London Eye

| London Eye | |

|---|---|

| |

| Alternative names |

|

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Type | Ferris wheel |

| Location | Lambeth, London |

| Address | Riverside Building, County Hall, Westminster Bridge Road |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°30′12″N 0°07′10″W / 51.5033°N 0.1194°W |

| Completed | March 2000[1] |

| Opened |

|

| Cost | £70 million[3] |

| Owner | Merlin Entertainments |

| Height | 135 metres (443 ft)[4] |

| Dimensions | |

| Diameter | 120 metres (394 ft)[4] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) |

|

| Architecture firm | Marks Barfield[6] |

| Structural engineer | Arup[7] |

| Other designers |

|

| Awards and prizes | Institution of Structural Engineers Special Award 2001 |

| Website | |

| www | |

The London Eye is a giant Ferris wheel on the South Bank of the River Thames in London. It is Europe's tallest Ferris wheel,[10] is the most popular paid tourist attraction in the United Kingdom with over 3.75 million visitors annually,[11] and has made many appearances in popular culture.

The structure is 135 metres (443 ft) tall and the wheel has a diameter of 120 metres (394 ft). When it opened to the public in 2000 it was the world's tallest Ferris wheel. Its height was surpassed by the 525-foot (160 m) Star of Nanchang in 2006, the 165 metres (541 ft) Singapore Flyer in 2008, and the 550-foot tall (167.6 m) High Roller (Las Vegas) in 2014. Supported by an A-frame on one side only, unlike the taller Nanchang and Singapore wheels, the Eye is described by its operators as "the world's tallest cantilevered observation wheel".[12]

The London Eye offered the highest public viewing point in London[13] until it was superseded by the 245 metres (804 ft) high[14] observation deck on the 72nd floor of The Shard, which opened to the public on 1 February 2013.[15]

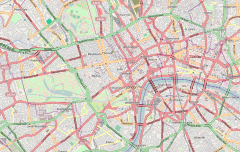

The London Eye adjoins the western end of Jubilee Gardens (previously the site of the former Dome of Discovery), on the South Bank of the River Thames between Westminster Bridge and Hungerford Bridge beside County Hall, in the London Borough of Lambeth.

History

Predecessor

A predecessor to the London Eye, the Great Wheel, was built for the Empire of India Exhibition at Earls Court and opened to the public on 17 July 1895.[16] Modelled on the original Chicago Ferris Wheel, it was 94 metres (308 ft) tall[17] and 82.3 metres (270 ft) in diameter.[18][19][20] It stayed in service until 1906, by which time its 40 cars (each with a capacity of 40 persons) had carried over 2.5 million passengers. The Great Wheel was demolished in 1907[21] following its last use at the Imperial Austrian Exhibition.[22]

Design and construction

The London Eye was designed by the husband-and-wife team of Julia Barfield and David Marks of Marks Barfield Architects.[23][24]

Mace was responsible for construction management, with Hollandia as the main steelwork contractor and Tilbury Douglas as the civil contractor. Consulting engineers Tony Gee & Partners designed the foundation works while Beckett Rankine designed the marine works.[25]

Nathaniel Lichfield and Partners assisted The Tussauds Group in obtaining planning and listed building consent to alter the wall on the South Bank of the Thames. They also examined and reported on the implications of a Section 106 agreement attached to the original contract, and also prepared planning and listed building consent applications for the permanent retention of the attraction, which involved the co-ordination of an Environmental Statement and the production of a planning supporting statement detailing the reasons for its retention.[26]

The rim of the Eye is supported by tensioned steel cables[27] and resembles a huge spoked bicycle wheel. The lighting was redone with LED lighting from Color Kinetics in December 2006 to allow digital control of the lights as opposed to the manual replacement of gels over fluorescent tubes.[28]

The wheel was constructed in sections which were floated up the Thames on barges and assembled lying flat on piled platforms in the river. Once the wheel was complete it was lifted into an upright position by a strand jack system made by Enerpac.[29] It was first raised at 2 degrees per hour until it reached 65 degrees, then left in that position for a week while engineers prepared for the second phase of the lift. The project was European with major components coming from six countries: the steel was supplied from the UK and fabricated in The Netherlands by the Dutch company Hollandia, the cables came from Italy, the bearings came from Germany (FAG/Schaeffler Group), the spindle and hub were cast in the Czech Republic, the capsules were made by Poma in France (and the glass for these came from Italy), and the electrical components from the UK.[30]

Opening

The London Eye was formally opened by then Prime Minister Tony Blair on 31 December 1999, but did not open to the paying public until 9 March 2000 because of a capsule clutch problem.[2]

The London Eye was originally intended as a temporary attraction, with a five year lease. In December 2001, operators submitted an application to Lambeth Council to give the London Eye permanent status, and the application was granted in July 2002.[31][32][33]

On 5 June 2008 it was announced that 30 million people had ridden the London Eye since it opened.[34]

Passenger capsules

|

|

Each of the 32 ovoidal capsules weighs 10 tonnes and can carry 25 people

| |

The wheel's 32 sealed and air-conditioned ovoidal passenger capsules, designed[35] and supplied[36] by Poma, are attached to the external circumference of the wheel and rotated by electric motors. Each of the 10-tonne (11-short-ton)[37] capsules represents one of the London Boroughs,[27] and holds up to 25 people,[38] who are free to walk around inside the capsule, though seating is provided. The wheel rotates at 26 cm (10 in) per second (about 0.9 kph or 0.6 mph) so that one revolution takes about 30 minutes. It does not usually stop to take on passengers; the rotation rate is slow enough to allow passengers to walk on and off the moving capsules at ground level.[37] It is, however, stopped to allow disabled or elderly passengers time to embark and disembark safely.[39]

In 2009 the first stage of a £12.5 million capsule upgrade began. Each capsule was taken down and floated down the river to Tilbury Docks in Essex.[40]

On 2 June 2013 a passenger capsule was named the Coronation Capsule to mark the sixtieth anniversary of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.[41]

Ownership and branding

Marks Barfield (the lead architects), The Tussauds Group, and British Airways were the original owners of the London Eye.[42] Tussauds bought out British Airways in 2005[42] and then Marks Barfield in 2006[43] to become sole owner.

In May 2007, the Blackstone Group purchased The Tussauds Group which was then the owner of the Eye; Tussauds was merged with Blackstone's Merlin Entertainments and disappeared as an entity.[44][45] British Airways continued its brand association, but from the beginning of 2008 the name British Airways was dropped from the logo.[46]

On 12 August 2009, the London Eye saw another rebrand, this time being called "The Merlin Entertainments London Eye" to showcase Merlin Entertainments' ownership. A new logo was designed for the attraction—this time taking the form of an eye made out of London's famous landmarks. This coincided with the launch of Merlin Entertainments 4D Experience preflight show underneath the ticket centre in County Hall. The refurbished ticket hall and 4D cinema experience were designed by architect Kay Elliott working with Merlin Studios project designer Craig Sciba. Merlin Studios later appointed Simex-Iwerks as the 4D theatre hardware specialists. The film was written and directed by 3D director Julian Napier and 3D produced by Phil Streather.[47]

In January 2011, a lighting-up ceremony marked the start of a three-year deal between EDF Energy and Merlin Entertainments.[48] On 1 August 2014 the logo was reverted to the previous "The Merlin Entertainments London Eye" version, with the name becoming simply "The London Eye".[citation needed]

In September 2014, Coca-Cola signed an agreement to sponsor the London Eye for two years, starting from January 2015. On the day of the announcement, the London Eye was lit in red.[49]

Financial difficulties

On 20 May 2005, there were reports of a leaked letter showing that the South Bank Centre (SBC)—owners of part of the land on which the struts of the Eye are located—had served a notice to quit on the attraction along with a demand for an increase in rent from £64,000 per year to £2.5 million, which the operators rejected as unaffordable.[50]

On 25 May 2005, London mayor Ken Livingstone vowed that the landmark would remain in London. He also pledged that if the dispute was not resolved he would use his powers to ask the London Development Agency to issue a compulsory purchase order.[51] The land in question is a small part of the Jubilee Gardens, which was given to the SBC for £1 when the Greater London Council was broken up.

The South Bank Centre and the British Airways London Eye agreed on a 25-year lease on 8 February 2006 after a judicial review over the rent dispute. The lease agreement meant that the South Bank Centre, a publicly funded charity, would receive at least £500,000 a year from the attraction, the status of which is secured for the foreseeable future.[31][52] Tussauds also announced the acquisition of the entire one-third interests of British Airways and Marks Barfield in the Eye as well as the outstanding debt to BA. These agreements gave Tussauds 100% ownership and resolved the debt from the Eye's construction loan from British Airways, which stood at more than £150 million by mid-2005 and had been increasing at 25% per annum.[53]

Critical reception

Sir Richard Rogers, winner of the 2007 Pritzker Architecture Prize, wrote of the London Eye in a book about the project:

The Eye has done for London what the Eiffel Tower did for Paris, which is to give it a symbol and to let people climb above the city and look back down on it. Not just specialists or rich people, but everybody. That's the beauty of it: it is public and accessible, and it is in a great position at the heart of London.[54]

Transport links

The nearest London Underground station is Waterloo, although Charing Cross, Embankment, and Westminster are also within easy walking distance.[55]

Connection with National Rail services is made at London Waterloo station and London Waterloo East station.

London River Services operated by Thames Clippers and City Cruises stop at the London Eye Pier.

References

- ^ "London Eye - Marks Barfield". marksbarfield.com.

- ^ a b c "London's big wheel birthday". CNN.com. 8 March 2001.

- ^ Reece, Damian (6 May 2001). "London Eye is turning at a loss". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ a b "Structurae London Eye Millennium Wheel". web page. Nicolas Janberg ICS. 2011. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ^ "The London Eye". UK Attractions.com. 31 December 1999. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ "About the London Eye". Archived from the original on 11 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "How big can Ferris wheels get?". Thoughts.arup.com. 23 September 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ^ Taylor, David (1 March 2001). "ISE rewards the biggest and best". The Architects' Journal.

- ^ "London Eye, UK".

- ^ Royal Mail Celebrates 10 Years of the London Eye Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The London Eye a complete visitor guide". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ "Merlin Entertainments Group". Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Up you come, the view's amazing... first look from the Shard's public gallery". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 31 December 2014

- ^ Shard observation deck to be Europe's highest

- ^ "Shard rakes in £5million from visitors to viewing platform in first year". London Evening Standard. 21 March 2014.

- ^ "The Ferris Wheel's London Rival". The New York Times. 21 July 1895.

- ^ "Spot the difference: London landmarks, then and now". standard.co.uk.

- ^ Anderson Norman. Ferris Wheels:An illustrated history. p. 97. ISBN 087972532X.

- ^ Richard Weingardt. Circles in the Sky: The Life and Times of George Ferris. p. 109. ISBN 0784410100.

- ^ Richard Moreno. A Short History of Carson City. p. 74. ISBN 0874178363.

- ^ "The Great Wheel, London - Building #4731". www.skyscrapernews.com.

- ^ Anderson Norman. Ferris Wheels:An illustrated history. p. 100. ISBN 087972532X.

- ^ Hibbert, Christopher (2011). The London Encyclopaedia (3rd Edition). London: Pan MacMillan. ISBN 9780230738782.

- ^ Rose, Steve (31 August 2007). "London Eye, love at first sight". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ Beckett Rankine – London Eye Pier Design Archived 16 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "NLP – Project:". Nlpplanning.com. Archived from the original on 21 March 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Making of The London Eye". Londoneye.com. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Color Kinetics Showcase London Eye". Colorkinetics.com. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ Enerpac strand jacks lift London Eye. Enerpac.com. Retrieved on 6 February 2012.

- ^ Mann, A. P.; Thompson, N.; Smits, M. (2001). "Building the British Airways London Eye". Proceedings of the ICE – Civil Engineering. 144 (2): 60–72. doi:10.1680/cien.2001.144.2.60.

- ^ a b Craig, Zoe (17 January 2017). "11 Fun Facts About The London Eye". Londonist. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "London Eye aims to go permanent". BBC News. 10 December 2001. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "London Eye 'to stay'". BBC News. 16 July 2002. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "All Eyes on Eighth Wonder: The London Eye greets 30 millionth visitor and joins Stonehenge and the Taj Mahal as a world wonder". londoneye.com. EDF Energy London Eye. June 2008. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ Ashby, Charles. (15 November 2011) High-flying deal for Leitner-Poma[permanent dead link]. Gjsentinel.com. Retrieved on 6 February 2012.

- ^ Colorado's Leitner-Poma to build cabins for huge observation wheel in Las Vegas. Denverpost.com. Retrieved on 6 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Interesting things you never knew about the London Eye". London Eye. Archived from the original on 30 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hester, Elliott (23 September 2007). "London's Eye in the sky not just a Ferris wheel". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 26 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Disabled Guests". London Eye.

- ^ Woodman, Peter (26 June 2009). "London Eye capsule taken away as refit starts". The Independent.

- ^ "Queen lookalike unveils Coronation Capsule at London Eye". london-se1.co.uk. 2 June 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ^ a b Reuters, From (6 March 2007). "Blackstone to buy Tussauds' parent". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Rose, Steve (27 March 2006). "Towering ambition". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "Merlin conjures up leaseback deal". The Daily Telegraph. 17 July 2007.

- ^ Cho, David (6 March 2007). "Blackstone Buys Madame Tussauds Chain". Washington Post.

- ^ "London Eye to get (another) new name". Evening Standard. 7 January 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "A new eye on London". London Eye. Archived from the original on 17 August 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "EDF Energy naming rights". Attractions Management. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ "Coca-Cola to sponsor London Eye". The Guardian. 16 September 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ "London Eye given eviction notice". BBC News. 20 May 2005. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ "Mayor's 'prat' jibe over Eye row". BBC News. 25 May 2005. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ "London Eye gets new 25-year lease". BBC News. 8 February 2006. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Marriner, Cosima (11 November 2005). "BA sells stake in London Eye to Tussauds for £95m". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ Marks Barfield Architects (2007). Eye: The story behind the London Eye. London: Black Dog Publishing.

- ^ How to get here Archived 13 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- Use British English from August 2007

- Ferris wheels

- Amusement rides introduced in 2000

- Merlin Entertainments Group

- Buildings and structures celebrating the third millennium

- Buildings and structures in the London Borough of Lambeth

- Buildings and structures on the River Thames

- Tourist attractions in the London Borough of Lambeth

- Privately owned public spaces

- 2000 establishments in England