Central Europe: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

→Central Europe: a discussed concept: Inserted de Martonne's definition. Added citation. |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

== Central Europe: a discussed concept == |

== Central Europe: a discussed concept == |

||

The issue how to name and define the Central European region is subject to debates. Very often, the definition depends on nationality and historical perspective of its author. |

The issue how to name and define the Central European region is subject to debates. Very often, the definition depends on nationality and historical perspective of its author. |

||

In ''Géographie universelle'' (1927), edited by [[Paul Vidal de la Blache]] and [[Lucien Gallois]]), author [[:fr:Emmanuel de Martonne|Emmanuel de Martonne]], the Central European countries are: Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Polan, Hungary and Romania. Italy and Jugoslavia are not considerd by the author to be Central European because they are located mostly outside Central Europe. The author use both Human and Physical Geographical features to define Central Europe.<ref>[http://img73.imageshack.us/img73/5269/file0039ao0.jpg ], [http://img12.imageshack.us/img12/4384/martonne1.jpg ] and [http://img98.imageshack.us/img98/1867/martonne2a.jpg ]</ref>. |

|||

According to [[Ronald Tiersky]], the 1991 summit held in [[Visegrád]], [[Hungary]] and attended by the [[Poland|Polish]], [[Hungary|Hungarian]] and [[Czechoslovakia|Czechoslovak]] presidents was hailed at the time as a major breakthrough in Central European cooperation, but the [[Visegrád Group]] became a vehicle for coordinating Central Europe's road to Europe, while development of closer ties within the region languished.<ref>[[Ronald Tiersky|Tiersky]], p. 472</ref> |

According to [[Ronald Tiersky]], the 1991 summit held in [[Visegrád]], [[Hungary]] and attended by the [[Poland|Polish]], [[Hungary|Hungarian]] and [[Czechoslovakia|Czechoslovak]] presidents was hailed at the time as a major breakthrough in Central European cooperation, but the [[Visegrád Group]] became a vehicle for coordinating Central Europe's road to Europe, while development of closer ties within the region languished.<ref>[[Ronald Tiersky|Tiersky]], p. 472</ref> |

||

| Line 64: | Line 66: | ||

File:Central Europe (Mayers Enzyklopaedisches Lexikon).PNG|Central Europe according to Mayers Enzyklopaedisches Lexikon (1980) |

File:Central Europe (Mayers Enzyklopaedisches Lexikon).PNG|Central Europe according to Mayers Enzyklopaedisches Lexikon (1980) |

||

File:Central Europe (Meyers Grosses Taschenlexikon).PNG|The Central European Countries according to Meyers grosses Taschenlexikon (1999):<br>{{legend|#FF0000|Countries usually considered Central European}}{{legend|#FB607F|Central European countries in the broader sense of the term}}{{legend|#FFB6C1|Countries occasionaly considered to be Central European}} |

File:Central Europe (Meyers Grosses Taschenlexikon).PNG|The Central European Countries according to Meyers grosses Taschenlexikon (1999):<br>{{legend|#FF0000|Countries usually considered Central European}}{{legend|#FB607F|Central European countries in the broader sense of the term}}{{legend|#FFB6C1|Countries occasionaly considered to be Central European}} |

||

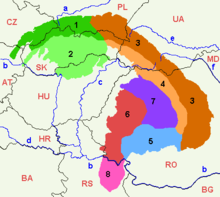

File:Central Europe (Geographie universelle, 1927).PNG|[[Interwar period|Interwar]] Central Europe, according to the French geographer Emmanuel de Martonne (1927) |

|||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

Revision as of 15:33, 4 May 2009

It has been suggested that Mitteleuropa, Talk:Mitteleuropa#Merge with Central Europe and date be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since November 2008. |

This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. (January 2009) |

Central Europe is the region lying between the variously defined areas of "Cold war" Eastern and Western Europe. In addition, Northern, Southern and Southeastern Europe may variously delimit or overlap into Central Europe. The term and widespread interest in the region itself came back into fashion[1] after the end of the Cold War, which had divided Europe politically into East and West, with the Iron Curtain splitting "Central Europe" in half. Scholars assert that a distinct "Central European culture, as controversial and debated the notion may be, exists."[2][3] It is based on "similarities emanating from historical, social and cultural characteristics".[4][5]

States

The understanding of the concept of Central Europe is an ongoing source of controversy[6], though the Visegrád Group constituents are generally included as de facto C.E. countries.[1] The region is usually considered to include:

Sometimes, the region may include ![]() Croatia and

Croatia and ![]() Romania. Rarely Vojvodina[7] (Serbia), Zakarpattia Oblast (Ukraine), Kaliningrad Oblast (Russia), Lorraine and Alsace (France) and Northeastern Italy are considered as part of Central Europe.

Romania. Rarely Vojvodina[7] (Serbia), Zakarpattia Oblast (Ukraine), Kaliningrad Oblast (Russia), Lorraine and Alsace (France) and Northeastern Italy are considered as part of Central Europe.

Definition

Rather than a physical entity, Central Europe is a concept of shared history which contrasts with that of the surrounding regions. The pagans of Central Europe were converted to Roman Catholicism while in Southeastern and Eastern Europe they were brought in the fold of the Eastern Orthodox Church.[8]

Multinational empires were a characteristic of Central Europe.[9] Hungary and Poland, small and medium-size states today, were empires during their early histories.[10] The historical Kingdom of Hungary was until 1918 three times larger than Hungary is today[11], while Poland was the largest state in Europe in the sixteenth century.[12] Both these kingdoms housed a wide variety of different peoples.[13]

Up to World War I, it was distinguished from the region immediately to its west as an area of relative political conservatism opposed to the liberalism of France and Great Britain and the influences of the French Revolution.[citation needed]. In the nineteenth century, while France developed into a republic and Britain was a liberal parliamentary monarchy in which the monarch had very little real power, Austria–Hungary and Prussia (later Germany), in contrast, remained conservative monarchies in which the monarch and his court played a central governmental role, while still subject to some influence by religion.

In the English language, the concept of Central Europe largely fell out of usage during Cold War, overshadowed by notions of Eastern and Western Europe. However, the term is increasingly returning to everyday usage again, partly due to the recent expansion of the European Union, but mainly through the attempt by post-Communist governments in former Eastern European lands to create national images distancing themselves from their predecessors.

Central Europe: a discussed concept

The issue how to name and define the Central European region is subject to debates. Very often, the definition depends on nationality and historical perspective of its author.

In Géographie universelle (1927), edited by Paul Vidal de la Blache and Lucien Gallois), author Emmanuel de Martonne, the Central European countries are: Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Polan, Hungary and Romania. Italy and Jugoslavia are not considerd by the author to be Central European because they are located mostly outside Central Europe. The author use both Human and Physical Geographical features to define Central Europe.[14].

According to Ronald Tiersky, the 1991 summit held in Visegrád, Hungary and attended by the Polish, Hungarian and Czechoslovak presidents was hailed at the time as a major breakthrough in Central European cooperation, but the Visegrád Group became a vehicle for coordinating Central Europe's road to Europe, while development of closer ties within the region languished.[15]

Peter J. Katzenstein described Central Europe as a way station in a Europeanization process that marks the transformation process of the Visegrád Group countries in different, though comparable ways.[16] According to him in Germany's contemporary public discourse "Central European identity" refers to the civilizational divide between Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.[17] He says there's no precise, uncontestable way to decide whether the Baltic states, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Romania, and Bulgaria are parts of Central Europe or not.[18]

In his work Central Europe:enemies, neighbors, friends (Oxford University Press) Lonnie R. Johnson points out criteria to distinguish Central Europe from Western, Eastern and Southeast Europe:[19]

- one criterion for defining Central Europe is the frontiers of medieval empires and kingdoms that largely correspond to the religious frontiers between the Roman Catholic West and the Orthodox East.[20]

- as a mode of self-perception, despite the debated nature of the concept Central Europeans generally agree on which peoples are to be excluded from this club: for example Serbs, Bulgarians, Romanians and Russians. [21]

He also thinks that Central Europe is a dynamical historical concept, not a static spatial one. For example, Lithuania, a fair share of Belarus and western Ukraine are in Eastern Europe today, but 250 years ago they were in Poland.[22]

The Columbia Encyclopedia defines Central Europe as: Germany, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Austria, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary.[23] Encarta Encyclopedia does not clearly define the region, but places the same countries into Central Europe in its individual articles on countries, adding Slovenia in "south central Europe".[24]

According to Mayers Enzyklopädisches Lexikon, Band 16, Bibliographisches Institut Mannheim/Wien/Zürich, Lexikon Verlag 1980, Central Europe is a part of Europe composed by the surface of the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, Poland, Switzerland, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Romania, northern marginal regions of Italy and Jugoslavia as well as northeastern France. Sometimes, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg are not regarded as Central European.

The German Encyclopaedia Meyers grosses Taschenlexikon, 1999, defines Central Europe as the central part of Europe with no precise borders to the East and West. The therm ist mostly used to denominate the territory between the Schelde to Vistula and from the Danube to the Moravian Gate. Usually the countries considered to be Central European are Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Poland, the Czech republick, Slovakia, Hungary, in the broader sense Romania too, occasionally also the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg.

The propositions, gathered by Jerzy Kłoczowski, include:[25]

- West-Central and East-Central Europe – this conception, presented in 1950,[26] distinguished two regions in Central Europe: German West-Centre, with imperial tradition of the Reich, and the East-Centre covered by variety of nations from Finland to Greece, placed between great empires of Scandinavia, Germany, Italy and the Soviet Union

- Central Europe as a region connected to the Western civilisation for a very long time, including the German-speaking countries (the German Empire and the Habsburg Monarchy), the Kingdom of Hungary, Bohemia and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Central Europe understood in this way borders on Russia and the South-Eastern Europe (of Byzantine and Turkish heritage), but the exact frontier of the region is difficult to determine (for example Transylvania, an evidently Central European region, became a part of Romania after the dissolution of Austria–Hungary) – this concept seems to be the most acceptable one

- Central Europe as the area of cultural heritage of the Habsburg Empire – a concept which is popular in the region of Danube River

- East-Central Europe as the area of cultural heritage of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth – Ukrainian, Belarusian and Lithuanian historians, in cooperation (since 1990) with Polish historians, insist on the importance of the notion

- A concept underlining the links connecting Ukraine and Belarus with Russia and treating the Russian Empire together with the whole Slavic Orthodox population as one entity – this position is taken by the Russian historiography

- A concept putting an accent on the links with the West, especially from the 19th century and the grand period of liberation and formation of Nation-states – this idea is represented by in the South-Eastern states, which prefer the enlarged concept of the “East Centre” expressing their links with the Western culture

-

According to some English sources a strict definition of Central Europe means the Visegrád Group[1][27]

-

Map of Central Europe, according to Lonnie R. Johnson (1996)[28]Easternmost Western European countries considered to be Central European only in the broader sense of the term.

-

Central Europe according to Columbia Encyclopedia (2009)[23]

-

Central Europe, according to Alice F. A. Mutton in Central Europe. A Regional and Human Geography (1961)

-

Central Europe according to Mayers Enzyklopaedisches Lexikon (1980)

-

The Central European Countries according to Meyers grosses Taschenlexikon (1999):Countries usually considered Central EuropeanCentral European countries in the broader sense of the termCountries occasionaly considered to be Central European

-

Interwar Central Europe, according to the French geographer Emmanuel de Martonne (1927)

Physical geography

Between the Alps and the Baltics

Geography strongly defines Central Europe's borders with its neighbouring regions to the North and South, namely Northern Europe (or Scandinavia) across the Baltic Sea, the Apennine peninsula (or Italy) across the Alps and the Balkan peninsula across the Soča-Krka-Sava-Danube line. The borders to Western Europe and Eastern Europe are geographically less defined and for this reason the cultural and historical boundaries migrate more easily West-East than South-North. The Rhine river which runs South-North through Western Germany is an exception.

Pannonian Plain and Carpathian Basin

Geographically speaking, Carpathian mountains divide the European Plain in two sections: the Central Europe's Pannonian Plain in the west,[30] and the East European Plain, which lie eastward of the Carpathians. Southwards, the Pannonian Plain is bounded by the rivers Sava and Danube- and their respective floodplains.[31] This area mostly corresponds to the borders of the former Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. The Pannonian Plain extends into the following countries: Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Hungary, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia and Ukraine.

Dinaric Alps

As southeastern division of the Eastern Alps,[32] the Dinaric Alps extend for 650 kilometres along the coast of the Adriatic Sea (northwest-southeast), from the Julian Alps in the northwest down to the Šar-Korab massif, where the mountain direction changes to north-south. According to the Freie Universitaet Berlin[33] this mountain chain is classified as South Central European.

Flora

The Central European Flora region stretches from Central France (Massif Central) to Central Romania (Carpathians) and Southern Scandinavia.[34]

History of the concept

Mitteleuropa

The concept of Central Europe was already known at the beginning of the 19th century,[35] but its real life began in the 20th century and immediately became an object of intensive interest. However, the very first concept mixed science, politics and economy – it was strictly connected with intensively growing German economy and its aspirations to dominate a part of European continent called Mitteleuropa. The German term denoting Central Europe was so fashionable that other languages started referring to it when indicating territories from Rhine to Vistula, or even Dnieper, and from the Baltic Sea to the Balkans.[36] An example of that-time vision of Central Europe may be seen in J. Partsch’s book of 1903.[37]

On 21 January 1904 - Mitteleuropäischer Wirtschaftsverein (Central European Economic Association) was established in Berlin with economic integration of Germany and Austria–Hungary (with eventual extension to Switzerland, Belgium and the Netherlands) as its main aim. Another time, the term Central Europe became connected to the German plans of political, economic and cultural domination. The “bible” of the concept was Friedrich Naumann’s book Mitteleuropa[38] in which he called for an economic federation to be established after the war. Naumann's idea was that the federation would have at its center Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire but would also include all European nations outside the Anglo-French alliance, on one side, and Russia, on the other.[39] The concept failed after the German defeat in the World War I and the dissolution of Austria–Hungary. The revival of the idea may be observed during the Hitler era.

Interwar period

The interwar period (1918–1939) brought new geopolitical system and economic and political problems, and the concept of Central Europe took a different character. The centre of interest was moved to its eastern part – the countries that have reappeared on the map of Europe: Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia. Central Europe ceased to be the area of German aspiration to lead or dominate and became a territory of various integration movements aiming at resolving political, economic and national problems of "new" states, being a way to face German and Soviet pressures. However, the conflict of interests was too big and neither Little Entente nor Międzymorze ideas succeeded.

The interwar period brought new elements to the concept of Central Europe. Before WWI, it embraced mainly German states (Germany, Austria), non-German territories being an area of intended German penetration and domination - German leadership position was to be the natural result of economic dominance.[40] After the war, the Eastern part of Central Europe was placed at the centre of the concept. At that time the scientists took interest in the idea: the International Historical Congress in Brussels in 1923 was committed to Central Europe, and the 1933 Congress continued the discussions.

Central Europe behind the Iron Curtain

Following World War II, large parts of Europe that were culturally and historically Western became part of the Eastern bloc. Consequently, the English term Central Europe was increasingly applied only to the westernmost former Warsaw Pact countries (East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary) to specify them as communist states that were culturally tied to Western Europe.[41] This usage continued after the end of the Warsaw Pact when these countries started to undergo transition.

The post-WWII period brought blocking of the research on Central Europe in the Eastern Block countries, as its every result proved the dissimilarity of Central Europe, which was inconsistent with the Soviet doctrine. On the other hand, the topic became popular in Western Europe and the United States, much of the research being carried out by immigrants from Central Europe.[42]. At the end of the communism, publicists and historians in Central Europe, especially anti-communist opposition, came back to their research.[43]

Mitteleuropa, the German term

The German term Mitteleuropa (or alternatively its literal translation into English, Middle Europe[44]) is an ambiguous German concept.[45] It is sometimes used in English to refer to an area somewhat larger than most conceptions of 'Central Europe'; it refers to territories under German(ic) cultural hegemony until World War I (encompassing Austria–Hungary and Germany in their antebellum formations. According to Fritz Fischer Mitteleuropa was a scheme in the era of the Reich of 1871-1918 by which the old imperial elites had allegedly sought to build a system of German economic, military and political domination from the northern seas to the Near East and from the Low Countries through the steppes of Russia to the Caucasus.[46] Professor Fritz Epstein argued the threat of a Slavic "Drang nach Westen" (Western expansion) had been a major factor in the emergence of a Mitteleuropa ideology before the Reich of 1871 ever came into being.[47]

In Germany the connotation is also heavily linked to the pre-war German provinces east of the Oder-Neisse line which were lost as the result of the World War II, annexed by People's Republic of Poland and the Soviet Union, and ethnically cleansed of Germans by communist authorities and forces (see expulsion of Germans after World War II) due to Yalta Conference and Potsdam Conference decisions. In this view Bohemia, with its Western Slavic heritage combined with its historical "Sudetenland", is a core region illustrating the problems and features of the entire Central European region.

The term Mitteleuropa conjures up negative historical associations, although the Germans have not played an exclusively negative role in the region.[48] Most Central European Jews embraced the enlightened German humanistic culture of the 19th century. [49] German-speaking Jews from turn-of-the-century Vienna, Budapest and Prague became representatives of what many consider to be Central European culture at its best, though the Nazi version of "Mitteleuropa" destroyed this kind of culture.[50] Some German speakers are sensitive enough to the pejorative connotations of the term Mitteleuropa to use Zentraleuropa instead.[51] Adolf Hitler was obsessed by the idea of Lebensraum and many non-German Central Europeans identify Mitteleuropa with the instruments he employed to acquire it: war, deportations, genocide.[52]

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Central Europe — The future of the Visegrad group". The Economist. 2005-04-14. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=k9IwimrMIQgC&printsec=frontcover&dq=central+european+culture

- ^ http://ceu.bard.edu/academic/documents/MandatorycourseonCentralEurope.pdf

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=k9IwimrMIQgC&printsec=frontcover&dq=central+european+culture

- ^ http://www.ces.uj.edu.pl/fiut/culture.htm

- ^ "For the Record - The Washington Post - HighBeam Research".

- ^ http://www.vojvodina.gov.rs/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=174&Itemid=83

- ^ Johnson, p.4

- ^ Johnson, p. 4

- ^ Johnson, p. 4

- ^ Johnson, p. 4

- ^ Johnson, p. 4

- ^ Johnson, p. 4

- ^ [1], [2] and [3]

- ^ Tiersky, p. 472

- ^ Katzenstein, p. 6

- ^ Katzenstein, p. 6

- ^ Katzenstein, p. 4

- ^ "Central Europe: enemies, neighbors, friends", by Lonnie R. Johnson, Oxford University Press, 1996

- ^ Johnson, p.4

- ^ Johnson, p. 6

- ^ Johnson, p. 4

- ^ a b "Europe". Columbia Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. 2009.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "[[Encarta]]". 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ Jerzy Kłoczowski, Actualité des grandes traditions de la cohabitation et du dialogue des cultures en Europe du Centre-Est, in: L'héritage historique de la Res Publica de Plusieurs Nations, Lublin 2004, pp. 29–30

- ^ Oskar Halecki, The Limits and Divisions of European History, Sheed & Ward: London and New York 1950, chapter VII

- ^ Tiersky, p. 472

- ^ Johnson, p.11-12

- ^ "The World Factbook: Field listing - Location". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ^ "Dark Series Research by Christine Feehan".

- ^ www.icpdr.org/icpdr-files/14017

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/163795/Dinaric-Alps

- ^ http://www.grin.com/e-book/37159/die-alpen-hoehenstufen-und-vegetation

- ^ Wolfgang Frey and Rainer Lösch; Lehrbuch der Geobotanik. Pflanze und Vegetation in Raum und Zeit. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, München 2004

- ^ S. Philipps, Mitteleuropa – Origins and pertinence of a political concept,

- ^ A. Podraza, Europa Środkowa jako region historyczny, 17th Congress of Polish Historians, Jagiellonian University 2004

- ^ Joseph Franz Maria Partsch, Clementina Black, Halford John Mackinder, Central Europe, New York 1903

- ^ F. Naumann, Mitteleuropa, Berlin: Reimer, 1915

- ^ http://science.jrank.org/pages/11015/Regions-Regionalism-Eastern-Europe-Central-versus-Eastern-Europe.html Regions and Eastern Europe Regionalism - Central Versus Eastern Europe

- ^ http://www.essex.ac.uk/ecpr/events/graduateconference/barcelona/papers/681.pdf S. Philipps, Mitteleuropa – Origins and pertinence of a political concept, p. 6

- ^ ""Central versus Eastern Europe"".

- ^ One of the main representatives was Oscar Halecki and his book The limits and divisions of European history, London and New York 1950

- ^ A. Podraza, Europa Środkowa jako region historyczny, 17th Congress of Polish Historians, Jagiellonian University 2004

- ^ Johnson, p. 165

- ^ Johnson, p. 165

- ^ Hayes, p. 16

- ^ Hayes, p. 17

- ^ Johnson, p. 6

- ^ Johnson, p. 7

- ^ Johnson, p. 7

- ^ Johnson, p. 165

- ^ Johnson, p. 170

References

- Hayes, Bascom Barry (1994). Bismarck and Mitteleuropa. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 9780838635124.

- Johnson, Lonnie R. (1996). Central Europe: enemies, neighbors, friends. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195100716.

- Katzenstein, Peter J. (1997). Mitteleuropa: Between Europe and Germany. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781571811240.

- Tiersky, Ronald (2004). Europe today. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742528055.

Further reading

- Jacques Rupnik, "In Search of Central Europe: Ten Years Later", in Gardner, Hall, with Schaeffer, Elinore & Kobtzeff, Oleg, (ed.), Central and South-central Europe in Transition, Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2000 (translated form French by Oleg Kobtzeff)

- Article 'Mapping Central Europe' in hidden europe, 5, pp. 14–15 (November 2005)

- A journal in three languages (English, German, French) dealing with the region: http://www.ece.ceu.hu

![According to some English sources a strict definition of Central Europe means the Visegrád Group[1][27]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b6/Visegrad_group_countries.png/117px-Visegrad_group_countries.png)

![Map of Central Europe, according to Lonnie R. Johnson (1996)[28] Countries usually considered Central European (citing the World Bank and the OECD) Easternmost Western European countries considered to be Central European only in the broader sense of the term.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ac/Central_Europe_%28Lonnie_R._Johnson%29.PNG/120px-Central_Europe_%28Lonnie_R._Johnson%29.PNG)

![Central Europe according to The World Factbook (2009)[29] and Brockhaus Enzyklopädie (1998)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/41/Central_Europe_%28Brockhaus%29.PNG/117px-Central_Europe_%28Brockhaus%29.PNG)

![Central Europe according to Columbia Encyclopedia (2009)[23]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/Central-Europe-map2.png/118px-Central-Europe-map2.png)