Thar Desert: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

Someguy1221 (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 210.7.21.63 to last revision by The Anomebot2 (HG) |

→Desert economy: The camel shown is not the kind found in the Thar |

||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

===Livestock=== |

===Livestock=== |

||

[[File:Thar Khuri.jpg|thumb|Camel ride in the Thar desert near Jaisalmer.]] |

|||

[[Image:07. Camel Profile, near Silverton, NSW, 07.07.2007.jpg|thumb|Camel]] |

|||

In the last 15-20 years, the Rajasthan desert has seen many changes, including a manifold increase of both the human and animal population. [[Animal husbandry]] has become popular due to the difficult farming conditions. At present, there are ten times more animals per person in Rajasthan than the national average, and overgrazing is also a factor affecting climatic and drought conditions. |

In the last 15-20 years, the Rajasthan desert has seen many changes, including a manifold increase of both the human and animal population. [[Animal husbandry]] has become popular due to the difficult farming conditions. At present, there are ten times more animals per person in Rajasthan than the national average, and overgrazing is also a factor affecting climatic and drought conditions. |

||

Revision as of 18:00, 24 March 2009

The Thar Desert (Hindi: थार मरुस्थल), also known as the Great Indian Desert, is a large, arid region in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent. With an area of more than 200,000 sq. km.,[1] (77,000 sq. mi.) it is world's 18th largest. It lies mostly in the Indian state of Rajasthan, and extends into the southern portion of Haryana and Punjab states and into northern Gujarat state. In Pakistan, the desert covers eastern Sind province and the southeastern portion of Pakistan's Punjab province. The Cholistan Desert adjoins the Thar desert spreading into Pakistani Punjab province.

The Thar Desert is bounded on the northwest by the Sutlej River, on the east by the Aravalli Range, on the south by the salt marsh known as the Rann of Kutch (parts of which are sometimes included in the Thar), and on the west by the Indus River. Its boundary to the large thorny steppe to the north is ill-defined. Depending on what areas are included or excluded, the nominal size of the Thar can vary significantly.

Origin of the Thar Desert

The origin of the Thar Desert is a controversial subject. Some consider it to be 4000 to 1,000,000 years old, whereas others state that aridity started in this region much earlier. Another theory states that area turned to desert relatively recently: perhaps around 2000 - 1500 BC. Around this time the Ghaggar ceased to be a major river. It now terminates in the desert. It has been observed through remote sensing techniques that Late Quaternary climatic changes and neotectonics have played a significant role in modifying the drainage courses in this part and a large number of palaeochannels exist.

Most of the studies share the opinion that the palaeochannels of the Sarasvati coincide with the bed of present day Ghaggar and believe that the Sutlej along with the Yamuna once flowed into the present Ghaggar riverbed. It has been postulated that the Sutlej was the main tributary of the Ghaggar and that subsequently the tectonic movements might have forced the Sutlej westwards, the Yamuna eastwards and thus dried up the Ghaggar.

Physiography and geology

There are three principal landforms in the desert region i.e.

It is a desolate country where sand is piled up into huge wind blown dunes (technically this is known as an erg). The sand dunes are of three types viz., longitudinal parabolic, transverse and barchans. The first type, running NNE-SSW, i.e. parallel to the prevailing winds, occurs to the south and west of the Thar. The transverse dunes, aligned across the wind direction, to the east and south of Thar and barchans, with the conclave sides facing the wind in the interior, predominant in Central Thar. On the whole the Thar Desert slopes imperceptibly towards the Indus Plain and surface unevenness is mainly due to sand dunes. The dunes in the south are higher, rising sometimes to 152 m whereas in the north they are lower and rise to 16 m above the ground level.

The Aravalli Range forms the main landmark to the south-east of Thar Desert. The more humid conditions that prevail near the Aravallis prevent the extension of Thar Desert towards the east and the Ganges Valley. In the heart of the sand covered area, the bare, dune free country of Barmer, Jaisalmer and Bikaner present an anomaly.[2]

Desert soils

The soils of the Arid Zone are generally sandy to sandy-loam in texture. The consistency and depth vary according to the topographical features. The low-lying loams are heavier and may have a hard pan of clay, calcium carbonate (CaCO3) or gypsum. The pH varies between 7 and 9.5. The soils improve in fertility from west and northwest to east and northeast. Desert soils are Regosols of wind blown sand and sandy fluiratile deposits, derived from the disintegration of rock in the subjacent areas and blown in from the coastal region and the Indus Valley. The desert soils occupy the districts of Jodhpur, Bikaner, Churu, Ganganagar, Barmer, Jaisalmer, and Jalore. The Thar consists mainly of the wind-blown sand. The area is covered not only by sheet of sand but also of rocky projections of low elevations which constitute the older rocks of the country. Water is scarce and occurs at great depths, from 30 to 120 m below the ground level.[3]

Some of these soils contain a high percentage of soluble salts in the lower horizons, turning water in the wells poisonous. Being poor in organic matter they show a low loss on ignition. They contain varying amount of calcium carbonate.

Biodiversity

Stretches of sand in the desert are interspersed by hillocks and sandy and gravel plains. Due to the diversified habitat, the vegetation and animal life in this arid region is very rich. About 23 species of lizard and 25 species of snakes are found here and several of them are endemic to the region.

Some wildlife species, which are fast vanishing in other parts of India, are found in the desert in large numbers such as the Great Indian Bustard (Ardeotis nigriceps), the Blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra), the Indian Gazelle (Gazella bennettii) and the Indian Wild Ass (Equus hemionus khur) in the Rann of Kutch. They have evolved excellent survival strategies, their size is smaller than other similar animals living in different conditions, and they are mainly nocturnal. There are certain other factors responsible for the survival of these animals in the desert. Due to the lack of water in this region, transformation of the grasslands into cropland has been very slow. The protection provided to them by a local community, the Bishnois, is also a factor.

The Desert National Park, Jaisalmer, spread over an area of 3162 km², is an excellent example of the ecosystem of the Thar Desert, and its diverse fauna. Great Indian Bustard, Blackbuck, chinkara, desert fox, Bengal fox, wolf, desert cat etc. can be easily seen here. Seashells and massive fossilized tree trunks in this park record the geological history of the desert. The region is a haven for migratory and resident birds of the desert. One can see many eagles, harriers, falcons, buzzards, kestrel and vultures. Short-toed Eagles (Circaetus gallicus), Tawny Eagles (Aquila rapax), Spotted Eagles (Aquila clanga), Laggar Falcons (Falco jugger) and kestrels are the commonest of these.

Tal Chhapar Sanctuary is a very small sanctuary in Churu District, 210 km from Jaipur, in the Shekhawati region. This sanctuary is home to a large population of graceful Blackbuck. Desert Fox and desert cat can also be spotted along with typical avifauna such as partridge and sand grouse.

Natural vegetation

The natural vegetation is classed as Northern Desert Thorn Forest (Champion 1936). These occur in small clumps scattered in a more or less open forms. Density and size of patches increase from West to East following the increase in rainfall. Natural vegetation of Thar Desert is composed of following tree, shrub and herb species.[4]

Tree species

Acacia jacquemontii, Acacia leucophloea, Acacia senegal, Anogeissus rotundifolia, Prosopis cineraria, Salvadora oleoides, Tecomella undulata, Tamarix articulata

Small trees and shrubs

Calligonum polygonoides, Acacia jacquemontii, Balanites roxburghii, Ziziphus zizyphus, Ziziphus nummularia, Calotropis procera, Suaeda fruticosa, Crotalaria burhia, Aerva tomentosa, Clerodendrum multiflorum, Leptadenia pyrotechnica, Lycium barbarum, Grewia populifolia, Commiphora mukul, Euphorbia neriifolia, Cordia rothii, Maytenus emarginata, Capparis decidua.

Herbs

Eleusine compressa, Dactyloctenium scindicum, Cenchrus biflorus, Cenchrus setigerus, Lasiurus hirsutus, Cynodon dactylon, Panicum turgidum, Panicum antidotale, Dichanthium annulatum, Sporobolus marginatus, Saccharum spontaneum, Cenchrus ciliaris, Desmostachya bipinnata, Cyperus arenarius, Erogrostis species, Ergamopagan species, Phragmitis species, Typha species

Greening desert and checking shifting sand dunes

The soil of the Thar Desert remains dry for much of the year and is prone to wind erosion. High velocity winds blow soil from the desert, depositing some on neighboring fertile lands, and causing shifting sand dunes within the desert, which bury fences and block roads and railway tracks. Permanent solution to this problem of shifting sand dunes can be provided by fixation of the shifting sand dunes with suitable plant species and planting windbreaks and shelterbelts. They also provide protection from hot or cold and desiccating winds and the invasion of sand.

There are few local tree species suitable for planting in the desert region and these are slow growing. The introduction of exotic tree species in the desert for plantation has become necessary. Many species of Eucalyptus, Acacia, Cassia and other genera from Israel, Australia, USA, Russia, Southern Rhodesia, Chile, Peru and Sudan have been tried in Thar Desert. Acacia tortilis has proved to be the most promising species for desert afforestation and the jojoba is another promising species of economic value found suitable for planting in these areas.

The Rajasthan Canal system is the major irrigation scheme of the Thar Desert and is conceived to reclaim it and also to check spreading of the desert to fertile areas. The river Luni is the only natural water source that drains inside a lake in the desert.

Desert economy

Agriculture

The main occupations of people living in the desert are agriculture and animal husbandry. Agriculture is not a dependable proposition in this area-- after the rainy season, at least 33% of crops fail. Animal husbandry, trees and grasses, intercropped with vegetables or fruit trees, is the most viable model for arid, drought-prone regions. The region faces frequent droughts. Overgrazing due to high animal populations, wind and water erosion, mining and other industries result in serious land degradation.

Livestock

In the last 15-20 years, the Rajasthan desert has seen many changes, including a manifold increase of both the human and animal population. Animal husbandry has become popular due to the difficult farming conditions. At present, there are ten times more animals per person in Rajasthan than the national average, and overgrazing is also a factor affecting climatic and drought conditions.

Agro-forestry

Forestry has an important part to play in the amelioration of the conditions in semi-arid and arid lands. If properly planned forestry can make an important contribution to the general welfare of the people living in desert areas. The living standard of the people in the desert is low. They can not afford other fuels like gas, kerosene etc. Fire wood is their main fuel, of the total consumption of wood about 75 percent is firewood. The forest cover in desert is low. The forest is insufficient to fulfill the need of firewood. This diverts the much needed cattledung from the field to the hearth. This in turn results into the decrease in agricultural production.

The scientists of Central Arid Zone Research Institute (CAZRI), have successfully developed and improved dozens of traditional and non-traditional crops/fruits, such as Ber trees (like plums) that produce much larger fruits than before (lemon-size) and can thrive with minimal rainfall. These trees have become a profitable option for farmers. One example from a case study of horticulture showed that in situation of budding in 35 plants of Ber and Guar (Gola, Seb & Mundia variety developed in CAZRI), using only one hectare of land, yielded 10,000 kg. of Ber and 250 kg. of Guar, which translates into double or even triple profit.[5]

The most important tree species, in Agro-forestry , providing livelihood support in Thar desert is Prosopis cineraria.

Prosopis cineraria provides wood of construction class. It is used for house-building, chiefly as rafters, posts scantlings, doors and windows, and for well construction water pipes, upright posts of Persian wheels, agricultural implements and shafts, spokes, fellows and yoke of carts. It can also be used for small turning work and tool-handles. Container manufacturing is another important wood based industry, which depends heavily on desert grown trees.

Prosopis cineraria is much valued as a fodder tree. The trees are heavily lopped particularly during winter months when no other green fodder is available in the dry tracts. There is a popular saying that death will not visit a man, even at the time of a famine, if he has a Prosopis cineraria, a goat and a camel, since the three together are some what said to sustain a man even under the most trying condition. The forage yield per tree varies a great deal. On an average, the yield of green forage from a full grown tree is expected to be about 60 kg with complete lopping having only the central leading shoot, 30 kg when the lower two third crown is lopped and 20 kg when the lower one third crown is lopped. The leaves are of high nutritive value. Feeding of the leaves during winter when no other green fodder is generally available in rain-fed areas is thus profitable. The pods are a sweetish pulp and are also used as fodder for livestock.

Prosopis cineraria is most important top feed species providing nutritious and highly palatable green as well as dry fodder, which is readily eaten by camels, cattle, sheep and goats, constituting a major feed requirement of desert livestock. Locally it is called Loong. Pods are locally called sangar or sangri. The dried pods locally called Kho-Kha are eaten. Dried pods also form rich animal feed, which is liked by all livestock. Green pods also form rich animal feed, which is liked by drying the young boiled pods. They are also used as famine food and known even to prehistoric man. Even the bark, having an astringent bitter taste, was reportedly eaten during the severe famine of 1899 and 1939. Pod yield is nearly 1.4 quintals of pods/ha with a variation of 10.7% in dry locations.

Prosopis cineraria wood is reported to contain high calorific value and provide high quality fuel wood. The lopped branches are good as fencing material.

Tecomella undulata is tree species, locally known as Rohida, found in Thar Desert regions of northwest and western India, is another important medium sized tree of great use in Agro-forestry, that produces quality timber and is the main source of timber amongst the indigenous tree species of desert regions. The trade name of the tree species is Desert teak or Marwar teak.

Tecomella undulata is mainly used as a source of timber. Its wood is strong, tough and durable. It takes a fine finish. Heartwood contains quinoid. The wood is excellent for firewood and charcoal. Cattle and goats eat leaves of the tree. Camels, goats and sheep consume flowers and pods.

Tecomella undulata plays an important role in the ecology. It acts as a soil-binding tree by spreading a network of lateral roots on the top surface of the soil. It also acts as a windbreak and helps in stabilizing shifting sand dunes. It is considered as the home of birds and provides shelter for other desert wildlife. Shade of tree crown is shelter for the cattle, goats and sheep during summer days.

Tecomella undulata has medicinal properties as well. The bark obtained from the stem is used as a remedy for syphilis. It is also used in curing urinary disorders, enlargement of spleen, gonorrhoea, leucoderma and liver diseases. Seeds are used against abscess.

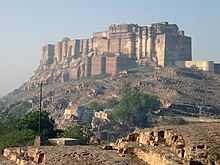

Ecotourism

Desert safaris on camels have become increasingly popular around Jaisalmer. Both foreigners as well as the rapidly growing Indian middle (and upper) class frequent the desert seeking adventure on camels for anything from a day to several days. This industry ranges from cheaper backpacker treks to plush Arabian night style campsites replete with banquets and cultural performances. During the treks tourists are able to view the fragile and beautiful ecosystem of the Thar desert. This form of tourism provides income to many operators and camel owners in Jaisalmer as well as employment for many camel trekers in the desert villages nearby.

People

The main occupation of the people in desert is agriculture and animal husbandry. In past years there has been a tremendous increase in human population as well as animal population. This has led to improper control of grazing and extensive cultivation resulting into the deterioration of vegetation resources. The increase of human and livestock population in the desert has led to deterioration in the ecosystem resulting in degradation of soil fertility. The living standard of the people in the desert is low. The Thar desert is the most densely populated desert in the world, with a population density of 83 persons per sq. km. vs 7 in other deserts.[6]

Jodhpur, the largest city in the region, lies in the scrub forest zone. Bikaner and Jaisalmer are located in the desert proper.

A large irrigation and power project has reclaimed areas of the northern and western desert for agriculture. The small population is mostly pastoral, and hide and wool industries are prominent.

The Indian Desert is mainly inhabited by Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs. The portion in Pakistan is inhabited by primarily by Sindhis and Kolhis. A colorful culture rich in tradition prevails in the desert. The people have a great passion for music and poetry.

Water and housing in the desert

In Pakistan, the desert covers eastern Sind province and the southeastern portion of Pakistan's Punjab province. Tharparkar district is one of the major parts under the desert. areaTharparkar consists of two words, Thar means ‘desert’ while Parkar stands for ‘the other side’. Years back, it was known as Thar and Parkar but subsequently became just one word ‘Tharparkar’ for the two distinct parts of Sindh province. On the western side, Parkar is the irrigated area whereas Thar, the eastern part, is known as the largest desert of Pakistan with a rich multifaceted culture, heritage, traditions, folk tales, dances and music due to its inhabitants who belong to different religions, sects and casts. The Parkar area has been formed by the alluvial deposits of river Indus while Thar mostly consists of barren tracts of sand dunes covered with thorny bushes. The only hills of the district, named Karon-Jhar, are in the extreme south-east corner of Nagar Parkar Taluka, a part of Thar. These hills are spread over about 20 kilometers in length and attains a height of 300 meters. Covered with sparse jungle and pasturage, they give rise to two perennial springs as well as streams caused after rain. [7]

The rains play a vital role in the life of all parts of Thar as the water deposits in johads or tobas (small ponds) are used for drinking, washing and other purposes. These tobas are the only source of water for animals and human in most of the desert area. Just for this reason, major portion of the population lives like gypsies. When a toba comes to dry, they move to the next destination around the water-filled toba. The human settlements are mostly found near the Karon-Jhar hills where two seasonal streams flow but not in all the seasons. The underground water is rarely found in Thar desert. If luckily found, after digging a very deep well, it comes out quite sour and putrid. Simply undrinkable. Sometimes fortune do knock the doors of the Thar inhabitants, when sweet water comes out of a very deeply dug well. Then the housing units start increasing around that well. Digging the well is not so easy a number of times, it claims the lives of the well-diggers. According to 1980 housing census, there were 241,326 housing units of one or two very small rooms. The degree of crowding was six persons per housing unit and three persons per room.[7]

For most of the housing units (approximately 76 per cent), the main construction material of outer walls is unbaked bricks whereas wood is used in 10 per cent and baked bricks or stones with mud bonding in 8 per cent housing units. A large number of families still live in jhugis or huts which are housing units formed with straws and thin wood-sticks. The wind storm proves these jhugis unsustainable all the times. But the poverty leaves no other option to these jhugiwalas (people living in jhugis). [7]

Desert for recreation

Thar desert provides the recreational value in terms of desert festivals organized every year. Rajasthan desert festivals are celebrated with great zest and zeal. This festival is held once a year during winters. Dressed in brilliantly hued costumes, the people of the desert dance and sing haunting ballads of valor, romance and tragedy. The fair has snake charmers, puppeteers, acrobats and folk performers. Camels, of course, play a stellar role in this festival, where the rich and colorful folk culture of Rajasthan can be seen.

Camels are an integral part of the desert life and the camel events during the Desert Festival confirm this fact. Special efforts go into dressing the animal for entering the spectacular competition of the best-dressed camel. Other interesting competitions on the fringes are the moustache and turban tying competitions, which not only demonstrate a glorious tradition but also inspire its preservation. Both the turban and the moustache have been centuries old symbols of honor in Rajasthan.

Evenings are meant for the main shows of music and dance. Continuing till late into the night, the number of spectators swells up each night and the grand finale, on the full moon night, takes place by silvery sand dunes.

See also

References

- ^ Thar Desert - Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ Kaul, R.N. (1970). Afforestation in Arid zones (edited): Dr. W. JUNK N.V. Publishers The Hague.

- ^ Kaul, R.N. (1970). Afforestation in Arid zones (edited): Dr. W. JUNK N.V. Publishers The Hague.

- ^ Kaul, R.N. (1970). Afforestation in Arid zones (edited): Dr. W. JUNK N.V. Publishers The Hague.

- ^ ARID AGRICULTURE: State-of-the-Art Agro-Forestry vs. Deserts on the March By Brook & Gaurav Bhagat August 14, 2003

- ^ Grasslands and Deserts

- ^ a b c Thar -- Pakistan’s largest desert of living traditions

Bold textItalic text' 'You Shag Fat Cunts

Further reading

- Govt. of India. Ministry of Food & Agriculture booklet (1965)- soil conservation in the Rajasthan Desert- Work of the Desert Afforestation Research station, Jodhpur.

- Kaul, R.N. (1970). Afforestation in Arid zones (edited): Dr. W. JUNK N.V. Publishers The Hague.

- Gupta, R.K. & Prakash Ishwar (1975). Environmental analysis of the Thar Desert. English Book Depot., Dehra Dun.

- Kaul, R.N. (1967). Trees or grass lands in the Rajasthan- Old problems and New approaches. Indian Forester, 93: 434-435.

- Burdak, L.R. (1982). Recent Advances in Desert Afforestation- Dissertation submitted to Shri R.N. Kaul, Director, Forestry Research, F.R.I., Dehra dun.

- Yashpal, Sahai Baldev, Sood, R.K., and Agarwal, D.P. (1980). "Remote sensing of the 'lost' Saraswati river." Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences (Earth and Planet Science), V. 89, No. 3, pp. 317-331.

- Bakliwal , P.C. and Sharma, S.B. (1980). "On the migration of the river Yamuna". Journal of the Geological Society of India, Vol. 21, Sept. 1980, pp. 461-463.

- Bakliwal, P.C. and Grover, A.K. (1988). "Signature and migration of Sarasvati river in Thar desert, Western India". Record of the Geological Survey of India V 116, Pts. 3-8, pp. 77-86.

- Rajawat, A.S., Sastry, C.V.S. and Narain, A. (1999-a). Application of pyramidal processing on high resolution IRS-1C data for tracing the migration of the Saraswati river in parts of the Thar desert. in "Vedic Sarasvati, Evolutionary History of a Lost River of Northwestern India", Memoir Geological Society of India, Bangalore, No. 42, pp. 259-272.

- Ramasamy, S.M. (1999). Neotectonic controls on the migration of Sarasvati river of the Great Indian desert. in "Vedic Sarasvati, Evolutionary History of a Lost River of Northwestern India", Memoir Geological Society of India, Bangalore, No. 42, pp. 153-162.

- Rajesh Kumar, M., Rajawat, A.S. and Singh, T.N. (2005). Applications of remote sensing for educidate the Palaeochannels in an extended Thar desert, Western Rajasthan, 8th annual International conference, Map India 2005, New Delhi.

External links

- Template:Wikitravel

- Thar Desert (World Wildlife Fund)

- Photos of the Thar desert

- Photos of the Thar desert in Pakistan side

- Information about Thar desert In Pakistan

- आपणो राजस्थान