Maratha Empire

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

Maratha Empire | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1674–1818 | |||||||||||

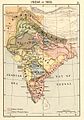

Territory under Maratha control in 1760 (yellow). | |||||||||||

| Capital | Raigad Fort (Maharashtra) Gingee (Tamil Nadu)[1] Satara (city) Pune (Maharashtra) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Marathi, Sanskrit[2] | ||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Chhatrapati | |||||||||||

• 1645–1680 | Shivaji (first) | ||||||||||

• 1808–1818 | Raja Pratap Singh, Raja of Satara (last) | ||||||||||

| Peshwa | |||||||||||

• 1674–1689 | Moropant Pingle (first) | ||||||||||

• 1803–1818 | Baji Rao II (last) | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Ashta Pradhan | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| 1674 | |||||||||||

| 1818 | |||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 2,800,000 km2 (1,100,000 sq mi) | |||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1700 | Not known | ||||||||||

| Currency | Rupee, Paisa, Mohor, Shivrai, Hon | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

| History of India |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| History of South Asia |

|---|

|

The Maratha Empire or the Maratha Confederacy was an Indian power that dominated much of the Indian subcontinent in the 18th century. The empire formally existed from 1674 with the coronation of Chhatrapati Shivaji and ended in 1818 with the defeat of Peshwa Bajirao II.[note 1].[3][4][5]

The Marathas were a Marathi warrior group from the western Deccan Plateau (present day Maharashtra) that rose to prominence by establishing a Hindavi Swarajya. The Marathas became prominent in the seventeenth century under the leadership of Shivaji who revolted against the Adil Shahi dynasty and the Mughal Empire and carved out a kingdom with Raigad as his capital. Known for their mobility, the Marathas were able to consolidate their territory during the Mughal–Maratha Wars and later controlled a large part of the Indian subcontinent.

Chhattrapati Shahu, grandson of Shivaji, was released by the Mughals after the death of Emperor Aurangzeb. Following a brief struggle with his aunt Tarabai, Shahu became the ruler and appointed Balaji Vishwanath and later, his descendants, as the peshwas or prime ministers of the empire.[6] Balaji and his descendants played a key role in the expansion of Maratha rule. The empire at its peak stretched from Tamil Nadu[7] in the south, to Peshawar (modern-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan[8] [note 2]) in the north, and Bengal in the east. In 1761, the Maratha Army lost the Third Battle of Panipat to Ahmad Shah Abdali of the Afghan Durrani Empire, which halted their imperial expansion into Afghanistan. Ten years after Panipat, the young Peshwa Madhavrao I's Maratha Resurrection reinstated Maratha authority over North India.

In a bid to effectively manage the large empire, Madhavrao I gave semi-autonomy to the strongest of the knights, which created a confederacy of Maratha states. They became known as the Gaekwads of Baroda, the Holkars of Indore and Malwa, the Scindias of Gwalior and Ujjain, the Bhonsales of Nagpur and the Puars of Dhar and Dewas. In 1775, the East India Company intervened in a Peshwa family succession struggle in Pune, which led to the First Anglo-Maratha War, resulting in a Maratha victory.[10] The Marathas remained the pre-eminent power in India until their defeat in the Second and Third Anglo-Maratha Wars (1805-1818), which left the East India Company in control of most of India.

A large portion of the Maratha empire was coastline, which had been secured by the potent Maratha Navy under commanders such as Kanhoji Angre. He was very successful at keeping foreign naval ships, particularly of the Portuguese and British, at bay.[11] Securing the coastal areas and building land-based fortifications were crucial aspects of the Maratha's defensive strategy and regional military history.

Nomenclature

The Maratha Empire is also referred to as the Maratha Confederacy. The historian Barbara Ramusack says that the former is a designation preferred by Indian nationalists, while the latter was that used by British historians. She notes, "neither term is fully accurate since one implies a substantial degree of centralisation and the other signifies some surrender of power to a central government and a longstanding core of political administrators. Maratha power was fragmented among several discrete fragments".[citation needed]

Although at present, the word Maratha refers to a particular caste of warriors and peasants, in the past the word has been used to describe Marathi people, including Marathas themselves.[12][13]

History

The empire had its head in the Chhatrapati as de jure, but the de facto governance was in the hands of the Peshwas.[citation needed] After the death of Chhatrapati Shahu and with the death of Madhavrao - I, various chiefs played the role of the de facto rulers in their own regions.

Shivaji and his descendants

Shivaji

Shivaji (1627-1680) was a Maratha aristocrat of the Bhosle clan who is considered to be the founder of the Maratha empire.[3] Shivaji led a resistance to free the Marathi people from the Sultanate of Bijapur from 1645 and establish Hindavi Swarajya (self-rule of Hindu people[14]). He created an independent Maratha kingdom with Raigad as its capital[15] and successfully fought against the Mughals to defend his kingdom. He was crowned as Chhatrapati (sovereign) of the new Maratha kingdom in 1674. The state Shivaji founded was a Maratha kingdom comprised about 4.1% of the subcontinent, but spread over large tracts. At the time of his death[3] it was dotted with about 300 forts, about 40,000 cavalry, 50,000 foot soldiers and naval establishments all over the west coast. Over time, the kingdom would increase in size and heterogeneity;[16] by the time of his grandson, and later under the Peshwas in the early 18th century, it was a full-fledged empire.[17]

Sambhaji

Shivaji had two sons: Sambhaji and Rajaram. Sambhaji, the elder son, was very popular among the courtiers.[citation needed] In 1681, Sambhaji had himself crowned and resumed his father's expansionist policies. Sambhaji had earlier defeated the Portuguese and Chikka Deva Raya of Mysore. To nullify alliance between his rebel son, Akbar, and the Marathas,[18] Aurangzeb himself headed south in 1681. With his entire imperial court, administration and an army of about 500,000 troops he proceeded to expand the Mughal empire, gaining territories such as the sultanates of Bijapur and Golconda. During the eight years that followed, Sambhaji led the Marathas, never losing a battle or a fort to Aurangzeb.[citation needed]

In early 1689, Sambhaji called his commanders for a strategic meeting at Sangameshwar to consider a final onslaught on the Mughal forces.[citation needed] In a meticulously planned operation, Ganoji Shirke and Aurangzeb's commander, Mukarrab Khan, attacked Sangameshwar when Sambhaji was accompanied by just a few men. Sambhaji was ambushed and captured by Mughal troops on February 01, 1689. He and his advisor, Kavi Kalash, were taken to Bahadurgad, where they were executed by the Mughals on 11 March 1689.[citation needed] Aurangzeb had Sambhaji executed on charges of atrocities committed by Maratha forces in the attack on Burhanpur that included plunder, killing, rape, and torture.[19][20]

Rajaram and Tarabai

Upon Sambhaji's death, his half-brother Rajaram assumed the throne. The Mughal siege of Raigad continued, and he had to flee to Vishalgad and then to Gingee for safety. From there the Marathas raided Mughal territory, and many forts were recaptured by Maratha commanders such as Santaji Ghorpade, Dhanaji Jadhav, Parshuram Pant Pratinidhi, Shankaraji Narayan Sacheev and Melgiri Pandit. In 1697, Rajaram offered a truce but this was rejected by Aurangzeb. Rajaram died in 1700 at Sinhagad. His widow, Tarabai, assumed control in the name of her son, Ramaraja (Shivaji II). She led the Marathas against the Mughals, and by 1705 they had crossed the Narmada River and entered Malwa, then in Mughal possession.[citation needed]

Shahu

After Aurangzeb's death in 1707, Shahu, son of Sambhaji (and grandson of Shivaji), was released by Bahadur Shah I, the new Mughal emperor. His mother was kept as a hostage of the Mughals, however, in order to ensure that Shahu adhered to the release conditions. Upon release, Shahu immediately claimed the Maratha throne and challenged his aunt Tarabai and her son. This promptly turned the now-spluttering Mughal-Maratha war into a three-cornered affair. The states of Satara and Kolhapur came into being in 1707 because of the succession dispute over the Maratha kingship. Shahu appointed Balaji Vishwanath as Peshwa.[21] The Peshwa was instrumental in getting Shahu accepted as rightful heir of Shivaji and the Chhatrapati of the Marathas by The Mughals.[22] Balaji also got Shahu's mother, Yesubai released from Mughal captivity in 1719 [23]

During Shahu's reign, Raghoji Bhosale expanded the empire in the East, reaching present-day Bengal. Khanderao Dabhade and later his son, Trimbakrao, expanded in the West in Gujarat.[24] Peshwa Bajirao and his three chiefs, Pawar (Dhar), Holkar (Indore), and Scindia (Gwalior), expanded in the North. All these houses became hereditary, thereby eventually undermining the Chhatrapati's authority there.[citation needed]

Peshwa era

During this era, Peshwas belonging to the Bhat family controlled the Maratha Army and later became de facto rulers of the Maratha Empire. During their reign, the Maratha Empire dominated most of the Indian subcontinent.

Balaji Vishwanath

Shahu appointed Peshwa Balaji Vishwanath in 1713. From his time, the office of Peshwa became supreme while Shahuji became a figurehead.[21]

- His first major achievement was the conclusion of the Treaty of Lanavala in 1714 with Kanhoji Angre, the most powerful naval chief on the Western Coast. He later joined the Marathas.[citation needed]

- In 1719, an army of Marathas marched to Delhi along with Sayyid Hussain Ali, the Mughal governor of Deccan, and managed to depose the Mughal emperor. Thus, Marathas realised for the first time their potential to make and unmake Mughal Emperors.[25]

Baji Rao I

After Balaji Vishwanath's death in April 1720, his son, Baji Rao I, was appointed Peshwa by Shahu. Bajirao is credited with expanding the Maratha Empire tenfold from 3% to 30% of the modern Indian landscape during 1720–1740. He fought over 41 battles before his death in April 1740 and is reputed to have never lost one.[26][better source needed]

- The Battle of Palkhed was a land battle that took place on February 28, 1728 at the village of Palkhed, near the city of Nashik, Maharashtra, India between Baji Rao I and the Qamar-ud-din Khan, Asaf Jah I of Hyderabad. The Marathas defeated the Nizam.The battle is considered an example of brilliant execution of military strategy.[25]

- In 1737, Marathas under Bajirao I raided the suburbs of Delhi in a blitzkrieg in the Battle of Delhi (1737).[27][28]

- The Nizam left Deccan to rescue Mughals from the invasion of Marathas, but was defeated decisively in the Battle of Bhopal.[28][29] The Marathas extracted a large tribute from the Mughals and signed a treaty which ceded Malwa to the Marathas.[30]

- The Battle of Vasai was fought between the Marathas and the Portuguese rulers of Vasai, a village lying on the northern shore of Vasai creek, 50 km north of Mumbai. The Marathas were led by Chimaji Appa, brother of Baji Rao. The Maratha victory in this war was a major achievement of Baji Rao's time in office.[28]

Balaji Baji Rao

Baji Rao's son, Balaji Bajirao (Nanasaheb), was appointed as the next Peshwa by Shahuji despite opposition of other chiefs.

- In 1740, the Maratha forces came down upon Arcot and defeated the Nawab of Arcot, Dost Ali, in the pass at Damalcherry. In the war that followed, Dost Ali, one of his sons Hasan Ali, and a number of other prominent persons lost their lives. This initial success at once enhanced Maratha prestige in the south. From Damalcherry, the Marathas proceeded to Arcot, which surrendered to them without much resistance. Then, Raghuji invaded Trichinopoly in December 1740. Unable to resist, Chanda Saheb surrendered the fort to Raghuji on March 14, 1741. Chanda Saheb and his son were arrested and sent to Nagpur.[31]

- Rajputana also came under Maratha domination during this time.[32]

Invasions in Bengal

After the successful campaign of Karnatak and the Battle of Trichinopolly, Raghuji returned from Karnatak. He undertook six expeditions in Bengal from 1741 to 1748.[33] Raghuji was able to annex Odisha to his kingdom permanently as he successfully exploited the chaotic conditions prevailing in Bengal, Bihar and Odisha after the death of their Governor, Murshid Quli Khan, in 1727. Constantly harassed by the Bhonsles, Odisha or Cuttack, Bengal and parts of Bihar were economically ruined. Alivardi Khan, Nawab of Bengal made peace with Raghuji in 1751 ceding in perpetuity Cuttack up to the river Subarnarekha, and agreeing to pay Rs.1.2 million annually in lieu of the Chauth of Bengal and Bihar.[32]

During the their occupuation of western Bengal, the Marathas perpetrated atrocities against the local population.[34] The Maratha atrocities were recorded by both Bengali and European sources, which reported that the Marathas demanded payments, and tortured and killed anyone who couldn't pay. Dutch sources estimate a total of 400,000 people in Bengal were killed by the Marathas. According to Bengali sources, the atrocities led to much of the local population opposing the Marathas and increasing support for the Nawabs.[34]

Maratha's Afghan conquests

- Balaji Bajirao encouraged agriculture, protected the villagers and brought about a marked improvement in the state of the territory. Continued expansion saw Raghunath Rao, brother of Nanasaheb, pushing into in the wake of the Afghan withdrawal after Ahmed Shah Abdali's plunder of Delhi in 1756. Delhi was captured by the Maratha army under Raghunath Rao in August 1757 defeating Afghan garrison in the Battle of Delhi. This laid the foundation for the Maratha conquest of North-west India. In Lahore, as in Delhi, the Marathas were now major players.[35] After Battle of Attock, 1758, the Marathas captured Peshawar defeating the Afghan troops in the Battle of Peshawar on 8 May 1758.[8] As noted by J.C. Grant Duff:

The pre-eminence to which the Mahrattas had attained was animating and glorious; their right to tribute was acknowledged on the banks of the Coleroon (the lower Kaveri in Tamil Nadu) and the Deccan horse had quenched their thirst from the waters of the Indus.[36]

Maratha invasion of Delhi and Rohilkhand

Just prior to the battle of Panipat in 1761, Marathas looted "Diwan-i-Khas" or Hall of Private Audiences in the Red Fort of Delhi, which was the place where the Mughal emperors used to receive courtiers and state guests, in one of their expeditions of Delhi.

"The Marathas who were hard pressed for money stripped the ceiling of Diwan-i-Khas of its silver and looted the shrines dedicated to Muslim saints".[37]

During the Maratha invasion of Rohilkhand in the 1750s

"The Marathas defeated the Rohillas, forced them to seek shelter in hills and ransacked their country in such a manner that the Rohillas dreaded the Marathas and hated them ever afterwards".[37]

Third battle of Panipat

In 1759, The Marathas under Sadashivrao Bhau (referred to as the Bhau or Bhao in sources) responded to the news of the Afghans' return to North India by sending a big army North. Bhau's force was bolstered by some Maratha forces under Holkar, Scindia, Gaikwad and Govind Pant Bundele. The combined army of over 100,000 regular troops had re-captured the former Mughal capital, Delhi, from an Afghan garrison in August 1760.[38] Delhi had been reduced to ashes many times due to previous invasions and in addition there being acute shortage of supplies in the Maratha camp. Bhau ordered the sacking of the already depopulated city.[37][39] He is said to have planned to place his nephew and the Peshwa's son, Vishwasrao, on the Mughal throne. By 1760, with defeat of the Nizam in the Deccan, Maratha power had reached its zenith with a territory of over 2,500,000 km² acres.[40]

Ahmad Shah Durrani, then called the Rohillas and the Nawab of Oudh to assist him in driving out the Marathas from Delhi.[citation needed] Huge armies of Muslim forces and Marathas collided with each other on January 14, 1761 in the Third Battle of Panipat. The Maratha Army lost the battle which halted their imperial expansion. The Jats and Rajputs did not support the Marathas. Their withdrawal from the ensuing battle played a crucial role in its result.[citation needed] Historians have criticised the Maratha treatment of fellow Hindu groups. Kaushik Roy says "The treatment of Marathas with their co-religionist fellows – Jats and Rajputs was definitely unfair and ultimately they had to pay its price in Panipat where Muslim forces had united in the name of religion."[35] The Marathas had antagonised the Jats and Rajputs by taxing them heavily, punishing them after defeating the Mughals and interfering in their internal affairs. The Marathas were abandoned by Raja Suraj Mal of Bharatpur and the Rajputs who quit the Maratha alliance at Agra before the start of the great battle and withdrew their troops as Maratha general Sadashivrao Bhau did not heed the advice to leave soldier's families (women and children) and pilgrims at Agra and not take them to the battle field with the soldiers, rejected their co-operation. Their supply chains (earlier assured by Raja Suraj Mal and Rajputs) did not exist.[citation needed]

Peshwa Madhav Rao I

Peshwa Madhavrao I was the fourth Peshwa of the Maratha Empire. It was during his tenure that the Maratha Resurrection took place. He worked as a unifying force in the Maratha Empire and moved to the south to subdue Nizam and Mysore to assert Maratha power. He sent generals such as Bhonsle, Scindia and Holkar to the north, where they re-established Maratha authority by the early 1770s.[citation needed]

Prof G. S. Chhabra wrote:

Young though he was, Madhav Rao had a cool and calculating head of a seasoned and experienced man. The diplomacy by which he could win over his uncle Raghoba when he had no strength to fight and the way he could crush his power when he had the means to do so later on proved in him a genius who knows when and how to act. The formidable power of the Nizam was crushed, Hyder Ali, who was a terror even to the British, was effectually humbled and before he died in 1772, the Marathas were almost there in the north where they had been before Panipat. What could not have the Marathas achieved if Madhav had continued living just for a few years more? Destiny was not in favour of the Marathas, the death of Madhav was a greater blow than their defeat of Panipat and from this blow they could never again recover.[41]

Madhav Rao died in 1772, at the age of 27. His death is considered to be a fatal blow to the Maratha Empire and from that time Maratha power started to move on a downward trajectory, less an empire than a confederacy.[citation needed]

Confederacy era

In a bid to effectively manage the large empire, Madhavrao Peshwa gave semi-autonomy to the strongest of the knights. After the death of Peshwa Madhavrao I, various chiefs and statesman became de facto rulers and regents for the infant Peshwa Madhavrao II.[citation needed] Thus, the semi-autonomous Maratha states came into being in far-flung regions of the empire:[citation needed]

- Peshwas of Pune

- Gaekwads of Baroda

- Holkars of Indore

- Scindias (aka Shindes) of Gwalior (Chambal region) and Ujjain (Malwa Region)

- Bhonsales of Nagpur (no blood relation with Shivaji's or Tarabai's family)

- Puars (or Pawars) of Dewas and Dhar

- Even in the original kingdom of Shivaji itself, many knights were given semi-autonomous charges of small districts, which led to princely states Sangli, Aundh, Bhor, Bawda, Phaltan, Miraj, etc. Pawars of Udgir were also part of confederacy.

Major events

- After the 1761 Battle of Panipat, Malhar Rao Holkar attacked the Rajputs and defeated them at the battle of Mangrol. This largely restored Maratha power in Rajasthan.[42]

- Under the leadership of Mahadji Shinde, the ruler of the state of Gwalior in central India, the Marathas defeated the Jats, the Rohilla Afghans and took Delhi which remained under Maratha control for the next three decades.[43] His forces conquered modern day Haryana[44] Shinde was instrumental in resurrecting Maratha power after the débâcle of the Third Battle of Panipat, and in this he was assisted by Benoît de Boigne.

- In 1767 Madhavrao I crossed the Krishna River and defeated Hyder Ali in the battles of Sira and Madgiri. He also rescued the last queen of the Keladi Nayaka Kingdom, who had been kept in confinement by Hyder Ali in the fort of Madgiri.[45]

- In early 1771, ten years after the collapse of Maratha authority over North India following the Third Battle of Panipat, Mahadji recaptured Delhi and installed Shah Alam II as a puppet ruler on the Mughal throne.[46] receiving in return the title of deputy Vakil-ul-Mutlak or vice-regent of the Empire and that of Vakil-ul-Mutlak being at his request conferred on the Peshwa. The Mughals also gave him the title of Amir-ul-Amara (head of the amirs).[47]

- After taking control of Delhi, the Marathas sent a large army in 1772 to punish Afghan Rohillas for their involvement in Panipat. Their army devastated Rohilkhand by looting and plundering as well as taking members of the royal family as captives.[46]

- After the growth in power of feudal lords like Malwa sardars, landlords of Bundelkhand and Rajput kingdoms of Rajasthan, they refused to pay tribute to Mahadji. So he sent his army conquer the states such as Bhopal, Datiya, Chanderi, Narwar, Salbai and Gohad. However, he launched an unsuccessful expedition against the Raja of Jaipur, but withdrew after the inconclusive Battle of Lalsot in 1787.[48]

- The Battle of Gajendragad was fought between the Marathas under the command of Tukojirao Holkar (the adopted son of Malharrao Holkar) and Tipu Sultan from March 1786 to March 1787 in which Tipu Sultan was defeated by the Marathas. By the victory in this battle, the border of the Maratha territory extended till Tungabhadra river.[49]

- The strong fort of Gwalior was then in the hands of Chhatar Singh, the Jat ruler of Gohad. In 1783, Mahadji besieged the fort of Gwalior and conquered it. He delegated the administration of Gwalior to Khanderao Hari Bhalerao. After celebrating the conquest of Gwalior, Mahadji Shinde turned his attention to Delhi again.[50]

- In 1788, Mahadji's armies defeated Ismail Beg, a Mughal noble who resisted the Marathas.[51] The Rohilla chief Ghulam Kadir, Ismail Beg's ally, took over Delhi, capital of the Mughal dynasty and deposed and blinded the king Shah Alam II, placing a puppet on the Delhi throne. Mahadji intervened and killed him, taking possession of Delhi on October 02 restoring Shah Alam II to the throne and acting as his protector.[52]

- Jaipur and Jodhpur, the two most powerful Rajput states, were still out of direct Maratha domination. So, Mahadji sent his general Benoît de Boigne to crush the forces of Jaipur and Jodhpur at the Battle of Patan.[53] Marwar was also captured on September 10, 1790.

- Another achievement of the Marathas was their victories over the Nizam of Hyderabad's armies including in the Battle of Kharda.[54][55]

Mysore war, Sringeri sacking, British alliance

The Marathas came into conflict with Tipu Sultan and his Kingdom of Mysore, leading to the Maratha–Mysore War in 1785. The war ended in 1787 with the Marathas being defeated by Tipu Sultan.[56] In 1791-92, large areas of the Maratha Confederacy suffered massive population loss due to the Doji bara famine.[57]

In 1791, the Maratha army raided and sacked the temple of Sringeri Shankaracharya, killing and wounding many people including Brahmins, plundering the monastery of all its valuable possessions, and desecrating the temple by displacing the image of goddess Sarada. The incumbent Shankaracharya petitioned Tipu Sultan for help. A bunch of about 30 letters written in Kannada, which were exchanged between Tipu Sultan's court and the Sringeri Shankaracharya were discovered in 1916 by the Director of Archaeology in Mysore. Tipu Sultan expressed his indignation and grief at the news of the raid:[58]

"People who have sinned against such a holy place are sure to suffer the consequences of their misdeeds at no distant date in this Kali age in accordance with the verse: "Hasadbhih kriyate karma rudadbhir-anubhuyate" (People do [evil] deeds smilingly but suffer the consequences crying)."[59]

Tipu Sultan immediately ordered the Asaf of Bednur to supply the Swami with 200 rahatis (fanams) in cash and other gifts and articles. Tipu Sultan's interest in the Sringeri temple continued for many years, and he was still writing to the Swami in the 1790s.[60]

The Maratha Empire soon allied with the British East India Company (based in the Bengal Presidency) against Mysore in the Anglo-Mysore Wars. After the British had suffered defeat against Mysore in the first two Anglo-Mysore War, the Maratha cavalry assisted the British in the last two Anglo-Mysore Wars from 1790 onwards, eventually helping the British conquer Mysore in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War in 1799.[61] After the British conquest, however, the Marathas launched frequent raids in Mysore to plunder the region, which they justified as compensation for past losses to Tipu Sultan.[62]

British intervention

In 1775, the British East India Company, from its base in Bombay, intervened in a succession struggle in Pune, on behalf of Raghunathrao (also called Raghobadada), who wanted to become Peshwa of the empire. Marathas forces under Tukojirao Holkar and Mahadaji Shinde defeated a British expeditionary force at the Battle of Wadgaon, but the heavy surrender terms, which included the return of annexed territory and a share of revenues, were disavowed by the British authorities at Bengal and fighting continued. What became known as the First Anglo-Maratha War ended in 1782 with a restoration of the pre-war status quo and the East India Company's abandonment of Raghunathrao's cause.[63]

In 1799, Yashwantrao Holkar was crowned King of Holkars, he captured Ujjain. He started campaigning towards the north to expand his empire in that region. Yashwant Rao rebelled against the policies of the Peshwa Baji Rao II. In May 1802, he marched towards Pune the seat of the Peshwa. This gave rise to the Battle of Poona in which the Peshwa was defeated. After the Battle of Poona, the flight of Peshwa left the government of Maratha state in the hands of Yashwantrao Holkar.[64] He appointed Amrutrao as the Peshwa and went to Indore on March 13, 1803. All except Gaikwad chief of Baroda, who had already accepted British protection by a separate treaty on July 26, 1802, supported the new regime. He made a treaty with the British. Also, Yashwant-Rao successfully resolved the disputes with Scindia and the Peshwa. He tried to unite the Maratha Confederacy but to no avail. In 1802, the British intervened in Baroda to support the heir to the throne against rival claimants and they signed a treaty with the new Maharaja recognising his independence from the Maratha Empire in return for his acknowledgement of British paramountcy. Before the Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803–1805), the Peshwa Baji Rao II signed a similar treaty. The defeat in Battle of Delhi, 1803 during Second Anglo-Maratha War resulted in the loss of the city of Delhi for the Marathas.[65]

The Second Anglo-Maratha War represents the military high-water mark of the Marathas who posed the last serious opposition to the formation of the British Raj. The real contest for India was never a single decisive battle for the subcontinent. Rather it turned on a complex social and political struggle for control of the South Asian military economy. The victory in 1803 hinged as much on finance, diplomacy, politics and intelligence as it did on battlefield manoeuvre and war itself.[66]

Ultimately, the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818) resulted in the loss of Maratha independence. It left the British in control of most of India. The Peshwa was exiled to Bithoor (Marat, near Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh) as a pensioner of the British. The Maratha heartland of Desh, including Pune, came under direct British rule, with the exception of the states of Kolhapur and Satara, which retained local Maratha rulers (descendants of Shivaji and Sambhaji II ruled over Kolhapur). The Maratha-ruled states of Gwalior, Indore, and Nagpur all lost territory and came under subordinate alliance with the British Raj as princely states that retained internal sovereignty under British paramountcy. Other small princely states of Maratha knights were retained under the British Raj as well.[citation needed]

The Third Anglo-Maratha War was fought by Maratha war lords separately instead of forming a common front and they surrendered one by one. Shinde and the Pashtun Amir Khan were subdued by the use of diplomacy and pressure, which resulted in the Treaty of Gwalior[67] on November 05, 1817.[citation needed] All other Maratha chiefs like Holkars, Bhonsles and Peshwa gave up arms by 1818. British historian Percival Spear describes 1818 as a watershed year in the history of India, saying that by the year "the British dominion in India became the British dominion of India".[68][69]

The war left the British, under the auspices of the British East India Company, in control of virtually all of present-day India south of the Sutlej River. The famed Nassak Diamond was acquired by the Company as part of the spoils of the war.[70] The British acquired large chunks of territory from the Maratha Empire and in effect put an end to their most dynamic opposition.[71] The terms of surrender Major-general John Malcolm offered to the Peshwa were controversial amongst the British for being too liberal: The Peshwa was offered a luxurious life near Kanpur and given a pension of about 80,000 pounds.[citation needed]

Administration

The Ashtapradhan (The Council of Eight) was a council of eight ministers that administered the Maratha empire. This system was formed by Shivaji.[72] Ministerial designations were drawn from the Sanskrit language and comprised:[citation needed]

- Pantpradhan or Peshwa – Prime Minister, general administration of the Empire

- Amatya or Mazumdar – Finance Minister, managing accounts of the Empire[73][unreliable source?]

- Sachiv – Secretary, preparing royal edicts

- Mantrin – Interior Minister, managing internal affairs especially intelligence and espionage

- Senapati – Commander-in-Chief, managing the forces and defence of the Empire

- Sumant – Foreign Minister, to manage relationships with other sovereigns

- Nyayadhyaksh – Chief Justice, dispensing justice on civil and criminal matters

- Panditrao – High Priest, managing internal religious matters

With the notable exception of the priestly Panditrao and the judicial Nyayadisha, the other pradhans held full-time military commands and their deputies performed their civil duties in their stead. In the later era of the Maratha Empire, these deputies and their staff constituted the core of the Peshwa's bureaucracy.[citation needed]

The Peshwa was the titular equivalent of a modern Prime Minister. Shivaji created the Peshwa designation in order to more effectively delegate administrative duties during the growth of the Maratha Empire. Prior to 1749, Peshwas held office for 8–9 years and controlled the Maratha Army. They later became the de facto hereditary administrators of the Maratha Empire from 1749 till its end in 1818.[citation needed]

Under Peshwa administration and with the support of several key generals and diplomats (listed below), the Maratha Empire reached its zenith, ruling most of the Indian subcontinent. It was also under the Peshwas that the Maratha Empire came to its end through its formal annexation into the British Empire by the British East India Company in 1818.

The Marathas used a secular policy of administration and allowed complete freedom of religion.[74][full citation needed] There were many notable Muslims in the military and administration of Marathas like Ibrahim Khan Gardi, Haider Ali Kohari, Daulat Khan, Siddi Ibrahim, and Jiva Mahal.[citation needed]

Shivaji was an able administrator who established a government that included modern concepts such as cabinet, foreign policy and internal intelligence.[citation needed] He established an effective civil and military administration. He believed that there was a close bond between the state and the citizens. He is remembered as a just and welfare-minded king. Cosme da Guarda says of him that:[75]

Such was the good treatment Shivaji accorded to people and such was the honesty with which he observed the capitulations that none looked upon him without a feeling of love and confidence. By his people he was exceedingly loved. Both in matters of reward and punishment he was so impartial that while he lived he made no exception for any person; no merit was left unrewarded, no offence went unpunished; and this he did with so much care and attention that he specially charged his governors to inform him in writing of the conduct of his soldiers, mentioning in particular those who had distinguished themselves, and he would at once order their promotion, either in rank or in pay, according to their merit. He was naturally loved by all men of valor and good conduct.

Tax-collecting regime

Some foreign commentators at the time found Shivaji's tax-collecting regime oppressive, though others disagreed. English traveller John Fryer described poor people having land "imposed upon them at double the former Rates," and if they refused it, being "carried to Prison, there they are famished almost to death.[76] Muslim writers at the time also described his country as "the worst possible state" and mentioned Shivaji as a "depredator and destroyer". However, French physician Dellon reports that he was "looked upon as one of the most politic princes in those parts." Modern historian Philip MacDougall argues that local evidence seems to support the viewpoint of Dellon because of the high regard with which Shivaji was held. MacDougall argues that his government was demanding but rarely oppressive.[76]

Plunder and piracy

Shivaji relied on revenue collected through plunder, from raids conducted in territories either outside Maratha occupation or held by declared enemy states. While most of the income generated through plunder came from raids conducted by the Maratha army, the Maratha navy also took on an increasingly important role. In their first expedition in 1665, they were ordered to raid richer coastal ports and to capture merchants operating in the Arabian Sea. They later launched many similar sea raids, such as plunders targeting Mughal pilgrim ships and European trading vessels. European traders described these attacks as piracy, but the Marathas viewed them as legitimate targets because they were trading with, and thus financially supporting, their Mughal and Bijapur enemies. It was only after representatives of various European powers signed agreements with Shivaji or his successors that the threat of Maratha plundering raids against Europeans began to reduce.[77]

Geography

The Maratha Empire, at its peak, ruled over a large area in the Indian sub-continent. Apart from capturing various regions, the Marathas maintained a large number of tributaries who were bounded by agreement to pay a certain amount of regular tax, known as Chauth. The empire defeated the Sultanate of Mysore under Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan, Nawab of Oudh, Nawab of Bengal, Nizam of Hyderabad and Nawab of Arcot as well as the Polygar kingdoms of South India. They extracted chauth from the rulers in Delhi, Oudh, Bengal, Bihar, Odisha, Punjab, Hyderabad, Mysore, Uttar Pradesh and Rajputana.[78][79]

The Marathas were requested by Safdarjung, the Nawab of Oudh, in 1752 to help him defeat Afghani Rohilla. The Maratha force left Pune and defeated Afghan Rohilla in 1752, capturing the whole of Rohilkhand (present-day northwestern Uttar Pradesh).[37] In 1752, Marathas entered into an agreement with the Mughal emperor, through his wazir, Safdarjung, Mughals gave Marathas the chauth of Punjab, Sindh and Doab in addition to the subedari of Ajmer and Agra.[80] In 1758, Marathas started their north-west conquest and expanded their boundary till Afghanistan. They defeated Afghan forces of Ahmed Shah Abdali, in what is now Pakistan, including Pakistani Punjab Province and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The Afghans were numbered around 25,000–30,000 and were led by Timur Shah, the son of Ahmad Shah Durrani. The Marathas massacred and looted thousands of Afghan soldiers and captured Lahore, Multan, Dera Ghazi Khan, Attock, Peshawar in the Punjab region and Kashmir.[81][82]

During the confederacy era, Mahadji Sindhia resurrected the Maratha domination on much of North India, which was lost after the Third battle of Panipat including the cis-Sutlej states (south of Sutlej) like Kaithal, Patiala, Jind, Thanesar, Maler Kotla and Faridkot, Delhi and Uttar Pradesh were under the suzerainty of the Scindhias of the Maratha Empire, following the Second Anglo-Maratha War of 1803–1805, Marathas lost these territories to the British East India Company.[47][83]

Legacy

The Maratha Empire is credited with laying the foundation of the Indian Navy and bringing about considerable changes in naval warfare by introducing a blue-water navy. From its inception in 1674, the Marathas established a naval force, consisting of cannons mounted on ships.[citation needed] The 'Pal' was a three-masted Maratha man-of-war with guns on its broadsides.[citation needed]

The dominance of the Maratha Navy started with the ascent of Kanhoji Angre as the Darya-Saranga by the Maratha chief of Satara.[84][unreliable source?] Under that authority, he was admiral of the Western coast of India from Bombay to Vingoria (now Vengurla) in the present day state of Maharashtra, except for Janjira which was affiliated with the Mughal Empire.[citation needed]

The Marathas established watch posts on Andaman Islands and are credited with attaching those islands to India.[85][unreliable source?] He attacked English, Dutch and Portuguese ships which were moving to and from East Indies. Until his death in 1729, he repeatedly attacked the colonial powers of Britain and Portugal, capturing numerous vessels of the British East India Company and extracting ransom for their return.[citation needed]

On November 29, 1721, a joint attempt by the Portuguese Viceroy Francisco José de Sampaio e Castro and the British General Robert Cowan to humble Kanhoji failed miserably. Their combined fleet consisted of 6,000 soldiers in no less than four Man-of-war besides other ships led by Captain Thomas Mathews of the Bombay Marine. Aided by the Maratha naval commanders Mendhaji Bhatkar and Mainak Bhandari, Kanhoji continued to harass and plunder the European ships until his death in 1729.[citation needed]

Military

The Maratha army was not homogenous, but employed soldiers of different backgrounds, both locals and foreign mercenaries, including large numbers of Arabs, Sikhs, Rajputs, Sindhis, Rohillas, Abyssinians, Pathans, Topiwalas and Europeans. The army of Nana Fadnavis, for example, included 5,000 Arabs.[86]

Afghan accounts

The Maratha army, especially its infantry, was praised by almost all the enemies of Maratha Empire, ranging from Duke of Wellington to Ahmad Shah Abdali. After the Third Battle of Panipat, Abdali was relieved as Maratha army in the initial stages were almost in the position of destroying the Afghan armies and their Indian Allies Nawab of Oudh and Rohillas. The grand wazir of Durrani Empire, Sardar Shah Wali Khan was shocked when Maratha commander-in-chief Sadashivrao Bhau launched a fierce assault on the centre of Afghan Army, over 3,000 Durrani soldiers were killed alongside Haji Atai Khan, one of the chief commander of Afghan army and nephew of wazir Shah Wali Khan. Such was the fierce assault of Maratha infantry in hand-to-hand combat that Afghan armies started to flee and the wazir in desperation and rage shouted, "Comrades Whither do you fly, our country is far off".[87] Post battle, Ahmad Shah Abdali in a letter to one Indian ruler claimed that Afghans were able to defeat the Marathas only because of the blessings of almighty and any other army would have been destroyed by the Maratha army on that particular day even though Maratha army was numerically inferior to Afghan army and its Indian allies.[88][full citation needed] Though Abdali won the battle, he also had heavy casualties on his side. So, he sought immediate peace with the Marathas. Abdali wrote in his letter to Peshwa on February 10, 1761:

There is no reason to have animosity amongst us. Your son Vishwasrao and your brother Sadashivrao died in battle, was unfortunate. Bhau started the battle, so I had to fight back unwillingly. Yet I feel sorry for his death. Please continue your guardianship of Delhi as before, to that I have no opposition. Only let Punjab until Sutlaj remain with us. Reinstate Shah Alam on Delhi's throne as you did before and let there be peace and friendship between us, this is my ardent desire. Grant me that desire.[89]

European accounts

Similarly, the Duke of Wellington, after defeating the Marathas, noted that the Marathas, though poorly led by their Generals, had regular infantry and artillery that matched the level of that of the Europeans and warned other British officers from underestimating the Marathas on the battlefield. He cautioned one British general that: "You must never allow Maratha infantry to attack head on or in close hand to hand combat as in that your army will cover itself with utter disgrace".[90] Even when Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, became the Prime Minister of Britain, he held the Maratha infantry in utmost respect, claiming it to be one of the best in the world. However, at the same time he noted the poor leadership of Maratha Generals, who were often responsible for their defeats.[90] Charles Metcalfe, one of the ablest of the British Officials in India and later acting Governor-General, wrote in 1806:

India contains no more than two great powers, British and Mahratta, and every other state acknowledges the influence of one or the other. Every inch that we recede will be occupied by them.[91][92]

Norman Gash says that the Maratha infantry was equal to that of British infantry. After the Third Anglo-Maratha war in 1818, Britain listed the Marathas as one of the Martial Races to serve in the British Indian Army.[93]

The 19th century diplomat Sir Justin Sheil commented about the British East India Company copying the French Indian army in raising an army of Indians:

It is to the military genius of the French that we are indebted for the formation of the Indian army. Our warlike neighbours were the first to introduce into India the system of drilling native troops and converting them into a regularly disciplined force. Their example was copied by us, and the result is what we now behold. The French carried to Persia the same military and administrative faculties, and established the origin of the present Persian regular army, as it is styled. When Napoleon the Great resolved to take Iran under his auspices, he dispatched several officers of superior intelligence to that country with the mission of General Gardanne in 1808. Those gentlemen commenced their operations in the provinces of Azerbaijan and Kermanshah, and it is said with considerable success.

— Sir Justin Sheil (1803-1871).[94]

Notable generals and administrators

Ramchandra Pant Amatya Bawdekar

Ramchandra Pant Amatya Bawdekar was a court administrator who rose from the ranks of a local Kulkarni to the ranks of Ashtapradhan under guidance and support of Shivaji. He was one of the prominent Peshwas from the time of Shivaji, prior to the rise of the later Peshwas who controlled the empire after Shahuji.[72]

When Rajaram fled to Jinji in 1689 leaving Maratha Empire, he gave a Hukumat Panha (King Status) to Pant before leaving. Ramchandra Pant managed the entire state under many challenges like influx of Mughals, betrayal from Vatandars (local satraps under the Maratha state) and social challenges like scarcity of food. With the help of Pantpratinidhi, Sachiv, he kept the economic condition of Maratha Empire in an appropriate state.

He received military help from the Maratha commanders – Santaji Ghorpade and Dhanaji Jadhav. On many occasions he himself participated in battles against Mughals.[citation needed]

In 1698, he stepped down from the post of Hukumat Panha when Rajaram offered this post to his wife, Tarabai. Tarabai gave an important position to Pant among senior administrators of Maratha State. He wrote Adnyapatra (मराठी: आज्ञापत्र) in which he has explained different techniques of war, maintenance of forts and administration etc. But owing to his loyalty to Tarabai against Shahuji (who was supported by more local satraps), he was sidelined after arrival of Shahuji in 1707.[citation needed]

Nana Phadnavis was an influential minister and statesman of the Maratha Empire during the Peshwa administration.After the assassination of Peshwa Narayanrao in 1773, Nana Phadnavis managed the affairs of the state with the help of a twelve-member regency council known as the Barbhai council and he remained the chief strategist of Maratha state till his death in 1800 AD.[95] Nana Phadnavis played a pivotal role in holding the Maratha Confederacy together in the midst of internal dissension and the growing power of British. Nana's administrative, diplomatic and financial skills brought prosperity to the Maratha Empire and his management of external affairs kept the Maratha Empire away from the thrust of the British East India Company.

Personalities

Royal houses

- Shivaji (1630–1680)

- Sambhaji (1657–1689)

- Rajaram Chhatrapati (1670–1700)

Satara:

- Chhattrapati Shahu (r. 1708–1749) (alias Shivaji II, son of Chhatrapati Sambhaji)

- Ramaraja II (nominally, grandson of Chhatrapati Rajaram and Queen Tarabai) (r. 1749–1777)

- Shahu II (r. 1777–1808)

- Pratap Singh (r. 1808–1839) - signed a treaty with the East India company ceding part of sovereignty to the company[96]

Kolhapur:

- Tarabai (1675–1761) (wife of Chhatrapati Rajaram) in the name of her son Shivaji II

- Shivaji II (1700–1714)

- Sambhaji II (1714 to 1760) - came to power by deposing his half brother Shivaji II

- Shivaji III (1760–1812) (adopted from the family of Khanwilkar)

Peshwas

- Moropant Trimbak Pingle (1657–1683)

- Bahiroji Pingale (1708–1711)

Peshwas From Bhat Family

From Balaji Vishwanath onwards, actual power gradually shifted to the Bhat family Peshwas based in Pune.

- Balaji Vishwanath (1713–1720)

- Bajirao (1720–1740)

- Balaji Bajirao (4 Jul.1740-23 Jun.1761) (b. 8 Dec. 1721, d. 23 Jun.1761)

- Madhavrao Peshwa (1761–18 Nov.1772) (b. 16 Feb 1745, d. 18 Nov 1772)

- Narayanrao Bajirao (13 Dec. 1772–30 Aug.1773) (b. 10 Aug.1755, d. 30 Aug.1773)

- Raghunathrao (5 Dec. 1773–1774) (b. 18 Aug.1734, d. 11 Dec. 1783)

- Sawai Madhava Rao II Narayan (1774–27 Oct.1795) (b. 18 Apr.1774, d. 27 Oct.1795)

- Baji Rao II (6 Dec. 1796 – 3 Jun.1818) (d. 28 Jan.1851)

Clans

- Holkars of Indore

- Scindias of Gwalior

- Gaikwads of Baroda

- Bhonsales of Nagpur

- Puarss of Dewas and Dhar

Maps showing the Maratha Empire at different stages of history

-

Maratha kingdom in 1680 (green)

-

Maratha Empire in 1760 (yellow)

-

Maratha Empire in 1765 (yellow)

-

Maratha Empire in 1794 (yellow)

-

Maratha Empire in 1805 (yellow)

Thanjavur Maratha Kingdom (Tamil Nadu)

The Thanjavur Marathas were the rulers of Thanjavur principality of Tamil Nadu between the 17th and 19th centuries. Their native language was Thanjavur Marathi. Venkoji, Shahaji's son and Shivaji's half brother, was the founder of the dynasty.[97]

List of rulers of Thanjavur Maratha dynasty :

- Venkoji

- Shahuji I of Thanjavur

- Serfoji I

- Tukkoji

- Pratapsingh of Thanjavur

- Thuljaji

- Serfoji II

- Shivaji II of Thanjavur

See also

- Maratha clan system

- List of Maratha dynasties and states

- Maratha War of Independence

- Battles involving the Maratha Empire

- Maratha titles

- Thanjavur Maratha kingdom

- List of people involved in the Maratha Empire

Footnotes

Citations

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=oUTRAAAAMAAJ

- ^ Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2007). The Mughul Empire, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, ISBN 81-7276-407-1, pp. 609, 634.

- ^ a b c Pearson, M. N. (February 1976). "Shivaji and the Decline of the Mughal Empire". The Journal of Asian Studies. 35 (2): 221–235. doi:10.2307/2053980. JSTOR 2053980.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Delhi, the Capital of India By Anon, John Capper, p.28. "This source establishes the Maratha control of Delhi before the British"

- ^ An Advanced History of Modern India By Sailendra Nath Sen p.Introduction-14. The author says: "The victory at Bhopal in 1738 established Maratha dominance at the Mughal court"

- ^ The Journal of Asian Studies The Journal of Asian Studies / Volume 21 / Issue 04 / August 1962, pp 577-578

- ^ Mehta (2005), p. 204 sfnp error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFMehta2005 (help)

- ^ a b An Advanced History of Modern India By Sailendra Nath Sen, p.16

- ^ Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bharatiya Itihasa Samiti, Ramesh Chandra Majumdar – The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Maratha supremacy

- ^ Naravane, M.S. (2014). Battles of the Honorourable East India Company. A.P.H. Publishing Corporation. p. 63. ISBN 9788131300343.

- ^ Pagadi, Setumadhavarao S. (1993). Shivaji. National Book Trust. p. 21. ISBN 81-237-0647-2.

- ^ Jones, Rodney W. (1974). Urban Politics in India: Area, Power, and Policy in a Penetrated System. University of California Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-520-02545-5.

- ^ Gokhale, Balkrishna Govind (1988). Poona in the eighteenth century: an urban history. Oxford University Press. p. 112.

- ^ Jackson, William Joseph (2005). Vijayanagara voices: exploring South Indian history and Hindu literature. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-7546-3950-3.

- ^ Vartak, Malavika (8–14 May 1999). "Shivaji Maharaj: Growth of a Symbol". Economic and Political Weekly. 34 (19): 1126–1134. JSTOR 4407933.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ M. R. Kantak (1993). The First Anglo-Maratha War, 1774–1783: A Military Study of Major Battles. Popular Prakashan. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-81-7154-696-1.

- ^ Mehta (2005), p. 707:quote:It explains the rise to power of his Peshwa (prime minister) Balaji Vishwanath (1713–20) and the transformation of the Maratha kingdom into a vast empire, by the collective action of all the Maratha stalwarts. sfnp error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFMehta2005 (help)

- ^ Richards, J.F. (1995). Mughal empire (Transferred to digital print. ed.). Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-0521566032. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ John F. Richards (1995). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. pp. 217–223.

- ^ Richards, J.F. (1995). Mughal empire (Transferred to digital print. ed.). Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0521566032. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ a b An Advanced History of Modern India By Sailendra Nath Sen, p.11

- ^ An Advanced History of Modern India By Sailendra Nath Sen, p11

- ^ Mehta, J. L. (2005). Advanced study in the history of modern India, 1707-1813. Slough: New Dawn Press, Inc. p. 81. ISBN 9781932705546.

- ^ Mehta, J. L. (2005). Advanced study in the history of modern India, 1707-1813. Slough: New Dawn Press, Inc. pp. 101–103. ISBN 9781932705546.

- ^ a b An Advanced History of Modern India By Sailendra Nath Sen, p.12

- ^ The Concise History of Warfare By Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, p.132

- ^ J.L. Mehta, Advanced Study in the History of Modern India 1707–1813 (2005)

- ^ a b c S.N. Sen, History Modern India (3rd ed. 2006)

- ^ An Advanced History of Modern India

- ^ An Advanced History of Modern India By Sailendra Nath Sen, p13

- ^ Advanced Study in the History of Modern India 1707–1813 By Jaswant Lal Mehta, p 202

- ^ a b An Advanced History of Modern India By Sailendra Nath Sen, p.15

- ^ Fall Of The Mughal Empire- Volume 1 (4Th Edn.), J. N.Sarkar

- ^ a b P. J. Marshall (2006). Bengal: The British Bridgehead: Eastern India 1740-1828. Cambridge University Press. pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Roy, Kaushik. India's Historic Battles: From Alexander the Great to Kargil. Permanent Black, India. pp. 80–1. ISBN 978-81-7824-109-8.

- ^ Duff, J.C. Grant, A History of the Mahrattas, vol.1, p.507

- ^ a b c d Agrawal, Ashvini (1983). "Events leading to the Battle of Panipat". Studies in Mughal History. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 26. ISBN 81-208-2326-5.

- ^ Mehta, Advanced Study in the History of Modern India 1707–1813, p.140

- ^ Mehta (2005), p. 274 sfnp error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFMehta2005 (help)

- ^ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of world-systems research. 12 (2): 223. ISSN 1076-156X

- ^ Advance Study in the History of Modern India (Volume-1: 1707–1803) By G.S.Chhabra, p.56

- ^ The Marathas 1600–1818, Band 2 by Stewart Gordon p.157

- ^ The Marathas 1600–1818, Band 2 by Stewart Gordon p.158

- ^ "Haryana, a Historical Perspective". google.co.in.

- ^ Mehta (2005), p. 458 sfnp error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFMehta2005 (help)

- ^ a b Rathod (1994), p. 8

- ^ a b A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: From Twelfth to the Mid ... – Farooqui Salma Ahmed, Salma Ahmed Farooqui – Google Books.

- ^ The Great Maratha Mahadaji Scindia By N. G. Rathod, p.95

- ^ "SPLENDOURS OF ROYAL MYSORE (PB)". google.co.in.

- ^ The Great Maratha Mahadaji Scindia By N. G. Rathod, p.30

- ^ Rathod (1994), p. 106

- ^ "Marathas and the Marathas Country: The Marathas". google.co.in.

- ^ Sir Jadunath Sarkar (1994). A History of Jaipur 1503–1938. Orient Longman. ISBN 81-250-0333-9.

- ^ Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bhāratīya Itihāsa Samiti, Ramesh Chandra Majumdar. The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Maratha supremacy

- ^ The State at War in South Asia By Pradeep Barua, p.91

- ^ Mohibbul Hasan, History of Tipu Sultan, pp. 105–107

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III 1907, p. 502

- ^ Mohibbul Hasan, History of Tipu Sultan, p. 358

- ^ Annual Report of the Mysore Archaeological Department 1916 pp 10–11, 73–6

- ^ Hasan, History of Tipu Sultan, p. 359

- ^ Randolf G. S. Cooper (2003). The Anglo-Maratha Campaigns and the Contest for India: The Struggle for Control of the South Asian Military Economy. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Randolf G. S. Cooper (2003). The Anglo-Maratha Campaigns and the Contest for India: The Struggle for Control of the South Asian Military Economy. Cambridge University Press. p. 69.

- ^ Battle of Wadgaon, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ C A Kincaid and D B Parasnis, A history of the Maratha people. Vol III p. 194.

- ^ Delhi, the Capital of India By Anon, John Capper, p.28

- ^ The Anglo-Maratha Campaigns and the Contest for India, Randolf G. S. Cooper, University of Cambridge, ISBN 978-0-521-03646-7, 2007

- ^ Prakash 2002, p. 300.

- ^ Pramod K. Nayar (25 March 2008). English Writing and India, 1600–1920: Colonizing Aesthetics. Routledge. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-134-13150-1.

- ^ Harish Trivedi; Richard Allen (2000). Literature and Nation. Psychology Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-415-21207-6.

- ^ United States Court of Customs and Patent Appeals 1930, p. 121.

- ^ Black 2006, p. 77.

- ^ a b Shivaji, the great Maratha, Volume 2, H. S. Sardesai, Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd, 2002, ISBN 81-7755-286-4, ISBN 978-81-7755-286-7

- ^ http://www.kkhsou.in/main/history/marathas.html

- ^ Maratha Rule in India By Stephen Meredyth Edwardes, Herbert Leonard Offley Garrett p. 116.

- ^ Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bhāratīya Itihāsa Samiti, Ramesh Chandra Majumdar. The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Maratha supremacy. G. Allen & Unwin, 1951

- ^ a b Philip MacDougall (2014). Naval Resistance to Britain's Growing Power in India, 1660-1800: The Saffron Banner and the Tiger of Mysore. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 64–65.

- ^ Philip MacDougall (2014). Naval Resistance to Britain's Growing Power in India, 1660-1800: The Saffron Banner and the Tiger of Mysore. Boydell & Brewer. p. 65.

- ^ The New Cambridge Modern History – Google Books. Books.google.co.in. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ History of Medieval India – Saini A.K, Chand, Hukam – Google Books. Books.google.co.in. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ "History Modern India". google.co.in.

- ^ War, Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740–1849 – Kaushik Roy – Google Books. Books.google.co.in. 30 March 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ "The Cambridge History of India". google.co.in.

- ^ History of the Marathas – R.S. Chaurasia.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Andaman & Nicobar Origin | Andaman & Nicobar Island History. Andamanonline.in. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bhāratīya Itihāsa Samiti, Ramesh Chandra Majumdar. The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Maratha Supremacy, page 512. G. Allen & Unwin, 1951

- ^ [1] Fall of Mughal Empire: Vol.2

- ^ "Indian Military Thought". google.co.in.

- ^ G S Sardesai's Marathi Riyasat, volume 2."The reference for this letter as given by Sardesai in Riyasat – Peshwe Daftar letters 2.103, 146; 21.206; 1.202, 207, 210, 213; 29, 42, 54, and 39.161. Satara Daftar – document number 2.301, Shejwalkar's Panipat, page no. 99. Moropanta's account – 1.1, 6, 7"

- ^ a b "Empires and Indigenes". google.co.in.

- ^ "Full text of "Selections from the papers of Lord Metcalfe; late governor-general of India, governor of Jamaica, and governor-general of Canada"". archive.org.

- ^ The Discovery Of India.

- ^ "Wellington". google.co.in.

- ^ Glimpses of Life and Manners in Persia by Lady Mary Leonora Woulfe Sheil, with additional notes by Sir Justin Sheil [2]

- ^ Great Personalities By Prof. R. P. Chaturvedi, p.189

- ^ Kulkarni, Sumitra (1995). The Satara Raj, 1818–1848: A Study in History, Administration, and Culture. Mittal Publications. pp. 21–24. ISBN 978-81-7099-581-4.

- ^ Journal of the Tanjore Maharaja Serfoji's Sarasvati Mahal Library Pg 18

Bibliography

- Beck, Sanderson. India & Southeast Asia to 1800 (2006) "Marathas and the English Company 1701-1818" online. Retrieved Oct. 1, 2004.

- Gordon, Stewart. Marathas, marauders, and state formation in eighteenth-century India (Oxford University Press, 1994).

- Gordon, Stewart. "The Marathas," in New Cambridge History of India, vol II. ch 4, (Cambridge U Press, 1993).

- Kumar, Ravinder. Western India in the nineteenth century (Routledge, 2013).

- Laine, James W. Shivaji: Hindu King in Islamic India (New York, 2003).

- McEldowney, Philip F (1966), Pindari Society and the Establishment of British Paramountcy in India, Madison: University of Wisconsin, OCLC 53790277

- Mehta, J. L (2005), Advanced Study in the History of Modern India 1707–1813, vol. II, Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd, ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6

- MacDougall, Philip (2014). Naval Resistance to Britain's Growing Power in India, 1660-1800: The Saffron Banner and the Tiger of Mysore ISBN 9781843839484

- Moon, Penderel. The British Conquest and Dominion of India: Part One 1745-1857 (1989).

- Roy, Tirthankar. "Rethinking the origins of British India: state formation and military-fiscal undertakings in an eighteenth century world region." Modern Asian Studies 47.4 (2013): 1125+ online

- Sardesai, Govind Sakharam. New history of the Marathas, vol. I: Shivaji and his line, 1600-1707 (Phoenix publications, 1946).

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1994), Anglo-Maratha Relations, 1785–96, vol. Volume 2 of Anglo-Maratha Relations, Sailendra Nath Sen, Bombay: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-789-0

{{citation}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Sen, S.N. History Modern India (3rd ed. 2006) online

- Seshan, Radhika. "The Maratha State: Some Preliminary Considerations." Indian Historical Review 41.1 (2014): 35-46. online

- Wink, Andre. Land and Sovereignty in India: Agrarian Society and Politics under the Eighteenth Century Maratha Swarajya, (Cambridge UP, 1986).

- Bombay University – Maratha History – Seminar Volume

- Samant, S. D. – Vedh Mahamanavacha

- Kasar, D.B. – Rigveda to Raigarh making of Shivaji the great, Mumbai: Manudevi Prakashan (2005)

- Apte, B.K. (editor) – Chhatrapati Shivaji: Coronation Tercentenary Commemoration Volume, Bombay: University of Bombay (1974–75)

- Desai, Ranjeet – Shivaji the Great, Janata Raja (1968), Pune: Balwant Printers – English Translation of popular Marathi book.

- Pagdi, Setu Madhavrao – Hindavi Swaraj Aani Moghul (1984), Girgaon Book Depot, Marathi book

- Deshpande, S.R. – Marathyanchi Manaswini, Lalit Publications, Marathi book

- Bakshi, S.R; Ralhan, O.P. (2007), Madhya Pradesh Through the Ages, New Delhi: Sarup & Sons, ISBN 978-81-7625-806-7

- Black, Jeremy (2006), A Military History of Britain: from 1775 to the Present, Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-275-99039-8

- Chhabra, G.S. (2005), Advance Study in the History of Modern India, vol. Volume 1: 1707–1803, New Delhi: Lotus Press, ISBN 81-89093-06-1

{{citation}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Government of Maharashtra (1961), Land Acquisition Act (PDF), Bombay

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kulkarni, Sumitra (1995), The Satara Raj, 1818–1848: A Study in History, Administration, and Culture, New Delhi: Mittal Publications, ISBN 978-81-7099-581-4

- McDonald, Ellen E. (1968), The Modernizing of Communication: Vernacular Publishing in Nineteenth Century Maharashtra, Berkeley: University of California Press, OCLC 483944794

- Nadkarni, Dnyaneshwar (2000), Husain: Riding The Lightning, Bombay: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 81-7154-676-5

- Naravane, M.S (2006), Battles of the Honourable East India Company: Making of the Raj, New Delhi: APH Publishing, pp. 78–105, ISBN 978-81-313-0034-3

- Prakash, Om (2002), Encyclopaedic History of Indian Freedom Movement, New Delhi: Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd., ISBN 978-81-261-0938-8

- Ramusack, Barbara N. (2004), The Indian Princes and their States, The New Cambridge History of India, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-44908-3

- Rathod, N. G. (1994), The Great Maratha Mahadaji Scindia

- Rao, S. Venugopala (1977), Power and Criminality: a Survey of Famous Crimes in Indian History, Bombay: Allied Publishers, OCLC 4076888

- Sarkar, Sumit; Pati, Biswamoy (2000), Biswamoy Pati (ed.), Issues in Modern Indian History: for Sumit Sarkar, Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-658-9

- Schmidt, Karl J. (1995), An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History, Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-1-56324-334-9

- United States Court of Customs and Patent Appeals (1930), Court of Customs and Patent Appeals Reports, vol. 18, Washington: Supreme Court of the United States, OCLC 2590161

- Suryanath U. Kamath (2001). A Concise History of Karnataka from pre-historic times to the present, Jupiter books, MCC, Bangalore (Reprinted 2002), OCLC: 7796041.