Mary, mother of Jesus: Difference between revisions

as the source states, the figures Joachim and Anne are first mentioned by the early church only circa 170-80 AD - their existence is controversial |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 375: | Line 375: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

* [http://www.churchfathers.org/category/mary-and-the-saints/mary-without-sin/ Church Fathers on the Sinless Nature of Mary] |

|||

{{Commons|Virgin Mary}} |

|||

* [http://www.churchfathers.org/category/mary-and-the-saints/mary-ever-virgin/ Church Fathers on the Perpetual Virginity of Mary] |

|||

* [http://www.mariologicalsociety.com/ Marilogical Society of America] |

* [http://www.mariologicalsociety.com/ Marilogical Society of America] |

||

* [http://campus.udayton.edu/mary/aboutmary2.html University of Dayton─The Mary Page] |

* [http://campus.udayton.edu/mary/aboutmary2.html University of Dayton─The Mary Page] |

||

Revision as of 04:12, 10 October 2010

It has been suggested that this article be merged with Blessed Virgin Mary (Roman Catholic). (Discuss) Proposed since September 2010. |

- This article is an overview. For specific views, see: Anglican, Ecumenical, Islamic, Lutheran, Protestant, and Catholic perspectives.

Mary of Nazareth | |

|---|---|

The Madonna in Sorrow, by Sassoferrato, 17th century. | |

| Born | Unknown, circa 20 BC; celebrated 8 September[1] |

| Nationality | Israelite, Roman Empire[2] |

| Spouse | Joseph[3][4] |

| Children | Jesus |

| Parent(s) | (Early Church View): Joachim and Anne[5] |

Mary of Nazareth (September 8, 20 BC? - August 15, 45 AD?) Aramaic, Hebrew: מרים, Maryām, Miriam; Arabic:مريم, Maryam was a Jewish woman of Nazareth in Galilee. She is identified in the New Testament as the mother of Jesus Christ through divine intervention.Mt. 1:16,18–25 Lk. 1:26–56 2:1–7[3]

The New Testament describes Mary as a virgin (Greek παρθένος, parthénos).[6] Christians believe that she conceived her son, Jesus Christ, miraculously by the agency of the Holy Spirit. This took place when she was already betrothed (engaged) to Joseph and was awaiting the concluding rite of Jewish marriage, the formal home-taking ceremony.[7] She married Joseph and accompanied him to Bethlehem, where Jesus was born.[3][4]

The New Testament begins its account of Mary's life with the Annunciation, where angel Gabriel appeared to her and announced her divine selection to be mother of Jesus. Church tradition and early non-biblical writings state that her parents were an elderly couple named Joachim and Anne. The Bible records Mary's role in key events of the life of Jesus from his virgin birth to his crucifixion. Other apocryphal writings tell of her subsequent death and bodily assumption into heaven.

Most Christian traditions believe that Mary, as mother of Jesus, is the Mother of God (Μήτηρ Θεοῦ) and the Theotokos, literally, Birthgiver of God. Mary has been an object of veneration in the Christian church since the apostolic age. Throughout the ages she has been a favorite subject in Christian art, music, and literature.

There is significant diversity in the Marian beliefs and devotional practices of major Christian traditions, e.g. the Catholic Church has a number of Marian dogmas such as the Immaculate Conception and venerate her as intercessor and mother of the church, Protestants do not share these beliefs.[8][9]

In Islam Mary is regarded as the virgin mother of Jesus (Jesus is understood as one of the prophets). She is described in the Qur'an, in the Sura Maryam (Template:Lang-ar).

In ancient sources

New Testament

The New Testament account of her humility and obedience to the message of God have made her an exemplar for all ages of Christians. Out of the details supplied in the New Testament by the Gospels about the maid of Galilee, Christian piety and theology have constructed a picture of Mary that fulfills the prediction ascribed to her in the Magnificat (Luke 1:48): "Henceforth all generations will call me blessed."

— "Mary." Web: 29Sep2010 Encyclopedia Britannica Online.

The name "Mary" comes from the Greek Μαρία, which is a shortened form of Μαριάμ. The New Testament name was based on the Hebrew name מִרְיָם or Miryam.[10]

Mary, the mother of Jesus, is mentioned by name fewer than twenty times in the New Testament.

Specific references

- Luke's gospel mentions Mary most often, identifying her by name twelve times, all of these in the infancy narrative (1:27,30,34,38,39,41,46,56; 2:5, 16,19,34).

- Matthew's gospel mentions her by name five times, four of these (1:16,18,20; 2:11) in the infancy narrative and only once (13:55) outside the infancy narrative.

- Mark's gospel names her only once (6:3) and mentions her as Jesus' mother without naming her in 3:31.

- John's gospel refers to her twice but never mentions her by name. Described as Jesus' mother, she makes two appearances in John's gospel. She is first seen at the wedding at Cana of GalileeJn 2:1–12 which is mentioned only in the fourth gospel. The second reference in John, also exclusively listed this gospel, has the mother of Jesus standing near the cross of her son together with the (also unnamed) "disciple whom Jesus loved."Jn 19:25–26 John 2:1–12 is the only text in the canonical gospels in which Mary speaks to (and about) the adult Jesus.

- In the Book of Acts, Luke's second writing, Mary and the brothers of Jesus are mentioned in the company of the eleven who are gathered in the upper" room after the ascension.Acts 1:14

- In the Book of Revelation,12:1,5–6 John's apocalypse never explicitly identifies the "woman clothed with the sun" as Mary of Nazareth, the mother of Jesus. However, many interpreters have made that connection.[4]

Family and early life

The New Testament tells little of Mary's early history. Her parents are not named in the canonical New Testament; however, Church tradition and early non-biblical writings name her parents as Joachim and Anne.[11] Mary was a relative of Elizabeth, wife of the priest Zechariah of the priestly division of Abijah, who was herself part of the lineage of Aaron and so of the tribe of Levi.[12]: p.134 Lk 1:5 1:36 In spite of this, some speculate that Mary, like Joseph to whom she was betrothed, was of the House of David and so of the tribe of Judah, and that the genealogy presented in Luke was hers, while Joseph's is given in Matthew.[13] She resided at Nazareth in Galilee, presumably with her parents and during her betrothal–the first stage of a Jewish marriage–the angel Gabriel announced to her that she was to be the mother of the promised Messiah by conceiving him through the Holy Spirit.[14] When Joseph was told of her conception in a dream by "an angel of the Lord", he was surprised; but the angel told him to be unafraid and take her as his wife, which Joseph did, thereby formally completing the wedding rites.[15]Mt 1:18–25

Since the angel Gabriel had told Mary (according to Luke)1:19 that Elizabeth, having previously been barren, was now miraculously pregnant, Mary hurried to visit Elizabeth, who was living with her husband Zechariah in a city of Judah "in the hill country".Lk 1:39 Once Mary arrived at the house and greeted Elizabeth, Elizabeth proclaimed Mary as "the mother of [her] Lord", and Mary recited a song of thanksgiving commonly known as the Magnificat from its first word in Latin.Lk 1:46–56 After three months, Mary returned to her house.Lk 1:56–57 According to the Gospel of Luke, a decree of the Roman emperor Augustus required that Joseph and his betrothed should proceed to Bethlehem for a census. While they were there, Mary gave birth to Jesus; but because there was no place for them in the inn, she had to use a manger as a cradle.[12]: p.14 Lk 2:1ff After eight days, the boy was circumcised according to Jewish law. He was named Jesus in accordance with the instructions that the "angel of the Lord" had given to Joseph after the Annunciation to Mary.Mt. 1:21 Lu. 1:31Template:Bibleverse with invalid book These customary ceremonies were followed by Jesus' presentation to the Lord at the Temple in Jerusalem in accordance with the law for firstborn males, then the visit of the Magi, the family's flight into Egypt, their return after the death of King Herod the Great about 2 or 1 BC and taking up residence in Nazareth.[16]Mt 2

Mary in the life of Jesus

Mary is involved in the only event in Jesus' adolescent life that is recorded in the New Testament: at the age of twelve Jesus, having become separated from his parents on their return journey from the Passover celebration in Jerusalem, was found among the teachers in the temple.[17]: p.210 Lk. 2:41–52

After Jesus' baptism by John the Baptist and his temptations by the devil in the desert, Mary was present when, at her intercession, Jesus worked his first public miracle during the marriage in Cana by turning water into wine.Jn 2:1–11 Subsequently there are events when Mary is present along with James, Joseph, Simon, and Judas, called Jesus' brothers, and unnamed "sisters". Mt 1:24–25 12:46 13:54–56 27:56 Mk 3:31 6:3 15:40 16:1 Jn 2:12 7:3–5 Gal 1:19 Ac 1:14Template:Bibleverse with invalid book These passages have been used to challenge the doctrine of the perpetual virginity of Mary, however both Catholic and Orthodox churches interpret the words commonly translated "brother" and "sister" as actually meaning close relatives (see Perpetual virginity). There is also an incident in which Jesus is sometimes interpreted as rejecting his family. "And his mother and his brothers arrived, and standing outside, they sent in a message asking for himMk 3:21 ... And looking at those who sat in a circle around him, Jesus said, 'These are my mother and my brothers. Whoever does the will of God is my brother, and sister, and mother.'"[18]3:31–35

Mary is also depicted as being present during the crucifixion standing near "the disciple whom Jesus loved" along with Mary of Clopas and Mary Magdalene,Jn 19:25–26 to which list Matthew 27:56 adds "the mother of the sons of Zebedee", presumably the Salome mentioned in Mark 15:40. This representation is called a Stabat Mater.[19][20] Mary, cradling the dead body of her Son, while not recorded in the Gospel accounts, is a common motif in art, called a "pietà" or "pity".

After the Ascension of Jesus

In Acts (1:26, especially v. 14Template:Bibleverse with invalid book), Mary is the only one to be mentioned by name –other than the twelve Apostles and the candidates─of about 120 people gathered, after the Ascension, in the Upper Room on the occasion of the election of Matthias to the vacancy of Judas. (Though it is said that "the women" and Jesus' brothers were there as well, their names are not given). Some also consider the "chosen lady" mentioned in 2Jn 1:1 as Mary. From this time, she disappears from the biblical accounts, although it is held by Catholics that she is again portrayed as the heavenly woman of Revelation.Rev 12:1[original research?]

Her death is not recorded in scripture. However, tradition has her assumed (taken bodily) into Heaven. Belief in the corporeal assumption of Mary is universal to Catholicism, in both Eastern and Western Catholic Churches, as well as the Eastern Orthodox Church,[21][22] and Coptic Churches.[23]

Later Christian writings and traditions

According to the apocryphal Gospel of James Mary was the daughter of St Joachim and St Anne. Before Mary's conception Anna had been barren. Mary was given to service as a consecrated virgin in the Temple in Jerusalem when she was three years old, much like Hannah took Samuel to the Tabernacle as recorded in the Old Testament.[24]

According to Sacred Tradition, Mary died surrounded by the apostles (in either Jerusalem or Ephesus) between three days and 24 years after Christ's ascension. When the apostles later opened her tomb, they found it to be empty and they concluded that she had been assumed into Heaven.[22][25] Mary's Tomb, an empty tomb in Jerusalem, is attributed to Mary.[26]

The House of the Virgin Mary near Ephesus in Turkey is traditionally considered the place where Mary lived until her assumption. The Gospel of John states that Mary went to live with the Disciple whom Jesus loved,Jn 19:27 identified as John the Evangelist. Irenaeus and Eusebius of Caesarea wrote in their histories that John later went to Ephesus, which may provide the basis for the early belief that Mary also lived in Ephesus with John.[27][28]

Christian devotion

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Mariology |

|---|

|

| General perspective |

| Specific views |

|

|

| Prayers and devotions |

| Ecumenical |

|

|

Christian devotion to Mary goes back to the 2nd century and predates the emergence of a specific Marian liturgical system in the 5th century, following the First Council of Ephesus in 431. The Council itself was held at a church in Ephesus which had been dedicated to Mary about a hundred years before.[29][30][31] In Egypt the veneration of Mary had started in the 3rd century and the term Theotokos was used by Origen, the Alexandrian Father of the Church.[32]

The earliest known Marian prayer (the Sub tuum praesidium, or Beneath Thy Protection) is from the 3rd century (perhaps 270), and its text was rediscovered in 1917 on a papyrus in Egypt.[33][34] Following the Edict of Milan in 313, by the 5th century artistic images of Mary began to appear in public and larger churches were being dedicated to Mary, e.g. S. Maria Maggiore in Rome.[35][36][37]

Over the centuries, devotion and veneration to Mary has varied greatly among Christian traditions. For instance, while Protestants show scant attention to Marian prayers or devotions, of all the saints whom the Orthodox venerate, the most honored is Mary, who is considered "more honorable than the Cherubim and and more glorious than the Seraphim".[38]

Orthodox theologian Sergei Bulgakov wrote: "Love and veneration of the Virgin Mary is the soul of Orthodox piety.... A faith in Christ which does not include His Mother is another faith, another Christianity from that of the Orthodox Church."[39]

Although the Catholics and the Orthodox may honor and venerate Mary, they do not view her as divine, nor do they worship her. Catholics view Mary as subordinate to Christ, but uniquely so, in that she is seen as above all other creatures.[40] Similarly Theologian Sergei Bulgakov wrote that although the Orthodox view Mary as "superior to all created beings" and "ceaslessly pray for her intercession" she is not considered a "substitute for the One Mediator" who is Christ.[39] "Let Mary be in honor, but let worship be given to the Lord" he wrote.[41] Similarly, Catholics do not worship Mary, but venerate her. Catholics use the term hyperdulia for Marian veneration rather than latria that applies to God and dulia for other saints.[42] The definition of the three level hierarchy of latria, hyperdulia and dulia goes back to the Second Council of Nicaea in 787.[43]

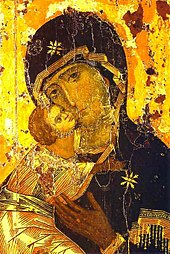

Devotions to artistic depictions of Mary vary among Christian traditions. There is a long tradition of Roman Catholic Marian art and no image permeates Catholic art as the image of Madonna and Child.[44] The icon of the Virgin is without doubt the most venerated icon among the Orthodox.[45] Both Roman Catholics and the Orthodox venerate images and icons of Mary, given that the Second Council of Nicaea in 787 permitted their veneration by Catholics with the understanding that those who venerate the image are venerating the reality of the person it represents,[46] and the 842 Synod of Constantinople established the same for the Orthodox.[47] The Orthodox, however, only pray to and venerate flat, two-dimensional icons and not three-dimensional statues.[48]

The Anglican position towards Mary is in general more conciliatory than that of Protestants at large and in a book he wrote about praying with the icons of Mary, Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury said: "It is not only that we cannot understand Mary without seeing her as pointing to Christ; we cannot understand Christ without seeing his attention to Mary".[49][50]

Titles

Titles to honor Mary or ask for her intercesssion are used by some Christian traditions such as the Eastern Orthodox or Catholics, but not others, e.g. the Protestant. Common titles for Mary include The Blessed Virgin Mary (also abbreviated to "BVM"), Our Lady (Notre Dame, Nuestra Señora, Nossa Senhora, Madonna), Mother of God and the Queen of Heaven (Regina Caeli).[51][52]

Mary is referred to by the Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Anglican Church, and all Eastern Catholic Churches as Theotokos, a title recognized at the Third Ecumenical Council (held at Ephesus to address the teachings of Nestorius, in 431). Theotokos (and its Latin equivalents, "Deipara" and "Dei genetrix") literally means "Godbearer". The equivalent phrase "Mater Dei", (Mother of God) is more common in Latin and so also in the other languages used in the Western Catholic Church, but this same phrase in Greek (Μήτηρ Θεοῦ), in the abbreviated form of the first and last letter of the two words (ΜΡ ΘΥ), is the indication attached to her image in Byzantine icons. The Council stated that the Church Fathers "did not hesitate to speak of the holy Virgin as the Mother of God".[53][54][55]

Some titles have a Biblical basis, for instance the title Queen Mother has been given to Mary since she was the mother of Jesus, who was sometimes referred to as the "King of Kings" due to his lineage of King David. The biblical basis for the term Queen can be seen in the Gospel of Luke 1:32 and the Book of Isaiah 9:6, and Queen Mother from 1 Kings 2:19–20Template:Bibleverse with invalid book and Jeremiah 13:18–19.[56] Other titles have arisen from reported miracles, special appeals or occasions for calling on Mary, e.g. Our Lady of Good Counsel, Our Lady of Navigators or Our Lady of Ransom who protects captives.[57][58][59][60]

The three main titles for Mary used by the Orthodox are Theotokos, i.e., Mother of God (Greek Θεοτόκος), Aeiparthenos, i.e. Ever Virgin (Greek ἀειπάρθενος), as confirmed in the Fifth Ecumenical Council 553, and Pangia, i.e., All Holy (Greek Παναγία).[38] A large number of titles for Mary are used by Roman Catholics, and these titles have in turn given rise to many artistic depictions, e.g. the title Our Lady of Sorrows has resulted in masterpieces such as Michelangelo's Pietà.[61]

Marian feasts

- Main article: Marian feast days (includes lists of feast days)

The earliest feasts that relate to Mary grew out of the cycle of feasts that celebrated the Nativity of Jesus. Given that according to the Gospel of Luke (Luke 2:22–40), forty days after the birth of Jesus, along with the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple Mary was purified according to Jewish customs, the Feast of the Purification began to be celebrated by the 5th century, and became the "Feast of Simeon" in Byzantium.[62]

In the 7th and 8th centuries four more Marian feasts were established in the Eastern Church. In the Western Church a feast dedicated to Mary, just before Christmas was celebrated in the Churches of Milan and Ravenna in Italy in the 7th century. The four Roman Marian feasts of Purification, Annunciation, Assumption and Nativity of Mary were gradually and sporadically introduced into England by the 11th century.[62]

Over time, the number and nature of feasts (and the associated Titles of Mary) and the venerative practices that accompany them have varied a great deal among diverse Christian traditions. Overall, there are significantly more titles, feasts and venerative Marian practices among Roman Catholics than any other Christians traditions.[61] Some such feasts relate to specific events, e.g. the Feast of Our Lady of Victory was based on the 1571 victory of the Papal States in the Battle of Lepanto.[63][64]

Differences in feasts may also originate from doctrinal issues - the Feast of the Assumption is such an example. Given that there is no agreement among all Christians on the circumstances of the death, Dormition or Assumption of Mary, the feast of assumption is celebrated among some denominations and not others. [52][65] While the Catholic Church celebrates the Feast of the Assumption on August 15, some Eastern Catholics celebrate it as Dormition of the Theotokos, and may do so on August 28, if they follow the Julian calendar. The Eastern Orthodox also celebrate it as the Dormition of the Theotokos, one of their 12 Great Feasts. Protestants do not celebrate this, or any other Marian feasts.[52]

Christian doctrines

There is significant diversity in the Marian doctrines accepted by various Christians. The key Marian doctrines can be briefly stated as follows:

- Mother of God: holds that Mary is the Mother of God, as Theotokos.

- Virgin birth of Jesus: states that Mary miraculously conceived Jesus while remaining a virgin.

- Perpetual virginity of Mary: holds that Mary remained a virgin all her life, even in the act of giving birth to Jesus.

- Immaculate Conception (of Mary): states that Mary was conceived without original sin.

- Assumption or Dormition (of Mary): relates to the death or bodily assumption of Mary into Heaven.

The acceptance of these Marian doctrines by Christians can be summarized as follows:[66][67][68][69][70]

| Doctrine | Church action | Accepted by |

|---|---|---|

| Virgin birth of Jesus | First Council of Nicaea, 325 | Roman Catholics, Anglicans, Lutherans, Protestants, Eastern Orthodox, Latter Day Saints |

| Mother of God, Theotokos |

First Council of Ephesus, 431 | Roman Catholics, Anglicans, Lutherans, Protestants, Latter Day Saints (as Mother of Son of God) |

| Perpetual virginity | Council of Constantinople, 533 Smalcald Articles, 1537 |

Roman Catholics, Some Anglicans, Some Lutherans, Martin Luther, John Calvin |

| Immaculate Conception | Ineffabilis Deus encyclical Pope Pius IX, 1854 |

Roman Catholics, Some Anglicans, early Martin Luther |

| Assumption of Mary | Munificentissimus Deus encyclical Pope Pius XII, 1950 |

Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Some Anglicans |

The title "Mother of God" (Theotokos) for Mary was confirmed by the First Council of Ephesus, held at the Church of Mary in 431. The Council decreed that Mary is the Mother of God because her son Jesus is one person who is both God and man, divine and human.[53] This doctrine is widely accepted by Christians in general, and the term Mother of God had already been used within the oldest known prayer to Mary, the Sub tuum praesidium which dates to around 250 AD.[71]

The Virgin birth of Jesus has been a universally held belief among Christians since the second century,[72] It is included in the two most widely used Christian creeds, which state that Jesus "was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary" (the Nicene Creed in what is now its familiar form)[73] and the Apostles' Creed. The Gospel of Matthew describes Mary as a virgin who fulfilled the prophecy of Isaiah 7:14. The authors of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke consider Jesus' conception not the result of intercourse and assert that Mary had "no relations with man" before Jesus' birth.Mt 1:18 Mt 1:25 Lk 1:34 This alludes to the belief that Mary conceived Jesus through the action of God the Holy Spirit, and not through intercourse with Joseph or anyone else.[74]

The perpetual virginity of Mary, asserts Mary's real and perpetual virginity even in the act of giving birth to the Son of God made Man. The term Ever-Virgin (Greek ἀειπάρθενος) is applied in this case, stating that Mary remained a virgin for the remainder of her life, making Jesus her biological and only son, whose conception and birth are held to be miraculous.[74][75][76]

Roman Catholics believe in the Immaculate Conception of Mary, as proclaimed Ex Cathedra by Pope Pius IX in 1854, namely that she was filled with grace from the very moment of her conception in her mother's womb and preserved from the stain of original sin. The Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic Church has a liturgical feast by that name, kept on 8 December.[77] The Eastern Orthodox reject the Immaculate Conception principally because their understanding of ancestral sin (the Greek term corresponding to the Latin "original sin") differs from that of the Roman Catholic Church, but also on the basis that without original sin.[78]

The doctrines of the Assumption or Dormition of Mary relate to her death and bodily assumption to Heaven. While the Roman Catholic Church has established the dogma of the Assumption, namely that the Mary directly went to Heaven without a usual physical death, the Eastern Orthodox Church believes in the Dormition, i.e. that she fell asleep, surrounded by the Apostles.[76][79]

Perspectives on Mary

Chriatian Marian perspectves include a great deal of diversity. While some Christians such as Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox have well established Marian traditions, Protestants at large pay scant attention to Mariological themes. Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Anglican, and some Lutherans venerate the Virgin Mary. This veneration especially takes the form of prayer for intercession with her Son, Jesus Christ. Additionally it includes composing poems and songs in Mary's honor, painting icons or carving statues of her, and conferring titles on Mary that reflect her position among the saints.[38][50][52][61]

Anglican view

The multiple churches that form the Anglican Communion have different views on Marian doctrines and venerative practices given that there is no single church with universal authority within the Communion and that the mother church (the Church of England) understands itself to be both Catholic and Reformed.[80] Thus unlike the Protestant churches at large, the Anglican Communion (which includes the Episcopal Church in the US) includes segments which still retain some veneration of Mary.[50]

Mary's special position within God's purpose of salvation as "God bearer" (Theotokos) is recognised in a number of ways by some Anglican Christians.[81] The Church affirms in the historic creeds that Jesus was born of the Virgin Mary, and celebrates the feast days of the Presentation of Christ in the Temple. This feast is called in older prayer books the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary on 2 February. The Annunciation of our Lord to the Blessed Virgin on March 25 was from before the time of Bede until the 18th century New Year's Day in England. The Annunciation is called the "Annunciation of our Lady" in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. Anglicans also celebrate in the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin on May 31, though in some provinces the traditional date of July 2 is kept. The feast of the St. Mary the Virgin is observed on the traditional day of the Assumption, August 15. The Nativity of the Blessed Virgin is kept on September 8.[50]

The Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary is kept in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, on December 8. In certain Anglo-Catholic parishes this feast is called the Immaculate Conception. Again, the Assumption of Mary is believed in by most Anglo-Catholics, but is considered a pious opinion by moderate Anglicans. Protestant minded Anglicans reject the celebration of these feasts.[50]

Prayers and venerative practices vary a great deal. For instance, as of the 19th century, following the Oxford Movement, Anglo-Catholics frequently pray the Rosary, the Angelus, Regina Caeli, and other litanies and anthems of Our Lady that are reminiscent of Catholic practices.[82] On the other hand, Low Church Anglicans rarely invoke the Blessed Virgin except in certain hymns, such as the second stanza of Ye Watchers and Ye Holy Ones.[81][83]

The Anglican Society of Mary was formed in 1931 and maintains chapters in many countries. The purpose of the society is to foster devotion to Mary among Anglicans.[50][84] The High church espouses doctrines that are closer to Roman Catholics, and retains veneration for Mary, e.g. official Anglican pilgrimages to Our Lady of Lourdes have taken place since 1963.[85]

Historically, there has been enough common ground between Roman Catholics and Anglicans on Marian issues that in 2005 a joint statement called Mary: grace and hope in Christ was produced through ecumenical meetings of Anglicans and Roman Catholic theologians. This document, informally known as the "Seattle Statement", is not formally endorsed by either the Catholic Church or the Anglican Communion, but is viewed by its authors as the beginning of a joint understanding of Mary.[50][86]

Catholic view

In the Catholic Church, Mary is accorded the title "Blessed," (from Latin beatus, blessed, via Greek μακάριος, makarios and Latin facere, make) in recognition of her ascension to Heaven and her capacity to intercede on behalf of those who pray to her. Catholic teachings make clear that Mary is not considered divine and prayers to her are not answered by her, they are answered by God. [88]

Blessed Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus has a more central role in Roman Catholic teachings and beliefs than in any other major Christian group. Not only do Roman Catholics have more theological doctrines and teachings that relate to Mary, but they have more festivals, prayers, devotional, and venerative practices than any other group.[61] The Catholic Catechism states: "The Church's devotion to the Blessed Virgin is intrinsic to Christian worship."[89]

The four Catholic doctrines regarding Mary are: Mother of God, Virgin birth of Jesus, Perpetual virginity of Mary, Immaculate Conception (of Mary) and Assumption of Mary. [76][90][91]

Following the growth of Marian devotions in the 16th century, Catholic saints wrote books such as Glories of Mary and True Devotion to Mary that emphasized Marian veneration and taught that "the path to Jesus is through Mary".[92] Marian devotions are at times linked to Christocentric devotions, e.g. the Alliance of the Hearts of Jesus and Mary.[93]

Key Marian devotions include: Seven Sorrows of Mary, Rosary and scapular, Miraculous Medal and Reparations to Mary.[94][95] The months of May and October are traditionally "Marian months" for Roman Catholics, e.g. the daily Rosary is encouraged in October and in May Marian devotions take place in many regions.[96][97][98] Popes have issued a number of Marian encyclicals and Apostolic Letters to encourage devotions to and the veneration of the Virgin Mary.

Catholics place high emphasis on Mary's roles as protector and intercessor and the Catholic Catechism refers to Mary as the "Mother of God to whose protection the faithful fly in all their dangers and needs".[99][100][101][102][103] Key Marian prayers include: Hail Mary, Alma Redemptoris Mater, Sub Tuum Praesidum, Ave Maris Stella, Regina Coeli, Ave Regina Coelorum and the Magnificat.[104]

Mary's participation in the processes of salvation and redemption has also been emphasized in the Catholic tradition, but they are not doctrines.[105][106][107][108] Pope John Paul II's 1987 encyclical Redemptoris Mater began with the sentence: "The Mother of the Redeemer has a precise place in the plan of salvation."[109]

In the 20th century both popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI have emphasized the Marian focus of the church. Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) wrote:

It is necessary to go back to Mary if we want to return to that "truth about Jesus Christ," "truth about the Church" and "truth about man".[110]

when he suggested a redirection of the whole Church towards the program of Pope John Paul II in order to ensure an authentic approach to Christology via a return to the "whole truth about Mary".[110]

Islamic perspective

Mary, the mother of Jesus, is mentioned as Maryam, more in the Qur'an than in the entire New Testament.[111][112] She enjoys a singularly distinguished and honored position among women in the Qur'an. A chapter in the Qur'an is titled "Maryam" (Mary), which is the only chapter in the Qur'an named after a woman, in which the story of Mary (Maryam) and Jesus(Isa) is recounted according to the Islamic view of Jesus.[113]

Mary is mentioned in the Qur'an with the honorific title of "our lady" (syyidatuna) as the daughter of Imran and Hannah.[114]

She is the only woman directly named in the Qur'an; declared (uniquely along with Jesus) to be a Sign of God to mankind [Quran 23:50]; as one who "guarded her chastity" [Quran 66:12]; an obedient one [Quran 66:12]; chosen of her mother and dedicated to God whilst still in the womb [Quran 3:36]; uniquely (amongst women) Accepted into service by Allah [Quran 3:37]; cared for by (one of the prophets as per Islam) Zakariya (Zacharias) [Quran 3:37]; that in her childhood she resided in the Temple and uniquely had access to Al-Mihrab (understood to be the Holy of Holies), and was provided with heavenly 'provisions' by God [Quran 3:37].[114]

Mary is also called a Chosen One [Quran 3:42]; a Purified One [Quran 3:42]; a Truthful one [Quran 5:75]; her child conceived through "a Word from God" [Quran 3:45]; and "exalted above all women of The Worlds/Universes" [Quran 3:42].

The Qur'an relates detailed narrative accounts of Maryam (Mary) in two places Sura 3[Quran 3:35] and Sura 19[Quran 19:16]. These state beliefs in both the Immaculate Conception of Mary and the Virgin birth of Jesus.[115][116] [117] The account given in Sura 19 [Quran 19:1] of the Qur'an is nearly identical with that in the Gospel according to Luke, and both of these (Luke, Sura 19) begin with an account of the visitation of an angel upon Zakariya (Zecharias) and Good News of the birth of Yahya (John), followed by the account of the annunciation. It mentions how Mary was informed by an angel that she would become the mother of Jesus through the actions of God alone.[118]

In the Islamic tradition, Mary and Jesus were the only children who could not be touched by Satan at the moment of their birth, for God imposed a veil between them and Satan.[119] According to author Shabbir Akhtar, the Islamic perspective on Mary's Immaculate Conception is compatible with the Catholic doctrine of the same topic.[120][121]

The Qur'an says that Jesus was the result of a virgin birth. The most detailed account of the annunciation and birth of Jesus is provided in Sura 3 and 19 of The Qur'an wherein it is written that God sent an angel to announce that she could shortly expect to bear a son, despite being a virgin.[122]

Latter Day Saint view

Latter Day Saints affirm the virgin birth[123] but reject the traditions of the Immaculate Conception, Mary's perpetual virginity, and her assumption.[124] The Book of Mormon, part of the Latter Day Saint canon of scripture, refers to Mary by name in prophecies of her mission,[125] and describes her as "most beautiful and fair above all other virgins,"[126] and as a "precious and chosen vessel."[127]

In the first edition of the Book of Mormon (1830), Mary was referred to as "the mother of God, after the manner of the flesh,"[128] a reading that was changed to "the mother of the Son of God" in all subsequent editions (1837–).[129]

Latter Day Saints also believe that God the Father, not the Holy Spirit, is the literal father of Jesus Christ,[130] although how Jesus' conception was accomplished has not been authoritatively established.

Lutheran view

Despite Martin Luther's harsh polemics against his Roman Catholic opponents over issues concerning Mary and the saints, theologians appear to agree that Luther adhered to the Marian decrees of the ecumenical councils and dogmas of the church. He held fast to the belief that Mary was a perpetual virgin and the Theotokos or Mother of God.[131][132] Special attention is given to the assertion, that Luther some three-hundred years before the dogmatization of the Immaculate Conception by Pope Pius IX in 1854, was a firm adherent of that view. Others maintain that Luther in later years changed his position on the Immaculate Conception, which, at that time was undefined in the Church, maintaining however the sinlessness of Mary throughout her life.[133][134] For Luther, early in his life, the Assumption of Mary was an understood fact, although he later stated that the Bible did not say anything about it and stopped celebrating its feast. Important to him was the belief that Mary and the saints do live on after death.[135][136][137]"Throughout his career as a priest-professor-reformer, Luther preached, taught, and argued about the veneration of Mary with a verbosity that ranged from childlike piety to sophisticated polemics. His views are intimately linked to his Christocentric theology and its consequences for liturgy and piety."[138] Luther, while revering Mary, came to criticize the "Papists" for blurring the line, between high admiration of the grace of God wherever it is seen in a human being, and religious service given to another creature. He considered the Roman Catholic practice of celebrating saints' days and making intercessory requests addressed especially to Mary and other departed saints to be idolatry.[139]

Orthodox view

Orthodox Christianity includes a large number of traditions regarding the Ever Virgin Mary, the Theotokos.[140] The Orthodox believe that she was and remained a virgin before and after Christ's birth.[38]

The views of the Church Fathers still play an important role in the shaping of Orthodox Marian perspective. However, the Orthodox views on Mary are mostly doxological, rather than academic: they are expressed in hymns, praise, liturgical poetry and the veneration of icons. One of the most loved Orthodox Akathists (i.e. hymns) is devoted to Mary and it is often simply called the Akathist Hymn.[141] Five of the twelve Great Feasts in Orthodoxy are dedicated to Mary.[38] The Sunday of Orthodoxy directly links the Virgin Mary's identity as Mother of God with icon veneration.[142]

The Orthodox view Mary as "superior to all created beings", although not divine.[39] The Orthodox venerate Mary as conceived immaculate and assumed into heaven, but they do not accept the Roman Catholic dogmas on these doctrines.[143] The Orthodox celebrate the Dormition of the Theotokos, rather than Assumption.[38]

The apocryphal Protoevangelium of James, which is not part of Scripture, has been the source of many Orthodox beliefs on Mary. The account of Mary's life presented includes her consecration as a virgin at the temple at age three. The High Priest Zachariah blessed Mary and informed her that God had magnified her name among many generations. Zachariah placed Mary on the third step of the altar, whereby God gave her grace. While in the temple, Mary was miraculously fed by an angel, until she was twelve years old. At that point an angel told Zachariah to betroth Mary to a widower in Isreal, who would be indicated. This story provides the theme of many hymns for the Feast of Presentation of Mary, and icons of the feast depict the story.[25] The Orthodox believe that Mary was instrumental in the growth of Christianity during the life of Jesus, and after his Crucifixion, and Orthodox Theologian Sergei Bulgakov wrote: "The Virgin Mary is the center, invisible, but real, of the Apostolic Church"

Theologians from the Orthodox tradition have made prominent contributions to the development of Marian thought and devotion. John Damascene (c 650─c 750) was one of the greatest Orthodox theologians. Among other Marian writings, he proclaimed the essential nature of Mary's heavenly Assumption or Dormition and her mediative role.

It was necessary that the body of the one who preserved her virginity intact in giving birth should also be kept incorrupt after death. It was necessary that she, who carried the Creator in her womb when he was a baby, should dwell among the tabernacles of heaven.[144]

From her we have harvested the grape of life; from her we have cultivated the seed of immortality. For our sake she became Mediatrix of all blessings; in her God became man, and man became God.[145]

More recently, Sergei Bulgakov expressed the Orthodox sentiments towards Mary as follows:[39]

Mary is not merely the instrument, but the direct positive condition of the Incarnation, its human aspect. Christ could not have been incarnate by some mechanical process, violating human nature. It was necessary for that nature itself to say for itself, by the mouth of the most pure human being: "Behold the handmaid of the Lord, be it unto me according to Thy word."

Protestant view

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Protestants in general reject the veneration and invocation of the Saints.[67]: p.1174 Protestants typically hold that Mary was the mother of Jesus, but was an ordinary woman devoted to God. Therefore, there is virtually no Marian veneration, Marian feasts, Marian pilgrimages, Marian art, Marian music or Marian spirituality in today's Protestant communities. Within these views, Roman Catholic beliefs and practices are at times rejected, e.g., theologian Karl Barth wrote that "the heresy of the Catholic Church is its Mariology".[146]

Some early Protestants venerated and honored Mary. Martin Luther wrote that: "Mary is full of grace, proclaimed to be entirely without sin. God's grace fills her with everything good and makes her devoid of all evil".[147] However, as of 1532 Luther stopped celebrating the feast of the Assumption of Mary and also discontinued his support of the Immaculate Conception.[148]

John Calvin said, "It cannot be denied that God in choosing and destining Mary to be the Mother of his Son, granted her the highest honor."[149] However, Calvin firmly rejected the notion that anyone but Christ can intercede for man.[150]

Although Calvin and Huldrych Zwingli honored Mary as the Mother of God in the 16th century, they did so less than Martin Luther.[151] Thus the idea of respect and high honor for Mary was not rejected by the first Protestants; but, they came to criticize the Roman Catholics for venerating Mary. Following the Council of Trent in the 16th century, as Marian veneration became associated with Catholics, Protestant interest in Mary decreased.[67] During the Age of the Enlightenment and residual interest in Mary within Protestant churches almost disappeared, although Anglicans continued to honor her.[67]

Protestants acknowledge that Mary is "blessed among women"Luke 1:42 but they do not agree that Mary is to be venerated. She is considered to be an outstanding example of a life dedicated to God.[152]

In the 20th century, Protestants reacted in opposition to the Catholic dogma of the Assumption of Mary. The conservative tone of the Second Vatican Council began to mend the ecumenical differences, and Protestants began to show interest in Marian themes. In 1997 and 1998 ecumenical dialogs between Catholics and Protestants took place, but to date the majority of Protestants pay scant attention to Marian issues and often view them as a challenge to the authority of Scripture.[67]

Nontrinitarian view

Nontrinitarians, such as Jehovah's Witnesses, Christadelphians, consider Mary as the mother of Jesus Christ. Because they do not consider Jesus as God, they do not consider Mary as the Mother of God or the Theotokos.[153] They believe that the Christians should pray only to God the Father, not to Mary.[154]

Other views

From the early stages of Christianity, belief in the virginity of Mary and the virgin conception of Jesus, as stated in the gospels, holy and supernatural, was used by detractors, both political and religious, as a topic for discussions, debates and writings, specifically aimed to challenge the divinity of Jesus and thus Christians and Christianity alike.[155] In the second century, as part of the earliest anti-Christian polemics, Celsus suggested that Jesus was the illegitimate son of a Roman soldier named Panthera.[156] The views of Celsus drew responses from Origen, the Church Father in Alexandria, Egypt.[157]

To date, scholars continue to debate the accounts of the birth of Jesus from several perspectives, including textual analysis, historical records and post-apostolic witnesses.[158] Bart D. Ehrman has suggested that the historical method can never comment on the likelihood of supernatural occurrences.[159]

Cinematic portrayals

Mary has been portrayed in various films, including:

- Angela Clarke, The Miracle of Our Lady of Fatima, 1951

- Dorothy McGuire, The Greatest Story Ever Told, 1965

- Keisha Castle-Hughes, The Nativity Story, 2006

- Linda Darnell, The Song of Bernadette, 1943

- Maia Morgenstern, The Passion of the Christ, 2004

- Olivia Hussey, Jesus of Nazareth, 1977

- Penelope Wilton, The Passion, 2008 (TV)

- Pernilla August, Mary, Mother of Jesus, 1999 (TV)

- Shabnam Gholikhani, Saint Mary (Maryam Moghaddas), Iranian director Shahriar Bahrani's "Saint Mary"[160][161]

- Siobhán McKenna, King of Kings, 1961

- Verna Bloom, The Last Temptation of Christ, 1988

Image gallery

- See also: Life of the Virgin

- For a larger gallery, please see: Marian image gallery

-

The oldest-known image of Mary depicts her nursing the Infant Jesus. Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome (2nd century)

-

Adoration of the Magi, Rubens, 1634

-

Old Persian miniature of Madonna and Child

-

Madonna of humility by Fra Angelico, c. 1430.

-

Flight into Egypt by Giotto c. 1304

-

Inside of the Tomb of Mary

-

Outside View ,Tomb of Mary

See also

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Mother of Jesus |

| Chronology |

|---|

|

|

| Marian perspectives |

|

|

| Catholic Mariology |

|

|

| Marian dogmas |

|

|

| Mary in culture |

- Acts of Reparation to the Virgin Mary

- Anglican Marian theology

- Anglican Roman Catholic International Commission

- Black Madonna

- Blessed Virgin Mary (Roman Catholic)

- Christian mythology

- Dormition of the Theotokos

- Fleur de lys

- History of Roman Catholic Mariology

- Hortus conclusus

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Islamic views on Mary

- Alliance of the Hearts of Jesus and Mary

- Litany of the Blessed Virgin Mary

- Marian apparition

- Madonna (art)

- Marian columns

- Marian devotions

- May crowning

- Our Lady of Sorrows

- Panagia

- Protestant views on Mary

- Shrines to the Virgin Mary

- Society of Mary (Marianists)

- Titles of Mary

- Virgin Birth of Jesus

- Virgin Mary in Islam

Reflists

- ^ "Feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary". Newadvent.org. 1911-10-01. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

- ^ The Life of Jesus of Nazareth, By Rush Rhees, (BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2008), page 62

- ^ a b c Mary, Mother of Jesus by Bruce E. Dana 2001 ISBN 1555175570 page 1

- ^ a b c Ruiz, Jean-Pierre. "Between the Crèche and the Cross: Another Look at the Mother of Jesus in the New Testament." New Theology Review; Aug2010, Vol. 23 Issue 3, p3-4 Cite error: The named reference "Ruiz" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Ronald Brownrigg, Canon Brownrigg Who's Who in the New Testament 2001 ISBN 0415260361 page T-62

- ^ Matthew 1:23 uses Greek parthénos virgin, whereas only the Hebrew of Isaiah 7:14, from which the New Testament ostensibly quotes, as Almah young maiden. See article on parthénos in Bauer/(Arndt)/Gingrich/Danker, "A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature", Second Edition, University of Chicago Press, 1979, p. 627.

- ^ Browning, W. R. F. A dictionary of the Bible. 2004 ISBN 019860890X page 246

- ^ Christian belief and practice by Gordon Geddes, Jane Griffiths 2002 ISBN 043530691X page 12

- ^ "Mary, the mother of Jesus." The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Houghton Mifflin. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2002. Credo Reference. Web. 28 September 2010.

- ^ Behind the Name

- ^ Jestice, Phyllis G. Holy people of the world: a cross-cultural encyclopedia, Volume 3. 2004 ISBN 1576073556 page 54

- ^ a b Brown, Raymond Edward. Mary in the New Testament. 1978 ISBN 9780809121687

- ^ Douglas; Hillyer; Bruce (1990). New Bible Dictionary. Inter-varsity Press. p. 746. ISBN 0851106307.

- ^ An event described by Christians as the Annunciation Luke 1:35.

- ^ Mills, Watson E., Roger Aubrey Bullard. Mercer dictionary of the Bible. 1998 ISBN 0865543739 page 429

- ^ The Life of Jesus by Laurie Mandhardt, Laurie Watson Manhardt 2005 ISBN 1931018286 page 28

- ^ Walvoord ,John F., Roy B. Zuck. The Bible Knowledge Commentary: New Testament edition. 1983 ISBN 0882078127

- ^ Gaventa, Beverly Roberts. Mary: glimpses of the mother of Jesus. 1995 ISBN 1570030723, p.70

- ^ de Bles, Arthur. How to Distinguish the Saints in Art by Their Costumes, Symbols and Attributes', 2004 ISBN 141790870X page 35

- ^ Jameson, Anna. Legends of the Madonna: as represented in the fine arts. 2006 ISBN 1428634991 page 37

- ^ De Obitu S. Dominae as noted in; Holweck, F. (1907). The Feast of the Assumption. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b Munificentissimus Deus on the Assumption

- ^ Coptic Church website, Accessed 2010/10/6.

- ^ Ronald Brownrigg, Canon Brownrigg Who's Who in the New Testament 2001 ISBN 0415260361 page T-62

- ^ a b Wybrew, Hugh Orthodox feasts of Jesus Christ & the Virgin Mary: liturgical texts 2000 ISBN 0881412031 pages 37-46

- ^ Taylor, Joan E. Christians and the Holy Places: The Myth of Jewish-Christian Origins, Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 202, ISBN 0198147856 (Google Scholar: [1]).

- ^ Irenaeus, Adversus haereses III,1,1; Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History, III,1

- ^ Catholic encyclopedia

- ^ Baldovin, John and Johnson, Maxwell, Between memory and hope: readings on the liturgical year 2001 ISBN 0814660258 page 386

- ^ Dalmais, Irénée et al. The Church at Prayer: The liturgy and time 1985 ISBN 0814613667 page 130

- ^ McNally, Terrence, What Every Catholic Should Know about Mary ISBN 1441510516 page 186

- ^ Benz, Ernst The Eastern Orthodox Church: Its Thought and Life 2009 ISBN 0202362981 page 62

- ^ Burke, Raymond et al. Mariology: A Guide for Priests, Deacons, Seminarians, and Consecrated Persons 2008 ISBN 9781579183554 page 178

- ^ The encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 3 by Erwin Fahlbusch, Geoffrey William Bromiley 2003 ISBN 9004126546 page 406

- ^ Catholic encyclopedia

- ^ Osborne, John L. "Early Medieval Painting in San Clemente, Rome: The Madonna and Child in the Niche" Gesta 20.2 (1981:299-310) and (note 9) referencing T. Klauser, "Rom under der Kult des Gottesmutter Maria", Jahrbuch für der Antike und Christentum 15 (1972:120-135).

- ^ Vatican website

- ^ a b c d e f Eastern Orthodoxy through Western eyes by Donald Fairbairn 2002 ISBN 0664224970 page 99-101

- ^ a b c d The Orthodox Church by Serge? Nikolaevich Bulgakov 1997 ISBN 0881410519 page 116

- ^ Miravalle, Mark. Introduction to Mary'’. 1993 Queenship Publishing ISBN 9781882972067 pages 92-93

- ^ The Orthodox word, Volumes 12-13, 1976 page 73

- ^ Trigilio, John and Brighenti, Kenneth The Catholicism Answer Book 2007 ISBN 1402208065 page 58

- ^ The History of the Christian Church by Philip Smith 2009 ISBN 1150722452 page 288

- ^ The Celebration of Faith: The Virgin Mary by Alexander Schmemann 2001 ISBN 0881411418 page 11 [2]

- ^ De Sherbinin, Julie Chekhov and Russian religious culture: the poetics of the Marian paradigm 1997 ISBN 0810114046 page 15 [3]

- ^ Pope John Paul II, General Audience, 1997

- ^ Kilmartin Edward The Eucharist in the West 1998 ISBN 0814662048 page 80

- ^ Ciaravino, Helene How to Pray 2001 ISBN 0757000126 page 118

- ^ Williams, Rowan Ponder these things: praying with icons of the Virgin 2002 ISBN 185311362X page 7

- ^ a b c d e f g Schroedel, Jenny The Everything Mary Book, 2006 ISBN 1593377134 pages 81-85

- ^ Encyclopedia of Catholicism by Frank K. Flinn, J. Gordon Melton 2007 ISBN 081605455X pages 443-444

- ^ a b c d Hillerbrand, Hans Joachim. Encyclopedia of Protestantism, Volume 3 2003. ISBN 0415924723 page 1174

- ^ a b The Canons of the Two Hundred Holy and Blessed Fathers Who Met at Ephesus

- ^ M'Corry, John StewartTheotokos: Or, the Divine Maternity. 2009 ISBN 1113183616 page 10

- ^ The Christian theology reader by Alister E. McGrath 2006 ISBN 140515358X page 273

- ^ What Every Catholic Should Know about Mary by Terrence J. McNally ISBN 1441510516 page 128

- ^ Legends of the Madonna by Anna Jameson 2009 1406853380 page 50

- ^ Ann Ball, 2003 Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices ISBN 087973910X page 515

- ^ Candice Lee Goucher, 2007 World history: journeys from past to present ISBN 0-415-77137-4 page 102

- ^ Ann Ball, 2003 Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices ISBN 087973910X page 525

- ^ a b c d Flinn, Frank K., J. Gordon MeltonEncyclopedia of Catholicism. 2007 ISBN 081605455X pages 443-444

- ^ a b Clayton, Mary. The Cult of the Virgin Mary in Anglo-Saxon England. 2003 ISBN 0521531152 pages 26-37

- ^ EWTN on Battle of Lepanto (1571) [4]

- ^ by Butler, Alban, Peter Doyle. Butler's Lives of the Saints. 1999 ISBN 0860122530 page 222

- ^ Jackson, Gregory Lee, Catholic, Lutheran, Protestant: a doctrinal comparison. 1993 ISBN 9780615166353 page 254

- ^ Jackson, Gregory Lee.Catholic, Lutheran, Protestant: a doctrinal comparison. 1993 ISBN 9780615166353 page 254

- ^ a b c d e Encyclopedia of Protestantism, Volume 3 2003 by Hans Joachim Hillerbrand ISBN 0415924723 page 1174 [5]

- ^ Miravalle, Mark. Introduction to Mary'’. 1993 Queenship Publishing ISBN 9781882972067 page 51

- ^ Camille Fronk, "Mary, Mother of Jesus," Encyclopedia of Mormonism (New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1992), 2:863–64.

- ^ Doctrinal Insights to the Book of Mormon by Doug Bassett 2007 ISBN 1599550512 page 49

- ^ Miravalle, Mark Introduction to Mary, 1993, ISBN 9781882972067, pages 44-46

- ^ "Virgin Birth" britannica.com'.' Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- ^ Translation by the ecumenical English Language Liturgical Consultation, given on page 17 of Praying Together, a literal translation of the original, "σαρκωθέντα ἐκ Πνεύματος Ἁγίου καὶ Μαρίας τῆς Παρθένου"

- ^ a b Miravalle, Mark Introduction to Mary, 1993, ISBN 9781882972067, pages 56-64

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church §499

- ^ a b c Fahlbusch, Erwin, et al. The encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 3 2003 ISBN 9004126546 pages 403-409

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Immaculate Conception". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

- ^ Ware, Timothy. The Orthodox Church (Penguin Books, 1963, ISBN 0-14-020592-6), pp. 263–4.

- ^ Pope Pius XII: "Munificentissimus Deus─Defining the Dogma of the Assumption", par. 44. Vatican, November 1, 1950

- ^ Milton, Anthony Catholic and Reformed 2002 ISBN 0521893291 page 5

- ^ a b Braaten, Carl, et al. Mary, Mother of God 2004 ISBN 0802822665 page 13

- ^ Burnham, Andrew A Pocket Manual of Anglo-Catholic Devotion 2004 ISBN 1853115304 pages 1, 266,310, 330

- ^ Duckworth, Penelope, Mary: The Imagination of Her Heart 2004 ISBN 1561012602 page 3-5

- ^ Church of england yearbook: Volume 123 2006 ISBN 0715110209 page 315

- ^ Perrier, Jacques, Lourdes Today and Tomorrow 2008 1565483057 ISBN page 56

- ^ Mary: grace and hope in Christ: the Seattle statement of the Anglican-Roman Catholics" by the Anglican/Roman Catholic International Group 2006 ISBN 0826481558 pages 7-10

- ^ Camiz , Franca Trinchieri, Katherine A. McIver. Art and music in the early modern period. ISBN 0754606899 page 15

- ^ Miegge, Giovannie, The Virgin Mary: Roman Catholic Marian Doctrine, pgs. 15-22, Westminister Press, Philadelpia, 1963.

- ^ "Item 971 - Devotion to the Blessed Mary". Catechism of the Catholic Church. Vatican. Retrieved 01 Oct 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Merriam-Webster's encyclopedia of world religions by Wendy Doniger, 1999 ISBN 0877790442 page 696

- ^ "Encyclical Ad Caeli Reginam". Vatican.

- ^ Schroede, Jenny, The Everything Mary Book 2006 ISBN 1593377134 page 219

- ^ O'Carroll, Michael, The Alliance of the Hearts of Jesus and Mary 2007, ISBN 1-882972-98-8 pages 10-15

- ^ Catholic encyclopedia

- ^ Zenit News 2008 Cardinal Urges Devotion to Rosary and Scapular

- ^ Handbook of Prayers by James Socías 2006 ISBN 0879735791 page 483

- ^ The encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 4 by Erwin Fahlbusch, Geoffrey William Bromiley 2005 ISBN 0802824161 page 575

- ^ Pope Leo XIII. "Encyclical of Pope Leo XIII on the Rosary". Octobri Mense. Vatican. Retrieved 04 Oct 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Cateechism at the Vatican website

- ^ A Beginner's Book of Prayer: An Introduction to Traditional Catholic Prayers by William G. Storey 2009 ISBN 0829427929 page 99

- ^ Ann Ball, 2003 Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices ISBN 087973910X page 365

- ^ Our Sunday Visitor's Catholic Almanac by Matthew Bunson 2009 ISBN 159276441X page 122

- ^ The Catholic Handbook for Visiting the Sick and Homebound by Corinna Laughlin, Sara McGinnis Lee 2010 ISBN 9781568548869 page 4

- ^ Geoghegan. G.P. A Collection of My Favorite Prayers, 2006 ISBN 1411694570 pages 31, 45, 70, 86, 127

- ^ Mary, mother of the redemption by Edward Schillebeeckx 1964 ASIN B003KW30VG pages 82-84

- ^ Mary in the Redemption by Adrienne von Speyr 2003 ISBN 0898709555 pages 2-7

- ^ Salvation Through Mary by Henry Aloysius Barry 2008 ISBN 1409731723 pages 13-15

- ^ The mystery of Mary by Paul Haffner 2004 ISBN 0852446500 page 198

- ^ Redemptoris Mater at the Vatican website

- ^ a b Burke, Raymond L.; et al. (2008). Mariology: A Guide for Priests, Deacons, Seminarians, and Consecrated Persons ISBN 9781579183554 page xxi

- ^ "Mary and Angels". Readingislam.com. 2002-09-01. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

- ^ Alaharasan, V. Antony John.Home of the Assumption: Reconstructing Mary's Life in Ephesus. 2006 ISBN 1929039387 page 66

- ^ Jestice, Phyllis G. Holy people of the world: a cross-cultural encyclopedia, Volume 3. 2004 ISBN 1576073556 page 558 [6]

- ^ a b The new encyclopedia of Islam by Cyril Glassé, Huston Smith 2003 ISBN 0759101906 page 296 [7]

- ^ Jomier, Jacques. The Bible and the Qur'an. 2002 ISBN 0898709288 page 133

- ^ Nazir-Ali, Michael. Islam, a Christian perspective. 1984 ISBN 0664245277 page 110

- ^ EWTN

- ^ Jackson, Montell. Islam Revealed. 2003 ISBN 1591608694 page 73

- ^ Rodwell, J. M. The Koran. 2009 ISBN 0559131275 page 505

- ^ Akhtar, Shabbir.The Quran and the secular mind: a philosophy of Islam. 2007 page 352

- ^ Glassé, Cyril, Huston Smith. The new encyclopedia of Islam. 2003 ISBN 0759101906 page 240

- ^ Sarker, Abraham.Understand My Muslim People. 2004 ISBN 1594980020 page 260 [8]

- ^ Eleanor Colton, "Virgin Birth," Encyclopedia of Mormonism (New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1992), 4:1510.

- ^ Camille Fronk, "Mary, Mother of Jesus," Encyclopedia of Mormonism (New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1992), 2:863–64.

- ^ Mosiah 3:8

- ^ 1 Nephi 11:13-20

- ^ Alma 7:10

- ^ The Book of Mormon (Palmyra, NY: E.B. Grandin, 1830), 25.

- ^ 1 Nephi 11:18. Latter Day Saint author Hugh Nibley has argued that the change was made to "avoid confusion, since during the theological controversies of the early Middle Ages the expression "mother of God" took on a special connotation which it still has for many Christians"; Since Cumorah, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 6.

- ^ Gospel Principles (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2009), 52–53.

- ^ Bäumer, Remigius. Marienlexikon Gesamtausgabe, Leo Scheffczyk, ed., (Regensburg: Institutum Marianum, 1994), 190.

- ^ The Everything Mary Book by Jenny Schroedel 2006 ISBN 1593377134 pages 125-126

- ^ Jackson, Gregory Lee. Catholic, Lutheran, Protestant: a doctrinal comparison. 1993 ISBN 9780615166353 page 249

- ^ Bäumer, 191

- ^ Haffner, Paul.The mystery of Mary’’. 2004 ISBN 0852446500 page 223

- ^ Bäumer, 190.

- ^ Colonna, Vittoria, Susan Haskins, Chiara Matraini. Who Is Mary? 2009 ISBN 0226114007 page 34

- ^ Eric W. Gritsch (1992). H. George Anderson, J. Francis Stafford, Joseph A. Burgess (eds.) (ed.). The One Mediator, The Saints, and Mary, Lutherans and Roman Catholic in Dialogue. Vol. VII. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress. p. 235.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Luther's Works, 47, pp. 45f; see also, Lutherans and Catholics in Dialogue VIII, p. 29.

- ^ McNally, Terrence, What Every Catholic Should Know about Mary ISBN 1441510516 pages 168-169

- ^ The Everything Mary Book by Jenny Schroedel 2006 ISBN 1593377134 page 90

- ^ Vasilaka, Maria Images of the Mother of God: perceptions of the Theotokos in Byzantium 2005 ISBN 0754636038 page 97

- ^ Fahlbusch, Erwin, et al. The encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 3 2003 ISBN 9004126546 pages 403-409 [9]

- ^ Damascene, John. Homily 2 on the Dormition 14; PG 96, 741 B

- ^ Damascene, John. Homily 2 on the Dormition 16; PG 96, 744 D

- ^ Barth Karl. Church dogmatics, Volume 1. ISBN 0567050696 pages 143-144

- ^ Lehmann, H., ed. ‘’Luther's Works, American edition,’’ vol. 43, p. 40, Fortress, 1968

- ^ Jackson, Gregory Lee. Catholic, Lutheran, Protestant: a doctrinal comparison. 1993 ISBN 9780615166353 page 249

- ^ EWTN

- ^ McKim, Donald K. The Cambridge companion to John Calvin. 2004 ISBN 052101672X page

- ^ Haffner, Paul. The mystery of Mary. 2004 ISBN 0852446500 page 11

- ^ Geisler, Norman L., Ralph E. MacKenzie Roman Catholics and Evangelicals: agreements and differences. 1995 ISBN 0801038758 page 143

- ^ Myth 5: Mary Is the Mother of God

- ^ Should You Pray to the Virgin Mary?

- ^ Bennett, Clinton, In search of Jesus 2001 ISBN 0826449166 pages 165-170

- ^ Also see: Schaberg, Jane. Illegitimacy of Jesus: A Feminist Theological Interpretation of the Infancy Narratives (Biblical Seminar Series, No 28), ISBN 1-85075-533-7.

- ^ Patrick, John The Apology of Origen in Reply to Celsus 2009 ISBN 111013388X pages 22-24

- ^ Bromiley, Geoffrey W. The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Q-Z 1995 ISBN 0802837840 pages 990-991

- ^ Ehrman, Bart (March 28, 2006). "William Lane Craig and Bart Ehrman "Is There Historical Evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus?"". College of the Holy Cross, Worcester, Massachusetts: bringyou.to. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

Historians can only establish what probably happened in the past, and by definition a miracle is the least probable occurrence. And so, by the very nature of the canons of historical research, we can't claim historically that a miracle probably happened. By definition, it probably didn't. And history can only establish what probably did.

{{cite web}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2007/aug/18/religion.news featured in ITV documentary

- ^ "The Muslim Jesus, ITV─Unreality Primetime". Primetime.unrealitytv.co.uk. 2007-08-18. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

Bibliography

- Brownson, Orestes, Saint Worship and the Worship of Mary, Sophia Institute Press, 2003, ISBN 1-928832-88-1

- Corner, Dan. Is This The Mary Of The Bible?, Evangelical Outreach, 2004, 249 pages ISBN 0-96390-767-0

- Cronin, Vincent, Mary Portrayed, London: Darton, Longman & Todd, Ltd., 1968, ISBN 0-87505-213-4

- Epie, Chantal. The Scriptural Roots of Catholic Teaching, Sophia Institute Press, 2002, ISBN 1-928832-53-9

- Fox, Fr. Robert J., Catechism on Mary, Immaculate Heart of Mary, Mary Through the Ages Fatima Family Apostolate

- Glavich, Mary Kathleen, The Catholic Companion to Mary, ACTA Publications, 2007

- Graef, Hilda. Mary: A History of Doctrine and Devotion, London: Sheed & Ward, 1985, ISBN 0-7220-5221-9

- Groeschel, Benedict, A Still, Small Voice: A Practical Guide on Reported Revelations, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1993 ISBN 0-8987-0436-7

- Hahn, Scott, Hail, Holy Queen: The Mother of God in the Word of God, Doubleday, 2001, ISBN 0-3855-0168-4

- Marley, Stephen, The Life of the Virgin Mary, Lennard Publishing, 1990, ISBN 1852910240

- Mills, David. Discovering Mary: Answers to Questions About the Mother of God, Servant Books, 2009, ISBN 0-8671-6927-3

- Miravalle, Mark. Introduction to Mary, Queenship Publishing, 1993, Second Edition 2006, soft, 220 pages ISBN 1-882972-06-6

- Newman, Barbara. God and the Goddesses, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003, ISBN 0812219112

- Pelikan, Jaroslav. Mary Through the Centuries: Her Place in the History of Culture, Yale University Press, 1998, hardcover, 240 pages ISBN 0-300-06951-0; trade paperback, 1998, 240 pages, ISBN 0-300-07661-4

External links

- Articles to be merged from September 2010

- Mary (mother of Jesus)

- 1st-century BC births

- 1st-century Christian female saints

- 1st-century deaths

- Coptic Orthodox saints

- Oriental Orthodox saints

- Eastern Orthodox saints

- Followers of Jesus

- Jesus

- Palestinian Roman Catholic saints

- Prophets in Christianity

- Roman Catholic saints

- People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar

- Roman era Jews

- Saints from the Holy Land

- Anglican saints