the Copernican heliocentric model in Nicolaus Copernicus' De revolutionibus was adapted from the geocentric model of Ibn al-Shatir and the Maragheh school in a heliocentric context.[91]

Chemistry

The 9th century chemist, Geber (Jabir ibn Hayyan), is considered the father of chemistry,[92][93] for introducing the first experimental scientific method for chemistry, as well as the alembic, still, retort, pure distillation, liquefaction, crystallisation, purification, oxidisation, evaporation, and filtration.[54]

Al-Kindi was the first to debunk the theory of the transmutation of metals,[94] followed by Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī[95] and Avicenna.[96] Alexander von Humboldt and Will Durant regarded the Muslim chemists as the founders of chemistry.[97][98]

Experimental physics

- Further information: Islamic science: Optics and Islamic science: Mechanics

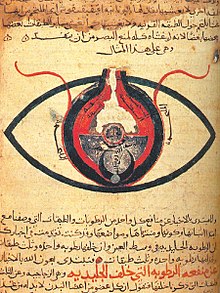

The study of experimental physics began with Ibn al-Haytham,[99] the father of optics, who pioneered the experimental scientific method and used it drastically transform the understanding of light and vision in his Book of Optics, which has been ranked alongside Isaac Newton's Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica as one of the most influential books in the history of physics.[100]

The experimental scientific method was soon introduced into mechanics by al-Biruni,[101] and early precursors to Newton's laws of motion were discovered by several Muslim scientists. The law of inertia, known as Newton's first law of motion, and the concept of momentum, part of Newton's second law of motion, were discovered by Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen)[102][103] and Avicenna.[104][105] The proportionality between force and acceleration, foreshadowing Newton's second law of motion, was discovered by Hibat Allah Abu'l-Barakat al-Baghdaadi,[106] while the concept of reaction, foreshadowing Newton's third law of motion, was discovered by Ibn Bajjah (Avempace).[107] Theories foreshadowing Newton's law of universal gravitation were developed by Ja'far Muhammad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir,[108] Ibn al-Haytham,[109] and al-Khazini.[110] It is known that Galileo Galilei's mathematical treatment of acceleration and his concept of impetus[111] grew out of earlier medieval Muslim analyses of motion, especially those of Avicenna[104] and Ibn Bajjah.[112]

Mathematics

Among the achievements of Muslim mathematicians during this period include the development of algebra and algorithms (see Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī), the invention of spherical trigonometry,[113] the addition of the decimal point notation to the Arabic numerals, the introduction of proof by mathematical induction, and numerous other advances in arithmetic, calculus, geometry, number theory, and trigonometry.

Medicine

Muslim physicians made many significant advances and contributions to medicine, including anatomy, ophthalmology, pathology, the pharmaceutical sciences (including pharmacy and pharmacology), physiology, and surgery, and they set up some of the earliest dedicated hospitals (including the first psychiatric hospitals), which later spread to Europe during the Crusades, inspired by the hospitals in the Middle East.[114]

The Comprehensive Book of Medicine written by Al-Razi (Rhazes) in the 9th century, recorded clinical cases of his own experience and provided very useful recordings of various diseases, and with its introduction of measles and smallpox, it was very influential in Europe. The Arab doctor al-Kindi wrote the De Gradibus, in which he demonstrated the application of mathematics to medicine, particularly in the field of pharmacology. This includes the development of a mathematical scale to quantify the strength of drugs, and a system that would allow a doctor to determine in advance the most critical days of a patient's illness, based on the phases of the Moon.[115]

Abu al-Qasim (Abulcasis), regarded as the father of modern surgery,[116] contributed greatly to the discipline of medical surgery with his Kitab al-Tasrif ("Book of Concessions"), a 30-volume medical encyclopedia which was later translated to Latin and used in European medical schools for centuries. He invented numerous surgical instruments, including the first instruments unique to women,[117] as well as the surgical uses of catgut and forceps, the ligature, surgical needle, scalpel, curette, retractor, surgical spoon, sound, surgical hook, surgical rod, and specula,[118] and bone saw.[54] Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen) made important advances in eye surgery, and he studied and correctly explained the process of sight and visual perception for the first time in his Book of Optics, published in 1021.[117]

Abū Alī ibn Sīnā (Avicenna), who is considered the father of modern medicine and one of the greatest medical scholars in history,[114] wrote The Canon of Medicine and The Book of Healing, which remained popular textbooks in the Islamic world and medieval Europe for centuries. Avicenna's contributions to medicine include his introduction of systematic experimentation and quantification into the study of physiology,[119] the discovery of the contagious nature of infectious diseases, the introduction of quarantine to limit the spread of contagious diseases, the introduction of clinical trials,[120] the first descriptions on bacteria and viral organisms,[121] the distinction of mediastinitis from pleurisy, the contagious nature of phthisis and tuberculosis, the distribution of diseases by water and soil, and the first careful descriptions of skin troubles, sexually transmitted diseases, perversions, and nervous ailments,[114] as well the use of ice to treat fevers, and the separation of medicine from pharmacology, which was important to the development of the pharmaceutical sciences.[117]

In 1242, the Arab physician Ibn al-Nafis was the first to describe human blood circulation and pulmonary circulation. Ibn al-Lubudi (1210-1267) rejected the theory of four humours supported by Galen and Hippocrates, discovered that the body and its preservation depend exclusively upon blood, rejected Galen's idea that women can produce sperm, and discovered that the movement of arteries are not dependant upon the movement of the heart, that the heart is the first organ to form in a fetus' body (rather than the brain as claimed by Hippocrates), and that the bones forming the skull can grow into tumors.[122]

During the Black Death bubonic plague in 14th century al-Andalus, Ibn Khatima and Ibn al-Khatib discovered that infecious diseases are caused by microorganisms which enter the human body.[123] In the 15th century, the Persian work by Mansur ibn Ilyas entitled Tashrih al-badan ("Anatomy of the body") contained comprehensive diagrams of the body's structural, nervous and circulatory systems.[2]

Other medical inventions and innovations from the Muslim world include oral anesthesia, inhalant anesthesia, distilled alcohol, medical drugs, chemotherapeutical drugs, injection syringe, and a number of antiseptics and other medical treatments. (See Islamic medicine for more details.)

Other sciences

Many other advances were made by Muslim scientists in biology (anatomy, botany, evolution, physiology and zoology), the earth sciences (anthropology, cartography, geodesy, geography and geology), psychology (experimental psychology, psychiatry, psychophysics and psychotherapy), and the social sciences (demography, economics, sociology, history and historiography).

Some of the most famous scientists from the Islamic world include Geber (polymath, father of chemistry), Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī (father of algebra and algorithms), al-Farabi (polymath), Abu al-Qasim (father of modern surgery),[124] Ibn al-Haytham (polymath, father of optics, founder of experimental psychology, pioneer of scientific method, "first scientist")[84], Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī (polymath, father of Indology[125] and geodesy, "first anthropologist"),[126] Avicenna (polymath, father of momentum[127] and modern medicine),[128] Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī (polymath), and Ibn Khaldun (father of demography,[129] cultural history,[130] historiography,[131] the philosophy of history, sociology,[132] and the social sciences),[133] among many others.

Other achievements

Architecture

The Great Mosque of Xi'an in China was completed circa 740, and the Great Mosque of Samarra in Iraq was completed in 847. The Great Mosque of Samarra combined the hypostyle architecture of rows of columns supporting a flat base above which a huge spiraling minaret was constructed.

The Spanish Muslims began construction of the Great Mosque at Cordoba in 785 marking the beginning of Islamic architecture in Spain and Northern Africa (see Moors). The mosque is noted for its striking interior arches. Moorish architecture reached its peak with the construction of the Alhambra, the magnificent palace/fortress of Granada, with its open and breezy interior spaces adorned in red, blue, and gold. The walls are decorated with stylized foliage motifs, Arabic inscriptions, and arabesque design work, with walls covered in glazed tiles.

Another distinctive sub-style is the architecture of the Mughal Empire in India in the 15-17th centuries. Blending Islamic and Hindu elements, the emperor Akbar constructed the royal city of Fatehpur Sikri, located 26 miles (42 km) west of Agra, in the late 1500s and his son Shah Jahan had constructed the mausoleum of Taj Mahal for Mumtaz Mahal in the 1650s, though this time period is well after the Islamic Golden Age.

Arts

The golden age of Islamic (and/or Muslim) art lasted from 750 to the 16th century, when ceramics, glass, metalwork, textiles, illuminated manuscripts, and woodwork flourished. Lusterous glazing became the greatest Islamic contribution to ceramics. Manuscript illumination became an important and greatly respected art, and portrait miniature painting flourished in Persia. Calligraphy, an essential aspect of written Arabic, developed in manuscripts and architectural decoration.

Literature

The most well known fiction from the Islamic world was The Book of One Thousand and One Nights (Arabian Nights), which was a compilation of many earlier folk tales. The epic took form in the 10th century and reached its final form by the 14th century; the number and type of tales have varied from one manuscript to another.[134] All Arabian fantasy tales were often called "Arabian Nights" when translated into English, regardless of whether they appeared in The Book of One Thousand and One Nights, in any version, and a number of tales are known in Europe as "Arabian Nights" despite existing in no Arabic manuscript.[134]

This epic has been influential in the West since it was translated in the 18th century, first by Antoine Galland.[135] Many imitations were written, especially in France.[136] Various characters from this epic have themselves become cultural icons in Western culture, such as Aladdin, Sinbad and Ali Baba. Part of its popularity may have sprung from the increasing historical and geographical knowledge, so that places of which little was known and so marvels were plausible had to be set further "long ago" or farther "far away"; this is a process that continues, and finally culminate in the fantasy world having little connection, if any, to actual times and places.

A number of elements from Arabic and Persian mythology are now common in modern fantasy, such as genies, bahamuts, magic carpets, magic lamps, etc.[136] When L. Frank Baum proposed writing a modern fairy tale that banished stereotypical elements, he included the genie as well as the dwarf and the fairy as stereotypes to go.[137]

The Shahnameh, the national epic of Iran, is a mythical and heroic retelling of Persian history. Amir Arsalan was also a popular mythical Persian story, which has influenced some modern works of fantasy fiction, such as The Heroic Legend of Arslan.

Philosophy

Arab philosophers like al-Kindi, and Ibn Rushd (Averroes) and Persian philosophers like Ibn Sina (Avicenna) played a major role in preserving the works of Aristotle, whose ideas came to dominate the non-religious thought of the Christian and Muslim worlds. They would also absorb ideas from China, and India, adding to them tremendous knowledge from their own studies. Three speculative thinkers, al-Kindi, al-Farabi, and Avicenna (Ibn Sina), fused Aristotelianism and Neoplatonism with other ideas introduced through Islam.

From Spain the Arabic philosophic literature was translated into Hebrew, Latin, and Ladino, contributing to the development of modern European philosophy. The Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides, muslim sociologist-historian Ibn Khaldun, Carthage citizen Constantine the African who translated Greek medical texts, and the muslim Al-Khwarzimi's collation of mathematical techniques were important figures of the Golden Age.

One of the most influential Muslim philosophers in the West was Averroes (Ibn Rushd), founder of the Averroism school of philosophy, and who is regarded as a founding father of secular thought in Western Europe.[138]

Ghazali, the famous Persian jurist and philosopher, wrote a devastating critique in his Tahafut al-Falasifa on the speculative theological works of Kindi, Farabi and Ibn Sina (Avicenna). Philosophy in the Muslim world never recovered from this critique, even though Ibn Rushd (Averroes) responded strongly in his Tahafut al-Tahafut to many of the points Ghazali raised.

Other influential Muslim philosophers include al-Jahiz, a pioneer of evolutionary thought and natural selection; Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen), a pioneer of phenomenology and the philosophy of science, and a critic of Aristotle's concept of place (topos); and Ibn Khaldun, considered the father of the philosophy of history and a pioneer of social philosophy.

End of the Golden Age

Mongol invasion

In 1206, Genghis Khan from Central Asia established a powerful Mongol Empire. A Mongolian ambassador to the Caliph in Baghdad is said to have been murdered,[2] which may have been the cause of Hulagu Khan's sack of Baghdad in 1258.

The Mongols conquered most of the Eurasian land mass, including both China in the east and much of the old Islamic caliphate and Islamic Khwarezm, as well as Russia and Eastern Europe in the west, and subsequent invasions of the Levant. Later Mongol leaders, such as Timur, though himself became a Muslim, destroyed many cities, slaughtered thousands of people and did irrevocable damage to the ancient irrigation systems of Mesopotamia. These invasions transformed a civil society to a nomadic one.

Eventually, the Mongols that settled in parts of Persia, Central Asia and Russia converted to Islam and in many instances became assimilated into various Muslim Iranian or Turkic peoples (for instance, one of the greatest Muslim astronomers of the 15th century, Ulugh Beg, was a grandson of Timur). The Ottoman Empire rose from the ashes, but the Golden Age was over.

Causes of decline

"The achievements of the Arabic speaking peoples between the ninth and twelfth centuries are so great as to baffle our understanding. The decadence of Islam and of Arabic is almost as puzzling in its speed and completeness as their phenomenal rise. Scholars will forever try to explain it as they try to explain the decadence and fall of Rome. Such questions are exceedingly complex and it is impossible to answer them in a simple way."

— George Sarton, The Incubation of Western Culture in the Middle East [139]

The Islamic civilisation which had at the outset been creative and dynamic in dealing with issues, began to struggle to respond to the challenges and rapid changes it faced during the 12th and 13th century onwards towards the end of the Abbassid rule. Despite a brief respite with the new Ottoman rule, the decline continued until its eventual collapse and subsequent stagnation in the 20th century.

Despite a number of attempts by many writers, historical and modern, none seem to agree on the causes of decline.

The main views on the causes of decline comprise the following: political mismanagement after the early Caliphs (10th century onwards), closure of the gates of ijtihad (independent reasoning) and the institutionalisation of taqleed (imitation) rather than ijtihad or bid‘ah (innovation) by the 13th century, foreign involvement by invading forces and colonial powers (11th century Crusades, 13th century Mongol Empire, 15th century Reconquista, 19th century European empires), and the disruption to the cycle of equity based on Ibn Khaldun's famous model of Asabiyyah (the rise and fall of civilizations).

Tolerance about different ideas reduced and faded. Seminaries systematically forbade philosophical thought which comprising both natural and theological aspects of world in Islamic context. Even polemic debates were abandoned after the 13th century. Institutions of science comprising Islamic universities, libraries (including the House of Wisdom), observatories, and hospitals, had been destroyed by foreign invaders like the Mongols and never promoted again.[140] Not only wasn't new publishing equipment accepted but also wide illiteracy overwhelmed Muslim society.

Some historians have recently come to question the traditional picture of decline, pointing to continued astronomical activity as a sign of a continuing and creative scientific tradition through to the 15th century, of which the works of Ibn al-Shatir (1304–1375) and Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406) are considered two of the most noteworthy examples.[141][142]

Criticism of ascribing the Golden Age to Islam

The issue of Islamic Civilization being a misnomer has been raised by a number of recent scholars such as the secular Iranian historian, Dr. Shoja-e-din Shafa in his recent controversial books titled Rebirth (Persian: تولدى ديگر) and After 1400 Years (Persian: پس از 1400 سال) manifesting the intrinsic contradiction of expressions like "Islamic civilization", "Islamic science", "Islamic medicine", "Islamic astronomy", "Islamic scientists", etc. Shafa states that while religion has been a cardinal foundation for nearly all empires of antiquity to derive their legitimacy from, it does not possess adequate defining factors to advance a kingdom or domain in accumulation and furtherance of science, technology, arts, and culture in a way to justify attribution of such developments to existence and practice of a certain faith within that realm. While various empires in the course of mankind's history advocated and officialized the religion they deemed most appropriate to exercise their absolute authority over the masses, we never ascribe their achievements to the faith they practiced. Ergo, using Islamic attribute for the abovementioned terms is as impertinent as arbitrarily concocted namings such as "Christian Civilization" for the totality of "Roman Empire" as of Constantine I's reign onwards, "Byzantine Empire" and all subsequent European empires that advocated Christianity one way or another; or "Zoroastrian Architecture" for all the architectural innovations and marvels that pre-Islamic Persian Empire later loaned to its Muslim conquerors.

Shafa particularly points out that counting all scholars in the Islamic empires as muslims, can also be misleading, since with the harsh punishment and prosecution awaiting alleged heretics and Zendiqs, no sane scientist or intellectual would dare express his/her true faith and religious thoughts. To exemplify this matter, Shafa alludes to two of the most prominent physicians/philosophers of the Islamic era, namely Avicenna and Rhazes; the former being a true muslim that was charged with heresy for mere utterance of his philosophical ideas; and the latter daringly and openly criticizing revelational religions (viz. Islam, Christianity, Judaism, Zoroastrianism) in three of his controversial treatises, exposing himself to great peril. Bearing this personality comparison in mind, factors other than Islamic thought should be considered to have contributed to the great achievements of such individuals.

Bernard Lewis states:[143]

"There have been many civilizations in human history, almost all of which were local, in the sense that they were defined by a region and an ethnic group. This applied to all the ancient civilizations of the Middle East—Egypt, Babylon, Persia; to the great civilizations of Asia—India, China; and to the civilizations of Pre-Columbian America. There are two exceptions: Christendom and Islam. These are two civilizations defined by religion, in which religion is the primary defining force, not, as in India or China, a secondary aspect among others of an essentially regional and ethnically defined civilization. Here, again, another word of explanation is necessary."

Notes

- ^ Matthew E. Falagas, Effie A. Zarkadoulia, George Samonis (2006). "Arab science in the golden age (750–1258 C.E.) and today", The FASEB Journal 20, p. 1581-1586.

- ^ a b c Howard R. Turner, Science in Medieval Islam, University of Texas Press, November 1, 1997, ISBN 0-292-78149-0, pg. 270 (book cover, last page) Cite error: The named reference "Turner" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f g Vartan Gregorian, "Islam: A Mosaic, Not a Monolith", Brookings Institution Press, 2003, pg 26-38 ISBN 081573283X

- ^ a b c d e Arnold Pacey, "Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-Year History", MIT Press, 1990, ISBN 0262660725 pg 41-42

- ^ Dato' Dzulkifli Abd Razak, Quest for knowledge, New Sunday Times, 3 July 2005.

- ^ N. M. Swerdlow (1993). "Montucla's Legacy: The History of the Exact Sciences", Journal of the History of Ideas 54 (2), p. 299-328 [320].

- ^ Bülent Þenay. "Sufism". Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ "Muslim History and the Spread of Islam from the 7th to the 21st century". The Islam Project. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Hobson-29-castrlufbkzxhjkyzfizdtrfeh30was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Subhi Y. Labib (1969), "Capitalism in Medieval Islam", The Journal of Economic History 29 (1), p. 79-96.

- ^ John M. Hobson (2004), The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation, p. 29-30, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521547245.