Operation Flash

| Operation Flash | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Croatian War of Independence | |||||||||

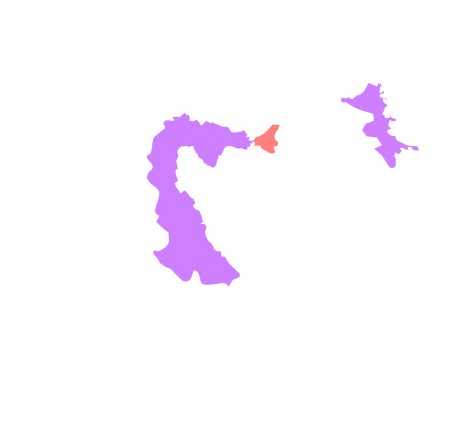

Map of Operation Flash | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 7,200 | 3,500 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

42 killed 162 wounded |

188–283 killed (military and civilians) 1,200 wounded 2,100 captured | ||||||||

|

11,500–15,000 Croatian Serb refugees 3 UN peacekeepers wounded | |||||||||

Operation Flash (Serbo-Croatian: Operacija Bljesak/Операција Бљесак) was a brief Croatian Army (HV) offensive conducted against the forces of the self-declared proto-state Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK) from 1–3 May 1995. The offensive occurred in the later stages of the Croatian War of Independence and was the first major confrontation after ceasefire and economic cooperation agreements were signed between Croatia and the RSK in 1994. The last organised RSK resistance formally ceased on 3 May, with the majority of troops surrendering the next day near Pakrac, although mop-up operations continued for another two weeks.

Operation Flash was a strategic victory for Croatia resulting in the capture of a 558-square-kilometre (215 sq mi) salient held by RSK forces centred in and around the town of Okučani. The town, which sat astride the Zagreb–Belgrade motorway and railroad, had presented Croatia with significant transport problems between the nation's capital Zagreb and the eastern region of Slavonia as well as between non-contiguous territories held by the RSK. The area was a part of United Nations Confidence Restoration Operation (UNCRO) Sector West under the United Nations Security Council peacekeeping mandate in Croatia. The attacking force consisted of 7,200 HV troops, supported by the Croatian special police, arrayed against approximately 3,500 RSK soldiers. In response to the operation, the RSK military bombarded Zagreb and other civilian centres, causing seven fatalities and injuries to 205.

Forty-two HV soldiers and Croatian policemen were killed in the attack and 162 wounded. RSK casualties are disputed—Croatian authorities cited the deaths of 188 Serb soldiers and civilians with an estimated 1,000–1,200 wounded. Serbian sources, on the other hand, claimed that 283 Serb civilians were killed, contrary to the 83 reported by the Croatian Helsinki Committee. It is estimated that out of 14,000 Serbs living in the region, two-thirds fled immediately with more following in subsequent weeks. By the end of June, it is estimated that only 1,500 Serbs remained. Subsequently, the personal representative of the Secretary-General of the United Nations Yasushi Akashi criticised Croatia for "mass violations" of human rights, but his statements were refuted by the Human Rights Watch and to some extent by the United Nations Commission on Human Rights rapporteur Tadeusz Mazowiecki.

Background

[edit]

The 1990 revolt of the Croatian Serbs was centred on the predominantly Serb-populated areas of the Dalmatian hinterland around Knin,[1] parts of the Lika, Kordun, Banovina regions and in eastern Croatian settlements with significant Serb populations,[2] as well as parts of western Slavonia centred on Pakrac and Okučani.[3] In the early stages of the Log Revolution, tens of thousands of Serbs fled from Croatian controlled cities,[4] leading to the formation of a single political entity known as the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK). The RSK's proclaimed intention to integrate politically with Serbia was viewed by the Croatian Government as an act of rebellion.[5] By March 1991, the conflict had escalated to war—the Croatian War of Independence.[6] In June 1991, with the breakup of Yugoslavia, Croatia declared its independence,[7] which came into effect on 8 October[8] after a three-month moratorium.[9] From late October to late December 1991, the HV conducted Operations Otkos 10 and Orkan 91 recapturing 60% of RSK-occupied western Slavonia,[10] resulting in Serbs fleeing from the area,[11] while some were killed in a death camp in Pakračka Poljana.[12] A campaign of ethnic cleansing was then initiated by the RSK against Croatian civilians and most non-Serbs were expelled by early 1993.[13] After the end of the war, thousands of civilians murdered by the Serb troops were exhumed from mass graves.[14]

As the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) increasingly supported the RSK and the Croatian Police was unable to cope with the situation, the Croatian National Guard (ZNG) was formed in May 1991. The ZNG was renamed the Croatian Army (HV) in November.[15] The establishment of the military of Croatia was hampered by a United Nations (UN) arms embargo introduced in September.[16] The final months of 1991 saw the fiercest fighting of the war, culminating in the Battle of the barracks,[17] the Siege of Dubrovnik,[18] and the Battle of Vukovar.[19] The western Slavonia area became the scene of a JNA offensive in September and October aimed at severing all transport links between the Croatian capital, Zagreb, and Slavonia. Even though the HV managed to reclaim much territory gained by the JNA advance in operations Otkos 10 and Orkan 91, it failed to secure the Zagreb–Belgrade motorway and railroad significant for the defence of Slavonia.[3]

In January 1992, the Sarajevo Agreement was signed by representatives of Croatia, the JNA and the UN, and fighting between the two sides was paused.[20] Ending the series of unsuccessful ceasefires, United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) was deployed to Croatia to supervise and maintain the agreement.[21] The conflict largely passed on to entrenched positions and the JNA soon retreated from Croatia into Bosnia and Herzegovina, where a new conflict was anticipated,[20] but Serbia continued to support the RSK.[22] HV advances restored small areas to Croatian control—through Operation Maslenica.[23] and as the siege of Dubrovnik was lifted.[24] Croatian towns and villages were intermittently attacked by artillery,[25] or missiles.[2][26] Cities in the RSK were also fired on by Croatian forces.[27] The Republika Srpska, Serb-held territory in Bosnia and Herzegovina, was involved in the war in a limited capacity, through military and other aid to the RSK, occasional air raids launched from Banja Luka, and most significantly through artillery attacks against several cities.[28][29] The HV deployed to Bosnia and Herzegovina, especially in a campaign against the Bosnian Serbs. The intervention was formalized on 22 July 1995, when Croatian President Franjo Tuđman and the Bosnian president, Alija Izetbegović, signed Split Agreement on mutual defence, permitting the large-scale deployment of the HV in Bosnia and Herzegovina,[30] that drove back Bosnian Serb forces and came within striking distance of Banja Luka.[31]

Prelude

[edit]The March 1994 Washington Agreement,[32] ended the Croat–Bosniak War and created conditions for provision of US military aid to Croatia.[33] Croatia requested US military advisors from the Military Professional Resources Incorporated (MPRI) to provide training of civil-military relations, programme and budget services of the HV the same month,[34] and the MPRI training was licensed by the US Department of State upon endorsement from Richard Holbrooke in August.[35] The MPRI was hired because the UN arms embargo was still in place, ostensibly to prepare the HV for NATO Partnership for Peace programme participation. They trained HV officers and personnel for 14 weeks from January to April 1995. It was also speculated that the MPRI also provided doctrinal advice, scenario planning and US government satellite information to Croatia.[36] MPRI and Croatian officials dismissed such speculation.[37][38] In November 1994, the United States unilaterally ended the arms embargo against Bosnia and Herzegovina,[39] in effect allowing the HV to supply itself as 30% of arms and ammunition shipped through Croatia was kept as a trans-shipment fee.[40][41] The US involvement reflected a new military strategy endorsed by Bill Clinton since February 1993.[42]

In 1994, the United States, Russia, the European Union (EU) and the UN sought to replace the 1992 peace plan drafted by Cyrus Vance, Special Envoy of the UN Secretary-General, which brought in the UNPROFOR. They formulated the Z-4 plan giving Serb-majority areas in Croatia substantial autonomy.[43] After numerous and often uncoordinated development of the plan, including leaking of its draft elements to the press in October, the Z-4 plan was presented on 30 January 1995. Neither Croatia nor the RSK liked the plan. Croatia was concerned that the RSK might accept it, but Croatian President Franjo Tuđman realised that Slobodan Milošević, who would ultimately make the decision for the RSK,[44] would not accept the plan for fear that it would set a precedent for a political settlement in Kosovo—allowing Croatia to accept the plan with little possibility for it to be implemented.[43] The RSK refused to receive, let alone accept the plan.[45]

In December 1994, Croatia and the RSK made an economic agreement to restore road and rail links, water and gas supplies and use of a part of the Adria oil pipeline. Even though a part of the agreement was never implemented,[46] the pipeline and a 23.2-kilometre (14.4 mi) section of the Zagreb–Belgrade motorway passing through RSK territory around Okučani were opened,[47][48] shortening travel from the capital to Slavonia by several hours. Since its opening, the motorway section became of strategic importance both to Croatia and the RSK in further negotiations. The section was closed by the RSK for 24 hours on 24 April,[49] in response to increased control of commercial traffic leaving the RSK held territory in the eastern Slavonia—likely increasing Croatian resolve to capture the area through military action.[50] The controls were put in place by the United Nations Security Council Resolution 981 of 31 March 1995, establishing the United Nations Confidence Restoration Operation (UNCRO) peacekeeping force instead of UNPROFOR, and tasked the force with monitoring of Croatian international borders separating the RSK-held territory from Yugoslavia or Bosnia and Herzegovina,[51] as well as facilitating the latest Croatia–RSK ceasefire of 29 March 1994, and the December 1994 economic agreement.[52]

The situation worsened again on 28 April, when a Serb was stabbed by a Croat refugee—both of them living in the same village before 1991—at a filling station adjacent to the motorway, situated in Croatian controlled territory near Nova Gradiška.[53] In response, a group of Serbs, including a brother of the killed man, fired on vehicles on the motorway which remained open despite a UNCRO request to Croatia to close the route. Three civilians were killed in the shooting and RSK soldiers arrested five.[54] The shooting stopped by 1 am,[55] and the five were released in the morning and the UNCRO demanded that the motorway be reopened. The RSK 18th Corps and the chief of police in Okučani declined on instructions from the RSK leadership in Knin, but later agreed to reopen the road on 1 May at 6 am. However, the decision to reopen the motorway was cancelled on 30 April at 8 pm.[56] The same night, three rocket-propelled grenades were fired into the Croatian-controlled part of Pakrac and a vehicle was attacked on the Pakrac–Požega road located close to RSK positions,[57] the latter resulting in one dead and one captured civilian.[58] Hrvoje Šarinić, an advisor to Tuđman, confirmed that Croatia contemplated staging an incident which would provoke a military capture of the motorway area, but he also denied that one was needed as incidents were known to occur on a regular basis.[59]

Order of battle

[edit]The HV General Staff developed a plan to capture the RSK-held area of western Slavonia in December 1994. The forces were set to converge on Okučani, advancing east from Novska and west from Nova Gradiška, isolating RSK forces remaining north of the line while they are pinned down by reserve infantry brigades and Home Guard regiments. A part of the main force would secure the area south of the main axis of the attack, reaching the Sava River in order to prevent any reinforcements sent by the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) from reaching the area. The plan included Croatian Air Force (CAF) air strikes on the only Sava River bridge in the area, located between Stara Gradiška and Gradiška. In the second phase of the offensive, a mop-up operation was designed to eliminate any pockets of resistance left over.[60] The HV General Staff and the HV Bjelovar Corps performed a full-scale staff and field rehearsal for Operation Flash in February.[61] The operation was directed by the Bjelovar Corps commanded by Brigadier Luka Džanko, although the HV General Staff set up three forward command posts to allow rapid reaction by Lieutenant General Zvonimir Červenko.[60] The primary posts were in Novska and Nova Gradiška, under control of Major General Ivan Basarac and Lieutenant General Petar Stipetić respectively.[62] At the time, Červenko was acting chief of the General Staff as General Janko Bobetko was hospitalized in Zagreb.[60]

Croatia deployed 7,200 troops to conduct the attack, including elements of three guards brigades and an independent guards battalion supported by special forces of the Croatian Police and reserve HV and Home Guard troops.[63] The 18th West Slavonian Corps of the RSK, defending the area, was expected to have 4,773 troops at its disposal,[64] as it ordered mobilization of the troops on 28–29 April.[65] The move brought the 18th Corps, commanded by Colonel Lazo Babić,[66] to strength of about 4,500 troops.[67][68] An RSK commission set up to evaluate the battle claimed that some of the RSK units were not able to retrieve antitank weapons from UNCRO depots in Stara Gradiška and near Pakrac until after the offensive began. The weapons were stored there pursuant to the March 1994 ceasefire agreement.[69] Nonetheless, the UNCRO did not resist the RSK troops removing the stored weapons.[70]

| Corps | Unit | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Bjelovar Corps | elements of the 1st Croatian Guards Brigade | In Novska area |

| 2nd Battalion of the 1st Guards Brigade | ||

| 1st Battalion of the 3rd Guards Brigade | ||

| 125th Home Guard Regiment | ||

| Special police (1 battalion size) | ||

| 1 artillery rocket battalion of the 2nd Guards Brigade | ||

| 1 artillery rocket battalion of the 3rd Guards Brigade | ||

| 2nd Battalion of the 16th Artillery Rocket Brigade | ||

| 4th Battalion of the 5th Guards Brigade | In Nova Gradiška area | |

| 81st Guards Battalion | ||

| 121st Home Guard Regiment | ||

| 265th Reconnaissance Sabotage Company | ||

| 1 armoured company of the 123rd Infantry Brigade | ||

| Special police (1 battalion size) | ||

| 1st Battalion of the 16th Artillery Rocket Brigade | ||

| 18th Artillery Battalion | ||

| 52nd Infantry Brigade | In Pakrac area | |

| 105th Infantry Brigade | ||

| Special police (1 battalion size) | ||

| 15th Artillery Rocket Brigade | Corps-level support[72] |

| Corps | Unit | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 18th Western Slavonian Corps | 98th Infantry Brigade | In Novska area |

| 54th Infantry Brigade | In Okučani area, opposite Nova Gradiška | |

| 51st Infantry Brigade | In Pakrac area | |

| 59th Infantry Detachment | ||

| 63rd Infantry Detachment | ||

| Special police battalion | ||

| Tactical group 1 | In Jasenovac area | |

| 4 batteries of supporting artillery | In part located south of the Sava river, in the Republika Srpska[74] |

Timeline

[edit]1 May

[edit]

On 1 May 1995, Šarinić informed UNCRO of the imminent HV offensive in a telephone call to the Canadian general Raymond Crabbe at 4 am designed to let the UNCRO troops seek shelter in time.[67] Operation Flash started through an artillery preparatory bombardment of RSK held positions at 4:30 am. Infantry and armour attacks converging from Novska, Nova Gradiška and Pakrac at Okučani and an attack from Novska towards Jasenovac commenced at various times between 5:30 and 7 am.[75] The artillery and CAF strikes caused panic in the RSK rear, but did not take out the Sava River bridge in Stara Gradiška.[60] Bobetko was concerned about the RSK tanks located in the town as a possible counter-attack force and requested that the CAF use its Mil Mi-24s to prevent the RSK armour from intervening.[76]

At 5:30 am, Croatian special police moved through a gap in the RSK defences, between the 98th Infantry Brigade facing Novska and the Tactical Group 1 (TG1) defending Jasenovac, disrupting the integrity of RSK positions,[77] and outflanking the 98th Brigade on the Novska–Okučani axis of the HV attack, where a battalion of the 1st Guards advanced along a secondary road parallel to the motorway, while one battalion from the 2nd Guards and the 3rd Guards Brigades each advanced east on the motorway itself, crushing the RSK defence.[60][78] At 1 pm, the commanding officer of the RSK 98th Infantry Brigade left the unit and reported to the Corps commander that the brigade was in disarray, citing heavy losses.[79] The HV attack aimed at capturing Jasenovac was a two-pronged advance of the 125th Home Guard Regiment supported by the special police south and east from Bročice and Drenov Bok.[60] The TG1 offered no significant resistance, and the HV captured Jasenovac between noon and 1 pm.,[80][81] the RSK authorities in Okučani permitted the evacuation of civilians;[82] however, the civilians were quickly joined by retreating elements of the 98th and the 54th Brigades. The TG1 retreated south across the Sava River.[83] After capture of Jasenovac, the HV 125th Home Guards Regiment and the special police advanced eastward along the Sava River.[78]

On the Nova Gradiška–Okučani axis, the RSK 54th Infantry Brigade held positions east of Okučani, facing the 4th Battalion of the 5th Guards Brigade, the 81st Guards Battalion, an armoured company of the 123rd Brigade and the 121st Home Guard Regiment of the HV.[63][72] Due to a breakdown in the chain of command, the HV attack was delayed, forcing the 81st Guards Battalion to face well prepared defenders in Dragalić.[60] Stipetić, who toured the front line personally,[84] reported that the delay was up to two and a half hours.[85] In response, the HV redirected the 4th Battalion of the 5th Guards Brigade, the 265th Reconnaissance Sabotage Company and the armoured company of the 123rd Brigade to dislodge the RSK troops.[84] The RSK 54th Infantry Brigade put up strong resistance until 9 am, when its commander ordered a retreat.[83] Still, the HV force captured the village of Bijela Stijena on the Okučani–Pakrac road and encircled Okučani by 11 pm on 1 May, before suspending its advance for the night.[82] The capture of Bijela Stijena effectively isolated the RSK 51st Infantry Brigade, the 59th and the 63rd Detachments and the RSK Special police battalion,[83] as well as the 1st Battalion of the 54th Infantry Brigade and the 2nd Battalion of the 98th Infantry Brigade north of Okučani.[74] Furthermore, the RSK force near Pakrac could not communicate with the Corps command because their communication system failed.[86] In the Pakrac area, the HV deployed the 105th Infantry Brigade and the 52nd Home Guard Regiment. It was estimated that the RSK forces there were well entrenched and that the HV chose to envelop and pin them down rather than engage in any large-scale combat.[87]

2 May

[edit]

The HV resumed its advance in the early morning of 2 May. The retreating elements of the RSK 98th and 54th Infantry Brigades mixed with civilians evacuating south towards the Republika Srpska clashed with the 265th Reconnaissance Sabotage Company near Novi Varoš, but managed to continue south. The RSK 18th Corps moved its headquarters from Stara Gradiška across the Sava River to Gradiška in Republika Srpska against the orders of General Milan Čeleketić, the chief of the RSK General Staff.[74] The HV captured Okučani at 1 pm as the HV pincers advancing from Novska and Nova Gradiška met.[60] At about the same time, the command of the RSK 54th Infantry Brigade arrived to Stara Gradiška having evacuated from Okučani, and ordered an artillery strike on Nova Gradiška in retaliation.[74] Even though a token support of 195 RSK troops arrived to the area from eastern Slavonia, they refused to fight upon learning of the developments on the battleground.[88]

The RSK 18th Corps requests for close air support were denied by the political leadership of the Republika Srpska as well as the RSK Main Staff. They thought that the HV might attack other RSK-held areas and because of the NATO Operation Deny Flight—enforcing a no-fly zone over Bosnia and Herzegovina which would have to be overflown to assist the 18th Corps. The RSK deployed only two helicopters to support the corps, but they could not be directed against the HV because of the communication system failure. In contrast, the CAF attacked RSK positions near Stara Gradiška, specifically the bridge spanning the Sava River there. In one such sortie, the air defence of the Republika Srpska shot down a CAF MiG-21 flown by Rudolf Perešin (who had defected to Austria in 1991) at 1 pm on 2 May, killing him.[89]

The RSK leadership decided to retaliate against Croatia by ordering the artillery bombardment of Croatian urban centres. On 2 May, the RSK military attacked Zagreb and Zagreb Airport using eleven M-87 Orkan rockets carrying cluster munitions.[90] The attack was repeated the next day.[91] Six civilians were killed and 205 injured in the two attacks, while a policeman was killed defusing one of 500 unexploded bomblets.[92] United States ambassador to Croatia, Peter Galbraith called the attack a declaration of an all-out war.[90]

3 May

[edit]

On 3 May, Croatia and the RSK reached an agreement, mediated by the personal representative of the Secretary-General of the United Nations Yasushi Akashi, to end hostilities by 4 pm later that day. Consequently, the RSK General Staff instructed the 18th Western Slavonian Corps to cease fire at 3 pm. Babić in turn ordered Lieutenant Colonel Stevo Harambašić, the commanding officer of the RSK 51st Infantry Division to surrender 7,000 troops and civilians encircled by the HV south of Pakrac to the Argentine UNCRO battalion—as agreed by with the Croatian authorities.[93] Harambašić and about 600 troops surrendered on 3 May, while many more remained in the Psunj mountain east and southeast of Pakrac.[91] The surrender was accepted by Pakrac chief of police, Nikola Ivkanec.[94]

4 May and beyond

[edit]As hundreds of RSK troops refused to surrender, remaining in the Psunj forests, Bobetko appointed Stipetić to conduct mop-up operations against those troops. The HV used artillery attacks to flush approximately 1,500 RSK troops towards its positions and captured them by the end of the day. Nonetheless, the HV and the Croatian special police continued to sweep the area for any remaining RSK military personnel.[91] One such group of about 50 soldiers of the RSK 2nd Battalion of the 98th Infantry Brigade swam across the Sava River into the Republika Srpska on 7 May.[95] The mop-up operations were completed by 20 May, when the last remaining RSK troops surrendered to the Croatian police on Psunj.[83]

Aftermath

[edit]Operation Flash was a strategic victory for Croatia. It captured 558-square-kilometre (215 sq mi) area formerly held by the RSK,[96] and placed the entire western Slavonia region under Croatian government control and secured the use of strategically important road and rail links between the capital and the east of the country.[97] Croatian military losses in the offensive were 42 killed and 162 wounded. Croatia initially estimated that the RSK military sustained 350–450 killed and 1,000–1,200 wounded.[98] The number of killed in action was later revised to 188.[99] This figure included military and civilian deaths.[67] On 3–4 May, the HV and the Croatian special police took approximately 2,100 prisoners of war.[91] The prisoners of war, including arrested RSK officials, were transferred to detention facilities in Bjelovar, Požega and Varaždin for investigation of any involvement in war crimes.[100] Some of the detainees were beaten or otherwise abused on the first evening of their detention, but treatment of the prisoners improved and was viewed as generally good.[99] Three Jordanian soldiers serving with the UNCRO were wounded by HV fire.[101]

Another consequence of Operation Flash was the displacement of the Serb population from the area—estimated at 13,000 to 14,000 prior to 1 May 1995.[67][101] Two-thirds of that population fled the region during or immediately after the Croatian offensive. Furthermore, 2,000 were evacuated to Serb-held areas of Bosnia and Herzegovina on their own request within a month of Operation Flash. It was estimated that no more than 1,500 Serbs remained living in the area by the end of June.[67] Serbian sources claim that 283 Serbs were killed and that between 15,000[102] and 30,000 were made refugees, while asserting that the population of the region was 15,000 prior to the offensive.[103] Other Serbian and Russian sources claim the population size as high as 29,000.[102][104][105][106] The Croatian Helsinki Committee reported a total of 83 civilians killed, including 30 who were killed near Novi Varoš where Serb civilians and the RSK military were intermingled as they fled south towards the Republika Srpska.[107] A portion of the 30 killed in the retreating column were casualties of HV attacks, while others were killed by RSK troops to speed up the retreat.[108]

Response

[edit]Akashi was criticised by the Human Rights Watch (HRW) for alleging "massive" human rights abuses by the HV despite a lack of evidence to support such claims.[101] The organization also criticised Akashi's statement of 6 May claiming that the UNHCR office in Banja Luka interviewed 100 of the refugees from western Slavonia and determined that the refugee column was subjected to HV artillery and sniper attacks. The HRW concluded that three non-Serbian speaking UNHCR staff were unlikely to conduct proper interview of 100 people in just four days, assessing the circumstances of the interviews as being highly suspect.[109] In contrast to Akashi, the HRW deemed that the HV's conduct was professional.[101] Afterwards, United Nations Commission on Human Rights rapporteur Tadeusz Mazowiecki visited the area and concluded that there were serious breaches of humanitarian law and human rights by both sides in the conflict, albeit not on a massive scale.[110]

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) issued two statements, one on 1 May and the other on 4 May 1995, during and immediately after the operation, respectively. The first statement demanded that Croatia end its attack in the area, and that both Croatia and the RSK should abide with the economic and ceasefire agreements in place.[111] The second statement reiterated the requests made three days earlier, adding the UNSC's condemnation of RSK attacks on Zagreb and other population centres, urged an immediate ceasefire brokered by Akashi and condemned the incursions of the HV in zones of separation in Banovina, Kordun, Lika and northern Dalmatia, near Knin (UNCRO Sectors North and South), as well as incursions by both the HV and the military of the RSK in eastern Slavonia (UNCRO Sector East). The statement called for the withdrawal of forces from the zones of separation in the Sectors North, South and East, but failed to request any pullout from the UNCRO Sector West—the area where Operation Flash had just been fought.[112] The statements were supported by the UNSC Resolution 994.[113] In August 1995, after Operation Storm, the UNCRO withdrew to the eastern Slavonia.[52]

The RSK defeat worsened political confrontation there and led politicians in Serbia and RSK to blame each other,[114] and the HV's success brought about a great psychological boost for Croatia.[115] Croatia established a commemorative medal to be issued to the HV troops who took part in the operation,[116] and commemorates Operation Flash by annual official celebrations in Okučani,[117] while Serbs mark the anniversary of the battle by church services for their dead.[103]

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, set up in 1993 based on the UN Security Council Resolution 827,[118] tried Martić and Momčilo Perišić, the Chief of the General Staff of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia at the time of Operation Flash, for various war crimes, including the Zagreb rocket attacks. Milan Martić, RSK president at the time of the offensive, was convicted and sentenced to 35 years of imprisonment on 12 June 2007,[2] and Perišić received a prison sentence of 27 years on 6 September 2011.[119] Martić's sentence was confirmed by the ICTY appeals chamber on 8 October 2008,[120] while Perišić's conviction was overturned on 28 February 2013.[121] As of April 2012[update], Croatian authorities are conducting an investigation into the killing of 23 individuals in Medari near Nova Gradiška,[122] and charges were filed regarding the alleged mistreatment of prisoners of war in the detention facility in Varaždin.[123]

After the war ended, the Serb National Council ensured the partial return of Serbs to areas exposed to Operations Flash, through the struggle for their fundamental human rights.[124] The Human Rights Watch reported in 1999 that Serbs do not enjoy their civil rights as Croatian citizens, as a result of discriminatory laws and practices, particularly true for Serbs living in the four former United Nations Protected Areas, including Western Slavonia.[125] In 2017 report, the Amnesty International expressed concern about persisting obstacles for Serbs to regain their property.[126] They reported that Croatian Serbs continued to face discrimination in public sector employment and the restitution of tenancy rights to social housing vacated during the war. They also pointed to hate speech, "evoking fascist ideology" and the right to use minority languages and script continued to be politicized and unimplemented in some towns. However the Croatian courts regularly prosecuted cases of defamation and insult to the honour and reputation of persons. These offences were classified as serious criminal offences under the Criminal Code.[126]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The New York Times & 19 August 1990

- ^ a b c ICTY & 12 June 2007

- ^ a b Brigović 2009, pp. 40–41

- ^ Nikiforov 2011, p. 781

- ^ The New York Times & 2 April 1991

- ^ The New York Times & 3 March 1991

- ^ The New York Times & 26 June 1991

- ^ Narodne novine & 8 October 1991

- ^ The New York Times & 29 June 1991

- ^ Hoare 2010, p. 123

- ^ Nikiforov 2011, p. 785

- ^ The New York Times & 05 September 1997

- ^ ECOSOC & 17 November 1993, Section J, points 147 & 150

- ^ Ramet 2010, p. 263

- ^ EECIS 1999, pp. 272–278

- ^ The Independent & 10 October 1992

- ^ The New York Times & 24 September 1991

- ^ Bjelajac & Žunec 2009, pp. 249–250

- ^ The New York Times & 18 November 1991

- ^ a b The New York Times & 3 January 1992

- ^ Los Angeles Times & 29 January 1992

- ^ Thompson 2012, p. 417

- ^ The New York Times & 24 January 1993

- ^ The New York Times & 15 July 1992

- ^ ECOSOC & 17 November 1993, Section K, point 161

- ^ The New York Times & 13 September 1993

- ^ Nikiforov 2011, pp. 790–791

- ^ The Seattle Times & 16 July 1992

- ^ The New York Times & 17 August 1995

- ^ Bjelajac & Žunec 2009, p. 254

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 465

- ^ Jutarnji list & 9 December 2007

- ^ Dunigan 2011, pp. 92–93

- ^ Dunigan 2011, p. 92

- ^ Dunigan 2011, p. 93

- ^ Dunigan 2011, pp. 93–95

- ^ Avant 2005, p. 104

- ^ Radio Free Europe & 20 August 2010

- ^ Bono 2003, p. 107

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 439

- ^ Andreas 2011, p. 112

- ^ Woodward 2010, p. 432

- ^ a b Armatta 2010, pp. 201–204

- ^ Ahrens 2007, pp. 160–166

- ^ Galbraith 2006, p. 126

- ^ Bideleux & Jeffries 2007, p. 205

- ^ Štefančić 2011, p. 440

- ^ The New York Times & 2 May 1995

- ^ Brigović 2009, p. 43

- ^ Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, p. 296

- ^ Jones, Ramsbotham & Woodhouse 1995, pp. 246–251

- ^ a b UNCRO

- ^ Brigović 2009, pp. 43–44

- ^ Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, pp. 296–297

- ^ Štefančić 2011, p. 451

- ^ Brigović 2009, p. 44

- ^ Štefančić 2011, p. 452

- ^ Brigović 2009, p. 48

- ^ ICTY & 22 January 2004, p. 31288

- ^ a b c d e f g h Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, p. 297

- ^ Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, p. 276

- ^ Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, note 72/VII

- ^ a b MORH 2010

- ^ Brigović 2009, p. 47

- ^ Brigović 2009, p. 45

- ^ Brigović 2009, p. 63

- ^ a b c d e Ramet 2006, p. 456

- ^ Brigović 2009, note 32

- ^ Brigović 2009, pp. 46–47

- ^ Brigović 2009, p. 65

- ^ Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, notes 73-75/VII

- ^ a b President of Croatia & 14 December 2012

- ^ Brigović 2009, p. 51

- ^ a b c d Brigović 2009, p. 53

- ^ Brigović 2009, note 49

- ^ Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, note 81/VII

- ^ Sekulić 2000, p. 105

- ^ a b Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, note 82/VIII

- ^ Sekulić 2000, pp. 105–106

- ^ Brigović 2009, p. 50

- ^ Index.hr & 29 April 2005

- ^ a b Brigović 2009, p. 52

- ^ a b c d Sekulić 2000, p. 106

- ^ a b Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, note 83/VII

- ^ Nacional & 24 April 2002

- ^ Brigović 2009, p. 54

- ^ Brigović 2009, pp. 51–52

- ^ Sekulić 2000, p. 110

- ^ Brigović 2009, pp. 57–58

- ^ a b San Francisco Chronicle & 3 May 1995

- ^ a b c d Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, p. 298

- ^ Jutarnji list & 2 May 2012

- ^ Brigović 2009, p. 60

- ^ Slobodna Dalmacija & 18 September 2004

- ^ Brigović 2009, note 54

- ^ Sekulić 2000, p. 80

- ^ Štefančić 2011, p. 436

- ^ Brigović 2009, p. 64

- ^ a b HRW & July 1995, p. 2

- ^ Brigović 2009, p. 61

- ^ a b c d HRW & July 1995, p. 6

- ^ a b Štrbac 2005, p. 225

- ^ a b B92 & 1 May 2009

- ^ Sekulić 2000, p. 81

- ^ Guskova 2001, p. 493

- ^ Nikiforov 2011, p. 795

- ^ Brigović 2009, note 105

- ^ Index.hr & 24 July 2003

- ^ HRW & July 1995, p. 17

- ^ Ahrens 2007, p. 169

- ^ UNSC & 1 May 1995

- ^ UNSC & 4 May 1995

- ^ UNHCR & 17 May 1995

- ^ Sekulić 2000, p. 119

- ^ The New York Times & 4 May 1995

- ^ Narodne novine & 7 August 1995

- ^ Nacional & 1 May 2011

- ^ Schabas 2006, pp. 3–4

- ^ ICTY & 6 September 2011

- ^ ICTY & IT-95-11

- ^ BBC & 28 February 2013

- ^ DORH & May 2012

- ^ Glas Slavonije & 4 May 2012

- ^ Škiljan 2016, p. 110

- ^ HRW & March 1999

- ^ a b Amnesty & 1 January 2017, pp. 131–133

References

[edit]- Books

- Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995. Diane Publishing Company. 2003. ISBN 978-0-7567-2930-1. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. Routledge. 1999. ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5.

- Ahrens, Geert-Hinrich (2007). Diplomacy on the Edge: Containment of Ethnic Conflict and the Minorities Working Group of the Conferences on Yugoslavia. Woodrow Wilson Center Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8557-0. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Andreas, Peter (2011). Blue Helmets and Black Markets. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801457043. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- Armatta, Judith (2010). Twilight of Impunity: The War Crimes Trial of Slobodan Milosevic. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4746-0. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Avant, Deborah D. (2005). The Market for Force: The Consequences of Privatizing Security. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-61535-8. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (2007). The Balkans: A Post-Communist History. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-22962-3. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Bjelajac, Mile; Žunec, Ozren (2009). "The War in Croatia, 1991–1995". In Charles W. Ingrao; Thomas Allan Emmert (eds.). Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars' Initiative. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-533-7. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Bono, Giovanna (2003). Nato's 'Peace Enforcement' Tasks and 'Policy Communities': 1990–1999. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-0944-5. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Dunigan, Molly (2011). Victory for Hire: Private Security Companies' Impact on Military Effectiveness. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7459-8. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Galbraith, Peter (2006). "Negotiating peace in Croatia: a personal account of the road to Erdut". In Brad K. Blitz (ed.). War and Change in the Balkans: Nationalism, Conflict and Cooperation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-67773-8. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Calic, Marie-Janine (2009). "Ethnic Cleansing and War Crimes, 1991–1995". In Charles W. Ingrao; Thomas Allan Emmert (eds.). Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars' Initiative. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-533-7.

- Guskova, Elena (2001). История югославского кризиса: 1990–2000 [The history of the Yugoslav crisis: 1990–2000] (in Russian). Russkoe pravo. ISBN 978-5941910038.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (2010). "The War of Yugoslav Succession". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139487504.

- Nikiforov, Konstantin (2011). Югославия в XX веке: очерки политической истории [Yugoslavia in the 20th Century: Essays on Political History] (in Russian). Indrik. ISBN 9785916741216.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building And Legitimation, 1918–2006. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2010). "Politics in Croatia since 1990". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139487504.

- Schabas, William A. (2006). The UN International Criminal Tribunals: The Former Yugoslavia, Rwanda and Sierra Leone. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84657-8. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- Sekulić, Milisav (2000). Knin je pao u Beogradu [Knin was lost in Belgrade] (in Serbian). Nidda Verlag. OCLC 47749339. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- Štrbac, Savo (2005). Hronika prognanih Krajišnika [Chronicle of Expelled Krajišniks] (in Serbian). Zora. ISBN 978-86-83809-24-0.

- Thompson, Wayne C. (2012). Nordic, Central & Southeastern Europe 2012. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-61048-891-4. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Woodward, Susan L. (2010). "The Security Council and the Wars in the Former Yugoslavia". In Vaughan Lowe; Adam Roberts; Jennifer Welsh; Dominik Zaum (eds.). The United Nations Security Council and War:The Evolution of Thought and Practice since 1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-161493-4. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Škiljan, Filip (2016). "The Security Council and the Wars in the Former Yugoslavia". Ethnic Minorities and Politics in Post-Socialist Southeastern Europe. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316671290.007. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- Scientific journal articles

- Brigović, Ivan (July 2009). "Osvrt na operaciju "Bljesak" u dokumentima Republike Srpske Krajine" [A review of Operation Flash in documents published by the Republic of Serbian Krajina]. Časopis Za Suvremenu Povijest (in Croatian). 41 (1). ISSN 0590-9597. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- Jones, Richard; Ramsbotham, Oliver; Woodhouse, Tom (1995). "Peacekeeping mission updates (January–March 1995)". International Peacekeeping. 2 (2): 246–251. doi:10.1080/13533319508413554. ISSN 1353-3312.

- Štefančić, Domagoj (December 2011). "Autocesta – okosnica rata u zapadnoj Slavoniji" [Motorway – axis of war in the Western Slavonia]. Journal – Institute of Croatian History (in Croatian). 43 (1). ISSN 0353-295X. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- News reports (listed in chronological order)

- "Roads Sealed as Yugoslav Unrest Mounts". The New York Times. Reuters. 19 August 1990. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- Engelberg, Stephen (3 March 1991). "Belgrade Sends Troops to Croatia Town". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- Sudetic, Chuck (2 April 1991). "Rebel Serbs Complicate Rift on Yugoslav Unity". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- Sudetic, Chuck (26 June 1991). "2 Yugoslav States Vote Independence To Press Demands". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Sudetic, Chuck (29 June 1991). "Conflict in Yugoslavia; 2 Yugoslav States Agree to Suspend Secession Process". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Cowell, Alan (24 September 1991). "Serbs and Croats: Seeing War in Different Prisms". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Sudetic, Chuck (18 November 1991). "Croats Concede Danube Town's Loss". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Sudetic, Chuck (3 January 1992). "Yugoslav Factions Agree to U.N. Plan to Halt Civil War". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- Williams, Carol J. (29 January 1992). "Roadblock Stalls U.N.'s Yugoslavia Deployment". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- Kaufman, Michael T. (15 July 1992). "The Walls and the Will of Dubrovnik". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Maass, Peter (16 July 1992). "Serb Artillery Hits Refugees – At Least 8 Die As Shells Hit Packed Stadium". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- Bellamy, Christopher (10 October 1992). "Croatia built 'web of contacts' to evade weapons embargo". The Independent. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Sudetic, Chuck (24 January 1993). "Croats Battle Serbs for a Key Bridge Near the Adriatic". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- "Rebel Serbs List 50 Croatia Sites They May Raid". The New York Times. 13 September 1993. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- Cohen, Roger (2 May 1995). "Croatia hits area rebel Serbs hold, crossing U.N. lines". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- "Serbs Attack Zagreb With Cluster Bombs". San Francisco Chronicle. 3 May 1995. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- Cohen, Roger (4 May 1995). "Rebel Serbs Pound Zagreb for Second Day". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- Bonner, Raymond (17 August 1995). "Dubrovnik Finds Hint of Deja Vu in Serbian Artillery". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- Babić, Jasna (24 April 2002). "Janko Bobetko: 'Greške generala Džanka u akciji 'Bljesak' može potvrditi moj tadašnji pomoćnik general Stipetić'" [Janko Bobetko: Mistakes of General Džanko in Operation Flash may be corroborated by my aide at the time, General Stipetić]. Nacional (weekly) (in Croatian). Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- "HHO iznio imena 83 srpska civila koje je navodno ubila HV tijekom "Bljeska"" [HHO publishes names of 83 Serb civilians allegedly killed by the HV in the "Flash"] (in Croatian). Index.hr. 24 July 2003. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- Krstulović, Zvonimir (18 September 2004). "Heroj domovinskog rata" [Hero of the Croatian War of Independence]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- "U Novskoj obilježena 10. obljetnica "Bljeska"" [10th anniversary of "Flash" marked in Novska] (in Croatian). Index.hr. 29 April 2005. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- Vurušić, Vlado (9 December 2007). "Krešimir Ćosić: Amerikanci nam nisu dali da branimo Bihać" [Krešimir Ćosić: Americans did not let us defend Bihać]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 28 October 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- "Anniversary of Croatia's "Flash" onslaught". B92. 1 May 2009. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- Barbir-Mladinović, Ankica (20 August 2010). "Tvrdnje da je MPRI pomagao pripremu 'Oluje' izmišljene" [Claims that the MPRI helped prepare the 'Storm' are fabrications] (in Croatian). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- "Bebić: "Bljesak" je obasjao nadolazeću "Oluju"" [Bebić: "Flash" made forthcoming "Storm" bright]. Nacional (weekly) (in Croatian). 1 May 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- "Centar Zagreba prije 17 godina raketiran u odmazdi za "Bljesak": Poginulo je šestero, a ranjeno 205 ljudi" [Downtown Zagreb rocket attack 17 years ago in retaliation for "Flash": Six killed, 205 wounded]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian). Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- Boroš, Dražen. "Stipetić: Nakon Bljeska nije bilo mučenja ratnih zarobljenika" [Stipetić: No POWs were tortured after Operation Flash]. Glas Slavonije (in Croatian). Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- "Momcilo Perisic: Yugoslav army chief conviction overturned". BBC News. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- "Croatian's Confession Describes Torture and Killing on Vast Scale". The New York Times. 5 September 1997.

- "Početak vojno-redarstvene operacije "Bljesak"". Vojna Povijest. 1 May 2017.

- Other sources

- "Case information sheet – "RSK" (IT-95-11) Milan Martić" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- "United Nations Confidence Restoration Operation". United Nations. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- "Odluka" [Decision]. Narodne novine (in Croatian) (53). 8 October 1991. ISSN 1333-9273. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- "Situation of human rights in the territory of the former Yugoslavia". United Nations Economic and Social Council. 17 November 1993. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- "Statement by the President of the Security Council (S/PRST/1995/23)". United Nations Security Council. 1 May 1995. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- "Statement by the President of the Security Council (S/PRST/1995/26)". United Nations Security Council. 4 May 1995. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- "Resolution 994 (1995) Adopted by the Security Council at its 3537th meeting, on 17 May 1995". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 17 May 1995. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- "The Croatian army offensive in western Slavonia and its aftermath" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. July 1995. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- "Odluka o ustanovljenju medalja za sudjelovanje u vojno-redarstvenim operacijama i u iznimnim pothvatima (NN 060/1995)" [Decision on establishment of medals commemorating partaking of military-policing operations and exceptional efforts (OG 060/1995)] (in Croatian). Croatian Government. 7 August 1995. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- "ICTY Trial of Slobodan Milošević – Transcript". International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 22 January 2004. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- "The Prosecutor vs. Milan Martic – Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 12 June 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- "Vojno redarstvena operacija "Bljesak"" [Military and police operation "Flash"] (in Croatian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia). 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- "Summary of the Judgement in the Case of Prosecutor v. Momčilo Perišić" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 6 September 2007. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- "U emisiji "In medias res" objavljene netočne tvrdnje" ["In medias res" show publicized false claims] (in Croatian). State Attorney's Office (Croatia). May 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- "Predsjednik Josipović odlikovao 15. križevačku protuoklopnu topničko-raketnu brigadu" [President Josipović decorates the 15th Antitank Artillery-Rocket Brigade Križevci] (in Croatian). Office of the President of Croatia. 14 December 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- "Second Class Citizens: The Serbs of Croatia". Human Rights Watch. March 1999. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- "Amnesty International report 2016/2017" (PDF). Amnesty International. 1 January 2017.

45°16′N 17°12′E / 45.26°N 17.2°E