East Pakistan: Difference between revisions

I am so sorry, Bizoy... I think this is O.K. now. |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

|region = [[South Asia]] |

|region = [[South Asia]] |

||

|country = Pakistan |

|country = Pakistan |

||

|status = Part the [[Dominion of Pakistan]] |

|||

|p1 = East Bengal |

|p1 = East Bengal |

||

|flag_p1 = Flag_of_Pakistan.svg |

|flag_p1 = Flag_of_Pakistan.svg |

||

Revision as of 08:18, 11 August 2013

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

East Pakistan مشرقی پاکستان পূর্ব পাকিস্তান | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1955–1971 | |||||||||

| Motto: "Unity, Faith, Discipline" | |||||||||

| Anthem: Qaumī Tarāna National anthem Pakistan Zindabad[citation needed] Long Live Pakistan | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Part the Dominion of Pakistan | ||||||||

| Capital | Dacca | ||||||||

| Common languages | Bengali (official) Bihari Urdu English | ||||||||

| Religion | Islam Hinduism | ||||||||

| Government | Socialist state (1954–58) Presidential republic (1960–69) Military government (1969–71) | ||||||||

| Administrator | |||||||||

• 1960–1962 | Azam Khan | ||||||||

• 1962–1969 | Abdul Monem Khan | ||||||||

• 1969–1971 | Syed Mohammad Ahsan | ||||||||

• 1971 | Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi | ||||||||

| Chief Minister | |||||||||

• 1955–1956, 1958 | Abu Hussain Sarkar | ||||||||

• 1956–1958 | Ata-ur-Rahman Khan | ||||||||

| Governors | |||||||||

• 1955–1956 | Amiruddin Ahmad | ||||||||

• 1956–1958 | A. K. Fazlul Huq | ||||||||

• 1958–1960 | Zakir Husain | ||||||||

| Legislature | Legislative Assembly | ||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||

| 1955 | |||||||||

| 22 November 1954 | |||||||||

| 26 March 1971 | |||||||||

| 3 December 1971 | |||||||||

| 16 December 1971 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 147,570 km2 (56,980 sq mi) | |||||||||

| Currency | Pakistani rupee | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

|

| This article is part of the series |

| Former administrative units of Pakistan |

|---|

| History of Bangladesh |

|---|

|

|

|

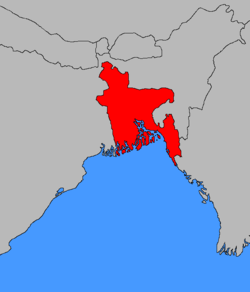

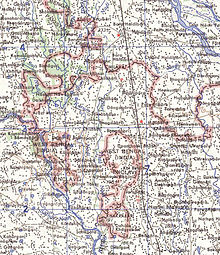

East Pakistan (Bengali: পূর্ব পাকিস্তান Pūrbô Pākistān; Urdu: مشرقی پاکستان Mašriqī Pākistān pronounced [məʃrɪqiː pɑːkɪst̪ɑːn]) was a provincial state of Pakistan that existed in the Bengal region of the northeast of South Asia from 1955 until 1971, following the One Unit programme which laid the existence of East Pakistan.[1]

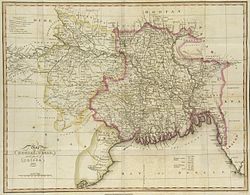

In 1947, the region of Bengal under the British Empire was divided into East and West Bengal which separated the Muslim majority eastern areas from the Hindu majority western areas.[2] The partition of Bengal saw the mainstream revival of Hindu-Muslim riots which drove both Bengali Muslims and Hindus further apart, leading to more unrest in Bengal.[3] In 1947, Muslim majority districts of Bengal favoured the division after approving the 3 June Plan presented by the Viceroy of India Lord Earl Mountbatten, and merged with the new province of East Bengal of the Dominion of Pakistan.[4][unreliable source?] From 1947 until 1954, East Bengal was an independent administrative unit which was governed by the Pakistan Muslim League led by Nurul Amin.[4] In 1955, the Bengali Prime minister Muhammad Ali Bogra devolved the province of East Bengal and established the state as East Pakistan with Dhaka its state capital.[1] During this time, the 1954 elections were held which saw the complete defeat of Pakistan Muslim League led by the United Front coalition of the Awami League, the Krishak Praja Party, the Democratic Party and Nizam-e-Islam.[5][6][7] The Awami League gained the control of East Pakistan after appointing Huseyn Suhrawardy for the office of Prime minister.[8][9] This authoritarian period that existed from 1958 until 1971, is often regarded as period of mass repression, resentment, and political neglect and ignorance.[10][11] Allying with the population of West, the East's population unanimously voted for Fatima Jinnah during the 1965 presidential elections against Ayub Khan.[12] The elections were widely believed to be heavily rigged in the favour of Ayub Khan using state patronage and intimidation to influence the indirectly elected electoral college.[12] The economic disparity, impression that West Pakistan despite being less populated than East Pakistan was ruling and prospering at its cost further popularize the Bengali nationalism.[13] The support for state autonomy grew when Awami League introduced the Six point movement in 1966,[14] and participated with full force in the 1970 general elections in which the Awami League had won and secured the exclusive mandate of East-Pakistan.[15][16]

After the general elections, President General Yahya Khan attempted to negotiate with both Pakistan Peoples Party and Awami League to share power in the central government but talks were failed when President Yahya Khan authorised an armed operation (codename Searchlight) to attack the Awami League.[15] As response to this operation, the Awami League announced the declaration of independence of East Pakistan on 26 March 1971 and began an armed struggle against the Pakistan, with India staunchly supporting Awami League by the means of providing arm ammunition to its guerrilla forces.[17]

East Pakistan had an area of 147,570 km2 (56,977 mi2), bordering India on three sides (East, North, and West) and the Bay of Bengal to the South. East Pakistan was one of the largest provincial states of Pakistan, with the largest population, largest political representation, and sharing the largest economic share.[11] A nine-month long war ended on 16 December 1971, when the Pakistan Armed Forces were overrun in Dhaka, ultimately signing the instrument of surrender which resulted in the largest number of prisoners of war since World War II.[17] Finally on 16 December 1971, East Pakistan was officially disestablished and was succeeded as the independent state of Bangladesh.[17]

Geographical history

Many notable Muslim Bengali figures were among the Founding fathers of present date, State of Pakistan. The country was born in bloodshed and came into existence on 14 August 1947 confronted by seemingly insurmountable problems.[citation needed] As many as 12 million people Muslims leaving India for Pakistan, and Hindus and Sikhs opting to move to India from the new state of Pakistan which had been involved in the mass transfer of population between the two countries, and perhaps two million refugees had died in the violence that had accompanied the migrations in the borders of West Pakistan. Pakistan's boundaries were established hastily without adequate regard for the new nation's economic viability.[citation needed] Even the minimal requirements of a central government, skilled personnel and officers, equipment, and a capital city with government buildings were missing. Until 1947, the East Wing of Pakistan, separated from the West Wing by 1,600 km of Indian territory, had been heavily dependent on Hindu management. Many Bengali Hindus left for Calcutta after independence, and their place, particularly in commerce, was taken mostly by Muslims who had migrated from the Indian state of Bihar or by West Pakistanis from different provinces.[citation needed]

Political history

Bengal was divided into two provinces on 3 July 1946 in preparation for the independence, the Hindu majority of West Bengal and the Muslim majority of East Bengal.[citation needed] The two provinces each had their own Chief Ministers and Governors. In August 1947, the West Bengal became part of India and East Bengal became part of Pakistan. Throughout this time, the tensions between East Bengal and the West Pakistan led to the One-Unit policy by Bengali Prime Minister Muhammad Ali Bogra.[citation needed] In 1955, most of the western wing was combined to form a new West Pakistan province (which contained four provinces and four territories) while East Bengal became the new province of East Pakistan (a single provisional state). In 1955, Bogra appointed communist leader Abu Hussain Sarkar as Chief Minister and Amiruddin Ahmad as Governor.[citation needed]

Following the promulgation of 1956 Constitution, Prime minister Bogra appointed Bengali bureaucrat and retired Major-General Iskander Mirza was as Interior minister and the Army Commander of army General Ayub Khan as the Defence minister whilst Muhammad Ali remained Economic minister. The main objective of the new government was to end disruptive provincial politics and to provide the country with a new constitution. After a revision, the Supreme Court of Pakistan declared that the Pakistan Constituent Assembly must be called. Governor-General Ghulam Mohammad was unable to circumvent the order, and the new Constituent Assembly, elected by the provincial assemblies, met for the first time in July 1955. Bogra, who had little support in the new assembly, fell in August and was replaced by Choudhry. Ghulam Mohammad, plagued by poor health, was succeeded as governor general in September 1955 by Mirza.[citation needed]

Language movement and 1954 provincial elections

Previously in 1952, then Chief Minister Nurul Amin who was firmly against the agitation, stated that the communists had played an integral and major role in staging the massive protests, mass demonstration, and strikes for the Bengali Language Movement.[18] All over the country, the political parties had favored the general elections in Pakistan with the exception of Muslim League.[19] The military, bureaucracy and the United States was nervous with good reasons where the support for the Soviet Union began to rise in both East and West.[19] Finally in 1954, the legislative elections were to be held for the Parliament.[19] Unlike in West, not all of the Hindu population migrated to India, instead a large number of Hindu population was in fact presented in the state.[19] The communist influence deepened and was finally realised in the elections. The United Front, Communist Party of Pakistan and the Awami League returned to power, inflicting sever defeat to Muslim League.[19] Out of 309, the Muslim League only won 10 seats, whereas the communist party had 4 seats of the ten contested. The communists working with other parties had secured 22 additional seats, totalling 26 seats. The right-wing Jamaat-e-Islami had completely failed in the elections.[19]

In 1955, the United Front named Abu Hussain Sarkar as the Chief minister of the State who ruled the state in two non-consecutive terms until 1958 when the martial law was imposed.[19]

Martial law

In East Pakistan, the political impasse culminated in 1958 in a violent scuffle in the East-Pakistan parliament between the members of the Pakistan Muslim League and the East-Pakistan police, in which the deputy speaker was fatally injured and two ministers badly wounded. Uncomfortable with the workings of democratic system, unruliness in the East Pakistan parliamentary elections and the threat of Baloch separatism in West-Pakistan, Bengali President Iskandar Ali Mirza issued a proclamation that abolished all political parties in both West and East Pakistan, abrogated the two-year old constitution, and imposed the first martial law in the country on 7 October 1958.

President Iskander Mirza announced that "the martial law would be a temporary measure, lasting only until a new constitution was to be drafted. On 27 October, President Mirza swore in a twelve-member cabinet that included Army Commander General Ayub Khan as Defence Minister as well as chief martial law administrator of the country, along with three other senior military officers in ministerial positions. The cabinet included among the eight civilians, one of them being Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, a former Karachi University lecturer.

Roughly after two weeks, President Mirza's relations with Pakistan Armed Forces deteriorated leading Army Commander General Ayub Khan relieving the president from his presidency and forcefully exiling President Mirza to United Kingdom. General Ayub Khan justified his actions after appearing on national radio declaring that: "the armed forces and the people demanded a clean break with the past...". Until 1962, the martial law continued while Field Marshal Ayub Khan purged a number of politicians and civil servants from the government and replaced them with military officers. Ayub called his regime a "revolution to clean up the mess of black marketing, (sic), and corruption.".

Presidential republic and economy

The martial law continued until 1962 when the government of Field Marshal Ayub Khan commissioned a constitutional bench under Chief Justice of Pakistan, Muhammad Shahabuddin, containing ten senior justices, each five from East Pakistan and five from West Pakistan. On 6 May 1961, the commission sent its draft to President Ayub Khan who thoroughly examined the draft with consulting with his cabinet. In January 1962, the cabinet finally approved the text of the new constitution, promulgated by President Ayub Khan on 1 March 1962 and finally came into effect on 8 June 1962. With the success of 1962 constitution, East Pakistan became a Presidential republic and abolished all parliamentary institutions in East Pakistan. The 1962 constitution had provided the presidential system for both provincial states (West Pakistan and East Pakistan) that each states were given autonomy to run their separate presidential provincial governments. The responsibilities and authority of the center and the provinces were clearly listed in the Constitution.

During the years between 1960 and 1965, the annual rate of growth of the gross domestic product per capita was 4.4% in the West Pakistan versus 2.6% in East Pakistan. Furthermore, Bengali politicians pushing for more autonomy stated that much of Pakistan's export earnings were generated in East Pakistan by the export of Bengali jute and tea. As late as 1960, approximately 70% of Pakistan's export earnings originated in the East Wing, although this percentage declined as international demand for jute dwindled. By the mid-1960s, East Pakistan was accounting for less than 60% of the nation's export earnings, and by the time of Bangladesh's independence in 1971, this percentage had dipped below 50%. This reality did not dissuade Mujib from demanding in 1966 that separate foreign exchange accounts be kept and that separate trade offices be opened overseas. By the mid-1960s, West Pakistan was benefiting from Ayub's "Decade of Progress," with its successful "green revolution" in wheat, and from the expansion of markets for West Pakistani textiles, while East Pakistan's standard of living remained at an abysmally low level. The Bengalis were also upset that West Pakistan, because it was the seat of government, was the major beneficiary of foreign aid.

Military government

With Ayub Khan ousted from office in 1969, Commander of the Pakistani Army, General Yahya Khan became the country's second ruling Chief Martial Law Administrator. Both Bhutto and Mujib strongly disliked General Khan, but patiently endured him and his government as he had promised to hold an election in 1970. During this time, strong nationalistic sentiments in East Pakistan were perceived by the Pakistani Armed Forces and the central military government. Therefore, Khan and his military government wanted to divert the nationalistic threats and violence against non-East Pakistanis. The Eastern Military High Command was under constant pressure from the Awami League, and requested an active duty officer to control the command under such extreme pressure. The high flag rank officers, junior officers and many high command officers from the Pakistan's Armed Forces were highly cautious about their appointment in East-Pakistan, and the assignment of governing East Pakistan and appointment of an officer was considered highly difficult for the Pakistan High Military Command.

Civil disobedience

East Pakistan's Armed Forces, under the military administrations of Major-General Muzaffaruddin and Lieutenant-General Sahabzada Yaqub Khan, used an excessive amount of show of military force to curb the uprising in the province. With such action, the situation became highly critical and civil control over the province slipped away from the government. On 24 March, dissatisfied with the performance of his generals, Yahya Khan removed General Muzaffaruddin and General Yaub Khan from office on 1 September 1969. The appointment of a military administrator was considered quite difficult and challenging with the crisis continually deteriorating. Vice-Admiral Syed Mohammad Ahsan, Chief of Naval Staff of Pakistan Navy, had previously served as political and military adviser of East Pakistan to former President Ayub Khan. Having such a strong background in administration, and being an expert on East Pakistan affairs, General Yahya Khan appointed Vice-Admiral Syed Mohammad Ahsan as Martial Law Administrator, with absolute authority in his command. He was relieved as Chief of Naval Staff, and received extension from the government. On 1 September Admiral Ahsan assumed the command of the Eastern Military High Command, and became a unified commander of Pakistan Armed Forces in East-Pakistan. Under his command, the Pakistani Armed Forces were removed from the cities and deployed along the border. The rate of violence in East Pakistan dropped, nearly coming to an end. Civil rule improved and stabilised in East Pakistan under Martial Law Administrator Admiral Ahsan's era. The next year, in 1970, it was in this charged atmosphere that parliamentary elections were held in the country in December 1970.

Position towards West-Pakistan

The tense diplomatic relations between East and West Pakistan reached a climax in 1970 when the Awami League, the largest East Pakistani political party, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, (Mujib), won a landslide victory in the national elections in East Pakistan. The party won 167 of the 169 seats allotted to East Pakistan, and thus a majority of the 300 seats in the Parliament. This gave the Awami League the constitutional right to form an absolute government. Khan invited Mujib to Rawalpindi to take the charge of the office, and negotiations took place between the military government and the Awami Party. Bhutto was shocked with the results, and threatened his Peoples Party's members if they attended the inaugural session at the National Assembly. Bhutto was famously heard saying "break the legs" of any member of his party who dared enter and attend the session. However, fearing East Pakistani separatism, Bhutto demanded Mujib to form a coalition government. After a secret meeting held in Larkana, Mujib agreed to give Bhutto the office of Presidency with Mujib as Prime Minister. General Yahya Khan and his military government were kept unaware of these developments and under pressure from his own military government, refused to allow Rahman to become the Prime Minister of Pakistan. This increased agitation for greater autonomy in East Pakistan. The Military Police arrested Mujib and Bhutto and placed them in Adiala Jail in Rawalpindi. The news spread like a fire in both East and West Pakistan, and the struggle for independence began in East Pakistan.

The senior high command officers in Pakistan Armed Forces, and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, began to pressure General Yahya Khan to take armed action against Mujib and his party. Bhutto later distanced himself from Yahya Khan after he was arrested by Military Police along with Mujib. Soon after the arrests, a high level meeting was chaired by Yahya Khan. During the meeting, high commanders of Pakistan Armed Forces unanimously recommended an armed and violent military action. East Pakistan's Martial Law Administrator Admiral Ahsan, unified commander of Eastern Military High Command (EMHC), and Air Marshal Mitty Masud, Commander of Eastern Air Force Command (EAFC), were the only officers to object to the plans. When it became obvious that a military action in East Pakistan was inevitable, Admiral Ahsan resigned from his position as Martial Law Administrator in protest, and immediately flew back to Karachi, West Pakistan. Disheartened and isolated, Admiral Ahsan took early retirement from the Navy and quietly settled in Karachi. Once Operation Searchlight and Operation Barisal commenced, Air Marshal Masud flew to West Pakistan, and unlike Admiral Ahsan, tried to stop the violence in East Pakistan. When he failed in his attempts to meet General Yahya Khan, Masud too resigned from his position as Commander of Eastern Air Command, and took retirement from Air Force.

Final years and war

Lieutenant-General Sahabzada Yaqub Khan was sent into East Pakistan in emergency, following a major blow of the resignation of Vice Admiral Ahsan. General Yaqub temporarily assumed the control of the province, as he was made the unified commander of Pakistan Armed Forces. General Yaqub mobilised the entire major forces in East Pakistan, and were re-deployed in East Pakistan.

On 26 March 1971, the day after the military crackdown on civilians in East Pakistan, Mujibur Rahman declared the independence of Bangladesh. All major Awami League leaders including elected leaders of National Assembly and Provincial Assembly fled to neighbouring India and an exile government was formed headed by Mujibur Rahman. While he was in Pakistan Prison, Syed Nazrul Islam was the acting President with Tazuddin Ahmed as the Prime Minister. The exile government took oath on 17 April 1971 at Mujib Nagar, within East Pakistan territory of Kustia district and formally formed the government. Colonel MOG Osmani was appointed the Commander in Chief of Liberation Forces and whole East Pakistan was divided into eleven sectors headed by eleven sector commanders. All sector commanders were Bengali officers from defected Pakistan Army. This started the Bangladesh Liberation War in which the freedom fighters, joined in December 1971 by 400,000 Indian soldiers, faced the Pakistani Armed Forces of 365,000 plus Paramilitary and collaborationist forces. An additional approximately 25,000 ill-equipped civilian volunteers and police forces also sided with the Pakistan Armed Forces. Bloody guerrilla warfare ensued in East Pakistan.

Dissolution of East Pakistan

The Pakistan Armed Forces were unable to counter such threats. Poorly trained and inexperienced in guerrilla tactics, Pakistan Armed Forces and their assets were successfully sabotaged by the Bangladesh Liberation Forces. On April 1971, Lieutenant-General Tikka Khan succeeded General Yaqub Khan as Commander of unified forces. General Tikka Khan led the massive violent and massacre campaigns in the region. He is held responsible for killing hundreds of thousands of Bengali people in East Pakistan, mostly civilians and unarmed peoples. For his role, General Tikka Khan gained the title as "Butcher of Bengal". General Khan faced an international reaction against Pakistan, and therefore, General Tikka was removed as Commander of Eastern front. He installed a civilian administration under Abdul Motaleb Malik on 31 August 1971, which proved to be ineffective. However, during the meeting, with no high officers willing to assume the command of East Pakistan, Lieutenant-General Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi volunteered for the command of East Pakistan. Inexperienced and the large magnitude of this assignment, the government sent Vice-Admiral Mohammad Shariff as second-in-command of General Niazi. Admiral Shariff served as the deputy unified commander of Pakistan Armed Forces in East Pakistan. However, General Niazi proved to be a failure and ineffective ruler. Therefore, General Niazi and Air Marshal Enamul Haque, Commander of Eastern Air Force Command (EAFC), failed to launch any operation in East Pakistan against Indian or its allies. Except Admiral Shariff who continued to press pressure on Indian Navy iuntil the end of the conflict. Admiral Shariff made it nearly impossible for Indian Navy to land its naval forces on the shores with his well effective plans . The Indian Navy was unable to access East Pakistan and the Pakistan Navy was still offering resistance. The Indian Army, therefore, from all three directions of the province, entered East Pakistan. The Indian Navy then decided to wait near the Bay of Bengal until the Army reached the shore.

The Indian Air Force dismantled the capability of Pakistan Air Force in East Pakistan. Air Marshal Enamul Haque, Commander of Eastern Air Force Command (EAFC), failed to offer any serious resistance to the actions of the Indian Air Force. For most part of the war, the IAF enjoyed complete dominance in the skies over East Pakistan.

Surrender of the Pakistan Armed Forces

On 16 December 1971, the Pakistan Armed Forces surrendered to the joint liberation forces of Mukti Bahini and the Indian army, headed by Lieutenant-General Jagjit Singh Arora, the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief (GOC-in-C) of the Eastern Command of the Indian Army. Lieutenant General AAK Niazi, the last unified commander of Pakistan Armed Forces's Eastern Military High Command, signed the Instrument of Surrender. Over 93,000 personnel, including Lt.General Niazi and Admiral Shariff, were taken as Prisoner of War.

On 16 December 1971, East Pakistan was liberated from Pakistan as the newly independent state of Bangladesh. The Eastern Military High Command, civilian institutions and paramilitary forces were disbanded. Bangladesh quickly gained recognition from most countries after the signing of the Shimla Agreement between India and Pakistan. Bangladesh joined the United Nations in 1974.

Foreign affairs

United States

Each side did what it had to do. Each acted on its own national interest which clashed for a brief moment...

— Henry Kissinger, 2012, [20]

East Pakistan had extremely hostile relations with the United States and the tendency of communism and Anti-American sentiment was greater in East-Pakistan, which highly benefited the Soviet Union in 1971.[21] In 1954, when the United States dispatched the Military Assistance Advisory Group for West Pakistan, the East Pakistan Parliament signed a statement, which denounced Pakistan's government for signing a military pact with the United States.[21] The United States also denied economic aide to East Pakistan and avoided providing training to East-Pakistan Army and the East Pakistan Rifles, but was managed by Pakistan itself.[21]

In 2012, former United States Secretary of State Henry Kissinger addressed the U.S. policy on East Pakistan, as "Gun boat diplomacy".[20] Talking to India Today on 18 March 2012— nearly 41 years of disintegration of East Pakistan, Kissinger reminisced and quoted that: "India and the former Soviet Union had made a near-alliance around this time..... It was in the national interest of the US to preserve West Pakistan....", Kissinger maintained.[20] Kissinger further noted that the preservation of West Pakistan was far more important for the United States than anything in the region. In a book, "War and Succession" Kissinger said:

There was no question of "Saving" East-Pakistan. The United States had recognised for months that (sic).... (succession) of East Pakistan was inevitable; (war)... was not necessary to accomplished. The U.S. strove to preserve (West) Pakistan as an independent state. Since, the U.S. had judged that India's real aim was to encompass its disintegration....

— Henry Kissinger, 1990, [22]

Soviet Union

East Pakistan had extremely friendly relations with the Soviet Union, although the Soviet government tried its best to keep East Pakistan intact with West Pakistan.[23] During the time of conflict, Soviet Union sympathised with East Pakistan and entered in the conflict when the Soviet Armed Forces ordered the Soviet Navy dispatched two groups of cruisers and destroyers and a nuclear submarine armed with nuclear missiles from Vladivostok.[24]

India

The Independence of East Pakistan as Bangladesh... was a national objective and interest of India during its time...

— Henry Kissinger, 2012, [25]

East Pakistan enjoyed a strong interaction, healthy relations and close cultural ties with Republic of India. During the time of independence, the Bengali Hindus did not migrate to India, only few colonies close to border re-located in India. Although the formation was orgnanised but East Pakistan did not take role in 1947 war and no pressure was applied in Eastern borders.[26] During the war theatre of 1965 indo-Pakistan war, East Pakistan government remained silenced and did not send any reinforcement troops to press any pressure on Eastern India.[26] The line of action was seen extremely hostile by West Pakistan and an impression against East Pakistan was built.[26]

India played a massive role in helping East Pakistan gain independence. India under Indira Gandhi fully supported the cause of the East Pakistanis and its troops and equipment were used to fight the Pakistani forces. The Indian Army also gave full support to the main Bangladeshi guerrilla force, the Mukti Bahini. Finally, on 26 March 1971, Bangladesh emerged as an independent state. Since then, there have been several issues of agreement as well as of dispute.

Saudi Arabia

During the time of conflict, the Faisal of Saudi Arabia and Government of Saudi Arabia gave strong criticism to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his government for destabilising East Pakistan as well as the Pakistan.[27][28] Saudi Arabia did not welcome the secession of East Pakistan, and its communism was strongly opposed by the King Faisal who had strong anti-Communism views.[27]

China

Due to close interaction with Soviet Union and India, China also remained hostile towards East Pakistan, and criticised East-Pakistan's Sheikh Mujibur Rahman for causing the disturbance in Pakistan and refused to diplomatically recognise the succession of East Pakistan.[27]

Military

Since its unification with Pakistan, the East Pakistan Army had consisted of only one infantry brigade, which was made up of two battalions, the 1st East Bengal Regiment and the 1/14 or 3/8 Punjab Regiment in 1948. These two battalions boasted only five rifle companies between them (an infantry battalion normally had 5 companies).[29] This weak brigade, under the command of Brigadier-General Ayub Khan (local rank Major-General – GOC of 14th Army Division), together with the East Pakistan Rifles which was tasked with defending East Pakistan during the Kashmir War of 1947.[30] The PAF, Marines, and the Navy had little presence in the region. Only one PAF combatant squadron, No. 14 Squadron Tail Choppers, was active in East Pakistan. This combatant squadron was commanded by an air force Major PQ Mehdi (later four-star general). The East Pakistan military personnel were trained in combat diving, demolitions, and guerrilla/anti-guerrilla tactics by the advisers from the Special Service Group (Navy) who were also charged with intelligence data collection and management cycle.

The East Pakistan Navy had only one active-duty combatant destroyer, the PNS Sylhet; one submarine Ghazi (which was repeatedly deployed in West); four gunboats, inadequate to function in deep water. The joint special operations were managed and undertaken by the Naval Special Service Group (SSG(N)) who were assisted by the army, air force and marines unit. The entire service, the Marines were deployed in East Pakistan, initially tasked with conducting exercises and combat operations in riverine areas and at near shoreline. The small directorate of Naval Intelligence (while the headquarters and personnel, facilities, and directions were coordinated by West) had vital role in directing special and reconnaissance missions, and intelligence gathering, also was charged with taking reasonable actions to slow down the Indian threat. The armed forces of East Pakistan also consisted the paramilitary organisation, the Volunteers from the intelligence unit of the ISI's Covert Action Division (CAD). All of these armed forces were commanded by the unified command structure, the Eastern Military High Command, led by an officer of three-star rank equivalent.

Governors

| Tenure | Governor of East Pakistan[1] | Political Affiliation |

|---|---|---|

| 14 October 1955 – March 1956 | Amiruddin Ahmad | Muslim League |

| March 1956 – 13 April 1958 | A. K. Fazlul Huq | Muslim League |

| 13 April 1958 – 3 May 1958 | Hamid Ali (acting) | Awami League |

| 3 May 1958 – 10 October 1958 | Sultanuddin Ahmad | Awami League |

| 10 October 1958 – 11 April 1960 | Zakir Husain | Muslim League |

| 11 April 1960 – 11 May 1962 | Lieutenant-General Azam Khan, PA | Military Administration |

| 11 May 1962 – 25 October 1962 | Ghulam Faruque | Independent |

| 25 October 1962 – 23 March 1969 | Abdul Monem Khan | Civil Administration |

| 23 March 1969 – 25 March 1969 | Mirza Nurul Huda | Civil Administration |

| 25 March 1969 – 23 August 1969 | Major-General Muzaffaruddin,[31] PA | Military Administration |

| 23 August 1969 – 1 September 1969 | Lieutenant-General Sahabzada Yaqub Khan, PA | Military Administration |

| 1 September 1969 – 7 March 1971 | Vice-Admiral Syed Mohammad Ahsan, PN | Military Administration |

| 7 March 1971 – April 1971 | Lieutenant-General Sahabzada Yaqub Khan, PA | Military Administration |

| April 1971 – 31 August 1971 | Lieutenant-General Tikka Khan, PA | Military Administration |

| 31 August 1971 – 14 December 1971 | Abdul Motaleb Malik | Independent |

| 14 December 1971 – 16 December 1971 | Lieutenant-General Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi, PA | Military Administration |

| 16 December 1971 | Province of East Pakistan dissolved |

Chief Ministers

| Tenure | Chief Minister of East Pakistan[1] | Political Party |

|---|---|---|

| August 1955 – September 1956 | Abu Hussain Sarkar | Shramik Krishak Samajbadi Dal |

| September 1956 – March 1958 | Ata-ur-Rahman Khan | Awami League |

| March 1958 | Abu Hussain Sarkar | Shramik Krishak Samajbadi Dal |

| March 1958 – 18 June 1958 | Ata-ur-Rahman Khan | Awami League |

| 18 June 1958 – 22 June 1958 | Abu Hussain Sarkar | Shramik Krishak Samajbadi Dal |

| 22 June 1958 – 25 August 1958 | Governor's Rule | |

| 25 August 1958 – 7 October 1958 | Ata-ur-Rahman Khan | Awami League |

| 7 October 1958 | Post abolished | |

| 16 December 1971 | Province of East Pakistan dissolved |

Provincial Symbols

The main four provincial icons were the Oriental Magpie-Robin, Royal Bengal Tiger, Banyan tree and the Water Lily, all of these were nationalized by Bangladesh in 1972.

-

Provincial bird of East Pakistan, Oriental Magpie-Robin

-

Provincial Animal, Royal Bengal Tiger

-

Provincial Tree, Banyan

-

Provincial flower, Water Lily

Memorials and Legacy

The trauma was extremely severe in Pakistan when the news of secession of East Pakistan as Bangladesh arrived — a psychological setback,[32] complete and humiliating defeat that shattered the prestige of Pakistan Armed Forces.[32][33][34] The governor and martial law administrator Lieutenant-General Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi was defamed, his image was maligned and he was stripped of his honors.[32] The people of Pakistan could not come to terms with the magnitude of defeat, and spontaneous demonstrations and mass protests erupted on the streets of major cities in (West) Pakistan.[32] General Yahya Khan surrendered powers to Nurul Amin of Pakistan Muslim League, the first and last Vice-President and Prime minister of Pakistan.[32]

Prime minister Amin invited Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (sworn as President, later Prime minister) and the Pakistan Peoples Party to take control of Pakistan, and in a color ceremony where Bhutto addressed his daring speech to his nation via national television.[32] At this ceremony, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto waved his fist in the air and pledged to his nation to never again allow the surrender of his country like it happened with East Pakistan; therefore, he launched and orchestrated the large-scale atomic bomb project in 1972.[35] In memorial of East Pakistan, the East-Pakistan diaspora in Pakistan established the East-Pakistan colony in Karachi, Sindh.[36] In accordance, the East-Pakistani diaspora also composed patriotic tributes to Pakistan after the war; songs such as Sohni Dharti (lit. Beautiful land) and "Jeevay, Jeevay Pakistan (lit. long-live, long-live Pakistan), were composed by Bengali singer Shahnaz Rahmatullah in 1970s and 1980s.

To Western observers, the loss of East Pakistan was a blessing[35]— but it was a trauma that was not seen as such; even today it is still not seen that way.[35] In a book, "Scoop! Inside Stories from the Partition to the Present", written by Pakistan-born Indian politician Kuldip Nayar, it is noted that "Losing East Pakistan and Bhutto's releasing of Mujib did not mean anything to Pakistan's policy - as if there was no liberation war.[37] Bhutto's policy, and even today, the policy of Pakistan continues to state that "she will continue to fight for the honor and integrity of Pakistan. East Pakistan is an inseparable and inseverable part of Pakistan".[37]

See also

- Stranded Pakistanis

- Dominion of Pakistan

- West Pakistan

- East Bengal

- Pakistan Movement

- Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

- The Blood telegram

- List of East Pakistan first-class cricketers

References

- ^ a b c d Ben Cahoon, WorldStatesmen.org. "Bangladesh". Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ^ Story of Pakistan Press. "Partition of Bengal [1905–1911]". Story of Pakistan (Bengali Partition Part I). Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Story of Pakistan Press Release. "Partition of Bengal [1905–1911]". Partition of Bengal [1905–1911, Part II]. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ a b "The June 3rd Plan [1947]". Directorate of the Story of Pakistan. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Rahman, Syedur (2010). Historical Dictionary of Bangladesh. USA: Rowman and Littlefield Publishing Group. p. 300. ISBN 978-08108-6766-6.

- ^ U.S. Government (1 June 2004). Pakistan, a country study. USA: U.S. Government. pp. 236pp. ISBN 9781419139949.

- ^ Ali, Tariq (April 2003). The Clash of Fundamentalisms: Crusades, Jihads and Modernity. United Kingdom: Verso Publishing Co. plc. pp. 181–237, 342pp. ISBN 1-85984-457-X.

- ^ Sop. "H. S. Suhrawardy Becomes Prime Minister [1956]". Story of Pakistan (1956 times). Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Trived, Rabindranath. "The Legacy of the plight of Hindus in Bangladesh". Original date: Sun, 2007-07-22 01:09 pm. Rabindranath Trived, Asian Tribune. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Jalil, Amar (7 January 2007). "United front against the Bengalis". Dawn Newspapers, 2007. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ a b Jalil, Amar (28 March 2004). "An unforgivable front". Dawn. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ a b SoPakistan. "Presidential Election (1965)". Presidential Election (1965). Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Asif Haroon Raja. "After East Pakistan, another global conspiracy in the offing in Balochistan". Asif Haroon Raja. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ Story of Pakistan. "Awami League's Six-Point Program". Story of Pakistan (Awami League's Six-Point Program). Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ a b Press Release. "General Elections 1970". Pakistan Parliamentary Elections, 1970. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Story of Pakistan. "Tragedy and Reconstruction:Separation of East Pakistan (Part III)". Separation of East Pakistan (Part III). Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ a b c Website Release. "Tragedy and Reconstruction (The Separation of East Pakistan [1971] )". The Separation of East Pakistan [1971] (Part IV). Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Nair, Bhaskaran (1990). Politics in East Pakistan. New Delhi, India: Northern Book Center. ISBN 9788185119793.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ali, Tariq (2002). The Clash of Fundamentalism. United Kingdom: New Left Book plc. p. 395. ISBN 1-85984-457-X.

- ^ a b c Star Online Report (18 March 2012). "US direly needed to preserve West Pakistan:". India Today Conclave. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ a b c Hamid Hussain. "Tale of a love affair that never was: United States-Pakistan Defence Relations". Hamid Hussain , Defence Journal of Pakistan. Hamid Hussain , Defence Journal of Pakistan. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ Richard Sisson, Leo E. Rose (1990). War and Succession. America, U.S.: University of California Press, Berkely. p. 335. ISBN 0-520-07665-6.

- ^ Budhraj, Vijay Singh. "Russia and East Pakistan". Asian Survey. JSTOR 2642797.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "1971 India Pakistan War: Role of Russia, China, America and Britain". The World Reporter. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ Joshi, Majon (18 March 2012). "An Agenda for the Asian Century". Daily Mail. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ a b c Cohen, Stephen Philip (2004). he Idea of Pakistan. U.S.: Brookings Institution Press. pp. 103 pp, 73–74pp. ISBN 0-8157-1502-1..

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ a b c Charles Kennedy, Craig Baxter (11 July 2006). "Governance and Politics in South Asia". Retrieved 11 July 2006.

- ^ Baxter, Craig (11 July 2006). "Bangladesh: From a Nation to a State". Retrieved 11 July 2006.

- ^ Major Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp49

- ^ Major Nasir Uddin, Juddhey Juddhey Swadhinata, pp47, pp51

- ^ (acting martial law administrator and governor as he was the GOC 14th Infantry Division)

- ^ a b c d e f Haqqani, Hussain (2005). Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military. United Book Press. ISBN 978-0-87003-214-1., Chapter 3, pp 87.

- ^ Burke, Samuel Martin (1974). Mainsprings of Indian and Pakistani Foreign Policies. University Of Minnesota Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-8166-5714-8.

- ^ Ali, Tariq (1997). Can Pakistan Survive? The Death of a State. Verso Books. ISBN 978-0-86091-949-0.

- ^ a b c Langewiesche, William (November 2005). "The Wrath of Khan". The Atlantic. William Langewiesche of The Atlantic. Retrieved August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Abbas Naqvi (17 December 2006). "Falling back". Daily Times. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

Few people in Karachi's Chittagong Colony can forget Dec 16, 1971 – the Fall of Dhaka...Daily Times.

- ^ a b Nayar, Kuldip (1 October 2006). Scoop! : Inside Stories from Partition to the Present. United Kingdom: HarperCollins. pp. 213 pages. ISBN 978-8172236434.

External links

- Use dmy dates from October 2012

- History of Pakistan

- States and territories established in 1955

- States and territories disestablished in 1971

- Former administrative units of Pakistan

- History of Bangladesh

- Bangladesh Liberation War

- East Pakistan

- Exclaves

- Communism in Pakistan

- Communist states

- Former republics

- Socialist states