Filipino Americans

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 4.2 million (2019)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

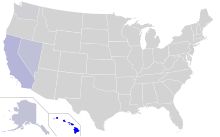

| Western United States, Hawaii, especially in metropolitan areas and elsewhere as of 2010 | |

| California | 1,651,933[2] |

| Hawaii | 367,364[2] |

| Texas | 194,427[2] |

| Washington | 178,300[2] |

| Nevada | 169,462[2] |

| Illinois | 159,385[2] |

| New York | 144,436[2] |

| Florida | 143,481[2] |

| New Jersey | 129,514[2] |

| Virginia | 108,128[2] |

| Languages | |

| English (American, Philippine),[3] Tagalog (Filipino),[3][4] Ilocano, Pangasinan, Kapampangan, Bikol, Visayan languages (Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Waray), Chavacano, and other languages of the Philippines[3] Chinese (Minnan)[5][6] | |

| Religion | |

| 65% Roman Catholicism 21% Protestantism 8% Irreligion 1% Buddhism[7] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Overseas Filipinos | |

Filipino Americans (Filipino: Mga Pilipinong Amerikano) are Americans of Filipino ancestry. Filipinos and other Asian ethnicities in North America were first documented in the 16th century as mariners and crew members on ships sailing to and from New Spain (Mexico)[8] and a handful of inhabitants in other minute settlements during the time Louisiana was an administrative district of the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Mexico).[9] Mass migration did not begin until the 20th century, when the Philippines was a U.S. territory.[10][11]

As of 2019, there were 4.2 million Filipinos, or Americans with Filipino ancestry, in the United States[12][13] with large communities in California, Hawaii, Illinois, Texas, and the New York metropolitan area.[14]

Terminology

The term Filipino American is sometimes shortened to Fil-Am[15] or Pinoy.[16] Another term which has been used is Philippine Americans.[17] The earliest appearance of the term Pinoy (feminine Pinay), was in a 1926 issue of the Filipino Student Bulletin.[18] Some Filipinos believe that the term Pinoy was coined by Filipinos who came to the United States to distinguish themselves from Filipinos living in the Philippines.[19] Beginning in 2017, started by individuals who identify with the LGBT+ Filipino American population, there is an effort to adopt the term FilipinX; this new term has faced opposition within the broader overseas Filipino diaspora, within the Philippines, and in the United States, with some who are in opposition believing it is an attempt of a "colonial imposition".[20]

Background, demographics, and socioeconomics

History

Filipino mariners and crew members were some of were the first Asians in North America.[21] The first documented presence of Filipinos in what is now the United States dates back to October 1587 when Novohispanic ships loaded with slave workers and some prisoners docked around Morro Bay, California[22][23] with the first permanent settlement in Louisiana in 1763,[24] where they were called "Manilamen" and at least one served in the Battle of New Orleans during the closing stages of the War of 1812.[25][26] and a few Filipinos worked as ranch hands in the western U.S.[27] Mass migration began in the early 20th century when, for a period following the 1898 Treaty of Paris, the Philippines was a territory of the United States. By 1904, Filipino peoples of different ethnic backgrounds were imported by the US government onto the Americas and were displayed at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition as part of a human zoo.[28][29] During the 1920s, many Filipinos immigrated to the United States as unskilled laborers, to provide better opportunities for their families back at home.[30]

Philippine independence was recognized by the United States on July 4, 1946. After independence in 1946, Filipino American numbers continued to grow. Immigration was reduced significantly during the 1930s, except for those who served in the United States Navy, and increased following immigration reform in the 1960s.[31] The majority of Filipinos who immigrated after the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 were skilled professionals and technicians.[30]

General demographics

The 2010 census counted 3.4 million Filipino Americans;[32] in 2011, the United States Department of State estimated the total at 4 million, or 1.1% of the U.S. population.[33] They are the country's second largest self-reported Asian ancestry group according to the 2010 American Community Survey.[34][35] They are also the largest population of Overseas Filipinos.[36] Significant populations of Filipino Americans can be found in California, Hawaii, the New York metropolitan area and Illinois. At the 2010 Census, Filipino Americans surpassed Japanese Americans as the largest Asian group in Hawaii.[37]

As of 2015, the metropolitan areas with the largest Filipino populations were:[38]

| Metropolitan area | Population |

|---|---|

| Los Angeles, California | 495,000 |

| San Francisco, California | 305,000 |

| New York, New York | 241,000 |

| Honolulu, Hawaii | 211,000 |

| San Diego, California | 196,000 |

| Chicago, Illinois | 137,000 |

| Las Vegas, Nevada | 124,000 |

| Riverside, California | 120,000 |

| San Jose, California | 106,000 |

| Seattle, Washington | 101,000 |

Wealth

A 2019 study conducted by Pew Research Center showed that Filipino Americans have a higher level of educational attainment and income than the national average.[39] Filipino Americans show a higher rate of home ownership compared to the average for all Asian Americans.[39] As of 2014, 18% of Filipino American households belonged to the top 10% household income distribution.[40] As of 2018, Filipino Americans held the spot for the second highest median household income.[41] Among all Asians, Filipino Americans show the lowest poverty rate at 7% after Indian Americans at 6%.

Around 47% of Filipino Americans hold management or professional jobs.[42] A 1998 study of physicians and nurses in the U.S. indicated that Filipino American doctors were the second most numerous subgroup among Asian doctors -- there were 1,680 Filipino-American doctors per 100,000 people. The study also showed that Filipino nurses, whether foreign or American-born, had the highest median income among any other ethnicity.[43][44]

Culture

The history of native Filipino peoples, Chinese immigration waves, and Spanish and American rule, plus contact with merchants and traders from many areas culminated in a unique blend of cultures in the Philippines.[45] Filipino American cultural identity has been described as fluid, adopting aspects from various cultures;[46] that said, there has not been significant research into the culture of Filipino Americans.[47] Fashion, dance, music, theater and arts have all had roles in building Filipino American cultural identities and communities.[48][page needed]

In areas of sparse Filipino population, they often form loosely-knit social organizations aimed at maintaining a "sense of family," which is a key feature of Filipino culture. These organizations generally arrange social events, especially of a charitable nature, and keep members up-to-date with local events.[49] Organizations are often organized into regional associations.[50] The associations are a small part of Filipino American life. Filipino Americans formed close-knit neighborhoods, notably in California and Hawaii.[51] A few communities have "Little Manilas," civic and business districts tailored for the Filipino American community.[52] In a Filipino party, shoes should be left in front of the house and greet everyone with a hi or hello. When greeting the elderly, "po" and "opo" must be said in every sentence to show respect.[53]

Some Filipinos have traditional Philippine surnames, such as Bacdayan or Macapagal, while others have surnames derived from Japanese, Indian, and Chinese and reflect centuries of trade with these merchants preceding European and American rule.[54][55][56][57] Reflecting Spanish rule and the Claveria Decree of 1849, most Filipinos adopted Hispanic surnames,[55][6] and celebrate fiestas,[58] but the view that Filipinos may be Hispanic is not universally accepted.[59] The Philippines experienced both Spanish and American colonial territorial status, with its population seen through each nation's racial constructs.[60] In a 2017 Pew Research Survey, only 1% of immigrants from the Philippines identified as Hispanic.[61] Many Filipinos choose to identify as Pacific Islander, while others identify as Asian Americans.[62]

Due to history, the Philippines and the United States are connected culturally.[63] In 2016, there was $16.5 billion worth of trade between the two countries, with the United States being the largest foreign investor in the Philippines, and more than 40% of remittances came from (or through) the United States.[64] In 2004, the amount of remittances coming from the United States was $5 billion;[65] this is an increase from the $1.16 billion sent in 1991 (then about 80% of total remittances being sent to the Philippines), and the $324 million sent in 1988.[66] Some Filipino Americans have chosen to retire in the Philippines, buying real estate.[67][68] Filipino Americans continue to travel back and forth between the United States and the Philippines, making up more than a tenth of all foreign travelers to the Philippines in 2010;[68][69] when traveling back to the Philippines they often bring cargo boxes known as a balikbayan box.[70]

Language

Filipino and English are constitutionally established as official languages in the Philippines, and Filipino is designated as the national language, with English in wide use.[71] Many Filipinos speak American English due to American colonial influence in the country's education system and due to limited Spanish education.[72] Among Asian Americans in 1990, Filipino Americans had the smallest percentage of individuals who had problems with English.[73] In 2000, among U.S.-born Filipino Americans, three quarters responded that English is their primary language;[74] nearly half of Filipino Americans speak English exclusively.[75]

In 2003, Tagalog was the fifth most-spoken language in the United States, with 1.262 million speakers;[4] by 2011, it was the fourth most-spoken language in the United States.[76] Tagalog usage is significant in California, Nevada, and Washington, while Ilocano usage is significant in Hawaii.[77] Many of California's public announcements and documents are translated into Tagalog.[78] Tagalog is also taught in some public schools in the United States, as well as at some colleges.[79] Other significant Filipino languages are Ilocano and Cebuano.[80] Other languages spoken in Filipino American households include Pangasinan, Kapampangan, Hiligaynon, Bicolano, Chavacano, and Waray.[81] However, fluency in Philippine languages tends to be lost among second- and third-generation Filipino Americans.[82] Other languages of the community include Spanish and Chinese (Hokkien).[5] The demonym Filipinx is a gender-neutral term that is applied only to those of Filipino heritage in the diaspora, specifically Filipino-Americans. The term is not applied to Filipinos in the Philippines.[83][84]

Religion

Religious Makeup of Filipino-Americans (2012)[85]

The Philippines is 90% Christian,[58][86] one of only two predominantly Christian countries in Southeast Asia, along with East Timor.[87] Following the European arrival to the Philippines by Ferdinand Magellan, Spaniards made a concerted effort to convert Filipinos to Catholicism; outside of the Muslim sultanates and animist societies, missionaries were able to convert large numbers of Filipinos.[86] and the majority are Roman Catholic, giving Catholicism a major impact on Filipino culture.[88] Other Christian denominations include Protestants (Aglipayan, Episcopalian, and others), and nontrinitarians (Iglesia ni Cristo and Jehovah's Witnesses).[88] Additionally there are those Filipinos who are Muslims, Buddhist or nonreligious; religion has served as a dividing factor within the Philippines and Filipino American communities.[88]

During the early part of the United States governance in the Philippines, there was a concerted effort to convert Filipinos into Protestants, and the results came with varying success.[89] As Filipinos began to migrate to the United States, Filipino Roman Catholics were often not embraced by their American Catholic brethren, nor were they sympathetic to a Filipino-ized Catholicism, in the early 20th century.[90][91] This led to creation of ethnic-specific parishes;[90][92] one such parish was St. Columban's Church in Los Angeles.[93] In 1997, the Filipino oratory was dedicated at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, owing to increased diversity within the congregations of American Catholic parishes.[94] The first-ever American Church for Filipinos, San Lorenzo Ruiz Church in New York City, is named after the first saint from the Philippines, San Lorenzo Ruiz. This was officially designated as a church for Filipinos in July 2005, the first in the United States, and the second in the world, after a church in Rome.[95]

In 2010, Filipino American Catholics were the largest population of Asian American Catholics, making up more than three fourths of Asian American Catholics.[96] In 2015, a majority (65%) of Filipino Americans identify as Catholic;[97] this is down slightly from 2004 (68%).[98] Filipino Americans, who are first generation immigrants were more likely to attend mass weekly, and tended to be more conservative, than those who were born in the United States.[99] Culturally, some traditions and beliefs rooted from the original indigenous religions of Filipinos are still known among the Filipino diaspora.[100][101]

Cuisine

The number of Filipino restaurants does not reflect the size of the population.[102][103][104] Due to the restaurant business not being a major source of income for the community, few non-Filipinos are familiar with the cuisine.[105] Although American cuisine influenced Filipino cuisine,[106] it has been criticized by non-Filipinos.[107] Even on Oahu where there is a significant Filipino American population,[108] Filipino cuisine is not as noticeable as other Asian cuisines.[109] One study found that Filipino cuisine was not often listed in Food frequency questionnaires.[110] On television, Filipino cuisine has been criticized, such as on Fear Factor,[111] and praised, such as on Anthony Bourdain: No Reservations,[112] and Bizarre Foods America.[113]

Filipino American chefs cook in many fine dining restaurants,[114] including Cristeta Comerford who is the executive chef in the White House,[103] though many do not serve Filipino cuisine in their restaurants.[114] Reasons given for the lack of Filipino cuisine in the U.S. include colonial mentality,[104] lack of a clear identity,[104] a preference for cooking at home[103] and a continuing preference of Filipino Americans for cuisines other than their own.[115] Filipino cuisine remains prevalent among Filipino immigrants,[116] with restaurants and grocery stores catering to the Filipino American community,[102][117] including Jollibee, a Philippines-based fast food chain.[118]

In the 2010s, successful and critically reviewed Filipino American restaurants were featured in The New York Times.[119] That same decade began a Filipino Food movement in the United States;[120] it has been criticized for gentrification of the cuisine.[121] Bon Appetit named Bad Saint in Washington, D.C. "the second best new restaurant in the United States" in 2016.[122] Food & Wine named Lasa, in Los Angeles, one of its restaurants of the year in 2018.[123] With this emergence of Filipino American restaurants, food critics like Andrew Zimmern have predicted that Filipino food will be "the next big thing" in American cuisine.[124] Yet in 2017, Vogue described the cuisine as "misunderstood and neglected";[125] SF Weekly in 2019, later described the cuisine as "marginal, underappreciated, and prone to weird booms-and-busts".[126]

Family

Filipino Americans undergo experiences that are unique to their own identities. These experiences derive from both the Filipino culture and American cultures individually and the dueling of these identities as well. These stressors, if great enough, can lead Filipino Americans into suicidal behaviors.[127] Members of the Filipino community learn early on about kapwa, which is defined as “interpersonal connectedness or togetherness.[128]”

With kapwa, many Filipino Americans have a strong sense of needing to repay their family members for the opportunities that they have been able to receive. An example of this is a new college graduate feeling the need to find a job that will allow them to financially support their family and themselves. This notion comes from “utang na loob,” defined as a debt that must be repaid to those who have supported the individual.[129]

With kapwa and utang na loob as strong forces enacting on the individual, there is an “all or nothing” mentality that is being played out. In order to bring success back to one's family, there is a desire to succeed for one's family through living out a family's wants as opposed to one's own true desires.[130] This can manifest as one entering a career path that they are not passionate in, but select in order to help support their family.[131]

Despite many of the stressors for these students deriving from family, it also becomes apparent that these are the reasons that these students are resilient. When family conflict rises in Filipino American families, there is a negative association with suicide attempts.[127] This suggests that though family is a presenting stressor in a Filipino American's life, it also plays a role for their resilience.[127] In a study conducted by Yusuke Kuroki, family connectedness, whether defined as positive or negative to each individual, served as one means of lowering suicide attempts.[127]

Media

The growth of publications for the masses in the Philippines accelerated during the American period.[132] Ethnic media serving Filipino Americans dates back to the beginning of the 20th Century.[133] In 1905, pensionados at University of California, Berkeley published The Filipino Students' Magazine.[134] One of the earliest Filipino American newspapers published in the United States, was the Philippine Independent of Salinas, California, which began publishing in 1921.[134] Newspapers from the Philippines, to include The Manila Times, also served the Filipino diaspora in the United States.[133] In 1961, the Philippine News was started by Alex Esclamado, which by the 1980s had a national reach and at the time was the largest English-language Filipino newspaper.[135] While many areas with Filipino Americans have local Filipino newspapers, one of the largest concentrations of these newspapers occur in Southern California.[136] Beginning in 1992, Filipinas began publication, and was unique in that it focused on American born Filipino Americans of the second and third generation.[133] Filipinas ended its run in 2010, however it was succeeded by Positively Filipino in 2012 which included some of the staff from Filipinas.[137] The Filipino diaspora in the United States are able to watch programming from the Philippines on television through GMA Pinoy TV and The Filipino Channel.[138][139]

Politics

Filipino Americans have traditionally been socially conservative,[140] particularly with "second wave" immigrants that fled the post-Marcos/pre-Duterte era from 1986-2015;[141] the first Filipino American elected to office was Peter Aduja.[142] In the 2004 U.S. presidential election Republican president George W. Bush won the Filipino American vote over John Kerry by nearly a two-to-one ratio,[143] which followed strong support in the 2000 election.[144] However, during the 2008 U.S. presidential election, Filipino Americans voted majority Democratic, with 50% to 58% of the community voting for President Barack Obama and 42% to 46% voting for Senator John McCain.[145][146] The 2008 election marked the first time that a majority of Filipino Americans voted for a Democratic presidential candidate.[147]

According to the 2012 National Asian American Survey, conducted in September 2012,[148] 45% of Filipinos were independent or nonpartisan, 27% were Republican, and 24% were Democrats.[146] Additionally, Filipino Americans had the largest proportions of Republicans among Asian Americans who have been polled, a position which is normally held by Vietnamese Americans, leading up to the 2012 election,[148] and had the lowest job approval opinion of Obama among Asian Americans.[148][149] In a survey of Asian Americans from thirty seven cities conducted by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, it found that of the Filipino American respondents, 65% of them voted for Obama.[150] According to an exit poll conducted by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, it found that 71% of responding Filipino Americans voted for Hillary Clinton during the 2016 general election.[151]

In a survey which was conducted by Asian Americans Advancing Justice in September 2020, of the 263 Filipino American respondents, 46% of them identified themselves as Democrats, 28% of them identified themselves as Republicans, and 16% of them identified themselves as independents.[152] According to interviews which were conducted by Anthony Ocampo, an academic, Filipino American supporters of Donald Trump cited their support for the former President based on their support for the building of a border wall, their support for tax cuts to businesses, their support for legal immigration, their belief in school choice, their opposition to LGBTQ rights, their opposition to abortion, their opposition to affirmative action, their antagonism towards the People's Republic of China, and their belief that Trump is not a racist.[153] There was an age divide among Filipino Americans, with older Filipino Americans more likely to support Trump or be Republicans, while younger and US-born Filipino Americans were more likely to support Biden or be Democrats.[154] In the 2020 presidential election, Philippine Ambassador Jose Manuel Romualdez alleges that 60% of Filipino Americans reportedly voted for Joe Biden.[155] Filipino Americans were the largest non-White ethnic group of those arrested in the 2021 United States Capitol attack.[156] Rappler alleges that the Filipino American media has heavily repeated QAnon conspiracies.[157] Rappler further alleges that, many Filipino Americans who voted for Trump, and adhere to QAnon, cite similar political leanings in the Philippines with regard to Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, and anti-Chinese sentiment because China has been building artificial reefs in the South China Sea near the Philippines in the 2010s and as a result, they have recently seen the Republican Party as being more hardline with regard to the Chinese government's actions.[158] Also Filipino Americans have a high rate of gun ownership in the United States, and are among the most pro-gun minority group in the U.S.[159]

Due to scattered living patterns, it is nearly impossible for Filipino American candidates to win an election solely based on the Filipino American vote.[160] Filipino American politicians have increased their visibility over the past few decades. Ben Cayetano (Democrat), former governor of Hawaii, became the first governor of Filipino descent in the United States. The number of Congressional members of Filipino descent doubled to numbers not reached since 1937, two when the Philippine Islands were represented by non-voting Resident Commissioners, due to the 2000 Senatorial Election. In 2009 three Congress-members claimed at least one-eighth Filipino ethnicity;[161] the largest number to date. Since the resignation of Senator John Ensign in 2011[162] (the only Filipino American to have been a member of the Senate), and Representative Steve Austria (the only Asian Pacific American Republican in the 112th Congress[163]) choosing not to seek reelection and retire,[164] Representative Robert C. Scott was the only Filipino American in the 113th Congress.[165] In the 116th United States Congress, Scott was joined by Rep. TJ Cox, bringing the number of Filipino Americans in Congress to two.[166] In the 117th United States Congress, Scott once again became the sole Filipino-American Representative after Cox was defeated in a rematch against David Valadao.[167]

Community matters

Immigration

The Citizenship Retention and Re-Acquisition Act of 2003 (Republic Act No. 9225) made Filipino Americans eligible for dual citizenship in the United States and the Philippines.[168] Overseas suffrage was first employed in the May 2004 elections in which Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo was reelected to a second term.[169]

By 2005, about 6,000 Filipino Americans had become dual citizens of the two countries.[170] One effect of this act was to allow Filipino Americans to invest in the Philippines through land purchases, which are limited to Filipino citizens, and, with some limitations, former citizens.[171]), vote in Philippine elections, retire in the Philippines, and participate in representing the Philippine flag. In 2013, for the Philippine general election there were 125,604 registered Filipino voters in the United States and Caribbean, of which only 13,976 voted.[172]

Dual citizens have been recruited to participate in international sports events including athletes representing the Philippines who competed in the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens,[173] and the Olympic Games in Beijing 2008.[174]

The Philippine government actively encourages Filipino Americans to visit or return permanently to the Philippines via the "Balikbayan" program and to invest in the country.[175]

Filipinos remain one of the largest immigrant groups to date with over 40,000 arriving annually since 1979.[176] The United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) has a preference system for issuing visas to non-citizen family members of U.S. citizens, with preference based generally on familial closeness. Some non-citizen relatives of U.S. citizens spend long periods on waiting lists.[177] Petitions for immigrant visas, particularly for siblings of previously naturalized Filipinos that date back to 1984, were not granted until 2006.[178] As of 2016[update], over 380 thousand Filipinos were on the visa wait list, second only to Mexico and ahead of India, Vietnam and China.[179] Filipinos have the longest waiting times for family reunification visas, as Filipinos disproportionately apply for family visas; this has led to visa petitions filed in July 1989 still waiting to be processed in March 2013.[180]

Illegal immigration

It has been documented that Filipinos were among those naturalized due to the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986.[181] In 2009, the Department of Homeland Security estimated that 270,000 Filipinos were "unauthorized immigrants". This was an increase of 70,000 from a previous estimate in 2000. In both years, Filipinos accounted for 2% of the total. As of 2009[update], Filipinos were the fifth-largest community of illegal immigrants behind Mexico (6.65 million, 62%), El Salvador (530,000, 5%), Guatemala (480,000, 4%), and Honduras (320,000, 3%).[182] In January 2011, the Department of Homeland Security estimate of "unauthorized immigrants" from the Philippines remained at 270,000.[183] By 2017, the number of Filipinos who were in the United States illegally increased to 310,000.[184] Filipinos who reside in the United States illegally are known within the Filipino community as "TnT's" (tago nang tago translated to "hide and hide").[185]

Mental health

Identity

Filipino Americans may be mistaken for members of other racial/ethnic groups, such as Latinos or Pacific Islanders;[186] this may lead to "mistaken" discrimination that is not specific to Asian Americans.[186] Filipino Americans additionally, have had difficulty being categorized, termed by one source as being in "perpetual absence".[187]

In the period, prior to 1946, Filipinos were taught that they were Americans, and they were also presented with an idealized image of America.[176] They had official status as United States nationals.[188] When they were ill-treated and discriminated against by other Americans, Filipinos were faced with the racism which existed during that period, which undermined these ideals.[189] Carlos Bulosan later wrote about this experience in America is in the Heart. Even pensionados, who immigrated on government scholarships,[176] were treated poorly.[189]

In Hawaii, Filipino Americans often have little identification with their heritage,[190] and it has been documented that many disclaim their ethnicity.[191] This may be due to the "colonial mentality," or the idea that Western ideals and physical characteristics are superior to their own.[192] Although categorized as Asian Americans, Filipino Americans have not fully embraced being part of this racial category due to marginalization by other Asian American groups and or the dominant American society.[193] This created a struggle within Filipino American communities over how far to assimilate.[194] The term "white-washed" has been applied to those who are seeking to assimilate further.[195]

Of the ten largest immigrant groups, Filipino Americans have the highest rate of assimilation.[196] with exception to the cuisine;[197] Filipino Americans have been described as the most "Americanized" of the Asian American ethnicities.[198] However, even though Filipino Americans are the second largest group among Asian Americans, community activists have described the ethnicity as "invisible," claiming that the group is virtually unknown to the American public,[199] and is often not seen as significant even among its members.[200] Another term for this status is forgotten minority.[201]

Considering most people now, when they hear the word "assimilate," they almost automatically think of converting. Although many Filipinos migrate to America to start a "new life," they still carry over some negative norms (Wolf 476).[202]

This description has also been used in the political arena, given the lack of political mobilization.[203] In the mid-1990s it was estimated that some one hundred Filipino Americans have been elected or appointed to public office. This lack of political representation contributes to the perception that Filipino Americans are invisible.[204]

The concept is also used to describe how the ethnicity has assimilated.[205] Few affirmative action programs target the group although affirmative action programs rarely target Asian Americans in general.[206] Assimilation was easier given that the group is majority religiously Christian, fluent in English, and have high levels of education.[207] The concept was in greater use in the past, before the post-1965 wave of arrivals.[208]

The term invisible minority has been used for Asian Americans as a whole,[209][210] and the term "model minority" has been applied to Filipinos as well as other Asian American groups.[211] Filipino critics allege that Filipino Americans are ignored in immigration literature and studies.[212]

As with fellow Asian Americans, Filipino Americans are viewed as "perpetual foreigners," even for those born in the United States.[213] This has resulted in physical attacks on Filipino Americans, as well as non-violent forms of discrimination.[214]

In college and high school campuses, many Filipino American student organizations put on annual Pilipino Culture Nights to showcase dances, perform skits, and comment on the issues such as identity and lack of cultural awareness due to assimilation and colonization.[215]

Filipino American gay, lesbian, transgender, and bisexual identities are often shaped by immigration status, generation, religion, and racial formation.[216]

Veterans

During World War II, some 250,000 to 400,000 Filipinos served in the United States Military,[217][218] in units including the Philippine Scouts, Philippine Commonwealth Army under U.S. Command, and recognized guerrillas during the Japanese Occupation. In January 2013, ten thousand surviving Filipino American veterans of World War II lived in the United States, and a further fourteen thousand in the Philippines,[219] although some estimates found eighteen thousand or fewer surviving veterans.[220]

The U.S. government promised these soldiers all of the benefits afforded to other veterans.[221] However, in 1946, the United States Congress passed the Rescission Act of 1946 which stripped Filipino veterans of the promised benefits.[222] One estimate claims that monies due to these veterans for back pay and other benefits exceeds one billion dollars.[218] Of the sixty-six countries allied with the United States during the war, the Philippines is the only country that did not receive military benefits from the United States.[200] The phrase "Second Class Veterans" has been used to describe their status.[200][223]

Many Filipino veterans traveled to the United States to lobby Congress for these benefits.[224] Since 1993, numerous bills have been introduced in Congress to pay the benefits, but all died in committee.[225] As recently as 2018, these bills have received bipartisan support.[226]

Representative Hanabusa submitted legislation to award Filipino Veterans with a Congressional Gold Medal.[227] Known as the Filipino Veterans of World War II Congressional Gold Medal Act, it was referred to the Committee on Financial Services and the Committee on House Administration.[228] As of February 2012 had attracted 41 cosponsors.[229] In January 2017, the medal was approved.[230]

There was a proposed lawsuit to be filed in 2011 by The Justice for Filipino American Veterans against the Department of Veterans Affairs.[231]

In the late 1980s, efforts towards reinstating benefits first succeeded with the incorporation of Filipino veteran naturalization in the Immigration Act of 1990.[200] Over 30,000 such veterans had immigrated, with mostly American citizens, receiving benefits relating to their service.[232]

Similar language to those bills was inserted by the Senate into the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009[233] which provided a one time payment of at least 9,000 USD to eligible non-US Citizens and US$15,000 to eligible US Citizens via the Filipino Veterans Equity Compensation Fund.[234] These payments went to those recognized as soldiers or guerrillas or their spouses.[235] The list of eligibles is smaller than the list recognized by the Philippines.[236] Additionally, recipients had to waive all rights to possible future benefits.[237] As of March 2011, 42 percent (24,385) of claims had been rejected;[238] By 2017, more than 22,000 people received about $226 million in one time payments.[239]

In the 113th Congress, Representative Joe Heck reintroduced his legislation to allow documents from the Philippine government and the U.S. Army to be accepted as proof of eligibility.[240] Known as H.R. 481, it was referred to the Committee on Veterans' Affairs.[241] In 2013, the U.S. released a previously classified report detailing guerrilla activities, including guerrilla units not on the "Missouri list".[242]

In September 2012, the Social Security Administration announced that non-resident Filipino World War II veterans were eligible for certain social security benefits; however an eligible veteran would lose those benefits if they visited for more than one month in a year, or immigrated.[243]

Beginning in 2008, a bipartisan effort started by Mike Thompson and Tom Udall an effort began to recognize the contributions of Filipinos during World War 2; by the time Barack Obama signed the effort into law in 2016, a mere fifteen thousand of those veterans were estimated to be alive.[244] Of those living Filipino veterans of World War II, there were an estimated 6,000 living in the United States.[245] Finally in October 2017, the recognition occurred with the awarding of a Congressional Gold Medal.[246] When the medal was presented by the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, several surviving veterans were at the ceremony.[247] The medal now resides in the National Museum of American History.[248]

Holidays

Congress established Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month in May to commemorate Filipino American and other Asian American cultures. Upon becoming the largest Asian American group in California, October was established as Filipino American History Month to acknowledge the first landing of Filipinos on October 18, 1587, in Morro Bay, California. It is widely celebrated by Fil-Ams.[249][250]

| Date | Name | Region |

|---|---|---|

| January | Winter Sinulog[251] | Philadelphia |

| April | PhilFest[252] | Tampa, FL |

| May | Asian Pacific American Heritage Month | Nationwide, USA |

| May | Asian Heritage Festival[253] | New Orleans |

| May | Filipino Fiesta and Parade[254] | Honolulu |

| May | FAAPI Mother's Day[255] | Philadelphia |

| May | Flores de Mayo[256] | Nationwide, USA |

| June | Philippine Independence Day Parade | New York City |

| June | Philippine Festival[257] | Washington, D.C. |

| June | Philippine Day Parade[258] | Passaic, NJ |

| June | Pista Sa Nayon[259] | Vallejo, CA |

| June | New York Filipino Film Festival at The ImaginAsian Theatre | New York City |

| June | Empire State Building commemorates Philippine Independence[260] | New York City |

| June | Philippine–American Friendship Day Parade[261] | Jersey City, NJ |

| June 12 | Fiesta Filipina[262] | San Francisco |

| June 12 | Philippine Independence Day | Nationwide, USA |

| June 19 | Jose Rizal's Birthday[263] | Nationwide, USA |

| June | Pagdiriwang[264] | Seattle |

| July | Fil-Am Friendship Day[265] | Virginia Beach, VA |

| July | Pista sa Nayon[266] | Seattle |

| July | Filipino American Friendship Festival[267] | San Diego |

| July | Philippine Weekend[268] | Delano, CA |

| August 15 to 16 | Philippine American Exposition[269] | Los Angeles |

| August 15 to 16 | Annual Philippine Fiesta[270] | Secaucus, NJ |

| August | Summer Sinulog[271] | Philadelphia |

| August | Historic Filipinotown Festival[272] | Los Angeles |

| August | Pistahan Festival and Parade[273] | San Francisco |

| September 25 | Filipino Pride Day[274] | Jacksonville, FL |

| September | Festival of Philippine Arts and Culture (FPAC)[275] | Los Angeles |

| September | AdoboFest[276] | Chicago |

| October | Filipino American History Month | Nationwide, USA |

| October | Filipino American Arts and Culture Festival (FilAmFest)[277] | San Diego |

| November | Chicago Filipino American Film Festival (CFAFF)[278] | Chicago |

| December 16 to 24 | Simbang Gabi Christmas Dawn Masses[279] | Nationwide, USA |

| December 25 | Pasko Christmas Feast[280] | Nationwide, USA |

| December 30 | Jose Rizal Day | Nationwide, USA |

Notable people

Footnotes

References

- ^ Bureau, US Census. "Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month: May 2021". Census.gov. Archived from the original on November 3, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "New Census data: More than 4 million Filipinos in the US". September 17, 2018. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c Melen McBride. "HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE OF FILIPINO AMERICAN ELDERS". Stanford University School of Medicine. Stanford University. Archived from the original on October 22, 2011. Retrieved June 8, 2011.,

- ^ a b "Statistical Abstract of the United States: page 47: Table 47: Languages Spoken at Home by Language: 2003" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 5, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2006.

- ^ a b Jonathan H. X. Lee; Kathleen M. Nadeau (2011). Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife. ABC-CLIO. pp. 333–334. ISBN 978-0-313-35066-5. Archived from the original on April 25, 2017. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Lee, Jonathan H. X.; Nadeau, Kathleen M. (2011). Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 334. ISBN 978-0-313-35066-5.Filipino Americans at Google Books

- ^ "Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths, Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation". The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. Pew Research Center. July 19, 2012. Archived from the original on August 11, 2018. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

Religious Affiliations Among U.S. Asian American Groups - Filipino: 89% Christian (21% Protestant (12% Evangelical, 9% Mainline), 65% Catholic, 3% Other Christian), 1% Buddhist, 0% Muslim, 0% Sikh, 0% Jain, 2% Other religion, 8% Unaffiliated

[failed verification]

"Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths". The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. Pew Research Center. July 19, 2014. Archived from the original on April 28, 2014. Retrieved March 15, 2017.Filipino Americans: 89% All Christian (65% Catholic, 21% Protestant, 3% Other Christian), 8% Unaffiliated, 1% Buddhist

- ^ Mercene, Floro L. (2007). Manila Men in the New World: Filipino Migration to Mexico and the Americas from the Sixteenth Century. The University of the Philippines Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-971-542-529-2. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

Rodis 2006 - ^ Rodel Rodis (October 25, 2006). "A century of Filipinos in America". Inquirer. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ "Labor Migration in Hawaii". UH Office of Multicultural Student Services. University of Hawaii. Archived from the original on June 3, 2009. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

- ^ "Treaty of Paris ends Spanish–American War". History.com. A&E Television Networks, LLC. Archived from the original on May 12, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

Puerto Rico and Guam were ceded to the United States, the Philippines were bought for $20 million, and Cuba became a U.S. protectorate.

Rodolfo Severino (2011). Where in the World is the Philippines?: Debating Its National Territory. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 10. ISBN 978-981-4311-71-7. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

Muhammad Munawwar (February 23, 1995). Ocean States: Archipelagic Regimes in the Law of the Sea. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-0-7923-2882-7. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

Thomas Leonard; Jurgen Buchenau; Kyle Longley; Graeme Mount (January 30, 2012). Encyclopedia of U.S. - Latin American Relations. SAGE Publications. p. 732. ISBN 978-1-60871-792-7. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017. - ^ Bureau, US Census. "Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month: May 2021". Census.gov. Archived from the original on November 3, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ "ASIAN ALONE OR IN ANY COMBINATION BY SELECTED GROUPS (TableID: B02018)". data.census.gov. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ Bureau, INQUIRER NET U. S. (November 15, 2019). "Filipino population in U.S. now nearly 4.1 million -- new Census data". INQUIRER.net USA. Archived from the original on December 23, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- ^ "Fil-Am: abbreviation Filipino American." Archived November 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, allwords.com Archived November 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Date accessed: April 29, 2011

Joaquin Jay Gonzalez III; Roger L. Kemp (February 18, 2016). Immigration and America's Cities: A Handbook on Evolving Services. McFarland. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-7864-9633-4. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

Stanley I. Thangaraj; Constancio Arnaldo; Christina B. Chin (April 5, 2016). Asian American Sporting Cultures. NYU Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-4798-4016-8. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2018. - ^ Jon Sterngass (2007). Filipino Americans. Infobase Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-4381-0711-0. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- ^ Howe, Marvine (February 26, 1986). "IN U.S., PHILIPPINE-AMERICANS REJOICE". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 15, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

Shulman, Robin (August 16, 2001). "Many Filipino Immigrants Are Dropping Anchor in Oxnard". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 15, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

Allen, James P. (1977). "Recent Immigration from the Philippines and Filipino Communities in the United States". Geographical Review. 67 (2): 195–208. doi:10.2307/214020. JSTOR 214020.

American Chamber of Commerce of the Philippines (1921). Journal. p. 22. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- ^ Dawn Bohulano Mabalon (May 29, 2013). Little Manila Is in the Heart: The Making of the Filipina/o American Community in Stockton, California. Duke University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8223-9574-4. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ Marina Claudio-Perez (October 1998). "Filipino Americans" (PDF). The California State Library. State of California. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 30, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

Filipino Americans are often shortened into Pinoy Some Filipinos believe that the term Pinoy was coined by the early Filipinos who came to the United States to distinguish themselves from Filipinos living in the Philippines. Others claim that it implies "Filipino" thoughts, deeds and spirit.

- ^ Madarang, Catalina Ricci S. (June 24, 2020). "Is 'Filipinx' a correct term to use? Debate for 'gender-neutral' term for Filipino sparked anew". Interaksyon. Philippines: Philippine Star. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

Chua, Ethan (September 6, 2020). "Filipino, Fil-Am, Filipinx? Reflections on a National Identity Crisis". Medium. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

Aguilar, Delia D.; San Juan, E. Jr. (June 10, 2020). "Problematizing The Name "Filipinx": A Colloquy". Counter Currents. India: Binu Mathew. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

Grana, Rhia D. (September 7, 2020). "The new word for 'Filipino' has just been included in a dictionary—and many are not happy". ABS-CBN News. Philippines. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

Cabigao, Kate (January 6, 2021). "Are You Filipino or Filipinx?". Vice. New York. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2021. - ^ Loni Ding (2001). "Part 1. COOLIES, SAILORS AND SETTLERS". NAATA. PBS. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2011.

Most people think of Asians as recent immigrants to the Americas, but the first Asians—Filipino sailors—settled in the bayous of Louisiana a decade before the Revolutionary War.

- ^ The End of Chino Slavery (Chapter 7) - Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107477841.008. ISBN 9781107063129. Archived from the original on November 2, 2022. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ Bonus, Rick (2000). Locating Filipino Americans: Ethnicity and the Cultural Politics of Space. Temple University Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-56639-779-7. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

"Historic Site". Michael L. Baird. Archived from the original on June 24, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2009. - ^ Eloisa Gomez Borah (1997). "Chronology of Filipinos in America Pre-1989" (PDF). Anderson School of Management. University of California, Los Angeles. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 8, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2012.

- ^ Williams, Rudi (June 3, 2005). "DoD's Personnel Chief Gives Asian-Pacific American History Lesson". American Forces Press Service. U.S. Department of Defense. Archived from the original on June 15, 2007. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ Loni Ding (2001). "Part 1. COOLIES, SAILORS AND SETTLERS". NAATA. PBS. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

Some of the Filipinos who left their ships in Mexico ultimately found their way to the bayous of Louisiana, where they settled in the 1760s. The film shows the remains of Filipino shrimping villages in Louisiana, where, eight to ten generations later, their descendants still reside, making them the oldest continuous settlement of Asians in America.

Loni Ding (2001). "1763 FILIPINOS IN LOUISIANA". NAATA. PBS. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved May 19, 2011.These are the "Louisiana Manila men" with presence recorded as early as 1763.

Ohamura, Jonathan (1998). Imagining the Filipino American Diaspora: Transnational Relations, Identities, and Communities. Studies in Asian Americans Series. Taylor & Francis. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8153-3183-4. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2012. - ^ "Ranching". National Geographic. November 8, 2011. Archived from the original on April 15, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ Jim Zwick (March 4, 1996). "Remembering St. Louis, 1904: A World on Display and Bontoc Eulogy". Syracuse University. Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved May 25, 2007.

- ^ "The Passions of Suzie Wong Revisited, by Rev. Sequoyah Ade". Aboriginal Intelligence. January 4, 2004. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- ^ a b "Filipino-Americans in the U.S." Filipino-American Community of South Puget Sound. 2018. Archived from the original on February 4, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ "Introduction, Filipino Settlements in the United States" (PDF). Filipino American Lives. Temple University Press. March 1995. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 28, 2014. Retrieved April 19, 2009.

- ^ "Introduction, Filipino Settlements in the United States" (PDF). Filipino American Lives. Temple University Press. March 1995. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 28, 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ^ "Background Note: Philippines". Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs. United States Department of State. January 31, 2011. Archived from the original on January 22, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

There are an estimated four million Americans of Philippine ancestry in the United States, and more than 300,000 American citizens in the Philippines.

- ^ "Race Reporting for the Asian Population by Selected Categories: 2010". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2012.

- ^ Public Information Office (November 9, 2015). "Census Bureau Statement on Classifying Filipinos". United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on May 26, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

Joan L. Holup; Nancy Press; William M. Vollmer; Emily L. Harris; Thomas M. Vogt; Chuhe Chen (September 2007). "Performance of the U.S. Office of Management and Budget's Revised Race and Ethnicity Categories in Asian Populations". International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 31 (5): 561–573. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2007.02.001. PMC 2084211. PMID 18037976. - ^ Jonathan Y. Okamura (January 11, 2013). Imagining the Filipino American Diaspora: Transnational Relations, Identities, and Communities. Routledge. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-136-53071-5. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ Levine, Michael (May 25, 2011). "Filipinos Overtake Japanese As Top Hawaii Group". Honolulu Civil Beat. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- ^ NW, 1615 L. St; Suite 800Washington; Inquiries, DC 20036USA202-419-4300 | Main202-857-8562 | Fax202-419-4372 | Media. "Top 10 U.S. metropolitan areas by Filipino population, 2015". Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Filipinos | Data on Asian Americans". Archived from the original on March 6, 2022. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/RAD-PhilippinesII.pdf Archived January 25, 2022, at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Racial Wealth Snapshot: Asian Americans | Prosperity Now". Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/AAPI-LaborMkt.pdf Archived March 1, 2022, at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/RAD-PhilippinesII.pdf Archived January 25, 2022, at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "A Demographic Profile of Doctors and Nurses". February 1998. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- ^ Yengoyan, Aram A. (2006). "Christianity and Austronesian Transformations: Church, Polity, and Culture in the Philippines and the Pacific". In Bellwood, Peter; Fox, James J.; Tryon, Darrell (eds.). The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. Comparative Austronesian Series. Australian National University E Press. p. 360. ISBN 978-1-920942-85-4.

Abinales, Patricio N.; Amoroso, Donna J. (2005). State And Society In The Philippines. State and Society in East Asia Series. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-7425-1024-1. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

Natale, Samuel M.; Rothschild, Brian M.; Rothschield, Brian N. (1995). Work Values: Education, Organization, and Religious Concerns. Volume 28 of Value inquiry book series. Rodopi. p. 133. ISBN 978-90-5183-880-0. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

Munoz, J. Mark; Alon, Ilan (2007). "Entrepreneurship among Filipino immigrants". In Dana, Leo Paul (ed.). Handbook of Research on Ethnic Minority Entrepreneurship: A Co-evolutionary View on Resource Management. Elgar Original Reference Series. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 259. ISBN 978-1-84720-996-2. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2013. - ^ Irisa Ona (April 15, 2015). "Fluidity of Filipino American Identity". Engaged Learning. Southern Methodist University. Archived from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

The Historic Filipinotown Health Network; Semics LLC (November 2007). "Culture and Health Among Filipinos and Filipino-Americans in Central Los Angeles" (PDF). Search to Involve Pilipino Americans. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017. - ^ Bautista, Amanda Vinluan (May 2014). Filipino American Culture And Traditions: An Exploratory Study (PDF) (Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Social Work). California State University, Stanislaus. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ See, Sarita Echavez (2009). The Decolonized Eye: Filipino American Art and Performance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-5319-5. Archived from the original on April 22, 2017. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- ^ Tyner, James A. (2007). "Filipinos: The Invisible Ethnic Community". In Miyares, Ines M.; Airress, Christopher A. (eds.). Contemporary Ethnic Geographies in America. G - Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 264–266. ISBN 978-0-7425-3772-9.Filipino Americans at Google Books

- ^ Carlo Osi (March 26, 2009). "Filipino cuisine on US television". Mind Feeds. Inquirer Company. Archived from the original on August 26, 2012. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

In the United States, the Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese cultural groups often bond for organizational purposes, while Filipinos in general have not. Ethnically Filipino Americans are divided into Pampangeno, Ilocano, Cebuano, Tagalog, and so forth.

- ^ Guevarra, Rudy P. Jr. (2008). ""Skid Row": Filipinos, Race and the Social Construction of Space in San Diego" (PDF). The Journal of San Diego History. 54 (1). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 12, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

Lagierre, Michel S. (2000). The global ethnopolis: Chinatown, Japantown, and Manilatown in American society. New York, New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-312-22612-1. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2019. - ^ Sterngass, Jon (2006). Filipino Americans. New York, New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-7910-8791-6. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ Melendy, H. Brett. "Filipino Americans." Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, edited by Gale, 3rd edition, 2014. Credo Reference, http://lpclibrary.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/galegale/filipino_americans/0?institutionId=8558 Archived February 13, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dudzik, Beatrix; Go, Matthew C. (January 2019). "Classification Trends Among Modern Filipino Crania Using Fordisc 3.1". Forensic Anthropology. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Posadas, Barbara Mercedes (1999). The Filipino Americans. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-313-29742-7. Filipino Americans at Google Books

- ^ Harold Hisona (July 14, 2010). "The Cultural Influences of India, China, Arabia, and Japan". Philippine Almanac. Philippine Daily. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

Varatarācaṉ, Mu (1988). A History of Tamil Literature. Histories of literature. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. pp. 1–17. Archived from the original on April 13, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2013. - ^ Leupp, Gary P. (2003). Interracial Intimacy in Japan. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 52–3. ISBN 978-0-8264-6074-5.

- ^ a b Bryan, One (2003). Filipino Americans. ABDO. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-57765-988-4.Filipino Americans at Google Books

- ^ Hugo Lopez, Mark; Manuel Krogstad, Jens; Passel, Jeffrey (September 23, 2021). "Who is Hispanic?". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on September 29, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

People with ancestries in Brazil, Portugal and the Philippines do not fit the federal government's official definition of "Hispanic" because the countries are not Spanish-speaking. For the most part, people who trace their ancestry to these countries are not counted as Hispanic by the Census Bureau, usually because most do not identify as Hispanic when they fill in their census forms. Only about 2% of immigrants from Brazil do so, as do 1% of immigrants from Portugal and 1% from the Philippines, according to the 2019 American Community Survey. These patterns likely reflect a growing recognition and acceptance of the official definition of Hispanics. In the 1980 census, 18% of Brazilian immigrants and 12% of both Portuguese and Filipino immigrants identified as Hispanic. But by 2000, the shares identifying as Hispanic dropped to levels closer to those seen today.

Sadural, Epifanio (September 20, 2017). "Dear Filipinos: We're Not Latino, We're Southeast Asian, Get Over It". The Odyssey. Archived from the original on March 4, 2022. Retrieved March 4, 2022. - ^ Kramer, Paul (2006). "Race-Making and Colonial Violence in the U.S. Empire: The Philippine-American War as Race War". Diplomatic History. 30 (2): 169–210. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.2006.00546.x.

- ^ Jeffrey S. Passel; Paul Taylor (May 29, 2009). "Who's Hispanic?". Hispanic Trends. Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on March 4, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

In the 1980 Census, about one in six Brazilian immigrants and one in eight Portuguese and Filipino immigrants identified as Hispanic. Similar shares did so in the 1990 Census, but by 2000, the shares identifying as Hispanic dropped to levels close to those seen today.

Westbrook, Laura (2008). "Mabuhay Pilipino! (Long Life!): Filipino Culture in Southeast Louisiana". Louisiana Folklife Program. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation & Tourism. Archived from the original on May 18, 2018. Retrieved March 16, 2017. - ^ Kevin R. Johnson (2003). Mixed Race America and the Law: A Reader. NYU Press. pp. 226–227. ISBN 978-0-8147-4256-3. Archived from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

Yen Le Espiritu (February 11, 1993). Asian American Panethnicity: Bridging Institutions and Identities. Temple University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-56639-096-5. Archived from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017. - ^ Sri Kuhnt-Saptodewo; Volker Grabowsky; Martin Grossheim (1997). "Colonialism, Conflict and Cultural Identity in the Philippines". Nationalism and Cultural Revival in Southeast Asia: Perspectives from the Centre and the Region. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 247. ISBN 978-3-447-03958-1. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

Garcia, Gabriel (September 29, 2016). "Filipinos helped shape America of today". Anchorage Daily News. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

Paul A. Rodell (2002). Culture and Customs of the Philippines. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-313-30415-6. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

Barrameda, Ina (May 8, 2018). "Confessions of an Inglisera". Buzzfeed News. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2019. - ^ Esmaquel II, Paterno (October 21, 2016). "Envoy reminds PH: 43% of OFW remittances come from US". Rappler. Philippines. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ Joaquin Jay Gonzalez (February 1, 2009). Filipino American Faith in Action: Immigration, Religion, and Civic Engagement. NYU Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-8147-3297-7. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ Jonathan Y. Okamura (January 11, 2013). "Imagining the Filipino American Diaspora". Imagining the Filipino American Diaspora: Transnational Relations, Identities, and Communities. Routledge. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-136-53071-5. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ Orendian, Simone (July 17, 2013). "Remittances Play Significant Role in Philippines". VOA. Archived from the original on June 5, 2017. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

Victoria P. Garchitoreno (May 2007). Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience (PDF) (Report). Convention on Biological Diversity. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

Taylor, Marisa (March 27, 2006). "Filipinos follow their hearts home". The Virginian-Pilot. Norfolk, Virginia. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2019. - ^ a b Eric J. Pido (May 5, 2017). Migrant Returns: Manila, Development, and Transnational Connectivity. Duke University Press. pp. 153–. ISBN 978-0-8223-7312-4. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ Garcia, Nelson (April 23, 2017). "Special: Traveling to find lost heritage". KUSA. Denver. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

Tagala, Don (September 27, 2018). ""Diskubre" New Travel Reality Series Brings Young Filipino American Cast Overseas". Balitang American. Redwood Shores, California. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

Faye Caronan (May 30, 2015). Legitimizing Empire: Filipino American and U.S. Puerto Rican Cultural Critique. University of Illinois Press. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-252-09730-0. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2019. - ^ Shyong, Frank (April 28, 2018). "These boxes are a billion-dollar industry of homesickness for Filipinos overseas". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

Diana Mata-Codesal; Maria Abranches; Karina Hof (August 9, 2017). "A Hard Look at the Balikbayan Box: The Philippine Disapora's Export Hospitality". Food Parcels in International Migration: Intimate Connections. Springer. pp. 94–114. ISBN 978-3-319-40373-1. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2019. - ^ Fong, Rowena (2004). Culturally competent practice with immigrant and refugee children and families. Guilford Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-57230-931-9. Archived from the original on July 28, 2009. Retrieved May 14, 2009.

Andres, Tomas Quintin D. (1998). People empowerment by Filipino values. Rex Bookstore, Inc. p. 17. ISBN 978-971-23-2410-9. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved May 14, 2009.

Pinches, Michael (1999). Culture and Privilege in Capitalist Asia. Routledge. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-415-19764-9.Filipino Americans at Google Books

Roces, Alfredo; Grace Roces (1992). Culture Shock!: Philippines. Graphic Arts Center Pub. Co. ISBN 978-1-55868-089-0. Filipino Americans at Google Books - ^ J. Nicole Stevens (June 30, 1999). "The History of the Filipino Languages". Linguistics 450. Brigham Young University. Archived from the original on May 2, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

The Americans began English as the official language of the Philippines. There were many reasons given for this change. Spanish was still not known by very many of the native people. As well, when Taft's commission (which had been established to continue setting up the government in the Philippines) asked the native people what language they wanted, they asked for English (Frei, 33).

Stephen A. Wurm; Peter Mühlhäusler; Darrell T. Tryon (January 1, 1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas: Vol I: Maps. Vol II: Texts. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 272–273. ISBN 978-3-11-081972-4. Archived from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017. - ^ Don T. Nakanishi; James S. Lai (2003). Asian American Politics: Law, Participation, and Policy. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-7425-1850-6. Archived from the original on January 7, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Bankston III, Carl L. (2006). "Filipino Americans". In Gap Min, Pyong (ed.). Asian Americans: Contemporary Trends and Issues. Sage focus editions. Vol. 174. Pine Forge Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-4129-0556-5. Archived from the original on May 9, 2011. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Osalbo, Jennifer Guiang (Spring 2011). "Education" (PDF). Filipino American Identity Development and its Relation to Heritage Language Loss (Master of Arts). California State University, Sacramento. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 12, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

Guevarra, Ericka Cruz (February 26, 2016). "For Some Filipino-Americans, Language Barriers Leave Culture Lost in Translation". KQED. San Francisco Bay Area. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

Ph.D., Kevin L. Nadal (July 15, 2010). Filipino American Psychology: A Collection of Personal Narratives. AuthorHouse. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-4520-0190-6. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved July 3, 2019. - ^ Ryan, Camille (August 2013). Language Use in the United States: 2011 (PDF) (Report). United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey Reports. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 5, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- ^ Nucum, Jun (August 2, 2017). "So what if Tagalog is 3rd most spoken language in 3 US states?". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- ^ "Language Requirements" (PDF). Secretary of State. State of California. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

- ^ Malabonga, Valerie. (2019). Heritage Voices: Programs - Tagalog Archived September 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

Blancaflor, Saleah; Escobar, Allyson (October 30, 2018). "Filipino cultural schools help bridge Filipino Americans and their heritage". NBC News. Archived from the original on March 2, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2019. - ^ "Ilokano Language & Literature Program". Communications department. University of Hawaii at Manao. 2008. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- ^ Joyce Newman Giger (April 14, 2014). Transcultural Nursing: Assessment and Intervention. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-323-29328-0. Archived from the original on January 7, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Potowski, Kim (2010). Language Diversity in the USA. Cambridge University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-521-76852-8. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

Ruether, Rosemary Radford, ed. (2002). Gender, Ethnicity, and Religion: Views from the Other Side. Fortress Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-8006-3569-5. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

Axel, Joseph (January 2011). Language in Filipino America (PDF) (Doctoral dissertation). Arizona State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2017. - ^ "Leave the Filipinx Kids Alone". Esquiremag.ph. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ Toledo, John (September 15, 2020). "Filipino or Filipinx?". INQUIRER.net. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ "Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths". Pew Research Center. Pew Research Center. July 19, 2012. Archived from the original on July 16, 2013. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- ^ a b Professor Susan Russell. "Christianity in the Philippines". Center for Southeast Asian Studies. Northern Illinois University. Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ^ Cindy Kleinmeyer (June 2004). "Religions in Southeast Asia" (PDF). Center for Southeast Asian Studies. Northern Illinois University. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 3, 2012. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

Gonzales, Joseph; Sherer, Thomas E. (2004). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Geography. Penguin. p. 334. ISBN 978-1-59257-188-8. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2012. - ^ a b c Nadal, Kevin (2011). Filipino American Psychology: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice. John Wiley & Sons. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-118-01977-1. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ^ Mark Juergensmeyer (August 25, 2011). The Oxford Handbook of Global Religions. Oxford University Press. p. 383. ISBN 978-0-19-976764-9. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

Bellwood, Peter; Fox, James J.; Tyron, Darrell; Yengoyan, Aram A. (April 1995). "America and Protestantism in the Philippines". The Austronesians. Australia National University. ISBN 978-0731521326. Archived from the original on February 17, 2017. Alt URL Archived March 26, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

America. America Press. 1913. p. 8. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

Catholic World. Paulist Fathers. 1902. p. 847. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2018. - ^ a b Laderman, Gary; León, Luís D. (2003). Religion and American Cultures: An Encyclopedia of Traditions, Diversity, and Popular Expressions, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-57607-238-7. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ^ Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. 1901. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ Thema Bryant-Davis; Asuncion Miteria Austria; Debra M. Kawahara; Diane J. Willis Ph.D. (September 30, 2014). Religion and Spirituality for Diverse Women: Foundations of Strength and Resilience: Foundations of Strength and Resilience. ABC-CLIO. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-4408-3330-4. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ Jonathan H. X. Lee; Kathleen M. Nadeau (2011). Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife. ABC-CLIO. p. 357. ISBN 978-0-313-35066-5. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

Sucheng Chan (1991). Asian Americans: an interpretive history. Twayne. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8057-8426-8. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2018. - ^ Thomas A. Tweed (June 28, 2011). America's Church: The National Shrine and Catholic Presence in the Nation's Capital. Oxford University Press. pp. 222–224. ISBN 978-0-19-983148-7. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

Broadway, Bill (August 2, 1997). "50-ton Symbol of Unity to Adorn Basilica". Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 22, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2018. - ^ "Chapel of San Lorenzo Ruiz". Philippine Apostolate / Archdiocese of new York. Archived from the original on August 3, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2007.

Fr. Diaz (August 1, 2005). "Church of Filipinos opens in New York". The Manila Times. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2012. - ^ Mark Gray; Mary Gautier; Thomas Gaunt (June 2014). "Cultural Diversity in the Catholic Church in the United States" (PDF). United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

Some 76 percent of Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander Catholics are estimated to self-identify as Filipino (alone and in combinations with other identities).

- ^ Lipka, Michael (January 9, 2015). "5 facts about Catholicism in the Philippines". Fact Tank. Pew Research. Archived from the original on January 10, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ Tony Carnes; Fenggang Yang (May 1, 2004). Asian American Religions: The Making and Remaking of Borders and Boundaries. NYU Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8147-7270-6. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ Stephen M. Cherry (January 3, 2014). Faith, Family, and Filipino American Community Life. Rutgers University Press. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-0-8135-7085-3. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ Gardner, F. (1906). The Journal of American Folklore: Philippine (Tagalog) Superstitions. American Folklore Society.

- ^ Bautista, A. V. (2014). Filipino American Culture and Traditions: An Exploratory Study. California State University.

- ^ a b Cowen, Tyler (2012). An Economist Gets Lunch: New Rules for Everyday Foodies. Penguin. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-101-56166-9. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

Yet, according to one source, there are only 481 Filipino restaurants in the country;

- ^ a b c Shaw, Steven A. (2008). Asian Dining Rules: Essential Strategies for Eating Out at Japanese, Chinese, Southeast Asian, Korean, and Indian Restaurants. New York, New York: HarperCollins. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-06-125559-5. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ a b c Dennis Clemente (July 1, 2010). "Where is Filipino food in the US marketplace?". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on March 18, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ^ Alice L. McLean (April 28, 2015). Asian American Food Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-56720-690-6. Archived from the original on March 21, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ^ Woods, Damon L. (2006). The Philippines: a global studies handbook. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 250. ISBN 978-1-85109-675-6. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

Jennifer Jensen Wallach; Lindsey R. Swindall; Michael D. Wise (February 12, 2016). The Routledge History of American Foodways. Routledge. p. 402. ISBN 978-1-317-97522-9. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017. - ^ Sokolov, Raymond (1993). Why We Eat What We Eat: How Columbus Changed the Way the World Eats. New York, New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-671-79791-1. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ "A Brief History of Filipinos in Hawaii". Center for Philippine Studies. University of Hawaii-Manoa. 2010. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ^ Carpenter, Robert; Carpenter, Robert E.; Carpenter, Cindy V. (2005). Oahu Restaurant Guide 2005 With Honolulu and Waikiki. Havana, Illinois: Holiday Publishing Inc. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-931752-36-7. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ Johnson-Kozlow, Marilyn; Matt, Georg; Rock, Cheryl; de la Rosa, Ruth; Conway, Terry; Romero, Romina (June 25, 2011). "Assessment of Dietary Intakes of Filipino-Americans: Implications for Food Frequency Questionnaire Design". Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 43 (6): 505–510. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2010.09.001. PMC 3204150. PMID 21705276.

- ^ KATRINA STUART SANTIAGO (June 8, 2011). "Balut as Pinoy pride". GMA. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 2, 2011.

The balut is one claim to fame we're uncertain about, seeing as it is equated with hissing cockroaches on Fear Factor. Talk about bringing us back to the dark ages of being the exotic and barbaric brown siblings of America.

- ^ Carlo Osi (March 26, 2006). "Filipino cuisine on US television". Global Nation. Archived from the original on August 26, 2012. Retrieved July 2, 2011.

- ^ Keli Dailey (February 9, 2012). "Andrew Zimmern's eating through San Diego". San Diego Union Tribune. Archived from the original on May 2, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

"Tita's sisig, best I have ever tasted . San Diego Philippine (sic) food is crazy good," he tweeted.

- ^ a b Amy Scattergood (February 25, 2011). "Off the menu". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ Laudan, Rachel (1996). The food of Paradise: exploring Hawaii's culinary heritage. Seattle: University of Hawaii Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-8248-1778-7. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ Melanie Henson Narciso (2005). Filipino Meal Patterns in the United States of America (PDF) (Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree). University of Wisconsin-Stout. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ Kristy, Yang (July 30, 2011). "Filipino Food: At Least One Reason to Envy California". Dallas Observer. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2012.