Burial of Jesus

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

The burial of Jesus refers to the entombment of the body of Jesus after his crucifixion before the eve of the sabbath. This event is described in the New Testament. According to the canonical gospel narratives, he was placed in a tomb by a councillor of the Sanhedrin named Joseph of Arimathea;[2] according to Acts 13:28–29, he was laid in a tomb by "the council as a whole".[3] In art, it is often called the Entombment of Christ.

Biblical accounts

The earliest reference to a burial of Jesus is in a letter of Paul. Writing to the Corinthians around the year AD 54,[4] he refers to the account he had received of the death and resurrection of Jesus ("and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures").[5]

The four canonical gospels, likely written between 66 and 95, conclude with an extended narrative of Jesus's arrest, trial, crucifixion, entombment, and resurrection.[6]: p.91 They narrate how, on the evening of the Crucifixion, Joseph of Arimathea asked Pilate for the body; after Pilate granted his request, he wrapped it in a linen cloth and laid it in a tomb. According to Acts 13:28–29, he was laid in a tomb by "the council as a whole".[3]

Modern scholarship emphasizes contrasting the gospel accounts, and finds the Mark portrayal more probable.[7][8]

Gospel of Mark

In the Gospel of Mark (the earliest of the canonical gospels), written around the years 66 and 72,[9][10] Joseph of Arimathea is a member of the Sanhedrin, which had condemned Jesus, who wishes to ensure that the corpse is buried in accordance with Jewish Law, according to which dead bodies could not be left exposed overnight. He puts the body in a new shroud and lays it in a tomb carved into the rock.[7] The Jewish historian Josephus, writing later in the century, described how the Jews regarded this law as so important that even the bodies of crucified criminals would be taken down and buried before sunset.[11] In this account, Joseph does only the bare minimum to observe the Law, wrapping the body in a cloth, with no mention of washing (Taharah) or anointing it. This may explain why Mark mentions an event prior to the crucifixion in which a woman pours perfume over Jesus.[12] Jesus is thereby prepared for burial even before his actual death.[13]

Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew was written around the years 80 to 85, using the Gospel of Mark as a source.[14] In this account Joseph of Arimathea is not referenced as a member of the Sanhedrin, but a wealthy disciple of Jesus.[15][16] Many interpreters have read this as a subtle orientation by the author towards wealthy supporters,[16] while others believe this is a fulfillment of prophecy from Isaiah 53:9:

"And they made his grave with the wicked, And with the rich his tomb; Although he had done no violence, Neither was any deceit in his mouth."

This version suggests a more honourable burial: Joseph wraps the body in a clean shroud and places it in his own tomb, and the word used is soma (body) rather than ptoma (corpse).[17] The author adds that the Roman authorities "made the tomb secure by putting a seal on the stone and posting the guard."

Gospel of Luke

The Gospel of Mark is also a source for the account given in the Gospel of Luke, written around the year 90–95.[18] As in the Markan version, Joseph is described as a member of the Sanhedrin,[19] but as not having agreed with the Sanhedrin's decision regarding Jesus; he is said to have been "waiting for the kingdom of God" rather than a disciple of Jesus.[20]

Gospel of John

The Gospel of John, the last of the gospels, was written around the years 80 to 90, and it depicts Joseph as a disciple who gives Jesus an honourable burial. John says that Joseph was assisted in the burial process by Nicodemus, who brought a mixture of myrrh and aloes and included these spices in the burial cloth according to Jewish customs.[21]

Comparison

The comparison below is based on the New International Version.

| Paul | Mark | Matthew | Luke | John | Acts | | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joseph and Pilate | Mark 15:42–45

|

Matthew 27:57–58

|

Luke 23:50–52

|

John 19:38

|

Acts 13:29

| |

| Burial | 1 Corinthians 15:4

|

Mark 15:46–47

|

Matthew 27:59–61

|

Luke 23:53–56

|

John 19:39–42

|

Acts 13:29

|

| High priests and Pilate | Matthew 27:62–66

|

|||||

| Mary(s) | Mark 16:1–2

|

Matthew 28:1

|

Luke 24:1

|

John 20:1

|

In non-canonical literature

The apocryphal manuscript known as the Gospel of Peter states that the Jews handed over the body of Jesus to Joseph, who later washes him then buries him in a place called "Joseph's Garden".[24]

Historicity

Scholars differ on the historicity of the burial story, and the question if Jesus received a decent burial. Points of contention are if Jesus's body was taken off the cross before sunset, or left on the cross to decay; if his body was taken off the cross and buried specifically by Joseph of Arimathea, or by the Sanhedrin or a group of Jews in general; and if he was entombed, and if so, what kind of tomb, or if he was buried in a common grave.

An argument in favor of a decent burial before sunset is the Jewish custom, based on the Torah, that the body of an executed person should not remain on the tree where the corpse was hung for public display, but be buried before sunrise. This is based on Deuteronomy 21:22–23, but also attested in the Temple Scroll of the Essenes, and in Josephus' Jewish War 4.5.2§317, describing the burial of crucified Jewish insurgents before sunset.[25][26] Reference is also made to the Digesta, a Roman Law Code from the 6th century AD, which contains material from the 2nd century AD stating that "the bodies of those who have been punished are only buried when this has been requested and permission granted."[27][28] Burial of people who were executed by crucifixion is also attested by archaeological finds such as from Jehohanan, a body with a nail in the heel which could not be removed.[29][30]

Martin Hengel argued that Jesus was buried in disgrace as an executed criminal who died a shameful death,[31][32] a view which is "now widely accepted and has become entrenched in scholarly literature."[31] John Dominic Crossan argued that Jesus followers did not know what happened to the body.[33][note 1] According to Crossan, Joseph of Arimathea is "a total Markan creation in name, in place, and in function",[34][note 2] arguing that Jesus's followers inferred from Deut. 21:22-23 that Jesus was buried by a group of law-abiding Jews, as described in Acts 13:29. This story was adapted by Mark, turning the group of Jews into a specific person.[35] What really happened may be deduced from customary Roman practice, which was to leave the body on the stake, denying a honorable or family burial, famously stating that "the dogs were waiting."[36][37][note 3]

British New Testament scholar Maurice Casey also notes that "Jewish criminals were supposed to receive a shameful and dishonourable burial",[38] quoting Josephus:

The general situation was sufficient for Josephus to comment on the end of a biblical thief, 'And after being immediately put to death, he was given at night the dishonourable burial proper to the condemned' (Jos. Ant. V, 44). Somewhat similarly, he says of anyone who has been stoned to death for blaspheming God, 'let him be hung during the day, and let him be buried dishonourably and secretly (Jos. Ant. IV, 202).'[38]

Casey argues that Jesus was indeed buried by Joseph of Arimathea, but in a tomb for criminals owned by the Sanhedrin.[38] He therefore rejects the empty tomb narrative as legendary.[39]

New Testament historian Bart D. Ehrman also concludes that we don't know what happened to Jesus's body, but doubts that Jesus had a decent burial,[40] and finds it doubtful that Jesus was buried by Joseph of Arimathea specifically.[41] Ehrman notes that Acts 13 refers to the Sanhedrin as a whole putting Jesus's body in a tomb, not a single member.[3] According to Ehrman, the story may have been embellished and become more detailed, and "what was originally a vague statement that the unnamed Jewish leaders buried Jesus becomes a story of one leader in particular, who is named, doing so".[42][note 4] Ehrman gives three reasons for doubting a decent burial. He notes that "Sometimes Christian apologists argue that Jesus had to be taken off the cross before sunset on Friday because the next day was the Sabbath and it was against Jewish law, or at least Jewish sensitivities, to allow a person to remain on the cross during the Sabbath. Unfortunately, the historical record suggests just the opposite."[42] Referring to Hengel and Crossan, Ehrman argues that crucifixion was meant "to torture and humiliate a person as fully as possible", and the body was normally left on the stake to be eaten by animals.[44] Ehrman further argues that criminals were usually buried in common graves,[45] and Pilate had no concern for Jewish sensitivities, which makes it unlikely that he would have allowed for Jesus to be buried.[46]

A number of Christian authors have rejected the criticisms, taking the Gospel accounts to be historically reliable. John A.T. Robinson states that "the burial of Jesus in the tomb is one of the earliest and best-attested facts about Jesus".[47] Dale Allison, reviewing the arguments of Crossan and Ehrman, considers this assertion strong but "find[s] it likely that a man named Joseph, probably a Sanhedrist, from the obscure Arimathea, sought and obtained permission from the Roman authorities to make arrangements for Jesus’ hurried burial."[48] Raymond E. Brown, writing in 1973 before the publications of Hengel and Crossan, mentions that a number of authors have argued for a burial in a common grave, but Brown argues that the body of Jesus was buried in a new tomb by Joseph of Arimathea in accordance with Mosaic Law, which stated that a person hanged on a tree must not be allowed to remain there at night but should be buried before sundown.[49]

James Dunn dismisses the criticisms, stating that "the tradition is firm that Jesus was given a proper burial (Mark 15.42-47 pars.), and there are good reasons why its testimony should be respected".[30] Dunn argues that the burial tradition is "one of the oldest pieces of tradition we have", referring to 1 Cor. 15.4; burial was in line with Jewish custom as prescribed by Deut. 21.22-23 and confirmed by Josephus War; cases of burial of crucified persons are known, as attested by the Jehohanan burial; Joseph of Arimathea "is a very plausible historical character"; and "the presence of the women at the cross and their involvement in Jesus' burial can be attributed more plausibly to early oral memory than to creative story-telling".[50] N. T. Wright argues that the burial of Christ is part of the earliest gospel traditions.[51] Craig A. Evans refers to Deut. 21:22-23 and Josephus to argue that the entombment of Jesus accords with Jewish sensitivities and historical reality.[note 5] Evans also notes that "politically, too, it seems unlikely that, on the eve of Passover, a holiday that celebrates Israel's liberation from foreign domination, Pilate would have wanted to provoke the Jewish population" by denying Jesus a proper burial.[54]

According to religion professor John Granger Cook, there are historical texts that mention mass graves, but they contain no indication of those bodies being dug up by animals. There is no mention of an open pit or shallow graves in any Roman text. There are a number of historical texts outside the gospels showing the bodies of the crucified dead were buried by family or friends. Cook writes that "those texts show that the narrative of Joseph of Arimethaea's burial of Jesus would be perfectly comprehensible to a Greco-Roman reader of the gospels and historically credible." Cook notes that numerous early critics of Christianity such Celsus, Porphyry, Hierocles, Julian, and Macarius’s anonymous pagan philosopher, accepted the historicity of the burial but rejected the resurrection.[55]

Theological significance

Paul the Apostle includes the burial in his statement of the gospel in verses 3 and 4[broken anchor] of 1 Corinthians 15: "For I delivered unto you first of all that which I also received, how that Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures; And that he was buried, and that he rose again the third day according to the scriptures" (KJV). This appears to be an early pre-Pauline credal statement.[56]

The burial of Christ is specifically mentioned in the Apostles' Creed, where it says that Jesus was "crucified, dead, and buried." The Heidelberg Catechism asks "Why was he buried?" and gives the answer "His burial testified that He had really died."[57]

The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that, "It is the mystery of Holy Saturday, when Christ, lying in the tomb, reveals God's great sabbath rest after the fulfillment of man's salvation, which brings peace to the whole universe" and that "Christ's stay in the tomb constitutes the real link between his passible state before Easter and his glorious and risen state today."[58]

Depiction in art

| Part of a series on |

| Death and Resurrection of Jesus |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

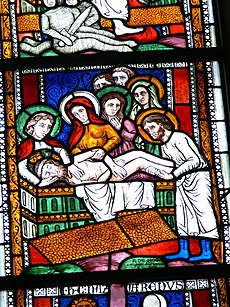

The Entombment of Christ has been a popular subject in art, being developed in Western Europe in the 10th century. It appears in cycles of the Life of Christ, where it follows the Deposition of Christ or the Lamentation of Christ. Since the Renaissance, it has sometimes been combined or conflated with one of these.[59]

Notable individual works with articles include:

- The Entombment (Bouts, c. 1450s)

- Lamentation of Christ (Rogier van der Weyden, c. 1460–1463)

- The Entombment (Michelangelo, c. 1500–01)

- The Deposition (Raphael, 1507)

- The Entombment (Titian, 1525)

- The Entombment (Titian, 1559)

- The Entombment of Christ (Caravaggio, 1603–04)

- Veiled Christ (Sanmartino, 1753)

Use in hymnody

The African-American spiritual "Were You There?" has the line "Were you there when they laid Him in the tomb?"[60] while the Christmas carol "We Three Kings" includes the verse:

Myrrh is mine, its bitter perfume

Breathes a life of gathering gloom;

Sorrowing, sighing, bleeding, dying,

Sealed in the stone cold tomb.

John Wilbur Chapman's hymn "One Day" interprets the burial of Christ by saying "Buried, He carried my sins far away."[61]

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the following troparion is sung on Holy Saturday:

The noble Joseph,

when he had taken down Thy most pure body from the tree,

wrapped it in fine linen and anointed it with spices,

and placed it in a new tomb.

Artistic depictions

-

Entombment of Christ, 15th century, Belgium

-

Henry Augustin Valentin after Hans Holbein the Younger, Iesvs Nazarenevs Rex Ivdaeorvm, 19th century, etching, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC

-

1863 "Santo Entierro" (2024 Good Friday processions)

See also

- Tomb of Jesus, multiple sites purported to be Christ's burial place

- Descent from the Cross

- Empty tomb

- Epitaphios (liturgy)

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- Harrowing of Hell

Notes

- ^ Allison refers to "Crossan, Historical Jesus, 391–4; idem, Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1994), 123–58; idem, Who Killed Jesus? Exposing the Roots of Anti-Semitism in the Gospel Story of the Death of Jesus (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1996), 160–77))"

- ^ Allison refers to Crossan (1996), Who Killed Jesus?

- ^ According to Allison (2021, p. 95), "The position [on Joseph of Arimathea] is an old one; see Gustav Volkmar, Die Religion Jesu und ihre erste Entwichelung nach dem gegenwärtigen Stande der Wissenschaft (Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 1857), 257–9; Alfred Loisy, Les éangiles synoptiques, 2 vols. (Ceffonds: Loisy, 1907), 1:223–4; idem, The Birth of the Christian Religion (London: G. Allen & Unwin, 1948), 90–1; Conybeare, Myth, Magic and Morals, 302; and Guignebert, Jesus, 500. More recent scholars who deem Joseph of Arimathea to be a fiction include F. W. Beare, The Gospel according to Matthew: A Commentary (Oxford: Blackwell, 1981), 538; Randel Helms, Gospel Fictions (Buffalo, NY: Prometheus, 1988), 134–6; Marianne Sawicki, Seeing the Lord: Resurrection and Early Christian Practices (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1994), 257; Robert Funk, Honest to Jesus (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1996), 228 (“Joseph of Arimathea is probably a Markan creation”); Funk and the Jesus Seminar, The Acts of Jesus, 159; Keith Parsons, “Peter Kreeft and Ronald Tacelli on the Hallucination Theory,” in The Empty Tomb: Jesus Beyond the Grave, ed. Robert M. Price and Jeffery Jay Lowder (Amherst, NY: Prometheus, 2005), 445–7; Michael J. Cook, Modern Jews Engage the New Testament: Enhancing Jewish Well-Being in a Christian Environment (Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights, 2008), 149–57; and Martin, Biblical Truths, 211.

- ^ In From Jesus to Constantine: A History of Early Christianity, Lecture 4: "Oral and Written Traditions about Jesus" (2003), Ehrman recognized that "Some scholars have argued that it's more plausible that in fact Jesus was placed in a common burial plot, which sometimes happened, or was, as many other crucified people, simply left to be eaten by scavenging animals," but further elaborated that "[T]he accounts are fairly unanimous in saying [...] that Jesus was in fact buried by this fellow, Joseph of Arimathea, and so it's relatively reliable that that's what happened."[43]

- ^ Evans (2005) refers to Crossan in "Jewish Burial Traditions and the Resurrection of Jesus," arguing that "The burial of Jesus, according to Jewish tradition, is almost certain for at least two reasons: (1) strong Jewish concerns that the dead — righteous or unrighteous — be properly buried; and (2) desire to avoid defilement of the land."

Evans refers to archaeologist Jodi Magness, who questions Hengel's and Crossan's views, arguing that the Gospel accounts describing Jesus's removal from the cross and burial accord well with archaeological evidence and with Jewish law, which prescribed that the death should be buried (or entombed) immediately.[52] Magness in turn refers frequently to Roll Back the stone (2003) by archaeologist Byron McCane. McCane also argues that it was customary to depose of the dead immediately, yet concludes that "Jesus was buried in disgrace in a criminal's tomb.[53]

References

- ^ "The Entombment of Christ (1601-3) by Caravaggio". Encyclopaedia of Arts Education. Visual Arts Cork. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ Kaitholil. com, Inside the church of the holy sepulchre in Jerusalem, archived from the original on 2019-08-19, retrieved 2018-12-28

- ^ a b c Ehrman (2014), p. 83.

- ^ Watson E. Mills, Acts and Pauline Writings, Mercer University Press 1997, page 175.

- ^ 1COR 15:3–4

- ^ Powell, Mark A. Introducing the New Testament. Baker Academic, 2009. ISBN 978-0-8010-2868-7

- ^ a b Douglas R. A. Hare, Mark (Westminster John Knox Press, 1996) page 220.

- ^ Maurice Casey, Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching (Continuum, 2010) page 449.

- ^ Witherington (2001), p. 31: 'from 66 to 70, and probably closer to the latter'

- ^ Hooker (1991), p. 8: 'the Gospel is usually dated between AD 65 and 75.'

- ^ James F. McGrath, "Burial of Jesus. II. Christianity. B. Modern Europe and America" in The Encyclopedia of the Bible and Its Reception. Vol.4, ed. by Dale C. Allison Jr., Volker Leppin, Choon-Leong Seow, Hermann Spieckermann, Barry Dov Walfish, and Eric Ziolkowski, (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2012), p. 923

- ^ (Mark 14:3–9)

- ^ McGrath, 2012, p.937

- ^ Harrington (1991), p. 8.

- ^ Daniel J. Harrington, The Gospel of Matthew (Liturgical Press, 1991) page 406.

- ^ a b Donald Senior, The Passion of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew (Liturgical Press, 1990) page 151.

- ^ Donald Senior, The Passion of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew (Liturgical Press, 1990) page 151-2.

- ^ Davies (2004), p. xii.

- ^ N. T. Wright, Luke For Everyone (Westminster John Knox Press), page 286.

- ^ Luke 23:50–55

- ^ John 19:39–42

- ^ It's not clear whether 'the Council' (τῇ βουλῇ) refers to the Sanhedrin (τὸ συνέδριον, Luke 22:66), but it's likely.

- ^ a b Going by Matthew 27:56, this was Mary, the mother of James and Joseph.

- ^ Walter Richard (1894). The Gospel According to Peter: A Study. Longmans, Green. p. 8. Retrieved 2022-04-02.

- ^ Dijkhuizen (2011), p. 119-120.

- ^ Dunn (2003b), p. 782.

- ^ Evans (2005), p. 195.

- ^ Allison (2021), p. 104.

- ^ Magness (2005), p. 144.

- ^ a b Dunn (2003b), p. 781.

- ^ a b Magness (2005), p. 141.

- ^ Hengel (1977).

- ^ Allison (2021), p. 94.

- ^ Allison (2021), p. 94, note 4.

- ^ Allison (2021), p. 94-95.

- ^ Allison (2021), p. 95.

- ^ Crossan (2009), p. 143.

- ^ a b c Casey (2010), p. 451.

- ^ Casey (2010).

- ^ Ehrman 2014, p. 82-88.

- ^ Ehrman 2014, p. 82.

- ^ a b Ehrman 2014, p. 84.

- ^ Bart Ehrman, From Jesus to Constantine: A History of Early Christianity, Lecture 4: "Oral and Written Traditions about Jesus" [The Teaching Company, 2003].

- ^ Ehrman 2014, p. 85.

- ^ Ehrman 2014, p. 86.

- ^ Ehrman 2014, p. 87.

- ^ Robinson, John A.T. (1973). The human face of God. Philadelphia: Westminster Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-664-20970-4.

- ^ Allison (2021), p. 112.

- ^ Brown 1973, p. 147.

- ^ Dunn (2003b), p. 781-783.

- ^ Wright, N. T. (2009). The Challenge of Easter. p. 22.

- ^ Magness (2005).

- ^ McCane (2003), p. 89.

- ^ Evans, Craig (2005). "Jewish Burial Traditions and the resurrection of Jesus".

- ^ Cook, John Granger (April 2011). "Crucifixion and Burial". New Testament Studies. 57 (2): 193–213. doi:10.1017/S0028688510000214. S2CID 170517053.

- ^ Hans Conzelmann, 1 Corinthians, translated James W. Leitch (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1969), 251.

- ^ Heidelberg Catechism Archived 2016-10-17 at the Wayback Machine, Q & A 41.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 624-625 Archived December 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ G Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. II,1972 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, p.164 ff, ISBN 0-85331-324-5

- ^ "Cyberhymnal: "Were You There?"". Archived from the original on October 7, 2011.

- ^ "Cyberhymnal: One Day". Archived from the original on September 24, 2011.

Sources

- Allison, Dale C. Jr. (2021). The Resurrection of Jesus: Apologetics, Polemics, History. New York: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-5676-9757-8.

- Brown, R.E. (1973). The Virginal Conception and Bodily Resurrection of Jesus. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809117680.

- Bultmann, Rudolf (1968). The history of the synoptic tradition. Harper.

- Casey, Maurice (2010-12-30). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-567-64517-3.

- Crossan, John Dominic (2009). Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography.

- Davies, Stevan L. (2004). The Gospel of Thomas and Christian Wisdom. Bardic Press. ISBN 9780974566740.

- Dunn, James D.G. (2003b), Jesus Remembered: Christianity in the Making, Volume 1, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing

- Dijkhuizen, Petra (2011). "Buried Shamefully: Historical Reconstruction of Jesus' Burial and Tomb". Neotestamentica 45:1 (2011) 115-129.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2014-03-25). How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-225219-7.

- Evans, Craig (2005). "Jewish Burial Traditions and the resurrection of jesus". JSHJ 3.2 (2005).

- Harrington, Daniel J. (1991). The Gospel of Matthew. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814658031.

- Hengel, Martin (1977). Crucifixion in the Ancient World and the Folly of the Message of the Cross. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-1268-9.

- Hooker, Morna (1991). The Gospel According to Saint Mark. Continuum. ISBN 9780826460394.

- Magness, Jodi (2005). "Ossuaries and the Burials of Jesus and James". Journal of Biblical Literature. 124 (1): 121–154. doi:10.2307/30040993. ISSN 0021-9231. JSTOR 30040993.

- McCane, Byron (2003). Roll Back the Stone: Death and Burial in the World of Jesus. A&C Black.

- Witherington, Ben (2001). The Gospel of Mark: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802845030.