Immigration to the United States: Difference between revisions

studies ==> writers. refs in text seem to be writers' opinions. clarify unclear sentence |

|||

| Line 343: | Line 343: | ||

non-Hispanic white males, although less likely than non-Hispanic African American males.<ref name="sentencingproject"/> |

non-Hispanic white males, although less likely than non-Hispanic African American males.<ref name="sentencingproject"/> |

||

Other |

Other writers have suggested that immigrants are under-represented in criminal statistics{{Clarify|date=February 2012|reason=what does this mean? that they commit crimes and aren't caught? that they commit crimes but are not recorded as immigrants? that they don't commit as many crimes as others? The text in this paragraph implies that they commit less crime}}. In his 1999 book ''Crime and Immigrant Youth'', sociologist Tony Waters argued that immigrants themselves are less likely to be arrested and incarcerated; he also argued, however, that the children of some immigrant groups are more likely to be arrested and incarcerated. This is a by-product of the strains that emerge between immigrant parents living in [[Poverty in the United States|poor]], [[inner city]] neighborhoods. This occurs particularly in immigrant groups with many children as they begin to form particularly strong peer sub-cultures.[http://www.molokane.org/molokan/NEWS/Waters.html] A 1999 paper by John Hagan and Alberto Palloni estimated that the involvement in crime by Hispanic immigrants is less than that of other citizens.<ref name="jstor"/> A 2006 Op-Ed in ''[[The New York Times]]'' by [[Harvard University]] Professor in Sociology Robert J. Sampson says that immigration of Hispanics may in fact be associated with decreased crime.<ref name="Open Doors Don't Invite Criminals"/> |

||

A 2006 article by [[Migration Policy Institute]] cited data from the 2000 US Census as evidence for that foreign-born men had lower incarceration rates than native-born men.<ref name="migrationinformation44"/> |

A 2006 article by [[Migration Policy Institute]] cited data from the 2000 US Census as evidence for that foreign-born men had lower incarceration rates than native-born men.<ref name="migrationinformation44"/> |

||

Revision as of 17:41, 2 February 2012

Immigration to the United States is a complex demographic phenomenon that has been a major source of population growth and cultural change throughout much of the history of the United States. The economic, social, and political aspects of immigration have caused controversy regarding ethnicity, economic benefits, jobs for non-immigrants, settlement patterns, impact on upward social mobility, crime, and voting behavior. As of 2006, the United States accepts more legal immigrants as permanent residents than all other countries in the world combined.[1] Since the removal of ethnic quotas in immigration in 1965,[2] the number of first- generation immigrants living in the United States has quadrupled,[3] from 9.6 million in 1970 to about 38 million in 2007.[4] 1,046,539 persons were naturalized as U.S. citizens in 2008. The leading emigrating countries to the United States were Mexico, India, the Philippines, and China.[5] Nearly 14 million immigrants came to the United States from 2000 to 2010.[6]

The cheap airline travel post-1960 facilitated travel to the United States, but migration remains difficult, expensive, and dangerous for those who cross the United States–Mexico border illegally.[7] Family reunification accounts for approximately two-thirds of legal immigration to the US every year.[8] The number of foreign nationals who became legal permanent residents (LPRs) of the U.S. in 2009 as a result of family reunification (66%) outpaced those who became LPRs on the basis of employment skills (13%) and humanitarian reasons (17%).[9]

Recent debates on immigration have called for increasing enforcement of existing laws with regard to illegal immigration to the United States, building a barrier along some or all of the 2,000-mile (3,200 km) U.S.-Mexico border, or creating a new guest worker program. Through much of 2006, the country and Congress was immersed in a debate about these proposals. As of April 2010, few of these proposals had become law, though a partial border fence was approved and subsequently canceled.[10]

History

American immigration history can be viewed in four epochs: the colonial period, the mid-nineteenth century, the turn of the twentieth century, and post-1965. Each period brought distinct national groups, races and ethnicities to the United States. During the seventeenth century, approximately 175,000 Englishmen migrated to Colonial America.[11] Over half of all European immigrants to Colonial America during the 17th and 18th centuries arrived as indentured servants.[12] The mid-nineteenth century saw mainly an influx from northern Europe; the early twentieth-century mainly from Southern and Eastern Europe; post-1965 mostly from Latin America and Asia.

Historians estimate that fewer than one million immigrants—perhaps as few as 400,000—crossed the Atlantic during the 17th and 18th centuries.[13] The 1790 Act limited naturalization to "free white persons"; it was expanded to include blacks in the 1860s and Asians in the 1950s.[14] In the early years of the United States, immigration was fewer than 8,000 people a year,[15] including French refugees from the slave revolt in Haiti. After 1820, immigration gradually increased. From 1836 to 1914, over 30 million Europeans migrated to the United States.[16] The death rate on these transatlantic voyages was high, during which one in seven travelers died.[17] In 1875, the nation passed its first immigration law.[18]

The peak year of European immigration was in 1907, when 1,285,349 persons entered the country.[19] By 1910, 13.5 million immigrants were living in the United States.[20] In 1921, the Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act, followed by the Immigration Act of 1924. The 1924 Act was aimed at further restricting the Southern and Eastern Europeans, especially Jews, Italians, and Slavs, who had begun to enter the country in large numbers beginning in the 1890s.[21] Most of the European refugees fleeing the Nazis and World War II were barred from coming to the United States.[22]

Immigration patterns of the 1930s were dominated by the Great Depression, which hit the U.S. hard and lasted over ten years there. In the final prosperous year, 1929, there were 279,678 immigrants recorded,[23] but in 1933, only 23,068 came to the U.S.[13] In the early 1930s, more people emigrated from the United States than immigrated to it.[24] The U.S. government sponsored a Mexican Repatriation program which was intended to encourage people to voluntarily move to Mexico, but thousands were deported against their will.[25] Altogether about 400,000 Mexicans were repatriated.[26] In the post-war era, the Justice Department launched Operation Wetback, under which 1,075,168 Mexicans were deported in 1954.[27]

"First, our cities will not be flooded with a million immigrants annually. Under the proposed bill, the present level of immigration remains substantially the same.... Secondly, the ethnic mix of this country will not be upset.... Contrary to the charges in some quarters, [the bill] will not inundate America with immigrants from any one country or area, or the most populated and deprived nations of Africa and Asia.... In the final analysis, the ethnic pattern of immigration under the proposed measure is not expected to change as sharply as the critics seem to think."

— -Ted Kennedy, chief Senate sponsor of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.[28]

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, also known as the Hart-Cellar Act, abolished the system of national-origin quotas. By equalizing immigration policies, the act resulted in new immigration from non-European nations, which changed the ethnic make-up of the United States.[29] While European immigrants accounted for nearly 60% of the total foreign population in 1970, they accounted for only 15% in 2000.[30] Immigration doubled between 1965 and 1970, and again between 1970 and 1990.[31] In 1990, George H. W. Bush signed the Immigration Act of 1990,[32] which increased legal immigration to the United States by 40%.[33] Appointed by Bill Clinton,[34] the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform recommended reducing legal immigration from about 800,000 people per year to approximately 550,000.[35] While an influx of new residents from different cultures presents some challenges, "the United States has always been energized by its immigrant populations," said President Bill Clinton in 1998. "America has constantly drawn strength and spirit from wave after wave of immigrants [...] They have proved to be the most restless, the most adventurous, the most innovative, the most industrious of people."[36]

Nearly eight million immigrants came to the United States from 2000 to 2005, more than in any other five-year period in the nation's history.[37] Almost half entered illegally.[38] Since 1986, Congress has passed seven amnesties for illegal immigrants.[39] In 1986, Ronald Reagan signed immigration reform that gave amnesty to 3 million illegal immigrants in the country.[40] Hispanic immigrants were among the first victims of the late-2000s recession,[41] but since the recession's end in June 2009, immigrants posted a net gain of 656,000 jobs.[42] 1.1 million immigrants were granted legal residence in 2009.[43]

- Persons Obtaining Legal Permanent Resident Status Fiscal Years

| Year | Year | Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 249,187 | 1987 | 601,516 | 2008 | 1,107,126 |

| 1967 | 361,972 | 1997 | 797,847 | 2009 | 1,130,818 |

| 1977 | 462,315 | 2007 | 1,052,415 | 2010 | 1,042,625 |

Source: US Department of Homeland Security, Persons Obtaining Legal Permanent Resident Status: Fiscal Years 1820 to 2010[44]

Contemporary immigration

Until the 1930s, the gender imbalance among legal immigrants was quite sharp, with most legal immigrants being male. As of the 1990s, however, women accounted for just over half of all legal immigrants, shifting away from the male-dominated immigration of the past.[45] Contemporary immigrants tend to be younger than the native population of the United States, with people between the ages 15 and 34 substantially overrepresented.[46] Immigrants are also more likely to be married and less likely to be divorced than native-born Americans of the same age.[47]

Immigrants are likely to move to and live in areas populated by people with similar backgrounds. This phenomenon has held true throughout the history of immigration to the United States.[48] Seven out of ten immigrants surveyed by Public Agenda in 2009 said they intended to make the U.S. their permanent home, and 71% said if they could do it over again they would still come to the US. In the same study, 76% of immigrants say the government has become stricter on enforcing immigration laws since 9/11, and 24% report that they personally have experienced some or a great deal of discrimination.[49]

Public attitudes about immigration in the U.S. have been heavily influenced by the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks. After the attacks, 52% of Americans believed that immigration was a good thing overall for the U.S., down from 62% the year before, according to a 2009 Gallup poll.[50] Half of Americans say tighter controls on immigration would do "a great deal" to enhance U.S. national security, according to a 2008 Public Agenda survey.[51] Harvard political scientist and historian Samuel P. Huntington argued that a potential future consequence of continuing massive immigration from Latin America, especially Mexico, may lead to the bifurcation of the United States in Who Are We? The Challenges to America's National Identity.

More than 80 cities in the United States,[52] including Washington D.C., New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, San Francisco, San Diego, San Jose, Salt Lake City, Phoenix, Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, Detroit, Jersey City, Minneapolis, Miami, Denver, Baltimore, Seattle, Portland, Oregon and Portland, Maine, have sanctuary policies, which vary locally.[53]

- Inflow of New Legal Permanent Residents, Top Five Sending Countries, 2010

| Country | 2010 | Region | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico | 139,120 | Americas | 423,784 |

| China | 70,863 | Asia | 422,058 |

| India | 69,162 | Africa | 101,351 |

| Philippines | 58,173 | Europe | 88,730 |

| Dominican Republic | 53,870 | All Immigrants | 1,042,625 |

Source: US Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics[54]

Demography

The United States admitted more legal immigrants from 1991 to 2000, between ten to eleven million, than in any previous decade. In the most recent decade, the ten million legal immigrants that settled in the U.S. represent an annual growth of only about 0.3% as the U.S. population grew from 249 million to 281 million. By comparison, the highest previous decade was the 1900s, when 8.8 million people arrived, increasing the total U.S. population by one percent every year. Specifically, "nearly 15% of Americans were foreign-born in 1910, while in 1999, only about 10% were foreign-born." [55]

By 1970 immigrants accounted for 4.7 percent of the US population and rising to 6.2 percent in 1980, with an estimated 12.5 percent to this date.[56] As of 2010, a quarter of the residents of the United States under 18 are immigrants or are immigrants' children.[57] Eight percent of all babies born in the U.S. in 2008 belonged to illegal immigrant parents, according to a recent analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data by the Pew Hispanic Center.[58]

Legal immigration to the U.S. increased from 250,000 in the 1930s, to 2.5 million in the 1950s, to 4.5 million in the 1970s, and to 7.3 million in the 1980s, before resting at about 10 million in the 1990s.[59] Since 2000, legal immigrants to the United States number approximately 1,000,000 per year, of whom about 600,000 are Change of Status who already are in the U.S. Legal immigrants to the United States now are at their highest level ever, at just over 37,000,000 legal immigrants. Illegal immigration may be as high as 1,500,000 per year with a net of at least 700,000 illegal immigrants arriving every year.[60][61] Immigration led to a 57.4% increase in foreign born population from 1990 to 2000.[62]

While immigration has increased drastically over the last century, the foreign born share of the population was still higher in 1900 (about 20%) than it is today (about 10%). A number of factors may be attributed to the decrease in the representation of foreign born residents in the United States. Most significant has been the change in the composition of immigrants; prior to 1890, 82% of immigrants came from North and Western Europe. From 1891 to 1920, that number dropped to 25%, with a rise in immigrants from East, Central, and South Europe, summing up to 64%. Animosity towards these different and foreign immigrants rose in the United States, resulting in much legislation to limit immigration.

Contemporary immigrants settle predominantly in seven states, California, New York, Florida, Texas, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Illinois, comprising about 44% of the U.S. population as a whole. The combined total immigrant population of these seven states is 70% of the total foreign-born population as of 2000. If current birth rate and immigration rates were to remain unchanged for another 70 to 80 years, the U.S. population would double to nearly 600 million.[63]

The top twelve emigrant countries in 2006 were Mexico (173,753), People's Republic of China (87,345), Philippines (74,607), India (61,369), Cuba (45,614), Colombia (43,151), Dominican Republic (38,069), El Salvador (31,783), Vietnam (30,695), Jamaica (24,976), South Korea (24,386), Guatemala (24,146). Other countries comprise an additional 606,370.[54] In fiscal year 2006, 202 refugees from Iraq were allowed to resettle in the United States.[64][65]

In 1900, when the U.S. population was 76 million, there were an estimated 500,000 Hispanics.[66] The Census Bureau projects that by 2050, one-quarter of the population will be of Hispanic descent.[67] This demographic shift is largely fueled by immigration from Latin America.[68][69]

Origin

- Top Ten Foreign Countries - Foreign Born Population Among U.S. Immigrants

| Country | per year | 2000 | 2004 | 2010 | 2010, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico | 175,900 | 7,841,000 | 8,544,600 | 9,600,000 | 23.7% |

| China | 50,900 | 1,391,000 | 1,594,600 | 1,900,000 | 4.7% |

| Philippines | 47,800 | 1,222,000 | 1,413,200 | 1,700,000 | 4.2% |

| India | 59,300 | 1,007,000 | 1,244,200 | 1,610,000 | 4.0% |

| Vietnam | 33,700 | 863,000 | 997,800 | 1,200,000 | 3.0% |

| Cuba | 14,800 | 952,000 | 1,011,200 | 1,100,000 | 2.7% |

| El Salvador | 33,500 | 765,000 | 899,000 | 1,100,000 | 2.7% |

| Dominican Republic | 24,900 | 692,000 | 791,600 | 941,000 | 2.3% |

| Canada | 24,200 | 678,000 | 774,800 | 920,000 | 2.3% |

| Korea | 17,900 | 701,000 | 772,600 | 880,000 | 2.2% |

| Total Pop. Top 10 | 498,900 | 16,112,000 | 18,747,600 | 21,741,000 | 53.7% |

| Total Foreign Born | 940,000 | 31,100,000 | 34,860,000 | 40,500,000 | 100% |

Immigration by state

- Percentage change in Foreign Born Population 1990 to 2000

| North Carolina | 273.7% | South Carolina | 132.1% | Mississippi | 95.8% | Wisconsin | 59.4% | Vermont | 32.5% |

| Georgia | 233.4% | Minnesota | 130.4% | Washington | 90.7% | New Jersey | 52.7% | Connecticut | 32.4% |

| Nevada | 202.0% | Idaho | 121.7% | Texas | 90.2% | Alaska | 49.8% | New Hampshire | 31.5% |

| Arkansas | 196.3% | Kansas | 114.4% | New Mexico | 85.8% | Michigan | 47.3% | Ohio | 30.7% |

| Utah | 170.8% | Iowa | 110.3% | Virginia | 82.9% | Wyoming | 46.5% | Hawaii | 30.4% |

| Tennessee | 169.0% | Oregon | 108.0% | Missouri | 80.8% | Pennsylvania | 37.6% | North Dakota | 29.0% |

| Nebraska | 164.7% | Alabama | 101.6% | South Dakota | 74.6% | California | 37.2% | Rhode Island | 25.4% |

| Colorado | 159.7% | Delaware | 101.6% | Maryland | 65.3% | New York | 35.6% | West Virginia | 23.4% |

| Arizona | 135.9% | Oklahoma | 101.2% | Florida | 60.6% | Massachusetts | 34.7% | Montana | 19.0% |

| Kentucky | 135.3% | Indiana | 97.9% | Illinois | 60.6% | Louisiana | 32.6% | Maine | 1.1% |

Source: U.S. Census 1990 and 2000

Effects of immigration

Demographics

The Census Bureau estimates the US population will grow from 281 million in 2000 to 397 million in 2050 with immigration, but only to 328 million with no immigration.[70] A new report from the Pew Research Center projects that by 2050, non-Hispanic whites will account for 47% of the population, down from the 2005 figure of 67%.[71] Non-Hispanic whites made up 85% of the population in 1960.[72] It also foresees the Hispanic population rising from 14% in 2005 to 29% by 2050.[73] The Asian population is expected to more than triple by 2050. Overall, the population of the United States is due to rise from 296 million in 2005 to 438 million in 2050, with 82% of the increase from immigrants.[74]

In 35 of the country's 50 largest cities, non-Hispanic whites were at the last census or are predicted to be in the minority.[75] In California, non-Hispanic whites slipped from 80% of the state's population in 1970 to 42.3% in 2008.[76][77]

Immigrant segregation declined in the first half of the century, but has been rising over the past few decades. This has caused questioning of the correctness of describing the United States as a melting pot. One explanation is that groups with lower socioeconomic status concentrate in more densely populated area that have access to public transit while groups with higher socioeconomic status move to suburban areas. Another is that some recent immigrant groups are more culturally and linguistically different than earlier group and prefer to live together due to factors such as communication costs.[78] Another explanation for increased segregation is white flight.[79]

- Place of birth for the foreign-born population in the United States

| Top ten countries | 2010 | 2000 | 1990 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico | 11,711,103 | 9,177,487 | 4,298,014 |

| China | 2,166,526 | 1,518,652 | 921,070 |

| India | 1,780,322 | 1,022,552 | 450,406 |

| Philippines | 1,777,588 | 1,369,070 | 912,674 |

| Vietnam | 1,240,542 | 988,174 | 543,262 |

| El Salvador | 1,214,049 | 817,336 | 465,433 |

| Cuba | 1,104,679 | 872,716 | 736,971 |

| South Korea | 1,100,422 | 864,125 | 568,397 |

| Dominican Republic | 879,187 | 687,677 | 347,858 |

| Guatemala | 830,824 | 480,665 | 225,739 |

| All of Latin America | 21,224,087 | 16,086,974 | 8,407,837 |

| All Immigrants | 39,955,854 | 31,107,889 | 19,767,316 |

Source: 1990 and 2000 decennial Census and 2010 American Community Survey

Economic

In a late 1980s study, economists overwhelmingly viewed immigration, including illegal immigration, as a positive for the economy.[80] According to James Smith, a senior economist at Santa Monica-based RAND Corporation and lead author of the United States National Research Council's study "The New Americans: Economic, Demographic, and Fiscal Effects of Immigration", immigrants contribute as much as $10 billion to the U.S. economy each year.[81] The NRC report found that although immigrants, especially those from Latin America, caused a net loss in terms of taxes paid versus social services received, immigration can provide an overall gain to the domestic economy due to an increase in pay for higher-skilled workers, lower prices for goods and services produced by immigrant labor, and more efficiency and lower wages for some owners of capital. The report also notes that although immigrant workers compete with domestic workers for low-skilled jobs, some immigrants specialize in activities that otherwise would not exist in an area, and thus can be beneficial for all domestic residents.[82] A non-partisan report in 2007 from the Congressional Budget Office concluded that most estimates show that illegal immigrants impose a net cost to state and local governments, but “that no agreement exists as to the size of, or even the best way of measuring, the cost on a national level.”[83] Estimates of the net national cost that illegal immigrants impose on the United States vary greatly, with the Urban Institute saying it was $1.9 billion in 1992, and a Rice University professor putting it at $19.3 billion in 1993.[84]

About twenty-one million immigrants, or about fifteen percent of the labor force, hold jobs in the United States; however, the number of unemployed is only seven million, meaning that immigrant workers are not taking jobs from domestic workers, but rather are doing jobs that would not have existed had the immigrant workers not been in the United States.[85] U.S. Census Bureau's Survey of Business Owners: Hispanic-Owned Firms: 2002 indicated that the number of Hispanic-owned businesses in the United States grew to nearly 1.6 million in 2002. Those businesses generated about $222 billion in gross revenue.[86] The report notes that the burden of poor immigrants is not born equally among states, and is most heavy in California.[87] Another claim supporting expanding immigration levels is that immigrants mostly do jobs Americans do not want. A 2006 Pew Hispanic Center report added evidence to support this claim, when they found that increasing immigration levels have not hurt employment prospects for American workers.[88]

In 2009, a study by the Cato Institute, a free market think tank, found that legalization of low-skilled illegal resident workers in the US would result in a net increase in US GDP of $180 billion over ten years.[89] The Cato Institute study chose to completely ignore the impact on per capita income for most Americans. Jason Riley notes that because of progressive income taxation, in which the top 1% of earners pay 37% of federal income taxes (even though they actually pay a lower tax percentage based on their income), 60% of Americans collect more in government services than they pay in, which also reflects on immigrants.[90] In any event, the typical immigrant and his children will pay a net $80,000 more in their lifetime than they collect in government services according to the NAS.[91] Legal immigration policy is set to maximize net taxation. Illegal immigrants even after an amnesty tend to be recipients of more services than they pay in taxes. In 2010, an econometrics study by a Rutgers economist found that immigration helped increase bilateral trade when the incoming people were connected via networks to their country of origin, particularly boosting trade of final goods as opposed to intermediate goods, but that the trade benefit weakened when the immigrants became assimilated into American culture.[92]

The Kauffman Foundation’s index of entrepreneurial activity is nearly 40% higher for immigrants than for natives.[93] Immigrants were involved in the founding of many prominent American high-tech companies, such as Google, Yahoo, Sun Microsystems, and eBay.[94]

On the poor end of the spectrum, the "New Americans" report found that low-wage immigration does not, on aggregate, lower the wages of most domestic workers. The report also addresses the question of if immigration affects black Americans differently from the population in general: "While some have suspected that blacks suffer disproportionately from the inflow of low-skilled immigrants, none of the available evidence suggests that they have been particularly hard-hit on a national level. Some have lost their jobs, especially in places where immigrants are concentrated. But the majority of blacks live elsewhere, and their economic fortunes are tied to other factors."[96]

The analysis shows that 31% of adult immigrants have not completed high school. A third lack health insurance.[37] Robert Samuelson points out that poor immigrants strain public services such as local schools and health care. He points out that "from 2000 to 2006, 41 percent of the increase in people without health insurance occurred among Hispanics."[97] According to the immigration reduction advocacy group Center for Immigration Studies, 25.8% of Mexican immigrants live in poverty, which is more than double the rate for natives in 1999.[98] In another report, The Heritage Foundation notes that from 1990 to 2006, the number of poor Hispanics increased by 3.2 million, from 6 million to 9.2 million.[99]

Hispanic immigrants in the United States were hit hard by the subprime mortgage crisis. There was a disproportionate level of foreclosures in some immigrant neighborhoods.[100] The banking industry provided home loans to undocumented immigrants, viewing it as an untapped resource for growing their own revenue stream.[101] In October 2008, KFYI reported that according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, five million illegal immigrants held fraudulent home mortgages.[102] The story was later pulled from their website and replaced with a correction.[103] The Phoenix Business Journal cited a HUD spokesman saying that there was no basis to news reports that more than five million bad mortgages were held by illegal immigrants, and that the agency had no data showing the number of illegal immigrants holding foreclosed or bad mortgages.[104] Since USCIS is 99% funded by immigration application fees,many USCIS jobs have been created by immigration to US, such as immigration interview officials,finger print processor, etc.

An article by American Enterprise Institute researcher Jason Richwine states that while earlier European immigrants were often poor when they arrived, by the third generation they had economically assimilated to be indistinguishable from the general population. However, for the Hispanics immigrants the process stalls at the second generation and the third generation continues to be substantially poorer than whites.[105] Despite apparent disparities between different communities,[106] Asians, a significant number of whom arrived to the United States after 1965,[107] had the highest median income per household among all race groups as of 2008.[108]

The passing of tough immigration laws in several states from around 2009 provides a view of actual outcomes, rather than theoretical predictions. The state of Georgia passed immigration law HB 87 in 2011[109]; this led to 50% of its agricultural produce being left to rot in the fields, at a cost to the state of more than $400m. Overall losses caused by the act were $1bn; it was estimated that the figure would become over $20bn if all the estimated 325,000 undocumented workers left Georgia. The cost to Alabama of its crackdown in June 2011 has been estimated at almost $11bn, with up to 80,000 unauthorised immigrant workers leaving the state[110].

Social

Benjamin Franklin opposed German immigration, stating that they would not assimilate into the culture.[111] Irish immigration was opposed in the 1850s by the nativist Know Nothing movement, originating in New York in 1843. It was engendered by popular fears that the country was being overwhelmed by Irish Catholic immigrants. In 1891, a lynch mob stormed a local jail and hanged several Italians following the acquittal of several Sicilian immigrants alleged to be involved in the murder of New Orleans police chief David Hennessy. The Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act in 1921, followed by the Immigration Act of 1924. The Immigration Act of 1924 was aimed at limiting immigration overall, and making sure that the nationalities of new arrivals matched the overall national profile.

After the September 11 attacks, many Americans entertained doubts and suspicions about people apparently of Middle-Eastern origins.[citation needed] NPR in 2010 fired a prominent black commentator, Juan Williams, when he talked publicly about his fears on seeing people dressed like Muslims on airplanes.[112]

Racist thinking among and between minority groups does occur;[113][114] examples of this are conflicts between blacks and Korean immigrants, notably in the 1992 Los Angeles Riots, and between African Americans and non-white Latino immigrants.[115][116] There has been a long running racial tension between African American and Mexican prison gangs, as well as significant riots in California prisons where they have targeted each other, for ethnic reasons.[117][118] There have been reports of racially motivated attacks against African Americans who have moved into neighborhoods occupied mostly by people of Mexican origin, and vice versa.[119][120] There has also been an increase in violence between non-Hispanic Anglo Americans and Latino immigrants, and between African immigrants and African Americans.[121]

A 2007 study on assimilation found that Mexican immigrants are less fluent in English than both non-Mexican Hispanic immigrants and other immigrants. While English fluency increases with time stayed in the United States, although further improvements after the first decade are limited, Mexicans never catch up with non-Mexican Hispanic who never catch up with non-Hispanics. The study also writes that "Even among immigrants who came to the United States before they were five years old and whose entire schooling was in the United States, those Mexican born have average education levels of 11.7 years, whereas those from other countries have average levels of education of 14.1 years." Unlike other immigrants, Mexicans have a tendency to live in communities with many other Mexicans which decreases incentives for assimilation. Correcting for this removes about half the fluency difference between Mexicans and other immigrants.[122]

Religious diversity

Immigration from South Asia and elsewhere has contributed to enlarging the religious composition of the United States. Islam in the United States is growing thanks in part to immigration. Hinduism in the United States, Buddhism in the United States, and Sikhism in the United States are other examples.[123]

Political

Immigrants differ on their political views; however, the Democratic Party is considered to be in a far stronger position among immigrants overall.[124][125] Research shows that religious affiliation can also significantly impact both their social values and voting patterns of immigrants, as well as the broader American population. Hispanic evangelicals, for example, are more strongly conservative than non-Hispanic evangelicals.[126] This trend is often similar for Hispanics or others strongly identifying with the Catholic Church, a religion that strongly opposes abortion and gay marriage.

The key interests groups that lobby on immigration are religious, ethnic and business groups, together with some liberals and some conservative public policy organizations. Both the pro- and anti- groups affect policy.[127][dead link]

Studies have suggested that some special interest group lobby for less immigration for their own group and more immigration for other groups since they see effects of immigration, such as increased labor competition, as detrimental when affecting their own group but beneficial when affecting other groups.[citation needed]

A 2007 paper found that both pro- and anti-immigration special interest groups play a role in migration policy. "Barriers to migration are lower in sectors in which business lobbies incur larger lobbying expenditures and higher in sectors where labor unions are more important."[128] A 2011 study examining the voting of US representatives on migration policy suggests that "that representatives from more skilled labor abundant districts are more likely to support an open immigration policy towards the unskilled, whereas the opposite is true for representatives from more unskilled labor abundant districts."[129]

After the 2010 election, Gary Segura of Latino Decisions stated that Hispanic voters influenced the outcome and "may have saved the Senate for Democrats".[130] Several ethnic lobbies support immigration reforms that would allow illegal immigrants that have succeeded in entering to gain citizenship. They may also lobby for special arrangements for their own group. The Chairman for the Irish Lobby for Immigration Reform has stated that "the Irish Lobby will push for any special arrangement it can get — 'as will every other ethnic group in the country.'"[131][132] The irrendentist and ethnic separatist movements for Reconquista and Aztlán see immigration from Mexico as strengthening their cause.[133][134]

The book Ethnic Lobbies and US Foreign Policy (2009) states that several ethnic special interest groups are involved in pro-immigration lobbying. Ethnic lobbies also influence foreign policy. The authors write that "Increasingly, ethnic tensions surface in electoral races, with House, Senate, and gubernatorial contests serving as proxy battlegrounds for antagonistic ethnoracial groups and communities. In addition, ethnic politics affect party politics as well, as groups compete for relative political power within a party". However, the authors argue that currently ethnic interest groups, in general, do not have too much power in foreign policy and can balance other special interest groups.[135]

Health

The issue of the health of immigrants and the associated cost to the public has been largely discussed. The non-emergency use of emergency rooms ostensibly indicates an incapacity to pay, yet some studies allege disproportionately lower access to unpaid health care by immigrants.[136] For this and other reasons, there have been various disputes about how much immigration is costing the United States public health system.[137] University of Maryland economist and Cato Institute scholar Julian Lincoln Simon concluded in 1995 that while immigrants probably pay more into the health system than they take out, this is not the case for elderly immigrants and refugees, who are more dependent on public services for survival.[138]

Immigration from areas of high incidences of disease is thought to have fueled the resurgence of tuberculosis (TB), chagas, and hepatitis in areas of low incidence.[139] According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), TB cases among foreign-born individuals remain disproportionately high, at nearly nine times the rate of U.S.-born persons.[140][141] To reduce the risk of diseases in low-incidence areas, the main countermeasure has been the screening of immigrants on arrival.[142] HIV/AIDS entered the United States in around 1969, likely through a single infected immigrant from Haiti.[143][144] Conversely, many new HIV infections in Mexico can be traced back to the United States.[145] People infected with HIV were banned from entering the United States in 1987 by executive order, but the 1993 statute supporting the ban was lifted in 2009. The executive branch is expected to administratively remove HIV from the list of infectious diseases barring immigration, but immigrants generally would need to show that they would not be a burden on public welfare.[146] Researchers have also found what is known as the "healthy immigrant effect", in which immigrants in general tend to be healthier than individuals born in the U.S.[147][148]

Crime

Empirical studies on links between immigration and crime are mixed.

According to Bureau of Justice Statistics as of 2001, 4% of Hispanic males in their twenties and thirties were in prison or jail, compared to 1.8% of non-Hispanic white males. Hispanic men are almost four times as likely to go to prison at some point in their lives than non-Hispanic white males, although less likely than non-Hispanic African American males.[149]

Other writers have suggested that immigrants are under-represented in criminal statistics[clarification needed]. In his 1999 book Crime and Immigrant Youth, sociologist Tony Waters argued that immigrants themselves are less likely to be arrested and incarcerated; he also argued, however, that the children of some immigrant groups are more likely to be arrested and incarcerated. This is a by-product of the strains that emerge between immigrant parents living in poor, inner city neighborhoods. This occurs particularly in immigrant groups with many children as they begin to form particularly strong peer sub-cultures.[11] A 1999 paper by John Hagan and Alberto Palloni estimated that the involvement in crime by Hispanic immigrants is less than that of other citizens.[150] A 2006 Op-Ed in The New York Times by Harvard University Professor in Sociology Robert J. Sampson says that immigration of Hispanics may in fact be associated with decreased crime.[151]

A 2006 article by Migration Policy Institute cited data from the 2000 US Census as evidence for that foreign-born men had lower incarceration rates than native-born men.[152]

According to a 2007 report by the Immigration Policy Center, the American Immigration Law Foundation, citing data from the 2000 US Census, Native-born American men between 18-39 are five times more likely to be incarcerated than immigrants in the same demographic.[153]

A 2008 study by the Public Policy Institute of California, found that, "...on average, between 2000 and 2005, cities that had a higher share of recent immigrants (those arriving between 2000 and 2005) saw their crime rates fall further than cities with a lower share" but adds, "As with most studies, we do not have ideal data. This lack of data restricts the questions we will be able to answer. In particular, we cannot focus on the undocumented population explicitly".[154] In a study released by the same Institute, immigrants were ten times less likely to be incarcerated than native born Americans.[155]

Explanations for the lower incarceration rates of immigrants include:

- Legal immigrants are screened for criminality prior to entry.

- Legal and illegal immigrants who commit serious crimes are being deported and therefore are unable to commit more crimes (unlike their US couterparts who remain in the US). They are unlikely to become "career criminals" moving in and out of the prison system. In the last 10 years, 816,000 criminal aliens have been removed from the United States. This does not include immigrants whose only offense was living or working illegally in the United States.[156]

- Immigrants understand the severe consequences of being arrested given their legal status (i.e. threat of deportation).

Heather MacDonald at the Manhattan Institute in a 2004 article argued that sanctuary policies has caused large problems with crime by illegal aliens since the police cannot report them for deportation before a felony or a series of misdemeanors takes place. In Los Angeles, 95 percent of all outstanding warrants for homicide are for illegal aliens. Up to two-thirds of all fugitive felony warrants (17,000) are for illegal aliens. 60 percent of the 20,000-strong 18th Street Gang in southern California were illegal aliens in a 1995 report.[157]

The Center for Immigration Studies in a 2009 report argued that "New government data indicate that immigrants have high rates of criminality, while older academic research found low rates. The overall picture of immigrants and crime remains confused due to a lack of good data and contrary information." It also criticized the reports by the Public Policy Institute of California and Immigration Policy Center for using data from the 2000 Census according to which 4% of prisoners were immigrants. Non-citizens often have a strong incentive to deny this in order to prevent deportation and there are also other problems. Better methods have found 20-22% immigrants. It also criticized studies looking at percentages of immigrants in a city and crime for only looking at overall crime and not immigrant crime. A 2009 analysis by the Department of Homeland Security found that crime rates were higher in metropolitan areas that received large numbers of legal immigrants, contradicting several older cross-city comparisons.[156]

Environment

Some commentators have suggested that increased immigration has a negative effect on the environment, especially as the level of economic development of the United States (and by extension, its energy, water[158] and other needs that underpin its prosperity) means that the impact of a larger population is greater than what would be experienced in other countries.[159]

Perceived heavy immigration, especially in the southwest, has led to some fears about population pressures on the water supply in some areas. California continues to grow by more than a half-million a year and is expected to reach 48 million in 2030.[160] According to the California Department of Water Resources, if more supplies are not found by 2020, residents will face a water shortfall nearly as great as the amount consumed today.[161] Los Angeles is a coastal desert able to support at most one million people on its own water.[162] California is considering using desalination to solve this problem.[163]

Education

Forty percent of Ph.D. scientists working in the United States were born abroad.[93]

A study on public schools in California found that white enrollment declined in response to increases in the number of Spanish-speaking Limited English Proficient and Hispanic students. This white flight was greater for schools with relatively larger proportions of Spanish-speaking Limited English Proficient.[79]

Effects on African Americans

An econometic study bu George J. Borjas suggested that immigration had detrimental effects on African-American employment in terms of lower wages and numbers employed. It reported that a 10% increase in the supply of workers reduced the black wage of that group by 2.5%, lowered the employment rate by 5.9% and increased the Black incarceration rate by 1.3%.[164]

Public opinion

The ambivalent feeling of Americans toward immigrants is shown by a positive attitude toward groups that have been visible for a century or more, and much more negative attitude toward recent arrivals. For example a 1982 national poll by the Roper Center at the University of Connecticut showed respondents a card listing a number of groups and asked, "Thinking both of what they have contributed to this country and have gotten from this country, for each one tell me whether you think, on balance, they've been a good or a bad thing for this country," which produced the results shown in the table. "By high margins, Americans are telling pollsters it was a very good thing that Poles, Italians, and Jews emigrated to America. Once again, it's the newcomers who are viewed with suspicion. This time, it's the Mexicans, the Filipinos, and the people from the Caribbean who make Americans nervous." [165][166]

In a 2002 study, which took place soon after the September 11 attacks, 55% of Americans favored decreasing legal immigration, 27% favored keeping it at the same level, and 15% favored increasing it.[167]

In 2006, the immigration-reduction advocacy think tank the Center for Immigration Studies released a poll that found that 68% of Americans think U.S. immigration levels are too high, and just 2% said they are too low. They also found that 70% said they are less likely to vote for candidates that favor increasing legal immigration.[168] In 2004, 55% of Americans believed legal immigration should remain at the current level or increased and 41% said it should be decreased.[169] The less contact a native-born American has with immigrants, the more likely one would have a negative view of immigrants.[169]

One of the most important factors regarding public opinion about immigration is the level of unemployment; anti-immigrant sentiment is where unemployment is highest, and vice-versa.[170]

Surveys indicate that the U.S. public consistently makes a sharp distinction between legal and illegal immigrants, and generally views those perceived as “playing by the rules” with more sympathy than immigrants that have entered the country illegally.[171]

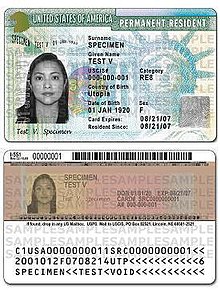

Legal issues

Laws concerning immigration and naturalization

Laws concerning immigration and naturalization include:

- the 1990 Immigration Act (IMMACT), which limits the annual number of immigrants to 700,000. It emphasizes that family reunification is the main immigration criterion, in addition to employment-related immigration.

- the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA)

- the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA)

AEDPA and IIRARA exemplify many categories of criminal activity for which immigrants, including green card holders, can be deported and have imposed mandatory detention for certain types of cases.

Asylum for refugees

In contrast to economic migrants, who generally do not gain legal admission, refugees, as defined by international law, can gain legal status through a process of seeking and receiving asylum, either by being designated a refugee while abroad, or by physically entering the United States and requesting asylum status thereafter. A specified number of legally defined refugees, who either apply for asylum overseas or after arriving in the U.S., are admitted annually.[quantify] Refugees compose about one-tenth of the total annual immigration to the United States, though some large refugee populations are very prominent.[citation needed] In the years 2005 through 2007, the number of asylum seekers accepted into the U.S. was about 40,000 per year. This compared with about 30,000 per year in the UK and 25,000 in Canada.[citation needed] Japan accepted just 41 refugees for resettlement in 2007.[172]

Since 2000 the main refugee-sending regions have been Somalia, Liberia, Sudan, and Ethiopia.[173] The ceiling for refugee resettlement for fiscal year 2008 was 80,000 refugees.[174] The United States expected to admit a minimum of 17,000 Iraqi refugees during fiscal year 2009.[175]

In 2009, President Bush set the admissions ceiling at 80,000 refugees.[176] In FY 2008, the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) was appropriated over $655 million for the longer-term services provided to refugees after their arrival in the US.[177] The Obama administration has kept to about the same level.[178]

Miscellaneous documented immigration

In removal proceedings in front of an immigration judge, cancellation of removal is a form of relief that is available for certain long-time residents of the United States.[179] It allows a person being faced with the threat of removal to obtain permanent residence if that person has been physically present in the U.S. for at least ten years, has had good moral character during that period, has not been convicted of certain crimes, and can show that removal would result in exceptional and extremely unusual hardship to his or her U.S. citizen or permanent resident spouse, children, or parent. This form of relief is only available when a person is served with a Notice to Appear to appear in the proceedings in the court.[180][181]

Members of Congress may submit private bills granting residency to specific named individuals. A special committee vets the requests, which require extensive documentation. The Central Intelligence Agency has the statutory authority to admit up to one hundred people a year outside of normal immigration procedures, and to provide for their settlement and support. The program is called "PL110", named after the legislation that created the agency, Public Law 110, the Central Intelligence Agency Act.

Immigration in popular culture

The history of immigration to the United States is the history of the country itself, and the journey from beyond the sea is an element found in American folklore, appearing over and over again in everything from The Godfather to Gangs of New York to "The Song of Myself" to Neil Diamond's "America" to the animated feature An American Tail.[183]

From the 1880s to the 1910s, vaudeville dominated the popular image of immigrants, with very popular caricature portrayals of ethnic groups. The specific features of these caricatures became widely accepted as accurate portrayals.[184]

In The Melting Pot (1908), playwright Israel Zangwill (1864–1926) explored issues that dominated Progressive Era debates about immigration policies. Zangwill's theme of the positive benefits of the American melting pot resonated widely in popular culture and literary and academic circles in the 20th century; his cultural symbolism – in which he situated immigration issues – likewise informed American cultural imagining of immigrants for decades, as exemplified by Hollywood films.[185][186] The popular culture's image of ethnic celebrities often includes stereotypes about immigrant groups. For example, Frank Sinatra's public image as a superstar contained important elements of the American Dream while simultaneously incorporating stereotypes about Italian Americans that were based in nativist and Progressive responses to immigration.[187]

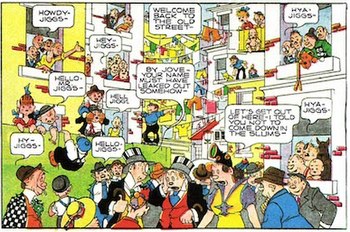

The process of assimilation was often a theme of popular culture. For example, "lace-curtain Irish" referred to middle-class Irish Americans desiring assimilation into mainstream society in counterpoint to an older, more raffish "shanty Irish". The occasional malapropisms and left-footed social blunders of these upward mobiles were gleefully lampooned in vaudeville, popular song, and the comic strips of the day such as "Bringing Up Father", starring Maggie and Jiggs, which ran in daily newspapers for 87 years (1913 to 2000).[188][189] In recent years the popular culture has paid special attention to Mexican immigration[190] and the 2004 motion picture Spanglish tells of a friendship of a Mexican housemaid (Paz Vega) and her boss played by Adam Sandler.

Immigration in literature

Novelists and writers have captured much of the color and challenge in their immigrant lives through their writings.[191]

Regarding Irish women in the 19th century, there were numerous novels and short stories by Harvey O'Higgins, Peter McCorry, Bernard O'Reilly and Sarah Orne Jewett that emphasize emancipation from Old World controls, new opportunities and expansiveness of the immigrant experience.[192]

On the other hand Hladnik studies three popular novels of the late 19th century that warned Slovenes not to immigrate to the dangerous new world of the United States.[193]

Jewish American writer Anzia Yezierska wrote her novel Bread Givers (1925) to explore such themes as Russian-Jewish immigration in the early 20th century, the tension between Old and New World Yiddish culture, and women's experience of immigration. A well established author Yezierska focused on the Jewish struggle to escape the ghetto and enter middle- and upper-class America. In the novel, the heroine, Sara Smolinsky, escape from New York City's "down-town ghetto" by breaking tradition. She quits her job at the family store and soon becomes engaged to a rich real-estate magnate. She graduates college and takes a high-prestige job teaching public school. Finally Sara restores her broken links to family and religion.[194]

The Swedish author Vilhelm Moberg in the mid-20th century wrote a series of four novels describing one Swedish family's migration from Småland to Minnesota in the late 19th century, a destiny shared by almost one million people. The author emphasizes the authenticity of the experiences as depicted (although he did change names).[195] These novels have been translated into English (The Emigrants, 1951, Unto a Good Land, 1954, The Settlers, 1961, The Last Letter Home, 1961). The musical Kristina från Duvemåla by ex-ABBA members Björn Ulvaeus and Benny Andersson is based on this story.[196][197]

The Immigrant is a musical by Steven Alper, Sarah Knapp, and Mark Harelik. The show is based on the story of Harelik's grandparents, Matleh and Haskell Harelik, who traveled to Galveston, Texas in 1909.[198]

Documentary Films

In their documentary How Democracy Works Now: Twelve Stories, filmmakers Shari Robertson and Michael Camerini examine the American political system through the lens of immigration reform from 2001–2007. Since the debut of the first five films, the series has become an important resource for advocates, policy-makers and educators.[199]

That film series premiered nearly a decade after the filmmakers' landmark documentary film Well-Founded Fear which provided a behind-the-scenes look at the process for seeking asylum in the United States. That film still marks the only time that a film-crew was privy to the private proceedings at the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS), where individual aslyum officers ponder the often life-or-death fate of immigrants seeking asylum.

Legal perspectives

University of North Carolina law professor Hiroshi Motomura has identified three approaches the United States has taken to the legal status of immigrants in his book Americans in Waiting: The Lost Story of Immigration and Citizenship in the United States. The first, dominant in the 19th century, treated immigrants as in transition; in other words, as prospective citizens. As soon as people declared their intention to become citizens, they received multiple low-cost benefits, including the eligibility for free homesteads in the Homestead Act of 1869, and in many states, the right to vote. The goal was to make the country more attractive, so large numbers of farmers and skilled craftsmen would settle new lands. By the 1880s, a second approach took over, treating newcomers as "immigrants by contract". An implicit deal existed where immigrants who were literate and could earn their own living were permitted in restricted numbers. Once in the United States, they would have limited legal rights, but were not allowed to vote until they became citizens, and would not be eligible for the New Deal government benefits available in the 1930s. The third and more recent policy[when?] is "immigration by affiliation", which Motomura argues is the treatment which depends on how deeply-rooted people have become in the country. An immigrant who applies for citizenship as soon as permitted, has a long history of working in the United States, and has significant family ties, is more deeply affiliated and can expect better treatment.[200]

It has been suggested that the US should adopt policies similar to those in Canada and Australia and select for desired qualities such as education and work experience. Another suggestion is to reduce legal immigration because of being a relative, except for nuclear family members, since such immigrations of extended relatives, who in turn bring in their own extended relatives, may cause a perpetual cycle of "chain immigration".[105]

Interpretive perspectives

The American Dream is the belief that through hard work and determination, any United States immigrant can achieve a better life, usually in terms of financial prosperity and enhanced personal freedom of choice.[201] According to historians, the rapid economic and industrial expansion of the U.S. is not simply a function of being a resource rich, hard working, and inventive country, but the belief that anybody could get a share of the country's wealth if he or she was willing to work hard.[202] This dream has been a major factor in attracting immigrants to the United States.[203]

See also

- Adoption in the United States

- Demographics of the United States

- Emigration from the United States

- European colonization of the Americas

- History of laws concerning immigration and naturalization in the United States

- How Democracy Works Now: Twelve Stories

- Illegal immigration to the United States

- Political demography

- United States immigration statistics

- United States visas

Footnotes

- ^ U.S. population hits 300 million

- ^ "Nancy Foner, George M. Fredrickson, Not Just Black and White: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Immigration, Race, and Ethnicity in the United States (2005) p.120.

- ^ "Immigrants in the United States and the Current Economic Crisis", Demetrios G. Papademetriou and Aaron Terrazas, Migration Policy Institute, April 2009.

- ^ "Immigration Worldwide: Policies, Practices, and Trends". Uma A. Segal, Doreen Elliott, Nazneen S. Mayadas (2010),

- ^ "Naturalizations in the United States: 2008". Office of Immigration Statistics Annual Flow Report.

- ^ "Immigrant Population at Record 40 Million in 2010". Yahoo! News. October 6, 2011.

- ^ Archibold, Randal C. (2007-02-09). "Illegal Immigrants Slain in an Attack in Arizona". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ^ "Family Reunification", Ramah McKay, Migration Policy Institute.

- ^ "CBO: 748,000 Foreign Nationals Granted U.S. Permanent Residency Status in 2009 Because They Had Immediate Family Legally Living in America". CNSnews.com. January 11, 2011

- ^ Cheryl Sullivan (January 15, 2011). "US Cancels 'virtual fence'". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ^ "Leaving England: The Social Background of Indentured Servants in the Seventeenth Century", The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- ^ "Indentured Servitude in Colonial America". Deanna Barker, Frontier Resources.

- ^ a b "A Look at the Record: The Facts Behind the Current Controversy Over Immigration". American Heritage Magazine. December 1981. Volume 33, Issue 1.

- ^ Schultz, Jeffrey D. (2002). Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics: African Americans and Asian Americans. p. 284. ISBN 9781573561488. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

- ^ "A Nation of Immigrants". American Heritage Magazine. February/March 1994. Volume 45, Issue 1.

- ^ Nicholas J. Evans,"Indirect passage from Europe: Transmigration via the UK, 1836–1914", in Journal for Maritime Research , Volume 3, Issue 1 (2001), pp. 70-84.

- ^ Wilson, Donna M (2008). Dying and Death in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 27. ISBN 9781551118734.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Will, George P. (2 May 2010). "The real immigration scare tactics". Washington, DC: Washington Post. pp. A17.

- ^ "TURN OF THE CENTURY (1900-1910)". HoustonHistory.com.

- ^ "An Introduction to Bilingualism: Principles and Processes". Jeanette Altarriba, Roberto R. Heredia (2008). p.212. ISBN 0805851356

- ^ "Old fears over new faces", The Seattle Times, September 21, 2006

- ^ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- ^ Persons Obtaining Legal Permanent Resident Status in the United States of America, Source: US Department of Homeland Security

- ^ A Great Depression?, by Steve H. Hanke, Cato Institute

- ^ Thernstrom, Harvard Guide to American Ethnic Groups (1980)

- ^ The Great Depression and New Deal, by Joyce Bryant, Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute.

- ^ Navarro, Armando, Mexicano political experience in occupied Aztlán (2005)

- ^ (U.S. Senate, Subcommittee on Immigration and Naturalization of the Committee on the Judiciary, Washington, D.C., Feb. 10, 1965. pp. 1-3.)

- ^ Peter S. Canellos (November 11, 2008). "Obama victory took root in Kennedy-inspired Immigration Act" (Document). The Boston Globe.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ "Trends in International Migration 2002: Continuous Reporting System on Migration". Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (2003). OECD Publishing. p.280. ISBN 9264199497

- ^ Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. pp. 268–269. ISBN 0465041957.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics: African Americans and Asian Americans". Jeffrey D. Schultz (2000). Greenwood Publishing Group. p.282. ISBN 1573561487

- ^ "The Paper curtain: employer sanctions' implementation, impact, and reform". Michael Fix (1991). The Urban Insitute. p.304. ISBN 0877665508

- ^ "New Limits In Works on Immigration / Powerful commission focusing on families of legal entrants". San Francisco Chronicle. June 2, 1995

- ^ Plummer Alston Jones (2004). "Still struggling for equality: American public library services with minorities". Libraries Unlimited. p.154. ISBN 1591582431

- ^ Mary E. Williams, Immigration. 2004. Page 69.

- ^ a b "Study: Immigration grows, reaching record numbers". USATODAY.com. December 12, 2005.

- ^ "Immigration surge called 'highest ever'". Washington Times. December 12, 2005.

- ^ "Debate Could Turn on a 7-Letter Word". The Washington Post. May 30, 2007.

- ^ "A Reagan Legacy: Amnesty For Illegal Immigrants". NPR: National Public Radio. July 4, 2010

- ^ "Crisis hits Hispanic community hard". France24. February 27, 2009.

- ^ "Immigrants top native born in U.S. job hunt". CNNMoney.com. October 29, 2010.

- ^ “U.S. Legal Permanent Residents: 2009”. Office of Immigration Statistics Annual Flow Report.

- ^ "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2010". U.S. Department of Homeland Security

- ^ The New Americans, Smith and Edmonston, The Academy Press. Page 5253.

- ^ The New Americans, Smith and Edmonston, The Academy Press. Page 54.

- ^ The New Americans, Smith and Edmonston, The Academy Press. Page 56.

- ^ The New Americans, Smith and Edmonston, The Academy Press. Page 58 ("Immigrants have always moved to relatively few places, settling where they have family or friends, or where there are people from their ancestral country or community.").

- ^ http://www.publicagenda.org/pages/immigrants 2009 report available for download, "A Place to Call Home: What Immigrants Say Now About Life in America"

- ^ "Americans Return to Tougher Immigration Stance". Gallup.com. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

- ^ Public Agenda Confidence in U.S. Foreign Policy Index

- ^ "Governor candidates oppose sanctuary cities". San Francisco Chronicle. August 4, 2010.

- ^ "Sanctuary Cities, USA". Ohio Jobs & Justice PAC.

- ^ Mary E. Williams, Immigration. (San Diego: GreenHaven Press) 2004. Page 82.

- ^ "Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants in the United States", Aaron Terrazas and Jeanne Batalova, Migration Policy Institute, October 2009.

- ^ "Global Migration: A World Ever More on the Move". The New York Times. June 25, 2010.

- ^ "Illegal Immigrants Estimated to Account for 1 in 12 U.S. Births". The Wall Street Journal. August 12, 2010.

- ^ Know the flow - economics of immigration

- ^ Illegal immigrants in the US: How many are there?

- ^ http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/44.pdf

- ^ Characteristics of the Foreign Born in the United States: Results from Census 2000

- ^ US population to 'double by 2100', BBC

- ^ US Faced with a Mammoth Iraq Refugee Crisis

- ^ United States Unwelcoming to Iraqi Refugees

- ^ Latinos and the Changing Face of America - Population Reference Bureau

- ^ More than 100 million Latinos in the U.S. by 2050

- ^ US - Census figures show dramatic growth in Asian, Hispanic populations

- ^ Population Growth And Immigration, U.S. Has Highest Population Growth Rate Of All Developed Nations - CBS News

- ^ Mary E. Williams, Immigration. (San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 2004). Page 83.

- ^ Pew Research Center: Immigration to Play Lead Role In Future U.S. Growth

- ^ U.S. Hispanic population to triple by 2050, USATODAY.com

- ^ Study Sees Non-Hispanic Whites Shrinking to Minority Status in U.S. - February 12, 2008, The New York Sun

- ^ Whites to become minority in U.S. by 2050, Reuters

- ^ Asthana, Anushka (2006-08-21). "Changing Face of Western Cities". Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ^ Whites Now A Minority In California, Census: Non-Hispanic Whites Now 47% Of State's Population, CBS News

- ^ "California QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau:". US Census Bureau. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^ Is the Melting Pot Still Hot? Explaining the Resurgence of Immigrant Segregation, David M. Cutler, Edward L. Glaeser, Jacob L. Vigdor, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2005.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/s11113-007-9035-8, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/s11113-007-9035-8instead. - ^ Survey results reported in Simon, Julian L. (1989) The Economic Consequences of Immigration Boston: Basil Blackwell are discussed widely and available as of September 12, 2007 at a Cato group policy paper by Simon here [1]. They find that 81 percent of the economists surveyed felt that 20th century immigration had very favorable effects, and 74 percent felt that illegal immigration had positive effects, with 76 percent feeling that recent immigration has "about the same effect" as immigrants from past years.

- ^ The Immigration Debate / Effect on Economy

- ^ James p. Smith, Chair. The New Americans: Economic, Demographic, and Fiscal Effects of Immigration (1997) Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education (CBASSE), National Academy of Sciences. page 5

- ^ "The Impact of Unauthorized Immigrants on the Budgets of State and Local Governments (December 2007)". /Congress of the United States Congressional Budget Office.

- ^ "Cost of Illegal Immigrants". FactCheck.org. April 6, 2009.

- ^ Lowenstein, Roger. "The Immigration Equation." The New York Times 9 July 2006.<http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/09/magazine/09IMM.html>

- ^ U.S. Census Press Releases

- ^ Smith (1997) 7,8

- ^ Perez, Miguel (2006) "Hire education: Immigrants aren't taking jobs from Americans" Chicago Sun-Times Aug. 22, 2006, available here [2]

- ^ "CATO Institute Finds $180 Billion Benefit to Legalizing Illegal Immigrants".

- ^ Riley, Jason. Let Them In: The Case for Open Borders. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-592-40349-3.

- ^ Immigration

- ^ Kusum Mundra (October 18, 2010). "Immigrant Networks and U.S. Bilateral Trade: The Role of Immigrant Income". papers.ssrn. SSRN 1693334.

... this paper finds that the immigrant network effect on trade flows is weakened by the increasing level of immigrant assimilation.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Council of Economic Advisers | The White House

- ^ Immigration: Google Makes Its Case

- ^ "Manhattan's Chinatown Pressured to Sell Out". The Washington Post. May 21, 2005.

- ^ Smith (1997) page 6

- ^ Samuelson, Robert (2007) "Importing poverty" Washington Post, September 5, 2007 (Accessible as of September 12, 2007 here [3])

- ^ Center for Immigration Studies

- ^ Importing Poverty: Immigration and Poverty in the United States: A Book of Charts

- ^ Immigrants hit hard by slowdown, subprime crisis

- ^ Banks help illegal immigrants own their own home, CNN/Money, August 8, 2005

- ^ HUD: Five Million Fraudulent Mortgages Held by Illegals

- ^ KFYI - "The Valley's Talk Station"

- ^ Sunnucks, Mike (October 9, 2008). "HUD cries foul over illegal immigrant mortgage data".

- ^ a b The Congealing Pot--Today's Immigrants Are Different from Waves Past, Jason Richwine, National Review, August 24, 2009. http://www.aei.org/article/100860

- ^ "/ Black Asian women make income gains". MSNBC. March 27, 2005

- ^ Gabriel J. Chin. "/ The Civil Rights Revolution Comes to Immigration Law: A New Look at the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965" (1996-1997). Social Science Research Network. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- ^ "Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2008". U.S. Census Bureau, 2009. P. 8.

- ^ Gergia General Assembly: HB 87 - Illegal Immigration Reform and Enforcement Act of 2011

- ^ Guardian newspaper: Kansas prepares for clash of wills over future of unauthorised immigrants - Coalition of top [Kansas] businesses launch new legislation that would help undocumented Hispanics gain federal work permission. 2 February 2012

- ^ Digital History

- ^ PBS Newshour, "Juan Williams Firing: What Speech Is OK as Journalism Evolves?" Oct. 22, 2010 online

- ^ The black-Latino blame game

- ^ Gang rivalry grows into race war

- ^ Race relations | Where black and brown collide | Economist.com

- ^ Riot Breaks Out At Calif. High School, Melee Involving 500 People Erupts At Southern California School

- ^ JURIST - Paper Chase: Race riot put down at California state prison

- ^ Racial segregation continues in California prisons

- ^ A bloody conflict between Hispanic and black American gangs is spreading across Los Angeles

- ^ The Hutchinson Report: Thanks to Latino Gangs, There’s a Zone in L.A. Where Blacks Risk Death if They Enter

- ^ African immigrants face bias from blacks

- ^ Mexican Assimilation in the United States, Edward P. Lazear. In Mexican Immigration to the United States, George J. Borjas, University of Chicago Press, 2007, National Bureau of Economic Research

- ^ Charles H. Lippy, Faith in America: Organized religion today (2006) ch 6 pp 107-27

- ^ Hispanics turning back to Democrats for 2008 - USATODAY.com

- ^ Exit Poll of 4,600 Asian American Voters Reveals Robust Support for Democratic Candidates in Key Congressional and State Races

- ^ USC Knight Chair in Media and Religion

- ^ Giovanni Facchini, Anna Maria Mayda and Prachi Mishra, "Do Interest Groups affect US Immigration Policy?" Dec. 2, 2010 online

- ^ Facchini, Giovanni, Mayda, Anna Maria and Mishra, Prachi, Do Interest Groups Affect Immigration? (November 2007). IZA Discussion Paper No. 3183. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1048403

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2011.02.008, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.jpubeco.2011.02.008instead. - ^ POLLING AND EXPERTS MAKE CLEAR: LATINO VOTERS SHOWED UP & SAVED THE SENATE FOR THE DEMOCRATS

- ^ An Irish Face on the Cause of Citizenship, Nina Bernstein, March 16, 2006, The New York Times. [4]

- ^ National Council of La Raza, Issues and Programs » Immigration » Immigration Reform, [5]

- ^ Loaded rhetoric harms immigration movement, Bridget Johnson, USA Today, 5/2/2006

- ^ Mexican aliens seek to retake 'stolen' land, Washington Post, April 16, 2006.

- ^ Ethnic Lobbies and US Foreign Policy, David M. Paul and Rachel Anderson Paul, 2009, Lynne Rienner Publishers

- ^ Brown, Richard, et al. (1998) "Access to Health Insurance and Health Care for Mexican American Children in Immigrant Families" In Marcelo M. Suarez-Orozco, ed. Crossings: Mexican Immigration in Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Cambridge, Mass.: David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies and Harvard University Press pages 225-247

- ^ in fact, Simon, Juliana (1995) "Immigration: The Demographic and Economic Facts". Washington, D.C.: The Cato Institute and National Immigration Forum (available here [6]) finds that estimates of the cost of public health care provided to undocumented immigrants that have been used by the press have been extremely inflated

- ^ Simon (1995)

- ^ National Institutes of Health. Medical Encyclopedia Accessed 9/25/2006

- ^ Tuberculosis in the United States, 2004

- ^ U.S. tuberculosis cases at an all-time low in 2006, but drug resistance remains a threat

- ^ Tuberculosis among US Immigrants

- ^ AIDS virus invaded U.S. from Haiti: study

- ^ Key HIV strain 'came from Haiti'

- ^ Mexican Migrants Carry H.I.V. Home

- ^ Lifting Of HIV Ban Leaves Many Immigrants In Limbo : NPR

- ^ What Happens to the "Healthy Immigrant Effect"

- ^ notably, National Research Council. (1997) "From Generation to Generation: The Health and Well-Being of Children in Immigrant Families". Washington D.C.: National Academy Press (Available here [7])

- ^ Hispanic prisoners in the United States

- ^ John Hagan, Alberto Palloni. [8] Sociological Criminology and the Mythology of Hispanic Immigration and Crime]. Social Problems, Vol. 46, No. 4 (Nov., 1999), pp. 617-632

- ^ Sampson, Robert (March 11, 2006). "Open Doors Don't Invite Criminals". New York Times (Op-Ed).[9]

- ^ Migration Information Source: "Debunking the Myth of Immigrant Criminality: Imprisonment Among First- and Second-Generation Young Men" June 2006.

- ^ Rumbaut G. Ruben and Ewing A. Walter, The Myth of Immigrant Criminality and the Paradox of Assimilation,[10]

- ^ California Public Policy Institute: "Crime Corrections, and California - What does immigration have to do with it" February 2008.

- ^ Preston, Julia (February 26, 2008). "California: Study of Immigrants and Crime". The New York Times. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ a b Immigration and Crime Assessing a Conflicted Issue, Steven A. Camarota and Jessica M. Vaughan, November 2009, http://www.cis.org/articles/2009/crime.pdf

- ^ The Illegal-Alien Crime Wave by Heather Mac Donald, City Journal Summer 2004

- ^ Overpopulation and Over-Immigration Threaten Water Supply, Says Ad Campaign, Reuters, October 20, 2008

- ^ The Environmental Impact Of Immigration Into The United States

- ^ See, for instance, immigration reform group Federation for American Immigration Reform's page on Immigration & U.S. Water Supply

- ^ A World Without Water -Global Policy Forum- NGOs

- ^ Immigration & U.S. Water Supply

- ^ State looks to the sea for drinkable water

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1468-0335.2009.00803.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1468-0335.2009.00803.xinstead. - ^ Mary E. Williams, Immigration. (San Diego: GreenHaven Press, 2004). Page 85.

- ^ Rita James Simon and Mohamed Alaa Abdel-Moneim, Public opinion in the United States: studies of race, religion, gender, and issues that matter (2010) pp 61-2

- ^ "Worldviews 2002 Survey of American and European Attitudes and Public Opinion on Foreign Policy: US Report"

- ^ New Poll Shows Immigration High Among US Voter Concerns

- ^ a b Summary

- ^ Espenshade, Thomas J. and Belanger, Maryanne (1998) "Immigration and Public Opinion." In Marcelo M. Suarez-Orozco, ed. Crossings: Mexican Immigration in Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Cambridge, Mass.: David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies and Harvard University Press, pages 365-403

- ^ ”Legal vs. Illegal Immigration”. Public Agenda. December 2007.

- ^ "Refugees in Japan". Japan Times. 12 October 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ A New Era Of Refugee Resettlement

- ^ Presidential Determination on FY 2008 Refugee Admissions Numbers

- ^ U.S. Goals for Iraqi Refugees are Inadequate, Refugees International

- ^ "Refugees struggle as jobs dry up, fueling debate over U.S. obligation". The Dallas Morning News. March 1, 2009

- ^ "Office of Refugee Resettlement: Programs". United States Department of Health and Human Services.

- ^ David W. Haines, Safe Haven?: A History of Refugees in America (2010) p 177

- ^ Edwin T. Gania. U.S. Immigration Step by Step (2004) p 65

- ^ Immigration and Nationality Act, Section 240A online

- ^ Ivan Vasic, The Immigration Handbook (2008) p. 140

- ^ James H. Dormon, "Ethnic Stereotyping in American Popular Culture: The Depiction of American Ethnics in the Cartoon Periodicals of the Gilded Age," Amerikastudien, 1985, Vol. 30 Issue 4, pp 489-507

- '^ Rachel Rupin and Jeffrey Melnick, Immigration and American Popular Culture: An Introduction (2006)

- ^ James H. Dorman, "American Popular Culture and the New Immigration Ethnics: The Vaudeville Stage and the Process of Ethnic Ascription," Amerikastudien, 1991, Vol. 36#2 pp 179-193

- ^ Yasmeen Abu-Laban and Victoria Lamont, "Crossing borders: Interdisciplinary, immigration and the melting pot in the American cultural imaginary," Canadian Review of American Studies, 1997, Vol. 27#2, pp 23-43

- ^ Michael Rogin, Blackface White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot (1996)