Atlantic City, New Jersey

Atlantic City, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

| City of Atlantic City | |

Atlantic City's boardwalk in May 2007, looking south outside Caesars. | |

| Nickname(s): "AC", "America's Favorite Playground" | |

| Motto: "Do AC" | |

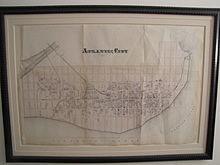

Map of Atlantic City in Atlantic County (click image to enlarge; also see: state map) | |

United States Census Bureau map of Atlantic City | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Atlantic |

| Incorporated | May 1, 1854 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Faulkner Act (Mayor-Council) |

| • Body | Atlantic City Council |

| • Mayor | Don Guardian (R) (term ends December 31, 2017)[1][2] |

| • Administrator | Arthur Liston[1] |

| • Clerk | Rhonda Williams[3] |

| Area | |

• City | 17.037 sq mi (44.125 km2) |

| • Land | 10.747 sq mi (27.835 km2) |

| • Water | 6.290 sq mi (16.290 km2) 36.92% |

| • Rank | 164th of 566 in state 8th of 23 in county[5] |

| Elevation | 7 ft (2 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 39,558 |

• Estimate (2013)[10] | 39,551 |

| • Rank | 55th of 566 in state 2nd of 23 in county[11] |

| • Density | 3,680.8/sq mi (1,421.2/km2) |

| • Rank | 171st of 566 in state 3rd of 23 in county[11] |

| • Metro | 275,549 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern (EDT)) |

| ZIP codes | |

| Area code | 609[14] |

| FIPS code | 3400102080[15][5][16] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0885142[17] |

| Website | www |

Atlantic City is a resort city in Atlantic County, New Jersey, famously known for its casinos, boardwalk and beach. It is the home of the Miss America Pageant. As of the 2010 United States Census, the city had a population of 39,558,[7][8][9] reflecting a decline of 959 (−2.4%) from the 40,517 counted in the 2000 U.S. Census, which had in turn increased by 2,531 (+6.7%) from the 37,986 counted in the 1990 U.S. Census.[19]

Atlantic City served as the inspiration for the original version of the board game Monopoly. Atlantic City is located on Absecon Island on the coast of the Atlantic Ocean.

There were 274,549 people living in the Atlantic City–Hammonton Metropolitan Statistical Area as of the 2010 Census.[20]

Atlantic City was incorporated on May 1, 1854, from portions of Egg Harbor Township and Galloway Township.[21]

History

Early days

Because of its location in South Jersey, hugging the Atlantic Ocean between marshlands and islands, Atlantic City was viewed by developers as prime real estate and a potential resort town. In 1853, the first commercial hotel, The Belloe House, located at Massachusetts and Atlantic Avenue, was built.[22]

The city was incorporated in 1854, the same year in which the Camden and Atlantic Railroad train service began. Built on the edge of the bay, this served as the direct link of this remote parcel of land with Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. By 1874, almost 500,000 passengers a year were coming to Atlantic City by rail. In Boardwalk Empire: The Birth, High Times, and Corruption of Atlantic City, "Atlantic City's Godfather"[23] Nelson Johnson describes the inspiration of Dr. Jonathan Pitney (the "Father of Atlantic City"[24]) to develop Atlantic City as a health resort, his efforts to convince the municipal authorities that a railroad to the beach would be beneficial, his successful alliance with Samuel Richards (entrepreneur and member of the "most influential" family in southern New Jersey at the time) to achieve that goal, the actual building of the railroad, and the experience of the first 600 riders, who "were chosen carefully by Samuel Richards and Jonathan Pitney":[25]

After arriving in Atlantic City, a second train brought the visitors to the door of the resort's first public lodging, the United States Hotel. The hotel was owned by the railroad. It was a sprawling, four-story structure built to house 2,000 guests. It opened while it was still under construction, with only one wing standing, and even that wasn't completed. By year's end, when it was fully constructed, the United States Hotel was not only the first hotel in Atlantic City but also the largest in the nation. Its rooms totaled more than 600, and its grounds covered some 14 acres.

The first boardwalk was built in 1870 along a portion of the beach in an effort to help hotel owners keep sand out of their lobbies. Businesses were restricted and the boardwalk was removed each year at the end of the peak season.[26] Because of its effectiveness and popularity, the boardwalk was expanded in length and width, and modified several times in subsequent years. The historic length of the boardwalk, before the destructive 1944 Great Atlantic Hurricane, was about 7 miles (11 km) and it extended from Atlantic City to Longport, through Ventnor and Margate.[27]

The first road connecting the city to the mainland at Pleasantville was completed in 1870 and charged a 30-cent toll. Albany Avenue was the first road to the mainland that was available without a toll.[28]

By 1878, because of the growing popularity of the city, one railroad line could no longer keep up with demand. Soon, the Philadelphia and Atlantic City Railway was also constructed to transport tourists to Atlantic City. At this point massive hotels like The United States and Surf House, as well as smaller rooming houses, had sprung up all over town. The United States Hotel took up a full city block between Atlantic, Pacific, Delaware, and Maryland Avenues. These hotels were not only impressive in size, but featured the most updated amenities, and were considered quite luxurious for their time.

Boom period

During the early part of the 20th century, Atlantic City went through a radical building boom. Many of the modest boarding houses that dotted the boardwalk were replaced with large hotels. Two of the city's most distinctive hotels were the Marlborough-Blenheim Hotel and the Traymore Hotel.

In 1903, Josiah White III bought a parcel of land near Ohio Avenue and the boardwalk and built the Queen Anne style Marlborough House. The hotel was a hit and, in 1905–06, he chose to expand the hotel and bought another parcel of land next door to his Marlborough House. In an effort to make his new hotel a source of conversation, White hired the architectural firm of Price and McLanahan. The firm made use of reinforced concrete, a new building material invented by Jean-Louis Lambot in 1848 (Joseph Monier received the patent in 1867). The hotel's Spanish and Moorish themes, capped off with its signature dome and chimneys, represented a step forward from other hotels that had a classically designed influence. White named the new hotel the Blenheim and merged the two hotels into the Marlborough-Blenheim. Bally's Atlantic City was later constructed at this location.

The Traymore Hotel was located at the corner of Illinois Avenue and the boardwalk. Begun in 1879 as a small boarding house, the hotel grew through a series of uncoordinated expansions. By 1914, the hotel's owner, Daniel White, taking a hint from the Marlborough-Blenheim, commissioned the firm of Price and McLanahan to build an even bigger hotel. Rising 16 stories, the tan brick and gold-capped hotel would become one of the city's best-known landmarks. The hotel made use of ocean-facing hotel rooms by jutting its wings farther from the main portion of the hotel along Pacific Avenue.

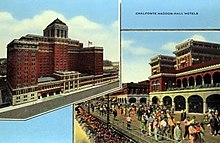

One by one, additional large hotels were constructed along the boardwalk, including the Brighton, Chelsea, Shelburne, Ambassador, Ritz Carlton, Mayflower, Madison House, and the Breakers. The Quaker-owned Chalfonte House, opened in 1868, and Haddon House, opened in 1869, flanked North Carolina Avenue at the beach end. Their original wood-frame structures would be enlarged, and even moved closer to the beach, over the years. The modern Chalfonte Hotel, eight stories tall, opened in 1904. The modern Haddon Hall was built in stages and was completed in 1929, at eleven stories. By this time, they were under the same ownership and merged into the Chalfonte-Haddon Hall Hotel, becoming the city's largest hotel with nearly 1,000 rooms. By 1930, the Claridge, the city's last large hotel before the casinos, opened its doors. The 400-room Claridge was built by a partnership that included renowned Philadelphia contractor John McShain. At 24 stories, it would become known as the "Skyscraper By The Sea." The city became known as the "The World's Playground.[29][30]

In 1883, salt water taffy was conceived in Atlantic City by David Bradley. The traditional story is that Bradley's shop was flooded after a major storm, soaking his taffy with salty Atlantic Ocean water. He sold some "salt water taffy" to a girl, who proudly walked down to the beach to show her friends. Bradley's mother was in the back of the store when the sale was made, and loved the name, and so salt water taffy was born.[31][32]

Prohibition era

The 1920s, with tourism at its peak, are considered by many historians as Atlantic City's golden age. During Prohibition, which was enacted nationally in 1919 and lasted until 1933, much liquor was consumed and gambling regularly took place in the back rooms of nightclubs and restaurants. It was during Prohibition that racketeer and political boss Enoch L. "Nucky" Johnson rose to power. Prohibition was largely unenforced in Atlantic City, and, because alcohol that had been smuggled into the city with the acquiescence of local officials could be readily obtained at restaurants and other establishments, the resort's popularity grew further.[33] The city then dubbed itself as "The World's Playground". Nucky Johnson's income, which reached as much as $500,000 annually, came from the kickbacks he took on illegal liquor, gambling and prostitution operating in the city, as well as from kickbacks on construction projects.[34]

During this time, Atlantic City was under the mayoral reign of Edward L. Bader, known for his contributions to the construction, athletics and aviation of Atlantic City.[35] Despite the opposition of many others, he purchased land that became the city's municipal airport and high school football stadium, both of which were later named Bader Field in his honor.[36] He led the initiative, in 1923, to construct the Atlantic City High School at Albany and Atlantic Avenues.[35] Bader, in November 1923, initiated a public referendum, during the general election, at which time residents approved the construction of a Convention Center. The city passed an ordinance approving a bond issue for $1.5 million to be used for the purchase of land for Convention Hall, now known as the Boardwalk Hall, finalized September 30, 1924.[37] Bader was also a driving force behind the creation of the Miss America competition.[38]

Decline and resurgence

Like many older east coast cities after World War II, Atlantic City became plagued with poverty, crime, corruption, and general economic decline in the mid-to-late 20th century. The neighborhood known as the "Inlet" became particularly impoverished. The reasons for the resort's decline were multi-layered. First of all, the automobile became more readily available to many Americans after the war. Atlantic City had initially relied upon visitors coming by train and staying for a couple of weeks. The car allowed them to come and go as they pleased, and many people would spend only a few days, rather than weeks. Also, the advent of suburbia played a huge role. With many families moving to their own private houses, luxuries such as home air conditioning and swimming pools diminished their interest in flocking to the luxury beach resorts during the hot summer. But perhaps the biggest factor in the decline in Atlantic City's popularity came from cheap, fast jet service to other premier resorts, such as Miami Beach and the Bahamas.[39]

The city hosted the 1964 Democratic National Convention which nominated Lyndon Johnson for President and Hubert Humphrey as Vice President. The convention and the press coverage it generated, however, cast a harsh light on Atlantic City, which by then was in the midst of a long period of economic decline. Many felt that the friendship between Johnson and the Governor of New Jersey at that time, Richard J. Hughes, led Atlantic City to host the Democratic Convention.[40]

By the late 1960s, many of the resort's once great hotels were suffering from embarrassing vacancy rates. Most of them were either shut down, converted to cheap apartments, or converted to nursing home facilities by the end of the decade. Prior to and during the advent of legalized gaming, many of these hotels were demolished. The Breakers, the Chelsea, the Brighton, the Shelburne, the Mayflower, the Traymore, and the Marlborough-Blenheim were demolished in the 1970s and 1980s. Of the many pre-casino resorts that bordered the boardwalk, only the Claridge, the Dennis, the Ritz-Carlton, and the Haddon Hall survive to this day as parts of Bally's Atlantic City, a condo complex, and Resorts Atlantic City. The old Ambassador Hotel was purchased by Ramada in 1978 and was gutted to become the Tropicana Casino and Resort Atlantic City, only reusing the steelwork of the original building.[41] Smaller hotels off the boardwalk, such as the Madison also survived.

Legalized gambling

In an effort at revitalizing the city, New Jersey voters in 1976 passed a referendum, approving casino gambling for Atlantic City; this came after a 1974 referendum on legalized gambling failed to pass. Immediately after the legislation passed, the owners of the Chalfonte-Haddon Hall Hotel began converting it into the Resorts International. It was the first legal casino in the eastern United States when it opened on May 26, 1978.[42] Other casinos were soon constructed along the Boardwalk and, later, in the marina district for a total of eleven today. The introduction of gambling did not, however, quickly eliminate many of the urban problems that plagued Atlantic City. Many people have suggested that it only served to exacerbate those problems, as attested to by the stark contrast between tourism intensive areas and the adjacent impoverished working-class neighborhoods.[43] In addition, Atlantic City has been less popular than Las Vegas, as a gambling city in the United States.[44] Donald Trump helped bring big name boxing bouts to the city to attract customers to his casinos. The boxer Mike Tyson had most of his fights in Atlantic City in the 1980s, which helped Atlantic City achieve nationwide attention as a gambling resort.[45] Numerous highrise condominiums were built for use as permanent residences or second homes.[46] By end of the decade it was the most popular tourist destination in the United States.[47]

Modern day

With the redevelopment of Las Vegas and the opening of two casinos in Connecticut in the early 1990s, and along with newly built casinos in the nearby Philadelphia metro area in the 2000s, Atlantic City's tourism began to decline due to its failure to diversify away from gaming. Determined to expand, in 1999 the Atlantic City Redevelopment Authority partnered with Las Vegas casino mogul Steve Wynn to develop a new roadway to a barren section of the city near the Marina. Nicknamed "The Tunnel Project", Steve Wynn planned the proposed 'Mirage Atlantic City' around the idea that he would connect the $330 million tunnel stretching 2.5 miles (4.0 km) from the Atlantic City Expressway to his new resort. The roadway was later officially named the Atlantic City-Brigantine Connector, and funnels incoming traffic off of the expressway into the city's marina district and Brigantine, New Jersey.[48]

Although Wynn's plans for development in the city were scrapped in 2002, the tunnel opened in 2001. The new roadway prompted Boyd Gaming in partnership with MGM/Mirage to build Atlantic City's newest casino. The Borgata opened in July 2003, and its success brought an influx of developers to Atlantic City with plans for building grand Las Vegas style mega casinos to revitalize the aging city.[49]

Owing to economic conditions and the late 2000s recession, many of the proposed mega casinos never went further than the initial planning stages. One of these developers was Pinnacle Entertainment, who purchased the Sands Atlantic City, only to close it permanently November 11, 2006. The following year, the resort was demolished in a dramatic, Las Vegas styled implosion, the first of its kind in Atlantic City. While Pinnacle Entertainment intended to replace it with a $1.5–2 billion casino resort, the company canceled its construction plans and plans to sell the land. The biggest disappointment was when MGM Resorts International announced that it would pull out of all development for Atlantic City, effectively ending their plans for the MGM Grand Atlantic City.[50][51]

In 2006, Morgan Stanley purchased 20 acres (8.1 ha) directly north of the Showboat Atlantic City Hotel and Casino for a new $2 billion plus casino resort.[52] Revel Entertainment Group was named as the project's developer for the Revel Casino. Revel was hindered with many problems, with the biggest setback to the company being in April 2010 when Morgan Stanley, the owner of 90% of Revel Entertainment Group, decided to discontinue funding for continued construction and put its stake in Revel up for sale. Early in 2010 the New Jersey state legislature passed a bill offering tax incentives to attract new investors and complete the job, but a poll by Fairleigh Dickinson University's PublicMind released in March 2010 showed that three of five voters (60%) opposed the legislation, and two of three of those who opposed it "strongly" opposed it.[53][54] Ultimately, Governor Chris Christie offered Revel $261 million in state tax credits to assist the casino once it opened.[55] As of March 2011[update], Revel had completed all of the exterior work and had continued work on the interior after finally receiving the funding necessary to complete construction. It had a soft opening in April 2012, and was fully open by May 2012. Ten months later, in February 2013, after serious losses and a write-down in the value of the resort from $2.4 billion to $450 million, Revel filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. It was restructured but still could not carry on and re-entered bankruptcy on 19 June 2014. It was put up for sale, however as no suitable bids were received the resort closed its doors on 2 September 2014.[56]

"Superstorm Sandy" struck Atlantic City on October 29, 2012, causing flooding and power-outages but left minimal damage to any of the tourist areas including the Boardwalk and casino resorts, despite widespread belief that the city's boardwalk had been destroyed. The source of the misinformation was a widely circulated photograph of a damaged section of the Boardwalk that was slated for repairs, prior to the storm, and incorrect news reports at the time of the disaster.[57] The storm produced an all-time record low barometric pressure reading of 943 mb (27.85") [58] for not only Atlantic City, but the state of New Jersey.

The city borders Absecon, Brigantine, Pleasantville, Ventnor City and West Atlantic City (part of Egg Harbor Township).

Economy

As of September 2014, the greater Atlantic City area has one of the highest unemployment rates in the country at 13.8%, out of labor force of around 141,000. [59]

Tourism district

In July 2010, Governor Chris Christie announced that a state takeover of the city and local government "was imminent". Comparing regulations in Atlantic City to an "antique car", Atlantic City regulatory reform is a key piece of Gov. Chris Christie's plan, unveiled on July 22, to reinvigorate an industry mired in a four-year slump in revenue and hammered by fresh competition from casinos in the surrounding states of Delaware, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and more recently, Maryland. In January 2011, Chris Christie announced the Atlantic City Tourism District, a state-run district encompassing the boardwalk casinos, the marina casinos, the Atlantic City Outlets, and Bader Field.[60][61] Fairleigh Dickinson University's PublicMind poll surveyed New Jersey voters' attitudes on the takeover. The February 16, 2011 survey showed that 43% opposed the measure while 29% favored direct state oversight.[62] Interestingly, the poll also found that even South Jersey voters expressed opposition to the plan; 40% reported they opposed the measure and 37% reported they were in favor of it.[62]

On April 29, 2011, the boundaries for the state-run tourism district were set. The district would include heavier police presence, as well as beautification and infrastructure improvements. The CRDA would oversee all functions of the district and will make changes to attract new businesses and attractions. New construction would be ambitious and may resort to eminent domain.[63][64]

The tourism district would comprise several key areas in the city; the Marina District, Ducktown, Chelsea, South Inlet, Bader Field, and Gardner's Basin. Also included are 10 roadways that lead into the district, including several in the city's northern end, or North Beach. Gardner's Basin, which is home to the Atlantic City Aquarium, was initially left out of the tourism district, while a residential neighborhood in the Chelsea section was removed from the final boundaries, owing to complaints from the city. Also, the inclusion of Bader Field in the district was controversial and received much scrutiny from mayor Lorenzo Langford, who cast the lone "no" vote on the creation of the district citing its inclusion.[65]

Casinos and gambling

Atlantic City is considered the "Gambling Capital of the East Coast," and currently has eight large casinos and several smaller ones. In 2011, New Jersey's casinos employed approximately 33,000 employees, had 28.5 million visitors, made $3.3 billion in gaming revenue, and paid $278 million in taxes.[66] They are regulated by the New Jersey Casino Control Commission[67] and the New Jersey Division of Gaming Enforcement.[68]

As a result of the United States' economic downturn and the legalization of gambling in adjacent states (including Delaware, Maryland, New York and Pennsylvania), four casino closures took place in 2014: the Atlantic Club on January 13; the Showboat on August 31;[69][70] the Revel, which was Atlantic City's second-newest casino, on September 2;[71] and Trump Plaza, which originally opened in 1984, and currently the poorest performing casino in the US[citation needed], on September 16.[72] Despite media reports of the decline,[citation needed] the ownership groups of the eight remaining casinos understand a market correction was necessary.[citation needed]

Executives at Trump Entertainment Resorts, whose sole remaining property will be the Trump Taj Mahal, have said they are considering the option of selling the Taj and winding down and exiting the gaming and hotel business.[citation needed]

Caesars Entertainment executives have said that they are considering the future of their three remaining Atlantic City properties (Bally's, Caesars and Harrah's), but have not publicly disclosed what those plans are.[citation needed]

Current casinos

| Casino | Opening Date/Closing Date | Theme | Hotel Rooms[73] | Section of Atlantic City |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resorts | May 28, 1978 | Roaring Twenties | 942 | Uptown |

| Caesars | June 26, 1979 | Roman Empire | 1,141 | Midtown |

| Bally's | December 29, 1979 | Modern | 1,749 | Midtown |

| Harrah's | November 27, 1980 | Marina Waterfront | 2,590 | Marina |

| Tropicana | November 26, 1981 | Old Havana | 2,078 | Downbeach |

| Golden Nugget | June 19, 1985 | Gold Rush Era | 727 | Marina |

| Trump Taj Mahal | April 2, 1990 | Taj Mahal | 2,010 | Uptown |

| Borgata | July 2, 2003 | Tuscany | 2,767 | Marina |

- a Bally's Atlantic City includes The Wild Wild West Casino, which opened on July 2, 1997 and has an American Old West theme.

Renamed casinos

| Casino | New Name |

|---|---|

| ACH Casino Resort | The Atlantic Club Casino Hotel |

| Atlantic City Hilton (Original) | Trump Castle |

| Atlantic City Hilton | ACH Casino Resort |

| Bally's Grand | The Grand |

| Bally's Park Place | Bally's Atlantic City |

| Brighton Casino | Sands Atlantic City |

| Del Webb's Claridge | Claridge |

| Golden Nugget (Original) | Bally's Grand |

| Park Place | Bally's Park Place |

| Harrah's at Trump Plaza | Trump Plaza |

| Playboy Hotel & Casino | Permanent casino license denied; renamed Atlantis Casino |

| The Grand | The Atlantic City Hilton |

| Trump's Castle | Trump Marina |

| Trump Marina | Golden Nugget |

Closed casinos

| Casino | Opening Date | Closing Date | Status of Property |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trump Plaza | May 14, 1984 | September 16, 2014 | On February 15, 2013, Trump Entertainment Resorts announced that it intended to sell Trump Plaza to the Meruelo Group for $20 million, the lowest price ever paid for an Atlantic City casino.[74] Carl Icahn, senior lender for Trump Plaza's mortgage, declined to approve the sale for the proposed price.[75] |

| Revel | April 2, 2012 | September 2, 2014 | Brookfield Asset Management's winning bid of $110 million on September 30, 2014 for Atlantic City's Revel Casino Hotel, and the company's intention to operate it as a casino, have generated some excitement. However Brookfield Management backed-out of this deal on November 19, 2014, throwing its disposition status back into limbo. |

| Showboat | April 2, 1987 | August 31, 2014 | Stockton State College has purchased this property on December 13, 2014 for $18 million, and are converting it into a four-year degree-granting college. |

| Atlantic Club | December 12, 1980 | January 13, 2014 | Building and contents sold to Caesars Entertainment Corporation Slots and Tables sold to Tropicana Casino & Resort Atlantic City. |

| Sands | August 31, 1980 | November 11, 2006 | Building demolished; now an empty lot |

| Claridge | July 20, 1981 | December 30, 2002 | Now operating as an independent hotel. |

| Trump World's Fair | May 15, 1996 | October 3, 1999 | Building demolished; now an empty lot |

| Playboy / Atlantis Casino | April 14, 1981 | July 4, 1989 | Playboy Enterprises found unsuitable for licensure, Playboy casino closed and then reopened by Elsinor Corporation as the Atlantis. In 1989 the Casino Control Commission revoked Atlantis' license and property sold to become Trump World's Fair an extension of the Trump Plaza. |

Cancelled casinos

| Casino | Status of Property |

|---|---|

| Camelot | Cancelled; currently an empty lot |

| Dunes Atlantic City | Never completed; now an empty lot |

| Hard Rock Casino | Cancelled; now an empty lot |

| Hilton (Original) | Casino license denied; current site of Golden Nugget Atlantic City |

| Le Jardin | Cancelled; currently an empty lot |

| Margaritaville Marina Casino | Cancelled; current site of Golden Nugget Atlantic City |

| Mirage Atlantic City | Cancelled; currently an empty lot |

| MGM Grand Atlantic City | Cancelled; currently an empty lot |

| Penthouse Casino | Never built; current site of Trump Plaza |

| Resorts Taj Mahal | Cancelled; current site of Taj Mahal |

| Sahara Atlantic City | Cancelled; now a parking lot |

Boardwalk

The Atlantic City Boardwalk was the first boardwalk in the United States, having opened on June 26, 1870.[76]

The Boardwalk starts at Absecon Inlet in the north and runs along the beach south-west to the city limit 4 miles (6.4 km) away then continues 1+1⁄2 miles (2.4 km) into Ventnor City. Casino/hotels front the boardwalk, as well as retail stores, restaurants, and amusements. Notable attractions include the Boardwalk Hall, House of Blues, and the Ripley's Believe It or Not! museum.

In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy destroyed the northern part of the boardwalk fronting Absecon Inlet, in the residential section called South Inlet. The oceanfront boardwalk in front of the Atlantic City casinos survived the storm undamaged.[77][78]

The Boardwalk has been home to several piers over the years.

- The first pier, Ocean Pier, was built in 1882.[79] It eventually fell into disrepair and was demolished. Another famous pier built during that time was Steel Pier, opened in 1898, which once billed itself as "The Showplace of the Nation". It now operates as an amusement pier across from the Trump Taj Mahal. Captain John Lake Young opened "Young's Million Dollar Pier" as an arcade hall in 1903, and on the seaward side "erected a marble mansion", fronted by a formal garden, with lighting and landscaping designed by Young's longtime friend Thomas Alva Edison. Young's Million Dollar Pier, Atlantic City's largest amusement pier during its time",[25] was transformed into a shopping mall in the 1980s, known as "Shops on Ocean One". In 2006, the Ocean One mall was bought, renovated and re-branded as The Pier Shops at Caesars. Garden Pier, located opposite Revel Atlantic City, once housed a movie theater, and is now home to the Atlantic City Historical Society and Arts Center.[80] Two other piers, an amusement pier named Steeplechase Pier and a Heinz 57-owned pier named Heinz Pier were destroyed in the 1944 Great Atlantic Hurricane.[81] Steeplechase was rebuilt after the hurricane, and survived into the casino era. The "Steeplechase Pier Heliport" on Steel Pier is named in its honor.[82] The last of the four piers still standing is Schiff's Central Pier, which is the only one still offering the same attractions it did when it opened – a few stores, and the playcade, having reopened in 1990 after an $8 million renovation.[83]

Shopping

Atlantic City has many different shopping districts and malls, many of which are located inside or adjacent to the casino resorts. Several smaller themed retail and dining areas in casino hotels include the Borgata Shops and The Shoppes at Water Club inside the Borgata, the Waterfront Shops inside of Harrah's, Spice Road inside the Trump Taj Mahal, while Resorts Casino Hotel has a small collection of stores and restaurants. Major shopping malls are also located in and around Atlantic City.

In Atlantic City, shops include:

- Pier Shops at Caesars, an underwater-themed indoor high end shopping center located on the Million Dollar Pier formerly known as "Shops on Ocean One". The four-story shopping mall contains themed floors as well as a fountain show.

- Tanger Outlets The Walk, an outdoor outlet shopping center spanning several blocks. The only outlet mall in Atlantic County and South Jersey, The Walk opened in 2003 and is undergoing an expansion.

- The Quarter at Tropicana, an old Havana-themed indoor shopping center at the Tropicana, which contains over 40 stores, restaurants, and nightclubs.

Exhibition

Boardwalk Hall, formally known as the "Historic Atlantic City Convention Hall", is an arena in Atlantic City along the boardwalk. Boardwalk Hall was Atlantic City's primary convention center until the opening of the Atlantic City Convention Center in 1997. The Atlantic City Convention Center includes 500,000 sq ft (46,000 m2) of showroom space, 5 exhibit halls, 45 meeting rooms with 109,000 sq ft (10,100 m2) of space, a garage with 1,400 parking spaces, and an adjacent Sheraton hotel. Both the Boardwalk Hall and Convention Center are operated by the Atlantic City Convention & Visitors Authority.

Culture

Monopoly

Atlantic City (sometimes referred to as "Monopoly City"[84]) has become well-known over the years for its portrayal in the U.S. version of the popular board game, Monopoly, in which properties on the board are named after locations in and near Atlantic City. While the original incarnation of the game did not feature Atlantic City, it was in Indianapolis that Ruth Hoskins learned the game, and took it back to Atlantic City.[85] After she arrived, Hoskins made a new board with Atlantic City street names, and taught it to a group of local Quakers.[86]

Some of the actual locations that correspond to board elements have changed since the game's release. Illinois Avenue was renamed Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd. in the 1980s. St. Charles Place no longer exists, as the Showboat Casino Hotel was developed where it once ran.[87]

Marvin Gardens, the leading yellow property on the board shown, is actually a misspelling of the original location name, "Marven Gardens". The misspelling was said to have been introduced by Charles Todd and passed on when his home-made Monopoly board was copied by Charles Darrow and thence Parker Brothers. It was not until 1995 that Parker Brothers acknowledged this mistake and formally apologized to the residents of Marven Gardens for the misspelling although the spelling error was not corrected.[88]

The "Short Line" is believed to refer to the Shore Fast Line, a streetcar line that served Atlantic City.[89] The B&O Railroad did not serve Atlantic City. A booklet included with the reprinted 1935 edition states that the four railroads that served Atlantic City in the mid-1930s were the Jersey Central, the Seashore Lines, the Reading Railroad, and the Pennsylvania Railroad.

The actual "Electric Company" and "Water Works" serving the city are respectively, Atlantic City Electric Company and the Atlantic City Municipal Utilities Authority.

Governor of New Jersey stated in September 2014 that the government will consider putting the 40-year-old law that gave Atlantic City a monopoly on gambling in New Jersey on voting in November 2015. With as many as four of Atlantic City’s 12 casinos closing this year, some lawmakers say allowing gambling in other towns is crucial to reclaim revenue that has gone to New York and Philadelphia. According to Reuters, the growth of gambling in Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and New York cut casino revenue in Atlantic City to $2.9 billion last year from a peak of $5.2 billion in 2006. The drop means less money for New Jersey, which collects an 8 percent tax from casinos and dedicates the money -- $205 million last year—to programs for senior citizens and the disabled.[90]

Attractions

Ever since Atlantic City's growth as a resort town, numerous attractions and tourist traps have originated in the city. A popular fixture in the early 20th century at the Steel Pier was horse diving, which was introduced by William "Doc" Carver.[91] The Steel Pier featured several other novelty attractions, including the Diving Bell, human high-divers, and a water circus.[92][93] Advertisements for the Steel Pier in its heyday featured plaster sculptures set upon wooden bases along roads leading up to Atlantic City.[94] By the end of World War II, many animal demonstrations declined in popularity after criticisms of animal abuse and neglect.

Rolling chairs, which were introduced in the 1800s, have been a boardwalk fixture to this day. While powered carts appeared in the 1960s, the original and most common were made of wicker. The wicker, canopied chairs-on-wheels are manually pushed the length of the boardwalk by attendants, much like a Rickshaw.[95]

The Absecon Light is a coastal lighthouse located in the north end of Atlantic City overlooking Absecon Inlet. It is the tallest lighthouse in the state of New Jersey and is the third tallest masonry lighthouse in the United States. Construction began in 1854, with the light first lit on January 15, 1857.[96] The lighthouse was deactivated in 1933 and although the light still shines every night, it is no longer an active navigational aid.[97]

While located two miles south of Atlantic City in Margate City, Lucy the Elephant has become almost an icon for the Atlantic City area. Lucy is a six-story elephant-shaped example of novelty architecture, constructed of wood and tin sheeting in 1882 by James V. Lafferty in an effort to sell real estate and attract tourism. Over the years, Lucy had served as a restaurant, business office, cottage, and tavern (the last closed by Prohibition). Lucy had fallen into disrepair by the 1960s and was scheduled for demolition. The structure was moved and refurbished as a result of a "Save Lucy" campaign in 1970 and received designation as a National Historic Landmark in 1976, and is open as a museum.[98]

Events

Atlantic City is the home of the Miss America competition, however it was briefly moved to Las Vegas for seven years before returning. The Miss America competition originated on September 7, 1921, as a two-day beauty contest. The event that year was called the "Atlantic City Pageant", and the winner of the grand prize, the 3-foot Golden Mermaid trophy, was not called "Miss America" until 1922, when she re-entered the pageant. The pageant was initiated in to extend the tourist season after the Labor Day weekend[38] The pageant has been nationally televised since 1954. It peaked in the early 1960s, when it was repeatedly the highest-rated program on American television. It was seen as a symbol of the United States, with Miss America often being referred to as the female equivalent of the President. The pageant's longtime emcee, Bert Parks, hosted the event from 1955 to 1979. At the Atlantic City Convention Center, there is an interactive statue of Parks holding a crown. When a visitor puts their head inside the crown, sensors activate a recorded playback of his "There She Is..." line through speakers hidden behind nearby bushes.[99]

After the departure of the Miss America pageant from the city, a LGBT event known as the "Miss'd America Pageant" is held annually at the Boardwalk Hall. Originally started as a fundraiser, the event features drag queens donning the runway in a similar manner to the Miss America pageant.[100]

Since 2003, Atlantic City has hosted Thunder over the Boardwalk, an annual airshow over the boardwalk. The yearly event, a joint venture between the New Jersey Air National Guard's 177th Fighter Wing along with several casinos, attracts over 750,000 visitors each year.[101]

Boardwalk Empire

Since 2010, Boardwalk Empire, an American television series from cable network HBO set in Atlantic City during the Prohibition era, has cast a new light on the city. Starring Steve Buscemi, the show was adapted from a chapter about historical criminal kingpin Enoch "Nucky" Johnson (who is renamed "Enoch Thompson" in the show) in Nelson Johnson's book, Boardwalk Empire: The Birth, High Times, and Corruption of Atlantic City.[102] The series is filmed in Brooklyn, New York on a set built to resemble the Atlantic City boardwalk in the 1920s.

Around the same time of the September 2010 premiere of the show, the Press of Atlantic City created Boss of the Boardwalk, a 45-minute documentary which premiered on August 21, 2010 on NBC TV-40 and aired six additional times in the following weeks.[103]

Since the premiere of Boardwalk Empire, interest in the Roaring Twenties-era Atlantic City has grown. In October 2010, a plan was revealed to renovate the ailing Resorts Casino Hotel into a Roaring Twenties theme. The re-branding was proposed by current owner Dennis Gomes, and was initiated in December 2010 when he took over the casino. The changes accentuate the resort's existing art deco design, as well as presenting new 20s-era uniforms for employees and music from the time period. The casino also introduced drinks and shows reminiscent of the period.[104] The actual building where he lived, The Ritz-Carlton, offer tours.[105]

In 2011, the Academy Bus Company began a trolley tour called "Nucky's Way", a tour bus service that features actors portraying Nucky as well as other characters as it loops around the city. Nucky's Way is the second trolley tour to capitalize off of Boardwalk Empire, after The Great American Trolley company started a weekly tour of Atlantic City with a Roaring Twenties theme in early June 2011.[106]

On August 1, 2011, a façade modeled after the set of Boardwalk Empire was unveiled on the boardwalk in front of an empty lot at the former site of the Trump World's Fair resort. The façade of storefronts, which consists of vinyl tacked onto three large sections of plywood, was the brainchild of longtime area radio host Pinky Kravitz, who is also a columnist for The Press of Atlantic City and host of WMGM Presents Pinky on NBC40.[107]

Geography

Atlantic City is located at 39°22′38″N 74°27′04″W / 39.377297°N 74.451082°W (39.377297, −74.451082). According to the United States Census Bureau, the city had a total area of 17.037 square miles (44.125 km2), of which, 10.747 square miles (27.835 km2) of it was land and 6.290 square miles (16.290 km2) of it (36.92%) was water.[18][5]

The city is located on 8.1-mile (13.0 km) long Absecon Island, along with Ventnor City, Margate City and Longport to the southwest.[108]

Climate

Atlantic City has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), with some maritime moderation, especially during the summer.

Summers are typically warm and humid with a July daily average of 75.6 °F (24.2 °C). During this time, the city gets a sea breeze off the ocean that often makes daytime temperatures much cooler than inland areas, making Atlantic City a prime place for beating the summer heat from June through September. Average highs even just a few miles west of Atlantic City exceed 85 °F (29 °C) in July. Near the coast, temperatures reach or exceed 90 °F (32 °C) on an average of only 6.8 days a year, but this reaches 21 days at nearby Atlantic City Int'l.[109][a] Winters are cool, with January averaging 35.5 °F (2 °C). Spring and autumn are erratic, although they are usually mild with low humidity. The average window for freezing temperatures is November 20 to March 25,[109] allowing a growing season of 239 days. Extreme temperatures range from −9 °F (−23 °C) on February 9, 1934 to 104 °F (40 °C) on August 7, 1918.[b]

Annual precipitation is 40 inches (1,020 mm) which is fairly spread throughout the year. Owing to its close proximity to the Atlantic Ocean and its location in South Jersey, Atlantic City receives less snow than a good portion of the rest of New Jersey. Even at the airport, where low temperatures are often much lower than along the coast, snow averages only 16.5 inches (41.9 cm) each winter. It is very common for rain to fall in Atlantic City while the northern and western parts of the state are receiving snow.

| Climate data for Atlantic City International Airport, 1991–2020 normals,[c] extremes 1874–present[d] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 78 (26) |

76 (24) |

87 (31) |

94 (34) |

99 (37) |

106 (41) |

105 (41) |

103 (39) |

99 (37) |

96 (36) |

84 (29) |

77 (25) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 63.5 (17.5) |

64.8 (18.2) |

73.2 (22.9) |

83.2 (28.4) |

89.3 (31.8) |

94.5 (34.7) |

96.9 (36.1) |

94.6 (34.8) |

90.1 (32.3) |

82.8 (28.2) |

72.7 (22.6) |

65.3 (18.5) |

98.1 (36.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 43.2 (6.2) |

45.8 (7.7) |

52.6 (11.4) |

63.3 (17.4) |

72.5 (22.5) |

81.5 (27.5) |

86.6 (30.3) |

84.8 (29.3) |

78.5 (25.8) |

67.7 (19.8) |

57.1 (13.9) |

48.1 (8.9) |

65.1 (18.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 34.1 (1.2) |

36.0 (2.2) |

42.6 (5.9) |

52.5 (11.4) |

61.9 (16.6) |

71.4 (21.9) |

76.9 (24.9) |

75.0 (23.9) |

68.4 (20.2) |

57.1 (13.9) |

46.8 (8.2) |

38.7 (3.7) |

55.1 (12.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 25.1 (−3.8) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

32.6 (0.3) |

41.7 (5.4) |

51.4 (10.8) |

61.3 (16.3) |

67.2 (19.6) |

65.2 (18.4) |

58.2 (14.6) |

46.4 (8.0) |

36.6 (2.6) |

29.4 (−1.4) |

45.1 (7.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 6.5 (−14.2) |

9.7 (−12.4) |

16.1 (−8.8) |

26.7 (−2.9) |

36.0 (2.2) |

46.2 (7.9) |

55.9 (13.3) |

53.8 (12.1) |

43.5 (6.4) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

20.4 (−6.4) |

14.0 (−10.0) |

4.4 (−15.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −10 (−23) |

−11 (−24) |

2 (−17) |

12 (−11) |

25 (−4) |

37 (3) |

42 (6) |

40 (4) |

32 (0) |

20 (−7) |

10 (−12) |

−7 (−22) |

−11 (−24) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.38 (86) |

3.23 (82) |

4.52 (115) |

3.32 (84) |

3.34 (85) |

3.58 (91) |

4.47 (114) |

4.59 (117) |

3.55 (90) |

4.14 (105) |

3.37 (86) |

4.47 (114) |

45.96 (1,167) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 5.7 (14) |

5.9 (15) |

2.2 (5.6) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

3.2 (8.1) |

17.4 (44) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 3.6 (9.1) |

3.1 (7.9) |

1.3 (3.3) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.9 (4.8) |

6.0 (15) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.8 | 10.4 | 10.9 | 11.4 | 10.5 | 9.9 | 9.9 | 9.2 | 8.5 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 10.8 | 120.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.0 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 8.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69.5 | 69.0 | 66.9 | 66.4 | 70.7 | 72.9 | 73.9 | 75.7 | 76.4 | 74.8 | 72.8 | 70.6 | 71.6 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 21.6 (−5.8) |

23.2 (−4.9) |

30.0 (−1.1) |

37.9 (3.3) |

49.5 (9.7) |

59.4 (15.2) |

64.8 (18.2) |

64.2 (17.9) |

57.7 (14.3) |

46.4 (8.0) |

37.0 (2.8) |

27.0 (−2.8) |

43.2 (6.2) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 150.8 | 157.9 | 204.5 | 218.9 | 243.9 | 266.2 | 276.3 | 271.3 | 227.6 | 200.5 | 147.4 | 133.8 | 2,499.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 50 | 53 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 60 | 61 | 64 | 61 | 58 | 49 | 46 | 56 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1.6 | 2.6 | 4.2 | 6.0 | 7.5 | 8.5 | 8.6 | 7.7 | 6.0 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 5.0 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point and sun 1961–1990)[111][112][113] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: UV Index Today (1995 to 2022)[114] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 687 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,043 | 51.8% | |

| 1880 | 5,477 | 425.1% | |

| 1890 | 13,055 | 138.4% | |

| 1900 | 27,838 | 113.2% | |

| 1910 | 46,150 | 65.8% | |

| 1920 | 50,707 | 9.9% | |

| 1930 | 66,198 | 30.6% | |

| 1940 | 64,094 | −3.2% | |

| 1950 | 61,657 | −3.8% | |

| 1960 | 59,544 | −3.4% | |

| 1970 | 47,859 | −19.6% | |

| 1980 | 40,199 | −16.0% | |

| 1990 | 37,986 | −5.5% | |

| 2000 | 40,517 | 6.7% | |

| 2010 | 39,558 | −2.4% | |

| 2013 (est.) | 39,551 | [10][115] | 0.0% |

| Population sources: 1860–2000[116] 1860–1920[117] 1870[118][119] 1880–1890[120] 1890–1910[121] 1860–1930[122] 1930–1990[123] 2000[124][125] 2010[7][8][9] | |||

2010 Census

The Census Bureau's 2006–2010 American Community Survey showed that (in 2010 inflation-adjusted dollars) median household income was $30,237 (with a margin of error of +/- $2,354) and the median family income was $35,488 (+/- $2,607). Males had a median income of $32,207 (+/- $1,641) versus $29,298 (+/- $1,380) for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,069 (+/- $2,532). About 23.1% of families and 25.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 36.6% of those under age 18 and 16.8% of those age 65 or over.[126]

2000 Census

As of the 2000 United States Census[15] there were 40,517 people, 15,848 households, and 8,700 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,569.8 people per square mile (1,378.3/km2). There were 20,219 housing units at an average density of 1,781.4 per square mile (687.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 44.16% black or African American, 26.68% White, 0.48% Native American, 10.40% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 13.76% other races, and 4.47% from two or more races. 24.95% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. 19.44% of the population was non-Hispanic whites.[124][125]

There were 15,848 households out of which 27.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 24.8% were married couples living together, 23.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 45.1% were non-families. 37.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 15.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.46 and the average family size was 3.26.[124][125]

In the city the population was spread out with 25.7% under the age of 18, 8.9% from 18 to 24, 31.0% from 25 to 44, 20.2% from 45 to 64, and 14.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females there were 96.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.2 males.[124][125]

The median income for a household in the city was $26,969, and the median income for a family was $31,997. Males had a median income of $25,471 versus $23,863 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,402. About 19.1% of families and 23.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 29.1% of those under age 18 and 18.9% of those age 65 or over.[124][125]

Government

Local government

| Atlantic City | |

|---|---|

| Crime rates* (2007) | |

| Violent crimes | |

| Homicide | 15.1 |

| Rape | 70.4 |

| Robbery | 1,146.3 |

| Aggravated assault | 930.1 |

| Total violent crime | 2,161.9 |

| Property crimes | |

| Burglary | 1,370.0 |

| Larceny-theft | 5,422.2 |

| Motor vehicle theft | 502.8 |

| Arson | 40.2 |

| Total property crime | 7,335.2 |

Notes *Number of reported crimes per 100,000 population. Source: 2007 FBI UCR Data | |

Atlantic City is governed within the Faulkner Act (formally known as the Optional Municipal Charter Law) under the Mayor-Council system of municipal government (Plan D), implemented by direct petition effective as of July 1, 1982.[4][127] The City Council is the governing body of Atlantic City. There are nine Council members, who are elected to serve for a term of four years, one from each of six wards and three serving at-large. The City Council exercises the legislative power of the municipality for the purpose of holding Council meetings to introduce ordinances and resolutions to regulate City government. In addition, Council members review budgets submitted by the Mayor; provide for an annual audit of the City's accounts and financial transactions; organize standing committees and hold public hearings to address important issues which impact Atlantic City.[128] Former Mayor Bob Levy created the Atlantic City Ethics Board in 2007, but the Board was dissolved two years later by vote of the Atlantic City Council.

The Mayor is Don Guardian, whose term of office ends on December 31, 2017.[1] Members of the City Council are Council President William Marsh (4th Ward, 2015), Council Vice President Steven L. Moore (3rd Ward, 2015), Moisse Delgado (At-Large, 2017), Frank M. Gilliam, Jr. (At-Large, 2017), Rizwan Malik (5th Ward, 2015), Timothy Mancuso (6th Ward, 2015), Aaron Randolph (1st Ward, 2015), Marty Small (2nd Ward, 2015) and George Tibbitt (At-Large, 2017).[129][130]

Mayoral disappearance and resignation

Following questions about false claims he had made about his military record, Mayor Bob Levy left City Hall in September 2007 in a city-owned vehicle for an unknown destination. After a 13-day absence, his lawyer revealed that Levy was in Carrier Clinic, a rehabilitation hospital.[131] Levy resigned in October 2007 and then-Council President William Marsh assumed the office of Mayor[132] and served six weeks until an interim mayor was named.

Federal, state and county representation

Atlantic City is located in the 2nd Congressional district[133] and is part of New Jersey's 2nd state legislative district.[8][134][135]

For the 118th United States Congress, New Jersey's 2nd congressional district is represented by Jeff Van Drew (R, Dennis Township).[136] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Democrats Cory Booker (Newark, term ends 2027)[137] and George Helmy (Mountain Lakes, term ends 2024).[138][139]

For the 2024-2025 session, the 2nd legislative district of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the New Jersey Senate by Vincent J. Polistina (R, Egg Harbor Township) and in the General Assembly by Don Guardian (R, Atlantic City) and Claire Swift (R, Margate City).[140] Template:NJ Governor

Template:NJ Atlantic County Freeholders

Politics

As of March 23, 2011, there were a total of 20,001 registered voters in Atlantic City, of which 12,063 (60.3% vs. 30.5% countywide) were registered as Democrats, 1,542 (7.7% vs. 25.2%) were registered as Republicans and 6,392 (32.0% vs. 44.3%) were registered as Unaffiliated. There were 4 voters registered to other parties.[141] Among the city's 2010 Census population, 50.6% (vs. 58.8% in Atlantic County) were registered to vote, including 67.0% of those ages 18 and over (vs. 76.6% countywide).[141][142]

In the 2012 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 9,948 votes here (86.6% vs. 57.9% countywide), ahead of Republican Mitt Romney with 1,548 votes (13.5% vs. 41.1%) and other candidates with 49 votes (0.4% vs. 0.9%), among the 11,489 ballots cast by the city's 21,477 registered voters, for a turnout of 53.5% (vs. 65.8% in Atlantic County).[143][144] In the 2008 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 10,975 votes here (82.1% vs. 56.5% countywide), ahead of Republican John McCain with 2,175 votes (16.3% vs. 41.6%) and other candidates with 82 votes (0.6% vs. 1.1%), among the 13,370 ballots cast by the city's 26,030 registered voters, for a turnout of 51.4% (vs. 68.1% in Atlantic County).[145] In the 2004 presidential election, Democrat John Kerry received 8,487 votes here (74.5% vs. 52.0% countywide), ahead of Republican George W. Bush with 2,687 votes (23.6% vs. 46.2%) and other candidates with 96 votes (0.8% vs. 0.8%), among the 11,389 ballots cast by the city's 23,310 registered voters, for a turnout of 48.9% (vs. 69.8% in the whole county).[146]

In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Democrat Barbara Buono received 4,293 ballots cast (52.6% vs. 34.9% countywide), ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 2,897 votes (35.5% vs. 60.0%) and other candidates with 63 votes (0.8% vs. 1.3%), among the 8,155 ballots cast by the city's 23,049 registered voters, yielding a 35.4% turnout (vs. 41.5% in the county).[147][148] In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Democrat Jon Corzine received 4,988 ballots cast (69.9% vs. 44.5% countywide), ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 1,578 votes (22.1% vs. 47.7%), Independent Chris Daggett with 157 votes (2.2% vs. 4.8%) and other candidates with 99 votes (1.4% vs. 1.2%), among the 7,141 ballots cast by the city's 22,585 registered voters, yielding a 31.6% turnout (vs. 44.9% in the county).[149]

City and state agencies

New Jersey Casino Control Commission

The New Jersey Casino Control Commission is a New Jersey state governmental agency that was founded in 1977 as the state's gaming control board, responsible for administering the Casino Control Act and its regulations to assure public trust and confidence in the credibility and integrity of the casino industry and casino operations in Atlantic City. Casinos operate under licenses granted by the Commission. The commission is headquartered in the Arcade Building at Tennessee Avenue and Boardwalk in Atlantic City.[150]

Casino Reinvestment Development Authority

The CRDA was founded in 1984 and is responsible for directing the spending of casino reinvestment funds in public and private projects to benefit Atlantic City and other areas of the state. From 1985 through April 2008, CRDA spent US$1.5 billion on projects in Atlantic City and US$300 million throughout New Jersey.[151]

Atlantic City Convention & Visitors Authority

The Convention & Visitors Authority (ACCVA) was in charge of advertising and marketing for the city as well as promoting economic growth through convention and leisure tourism development. The ACCVA managed the Boardwalk Hall and Atlantic City Convention Center, as well as the Boardwalk Welcome Center inside Boardwalk Hall as well as a welcome center on the Atlantic City Expressway. In 2011, the ACCVA was absorbed into the CRDA as part of the state takeover that created the tourism district.[152]

Atlantic City Special Improvement District

The Atlantic City Special Improvement District (SID) was a nonprofit organization created in 1992, which funded by a special assessment tax on businesses within the improvement district and carries out various activities to improve the city's business community, including street cleaning and promotional efforts. In 2011, the SID was absorbed by the CRDA, in which the former SID boundaries would be expanded to the include all areas in the newly formed tourism district. Under the new structure, established by state legislation, the CRDA assumed the staff, equipment and programs of the SID. The new SID division is accompanied by a SID committee made up of CRDA board members and an advisory council consisting of the current trustees and others.[153]

Fire department

| Operational area | |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| State | |

| City | Atlantic City |

| Agency overview | |

| Established | April 4, 1904[154] |

| Staffing | Career |

| Fire chief | Dennis J. Brooks |

| EMS level | BLS First Responder |

| IAFF | 198 |

| Facilities and equipment | |

| Divisions | 1 |

| Battalions | 2 |

| Stations | 6 |

| Engines | 7 |

| Trucks | 2 |

| Rescues | 1 |

| HAZMAT | 1 |

| USAR | 1 |

| Fireboats | 2 |

| Website | |

| www | |

The Atlantic City Fire Department (ACFD) provides fire protection and first responder emergency medical services to the city of Atlantic City, New Jersey, United States. The ACFD currently operates out of 6 Fire Stations, located throughout the city in 2 Battalions, each under the command of a Battalion Chief, who in-turn reports to an on-duty Deputy Chief, or Tour Commander per shift.[155][156]

Fire station and apparatus locations

Below is a complete listing of all fire station and fire apparatus locations in the city .[157]

| Engine company | Ladder company | Special unit | Command unit | Address |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engine 1, Engine 7 | Ladder 1 | Haz-Mat. 1, Air Supply Unit | Battalion 1 | Atlantic Ave. & Maryland Ave. |

| Engine 2 | Rescue 1, Rescue 2, Marine 1, Marine 2, Collapse and Trench Unit, Training Unit | Deputy 1 | Baltic Ave. & N. Indiana Ave. | |

| Engine 3 | Engine 23(Reserve), Ladder 23(Reserve) | N. Indiana Ave. & Grant Ave. | ||

| Engine 4 | Ladder 2 | Engine 24(Reserve) | Battalion 2 | 2715 Atlantic Ave. |

| Engine 5 | N. Annapolis Ave. & Crossan Ave. | |||

| Engine 6 | Engine 26(Reserve), Ladder 26(Reserve) | Atlantic Ave. & S. Annapolis Ave. |

Closed and disbanded fire companies

Below is a complete listing of ACFD fire companies that have been disbanded over the course of the department's history due to budget cuts and department reorganization.

- Engine 8 - Baltic Ave. & N. Indiana Ave.

- Engine 9 - N. Indiana Ave. & Grant Ave.

- Engine 10 - Rhode Island Ave & Melrose Ave.

- Engine 11 - N. Annapolis Ave. & Crossan Ave.

- Truck 4 - 2715 Atlantic Ave.

- Truck 6 - N. Indiana Ave. & Grant Ave.

Police department

The city is protected by the Atlantic City Police Department, which handles 150,000 calls per year.[158] The current police chief is Henry White Jr.

Education

The Atlantic City School District serves students in pre-kindergarten through twelfth grades. Schools in the district (with 2010–11 enrollment data from the National Center for Education Statistics[159]) are Venice Park School[160] (PreK with 95 students), Brighton Avenue School,[161] Chelsea Heights School[162] (K-8; 408), Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. School Complex[163] (PreK-8; 576), New Jersey Avenue School (was PreK-6; 347), New York Avenue School[164] (PreK-8; 575), Pennsylvania Avenue School,[165] Richmond Avenue School[166] (K-8; 357), Sovereign Avenue School[167] (PreK-8; 779), Texas Avenue School[168] (K-8; 635), Uptown School Complex[169] (K-8; 696) and Atlantic City High School[170] for grades 9–12 (2,327).[171][172] Students from Brigantine, Longport, Margate City and Ventnor City attend Atlantic City High School as part of sending/receiving relationships with the respective school districts.[173]

City public school students are also eligible to attend the Atlantic County Institute of Technology[174] or the Charter-Tech High School for the Performing Arts, located in Somers Point.[175]

Oceanside Charter School, which offers pre-kindergarten through eighth grade, was founded in 1999.[176]

Founded in 1908, Our Lady Star of the Sea Regional School is a Catholic elementary school, operated under the jurisdiction of the Diocese of Camden.[177][178]

Nearby college campuses include those of Atlantic Cape Community College and Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, the latter of which offers classes and resources in the city such as the Carnegie Library Center.

Sports

| Club | Sport | League | Venue | Year(s) |

| Atlantic City Diablos | Soccer | NPSL | St. Augustine College Preparatory School | 2007–2008 |

| Atlantic City Boardwalk Bullies | Ice Hockey | ECHL | Boardwalk Hall | 2001–2005 |

| Atlantic City CardSharks | Indoor football | NIFL | Boardwalk Hall | 2004 |

| Atlantic City Surf | Baseball | Can-Am League | Bernie Robbins Stadium | 1998–2008 |

| Atlantic City Seagulls | Basketball | USBL | Atlantic City High School | 1996–2001 |

On November 16, 2006, Hal Handel, CEO of Greenwood Racing, announced that the Atlantic City Race Course in Hamilton Township would increase live racing dates from four days per year, to up to 20 days per year.

The ShopRite LPGA Classic is an LPGA Tour women's golf tournament held near Atlantic City since 1986.

Media outlets

Newspapers and magazines

- The Press of Atlantic City

- Atlantic City Insiders

- Atlantic City Weekly

- Casino Connection

Radio stations

- WEHA 88.7 FM – Gospel

- WAYV 95.1 FM – Top 40

- WTTH 96.1 FM – Urban AC (The Touch)

- WFPG 96.9 FM – AC (Lite Rock 96.9)

- WENJ 97.3 FM – Sports

- WTKU 98.3 FM – Classic Hits (Kool 98.3)

- WZBZ 99.3 FM – Rhythmic (The Buzz)

- WZXL 100.7 FM – Rock (The Rock Station)

- WWAC 102.7 FM – Top 40 (AC 102.7)

- WMGM 103.7 FM – Mainstream Rock (WMGM Rocks)

- WSJO 104.9 FM – Hot AC (Sojo 104.9)

- WJSE 106.3 FM – Alternative

- WPUR 107.3 FM – Country (Cat Country 107.3)

- WWJZ 640 AM – Kids (Radio Disney)

- WMID 1340 AM – Oldies

- WOND 1400 AM – News/Talk

- WPGG 1450 AM – Talk

- WBSS 1490 AM – Sports

Television stations

Atlantic City is part of the Philadelphia television market. However, five stations and one repeater are licensed in the area.

- WACP Channel 4 Atlantic City (Independent)

- WQAV-CD Channel 34 Atlantic City (Asia Vision/Independent)

- WMGM-TV Channel 40 Wildwood (Soul of the South Network)

- WMCN-TV Channel 44 Atlantic City (Independent/Bounce TV on WMCN DT2)

- W60CX Channel 60 Atlantic City (TBN)

- WWSI Channel 62 Atlantic City (Telemundo)

Transportation

Roads and highways

As of May 2010[update], the city had a total of 103.67 miles (166.84 km) of roadways, of which 88.26 miles (142.04 km) were maintained by the municipality, 1.29 miles (2.08 km) by Atlantic County and 5.32 miles (8.56 km) by the New Jersey Department of Transportation and 8.80 miles (14.16 km) by the New Jersey Turnpike Authority.[179]

The three routes into Atlantic City are the Black Horse Pike/Harding Highway (US 322/40), White Horse Pike (US 30), and the Atlantic City Expressway. Atlantic City is roughly 132 miles (212 km) south of New York City by road (via the Garden State Parkway) and 55 miles (89 km) southeast of Philadelphia.[180]

Atlantic City has an abundance of taxi cabs and a local jitney providing continuous service to and from the casinos and the rest of the city.

Rail and bus

Atlantic City is connected to other cities in several ways. New Jersey Transit's Atlantic City Rail Terminal[181] at the Atlantic City Convention Center provides service from 30th Street Station in Philadelphia through several smaller South Jersey communities via the Atlantic City Line.[182]

On June 20, 2006, the board of New Jersey Transit approved a three-year trial of express train service between New York Penn Station and the Atlantic City Rail Terminal. The line, known as ACES (Atlantic City Express Service), ran from February 2009 and March 2012. The approximate travel time was 2½ hours with a stop at Newark's Penn Station and was part of the Casinos' multi-million dollar investments in Atlantic City. Most of the funding for the transit line was provided by Harrah's Entertainment (owners of both Harrah's Atlantic City and Caesars Atlantic City) and the Borgata.[183]

The Atlantic City Bus Terminal is the home to local, intrastate and interstate bus companies including New Jersey Transit, Academy and Greyhound bus lines. The Greyhound Lucky Streak Express offers service to Atlantic City from New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Boston, and Washington, D.C.[184]

Within the city, public transportation is provided by New Jersey Transit along 13 routes, including service between the city and the Port Authority Bus Terminal in Midtown Manhattan on the 319 route, and service to and from Atlantic City on routes 501 (to Brigantine Beach), 502 (to Atlantic Cape Community College), 504 (to Ventnor Plaza), 505 (to Longport), 507 (to Ocean City), 508 (to the Hamilton Mall), 509 (to Ocean City), 551 (to Philadelphia), 552 (to Cape May), 553 (to Upper Deerfield Township), 554 (to the Lindenwold PATCO station) and 559 (to Lakewood Township).[185][186]

The Atlantic City Jitney Association (ACJA) offers service on four fixed-route lines and on shuttles to and from the rail terminal.[187]

Airline service

Commercial airlines serve Atlantic City via Atlantic City International Airport, located 9 miles (14 km) northwest of the city in Egg Harbor Township. Many travelers also fly into Philadelphia International Airport or Newark Liberty International Airport, where there are wider selections of carriers from which to choose. The historic downtown Bader Field airport is now permanently closed and plans are in the works to redevelop the land.

Atlantic City International Airport is served by Spirit Airlines, a low-cost carrier that provides direct service to various destinations.

Infrastructure

Healthcare

The AtlantiCare Regional Medical Center is a health system based in Atlantic City. Founded in 1898, it includes two hospitals; the Atlantic City Campus and the Mainland Campus in Pomona, New Jersey. It has Atlantic City's only cancer institute, heart institute, and neonatal intensive care unit.

Utilities

South Jersey Industries provides natural gas to the city under the South Jersey Gas division. Marina Energy and its subsidiary, Energenic, a joint business venture with a long-time business partner, operate two Thermal plants in the city. The Marina Thermal Plant serves the Borgata while a second plant serves the Resorts Hotel and Casino.[188] Another Thermal plant is the Midtown Thermal Control Center on Atlantic and Ohio Avenues built by Conectiv.

Electrical power in Atlantic City as well as the surrounding area is primarily served by Atlantic City Electric, with power sources coming from the Beesley's Point Generating Station in Upper Township, as well as other locations.

The Jersey-Atlantic Wind Farm, opened in 2005, is the first onshore coastal wind farm in the United States.[190] In October 2010, North American Offshore Wind Conference was held in the city and included tours of the facility and potential sites for further development.[191] In February 2011, the state passed legislation permitting the construction of windmills for electricity along pre-existing piers, such as the Steel Pier.[192][193] The first phase of the Atlantic Wind Connection, a planned electrical transmission backbone along the Jersey Shore is planned to be operational in 2013.

The development of wind power in New Jersey could lead to the construction of the first American windfarm using offshore wind power off the coast at Atlantic City as early as 2012. In May 2011, Cape May-based Fisherman's Energy gained New Jersey approval for a demonstration project to build six wind turbines 2.5 miles (4.0 km) off the coast called "Fisherman's Atlantic City Windfarm".[194] The project still needs a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers permit before construction can begin. Sited in state waters, less than 3 nautical miles (5.6 km) from shore, it will not require other federal approval. It will have power generation capacity of less than 25 megawatts and will cost between $250 million to $300 million. The project may come on line late 2012, making the first commercial offshore wind farms in the USA,[195][196][197] earning the city the title of "Birthplace of Offshore Wind Energy in the Americas".[194]

In popular culture

In addition to the city's exposure in the HBO series Boardwalk Empire, Atlantic City has been featured in several other aspects of pop culture.

In video games

- The game, Omerta - City of Gangsters, takes place in Atlantic City during the Prohibition era. The protagonist immigrated from Sicily to Atlantic City to start a Rum-running operation and a criminal syndicate that is part of the Italian Mafia.

In film

- A majority of the 1972 film The King of Marvin Gardens takes place in a snow-covered Atlantic City prior to casino gambling.[198]

- Beaches with Bette Middler

- The 1980 movie, Atlantic City, took place in various parts of the city.[199]

- The 1984 movie Desperately Seeking Susan features some scenes shot in Atlantic City.

- The 1998 film, Snake Eyes, was set at a boxing match inside Trump Taj Mahal in Atlantic City.

- Part of the 2010 movie, The Bounty Hunter, takes place at the Borgata and Trump Taj Mahal.

- One of the early fights in the 2010 film, The Fighter, took place in Atlantic City.

- One of the fights in the 2011 movie, Warrior, takes place inside Boardwalk Hall, with the post-fight press conference taking place on the boardwalk and a pre-fight talk between the two brothers taking place on the beach outside Trump Plaza.

- The 1989 film Penn and Teller Get Killed was filmed on location in Atlantic City.[200]

- Rounders includes scenes filmed in the Taj Mahal poker room.[201]

In television

- The 1954 TV series On the Boardwalk with Paul Whiteman was shot at the Steel Pier in Atlantic City.[202]

- The 1960 animated TV series The Flintstones episode "The Buffalo Convention" has Fred and Barney fooling their wives, in order to go to the Water Buffalo Convention, which is being held at Frantic City.[203]

- The 1980 TV series Big Shamus, Little Shamus is set at a fictional Atlantic City casino, starring Brian Dennehy as a house detective.[204]

- The 1990 game show Trump Card was filmed at the Trump Castle.[205]

- The 2006 TV series How I Met Your Mother episode "Atlantic City" is set in Atlantic City.

- The 2009 series, "Life After People" showed the cities casinos, hotels, and boardwalk collapsing with no people to maintain the city. It is shown as being unrecognizable after 200 years, sooner than most cities due to hurricanes, salty air promoting corrosion, and rising sea levels.

- The 2010 TV series Boardwalk Empire is set primarily in Atlantic City.[206]

- Part of the 2012 Family Guy episode "Joe's Revenge" is set in Atlantic City.

- The 2002 Sex and The City episode "Luck Be An Old Lady" is set in Atlantic City

- The Real Housewives of New Jersey Season 2 Reunion was recorded on a set at Borgata.[207] The Season 1 episode, "Casinos and C-Cups" was also filmed in the city. Also promotional photo of original cast shot on Boardwalk.

- The 2004 The Simpsons episode "Catch 'Em If You Can" is set partly in Atlantic City.

- The Criminal Minds episode "The Uncanny Valley" (the twelfth episode of the show's fifth season) deals with a suspect with an unusual obsession in Atlantic City.[208]

- The Criminal Minds episode "Snake Eyes" (the thirteenth episode of the show's seventh season) deals with a spree killer operating in Atlantic City.[209]

- The 2011 Castle (TV series) episode "Heartbreak Hotel" is set partly in Atlantic City.[210]

In literature

- Harlan Coben's 2012 novel, Stay Close is almost entirely set in Atlantic City.

- Judy Blume's 1981 novel, Tiger Eyes, is partially set in Atlantic City; the family temporarily relocate to New Mexico after a tragic event.

- A Marvel Comics one-shot comic book starring Wolverine, entitled "Under The Boardwalk" takes place in Atlantic City in the form of one of the titular character's flashbacks.

- Imitation of Life – First appearing with a different title as a serialized novel in a periodical, later this best-seller by Fannie Hurst was twice interpreted by Hollywood. Set in early 20th century Atlantic City.[211]

In music

- The video for Detroit's Most Wanted's song The Money Is Made was filmed in Atlantic City and is considered the first rap video to ever be filmed in a casino. [212]

- The video for Gang Starr's 1992 hit song "Dwyck" featuring Nice & Smooth was filmed on the boardwalk. The song is considered[according to whom?] a Hip Hop Classic[opinion].

- The video for the Bruce Springsteen 1982 song "Atlantic City" begins with the demolition of the Blenheim Hotel, one of the old hotels in Atlantic City, then shows many of the early casinos in the city such as Caesars, Playboy, and an under-construction Harrah's.

Notable people

People who were born in, residents of, or otherwise closely associated with Atlantic City include:

- Hakeem Abdul-Shaheed (born 1959), convicted drug dealer and organized crime leader.[213]

- Jack Abramoff (born 1958), former lobbyist who was embroiled in high-profile political scandals. Abramoff was born in Atlantic City and lived there until age 10.[214]

- Robert Agnew (born 1953), professor of sociology at Emory University and president of the American Society of Criminology.[215]

- Joe Albany (1924–1988), jazz pianist.[216]

- James Avery (1948-2013), actor best known for portrayal of patriarch Philip Banks, Will Smith's character's uncle, in TV series The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.[217]

- Harry Bacharach (1873–1947), mayor of Atlantic City in 1912 for six months, again from 1916 to 1920, and again from 1930 to 1935.[218]

- Isaac Bacharach (1870–1956), represented New Jersey's 2nd congressional district from 1915 to 1937.[219]

- Edward L. Bader (1874–1927), mayor from 1920 to 1927.[220]

- Joseph Carleton Beal (1900–1967), co-writer of the Christmas song Jingle Bell Rock.[221]

- Edwin Blum (1906–1995), screenwriter for films Stalag 17 and The New Adventures of Tarzan.[222]

- Jack Boucher (1931–2012), photographer for National Park Service for more than 40 years beginning in 1958, chief photographer for the Historic American Buildings Survey.[223]

- Benjamin Burnley (born 1978), musician, best known as lead vocalist, rhythm guitarist and primary songwriter for band Breaking Benjamin.[224]

- Greg Buttle (born 1954), linebacker for New York Jets.[225]

- Harry Carroll (1892–1962), songwriter who composed music for "I'm Always Chasing Rainbows", "The Trail of the Lonesome Pine" and "By the Beautiful Sea".[226]

- Rosalind Cash (1938–1995), actress nominated for an Emmy Award for PBS production of Go Tell It on the Mountain.[227]

- Rocky Castellani (1926–2008), middleweight boxer best known for split-decision loss to Sugar Ray Robinson in which he knocked Robinson down in sixth round.[228]

- Vera Coking, property owner who prevailed in an effort by Donald Trump to acquire her boarding house using eminent domain.[229]

- Jack Collins (born 1943), Speaker of the New Jersey General Assembly from 1996 until 2002, making him the longest-serving speaker in Assembly history.[230]

- Alisa Cooper, commissioner of New Jersey Casino Control Commission since 2012, served since 2006 on Atlantic County Board of Chosen Freeholders.[231]

- Stuart Dischell (born 1954), poet and professor of English at University of North Carolina at Greensboro.[232]

- Frank S. Farley (1901–1977), member of New Jersey Legislature for 34 years, boss of Republican political machine that controlled the Atlantic City and Atlantic County governments.[233]

- Vera King Farris (1938–2009), third president of Richard Stockton College of New Jersey.[234]

- Chris Ford (born 1949), head coach of the Boston Celtics, Milwaukee Bucks, Los Angeles Clippers, and Philadelphia 76ers.[235]

- Helen Forrest (1917–1999), singer for three of the most popular big bands of the Swing Era, earning reputation as "the voice of the name bands."[236]

- John J. Gardner (1845–1921), represented New Jersey's 2nd congressional district from 1885 to 1893, mayor of Atlantic City 1868–1875.[237]

- Patsy Garrett (born 1921), actress.[238]

- Milton W. Glenn (1903–1967), represented New Jersey's 2nd congressional district from 1957 to 1965.[239]

- William Green (born 1979), NFL running back who played for the Cleveland Browns.[240]

- Marjorie Guthrie (1917–1983), dancer of the Martha Graham Company and dance teacher who was the wife of folk musician Woody Guthrie.[241]

- John R. Hargrove, Sr. (born 1923), federal judge appointed by President Ronald Reagan to the United States District Court for the District of Maryland.[242]