Nomadic empire

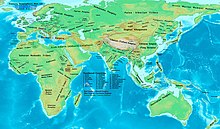

Nomadic empires, sometimes also called steppe empires, Central or Inner Asian empires, are the empires erected by the bow-wielding, horse-riding, nomadic peoples in the Eurasian steppe, from classical antiquity (Scythia) to the early modern era (Dzungars). They are the most prominent example of non-sedentary polities.

Some nomadic empires operated by establishing a capital city inside a conquered sedentary state, and then by exploiting the existing bureaucrats and commercial resources of that non-nomadic society. As the pattern is repeated, the originally nomadic dynasty becomes culturally assimilated to the culture of the occupied nation before it is ultimately overthrown.[1] Ibn Khaldun described a similar cycle on a smaller scale in his Asabiyyah theory. A term used for these polities in the early medieval period is khanate (after khan, the title of their rulers), and after the Mongol conquests also as orda (horde) as in Golden Horde.

Antiquity

Cimmeria

The Cimmerians were an ancient Indo-European people living north of the Caucasus and the Sea of Azov as early as 1300 BCE until they were driven southward by the Scythians into Anatolia during the 8th century BC. Linguistically they are usually regarded as Iranian, or possibly Thracian with an Iranian ruling class.

- The Pontic-Caspian steppe: southern Russia and Ukraine until 7th century BCE.

- The northern Caucasus area, including Georgia and modern day Azerbaijan

- Central, East and North Anatolia 714–626 BCE.

Scythia

Scythia (/ˈsɪθiə/; Ancient Greek: Σκυθική) was a region of Central Eurasia in classical antiquity, occupied by the Eastern Iranian Scythians,[2][3][4] encompassing parts of Eastern Europe east of the Vistula River and Central Asia, with the eastern edges of the region vaguely defined by the Greeks.[citation needed] The Ancient Greeks gave the name Scythia (or Great Scythia) to all the lands north-east of Europe and the northern coast of the Black Sea.[5] The Scythians – the Greeks' name for this initially nomadic people – inhabited Scythia from at least the 11th century BC to the 2nd century AD.[6]

Sarmatia

The Sarmatians (Latin: Sarmatæ or Sauromatæ, Greek: Σαρμάται, Σαυρομάται) were a large confederation[7] of Iranian people during classical antiquity,[8][9] flourishing from about the 6th century BC to the 4th century AD.[10] They spoke Scythian, an Indo-European language from the Eastern Iranian family. According to authors Arrowsmith, Fellowes and Graves Hansard in their book A Grammar of Ancient Geography published in 1832, Sarmatia had two parts, Sarmatia Europea [11] and Sarmatia Asiatica [12] covering a combined area of 503,000 sq mi or 1,302,764 km2.

Xiongnu

The Xiongnu were a confederation of nomadic tribes from Central Asia with a ruling class of unknown origin and other subjugated tribes. They lived on the Mongolian Plateau between the 3rd century BC and the 460s AD, their territories including modern day Mongolia, southern Siberia, western Manchuria, and the modern Chinese provinces of Inner Mongolia, Gansu, and Xinjiang. The Xiongnu was the first unified empire of nomadic peoples. Relations between early Chinese dynasties and the Xiongnu were complicated and included military conflict, exchanges of tribute and trade, and marriage treaties. They were considered so dangerous and disruptive that the Qin Dynasty ordered the construction of the Great Wall to protect China from Xiongnu attacks.

Kushan Empire

The Kushan Empire (Template:Lang-xbc, Kushano; Template:Lang-sa Kuṣāṇ Rājavaṃśa; BHS: Guṣāṇa-vaṃśa; Template:Lang-xpr Kušan-xšaθr[13]) was a syncretic empire, formed by Yuezhi, in the Bactrian territories in the early 1st century. It spread to encompass much of Afghanistan,[14] and then the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent at least as far as Saketa and Sarnath near Varanasi (Benares), where inscriptions have been found dating to the era of the Kushan emperor Kanishka the Great.[15]

Xianbei

The Xianbei state or Xianbei confederation was a nomadic empire which existed in modern-day Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, northern Xinjiang, Northeast China, Gansu, Buryatia, Zabaykalsky Krai, Irkutsk Oblast, Tuva, Altai Republic and eastern Kazakhstan from 156–234 AD. Like most ancient peoples known through Chinese historiography, the ethnic makeup of the Xianbei is unclear.[16] The Xianbei were a northern branch of the earlier Donghu and it is likely at least some were proto-Mongols.[17]

Hephthalite Empire

The Hephthalites, Ephthalites, Ye-tai, White Huns, or, in Sanskrit, the Sveta Huna, were a confederation of nomadic and settled[18] people in Central Asia who expanded their domain westward in the 5th century.[19] At the height of its power in the first half of the 6th century, the Hephthalite Empire controlled territory in present-day Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, India and China.[10][20]

Hunnic Empire

The Huns were a confederation of Eurasian tribes from the Steppes of Central Asia. Appearing from beyond the Volga River some years after the middle of the 4th century, they conquered all of eastern Europe, ending up at the border of the Roman Empire in the south, and advancing far into modern day Germany in the north. Their appearance in Europe brought with it great ethnic and political upheaval and may have stimulated the Great Migration. The empire reached its largest size under Attila between 447 and 453.

Mongolic people and Turkic expansion

Rouran

The Rouran (柔然), Juan Juan (蠕蠕), or Ruru (茹茹) were a confederation of Mongolic speaking[21] nomadic tribes on the northern borders of China from the late 4th century until the late 6th century. They controlled the area of Mongolia from the Manchurian border to Turpan and, perhaps, the east coast of Lake Balkhash, and from the Orkhon River to China Proper.

Göktürks

The Göktürks or Kök-Türks were a Turkic people of ancient North and Central Asia and northwestern China. Under the leadership of Bumin Khan and his sons they established the first known Turkic state around 546, taking the place of the earlier Xiongnu as the main power in the region. They were the first Turkic tribe to use the name "Türk" as a political name. The empire was split into a western and an eastern part around 600, merged again 680, and finally declined after 734.

Uyghurs

The Uyghur Empire was a Turkic empire that existed in present-day Mongolia and surrounding areas for about a century between the mid 8th and 9th centuries. It was a tribal confederation under the Orkhon Uyghur nobility. It was established by Kutlug I Bilge Kagan in 744, taking advantage of the power vacuum in the region after the fall of the Gökturk Empire. It collapsed after a Kyrgyz invasion in 840.

Middle Ages

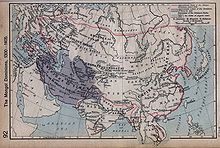

Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire was the largest contiguous land empire in history at its peak, with an estimated population of over 100 million people. The Mongol Empire was founded by Genghis Khan in 1206, and at its height, it encompassed the majority of the territories from Southeast Asia to Eastern Europe.

After unifying the Mongol–Turkic tribes, the Empire expanded through conquests throughout continental Eurasia. During its existence, the Pax Mongolica facilitated cultural exchange and trade on the Silk Route between the East, West, and the Middle East in the period of the 13th and 14th centuries. It had significantly eased communication and commerce across Asia during its height.[22][23]

After the death of Möngke Khan in 1259, the empire split into four parts (Yuan dynasty, Ilkhanate, Chagatai Khanate and Golden Horde), each of which was ruled by its own Khan, though the Yuan rulers had nominal title of Khagan. After the disintegration of the western khanates and the fall of the Yuan dynasty in China in 1368, the empire finally broke up.

Timurid Empire

The Timurids, self-designated Gurkānī, were a Turko-Mongol dynasty, established by the warlord Timur in 1370 and lasting until 1506. At its zenith, the Timurid Empire included the whole of Central Asia, Iran and modern Afghanistan, as well as large parts of Mesopotamia and the Caucasus.

Later Mongol khanates

Later Mongol khanates such as the Northern Yuan dynasty based in Mongolia and the Dzungar Khanate based in Xinjiang were also nomadic empires. Right after the fall of the Yuan dynasty in 1368, the succeeding Ming dynasty established by Han Chinese rebuilt the Great Wall, which had been begun many hundreds of years earlier to keep the northern nomads out of China proper. During the subsequent centuries the Mongols, who were then based in Mongolia as the Northern Yuan dynasty, tended to continue their independent, nomadic way of life as much as possible.[24] On the other hand, the Dzungars were a confederation of several Oirat tribes who formed and maintained the last horse archer empire from the early 17th century to the middle 18th century. They emerged in the early 17th century to fight the Altan Khan of the Khalkha, the Jasaghtu Khan and their Manchu patrons for dominion and control over the Mongolian people and territories. In 1756 this last nomadic power was dissolved due to the Oirat princes' succession struggle and costly war with the Qing dynasty.

Popular misconceptions

The Qing dynasty is mistakenly confused as a nomadic empire by people who wrongly think that the Manchus were a nomadic people,[25] when in fact they were not nomads,[26][27] but instead were a sedentary agricultural people who lived in fixed villages, farmed crops, practiced hunting and mounted archery.

The Sushen used flint headed wooden arrows, farmed, hunted, and fished, and lived in caves and trees.[28] The cognates Sushen or Jichen (稷真) again appear in the Shan Hai Jing and Book of Wei during the dynastic era referring to Tungusic Mohe tribes of the far northeast.[29] The Mohe enjoyed eating pork, practiced pig farming extensively, and were mainly sedentary,[30] and also used both pig and dog skins for coats. They were predominantly farmers and grew soybean, wheat, millet, and rice, in addition to engaging in hunting.[31]

The Jurchens were sedentary,[32][33] settled farmers with advanced agriculture. They farmed grain and millet as their cereal crops, grew flax, and raised oxen, pigs, sheep, and horses.[34] Their farming way of life was very different from the pastoral nomadism of the Mongols and the Khitan on the steppes.[35][36] "At the most", the Jurchen could only be described as "semi-nomadic" while the majority of them were sedentary.[37]

The Manchu way of life (economy) was described as agricultural, farming crops and raising animals on farms.[38] Manchus practiced Slash-and-burn agriculture in the areas north of Shenyang.[39] The Haixi Jurchens were "semi-agricultural, the Jianzhou Jurchens and Maolian (毛怜) Jurchens were sedentary, while hunting and fishing was the way of life of the "Wild Jurchens".[40] Han Chinese society resembled that of the sedentary Jianzhou and Maolian, who were farmers.[41] Hunting, archery on horseback, horsemanship, livestock raising, and sedentary agriculture were all practiced by the Jianzhou Jurchens as part of their culture.[42] In spite of the fact that the Manchus practiced archery on horse back and equestrianism, the Manchu's immediate progenitors practiced sedentary agriculture.[43] Although the Manchus also partook in hunting, they were sedentary.[44] Their primary mode of production was farming while they lived in villages, forts, and towns surrounded by walls. Farming was practiced by their Jurchen Jin predecessors.[45][46]

“建州毛怜则渤海大氏遗孽,乐住种,善缉纺,饮食服用,皆如华人,自长白山迤南,可拊而治也。" "The (people of) Chien-chou and Mao-lin [YLSL always reads Mao-lien] are the descendants of the family Ta of Po-hai. They love to be sedentary and sow, and they are skilled in spinning and weaving. As for food, clothing and utensils, they are the same as (those used by) the Chinese. (Those living) south of the Ch'ang-pai mountain are apt to be soothed and governed."

— 据魏焕《皇明九边考》卷二《辽东镇边夷考》[47] Translation from Sino-J̌ürčed relations during the Yung-Lo period, 1403–1424 by Henry Serruys[48]

For political reasons, the Jurchen leader Nurhaci chose variously to emphasize either differences or similarities in lifestyles with other peoples like the Mongols.[49] Nurhaci said to the Mongols that "The languages of the Chinese and Koreans are different, but their clothing and way of life is the same. It is the same with us Manchus (Jušen) and Mongols. Our languages are different, but our clothing and way of life is the same." Later Nurhaci indicated that the bond with the Mongols was not based in any real shared culture. It was for pragmatic reasons of "mutual opportunism", since Nurhaci said to the Mongols: "You Mongols raise livestock, eat meat and wear pelts. My people till the fields and live on grain. We two are not one country and we have different languages."[50]

Further reading

- Amitai, Reuven; Biran, Michal (editors). Mongols, Turks, and others: Eurasian nomads and the sedentary world (Brill's Inner Asian Library, 11). Leiden: Brill, 2005 (ISBN 90-04-14096-4).

- Drews, Robert. Early riders: The beginnings of mounted warfare in Asia and Europe. N.Y.: Routledge, 2004 (ISBN 0-415-32624-9).

- Grousset, Rene. The Empire of the Steppes: a History of Central Asia, Naomi Walford, (tr.), New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1970.

- Hildinger, Erik. Warriors of the steppe: A military history of Central Asia, 500 B.C. to A.D. 1700. New York: Sarpedon Publishers, 1997 (hardcover, ISBN 1-885119-43-7); Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2001 (paperback, ISBN 0-306-81065-4).

- Kradin, Nikolay. Nomadic Empires: Origins, Rise, Decline. In Nomadic Pathways in Social Evolution. Ed. by N.N. Kradin, Dmitri Bondarenko, and T. Barfield (p. 73–87). Moscow: Center for Civilizational Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, 2003.

- Kradin, Nikolay. Nomads of Inner Asia in Transition. Moscow: URSS, 2014 (ISBN 978-5-396-00632-4).

See also

- Thalassocracy

- List of Mongol states

- Mongol and Tatar states in Europe

- List of Turkic dynasties and countries

- Eurasian nomads

- Inner Asia

- History of Central Asia

- Military history of Asia

References

- ^ Golden, Peter B. (1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State Formation in the Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East. Southgate Publishers. p. 75.

- ^ "Scythian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ "Scythia". Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ "The Scythians". history-world.org.

- ^ "Scythia", Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854), William Smith, LLD, Ed.

- ^ Lessman, Thomas. "World History Maps". 2004. Thomas Lessman. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ Sinor 1990, p. 113

- ^ "Sarmatian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ Waldman & Mason 2006, pp. 692–694

- ^ a b J.Harmatta: "Scythians" in UNESCO Collection of History of Humanity – Volume III: From the Seventh Century BC to the Seventh Century AD. Routledge/UNESCO. 1996. pg. 182 Cite error: The named reference "UNESCO" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Arrowsmith, Fellowes, Hansard, A, B & G L (1832). A Grammar of Ancient Geography,: Compiled for the Use of King's College School (3 April 2006 ed.). Hansard London. p. 9. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arrowsmith, Fellowes, Hansard, A, B & G L (1832). A Grammar of Ancient Geography,: Compiled for the Use of King's College School (3 April 2006 ed.). Hansard London. p. 15. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Dynasty Arts of the Kushans, University of California Press, 1967, p. 5

- ^ http://www.kushan.org/general/other/part1.htm and Si-Yu-Ki, Buddhist Records of the Western World, (Tr. Samuel Beal: Travels of Fa-Hian, The Mission of Sung-Yun and Hwei-S?ng, Books 1–5), Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd. London. 1906 and Hill (2009), pp. 29, 318–350

- ^ which began about 127 CE. "Falk 2001, pp. 121–136", Falk (2001), pp. 121–136, Falk, Harry (2004), pp. 167–176 and Hill (2009), pp. 29, 33, 368–371.

- ^ Wyatt 2004, p. 8.

- ^ Chen, Sanping (1996). "A-Gan Revisited — The Tuoba's Cultural and Political Heritage". Journal of Asian History. 30 (1): 46–78. JSTOR 41931010.

- ^ Prokopios, Historien I 3,2–7.

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 67–72. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ West 2009, pp. 274–277

- ^ William Montgomery McGovern – early empires of Central Asia ,p. 421

- ^ Gregory G.Guzman – the barbarians a negative or positive factor in ancient and medieval history?, The historian 50 (1988), 568–70

- ^ Thomas T.Allsen – and conquest in Mongol Eurasia, 211

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania, by Barbara A. West, p. 558

- ^ Pamela Crossley, The Manchus, p. 3

- ^ Patricia Buckley Ebrey et al., East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, 3rd edition, p. 271

- ^ Frederic Wakeman, Jr., The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in the Seventeenth Century, p. 24, note 1

- ^ Huang 1990 p. 246.

- ^ "逸周書". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Gorelova 2002, pp. 13–4.

- ^ Gorelova 2002, p. 14.

- ^ Williamson 2011.

- ^ Vajda.

- ^ Sinor 1996, p. 416.

- ^ Twitchett, Franke, Fairbank 1994, p. 217.

- ^ de Rachewiltz 1993, p. 112.

- ^ Breuker 2010, p. 221.

- ^ Wurm 1996, p. 828.

- ^ Reardon-Anderson 2000, p. 504.

- ^ Mote, Twitchett & Fairbank 1988, p. 266.

- ^ Twitchett & Mote 1998, p. 258.

- ^ Rawski 1996, p. 834.

- ^ Rawski 1998, p. 43.

- ^ Allsen 2011, p. 215.

- ^ Transactions, American Philosophical Society (vol. 36, Part 1, 1946). American Philosophical Society. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-1-4223-7719-2.

- ^ Karl August Wittfogel; Chia-shêng Fêng (1949). History of Chinese Society: Liao, 907-1125. American Philosophical Society. p. 10.

- ^ 萧国亮 (2007-01-24). "明代汉族与女真族的马市贸易". 艺术中国(ARTX.cn). p. 1. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ Serruys 1955, p. 22.

- ^ Perdue 2009, p. 127.

- ^ Peterson 2002, p. 31.