History of Poland: Difference between revisions

bit of an exaggeration, source relates to previous sentence |

Still "puffy". No one really disputes Poland's place in Europe. Also: CE |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Aspect of history}} |

{{short description|Aspect of history}} |

||

{{History of Poland}} |

{{History of Poland}} |

||

The '''history of [[Poland]]''' ({{lang-pl|Historia Polski}}) |

The '''history of [[Poland]]''' ({{lang-pl|Historia Polski}}) spans a thousand years, from [[Lechites|ancient tribes]], [[Baptism of Poland|Catholic baptism]], [[Kingdom of Poland|rule of kings]], [[Polish Golden Age|cultural prosperity]], [[Polonization|expansionism]] and becoming one of the largest [[Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth|European powers]], to its [[Partitions of Poland|collapse and partitions]], [[World War I]], [[World War II]], [[Polish People's Republic|communism]] and restoration of [[democracy]]. |

||

The roots of Polish history |

The roots of Polish history can be traced to the [[Iron Age]], when the territory of present-day Poland was settled by various tribes including [[Celts]], [[Scythians]], [[Germanic peoples|Germanic clans]], [[Sarmatians]], [[Slavs]] and [[Balts]]. However, it was the [[West Slavs|West Slavic]] ''[[Lechites]]'', the closest ancestors of ethnic [[Poles]], who established permanent settlements in the [[geography of Poland|Polish lands]] during the [[Early Middle Ages]].<ref name="UzP 122-143">{{Harvnb|Derwich|Żurek|2002|pp=122–143}}.</ref> The Lechitic [[Polans (western)|Western Polans]], a tribe whose name means "people living in open fields", dominated the region, and gave Poland - which lies in the [[North European Plain|North-Central European Plain]] - its [[Name of Poland|name]]. |

||

The first ruling dynasty, the [[Piast dynasty|Piasts]], emerged in the 10th century AD. Duke [[Mieszko I of Poland|Mieszko I]] is considered the ''de facto'' creator of the Polish state and is widely recognized for |

The first ruling dynasty, the [[Piast dynasty|Piasts]], emerged in the 10th century AD. Duke [[Mieszko I of Poland|Mieszko I]] is considered the ''de facto'' creator of the Polish state and is widely recognized for his [[Christianization of Poland|adoption of Western Christianity]] in 966 CE. Mieszko's dominion was formally reconstituted as a [[High Middle Ages|medieval]] kingdom in 1025 by his son [[Bolesław I the Brave]], known for military expansion under his rule. The most successful and the last Piast monarch, [[Casimir III the Great]], presided over a period of economic prosperity and territorial aggrandizement before his death in 1370 without male heirs. The period of the [[Jagiellonian dynasty]] in the 14th–16th centuries brought close ties with the [[Grand Duchy of Lithuania|Lithuania]], a cultural [[Renaissance in Poland]] and continued territorial expansion as well as [[Polonization]] that culminated in the establishment of the [[Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth]] in 1569, one of Europe's largest countries. |

||

The Commonwealth was able to sustain the levels of prosperity achieved during the Jagiellonian period, while its political system matured as a unique [[Golden Liberty|noble democracy]] with an [[elective monarchy]]. From the mid-17th century, however, the huge state entered a period of decline caused by devastating wars and the deterioration of its political system. Significant internal reforms were introduced in the late 18th century, such as Europe's first [[Constitution of 3 May 1791]], but neighboring powers did not allow the reforms to advance. The existence of the Commonwealth ended in 1795 after a series of invasions and [[partitions of Poland|partitions of Polish territory]] carried out by the [[Russian Empire]] in the east, the [[Kingdom of Prussia]] in the west and the [[Habsburg Monarchy]] in the south. From 1795 until 1918, no truly independent Polish state existed, although strong [[Resistance movements in partitioned Poland (1795–1918)|Polish resistance movements]] operated. The opportunity to regain sovereignty only materialized after [[World War I]], when the three partitioning imperial powers were fatally weakened in the wake of war and revolution. |

The Commonwealth was able to sustain the levels of prosperity achieved during the Jagiellonian period, while its political system matured as a unique [[Golden Liberty|noble democracy]] with an [[elective monarchy]]. From the mid-17th century, however, the huge state entered a period of decline caused by devastating wars and the deterioration of its political system. Significant internal reforms were introduced in the late 18th century, such as Europe's first [[Constitution of 3 May 1791]], but neighboring powers did not allow the reforms to advance. The existence of the Commonwealth ended in 1795 after a series of invasions and [[partitions of Poland|partitions of Polish territory]] carried out by the [[Russian Empire]] in the east, the [[Kingdom of Prussia]] in the west and the [[Habsburg Monarchy]] in the south. From 1795 until 1918, no truly independent Polish state existed, although strong [[Resistance movements in partitioned Poland (1795–1918)|Polish resistance movements]] operated. The opportunity to regain sovereignty only materialized after [[World War I]], when the three partitioning imperial powers were fatally weakened in the wake of war and revolution. |

||

Revision as of 12:02, 21 June 2020

| History of Poland |

|---|

|

The history of Poland (Template:Lang-pl) spans a thousand years, from ancient tribes, Catholic baptism, rule of kings, cultural prosperity, expansionism and becoming one of the largest European powers, to its collapse and partitions, World War I, World War II, communism and restoration of democracy.

The roots of Polish history can be traced to the Iron Age, when the territory of present-day Poland was settled by various tribes including Celts, Scythians, Germanic clans, Sarmatians, Slavs and Balts. However, it was the West Slavic Lechites, the closest ancestors of ethnic Poles, who established permanent settlements in the Polish lands during the Early Middle Ages.[1] The Lechitic Western Polans, a tribe whose name means "people living in open fields", dominated the region, and gave Poland - which lies in the North-Central European Plain - its name.

The first ruling dynasty, the Piasts, emerged in the 10th century AD. Duke Mieszko I is considered the de facto creator of the Polish state and is widely recognized for his adoption of Western Christianity in 966 CE. Mieszko's dominion was formally reconstituted as a medieval kingdom in 1025 by his son Bolesław I the Brave, known for military expansion under his rule. The most successful and the last Piast monarch, Casimir III the Great, presided over a period of economic prosperity and territorial aggrandizement before his death in 1370 without male heirs. The period of the Jagiellonian dynasty in the 14th–16th centuries brought close ties with the Lithuania, a cultural Renaissance in Poland and continued territorial expansion as well as Polonization that culminated in the establishment of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569, one of Europe's largest countries.

The Commonwealth was able to sustain the levels of prosperity achieved during the Jagiellonian period, while its political system matured as a unique noble democracy with an elective monarchy. From the mid-17th century, however, the huge state entered a period of decline caused by devastating wars and the deterioration of its political system. Significant internal reforms were introduced in the late 18th century, such as Europe's first Constitution of 3 May 1791, but neighboring powers did not allow the reforms to advance. The existence of the Commonwealth ended in 1795 after a series of invasions and partitions of Polish territory carried out by the Russian Empire in the east, the Kingdom of Prussia in the west and the Habsburg Monarchy in the south. From 1795 until 1918, no truly independent Polish state existed, although strong Polish resistance movements operated. The opportunity to regain sovereignty only materialized after World War I, when the three partitioning imperial powers were fatally weakened in the wake of war and revolution.

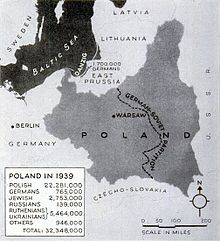

The Second Polish Republic was established in 1918 and existed as an independent state until 1939, when Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union invaded Poland, marking the beginning of World War II. Millions of Polish citizens of different faiths or identities perished in the course of the Nazi occupation of Poland between 1939 and 1945 through planned genocide and extermination. A Polish government-in-exile nonetheless functioned throughout the war and the Poles contributed to the Allied victory through participation in military campaigns on both the eastern and western fronts. The westward advances of the Soviet Red Army in 1944 and 1945 compelled Nazi Germany's forces to retreat from Poland, which led to the establishment of a satellite communist country, known from 1952 as the Polish People's Republic.

As a result of territorial adjustments mandated by the Allies at the end of World War II in 1945, Poland's geographic centre of gravity shifted towards the west and the re-defined Polish lands largely lost their historic multi-ethnic character through the extermination, expulsion and migration of various ethnic groups during and after the war. By the late 1980s, the Polish reform movement Solidarity became crucial in bringing about a peaceful transition from a communist state to a capitalist economic system and a liberal parliamentary democracy. This process resulted in the creation of the modern Polish state, the Third Polish Republic, founded in 1989.

Prehistory and protohistory

In prehistoric and protohistoric times, over a period of at least 600,000 years,[2][better source needed] the area of present-day Poland was intermittently inhabited by members of the genus Homo. It went through the Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age stages of development, along with the nearby regions.[3] The Neolithic period ushered in the Linear Pottery culture, whose founders migrated from the Danube River area beginning about 5500 BC. This culture was distinguished by the establishment of the first settled agricultural communities in modern Polish territory. Later, between about 4400 and 2000 BC, the native post-Mesolithic populations would also adopt and further develop the agricultural way of life.[4]

Poland's Early Bronze Age began around 2400–2300 BC, whereas its Iron Age commenced c. 750–700 BC. One of the many cultures that have been uncovered, the Lusatian culture, spanned the Bronze and Iron Ages and left notable settlement sites.[5] Around 400 BC, Poland was settled by Celts of the La Tène culture. They were soon followed by emerging cultures with a strong Germanic component, influenced first by the Celts and then by the Roman Empire. The Germanic peoples migrated out of the area by about 500 AD during the great Migration Period of the European Dark Ages. Wooded regions to the north and east were settled by Balts.[6]

According to mainstream archaeological research, Slavs have resided in modern Polish territories for only 1,500 years.[1] However, recent genetic studies determined that people who live in the current territory of Poland include the descendants of the people who inhabited the area for thousands of years, beginning in the early Neolithic period.[7]

The West Slavic and Lechitic peoples as well as any remaining minority clans on ancient Polish lands were organized into tribal units, of which the larger ones were later known as the Polish tribes; the names of many tribes are found on the list compiled by the anonymous Bavarian Geographer in the 9th century.[8] In the 9th and 10th centuries, these tribes gave rise to developed regions along the upper Vistula, the coast of the Baltic Sea and in Greater Poland. The latest tribal undertaking, in Greater Poland, resulted in the formation of a lasting political structure in the 10th century that became the state of Poland.[1][x]

Piast period (10th century–1385)

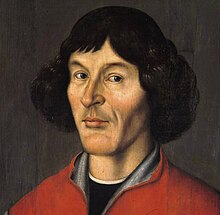

Mieszko I

Poland was established as a state under the Piast dynasty, which ruled the country between the 10th and 14th centuries. Historical records referring to the Polish state begin with the rule of Duke Mieszko I. Mieszko, whose reign commenced sometime before 963 and who continued as the Polish monarch until his death in 992, chose to be baptized in the Western Latin Rite, probably on 14 April 966, following his marriage to Princess Doubravka of Bohemia, a fervent Christian.[9] This event has become known as the baptism of Poland, and its date is often used to mark a symbolic beginning of Polish statehood.[10] Mieszko completed a unification of the Lechitic tribal lands that was fundamental to the new country's existence. Following its emergence, Poland was led by a series of rulers who converted the population to Christianity, created a strong kingdom and fostered a distinctive Polish culture that was integrated into the broader European culture.[11]

Bolesław I the Brave

Mieszko's son, Duke Bolesław I the Brave (r. 992–1025), established a Polish Church structure, pursued territorial conquests and was officially crowned the first king of Poland in 1025, near the end of his life.[9] Bolesław also sought to spread Christianity to parts of eastern Europe that remained pagan, but suffered a setback when his greatest missionary, Adalbert of Prague, was killed in Prussia in 997.[9] During the Congress of Gniezno in the year 1000, Holy Roman Emperor Otto III recognized the Archbishopric of Gniezno,[9] an institution crucial for the continuing existence of the sovereign Polish state.[9] During the reign of Otto's successor, Holy Roman Emperor Henry II, Bolesław fought prolonged wars with the Kingdom of Germany between 1002 and 1018.[9][12]

Piast monarchy under Casimir I, Bolesław II and Bolesław III

Bolesław I's expansive rule overstretched the resources of the early Polish state, and it was followed by a collapse of the monarchy. Recovery took place under Casimir I the Restorer (r. 1039–58). Casimir's son Bolesław II the Generous (r. 1058–79) became involved in a conflict with Bishop Stanislaus of Szczepanów that ultimately caused his downfall. Bolesław had the bishop murdered in 1079 after being excommunicated by the Polish church on charges of adultery. This act sparked a revolt of Polish nobles that led to Bolesław's deposition and expulsion from the country.[9] Around 1116, Gallus Anonymus wrote a seminal chronicle, the Gesta principum Polonorum,[9] intended as a glorification of his patron Bolesław III Wrymouth (r. 1107–38), a ruler who revived the tradition of military prowess of Bolesław I's time. Gallus' work remains a paramount written source for the early history of Poland.[13]

Fragmentation

After Bolesław III divided Poland among his sons in his Testament of 1138,[9] internal fragmentation eroded the Piast monarchical structures in the 12th and 13th centuries. In 1180, Casimir II the Just, who sought papal confirmation of his status as a senior duke, granted immunities and additional privileges to the Polish Church at the Congress of Łęczyca.[9] Around 1220, Wincenty Kadłubek wrote his Chronica seu originale regum et principum Poloniae, another major source for early Polish history.[9] In 1226, one of the regional Piast dukes, Konrad I of Masovia, invited the Teutonic Knights to help him fight the Baltic Prussian pagans.[9] The Teutonic Order destroyed the Prussians but kept their lands, which resulted in centuries of warfare between Poland and the Teutonic Knights, and later between Poland and the German Prussian state. The first Mongol invasion of Poland began in 1240; it culminated in the defeat of Polish and allied Christian forces and the death of the Silesian Piast Duke Henry II the Pious at the Battle of Legnica in 1241.[9] In 1242, Wrocław became the first Polish municipality to be incorporated,[9] as the period of fragmentation brought economic development and growth of towns. New cities were founded and existing settlements were granted town status per Magdeburg Law.[14] In 1264, Bolesław the Pious granted Jewish liberties in the Statute of Kalisz.[9][15]

Late Piast monarchy under Władysław I and Casimir III

Attempts to reunite the Polish lands gained momentum in the 13th century, and in 1295, Duke Przemysł II of Greater Poland managed to become the first ruler since Bolesław II to be crowned king of Poland.[9] He ruled over a limited territory and was soon killed. In 1300–05 King Wenceslaus II of Bohemia also reigned as king of Poland.[9] The Piast Kingdom was effectively restored under Władysław I the Elbow-high (r. 1306–33), who became king in 1320.[9] In 1308, the Teutonic Knights seized Gdańsk and the surrounding region of Pomerelia.[9]

King Casimir III the Great (r. 1333–70),[9] Władysław's son and the last of the Piast rulers, strengthened and expanded the restored Kingdom of Poland, but the western provinces of Silesia (formally ceded by Casimir in 1339) and most of Polish Pomerania were lost to the Polish state for centuries to come. Progress was made in the recovery of the separately governed central province of Mazovia, however, and in 1340, the conquest of Red Ruthenia began,[9] marking Poland's expansion to the east. The Congress of Kraków, a vast convocation of central, eastern, and northern European rulers probably assembled to plan an anti-Turkish crusade, took place in 1364, the same year that the future Jagiellonian University, one of the oldest European universities, was founded.[9][16] On 9 October 1334, Casimir III confirmed the privileges granted to Jews in 1264 by Bolesław the Pious and allowed them to settle in Poland in great numbers.

Angevin transition

After the Polish royal line and Piast junior branch died out in 1370, Poland came under the rule of Louis I of Hungary of the Capetian House of Anjou, who presided over a union of Hungary and Poland that lasted until 1382.[9] In 1374, Louis granted the Polish nobility the Privilege of Koszyce to assure the succession of one of his daughters in Poland.[9] His youngest daughter Jadwiga (d. 1399) assumed the Polish throne in 1384.[17]

Jagiellonian dynasty (1385–1572)

Dynastic union with Lithuania, Władysław II Jagiełło

In 1386, Grand Duke Jogaila of Lithuania converted to Catholicism and married Queen Jadwiga of Poland. This act enabled him to become a king of Poland himself,[18] and he ruled as Władysław II Jagiełło until his death in 1434. The marriage established a personal Polish–Lithuanian union ruled by the Jagiellonian dynasty. The first in a series of formal "unions" was the Union of Krewo of 1385, whereby arrangements were made for the marriage of Jogaila and Jadwiga.[18] The Polish–Lithuanian partnership brought vast areas of Ruthenia controlled by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania into Poland's sphere of influence and proved beneficial for the nationals of both countries, who coexisted and cooperated in one of the largest political entities in Europe for the next four centuries. When Queen Jadwiga died in 1399, the Kingdom of Poland fell to her husband's sole possession.[18][19]

In the Baltic Sea region, Poland's struggle with the Teutonic Knights continued and culminated in the Battle of Grunwald (1410),[18] a great victory that the Poles and Lithuanians were unable to follow up with a decisive strike against the main seat of the Teutonic Order at Malbork Castle. The Union of Horodło of 1413 further defined the evolving relationship between the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[18][20]

The privileges of the szlachta (nobility) kept expanding and in 1425 the rule of Neminem captivabimus, which protected the noblemen from arbitrary royal arrests, was formulated.[18]

Władysław III and Casimir IV Jagiellon

The reign of the young Władysław III (1434–44),[18] who succeeded his father Władysław II Jagiełło and ruled as king of Poland and Hungary, was cut short by his death at the Battle of Varna against the forces of the Ottoman Empire.[18][21] This disaster led to an interregnum of three years that ended with the accession of Władysław's brother Casimir IV Jagiellon in 1447.

Critical developments of the Jagiellonian period were concentrated during Casimir IV's long reign, which lasted until 1492. In 1454, Royal Prussia was incorporated by Poland and the Thirteen Years' War of 1454–66 with the Teutonic state ensued.[18] In 1466, the milestone Peace of Thorn was concluded. This treaty divided Prussia to create East Prussia, the future Duchy of Prussia, a separate entity that functioned as a fief of Poland under the administration of the Teutonic Knights.[18] Poland also confronted the Ottoman Empire and the Crimean Tatars in the south, and in the east helped Lithuania fight the Grand Duchy of Moscow. The country was developing as a feudal state, with a predominantly agricultural economy and an increasingly dominant landed nobility. Kraków, the royal capital, was turning into a major academic and cultural center, and in 1473 the first printing press began operating there.[18] With the growing importance of szlachta (middle and lower nobility), the king's council evolved to become by 1493 a bicameral General Sejm (parliament) that no longer represented exclusively top dignitaries of the realm.[18][22]

The Nihil novi act, adopted in 1505 by the Sejm, transferred most of the legislative power from the monarch to the Sejm.[18] This event marked the beginning of the period known as "Golden Liberty", when the state was ruled in principle by the "free and equal" Polish nobility. In the 16th century, the massive development of folwark agribusinesses operated by the nobility led to increasingly abusive conditions for the peasant serfs who worked them. The political monopoly of the nobles also stifled the development of cities, some of which were thriving during the late Jagiellonian era, and limited the rights of townspeople, effectively holding back the emergence of the middle class.[23]

Early modern Poland under Sigismund I and Sigismund II

In the 16th century, Protestant Reformation movements made deep inroads into Polish Christianity and the resulting Reformation in Poland involved a number of different denominations. The policies of religious tolerance that developed in Poland were nearly unique in Europe at that time and many who fled regions torn by religious strife found refuge in Poland. The reigns of King Sigismund I the Old (1506–1548) and King Sigismund II Augustus (1548–1572) witnessed an intense cultivation of culture and science (a Golden Age of the Renaissance in Poland), of which the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543)[18] is the best known representative. Jan Kochanowski (1530–1584) was a poet and the premier artistic personality of the period.[24][25] In 1525, during the reign of Sigismund I,[18] the Teutonic Order was secularized and Duke Albert performed an act of homage before the Polish king (the Prussian Homage) for his fief, the Duchy of Prussia.[18] Mazovia was finally fully incorporated into the Polish Crown in 1529.[18][26]

The reign of Sigismund II ended the Jagiellonian period, but gave rise to the Union of Lublin (1569), an ultimate fulfillment of the union with Lithuania. This agreement transferred Ukraine from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to Poland and transformed the Polish–Lithuanian polity into a real union,[18] preserving it beyond the death of the childless Sigismund II, whose active involvement made the completion of this process possible.[27]

Livonia in the far northeast was incorporated by Poland in 1561 and Poland entered the Livonian War against Russia.[18] The executionist movement, which attempted to check the progressing domination of the state by the magnate families of Poland and Lithuania, peaked at the Sejm in Piotrków in 1562–63.[18] On the religious front, the Polish Brethren split from the Calvinists, and the Protestant Brest Bible was published in 1563.[18] The Jesuits, who arrived in 1564,[18] were destined to make a major impact on Poland's history.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

Establishment (1569–1648)

Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin of 1569 established the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a federal state more closely unified than the earlier political arrangement between Poland and Lithuania. The union was run largely by the nobility through the system of central parliament and local assemblies, but was headed by elected kings. The formal rule of the nobility, who were proportionally more numerous than in other European countries, constituted an early democratic system ("a sophisticated noble democracy"),[28] in contrast to the absolute monarchies prevalent at that time in the rest of Europe.[29]

The beginning of the Commonwealth coincided with a period in Polish history when great political power was attained and advancements in civilization and prosperity took place. The Polish–Lithuanian Union became an influential participant in European affairs and a vital cultural entity that spread Western culture (with Polish characteristics) eastward. In the second half of the 16th century and the first half of the 17th century, the Commonwealth was one of the largest and most populous states in contemporary Europe, with an area approaching one million square kilometres (0.39 million square miles) and a population of about ten million. Its economy was dominated by export-focused agriculture. Nationwide religious toleration was guaranteed at the Warsaw Confederation in 1573.[24]

First elective kings

After the rule of the Jagiellonian dynasty ended in 1572, Henry of Valois (later King Henry III of France) was the winner of the first "free election" by the Polish nobility, held in 1573. He had to agree to the restrictive pacta conventa obligations and fled Poland in 1574 when news arrived of the vacancy of the French throne, to which he was the heir presumptive.[24] From the start, the royal elections increased foreign influence in the Commonwealth as foreign powers sought to manipulate the Polish nobility to place candidates amicable to their interests.[30] The reign of Stephen Báthory of Hungary followed (r. 1576–1586). He was militarily and domestically assertive and is revered in Polish historical tradition as a rare case of successful elective king.[24] The establishment of the legal Crown Tribunal in 1578 meant a transfer of many appellate cases from the royal to noble jurisdiction.[24]

First kings of the Vasa dynasty

A period of rule under the Swedish House of Vasa began in the Commonwealth in the year 1587. The first two kings from this dynasty, Sigismund III (r. 1587–1632) and Władysław IV (r. 1632–1648), repeatedly attempted to intrigue for accession to the throne of Sweden, which was a constant source of distraction for the affairs of the Commonwealth.[24] At that time, the Catholic Church embarked on an ideological counter-offensive and the Counter-Reformation claimed many converts from Polish and Lithuanian Protestant circles. In 1596, the Union of Brest split the Eastern Christians of the Commonwealth to create the Uniate Church of the Eastern Rite, but subject to the authority of the pope.[24] The Zebrzydowski rebellion against Sigismund III unfolded in 1606–1608.[24][31]

Seeking supremacy in Eastern Europe, the Commonwealth fought wars with Russia between 1605 and 1618 in the wake of Russia's Time of Troubles; the series of conflicts is referred to as the Polish–Muscovite War or the Dymitriads. The efforts resulted in expansion of the eastern territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, but the goal of taking over the Russian throne for the Polish ruling dynasty was not achieved. Sweden sought supremacy in the Baltic during the Polish–Swedish wars of 1617–1629, and the Ottoman Empire pressed from the south in the Battles at Cecora in 1620 and Khotyn in 1621.[24] The agricultural expansion and serfdom policies in Polish Ukraine resulted in a series of Cossack uprisings. Allied with the Habsburg Monarchy, the Commonwealth did not directly participate in the Thirty Years' War.[s] Władysław's IV reign was mostly peaceful, with a Russian invasion in the form of the Smolensk War of 1632–1634 successfully repelled.[24] The Orthodox Church hierarchy, banned in Poland after the Union of Brest, was re-established in 1635.[24][32]

Decline (1648–1764)

Deluge of wars

During the reign of John II Casimir Vasa (r. 1648–1668), the third and last king of his dynasty, the nobles' democracy fell into decline as a result of foreign invasions and domestic disorder.[24][33] These calamities multiplied rather suddenly and marked the end of the Polish Golden Age. Their effect was to render the once powerful Commonwealth increasingly vulnerable to foreign intervention.

The Cossack Khmelnytsky Uprising of 1648–1657 engulfed the south-eastern regions of the Polish crown;[24] its long-term effects were disastrous for the Commonwealth. The first liberum veto (a parliamentary device that allowed any member of the Sejm to dissolve a current session immediately) was exercised by a deputy in 1652.[24] This practice would eventually weaken Poland's central government critically. In the Treaty of Pereyaslav (1654), the Ukrainian rebels declared themselves subjects of the Tsar of Russia. The Second Northern War raged through the core Polish lands in 1655–1660; it included a brutal and devastating invasion of Poland referred to as the Swedish Deluge. The war ended in 1660 with the Treaty of Oliva,[24] which resulted in the loss of some of Poland's northern possessions. In 1657 the Treaty of Bromberg established the independence of the Duchy of Prussia.[24] The Commonwealth forces did well in the Russo-Polish War (1654–1667), but the end result was the permanent division of Ukraine between Poland and Russia, as agreed to in the Truce of Andrusovo (1667).[24] Towards the end of the war, the Lubomirski's rebellion, a major magnate revolt against the king, destabilized and weakened the country. The large-scale slave raids of the Crimean Tatars also had highly deleterious effects on the Polish economy.[35] Merkuriusz Polski, the first Polish newspaper, was published in 1661.[24][36]

In 1668, grief-stricken at the recent death of his wife and frustrated by the disastrous political setbacks of his reign, John II Casimir abdicated the throne and fled to France.[z]

John III Sobieski and last military victories

King Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki, a native Pole, was elected to replace John II Casimir in 1669. The Polish–Ottoman War (1672–76) broke out during his reign, which lasted until 1673, and continued under his successor, John III Sobieski (r. 1674–1696).[24] Sobieski intended to pursue Baltic area expansion (and to this end he signed the secret Treaty of Jaworów with France in 1675),[24] but was forced instead to fight protracted wars with the Ottoman Empire. By doing so, Sobieski briefly revived the Commonwealth's military might. He defeated the expanding Muslims at the Battle of Khotyn in 1673 and decisively helped deliver Vienna from a Turkish onslaught at the Battle of Vienna in 1683.[24] Sobieski's reign marked the last high point in the history of the Commonwealth: in the first half of the 18th century, Poland ceased to be an active player in international politics. The Treaty of Perpetual Peace (1686) with Russia was the final border settlement between the two countries before the First Partition of Poland in 1772.[24][37]

The Commonwealth, subjected to almost constant warfare until 1720, suffered enormous population losses and massive damage to its economy and social structure. The government became ineffective in the wake of large-scale internal conflicts, corrupted legislative processes and manipulation by foreign interests. The nobility fell under the control of a handful of feuding magnate families with established territorial domains. The urban population and infrastructure fell into ruin, together with most peasant farms, whose inhabitants were subjected to increasingly extreme forms of serfdom. The development of science, culture and education came to a halt or regressed.[33]

Saxon kings

The royal election of 1697 brought a ruler of the Saxon House of Wettin to the Polish throne: Augustus II the Strong (r. 1697–1733), who was able to assume the throne only by agreeing to convert to Roman Catholicism. He was succeeded by his son Augustus III (r. 1734–1763).[24] The reigns of the Saxon kings (who were both simultaneously prince-electors of Saxony) were disrupted by competing candidates for the throne and witnessed further disintegration of the Commonwealth.

The Great Northern War of 1700–1721,[24] a period seen by the contemporaries as a temporary eclipse, may have been the fatal blow that brought down the Polish political system. Stanisław Leszczyński was installed as king in 1704 under Swedish protection, but lasted only a few years.[38] The Silent Sejm of 1717 marked the beginning of the Commonwealth's existence as a Russian protectorate:[39] the Tsardom would guarantee the reform-impeding Golden Liberty of the nobility from that time on in order to cement the Commonwealth's weak central authority and a state of perpetual political impotence. In a resounding break with traditions of religious tolerance, Protestants were executed during the Tumult of Thorn in 1724.[40] In 1732, Russia, Austria and Prussia, Poland's three increasingly powerful and scheming neighbors, entered into the secret Treaty of the Three Black Eagles with the intention of controlling the future royal succession in the Commonwealth. The War of the Polish Succession was fought in 1733–1735[24] to assist Leszczyński in assuming the throne of Poland for a second time. Amidst considerable foreign involvement, his efforts were unsuccessful. The Kingdom of Prussia became a strong regional power and succeeded in wresting the historically Polish province of Silesia from the Habsburg Monarchy in the Silesian Wars; it thus constituted an ever-greater threat to Poland's security.

The personal union between the Commonwealth and the Electorate of Saxony did give rise to the emergence of a reform movement in the Commonwealth and the beginnings of the Polish Enlightenment culture, the major positive developments of this era. The first Polish public library was the Załuski Library in Warsaw, opened to the public in 1747.[24][41]

Reforms and loss of statehood (1764–1795)

Czartoryski reforms and Stanisław August Poniatowski

During the later part of the 18th century, fundamental internal reforms were attempted in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as it slid into extinction. The reform activity, initially promoted by the magnate Czartoryski family faction known as the Familia, provoked a hostile reaction and military response from neighboring powers, but it did create conditions that fostered economic improvement. The most populous urban center, the capital city of Warsaw, replaced Danzig (Gdańsk) as the leading trade center, and the importance of the more prosperous urban social classes increased. The last decades of the independent Commonwealth's existence were characterized by aggressive reform movements and far-reaching progress in the areas of education, intellectual life, art and the evolution of the social and political system.[42]

The royal election of 1764 resulted in the elevation of Stanisław August Poniatowski,[43] a refined and worldly aristocrat connected to the Czartoryski family, but hand-picked and imposed by Empress Catherine the Great of Russia, who expected him to be her obedient follower. Stanisław August ruled the Polish–Lithuanian state until its dissolution in 1795. The king spent his reign torn between his desire to implement reforms necessary to save the failing state and the perceived necessity of remaining in a subordinate relationship to his Russian sponsors.[44]

The Bar Confederation (1768–1772)[43] was a rebellion of nobles directed against Russia's influence in general and Stanisław August, who was seen as its representative, in particular. It was fought to preserve Poland's independence and the nobility's traditional interests. After several years, it was brought under control by forces loyal to the king and those of the Russian Empire.[45]

Following the suppression of the Bar Confederation, parts of the Commonwealth were divided up among Prussia, Austria and Russia in 1772 at the instigation of Frederick the Great of Prussia, an action that became known as the First Partition of Poland:[43] the outer provinces of the Commonwealth were seized by agreement among the country's three powerful neighbors and only a rump state remained. In 1773, the "Partition Sejm" ratified the partition under duress as a fait accompli. However, it also established the Commission of National Education, a pioneering in Europe education authority often called the world's first ministry of education.[43][45]

The Great Sejm of 1788–1791 and the Constitution of 3 May 1791

The long-lasting session of parliament convened by King Stanisław August is known as the Great Sejm or Four-Year Sejm; it first met in 1788. Its landmark achievement was the passing of the Constitution of 3 May 1791,[43] the first singular pronouncement of a supreme law of the state in modern Europe. A moderately reformist document condemned by detractors as sympathetic to the ideals of the French Revolution, it soon generated strong opposition from the conservative circles of the Commonwealth's upper nobility and from Empress Catherine of Russia, who was determined to prevent the rebirth of a strong Commonwealth. The nobility's Targowica Confederation, formed in Russian imperial capital of Saint Petersburg, appealed to Catherine for help, and in May 1792, the Russian army entered the territory of the Commonwealth.[43] The Polish–Russian War of 1792, a defensive war fought by the forces of the Commonwealth against Russian invaders, ended when the Polish king, convinced of the futility of resistance, capitulated by joining the Targowica Confederation. The Russian-allied confederation took over the government, but Russia and Prussia in 1793 arranged for the Second Partition of Poland anyway. The partition left the country with a critically reduced territory that rendered it essentially incapable of an independent existence. The Commonwealth's Grodno Sejm of 1793, the last Sejm of the state's existence,[43] was compelled to confirm the new partition.[46]

The Kościuszko Uprising of 1794 and the end of Polish–Lithuanian state

Radicalized by recent events, Polish reformers (whether in exile or still resident in the reduced area remaining to the Commonwealth) were soon working on preparations for a national insurrection. Tadeusz Kościuszko, a popular general and a veteran of the American Revolution, was chosen as its leader. He returned from abroad and issued Kościuszko's proclamation in Kraków on March 24, 1794. It called for a national uprising under his supreme command.[43] Kościuszko emancipated many peasants in order to enroll them as kosynierzy in his army, but the hard-fought insurrection, despite widespread national support, proved incapable of generating the foreign assistance necessary for its success. In the end, it was suppressed by the combined forces of Russia and Prussia, with Warsaw captured in November 1794 in the aftermath of the Battle of Praga.

In 1795, a Third Partition of Poland was undertaken by Russia, Prussia and Austria as a final division of territory that resulted in the effective dissolution of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[43] King Stanisław August Poniatowski was escorted to Grodno, forced to abdicate, and retired to Saint Petersburg.[43][47] Tadeusz Kościuszko, initially imprisoned, was allowed to emigrate to the United States in 1796.[48]

The response of the Polish leadership to the last partition is a matter of historical debate. Literary scholars found that the dominant emotion of the first decade was despair that produced a moral desert ruled by violence and treason. On the other hand, historians have looked for signs of resistance to foreign rule. Apart from those who went into exile, the nobility took oaths of loyalty to their new rulers and served as officers in their armies.[49]

Partitioned Poland (1795–1918)

Armed resistance (1795–1864)

Napoleonic wars

Although no sovereign Polish state existed between 1795 and 1918, the idea of Polish independence was kept alive throughout the 19th century. There were a number of uprisings and other armed undertakings waged against the partitioning powers. Military efforts after the partitions were first based on the alliances of Polish émigrés with post-revolutionary France. Jan Henryk Dąbrowski's Polish Legions fought in French campaigns outside of Poland between 1797 and 1802 in hopes that their involvement and contribution would be rewarded with the liberation of their Polish homeland.[50] The Polish national anthem, "Poland Is Not Yet Lost", or "Dąbrowski's Mazurka", was written in praise of his actions by Józef Wybicki in 1797.[51]

The Duchy of Warsaw, a small, semi-independent Polish state, was created in 1807 by Napoleon in the wake of his defeat of Prussia and the signing of the Treaties of Tilsit with Emperor Alexander I of Russia.[50] The Army of the Duchy of Warsaw, led by Józef Poniatowski, participated in numerous campaigns in alliance with France, including the successful Austro-Polish War of 1809, which, combined with the outcomes of other theaters of the War of the Fifth Coalition, resulted in an enlargement of the duchy's territory. The French invasion of Russia in 1812 and the German Campaign of 1813 saw the duchy's last military engagements. The Constitution of the Duchy of Warsaw abolished serfdom as a reflection of the ideals of the French Revolution, but it did not promote land reform.[52]

The Congress of Vienna

After Napoleon's defeat, a new European order was established at the Congress of Vienna, which met in the years 1814 and 1815. Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, a former close associate of Emperor Alexander I, became the leading advocate for the Polish national cause. The Congress implemented a new partition scheme, which took into account some of the gains realized by the Poles during the Napoleonic period.

The Duchy of Warsaw was replaced in 1815 with a new Kingdom of Poland, unofficially known as Congress Poland.[50] The residual Polish kingdom was joined to the Russian Empire in a personal union under the Russian tsar and it was allowed its own constitution and military. East of the kingdom, large areas of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth remained directly incorporated into the Russian Empire as the Western Krai. These territories, along with Congress Poland, are generally considered to form the Russian Partition. The Russian, Prussian, and Austrian "partitions" are informal names for the lands of the former Commonwealth, not actual units of administrative division of Polish–Lithuanian territories after partitions.[53] The Prussian Partition included a portion separated as the Grand Duchy of Posen.[50] Peasants under the Prussian administration were gradually enfranchised under the reforms of 1811 and 1823. The limited legal reforms in the Austrian Partition were overshadowed by its rural poverty. The Free City of Cracow was a tiny republic created by the Congress of Vienna under the joint supervision of the three partitioning powers.[50] Despite the bleak from the standpoint of Polish patriots political situation, economic progress was made in the lands taken over by foreign powers because the period after the Congress of Vienna witnessed a significant development in the building of early industry.[53]

Economic historians have made new estimates on GDP per capita, 1790–1910. They confirm the hypothesis of semi-peripheral development of Polish territories in the 19th century and the slow process of catching-up with the core economies.[54]

The Uprising of November 1830

The increasingly repressive policies of the partitioning powers led to resistance movements in partitioned Poland, and in 1830 Polish patriots staged the November Uprising.[50] This revolt developed into a full-scale war with Russia, but the leadership was taken over by Polish conservatives who were reluctant to challenge the empire and hostile to broadening the independence movement's social base through measures such as land reform. Despite the significant resources mobilized, a series of errors by several successive chief commanders appointed by the insurgent Polish National Government led to the defeat of its forces by the Russian army in 1831.[50] Congress Poland lost its constitution and military, but formally remained a separate administrative unit within the Russian Empire.[55]

After the defeat of the November Uprising, thousands of former Polish combatants and other activists emigrated to Western Europe. This phenomenon, known as the Great Emigration, soon dominated Polish political and intellectual life. Together with the leaders of the independence movement, the Polish community abroad included the greatest Polish literary and artistic minds, including the Romantic poets Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, Cyprian Norwid, and the composer Frédéric Chopin. In occupied and repressed Poland, some sought progress through nonviolent activism focused on education and economy, known as organic work; others, in cooperation with the emigrant circles, organized conspiracies and prepared for the next armed insurrection.[56]

Revolts of the era of the Spring of Nations

The planned national uprising failed to materialize because the authorities in the partitions found out about secret preparations. The Greater Poland uprising ended in a fiasco in early 1846. In the Kraków uprising of February 1846,[50] patriotic action was combined with revolutionary demands, but the result was the incorporation of the Free City of Cracow into the Austrian Partition. The Austrian officials took advantage of peasant discontent and incited villagers against the noble-dominated insurgent units. This resulted in the Galician slaughter of 1846,[50] a large-scale rebellion of serfs seeking relief from their post-feudal condition of mandatory labor as practiced in folwarks. The uprising freed many from bondage and hastened decisions that led to the abolition of Polish serfdom in the Austrian Empire in 1848. A new wave of Polish involvement in revolutionary movements soon took place in the partitions and in other parts of Europe in the context of the Spring of Nations revolutions of 1848 (e.g. Józef Bem's participation in the revolutions in Austria and Hungary). The 1848 German revolutions precipitated the Greater Poland uprising of 1848,[50] in which peasants in the Prussian Partition, who were by then largely enfranchised, played a prominent role.[57]

The Uprising of January 1863

As a matter of continuous policy, the Russian autocracy kept assailing Polish national core values of language, religion and culture.[58] In consequence, despite the limited liberalization measures allowed in Congress Poland under the rule of Tsar Alexander II of Russia, a renewal of popular liberation activities took place in 1860–1861. During large-scale demonstrations in Warsaw, Russian forces inflicted numerous casualties on the civilian participants. The "Red", or left-wing faction of Polish activists, which promoted peasant enfranchisement and cooperated with Russian revolutionaries, became involved in immediate preparations for a national uprising. The "White", or right-wing faction, was inclined to cooperate with the Russian authorities and countered with partial reform proposals. In order to cripple the manpower potential of the Reds, Aleksander Wielopolski, the conservative leader of the government of Congress Poland, arranged for a partial selective conscription of young Poles for the Russian army in the years 1862 and 1863.[50] This action hastened the outbreak of hostilities. The January Uprising, joined and led after the initial period by the Whites, was fought by partisan units against an overwhelmingly advantaged enemy. The uprising lasted from January 1863 to the spring of 1864,[50] when Romuald Traugutt, the last supreme commander of the insurgency, was captured by the tsarist police.[59][60]

On 2 March 1864, the Russian authority, compelled by the uprising to compete for the loyalty of Polish peasants, officially published an enfranchisement decree in Congress Poland along the lines of an earlier land reform proclamation of the insurgents. The act created the conditions necessary for the development of the capitalist system on central Polish lands. At the time when most Poles realized the futility of armed resistance without external support, the various sections of Polish society were undergoing deep and far-reaching evolution in the areas of social, economic and cultural development.[50][60][61]

Formation of modern Polish society under foreign rule (1864–1914)

Repression and organic work

The failure of the January Uprising in Poland caused a major psychological trauma and became a historic watershed; indeed, it sparked the development of modern Polish nationalism. The Poles, subjected within the territories under the Russian and Prussian administrations to still stricter controls and increased persecution, sought to preserve their identity in non-violent ways. After the uprising, Congress Poland was downgraded in official usage from the "Kingdom of Poland" to the "Vistula Land" and was more fully integrated into Russia proper, but not entirely obliterated. The Russian and German languages were imposed in all public communication, and the Catholic Church was not spared from severe repression. Public education was increasingly subjected to Russification and Germanisation measures. Illiteracy was reduced, most effectively in the Prussian partition, but education in the Polish language was preserved mostly through unofficial efforts. The Prussian government pursued German colonization, including the purchase of Polish-owned land. On the other hand, the region of Galicia (western Ukraine and southern Poland) experienced a gradual relaxation of authoritarian policies and even a Polish cultural revival. Economically and socially backward, it was under the milder rule of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and from 1867 was increasingly allowed limited autonomy.[50] Stańczycy, a conservative Polish pro-Austrian faction led by great land owners, dominated the Galician government. The Polish Academy of Learning (an academy of sciences) was founded in Kraków in 1872.[50]

Social activities termed "organic work" consisted of self-help organizations that promoted economic advancement and work on improving the competitiveness of Polish-owned businesses, industrial, agricultural or other. New commercial methods of generating higher productivity were discussed and implemented through trade associations and special interest groups, while Polish banking and cooperative financial institutions made the necessary business loans available. The other major area of effort in organic work was educational and intellectual development of the common people. Many libraries and reading rooms were established in small towns and villages, and numerous printed periodicals manifested the growing interest in popular education. Scientific and educational societies were active in a number of cities. Such activities were most pronounced in the Prussian Partition.[62][63]

Positivism in Poland replaced Romanticism as the leading intellectual, social and literary trend.[62][64] It reflected the ideals and values of the emerging urban bourgeoisie.[65] Around 1890, the urban classes gradually abandoned the positivist ideas and came under the influence of modern pan-European nationalism.[66]

Economic development and social change

Under the partitioning powers, economic diversification and progress, including large-scale industrialisation, were introduced in the traditionally agrarian Polish lands, but this development turned out to be very uneven. Advanced agriculture was practiced in the Prussian Partition, except for Upper Silesia, where the coal-mining industry created a large labor force. The densest network of railroads was built in German-ruled western Poland. In Russian Congress Poland, a striking growth of industry, railways and towns took place, all against the background of an extensive, but less productive agriculture.[67] The industrial initiative, capital and know-how were provided largely by entrepreneurs who were not ethnic Poles.[68] Warsaw (a metallurgical center) and Łódź (a textiles center) grew rapidly, as did the total proportion of urban population, making the region the most economically advanced in the Russian Empire (industrial production exceeded agricultural production there by 1909). The coming of the railways spurred some industrial growth even in the vast Russian Partition territories outside of Congress Poland. The Austrian Partition was rural and poor, except for the industrialized Cieszyn Silesia area. Galician economic expansion after 1890 included oil extraction and resulted in the growth of Lemberg (Lwów, Lviv) and Kraków.[67]

Economic and social changes involving land reform and industrialization, combined with the effects of foreign domination, altered the centuries-old social structure of Polish society. Among the newly emergent strata were wealthy industrialists and financiers, distinct from the traditional, but still critically important landed aristocracy. The intelligentsia, an educated, professional or business middle class, often originated from lower gentry, landless or alienated from their rural possessions, and from urban people. Many smaller agricultural enterprises based on serfdom did not survive the land reforms.[69] The industrial proletariat, a new underprivileged class, was composed mainly of poor peasants or townspeople forced by deteriorating conditions to migrate and search for work in urban centers in their countries of origin or abroad. Millions of residents of the former Commonwealth of various ethnic groups worked or settled in Europe and in North and South America.[67]

Social and economic changes were partial and gradual. The degree of industrialisation, relatively fast-paced in some areas, lagged behind the advanced regions of Western Europe. The three partitions developed different economies and were more economically integrated with their mother states than with each other. In the Prussian Partition, for example, agricultural production depended heavily on the German market, whereas the industrial sector of Congress Poland relied more on the Russian market.[67]

Nationalism, socialism and other movements

In the 1870s–1890s, large-scale socialist, nationalist, agrarian and other political movements of great ideological fervor became established in partitioned Poland and Lithuania, along with corresponding political parties to promote them. Of the major parties, the socialist First Proletariat was founded in 1882, the Polish League (precursor of National Democracy) in 1887, the Polish Social Democratic Party of Galicia and Silesia in 1890, the Polish Socialist Party in 1892, the Marxist Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania in 1893, the agrarian People's Party of Galicia in 1895 and the Jewish socialist Bund in 1897. Christian democracy regional associations allied with the Catholic Church were also active; they united into the Polish Christian Democratic Party in 1919.

The main minority ethnic groups of the former Commonwealth, including Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Belarusians and Jews, were getting involved in their own national movements and plans, which met with disapproval on the part of those Polish independence activists who counted on an eventual rebirth of the Commonwealth or the rise of a Commonwealth-inspired federal structure (a political movement referred to as Prometheism).[70]

Around the start of the 20th century, the Young Poland cultural movement, centered in Austrian Galicia, took advantage of a milieu conducive to liberal expression in that region and was the source of Poland's finest artistic and literary productions.[71] In this same era, Marie Skłodowska Curie, a pioneer radiation scientist, performed her groundbreaking research in Paris.[72]

The Revolution of 1905

The Revolution of 1905–1907 in Russian Poland,[50] the result of many years of pent-up political frustrations and stifled national ambitions, was marked by political maneuvering, strikes and rebellion. The revolt was part of much broader disturbances throughout the Russian Empire associated with the general Revolution of 1905. In Poland, the principal revolutionary figures were Roman Dmowski and Józef Piłsudski. Dmowski was associated with the right-wing nationalist movement National Democracy, whereas Piłsudski was associated with the Polish Socialist Party. As the authorities re-established control within the Russian Empire, the revolt in Congress Poland, placed under martial law, withered as well, partially as a result of tsarist concessions in the areas of national and workers' rights, including Polish representation in the newly created Russian Duma. The collapse of the revolt in the Russian Partition, coupled with intensified Germanization in the Prussian Partition, left Austrian Galicia as the territory where Polish patriotic action was most likely to flourish.[73]

In the Austrian Partition, Polish culture was openly cultivated, and in the Prussian Partition, there were high levels of education and living standards, but the Russian Partition remained of primary importance for the Polish nation and its aspirations. About 15.5 million Polish-speakers lived in the territories most densely populated by Poles: the western part of the Russian Partition, the Prussian Partition and the western Austrian Partition. Ethnically Polish settlement spread over a large area further to the east, including its greatest concentration in the Vilnius Region, amounted to only over 20% of that number.[74]

Polish paramilitary organizations oriented toward independence, such as the Union of Active Struggle, were formed in 1908–1914, mainly in Galicia. The Poles were divided and their political parties fragmented on the eve of World War I, with Dmowski's National Democracy (pro-Entente) and Piłsudski's faction assuming opposing positions.[74][75]

World War I and the issue of Poland's independence

The outbreak of World War I in the Polish lands offered Poles unexpected hopes for achieving independence as a result of the turbulence that engulfed the empires of the partitioning powers. All three of the monarchies that had benefited from the partition of Polish territories (Germany, Austria and Russia) were dissolved by the end of the war, and many of their territories were dispersed into new political units. At the start of the war, the Poles found themselves conscripted into the armies of the partitioning powers in a war that was not theirs. Furthermore, they were frequently forced to fight each other, since the armies of Germany and Austria were allied against Russia. Piłsudski's paramilitary units stationed in Galicia were turned into the Polish Legions in 1914 and as a part of the Austro-Hungarian Army fought on the Russian front until 1917, when the formation was disbanded.[50] Piłsudski, who refused demands that his men fight under German command, was arrested and imprisoned by the Germans and became a heroic symbol of Polish nationalism.[75][76]

Due to a series of German victories on the Eastern Front, the area of Congress Poland became occupied by the Central Powers of Germany and Austria;[50] Warsaw was captured by the Germans on 5 August 1915. In the Act of 5th November 1916, a fresh incarnation of the Kingdom of Poland (Królestwo Regencyjne) was proclaimed by Germany and Austria on formerly Russian-controlled territories,[50] within the German Mitteleuropa scheme. The sponsor states were never able to agree on a candidate to assume the throne, however; rather, it was governed in turn by German and Austrian governor-generals, a Provisional Council of State, and a Regency Council. This increasingly autonomous puppet state existed until November 1918, when it was replaced by the newly established Republic of Poland. The existence of this "kingdom" and its planned Polish army had a positive effect on the Polish national efforts on the Allied side, but in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk of March 1918 the victorious in the east Germany imposed harsh conditions on defeated Russia and ignored Polish interests.[75][76][77] Toward the end of the war, the German authorities engaged in massive, purposeful devastation of industrial and other economic potential of Polish lands in order to impoverish the country, a likely future competitor of Germany.[78]

The independence of Poland had been campaigned for in Russia and in the West by Dmowski and in the West by Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, and then the leaders of the February Revolution and the October Revolution of 1917, installed governments who declared in turn their support for Polish independence.[76][d1] In 1917, France formed the Blue Army (placed under Józef Haller) that comprised about 70,000 Poles by the end of the war, including men captured from German and Austrian units and 20,000 volunteers from the United States. There was also a 30,000-men strong Polish anti-German army in Russia. Dmowski, operating from Paris as head of the Polish National Committee (KNP), became the spokesman for Polish nationalism in the Allied camp. On the initiative of Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points, Polish independence was officially endorsed by the Allies in June 1918.[50][75][76][c1]

In all, about two million Poles served in the war, counting both sides, and about 400–450,000 died. Much of the fighting on the Eastern Front took place in Poland, and civilian casualties and devastation were high.[75][79]

The final push for independence of Poland took place on the ground in October–November 1918. Near the end of the war, Austro-Hungarian and German units were being disarmed, and the Austrian army's collapse freed Cieszyn and Kraków at the end of October. Lviv was then contested in the Polish–Ukrainian War of 1918–1919. Ignacy Daszyński headed the first short-lived independent Polish government in Lublin from 7 November, the leftist Provisional People's Government of the Republic of Poland, proclaimed as a democracy. Germany, now defeated, was forced by the Allies to stand down its large military forces in Poland. Overtaken by the German Revolution of 1918–1919 at home, the Germans released Piłsudski from prison. He arrived in Warsaw on 10 November and was granted extensive authority by the Regency Council; Piłsudski's authority was also recognized by the Lublin government.[50][b1] On 22 November, he became the temporary head of state. Piłsudski was held by many in high regard, but was resented by the right-wing National Democrats. The emerging Polish state was internally divided, heavily war-damaged and economically dysfunctional.[75][76]

Second Polish Republic (1918–1939)

Securing national borders, war with Soviet Russia

After more than a century of foreign rule, Poland regained its independence at the end of World War I as one of the outcomes of the negotiations that took place at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919.[80] The Treaty of Versailles that emerged from the conference set up an independent Polish nation with an outlet to the sea, but left some of its boundaries to be decided by plebiscites. The largely German-inhabited Free City of Danzig was granted a separate status that guaranteed its use as a port by Poland. In the end, the settlement of the German-Polish border turned out to be a prolonged and convoluted process. The dispute helped engender the Greater Poland Uprising of 1918–1919, the three Silesian uprisings of 1919–1921, the East Prussian plebiscite of 1920, the Upper Silesia plebiscite of 1921 and the 1922 Silesian Convention in Geneva.[81][82][83]

Other boundaries were settled by war and subsequent treaties. A total of six border wars were fought in 1918–1921, including the Polish–Czechoslovak border conflicts over Cieszyn Silesia in January 1919.[81]

As distressing as these border conflicts were, the Polish–Soviet War of 1919–1921 was the most important series of military actions of the era. Piłsudski had entertained far-reaching anti-Russian cooperative designs in Eastern Europe, and in 1919 the Polish forces pushed eastward into Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine by taking advantage of the Russian preoccupation with a civil war, but they were soon confronted with the Soviet westward offensive of 1918–1919. Western Ukraine was already a theater of the Polish–Ukrainian War, which eliminated the proclaimed West Ukrainian People's Republic in July 1919. In the autumn of 1919, Piłsudski rejected urgent pleas from the former Entente powers to support Anton Denikin's White movement in its advance on Moscow.[81] The Polish–Soviet War proper began with the Polish Kiev Offensive in April 1920.[84] Allied with the Directorate of Ukraine of the Ukrainian People's Republic, the Polish armies had advanced past Vilnius, Minsk and Kiev by June.[85] At that time, a massive Soviet counter-offensive pushed the Poles out of most of Ukraine. On the northern front, the Soviet army reached the outskirts of Warsaw in early August. A Soviet triumph and the quick end of Poland seemed inevitable. However, the Poles scored a stunning victory at the Battle of Warsaw (1920). Afterwards, more Polish military successes followed, and the Soviets had to pull back. They left swathes of territory populated largely by Belarusians or Ukrainians to Polish rule. The new eastern boundary was finalized by the Peace of Riga in March 1921.[81][83][86]

The defeat of the Russian armies forced Vladimir Lenin and the Soviet leadership to postpone their strategic objective of linking up with the German and other European revolutionary leftist collaborators to spread communist revolution. Lenin also hoped for generating support for the Red Army in Poland, which failed to materialize.[81]

Piłsudski's seizure of Vilnius in October 1920 (known as Żeligowski's Mutiny) was a nail in the coffin of the already poor Lithuania–Poland relations that had been strained by the Polish–Lithuanian War of 1919–1920; both states would remain hostile to one another for the remainder of the interwar period.[87] Piłsudski's concept of Intermarium (an East European federation of states inspired by the tradition of the multiethnic Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that would include a hypothetical multinational successor state to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania)[88] had the fatal flaw of being incompatible with his assumption of Polish domination, which would amount to an encroachment on the neighboring peoples' lands and aspirations. At the time of rising national movements, the plan thus ceased being a feature of Poland's politics.[89][90][91][a] A larger federated structure was also opposed by Dmowski's National Democrats. Their representative at the Peace of Riga talks, Stanisław Grabski, opted for leaving Minsk, Berdychiv, Kamianets-Podilskyi and the surrounding areas on the Soviet side of the border. The National Democrats did not want to assume the lands they considered politically undesirable, as such territorial enlargement would result in a reduced proportion of citizens who were ethnically Polish.[83][92][93]

The Peace of Riga settled the eastern border by preserving for Poland a substantial portion of the old Commonwealth's eastern territories at the cost of partitioning the lands of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania (Lithuania and Belarus) and Ukraine.[83][94][95] The Ukrainians ended up with no state of their own and felt betrayed by the Riga arrangements; their resentment gave rise to extreme nationalism and anti-Polish hostility.[96] The Kresy (or borderland) territories in the east won by 1921 would form the basis for a swap arranged and carried out by the Soviets in 1943–1945, who at that time compensated the re-emerging Polish state for the eastern lands lost to the Soviet Union with conquered areas of eastern Germany.[97]

The successful outcome of the Polish–Soviet War gave Poland a false sense of its prowess as a self-sufficient military power and encouraged the government to try to resolve international problems through imposed unilateral solutions.[89][98] The territorial and ethnic policies of the interwar period contributed to bad relations with most of Poland's neighbors and uneasy cooperation with more distant centers of power, especially France and Great Britain.[83][89][98]

Democratic politics (1918–1926)

Among the chief difficulties faced by the government of the new Polish republic was the lack of an integrated infrastructure among the formerly separate partitions, a deficiency that disrupted industry, transportation, trade, and other areas.[81]

The first Polish legislative election for the re-established Sejm (national parliament) took place in January 1919. A temporary Small Constitution was passed by the body the following month.[99]

The rapidly growing population of Poland within its new boundaries was ¾ agricultural and ¼ urban; Polish was the primary language of only ⅔ of the inhabitants of the new country. The minorities had very little voice in the government. The permanent March Constitution of Poland was adopted in March 1921. At the insistence of the National Democrats, who were concerned about how aggressively Józef Piłsudski might exercise presidential powers if he were elected to office, the constitution mandated limited prerogatives for the presidency.[83]

The proclamation of the March Constitution was followed by a short and turbulent period of constitutional order and parliamentary democracy that lasted until 1926. The legislature remained fragmented, without stable majorities, and governments changed frequently. The open-minded Gabriel Narutowicz was elected president constitutionally (without a popular vote) by the National Assembly in 1922. However, members of the nationalist right-wing faction did not regard his elevation as legitimate. They viewed Narutowicz rather as a traitor whose election was pushed through by the votes of alien minorities. Narutowicz and his supporters were subjected to an intense harassment campaign, and the president was assassinated on 16 December 1922, after serving only five days in office.[100]

Corruption was held to be commonplace in the political culture of the early Polish Republic. However, the investigations conducted by the new regime after the 1926 May Coup failed to uncover any major affair or corruption scheme within the state apparatus of its predecessors.[101]

Land reform measures were passed in 1919 and 1925 under pressure from an impoverished peasantry. They were partially implemented, but resulted in the parcellation of only 20% of the great agricultural estates.[102] Poland endured numerous economic calamities and disruptions in the early 1920s, including waves of workers' strikes such as the 1923 Kraków riot. The German–Polish customs war, initiated by Germany in 1925, was one of the most damaging external factors that put a strain on Poland's economy.[103][104] On the other hand, there were also signs of progress and stabilization, for example a critical reform of finances carried out by the competent government of Władysław Grabski, which lasted almost two years. Certain other achievements of the democratic period having to do with the management of governmental and civic institutions necessary to the functioning of the reunited state and nation were too easily overlooked. Lurking on the sidelines was a disgusted army officer corps unwilling to subject itself to civilian control, but ready to follow the retired Piłsudski, who was highly popular with Poles and just as dissatisfied with the Polish system of government as his former colleagues in the military.[81][100]

Piłsudski's coup and the Sanation Era (1926–1935)

On 12 May 1926, Piłsudski staged the May Coup, a military overthrow of the civilian government mounted against President Stanisław Wojciechowski and the troops loyal to the legitimate government. Hundreds died in fratricidal fighting.[105] Piłsudski was supported by several leftist factions who ensured the success of his coup by blocking the railway transportation of government forces.[106][b1] He also had the support of the conservative great landowners, a move that left the right-wing National Democrats as the only major social force opposed to the takeover.[81][107][l]

Following the coup, the new regime initially respected many parliamentary formalities, but gradually tightened its control and abandoned pretenses. The Centrolew, a coalition of center-left parties, was formed in 1929, and in 1930 called for the "abolition of dictatorship". In 1930, the Sejm was dissolved and a number of opposition deputies were imprisoned at the Brest Fortress. Five thousand political opponents were arrested ahead of the Polish legislative election of 1930,[108] which was rigged to award a majority of seats to the pro-regime Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government (BBWR).[81][101][109]

The authoritarian Sanation regime ("sanation" meant to denote "healing") that Piłsudski led until his death in 1935 (and would remain in place until 1939) reflected the dictator's evolution from his center-left past to conservative alliances.[101] Political institutions and parties were allowed to function, but the electoral process was manipulated and those not willing to cooperate submissively were subjected to repression. From 1930, persistent opponents of the regime, many of the leftist persuasion, were imprisoned and subjected to staged legal processes with harsh sentences, such as the Brest trials, or else detained in the Bereza Kartuska prison and similar camps for political prisoners. About three thousand were detained without trial at different times at the Bereza internment camp between 1934 and 1939. In 1936 for example, 369 activists were taken there, including 342 Polish communists.[110] Rebellious peasants staged riots in 1932, 1933 and the 1937 peasant strike in Poland. Other civil disturbances were caused by striking industrial workers (e.g. events of the "Bloody Spring" of 1936), nationalist Ukrainians[p] and the activists of the incipient Belarusian movement. All became targets of ruthless police-military pacification.[81][111][112][113][y] Besides sponsoring political repression, the regime fostered Józef Piłsudski's cult of personality that had already existed long before he assumed dictatorial powers.

Piłsudski signed the Soviet–Polish Non-Aggression Pact in 1932 and the German–Polish Non-Aggression Pact in 1934,[106] but in 1933 he insisted that there was no threat from the East or West and said that Poland's politics were focused on becoming fully independent without serving foreign interests.[114] He initiated the policy of maintaining an equal distance and an adjustable middle course regarding the two great neighbors, later continued by Józef Beck.[115] Piłsudski kept personal control of the army, but it was poorly equipped, poorly trained and had poor preparations in place for possible future conflicts.[116] His only war plan was a defensive war against a Soviet invasion.[117][r] The slow modernization after Piłsudski's death fell far behind the progress made by Poland's neighbors and measures to protect the western border, discontinued by Piłsudski from 1926, were not undertaken until March 1939.[118]

Sanation deputies in the Sejm used a parliamentary maneuver to abolish the democratic March Constitution and push through a more authoritarian April Constitution in 1935; it reduced the powers of the Sejm, which Piłsudski despised.[81] The process and the resulting document were seen as illegitimate by the anti-Sanation opposition, but during World War II, the Polish government-in-exile recognized the April Constitution in order to uphold the legal continuity of the Polish state.[119]

When Marshal Piłsudski died in 1935, he retained the support of dominant sections of Polish society even though he never risked testing his popularity in an honest election. His regime was dictatorial, but at that time only Czechoslovakia remained democratic in all of the regions neighboring Poland. Historians have taken widely divergent views of the meaning and consequences of the coup Piłsudski perpetrated and his personal rule that followed.[109]

Social and economic trends of the interwar period

Independence stimulated the development of Polish culture in the Interbellum and intellectual achievement was high. Warsaw, whose population almost doubled between World War I and World War II, was a restless, burgeoning metropolis. It outpaced Kraków, Lwów and Wilno, the other major population centers of the country.[81]

Mainstream Polish society was not affected by the repressions of the Sanation authorities overall;[120] many Poles enjoyed relative stability, and the economy improved markedly between 1926 and 1929, only to become caught up in the global Great Depression.[121] After 1929, the country's industrial production and gross national income slumped by about 50%.[122]

The Great Depression brought low prices for farmers and unemployment for workers. Social tensions increased, including rising antisemitism. A major economic transformation and multi-year state plan to achieve national industrial development, as embodied in the Central Industrial Region initiative launched in 1936, was led by Minister Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski. Motivated primarily by the need for a native arms industry, the initiative was in progress at the time of the outbreak of World War II. Kwiatkowski was also the main architect of the earlier Gdynia seaport project.[81][123]

The prevalent in political circles nationalism was fueled by the large size of Poland's minority populations and their separate agendas. According to the language criterion of the Polish census of 1931, the Poles constituted 69% of the population, Ukrainians 15%, Jews (defined as speakers of the Yiddish language) 8.5%, Belarusians 4.7%, Germans 2.2%, Lithuanians 0.25%, Russians 0.25% and Czechs 0.09%, with some geographical areas dominated by a particular minority. In time, the ethnic conflicts intensified, and the Polish state grew less tolerant of the interests of its national minorities. In interwar Poland, compulsory free general education substantially reduced illiteracy rates, but discrimination was practiced in a way that resulted in a dramatic decrease in the number of Ukrainian language schools and official restrictions on Jewish attendance at selected schools in the late 1930s.[81]