Cryptocurrency

A cryptocurrency (or crypto currency) is a digital asset designed to work as a medium of exchange using cryptography to secure the transactions and to control the creation of additional units of the currency.[1][2] Cryptocurrencies are classified as a subset of digital currencies and are also classified as a subset of alternative currencies and virtual currencies.

Bitcoin became the first decentralized cryptocurrency in 2009.[3] Since then, numerous cryptocurrencies have been created.[4] These are frequently called altcoins, as a blend of bitcoin alternative.[5][6] Bitcoin and its derivatives use decentralized control[7] as opposed to centralized electronic money/centralized banking systems.[8] The decentralized control is related to the use of bitcoin's blockchain transaction database in the role of a distributed ledger.[9]

Overview

Decentralized cryptocurrency is produced by the entire cryptocurrency system collectively, at a rate which is defined when the system is created and which is publicly known. In centralized banking and economic systems such as the Federal Reserve System, corporate boards or governments control the supply of currency by printing units of fiat money or demanding additions to digital banking ledgers. In case of decentralized cryptocurrency, companies or governments cannot produce new units, and have not so far provided backing for other firms, banks or corporate entities which hold asset value measured in it. The underlying technical system upon which decentralized cryptocurrencies are based was created by the group or individual known as Satoshi Nakamoto.[10]

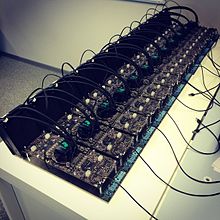

As of March 2015[update], hundreds of cryptocurrency specifications exist; most are similar to and derived from the first fully implemented decentralized cryptocurrency, bitcoin.[11][12] Within cryptocurrency systems the safety, integrity and balance of ledgers is maintained by a community of mutually distrustful parties referred to as miners: members of the general public using their computers to help validate and timestamp transactions adding them to the ledger in accordance with a particular timestamping scheme.[13]

The security of cryptocurrency ledgers is based on the assumption that the majority of miners are honestly trying to maintain the ledger, having financial incentive to do so.

Most cryptocurrencies are designed to gradually decrease production of currency, placing an ultimate cap on the total amount of currency that will ever be in circulation, mimicking precious metals.[1][14] Compared with ordinary currencies held by financial institutions or kept as cash on hand, cryptocurrencies can be more difficult for seizure by law enforcement.[1] This difficulty is derived from leveraging cryptographic technologies. A primary example of this new challenge for law enforcement comes from the Silk Road case, where Ulbricht's bitcoin stash "was held separately and ... encrypted."[15] Cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin are pseudonymous, though additions such as Zerocoin have been suggested, which would allow for true anonymity.[16][17][18]

History

In 1998, Wei Dai published a description of "b-money", an anonymous, distributed electronic cash system.[19] Shortly thereafter, Nick Szabo created "bit gold".[20] Like bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies that would follow it, Bit Gold was an electronic currency system which required users to complete a proof of work function with solutions being cryptographically put together and published. A currency system based on a reusable proof of work was later created by Hal Finney who followed the work of Dai and Szabo.

The first decentralized cryptocurrency, bitcoin, was created in 2009 by pseudonymous developer Satoshi Nakamoto. It used SHA-256, a cryptographic hash function, as its proof-of-work scheme.[13][21] In April 2011, Namecoin was created as an attempt at forming a decentralized DNS, which would make internet censorship very difficult. Soon after, in October 2011, Litecoin was released. It was the first successful cryptocurrency to use scrypt as its hash function instead of SHA-256. Another notable cryptocurrency, Peercoin was the first to use a proof-of-work/proof-of-stake hybrid.[22] IOTA was the first cryptocurrency not based on a block chain, and instead uses the Tangle.[23][24] Many other cryptocurrencies have been created though few have been successful, as they have brought little in the way of technical innovation.[25] On 6 August 2014, the UK announced its Treasury had been commissioned to do a study of cryptocurrencies, and what role, if any, they can play in the UK economy. The study was also to report on whether regulation should be considered.[26]

Publicity

Central bank representatives have stated that the adoption of cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin pose a significant challenge to central banks' ability to influence the price of credit for the whole economy.[27] They have also stated that as trade using cryptocurrencies becomes more popular, there is bound to be a loss of consumer confidence in fiat currencies.[28] Gareth Murphy, a senior central banking officer has stated "widespread use [of cryptocurrency] would also make it more difficult for statistical agencies to gather data on economic activity, which are used by governments to steer the economy". He cautioned that virtual currencies pose a new challenge to central banks' control over the important functions of monetary and exchange rate policy.[29]

Jordan Kelley, founder of Robocoin, launched the first bitcoin ATM in the United States on February 20, 2014. The kiosk installed in Austin, Texas is similar to bank ATMs but has scanners to read government-issued identification such as a driver's license or a passport to confirm users' identities.[30] By May 2017 1189 bitcoin ATMs were installed around the world with an average fee of 8.82%. An average of 3 bitcoin ATMs were being installed per day in May 2017.[31]

The Dogecoin Foundation, a charitable organization centered around Dogecoin and co-founded by Dogecoin co-creator Jackson Palmer, donated more than $30,000 worth of Dogecoin to help fund the Jamaican bobsled team's trip to the 2014 Olympic games in Sochi, Russia.[32] The growing community around Dogecoin is looking to cement its charitable credentials by raising funds to sponsor service dogs for children with special needs.[33]

Legality

The legal status of cryptocurrencies varies substantially from country to country and is still undefined or changing in many of them. While some countries have explicitly allowed their use and trade, others have banned or restricted it. Likewise, various government agencies, departments, and courts have classified bitcoins differently. China Central Bank banned the handling of bitcoins by financial institutions in China during an extremely fast adoption period in early 2014.[34] In Russia, though cryptocurrencies are legal, it is illegal to actually purchase goods with any currency other than the Russian ruble.[35]

On March 25, 2014, the United States Internal Revenue Service (IRS) ruled that bitcoin will be treated as property for tax purposes as opposed to currency. This means bitcoin will be subject to capital gains tax. One benefit of this ruling is that it clarifies the legality of bitcoin. No longer do investors need to worry that investments in or profit made from bitcoins are illegal or how to report them to the IRS.[36] In a paper published by researchers from Oxford and Warwick, it was shown that bitcoin has some characteristics more like the precious metals market than traditional currencies, hence in agreement with the IRS decision even if based on different reasons.[37]

Legal issues not dealing with governments have also arisen for cryptocurrencies. Coinye, for example, is an altcoin that used rapper Kanye West as its logo without permission. Upon hearing of the release of Coinye, originally called Coinye West, attorneys for Kanye West sent a cease and desist letter to the email operator of Coinye, David P. McEnery Jr. The letter stated that Coinye was willful trademark infringement, unfair competition, cyberpiracy, and dilution and instructed Coinye to stop using the likeness and name of Kanye West.[38]

Concerns of an unregulated global economy

As the popularity of and demand for online currencies increases since the inception of bitcoin in 2009,[39][40] so do concerns that such an unregulated person to person global economy that cryptocurrencies offer may become a threat to society. Concerns abound that altcoins may become tools for anonymous web criminals.[41]

Cryptocurrency networks display a marked lack of regulation that attracts many users who seek decentralized exchange and use of currency; however the very same lack of regulations has been critiqued as potentially enabling criminals who seek to evade taxes and launder money.

Transactions that occur through the use and exchange of these altcoins are independent from formal banking systems, and therefore can make tax evasion simpler for individuals. Since charting taxable income is based upon what a recipient reports to the revenue service, it becomes extremely difficult to account for transactions made using existing cryptocurrencies, a mode of exchange that is complex and (in some cases) impossible to track.[41]

Systems of anonymity that most cryptocurrencies offer can also serve as a simpler means to launder money. Rather than laundering money through an intricate net of financial actors and offshore bank accounts, laundering money through altcoins stands outside institutions and can be achieved through anonymous transactions.[41] Laundering services for cryptocurrency exist to service the bitcoin currency, in which multiple sourced bitcoins are blended to obscure the relationship between input and output addresses.[41]

Arrests

There have been arrests in the United States related to cryptocurrency. A notable case was the arrest of Charlie Shrem, the CEO of BitInstant.[42][43]

Fraud

On August 6, 2013, Magistrate Judge Amos Mazzant of the Eastern District of Texas federal court ruled that because cryptocurrency (expressly bitcoin) can be used as money (it can be used to purchase goods and services, pay for individual living expenses, and exchanged for conventional currencies), it is a currency or form of money. This ruling allowed for the SEC to have jurisdiction over cases of securities fraud involving cryptocurrency.[44]

GBL, a Chinese bitcoin trading platform, suddenly shut down on October 26, 2013. Subscribers, unable to log in, lost up to $5 million worth of bitcoin.[45][46]

In February 2014, cryptocurrency made national headlines due to the world's largest bitcoin exchange, Mt. Gox, declaring bankruptcy. The company stated that it had lost nearly $473 million of their customer's bitcoins likely due to theft. This was equivalent to approximately 750,000 bitcoins, or about 7% of all the bitcoins in existence. Due to this crisis, among other news, the price of a bitcoin fell from a high of about $1,160 in December to under $400 in February.[47]

On March 31, 2015, two now-former agents from the Drug Enforcement Administration and the U.S. Secret Service were charged with wire fraud, money laundering and other offenses for allegedly stealing bitcoin during the federal investigation of Silk Road, an underground illicit black market federal prosecutors shut down in 2013.[48]

On December 1, 2015, the owner of the now-defunct GAW Miners website was accused of securities fraud following his development of the cryptocurrency known as Paycoin. He is accused of masterminding an elaborate ponzi scheme under the guise of "cloud mining" with mining equipment hosted in a data center. He purported the cloud miners known as "hashlets" to be mining cryptocurrency within the Zenportal "cloud" when in fact there were no miners actively mining cryptocurrency. Zenportal had over 10,000 users that had purchased hashlets for a total of over 19 million U.S. dollars.[49][50]

On August 24, 2016, a federal judge in Florida certified a class action lawsuit[51] against defunct cryptocurrency exchange Cryptsy and Cryptsy's owner. He is accused of misappropriating millions of dollars of user deposits, destroying evidence, and is believed to have fled to China.[52]

Darknet markets

Cryptocurrency is also used in controversial settings in the form of online black markets, such as Silk Road. The original Silk Road was shut down in October 2013 and there have been two more versions in use since then; the current version being Silk Road 3.0. The successful format of Silk Road has been widely used in online dark markets, which has led to a subsequent decentralization of the online dark market. In the year following the initial shutdown of Silk Road, the number of prominent dark markets increased from four to twelve, while the amount of drug listings increased from 18,000 to 32,000.[41]

Darknet markets present growing challenges in regard to legality. Bitcoins and other forms of cryptocurrency used in dark markets are not clearly or legally classified in almost all parts of the world. In the U.S., bitcoins are labelled as "virtual assets". This type of ambiguous classification puts mounting pressure on law enforcement agencies around the world to adapt to the shifting drug trade of dark markets.[53]

Since most darknet markets run through Tor, they can be found with relative ease on public domains. This means that their addresses can be found, as well as customer reviews and open forums pertaining to the drugs being sold on the market, all without incriminating any form of user.[41] This kind of anonymity enables users on both sides of dark markets to escape the reaches of law enforcement. The result is that law enforcement adheres to a campaign of singling out individual markets and drug dealers to cut down supply. However, dealers and suppliers are able to stay one step ahead of law enforcement, who cannot keep up with the rapidly expanding and anonymous marketplaces of dark markets.[53]

Timestamping

Cryptocurrencies use various timestamping schemes to avoid the need for a trusted third party to timestamp transactions added to the blockchain ledger.

Proof-of-work schemes

The first timestamping scheme invented was the proof-of-work scheme. The most widely used proof-of-work schemes are based on SHA-256, which was introduced by bitcoin, and scrypt, which is used by currencies such as Litecoin.[22] The latter now dominates over the world of cryptocurrencies, with at least 480 confirmed implementations.[54]

Some other hashing algorithms that are used for proof-of-work include CryptoNight, Blake, SHA-3, and X11.

Proof-of-stake and combined schemes

Some cryptocurrencies use a combined proof-of-work/proof-of-stake scheme.[22][55] The proof-of-stake is a method of securing a cryptocurrency network and achieving distributed consensus through requesting users to show ownership of a certain amount of currency. It is different from proof-of-work systems that run difficult hashing algorithms to validate electronic transactions. The scheme is largely dependent on the coin, and there's currently no standard form of it.

Economics

Cryptocurrencies are used primarily outside existing banking and governmental institutions, and exchanged over the Internet. While these alternative, decentralized modes of exchange are in the early stages of development, they have the unique potential to challenge existing systems of currency and payments. As of June 2017[update] total market capitalization of cryptocurrencies is bigger than 100 billion USD and record high daily volume is larger than 6 billion USD.[56]

Competition in cryptocurrency markets

As of July 2017[update], there were over 900[57] digital currencies in existence.

Indices

In order to follow the development of the market of cryptocurrencies, indices keep track of notable cryptocurrencies and their cumulative market value.

Crypto index CRIX

The cryptocurrency index CRIX is a conceptual measurement jointly developed by statisticians at Humboldt University of Berlin, Singapore Management University and the enterprise CoinGecko and was launched in 2016.[58] The index represents cryptocurrency market characteristics dating back until July 31, 2014.[59][60] Its algorithm takes into account that the cryptocurrency market is frequently changing, with the continuous creation of new cryptocurrencies and infrequent trading of some of the existing ones.[61][62] Therefore, the number of index members is adjusted quarterly according to their relevance on the cryptocurrency market as a whole.[59] It is the first dynamic index reflecting changes on the cryptocurrency market.[citation needed]

List

Academic studies

Journals

In September 2015, the establishment of the peer-reviewed academic journal Ledger (ISSN 2379-5980) was announced. It will cover studies of cryptocurrencies and related technologies, and is published by the University of Pittsburgh.[63][64] The journal encourages authors to digitally sign a file hash of submitted papers, which will then be timestamped into the bitcoin blockchain. Authors are also asked to include a personal bitcoin address in the first page of their papers.[65][66]

Criticism

- Cryptocurrencies have been compared to Pyramid Schemes or to Economic bubbles, such as housing market bubbles.[67] Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital Management stated in 2017 that digital currencies were "nothing but an unfounded fad (or perhaps even a pyramid scheme), based on a willingness to ascribe value to something that has little or none beyond what people will pay for it", and compared them to the Tulip Mania (1637), South Sea Bubble (1720), and Dot.com bubble (1999).[68]

- In December 2013, Jason O'Grady reported on various pump and dump schemes in altcoins distinct from bitcoin and Litecoin.[69]

- Community refers to premining, hidden launches, or extreme rewards for the altcoin founders as a deceptive practice,[70] but it can also be used as an inherent part of a digital cryptocurrency's design, as in the case of Ripple.[71] Pre-mining means currency is generated by the currency's founders prior to mining code being released to the public.[72]

- Most cryptocurrencies are duplicates of existing cryptocurrencies with minor changes and no novel technical developments. One such, Coinye West, a comedy cryptocurrency alluding to the rapper Kanye West, was served a cease-and-desist letter on 7 January 2014, for using West's name and implying a connection that did not exist.[73]

- Banks generally do not offer services for cryptocurrencies and sometimes refuse to offer services to virtual-currency companies.[74]

- There are ways to permanently lose cryptocurrency from local storage due to malware or data loss. This can also happen through the destruction of the physical media, effectively removing lost cryptocurrencies forever from their markets.[75]

- There are many perceived criteria that cryptocurrencies must reach before they can become mainstream. For example, the number of merchants accepting cryptocurrencies is increasing, but still only a few merchants accept them.[76]

- With technological advancement in cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin, the cost of entry for miners requiring specialized hardware and software is high.[77]

- Cryptocurrency transactions are normally irreversible after a number of blocks confirm the transaction. One of the features cryptocurrency lacks in comparison to credit cards is consumer protection against fraud, such as chargebacks.[13] This is, however, a non-issue because third-party multisignature-based escrow can be used to mediate a transaction, this is effectively equivalent to enabling chargebacks. This is also much easier than performing an irreversible transaction using a system with native chargebacks, so this aspect is actually an advantage.

- Some coins may be a project with little to no community backing and no visible developer.[78]

- While cryptocurrencies are digital currencies that are managed through advanced encryption techniques, many governments have taken a cautious approach toward them, fearing their lack of central control and the effects they could have on financial security.[79]

- Environmentally conscious people are concerned with the enormous amount of energy that goes into cryptocurrency mining with little to show in return, but it is important to compare it to the consumption of the legacy financial system.[80] Some cryptocurrencies such as Ripple require no mining.

- Traditional financial products have strong consumer protections. However, if bitcoins are lost or stolen, there is no intermediary with the power to limit consumer losses.[81]

- Regulators in several countries have warned against their use and some have taken concrete regulatory measures to dissuade users.[82]

- The success of some cryptocurrencies has caused multi-level marketing schemes to arise with pseudo cryptocurrencies, such as Onecoin.[83]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Andy Greenberg (20 April 2011). "Crypto Currency". Forbes.com. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ Cryptocurrencies: A Brief Thematic Review. Social Science Research Network. Date accessed 28 august 2017.

- ^ Sagona-Stophel, Katherine. "Bitcoin 101 white paper" (PDF). Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 11 July 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Tasca, Paolo (7 September 2015). "Digital Currencies: Principles, Trends, Opportunities, and Risks". SSRN 2657598.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Altcoin". Investopedia. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ Wilmoth, Josiah. "What is an Altcoin?". cryptocoinsnews.com. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ McDonnell, Patrick "PK" (9 September 2015). "What Is The Difference Between Bitcoin, Forex, and Gold". NewsBTC. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ^ Allison, Ian (8 September 2015). "If Banks Want Benefits Of Blockchains, They Must Go Permissionless". NewsBTC. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ^ "All you need to know about Bitcoin". timesofindia-economictimes.

- ^ Economist Staff (31 October 2015). "Blockchains: The great chain of being sure about things". The Economist. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Listing of active coins". cryptocoincharts.info. 27 February 2014.

- ^ "Proof of burn (another authentication protocol forked from P.O.S." en.bitcoin.it. 7 June 2013.

- ^ a b c Jerry Brito and Andrea Castillo (2013). "Bitcoin: A Primer for Policymakers" (PDF). Mercatus Center. George Mason University. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ How Cryptocurrencies Could Upend Banks' Monetary Role, American Banker, 26 May 2013

- ^ The FBI's Plan For The Millions Worth Of Bitcoins Seized From Silk Road, Forbes, 4 October 2013

- ^ 'Zerocoin' Add-on For Bitcoin Could Make It Truly Anonymous And Untraceable, Forbes, 26 May 2013

- ^ Matthew Green (26 May 2013). "Zerocoin: Anonymous Distributed E-Cash from Bitcoin" (pdf). Johns Hopkins University.

- ^ This is Huge: Gold 2.0—Can code and competition build a better Bitcoin?, New Bitcoin World, 26 May 2013

- ^ Wei Dai (1998). "B-Money".

- ^ "Bitcoin: The Cryptoanarchists' Answer to Cash". IEEE Spectrum.

Around the same time, Nick Szabo, a computer scientist who now blogs about law and the history of money, was one of the first to imagine a new digital currency from the ground up. Although many consider his scheme, which he calls "bit gold," to be a precursor to Bitcoin

- ^ Bitcoin developer chats about regulation, open source, and the elusive Satoshi Nakamoto, PCWorld, 26-05-2013

- ^ a b c Wary of Bitcoin? A guide to some other cryptocurrencies, ars technica, 26-05-2013

- ^ Popov, Serguei (2016). "The Tangle Whitepaper" (PDF).

- ^ Sønstebø, David (2016). "IOTA First Chapter Synopsis".

- ^ "Are Any Altcoins Currently Useful? No, Says Monero Developer Riccardo Spagni". Bitcoin Magazines. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ "UK launches initiative to explore potential of virtual currencies". The UK News. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Central Banks Face 3 New Dilemmas in the Era of Bitcoin and Digital Currencies". Bitcoin Magazine. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ "How Bitcoin Compares to Fiat Currency's House of Cards". Bitcoin Magazine. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ decentralized currencies impact on central banks, rte News, 3 April 2014

- ^ First U.S. Bitcoin ATMs to open soon in Seattle, Austin, Reuters, 18 February 2014

- ^ https://coinatmradar.com/charts/

- ^ Dogecoin Users Raise $30,000 to Send Jamaican Bobsled Team to Winter Olympics, Digital Trends, 20 January 2014

- ^ Dogecoin Community Raising $30,000 for Children's Charity, International Business Times, 4 February 2014

- ^ "The Big Picture Behind the News of China's Bitcoin Bans – Bitcoin Magazine". Bitcoin Magazine. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ Bitcoin's Legality Around The World, Forbes, 31 January 2014

- ^ 3 Reasons The IRS Bitcoin Ruling Is Good For Bitcoin, Nasdaq, 24 March 2014

- ^ On the Complexity and Behaviour of Cryptocurrencies Compared to Other Markets, 7 November 2014

- ^ Infringement of Kayne West Mark and Other Violations, Pryor Cashman LLP, 6 January 2014

- ^ Iwamura, Mitsuru; Kitamura, Yukinobu; Matsumoto, Tsutomu (February 28, 2014). "Is Bitcoin the Only Cryptocurrency in the Town? Economics of Cryptocurrency And Friedrich A. Hayek". SSRN 2405790.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ doi:10.2139/ssrn.2405790

- ^ a b c d e f ALI, S, T; CLARKE, D; MCCORRY, P; Bitcoin: Perils of an Unregulated Global P2P Currency [By S. T Ali, D. Clarke, P. McCorry Newcastle upon Tyne: Newcastle University: Computing Science, 2015. (Newcastle University, Computing Science, Technical Report Series, No. CS-TR-1470)

- ^ Sidel, Robin. "Bitcoin Entrepreneur Charlie Shrem Reports to Prison".

- ^ "Tracking the Intangible: How Fraud Examiners Are Busting Bitcoin Fraud". Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ SEC v Shavers, United States District Court Eastern District Of Texas, 08-06-2013

- ^ "Banshee bitcoins: $5 million worth of bitcoin vanish in China". Russia Today. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ "When bitcoins go bad: 4 stories of fraud, hacking, and digital currencies". Washington Post. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ Mt. Gox Seeks Bankruptcy After $480 Million Bitcoin Loss, Carter Dougherty and Grace Huang, Bloomberg News, Feb. 28, 2014

- ^ Perez, Evan. "CNN Justice Reporter". CNN. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Farivar, Cyrus. "Pissed-off customers sue GAW Miners in proposed class-action suit". Ars Technica. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ Julian, Borax (27 July 2016). "Best Forex Brokers That Offer Bitcoin (BTC/USD) Trading". FXdailyReport.Com. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ^ "Liu v. Project Investors, Inc. et al (9:16-cv-80060), Florida Southern District Court".

- ^ http://cryptsyreceivership.com/v1/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Notice-of-Filing-Receivers-2nd-Report-8-2-16-full.pdf

- ^ a b Raeesi, Reza (2015-04-23). "The Silk Road, Bitcoins and the Global Prohibition Regime on the International Trade in Illicit Drugs: Can this Storm Be Weathered?". Glendon Journal of International Studies / Revue d'études internationales de Glendon. 8 (1–2). ISSN 2291-3920.

- ^ "CryptoCoinTalk.com - Discussing the World of Cryptocurrencies". CryptoCoinTalk. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ Sunny King, Scott Nadal (19 August 2012). "PPCoin: Peer-to-Peer Crypto-Currency with Proof-of-Stake" (PDF). Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ https://coinmarketcap.com/charts/

- ^ "coinmarketcap.com". Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ^ "CRIX—CRypto IndeX". crix.hu-berlin.de. Retrieved 2016-08-12.

- ^ a b Simon Trimborn; Wolfgang Karl Härdle. "CRIX or evaluating blockchain based currencies", ISSN 1860-5664, SFB 649 Discussion Paper 2016-021". SSRN 2800928.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "CRIX Discussion Paper" (PDF). crix.hu-berlin.de. June 15, 2016.

- ^ Ladislav Kristoufek (2 June 2014). "What are the main drivers of the Bitcoin price? Evidence from wavelet coherence analysis". p. 1 Section 1 Introduction, "(the) success has ignited an exposition of new alternative crypto-currencies.

- ^ "Crypto-Currency Market Capitalizations".

- ^ "Introducing Ledger, the First Bitcoin-Only Academic Journal". Motherboard.

- ^ "Bitcoin Peer-Reviewed Academic Journal 'Ledger' Launches". CoinDesk.

- ^ "Editorial Policies". ledgerjournal.org.

- ^ "How to Write and Format an Article for Ledger" (PDF). Ledger. 2015. doi:10.5195/LEDGER.2015.1.

- ^ McCrum, Dan (10 Nov 2015), "Bitcoin's place in the long history of pyramid schemes", www.ft.com

- ^ Kim, Tae (27 Jul 2017), "Billionaire investor Marks, who called the dotcom bubble, says bitcoin is a 'pyramid scheme'", www.cnbc.com

- ^ "A crypto-currency primer: Bitcoin vs. Litecoin". ZDNet. 14 December 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ "Scamcoins". August 2013.

- ^ Bradbury, Danny (25 June 2013). "Bitcoin's successors: from Litecoin to Freicoin and onwards". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ Morris, David Z (24 December 2013). "Beyond bitcoin: Inside the cryptocurrency ecosystem". CNNMoney, a service of CNN, Fortune & Money. Cable News Network. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ "Kanye West's lawyer orders "Coinye" to cease and desist just before launch". Ars Technica. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ Sidel, Robin (22 December 2013). "Banks Mostly Avoid Providing Bitcoin Services. Lenders Don't Share Investors' Enthusiasm for the Virtual-Currency Craze". Online.wsj.com. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ Keeping Your Cryptocurrency Safe, Center for a Stateless Society, 1 April 2014

- ^ The Future of Cryptocurrency, Investopedia, 10 September 2013

- ^ Want to make money off Bitcoin mining? Hint: Don't mine, The Week, 15 April 2013

- ^ Fundamental Analysis for Cryptocurrency, Wall Street Crypto, 10 January 2014

- ^ Cryptocurrency and Global Financial Security Panel at Georgetown Diplomacy Conf, MeetUp, 11 April 2014

- ^ Experiments in Cryptocurrency Sustainability, Let's Talk Bitcoin, March 2014

- ^ Four Reasons You Shouldn't Buy Bitcoins, Forbes, 3 April 2013

- ^ Schwartzkopff, Frances (17 December 2013). "Bitcoins Spark Regulatory Crackdown as Denmark Drafts Rules". Bloomberg. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ "Ponzi-like OneCoin trading scheme swindles many in Vietnam". Tuoi Tre News. 11 July 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

Further reading

- Chayka, Kyle (2 July 2013). "What Comes After Bitcoin?". Pacific Standard. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- Guadamuz, Andres; Marsden, Chris (2015). "Blockchains and Bitcoin: Regulatory responses to cryptocurrencies". First Monday. 20 (12). doi:10.5210/fm.v20i12.6198.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

External links

Media related to Cryptocurrency at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cryptocurrency at Wikimedia Commons