Nirmatrelvir

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | PF-07321332 |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C23H32F3N5O4 |

| Molar mass | 499.535 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 192.9 °C (379.2 °F) [1] |

| |

| |

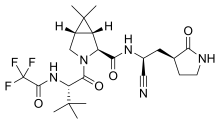

Nirmatrelvir is an antiviral drug developed by Pfizer which acts as an orally active 3CL protease inhibitor. The combination of nirmatrelvir with ritonavir was given Emergency Use Authorization by the FDA for the treatment of COVID-19 in high-risk adults under the brand name Paxlovid.[2][3][4][5][6]

Development

Pharmaceutical

Coronaviral proteases cleave multiple sites in the viral polyprotein, usually after glutamine residues. Early work on related human rhinoviruses showed that the flexible glutamine side chain could be replaced by a rigid pyrrolidone.[7][8] These drugs had been further developed prior to the SARS CoV2 pandemic for other diseases including SARS.[9] The utility of targeting the 3CL protease in a real world setting was first demonstrated in 2018 when GC376 (a prodrug of GC373) was used to treat the previously 100% lethal cat coronavirus disease, feline infectious peritonitis, caused by Feline coronavirus.[10]

The Pfizer drug is an analog of GC373, where the aldehyde covalent cysteine acceptor has been replaced by a nitrile.[11][12]

Nirmatrelvir was developed by modification of an earlier clinical candidate lufotrelvir,[13][14] which is also a covalent inhibitor but its warhead is a phosphate prodrug of a hydroxyketone. However, lufotrelvir needs to be administered intravenously limiting its use to a hospital setting. Stepwise modification of the tripeptide protein mimetic led to nirmatrelvir, which is suitable for oral administration.[1] Key changes include a reduction in the number of hydrogen bond donors, and the number of rotatable bonds by introducing the rigid bicyclic non-canonical amino acid, which mimics the leucine residue found in earlier inhibitors. This residue had previously been used in the synthesis of boceprevir.[15] The tert-leucine used in nirmatrelvir was identified as optimal using combinatorial chemistry.[16][17]

Clinical

In April 2021, Pfizer began phase I trials.[18] In September 2021, Pfizer began a phase II/III trial.[19] In November 2021, Pfizer announced 89% reduction in hospitalizations of high risk patients studied when given within three days after symptom onset.[20][21]

On 14 December 2021, Pfizer announced that the combination of nirmatrelvir with ritonavir, when given within three days of symptom onset, reduced the risk of hospitalization or death by 89% compared with placebo in 2,246 high-risk participants studied.[6]

Chemistry and pharmacology

Full details of the synthesis of nirmatrelvir were first published by scientists from Pfizer.

In the penultimate step, a synthetic homochiral amino acid is coupled with a homochiral amino amide using the water-soluble carbodiimide EDCI as coupling agent. The resulting intermediate is then treated with Burgess reagent, which dehydrates the amide group to the nitrile of the product.[1]

Nirmatrelvir is a covalent inhibitor, binding directly to the catalytic cysteine (Cys145) residue of the cysteine protease enzyme.[22]

In the drug combination, ritonavir serves to slow down metabolism of nirmatrelvir by cytochrome enzymes to maintain higher circulating concentrations of the main drug.[23]

Society and culture

The UK placed an order for 250,000 courses after Pfizer's press release in October 2021,[24][25] and Australia pre-ordered 500,000 courses of the drug.[26]

Legal status

In November 2021, Pfizer signed a license agreement with the United Nations–backed Medicines Patent Pool to allow nirmatrelvir to be manufactured and sold in 95 countries.[27] Pfizer stated that the agreement will allow local medicine manufacturers to produce the pill "with the goal of facilitating greater access to the global population". However, the deal excludes several countries with major COVID-19 outbreaks including Brazil, China, Russia, Argentina, and Thailand.[28][29]

On 16 November 2021, Pfizer submitted an application to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for emergency use authorization for nirmatrelvir in combination with ritonavir.[30][31][32]

Misleading comparison with ivermectin

The combination of nirmatrelvir with ritonavir is sometimes falsely claimed to be a "repackaged" version of the antiparasitic drug ivermectin, which has been questionably promoted as a COVID-19 therapeutic. Such claims, sometimes using the nickname "Pfizermectin",[33] rely on superficial similarities between the pharmacokinetics of both drugs and the claim that Pfizer is suppressing the benefits of ivermectin.[34]

References

- ^ a b c Owen DR, Allerton CM, Anderson AS, Aschenbrenner L, Avery M, Berritt S, et al. (November 2021). "An oral SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor clinical candidate for the treatment of COVID-19". Science: eabl4784. doi:10.1126/science.abl4784. PMID 34726479. S2CID 240422219.

- ^ Chutel, Lynsey (22 December 2021). "Covid Live Updates: New Cases Fall in South Africa's Omicron Surge". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Vandyck K, Deval J (August 2021). "Considerations for the discovery and development of 3-chymotrypsin-like cysteine protease inhibitors targeting SARS-CoV-2 infection". Current Opinion in Virology. 49: 36–40. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2021.04.006. PMC 8075814. PMID 34029993.

- ^ Şimşek-Yavuz S, Komsuoğlu Çelikyurt FI (August 2021). "Antiviral treatment of COVID-19: An update". Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences. doi:10.3906/sag-2106-250. PMID 34391321. S2CID 237054672.

- ^ Ahmad B, Batool M, Ain QU, Kim MS, Choi S (August 2021). "Exploring the Binding Mechanism of PF-07321332 SARS-CoV-2 Protease Inhibitor through Molecular Dynamics and Binding Free Energy Simulations". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (17): 9124. doi:10.3390/ijms22179124. PMC 8430524. PMID 34502033.

- ^ a b "Pfizer Announces Additional Phase 2/3 Study Results Confirming Robust Efficacy of Novel COVID-19 Oral Antiviral Treatment Candidate in Reducing Risk of Hospitalization or Death" (Press release). 14 December 2021.

- ^ Anand K, Ziebuhr J, Wadhwani P, Mesters JR, Hilgenfeld R (June 2003). "Coronavirus Main Proteinase (3CLpro) Structure: Basis for Design of Anti-SARS Drugs". Science. 300 (5626): 1763–1767. Bibcode:2003Sci...300.1763A. doi:10.1126/science.1085658. PMID 12746549. S2CID 13031405.

- ^ Dragovich PS, Prins TJ, Zhou R, Webber SE, Marakovits JT, Fuhrman SA, et al. (April 1999). "Structure-based design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of irreversible human rhinovirus 3C protease inhibitors. 4. Incorporation of P1 lactam moieties as L-glutamine replacements". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 42 (7): 1213–1224. doi:10.1021/jm9805384. PMID 10197965.

- ^ Pillaiyar T, Manickam M, Namasivayam V, Hayashi Y, Jung SH (July 2016). "An Overview of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) 3CL Protease Inhibitors: Peptidomimetics and Small Molecule Chemotherapy". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 59 (14): 6595–6628. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01461. PMC 7075650. PMID 26878082.

- ^ Pedersen NC, Kim Y, Liu H, Galasiti Kankanamalage AC, Eckstrand C, Groutas WC, et al. (April 2018). "Efficacy of a 3C-like protease inhibitor in treating various forms of acquired feline infectious peritonitis". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 20 (4): 378–392. doi:10.1177/1098612X17729626. PMC 5871025. PMID 28901812.

- ^ Halford B (7 April 2021). "Pfizer unveils its oral SARS-CoV-2 inhibitor". Chemical & Engineering News. 99 (13): 7. doi:10.47287/cen-09913-scicon3. S2CID 234887434.

- ^ Vuong W, Khan MB, Fischer C, Arutyunova E, Lamer T, Shields J, et al. (August 2020). "Feline coronavirus drug inhibits the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 and blocks virus replication". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 4282. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-18096-2. PMC 7453019. PMID 32855413.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT04535167 for "First-In-Human Study To Evaluate Safety, Tolerability, And Pharmacokinetics Following Single Ascending And Multiple Ascending Doses of PF-07304814 In Hospitalized Participants With COVID-19 " at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Boras B, Jones RM, Anson BJ, Arenson D, Aschenbrenner L, Bakowski MA, et al. (February 2021). "Discovery of a Novel Inhibitor of Coronavirus 3CL Protease for the Potential Treatment of COVID-19". bioRxiv: 2020.09.12.293498. doi:10.1101/2020.09.12.293498. PMC 7491518. PMID 32935104.

- ^ Njoroge FG, Chen KX, Shih NY, Piwinski JJ (January 2008). "Challenges in modern drug discovery: a case study of boceprevir, an HCV protease inhibitor for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection". Accounts of Chemical Research. 41 (1): 50–59. doi:10.1021/ar700109k. PMID 18193821. S2CID 2629035.

- ^ Poreba M, Salvesen GS, Drag M (October 2017). "Synthesis of a HyCoSuL peptide substrate library to dissect protease substrate specificity". Nature Protocols: 2189–2214. doi:10.1038/nprot.2017.091.

- ^ Rut W, Groborz K, Zhang L, Sun X, Zmudzinski M, Pawlik B, Wang X, Jochmans D, Neyts J, Młynarski W, Hilgenfeld R, Drag M (October 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 M pro inhibitors and activity-based probes for patient-sample imaging". Nature Chemical Biology. doi:10.1038/s41589-020-00689-z.

- ^ Nuki P (26 April 2021). "Pfizer is testing a pill that, if successful, could become first-ever home cure for COVID-19". National Post. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021.

- ^ "Pfizer begins dosing in Phase II/III trial of antiviral drug for Covid-19". Clinical Trials Arena. 2 September 2021.

- ^ "Pfizer's Novel COVID-19 Oral Antiviral Treatment Candidate Reduced Risk Of Hospitalization Or Death By 89% In Interim Analysis Of Phase 2/3 EPIC-HR Study" (Press release). Pfizer Inc. 5 November 2021.

- ^ Mahase E (November 2021). "Covid-19: Pfizer's paxlovid is 89% effective in patients at risk of serious illness, company reports". BMJ. 375: n2713. doi:10.1136/bmj.n2713. PMID 34750163. S2CID 243834203.

- ^ Pavan M, Bolcato G, Bassani D, Sturlese M, Moro S (December 2021). "Supervised Molecular Dynamics (SuMD) Insights into the mechanism of action of SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitor PF-07321332". J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 36 (1): 1646–1650. doi:10.1080/14756366.2021.1954919. PMC 8300928. PMID 34289752.

- ^ Woodley M (19 October 2021). "What is Australia's potential new COVID treatment?". The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). Retrieved 6 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Pfizer Covid pill 'can cut hospitalisations and deaths by nearly 90%'". The Guardian. 5 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Mahase E (October 2021). "Covid-19: UK stockpiles two unapproved antiviral drugs for treatment at home". BMJ. 375: n2602. doi:10.1136/bmj.n2602. PMID 34697079. S2CID 239770104.

- ^ "What are the two new COVID-19 treatments Australia has gained access to?". ABC News (Australia). 17 October 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ "Pfizer and The Medicines Patent Pool (MPP) Sign Licensing Agreement for COVID-19 Oral Antiviral Treatment Candidate to Expand Access in Low- and Middle-Income Countries" (Press release). Pfizer. 16 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021 – via Business Wire.

- ^ "Covid-19: Pfizer to allow developing nations to make its treatment pill". BBC News. 16 November 2021. Archived from the original on 16 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Pfizer Will Allow Its Covid Pill to Be Made and Sold Cheaply in Poor Countries". The New York Times. 16 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Pfizer Seeks Emergency Use Authorization for Novel COVID-19 Oral Antiviral Candidate" (Press release). Pfizer. 16 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021 – via Business Wire.

- ^ Kimball S (16 November 2021). "Pfizer submits FDA application for emergency approval of Covid treatment pill". CNBC. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Robbins R (5 November 2021). "Pfizer Says Its Antiviral Pill Is Highly Effective in Treating Covid". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ Bloom J (2 December 2021). "How Does Pfizer's Pavloxid Compare With Ivermectin?". American Council on Science and Health. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Gorski D (15 November 2021). "Pfizer's new COVID-19 protease inhibitor drug is not just 'repackaged ivermectin'". Science-Based Medicine.

External links

- "PF-07321332". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Early Data Suggest Pfizer Pill May Prevent Severe COVID-19". National Institutes of Health. 16 November 2021.