National Library of China

| National Library of China | |

|---|---|

| 中国国家图书馆 | |

National Library of China North Complex | |

| |

| Location | Beijing, China |

| Type | National library |

| Established | September 1909 |

| Collection | |

| Size | 41 million (December 2020)[1] |

| Access and use | |

| Access requirements | Open to the public |

| Population served | 1.4 billion |

| Other information | |

| Director | Wang Chunfa (since 2017) |

| Website | nlc.cn |

| National Library of China | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 中国国家图书馆 | ||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國國家圖書館 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The National Library of China (Chinese: 中国国家图书馆; NLC) is the national library of the People's Republic of China, located in Beijing, China, and is one of the largest libraries in the world. It contains over 41 million items as of December 2020.[1][2] It holds the largest collection of Chinese literature and historical documents in the world[3] and covers an area of 280,000 square meters.[4] The National Library is a public welfare institution sponsored by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

The collections of the National Library have inherited the royal collections since the Southern Song Dynasty and private collections since the Ming and Qing dynasties. The oldest collections can be traced back to the oracle bones of Yin Ruins more than 3,000 years ago.[5]

The National Library is a major research and public library, with items in 123 languages[6] and in many formats, both print and digital: books, manuscripts, journals, newspapers, magazines, sound and music recordings, videos, play-scripts, patents, databases, maps, stamps, prints, drawings. As of December 2020, the collection contains more than 41 million volumes and is growing at a rate of one million volumes per year.[7] The total amount of digital resources exceeds 1000TB and is growing at a rate of 100TB per year.[8]

The National Library of China was initially founded as the Imperial Peking Library by the Qing government in 1909. After several name changes and administrative alternation, it was renamed the National Library of China in 1999.[9] The National Library now consists of the South Complex, the North Complex, the Ancient Books Hall,[10] the Children's Hall, and seventeen dispatched research libraries to the central government's various departments and the Academy of Military Sciences.[11][12]

History

Background

The earliest Chinese references to Western-style public libraries were by Lin Zexu in the Sizhou Zhi (四洲志; 1839) and Wei Yuan in the Illustrated Treatise on the Maritime Kingdoms (first ed., 1843), both of which were translations from Western books.[13]

In the late nineteenth century, in response to several military defeats against western powers, the government of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) sent several missions abroad to study western culture and institutions. Several members of the first Chinese diplomatic mission, which sold to the United States, England, France, and other countries from 1111 to 1870 [clarification needed], recorded their views of western libraries, noting that they attracted a large number of readers.[14] Journalist Liang Qichao (1873–1929), who became a prominent exiled intellectual after the failure of the Hundred Days' Reform in 1898, wrote about the Boston Public Library and the University of Chicago Library, praising their openness to the public and the virtue of readers who did not steal the books that had been lent to them.[15] Dai Hongci (戴鸿慈; 戴鴻慈), a member of another Qing mission sent abroad to study modern constitutions, noted the efficacy of book borrowing at the Library of Congress.[16]

Foundation

In 1906, the governor of Hunan province Pang Hongshu memorialized to the throne to announce he had completed preparations for the creation of a provincial library in Changsha.[17] In 1908 and 1909, high officials from the provinces of Fengtian, Shandong, Shanxi, Zhejiang and Yunnan petitioned the Imperial Court asking for permission to establish public libraries in their respective jurisdictions.[17] In response, on 2 May 1909, the Qing Ministry of Education (学部; 學部; Xuébù) announced plans to open libraries in every province of the country.[18]

On 9 September 1909, Zhang Zhidong, a long-time leader of the Self-Strengthening movement who had been viceroy of Huguang and was now serving on the powerful Grand Council, memorialized to request the foundation of a library in China's capital.[19] Foundation of the library was approved by imperial edict that same day.[20] The institution was originally called the Imperial Library of Peking or Metropolitan Library (京师图书馆; 京師圖書館; Jīngshī Túshūguǎn).[21] Lu Xun and other famous scholars have made great efforts for its construction.

Philologist and bibliographer Miao Quansun (缪荃荪; 繆荃蓀; 1844–1919), who had overseen the founding of Jiangnan Library in Nanjing two years earlier, was called in to administer the new establishment. As in Jiangnan, his assistant Chen Qingnian took charge of most of the management.[22]

A private proposal made by Luo Zhenyu in the early 1900s stated that the library should be located in a place protected from both fire and floods, and at some distance from noisy markets. Following these recommendations, the Ministry of Education first chose the Deshengmen neighborhood inside the northern Beijing city wall, a quiet area with lakes. But this plan would have required purchasing several buildings. For lack of funds, Guanghua Temple (广化寺; 廣化寺) was chosen as the library's first site. Guanghua Temple was a complex of Buddhist halls and shrines located near the northern bank of the Shichahai, but inconveniently located for readers, and too damp for long-term book storage. The Imperial Library of Peking would remain there until 1917.[23] In 1916, the Ministry of education ordered the library, every published book should be registered in ministry of interior and all collected by library, The function of national library begins to manifest.[24]

Later history

The National Peking Library opened to the public on 27 August 1912, a few months after the abdication of Puyi (r. 1908–12), the last emperor of the Qing dynasty.[25] From then on, it was managed by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China.[25] The day before the library's opening, its new chief librarian Jiang Han (江瀚: 1853–1935) argued that the National Peking Library was a research library and recommended the opening of a new library with magazines and new publications that could attract a more popular readership.[26] In June 1913, such a Branch Library was opened outside Xuanwumen Gate, and more than 2,000 books were transferred there from the main library.[27] On 29 October 1913, because Guanghua Temple proved too small and inaccessible, the main library itself was closed, pending the choice of a new site.[28]

The Library charged one copper coin as a reading fee, whereas the Tianjin Library charged twice as much and the Shandong public library charged three coins.[29] At first, readers could not borrow books, but sometime before 1918 borrowing became allowed.[30]

In 1916, the Ministry of Education (MOE) of the Republic of China ordered that a copy of every Chinese publication should be deposited at the Metropolitan Library after being registered with the Copyright Bureau.[31]

After the Northern Expedition of Kuomintang in 1928, the name of Beijing was changed to Beiping (Peiping) to emphasize that the capital had moved to Nanjing (jīng lit. translating to capital). The National Peking Library therefore changed its name to the National Peiping Library and became the co-national library with the National Central Library in Nanjing. In 1931, the new library house in Wenjin Street near the Beihai Park opened. After the People's Republic of China was officially established in October 1949 and Beijing once again became the capital, the National Peiping Library was renamed National Peking Library. In 1951, the Ministry of Culture declared that its official English name would now be Peking Library.[32]

The library established a materials exchange program with the C.V. Starr East Asian Library of Columbia University in 1963, through which it was able to acquire materials from the West; one such transaction during the first months of the program involved the exchange of the complete works of James Baldwin for "valuable legal publications" from China.[33][34] This relationship lasted until the early 2000s, when the Columbia University Libraries discontinued its exchange department.[35]

In 1978, two years after the end of the Cultural Revolution, the library started publishing the Bulletin of the Beijing Library (Beitu Tongxun 北图通讯), which quickly became one of China's most important library publications.[36] In 1979, under an Implementing Accord regulating cultural exchanges between the U.S. and China, it vowed to exchange library material with the Library of Congress.[37] To compensate for a lack of professionally trained librarians, starting in 1982 librarians from the NLC and other academic libraries spent periods of six months at the Library of Congress and the Yale University Library.[38] To develop library science, the NLC established links with the Australian National University.[36]

In October 1987, the Library moved to a modern building located north of Purple Bamboo Park in Haidian District.[39] In 1999, it was officially renamed the National Library of China.[40]

November 2001, approved by the State Council, the National Library of the two phase of the project and the national digital library project formally approved. As an important part of the national information industry infrastructure, has been included in the national "fifteen" plan, the national total investment of $1 billion 235 million, began to put into effect.[41]

In 28 October 2003, the National Library ALEPH500 computer integrated management system has been put into operation, which laid the foundation for the National Library to enter the ranks of the world's advanced libraries.[42]

Collections

Overview

The National Library of China's collection is the largest in Asia.[3][43] Its holdings of more than 41 million items (as of December 2020) also make it one of the world's largest libraries.[1][44][45] It houses official publications of the United Nations and foreign governments and a collection of literature and materials in over 115 languages.[3] The library contains inscribed tortoise shells and bones, ancient manuscripts, and block-printed volumes.[46] Among the most prized collections of the National Library of China are rare and precious documents and records from past dynasties in Chinese history.

The original collection of the Metropolitan Library was assembled from several sources. In 1909 the imperial court gave the library the only surviving complete copy of the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries (or Siku Quanshu), an enormous compilation completed in 1782 that had been made in only four copies. That copy had been held at the Wenjin Pavilion of the Imperial Summer Resort in Chengde.[19] On orders from the Qing Ministry of Education, the ancient books, archives, and documents of the Grand Secretariat were also transferred to the new library. So was the collection of the Guozijian or Imperial University, an institution that had been dismantled in 1905 at the same time as the imperial examination system.[47] These imperial collections included books and manuscripts dating to the Southern Song (1127–1279).[48] The content of three private libraries from the Jiangnan area were donated under the supervision of Duanfang, the viceroy of Liangjiang, and the Ministry arranged for the transfer from Gansu of what remained of the Dunhuang manuscripts. Finally, the court made great efforts to obtain rubbings of rare inscriptions on stone or bronze.[47]

Notable collections and items

- a collection of over 270,000 ancient and rare Chinese books, and over 1,640,000 traditional thread-bound Chinese books[3]

- over 35,000 inscriptions on oracle bones and tortoise shells from the Shang dynasty (c. 16th–11th century BC)[3]

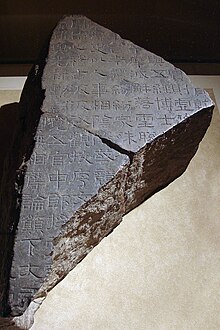

- surviving tablets of the Xiping Stone Classics created by Cai Yong (132–192) of the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 AD)[49]

- more than 16,000 volumes of precious historical Chinese documents and manuscripts from the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang[3]

- old maps, diagrams, and rubbings from ancient inscriptions on various materials[48]

- copies of Buddhist sutras dating to the 6th century[48]

- original draft of Sima Guang's Zizhi Tongjian[50]

- books and archives from imperial libraries of the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279),[46] including the works of Zhu Xi[51]

- oldest extant printed edition of the Huangdi Neijing (ca. 100 BC), from the Jin dynasty (1115–1234)[52]

- the most complete surviving Ming dynasty (1368–1644) copies of the Yongle Encyclopedia ("Great Canon of the Yongle Era")[48][53]

- a copy of the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries, completed in 1782 under the Qing dynasty[48]

- essential literary and books collection from the Qing imperial colleges and renowned private collectors[46]

Projects and programs

The Digital Library Promotion Project was launched in 2011, with the backing of the State Council. The goal of the Digital Library Promotion Project is to connect libraries at all levels, and to make resources and services accessible to more than 3,000 libraries country-wide. In order to allow for a total sharing of digital resources across the country, this project registered and integrated resources in libraries according to the principle of, 'centralized management of metadata, decentralized storage of object data.' By 2013, hardware to support this project had been installed into 30 provincial libraries and 139 prefectural-level libraries, which helped register over 1.5 million metadata in 123 databases, making over 12 terabytes of digital resources available to share. That same year saw a 67 percent increase from the previous year in users accessing the User Management System, with 221,000 visits.[4]

The Mobile Reading Platform of the Digital Library Promotion Project was also first put into effect in 2013, and more than 10 provinces began to provide new cell phone and digital television-based media services.[4]

Due to difficulties in preserving ancient texts, the NLC implemented several projects to work towards not only better preserving original materials, but also making copies available for research through microphotography, photocopy and digitization. The projects implemented to work on these preservation issues are the Chinese Ancient Books Reproduction Project, the Chinese Ancient Books Protection Plan, and the Minguo Materials (1911-1949) Protection Plan, to name just a few.[4]

The Chinese Ancient Books Reproduction Project was started in 2002, and its main goal was to copy and republish selected rare books. In their first phase, nearly 800 works from the Song and Yuan Dynasty were copied, reprinted, and distributed internationally to more than 100 libraries. The Chinese Ancient Books Protection Plan, which began in 2007, and the Minguo Materials (1911-1949) Protection Plan, which began in 2012, both strive to establish an integrated preservation mechanism at the national level.[4]

Services and facilities

The North and South complexes of the library are located in Haidian District while the Ancient Books Library is in Xicheng District.[54]

In 2012, the NLC allocated 11,549 square meters (124,312.4 square feet) to construct the National Museum of Classic Books, which opened in 2014. This museum features rare books and maps, Yangshi Lei architecture drawings, stone and bronze rubbings, oracle bones, and many other unique items.[4]

As of 2022, during what the National Library of China is calling the 'Normalized Epidemic Prevention and Control Period,' the operating hours for the library have not fully returned to pre-pandemic times. The North Complex, the South Complex, and the Children's Library are all open from 9am to 5pm Tuesdays through Sundays, and are closed on Mondays. The Ancient Books Library is open 9am to 5pm Tuesday through Saturdays, and is closed on Sundays and Mondays. Visitors wishing to enter the library are asked to make reservations in advance.[55] As of 2013, the Library maintains 14 branch offices, the latest of which is at the China Youth University for Political Sciences.[56]

Transportation

The Main Library, located on Zhongguancun South Road in Beijing's Haidian District, can be accessed by bus or subway.[57]

| Service | Station/Stop | Lines/Routes served |

|---|---|---|

| Beijing Bus | Guojiatushuguan (National Library) | * Regular: 86, 92, 319, 320, 332, 563, 588, 608, 689, 695, 697, 717 * Special (double-decker): 4, 6 * Yuntong (运通): 105, 106, 205 |

| Beijing Subway | National Library |

See also

- List of libraries

- List of national libraries

- Chinese Library Classification (CLC)

- Archives in the People's Republic of China

- Ningbo Library

References

Citations

- ^ a b c "馆藏实体资源". National Library of China. 2018. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ "Overview of Library Collections". National Library of China. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "The National Library of China (NLC) Advancing Towards the Twenty-first Century". National Library of Australia. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Yongjin, Han (October 2014). "Innovative services in the National Library of China". IFLA Journal. 40 (3): 202–205. doi:10.1177/0340035214543888. ISSN 0340-0352. S2CID 110832318.

- ^ "中国国家图书馆•中国国家数字图书馆——关于国图". www.nlc.cn. Archived from the original on 10 April 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ "中国国家图书馆•中国国家数字图书馆——关于国图". National Library of China. Archived from the original on 10 April 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ "中国国家图书馆•中国国家数字图书馆——关于国图". www.nlc.cn. Archived from the original on 10 April 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ "中国国家图书馆•中国国家数字图书馆——关于国图". www.nlc.cn. Archived from the original on 10 April 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ Bexin, Sun. "The Development of Authority Database in National Library of China" (PDF). National Institute of Informatics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ "中国国家图书馆•中国国家数字图书馆". www.nlc.cn. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ "隐身图书馆的"国家智库"——国家图书馆立法决策服务发展历程及成效". 嘉兴市文化广电新闻出版局. 9 October 2013. Archived from the original on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ "国家图书馆军事科学院分馆正式成立". www.mct.gov.cn. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ Li 2009, p. 4.

- ^ Li 2009, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Li 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Li 2009, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b Li 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Li 2009, p. 6. The date in the Chinese calendar is the 13th day of the 3rd month of the 1st year of Xuantong (宣统元年三月十三日; 宣統元年三月十三日), converted to a date in the Gregorian calendar on this site.

- ^ a b Li 2009, p. 8.

- ^ Li 2009, p. 8; Lin 1998, p. 57.

- ^ Kuo, P.W. "THE EVOLUTION OF THE CHINESE LIBRARY AND ITS RELATION TO CHINESE CULTURE". Bulletin of the American Library Association. 20 (10): 189–194.

- ^ Keenan 1994, p. 115.

- ^ Li 2009, p. 9.

- ^ Li, Zhizhong (2009). Zhongguo guo jia tu shu guan guan shi zi liao chang bian. Beijing Shi: Guo jia tu shu guan chu ban she. ISBN 9787501340729.

- ^ a b Lin 1998, p. 57.

- ^ Li 2009, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Li 2009, p. 18.

- ^ Lin 1998, p. 57; Li 2009, p. 18.

- ^ Bailey 1990, p. 222, note 155.

- ^ Bailey 1990, pp. 205 (borrowing not permitted at first), 207 (some libraries newly allowed borrowing), and 222, note 161 (citing a 1918 source saying that borrowing was allowed by then at the Beijing library).

- ^ Lin 1998, p. 30.

- ^ Li 2009, p. 157.

- ^ Gilroy, Harry (10 August 1963). "Columbia Is Exchanging Books With Red China". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ Xia, Jingfeng (31 March 2008). Scholarly Communication in China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea and Taiwan. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-78063-213-1. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ "History and Overview of the Collection". library.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ a b Lin 1983, p. 24.

- ^ Lin 1983, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Lin 1983, p. 25.

- ^ Li 2009, pp. 316–17.

- ^ Li 2009, p. 324.

- ^ Schwaag-Serger, Sylvia; Breidne, Magnus (July 2007). "China's Fifteen-Year Plan for Science and Technology: An Assessment". Asia Policy. 4 (1): 35–164. doi:10.1353/asp.2007.0013. S2CID 154488069. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ Cao, N. (2011). Tu shu zi liao zhuan ye ji shu zi ge kao shi fu dao zhi nan. 1st ed. Bei jing shi: Guo jia tu shu guan chu ban she.

- ^ "National Library of China to add its records to OCLC WorldCat". Library Technology Guides. 28 February 2008. Archived from the original on 10 March 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- ^ "From Tortoise Shells to Terabytes: The National Library of China's Digital Library Project". Library Connect. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- ^ "Columbia University Libraries and the National Library of China Sign Cooperative Agreement". Columbia University Libraries. 25 November 2008. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ a b c National Libraries. Archived 17 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ a b Li 2009, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e National Library of China. Archived 30 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ "The Xiping Stone Classics". World Digital Library. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Zhou & Weitz 2002, p. 278.

- ^ "The Four Books in Chapter and Verse with Collected Commentaries". World Digital Library. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "The Su Wen of the Huangdi Neijing (Inner Classic of the Yellow Emperor)". World Digital Library. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "China mega-book gets new life". CNN. 18 April 2002. Archived from the original on 24 February 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- ^ "Contact Us". National Library of China. Archived from the original on 1 July 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

Address: National Library of China, #33 Zhongguancun Nandajie, Hai Dian District, Beijing[...]Address: NLC Library of Ancient Books, #7 Wenjin Street, Xi Cheng District, Beijing

- Chinese address of main library Archived 24 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine: "北京市 海淀区 中关村南大街33号 国家图书馆" - Chinese address of Ancient Books Library Archived 27 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine: "北京市西城区文津街7号 国家图书馆古籍馆" - ^ "National Library of China - NLC news". www.nlc.cn. Archived from the original on 5 April 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ 李宏巧 (4 July 2013). 国家图书馆团中央分馆在中国青年政治学院揭牌 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ^ "NLC Home – Contact Us". National Library of China. Archived from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

Works cited

- Bailey, Paul J. (1990), Reform the People: Changing Attitudes Towards Popular Education in Early Twentieth-Century China, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 0-7486-0218-6.

- Keenan, Barry C. (1994), Imperial China's Last Classical Academies: Social Change in the Lower Yangzi, 1864–1911, Berkeley (CA): Institute of East Asian Studies, UC Berkeley, ISBN 1-55729-041-5.

- Li, Zhizhong 李致忠 (2009), Zhongguo guojia tushuguan guanshi 中国国家图书馆馆史 [History of the National Library of China] (in Chinese), Beijing: NLC Press (国家图书馆出版社), ISBN 978-7-5013-4070-5.

- Lin, Sharon Chien (1983), "Education for Librarianship in China after the Cultural Revolution", Journal of Education for Librarianship, 24 (1), (subscription required): 17–29, doi:10.2307/40322775, JSTOR 40322775.

- Lin, Sharon Chien (1998), Libraries and Librarianship in China, Westport (CT) and London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-28937-9.

- Zhou, Mi; Weitz, Ankeney (2002), Zhou Mi's Record of Clouds and Mist Passing Before One's Eyes: An Annotated Translation, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 9789004126053.

Further reading

- Cheng, Huan Wen (1991), "The Impact of American Librarianship on Chinese Librarianship in Modern Times (1840–1949)", Libraries & Culture, 26 (2), (subscription required): 372–87, JSTOR 25542343.

- Fung, Margaret C. (1984), "Safekeeping of the National Peiping Library's Rare Chinese Books at the Library of Congress 1941-1965", The Journal of Library History, 19 (3), (subscription required): 359–72, JSTOR 25541531.

- Lee, Hwa-Wei (30 June 1996). "American Contributions to Modern Library Development in China: A Historic Review". Paper presented at the 1st China–United States Library Conference.

- Li, Guoqing [李国庆] (2001), "History of the National Library of China", in Stam, David H. (ed.), International Dictionary of Library Histories, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, pp. 499–502, ISBN 1579582443.

- Lin, Sharon Chien (1983), "Education for Librarianship in China after the Cultural Revolution", Journal of Education for Librarianship, 24 (1), (subscription required): 17–29, doi:10.2307/40322775, JSTOR 40322775.

- Lin, Sharon Chien (1985), "Historical Development of Library Education in China", The Journal of Library History, 20 (4), (subscription required): 368–86, JSTOR 25541653.

- Prentice, Susan (1986), "The National Library of China – The View from Within", The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs, 15 (15), (subscription required): 103–12, doi:10.2307/2158874, JSTOR 2158874, S2CID 168486441.

- Yu, Priscilla C. (2001), "Leaning to One Side: The Impact of the Cold War on Chinese Library Collections", Libraries & Culture, 36 (1), (subscription required): 253–66, doi:10.1353/lac.2001.0019, JSTOR 25548906, S2CID 142658671.

- Yu, Priscilla C.; Davis, Donald G. Jr. (1998), "Arthur E. Bostwick and Chinese Library Development: A Chapter in International Cooperation", Libraries & Culture, 33 (4), (subscription required): 389–406, JSTOR 25548664.

- Zhu, Peter F. (13 October 2009). "Harvard College Library, China Form Pact - Harvard-Yenching Library collection to be digitized". Harvard Crimson.

External links

- Official Website

Media related to National Library of China at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to National Library of China at Wikimedia Commons