Portsmouth: Difference between revisions

| Line 348: | Line 348: | ||

{| class="wikitable" |

{| class="wikitable" |

||

|+Average sea temperature<ref>{{cite web|title=Portsmouth Sea Temperature|url=http://www.seatemperature.org/europe/united-kingdom/portsmouth-january.htm Portsmouth average sea temperatur|publisher=World Sea Temperature|accessdate=26 July 2016}}</ref> |

|||

|+Average sea temperature |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! Jan |

! Jan |

||

Revision as of 13:49, 26 July 2016

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Jaguar (talk | contribs) 8 years ago. (Update timer) |

Portsmouth

City of Portsmouth | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: Portsmouth viewed from Portsdown Hill, HMS Victory, Portsmouth Guildhall, Portsmouth Cathedral, the Spinnaker Tower alongside Portsmouth Harbour at night, Gunwharf Quays, Portchester Castle and an aerial view of Old Portsmouth | |

| Nickname: Pompey | |

| Motto: Heaven's Light Our Guide | |

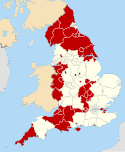

Location within Hampshire | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | England |

| Region | South East England |

| Ceremonial county | Hampshire |

| Admin HQ | Portsmouth City Centre |

| Government | |

| • Type | Unitary authority, City |

| • Governing body | Portsmouth City Council |

| • Leadership | Leader & Cabinet |

| Area | |

| • City & unitary authority area | 15.54 sq mi (40.25 km2) |

| Population (2022) | |

| • City & unitary authority area | 208,420 (Ranked 76th)[2][3] |

| • Urban | 855,679 |

| • Metro | 1,547,000[1] |

| • Ethnicity (United Kingdom Census 2006 Estimate)[4] | 91.4% White 3.6% S.Asian 1.2% Black 1.3% Mixed 2.5% Chinese and other |

| Time zone | UTC0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Postal code | PO1 – PO8 Inclusive |

| Area code | 023 |

| Website | Portsmouth City Council |

Portsmouth (/ˈpɔːrtsməθ/ ) is a large port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire on the south coast of England. Located mainly on Portsea Island, it is the United Kingdom's only island city. With a population of 205,400, it is the only city in the British Isles with a greater population density than London. The city is situated 64 miles (103 km) south-west of London and 19 miles (31 km) south-east of Southampton. The city of Portsmouth and Portsmouth Football Club are both nicknamed "Pompey". The naval base at HMNB Portsmouth is the largest dockyard for the Royal Navy and is home to two-thirds of the entire surface fleet.

The city has a long history which can be traced back to Roman times. As a significant naval port for centuries, Portsmouth has the world's oldest dry dock and is home to some famous ships, including HMS Warrior, the Tudor carrack Mary Rose and Lord Nelson's flagship, HMS Victory (the world's oldest naval ship still in commission). The city was England's first line of defence during the French invasion in 1545, and fortifications were built in 1859 in anticipation of another invasion. By the 19th century, Portsmouth was one of the most fortified cities in the world, and assisted in the expansion of the British Empire. During the Second World War, the city served as a pivotal embarkation point for the D-Day landings and was bombed extensively in the Portsmouth Blitz, which resulted in the deaths of 930 people. More recently, Portsmouth housed the majority of the attacking forces in the Falklands War, and Her Majesty's Yacht Britannia left the city to oversee the transfer of Hong Kong.

The waterfront area and Portsmouth Harbour are dominated by the Spinnaker Tower, one of the United Kingdom's tallest structures at 560 feet (170 m). The former HMS Vernon naval shore establishment has now been redeveloped as an area of retail outlets, restaurants, clubs and pubs known as Gunwharf Quays. As well as the naval base, Portsmouth International Port is a commercial cruise ship and ferry port which serves international destinations for freight and passenger traffic. Portsmouth is among the few British cities with two cathedrals: the Anglican cathedral of St Thomas and the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St John the Evangelist.

Portsmouth forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Southampton and the towns of Havant, Waterlooville, Eastleigh, Fareham and Gosport. With about 860,000 residents, it is the 6th largest urban area in England and the largest in South East England, forming the centre of one of the United Kingdom's most populous metropolitan areas with a population in excess of one million.[1] The local authority, Portsmouth City Council, was given unitary authority status in 1997.

History

Prehistory

There have been settlements in the area since before Roman times,[5] mostly being offshoots of Portchester,[6] which was a Roman base (Portus Adurni) and possibly the home port of the Classis Britannica.[7] Some sources maintain that the town was founded in 1180 by the Anglo-Norman merchant Jean de Gisors.[8] Most early records of Portsmouth are thought to have been destroyed by Norman invaders following the Norman conquest of England.[9] The earliest detailed references to Portsmouth can be found in the Southwick Cartularies.[10] However, there are records from the late 9th century of "Portesmūða", meaning "mouth of the Portus harbour".[11]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for the year 501 claims that "Portesmuða" was founded by a Saxon warrior called Port.[12] Although Winston Churchill in his A History of the English-Speaking Peoples also states that Portsmouth was founded in 501 by Port, the pirate,[13] most historians do not accept that origin of the name.[14] The Chronicle states that:

- Her cwom Port on Bretene 7 his .ii. suna Bieda 7 Mægla mid .ii. scipum on þære stowe þe is gecueden Portesmuþa 7 ofslogon anne giongne brettiscmonnan, swiþe æþelne monnan.

- where "7" denotes the Tironian et, an abbreviation for "and".

- ("Here Port and his 2 sons Bieda and Mægla came to Britain with 2 ships to the place which is called Portsmouth and slew a young British man, a very noble man.")

Medieval

There was no mention of Portsmouth in the Domesday Survey of 1086, although nearby settlements that were later to form part of Portsmouth were included.[15] While Portsea had a small church prior to 1166, Portsmouth's first chapel was built in 1185 and was dedicated to Thomas Becket. It was erected and run by Augustinian monks of Southwick Priory until the English Reformation in the 16th century.[16] The modern Portsmouth Anglican Cathedral is built on the original site of the chapel.[17]

In 1194 King Richard I returned from captivity in Austria, and soon summoned a fleet and an army to Portsmouth, which Richard had taken over from Jean de Gisors. On 2 May 1194, Richard I gave Portsmouth its first Royal charter. This granted permission for the borough to hold an annual fifteen-day "Free Market Fair", weekly markets, and a local court to deal with minor matters.[15] The borough was also exempted from paying the annual tax[which?] of £16, so that the money could be used for local matters.[15][18] The crescent and eight-pointed star found on the 13th century common seal of Portsmouth was derived from the arms of William de Longchamp, Lord Chancellor to Richard I at the time of the charter.[15] It was, however, Richard himself who granted the town the arms of Isaac Komnenos of Cyprus whom he had defeated. After Isaac had held Richard's fiancée and sister captive, the king responded by conquering Cyprus during the Third Crusade. His awarding of the arms could possibly reflect a significant involvement of Portsmouth soldiers, sailors or vessels in that operation.[19] The crescent and star, in gold on a blue shield, were subsequently recorded by the College of Arms as the coat of arms of the borough.[20]

In 1200 King John reaffirmed the rights and privileges awarded by Richard I. King John's desire to invade Normandy resulted in the establishment of Portsmouth as a permanent naval base – construction of the first docks by William of Wrotham begun in 1212.[15] During the 13th century Portsmouth was commonly used by Henry III and Edward I as a base for attacks against France. By the 14th century commercial interests had grown considerably: common imports included wool, grain, wheat, woad, wax and iron; however the port's largest trade was in wine from Bayonne and Bordeaux.[21] In 1338 a French fleet led by Nicholas Béhuchet raided Portsmouth, destroying much of the town,[22] with only the local church and hospital surviving.[23] After the raid, Edward III gave the town exemption from national taxes to aid reconstruction.[24] Ten years later, in 1348, the town was struck by the Black Death, causing the death of Portsmouth's rector, Walter de Corf.[25] As the regrowth of Portsmouth represented a threat to the French, they again sacked the town in 1369, 1377 and 1380.[22][26]

Henry V built the first permanent fortifications of Portsmouth. In 1418 he ordered a wooden Round Tower to be built at the mouth of the harbour; this was completed in 1426. Henry VII rebuilt the fortifications with stone, raised a square tower, and assisted Robert Brygandine and Sir Reginald Bray in the construction of the world's first dry dock.[27][28] Although King Alfred may have used Portsmouth to build ships as early as the 9th century, the first warship recorded as constructed in the town was the Sweepstake, built in the dry dock in 1497.[29] In 1544, with money from the Dissolution of the Monasteries and in view of the growing expectation of an increased conflict with the French, Henry VIII built Southsea Castle and decreed that Portsmouth should be the home of the Royal Navy he had founded.[30] In 1545, from Southsea Castle, he saw his flagship Mary Rose sink with the loss of about 500 lives, while going into action against the French fleet in the Battle of the Solent.[31] Over the years, Portsmouth's fortifications were rebuilt and improved by successive monarchs. In 1563, Portsmouth suffered from an outbreak of a plague, with about 300 deaths out of the town's population of 2000.[26]

Stuart to Georgian

In 1628, the unpopular military adviser of Charles I —and possibly lover of James I[32]—George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, was stabbed to death in an Old Portsmouth pub by war veteran John Felton.[15] The murder took place in the "Greyhound" pub (popularly known as "The Spotted Dog") on the main High Street. Now a private building called Buckingham House, it bears a commemorative plaque marking the event.[33] For his crime, Fenton was hanged and his body was left in chains to the east of the town, as a warning to others.[26]

Most of Portsmouth's residents, including the mayor, supported the parliamentarians during the English Civil War. However, the military governor of the town, Colonel Goring, who commanded the soldiers in Portsmouth, supported the royalists.[26] During the war, the town became a major base for the parliamentarian navy, and so the town was blockaded from the sea. Parliamentarian troops were sent to besiege Portsmouth by land; the guns of Southsea Castle were fired at the town of Portsmouth by parliamentarian troops. Across the harbour, the town of Gosport joined the parliamentary side and set up guns to join in the assault on the town, damaging St Thomas's Church in the process.[26][34] On 5 September 1642, the remaining royalist garrison at the Square Tower were forced to surrender after Goring threatened to blow up the tower with gunpowder. In return, he and his garrison were allowed safe passage out of Portsmouth.[34][35]

Under the Commonwealth of England, Robert Blake, the father of the Royal Navy, used Portsmouth as his main base during both the First Anglo-Dutch War and the Anglo Spanish War. He died within sight of the town after his final cruise off Cádiz.[35] After the end of the Civil War in in 1646, Portsmouth began to prosper as a town. In 1650, the first ship to be built in the town for over 100 years, named Portsmouth, was launched in the dockyard. Between 1650 and 1660 twelve ships were built in the town and the population had increased to around 3000. Shortly after the restoration of Monarchy, Charles II married Catherine of Braganza in Portsmouth.[26] During the latter half of the 17th century Portsmouth continued to grow; a new wharf was constructed in 1663 for military use, and in 1665 a mast pond was dug out. Between 1667 and 1685 the fortifications around the town were rebuilt. New walls were constructed with bastions and two moats were dug outside the walls, making Portsmouth one of the most heavily fortified towns in Europe.[26]

In 1759, General James Wolfe sailed from Portsmouth to Canada on an ill-fated expedition to capture Quebec, which culminated in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. Paving of the town's streets was completed in 1773 at the cost of £8,886.[15] Two years later, on 30 May 1775, Captain James Cook arrived in Portsmouth on board the HMS Endeavour after circumnavigating the world.[15][36] On 13 May 1787, eleven ships sailed from Portsmouth to establish the first European colony in Australia, marking the beginning of prisoner transports to that continent. It is known today in Australia as the First Fleet.[37][38] In the same year, Captain William Bligh of the HMS Bounty set sail from Portsmouth.[15]

The city's nickname Pompey is thought to have derived from the log entry "Pom. P." (meaning Portsmouth Point) made as ships entered Portsmouth Harbour. Navigational charts use this abbreviation.[39] Another theory is that it is named after the harbour's guardship, Le Pompee, a 74-gun French battleship captured in 1793.[40]

Industrial Revolution to Victorian

Portsmouth has a long history of supporting the Royal Navy logistically, leading to its importance in the development of the Industrial Revolution. Marc Isambard Brunel, the father of famed engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, established in 1802 the world's first mass production line at the Portsmouth Block Mills, producing pulley blocks for rigging on the Royal Navy's ships.[41] The first set of machines to make medium blocks were installed in January 1803, with the second set of machines in May 1803 and the final set for large blocks in March 1805. By September 1807 the Portsmouth Block Mills were able to fulfil all the needs of the Royal Navy – in 1808 it produced 130,000 blocks.[42] By the turn of the 19th century, Portsmouth had the largest industrial site in the world with a workforce of 8000 and an annual budget of £570,000.[43]

In 1805, Admiral Horatio Nelson left Portsmouth for the last time to command the fleet that defeated the larger Franco-Spanish fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar.[15] The Royal Navy's reliance on Portsmouth led to the town becoming the most fortified in the world,[44] with a network of Palmerston Forts encircling the town.[26] In the same year the first steam carriage, built for 12 people, was commissioned in Portsmouth, and in the following year Isambard Kingdom Brunel was born in the town.[15] From 1808 the Royal Navy's West Africa Squadron, which was tasked to stop the slave trade, operated out of Portsmouth.[45] Charles Dickens was born in Portsmouth in 1812.[15]

In 1818 John Pounds began teaching the working class children of Portsmouth in what became the country's first ragged school.[46] The schools and the resulting movement aimed to provide education to all children regardless of their ability to pay.[47] In 1811 Portsmouth obtained its first piped water supply; however it was only available to the upper and middle classes. By 1819, five hundred workers who resided in the town emigrated to the United States. In 1820 the Portsea Improvement Commissioners installed gas street lighting throughout the town,[15] with Old Portsmouth receiving them three years later.[26] Portsmouth was hit by an earthquake tremor on 3 August 1835; it was described as a "shock and rumbling sound" at nearby Emsworth.[48]

During the 19th century, Portsmouth continued to grow and expanded across Portsea Island. By the 1860s the village of Buckland had been merged with Portsmouth, and by the next decade Fratton and Stramshaw had been incorporated into the spreading town. Between 1865 and 1870 the council built sewers, after more than 800 people died in a cholera epidemic. A bylaw stated that any house within 100 feet (30 m) of a sewer had to be connected to it.[15] By 1871 the population of Portsmouth had risen to 100,000,[26] although the national census at that time gave the population as 113,569.[15] In 1869, roughly 1000 dockyard workers emigrated to Canada. A horse tramway service opened from Old Portsmouth to North End a few years later. A working class suburb was constructed in the 1870s; around 1820 houses were being built along large patches of land owned by a Mr Somers. The suburb was eventually named Somerstown, in honour of the landowner.[15] Despite public health improvements by the council, 514 people died in a smallpox epidemic in 1872.[15] On 21 December 1872 a major scientific expedition, the Challenger expedition, was launched from Portsmouth.[49][50]

First to Second World War

As a vital port for the Royal Navy, Portsmouth played large roles in both world wars. In 1916, the town experienced its first aerial bombardment when a Zeppelin airship bombed it.[51] During the First World War, the number of people who worked at the dockyard had risen to 23,000, although it had fallen to 9000 when the war ended.[26] Portsmouth was granted city status in 1926, following a long campaign by the borough council. The application was made on the grounds that Portsmouth was the "first naval port of the kingdom".[52] In 1929 the city council added the motto "Heaven's Light Our Guide" to the medieval coat of arms. Except from referring to the celestial objects in the arms, the motto was that of the Star of India; this recalled that troopships bound for British India left from the port.[20][53] The crest and supporters are based on those of the royal arms, but altered to show the city's maritime connections: the lions and unicorn have been given fish tails, and a naval crown placed around the unicorn.[53] Around the unicorn is wrapped a representation of "The Mighty Chain of Iron", a Tudor defensive boom across Portsmouth Harbour.[54]

During the Second World War, the city was bombed extensively in the Portsmouth Blitz, destroying most of its three main shopping areas.[15] Portsmouth's status as a major port was the key factor in the Luftwaffe's decision to bomb it so heavily. The Guildhall was hit by an incendiary bomb, which burnt out the interior, although the civic plate was retrieved unharmed from a vault under its stairs.[55] Many of the city's homes were damaged and whole areas in Landport and Old Portsmouth destroyed.[56] The air raids caused a total of 930 deaths and almost 3000 wounded,[55] especially in the dockyard and military establishments.[57] A total of 67 air raids occurred in the city between July 1940 and May 1944, comprising the destruction of 6625 houses and a further of 6549 severely damaged.[26]

Portsmouth Harbour and the surrounding city served as a vital military embarkation point for the D-Day landings on 6 June 1944. Southwick House, just to the north of Portsmouth, had been chosen as the headquarters for the Supreme Allied Commander, US General Dwight D. Eisenhower.[58][15] On 15 July 1944 an experimental V-1 flying bomb hit Newcomen Road, killing 15 people, By the end of the Portsmouth Blitz, around 10% of the city had been destroyed.[26]

Post-war

After the war, much of the city's housing stock was damaged and more was cleared in an attempt to improve the quality of dwellings. Before permanent accommodations could be built, Portsmouth City Council built prefabs for those who had lost their homes. Between 1945 and 1947, more than 700 prefab houses were constructed – some were erected over bomb sites.[26] The first permanent houses were built away from the city centre to new developments such as Paulsgrove and Leigh Park,[59] with construction of council estates in Paulsgrove being completed in 1953. In Leigh Park, the first housing estates were ready for use in 1949, however building in the area continued until 1974.[26] While most of the city has since been rebuilt, developers still occasionally find unexploded bombs in the area, such as on the site of the destroyed Hippodrome theatre in 1984.[60] Despite improvements made by the city council to build new accommodations, a survey made in 1955 concluded that 7000 houses in Portsmouth were unfit for human habitation. As a result, a whole section of central Portsmouth including Landport, Somerstown and Buckland was entirely rebuilt during the 1960s and early 1970s.[26]

After the decline of the British Empire during the latter half of the 20th century, the city council made attempts to diversify industry in Portsmouth. An industrial estate was built in Fratton in 1948, and other industrial estates were built at Paulsgrove and Farlington in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1951, 46% of the manufacturing jobs in the city were in shipbuilding, however by 1966 this had fallen down to 14%, drastically reducing the workforce of the dockyard.[26] Traditional industries such as brewing and corset making vanished during this time, although electrical engineering became a major employer. Despite the cutbacks made to traditional sectors, Portsmouth still remained an attractive place for industry. In 1968, Zurich Insurance Group moved their headquarters to Portsmouth, and in 1979 IBM moved their headquarters to the city.[26] Tourism became a major industry for Portsmouth in recent years; in 1982 the Tudor carrick Mary Rose was raised from the seabed in 1982 and has since become a museum open to the public.[61] The D-Day museum opened in 1984 and the HMS Warrior, Britain's first ironclad warship, was moved to the city in 1987.[26][62][63]

On 5 April 1982 the entirety of British Task Force left Portsmouth to engage the Argentine fleet in the Falklands War, taking over two weeks to reach the Falkland Islands, which are situated over 8,000 miles (13,000 km) away.[64] The flagship of the task force, HMS Hermes, returned to Portsmouth carrying the survivors of HMS Sheffield on 21 July 1982, and was decommissioned shortly after.[65] In January 1997, Her Majesty's Yacht Britannia embarked from Portsmouth on her final voyage to oversee the transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong. She was later decommissioned on 11 December that year at Portsmouth Naval Base in the presence of the Queen, the Duke of Edinburgh and twelve senior members of the Royal Family.[66]

In 2001, redevelopment of the HMS Vernon naval shore establishment began as a complex of retail outlets, clubs, pubs, and a large shopping centre known as Gunwharf Quays.[26] In 2003, construction of the 552 feet (168 m) tall Spinnaker Tower began at Gunwharf Quays with sponsorship from the National Lottery.[67] In late 2004, the Tricorn Centre, dubbed "the ugliest building in the UK", was demolished after years of debate over the expense of demolition, and controversy as to whether it was worth preserving as an example of 1960s brutalist architecture.[68][69] In 2005 the city celebrated the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar, with Queen Elizabeth II being present at a formal fleet review and a staged mock battle.[26] The naval base at HMNB Portsmouth remains the largest dockyard for the Royal Navy and is home to two-thirds of the entire surface fleet.[70]

Geography

Most of Portsmouth is situated on Portsea Island, being the United Kingdom's only island city.[71] Because it is an island, it cannot easily expand, making it the most densely populated city in the British Isles.[3] Portsea Island is separated from the mainland of Great Britain to the north by a narrow creek, known as Portsbridge Creek.[72] The creek is bridged in only six places: there are three road bridges (the M275 motorway, A3 road and the A2030 road), a railway bridge and two foot bridges.[73] Maps sometimes show Portsea Island as a peninsula, which is incorrect.[72] The sheltered Portsmouth Harbour lies to the west of Portsea Island and the large tidal bay of Langstone Harbour is to the east.[72] The Hilsea Lines are a series of defunct fortifications on the north coast of the island which border the creek and the mainland.[74]

To the south are the waters of the Solent with the approaches to Portsmouth Harbour and the Isle of Wight beyond. The southern waterfront of the city is dominated by a series of fortifications including the Round Tower, the Square Tower and Southsea Castle.[75] Old Portsmouth, situated in the south-west of the city, is the oldest part of the city and includes Portsmouth Point and the historic waterfront area known as Spice Island.[76] The main southern part of the city comprises the area known as Southsea and to the east,[77] the area known as Eastney.[78] The west of the city is mainly council estates such as Buckland, Landport and Portsea. These were built to replace Victorian terraces destroyed by bombing in the Second World War.[26] After the war the large estate of Leigh Park was built to solve the chronic housing shortage during the post-war reconstruction. Since the early 2000s the estate has been entirely under the jurisdiction of Havant Borough Council, but Portsmouth City Council remains the landlord of these properties, making it the biggest landowner in Havant Borough.[59]

Portsdown Hill dominates the skyline in the north of the city, giving a panoramic view over the island. The hill is the location of several large Palmerston Forts which consist of smaller forts: Fort Fareham, Fort Wallington, Fort Nelson, Fort Southwick, Fort Widley, and Fort Purbrook. These were built in the 19th century and were designed to protect Portsmouth from an inland attack.[75] Northern areas of the city include Stamshaw, Hilsea and Copnor, while north of the creek Cosham, Drayton, Farlington and Port Solent also form part of the city.[79]

The has two main shopping centres, the Cascades Shopping Centre, which lies in the city centre, and Gunwharf Quays, a redevelopment of the HMS Vernon naval shore establishment which lies on the south waterfront.[80] The city's central station, Portsmouth and Southsea railway station,[81] is located to the south of the city centre, close to the Guildhall and the Civic Offices.[55] Just to the south of the Guildhall is Guildhall Walk, a nightlife area with many pubs and clubs.[82] Edinburgh Road contains the city's Roman Catholic cathedral and Victoria Park, a 15 acres (6.1 ha) park named after Queen Victoria, which opened in 1878.[83] In the centre of the island are the districts of North End and Fratton.[84][85]

Geology

The city is located in the Hampshire Basin.[86] Portsdown Hill is formed by a large band of chalk. The rest of Portsea Island is composed of layers of London Clay and sand (part of the Bagshot Formation), formed principally during the late and early Eocene Epoch.[87] It is low-lying: the majority of its surface area is only about 3 metres (9.8 ft) above sea level.[88] The highest natural elevation on Portsea Island is Kingston Cross at 21 feet (6.4 m).[89] As a result, rising sea levels, perhaps due to global warming, could cause serious damage to the city.[90]

Climate

Portsmouth has a temperate oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb), similar to much of southern Britain. During winter frosts are light and short-lived and snow quite rare, with temperatures rarely dropping below freezing, as the city is surrounded by water and densely populated, and Portsdown Hill protects the city from cold northerly winds. The average maximum temperature in January is 10 °C (50 °F) with the average minimum being 5 °C (41 °F). The lowest temperature recorded is −8 °C (18 °F).[91] In summer a temperature of 30 °C (86 °F) can occasionally be attained, particularly in more sheltered spots, but temperatures rarely reach much more than that because of the cooling influence of the sea. The average maximum temperature in July is 22 °C (72 °F), with the average minimum being 15 °C (59 °F). The highest temperature recorded is 35 °C (95 °F).[91] As it is located on the south coast, Portsmouth receives more sunshine per annum than most of the UK and much of western Europe. The city gets around 645 millimetres of rain a year, with a minimum of 1 mm (0 in) of rain reported on 103 days a year.[92]

| Climate data for Solent MRSC, Portsmouth, elevation: 9m (1981-2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.2 (46.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

13.2 (55.8) |

16.7 (62.1) |

19.2 (66.6) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

19.0 (66.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

8.7 (47.7) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.4 (38.1) |

2.8 (37.0) |

4.5 (40.1) |

6.1 (43.0) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.2 (57.6) |

14.3 (57.7) |

12.2 (54.0) |

9.6 (49.3) |

6.2 (43.2) |

3.8 (38.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 68.8 (2.71) |

49.3 (1.94) |

51.6 (2.03) |

42.4 (1.67) |

43.4 (1.71) |

42.0 (1.65) |

44.5 (1.75) |

50.0 (1.97) |

53.7 (2.11) |

86.2 (3.39) |

83.2 (3.28) |

83.9 (3.30) |

699.1 (27.52) |

| Average precipitation days | 11.6 | 9.6 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 7.1 | 6.9 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 8.7 | 10.5 | 11.2 | 12.2 | 108.6 |

| Source: Met Office[93] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Southsea, Portsmouth 1976-2005 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 9.6 (49.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.8 (62.2) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

15.8 (60.4) |

12.0 (53.6) |

10.0 (50.0) |

14.9 (58.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.1 (41.2) |

4.3 (39.7) |

5.4 (41.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.3 (54.1) |

15.0 (59.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.5 (45.5) |

5.9 (42.6) |

9.2 (48.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 65 (2.6) |

50 (2.0) |

52 (2.0) |

42 (1.7) |

28 (1.1) |

40 (1.6) |

32 (1.3) |

43 (1.7) |

62 (2.4) |

81 (3.2) |

72 (2.8) |

80 (3.1) |

647 (25.5) |

| Average rainy days | 11.2 | 9.5 | 8.3 | 7.6 | 6.5 | 7.4 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 8.5 | 10.9 | 10.3 | 11.2 | 103.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 67.9 | 89.6 | 132.7 | 200.5 | 240.8 | 247.6 | 261.8 | 240.7 | 172.9 | 121.8 | 82.3 | 60.5 | 1,919.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 26 | 31 | 36 | 49 | 51 | 51 | 54 | 54 | 46 | 38 | 31 | 25 | 41 |

| Source 1: [92] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: BADC[94] | |||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9.5 °C (49.1 °F) | 9.0 °C (48.2 °F) | 8.6 °C (47.5 °F) | 9.8 °C (49.6 °F) | 11.4 °C (52.5 °F) | 13.5 °C (56.3 °F) | 15.3 °C (59.5 °F) | 16.8 °C (62.2 °F) | 17.3 °C (63.1 °F) | 16.2 °C (61.2 °F) | 14.4 °C (57.9 °F) | 11.8 °C (53.2 °F) | 12.8 °C (55.0 °F) |

Demography

Portsmouth is the most densely populated city in the United Kingdom and is the only city whose population density exceeds that of London.[2][3] As of the 2011 census, the city had 205,400 residents.[2][96] This equates to 5,100 people living in every square kilometre, which is eleven times more than the regional average of 440 people per square kilometre and more than London, which has 4,900 people per square kilometre. The city used to be even more densely populated, with the 1951 census showing a population of 233,545.[2] The population of the city declined in the late 20th century, as people moved out of the city into the surrounding South Hampshire commuter region.[96] However, since the 1990s the population of the city is now increasing once again.[97]

The city is predominantly white in terms of ethnicity, with 90.9% of the population belonging to this ethnic group.[98] Portsmouth's long association with the Royal Navy meant that it represents one of the most diverse cities in terms of the peoples of the British Isles, with many demobilised sailors staying in the city, in particular, Scots, English from the North East, and Northern Irish.[99] Similarly, some of the largest and most established non-white communities have their roots with the Royal Navy, most notably the large Chinese community, principally from British Hong Kong.[100][101] Portsmouth's long industrial history in support of the Royal Navy has seen many people from across the British Isles move to Portsmouth to work in the factories and docks, the largest of these groups being Irish Catholics (Portsmouth is one of 34 British towns and cities with a Catholic cathedral).[102][103] According to 2007 estimates, the ethnic breakdown of Portsmouth's population is as follows: 86.4% White British, 3.8% Other White, 1.7% Chinese, 1.6% Indian, 1.3% Mixed-Race, 1.2% Bangladeshi, 1.0% Other ethnic group, 0.9% Black African, 0.7% White Irish, 0.6% Other South Asian, 0.4% Pakistani, 0.3% Black Caribbean and 0.1% Other Black.[3][104]

| Population growth in Portsmouth since 1310[105] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1310 | 1560 | 1801 | 1851 | 1901 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 | |||||||||||

| Population | 740 (est) | 1000 (est) | 32,160 | 72,096 | 188,133 | 233,545 | 215,077 | 197,431 | 175,382 | 177,142 | 186,700 | 205,400 | |||||||||||

Government and politics

The city is administered by Portsmouth City Council, a unitary authority which is responsible for local affairs. Portsmouth was granted its first charter in 1194.[106] In 1904 the boundaries were extended to include the whole of Portsea Island; the boundaries were further extended in 1920 and 1932, taking in areas of the mainland.[26] Between 1 April 1974 and 1 April 1997 it formed the second tier of local government below Hampshire County Council. Portsmouth remains part of the ceremonial county of Hampshire for purposes such as lieutenancy and shrievalty. The city is divided into two parliamentary constituencies, Portsmouth South and Portsmouth North, represented in the House of Commons by, respectively, Flick Drummond and Penny Mordaunt, both Conservative Members of Parliament.[107] The Portsmouth constituencies are considered national bellwethers particularly Portsmouth North which has an electorate referred to as working class tory. Constituencies in industrial cities tend to vote labour, however the city's strong connection to the military has often seen the Conservative party take the seat. The Conservatives have tended to hold both when forming a majority government, when Labour is power it tends to take Portsmouth North.[108] Former Labour Prime Minister James Callaghan grew up in the Portsmouth North constituency.

The city council is made up of 42 Councillors. After the May 2014 local elections, the Conservatives formed a minority administration with just 12 Councillors. The largest party within the council is the Liberal Democrats with 19 Councillors (including the Lord Mayor). The other parties represented in council are the UK Independence Party and Labour, with five and four Councillors respectively. There are also two independent Councillors, Cllr. Eleanor Scott (elected as a Liberal Democrat) and Cllr. Paul Godier (elected as UKIP).[109] Councillors are returned from 14 wards, each ward having three councillors. Councillors have a four-year term, with one seat being contested in each ward in three years out of four. The leader of the council is the Conservative Cllr. Donna Jones.[110] The Lord Mayor of Portsmouth is a separate ceremonial position, elected and usually held for a one-year period of office.[111]

The council is based in the Civic Offices, which houses all council rooms as well as tax offices, resident services and municipal functions. They are situated in Guildhall Square, along with Portsmouth Guildhall and Portsmouth Central Library. The Guildhall is a symbol of Portsmouth, serving principally as a cultural venue. It was designed in the neo-classical style and constructed in 1890.[112]

Economy

A chart of trend in regional gross value added in Portsmouth, at current basic prices, has been published by the Office for National Statistics here (pp. 240–253, figures are in millions of pounds).

| Year | Regional Gross Value Added[4] | Agriculture[1] | Industry[2] | Services[3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 2,024 | – | 496 | 1,528 |

| 2000 | 2,750 | – | 658 | 2,092 |

| 2003 | 3,362 | – | 705 | 2,657 |

- Note 1. includes hunting and forestry

- Note 2. includes energy and construction

- Note 3. includes financial intermediation services indirectly measured

- Note 4. Components may not sum to totals due to rounding

A tenth of the city's workforce works at Portsmouth Naval Dockyard, which is directly linked to the city's biggest industry, defence, with the headquarters of BAE Systems Surface Ships located in the city. BAE's Portsmouth Shipyard has been awarded a share of the construction work on the two new Queen Elizabeth class aircraft carriers,[113][114] which will create 3,000 new jobs in the city.[citation needed] There is also a major ferry port which deals with both passengers and cargo. The city is also host to the European headquarters of IBM, and the UK headquarters of Zurich Financial Services and of US defence company Northrop Grumman.

In the last decade the number of stores in Portsmouth have increased due to both the buoyancy of the local economy and improved transport links. In the city centre, shopping is centred on Commercial Road and the 1980s Cascades Shopping Centre, with over 100 high street shops between them. Recent redevelopment has created new shopping areas, including the upmarket Gunwharf Quays, containing fashion stores, restaurants, and a cinema; and the Historic Dockyard, which aims at the tourist sector and holds regular French markets, and an annual Christmas market. Large shopping areas include Ocean Retail Park, on the north-eastern side of Portsea Island, comprising shops requiring large floor space for selling consumer goods; and the Bridge Centre an 11,043 square metre shopping centre built in 1988, now dominated by the Asda store. There are also many smaller shopping areas throughout the city.[115]

The city has a dedicated fishing fleet that consists of 20 to 30 boats that operate out of the camber docks in Camber Quay, Old Portsmouth. They land fresh fish and shellfish daily the majority of which is sold at the quayside fish market to local restaurants.[116]

Culture

Portsmouth has three theatres, two of which were designed by the Victorian/Edwardian architect and entrepreneur Frank Matcham: the New Theatre Royal in Guildhall Walk, near to the City Centre, which specialises in classical, modern and avant-garde drama, and the newly restored Kings Theatre in Southsea's Albert Road, which has many amateur musicals as well an increasing number of national tours.[117] The other theatre is The Groundlings Theatre, situated in The Old Beneficial School, Portsea. The Guildhall, which has a capacity of 2,000 and is Portsmouth's largest events venue, is also used for theatrical performances. Other theatrical venues include the Third Floor Arts Venue in the Central Library and the South Parade Pier.

The city has three established music venues: The Guildhall, The Wedgewood Rooms (which also includes a smaller venue, Edge of the Wedge) and Portsmouth Pyramids Centre. For many years a series of symphony concerts has been presented at the Guildhall by the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra. Outdoor performances by local acts also take place regularly at Southsea Bandstand.

In the past the city was host to a major international string quartet competition, held every three years between 1979 and 1991. In the 1970s the Portsmouth Sinfonia (1970–1979) approached classical music from a different angle.

The City hosts yearly remembrances of the D-Day landings to which veterans from the Allied nations travel to attend.[118] The City played a major part in the 50th D-Day anniversary with then US President Bill Clinton visiting the city.[119]

There are four main nightspots in the city: Southsea (Palmerston Road), Guildhall Walk, Albert Road and Gunwharf Quays. Major nightclubs in th city include Tiger Tiger, Liquid and Envy and Popworld.

Portsmouth Point is an overture for orchestra by the English composer William Walton. The work was inspired by Rowlandson's print depicting Portsmouth Point. It was used as an opening for a Proms Concert in the 2007 season.

H.M.S. Pinafore is a comic opera in two acts, with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert, which is set in Portsmouth Harbour. Using the operetta music of Sullivan (arranged by Charles Mackerras) and The Bumboat Woman's Story by Gilbert, John Cranko's 1951 ballet Pineapple Poll is set at the quayside in Portsmouth. In Patrick O'Brian's Aubrey-Maturin series, Portsmouth is most often the port from which Captain Jack Aubrey's ships sail, and Portsmouth is mentioned at least once in each of the twenty books of the series.

Literature

In literature, Portsmouth is the chief location for Jonathan Meades' novel Pompey, in which it is inhabited largely by vile, corrupt, flawed freaks. He has subsequently admitted that he had never actually visited the city at that time. Since then he has presented a TV programme about the Victorian architecture in Portsmouth Dockyard.[120]

In Jane Austen's novel Mansfield Park, Portsmouth is the hometown of the main character Fanny Price,[121] and is the setting of most of the closing chapters of the book. In Charles Dickens' Nicholas Nickleby, Nicholas and Smike make their way to Portsmouth and get involved in a theatrical troupe.[122]

George Meredith based part of his novel Evan Harrington in what was then the town of Portsmouth, Meredith having grown up in the town.

Victorian novelist and historian, Sir Walter Besant co-wrote with James Rice a novel located the Portsmouth of his 1840s childhood titled By Celia's Arbour: A Tale of Portsmouth Town,[123] and is notable for its precise descriptions of the town before the defensive walls were removed.

Southsea, an area located in Portsmouth, features in The History of Mr Polly by H. G. Wells under the fictional name of Port Burdock, which he describes as one of the three townships that are grouped around the Port Burdock naval dockyards; his experiences working in a Southsea drapery bazaar are related faithfully in his novel Kipps [124]

Neil Gaiman sets his graphic novel The Tragical Comedy or Comical Tragedy of Mr. Punch around Southsea, Gaiman having grown up in Portsmouth.

Graham Hurley's D.I. Faraday/D.C. Winter novels are all located in the city and surrounding area.[125]

C. J. Sansom set his Tudor crime novel Heartstone in the town of Portsmouth, which includes references to the famous warship Mary Rose [126] and descriptions of Tudor life in the town.

A collection of fantastical short stories, Portsmouth Fairy Tales for Grown Ups[127] was published in 2014. It uses locations around Portsmouth for the stories, and includes writing by crime novelists William Sutton [128] and Diana Bretherick [129] (both residents of Portsmouth), children's novelist Zella Compton [130] and author Lynne E Blackwood [131]

Media

Television

Portsmouth is served predominantly with transmissions from the Rowridge Transmitter on the Isle of Wight, although signals from the Midhurst Transmitter can be picked up from the eastern side of the city (around Copnor, Eastney, Baffins, Anchorage Park areas) with the BBC and ITV regions being BBC South & ITV Meridian available from both transmitters.

Portsmouth was one of the first cities in the United Kingdom to have a local TV station, MyTV, in 2001.[citation needed] The station later re-branded Southern 1960 to PortsmouthTV, but its limited availability in some parts of Portsmouth had restricted its growth, and the station later went off-air as a result of the parent company becoming insolvent. In November 2014, new local TV station That's Solent launched as part of a UK wide roll out of local Freeview channels, being broadcast from the Rowridge Transmitter.

The University is heavily involved in the production of television with both faculty-run CCI TV and student-run UPSU TV providing live streamed content aimed at students and the wider community.

Radio

The local commercial radio station is The Breeze (formerly The Quay) on 107.4FM, while the city also has a non-profit community radio station Express FM on 93.7FM. Other radio stations based outside of Portsmouth, but received there are Heart Solent, on 97.5FM, Wave 105 on 105.2FM, BBC Radio Solent on 96.1FM and Sam FM (South Coast) (formerly Jack FM, Original 106 & The Coast) on 106.6FM . Patients at Portsmouth's primary hospital Queen Alexandra and St Mary's hospital in Milton also have access to local programming from charity station Portsmouth Hospital Broadcasting, which is the oldest hospital radio service in the world commencing broadcasts in 1951. [132]

When the first local commercial radio stations were licensed in the 1970s by the IBA, Radio Victory was the radio service for Portsmouth, however in 1986, due to transmission area changes (to formally include Southampton) by the IBA it was replaced by a new company and service called Ocean Sound, later renamed as Ocean FM. It is now known as Heart. From 1994 (the city's 800th birthday) Victory FM broadcast for three 28 day periods over an 18-month period. This service, relaunched on the channel listings guide and 'cable radio' of the South East Hampshire area's cable television network, was renamed Radio Victory. The station went on to win a Radio Authority small scale licence, launching on the 107.4FM frequency, on 19 September 1999. It was purchased from the founders by TLRC, who, due to poor RAJAR figures, relaunched the service in 2001 as The Quay,[133] with Portsmouth Football Club purchasing a stake in the station during 2007 and selling in 2009. The station was taken over by Celador and rebranded The Breeze (East Hampshire & South West Surrey).

Newspapers

The city currently has one daily local newspaper known as The News, which was previously known as the Portsmouth Evening News, together with a free weekly newspaper, from the same publisher, Johnston Press, called The Journal.[134]

Sport

The city is home to professional football team, Portsmouth F.C., who play their home games at Fratton Park. They have two Football League titles (from 1949 and 1950) to their name. They are also previous holders of the FA Cup, having won the 2008 competition. Their other FA Cup triumph came in 1939. They returned to the top flight of English football (Premier League) in 2003, having previously been relegated in 1988 after just one season following an exile from the top flight that had stretched back some 30 years. However, in April 2012 they were relegated from the Championship to League One amid serious financial difficulties. In 2013 Portsmouth were relegated again, this time placing them in the fourth tier of English Football. In April 2013 Portsmouth FC were purchased by the Pompey Supporters Trust (PST) becoming largest fan owned football club in English Football History. Guy Whittingham was appointed as new Portsmouth FC manager starting in the 2013-14 season but was sacked following a run of poor results. Notable current and former players of the club include David James, Hermann Hreiðarsson, Jermain Defoe, Sol Campbell, Peter Crouch, Robert Prosinečki, Alan Knight, Paul Walsh, Darren Anderton, Guy Whittingham, Micky Quinn, Mark Hateley and Jimmy Dickinson, who played more than 800 times for his only club and was never booked or sent off, earning him the sobriquet Gentleman Jim.

Other football teams in the city include Moneyfields FC who play in the Wessex League Premier Division, and are based at Dover Road on the corner with Moneyfields Avenue. United Services Portsmouth F.C. and Baffins Milton Rovers play in the Wessex League Division One,.

Like many port cities on the English south coast, watersports are popular, particularly sailing and yachting. The city is home to Land Rover BAR, an America's Cup team, who are based in Old Portsmouth. Portsmouths rowing club is located in Southsea at the seafront near the Hovercraft Terminal.

The city hosted first-class cricket at the United Services Recreation Ground in Burnaby Road from 1882, while from 1895 to 2000 County Championship matches were played there. This arrangement came to an end in 2000 when Hampshire moved all their home matches to their newly built Rose Bowl home.[135]

The city is currently home to four hockey clubs: City of Portsmouth Hockey Club who are based at the University's Langstone Campus; Portsmouth & Southsea Hockey Club who are based at Admiral Lord Nelson School; Portsmouth Sharks Hockey Club who are also based at Admiral Lord Nelson School; and United Services Portsmouth Hockey Club who are based at Temeraire on Burnaby Road.[136][137][138][139]

Portsmouth is the home city of Britain's first female world champion swimmer Katy Sexton who won gold in the 200m backstroke at the 2003 World Aquatics Championships in Barcelona.

United Services Portsmouth RFC is the city's rugby team. However it is also home to The Royal Navy Rugby Union who play in the annual Army Navy Match at Twickenham. Both teams play their home matches at the United Services Recreation Ground.[140]

Education

The city's post-1992 university, the University of Portsmouth, previously known as Portsmouth Polytechnic, has notable achievements in law, mathematics and biological sciences[citation needed]. Several local colleges also have the power to award HNDs, including Highbury College, the largest[citation needed], which specialises in vocational education; and Portsmouth College, which offers a mixture of academic and vocational courses in the city. Additionally there are several colleges in the surrounding area, all of which offer a varying range of academic and vocational courses[citation needed]. Post-16 education in Portsmouth, unlike many areas, is carried at these colleges rather than at secondary schools.

In 2007 for the first time in over a decade, no school in Portsmouth was below the government's minimum standards and thus none of them was in special measures; nevertheless many still counted among the worst performing schools in the country.[141]

Before being taken over by ARK Schools and becoming Charter Academy, St Luke's Church of England Secondary School was, in terms of GCSE achievement, one of the worst schools in the country. It has improved considerably in recent years[citation needed]. 21% of students achieved five GCSEs at grades A* – C including English and mathematics in 2009[citation needed]. The new academy's aim is that at least 80% will achieve this benchmark by 2014. Charter Academy operates its intake policy as a standard comprehensive taking from its catchment area rather than selecting on religious background. This is the opposite of its nearby rival St Edmund's Catholic School. Both Admiral Lord Nelson School and Miltoncross Academy were built in the 1990s to meet the demand of a growing school age population.[142]

Portsmouth's secondary schools were to undergo a major redevelopment, with three being totally demolished and rebuilt, (St Edmund's, Trafalgar and King Richard's) and the remainder receiving major renovation work.[143] Following the cancellation of the national building programme for schools, these redevelopments did not go ahead.[144]

There is also a cohort of independent schools within the city – the oldest, founded in 1732,[145] is the Portsmouth Grammar School which has been rated as one of the top private schools in the country.[146] There is also the Portsmouth High School, a member of the Girls Day School Trust, ranked one of the top private schools for girls in the UK[citation needed], as well as Mayville High School and St. John's College.

The University of Southampton which trains student nurses and midwives has a campus within the grounds of St Mary's Hospital.[147]

Tourist attractions

Most of Portsmouth's tourist attractions are related to its naval history. Among the attractions are the D-Day Museum (which holds the Overlord embroidery) and, in the dockyard, HMS Victory, the remains of Henry VIII's flagship, the Mary Rose (raised from the seabed in 1982), HMS Warrior (Britain's first iron-hulled warship) and the Royal Naval Museum. The last weekend of November each year the Historic Dockyard host the Victorian Festival of Christmas, which is the largest event of its kind in the UK.

Many of the city's former defences now host museums or events. Several of the Victorian era forts on Portsdown Hill are now tourist attractions. Fort Nelson is now home to the Royal Armouries museum. The Tudor era Southsea Castle has a small museum, and much of the seafront defences up to the Round Tower are open to the public. The southern part of the once large Royal Marines Eastney Barracks is now the Royal Marines Museum. There are also many buildings in the city that occasionally host open days particularly those on the D-Day walk which are seen on signs around the city which note sites of particular importance in the city to Operation Overlord.

Portsmouth's long association with the armed forces means it has a large number of war memorials around the city, including several at the Royal Marines Museum, at the dockyards and in Victoria Park. In the city centre, the Guildhall Square Cenotaph displays the names of the fallen, and is guarded by stone sculptures of machine gunners carved by the sculptor, on the west face: "This memorial was erected by the people of Portsmouth in proud and loving memory of those who in the glorious morning of their days for England's sake lost all but England's praise. May light perpetual shine upon them."

Other tourist attractions include the birthplace of Charles Dickens, the Blue Reef Aquarium (formerly the Sea Life Centre), Cumberland House (a natural history museum), The Royal Marines Museum and Southsea Castle. Southsea's seafront is also home to Clarence Pier Amusement Park and Canoe Lake.

Gunwharf Quays

The former HMS Vernon naval shore establishment was redeveloped in 2001 into the area known as Gunwharf Quays. Gunwharf is a mixed residential and outlet retail destination with 90 outlet stores and 30 restaurants, bars and cafés. Gunwharf Quays plays host to a 14-screen Vue cinema, 26-lane Bowlplex Bowling Alley, Aspex art gallery, Grovenor casino, a Holiday Inn Express and a Tiger Tiger nightclub. The millennium project to build the Spinnaker Tower at Gunwharf Quays was completed in 2005. The tower is 170 m (560 ft) tall and features several viewing platforms giving views across the Solent and Hampshire.

-

The Ordnance Yard administration block (1770s). This building is now trading as a public house called "The Old Customs House"

-

Former Ordnance Storehouse (aka Vulcan building) (1811)

-

Former gatehouse and perimeter wall

Southsea

Southsea is a seaside resort and residential area, at the southern end of Portsea Island. It originally developed as a seaside resort in the Victorian era, and grew into a dense residential suburb and a large distinct commercial and entertainment area, separate from the main city centre.[148] Southsea originates from Southsea Castle; a castle on the seafront built in 1544 to help defend the Solent and approaches to Portsmouth Harbour.[149]

Southsea is dominated by Southsea Common, a large expanse of mown grassland parallel to the shore from Clarence Pier to Southsea Castle. The Common owes its existence to the demands of the military in the early 19th century for a clear range of fire.[150] The Common is a popular recreation ground, and also a venue for a number of annual events, including the Southsea Show, Para Spectacular, Military Vehicle Show, Kite Festival and various circuses including the Moscow State Circus and Chinese State Circus. There is a collection of mature elm trees, believed to be the oldest and largest surviving in Hampshire, which have escaped Dutch elm disease owing to their isolation. Other plants include the semi-mature Canary Island Date Palms Phoenix canariensis, which are some of the largest in the UK and for the last few years have fruited and produced viable seed, the first time this species of palm has been recorded doing so in the UK.[151]

Places of worship

Portsmouth is among only a few British cities with two cathedrals: the Anglican cathedral of St Thomas in Old Portsmouth, and the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St John the Evangelist, in Edinburgh Road, Portsea.[152]

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Portsmouth was founded in 1882 by Pope Leo XIII. Vatican policy in England at the time was to found sees in locations other than those used for Anglican cathedrals; the Ecclesiastical Titles Act forbade a Roman Catholic bishop from bearing the same title as one in the Established Church. Accordingly, Portsmouth was chosen in preference to Winchester.[153]

In 1927 the Church of England diocese of Winchester was divided, and St Thomas's Church became the cathedral for the newly created Diocese of Portsmouth.[154] When St Mary's Church, Portsea, was rebuilt in Victorian times, it had been envisaged that it might be the cathedral if Portsmouth became the seat of a bishop, but St Thomas's was given the honour because of its historic status.

Another historic old Portsmouth church, the Garrison Church, was bombed during the Second World War with the nave kept roofless as a memorial.

Transport and communications

Bus services

Local bus services are provided by First Hampshire & Dorset and Stagecoach, serving the city of Portsmouth and the surroundings of Havant, Leigh Park, Waterlooville, Fareham, Petersfield and long-distance service 700 to Chichester, Worthing and Brighton. Hovertravel and Stagecoach run the Hoverbus from the City Centre to Southsea Hovercraft Terminal and The Hard Interchange. Countryliner run a Saturday service to Midhurst. Xelea Bus operate a Sunday open-top seafront summer service as of 2012[update]; its number is X25. National Express services from Portsmouth run mainly from The Hard Interchange to London, Cornwall, Bradford, Birkenhead and Eastbourne. Many bus services also stop at The Hard Interchange. Other bus services run from the City Centre, from Commercial Road North or Commercial Road South other bus stops are on Station Street, Isambard Brunell Road and Edinbrough road. A new bus station has been proposed next to Portsmouth & Southsea Station, replacing Commercial Road South bus stops and new bus stops and taxi ranks on Andrew Bell Street are to replace the Commercial Road North bus stops when the Northern Quarter Development is built.[155]

Light rapid transit and monorail

There is an ongoing debate on the development of public transport structure, with monorails and light rail both being considered. A light rail link to Gosport has been authorised but is unlikely to go ahead following the refusal of funding by the Department for Transport in November 2005. In April 2011, an article appeared in The News suggesting a new scheme could be in the offering by running a light rapid transit system over the line to Southampton via Fareham, Bursledon, and Sholing replacing the existing heavy rail services. Two of the operators GWR and Southern are in the process of rerouting their Southampton services beyond Fareham to serve Eastleigh and Southampton Airport Parkway leaving just the SWT hourly service on the current route[156] The monorail scheme is unlikely to proceed following the withdrawal of official support for the proposal by Portsmouth City Council, after the development's promoters failed to progress the scheme to agreed timetables.[157]

Railways

The city has several mainline railway stations, on two different direct South West Trains routes to London Waterloo,[158] via Guildford and via Basingstoke. There is also a South West Trains stopping service to Southampton Central (providing connections to CrossCountry services to Birmingham and Manchester), and a service by Great Western Railway to Cardiff Central via Southampton, Salisbury, Bath and Bristol. Southern also offer services to Brighton, Gatwick Airport, Croydon and London Victoria.

Ferries

Portsmouth Harbour has passenger / motorbike ferry links to Gosport and the Isle of Wight from the Portsmouth International Port.[159] A car ferry service to the Isle of Wight operated by Wightlink is nearby.[160] Britain's longest-standing commercial hovercraft service, begun in the 1960s, still runs (for foot passengers) from near Clarence Pier to Ryde, Isle of Wight, operated by Hovertravel.[161]

Portsmouth Continental Ferry Port has links to Caen, Cherbourg-Octeville, St Malo and Le Havre in France,[162][163] Santander and Bilbao in Spain and the Channel Islands. Ferry services from the port are operated by Brittany Ferries, Condor Ferries and LD Lines. On 18 May 2006, Acciona Trasmediterranea started a service to Bilbao in competition with P&O's then existing service. This service got off to a bad start when the ferry Fortuny was detained in Portsmouth by the MCA for numerous safety breaches. The faults were quickly corrected by Acciona and the service took its first passengers from Portsmouth on 25 May 2006. During 2007, AT Ferries withdrew the Bilbao service at short notice, citing the need to deploy the Fortuny elsewhere. P&O Ferries ceased their service to Bilbao on 27 September 2010. The port is the second-busiest ferry port in the UK after Dover, handling around three million passengers a year, and has direct access to the M275.

Airports

The nearest airport is Southampton Airport, situated in the Borough of Eastleigh, which is approximately 20–30 minutes away by motorway, with an indirect South West Trains rail connection requiring a change at Southampton Central or Eastleigh.[164]

Heathrow and Gatwick are both about 60–90 minutes away by motorway. Gatwick is directly linked by Southern services to London Victoria, while Heathrow is linked by coach to Woking, which is on both rail lines to London Waterloo, or by tube to either Victoria or Waterloo. Heathrow is directly linked to Portsmouth by National Express coaches.

Portsmouth Airport, an airport with grass runway, was in operation from 1932 to 1973. After its closure, housing, industrial sites, retail areas and a school were built on the site.

Communications

Portsmouth uses the telephone area code 023[165] in conjunction with eight-digit local numbers. Local numbers usually begin with '9',[166] with numbers beginning '92' being the most common. As Southampton shares the same 023 area code, landline calls between the two cities can be made using just the eight-digit local number, despite their not being adjacent.

Prior to April 2000, Portsmouth used the area code 01705 with six-digit local numbers. The 01705 area code itself replaced the older 0705 code in 1995.

Future developments

Portsmouth will help build and be the home port of the two new Royal Navy aircraft carriers ordered in 2008, HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales. This has secured the base future for the next 40 years.[citation needed] It was announced the government prior to the Scottish Independence Referendum that military shipbuilding would end in the city, with all UK surface warship shipbuilding focusing instead at the two older BAE facilities in Glasgow. This was heavily criticised at the time as a political rather than economic decision to help the No campaign. MP Penny Mordaunt role in the decision as an advisor to the defence secretary was the source of criticism from her political rivals in the city.

Development at Gunwharf Quays continued until 2007 with the completion of the 29-storey 'No. 1 Gunwharf Quays' residential tower (nicknamed 'Lipstick Tower'). The development of the former Brickwoods Brewery site included the construction of a 22-storey tower known as the Admiralty Quarter Tower, the tallest in a complex of mostly low-rise residential buildings.[167] A new 25-storey tower named 'Number One Portsmouth', was made public at the end of October 2008, which has been proposed at a height of 100 m (330 ft), or 82m without the spire, and will stand opposite Portsmouth & Southsea Station on Surrey Street. As of August 2009, internal demolition has started on the building that currently occupies the site.[168][169] A new student accommodation tower, nicknamed 'The Blade' has started construction on the site of the old Victoria swimming baths on Anglesea Road, on the edge of Victoria Park. The 33-storey tower will house 600 University of Portsmouth students, and will stand at 101m, becoming Portsmouth's second tallest structure after the Spinnaker Tower.

Portsmouth F.C. Stadium plans

In April 2007 Portsmouth F.C. announced plans to move away from Fratton Park, their home for 109 years, to a new stadium situated on a piece of reclaimed land on The Hard beside the Historic Dockyard. The £600 million mixed use development, designed by world-renowned architects Herzog & de Meuron, would also include 1,500 harbourside apartments as well as shops and offices. The scheme has attracted considerable criticism due to its huge size and location.[170][171] It also involves moving HMS Warrior from her current permanent mooring. The HMS Warrior trust is refusing to move. In Autumn 2007 Portsmouth's local paper 'The News' published that the plans had been turned down as the supercarriers to be situated in Portsmouth dockyard sight lines would be blocked.

In answer to the Navy's objections regarding the supercarriers, Portsmouth FC have planned a similar stadium in Horsea Island near Port Solent. If this plan ever goes ahead, it will involve building a 36,000 seat stadium and around 1,500 apartments as single standing structures, not around the stadium as had been previously proposed. Yet the new plan also involves improving and saving land for the Royal Navy's diver training centre by the proposed site and buying a fair amount of land from the UK Ministry of Defence.[172] A new £7 million railway station is to be built at Paulsgrove in Racecourse Lane near the site where there was originally a station. Along with these new roads towards the stadium, it has been proposed to build a new bridge from Tipner alongside the motorway[173] for people walking to the stadium. Park and Ride schemes would also be introduced. The development would have a link road to the Port Solent area which would neighbour the new stadium.

If the new proposals are accepted, the club's previous stadium site at Fratton Park would also be redeveloped once the new stadium is completed. Make Architects has been commissioned to draw up designs for 750 new apartments on the site. Due to the overall economic climate and other factors including relegation of the club, plans are currently on hold.

Notable residents

Authors

The city has been home to a number of noted authors.

- Most notably Charles Dickens was born in Portsmouth.[174]

- Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes stories, practised as a doctor in the city and played in goal for Portsmouth Association Football club, an amateur team not to be confused with the later professional Portsmouth Football Club.

- Rudyard Kipling, Michelle Magorian (author of Goodnight Mr Tom) and H. G. Wells (author of War of the Worlds and The Time Machine, lived in Portsmouth during the 1880s.

- Sir Walter Besant, a novelist and historian, was born in Portsmouth[citation needed], writing one novel set exclusively in the town, By Celia's Arbour, A Tale of Portsmouth Town.[175] He was also the author of the posthumously published 10 volume Survey of London [176]

- Sir Francis Austen, brother of Jane Austen, briefly lived in the area.

- George Meredith grew up on Portsmouth High Street.

More modern Portsmouth literary figures include:

- Christopher Hitchens author, journalist and literary critic, who was born in Portsmouth.

- Shirley Conran grew up in the city.

- Nevil Shute moved to Portsmouth in 1934 when he moved his aircraft company Airspeed to the town; his former home stands in the Eastney end of the island of Portsea.[177]

- Neil Gaiman grew up in nearby Purbrook and the Portsmouth suburb of Southsea, and in 2013 had a Southsea road named after his novel The Ocean At The End Of The Lane.[178]

- Olivia Manning's childhood was also spent in the city.

- Another Portsmouth novelist is Graham Hurley, whose Joe Faraday crime novels are based in the city.

- Maggie Sawkins, a long-term resident of Portsmouth, won the 2013 Ted Hughes Award for New Work In Poetry, with her performance piece, Zones of Avoidance.[179]

Others

- Sir Isambard Kingdom Brunel, an engineer of the Industrial Revolution, was born in Portsmouth.[180] His father Marc Brunel worked for the Royal Navy and invented the world's first production line to mass manufacture pulley blocks for the rigging in Royal Navy vessels.

- James Callaghan, British prime minister from 1976–1979, was born and raised in Portsmouth. He was the son of a Protestant Northern Irish petty officer in the Royal Navy. He was also the only person to have held all four Great Offices of State, having previously served as Foreign Secretary, Home Secretary and Chancellor.[181]

- John Pounds, the founder of the Ragged school, which provided free education to working-class children, lived in Portsmouth and a replica of his workshop and first school exists in Old Portsmouth.

- Hertha Ayrton, a scientist and Suffragette, was born in Portsea.

- Sir Barry Cunliffe CBE, one of Britain's leading archaeologists and Emeritus Professor of European Archaeology at Oxford University, grew up in Portsmouth and attended Portsmouth Northern Grammar School (now the Mayfield School).

- The palaeographer Sir Frederic Madden was born in the city in 1801.

- Sir John Armitt CBE, FREng, the Chairman of the London 2012 Olympic Delivery Authority, grew up in Portsmouth and attended Portsmouth Northern Grammar School. He graduated in civil engineering from the Portsmouth College of Technology in 1966.

- Sir Roger Fry CBE, Honorary Doctor of Letters University of Portsmouth and Honorary Fellow of Trinity College Oxford was formerly Chairman and is now[when?] President of the Council of British International Schools (COBIS) and founding Chairman of the King's Group of British International Schools. He was born in Portsmouth and educated at the Northern Grammar School (now Mayfield School) and later at the University of London.

- Due to Portsmouth's naval connections, a long list of admirals, most notably Horatio Nelson and also George Anson and Jonathon Band, former First Sea Lord, have been resident in Portsmouth.

Actors

- Peter Sellers, comedian, actor, and performer was born in Southsea, and Arnold Schwarzenegger lived in Portsmouth for a short time.

Several other professional actors have also been born or lived in the city, including:

- Emma Barton (who appeared as Honey Mitchell in EastEnders)

- Jack Edwards-Eddie Willis, (West End actor) Born and raised in Wymering

- Geeta Basra, Bollywood actress born and raised in Portsmouth.,[182][183]

- Stephen Marcus, actor, born in Portsmouth

- Marcus Patric, actor in Hollyoaks, was born in Portsmouth.

- Nicola Duffett, actress, best known for her role on Family Affairs and Alison Owen, film director, and her son Alfie Owen-Allen, actor, who were both born in Portsmouth.

Ian Darke, football and boxing commentator currently working for BT Sport and previously one of Sky Sports' 'Big Four' football commentators, was born in Portsmouth, as well as music writer for the popular British television show "Doctor Who" Murray Gold. William Swinden Barber, a Victorian Arts and Crafts and Gothic Revival architect, lived out his retirement in Southsea from 1898 to 1908.

- Jonathan Downes, cryptozoologist, is known for living in Portsmouth.

- William Tucker, trader in human heads, Otago settler, New Zealand's first art dealer was born in Portsmouth.

- David Wells, medium and astrologer

- Helen Duncan, last woman imprisoned under the 1735 Witchcraft Act in the UK[184] was arrested in Portsmouth.

Musicians and songwriters

- Simon Heartfield

- Hardcore artist DJ Hixxy

- Roger Hodgson of Supertramp

- Brian Howe, vocalist of Bad Company

- Mick Jones (guitarist), founder of Foreigner, was born in Portsmouth

- Joe Jackson, musician and singer–songwriter born in Gosport

- Paul Jones, vocalist of Manfred Mann

- Dillie Keane, songwriter, entertainer, founder of the popular comedy trio Fascinating Aïda, was born in Southsea

- Roland Orzabal musician (Tears for Fears), Bessie Cursons, 14-year-old musical theatre performer, who appeared on Britain's Got Talent in 2007 came from Portchester

- Ben Falinski, singer in British rock band Ivyrise was born and raised in Portsmouth

- Brothers Phil, Ray and Derek Shulman although not born in Portsmouth, grew up there and this is where they transformed[clarification needed] for Simon Dupree and the Big Sound to the Gentle Giants.

Nevil Shute, also known as Nevil Shute Norway, novelist and aeronautical engineer

Sports

A number of sportsmen and women were born in Portsmouth:

- Michael East, a Commonwealth Games gold medal winning athlete

- Richard Harwood cellist

- Rob Hayles, cyclist and Olympic Games medal winner

- Tony Oakey, former British light-heavyweight boxing champion

- Alan Pascoe, Olympic medallist, was born in Portsmouth

- Sir Alec Rose, single-handed yachtsman

- Katy Sexton, former world champion swimmer

- Roger Black (Olympic medallist) who also attended Portsmouth Grammar School,[185]

- Robert Styles, a FA Premier League referee

- Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain who is currently[when?] playing for Arsenal F.C was born and lived in Portsmouth.

Others

- Sir Arthur Young, policeman and police reformer was born in the area.

Also people notable in the media are known for coming from Portsmouth such as Amanda Holden, television presenter and actress; Kate Edmondson, presenter on MTV and TMF, Matt Edmondson, Radio 1 and Channel 4 presenter, Kim Woodburn of How Clean is Your House? was born in Portsmouth.

Frances Amelia Yates DBE, a British historian, was born in Victoria Road North in Southsea.

See also

- Ferrol—Spanish Armada (1588)

- HMNB Portsmouth

- Old Portsmouth

- Portsmouth and Southsea Synagogue

- Southsea

- List of twin towns and sister cities in the United Kingdom

References

- Citations

- ^ a b "British urban pattern: population data" (PDF). ESPON project 1.4.3 Study on Urban Functions. European Union – European Spatial Planning Observation Network. March 2007. pp. 120–121. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Concentrated Population Information, Portsmouth News". Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Portsmouth Census Summary, Hampshire County Council" (PDF). Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ "Neighbourhood Statistics".

- ^ Togodumnus (Kevan White). "Portus Adurni Roman Britain". Roman-britain.org. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ "Portchester with Roman settlements nearby". Castleuk.net. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ Robert Amy. "Classic Britannica – the home of the Roman Fleet". Pompeymarkets.com. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ "Jean de Gisors; Portsmouth in 1180". Localhistories.org. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ "Norman Conquest run in Portsmouth". Mgcars.org.uk. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ "Early history of Portsmouth". Portsmouth-guide.co.uk. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ "Royal Connections: City of Portsmouth". Royal Central. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ "Portsmouth Continental Ferry Port". World Port Source. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ^ Churchill, Winston Spencer; Sir, Winston Churchill, (1 June 1968). History of the English Speaking People: Birth of Britain, 55 B.C. to 1485. Dodd Mead. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-396-03841-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Portsmouth former Saxon history". Google.co.uk. 21 June 2001. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "History of Portsmouth". Portsmouth Council. Archived from the original on 13 May 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "St Thomas's Portsmouth Cathedral | Old Portsmouth". Welcometoportsmouth.co.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ^ "Portsmouth chapel history". History.inportsmouth.co.uk. 10 January 1941. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ Quail, Sarah (1994). The Origins of Portsmouth and the First Charter. City of Portsmouth. pp. 14–18. ISBN 0-901559-92-X.

- ^ "The liberty of Portsmouth and Portsea Island: Introduction". A History of the County of Hampshire: Volume 3. 1908. Retrieved 25 February 2008.

- ^ a b "''Portsmouth City Council'', (www.civicheraldry.co.uk)". civicheraldry.co.uk. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ "Portsmouth wine trade". Hampshire County Council. 10 June 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Brief history of Portsmouth". Portsmouth Houses. Retrieved 19 July 2016.