Wild boar

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2009) |

| Wild Boar Temporal range: Early Pleistocene – Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | S. scrofa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Sus scrofa Linnaeus, 1758

| |

Wild boar (Sus scrofa) is a species of pig (including many subspecies), part of the biological family Suidae. It is the wild ancestor of the domestic pig, an animal with which it freely hybridises.[2] Wild boar are native across much of Northern and Central Europe, the Mediterranean Region (including North Africa's Atlas Mountains) and much of Asia as far south as Indonesia. Populations have also been artificially introduced in some parts of the world, most notably the Americas and Australasia; principally for hunting. Elsewhere, populations have also become established after escapes of wild boar from captivity.[3]

Name

The term boar is used to denote an adult male of certain species — including, confusingly, domestic pigs. However, for wild boar, it applies to the whole species, including, for example, "wild boar sow" or "wild boar piglet".[4]

Physical characteristics

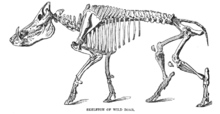

The body of the wild boar is compact; the head is large, the legs relatively short. The fur consists of stiff bristles and usually finer fur. The colour usually varies from dark grey to black or brown, but there are great regional differences in colour; even whitish animals are known from central Asia.[5] During winter the fur is much denser.

Adult boars average 120–180 cm in length and have a shoulder height of 90 cm.[6] As a whole, their average weight is 50–90 kg kilograms (110–200 pounds), though boars show a great deal of weight variation within their geographical ranges.[7] In central Italy their weight usually ranges from 80 to 100 kg; boars shot in Tuscany have been recorded to weigh 150 kg (331 lb). A French specimen shot in Negremont forest in Ardenne in 1999 weighed 227 kg (550 lb). Carpathian boars have been recorded to reach weights of 200 kg (441 lb), while Romanian and Russian boars can reach weights of 300 kg (661 lb).[6] Generally speaking, native Eurasian boars follow the Bergmann's rule, with smaller boars nearer the tropics and larger, smaller-eared boars in the North of their range.

The continuously growing tusks (the canine teeth) serve as weapons and tools. The lower tusks of an adult male measure about 20 cm (7.9 in) (from which seldom more than 10 cm (3.9 in) protrude out of the mouth), in exceptional cases even 30 cm (12 in). The upper tusks are bent upwards in males, and are regularly ground against the lower ones to produce sharp edges. In females they are smaller, and the upper tusks are only slightly bent upwards in older individuals.[citation needed]

Wild boar piglets are coloured differently from adults, being a soft[vague] brown with longitudinal darker stripes. The stripes fade by the time the piglet is about half-grown,[clarification needed] when the animal takes on the adult's grizzled grey or brown colour.

Litter size of wild boars may vary depending on their location. A study in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in the US reported a mean litter size of 3.3. A similar study on Santa Catalina Island, California reported a mean litter size of 5.[8] Larger litter sizes have been reported in Europe.[citation needed]

Behaviour/social structure

Adult males are usually solitary outside of the breeding season, but females and their offspring (both sub-adult males and females) live in groups called sounders. Sounders typically number around 20 animals, although groups of over 50 have been seen, and will consist of 2 to 3 sows; one of which will be the dominant female. Group structure changes with the coming and going of farrowing females, the migration of maturing males (usually when they reach around 20 months) and the arrival of unrelated sexually active males.

Wild boar are usually crepuscular, foraging from dusk until dawn but with resting periods during both night and day. They are omnivorous scavengers, eating almost anything they come across, including grass, nuts, berries, carrion, roots, tubers, refuse, insects and small reptiles. Wild boar are also known predators of young deer and lambs, reported in Australia.[9]

Boars are the only hoofed animals known to dig burrows.[citation needed]

If surprised or cornered, a boar (and particularly a sow with her piglets) can and will defend itself and its young with intense vigor.[citation needed] The male lowers its head, charges, and then slashes upward with his tusks. The female, whose tusks are not visible, charges with her head up, mouth wide, and bites. Such attacks are not often fatal to humans, but may result in severe trauma, dismemberment, or blood loss.

Reproduction

Sexual activity and testosterone production in males is triggered by decreasing day length, reaching a peak in mid-autumn. The normally solitary males then move into female groups and rival males fight for dominance, whereupon the largest and most dominant males achieve the most matings.

The age of puberty for sows ranges from 8 to 24 months of age depending on environmental and nutritional factors. Pregnancy lasts approximately 115 days and a sow will leave the group to construct a mound-like nest, 1–3 days before giving birth (farrowing).

The process of giving birth to a litter lasts between 2–3 hours and the sow and piglets remain in, or close to, the nest for 4–6 days. Sows rejoin the group after 4–5 days and the piglets will cross suckle between other lactating sows.

Litter size is typically 4-6 piglets but may be smaller for first litter, usually 2-3. The sex ratio at birth is 1:1. Piglets weigh between 750g - 1000g at birth. Rooting behaviour develops in piglets as early as the first few days of life and piglets are fully weaned after 3–4 months. They will begin to eat solid foods such as worms and grubs after about 2 weeks.[10]

Range

Reconstructed range

Wild boar were originally found in North Africa and much of Eurasia; from the British Isles to Korea and the Sunda Islands. The northern limit of its range extended from southern Scandinavia to southern Siberia and Japan. Within this range it was absent in extremely dry deserts and alpine zones.

A few centuries ago it was found in North Africa along the Nile valley up to Khartum and north of the Sahara. The reconstructed northern boundary of the range in Asia ran from Lake Ladoga (at 60°N) through the area of Novgorod and Moscow into the southern Ural, where it reached 52°N. From there the boundary passed Ishim and farther east the Irtysh at 56°N. In the eastern Baraba steppe (near Novosibirsk) the boundary turned steep south, encircled the Altai Mountains, and went again eastward including the Tannu-Ola Mountains and Lake Baikal. From here the boundary went slightly north of the Amur River eastward to its lower reaches at the China Sea. At Sachalin there are only fossil reports of wild boar. The southern boundaries in Europe and Asia were almost everywhere identical to the sea shores of these continents. In dry deserts and high mountain ranges, the wild boar is naturally absent. So it is absent in the dry regions of Mongolia from 44–46°N southward, in China westward of Sichuan and in India north of the Himalaya. In high altitudes of Pamir and Tien Shan they are also absent; however, at Tarim basin and on the lower slopes of the Tien Shan they do occur.[5]

Present range

In recent centuries, the range of wild boar has changed dramatically, largely due to hunting by humans and more recently because of captive wild boar escaping into the wild. For many years populations dwindled. They probably became extinct in Great Britain in the 13th century[12]. In Denmark the last boar was shot at the beginning of the 19th century, and in 1900 they were absent in Tunisia and Sudan and large areas of Germany, Austria and Italy. In Russia they were extinct in wide areas in the 1930s.

By contrast, during this period, a strong population of boar remained in France and Spain,[citation needed] despite being hunted for food and sport.

A revival of boar populations began in the middle of the last century. By 1950 wild boar had once again reached their original northern boundary in many parts of their Asiatic range. By 1960 they reached Saint Petersburg and Moscow, and by 1975 they were to be found in Archangelsk and Astrakhan. In the 1970s they again occurred in Denmark and Sweden, where captive animals escaped and now survive in the wild. (The wild boar population in Sweden was estimated to be around 80,000 in 2006 but is now considered to be in excess of 100,000). In the 1990s boar migrated into Tuscany in Italy. In England, wild boar populations re-established themselves in the 1990s, after escaping from specialist farms that had imported European stock.[12]

Elsewhere, in 1493, Christopher Columbus brought 8 hogs to the West Indies. Importation to the American mainland was in the mid 16th century by Hernan Cortes and Hernando de Soto, and in the mid 17th century by Sieur de La Salle. Pure Eurasian boar were also imported there for sport hunting in the early 20th century.[13] Sizeable populations of feral domestic pigs, closely related to wild boar, also live in Australia, New Zealand and North and South America.[14]

Status in Britain

Between their medieval extinction and the 1980s, when wild boar farming began, only a handful of captive wild boar, imported from the continent, were present in Britain. Occasional escapes of wild boar from wildlife parks have occurred as early as the 1970s, but since the early 1990s significant populations have re-established themselves after escapes from farms; the number of which has increased as the demand for wild boar meat has grown.

A 1998 MAFF (now DEFRA) study on wild boar living wild in Britain confirmed the presence of two populations of wild boar living in Britain; one in Kent/East Sussex and another in Dorset.[12] These allegedly arose as a result of damage to fences during the 1987 hurricane.[citation needed]

Another DEFRA report, in February 2008,[15] confirmed the existence of these two sites as 'established breeding areas' and identified a third in Gloucestershire/Herefordshire; in the Forest of Dean/Ross on Wye area. A 'new breeding population' was also identified in Devon.

Populations estimates were;

- The largest population, in Kent/East Sussex, was estimated at approximately 200 animals in the core distribution area.

- The second largest, in Gloucestershire/Herefordshire, was estimated to be in excess of 100 animals.

- The smallest, in west Dorset, was estimated to be fewer than 50 animals.

- Since winter 2005/6 significant escapes/releases have also resulted in animals colonising areas around the fringes of Dartmoor, in Devon. These are considered as an additional single 'new breeding population' and currently estimated to be up to 100 animals.

In December 2005 animal rights activists released about 100 boar from a farm at West Anstey, in Devon. Although some were recaptured many of these remained at large with boar accompanied by young being sighted some miles from the point of release in the following year, especially on the fringes of Exmoor.[citation needed] Some of these were filmed by local wildlife cameraman Johnny Kingdom and featured on his BBC TV programmes. [citation needed] Some have estimated this population at about 200 animals by late 2009.[citation needed]

The Forest of Dean population is believed to originate from one escape of boar of Eastern European origin in 1997 from a farm near Weston under Penyard, and another apparently deliberate release near Staunton in 2004. [citation needed].

Population estimates for the Forest of Dean are disputed, but in August 2010 the Forestry Commission estimated there were as many as 170 animals in the area.[16] A cull of 50 animals began in early 2010, with the aim of maintaining a population of around 90 animals.[17]

Two boar from the Forest of Dean population have qualified for Gold Medals under the Conseil International du Chasse (CIC) game trophy measurement system. The largest of these and the current UK record was shot near Ross on Wye in 2008 and scored 123.7 CIC points beating the previous record shot in the same area by 1.2 points. It had lower tusks of 23.9 cms and 23.1 cms in length and weighed about 240kgs.[citation needed]

There are also reports of wild boar from the Forest of Dean having crossed the River Wye into Monmouthshire, Wales.[18]. Many other sightings, across the UK, have also been reported.[19]

Wild boar farming in the UK

Captive wild boar in Britain are kept in private or public wildlife collections and in zoos, but exist predominantly on farms. Because wild boar are included in the Dangerous Wild Animals Act 1976, certain legal requirements have to be met prior to setting up a farm. A licence to keep boar is required from the local council, who will appoint a specialist to inspect the premises and report back to the council. Requirements include secure accommodation and fencing, correct drainage, temperature, lighting, hygiene, ventilation and insurance.

The original U.K. wild boar farm stock was mainly of French origin, but from 1987 onwards, farmers have supplemented the original stock with animals of both west European and east European origin. The east European animals were imported from farm stock in Sweden because Sweden, unlike eastern Europe, has a similar health status for pigs to that of Britain. Currently there is no central register listing all the wild boar farms in the UK; the total number of wild boar farms is unknown.[12]

Status in Germany

Recently, Germany has reported a surge in the wild boar population. According to one such study, "German wild boar litters have six to eight piglets on average, other countries usually only about four or five."[20]

Subspecies

Different subspecies can usually be distinguished by the relative lengths and shapes of their lacrimal bones. S. scrofa cristatus and S. scrofa vittatus have shorter lacrimal bones than European subspecies.[21] Spanish and French boar specimens have 36 chromosomes, as opposed to wild boar in the rest of Europe which possess 38, the same number as domestic pigs. Boars with 36 chromosomes have successfully mated with animals possessing 38, resulting in fertile offspring with 37 chromosomes.[22]

Four subspecies groups are generally recognized:[23]

Western races (scrofa group)

- Common Wild Boar Sus scrofa scrofa: The most common and most widespread subspecies, its original distribution ranges from France to European Russia. It has been introduced in Sweden, Norway, the USA and Canada.[6]

- Iberian Wild Boar Sus scrofa baeticus: A small subspecies present in the Iberian Peninsula.[6] Probably a junior synonym of S. s. meridionalis.[23]

- Castillian Wild Boar Sus scrofa castilianus: Larger than S. s. baeticus, it inhabits northern Spain.[6] Probably a junior synonym of S. s. scrofa.[23]

- Sardinian Wild Boar Sus scrofa meridionalis: A small, almost maneless subspecies from Corsica, Sardinia and Andalusia.[24]

- Italian Wild Boar Sus scrofa majori: A subspecies smaller than S. s. scrofa with a higher and wider skull. It occurs in central and southern Italy. Since the 1950s, it has hybridized extensively with introduced S. s. scrofa populations.[6]

- Sus scrofa attila: A very large, long-maned, yellowish subspecies from eastern Europe to Kazakhstan, northern Caucasus and Iran.[24]

- Barbary Wild Boar Sus scrofa algira: Maghreb in Africa. Closely related to, and sometimes considered a junior synonym of, S. s. scrofa, but smaller and with proportionally longer tusks.[11]

- Sus scrofa lybica: A small, pale and almost maneless subspecies from Caucasus to the Nile Delta, Turkey and the Balkans.[24]

- Sus scrofa sennaarensis: From Egypt and northern Sudan. Former presence in these countries, where became extinct around 1900, is linked to ancient introductions by man, and S. s. sennaarensis is probably a junior synonym of S. s. scrofa.[11][23] "Wild boars" now present in Sudan are derived from domestic pigs.[11]

- Sus scrofa nigripes: A light-coloured subspecies with dark legs from Tianshan Mountains, Central Asia.[24]

Indian races (cristatus group)

- Indian Wild Boar Sus scrofa cristatus: A long-maned subspecies with a coat that is brindled black unlike S. s. davidi.[24] More lightly built than European boar. Its head is larger and more pointed than that of the European boar, and its ears smaller and more pointed.[25] The plane of the forehead straight, while it is concave in the European.[25] Occurs from the Himalayas south to central India and east to Indochina (north of the Kra Isthmus).[24]

- Sus scrofa affinis: This subspecies is smaller than S. s. cristatus and found in southern India and Sri Lanka.[24] Validity questionable.[23]

- Sus scrofa davidi: A small, long-maned and light brown subspecies from eastern Iran to Gujarat; perhaps north to Tadjikistan.[24]

Eastern races (leucomystax group)

- Manchurian Wild Boar Sus scrofa ussuricus: A very large (largest subspecies of the wild boar), almost maneless subspecies with a thick coat that is blackish in the summer and yellowish-grey in the winter.[24] From Manchuria and Korea.[24]

- Japanese Wild Boar Sus scrofa leucomystax: A small, almost maneless, yellowish-brown subspecies from Japan (except Hokkaido where the wild boar is not naturally present, and the Ryuku Islands where replaced by S. s. riukiuanus).[24]

- Ryuku Wild Boar Sus scrofa riukiuanus: A small subspecies from the Ryuku Islands.[24]

- Formosan Wild Boar Sus scrofa taivanus: A small blackish subspecies from Taiwan.[24]

- Sus scrofa moupinensis: A relatively small and short-maned subspecies from most of China and Vietnam. There are significant variations within this subspecies, and it is possible there actually are several subspecies involved.[24]

- Siberian Wild Boar Sus scrofa sibiricus: A relatively small subspecies from Mongolia and Transbaikalia.[24]

Sundaic race (vittatus group)

- Banded pig Sus scrofa vittatus: A small, short-faced and sparsely furred subspecies with a white band on the muzzle.[24][26] From Peninsular Malaysia, and in Indonesia from Sumatra and Java east to Komodo.[24] Might be a separate species,[24] and shows some similarities with some other species of wild pigs in south-east Asia.

Domestic pig

The domestic pig is usually regarded as a further subspecies; Sus scrofa domestica - although sometimes classified as a separate species; Sus domestica.

Feral pigs

Domestic pigs quite readily become feral, and feral populations often revert to a similar appearance to wild boar; they can then be difficult to distinguish from natural or introduced true wild boar (with which they also readily interbreed). The characterization of populations as feral pig, escaped domestic pig or wild boar is usually decided by where the animals are encountered and what is known of their history. In New Zealand, for example, feral pigs are known as "Captain Cookers" from their supposed descent from liberations and gifts to Māori by explorer Captain James Cook in the 1770s.[27] New Zealand feral pigs are also frequently known as "tuskers", due to their appearance.

One characteristic by which domestic and feral animals are differentiated is their coats. Feral animals almost always have thick, bristly coats ranging in colour from brown through grey to black. A prominent ridge of hair matching the spine is also common, giving rise to the name razorback in the southern United States, where they are common. The tail is usually long and straight. Feral animals tend also to have longer legs than domestic breeds and a longer and narrower head and snout.

A very large swine dubbed Hogzilla was shot in Georgia, USA in June 2004.[28] Initially thought to be a hoax, the story became something of an internet sensation. National Geographic Explorer investigated the story, sending scientists into the field. After exhuming the animal and performing DNA testing, it was determined that Hogzilla was a hybrid of wild boar and domestic swine.[29] As of 2008[update], the estimated population of 4 million feral pigs caused an estimated US$800 million of property damage a year in the U.S.A[30]

At the beginning of the 20th century, wild boar were introduced for hunting in the United States, where they interbred in parts with free roaming domestic pigs. In South America, New Guinea, New Zealand, Australia and other islands, wild boar have also been introduced by humans and have partially interbred with domestic pigs.

In South America, also during the early 20th century, free-ranging boars were introduced in Uruguay for hunting purposes and eventually crossed the border into Brazil sometime during the 1990s, quickly becoming an invasive species, licensed private hunting of both feral boars and hybrids (javaporcos) being allowed from August 2005 on in the Southern Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul,[31] although their presence as a pest had been already noticed by the press as early as 1994.[32] Releases and escapes from unlicensed farms (established because of increased demand for boar meat as an alternative to pork), however, continued to bolster feral populations and by mid-2008 licensed hunts had to be expanded to the states of Santa Catarina and São Paulo.[33]

Recently established Brazilian boar populations are not to be confused with long established populations of feral domestic pigs (porcos monteiros), which have existed mainly in the Pantanal for more than a hundred years, along with native peccaries. The demographic dynamics of the interaction between feral pigs populations and those of the two native species of peccaries (Collared Peccary and White-lipped Peccary) is obscure and is being studied presently. It has been proposed that the existence of feral pigs could somewhat ease jaguar predation on peccary populations, as jaguars would show a preference for hunting pigs, when these are available.[34]

Natural predators

Wild boar are a main food source for tigers in the regions where they coexist. Tigers typically follow boar groups, and pick them off one by one. Tigers have been noted to chase boars for longer distances than with other prey, though they will usually avoid tackling mature male boars. In many cases, boars have gored tigers to death in self defense.[35]

Wolves are also major predators of boars in some areas. Wolves mostly feed on piglets, though adults have been recorded to be taken in Italy, the Iberian Peninsula and Russia. Wolves rarely attack boars head on, preferring to tear at their perineum, causing loss of coordination and massive blood loss. In some areas of the former Soviet Union, a single wolf pack can consume an average of 50–80 wild boars annually.[36] In areas of Italy where the two animals are sympatric, the extent to which boars are preyed upon by wolves has led to them developing more aggressive behaviour toward both wolves and domestic dogs.[6]

Striped hyenas occasionally feed on boars, though it has been suggested that only hyenas from the three larger subspecies present in Northwest Africa, the Middle East and India can successfully kill them.[37]

Young piglets are important prey for several species, including large snakes, such as the reticulated python, large birds of prey and various wild felids. Adults, due to their size, strength and defensive aggression, are generally avoided as prey. However, they have been taken additionally by mature leopards; large bears (mainly brown bears); and mature crocodiles. All predators of boars are opportunistic and would take piglets given the opportunity. Where introduced outside of their natural range, boars may be at the top of the food chain, but are also sometimes taken by predators similar to those in their native Eurasia.[7]

Commercial use

The hair of the boar was often used for the production of the toothbrush until the invention of synthetic materials in the 1930s.[38] The hair for the bristles usually came from the neck area of the boar. While such brushes were popular because the bristles were soft, this was not the best material for oral hygiene as the hairs were slow to dry and usually retained bacteria. Today's toothbrushes are made with plastic bristles.

Boar hair is used in the manufacture of boar-bristle hairbrushes, which are considered to be gentler on hair—and much more expensive—than common plastic-bristle hairbrushes. However, among shaving brushes, which are almost exclusively made with animal fibres, the cheaper models use boar bristles, while badger hair is used in much more expensive models.[39]

Boar hair is used in the manufacture of paintbrushes, especially those used for oil painting. Boar bristle paintbrushes are stiff enough to spread thick paint well, and the naturally split or "flagged" tip of the untrimmed bristle helps hold more paint.

Despite claims that boar bristles have been used in the manufacture of premium dart boards for use with steel-tipped darts, these boards are, in fact, made of other materials and fibres—the finest ones from sisal rope.

In many countries, boar are farmed for their meat, and in countries such as France and Italy, for example, boar (sanglier in French, "cinghiale" in Italian) may often be found for sale in butcher shops or offered in restaurants (although the consumption of wild boar meat has been linked to transmission of Hepatitis E in Japan).[40] In Germany, boar meat ranks among the highest priced types of meat and is as much part of high standard cuisine as venison.

Mythology, religion, history and fiction

In Greek mythology, two boars are particularly well known. The Erymanthian Boar was hunted by Heracles as one of his Twelve Labours, and the Calydonian Boar was hunted in the Calydonian Hunt by dozens of other mythological heroes, including some of the Argonauts and the huntress Atalanta. Ares, the Greek god of war, had the ability to transform himself into a wild boar, and even gored his son to death in this form to prevent the young man from growing too attractive and stealing his wife.[citation needed]

In Celtic mythology the boar was sacred to the Gallic goddess Arduinna,[41][42] and boar hunting features in several stories of Celtic and Irish mythology. One such story is that of how Fionn mac Cumhaill ("Finn McCool") lured his rival Diarmuid Ua Duibhne to his death—gored by a wild boar.

In the Asterix comic series set in Gaul, wild boar are the favourite food of Obelix whose immense appetite means that he can eat several roasted boar in a single sitting.

The Norse gods Freyr and Freyja both had boars. Freyr's boar was named Gullinbursti ("Golden Mane"), who was manufactured by the dwarf Sindri due to a bet between Sindri's brother Brokkr and Loki. The bristles in Gullinbursti's mane glowed in the dark to illuminate the way for his owner. Freya rode the boar Hildesvini (Battle Swine) when she was not using her cat-drawn chariot. According to the poem Hyndluljóð, Freyja concealed the identity of her protégé Óttar by turning him into a boar. In Norse mythology, the boar was generally associated with fertility.[citation needed]

In Persia (Iran) during the Sassanid Empire, boars were respected as fierce and brave creatures, and the adjective "Boraz (Goraz)" (meaning boar) was sometimes added to a person's name to show his bravery and courage. The famous Sassanid spahbod, Shahrbaraz, who conquered Egypt and the Levant, had his name derived Shahr(city) + Baraz(boar like/brave) meaning "Boar of the City".[citation needed]

In Hindu mythology, the third avatar of the Lord Vishnu was Varaha, a boar.

In Chinese horoscope the boar (sometimes also translated as pig), is one of the twelve animals of the zodiac, based on the legends about its creation, either involving Buddha or the Jade Emperor.[citation needed]

At least three Roman Legions are known to have had a boar as their emblems: Legio I Italica, Legio X Fretensis and Legio XX Valeria Victrix. X Fretensis was centrally involved in the First Jewish–Roman War, culminating with the destruction of Jerusalem and the Jewish Temple in 70 AD. In addition, it was stationed in Roman-occupied Judea for centuries and was involved in numerous other acts of oppression against the Jews. By one theory, resentment of this Legion's boar emblem, which came to be identified with extreme destruction and persecution, partly accounts for the deep-rooted traditional Jewish aversion for pork. (The Bible does not single out pigs in comparison with the many other unclean animals whose flesh is forbidden; nevertheless, in actual Jewish culture pigs are clearly singled out for a special, highly emotional loathing, of a kind not directed at other unclean animals).[43]

A boar is a long-standing symbol of the city of Milan, Italy. In Andrea Alciato's Emblemata (1584), beneath a woodcut of the first raising of Milan's city walls, a boar is seen lifted from the excavation. The foundation of Milan is credited to two Celtic peoples, the Bituriges and the Aedui, having as their emblems a ram and a boar respectively;[44] therefore "The city's symbol is a wool-bearing boar, an animal of double form, here with sharp bristles, there with sleek wool."[45] Alciato credits the most saintly and learned Ambrose for his account.[46]

In Medieval hunting the boar, like the hart, was a 'beast of venery', the most prestigious form of quarry. It was normally hunted by being harboured, or found by a 'limer', or bloodhound handled on a leash, before the pack of hounds were released to pursue it on its hot scent. In The poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight[47] a boar hunt is described, which depicts how dangerous the boar could be to the pack hounds, or raches, which hunted it.[48]

A story from Nevers, which is reproduced in the Golden Legend, states that one night Charlemagne dreamed he was about to be killed by a wild boar during a hunt, but was saved by the appearance of a child, who had promised to save the emperor if he would give him clothes to cover his nakedness. The bishop of Nevers interpreted this dream to mean that the child was Saint Cyricus and that he wanted the emperor to repair the roof of the Cathédrale Saint-Cyr-et-Sainte-Julitte de Nevers - which Charlemagne duly did.

The ancient Lowland Scottish Clan Swinton is said to have to have acquired the name Swinton for their bravery and clearing their area of Wild Boar. The chief's coat of arms and the clan crest allude to this legend, as is the name of the village of Swinewood in the county of Berwick which was granted to them in the 11th century.

Richard III (r. 1483–1485) used the white boar as his personal device and badge. It was also passed to his short-lived son, Edward.

Folklore, in the Forest of Dean, England, tells of a giant boar, known as the Beast of Dean, which terrorised villagers in the early 19th century.

Heraldry and other symbolic use

The wild boar and a boar's head are common charges in heraldry. It represents what are often seen as the positive qualities of the boar, namely courage and fierceness in battle. The arms of the Campbell of Possil family (see Carter-Campbell of Possil) include the head, erect and erased of a wild boar. The arms of the Swinton Family also possess wild boar, as does the coat of arms of the Purcell family [1]

See also

References

- ^ a b Template:IUCN2008 Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern.

- ^ Seward, Liz (4 September 2007). "Pig DNA reveals farming history". BBC News. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ^ http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/specialarticles/mam1_xx.pdf

- ^ "Taxonomy Browser: Sus Scrofa". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ^ a b V. G. Heptner and A. A. Sludskii: Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol. II, Part 2 Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats). Leiden, New York, 1989 ISBN 900408876 8 Cite error: The named reference "mammals of the soviet union" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f g Template:It iconScheggi, Massimo (1999). La Bestia Nera: Caccia al Cinghiale fra Mito, Storia e Attualità. p. 201. ISBN 8825379048.

- ^ a b http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Sus_scrofa.html

- ^ "Sus scrofa (Linnaeus, 1758)". Nis.gsmfc.org. 1999-08-30. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ^ http://www.britishwildboar.org.uk/wild%20boar%20action%20plan.pdf

- ^ http://www.britishwildboar.org.uk/profile.html

- ^ a b c d Kingdon, J. (1997). The Kingdon Guide to African Mammals. Academic Press Limited. ISBN 0-12-408355-2

- ^ a b c d http://www.britishwildboar.org.uk/britain.htm

- ^ http://www.suwanneeriverranch.com/wild-boar.htm

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/wildfacts/factfiles/598.shtml

- ^ http://www.defra.gov.uk/news/2008/080219b.htm

- ^ "Wild boar cull is given go ahead". 2010-01-04.

{{cite news}}: Text "http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-gloucestershire-11034307" ignored (help) - ^ http://www.thisisgloucestershire.co.uk/gloucestershireheadlines/Forest of Dean rangers battle to meet boar cull target/article-1667370-detail/article.html

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/wales/nature/sites/species/mammals/wild_boar.shtml

- ^ http://www.britishwildboar.org.uk/

- ^ "Numbers of wild boars surge | Oddly Enough". Reuters. 2008-10-03. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ^ Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1987). A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals. p. 208. ISBN 0521346975.

- ^ "Wild boar profile". Britishwildboar.org.uk. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ^ a b c d e Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Groves, C. (2008). Current views on the taxonomy and zoogeography of the genus Sus. Pp. 15-29 in Albarella, U., Dobney, K, Ervynck, A. & Rowley-Conwy, P. Eds. (2008). Pigs and Humans: 10,000 Years of Interaction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199207046

- ^ a b Natural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon, by Robert A. Sterndale

- ^ Francis, C. M. (2008). A Guide to the Mammals of Southeast Asia. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13551-9

- ^ Horwitz, Tony (2003). Blue Latitudes: Boldly Going Where Captain Cook Has Gone Before. Picador. p. 127. ISBN 0312422601.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Dewan, Shaila (2005-03-19). "DNA tests to reveal if possible record-size boar is a pig in a poke". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ^ "The Mystery of Hogzilla Solved". ABC News. 2005-03-21. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ^ Brick, Michael (2008-06-21). "Bacon a Hard Way: Hog-Tying 400 Pounds of Fury". The New York Times.

- ^ "www.institutohorus.org.br/download/marcos_legais/INSTRUCAO_NORMATIVA_N_71_04_agosto_2005.pdf" (PDF).

- ^ "Javali: fronteiras rompidas" ("Boars break across the border") Globo Rural 9:99, January 1994, ISSN 0102-6178, pgs.32/35

- ^ /www.arroiogrande.com/especiais_javali.htm

- ^ "Ciência Hoje On-line". Cienciahoje.uol.com.br. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ^ V.G Heptner & A.A. Sludskii. Mammals of the Soviet Union, Volume II, Part 2. ISBN 9004088768.

- ^ Graves, Will (2007). Wolves in Russia: Anxiety throughout the ages. p. 222. ISBN 1550593323.

- ^ "Striped Hyaena Hyaena (Hyaena) hyaena (Linnaeus, 1758)". IUCN Species Survival Commission Hyaenidae Specialist Group. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Dental Encyclopedia". 1800dentist.com. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ^ "Brush with Greatness". MenEssentials. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ^ Li T-C, Chijiwa K, Sera N, Ishibashi T, Etoh Y, Shinohara Y; et al. (2005). "Hepatitis E Virus Transmission from Wild Boar Meat". Emerg Infect Dis.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Celtic Encyclopaedia". Isle-of-skye.org.uk. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ^ "les-ardennes.net". Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ^ For example Berl Katznelson, a major ideologue of Socialist Zionism and not a religious person himself, spoke out very vehemently against the eating of pork and called for it to be forbidden in the future Jewish state—which was not his position about other kinds of meat forbidden by the Jewish religion

- ^ Bituricis vervex, Heduis dat sucula signum.

- ^ Laniger huic signum sus est, animálque biforme, Acribus hinc setis, lanitio inde levi.

- ^ "Alciato, ''Emblemata'', Emblema II". Emblems.arts.gla.ac.uk. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ^ Anonymous (c1350). Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ The Meaning and Symbolism of the Hunting Scenes in Sir Gawain and The Green Knight