Austin, Minnesota

Austin, Minnesota | |

|---|---|

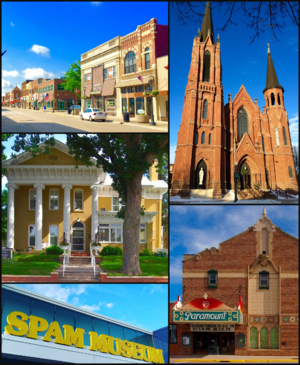

Clockwise from top: day city,ca St. Augustine's Church, Paramount Theater, Spam Museum, Hormel Historic Home | |

| Nickname: SPAM Town USA | |

| |

| Coordinates: 43°40′12″N 92°58′50″W / 43.67000°N 92.98056°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Minnesota |

| County | Mower |

| Platted | Spring of 1856 |

| Incorporated as a village | March 6, 1868 |

| Incorporated as a city | February 28, 1871 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Stephen M. King |

| Area | |

| • City | 13.39 sq mi (34.7 km2) |

| • Land | 13.29 sq mi (34.4 km2) |

| • Water | 0.11 sq mi (0.3 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,211 ft (369 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 26,174 |

| • Estimate (2022)[4] | 26,208 |

| • Density | 1,972.45/sq mi (761.57/km2) |

| • Urban | 25,479 |

| • Metro | 40,140 (US: 315th) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 55912 |

| Area code | 507 |

| FIPS code | 27-02908[5] |

| GNIS | 2394037[2] |

| Website | ci |

Austin is a city in and the county seat of Mower County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 26,174 at the 2020 census.[3] The town was originally settled along the Cedar River and has two artificial lakes, East Side Lake and Mill Pond. It was named for Austin R. Nichols, the area's first European settler.[6]

Hormel Foods Corporation is Austin's largest employer, and the city is sometimes called "SPAM Town USA".[7] Austin is home to Hormel's corporate headquarters, a factory that makes most of North America's SPAM tinned meat, and the Spam Museum. Austin is also home to the Hormel Institute, a leading cancer research institution operated by the University of Minnesota with significant support from the Mayo Clinic.[8]

History

[edit]

Fertile land, trapping, and ease of access brought first trappers and then the early pioneers to this region. The rich gameland attracted Austin Nichols, a trapper who built the first log cabin in 1853.[9] At that time there were "about twenty families in the area."[6] More settlers began to arrive by wagon train in 1855, and by 1856 enough people were present to organize Mower County.[6] In 1856 the settlement adopted the name "Austin", in honor of its first settler. That year the first hotel opened to travelers and the first physician, Dr. Ormanzo Allen, moved to town. The first newspaper, the Mower County Mirror, was started in 1858.[6]

Mills, powered by the Cedar River, were the first industries in Austin. They provided much-needed flour and lumber. Growth was slow during the first two decades, but the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railroad arrived in the late 1860s, hastening economic development.[6] The town's first schoolhouse was constructed in 1865, and the first bank opened the following year.

In 1891 George A. Hormel opened a small family-owned butcher shop in Austin,[10] which eventually grew into today's Fortune 500 company, Hormel Foods. By 1896 area doctors, with the help of local Lutheran congregations, formed the Austin Hospital Association, later becoming St. Olaf Hospital, and (since 1995) part of Mayo Clinic Health System.[6][11]

In 1897 Charles Boostrom opened Austin's first college, the Southern Minnesota Normal College and Austin School of Commerce. It closed in 1925, and the city was without an institution of higher education until Austin Junior College opened in 1940. In 1964 it became part of the State College and University System and is now Riverland Community College.

In 1913 the Minnesota Legislature made a 50-acre (20 ha) parcel of land into Horace Austin State Park. At the time, the land was "one of the beauty spots of Southern Minnesota, but of late years has not been cared for and in places the banks have been disfigured by dumping along the shore of the stream," according to the bill's author, Senator Charles F. Cook.[12] The park was converted to a state "scenic wayside" in 1937, then transferred to city ownership in 1949.

In the 1930s Austin Acres was built with funding from the Subsistence Homesteads Division of the Department of the Interior.[13] The Austin Parks Board was formed in the 1940s to oversee the growing number of green spaces within the city.

In 1971 the Jay C. Hormel Nature Center, a 500-acre (200 ha) nature preserve also including the 60-acre (24 ha) Hormel Arboretum, was purchased from Geordie Hormel with a state grant. In 1973 the city opened Riverside Arena, the city's first indoor ice arena, now home to a variety of ice activities including the Austin Bruins junior hockey team.

In August 1985, 1,500 Hormel meatpackers went on strike at the Austin plant after management demanded a 23% cut in wages. In the early 1980s, recession had impacted several meatpacking companies, decreasing demand and increasing competition which led smaller and less-efficient companies to go out of business. In an effort to keep plants from closing, many instituted wage cuts. Wilson Food Company declared bankruptcy in 1983, allowing them to cut wages from $10.69 to $6.50 and significantly reduce benefits. Hormel Foods had avoided such drastic action, but by 1985, pressure to stay competitive remained.[14] A protracted battle between union employees and Hormel continued until June 1986, one of the longest labor struggles of the 1980s. In January 1986 some workers crossed the picket lines, leading to riots; the conflict escalated to such a point that Governor Rudy Perpich called in the National Guard to keep the peace.[15] The strike received national attention and a documentary, American Dream, was filmed during the 10-month conflict. The movie was released in 1990 and won Best Documentary Feature at the 63rd Annual Academy Awards.[16] Dave Pirner of the Minneapolis band Soul Asylum wrote a song about the strike, "P-9". It is on the band's 1989 album Clam Dip & Other Delights. Hormel never gave in to the workers' demands, and when the strike ended in June 1986, 700 employees were left without work.[17]

21st century

[edit]

Austin completed a new $28 million courthouse and jail in 2010, a new intermediate school in 2013, and has a major redevelopment project at the site of the former Oak Park Mall.[18][19]

The city is embarking on a community development project, Vision 2020. This grassroots movement was chartered in 2011 to implement ten major new community initiatives that could be completed by 2020. It includes a variety of projects related to economic development, heath and wellness, education, and tourism. A community recreation center is in progress, as is a tourism and visitor center.[20] One goal is to make the downtown business district more of a destination, aided in part by the Spam Museum's relocation to Main Street in 2016.[19]

In 2015 the National Association of Realtors named Austin one of the "Top 10 Affordable Small Towns Where You'd Actually Want to Live."[21]

Major floods

[edit]

Austin has a long history of flooding. The Cedar River, along with Dobbins Creek and Turtle Creek, flow through Austin, and many homes and businesses were constructed in floodplains. A series of floods between 1978 and 2010 resulted in a major flood mitigation program. This involved the purchase and demolition of buildings within the floodplain, converting low-lying areas of town to parks, and the installation of a flood wall to protect downtown.[22]

After two major floods in July 1978, city officials and local residents decided to take action. Locals organized the Floodway Action Citizens Task Source (FACTS), which met with local and state leaders, as well as members of the Army Corps of Engineers, but it was decided that major flood prevention measures would not be cost-effective. A Community Development Block Grant was won from the Department of Housing and Urban Development, allowing for the buyout of homes lying in the flood plain. City planners also vowed to no longer build new structures in the existing flood plains. In 1983 and 1993 major floods again damaged many Austin homes and businesses. Over 400 homes were affected and a new round of buyouts took place through the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP).

The worst flooding on record came when the Cedar River crested at 23.4 feet (7.1 m) in the spring of 2000. Many of the worst-hit parts of town were now void of homes and businesses, but there was still damage and extensive clean-up was required. Flooding came again in September 2004, resulting in two fatalities. Additional protection (dikes) were added along the Cedar River as a result.

The most recent round of serious flooding came in 2010, after which a plan was developed for a permanent flood wall to protect downtown from the floodwaters of the Cedar River and Mill Pond. The wall was completed in 2014.[22][23][24]

Major tornadoes

[edit]

On Monday, August 20, 1928, an F-2 sized tornado touched down on Winona Street (1st Avenue). The damage ran from the southern edge of Austin High School to the Milwaukee Road railyards on the city's east side. St. Olaf Lutheran Church, Carnegie Library, Main Street, the spire on Austin's former courthouse, Grand Theatre (replaced in 1929 by the Paramount Theatre), Austin Utilities, Lincoln School, and several boxcars at the Milwaukee railyards were damaged or destroyed. Austin residents noticed debris raining out of the sky, such as straw and laundry.

Another F-2 touched down in August 1961, at 808 18th Street SW. It quickly gained strength once on the ground, becoming an F-3 at 17th Street SW, where it destroyed a garage. The twister lifted briefly, touching down in the city fairgrounds and hitting the grandstand roof, tearing off parts and damaging beams.

In the summer of 1984, a tornado destroyed Echo Lanes Bowling Alley as it swept through southeast Austin. Neighboring Bo-Dee Campers also suffered considerable damage, and Schmidt TV was destroyed.

A tornado or straight-line winds took down massive amounts of branches and trees on Saturday, June 27, 1998, uprooting smaller trees and knocking large branches across streets. Several side streets in northwest Austin became impassable, including 8th Avenue NW (near Sumner Elementary School) and 14th Street NW (between I-90 and 8th Avenue). The event caused disruption in Sunday church services the next morning, and many congregations organized cleanup activities instead of regularly scheduled events.

A tornado touched down in Glenville on May 1, 2001, gaining strength before it turned into a F-3 headed for Austin. The twister dissipated shortly after hitting town, but did notable damage in both cities.

On Wednesday, June 17, 2009, an EF2 tornado touched down outside Austin and moved across the northwest and northern parts of the city, gradually weakening as it moved east. The worst damage in Austin was about 3 miles (5 km) north of downtown. The visitors center at the Jay C. Hormel Nature Center sustained damage, losing 300 trees. There were a few minor injuries.[25][26]

Geography

[edit]

by the Austin Municipal Airport

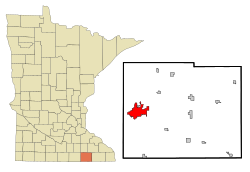

Austin is in western Mower County in southeastern Minnesota. It is 20 miles (32 km) east of Albert Lea, 41 miles (66 km) southwest of Rochester, 100 miles (160 km) south of Minneapolis, and 12 miles (19 km) north of the Iowa border. The city is bordered to the south by Austin Township, to the east by Windom and Red Rock townships, and to the north by Lansing Township and the city of Mapleview. Austin is bordered to the west by Oakland Township in Freeborn County.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Austin has a total area of 13.39 square miles (34.68 km2), of which 13.29 square miles (34.42 km2) are land and 0.11 square miles (0.28 km2), or 0.79%, are water.[1] Its elevation is approximately 1,200 ft (370 m). The Cedar River, a tributary of the Iowa River, flows southward through the east side of the city. Tributaries within the city include Turtle Creek from the west and Dobbins Creek from the east.

Climate

[edit]Austin has a humid continental climate typical of the Upper Midwest. Winters are cold and snowy; summers are warm with moderate to high humidity. On the Köppen climate classification, Austin falls in the humid continental climate zone (Dfa) and is in USDA plant hardiness zone 4b.[27][28] Below is a table of average high and low temperatures in Austin.

| Climate data for Austin, Minnesota (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1938–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 62 (17) |

71 (22) |

80 (27) |

91 (33) |

100 (38) |

100 (38) |

102 (39) |

101 (38) |

97 (36) |

92 (33) |

79 (26) |

65 (18) |

102 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 40.9 (4.9) |

45.0 (7.2) |

63.8 (17.7) |

79.1 (26.2) |

86.8 (30.4) |

91.4 (33.0) |

90.5 (32.5) |

88.7 (31.5) |

87.0 (30.6) |

80.8 (27.1) |

63.0 (17.2) |

45.8 (7.7) |

93.6 (34.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 21.9 (−5.6) |

26.4 (−3.1) |

39.2 (4.0) |

54.9 (12.7) |

67.5 (19.7) |

77.6 (25.3) |

80.8 (27.1) |

78.7 (25.9) |

72.2 (22.3) |

58.3 (14.6) |

41.5 (5.3) |

27.9 (−2.3) |

53.9 (12.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 13.7 (−10.2) |

17.8 (−7.9) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

45.0 (7.2) |

57.5 (14.2) |

67.9 (19.9) |

71.0 (21.7) |

68.7 (20.4) |

61.1 (16.2) |

47.9 (8.8) |

33.1 (0.6) |

20.5 (−6.4) |

44.6 (7.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 5.4 (−14.8) |

9.1 (−12.7) |

22.7 (−5.2) |

35.2 (1.8) |

47.5 (8.6) |

58.2 (14.6) |

61.2 (16.2) |

58.7 (14.8) |

50.0 (10.0) |

37.5 (3.1) |

24.7 (−4.1) |

13.0 (−10.6) |

35.3 (1.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −18.6 (−28.1) |

−13.2 (−25.1) |

−1.5 (−18.6) |

19.2 (−7.1) |

31.9 (−0.1) |

44.9 (7.2) |

49.4 (9.7) |

46.7 (8.2) |

33.3 (0.7) |

20.9 (−6.2) |

6.2 (−14.3) |

−10.2 (−23.4) |

−21.4 (−29.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −42 (−41) |

−34 (−37) |

−34 (−37) |

5 (−15) |

22 (−6) |

31 (−1) |

41 (5) |

34 (1) |

20 (−7) |

10 (−12) |

−25 (−32) |

−33 (−36) |

−42 (−41) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.12 (28) |

1.10 (28) |

2.03 (52) |

3.67 (93) |

4.99 (127) |

5.07 (129) |

4.85 (123) |

4.07 (103) |

3.60 (91) |

2.63 (67) |

1.84 (47) |

1.25 (32) |

36.22 (920) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 11.0 (28) |

10.4 (26) |

7.5 (19) |

2.2 (5.6) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

2.3 (5.8) |

9.3 (24) |

43.4 (110) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 9.5 (24) |

12.5 (32) |

10.0 (25) |

1.6 (4.1) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.5 (3.8) |

8.2 (21) |

16.3 (41) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 5.9 | 5.3 | 7.1 | 10.9 | 13.0 | 11.7 | 10.7 | 10.3 | 9.3 | 9.4 | 6.1 | 6.6 | 106.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 6.4 | 5.5 | 3.5 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 2.5 | 6.0 | 25.6 |

| Source: NOAA[29][30] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 200 | — | |

| 1870 | 2,039 | 919.5% | |

| 1880 | 2,305 | 13.0% | |

| 1890 | 3,901 | 69.2% | |

| 1900 | 5,474 | 40.3% | |

| 1910 | 6,960 | 27.1% | |

| 1920 | 10,118 | 45.4% | |

| 1930 | 12,276 | 21.3% | |

| 1940 | 18,307 | 49.1% | |

| 1950 | 23,100 | 26.2% | |

| 1960 | 27,908 | 20.8% | |

| 1970 | 25,074 | −10.2% | |

| 1980 | 23,020 | −8.2% | |

| 1990 | 21,907 | −4.8% | |

| 2000 | 23,314 | 6.4% | |

| 2010 | 24,718 | 6.0% | |

| 2020 | 26,174 | 5.9% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 26,208 | [4] | 0.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[31] 2020 Census[3] | |||

2020 census

[edit]As of the census of 2020 there were 26,174 people, 10,980 households, and 10,181 families residing in the city.

2010 census

[edit]As of the census of 2010 there were 24,718 people, 10,131 households, and 6,114 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,096.5 inhabitants per square mile (809.5/km2). There were 10,870 housing units at an average density of 922.0 per square mile (356.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 86.8% White, 3.0% African American, 0.3% Native American, 2.4% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 4.8% from other races, and 2.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 15.4% of the population.

There were 10,131 households, of which 30.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.9% were married couples living together, 11.1% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 39.7% were non-families. 33.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.39 and the average family size was 3.05.

The median age in the city was 37. 25.6% of residents were under 18; 8.8% were between 18 and 24; 24.3% were from 25 to 44; 23.5% were from 45 to 64; and 17.7% were 65 or older. The city was 49.2% male and 50.8% female.

2000 census

[edit]As of the census of 2000, there were 23,314 people, 9,897 households, and 6,076 families residing in the city and 10,261 housing units. The racial makeup of the city was 92.6% White, 0.81% African American, 0.18% Native American, 2.22% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 3.09% from other races, and 1.09% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race was 6.12% of the population. There were 9,897 households, out of which 27.2% had children under the age of 18. The average household size was 2.29; the average family size was 2.90. The median income for a household in the city was $33,750, and the median income for a family was $42,691. Males had a median income of $31,787 versus $23,158 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,651. About 7.5% of families and 10.9% of the population were below the poverty line.

Economy

[edit]

With Hormel's corporate headquarters and main production facility in Austin, food processing plays a dominant role in the city's economy. Hormel and Quality Pork Processors, a contract food processing firm serving Hormel, are by far the city's largest private employers.[32] Though most famous for SPAM, Hormel also produces many other brands, such as Jennie-O turkey, Muscle Milk, Skippy peanut butter, and Dinty Moore beef stew.[33]

The government, education, hospitality, and retail sectors comprise much of the remainder of Austin's employment base.

Hormel's consistent and steady growth have resulted in below-average unemployment rates for Austin and Mower County in recent years. As of February 2016 the unemployment rate was 3.7% in Austin and Mower County, below both the state and national average.[34][35]

Austin-area businesses and community actively supported an application to participate as a test community in the Google Fiber project, begun in 2010.[36] Though unsuccessful in their bid, the adoption of high-speed fiber optic and wireless internet throughout Austin is one of the Vision 2020 committee's goals.[37]

Austin's retail business struggled during the Great Recession, including the demise of the Oak Park Mall. As of 2017 the business climate had improved, including a major redevelopment of the former mall site. Downtown remains vibrant as well, including construction of a new SPAM Museum in 2016.

Top employers

[edit]

According to Austin's Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (2022),[38] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hormel Foods | 3,255 |

| 2 | Quality Pork Processors | 1,225 |

| 3 | Mayo Clinic Health System | 900 |

| 4 | Austin Public Schools ISD No. 492 | 850 |

| 5 | Walmart | 325 |

| 6 | Hy-Vee | 300 |

| 7 | Mower County | 274 |

| 8 | Riverland Community College | 240 |

| 9 | City of Austin | 219 |

| 10 | Cedar Valley Services | 192 |

Arts and culture

[edit]

Music

Austin is home to several long-standing performing arts organizations, including the Austin Symphony Orchestra, which was established in 1957.[39] The Austin Artist Series, one of the Midwest's largest and longest-running concert and performance series, was established in 1945.[40] The Historic Paramount Theatre hosts a variety of local and regional performances,[41] and Austin High School's music programs have been recognized for decades as among the state's best. Austin is also home to a community choir (Northwestern Singers[42]) and several community bands (Austin Community Band, Austin Community Jazz Band,[43] and the Austin Big Band[44]). Austin has produced many professional musicians of regional and national acclaim, including John Maus, Trace Bundy, Charlie Parr, Martin Zellar, Matthew Griswold, and Molly Kate Kestner.

In 2015 the MacPhail Center for Music, based in Minneapolis, Minnesota, opened its first outstate location in Austin, at Riverland Community College. MacPhail's Austin campus provides individual instruction on nearly a dozen musical instruments for adults and children, as well as large ensembles and early childhood music instruction.[45]

Theater

The Frank W. Bridges Theatre is home to an active theatre program at Riverland Community College, while Matchbox Children's Theatre, established in 1975, provides shows year-round for both adults and children.[46] Summerset Theatre, a community theater company organized in 1968, also presents several shows per year.[47]

ArtWorks Center

The Austin ArtWorks Center, established in 2014, hosts gallery exhibits, educational classes, performance space, and a retail gallery. It is operated by the Austin Area Commission for the Arts, which also sponsors the Austin ArtWorks Festival, an annual celebration of visual, performing, and literary arts.[48] The center is in the First National Bank Building, which opened in 1896.[49]

Architecture

Austin has several historically and architecturally significant buildings, including Austin High School, St. Augustine's Church, Roosevelt Bridge, the Historic Paramount Theatre, the Hormel Historic Home, the Arthur W. Wright House, and several blocks of buildings on Main Street.

The S. P. Elam Residence (1950) was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, and is the second largest example of his Usonian style of architecture.[50]

Literature

Austin is the setting of Allen Eskens' novel The Life We Bury, published in 2014 by Seventh Street Books in New York.

Places of interest

[edit]

- Mower County Fairgrounds and Mower County Fair

- Buffy the Cow

- SPAM Museum

- Jay C. Hormel Nature Center

- Hormel Historic Home

- St. Augustine's Church

- Austin ArtWorks Center

- Austin High School and Knowlton Auditorium

- Mower County Historical Society

- Historic Paramount Theatre

- Sola Fide Observatory

- East Side Lake

- Bandshell Community Park

- Todd Park

- Austin Country Club (private)

- Meadow Greens Golf Course (public)

- The Elam House (Frank Lloyd Wright home)

- Christ Episcopal Church

- Packer Dome (seasonal)

- Vintage Bicycle Collection at Rydjor Bike Shop

- Hormel Institute

- Roosevelt Bridge

Sports

[edit]

The Austin Bruins are a North American Hockey League team that began play during the 2010–11 season. The team finished 1st in the Central Division in the 2012–13, 2013–14, and 2014–15 seasons, and advanced to the Robertson Cup Finals in 2014 and 2015, though ultimately losing the championship both times. The Bruins play their home games at Riverside Arena. Austin previously was represented in Junior hockey by the Austin Mavericks, a team that first participated in the Midwest Junior Hockey League from 1974 to 1977 and following a league merger competed in the United States Hockey League from 1977 to 1985.

Austin is home to two amateur baseball clubs, the Austin Blue Sox and Austin Greyhounds. The Riverland Community College Blue Devils field six intercollegiate athletic teams.[51]

Several other teams, clubs, and activities are prominent in Austin, including the Southern Minnesota Bicycling Club,[52] the Austin Curling Club,[53] the Minnesota Southbound Rollers (female roller derby),[54] and the Southeast Minnesota Warhawks of the Southern Plains Football League.[55]

Riverside Arena

[edit]

The Riverside Arena is a 2,500-seat multipurpose arena which opened in 1973.[56] It is home to the Austin High School Packers boys' and girls' ice hockey teams as well as the Austin Bruins.

In 2010, a Jumbotron, lasers and upgraded lighting were installed.[57] The rink underwent a major overhaul in 2015 when the concrete surface was relaid and the original cooling and dehumidifying equipment replaced.[58]

Packer Dome

[edit]Packer Dome, a seasonal athletic facility built in 2015, provides sport and recreation facilities in Austin. It is operated by Austin Public Schools and was funded in large part by the Hormel Foundation as part of the Vision 2020 community development project.[59][60]

Parks and recreation

[edit]Austin has an extensive network of 28 parks and green spaces, which the Department of Parks, Recreation, and Forestry oversees. These range from small, passive spaces like Sterling Park (manicured but lacking recreational equipment) to the 507-acre Jay C. Hormel Nature Center.

Jay C. Hormel Nature Center

[edit]Established in 1971, the Hormel Nature Center is in western Mower County, within Austin's city limits. It features restored and remnant prairie, hardwood forest, wetlands and meandering streams. There are more than ten miles of trail, giving visitors the opportunity to see deer, mink, raccoons, salamanders, many different birds and other native wildlife. It features an Interpretive Center, open daily, where visitors can learn about the history and biology of the area through hands-on exhibits, interactive displays and live educational animals. The Nature Center offers equipment rental throughout most of the year: canoes and kayaks in the summer and cross-country skis and snowshoes while snow conditions are good.[61]

Other parks

[edit]Horace Austin Park, in downtown, is the most centrally located and has a blend of modern amenities, including playground equipment, the municipal pool, and trails and green spaces surrounding Mill Pond.[62] Austin has parks in all four of its quadrants and many are connected by a trail system, including three of the largest: Bandshell Community Park, Driesner Park, and Todd Park. Todd Park is a popular summer recreation space, with several sand volleyball courts and 11 softball and baseball diamonds.[63]

Bandshell Community Park is the site of Austin's annual Independence Day celebration, which draws thousands of residents for two days of music, carnival games, and evening fireworks.[63][64][65]

Government and politics

[edit]

| Mayor | Stephen M. King | term ends in 2024 |

| Council: At-large | Jeff Austin | term ends in 2022 |

| Council: 1st Ward | Oballa Oballa | term ends in 2023 |

| Council: 1st Ward | Rebecca Waller | term ends in 2022 |

| Council: 2nd Ward | Michael Postma | term ends in 2024 |

| Council: 2nd Ward | Jason Baskin | term ends in 2022 |

| Council: 3rd Ward | Paul Fischer | term ends in 2024 |

| Council: 3rd Ward | Joyce Poshusta | term ends in 2022 |

The city is independent from Austin Township to the south and Lansing Township to the north.

Austin is in Minnesota's 1st congressional district, represented by Brad Finstad, a Republican.[66] It is in Minnesota Senate District 27, represented by Republican Gene Dornink,[67] and House District 27B, represented by Republican Patricia Mueller. Mueller is an Austin resident.

Austin is the seat of Mower County and home to the Mower County Justice Center (courthouse) and Jail. Two new buildings were completed in 2010, a $28 million campus in downtown Austin.[68]

The city of Austin is led by a mayor-council form of government. All terms are four years.[69]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 46.4% 5,044 | 51.8% 5,624 | 1.8% 195' |

| 2020 | 43.2% 4,823 | 54.6% 6,088 | 2.2% 243 |

| 2016 | 41.8% 4,211 | 49.9% 5,031 | 8.3% 836 |

| 2012 | 32.2% 3,445 | 65.6% 7,017 | 2.2% 231 |

| 2008 | 32.6% 3,578 | 65.1% 7,142 | 2.3% 257 |

| 2004 | 33.7% 3,930 | 64.9% 7,560 | 1.4% 160 |

| 2000 | 33.8% 3,616 | 60.6% 6,489 | 5.6% 603 |

| 1996 | 26.1% 2,707 | 62.4% 6,473 | 11.5% 1,194 |

| 1992 | 24.5% 2,840 | 53.5% 6,213 | 22.0% 2,553 |

| 1988 | 34.6% 3,796 | 65.4% 7,182 | 0.0% 0 |

| 1984 | 35.1% 4,141 | 64.9% 7,648 | 0.0% 0 |

| 1980 | 34.2% 3,950 | 56.6% 6,546 | 9.2% 1,065 |

| 1976 | 36.2% 4,483 | 62.3% 7,720 | 1.5% 180 |

| 1972 | 44.9% 5,421 | 53.6% 6,473 | 1.5% 179 |

| 1968 | 35.7% 3,986 | 61.0% 6,798 | 3.3% 369 |

| 1964 | 30.4% 3,481 | 69.3% 7,928 | 0.3% 40 |

| 1960 | 50.6% 5,997 | 49.0% 5,811 | 0.4% 51 |

Education

[edit]Schools and colleges

[edit]

Austin Public Schools (Independent School District 492) serves more than 4,700 students in the Austin area. Pacelli Catholic Schools also provides a PreK-12 private education option. Austin High School, much of which was built in 1919, is well known for its distinctive architecture. A 1939 addition to the school includes Knowlton Auditorium, one of the largest high school auditoriums in Minnesota, seating 1,850. Post-secondary education is available at Riverland Community College, first established as Austin Junior College in 1940.

- Colleges

- High Schools

- Austin High School and Area Learning Center (Grades 9–12)

- Pacelli High School (Grades 9–12)

- Middle Schools (Junior High)

- Ellis Middle School [Grades 7–8]

- I.J Holton Intermediate School [Grades 5–6]

- Pacelli Middle School (Grades 6–8)

- Elementary Schools

- Pacelli Elementary School (Grades PreK-5)

- Banfield Elementary School (Grades 1–4)

- Neveln Elementary School (Grades 1–4)

- Southgate Elementary School (Grades 1–4)

- Sumner Elementary School (Grades 1–4)

- Woodson School (Kindergarten only)

- Oakland Education Center (special services coop with Albert Lea Public Schools; formerly St. Edward's School)

- Other schools

- Austin Area Catholic Schools

- Gerard Academy (ages 6–19)

- Oakland Baptist School

- Former school buildings

- Franklin School (original built in 1869, burned in 1890; new Franklin High School opened in 1891)

- Shaw Elementary School (opened, 1916; last year of operation, 1992; demolished, 1993)

- Webster School (Built in 1891, functions today as apartment homes)

- Lincoln Elementary School (Built in 1887; last year of operation, 1977); functions today as apartment homes)

- Queen of Angels School (now home to Community Learning Center and Early Childhood Family Education Center)

Public library

[edit]

The Austin Public Library opened in 1884 in the basement of the Mower County Courthouse. In 1904 the city opened a newly constructed Carnegie Library. This building was demolished in 1996 when a new library was opened at 323 4th Ave. NE. It holds over 80,000 volumes.[71]

Media

[edit]AM Radio

[edit]| AM radio stations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Call sign | Name | Format | |

| 970 | KQAQ | Real Presence Radio | Catholic | |

| 1450 | KATE | News/Talk | ||

| 1480 | KAUS | News/Talk | ||

FM Radio

[edit]| FM radio stations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Call sign | Name | Format | |

| 88.5 | KBDC | American Family Radio | Christian | |

| 90.1 | KNSE | MPR News | NPR | |

| 91.3 | KMSK | The Maverick | Public radio | |

| 96.1 | KQPR | Power 96 | Classic hits | |

| 99.9 | KAUS | US Country 99.9 | Country | |

| 102.7 | KYTC | Super Hits 102.7 | Classic Hits | |

| 103.3 | K233AD (KLSE Translator) |

Classical MPR | Classical | |

| 103.9 | K280EF (KCMP Translator) |

The Current | AAA | |

| 104.3 | KFNL-FM | Fun 104.3 | Classic hits | |

| 105.3 | KYBA | Y105 | AC | |

| 106.9 | KROC | CHR | ||

Television

[edit]Austin is part of Nielsen's Rochester-Mason City-Austin designated market area.[72] Austin has two television studios, KAAL channel 6 (ABC), and KSMQ-TV channel 15 (PBS). Other stations in the area include Rochester stations KTTC channel 10 (NBC) and KXLT-TV channel 47, plus KIMT Channel 3 (CBS) from Mason City, Iowa.

| Channel | Callsign | Affiliation | Branding | Subchannels | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Virtual) | Channel | Programming | |||

| 3.1 | KIMT | CBS | KIMT 3 | 3.2 3.3 3.4 |

MyNetworkTV ION Antenna TV |

| 6.1 | KAAL | ABC | KAAL 6 | 6.2 | This TV |

| 10.1 | KTTC | NBC | KTTC 10 | 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 |

CW+ Heroes & Icons Court TV True Crime Network |

| 15.1 | KSMQ | PBS | KSMQ | 15.2 15.3 15.4 |

MHz Worldview Create Minnesota Channel |

| 24.1 | KYIN | PBS | Iowa Public Television | 24.2 24.3 24.4 |

PBS Kids World Create |

| 47.1 | KXLT | FOX | FOX 47 | 47.2 47.3 47.4 47.5 |

MeTV Laff Escape Quest |

Newspapers

[edit]A daily newspaper, the Austin Daily Herald, serves the community and has a circulation of approximately 7,000. Austin Living is a bimonthly magazine featuring culture and lifestyle stories about Austin.[73] The Post-Bulletin, a daily newspaper from Rochester, is also widely read and distributed in Austin.

The documentary film American Dream was filmed in Austin during the 1985–86 Hormel strike. It was released in 1990 and won Best Documentary Feature at the 63rd Annual Academy Awards.[16]

Infrastructure

[edit]

Transportation

[edit]Airports

[edit]Austin is served by Austin Municipal Airport, a public-owned, public-use airport located on the east edge of the city.[74] The nearest commercial international airports are located in Rochester (RST), 35 miles (56 km) to the northeast, and the Twin Cities (MSP), 95 miles (153 km) to the north.

Bus and mass transit

[edit]Southern Minnesota Area Rural Transit provides bus transit within Austin and Mower County; daily routes, as well as on-demand pick-up and drop-off service is available.[75] Rochester City Lines provides daily bus transportation between Austin and Rochester. For travel within the city, there is also local taxi service available.

Major highways

[edit]Austin is located at the intersection of Interstate 90 and U.S. Route 218. Minnesota State Highway 105 runs from Austin south to Iowa.

Interstate 90 runs east-west through the north side of the city. The highway leads west to Albert Lea and northeast to the Rochester area.

Interstate 90 runs east-west through the north side of the city. The highway leads west to Albert Lea and northeast to the Rochester area. U.S. Route 218 passes through the east side of the city as 21st Street, joins I-90 through the north side of the city between exits 180 and 177, and leaves through the northwest part of the city on 14th Street.

U.S. Route 218 passes through the east side of the city as 21st Street, joins I-90 through the north side of the city between exits 180 and 177, and leaves through the northwest part of the city on 14th Street. Minnesota State Highway 105 passes through the southern and western sides of the city as 12th Street SW and West Oakland Avenue. It terminates at I-90 in the western end of the city.

Minnesota State Highway 105 passes through the southern and western sides of the city as 12th Street SW and West Oakland Avenue. It terminates at I-90 in the western end of the city.

Rail

[edit]

Austin was once a railroad town. It was a division point and the site of car shops for the Milwaukee Road, five lines of which met in Austin.[76] The community was also served by the Chicago Great Western's north–south mainline for trains between the Twin Cities and Omaha. All lines served passengers, and the Milwaukee Road Depot was a busy station ferrying travelers to and from Austin. Passenger rail service on the Milwaukee Road through Austin between Calmar, Iowa and St. Paul ended in 1953, and Pullman sleeper service on the Milwaukee between Austin and Chicago ended in 1960. An overnight train on the Chicago Great Western between the Twin Cities and Omaha called at Austin, with the southbound coming through late in the evening and the northbound train stopping early in the morning.[77] This train last ran on September 30, 1965, ending all passenger train service to Austin.[78] Freight service continues on the former Milwaukee Road mainline on that railroad's successor, the Iowa, Chicago and Eastern Railroad, a subsidiary of Canadian Pacific, but the Chicago Great Western was abandoned and torn up after the Chicago and North Western Railway acquired it in 1968.

Trails

[edit]Austin has an extensive network of paved recreational trails for biking and hiking. There are several miles of bike paths extending north to Todd Park and the Jay C. Hormel Nature Center. There is also a mountain biking trail, completed in 2015, that hosted a Minnesota High School Cycling League competition in its inaugural year.

Extensions to these existing non-motorized trails will connect Austin to the Blazing Star Trail (west toward Albert Lea and Myre-Big Island State Park) and the Shooting Star State Trail (east toward Rose Creek, Adams, and Leroy).[79]

Health care

[edit]

The Mayo Clinic Health system operates a full-service hospital and clinic in Austin, the Austin Medical Center. Both primary care and specialty care services are available locally. The campus also provides emergency and urgent care services, a complete pharmacy, and a recently expanded pediatrics department. Before joining the Mayo system, Austin Medical Center was St. Olaf Hospital.[80]

The Hormel Institute is a medical research branch of the University of Minnesota. Established in 1942, it has become one of the world's leading cancer research facilities. In 2016 the institute was expanded to twice its original size.[81] Tours of the institute are available but must be arranged through Discover Austin, the local convention and visitors bureau.

Notable people

[edit]- Marc Anderson, musician[82]

- Josh Braaten, actor[83]

- Philip Brunelle, conductor, primarily of choral music[84]

- Trace Bundy, instrumental acoustic guitar player[85]

- James W. Davidson, explorer, writer, diplomat, and philanthropist[86]

- Richard Eberhart, United States Poet Laureate[87]

- Shannon Frid-Rubin, violinist in Cloud Cult[88]

- Jason Gerhardt, actor[89]

- Jackie Graves, boxer[90]

- Matthew Griswold, songwriter and musician[91]

- Burdette Haldorson, basketball player and Olympian[92]

- Charles Robert Hansen, businessman, mayor of Austin, Minnesota, and Minnesota state senator[93]

- Vince Hanson, basketball player[94]

- Amanda Hocking, writer of paranormal romance young adult fiction[95]

- Geordie Hormel, musician, composer, founder/owner of The Village Recorder music studio in Los Angeles[96]

- George A. Hormel, founder of Hormel Foods[97]

- James C. Hormel, United States ambassador to Luxembourg, philanthropist, author[98]

- Jay Catherwood Hormel, president of Hormel Foods 1929–1954; son of founder George A. Hormel[99]

- Craig Hutchinson, film director and screenwriter[100]

- Hope Jahren, geochemist and geobiologist[101]

- Lee Janzen, professional golfer[102]

- Molly Kate Kestner, musician[103]

- Jennie Ellis Keysor, educator, writer[104]

- Larry Kramer, football player and coach[105]

- Tom Lehman, professional golfer[106]

- John Madden, former Oakland Raiders head coach, NFL commentator, and member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame[107]

- John Maus, musician[108][109]

- Helen E. McMillan, Minnesota state legislator[110]

- Patrick Moore, professional golfer[111]

- Wilbur Moore, professional football player[112]

- Barry Morrow, screenwriter and producer

- Bob Motzko, University of Minnesota head men's ice hockey coach[113]

- Tim O'Brien, novelist[114]

- Charlie Parr, musician[115]

- Pat Piper, politician[116]

- Jeanne Poppe, member of the Minnesota House of Representatives[117]

- Leo J. Reding, politician[118]

- William Pitt Root, poet[119]

- Paul Michael Stephani, serial killer[120]

- Frank Twedell, professional football player[121]

- Wally Ulrich, professional golfer[122]

- Sheldon B. Vance, U.S. ambassador to Zaire[123]

- Bree Walker, radio talk show host, actress, and disability-rights activist[124]

- Robert B. Westbrook, historian

- Sandy Wollschlager, chemist and Minnesota state representative[125]

- Michael Wuertz, former Major League Baseball pitcher with the Chicago Cubs and Oakland Athletics[126]

- Martin Zellar, musician and songwriter[127]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "2023 U.S. Gazetteer Files: Minnesota". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Austin, Minnesota

- ^ a b c "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ a b "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2022". United States Census Bureau. November 20, 2023. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f "City of Austin City Council, History". Archived from the original on February 20, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ Weber. "Adkins headlines at Spam Town USA". Rochester Post-Bulletin. Rochester, MN. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- ^ "About Us". The Hormel Institute. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- ^ Upham, Warren (1920). Minnesota Geographic Names: Their Origin and Historic Significance. Minnesota Historical Society. p. 359.

- ^ "Milestones in Our History". Hormel. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "History". Mayo Clinic Health System - Austin. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Horace Austin State Park beginnings at the Minnesota Legislature". Rochester Post-Bulletin. January 16, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "A return to Austin Acres". The Austin Daily Herald. Austin, MN. May 14, 2011. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ Hage, Dave; Klauda, Paul (1989). No retreat, no surrender: labor's war at Hormel. W. Morrow. ISBN 0688077455. OCLC 19325023.

- ^ Baier, Elizabeth (August 17, 2010). "25 years ago, Hormel strike changed Austin, industry". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ a b "American Dream (1990)". IMDB. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Risen, James (September 1, 1986). "Despite Settlement, It's Still Not Over : Hormel Strike May Divide Town for Years to Come". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, CA. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- ^ Ross, Jenna. "Austin moves forward after year". Minneapolis StarTribune. Retrieved March 24, 2016./

- ^ a b Schoonover, Jason (March 25, 2016). "Austin primed for a new future". Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ^ "Vision 2020 Austin". Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ Pan, Yuqing (October 5, 2015). "Top 10 Affordable Small Towns Where You'd Actually Want to Live". Realtor.com. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ a b "On the Move: A Minnesota City Creatively Battles Repetitive Flooding" (PDF). Federal Emergency Management Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Flood Mitigation Program". City of Austin. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Mewes, Trey (September 18, 2013). "Council moves ahead on flood project". Austin Daily Herald. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Austin, MN Tornado of June 17 2009. Crh.noaa.gov. Retrieved on July 21, 2013.

- ^ Peterson, Matt (June 17, 2011). "A Date to Remember". Austin Daily Herald. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ "Moist Continental Mid-latitude Climates - D Climate Type". The Encyclopedia of Earth. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". US Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Austin Waste WTP Facility, MN". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ^ "City of Austin, Minnesota - Major Employers & Workforce". April 2004. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008.

- ^ "Business Divisions". Hormel Foods. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- ^ Jackson, Jeffrey (March 17, 2016). "Unemployment inches up across the region". Austin Daily Herald. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Jackson, Jeffrey (March 31, 2016). "Jobless rate remains flat in region". Austin Daily Herald. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Austin High Rallies for Google Fiber". austindailyherald.com. March 24, 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ "GigAustin-Home". Gig Austin. Archived from the original on January 10, 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report" (PDF). p. 188. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ "Austin Symphony Orchestra". Austin Symphony Orchestra. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Austin Artist Series". Austin Artist Series. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Paramount Theater". Austin Area Commission for the Arts. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Northwestern Singers". Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Community Band brings sound of summer". Austin Daily Herald. June 6, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Austin Big Band". Archived from the original on April 5, 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "MacPhail Center for Music - Austin". Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Matchbox Children's Theatre". Matchbox Children's Theatre. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Summerset Theatre". Summerset Theatre. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Austin Area Commission for the Arts". Austin Area Commission for the Arts. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "A history of the First National Bank - Austin Daily Herald". austindailyherald.com. June 30, 2012. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ "The Elam House". The Elam House. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Blue Devils Athletics". Riverland Community College. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ "Southern Minnesota Bicycling Club". USA Cycling Clubs. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ Hulne, Rocky (March 23, 2015). "Stones and ice; Austin Curling Club slides into Riverside Arena". Austin Daily Herald. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ Hulne, Rocky (July 14, 2015). "Rolling to new levels". Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ "Southern Plains Football League". Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ Austin Daily Herald Newspaper Archives December 20, 1973 Page 8

- ^ amandalillie (September 22, 2010). "Riverside Arena makes its debut". Austin Daily Herald. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- ^ treymewes (July 17, 2015). "Riverside on schedule; Rink should be ready for hockey this fall". Austin Daily Herald. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "Packer Dome". Austin Public Schools. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ Underwood, Kim (December 6, 2015). "Public invited to check out the new dome". Austin Daily Herald. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ "About". Jay C. Hormel Nature Center. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ^ "Horace Park".

- ^ a b "Park Information". City of Austin - Department of Parks, Recreation, & Forestry. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Parks and Recreation". Austin Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ^ "Freedom Fest Schedule". Austin Daily Herald. July 4, 2015. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ "Republican Rep. Brad Finstad sworn in to finish Hagedorn's House term". August 12, 2022.

- ^ Stultz, Sarah (November 5, 2020). "Dornink wins District 27 Senate seat". Albert Lea Tribune. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ "2010: Year in Review". Austin Daily Herald. January 1, 2011. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ "City of Austin, Mn". Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Office of the Minnesota Secretary of State - Election Results".

- ^ "About the Library". Austin Public Library. Archived from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Local Television Market Universe Estimates" (PDF). Nielsen. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 12, 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Herald staff take home MNA awards". Austin Daily Herald. January 29, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ "KAUM - Austin Municipal Airport". AirNav.com. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "SMART". Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ Curtiss-Wedge, Franklyn, The History of Mower County, Minnesota. Chicago: H. C. Cooper & Co., 1911. pp. 99-102, 221, 236, 242.

- ^ Official Guide, April 1965, p. 688.

- ^ Fiore, David J. (2006). The Chicago Great Western Railway. Arcadia Publishing. p. 68. ISBN 0-7385-4048-X.

- ^ Lowthian, Russ (July 22, 2016). "Hayward waits for bridge to complete Blazing Star Trail". havefunbiking.com. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ "History". Mayo Clinic Health System. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- ^ Yang, Hannah (August 11, 2015). "Hormel Institute expansion includes new learning center". Rochester Post-Bulletin. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ^ Williams, Brandt. "Drummer follows musical path from Austin to Africa". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Josh Braaten - Actor". IMDB. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ Cummings, Robert. "Philip Brunelle - Artist Biography". Allmusic. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Trace Bundy". Pure Volume. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Lampard, Robert. "The Life and Times of Rotarian James Wheeler Davidson, FRGS". Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Richard Eberhart". Poets.org. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Shannon Frid, Cloud Cult. Npr.org. Retrieved on July 21, 2013.

- ^ "Jason Gerhardt excited about upcoming birth of son". People Magazine (online). Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Harringa, Adam (July 30, 2011). "Honoring Jackie Graves". Austin Daily Herald. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ <!—-not stated-->. "Matthew Griswold writes songs about war". Star Tribune. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Burdie Haldorson Bio, Stats, and Results". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com. Archived from the original on April 18, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ 'Charles (Baldy) Hansen dies, was senator, Austin mayor,' Minneapolis State Tribune, Terry Collins, May 24, 2000

- ^ "Cougar Great Vince Hanson Passes Away". Washington State Cougars. Archived from the original on April 4, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Vezner, Tad (April 5, 2011). "Young Austin, Minn., author finds fame — and fortune — publishing her work online". St. Paul Pioneer Press. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ "Geordie Hormel". IMDB. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Our History - About". Hormel Foods. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ Rapp, Linda (March 1, 2004). "Hormel, James C. (b. 1931)". glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture. Archived from the original on April 14, 2009. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- ^ Bonorden, Lee (October 5, 2002). "Life behind the mansion doors". Austin Daily Herald. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Craig Hutchinson". IMDB. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "A lasting impact; Austin native making waves in science". Austin Daily Herald. May 13, 2016.

- ^ "Lee Janzen". IMDB. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Gabler, Jay (August 22, 2014). "Molly Kate Kestner talks about staying grounded". The Current. Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Willard, Frances Elizabeth; Livermore, Mary Ashton Rice (1893). "KEYSOR, Mrs. Jennie Ellis". A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life. Charles Wells Moulton. p. 435.

- ^ "Larry Kramer". University of Nebraska. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Tom Lehman". PGA Tour. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "John Madden". Pro Football Hall of Fame. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- ^ John Maus: The Sound of the North. Mpls.Tv (June 23, 2011). Retrieved on July 21, 2013.

- ^ Ferguson, Wm. (October 28, 2011). "The Orchestral Maneuvers of John Maus". The New York Times. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ 'Former Legislator McMillan, 74, Dies,' Minnesota Star-Tribune, January 30, 1984

- ^ "Patrick Moore". PGA Tour. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Wilbur Moore". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Bob Motzko: Head Men's Hockey Coach". St. Cloud State University. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Minnesota Author Biographies Project : mnhs.org". People.mnhs.org. Archived from the original on December 31, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ Mewes, Trey (May 17, 2012). "Charlie Parr plans homecoming". Austin Daily Herald. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Patricia Kathryn Piper". Patricia Kathryn Piper Obituary.

- ^ "Rep. Jeanne Poppe". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- ^ "Reding, Leo John - Legislator Record - Minnesota Legislators Past & Present". www.leg.state.mn.us. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ "William Pitt Root". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Paul Michael Stephani 'The Weepy-Voice Killer': 5 Fast Facts". April 9, 2020.

- ^ "Frank Twedell". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved December 24, 2010.

- ^ Gregg Wong (May 21, 1995). "Ulrich Was No Fair-Weather Golfer". St. Paul Pioneer Press. St. Paul, Minnesota. p. 14C.

- ^ "Sheldon B. Vance". www.nndb.com. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ "Bree Walker Interview". Ability Magazine (online). Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ Minnesota Legislators: Past & Present-Sandy Wollschlager

- ^ "Michael Wuertz Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Galbally, Erin (February 10, 2005). "Martin Zellar gets political". Retrieved March 23, 2016.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Austin Convention & Visitors Bureau

- Austin Area Chamber of Commerce

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

Further reading

[edit]- Mower County History Committee (1984). Mill on the Willow: A History of Mower County, Minnesota. Lake Mills, Iowa: Graphic Pub. Co. LCCN 84-062356. OCLC 13009348.

- The 1985–1986 Hormel Meat Packers Strike in Austin, Minnesota by Frank Halstead. Pathfinder Press, 1985. ISBN 0-87348-489-4.

- City of Austin: 150th Anniversary Pictorial. Turner Publishing Company, 2005. ISBN 978-1-59652-189-6.

- Remembering Austin's yester years by Richard Hall. Mower County Historical Society, 1995.

- Once around the Mill Pond and Cedar River by Richard Hall. Mower County Historical Society, 2009.