Olympic Games

| Olympic Games | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ancient Olympic Games Summer Olympic Games Winter Olympic Games Paralympic Games Youth Olympic Games | |

| Charter • IOC • NOCs • Symbols Sports • Competitors Medal tables • Medalists | |

The Olympic Games are an international multi-sport event established for both summer and winter sports. There have been two generations of the Olympic Games; the first were the Ancient Olympic Games (Greek: Ολυμπιακοί Αγώνες; ) held at Olympia, Greece. The second, known as the Modern Olympic Games, were first revived in 1895 by the Greek philanthropist Evangelis Zappas, in Athens, Greece.

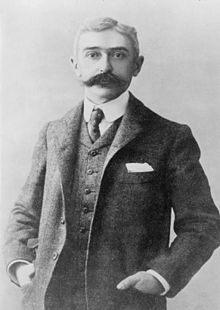

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) was founded in 1894 on the initiative of a French nobleman, Pierre Frédy, Baron de Coubertin, and has become the governing body of the Olympic Movement, a conglomeration of sporting federations responsible for the organization of the Games. The evolution of the Olympic Movement during the 20th century forced the IOC to adapt its own vision of the Games in several ways. The original ideal of a pure amateur athlete had to change under the pressure of corporate sponsorships and political regimes.

The modern Olympics feature the traditional Summer and the Winter Games, along with the more recent Paralympic and Youth Olympic Games, each with a summer and winter version. Participation in the Games has increased to the point that nearly every nation on Earth is represented. This growth has created numerous challenges, including political boycotts, the use of performance enhancing drugs, bribery of officials, and terrorism. The Games encompass many rituals and symbols established during its beginning, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Most of these traditions are displayed in the opening and closing ceremonies, and the medal presentations. Despite the current complexity of the Games, the focus remains on the Olympic motto, Citius, Altius, Fortius — "Faster, Higher, Stronger".

Ancient Olympics

There are many myths surrounding the origin of the ancient Olympic Games; the most popular identifies Heracles and his father Zeus as the progenitors of the Games.[1] According to the legend, Zeus held sporting events in honor of his defeat of Cronus and succession to the throne of heaven.[2] Heracles, his eldest son, defeated his brothers in a running race and was crowned with a wreath of wild olive branches.[3] It is Heracles who first called the Games "Olympic" and established the custom of holding them every four years.[1] One popular story claims that after Heracles completed his twelve labors, he went on to build the Olympic stadium and surrounding buildings as an honor to Zeus. After the stadium was complete, he walked in a straight line for 200 steps and called this distance a "stadion" (Greek: στάδιον, Latin: stadium, "stage"), which later became a unit of distance. Another myth associates the first Games with the ancient Greek concept of Olympic truce (ἐκεχειρία, ekecheiria). The most widely held estimate for the inception of the Ancient Olympics is 776 BC. Inscriptions have been found of the winners of a footrace held every four years starting in 776 BC with Koroebus, who became the first Olympic champion.[4] From then on, the Olympic Games quickly became important throughout ancient Greece. They reached their zenith in the 6th and 5th centuries BC. The Olympics were of fundamental religious importance, featuring sporting events alongside ritual sacrifices honoring both Zeus (whose colossal statue stood at Olympia) and Pelops, divine hero and mythical king of Olympia. Pelops was famous for his legendary chariot race with King Oenomaus of Pisatis.[5] The winners of the events were admired and immortalized in poems and statues.[6][7] The Games were held every four years, known as an Olympiad, and this period was used by Greeks as one of their units of time measurement. The Games were part of a cycle known as the Panhellenic Games, which included the Pythian Games, the Nemean Games, and the Isthmian Games.[8]

Gradually, though, the Games declined in importance as the Romans gained power and influence in Greece. There is conjecture that Roman emperor Theodosius I, in an attempt to re-assert Christianity as the official religion of the Empire, outlawed the Games in 393 AD due to its perceived links with paganism.[9][10] After the demise of the Olympics, they were not held again for another 1,500 years.

Modern Games

Forerunners and revival

Although the revival of the Olympic Games began in the mid-19th century, multi-sport events with titles such as "Olympick" or "Olympian" Games had been held as far back as the 16th century.[11] These events included an "Olympick Games" that convened for several years at Chipping Campden, in the English Cotswolds. The present day Cotswold Games trace their origin to this festival.[11] Another example of European attempts to emulate the Olympic Games was L'Olympiade de la République, an Olympic festival held annually, from 1796 to 1798, in Revolutionary France.[12] The competition included several disciplines from the ancient Greek Olympics. The 1796 Games also marked the introduction of the metric system into sport.[12]

In 1850 an Olympian Class began at Much Wenlock, in Shropshire, England. It was renamed the Wenlock Olympian Games in 1859, and continues today as the Wenlock Olympian Society Annual Games. In 1866, a national Olympic Games in Great Britain was organized by Dr. William Penny Brookes at London's Crystal Palace.[13]

Greek interest in reviving the Olympic Games began after the country's independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1829 and was first proposed by poet and newspaper editor Panagiotis Soutsos in his poem "Dialogue of the Dead", published in 1833. Evangelis Zappas, a wealthy Greek philanthropist, sponsored the revival of the ancient Olympic Games. The first modern international Olympic Games was held in 1859 in an Athens city square with participants from Greece and the Ottoman Empire. Later Zappas paid for the complete restoration of the ruins of the ancient Panathenian Stadium so that it could stage two further editions of the Games, one in 1870 and a second in 1875.[14]

French historian Baron Pierre de Coubertin was searching for a reason for the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871). He theorized that the French soldiers had not received proper physical education.[15] In 1890 after attending the Olympian Games of the Wenlock Olympian Society, Coubertin decided that a large-scale revival of the Olympic Games was achievable.[16] Until that time, attempts to create a modern version of the ancient Olympic Games had met with various amounts of success at the local (one, or at most two, participating nations) level.

Coubertin built on the ideas of Brookes and Zappas with the aim to internationalize the Olympic Games.[16] He presented these ideas during the first Olympic Congress of the newly created International Olympic Committee (IOC). This meeting was held from June 16 to June 23, 1894, at the Sorbonne University in Paris. On the last day of the Congress, it was decided that the first multinational Olympic Games would take place two years later in Athens.[17] The IOC was fully responsible for the Games' organization, and, for that purpose, elected the Greek writer Demetrius Vikelas as its first president.[18]

1896 Games

There were fewer than 250 athletes at the first Olympic Games of the modern times. The Panathenian Stadium, restored for Zappas's Games of 1870 and 1875, was refurbished a second time in preparation for this inaugural edition.[19] These Olympics featured nine sporting disciplines: athletics, cycling, fencing, gymnastics, shooting, swimming, tennis, weightlifting, and wrestling; rowing events were scheduled for competition but had to be cancelled due to bad weather conditions.[20] The Greek officials and public were enthusiastic about the experience of hosting the inaugural Games. This feeling was shared by many of the athletes, who even demanded that Athens be the host of the Olympic Games on a permanent basis. The IOC had, however, envisaged these modern Olympics to be an itinerating and truly global event, and thus decided differently, planning for the second edition to take place in Paris.[21]

Changes and adaptations

After the initial success of the 1896 Games, the Olympics endured a struggling period that threatened their survival. The celebrations in Paris in 1900 and St. Louis in 1904 were overshadowed by the World's Fair exhibitions, which were held at the same time frames and locations. The St. Louis Games, for example, hosted 650 athletes, but 580 were originally from the United States. The homogenous nature of these editions was a low point for the Olympic Movement,[22] even though it was in Paris that women were first allowed to compete.[23] The Games rebounded when the 1906 Intercalated Games (so-called because they were the second Games held within the third Olympiad) were held in Athens. The Intercalated Games are not officially recognized as an official Olympic Games, and no later Intercalated Games have been held. These Games attracted a broad international field of participants, and generated great public interest. This marked the beginning of a rise in both the popularity and the size of the Games.[24]

Winter Games

While both figure skating (1908 and 1920 Games) and ice hockey (1920 Games) had featured as Olympic events at the Summer Olympics, the IOC looked upon equity between winter and summer sports. At the 1921 Congress, in Lausanne, it decided to hold a winter version of the Olympic Games. The first Winter Olympics were held in 1924 in Chamonix, France, though they were only officialy recognized by the IOC as such in the following year.[25] The IOC made the Winter Games a permanent fixture in the Olympic Movement in 1925 and mandated that they be celebrated every four years on the same year as their Summer counterpart.[26] This tradition was maintained until the 1992 Games in Albertville, France; after that, beginning with the 1994 Games, further Winter Games have been held on the third year of each Olympiad.

Paralympics

In 1948 Sir Ludwig Guttman, determined to innovate new ways to rehabilitate soldiers after World War II, organized a multi-sport event between various hospitals to coincide with the 1948 London Olympics. Guttman's event, known then as the Stoke Mandeville Games, became an annual sports festival. Over the next twelve years, Guttman and others continued their efforts to use sports as an avenue to healing. For the 1960 Olympic Games, in Rome, Guttman brought 400 athletes to compete in the "Parallel Olympics", which became known as the first Paralympics. Since then, the Paralympics have been held in every Olympic year; since the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, South Korea, the host city for the Olympics has also played host to the Paralympics.[27]

Youth Games

The Youth Olympic Games (YOG) were conceived by IOC president Jacques Rogge, in 2001,[28] and approved by the IOC during the 119th IOC session, held in July 2007 in Guatemala City.[29] The Youth Games will be shorter than their summer and winter Olympic counterparts: the summer version will last twelve days, at most, while the winter version will last a maximum of nine days.[30] The IOC will allow no more than 3,500 athletes and 875 officials to participate at the Summer Youth Games, and 970 athletes and 580 officials at the Winter Youth Games.[31][32] The sports to be contested will coincide with those scheduled for the traditional senior Games, however with a reduced number of disciplines and events. [33] The host city for the first Summer Youth Games will be Singapore, in 2010, while the inaugural Winter Games will be hosted in Innsbruck, Austria, two years later.

Recent Games

From the 241 participants representing 14 nations in 1896, the Games have grown to 10,500 competitors from 204 countries at the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.[34] The scope and scale of the Winter Olympics is comparatively smaller. For example, Turin hosted 2,508 athletes from 80 countries competing in 84 events, during the 2006 Winter Olympics.[35] As participation in the Olympics has grown, so has its profile in the international media. At the Sydney Games in 2000, an estimated 3.7 billion viewers watched the Games on television, and the official website generated over 11.3 billion hits.[36]

The number of participating countries is noticeably higher than the 193 countries that are current members of the United Nations. The IOC allows nations to compete that do not meet the strict requirements for political sovereignty that other international organizations demand. As a result, colonies and dependencies are permitted to set up their own Olympic teams and athletes, even if such competitors also hold citizenship in another member nation. Examples of this include territories such as Puerto Rico, Bermuda, and Hong Kong, all of which compete as separate nations despite being legally a part of another country.

Olympic Movement

The Olympic Movement is defined by the rules and guidelines of the Olympic Charter. It includes organizing committees for specific Games, International Federations for each sport featured at the Games, and the National Olympic Committees for each nation represented at the Games. The umbrella organization of the Olympic Movement is the International Olympic Committee (IOC), currently headed by Jacques Rogge.[37] The IOC oversees the planning of the Olympic Games and insures the host city is meeting its obligations. It makes all the important decisions such as choosing the host city and the event program for each Games. The three major components of the Olympic Movement beyond the IOC are described in further detail as follows:

- International Federations (IFs), are the governing bodies of each sport (for example, FIFA, the IF for football (soccer), and FIVB, the international governing body for volleyball). There are currently 35 International Federations in the Olympic Movement.[38]

- National Olympic Committees (NOCs), which regulate the Olympic Movement within each country (e.g. USOC, the NOC of the United States). There are 205 NOCs recognized by the IOC.[34]

- Organizing Committees for the Olympic Games (OCOGs), which are the committees responsible for the organization of a specific celebration of the Olympics. OCOGs are dissolved after the celebration of each Games, once all subsequent paperwork has been completed.

French and English are the official languages of the Olympic Movement. The other official language used at each Olympic Games is the official language of the host country. Consequently, every proclamation (such as the announcement of each country during the parade of nations in the opening ceremony) is spoken in these three languages.[39]

Criticism

The IOC has often been criticized for being an intractable organization, with several members on the committee for life. The leadership of IOC presidents Juan Antonio Samaranch and Avery Brundage was especially controversial. Brundage was president of the IOC for over 20 years. During his tenure he protected the Olympics from untoward political involvement.[40] He was also accused of both racism, for his handling of the apartheid issue with the South African delegation, and anti-Semitism.[41] Under the Samaranch presidency the office was accused of both nepotism and corruption.[42] Samaranch's ties with the Franco regime in Spain was also a source of criticism.[43]

In 1998, it became known that several IOC members had taken bribes from the organizing committee for the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, Utah, in exchange for voting for the city at the election of the host city. The IOC started an investigation, which led to four members resigning and six being expelled. The scandal set off further reforms, changing the way host cities are selected to avoid further bribes.[44]

A BBC documentary, which aired in August 2004, entitled Panorama: Buying the Games, investigated the taking of bribes in the bidding process for the 2012 Summer Olympics. The documentary claimed it is possible to bribe IOC members into voting for a particular candidate city. After being narrowly defeated in their bid for the 2012 Summer Games,[45] Parisian Mayor Bertrand Delanoë specifically accused the British Prime Minister Tony Blair and the London Bid Committee (headed by former Olympic gold medalist Sebastian Coe) of breaking the bid rules. He cited French President Jacques Chirac as a witness; Chirac gave guarded interviews regarding his involvement.[46][47] The issue was never fully pursued. The Turin bid for the 2006 Winter Olympics was also shrouded in controversy. A prominent member of the IOC, Marc Hodler, himself strongly connected with rival Sion, Switzerland's bid, alleged bribery of IOC officials by members of the Turin Organizing Committee. These accusations led to a wide-ranging investigation. The allegations also served to sour many IOC members to Sion's bid and may have helped Turin to capture the host city nomination.[48]

Symbols

The Olympic Movement uses symbols to represent the ideals embodied in the Olympic Charter. The Olympic rings are the main image of the Movement and one of the world's most recognized symbols. The five intertwined rings represent the unity of the five inhabited continents (with the Americas regarded as a single continent).[49]

The five colored rings on a white field form the Olympic flag. The colors—white, red, blue, green, yellow, and black—were chosen because every nation had at least one of these colors in its national flag. The flag was adopted in 1914, but was first flown only at the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp, Belgium. It is hoisted in each opening ceremony of the Games and lowered at the closure.[50]

The Olympic motto is Citius, Altius, Fortius, a Latin expression meaning "Faster, Higher, Stronger". Coubertin's ideals are illustrated by the Olympic Creed:

The most important thing in the Olympic Games is not to win but to take part, just as the most important thing in life is not the triumph but the struggle. The essential thing is not to have conquered but to have fought well.[50]

Months before each Games, the Olympic flame is lit in Olympia in a ceremony that reflects ancient Greek rituals. A female performer, acting as a priestess, ignites a torch by placing it inside a parabolic mirror which focuses the sun's rays; she then lights the torch of the first relay bearer, thus initiating the Olympic torch relay that will carry the flame to the host city's Olympic stadium, [51] where it plays an important role in the opening ceremony. Though the flame has been an Olympic symbol since 1928, the torch relay was only introduced in 1936, as part of the German government's attempt to promote its National Socialist ideology.[50]

The Olympic mascot, an animal or human figure representing the cultural heritage of the host country, was introduced in 1968. It has played an important part of the Games since 1980, with the success of Misha, the Russian bear. The mascots of the most recent Summer Olympics, in Beijing, were the Fuwa. They are five creatures that represent the five fengshui elements important in Chinese culture.[52]

Ceremonies

Opening

As mandated by the Olympic Charter, various elements frame the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games.[53][54] Most of these rituals were established at the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp.[55] The ceremony typically starts with the hoisting of the host country's flag and a performance of its national anthem.[53][54] The host nation then presents artistic displays of music, singing, dance, and theater representative of its culture.[55] The artistic presentations have grown in scale and complexity as successive hosts attempt to provide a ceremony that outlasts its predecessor's in terms of memorability. The opening ceremony of the Beijing Games reportedly cost $100 million, with much of the cost incurred in the artistic segment.[56]

The protocol proceeds with the Parade of Nations, during which most participating athletes march into the stadium country by country. Since the 1928 Summer Olympics, Greece enters first due to its historical status as the birthplace of the Olympics, while the host nation closes the parade.[53][54] After all national delegations have entered the stadium, the organizing committee president and the IOC president deliver a speech, after which an official representative of the host country declares the Games open. The Olympic Flag is then carried into the stadium and hoisted as the Olympic Anthem is played. The flag-bearers of all delegations circle a rostrum, where one athlete (since the 1920 Summer Olympics) and one judge (since the 1972 Summer Olympics) pronounce the Olympic Oath, whereby they declare they will compete and judge according to the rules.[53][54] Finally, the Olympic Torch is brought into the stadium and passed on until it reaches the last carrier—often a well-known and successful Olympic athlete from the host nation—who lights the Olympic Flame in the stadium's cauldron.[53][54]

Closing

The closing ceremony of the Olympic Games takes place after all sporting events have concluded. Flag-bearers from each participating country enter the stadium, followed by the athletes without any distinction or grouping by nationality, as opposed to what happens during the opening ceremony. Three national flags are hoisted while the corresponding national anthems are played: the flag of Greece, to honor the birthplace of the Olympic Games; the flag of the current host country, and the flag of the country hosting the next Summer or Winter Olympic Games.[57] The president of the organizing committee and the IOC president make their closing speeches, and the Games are then officially closed. The Olympic Flame is extinguished and, while the Olympic Anthem is played, the Olympic Flag is lowered and carried away from the stadium.[58] In what is known as the Antwerp Ceremony, the mayor of the city that organized the Games transfers a special Olympic flag to the president of the IOC, who then passes it on to the mayor of the city hosting the next Olympic Games.[59] After these compulsory elements, the next host nation briefly introduces itself with artistic displays of dance and theater representative of its culture, a tradition dating back to the 1976 Montreal Games.

Medal presentation

After completion of each Olympic event, a medal ceremony is held, where the best three athletes stand on top of a three-tiered rostrum to be awarded their respective medals.[60] After the medals are given out by an IOC member, the national flags of the three medalists are raised while the national anthem of the gold medalist's country plays.[61] Volunteering citizens of the host country also act as hosts during the medal ceremonies, as they aid the officials who present the medals and act as flag-bearers.[62] For every Olympic event, the respective medal ceremony is held, at most, one day after the event's final. A notable exception is the men's marathon: the competition is usually held early in the morning on the last day of Olympic competition and its medal ceremony is then held in the evening during the closing ceremony.

Sports

Currently, the Olympic Games program consists of 33 sports, 52 disciplines and nearly 400 events. The Summer Olympics program includes 26 sports with 36 disciplines, while the Winter Olympics program is comprised of 7 sports with 15 disciplines.[63] Athletics, swimming, fencing, and artistic gymnastics are the only summer sports or disciplines that have never been absent from the Olympic program since 1896. Cross country skiing, figure skating, ice hockey, Nordic combined, ski jumping, and speed skating have always been featured in the Winter Olympics program since 1924. Current Olympic sports, like badminton, basketball, and volleyball, first appeared on the program as demonstration sports, and were later promoted to medal-awarding sports. Some sports that featured in earlier Games were dropped from the program at some point; while many never returned to the Olympic Games—discontinued sports, like golf, polo, and lacrosse[64]—, others were successfully reinstated (archery[65] and tennis[66]).

The Olympic sports are governed by international sports federations (IFs) recognized by the IOC as the global supervisors of those sports. The current list of Olympic IFs comprises 35 federations.[67] The sports administered by recognized IFs but that have never been included on the Olympic program are not considered "Olympic",[68] but can be promoted to such status during a program revision that should occur in the first session following each Games.[69] During such revision, sports can be excluded or included in the program provided a two-thirds majority vote of the IOC membership is achieved.[70] An Olympic sport that was voted out of the program does not lose its status and may be reincluded at a subsequent Games.

The 114th IOC Session, in 2002, limited the Summer Games program to a maximum of 28 sports, 301 events, and 10,500 athletes.[71] Three years later, at the 117th IOC Session, the first major program revision was performed, resulting in the exclusion of baseball and softball from the official program of the 2012 London Games. Since there was no agreement in the promotion of two other sports, the 2012 program will feature just 26 sports.[71] In 2007, during the 119th IOC Session, the number of core sports for the Summer Olympics was raised from 15 to 25, keeping 28 sports as the maximum number.[71] The core sports and potential additional sports are specifically chosen for each Games through a majority vote of the IOC membership.[67]

Amateurism and professionalism

The ethos of the aristocracy as exemplified in the English public schools greatly influenced Pierre de Coubertin.[72] The public schools subscribed to the belief that sport formed an important part of education, an attitude summed up in the saying mens sana in corpore sano, a sound mind in a sound body. In this ethos, a gentleman was one who became an all-rounder, not the best at one specific thing. There was also a prevailing concept of fairness, in which practicing or training was considered tantamount to cheating.[72] Those who practiced a sport professionally were considered to have an unfair advantage over those who practiced it merely as a hobby.[72]

The exclusion of professionals caused several controversies throughout the history of the modern Olympics. The 1912 Olympic pentathlon and decathlon champion Jim Thorpe was stripped of his medals when it was discovered that he had played semi-professional baseball before the Olympics. He was restored as champion on compassionate grounds by the IOC in 1983.[73] Swiss and Austrian skiers boycotted the 1936 Winter Olympics in support of their skiing teachers, who were not allowed to compete because they earned money with their sport and were thus considered professionals.[74]

As class structure evolved through the 20th century, the definition of the amateur athlete as an aristocratic gentleman became outdated.[72] The advent of the state-sponsored "full-time amateur athlete" of the Eastern Bloc countries further eroded the ideology of the pure amateur, as it put the self-financed amateurs of the Western countries at a disadvantage. Nevertheless, the IOC held to the traditional rules regarding amateurism.[75] Beginning in the 1970s, amateurism requirements were gradually phased out of the Olympic Charter. Eventually the decisions on professional participation were left to the IFs. As of 2004, the only sport in which no professionals compete is boxing, although even this requires a definition of amateurism based on fight rules rather than on payment, as some boxers receive cash prizes from their National Olympic Committees. In men's football (soccer), the number of players over 23 years eligible to participate in the Olympic tournament is limited to three per team.[76]

Controversies

Boycotts

The 1956 Melbourne Olympics were the first Olympics to be boycotted. The Netherlands, Spain, and Switzerland refused to attend because of the repression of the Hungarian uprising by the Soviet Union; additionally, Cambodia, Egypt, Iraq and Lebanon boycotted the Games due to the Suez Crisis.[77] In 1972 and 1976 a large number of African countries threatened the IOC with a boycott to force them to ban South Africa and Rhodesia, because of their segregationist regimes. New Zealand was also one of the African boycott targets, due to the "All Blacks" (national rugby team) having toured apartheid-ruled South Africa. The IOC conceded in the first two cases, but refused to ban New Zealand on the grounds that rugby was not an Olympic sport.[78] Fulfilling their threat, twenty African countries were joined by Guyanna and Iraq in a Tanzania-led withdrawal from the Montreal Games, after a few of their athletes had already competed.[78][79] Taiwan also decided to skip these Games since the People's Republic of China (PRC)—not attending the Games after breaking away with the IOC, in 1958, over the island's political status within the organization—exerted pressure on the Montreal organizing committee to keep the delegation from the Republic of China (ROC) from competing under the such name. The ROC refused a proposed compromise that would have still allowed them to use the ROC flag and anthem as long as the name was changed.[80] Taiwan did not participate again until 1984, when it returned under the name of Chinese Taipei and with a special flag.[81]

In 1980 and 1984, the Cold War opponents boycotted each other's Games. Sixty-five nations refused to compete at the Moscow 1980 Olympics because of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. This boycott reduced the number of nations participating to only 81, the lowest number since 1956.[82] The Soviet Union and 14 of its Eastern Bloc partners (except Romania) countered by boycotting the Los Angeles 1984 Olympics, contending that they could not guarantee the safety of their athletes. Soviet officials were quoted as saying that "chauvinistic sentiments and an anti-Soviet hysteria are being whipped up in the United States", this being the reason for not attending the Games.[83] The boycotting nations staged their own alternate event, the Friendship Games, in July and August.[84][85]

There had been growing calls for boycotts of Chinese goods and the 2008 Olympics in Beijing in protest of China's human rights record and response to the recent disturbances in Tibet, Darfur, and Taiwan. U.S. President George W. Bush showcased these concerns in a highly publicized speech in Thailand just prior to the opening of the Games. Ultimately, no nation withdrew before the Games.[86][87][88]

Politics

Contrary to its refounding principles, the Olympic Games have been used as a vehicle to promote political ideologies. The Soviet Union, for example, did not participate until the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki. Instead, in 1928, the Soviets organized an international sports event called Spartakiads. Other communist countries organized Workers Olympics during the inter-war period of the 1920s and 1930s. These events were held as an alternative to the Olympics, which were seen as a capitalist and aristocratic event.[89][90] It was not until the 1960 Games that the Soviets emerged as a sporting superpower and, in doing so, took full advantage of the publicity that came with winning at the Olympics.[91]

Individual athletes have also used the Olympic stage to promote their own political agenda. At the 1968 Summer Olympics, in Mexico City, two American track and field athletes, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who finished first and third in the 200 meter sprint race, performed the Black Power salute on the victory stand. The second place finisher Peter Norman wore an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge in support of Smith and Carlos. In response to the protest, IOC President Avery Brundage told the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) to either send the two athletes home or withdraw the complete track and field team. The USOC opted for the former.[92] The photo of the three men on the medal podium has become an iconic Olympic image.[93]

Far from being a thing of the past, interference of politics in the Games still occurs. The government of Iran has taken steps to avoid any competition between its athletes and those from Israel. Evidence of this was seen at the 2004 Summer Olympics when an Iranian judoka did not compete in a match against an Israeli. Although he was officially disqualified for excessive weight, Arash Miresmaeli was awarded US$125,000 in prize money by the Iranian government, an amount paid to all Iranian gold medal winners. He was officially cleared of intentionally avoiding the bout, but his receipt of the prize money raised suspicion.[94]

The Olympics feature individual athletes who compete within a national team, and their motivation to succeed is both personal achievement and national glory. With the increase in global mobility, the athlete's national identity can become blurred.[95] Kristy Coventry, a white Zimbabwean swimmer, spent eight years training for the 2004 and 2008 Summer Olympics while living in the United States. Her victories in Beijing sparked a wave of national pride that temporarily set aside mounting political and racial tension in Zimbabwe.[96]

Use of performance enhancing drugs

In the early 20th century, many Olympic athletes began using drugs to improve their athletic abilities. For example, the winner of the marathon at the 1904 Games, Thomas J. Hicks, was given strychnine and brandy by his coach.[97] As these methods became more extreme, it became increasingly evident that doping was not only a threat to the integrity of sport but could also have potentially fatal side effects on the athlete. The only Olympic death linked to doping occurred at the Rome Games of 1960. During the cycling road race, Danish cyclist Knud Enemark Jensen fell from his bicycle and later died. A coroner's inquiry found that he was under the influence of amphetamines.[98] By the mid-1960s, sports federations were starting to ban the use of performance enhancing drugs, and the IOC followed suit in 1967.[99]

The first Olympic athlete to test positive for the use of performance enhancing drugs was Hans-Gunnar Liljenwall, a Swedish pentathlete at the 1968 Summer Olympics, who lost his bronze medal for alcohol use.[100] The most publicized doping-related disqualification was that of Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson, who won the 100 meter dash at the 1988 Seoul Olympics but tested positive for stanozolol. His gold medal was subsequently stripped and awarded to runner-up Carl Lewis, who himself had tested positive for banned substances prior to the Olympics but had not been banned.[101]

In the late 1990s, the IOC took the initiative in a more organized battle against doping, leading to the formation of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) in 1999. The 2000 Summer Olympics and 2002 Winter Olympics have shown that this battle is not nearly over, as several medalists in weightlifting and cross-country skiing were disqualified due to doping offenses. During the 2006 Winter Olympics, only one athlete failed a drug test and had a medal revoked. The IOC-established drug testing regimen (now known as the "Olympic Standard") has set the worldwide benchmark that other sporting federations around the world attempt to emulate.[102] During the Beijing games, 3,667 athletes were tested by the IOC under the auspices of the World Anti-Doping Agency. Both urine and blood testing was used in a coordinated effort to detect not only banned substances but also blood doping. While several athletes were barred from competition by their National Olympic Committees prior to the Games, three athletes failed drug tests while in competition in Beijing.[103][104]

Violence

Despite what Coubertin had hoped for, the Olympics did not bring total peace to the world. In fact, three Olympiads had to pass without a celebration of the Games because of war: the 1916 Games were cancelled due to World War I, and the summer and winter games of 1940 and 1944 were cancelled because of World War II. The South Ossetia War between Georgia and Russia erupted on the opening day of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. Both President Bush and Prime Minister Putin were attending the Olympics at that time and spoke together about the conflict at a luncheon hosted by Chinese President Hu Jintao.[105] When Nino Salukvadze of Georgia won the bronze medal in the 10 meter air pistol competition, she stood on the medal podium with Natalia Paderina, a Russian shooter who had won the silver. In what became a much-publicized event from the Beijing Games, Salukvadze and Paderina embraced on the podium after the ceremony had ended.[106]

Terrorism has also threatened the Olympic Games. In 1972, when the Summer Games were held in Munich, West Germany, eleven members of the Israeli Olympic team were taken hostage by the terrorist group Black September in what is now known as the Munich massacre. A bungled liberation attempt led to the deaths of the nine abducted athletes who had not been killed prior to the rescue. Also killed were five of the terrorists and a German policeman.[107] Another example of terrorism at the Olympics came during the Summer Olympics in 1996 in Atlanta. A bomb was detonated at the Centennial Olympic Park, which killed 2 and injured 111 others. The bomb was set by Eric Robert Rudolph, an American domestic terrorist, who is currently serving a life sentence at ADX Florence in Florence, Colorado.[108]

Champions and medalists

The athletes or teams who place first, second, or third in each event receive medals. The winners receive gold medals, which were solid gold until 1912. After 1912 the medals were made of gilded silver and now gold plated silver. Every gold medal must contain at least six grams of pure gold.[109] The runners-up receive silver medals and the third-place athletes are awarded bronze medals. In events contested by a single-elimination tournament (most notably boxing), third place might not be determined and both semifinal losers receive bronze medals. The practice of awarding medals to the top three competitors was introduced in 1906; at the 1896 Olympics only the first two received a medal, first place received silver and second received bronze. Various prizes, including for works of art, were awarded in 1900. The 1904 Olympics also awarded silver trophies for first place. The three medal format was first used at the Intercalated Games of 1906. Since the IOC no longer recognizes these as official Olympic Games, the first official awarding of the three medals came in the London Olympics of 1908. From 1948 onward athletes placing fourth, fifth, and sixth have received certificates, which became officially known as "victory diplomas". In 1984 victory diplomas for seventh and eighth-place finishers were added. At the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, the gold, silver, and bronze medal winners were also given olive wreaths.[110] The IOC does not keep track of overall medal tallies per country, but the media often publish unofficial medal counts. National Olympic Committees also keep track of medal statistics as a measure of success.[111]

All-time individual medal count

The question of which athlete is the most successful of all time is a difficult one to answer. The diversity of the sports and the evolution of the Olympic Games since 1896 complicate the matter. While it may not be the most equitable way to measure success, a list of the most titles won at the Modern Olympic Games by individuals is one way to determine the greatest Olympic athletes of all time.

| Athlete | Nation | Sport | Olympics | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michael Phelps | Swimming | 2000–2008 | 14 | 0 | 2 | 16 | |

| Larissa Latynina | Gymnastics | 1956–1964 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 18 | |

| Paavo Nurmi | Athletics | 1920–1928 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 12 | |

| Mark Spitz | Swimming | 1968–1972 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 11 | |

| Carl Lewis | Athletics | 1984–1996 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 10 | |

| Bjørn Dæhlie | Cross-country skiing | 1992–1998 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 12 | |

| Birgit Fischer | Canoeing (flatwater) | 1980–2004 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 12 | |

| Sawao Kato | Gymnastics | 1968–1976 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 12 | |

| Jenny Thompson | Swimming | 1992–2004 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 12 | |

| Matt Biondi | Swimming | 1984–1992 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 11 | |

| Ray Ewry | Athletics | 1900–1908 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | |

| Nikolai Andrianov | Gymnastics | 1972–1980 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 15 | |

| Boris Shakhlin | Gymnastics | 1956–1964 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 13 | |

| Věra Čáslavská | Gymnastics | 1960–1968 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 11 |

Host cities

By 2012, the Olympic Games will have been hosted by 42 cities in 22 countries, but only by cities outside Europe and North America on 7 occasions. Since the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, South Korea, the Olympics have been held in Asia or Oceania 4 times, which is a sharp increase compared to the previous 92 years of modern Olympic history. All bids by countries in South America and Africa have failed. The number in parentheses following the city or country denotes how many times that city or country had then hosted the games. The table includes the Intercalated Games of 1906, which the IOC no longer considers an official Olympic Games.

| Youth Summer Olympic Games | Youth Winter Olympic Games | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | № | Host city | Country | № | Host city | Country |

| 2010 | I | Singapore (1) | ||||

| 2012 | I | Innsbruck (1) | ||||

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Pausanias (1926), "Elis 1", VII, 9.

- ^ Pausanias (1926), "Elis 1", VII, 10.

- ^ Pausanias (1926), "Elis 1", VII, 7.

- ^ Grote vol. 2 (1901), 242

- ^ Burkert, Walter (1983). "Pelops at Olympia". Homo Necans. University of California Press. p. 95.

- ^ "Ancient Olympic Games - Gods". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ^ Swaddling, Judith (1999). The Ancient Olympic Games. University of Texas Press. p. pp.90–93. ISBN 0292777515.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|page=has extra text (help) - ^ Olympic Museum, "The Olympic Games in Antiquity", p. 2.

- ^ Olympic Museum, "The Olympic Games in Antiquity", p. 13.

- ^ Bury (1889), p. 311

- ^ a b "Origin of Robert Dover's Games". Robert Dover's Cotswold Olimpicks. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ^ a b "Histoire et évolution des Jeux olympiques". Potentiel (in French). 2005. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ^ "Much Wenlock & the Olympian Connection". Wenlock Olympian Society. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ^ Young (1996), 2, 13–23, 81

- ^ Young (1996), 68

- ^ a b "Rugby School motivated founder of Games". Reuters. SI.com. 2004-07-08. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ Coubertin, Philemon, Politis & Anninos (1897), Part 2, page 8

- ^ Young (1996), 100–105

- ^ Darling (2004), 135

- ^ Coubertin, Philemon, Politis & Anninos (1897), Part 2, pages 98–99, 108–109

- ^ "1896 Athina Summer Games". Sports Reference. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ "St. Louis 1904 — Overview". ESPN. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ^ "Paris 1900". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ^ "1906 Olympics mark 10th anniversary of the Olympic revival". Canadian Broadcasting Centre. 2008-05-28. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ^ "Chamonix 1924". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ^ "Winter Olympics History". Utah Athletic Foundation. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ^ "History of the Paralympics". BBC Sport. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ^ "Rogge wants Youth Olympic Games". BBC Sport. 2007-03-19. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ^ Rice, John (2007-07-05). "IOC approves Youth Olympics; first set for 2010". The Associated Press. USA Today. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ^ "IOC to Introduce Youth Olympic Games in 2010". CRIenglish.com. 2007-04-25. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- ^ "IOC session: A "go" for Youth Olympic Games". International Olympic Committee. 2007-07-05. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ^ "No kidding: Teens to get Youth Olympic Games". USA Today. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ Michaelis, Vicky (2007-07-05). "IOC votes to start Youth Olympics in 2010". USA Today. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ^ a b "IOC Factsheet" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ^ "Turin 2006". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ^ "100 Years of Olympic Marketing". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ^ "International Olympic Committee". The International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ "For the Good of the Athletes". The Beijing Organizing Committee for the Games of the XXIX Olympiad. 2007-10-31. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ Olympic Charter (2007), Rule 24, p. 53.

- ^ Maraniss (2008), 52–60

- ^ Maraniss (2008), 60–69

- ^ "Samaranch Defends Nominating Son for IOC Post". CBC Sports. 2001-05-18. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ Riding, Alan (1992-06-30). "Olympics:Barcelona Profile; Samaranch, Under the Gun Shoots Back". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ^ Abrahamson, Alan (2003-12-06). "Judge Drops Olympic Bid Case". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ^ Zinser, Lynn (2005-07-07). "London Wins 2012 Olympics New York Lags". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ "Paris Mayor Slams London Tactics". Sportinglife.com. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ Beard, Mark (2006-04-20). "Olympic Inspectors call on London (while Paris accusses Britain of bribery)". Business Network. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ Berkes, Howard (2006-02-07). "How Turin got the Games". National Public Radio. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ Nelson Doyle (October 18, 2007). "The World's Most Recognizable Symbols and Trademarks". Bizcovering.com. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ a b c "The Olympic Symbols" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ "The Olympic flame and the torch relay" (PDF). Olympic Museum. International Olympic Committee. 2007. p. 6. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ "The Official Mascots of the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games". The Beijing Organizing Committee for the Games of the XXIX Olympiad. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ^ a b c d e "Fact sheet: Opening Ceremony of the Summer Olympic Games" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e "Fact sheet: Opening Ceremony of the Winter Olympic Games" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "The Modern Olympic Games" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. pp. p. 5. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help);|pages=has extra text (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ "Beijing Dazzles: Chinese History, on Parade as Olympics Begin". Canadian Broadcasting Centre. 2008-08-08. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

- ^ "Olympic Closing Ceremony Protocol". New Dehli Television. 2008-08-30. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ^ "Closing Ceremony" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. 2002-01-31. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ "The Olympic Flags and Emblem". VANOC. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Olympic Games - the Medal Ceremonies". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ^ "Symbols and Traditions". USA Today. 1999-07-12. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ^ "Medal Ceremony Hostess Outfits Revealed". China Daily. 2008-07-18. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ^ "Sports". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved February 8, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Olympic Sports of the Past". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Archery". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Tennis". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Olympic Charter (2007), pp. 88–90.

- ^ "International Sports Federations". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved February 8, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Olympic Charter (2007), p. 87.

- ^ "Factsheet: The sessions" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. p. p. 1. Retrieved February 8, 2009.

{{cite web}}:|page=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c "Factsheet: The sports on the Olympic programme" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. 2008. Retrieved February 8, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Eassom, Simon (1994). Critical Reflections on Olympic Ideology. Ontario: The Centre for Olympic Studies. pp. 120–123. ISBN 0-7714-1697-0.

- ^ "Jim Thorpe Biography". Biography.com. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Garmisch-Partenkirchen 1936". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Schantz, Otto. "The Olympic Ideal and the Winter Games Attitudes Towards the Olympic Winter Games in Olympic Discourses — from Coubertin to Samaranch" (PDF). Comité International Pierre De Coubertin. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|form=ignored (help) - ^ "Amateurism". USA Today. July 12, 1999. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Melbourne/Stockholm 1956: Did you know?". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b "African nations boycott costly Montreal Games". CBC Sports. July 30, 2008. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Africa and the XXIst Olympiad" (PDF). Olympic Review (109–110). International Olympic Committee: pp. 584–585. 1976. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Game playing in Montreal" (PDF). Olympic Review (107–108). International Olympic Committee: pp. 461–462. 1976. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "China-Olympic History". Chinaorbit.com. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ "Moscow 1980: Did you know?". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Burns, John F. (May 9, 1984). "Protests are Issue: Russians Charge 'Gross Flouting' of the Ideals of the Competition". New York Times. New York Times Company.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "1980 Moscow Olympic Games". Moscow-Life. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Los Angeles 1984: Did you know?". International Olympic Committee. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Australia: Calls to Boycott Beijing Olympics "Australia: Calls to Boycott Beijing Olympics". Inter Press Service. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Reporters sans frontières - Beijing 2008 "Beijing 2008". Reporters Without Borders. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Diplomats Visit Tibet as EU Split on Olympic Opening Boycott". The Economic Times. March 29, 2008. Retrieved February 7, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Spartakiads". Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Vol. Vol. 24 (part 1). Moscow. 1976. p. 286.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|volume=has extra text (help);|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Roche (2000), p. 106

- ^ Maraniss (2008), pp. 392–399

- ^ "1968: Black athletes make silent protest". BBC. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Iconic Image of Protest Still Resonates". The Irish Times. August 4, 2008. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Iranian Judoka rewarded after snubbing Israeli". Associated Press. NBC Sports. September 8, 2004. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Schaffer & Smith (2000), p. 7

- ^ "Kristy Coventry, Profile & Bio". NBColympics.com. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Tom Hicks". Sports-reference.com. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ^ "A Brief History of Anti-Doping". World Anti-Doping Agency. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ^ Begley, Sharon (2008-01-07). "The Drug Charade". Newsweek. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ Porterfield (2008), 15

- ^ Magnay, Jacquelin (2003-04-18). "Carl Lewis's positive test covered up". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ^ Coile, Zachary (2005-04-27). "Bill Seeks to Toughen Drug Testing in Pro Sports". The San Francisco Chornicle. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- ^ "Doping: 3667 athletes tested, IOC seeks action against Halkia's coach". Express India Newspapers. 2008-08-19. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ^ "A Brief History of Anti-Doping". World Anti-Doping Agency. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ^ "Bush turns attention from politics to Olympics". Associated Press. MSNBC. 2008-08-07. Retrieved 2009=01=30.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Olympic Shooters Hug as their Countries do Battle". CNN. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ^ "Olympic archive". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ^ "Olympic Park Bombing". CNN. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ^ "Medals of Beijing Olympic Games Unveiled". The International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- ^ "The Modern Olympic Games" (PDF). The Olympic Museum. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|form=ignored (help) - ^ Munro, James (2008-08-25). "Britain may aim for third in 2012". BBC Sport. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ^ "Official Report of the Equestrian Games of the XVIth Olympiad (Swedish & English)" (PDF). Los Angeles 1984 Foundation. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- ^ "Beijing 2008". The International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

References

- Bury, John Bagnell (1889). A History of the Later Roman Empire. Vol. Vol. 1. London: Macmillan. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Coubertin, Pierre De (1897). The Olympic Games: BC 776 – AD 1896 (PDF). Athens: Charles Beck. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Darling, Janina K. (2004). "Panathenaic Stadium, Athens". Architecture of Greece. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-32152-3. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- Grote, George (1901). A History of Greece. Vol. Vol. 2. New York: Peter Fenelon Collier & Son.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|accessdagte=ignored (help) - Grote, George (1888). A History of Greece. Vol. Vol. 9. London: John Murray. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - International Olympic Committee (2007). "Olympic Charter" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 2009-02-12.

- Maraniss, David (2008). Rome 1960. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 1-4165-3407-5.

- Pausanias (January 1, 1926). Description of Greece. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. Vol. 2. translated by W. H. S. Jones and H. A. Ormerud. London: W. Heinemann. ISBN 0674992075. OCLC 10818363. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Porterfield, Jason (2008). Doping:Athletes and Drugs. New York: Rosen Publishing Group Inc. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4042-1917-5. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

{{cite book}}: Text "Google Book Search" ignored (help) - Olympic Museum (2007). "The Olympic Games in Antiquity" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- Roche, Maurice (2000). Mega-Events and Modernity. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 0-415-15711-0. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- Schaffer, Kay; Smith, Sidonie (2000). Olympics at the Millennium. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2819-4. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

{{cite book}}: Text "Google Book Search" ignored (help) - Young, David C. (1996). The Modern Olympics: A Struggle for Revival. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-801-87207-3.

Further reading

- Buchanan, Ian (2001). Historical dictionary of the Olympic movement. Lanham: Scarecrow Presz. ISBN 978-0-8108-4054-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Kamper, Erich (1992). The Golden Book of the Olympic Games. Milan: Vallardi & Associati. ISBN 978-88-85202-35-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Preuss, Holger (2005). The Economics of Staging the Olympics: A Comparison of the Games 1972-2008. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84376-893-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Simson, Vyv (1992). Dishonored Games: Corruption, Money, and Greed at the Olympics. New Tork: S.P.I. Books. ISBN 978-1-56171-199-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Wallechinsky, David (2000). The Complete Book of the Summer Olympics, Sydney 2000 Edition. Overlook Press. ISBN 978-1-58567-033-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Wallechinsky, David (2001). The Complete Book of the Winter Olympics, Salt Lake City 2002 Edition. Overlook Press. ISBN 978-1-58567-195-3.

- Wallechinsky, David (2004). The Complete Book of the Summer Olympics, Athens 2004 Edition. SportClassic Books. ISBN 978-1-894963-32-9.

- Wallechinsky, David (2005). The Complete Book of the Winter Olympics, Turin 2006 Edition. SportClassic Books. ISBN 978-1-894963-45-9.

External links

- Official website of the Olympic Games

- Olympic, an external wiki

- Aerial and Satellite Photography of Olympic Stadiums

- All the daily program and the results of the Olympics

- ATR - Around the Rings - the Business Surrounding the Olympics

- Database Olympics

- Dicolympic - Dictionary about the Games from Olympia to Sochi 2014

- Olympics Memories

- Reference book about all Olympic Medalists of all times

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA