Pope Gregory I

Pope Gregory I | |

|---|---|

| |

| Installed | September 3, 590 |

| Term ended | March 12, 604 |

| Predecessor | Pelagius II |

| Successor | Sabinian |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Gregorius c. 540 |

| Died | March 12, 604 |

| Buried | Cappella Clementina, St. Peter's Basilica, since 1606 |

| Nationality | Roman |

| Parents | Gordianus, Saint Silvia |

| Other popes named Gregory | |

Saint Gregory I the Great or Pope Saint Gregory I (c. 540 – March 12, 604) was pope from September 3, 590 until his death.

He is also known as Gregory the Dialogist (Gregorios Dialogos) in Eastern Orthodoxy because of the Dialogues he wrote. For this reason, English translations of Orthodox texts will sometimes list him as "Gregory Dialogus". He was the first of the Popes from a monastic background. Gregory is a Doctor of the Church and one of the four great Latin Fathers of the Church (the others being Ambrose, Augustine, and Jerome). Of all popes, Gregory I had the most influence on the early medieval church.[1]

Immediately after his death, Gregory was canonized by popular acclaim.[2] He is seen as a patron of England.[3]

Biography

Early life

The exact date of St. Gregory's birth is uncertain, but is usually estimated to be around the year 540. He was born into a wealthy noble Roman family, in a period, however, when the city of Rome was facing a serious decline in population, wealth, and influence. His family seems to have been devout. Gregory's great-great-grandfather had been Pope Felix III. Gregory's father, Gordianus, worked for the Roman Church and his father's three sisters were nuns. Gregory's mother Silvia herself is a saint. While his father lived, Gregory took part in Roman political life and at one point was Prefect of the City. However, on his father's death, he converted his family villa suburbana, located on the Caelian Hill just opposite the Circus Maximus, into a monastery dedicated to the apostle Saint Andrew. Gregory himself entered as a monk. After his death it was rededicated as San Gregorio Magno al Celio.

Eventually, Pope Pelagius II ordained him a deacon and solicited his help in trying to heal the schism of the Three Chapters in northern Italy. In 579, Pelagius II chose Gregory as his apocrisiarius or ambassador to the imperial court in Constantinople.

Controversy with Eutychius

In Constantinople, Gregory first gained attention by starting a controversy with Patriarch Eutychius of Constantinople, who had published a treatise on the corporeality of the imminent General Resurrection, in which bodies would be incorporeal, to which Gregory contrasted the corporeality of the risen Christ. The heat of argument drew the Roman emperor in as judge. Eutychius' treatise was condemned, and it suffered the normal fate of all heterodox texts, of being publicly burnt. On his return to Rome, Gregory served as secretary to Pelagius II, and was elected Pope to succeed him.

Gregory as Pope

| Papal styles of Pope Gregory I | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | Saint |

When he became Pope in 590, among his first acts were writing a series of letters disavowing any ambition to the throne of Peter and praising the contemplative life of the monks. At that time the Holy See had not exerted effective leadership in the West since the pontificate of Gelasius I. The episcopacy in Gaul was drawn from the great territorial families, and identified with them: the parochial horizon of Gregory's contemporary, Gregory of Tours, may be considered typical; in Visigothic Spain the bishops had little contact with Rome; in Italy the papacy was beset by the violent Lombard dukes and the rivalry of the Jews in the Exarchate of Ravenna and in the south. The scholarship and culture of Celtic Christianity had developed utterly unconnected with Rome, and it was from Ireland that Britain and Germany were likely to become Christianized, or so it seemed.

Gregory is credited with re-energizing the Church's missionary work among the barbarian peoples of northern Europe. He is most famous for sending a mission under Augustine of Canterbury to evangelize the pagan Anglo-Saxons of England. The mission was successful, and it was from England that missionaries later set out for the Netherlands and Germany.

Servus servorum Dei

In line with his predecessors such as Dionysius, Damasus, and St. Leo the Great, St. Gregory asserted the primacy of the office of the Bishop of Rome. Although he did not employ the term "Pope", he summed up the responsibilities of the papacy in his official appellation, as "servant of the servants of God". As Benedict of Nursia had justified the absolute authority of the abbot over the souls in his charge, so Gregory expressed the hieratic principle that he was responsible directly to God for his ministry.

St. Gregory's pontificate saw the development of the notion of private penance as parallel to the institution of public penance. He explicitly taught a doctrine of Purgatory where a soul destined to undergo purification after death because of certain sins, could begin its purification in this earthly life, through good works, obedience and Christian conduct, making the travails to come lighter and shorter.

St. Gregory's relations with the Emperor in the East were a cautious diplomatic stand-off. He concentrated his energies in the West, where many of his letters are concerned with the management of papal estates. His relations with the Merovingian kings, encapsulated in his deferential correspondence with Childebert II, laid the foundations for the papal alliance with the Franks that would transform the Germanic kingship into an agency for the Christianization of the heart of Europe — consequences that remained in the future.

More immediately, Gregory undertook the conversion of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, where inaction might have encouraged the Celtic missionaries already active in the north of Britain. Sending Augustine of Canterbury to convert the Kingdom of Kent was prepared by the marriage of the king to a Merovingian princess who had brought her chaplains with her. By the time of Gregory's death, the conversion of the king and the Kentish nobles and the establishment of a Christian toehold at Canterbury were established.

St. Gregory's chief acts as Pope include his long letter issued in the matter of the schism of the Three Chapters of the bishops of Venetia and Istria. He is also known in the East as a tireless worker for communication and understanding between East and West. He is also credited with increasing the power of the papacy.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, he was declared a saint immediately after his death by "popular acclamation".

Liturgical reforms

In letters, St. Gregory remarks that he moved the Pater Noster (Our Father) to immediately after the Roman Canon and immediately before the Fraction. This position is still maintained today in the Roman Liturgy. The pre-Gregorian position is evident in the Ambrosian Rite. Gregory added material to the Hanc Igitur of the Roman Canon and established the nine Kyries (a vestigial remnant of the litany which was originally at that place) at the beginning of Mass. He also reduced the role of deacons in the Roman Liturgy.

Sacramentaries directly influenced by Gregorian reforms are referred to as Sacrementaria Gregoriana. With the appearance of these sacramentaries, the Western liturgy begins to show a characteristic that distinguishes it from Eastern liturgical traditions. In contrast to the mostly invariable Eastern liturgical texts, Roman and other Western liturgies since this era have a number of prayers that change to reflect the feast or liturgical season; These variations are visible in the collects and prefaces as well as in the Roman Canon itself.

A system of writing down reminders of chant melodies was probably devised by monks around 800 to aid in unifying the church service throughout the Frankish empire. Charlemagne brought cantors from the Papal chapel in Rome to instruct his clerics in the “authentic” liturgy. A program of propaganda spread the idea that the chant used in Rome came directly from Gregory the Great, who had died two centuries earlier and was universally venerated. Pictures were made to depict the dove of the Holy Spirit perched on Gregory's shoulder, singing God's authentic form of chant into his ear. This gave rise to calling the music "Gregorian chant". A more accurate term is plainsong or plainchant.

Sometimes the establishment of the Gregorian Calendar is erroneously attributed to Gregory the Great; however, that calendar was actually instituted by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 by way of a papal bull entitled, Inter gravissimas.

Feast Day

The current Roman Catholic calendar of saints, revised in 1969 as instructed by the Second Vatican Council,[4] celebrates St. Gregory the Great on 3 September. The General Roman Calendar of 1962, whose use is permitted under the conditions indicated in the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum assigns his feast to 12 March. The reason why his feast was moved from the date of his death to that of his episcopal consecration was to transfer it outside of Lent, within which it would otherwise always fall, reducing his celebration in the Roman Rite to at most a mere commemoration.

The Eastern Orthodox Church and the associated Eastern Catholic Churches continue to commemorate St. Gregory on 12 March. The occurrence of this date during Great Lent is considered appropriate in the Byzantine Rite, which traditionally associates Saint Gregory with the Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts, celebrated only during that liturgical season.

Other Churches too honour Saint Gregory: the Church of England on 3 September, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and the Episcopal Church in the United States on 12 March.

A traditional procession is held in Żejtun, Malta in honour of Saint Gregory (San Girgor) on Easter Wednesday, which most often falls in April, the range of possible dates being 25 March to 28 April.

Works

Gregory is the only Pope between the fifth and the eleventh centuries whose correspondence and writings have survived enough to form a comprehensive corpus. "His character strikes us as an ambiguous and enigmatic one," Norman F. Cantor observed. "On the one hand he was an able and determined administrator, a skilled and clever diplomat, a leader of the greatest sophistication and vision; but on the other hand, he appears in his writings as a superstitious and credulous monk, hostile to learning, crudely limited as a theologian, and excessively devoted to saints, miracles, and relics".[5]

- Sermons (forty on the Gospels are recognized as authentic, twenty-two on Ezekiel, two on the Song of Songs)

- Dialogues, a collection of often fanciful narratives including a popular life of Saint Benedict

- Commentary on Job, frequently known even in English-language histories by its Latin title, Magna Moralia

- The Rule for Pastors, in which he contrasted the role of bishops as pastors of their flock with their position as nobles of the church: the definitive statement of the nature of the episcopal office

- Some 850 letters have survived from his Papal Register of letters, which serves as an invaluable primary source

- In the Eastern Orthodox Church, Gregory is credited with compiling the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts. This liturgy is celebrated on Wednesdays, Fridays, and certain other weekdays during Great Lent in the Eastern Orthodox Church and those Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite.

Sermon on Mary Magdalene

In a sermon whose text is given in Patrologia Latina, 76:1238‑1246, Gregory stated that he believed "that the woman Luke called a sinner and John called Mary was the Mary out of whom Mark declared that seven demons were cast" (Hanc vero quam Lucas peccatricem mulierem, Joannes Mariam nominat, illam else Mariam credimus de qua Marcus septem damonia ejecta fuisse testatur), thus identifying the sinner of Luke 7:37, the Mary of John 11:2 and 12:3 (the sister of Lazarus and Martha of Bethany), and Mary Magdalene, from whom Jesus had cast out seven demons (Mark 16:9).

While most Western writers shared this view, it was not seen as a Church teaching, but as an opinion, the pros and cons of which were discussed (see, for instance, the 1910 article on St. Mary Magdalen in The Catholic Encyclopedia). With the liturgical changes made in 1969, there is no longer mention of Mary Magdalene as a sinner in Roman Catholic liturgical materials.[6]

The Eastern Orthodox Church has never accepted Gregory's identification of Mary Magdalene with the sinful woman.

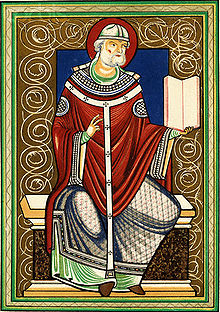

Iconography

In art Gregory is usually shown in full pontifical robes with the tiara and double cross, despite his actual habit of dress. Earlier depictions are more likely to show a monastic tonsure and plainer dress. Orthodox icons traditionally show St. Gregory vested as a bishop, holding a Gospel Book and blessing with his right hand. It is recorded that he permitted his depiction with a square halo, then used for the living. [7] A dove is his attribute, from the well-known story recorded by his friend Peter the Deacon,[8] who tells that when the pope was dictating his homilies on Ezechiel a curtain was drawn between his secretary and himself. As, however, the pope remained silent for long periods at a time, the servant made a hole in the curtain and, looking through, beheld a dove seated upon Gregory's head with its beak between his lips. When the dove withdrew its beak the pope spoke and the secretary took down his words; but when he became silent the servant again applied his eye to the hole and saw the dove had replaced its beak between his lips.[9]

This scene is shown as a version of the traditional Evangelist portrait (where the Evangelists' symbols are also sometimes shown dictating) from the tenth century onwards.[10] Usually the dove is shown whispering in Gregory's ear for a clearer composition.

The imaginative and anachronistic example at the top of this article is from the studio of Carlo Saraceni or by a close follower, ca 1610. From the Giustiniani collection, the painting is conserved in the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome [2].

Alms

Alms in Christianity is defined by passages of the New Testament such as Matthew 19:21, which commands "...go and sell that thou hast, and give to the poor ... and come and follow me." A donation on the other hand is a gift to some sort of enterprise, profit or non-profit.

On the one hand the the alms of St. Gregory are to be distinguished from his donations, but on the other he probably saw no such distinction. The church had no interest in secular profit and as pope Gregory did his utmost to encourage that high standard among church personnel. Apart from maintaining its facilities and supporting its personnel the church gave most of the donations it received as alms.

Gregory is known for his administrative system of charitable relief of the poor at Rome. They were predominantly refugees from the incursions of the Lombards. The philosophy under which he devised this system is that the wealth belonged to the poor and the church was only its steward. He received lavish donations from the wealthy families of Rome, who, following his own example, were eager to expiate to God for their sins. He gave alms equally as lavishly both individually and en masse. He wrote in letters:[11]

- "I have frequently charged you ... to act as my representative ... to relieve the poor in their distress ...."

- "... I hold the office of steward to the property of the poor ...."

Famous quotes and anecdotes

- Non Angli, sed Angeli - "They are not Angles, but Angels". Aphorism of unknown origin summarizing words reported to have been spoken by Gregory when he first encountered blue-eyed, blond-haired English boys at a slave market, sparking his dispatching of St. Augustine of Canterbury to England to convert the English, according to Bede.[12] He said: "Well named, for they have angelic faces and ought to be co-heirs with the angels in heaven."[13] Discovering that their province was Deira, he went on to add that they would be rescued de ira, "from the wrath", and that their king was named Aella, Alleluia, he said.[14]

- Ecce locusta - "Look at the locust." Gregory himself wanted to go to England as a missionary and started out for there. On the fourth day as they stopped for lunch a locust landed on the edge of the Bible Gregory was reading. He exclaimed ecce locusta, "look at the locust", but reflecting on it he saw it as a sign from Heaven since the similar sounding loco sta means "stay in place." Within the hour an emissary of the pope[15] arrived to recall him.[13]

- Pro cuius amore in eius eloquio nec mihi parco - "For the love of whom (God) I do not spare myself from his Word."[16] The sense is that since the creator of the human race and redeemer of him unworthy gave him the power of the tongue so that he could witness, what kind of a witness would he be if he did not use it but preferred to speak infirmly?

- Non enim pro locis res, sed pro bonis rebus loca amanda sunt - "Things are not to be loved for the sake of a place, but places are to be loved for the sake of their good things." When Augustine asked whether to use Roman or Gallican customs in the mass in England, Gregory said, in paraphrase, that it was not the place that imparted goodness but good things that graced the place, and it was more important to be pleasing to the Almighty. They should pick out what was "pia", "religiosa" and "recta" from any church whatever and set that down before the English minds as practice.[17]

Reception

In Britain, appreciation for Gregory remained strong even after his death, with him being called Gregorius noster ("our Gregory") by the British.[18] It was in Britain, at a monastery in Whitby, that the first full length life of Gregory was written, in c.713.[19] Appreciation of Gregory in Rome and Italy itself, however, did not come until later; in fact, his successor Sabinian rejected his charitable moves towards the poor of Rome. The first vita of Gregory written in Italy was not produced until John the Deacon in the 9th century.

References

- ^ Pope St. Gregory I at about.com

- ^ F.L. Cross, ed. (2005). "Gregory I". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Gregory the Great". Catholic Culture. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Sacrosanctum Concilium, 108-111

- ^ Cantor, 1993, p. 157 (see Bibliography, below).

- ^ Filteau, Jerry (2006), "Scholars seek to correct Christian tradition, fiction of Mary Magdalene", Catholic News Service http://www.catholic.org/national/national_story.php?id=19680, retrieved 2007-10-01

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Gietmann, G. (1911), "Nimbus", The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. XI, New York: Robert Appleton Company

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Peter the Deacon, Vita, xxviii

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia article - see links, below.

- ^ An early example is the dedication miniature from the an eleventh century manuscript of St. Gregory's Moralia in Job (Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, MS Msc. Bibl. 84). The miniature shows the scribe, Bebo of Seeon Abbey, presenting the manuscript to the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry II. In the upper left the author is seen writing the text under divine inspiration.[1]

- ^ Dudden, Frederick Homes (1905). Gregory the Great, His Place in History and Thought. Longmans, Green, and Co. pp. page 316.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Historia Ecclesiastica, II.i.

- ^ a b Hunt, William (1906). The Political History of England. Longmans, Green. pp. page 115.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ The earliest life written a generation earlier than Bede at Whitby relates the same story but in it the English are merely visitors to Rome questioned by Gregory (see Holloway, who translates from the manuscript kept at at Sangalliensis). The earlier story is not necessarily the more accurate, as Gregory is known to have bought English slaves in Rome for placement as monks

- ^ Benedict I or Pelagius II.

- ^ Homilies on Ezekiel Book 1.11.6. For the text in manuscript see Codices Electronici Sangalienses: Codex 211, page 193 column 1, line 5 (External links below.)

- ^ Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Book I section 27 part II. Bede is translated in Bede (1999). The Ecclesiastical History of the English People: The Greater Chronicle ; Bede's Letter to Egbert. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192838660, 9780192838667.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Champ, Judith (2000). The English Pilgrimage to Rome: A Dwelling for the Soul. pp. page ix. ISBN 0852443730, 9780852443736.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|publishe=ignored (help) - ^ A monk or nun at Whitby A.D. 713 (1997–2008). "The Earliest Life of St. Gregory the great" (html). Julia Bolton Holloway. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Bibliography

- Cantor, Norman F. (1993). The Civilization of the Middle Ages. New York: Harper.

- Cavadini, John, ed. (1995). Gregory the Great: A Symposium. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dudden, Frederick H. (1905). Gregory the Great. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Richards, Jeffrey (1980). Consul of God. London: Routelege & Keatland Paul.

- Straw, Carole E. (1988). Gregory the Great: Perfection in Imperfection. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Leyser, Conrad (2000). Authority and Asceticism from Augustine to Gregory the Great. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Markus, R.A. (1997). Gregory the Great and His World. Cambridge: University Press.

- Ricci, Cristina (2002). Mysterium dispensationis. Tracce di una teologia della storia in Gregorio Magno. Rome: Centro Studi S. Anselmo. Template:It icon. Studia Anselmiana, volume 135.

- Vincenzo Recchia, Lettera e profezia nell'esegesi di Gregorio Magno (Bari: Edipuglia, 2003), Pp. 157 (Quaderni di "Invigilata Lucernis," Dipartamento di Studi Classici e Cristiani, Universita\ degli Studi di Bari, vol. 20).

- George Demacopoulos, Five Models of Spiritual Direction in the Early Church (Notre Dame (IN), University of Notre Dame Press, 2007).

- Hester, Kevin L., Eschatology and Pain in St. Gregory the Great. The Christological Synthesis of Gregory's Morals on the Book of Job (Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2007), Pp. xv, 155 (Studies in Christian History and Thought).

External links

- "Documenta Catholica Omnia: Gregorius I Magnus" (html). Cooperatorum Veritatis Societas. 2006. Retrieved 2008-08-10. Template:La icon. Index of 70 downloadable .pdf files containing the texts of Gregory I.

- Gregory the Great (2007). "Homiliae in Ezechielem I-XXII". Codices Electronici Sangalienses: Codex 211 (in mediaeval Latin written in Carolingian minuscule). Stiftsbibliothek St.Gallen. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) Photographic images of a manuscript copied about 850-875 AD. - Huddleston, Gilbert (2008). "Pope St. Gregory I ('the Great')". In Kevin Knight (ed.). The Catholic Encyclopedia (1909 ed.). New Advent. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- Porvaznik, Phil (July 1995). "Pope Gregory the Great and the 'Universal Bishop' Controversy: Was the Pope denying his own Papal Authority?: Debunking a popular Protestant myth" (html). Apologetics Articles. Phil Porvaznik. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- "St Gregory Dialogus, the Pope of Rome" (html). Orthodox Church in America. Retrieved 2008-08-10. Orthodox icon and synaxarion.