Charles Correa

Charles Correa | |

|---|---|

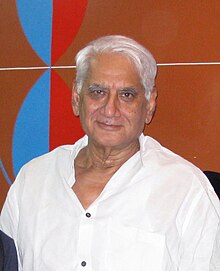

Correa in 2011 | |

| Born | 1 September 1930 |

| Died | 16 June 2015 (aged 84) Mumbai, India |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Alma mater | University of Mumbai Massachusetts Institute of Technology University of Michigan |

| Occupation(s) | Architect Urban planner |

| Spouse | |

| Buildings | Jawahar Kala Kendra, National Crafts Museum, Bharat Bhavan |

Charles Mark Correa (1 September 1930 – 16 June 2015) was an Indian architect and urban planner. Credited with the creation of modern architecture in post-Independent India, he was celebrated for his sensitivity to the needs of the urban poor and for his use of traditional methods and materials.[1]

Biography

Early life

Charles Correa, a Roman Catholic of Goan descent, was born on 1 September 1930 in Secunderabad.[2][3] He began his higher studies at St. Xavier's College, Mumbai. He went on to study at the University of Michigan (1949–53) where Buckminster Fuller was a teacher, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1953–55) where he obtained his master's degree.[4][5]

Career

In 1958, Charles Correa established his own professional practice in Mumbai. His first significant project was the Mahatma Gandhi Sangrahalaya (Mahatma Gandhi Memorial) at Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad (1958–1963), followed by the Madhya Pradesh Legislative Assembly in Bhopal (1967). In 1961-1966, he designed his first high-rise building, the Sonmarg apartments in Mumbai. On the National Crafts Museum in New Delhi (1975–1990), he introduced "the rooms open to the sky", his systematic use of courtyards. In the Jawahar Kala Kendra (Jawahar Arts Centre) in Jaipur (1986–1992), he makes a structural hommage to Jai Singh II. Later, he invited the British artist Howard Hodgkin for the outside design of the British Council in Delhi (1987–1992).[5]

From 1970–75, Charles Correa was Chief Architect for New Bombay (Navi Mumbai), where he was strongly involved in extensive urban planning of the new city.[6][5] In 1984, Charles Correa founded the Urban Design Research Institute in Bombay,[5] dedicated to the protection of the built environment and improvement of urban communities. During the final four decades of his life, Correa has done pioneering work in urban issues and low-cost shelter in the Third World. In 1985, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi appointed him Chairman of the National Commission on Urbanization.

From 2005 until his 2008 resignation Correa was the Chairman of the Delhi Urban Arts Commission.

Later, Charles Correa designed the new Ismaili Centre in Toronto, Canada,[7] which shared the site with the Aga Khan Museum designed by Fumihiko Maki,[8] and the Champalimaud Foundation Centre in Lisbon, inaugurated by the Portuguese President Aníbal Cavaco Silva on 5 October 2010.[9]

Final years

He died on 16 June 2015 in Mumbai following a brief illness.[10]

Work

Style

Charles Correa designed almost 100 buildings in India, from low-income housing to luxury condos. He rejected the glass-and-steel approach of some post-modernist buildings, and focused on designs deeply rooted in local cultures, all the while providing modern structural solutions under his creative designs. His style was also focused on reintroducing outdoor spaces and terraces.[11][12]

His work is the physical manifestation of the idea of Indian nationhood, modernity and progress. His vision sits at the nexus defining the contemporary Indian sensibility and it articulates a new Indian identity with a language that has a global resonance. He is someone who has that rare capacity to give physical form to something as intangible as ‘culture’ or ‘society’ – and his work is therefore critical: aesthetically; sociologically; and culturally.

— British architect David Adjaye in 2013.[11]

In 2013, the Royal Institute of British Architects held a retrospective exhibition, "Charles Correa – India's Greatest Architect", about the influences of his work on modern urban Indian architecture.[6][13]

Projects

| Photo | Date | Name | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1958–63 | Mahatma Gandhi Sangrahalaya Mahatma Gandhi Memorial |

Sabarmati Ashram, Ahmedabad | |

| 1958–59 | Cama Hotel | Ahmedabad | substantially altered later by owners[14] | |

| 1961–62 | Tube House | Ahmedabad | demolished[5] | |

| 1961–66 | Sonmarg apartments | Mumbai | ||

|

1967 | Madhya Pradesh Legislative Assembly | Bhopal | |

|

1969–74 | Kovalam Beach Resort | Kovalam | sloping architecture that blends into the landscape[15] |

|

1970 | Kala Academy | Panaji | [16] |

|

1975–90 | National Crafts Museum | New Delhi | |

| R&D facility of Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd | Mahindra Research Valley, Chennai | |||

| 1980–97 | Vidhan Bhavan | |||

|

1982 | Bharat Bhavan | Bhopal | |

|

1986–92 | Jawahar Kala Kendra Jawahar Arts Centre |

Jaipur | |

|

1986 | Jeevan Bharati Life Insurance Corporation of India |

On the 2018 World Monuments Watch list of "50 Cultural Sites at Risk from Human and Natural Threats"[17] | |

|

1987–92 | British Council | Delhi | |

|

1989 | Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research | Bangalore | |

|

2000 | St. Peter and St. Paul's Church, Parumala | Parumala, Thiruvalla | |

|

2000–05 | McGovern Institute for Brain Research | MIT, Boston, US | |

| 2004 | City centre | Salt Lake City, Kolkata | ||

|

2007–10 | Champalimaud Centre for The Unknown | Lisbon, Portugal | |

|

Ismaili Centre | Toronto, Canada | ||

| Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Banking and Finance | Hyderabad |

Awards

- 1972: Padma Shri[18]

- 1984: Royal Gold Medal for architecture by the Royal Institute of British Architects.[19]

- 1994: Praemium Imperiale

- 1998: 7th Aga Khan Award for Architecture for Madhya Pradesh Legislative Assembly[20]

- 2005: Austrian Decoration for Science and Art[21]

Charles Correa receiving Padma Vibhushan from President Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam in 2006 - 2006: Padma Vibhushan given by Government of India[22]

- 2011: Gomant Vibhushan conferred by Government of Goa[22]

Publications

- Charles Correa, The New Landscape, RIBA Enterprises, December 1985, (ISBN 978-0947877217)[11]

Personal life

Charles Correa married Monika (née Sequeira), an artist, in 1961. Together they lived in one of the flats of the Sonmarg apartments in Mumbai. They had two children.[5]

See also

References

- ^ An Architecture of Independence: The Making of Modern South Asia Archived 3 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ "Charles Correa". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ Kazi Khaleed Ashraf, James Belluardo (1998), An Architecture of Independence: The Making of Modern South Asia, Architectural League of New York, p. 33, ISBN 09663-8560-8

- ^ "Charles Correa | Indian architect". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ a b c d e f Rykwert, Joseph (19 June 2015). "Charles Correa obituary" – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ a b "Master class with Charles Correa". Mumbai Mirror. 9 June 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ "About the Ismaili Centre, Toronto". the.Ismaili. 6 September 2014.

- ^ "Correa, Maki Tapped to Design Aga Khan Center". Architectural Record, The McGraw-Hill Companies. 6 October 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- ^ David MacManus, The Champalimaud Foundation, Lisbon, E-architect.co.uk 5 October 2010

- ^ "Architect Charles Correa dies at 84 | India News - Times of India". The Times of India.

- ^ a b c Charlotte Luxford, 'India’s Greatest Architect' Charles Correa, Theculturetrip.com, 17 August 2018

- ^ "Charles Correa – India's greatest architect?". BBC News. 14 May 2013. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ "Charles Correa & Out of India Season". RIBA. 2013. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ "Charles correa - hotels , apartments, townships,residences". 15 April 2016.

- ^ "Charles correa - hotels , apartments, townships,residences". 15 April 2016.

- ^ Eric Baldwin, New Petition Aims to Save Charles Correa's Kala Academy from Demolition, Archdaily.com, 7 August 2019

- ^ Patrick Lynch, 2018 World Monuments Watch Lists 50 Cultural Sites at Risk from Human and Natural Threats, Archdaily.com, 23 October 2017

- ^ "Padma Awards Directory (1954–2009)" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2013.

- ^ "List of medal winners 1848–2008 (PDF)" (PDF). RIBA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ "Archnet". Archnet. Archived from the original on 8 February 2006.

- ^ "Reply to a parliamentary question" (PDF) (in German). p. 1714. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ a b "CharlesCorrea, Gomant Vibhushan". The Times of India. 19 December 2011. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012.

Further reading

External links

- 1930 births

- 2015 deaths

- Goan Catholics

- St. Xavier's College, Mumbai alumni

- Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning alumni

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology alumni

- Postmodern architecture in India

- Urban designers

- Indian urban planners

- Recipients of the Padma Shri in science & engineering

- Recipients of the Padma Vibhushan in science & engineering

- Recipients of the Royal Gold Medal

- Recipients of the Praemium Imperiale

- Recipients of the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art

- 20th-century Indian architects

- People from Secunderabad

- Indian environmentalists

- Activists from Andhra Pradesh

- 20th-century Indian educational theorists

- Founders of Indian schools and colleges

- 21st-century Indian architects

- 21st-century Indian educational theorists

- Indian architects